Z-Stack Digital Scanning of Parasite Specimens: A Modern Framework for Research and Drug Development

This article explores the application of Z-stack whole-slide imaging (WSI) for digitizing parasite slide specimens, a critical advancement for morphological research and diagnostics.

Z-Stack Digital Scanning of Parasite Specimens: A Modern Framework for Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the application of Z-stack whole-slide imaging (WSI) for digitizing parasite slide specimens, a critical advancement for morphological research and diagnostics. As traditional microscopy skills decline and access to physical specimens becomes limited, Z-stack digital databases offer a powerful solution for preserving, sharing, and analyzing rare parasitological samples. We cover the foundational principles of Z-stacking, detailed methodologies for creating digital parasite databases, strategies for optimizing scan quality and managing large data files, and a comparative analysis of diagnostic accuracy and AI applications. This resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to leverage digital pathology to overcome current challenges in parasitology.

The Urgent Need for Digital Parasitology: Overcoming the Morphology Gap with Z-Stacking

The Challenge of Declining Morphological Expertise and Scarce Specimens

The field of parasitology faces a critical juncture. In an era of advanced molecular diagnostics, traditional morphological expertise—the ability to identify parasites based on their physical characteristics—is in steep decline. Concurrently, the slide specimens essential for training and research have become increasingly scarce in many regions due to improved sanitation and reduced parasite prevalence [1]. This dual challenge threatens both accurate diagnosis of parasitic infections and future research into new therapeutic interventions. However, emerging digital technologies, particularly high-resolution slide scanning with Z-stack imaging and artificial intelligence (AI)-based analysis, offer promising solutions to preserve and enhance our morphological understanding of parasites [1] [2].

The decline in morphological expertise has significant implications for patient care, public health, and epidemiology. Despite advancements in non-morphological diagnostic methods, microscopy-based morphologic analysis remains the gold standard for diagnosing many parasitic infections [1]. This knowledge gap is particularly concerning for drug development professionals who rely on accurate parasite staging and characterization for evaluating potential antimalarial compounds [3].

The Scope of the Problem

Quantifying the Expertise Gap

The reduction in morphological expertise stems from multiple factors. Over the past two decades, educational institutions in developed countries have allocated significantly less time to parasitology education for medical technologists [1]. This trend is reflected globally in the decreasing number of hours devoted to parasitology lectures in medical education programs [1]. A crucial contributing factor is the difficulty in obtaining specimens for educational purposes due to reduced parasitic infections resulting from improved sanitary conditions [1]. Consequently, only limited parasite egg or body part specimens are available in training schools, and these specimens deteriorate over time owing to repeated use [1].

Implications for Drug Development Research

The decline in morphological expertise extends beyond clinical diagnosis to impact drug development research. For Plasmodium falciparum, the deadliest malaria parasite, enumeration of asexual blood stages is fundamental to determining the potency of antimalarial compounds [3]. Differentiation and quantification of these stages sheds light on what parasite processes these compounds target [3]. While light microscopy remains the mainstay for differentiating asexual stages, this process is time-consuming, requires extensive training, and can be variable between microscopists [3]. This variability introduces significant challenges in standardizing drug efficacy assessments across research laboratories.

Digital Solutions: Z-Stack Imaging and AI Analysis

Whole Slide Imaging with Z-Stack Technology

Whole-slide imaging (WSI) technology provides a powerful approach for digitizing glass specimens, creating permanent digital records that do not deteriorate over time [1]. For thicker specimens or those with uneven surfaces, Z-stack imaging is essential for capturing comprehensive morphological data. Z-stack imaging involves collecting images in multiple optical planes by varying the scan depth, accumulating layer-by-layer data to accommodate thicker samples [1].

The technical implementation of Z-stack imaging requires specific protocols:

- Setting Z-Parameters: Using "z-Wide" mode rather than "z-Galvo" mode on compatible systems [4]

- Defining Stack Limits: Finding the region of interest, clicking "Live" to scan, then adjusting gain and offset before turning the focus knob in one direction until the useful signal starts to disappear to set the "Begin" point, then turning the knob in the opposite direction past the sample to set the "End" point [4]

- Optimal Section Thickness: Using "System Optimized" settings that automatically select recommended optical section thickness based on the objective and laser line in use [4]

- Multi-channel Verification: Checking every channel when imaging multiple fluorophores, as Z-stack limits based on one channel might cut out signal from another [4]

After scanning, Z-stacks can be merged using "Maximum Projection" to create a detailed 3-dimensional representation of the sample, or edited using "Crop" functions to isolate specific regions of interest [4].

Database Development and Access

The creation of digital parasite specimen databases represents a significant advancement for both education and research. One preliminary database successfully digitized 50 slide specimens of parasites (eggs and adults) and arthropods from university collections, including specimens typically observed at both low magnification (40x) such as parasite eggs and adults, and high magnification (1000x) such as malarial parasites [1]. These virtual slides were compiled into a digital database with folders organized by taxon, accompanied by explanatory notes in multiple languages to facilitate learning [1].

Such databases offer several advantages:

- Prevention of deterioration: Virtual slides do not deteriorate over time

- Wide accessibility: Shared servers enable approximately 100 individuals to access data simultaneously via web browsers without specialized viewing software [1]

- Remote collaboration: Data can be shared over a wide area via the internet [1]

- Standardized reference materials: Consistent morphological examples available across institutions

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Applications

Artificial intelligence-based digital pathology (AI-DP) is revolutionizing parasite identification and classification. These systems typically use convolutional neural networks to find ova, parasites, and other diagnostically significant objects in digitized slides [5]. The workflow generally involves slide preparation, scanning, AI analysis, and technologist review of the results [5].

For malaria research, high-content imaging paired with machine learning enables automated classification and clustering of cell populations. One approach can robustly differentiate and quantify P. falciparum asexual blood stages and even quantify schizont nuclei—a phenotype that previously had to be enumerated manually [3]. This technology allows researchers to monitor stage progression and quantify parasite phenotypes, enabling discernment of stage specificity of new compounds and providing insight into their mode of action [3].

More advanced implementations use deep learning for continuous single-cell imaging of dynamic processes. One workflow enables continuous, single-cell monitoring of live parasites throughout the 48-hour intraerythrocytic life cycle with high spatial and temporal resolution by integrating label-free, three-dimensional differential interference contrast and fluorescence imaging using an Airyscan microscope, automated cell segmentation through pre-trained deep-learning algorithms, and 3D rendering for visualization and time-resolved analyses [6].

Quantitative Assessment of Digital Methodologies

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Digital Parasitology Technologies

| Technology | Application | Accuracy/Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-content imaging + ML | P. falciparum stage classification | Robust differentiation of asexual blood stages; nuclei enumeration | [3] |

| Cellpose Model (3D) | Infected erythrocyte segmentation | AP₀.₅: 0.54-0.95 (varies by model) | [6] |

| AI-DP for STH | Soil-transmitted helminth detection | Meets WHO TPP minimal requirements for M&E | [2] |

| Fusion Parasitology Suite | Ova and parasite screening | Sensitivity: 98.9%; Specificity: 98.1% (preliminary single-site) | [5] |

Table 2: Comparison of Parasite Preservation Methods for Morphological Studies

| Preservation Method | Advantages | Limitations | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluid preservation (10% formalin → 70% ethanol) | Minimal reduction in parasite detectability; suitable for long-term storage | May alter tissue properties and coloration | Museum collections; historical ecology studies [7] |

| Ethanol (70-80%) | Best general killing/preserving agent; good for molecular studies | Can harden specimens; not ideal for all insect groups | Soft-bodied insects; field collections [8] |

| Ethanol (95-100%) | Prevents wing twisting/hair matting; ideal for DNA preservation | Can distort soft-bodied insects | Molecular studies; parasitic hymenoptera [8] |

| Dry preservation | Standard for many insects; space efficient | Soft-bodied insects may shrivel; mold risk with moisture | Lepidoptera, beetles, hard-bodied insects [8] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Digital Slide Database Creation Using Z-Stack Scanning

Purpose: To create high-resolution digital representations of physical parasite specimens for education and research applications.

