The Unseen Burden: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Control of Intestinal Protozoan Infections

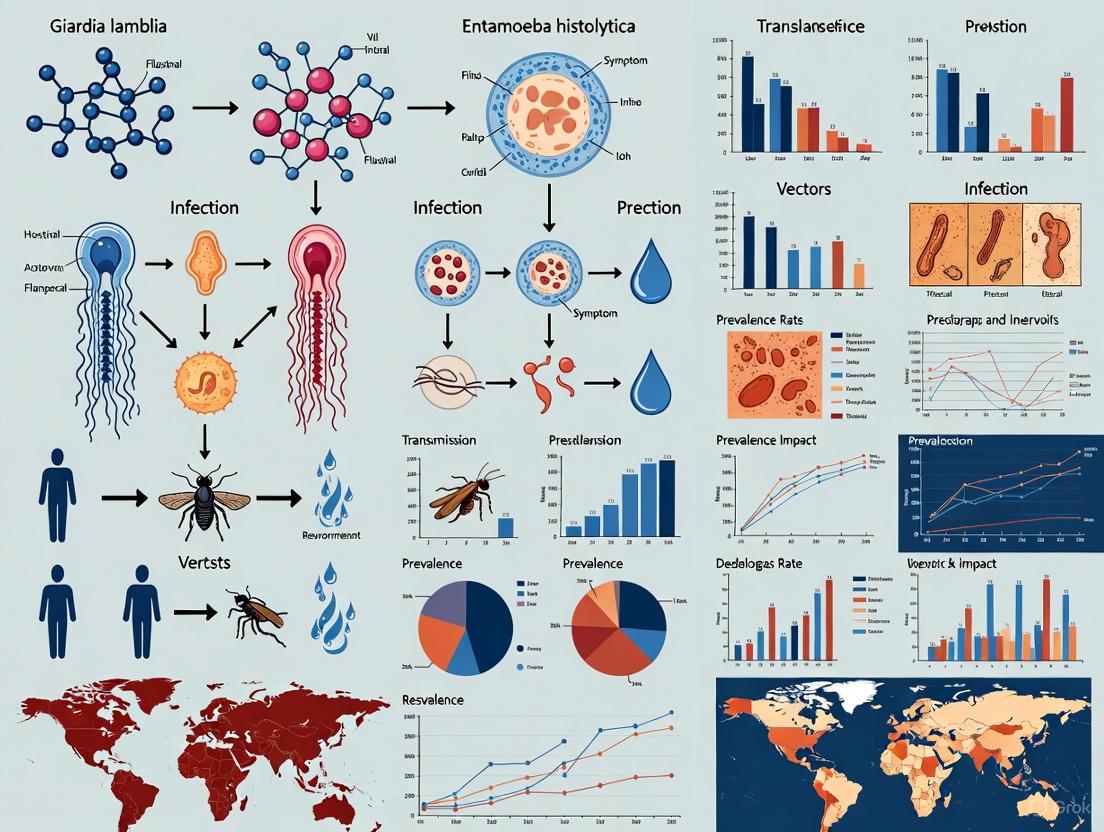

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the epidemiology of intestinal protozoan infections, focusing on the major pathogens Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia lamblia, and Cryptosporidium spp.

The Unseen Burden: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Control of Intestinal Protozoan Infections

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the epidemiology of intestinal protozoan infections, focusing on the major pathogens Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia lamblia, and Cryptosporidium spp. It synthesizes current data on global and regional prevalence, identifies key socioeconomic and environmental risk factors, and evaluates the strengths and limitations of conventional and advanced diagnostic methodologies. Furthermore, it examines the challenges in the current therapeutic landscape, including drug resistance, and explores future directions for drug discovery and public health intervention. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review aims to bridge epidemiological insights with practical applications for improved disease control and drug development strategies.

Global Burden and Risk Factors: Mapping the Impact of Intestinal Protozoa

Intestinal protozoan infections (IPIs) represent a significant and persistent global health challenge, particularly in resource-limited settings. These infections, primarily caused by Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia lamblia, and Cryptosporidium parvum, contribute substantially to the global burden of diarrheal diseases, which remain a leading cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide [1] [2]. The World Health Organization identifies diarrhea as the third leading cause of death among children under five years, with approximately 443,832 annual fatalities [1]. Understanding the current epidemiological landscape of IPIs is fundamental for developing targeted interventions, guiding drug development initiatives, and shaping public health policy. This systematic review synthesizes recent data on the global prevalence and incidence of intestinal protozoan infections, framing the findings within the broader context of epidemiological research and therapeutic development.

The clinical manifestations of IPIs range from asymptomatic carriage to severe diarrheal illness with potential for long-term sequelae. Amebiasis, caused by E. histolytica, is characterized by symptoms including abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea, fever, and in severe cases, liver abscesses [3]. Giardiasis typically presents with watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, flatulence, and weight loss, while cryptosporidiosis manifests with watery diarrhea accompanied by stomach cramps, nausea, and vomiting, with particular severity in immunocompromised individuals [4] [3]. The transmission of these pathogens occurs predominantly through the fecal-oral route, with contamination of food and water serving as major vehicles for dissemination [5]. Despite their significant public health impact, IPIs have historically been neglected in drug discovery efforts, with few therapeutic advances in recent decades and growing concerns about drug resistance [1] [2].

Global Epidemiology of Intestinal Protozoan Infections

Intestinal protozoan infections impose a substantial disease burden worldwide, disproportionately affecting populations in tropical and subtropical regions with inadequate sanitation infrastructure. Current estimates indicate that approximately 3.5 billion people are affected by IPIs globally, with around 450 million people currently suffering from active infections [6] [3]. These infections are responsible for nearly 1.7 billion episodes of diarrhea annually, contributing significantly to global morbidity and mortality statistics [5]. The disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) attributed to these infections are considerable, with amebiasis alone responsible for more than 55,000 deaths and 2.2 million DALYs, while cryptosporidiosis accounts for approximately 100,000 deaths and 8.4 million DALYs [2].

The geographical distribution of IPIs reflects complex interactions between environmental factors, socioeconomic conditions, and public health infrastructure. Developing countries in tropical regions bear the greatest disease burden, with prevalence rates often exceeding 25% in certain populations [6]. The parasites exhibit a global distribution, but the highest concentrations are found in areas of Central and South America, Africa, and Asia, with prevalence rates reaching up to 25% in some heavily indebted poor countries [3]. This unequal distribution highlights the role of socioeconomic determinants in disease transmission and the critical need for targeted interventions in high-burden regions.

Regional Variations in Prevalence

Significant geographical heterogeneity exists in the prevalence of intestinal protozoan infections, with notable variations between and within world regions. A recent meta-analysis focusing on Malaysia reported an overall pooled prevalence of 24% (95% CI: 0.17-0.29) for IPIs in the country [4]. Subgroup analysis revealed considerable regional variation within Malaysia, with Kelantan and Perak states reporting the highest prevalence rates of 39% and 29% respectively, while Selangor and Kuala Lumpur reported substantially lower rates of 13.6% [4]. These variations likely reflect differences in infrastructure, sanitation practices, and socioeconomic factors across regions.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, prevalence rates are notably elevated. A recent health facility-based cross-sectional study conducted in Simada, northwest Ethiopia, documented a strikingly high prevalence of 57.1% among individuals visiting a health center [7]. Occupational factors significantly influenced risk, with farmers (AOR = 8.0), secondary school students (AOR = 3.1), and merchants (AOR = 4.7) demonstrating higher likelihood of infection [7]. Similarly, a study among school children in Zeita village, Central Ethiopia, found an overall IPI prevalence of 46.8%, with E. histolytica (25.2%), G. lamblia (19.3%), and C. parvum (2.5%) identified as the predominant pathogens [8]. These figures substantially exceed global averages and underscore the disproportionate burden borne by particular regions and populations.