Materials and Equipment:

- Slide scanner with Z-stack capability (e.g., SLIDEVIEW VS200, Hamamatsu S360)

- Glass slide specimens

- Shared server infrastructure (Windows Server 2022 or equivalent)

- Image review workstation

Procedure:

- Select slide specimens representing diverse parasite taxa (eggs, adults, arthropods)

- Individually scan each slide using Z-stack function to accommodate varying specimen thickness

- Rescan slides with out-of-focus areas as needed, selecting clearest images

- Upload final images to shared server with folder organization based on taxonomic classification

- Review all digital images for focus and clarity before database incorporation

- Attach explanatory text to each specimen in multiple languages

- Implement access controls requiring user identification and password [1]

Quality Control:

- All digital images must be reviewed for focus and image clarity before incorporation

- Implement regular backup procedures to prevent data loss

- Establish metadata standards for specimen information

Protocol 2: High-Content Imaging and Machine Learning for Antimalarial Drug Assessment

Purpose: To automatically discern and enumerate P. falciparum asexual blood stages and subcellular organelles to determine stage-specific drug effects.

Materials and Reagents:

- Operetta CLS or similar high-content imaging system

- Harmony High-Content Imaging and Analysis software with PhenoLOGIC

- CellMask Orange plasma membrane stain

- Hoechst 33342 (DNA stain)

- MitoTracker Deep Red (mitochondrial membrane potential stain)

- SYTO RNASelect (RNA stain)

- 20× air objective and 40× water objective

Procedure:

- Prepare blood stage P. falciparum cultures with appropriate staining:

- For 20× imaging: Cells can be imaged live or fixed using aldehyde-based fixative

- For 40× imaging: Image live only (fixatives incompatible with MDR and SYTO)

- Use bright field for RBC quantification at 20× magnification

- Use CellMask Orange for RBC quantification at 40× magnification

- Image using appropriate channels for DNA, mitochondria, and RNA

- Apply machine learning classification to:

- Identify and enumerate infected RBCs

- Distinguish and quantify asexual blood stages (rings, trophozoites, schizonts)

- Enumerate nuclei within schizonts [3]

- Quantify stage-specific phenotypes and morphological changes in drug-treated parasites

Quality Control:

- Include control specimens with known parasite stages for algorithm validation

- Validate automated counts against manual enumeration for subset of samples

- Optimize staining protocols to ensure consistent signal-to-noise ratio

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Digital Parasitology Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| CellMask Orange | Plasma membrane staining | RBC quantification at 40× magnification [3] |

| Hoechst 33342 | DNA staining | Identification of parasite nuclei and staging [3] |

| MitoTracker Deep Red | Mitochondrial membrane potential staining | Differentiation of live vs. dead parasites [3] |

| SYTO RNASelect | RNA staining | Visualization of parasite cytoplasm and morphology [3] |

| CellBrite Red | Membrane dye for annotation | Training data creation for segmentation algorithms [6] |

| Cellpose | Convolutional neural network for segmentation | 2D and 3D image analysis of infected erythrocytes [6] |

| Ilastik | Interactive machine learning tool | Volume segmentation based on boundary information [6] |

| Techcyte AI Algorithm | Convolutional neural network for O&P | Finding ova, parasites, and diagnostically significant objects [5] |

Workflow Integration and Implementation Strategies

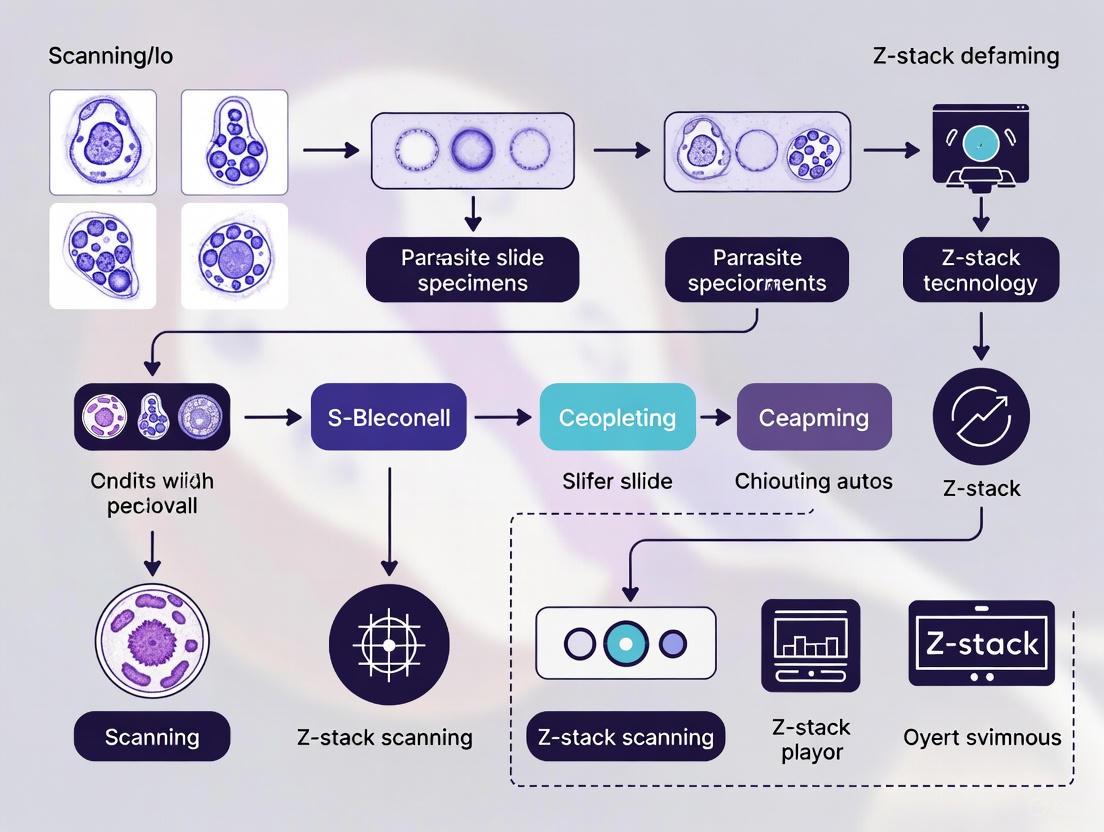

The integration of digital pathology for parasitology requires careful planning of workflows and data management. The following diagram illustrates a comparative workflow between traditional microscopy and AI-enhanced digital pathology:

Diagram 1: Comparative Workflows for Traditional and Digital Parasitology

Successful implementation of digital parasitology platforms requires addressing several practical considerations:

Scanner Selection: Choose whole-slide scanners compatible with planned specimen types (e.g., Hamamatsu S360, Grundium Ocus 40, or Pramana M Pro for 40x scanning) [5]

Data Management: Implement electronic data capture systems to track specimens throughout the digital workflow, using labels with QR codes for sample tracking [2]

Validation Protocols: Establish rigorous validation procedures comparing digital results with manual microscopy, with particular attention to sensitivity and specificity requirements for intended applications [5] [2]

Training Requirements: Develop training programs for both technical staff operating scanning equipment and researchers interpreting AI-generated results

The decline in morphological expertise and scarcity of physical specimens represent significant challenges for parasitology research and drug development. However, digital technologies—particularly Z-stack imaging and AI-based analysis—offer robust solutions to preserve our morphological heritage while enhancing research capabilities. By creating comprehensive digital specimen databases, implementing automated analysis pipelines, and integrating these tools into both education and research workflows, the scientific community can not only preserve existing morphological knowledge but also extract new insights from parasite biology that accelerate drug development efforts.

These digital approaches enable more standardized, quantitative assessments of parasite morphology and drug effects while making specialized expertise more accessible across institutions and geographical boundaries. As these technologies continue to evolve, they hold the potential to transform how we study, diagnose, and develop treatments for parasitic diseases in the 21st century.

What is Z-Stacking? Principles of Multi-Focal Plane Imaging

Z-stacking is an advanced digital imaging technique that involves capturing multiple images of a specimen at different focal planes and combining them into a single composite image with an extended depth of field [9]. This method creates a three-dimensional (3D) representation of the specimen, allowing researchers to view the entire thickness of a sample in sharp focus, which is particularly valuable when analyzing thicker specimens where structures of interest reside at varying depths [9].

In the context of parasitic slide specimen research, Z-stacking overcomes the critical limitation of conventional microscopy where only a small part of a thick sample is in sharp focus at any given time due to the narrow depth of field of high-magnification objectives [9]. For drug development professionals, this technique provides a more accurate representation of parasite morphology, spatial distribution within host tissues, and structural responses to therapeutic interventions, thereby enhancing diagnostic accuracy and research precision.

Core Principles of Z-Stacking Technology

Fundamental Optical Principles

The principle of Z-stacking is founded on addressing the limited depth of field in microscopy. When observing a sample through a microscope, only a thin slice corresponding to the focal plane appears sharp, while areas above and below appear blurred [9]. Z-stacking systematically addresses this by capturing multiple images at different focal points from the top to the bottom of the sample [9]. Each captured image contains a different region in sharp focus, and computational algorithms then combine these images to produce a single composite image where the entire depth of the sample is displayed with clarity [9].

Technical Implementation in Whole Slide Imaging

In whole slide imaging (WSI) systems, Z-stacking is implemented through computer-controlled microscopes equipped with precision mechanical components [9]. Key components include:

- Microscope with objectives: High-precision lenses for image capture

- Brightfield or fluorescent light sources: For specimen illumination

- Robotic positioning systems: For accurate slide movement and repositioning

- Digital cameras: With advanced optical sensors for image acquisition

- Computer systems: For processing power and data management

- Specialized software: For processing, managing, and displaying digital slides

Some advanced WSI scanners employ dynamic refocusing systems that use one camera for focusing and another for scanning, significantly accelerating the scanning process [9]. The scanning speed typically ranges from 1 to 3 minutes per slide, depending on the magnification and the number of Z-stacks required [9].

Z-Stacking Applications in Parasitology Research

Enhanced Morphological Analysis

Z-stacking enables detailed visualization of parasite structures that extend through different focal planes. For drug development researchers, this capability is crucial for accurately assessing morphological changes in parasites following drug exposure. The technique allows for clear imaging of complex 3D structures such as:

- Protozoan invasion mechanisms and host cell penetration

- Helminth surface teguments and attachment organs

- Intracellular parasite forms within host tissues

- Parasite egg morphology and developmental stages

Machine Learning and Automated Classification

Advanced applications of Z-stacking in parasitology research involve machine learning classifiers that utilize the axial information from Z-stacks to identify and segment specific cellular structures [10]. This approach uses the unique intensity profile of each pixel along the z-axis (z-pixels) to classify image regions without relying solely on in-focus morphological features [10].

Research demonstrates that this method successfully identifies different cell morphologies with classification errors of less than 1% when Z-stacks contain at least seven images [10]. For parasitology, this enables automated identification and quantification of parasites within complex host tissues, significantly accelerating research workflows in drug screening applications.

3D Reconstruction and Spatial Analysis

Z-stacking facilitates digital reconstruction of 3D structures, allowing researchers to study the spatial organization of parasites within host tissues [9]. This is particularly valuable for understanding:

- Parasite migration pathways through host organs

- Colonization patterns in tissue layers

- Host-parasite interface at the subcellular level

- Drug distribution and penetration in infected tissues

Experimental Protocols for Parasite Slide Z-Stacking

Z-Stack Acquisition Protocol for Parasite Specimens

Materials Required:

- Parasite slide specimens (thin or thick blood smears, tissue sections)

- Motorized microscope with Z-axis control

- Image acquisition software with Z-stack functionality

- Immersion oil (for oil immersion objectives)

- Calibrated slide with micrometer for system validation

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Slide Preparation and Mounting

- Place parasite specimen slide on motorized stage

- Ensure secure mounting to prevent movement during acquisition

- Apply appropriate immersion medium if using high-NA objectives

System Initialization and Calibration

- Initialize microscope and camera system

- Perform flat-field correction for illumination uniformity

- Calbrate Z-axis step size using reference specimens

Focal Range Determination

- Manually identify top and bottom focal limits of the specimen

- Set Z-range to encompass entire specimen thickness with buffer

- For parasite specimens, typically 5-20μm range depending on specimen type

Acquisition Parameter Optimization

- Set optimal step size based on Nyquist sampling criteria (typically 0.2-0.5μm)

- Configure exposure settings for each channel (brightfield/fluorescence)

- Establish optimal overlap between optical sections

Automated Z-Stack Acquisition

- Initiate automated capture sequence through control software

- Monitor acquisition progress for any errors or stage drift

- Verify image quality at multiple focal planes during acquisition

Image Storage and Backup

- Save raw Z-stack data in appropriate file format

- Create backup copies of original data before processing

- Document acquisition parameters in laboratory notebook

Z-Stack Processing and Analysis Protocol

Image Processing Steps:

Stack Pre-processing

- Apply flat-field correction if not done during acquisition

- Correct for minor stage drift using registration algorithms

- Normalize intensity across slices

Stack Composition

- Select appropriate algorithm for composite image generation

- Choose method based on specimen characteristics:

- Maximum intensity projection: For fluorescence specimens

- Extended depth of focus: For brightfield specimens

- Weighted average: For mixed specimens

Quality Assessment

- Verify focus quality throughout composite image

- Check for artifacts or misalignments

- Compare with original slices for accuracy

Quantitative Analysis

- Perform measurements on composite images

- Conduct 3D analysis using original stack data

- Generate quantitative data for statistical analysis

Machine Learning Classification Protocol for Parasite Identification

Based on established methodology for Z-pixel classification [10]:

Training Set Construction

- Acquire Z-stacks of representative parasite specimens

- Manually label regions of interest using graphical interface

- Define classes: "parasite," "host cell," "background," etc.

Data Preprocessing

- Normalize images using standard histogram equalization

- Extract z-pixel intensity profiles for each labeled region

- Apply Principal Component Analysis to reduce dimensionality

Classifier Training

- Utilize Support Vector Machine or Random Forest algorithms

- Train classifier on reduced-dimension dataset

- Validate classifier performance with test dataset

Prediction and Segmentation

- Apply trained classifier to new Z-stacks

- Generate probability maps for each class

- Refine segmentation using confidence scores

Quantitative Analysis and Data Presentation

Comparison of 2D vs 3D Distance Measurements in Microscopy

Table 1: Comparative analysis of 2D and 3D distance measurement approaches for microscopic analysis of biological structures [11]

| Parameter | 2D Measurements | 3D Measurements |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Moderate, especially for non-flat cells | Higher accuracy for volumetric samples |

| Precision | Good for comparative analyses | Superior for theoretical modeling |

| Susceptibility to Noise | Less prone to noise | More prone to noise and optical aberrations |

| Resolution Limitations | Limited by pixel size in x-y plane | Limited by axial resolution (typically lower than lateral) |

| Sampling Requirements | Single focal plane | Requires optimal z-sampling frequency |

| Computational Requirements | Lower | Higher processing and storage needs |

| Suitability for Parasite Research | Preferred for comparative analyses between cells | Preferred when comparing to theoretical models in large cell samples |

Z-Stack Sampling Optimization Parameters

Table 2: Optimal sampling parameters for Z-stack acquisition based on Nyquist criteria [12]

| Objective Lens | Theoretical Axial Resolution | Recommended Step Size | Minimum Number of Slices for 10μm Specimen |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Air (NA 0.3) | 4.2 μm | 2.0 μm | 5 |

| 20x Air (NA 0.7) | 1.2 μm | 0.6 μm | 17 |

| 40x Oil (NA 1.3) | 0.5 μm | 0.25 μm | 40 |

| 60x Oil (NA 1.4) | 0.4 μm | 0.2 μm | 50 |

| 100x Oil (NA 1.45) | 0.3 μm | 0.15 μm | 67 |

Performance Metrics of Z-Pixel Classification

Table 3: Classification accuracy for different biological structures using Z-stack machine learning approach [10]

| Cell Type | Classification Error | Minimum Z-Slices Required | Optimal Z-Spacing | Processing Time (per 1000x1000 stack) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | <1% | 7 | 100 nm | ~1 minute |

| S. cerevisiae | <1.5% | 10 | 200 nm | ~1.5 minutes |

| Mammalian cells | <2% | 15 | 150 nm | ~2 minutes |

| Mixed culture | <2.5% | 12 | 150 nm | ~2 minutes |

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 4: Essential research reagents and materials for Z-stack imaging of parasite specimens