Table 1: Regional Prevalence of Intestinal Protozoan Infections

| Region/Country | Prevalence (%) | Predominant Pathogens | Population Studied | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Estimate | ~24% (pooled) | Entamoeba spp., Giardia lamblia, Cryptosporidium spp. | General population | [4] |

| Ethiopia (Simada) | 57.1% | Not specified | Health center visitors | [7] |

| Ethiopia (Zeita) | 46.8% | E. histolytica (25.2%), G. lamblia (19.3%) | School children | [8] |

| Malaysia | 24% | Entamoeba spp. (18%), G. lamblia (11%) | General population | [4] |

| Kelantan, Malaysia | 39% | Entamoeba spp. | General population | [4] |

| Selangor/Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia | 13.6% | Entamoeba spp. | General population | [4] |

Prevalence in Specific Populations

The risk of intestinal protozoan infections is not uniformly distributed within populations, with certain demographic groups experiencing disproportionately high infection rates. Indigenous communities consistently demonstrate elevated prevalence rates, with a meta-analysis in Malaysia reporting a 27% prevalence among indigenous populations compared to 23% in local communities from rural areas [4]. This disparity likely reflects differences in access to healthcare, sanitation infrastructure, and educational resources.

School-aged children represent another vulnerable population, with studies consistently reporting high infection rates in this demographic. Research among school children in Central Ethiopia revealed that factors including parental occupation (P = 0.028), sources of drinking water (P = 0.001), water handling practices (P = 0.027), consumption of raw vegetables (P = 0.001), and latrine availability significantly influenced infection risk [8]. Interestingly, this study found no significant association between gender and IPI prevalence (P = 0.54), suggesting environmental and behavioral factors outweigh biological sex as determinants of infection [8].

Immunocompromised individuals, particularly those with HIV/AIDS, also face elevated risk and disease severity. Studies in Malaysia have documented increased rates of cryptosporidiosis among intravenous drug users with HIV-positive status, highlighting the intersection of parasitic infections with other health challenges [4]. Prison inmates with HIV-positive status showed slightly higher IPI prevalence (27.5%) compared to HIV-negative inmates (25.8%) [4], emphasizing the need for targeted screening and prevention in institutional settings.

Pathogen-Specific Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Distribution of Major Pathogenic Species

The relative prevalence of specific protozoan pathogens varies geographically and among different population groups. According to a comprehensive meta-analysis of studies in Malaysia, Entamoeba species demonstrate the highest prevalence at 18% (95% CI: 0.12-0.24), followed by G. lamblia at 11% (95% CI: 0.08-0.14), and Cryptosporidium species at 9% (95% CI: 0.03-0.14) [4]. This distribution pattern reflects the biological characteristics and transmission dynamics of each pathogen, with Entamoeba species potentially benefiting from greater environmental persistence and multiple transmission routes.

The prevalence of specific pathogens also shows considerable variation across studies and settings. In research conducted among Ethiopian school children, E. histolytica was identified as the most prevalent pathogen (25.2%), followed by G. lamblia (19.3%) and C. parvum (2.5%) [8]. The relatively low detection of Cryptosporidium in this study may reflect methodological limitations, as specialized staining techniques are required for optimal identification of this pathogen [8]. These findings underscore the importance of diagnostic approach in determining pathogen-specific prevalence rates and the value of multiplex detection methods in surveillance studies.

Table 2: Prevalence of Specific Intestinal Protozoan Pathogens

| Pathogen | Global Prevalence Estimates | Clinical Manifestations | High-Risk Populations | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entamoeba histolytica | 18% (Malaysia meta-analysis); 25.2% (Ethiopian children) | Amebic dysentery, liver abscess | School children, indigenous communities | [4] [8] |

| Giardia lamblia | 11% (Malaysia meta-analysis); 19.3% (Ethiopian children) | Watery diarrhea, malabsorption, weight loss | Children, travelers, immunocompromised | [4] [8] |

| Cryptosporidium parvum | 9% (Malaysia meta-analysis); 2.5% (Ethiopian children) | Profuse watery diarrhea, particularly severe in immunocompromised | HIV+ individuals, children | [4] [8] |

| Intestinal protozoa collectively | 450 million current infections globally | Diarrhea, abdominal pain, malnutrition | Children in developing countries | [6] [3] |

Environmental Contamination and Transmission Dynamics

Environmental reservoirs play a crucial role in the transmission and persistence of intestinal protozoan infections. A global systematic review and meta-analysis of vegetable and fruit contamination found a pooled prevalence of intestinal protozoan parasites of 20% (16-24%) in vegetables and 13% (8-20%) in fruits [5]. Contamination occurs primarily through irrigation with contaminated water, fertilization with untreated manure, and improper handling during harvesting and transportation. The analysis included 189 articles with 202 datasets, examining 45,495 vegetable samples and 5,113 fruit samples, providing comprehensive insights into this transmission route [5].

The risk of foodborne transmission is influenced by agricultural practices, hygiene standards, and environmental conditions. The meta-analysis revealed that low-income countries reported significantly higher prevalence of protozoan contamination in vegetables and fruits compared to high-income countries [5]. This disparity reflects differences in regulatory frameworks, sanitation infrastructure, and agricultural practices between economic contexts. Geographical factors also influenced contamination rates, with the African region reporting the highest prevalence (25%), followed by the Eastern Mediterranean region (24%) [5]. These findings highlight the importance of food safety interventions within broader IPI control strategies.

Socioeconomic and Behavioral Determinants

Risk factor analyses consistently identify socioeconomic status and hygiene behaviors as critical determinants of IPI transmission. A meta-analysis of ten risk factors in Malaysia found significantly elevated pooled prevalence (38-52%) among children under 15 years, males, individuals with low income or no formal education, and those exposed to untreated water, poor sanitation, or unhygienic practices [4]. These findings align with studies from Ethiopia identifying low income (AOR = 3.3) and failure to wash hands before meals (AOR = 12.4) as significant predictors of infection [7].

The association between poverty and IPI risk reflects multiple pathways, including inadequate sanitation infrastructure, limited access to clean water, crowded living conditions, and educational barriers. In the Ethiopian study, participants with no habit of handwashing before meals had more than 12 times higher odds of IPIs compared to those with consistent handwashing practices [7]. Similarly, improper water handling practices and consumption of raw vegetables significantly increased infection risk among school children [8]. These findings underscore the potential of integrated interventions addressing water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) alongside educational components to reduce IPI transmission.

Research Methodologies and Diagnostic Approaches

Epidemiological Study Designs

Robust epidemiological investigation of intestinal protozoan infections requires careful consideration of study design and methodology. Cross-sectional studies represent the most common approach for estimating prevalence, providing snapshot assessments of infection rates at specific timepoints. The studies cited in this review employed health facility-based [7] and community-based [8] cross-sectional designs, each offering distinct advantages for different research questions. Health facility-based designs facilitate sample collection and diagnostic procedures but may introduce selection bias, while community-based designs enhance representativeness at the cost of operational complexity.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have emerged as powerful tools for synthesizing evidence across multiple studies and generating pooled prevalence estimates. The Malaysia meta-analysis followed PRISMA guidelines, conducted comprehensive searches across five databases (Scopus, Google Scholar, Web of Science, PubMed, and Cochrane Library), and employed a random effects model to account for heterogeneity [4]. This approach identified 103 potentially relevant articles, with 49 studies meeting inclusion criteria after duplicate removal and eligibility screening [4]. The high statistical heterogeneity observed (I² = 98.94%, P < 0.001) reflects substantial variability across included studies, necessitating careful interpretation of pooled estimates [4].

Laboratory Diagnostic Techniques

Accurate diagnosis of intestinal protozoan infections requires appropriate laboratory methods with sufficient sensitivity and specificity. Basic microscopic techniques, including direct wet mount examination and formol-ether concentration methods, remain widely used in resource-limited settings [7] [8]. While cost-effective and technically accessible, these approaches have limitations in sensitivity and ability to differentiate between pathogenic and non-pathogenic species.

Advanced diagnostic methods improve detection capabilities but require greater technical and financial resources. The Modified Ziehl-Neelsen (MZN) staining technique enables identification of Cryptosporidium oocysts, which are often missed in routine microscopy [8]. Immunoassays detecting parasite-specific antigens offer enhanced sensitivity and specificity, while molecular approaches such as real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) provide the highest sensitivity and enable species differentiation [3]. The optimal diagnostic approach depends on available resources, technical expertise, and specific clinical or research objectives, with many settings benefiting from a combination of methods.

Diagram 1: Diagnostic Workflow for Intestinal Protozoan Infections. This flowchart illustrates the sequential approach to laboratory diagnosis of IPIs, from sample collection to final identification, highlighting both basic and advanced methodological pathways.