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Motorized Z-stage | Precision control of focal plane | Enables automated acquisition of multiple focal planes; requires sub-micrometer precision |

| High-NA Objective Lenses | Optimal resolution and light collection | Oil immersion objectives (NA 1.3-1.45) provide best axial resolution |

| Immersion Oil | Medium for high-NA objectives | Matches refractive index of glass; reduces spherical aberration |

| Microfluidic Chambers | Cell culture and immobilization | Maintains parasite viability during time-lapse Z-stack acquisition |

| Fluorescent Labels | Specific structure identification | Allows multiplexing of different parasite structures; requires appropriate filter sets |

| Antifading Reagents | Prevents photobleaching | Essential for fluorescence Z-stacks with multiple slices |

| Refractive Index Matching Solutions | Reduces spherical aberration | Improves image quality throughout Z-stack |

| Calibration Slides | System validation | Verifies XYZ resolution and alignment before specimen imaging |

Workflow Visualization

Z-Stack Acquisition and Analysis Workflow for Parasite Specimens

Principle of Multi-Focal Plane Imaging in Z-Stacking

Application Notes

The digital scanning of parasite slide specimens represents a significant advancement for parasitology education and research. This technology directly addresses two critical challenges: the degradation of rare physical specimens and limited access to specialized morphological knowledge. By creating high-fidelity virtual slides, institutions can preserve fragile biological materials indefinitely and distribute them simultaneously to a global audience of researchers and students [1].

The implementation of a digital database using whole-slide imaging (WSI) technology ensures that rare parasite specimens, which are becoming increasingly difficult to acquire in developed nations due to improved sanitation and declining infection rates, are conserved for future generations [1]. Simultaneously, this digital transformation facilitates widespread access, allowing approximately 100 users to observe specimen data concurrently via web browsers on various devices without specialized viewing software, thus breaking down geographical and institutional barriers [1].

Table 1: Performance and Outcome Metrics from a Digital Parasite Specimen Database Implementation

| Metric Category | Specific Outcome | Quantitative/Qualitative Result | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specimen Volume | Total Slides Digitized | 50 slides [1] | Represents a foundational collection of parasite eggs, adults, and arthropods. |

| Technical Performance | Successful Scanning Rate | 100% of slides [1] | All specimens, from low-magnification eggs to high-magnification malarial parasites, were successfully digitized. |

| Access Capacity | Simultaneous User Access | ~100 users [1] | Enables collaborative learning and large-scale educational sessions without physical specimen constraints. |

| Accessibility | Language Support | Bilingual (English & Japanese) explanatory texts [1] | Enhances utility for both domestic and international users and researchers. |

| Data Integrity | Specimen Preservation | Prevents deterioration from repeated use [1] | Ensures long-term availability of rare and fragile specimens for future study. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for the Construction of a Digital Parasite Specimen Database

This protocol outlines the methodology for digitizing a collection of parasite slide specimens to create an accessible digital database for education and research, based on a published study [1].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Key Materials and Equipment for Slide Digitization

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specification/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Archived Slide Specimens | Source of morphological data for digitization. | 50 slides of parasite eggs, adults, and arthropods; devoid of personal information [1]. |

| SLIDEVIEW VS200 Slide Scanner | High-resolution digital acquisition of slide images. | Manufactured by EVIDENT Corporation; capable of Z-stack scanning [1]. |

| Z-stack Function | Image acquisition at varying focal depths. | Critical for capturing clear images of thicker smears [1]. |

| Shared Server (Windows Server 2022) | Hosting platform for the virtual slide database. | Allows secure, simultaneous multi-user access via web browsers [1]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Specimen Selection and Preparation: Retrieve and compile existing slide specimens. Ensure slides are clean and free of personal identifying information. In the referenced study, specimens were provided by Kyoto University and Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine [1].

- Digital Scanning: Employ a professional slide scanner. Engage the Z-stack function for specimens with thicker smears to accumulate layer-by-layer data and ensure overall image clarity [1].

- Image Quality Control: Review all digitized images for focus and clarity. Rescan any slides with out-of-focus areas as needed to select the clearest image for the final database [1].

- Database Structuring: Upload the final, approved digital images to a shared server. Organize the database folder structure according to the taxonomic classification of the organisms [1].

- Annotation and Access Setup: Attach simple explanatory notes to each specimen in relevant languages (e.g., English and Japanese) to facilitate learning. Implement a secure access system requiring an ID and password for authorized educational and research use [1].

Database Construction Workflow: This diagram outlines the key stages in creating a digital parasite specimen database, from physical slides to a live, accessible resource.

Validation and Technical Considerations

Implementing a digital diagnostics system for cytology specimens involves specific technical considerations. A validation study of an AI-assisted cervical screening system reported that despite using archived slides with inherent quality issues, the total number of cases requiring rescanning was low [13].

Analysis of Technical Errors in Digital Slide Scanning

Table 3: Technical Error Profile During Digital Slide Scanning Validation

| Error Type | Frequency | Common Causes | Resolution Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slide Events | 21 cases (2.3%) [13] | Coverslip scratches from long-term storage, barcode issues, duplicate slides [13]. | Successful rescanning after correction for 8 cases; 13 cases (1.4%) excluded [13]. |

| Imager Errors | 43 events [13] | Motor movement failure, cancelled slide handling actions, failure to pick slides [13]. | System reboot, slide repositioning, vendor technical support [13]. |

The technical errors encountered during scanning, including slide events and imager errors, were resolved through systematic troubleshooting and did not compromise the interpretation of the test slides [13]. This supports the robustness of digitization protocols for valuable specimen collections.

Error Resolution Protocol: This flowchart details the decision-making process for addressing technical errors encountered during the slide digitization process.

Digital pathology is transforming the analysis of parasitic diseases, and Z-stack scanning is at the forefront of this technological revolution. In diagnostic parasitology, challenges such as focal precision and the three-dimensional nature of specimens have historically complicated digital analysis. Z-stack scanning addresses these limitations by capturing multiple images of a specimen at different focal planes along the z-axis, which are then combined to create a single composite image with an extended depth of field [9]. This process creates a three-dimensional representation of the specimen, enabling pathologists and researchers to examine the entire thickness of a sample in sharp focus, much like adjusting the fine focus on a conventional microscope but with digital precision [9] [14].

For parasite research and diagnostics, this capability is particularly valuable. Parasites often present with complex morphological features that may be distributed across different focal planes within a thick smear or tissue section. Traditional single-plane digital imaging can miss these critical diagnostic clues if they lie outside the narrow focal plane. The implementation of Z-stack scanning in whole slide imaging (WSI) systems allows for the creation of multiplanar images that mimic the precise focus control of conventional microscopy, providing an invaluable advantage for cytological and histological analysis of parasitic specimens [9]. This technology is paving the way for more reliable AI-assisted pathology workflows that can ultimately enhance diagnostic accuracy and patient management [15].

Key Applications and Performance Data

Z-stack technology offers diverse applications across parasitology, from educational initiatives to advanced research methodologies. The quantitative benefits of this approach are demonstrated through recent validation studies and research findings, which highlight its growing importance in the field.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Z-Stack Whole Slide Imaging (z-WSI) in Cytopathology

| Metric | Glass Slides | z-WSI | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening-2-Category Accuracy | 91.2% | 87.1% | NILM (normal) vs. lesions (ASC-US+) [16] |

| Morpho-3-Category Accuracy | 86.5% | 81.0% | Classification by lesion severity [16] |

| Inter-observer Agreement (Screening) | 0.685 | 0.637 | Cohen's Kappa [16] |

| Inter-observer Agreement (Morpho) | 0.700 | 0.598 | Cohen's Kappa [16] |

| Average Screening Time | Baseline | +2-5 minutes | Per cytotechnologist [16] |

| AI Mitosis Detection Sensitivity | Baseline | +17.14% | In meningioma cases [15] |

The data indicates that while z-WSI currently shows slightly reduced agreement metrics compared to traditional glass slides, the technology demonstrates significant advantages in specific applications such as AI-assisted detection, where it substantially improves sensitivity [15]. With targeted training specifically designed for WSI interpretation, diagnostic accuracy and workflow efficiency are expected to improve significantly [16].

Table 2: Core Applications of Z-Stack Scanning in Parasitology

| Application Domain | Specific Use Cases | Key Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Accuracy | Identification of parasite morphological features, staging of parasitic infections, differentiation of similar species | Enhanced depth information brings entire parasite structures into focus, reducing diagnostic uncertainty [15] [9] |

| Education & Training | Creation of focus-adjustable digital slides for teaching, development of comprehensive parasite image databases | Allows students to explore focal depths without physical microscopes; enables remote education [14] |

| High-Throughput Research | Drug efficacy studies, parasite behavior analysis, morphological changes under experimental conditions | Facilitates batch scanning and analysis; compatible with AI-based quantification [15] [17] |

| 3D Reconstruction | Visualization of parasite internal structures, host-parasite interface modeling, parasite movement studies | Enables digital reconstruction of 3D structures from serial z-plane images [9] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Z-Stack Imaging of Parasite Specimens

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for acquiring Z-stack images of parasite specimens using motorized microscopy systems, adapted from established imaging procedures [14] and optimized for parasitology research.

Materials Required:

- Motorized microscope with Z-stack capability (e.g., Zeiss Axio Imager.M2 or equivalent)

- 100x oil immersion objective (1.4 NA recommended)

- Immersion oil

- Prepared parasite slides (e.g., blood smears, tissue sections, fecal concentrates)

- Z-stack compatible software (e.g., ZEN Blue, FIJI/ImageJ)

Procedure:

- System Initialization: Turn on the microscope and allow sufficient time for system initialization and communication with the control software. Launch the acquisition software (e.g., ZEN Blue) and select the appropriate professional version for advanced functionality.

Slide Preparation and Screening: Place the parasite slide onto the motorized stage. Begin screening under lower magnification (20x or 40x) to identify regions of interest containing parasite forms. Center the target area in the field of view.

Oil Immersion Application: For high-resolution imaging at 100x magnification, apply immersion oil directly to the slide area covering the region of interest. Switch to the 100x oil immersion objective, ensuring proper contact with the immersion oil.

Z-Stack Parameter Configuration:

- Access the "Acquisition" tab and select "Live" mode.

- Expand the "Z-Stack" configuration settings.

- Set the first focal plane by focusing above the parasite structure and clicking "Set First."

- Set the last focal plane by focusing below the parasite structure and clicking "Set Last."

- Adjust the slice interval to optimize for parasite features (typically 0.2-0.5µm for high-resolution imaging).

Image Acquisition: Click "Start Experiment" to initiate the Z-stack capture. Maintain environmental stability during capture by avoiding vibrations or disturbances to the microscope.

Post-processing and Export:

- Apply necessary scale bars using graphics tools.

- Adjust contrast and color levels using histogram functions in the "Display" tab.

- Export images as TIFF files with compression set to "None" to preserve image quality for subsequent analysis.

Protocol for Validation of Z-WSI in Parasitology Diagnostics

This protocol outlines a validation methodology for implementing Z-stack whole slide imaging in parasitology diagnostics, based on clinical validation studies [16] and adapted for parasite detection.

Materials Required:

- Whole slide scanner with Z-stack capability

- Reference set of parasite slides (e.g., malaria, leishmaniasis, trypanosomiasis)

- Traditional microscope setup for comparison

- Statistical analysis software

Procedure:

- Sample Collection and Preparation: Collect a representative set of parasite-positive samples (minimum n=90-100 recommended), encompassing various parasite loads and developmental stages. Include negative controls and challenging diagnostic cases.

Slide Digitization: Scan all slides using the Z-stack WSI system, optimizing the number of Z-planes based on specimen thickness. For thin blood smears, 5-10 planes may suffice, while thicker tissue sections may require 15-20 planes.

Reader Study Design: Engage multiple trained parasitologists (minimum n=4) to evaluate cases using both conventional microscopy and z-WSI separately, with a washout period between evaluations to prevent recall bias.

Data Collection and Analysis:

- Collect diagnostic classifications for both modalities using standardized reporting schemas.

- Record reading time for each case to evaluate workflow efficiency.

- Calculate inter- and intra-observer agreement using statistical measures (e.g., Cohen's Kappa).

- Compare diagnostic accuracy against reference standards.

Implementation Planning: Based on validation results, develop specialized training programs for z-WSI interpretation in parasitology, focusing on challenging diagnostic scenarios and optimal digital navigation techniques.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagrams illustrate key processes and applications of Z-stack technology in parasitology, created using Graphviz DOT language with specified color palette and contrast requirements.

Diagram 1: Z-Stack Workflow for Parasitology

Diagram 2: Traditional vs. Z-Stack Microscopy

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Successful implementation of Z-stack imaging in parasitology requires specific instrumentation, software, and reagents. The following table details the essential components of a Z-stack imaging workflow for parasite research.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Z-Stack Parasitology Research

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Imaging Hardware | Motorized microscope with Z-axis control | Enables precise capture of multiple focal planes; essential for Z-stack acquisition [14] |

| Image Analysis Software | FIJI/ImageJ, CellProfiler, ZEN lite | Processes Z-stack images; performs quantification, 3D reconstruction, and analysis [17] [18] |

| Sample Preparation | Specific stains for parasites (Giemsa, Trichrome, etc.) | Enhances contrast of parasite structures; facilitates identification across focal planes |

| Slide Scanning | Whole slide scanner with Z-stack capability | Digitizes entire slides at multiple focal planes; enables high-throughput analysis [9] |

| Data Management | .CZI file format compatible software | Maintains metadata integrity; enables cross-platform image data exchange [18] |

| AI-Assisted Analysis | Machine learning-based segmentation tools | Automates parasite identification and quantification in Z-stack images [15] [18] |

Z-stack scanning represents a transformative technology in parasitology, with demonstrated applications spanning diagnostic precision, educational enhancement, and high-throughput research. While current validation studies show slightly reduced performance metrics compared to traditional microscopy in some categorical classifications, the significant improvements in detection sensitivity—particularly when combined with AI analysis—highlight its potential to revolutionize parasite detection and characterization [15] [16]. The structured protocols and tools outlined in this application note provide a foundation for implementing Z-stack methodologies in parasitology workflows. As digital pathology continues to evolve, Z-stack scanning is poised to become an indispensable technology for advancing parasite research and improving diagnostic outcomes in clinical settings. With appropriate training and workflow optimization, this technology promises to enhance both the efficiency and accuracy of parasite detection, ultimately contributing to better patient management and expanded research capabilities.

Building a Digital Parasite Database: A Step-by-Step Z-Stack Protocol

The creation of a high-fidelity digital parasite specimen database hinges on the meticulous selection and preparation of physical samples. In the context of digital scanning for research, the quality of the original specimen directly determines the quality and scientific utility of the resulting digital asset. This document details the protocols for selecting and preparing parasite eggs, adults, and arthropods for whole-slide imaging (WSI), with a specific focus on methodologies that facilitate high-quality Z-stack imaging for three-dimensional analysis. These standardized procedures are designed to support the development of a reproducible digital repository for parasitology education and advanced research [1].

Specimen Selection Criteria

A foundational step in database construction is the careful curation of physical specimens. The selection must ensure morphological clarity, taxonomic diversity, and relevance to both diagnostic and research applications.