Quality Assessment and Statistical Analysis

Methodological rigor in IPI research requires careful attention to quality assessment and appropriate statistical approaches. The Malaysia meta-analysis utilized Cochrane's Q and I² statistics to quantify heterogeneity, with I² values >75% indicating high heterogeneity [4]. Random-effects models were employed to account for this variability, and publication bias was assessed using funnel plots and Egger's test [4]. Similar approaches were applied in a global meta-analysis of IPIs in colorectal cancer patients, which included 70 studies and assessed quality using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale [9].

Sample size considerations are particularly important in IPI research, as inadequate power may limit the ability to detect significant associations. The Ethiopian school-based study initially calculated a sample size of 422 using a single population proportion formula but ultimately collected data from 280 respondents due to school absenteeism during the COVID-19 pandemic [8]. Such methodological adaptations highlight the practical challenges of conducting field research in resource-limited settings while underscoring the importance of transparent reporting of limitations.

Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Intestinal Protozoan Infection Studies

| Reagent/Material | Application | Specific Function | Examples/References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formol-ether | Stool concentration | Preserves parasites and removes debris | Used in concentration techniques [7] [8] |

| Modified Ziehl-Neelsen stain | Cryptosporidium detection | Acid-fast staining of oocysts | Identification of C. parvum [8] |

| Specific antigens | Immunoassays | Detection of parasite-specific proteins | EIA for E. histolytica, Giardia [3] |

| PCR primers/probes | Molecular detection | Amplification of parasite DNA | Real-time PCR assays [3] |

| Culture media | Parasite isolation | Support growth of trophozoites | Axenic culture for E. histolytica [1] |

| Microscopy reagents | Stool examination | Visualization of parasites | Iodine, saline for wet mounts [8] |

Implications for Public Health and Drug Development

Public Health Interventions

The high prevalence rates documented across multiple regions underscore the urgent need for enhanced public health interventions targeting intestinal protozoan infections. The significant association between WASH indicators and infection risk supports continued investment in water sanitation infrastructure and hygiene education programs [7] [8]. The identification of specific high-risk populations, including school children, indigenous communities, and agricultural workers, enables targeting of limited resources to maximize impact [7] [4].

Food safety interventions represent another critical component of comprehensive IPI control. The substantial contamination rates documented in vegetables and fruits (20% and 13% respectively) highlight the importance of measures to prevent contamination throughout the production and distribution chain [5]. These include treatment of irrigation water, proper composting of manure, and education for food handlers regarding hygienic practices. Regulatory frameworks governing food safety should incorporate specific standards for parasitic contamination, particularly in high-prevalence regions.

Drug Development and Therapeutic Considerations

The current therapeutic landscape for intestinal protozoan infections remains inadequate, with few advances in recent decades and growing concerns about drug resistance. Metronidazole, the most common drug used for treating invasive amebiasis and giardiasis, has been in use for over 60 years, with efficacy limitations and significant side effects including nausea, vomiting, and potential resistance [1] [2]. Treatment failures in giardiasis occur in up to 20% of cases, rising to 40.2% in some settings [2]. Similarly, nitazoxanide, the only treatment option for cryptosporidiosis, demonstrates variable efficacy (56-80%) and is not effective for immunocompromised patients [2].

Promising drug development approaches include target-based screening, drug repurposing, and natural product discovery. Auranofin, an anti-rheumatic compound, has shown efficacy against Giardia and Entamoeba in clinical trials, inhibiting parasite thioredoxin reductase [1] [2]. Azidothymidine (AZT), an antiretroviral drug, also exhibits inhibitory activity against Giardia [1]. High-throughput screening approaches have identified novel compound classes with anti-protozoal activity, including chalcone derivatives with efficacy against Giardia [2]. These developments represent potential advances in the therapeutic arsenal against IPIs, though translation to clinical practice remains challenging.

Diagram 2: Drug Development Pipeline for IPIs. This workflow outlines the major pathways for discovering and developing new therapeutic agents against intestinal protozoan parasites, from initial approach selection through clinical development.

Intestinal protozoan infections remain a significant global health challenge, with recent systematic reviews documenting pooled prevalence rates of approximately 24% in endemic regions and rates exceeding 50% in some high-risk populations [7] [4]. The substantial geographical and demographic heterogeneity in infection rates reflects complex interactions between pathogen biology, environmental factors, and socioeconomic determinants. The high prevalence of protozoan contamination in vegetables and fruits (20%) underscores the importance of food safety interventions within comprehensive control strategies [5].

From a research perspective, methodological standardization would enhance comparability across studies, particularly regarding diagnostic approaches and risk factor assessment. The high statistical heterogeneity observed in meta-analyses (I² > 98%) highlights the substantial variability in current evidence and the need for more standardized methodologies [4]. Future research should prioritize high-quality epidemiological studies in underrepresented regions, development of improved diagnostic tools suitable for resource-limited settings, and investigation of the long-term health consequences of chronic protozoan infections.

Therapeutic development for IPIs has lagged behind other infectious diseases, with heavy reliance on decades-old drugs and emerging resistance patterns [1] [2]. Recent advances in parasite genomics, chemical biology, and drug repurposing offer promising avenues for therapeutic innovation. Translating these discoveries to clinical practice will require enhanced collaboration between academic researchers, pharmaceutical companies, and public health agencies, with particular attention to ensuring accessibility and affordability in high-burden populations. Through integrated approaches addressing both environmental transmission and therapeutic limitations, substantial progress can be made toward reducing the global burden of intestinal protozoan infections.

Intestinal protozoan infections (IPIs) represent a significant global health challenge, with a distribution pattern that highlights profound disparities between tropical and developed regions. This whitepaper provides a comparative analysis of the endemicity of IPIs, drawing on recent meta-analytical data and longitudinal cohort studies. It examines the prevalence rates, key risk factors, and species distribution of major protozoans—including Entamoeba spp., Giardia lamblia, and Cryptosporidium spp.—across different geographical and socioeconomic contexts. The paper details standardized methodologies for epidemiological surveillance and laboratory diagnosis, supported by data visualization and a catalog of essential research reagents. The analysis confirms that poverty, inadequate sanitation, and limited access to healthcare are the primary drivers of the high IPI burden in tropical regions, underscoring the need for targeted interventions and robust research capabilities.

The global distribution of intestinal protozoan infections (IPIs) serves as a stark indicator of the health inequities between tropical and developed regions. These infections, caused by pathogens such as Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia lamblia, and Cryptosporidium spp., are predominantly faecal-oral in transmission, making them intensely sensitive to environmental and socioeconomic conditions [10]. In tropical and subtropical regions, IPIs are a pervasive public health challenge, disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations, including school-aged children, indigenous communities, and low-income households [11] [4]. In contrast, developed regions typically report IPIs as sporadic cases, often associated with travel, localized outbreaks, or immunocompromised individuals [12]. The persistence of high IPI prevalence in tropical areas is intrinsically linked to factors such as poverty, inadequate water and sanitation infrastructure, and climatic conditions favorable to pathogen transmission [10] [7]. This document synthesizes current evidence to delineate the hotspots of IPI endemicity, compare the underlying risk factors, and equip researchers with the methodological frameworks for continued investigation into these neglected tropical diseases.

Comparative Analysis of Endemicity Patterns

Quantitative data from recent systematic reviews and cohort studies reveal distinct patterns of IPI endemicity. The following tables summarize key prevalence rates and risk factor associations, providing a clear comparison between different regional contexts.

Table 1: Global and Regional Prevalence of Intestinal Protozoan Infections

| Region/Country | Overall IPI Prevalence | Prevalence of Entamoeba spp. | Prevalence of G. lamblia | Prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. | Population Studied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malaysia (National Average) | 24% (95% CI: 17.0–29.0) [4] | 18% (95% CI: 12–24) [4] | 11% (95% CI: 8–14) [4] | 9% (95% CI: 3–14) [4] | General Patient Population |

| Malaysia (Indigenous Communities) | 27% [4] | - | - | - | Indigenous Groups |

| Malaysia (Rural Communities) | 23% [4] | - | - | - | Rural Dwellers |

| Eswatini (Manzini & Lubombo) | 42.2% (2022) [11] | Predominant [11] | - | - | Schoolchildren (2022 Cohort) |

| Ethiopia (Simada District) | 57.1% [7] | - | - | - | Health Center Visitors |

| Developed Regions (United States) | - | - | - | - | Sporadic/Imported Cases [12] |

Table 2: Key Risk Factors and Associated Measures of Effect for IPIs

| Risk Factor | Population/Setting | Measure of Effect (Adjusted Odds Ratio, aOR) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Employed Parent | Schoolchildren, Eswatini [11] | aOR = 3.97 (95% CI: 1.48–10.64) | p=0.006 |

| No Handwashing Before Meals | Simada, Ethiopia [7] | aOR = 12.4 (95% CI: 5.6–27.6) | Significant |

| Low Income | Simada, Ethiopia [7] | aOR = 3.3 (95% CI: 1.6–7.0) | Significant |

| Occupational Group (e.g., Farmer) | Simada, Ethiopia [7] | aOR = 8.0 (95% CI: 8.2–28.5) | Significant |

| Untreated Water, Poor Sanitation | Malaysia (Meta-Analysis) [4] | Pooled Prevalence: 38-52% | Significant |

The data demonstrates that IPI prevalence in tropical regions is substantially higher than the sporadic cases typically encountered in developed nations. Sub-national variations are also critical; for instance, in Malaysia, the state of Kelantan has a prevalence of 39%, compared to 13.6% in Selangor and Kuala Lumpur [4]. Longitudinal data from Eswatini shows remarkable persistence of IPIs, with an overall prevalence of 43.0% in 2019 and 42.2% in 2022, despite the disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic [11]. This stability suggests deeply entrenched environmental and socioeconomic drivers. Furthermore, the species composition can shift over time, as observed in Eswatini where Giardia intestinalis infections declined while Blastocystis hominis increased [11], highlighting the dynamic nature of parasitic ecology.

Regional Case Studies

The Malaysian Context: A Meta-Analytical Perspective

Malaysia presents a compelling case study of a rapidly developing nation where IPIs remain a significant burden, particularly among its most vulnerable populations. A comprehensive meta-analysis of 49 studies revealed a national pooled IPI prevalence of 24% [4] [13]. The primary pathogens identified were Entamoeba spp. (18%), G. lamblia (11%), and Cryptosporidium spp. (9%). The highest disease burden was concentrated in indigenous communities (27%) and rural areas (23%), with significant regional disparities observed [4]. Key risk factors identified through meta-analysis include being a child under 15 years of age, male gender, low income, lack of formal education, and exposure to untreated water and poor sanitation [4]. These factors collectively underscore the role of socioeconomic development and infrastructure in determining disease patterns.

Sub-Saharan Africa: Longitudinal Insights from Eswatini

A prospective cohort study in Eswatini followed 128 schoolchildren from 2019 to 2022, providing valuable longitudinal data on IPI trends [11]. The study found that protozoan infections predominated, while helminth infections remained low (<2.5%). A critical finding was the significant association between socioeconomic status and infection risk: children with only one employed parent had nearly four times higher odds of infection (aOR = 3.97) and over four times higher odds of pathogenic protozoan infection (aOR = 4.33) in 2022 [11]. While handwashing before meals was a protective factor in 2019 (aOR = 0.10), this association was not significant in 2022, potentially indicating behavioral shifts during the pandemic. This case highlights how household-level socioeconomic pressures can be a more significant determinant of infection risk than individual hygiene practices in high-burden settings.

Experimental and Surveillance Methodologies

Robust epidemiological and laboratory protocols are fundamental to characterizing IPI endemicity. The following section details standardized methodologies cited in recent literature.

Cross-Sectional Survey Design and Sample Collection

Cross-sectional surveys are a cornerstone of IPI surveillance. The study in Simada, Ethiopia, provides a representative protocol [7].

- Participant Recruitment: A health facility-based cross-sectional study can be employed, recruiting participants who visit a central health clinic over a defined period (e.g., February to April 2023).

- Data Collection: A standardized, pre-tested questionnaire administered via interview collects data on socio-demographics (age, occupation, income), hygiene behaviors (handwashing habits, water source), and household environmental factors.

- Sample Collection and Transport: Each participant provides a fresh stool sample in a wide-mouthed, clean, leak-proof container. Samples are labeled with unique identifiers and transported in cool boxes to the parasitology laboratory for processing, ideally on the same day.

Laboratory Diagnostic Techniques

Accurate diagnosis is critical for surveillance and research. The following techniques are widely used, often in combination.

- Direct Wet Mount Microscopy: A small amount of stool is emulsified with a drop of saline (0.85% NaCl) and/or iodine on a microscope slide and examined under x10 and x40 objectives for motile trophozoites, cysts, oocysts, and helminth eggs. This method is rapid but has low sensitivity [7].

- Formol-Ether Concentration Technique (FECT): This sedimentation method increases the yield of parasites. An emulsified stool sample is filtered into a tube and mixed with formalin (to preserve) and ether (to dissolve fats and debris). The mixture is centrifuged, and the sediment is examined microscopically. This was a key method used in the Ethiopian study [7].

- Merthiolate-Iodine-Formaldehyde (MIF) Staining and Concentration: Used in the Eswatini cohort, the MIF method involves staining and fixing stool samples, which allows for the identification of eggs, cysts, and trophozoites, improving morphological differentiation [11].

- Molecular Methods (PCR): Molecular approaches, such as real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), offer superior sensitivity and specificity, and can differentiate between pathogenic and non-pathogenic species (e.g., E. histolytica vs. E. dispar). While not used in all field studies, they are considered the gold standard in research settings [3].

Diagram: Integrated Workflow for IPI Surveillance and Research. This diagram outlines the sequential and parallel processes in a comprehensive IPI study, from population definition to public health action, highlighting the integrated role of different diagnostic techniques. FECT: Formol-Ether Concentration Technique; MIF: Merthiolate-Iodine-Formaldehyde.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

A standardized set of reagents and materials is essential for conducting field and laboratory research on IPIs. The following table details key items and their applications based on the methodologies described in the search results.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for IPI Investigation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Protocol/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Merthiolate-Iodine-Formaldehyde (MIF) Solution | Staining and preservation of parasitic elements (cysts, eggs, trophozoites) in stool samples for microscopic examination. | Used in the Eswatini cohort study [11]. Compatible with commercial kits (e.g., Para Quick). |

| Formalin (10% Buffered) | Primary fixative and preservative for stool samples, killing pathogens and stabilizing morphology for concentration techniques and biobanking. | Used in Formol-Ether Concentration Technique (FECT) [7]. |

| Diethyl Ether | Used in FECT to dissolve dietary fats and debris, clearing the sample and concentrating parasitic elements in the sediment. | Added to the formalin-fixed sample prior to centrifugation [7]. |

| Saline (0.85% NaCl) | Isotonic solution for creating direct wet mounts to observe motile trophozoites and for initial sample emulsification. | Used for initial microscopic screening [7]. |

| Lugol's Iodine Solution | Stains glycogen and nuclei of protozoan cysts, enhancing microscopic visualization and identification. | Applied in wet mount or as part of staining procedures like MIF. |

| DNA Extraction Kits (Stool-specific) | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA from complex stool matrices for subsequent molecular assays. | Critical step prior to PCR. |

| PCR Master Mix & Species-Specific Primers/Probes | Amplification and detection of parasite-specific DNA sequences for highly sensitive and specific identification and differentiation. | Enables detection of pathogens like C. parvum and differentiation of E. histolytica from E. dispar [3]. |

Pathogen Transmission and Host Interaction Pathways

Understanding the life cycles and host interactions of intestinal protozoa is vital for developing effective interventions. The following diagram illustrates the key pathways from environmental transmission to disease outcome.

Diagram: IPI Transmission and Disease Pathway. This diagram maps the progression from underlying socioeconomic and environmental drivers, through faecal-oral transmission and pathogen-specific mechanisms, to acute and chronic health outcomes. Key risk factors from the analysis (poverty, poor sanitation) are shown as primary drivers.