Table 1: Core Specimen Types for a Digital Parasitology Database

| Specimen Category | Key Specimen Examples | Primary Observation Magnification | Critical Morphological Features for Digitization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parasite Eggs | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, hookworm species [1] | Low (e.g., 40x) [1] | Egg size, shape, wall thickness, opercular presence, embryonic content |

| Adult Parasites | Nematodes, trematodes, cestodes (whole mounts or sections) [1] | Low to Medium (e.g., 40x-100x) [1] | Overall body plan, digestive and reproductive structures, cuticular details, sensory organs |

| Arthropods | Ticks, fleas, mosquitoes (whole mounts or sections) [1] | Low (e.g., 40x) [1] | Body segmentation, mouthparts, leg morphology, wing venation, setae patterns |

| Intracellular Blood Parasites | Plasmodium spp. (malaria parasites) [1] [19] | High (e.g., 1000x) [1] | Parasite stage (ring, trophozoite, schizont, gametocyte) [19], host cell modifications |

The selection strategy should prioritize specimens that are well-preserved and morphologically intact. Specimens acquired from institutional collections, such as those from Kyoto University and Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine used in a foundational study, provide a reliable starting point [1]. For arthropods, alternative high-throughput digitization methods using charge-coupled device (CCD) flatbed scanners have been validated, showing that scanned images can achieve a quality comparable to stereomicroscopy for machine learning applications [20].

Experimental Protocols for Specimen Preparation and Imaging

Protocol 1: Whole-Slide Imaging (WSI) with Z-Stack for Thick Specimens

This protocol is adapted from the methodology used to construct a preliminary digital parasite specimen database, which successfully digitized 50 slide specimens of parasites and arthropods [1].

1. Specimen Preparation and Mounting:

- Source: Obtain existing glass slide specimens from institutional collections or prepare new slides using standard parasitological histological techniques [1].

- Curation: Ensure slides are free of significant damage and the specimen is centrally located and properly stained for contrast.

- Note: Specimens do not require special preparation for Z-stack imaging at this stage; the technology accommodates existing slides.

2. Digital Scanning Configuration:

- Equipment: Use a high-precision slide scanner, such as the SLIDEVIEW VS200 by EVIDENT Corporation or equivalent [1].

- Z-Stack Function: For thicker specimens (e.g., adult parasites, arthropods), activate the Z-stack function. This technique varies the focal plane during the scan, accumulating layer-by-layer data to create a fully focused composite image and a 3D data set [1].

- Quality Control: Manually review scanned images for focus and clarity. Rescan any slides with out-of-focus areas as needed [1].

3. Data Management and Storage:

- Upload: Transfer the final, approved virtual slide files to a dedicated shared server (e.g., Windows Server 2022) [1].

- Organization: Structure the digital database with folders organized by taxonomic classification [1].

- Annotation: Attach explanatory notes in multiple languages (e.g., English and Japanese) to each specimen to facilitate learning and international collaboration [1].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key steps from physical specimen to analyzable digital data:

Protocol 2: Continuous Single-Cell Live Imaging ofPlasmodium falciparum

For the study of dynamic processes in live parasites, such as the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum, a more advanced workflow integrating live imaging and deep learning is required [6].

1. Sample Preparation and Immobilization:

- Culture: Maintain P. falciparum-infected human erythrocytes under standard in vitro culture conditions.

- Mounting: Prepare samples for continuous imaging on appropriate glass-bottom dishes or chambers.

2. Multi-Dimensional Image Acquisition:

- Microscopy: Use a high-resolution system like an Airyscan microscope, capable of both differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescence imaging [6].

- Acquisition Parameters: Acquire 3D z-stacks over time (4D imaging) throughout the parasite's 48-hour intraerythrocytic life cycle. Use minimal laser power to mitigate the parasite's high photosensitivity [6].

3. Deep Learning-Enabled Image Analysis:

- Segmentation: Employ a pre-trained convolutional neural network (CNN) like Cellpose for automated segmentation of erythrocytes and intracellular parasites [6].

- Training: Re-train the network on a manually annotated dataset of uninfected erythrocytes and infected cells at different stages (ring, trophozoite, schizont) to optimize performance [6].

- Analysis: Use the segmented images for 3D rendering and time-resolved quantitative analysis of dynamic processes, such as protein export [6].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Parasite Imaging

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| OPTIClear | A refractive index homogenization solution optimized for clearing fresh and archival human brain tissues, enabling 3D visualization of microstructure [21]. | Contains N-methylglucamine, 2,2'-thiodiethanol, and Iohexol; R.I. ~1.47 [21]. |

| Cellpose | A deep learning-based convolutional neural network (CNN) for automated 2D and 3D segmentation of cells and subcellular structures [6]. | Pre-trained model that can be re-trained with a few annotated examples for specific tasks like segmenting infected erythrocytes [6]. |

| CellBrite Dyes | Membrane-binding fluorescent dyes used to delineate cell boundaries for improved annotation and segmentation in complex samples [6]. | Used to stain the erythrocyte membrane for creating accurate training datasets for neural networks [6]. |

| Composite Loss Function | A custom training objective for machine learning models that combines multiple loss types to improve performance. | Hybrid CapNet uses a blend of margin, focal, reconstruction, and regression losses for robust parasite classification [19]. |

| Poly-D-Lysine (PDL) | A substrate coated on glass to promote neuronal adhesion and growth in patterned cultures for controlled experiments [22]. | Demonstrates the principle of using substrates to guide cellular organization for imaging [22]. |

Discussion and Technical Considerations

The transition from physical specimen to digital asset involves several critical technical considerations. For thick specimens, the Z-stack function is indispensable for capturing comprehensive morphological data, as it ensures all focal planes are recorded [1]. Furthermore, the inherent challenge of photobleaching during live, long-term imaging must be addressed. Recent research indicates that for quantitative analyses like mitochondrial volume measurement in C. elegans, global threshold-based image segmentation may not require prior correction for photobleaching, simplifying the analytical pipeline [23].

The integration of deep learning, as demonstrated by both the Cellpose model for segmentation [6] and the Hybrid CapNet for parasite classification [19], is revolutionizing the analysis of parasitological images. These tools not only automate tedious tasks but also extract quantitative data that are difficult to obtain manually, thereby enhancing the research value of digital specimens.

Robust protocols for the selection and preparation of parasite eggs, adults, and arthropods form the foundation of any high-quality digital specimen database. By leveraging modern imaging technologies like Z-stack scanning and combining them with advanced analytical methods such as deep learning, researchers can create enduring, accessible, and analytically powerful digital resources. These databases are crucial for preserving morphological knowledge, facilitating international collaboration in parasitology education, and accelerating future research and drug development efforts.

The digitization of parasitology slides via whole slide imaging (WSI) is transformative for education and research, particularly given the increasing scarcity of physical specimens in developed nations [1]. However, a significant technical challenge in this process is the limited depth of field of microscope objectives, which makes it difficult to image thicker specimens in sharp focus across their entire depth [9]. Z-stacking, a technique that captures multiple images at different focal planes and composites them into a single, fully focused image, directly addresses this issue [9]. This application note provides detailed protocols and data-driven recommendations for configuring Z-stack parameters—specifically, the number of layers, depth interval, and magnification—to optimize the digital capture of parasite specimens for subsequent AI analysis and morphological research.

Quantitative Comparison of Scanning Protocols

A 2025 study on automated HER2 analysis in breast cancer provides a directly applicable, quantitative framework for evaluating scanning parameters. The findings, summarized in the table below, underscore the critical impact of resolution and Z-stack configuration on the success of automated analysis [24].

Table 1: Performance of Different Scanning Protocols in Automated Image Analysis

| Scanner | Protocol ID | Resolution (µm/pixel) | Z-Stack / Focus Notes | Concordance with Manual Ground Truth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | A1 | 0.12 | 0.95 NA (Dry lens) | Yes [24] |

| A | A2 | 0.12 | 1.2 NA (Water immersion lens) | Yes [24] |

| B | B1 | 0.08 | Single plane | Not Reported [24] |

| B | B2 | 0.17 | Single plane | Yes [24] |

| B | B3 | 0.17 | Extended Focus (1.4 µm step size, 3 layers) | Yes [24] |

| C | C1 | 0.26 | Single plane | No (Nuclei detection failure in 6/10 cases) [24] |

The study concluded that protocols with optimized resolutions (0.12 µm/pixel and 0.17 µm/pixel with extended focus) yielded the best performance for the AI application [24]. The failure of the lower-resolution protocol (C1) highlights that insufficient resolution can render images unusable for automated analysis, regardless of focus.

Experimental Protocols for Z-Stack Image Acquisition and Analysis

Protocol 1: Z-Stack Acquisition for Diverse Parasite Specimens

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used in creating a digital parasite database and in automated diagnostic systems [1] [25].