The comparative analysis of regional hotspots for intestinal protozoan infections underscores a persistent and significant public health burden in tropical regions, directly linked to socioeconomic disparities. The high prevalence rates reported in countries like Malaysia, Eswatini, and Ethiopia—often exceeding 20% and reaching over 50% in specific districts—stand in stark contrast to the situation in developed nations [11] [4] [7]. The evidence clearly identifies poverty, inadequate sanitation, lack of access to clean water, and low education levels as the fundamental drivers of this endemicity. For researchers and drug development professionals, addressing this challenge requires a multi-faceted approach. This includes implementing robust surveillance using standardized protocols, developing and deploying point-of-care diagnostics, and pursuing new therapeutic agents. Furthermore, the findings advocate for integrated control strategies that extend beyond the health sector, encompassing improvements in water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure and targeted health education. Sustained research efforts and evidence-based interventions are critical to reducing the disproportionate burden of these neglected infections and achieving global health equity.

The epidemiology of intestinal protozoan infections represents a significant field of study within global public health, particularly in resource-limited settings. These infections, caused by pathogenic protozoa such as Giardia duodenalis, Entamoeba histolytica, and Cryptosporidium spp., contribute substantially to the global burden of gastrointestinal diseases, especially among vulnerable populations in developing regions [14] [15]. The World Health Organization estimates that approximately 450 million people suffer from these infections, with disproportionate impacts on children in low- and middle-income countries where sanitation infrastructure and healthcare access remain limited [16] [13].

The transmission dynamics of intestinal protozoa are intricately linked to socioeconomic conditions, with poverty serving as a fundamental determinant of infection risk. These pathogens primarily spread through the fecal-oral route via contaminated water, food, environmental surfaces, and direct person-to-person contact [17] [18]. Consequently, populations experiencing inadequate water sanitation, poor hygiene practices, and limited education face elevated exposure risks, creating persistent cycles of infection and retransmission within communities [15] [19].

This technical guide examines the complex interrelationships between socioeconomic determinants and intestinal protozoan infection rates, with particular focus on poverty, educational attainment, and sanitation infrastructure. Through systematic analysis of current epidemiological data and research methodologies, this review aims to provide researchers and public health professionals with evidence-based insights to inform targeted intervention strategies and drug development priorities for high-risk populations.

Socioeconomic Determinants and Epidemiological Patterns

Poverty and Economic Status

Economic disadvantage consistently demonstrates a strong correlation with increased prevalence of intestinal protozoan infections across multiple geographical regions. Low income directly constrains access to essential resources including safe water, sanitary facilities, and healthcare services, thereby creating favorable conditions for parasite transmission and persistence.

Table 1: Economic Status and Protozoan Infection Rates

| Region | Economic Indicator | Infection Rate/Association | Primary Protozoa Identified |

|---|---|---|---|

| Egypt | Low socioeconomic status | RR = 2.4 (95% CI: 1.8-3.2) [19] | Entamoeba spp., Giardia duodenalis |

| MENA Region | Low income | Generally associated with higher parasitic infection rates [14] | Giardia lamblia, Blastocystis hominis |

| Eastern Tigrai, Ethiopia | Using well water (poverty proxy) | Significant risk factor (p<0.05) [15] | E. histolytica/dispar, G. duodenalis |

| Malaysia | Low income | 38-52% higher prevalence [13] | Entamoeba spp., Giardia lamblia |

| Ethiopia (University students) | Pocket money ≤347 Birr/month | Increased risk (AOR = 0.20 for higher income) [18] | E. histolytica/E. dispar |

The relationship between poverty and infection risk manifests through multiple pathways. In Egypt, a comprehensive meta-analysis revealed that children from low socioeconomic households had 2.4 times higher risk of intestinal parasitic infections compared to their more affluent counterparts [19]. Similarly, in the MENA region, low income was generally associated with higher rates of parasitic infections, particularly in Egypt, Palestine, Lebanon, and Iran [14]. The economic barrier extends beyond household resources to community-level infrastructure, as demonstrated in Eastern Tigrai, Ethiopia, where using well water as a drinking source – a marker of limited municipal water access – emerged as a significant risk factor for protozoan infections [15].

Educational Attainment

Education level, particularly maternal education, serves as a powerful determinant of intestinal protozoan infection risk through its influence on health knowledge, hygiene practices, and healthcare-seeking behaviors.

Table 2: Educational Factors and Infection Associations

| Region | Educational Factor | Association with Infection | Statistical Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Egypt | Low maternal education | RR = 1.62 [19] | Risk Ratio |

| MENA Region | Lower education levels | Higher infection rates (Egypt, Iran, Qatar) [14] | Significant association |

| Ethiopia (University students) | Educated father | Lower risk (AOR = 0.62, 95% CI: 0.12-0.86) [18] | Adjusted Odds Ratio |

| Sanandaj City, Iran | Parental education | No significant association [20] | P>0.05 |

| Malaysia | No formal education | 38-52% higher prevalence [13] | Pooled prevalence |

The protective effect of education demonstrates variability across different cultural and regional contexts. In Egypt, low maternal education was associated with a 1.62 times higher risk of intestinal parasitic infections in children [19]. Similarly, in the MENA region, individuals with lower education levels generally showed higher infection rates, though some studies reported no significant association, indicating potential mediating factors such as community-level health education programs or environmental conditions [14]. The relationship between paternal education and infection risk among Ethiopian university students further underscores the intergenerational educational influence on health outcomes, with students having educated fathers demonstrating significantly lower infection rates [18].

Sanitation and Hygiene Infrastructure

Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) conditions represent critical environmental determinants of intestinal protozoan transmission, with inadequate infrastructure consistently associated with elevated infection prevalence across multiple studies.

Table 3: Sanitation and Hygiene-Related Risk Factors

| Risk Factor | Region | Associated Measure | Protozoa Involved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor handwashing after toilet use | Jalalabad, Afghanistan | AOR = 5.37 (95% CI: 2.34-12.31) [17] | Giardia lamblia, E. histolytica |

| Poor handwashing before eating | Jalalabad, Afghanistan | AOR = 6.65 (95% CI: 3.89-11.37) [17] | Giardia lamblia, E. histolytica |

| Unwashed raw vegetable consumption | Jalalabad, Afghanistan | AOR = 28.83 (95% CI: 5.50-151.03) [17] | Giardia lamblia, E. histolytica |

| Not having home latrine | Eastern Tigrai, Ethiopia | Significant risk factor (p<0.05) [15] | E. histolytica/dispar, G. duodenalis |

| Untreated water exposure | Malaysia | 38-52% higher prevalence [13] | Entamoeba spp., Giardia |

The impact of inadequate sanitation manifests most dramatically in conflict-affected and humanitarian settings. In Jalalabad, Afghanistan, researchers documented striking risk elevations associated with poor hygiene practices, including a 28.83-fold increased infection risk among children consuming unwashed raw vegetables and 6.65-fold higher risk among those with inadequate handwashing before eating [17]. The absence of home latrines in Eastern Tigrai, Ethiopia, significantly increased protozoan infection risk, highlighting the importance of basic sanitation infrastructure in interrupting fecal-oral transmission cycles [15]. These findings collectively underscore the fundamental role of WASH interventions in comprehensive protozoan infection control strategies.

Research Methodologies and Protocols

Field Study Design and Epidemiological Assessment

Conducting robust epidemiological research on socioeconomic determinants and intestinal protozoan infections requires meticulous study design and standardized protocols to ensure data comparability across different populations and regions.

Cross-sectional Survey Protocol: The predominant study design for investigating socioeconomic determinants of intestinal protozoan infections is the cross-sectional survey, which provides prevalence estimates at a specific point in time [20] [17] [15]. The standardized protocol includes:

- Stratified Random Sampling: Implement multistage stratified random sampling to ensure representative population coverage across diverse socioeconomic strata [17]. Administrative zones serve as primary stratification units, followed by random selection of schools or communities within each zone.

- Standardized Questionnaire Administration: Administer pre-tested, structured questionnaires to collect demographic and socioeconomic data [17] [15]. Key variables include household income, parental education and occupation, water source, sanitation facilities, housing conditions, and hygiene behaviors.

- Sample Size Calculation: Determine minimum sample sizes using single-proportion formula with 95% confidence level, 80% power, and 4-5% margin of error [17] [15]. Account for potential non-response rates by oversampling by 10%.

- Ethical Considerations: Obtain ethical approval from institutional review boards and secure informed consent from all participants or guardians [17]. Maintain confidentiality of participant data through anonymization and secure storage.

Cohort Study Design: Longitudinal cohort studies provide valuable insights into causal relationships between socioeconomic factors and infection incidence [19]. Implementation includes:

- Baseline Assessment: Document socioeconomic status and potential confounders before follow-up period.

- Regular Follow-up: Conduct repeated stool examinations and symptom assessments at predetermined intervals (typically 3-6 months).

- Incidence Calculation: Track new infections among initially negative participants to calculate incidence rates across different socioeconomic strata.

Laboratory Diagnostic Techniques

Accurate parasite identification and quantification are essential for reliable assessment of infection prevalence and intensity. Standardized laboratory protocols ensure comparability across studies.

Stool Sample Collection and Processing Protocol:

- Sample Collection: Distribute labeled, leak-proof containers to participants with instructions to collect approximately 2g of fresh stool [17] [15]. For liquid stools, collect 5-6mL samples. Ensure samples are processed within 30-60 minutes of collection or preserved appropriately.

- Macroscopic Examination: Document stool consistency, color, presence of mucus or blood before microscopic analysis [16].

- Direct Wet Mount Preparation:

- Prepare normal saline (0.9%) and Lugol's iodine solutions

- Emulsify rice grain-sized stool sample in saline on microscope slide

- Apply coverslip and examine systematically under 10x and 40x objectives

- Repeat procedure with iodine solution for cyst identification [16]

- Formalin-Ether Concentration Technique:

- Modified Acid-Fast Staining: For identification of Cryptosporidium spp. and Cyclospora cayetanensis:

- Prepare thin stool smears on microscope slides

- Fix with methanol for 3 minutes

- Flood with carbol fuchsin for 15 minutes

- Decolorize with acid-alcohol for 30 seconds

- Counterstain with methylene blue for 1 minute

- Examine under 100x oil immersion objective [16]

Quality Control Measures: Implement rigorous quality control procedures including:

- Parallel examination of samples by two trained microscopists

- Regular proficiency testing with known positive and negative samples

- Random re-examination of 10% of samples by senior technologist

- Calibration and maintenance of laboratory equipment [17] [15]

Data Analysis and Statistical Approaches

Robust statistical analysis is crucial for elucidating relationships between socioeconomic variables and infection outcomes while controlling for potential confounders.

Primary Analytical Framework:

- Prevalence Calculation: Compute overall and species-specific prevalence rates with 95% confidence intervals using the formula: Number positive/Total examined × 100 [17] [19].

- Bivariate Analysis: Conduct initial screening of associations between socioeconomic factors and infection status using Chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables [15].

- Multivariable Logistic Regression: Construct models to identify independent socioeconomic predictors while controlling for confounding variables [17] [19]. Include variables with p<0.20 from bivariate analysis in initial models, using backward elimination to retain significant predictors (p<0.05) in final models.

- Measures of Association: Report adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% confidence intervals for significant predictors in final models [17].

Advanced Analytical Techniques:

- Meta-Analysis Methods: For systematic reviews, employ random-effects models using inverse variance weighting to calculate pooled prevalence estimates and risk ratios [19] [13]. Assess heterogeneity using I² statistic, with values >75% indicating substantial heterogeneity.

- Meta-Regression Analysis: Examine temporal trends in prevalence using meta-regression with publication year as continuous variable [19].

- Sensitivity Analysis: Evaluate robustness of findings using leave-one-out approach to determine if results are unduly influenced by individual studies [19].

Visualizing Transmission Pathways and Determinants

The complex relationships between socioeconomic determinants and intestinal protozoan infection risk can be visualized through a comprehensive transmission pathway diagram.

Figure 1: Socioeconomic Determinants of Intestinal Protozoan Infection Transmission Pathways. This diagram illustrates the complex pathways through which poverty, limited education, and inadequate sanitation infrastructure contribute to increased exposure and susceptibility to intestinal protozoan infections, ultimately leading to adverse health outcomes.

Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Protozoan Infection Studies

| Reagent/Material | Application | Technical Specifications | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formalin (10%) | Stool preservation and concentration procedures | 100mL formaldehyde (37-40%) in 900mL distilled water; neutral buffered [17] [15] | Fixation of parasites for morphological preservation during transport and storage |

| Ethyl Acetate | Parasite concentration via formalin-ether technique | Laboratory grade, ≥99.5% purity [17] [15] | Lipid extraction and debris clarification in concentration methods |

| Carbol Fuchsin | Acid-fast staining of Cryptosporidium and Cyclospora | Basic fuchsin (0.3%), phenol (5%) in ethanol (10%) [16] | Differentiation of acid-fast intestinal protozoa from non-acid-fast organisms |

| Lugol's Iodine Solution | Staining of protozoan cysts for microscopy | Iodine (5%), potassium iodide (10%) in distilled water [16] | Enhanced visualization of internal cyst structures including nuclei and glycogen vacuoles |

| Microscope Slides and Coverslips | Preparation of wet mounts and stained smears | Pre-cleaned glass slides (75x25mm); #1 thickness coverslips (22x22mm) [17] | Standardized preparation for microscopic examination at 100x-400x magnification |

| Centrifuge | Parasite concentration procedures | Standard clinical centrifuge with 15mL tube capacity; adjustable 500-2000xg [15] | Sedimentation of parasites during formalin-ether concentration technique |

Discussion and Research Implications

The synthesized evidence demonstrates consistent and strong associations between socioeconomic determinants and intestinal protozoan infection rates across diverse geographical and cultural contexts. The interrelationships between poverty, education, and sanitation create complex pathways that perpetuate disproportionate disease burdens among disadvantaged populations.

Public Health and Research Implications

The epidemiological patterns observed across multiple studies highlight several critical considerations for public health interventions and future research directions. First, the consistent association between poverty and infection risk underscores the necessity of poverty alleviation as a fundamental component of parasitic disease control [14] [19]. Second, the variable protective effects of education across different regions suggest the importance of contextualized health education programs that address specific local knowledge gaps and behavioral practices [14] [18]. Third, the dramatic risk elevations associated with inadequate sanitation infrastructure emphasize the imperative of WASH investments as foundational public health measures [17] [15].

From a research perspective, several methodological considerations emerge. The heterogeneity in socioeconomic metrics across studies complicates direct comparisons and meta-analyses, highlighting the need for standardized socioeconomic indicators in parasitological research [14] [19]. Additionally, the complex interrelationships between different socioeconomic determinants necessitate multivariate analytical approaches that can elucidate independent effects while accounting for potential confounding [17] [19]. Future research should also prioritize longitudinal designs to establish temporal relationships and causal pathways between socioeconomic factors and infection risk.

Methodological Considerations and Limitations

Current research on socioeconomic determinants of intestinal protozoan infections faces several methodological challenges. The cross-sectional design predominant in existing literature provides valuable prevalence estimates but limits causal inference regarding socioeconomic risk factors [20] [17] [15]. The heterogeneity in socioeconomic measurement across studies complicates comparative analyses and meta-analytic approaches [14] [19]. Additionally, diagnostic sensitivity varies considerably between direct wet mount and concentration techniques, potentially underestimating true prevalence, particularly for low-intensity infections [17] [16].

Regional research gaps also present limitations, with disproportionate representation from certain endemic areas and underrepresentation of others [14] [19] [13]. Furthermore, many studies focus primarily on children or specific subpopulations, limiting generalizability to broader community contexts. Future research should address these limitations through standardized socioeconomic metrics, optimized diagnostic approaches incorporating molecular methods where feasible, and expanded geographical coverage to include underrepresented endemic regions.

This technical review establishes robust evidence linking socioeconomic determinants—particularly poverty, limited education, and inadequate sanitation—to increased risk of intestinal protozoan infections. The synthesized data demonstrate that economically disadvantaged populations face substantially elevated infection risks, with low income associated with 2.4-fold higher infection rates in Egypt [19], and specific hygiene-related practices showing even more dramatic risk elevations in high-transmission settings like Afghanistan [17].

The relationships between these determinants operate through complex pathways involving constrained resources, limited health knowledge, and inadequate infrastructure that collectively increase exposure frequency and decrease protective behaviors. Effective intervention strategies must address these interconnected determinants through multidimensional approaches that combine poverty alleviation, educational investment, and sanitation infrastructure development.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings highlight the importance of considering socioeconomic context in clinical trial design, intervention development, and public health programming. Future research should prioritize standardized socioeconomic metrics, longitudinal designs to establish causal pathways, and intervention studies that address multiple determinants simultaneously. Through integrated approaches that address both biological and social determinants of health, substantial progress can be made toward reducing the disproportionate burden of intestinal protozoan infections among vulnerable populations worldwide.