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare standard Giemsa-stained thick and thin blood smears or other parasite-specific stained slides [25].

- Ensure slides are clean and free of debris.

Scanner Pre-configuration:

Define Z-Stack Parameters:

- Determine Total Z-Depth: Use the scanner's software to identify the top and bottom surfaces of the specimen. The total Z-depth is the distance between these two points.

- Set Step Size: A step size of 1.4 µm has been successfully used in clinical-grade automated analysis [24]. For thicker or more complex specimens, a smaller step size (e.g., 0.5-1.0 µm) may be necessary to capture finer focal details.

- Calculate Number of Layers: The number of layers (Z-stack images) is determined by the formula: Number of Layers = (Total Z-Depth / Step Size) + 1.

Image Acquisition:

Protocol 2: AI-Assisted Parasite Detection in Thick Blood Smears

This protocol details the process for training and implementing a convolutional neural network (CNN) for automated parasite detection, based on the iMAGING system [25].

Image Dataset Creation:

CNN Model Training and Comparison:

- Split the annotated dataset into training, validation, and test sets (e.g., 80/10/10).

- Train multiple state-of-the-art object detection models (e.g., YOLOv5x, Faster R-CNN, SSD, RetinaNet) on the same dataset to compare performance [25].

- Evaluate models based on precision, recall, F-score, and mean Average Precision (mAP). The iMAGING system achieved an overall F-score of 92.79% and mAP of 94.40% [25].

System Integration and Automated Diagnosis:

- Integrate the best-performing predictive model into a smartphone-computer application [25].

- Couple the application with a robotized microscope system capable of automated slide tracking and auto-focusing [25].

- The integrated system can then perform a fully automated diagnosis, determining if a sample is positive/negative and quantifying parasite levels [25].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the critical decision points and workflow for optimizing scanner configuration for parasite specimen digitization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Parasitology Slide Digitization

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Giemsa Stain | Standard staining for malaria parasites and other blood-borne pathogens; allows for visualization of nuclear and cytoplasmic details [25]. |

| VENTANA HER2 Dual ISH DNA Probe Cocktail | Example of a commercially available in-situ hybridization probe kit; analogous probes could be developed for specific parasite DNA targets [24]. |

| Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) Blocks | Standard method for long-term preservation of tissue specimens; allows for sectioning of thin slices for slide preparation [24]. |

| Microfluidic MPS Chips | Advanced platforms for creating 3D biological models (e.g., microvessels) to study host-parasite interactions in a controlled environment [26]. |

| Collagen Gel | A common 3D matrix used in microphysiological systems (MPS) to support the culture of complex tissue structures for imaging [27]. |

| NIS-Elements Imaging Software | Software equipped with Z Intensity Correction functionality to correct for light attenuation in thick samples during 3D confocal imaging [27]. |

The digital transformation of parasitology leverages whole-slide imaging (WSI) to preserve valuable specimens, enhance research capabilities, and facilitate global collaboration. This document details a standardized workflow for digitizing parasite slide specimens—including eggs, adults, and arthropods—and managing the resulting data on a shared server. This process is particularly critical for parasitology, where the decline in morphological expertise and the scarcity of specimens in developed regions pose significant challenges to education and diagnostics [1]. The implementation of a structured digital workflow ensures the long-term preservation of rare specimens and provides simultaneous, remote access for researchers and drug development professionals, thereby accelerating biomarker validation and clinical studies [28] [29].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Specimen Preparation and Slide Digitization

Objective: To convert glass slides of parasite specimens into high-quality, digitized whole-slide images (WSIs) suitable for quantitative analysis and archiving.

Materials:

- Glass slide specimens of parasites (e.g., eggs, adult worms, arthropods).

- SLIDEVIEW VS200 slide scanner (Evident Corporation) or equivalent [1].

- Computer workstation with scanner control software.

Methodology:

- Slide Preparation Verification: Visually inspect all glass slides to ensure the specimen is intact, coverslipped correctly, and free of significant debris or damage.

- Scanner Configuration:

- Power on the scanner and initialize the control software.

- Select the appropriate scanning mode based on the specimen type. For thicker specimens (e.g., adult parasites), enable the Z-stack function to capture multiple focal planes, accumulating layer-by-layer data to ensure a completely in-focus image [1].

- Set the scan resolution. For parasite eggs and adults typically observed at low magnification (40x), a lower resolution may suffice. For specimens requiring high magnification, such as malarial parasites (1000x), select the highest possible resolution [1].

- Slide Loading and Scanning:

- Load slides into the scanner's tray. For high-throughput labs, systems like the ZEISS Axioscan 7 can accommodate up to 100 slides per run for walk-away automation [29].

- Initiate the scanning process. For efficiency, high-capacity scanners can be used for overnight bulk scanning, while smaller scanners handle urgent daytime cases [28].

- Quality Control (QC):

- After scanning, review each WSI for focus, clarity, and color fidelity.

- Slides with out-of-focus areas must be rescanned. Select the clearest image for subsequent upload [1].

- Implement additional QC measures to ensure high-quality standards from block cutting to cover slipping, which may initially extend processing times [28].

Protocol 2: AI-Based Parasite Egg Detection and Model Validation

Objective: To train and evaluate a deep learning model for the automated detection of soil-transmitted helminth (STH) and Schistosoma mansoni eggs in digitized stool smear images, assessing performance in real-world conditions.

Materials:

- Dataset: AI4NTD KK2.0 P1.5 STH & SCHm Dataset V2 (or similar annotated dataset of STH and S. mansoni eggs) [30].

- Computing environment with GPU acceleration.

- YOLOv7 (You Only Look Once version 7) framework installed.

Methodology:

- Data Preparation and Augmentation:

- Refine the dataset by rectifying intrinsic annotation errors to create a high-quality training set [30].

- Employ a 2x3 montage data augmentation strategy to enhance the model's generalization to out-of-distribution (OOD) scenarios. This technique creates composite images from multiple source images, making the model more robust to variations in image capture devices and unseen egg types [30].

- Model Training:

- Train multiple variants of the YOLOv7 model (e.g., YOLOv7-E6E) on the refined and augmented dataset.

- Monitor standard object detection metrics, such as F1-score and mean Average Precision (mAP), during training.

- Model Evaluation:

- In-Distribution (ID) Testing: Evaluate the model on a test set that matches the training data. YOLOv7-E6E has been shown to achieve an F1-score of 97.47% in ID settings [30].

- Out-of-Distribution (OOD) Testing: Rigorously test the model under two challenging conditions to simulate real-world use:

- OOD Condition 1: A dataset shift caused by a change in the image capture device.

- OOD Condition 2: A combination of a device change and the introduction of two egg types not seen during training.

- Use the Toolkit for Identifying object Detection Errors (TIDE) to perform a comprehensive error analysis, highlighting specific causes for drops in Average Precision (e.g., localization vs. classification errors) [30].

- Apply Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) to visualize the model's decision-making process and investigate instances of false positives and false negatives [30].

Protocol 3: Data Upload, Management, and Secure Access on a Shared Server

Objective: To transfer validated WSIs and associated analytical data to a centralized, secure shared server for collaboration, storage, and analysis.

Materials:

- Server: Windows Server 2022 or equivalent shared server infrastructure [1].

- Validated WSIs and analysis results.

- Client computers with web browser access.

Methodology:

- Database Structure Creation:

- On the shared server, create a folder structure organized by the taxonomic classification of the parasites (e.g., Nematoda, Platyhelminthes, Arthropods) [1].

- Data Upload and Annotation:

- Upload the finalized WSIs to their corresponding taxonomic folders on the server.

- Attach explanatory notes to each specimen in both English and Japanese (or other relevant languages) to facilitate international learning and use. Include the specimen name and a brief description of its morphological characteristics [1].

- Access Control and Security:

- Implement a secure login system. Users must input a unique identification code and password provided by the host organization to access the virtual slide database [1].

- For clinical trials or regulated research, employ a platform like HALO AP, which features bulk, automatic de-identification of Protected Health Information (PHI) to ensure compliance with HIPAA and GDPR [31].