Intestinal protozoan infections, primarily caused by Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia lamblia, and Cryptosporidium species, represent a significant global health burden, disproportionately affecting specific population groups. These infections are transmitted via the fecal-oral route through contaminated food, water, or direct contact, causing symptoms ranging from self-limiting diarrhea to severe, life-threatening complications [21] [22] [13]. Current global estimates indicate approximately 3.5 billion people are affected, with around 450 million individuals currently symptomatic [21] [22]. This technical review examines the epidemiological evidence defining children, immunocompromised individuals, and Indigenous communities as high-risk populations, analyzes the biological and socioeconomic factors driving vulnerability, and outlines essential research methodologies for advancing evidence-based interventions within public health frameworks.

Epidemiological Profile of Major Intestinal Protozoa

The three primary protozoan pathogens responsible for the majority of intestinal infections demonstrate distinct geographical distributions and clinical manifestations, yet collectively contribute to substantial disease burden across vulnerable populations.

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Intestinal Protozoan Pathogens

| Pathogen | Disease | Key Clinical Manifestations | At-Risk Populations | Global Burden |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entamoeba histolytica | Amoebiasis | Abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea, fever, liver abscesses | Children, Indigenous communities | 50 million annual cases; 100,000 deaths [21] [22] |

| Giardia lamblia | Giardiasis | Watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, flatulence, weight loss | Children in tropical regions | ~200 million annual infections [21] [22] |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | Cryptosporidiosis | Watery diarrhea, stomach cramps, nausea, vomiting | Immunocompromised individuals, children | Prevalence: 13% (India), 7.3% (Thailand) in children [21] [22] |

Vulnerability Analysis of High-Risk Populations

Pediatric Vulnerability

Children, particularly those under five years of age, bear a disproportionate burden of intestinal protozoan infections due to a combination of immunological, behavioral, and environmental factors. In Malaysia, diarrheal diseases remain a leading cause of mortality in children under 5, with a reported mortality rate of 0.8% in 2019 [21] [22]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of intestinal protozoal infections in Malaysia identified children under 15 years as having significantly higher pooled prevalence rates, between 38% and 52%, with the highest burden observed among indigenous pediatric populations [13].

The increased susceptibility in children stems from several key factors:

- Immature immune systems: Developing adaptive immunity limits capacity to combat protozoan pathogens effectively

- Behavioral factors: Poor hand hygiene practices and frequent hand-to-mouth contact increase ingestion of infectious cysts

- Environmental exposure: Higher likelihood of contact with contaminated soil and water during play

- Nutritional status: Pre-existing malnutrition compromises intestinal barrier function and immune competence

Immunocompromised Individuals

Immunocompromised patients, particularly those with HIV/AIDS, organ transplants, or immunosuppressive therapy, experience more severe and prolonged manifestations of intestinal protozoan infections. Cryptosporidiosis demonstrates particularly aggressive courses in immunocompromised hosts, with potential for chronic, life-threatening diarrhea and extra-intestinal dissemination [13].

Malaysian studies have documented the heightened vulnerability in immunocompromised populations:

- HIV-positive inmates demonstrated 27.5% prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections compared to 25.8% in HIV-negative inmates [13]

- Intravenous drug users with HIV showed increased rates of cryptosporidiosis, though often asymptomatic [13]

- The clinical severity of infection correlates with degree of immunosuppression, particularly CD4+ T-cell counts in HIV patients

The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying increased severity in immunocompromised hosts include:

- Defective cell-mediated immunity: Crucial for controlling intracellular protozoa like Cryptosporidium

- Reduced IgA secretion: Compromises mucosal barrier function in the gastrointestinal tract

- Dysregulated inflammatory responses: May lead to excessive tissue damage or inadequate pathogen clearance

Indigenous Communities

Indigenous populations globally experience disproportionate burdens of intestinal protozoan infections, driven by historical, socioeconomic, and structural determinants of health. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted persistent health inequities, with Native Americans experiencing 2.1-times higher mortality compared to White Americans [23]. Similar disparities exist for other infectious diseases, reflecting systemic factors rather than biological susceptibility.

Table 2: Documented Health Disparities in Indigenous Populations

| Health Indicator | Indigenous Population | Comparison Population | Disparity Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 mortality | Native Americans | White Americans | 2.1-times higher [23] |

| Influenza hospitalization | First Nations (Canada) | General Canadian population | 4-5-times higher [23] |

| RSV hospitalization | Inuit infants (Nunavut) | Temperate region infants | 484 vs. 27 per 1,000 [23] |

| Invasive infection ICU admissions | Indigenous children (Australia) | Non-Indigenous children | 47.6 vs. ~17.3 per 100,000 [24] |

The structural determinants driving these disparities include:

- Inadequate infrastructure: Lack of access to clean water and sanitation facilities in many Indigenous communities

- Household crowding: Facilitates fecal-oral transmission of pathogens

- Poverty and food insecurity: Higher prevalence of underlying comorbidities that worsen infection outcomes

- Historical trauma and systemic discrimination: Creates barriers to healthcare access and undermines trust in health systems

- Underfunded health services: Limited capacity for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment

In Malaysia, studies documented a 27% prevalence of intestinal protozoan infections in indigenous communities, compared to 23% in local rural communities [13]. Subnational analysis revealed the highest prevalence in Kelantan state (39%), followed by Perak (29%), with urban centers like Selangor and Kuala Lumpur reporting lower rates (13.6%) [13].

Research Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocol

Recent comprehensive reviews have established rigorous methodologies for synthesizing epidemiological data on intestinal protozoan infections [21] [22] [13]. The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework provides standardized guidelines for conducting and reporting systematic reviews in this field.

Table 3: Key Methodological Components for Systematic Reviews of Intestinal Protozoan Infections

| Component | Specifications | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Search Strategy | Multi-database search (PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar, Cochrane); No language restrictions; Inclusion of grey literature | Search terms: medical subject headings (MeSH) + free-text for giardiasis, cryptosporidiosis, amoebiasis, prevalence, epidemiology, risk factors [21] [22] |

| Eligibility Criteria | Studies with original data; Human subjects; Specific diagnostic methods; Defined timeframes (e.g., 2010-2024) | Exclusion of case reports, reviews; Focus on E. histolytica, G. lamblia, Cryptosporidium spp. [21] [22] [13] |

| Risk of Bias Assessment | Joanna Briggs Institute tools; Newcastle-Ottawa Scale | Evaluation of selection, detection, and reporting biases in included studies [21] [22] |

| Data Synthesis | Random effects model; Pooled prevalence with 95% CI; Subgroup analysis; Meta-regression | Calculation of overall prevalence; Analysis by region, population, diagnostic method [13] |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the systematic review process:

Diagnostic Methodologies

Accurate diagnosis of intestinal protozoan infections requires appropriate methodological selection based on clinical context, available resources, and research objectives. The following diagram illustrates the diagnostic workflow:

Table 4: Diagnostic Methods for Intestinal Protozoan Infections

| Method | Principles | Advantages | Limitations | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopy | Direct visualization of cysts/trophozoites in stool samples | Low cost; Widely available; Can detect multiple parasites | Low sensitivity; Requires expertise; Cannot differentiate species | Initial screening; Resource-limited settings [21] [22] |

| Immunoassays | Detection of parasite-specific antigens in stool | Higher sensitivity than microscopy; Rapid tests available | Species-specific; Limited multiplexing | Outbreak investigations; Clinical diagnostics [21] [22] |

| Molecular Methods (PCR, qPCR) | Amplification of parasite-specific DNA sequences | High sensitivity and specificity; Species differentiation; Quantification possible | Higher cost; Technical expertise required; Equipment needs | Research; Surveillance; Species confirmation [21] [22] [13] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Intestinal Protozoan Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stool Preservation Solutions | 10% Formalin, Sodium acetate-acetic acid-formalin (SAF), Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) | Maintain parasite morphology for microscopy; Preserve nucleic acids for molecular assays | Choice affects downstream applications; Formalin-fixed samples suitable for microscopy and PCR [21] [22] |

| DNA/RNA Extraction Kits | Commercial kits with bead-beating steps (mechanical disruption) | Break cyst walls to release nucleic acids; Purify DNA/RNA for molecular assays | Mechanical disruption crucial for efficient extraction; Inhibitor removal essential for clinical samples [21] [22] [13] |

| PCR Master Mixes | Multiplex real-time PCR kits; Conventional PCR reagents | Simultaneous detection of multiple pathogens; Species differentiation; Quantification | Multiplexing requires careful primer/probe design; Include internal controls to detect inhibition [21] [22] [13] |

| Primary Antibodies | Species-specific monoclonal antibodies (e.g., anti-Giardia cyst wall protein) | Immunofluorescence; ELISA development; Histological detection | Commercial availability varies by species; Cross-reactivity testing required [21] [22] |

| Reference Genomic DNA | ATCC reference strains for each protozoan species | Positive controls for molecular assays; Assay validation; Quality control | Essential for validating in-house PCR assays; Confirms specificity and sensitivity [21] [22] [13] |

The epidemiological evidence clearly identifies children, immunocompromised individuals, and Indigenous communities as disproportionately affected by intestinal protozoan infections. Biological factors, including immune status and developmental stage, interact with socioeconomic determinants, such as poverty, inadequate sanitation, and limited healthcare access, to create intersecting vulnerabilities. The pooled prevalence of 24% identified in the Malaysian systematic review underscores the substantial disease burden in endemic regions, with even higher rates (27%) documented among Indigenous populations [13]. Addressing these disparities requires multifaceted approaches combining improved diagnostic methodologies, targeted public health interventions, and research that specifically addresses the structural determinants of health in vulnerable communities. Future research priorities should include development of point-of-care diagnostics, implementation research on effective intervention delivery, and community-engaged studies that prioritize Indigenous knowledge and self-determination in research partnerships.

Intestinal protozoan infections represent a significant global health burden, affecting billions of individuals worldwide and causing substantial morbidity and mortality, particularly in vulnerable populations and resource-limited settings [3] [4]. The transmission dynamics of these pathogens are complex, involving multiple interconnected pathways including waterborne, foodborne, and zoonotic routes. Understanding these dynamics is fundamental to developing effective public health interventions, diagnostic approaches, and therapeutic strategies. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the transmission mechanisms, epidemiological patterns, and laboratory methodologies relevant to major intestinal protozoa, with a specific focus on Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia lamblia (also known as G. duodenalis or G. intestinalis), and Cryptosporidium species [3] [25]. These pathogens collectively contribute to a substantial portion of the global intestinal protozoal infection burden, with an estimated 3.5 billion people affected and approximately 450 million currently experiencing active infections [3] [4]. The epidemiological significance of these parasites extends beyond their prevalence, as they are responsible for severe diarrheal diseases, nutritional deficiencies, and impaired cognitive development in children, creating a cycle of disease and poverty that disproportionately affects developing regions [4] [25].

Major Pathogens and Clinical Manifestations

The clinical presentation of intestinal protozoal infections varies significantly based on the causative organism, infectious dose, and host immune status. Entamoeba histolytica, the causative agent of amoebiasis, invades the intestinal mucosa leading to characteristic symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea (dysentery), fever, and in severe cases, liver abscesses [3] [25]. The organism's ability to form flask-shaped ulcers in the colonic mucosa and disseminate to extra-intestinal sites represents a significant virulence mechanism that distinguishes it from non-pathogenic amoeba species [25]. Giardia lamblia causes giardiasis, which typically presents with abundant, foul-smelling, watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, flatulence, and weight loss without invasive disease [3] [25]. The parasite attaches to the intestinal epithelium without tissue invasion, but induces malabsorption and nutrient deficiency through mechanisms that remain partially understood [25].

Cryptosporidium species, particularly C. parvum and C. hominis, cause cryptosporidiosis, which manifests as watery diarrhea accompanied by stomach cramps, nausea, vomiting, and fever [3] [4]. This pathogen poses a particularly severe threat to immunocompromised individuals, including those with HIV/AIDS, where infections can become chronic, life-threatening, and refractory to treatment [4]. The parasite's unique intracellular but extracytoplasmic localization within host epithelial cells contributes to its resistance to many conventional antiprotozoal therapies and enables robust environmental transmission through highly resistant oocysts [25].

Table 1: Major Intestinal Protozoan Pathogens and Clinical Features

| Pathogen | Disease | Primary Symptoms | Severe Complications | High-Risk Populations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entamoeba histolytica | Amoebiasis | Bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever | Liver abscess, amoeboma, perforation | All age groups, tropical regions |

| Giardia lamblia | Giardiasis | Watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, flatulence, weight loss | Malabsorption syndrome, chronic diarrhea | Children, travelers, immunocompromised |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | Cryptosporidiosis | Watery diarrhea, stomach cramps, nausea, vomiting | Protracted diarrhea, biliary involvement | HIV/AIDS, young children |

| Toxoplasma gondii | Toxoplasmosis | Often asymptomatic, flu-like symptoms | Congenital defects, encephalitis in immunocompromised | Fetus, HIV/AIDS, transplant recipients |

The differential diagnosis of these infections is challenging because most enteric pathogens cause similar symptomatology, leading to potential misidentification without proper laboratory confirmation [3] [4]. Multiple infectious agents can cause acute gastroenteritis, and contamination may originate from food, water, the environment, or animals, further complicating epidemiological analysis and outbreak investigations [4]. The severity of disease ultimately depends on the immune status of affected individuals, with immunocompromised patients experiencing more severe and protracted illnesses [3].

Transmission Pathways and Epidemiology

Waterborne Transmission

Waterborne transmission represents a predominant pathway for the global dissemination of intestinal protozoan pathogens, particularly Giardia and Cryptosporidium [26]. These organisms produce environmentally resistant cysts (for Giardia and Entamoeba) or oocysts (for Cryptosporidium) that can survive for extended periods in water and are highly resistant to conventional water treatment methods, including chlorine-based disinfection [26]. A comprehensive review of global waterborne protozoan outbreaks from 2017 to 2020 identified 251 outbreaks worldwide, with the majority (57.77%) occurring in the Americas, followed by Europe (29.48%), Oceania (11.16%), and Asia (1.59%) [26]. The disproportionate representation of developed countries in these statistics reflects their advanced diagnostic capabilities and surveillance systems rather than actual higher incidence, highlighting significant surveillance bias and underreporting in resource-limited regions [26].

Recreational water venues, including swimming pools, water parks, and interactive fountains, have emerged as significant transmission vehicles in developed countries, primarily due to inadequate disinfection and contamination events [26]. The robust nature of protozoan cysts and oocysts enables their survival in properly chlorinated water, facilitating point-source outbreaks that can affect numerous individuals simultaneously. Additionally, drinking water contamination continues to pose a substantial threat, particularly in regions with compromised water treatment infrastructure or agricultural runoff that introduces zoonotic strains into water sources [26]. The traditional water treatment processes, including coagulation, sedimentation, filtration, and disinfection, have demonstrated variable efficacy against protozoan parasites, with filtration representing the most reliable barrier against these pathogens [26].

Foodborne Transmission

Foodborne transmission of intestinal protozoa occurs through the contamination of raw or ready-to-eat foods with infective cysts or oocysts, typically via contact with contaminated water, soil, or infected food handlers practicing poor personal hygiene [3] [4]. Fresh produce, including leafy greens, berries, and herbs, represents a particularly high-risk commodity due to potential contamination at multiple points along the production chain, from irrigation with contaminated water to processing and preparation [4]. The robust nature of protozoan transmission stages enables their survival on food surfaces and resistance to various food preservation methods, including refrigeration and mild disinfectants.

Foodborne outbreaks often prove challenging to investigate and attribute to specific protozoan pathogens due to several factors: the relatively low infectious doses required for some species (as few as 10-100 cysts for Giardia); the prolonged incubation periods that complicate traceback investigations; and the limited implementation of protozoan testing in routine food safety monitoring programs [4]. Molecular typing methods have enhanced our ability to link clinical, food, and environmental isolates during outbreak investigations, providing valuable insights into transmission chains and contamination sources.

Zoonotic and Environmental Transmission