- Collaboration and Analysis:

- The shared server should be configured to allow approximately 100 individuals to access and observe the data simultaneously via a web browser on various devices without specialized viewing software [1].

- For advanced analysis, integrate with AI-powered image analysis platforms located in high-performance cloud environments (e.g., Amazon Web Services) to access scalable processing power on demand [32].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete integrated workflow, from physical slide to collaborative analysis, incorporating key decision points and parallel processes.

Diagram Title: Comprehensive Digital Parasitology Workflow

Performance data for AI models and operational metrics for shared server access are critical for evaluating the effectiveness of the digital workflow.

Table 1: Performance Evaluation of YOLOv7 Models for Parasite Egg Detection

| Model Variant | Evaluation Scenario | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | mAP@IoU0.5 (%) | F1-Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv7-E6E | In-Distribution (ID) | Data Not Shown | Data Not Shown | Data Not Shown | 97.47 [30] |

| YOLOv7 (Various) | OOD (Device Change) | +8.0* [30] | +14.85* [30] | +21.36* [30] | Data Not Shown |

| YOLOv7 (Various) | OOD (Device Change + Unseen Eggs) | Challenged | Challenged | Challenged | Data Not Shown |

Note: mAP = mean Average Precision; IoU = Intersection over Union; OOD = Out-of-Distribution. *Indicates average performance gain with 2x3 montage augmentation.*

Table 2: Shared Server Capabilities and Access Metrics

| Parameter | Specification / Metric | Context / Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Simultaneous Users | ~100 individuals [1] | Facilitates large-scale collaborative research and education. |

| Access Requirement | ID Code & Password [1] | Ensures data security and controlled access for confidentiality. |

| Client Software | Web browser (no specialized software) [1] | Reduces barriers to access and simplifies user experience. |

| Device Compatibility | Laptops, tablets, smartphones [1] | Enables flexible, remote work and learning. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

A successful digital parasitology workflow relies on integrated hardware, software, and reagent solutions.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item / Solution | Function / Application in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| SLIDEVIEW VS200 Slide Scanner [1] | The core hardware used for generating high-quality whole-slide images (WSIs), featuring Z-stack functionality for thick specimens. |

| InSituPlex, SignalStar, OPAL Dyes [29] | Leading multiplex immunofluorescence (mIF) and tyramide signal amplification (TSA) reagent chemistries for biomarker panel development on tissue samples. |

| ZEISS Axioscan 7 [29] | An automated slide scanner supporting both mIF and brightfield (IHC/H&E) imaging in a single run, enabling high-throughput, walk-away automation. |

| HALO AP / HALO AP Dx Platform [32] [31] | An AI-powered software platform for quantitative digital pathology analysis, including a Clinical Trials module for blind scoring and data management compliant with FDA 21 CFR Part 11 and GDPR. |

| YOLOv7 Framework [30] | A state-of-the-art deep learning model framework used for real-time object detection, such as identifying and classifying parasite eggs in stool smear images. |

| Windows Server 2022 [1] | The operating system for the shared server infrastructure that hosts the digital slide database, enabling secure storage and controlled access. |

Application Note

This application note details the methodology and implementation of a preliminary digital parasite specimen database, constructed to address the critical challenge of maintaining parasitology education and research capabilities in an era of declining physical specimen availability. The project leveraged whole-slide imaging (WSI) technology to create a bilingual, virtual slide database from 50 physical parasite specimens, facilitating international practical training and research within medical education programs [1].

The decline in morphological expertise, essential for diagnosing parasitic infections, is a growing concern in developed nations where improved sanitation has minimized parasitic infection rates and consequently, access to educational specimens [1]. This database serves as a vital resource to counteract this trend, preserving high-fidelity digital representations of parasite morphology that are accessible to a global audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. The platform supports simultaneous access for approximately 100 users, promoting collaborative international research and education without the risks of specimen deterioration or damage associated with traditional microscopy training [1] [33].

Experimental Protocols

Specimen Sourcing and Curation

Fifty existing slide specimens of parasitic eggs, adult parasites, and arthropods were procured from the collections of Kyoto University and Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine [1]. The specimens represented a taxonomically diverse range, including specimens typically observed at both low magnification (40X), such as parasite eggs and ticks, and high magnification (1000X), such as malarial parasites [1]. These slides were carefully selected for their educational and research value, and none contained personal information, ensuring their ethical use for shared academic purposes [1].

Digital Slide Scanning and Image Processing

Digital scanning of all 50 slide specimens was performed by the Biopathology Institute Co., Ltd. using an SLIDEVIEW VS200 slide scanner (EVIDENT Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) [1]. The scanning protocol was tailored to accommodate the varying physical characteristics of the specimens:

- Z-stack scanning: For specimens with thicker smears, the Z-stack function was employed. This technique varies the scan depth to accumulate layer-by-layer data, ensuring all focal planes are captured for three-dimensional specimens [1].

- Quality control: Each slide was scanned individually. Initial scans with out-of-focus areas were rescanned as needed. The clearest image from each scanning session was selected by the authors after a thorough review for focus and image clarity before incorporation into the final database [1].

Database Architecture and Deployment

The digitized virtual slide data was compiled into a structured database hosted on a shared server (Windows Server 2022) [1]. The database architecture was designed for optimal usability and security:

- Taxonomic organization: A folder structure was created, organizing specimen data according to established taxonomic classification [1].

- Bilingual annotations: Each specimen was accompanied by explanatory notes in both English and Japanese to facilitate learning and use by domestic and international users [1].

- Controlled access: To ensure confidentiality, access to the database requires users to input an identification code and password provided by the host organization, restricting use to agreed-upon educational and research purposes [1].

Data Presentation

The following table summarizes the core quantitative outputs and specifications of the database construction project.

Table 1: Project Outputs and Technical Specifications

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Total Slide Specimens Digitized | 50 [1] |

| Specimen Types | Parasite eggs, adult worms, arthropods [1] |

| Magnification Range | 40x (low) to 1000x (high) [1] |

| Scanning Technology | Whole-Slide Imaging (WSI) [1] |

| Key Technical Feature | Z-stack function for thick smears [1] |

| Scanner Model | SLIDEVIEW VS200 (EVIDENT Corp.) [1] |

| Simultaneous User Capacity | ~100 users [1] |

| Language Support | Bilingual (English, Japanese) [1] |

Database Accessibility and Usage Metrics

Table 2: User Accessibility and Interface Features

| Feature | Implementation |

|---|---|

| Access Method | Web browser on laptops, tablets, or smartphones [1] |

| Software Requirement | No specialized viewing software required [1] |

| Data Preservation | Prevents physical specimen deterioration and damage [1] |

| Server Environment | Shared server (Windows Server 2022) [1] |

| Folder Organization | By taxonomic classification [1] |

| Learning Support | Explanatory notes for each specimen [1] |

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for constructing the bilingual digital parasite database, from specimen preparation to end-user access.

System Architecture Diagram

This diagram outlines the technical architecture of the deployed digital database system, showing the relationship between its core components.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| SLIDEVIEW VS200 Slide Scanner | High-resolution digital slide scanner used for creating whole-slide images (WSI) of parasite specimens, enabling high-magnification digital microscopy [1]. |

| Z-stack Function Software | Specialized scanning software capability that varies scan depth to accumulate layer-by-layer data, crucial for capturing focused images of three-dimensional or thick smear specimens [1]. |

| Existing Physical Slide Specimens | Curated collection of 50 parasite eggs, adult worms, and arthropods used as the source material for digitization, providing the morphological basis for education and diagnosis [1]. |

| Bilingual Annotation Framework | System for attaching explanatory notes in both English and Japanese to each digital specimen, facilitating international collaboration and learning [1]. |

| Shared Server Infrastructure | On-premises server environment (Windows Server 2022) hosting the virtual slide database, enabling secure, simultaneous multi-user access while maintaining data sovereignty [1]. |

| Taxonomic Classification System | Organizational structure for categorizing and storing digital specimens within the database, mirroring biological taxonomy to enhance searchability and educational utility [1]. |

Optimizing Z-Stack Scans: Balancing Data Quality, File Size, and Efficiency

Determining the Optimal Number of Z-Layers for Different Specimens