Self-Supervised Learning and AI Strategies to Reduce Manual Labeling in Parasite Image Analysis

Manual labeling of parasite microscopy images is a major bottleneck in developing AI-based diagnostic tools, consuming significant time and expert resources.

Self-Supervised Learning and AI Strategies to Reduce Manual Labeling in Parasite Image Analysis

Abstract

Manual labeling of parasite microscopy images is a major bottleneck in developing AI-based diagnostic tools, consuming significant time and expert resources. This article explores innovative strategies to minimize this dependency, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. We first establish the foundational challenge of data scarcity in biomedical imaging. The core of the discussion focuses on practical self-supervised and semi-supervised learning methodologies that leverage unlabeled image data to build robust foundational models. We then address common troubleshooting and optimization techniques to enhance model performance with limited annotations. Finally, the article provides a comparative analysis of these advanced methods against traditional supervised learning, validating their efficacy through performance metrics and real-world case studies in both intestinal and blood-borne parasite detection.

The Data Labeling Bottleneck: Challenges in Parasite Image Analysis for Biomedical Research

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is manual microscopy still considered the gold standard for parasite diagnosis? Manual microscopy is regarded as the gold standard because it is a well-established method that requires minimal, widely available equipment and reagents [1]. It can not only determine the presence of malaria parasites in a blood sample but also identify the specific species and quantify the level of parasitemia—all vital pieces of information for guiding treatment decisions [1]. For soil-transmitted helminths (STH), it is the common method for observing eggs and larvae in samples [2].

FAQ 2: What are the primary factors that limit the scalability of manual microscopy in large-scale studies? The primary limitations are its dependency on highly skilled technicians and the time-consuming nature of the analysis [3] [4]. The accuracy of the diagnosis is directly influenced by the microscopist's skill level [3]. Furthermore, manual analysis becomes impractical for processing large datasets or searching for rare cellular events [5], creating a significant bottleneck in large-scale research or surveillance efforts.

FAQ 3: How does the performance of manual microscopy compare to other diagnostic tests? When compared to molecular methods like PCR, manual microscopy can exhibit significantly lower sensitivity, especially in cases of low-intensity infections or asymptomatic carriers [3] [6]. One study in Angola found microscopy sensitivity for P. falciparum to be 60% compared to PCR, which was lower than the 72.8% sensitivity of a Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT) [6]. The following table summarizes a quantitative comparison from field studies:

Table: Performance Comparison of Malaria Diagnostic Methods Using PCR as Gold Standard

| Diagnostic Method | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Positive Predictive Value (PPV%) | Negative Predictive Value (NPV%) | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual Microscopy [6] | 60.0 | 92.5 | 60.0 | 92.5 | Sensitivity drops in low-parasite density and low-transmission areas [3] [6]. |

| Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT) [6] | 72.8 | 94.3 | 70.7 | 94.8 | May not detect infections with low parasite numbers; cannot quantify parasitemia [1]. |

| Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) | 100 (Gold Standard) | 100 (Gold Standard) | 100 (Gold Standard) | 100 (Gold Standard) | Expensive, time-consuming, requires specialized lab; not for acute diagnosis [1]. |

FAQ 4: Can automated image analysis match the accuracy of manual labels for training deep learning models? Yes, under specific conditions. Research indicates that deep learning models can achieve performance comparable to those trained with manual labels, even when using automatically generated labels, provided the percentage of incorrect labels (noise) is kept within a certain threshold (e.g., below 10%) [7]. This makes automatic labeling a viable strategy to alleviate the extensive need for expert manual annotation in large datasets [7].

FAQ 5: What are the common data quality challenges when developing AI models for parasite detection? Key challenges include imbalanced datasets, where uninfected cells vastly outnumber infected ones, leading to biased models; limited diversity in datasets from different geographic regions or using different staining protocols, which hinders model generalization; and annotation variability due to differences in expert opinion [8]. The table below outlines the impact of data imbalance and potential solutions:

Table: Impact of Data Imbalance on Deep Learning Model Performance for Malaria Detection

| Dataset and Training Condition | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) | Overall Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balanced Dataset [8] | 90.2 | 92.3 | 91.2 | 93.5 |

| Imbalanced Dataset [8] | 75.8 | 60.4 | 67.2 | 82.1 |

| Imbalanced Dataset + Data Augmentation [8] | 87.2 | 84.5 | 85.8 | 91.3 |

| Balanced Dataset + Transfer Learning [8] | 93.1 | 92.5 | 92.8 | 94.2 |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Sensitivity in Detecting Low-Intensity Parasite Infections

- Problem: Manual microscopy is failing to identify infections with low parasite density, a common issue in asymptomatic carriers or low transmission areas [3].

- Solution:

- Repeat Testing: For suspected malaria, if the initial blood smear is negative, repeat the test every 12–24 hours for a total of three sets before ruling out the diagnosis [1].

- Use Concentration Techniques: For STH, consider using concentration methods like the Formol-ether concentration (FEC) technique, which can improve sensitivity for some species like hookworms [2].

- Supplement with Molecular Methods: In a research context, use PCR as a more sensitive reference standard to confirm negative results and validate the performance of your microscopy [6].

Issue: Inconsistency and Subjectivity in Readings Between Different Technicians

- Problem: Results vary based on the expertise and subjective judgment of the individual microscopist [4].

- Solution:

- Standardized Training: Implement a rigorous and recurring training program for all technicians, following standard operational procedures like those from WHO [6].

- Implement a Double-Blind Reading Protocol: Have two independent technicians read each slide, with a third expert resolving any discrepancies [6].

- Regular Quality Control: Conduct random quality control checks on already-read slides by a senior microscopist to maintain high standards [6].

Issue: Scalability Bottleneck in Large-Scale Image Analysis for Research

- Problem: Manually analyzing thousands of images or continuous single-cell imaging data to track dynamic processes is too time-consuming [9].

- Solution: Implement an automated digital imaging workflow.

- Image Acquisition: Use microscopes with motorized stages and high-resolution cameras to automatically capture digital images of specimens [5] [9].

- AI-Based Image Analysis: Train or employ pre-trained deep learning algorithms (e.g., convolutional neural networks) to automatically segment cells and identify parasites within the digital images [4] [9].

- Experimental Protocol for Automated Single-Cell Analysis of P. falciparum [9]:

- Step 1: Acquire 3D Image Stacks. Use an Airyscan microscope to capture 3D z-stacks of single, live infected erythrocytes over time using both Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) and fluorescence modes.

- Step 2: Annotate a Training Dataset. Manually annotate a subset of images to delineate key structures (e.g., erythrocyte membrane, parasite compartment) using software like Ilastik or Imaris. This is a one-time, intensive effort.

- Step 3: Train a Neural Network. Use a cell segmentation model like Cellpose. Train it on your annotated dataset so it learns to automatically identify the structures of interest.

- Step 4: Deploy for Automated Analysis. Process the entire dataset with the trained Cellpose model to automatically segment every cell in every frame and time point.

- Step 5: 3D Rendering and Quantification. Use the output for 3D visualization and to extract quantitative, time-resolved data on the dynamic process being studied.

This workflow automates the analysis of large 4D (3D + time) datasets, enabling continuous single-cell monitoring that would be impossible manually [9].

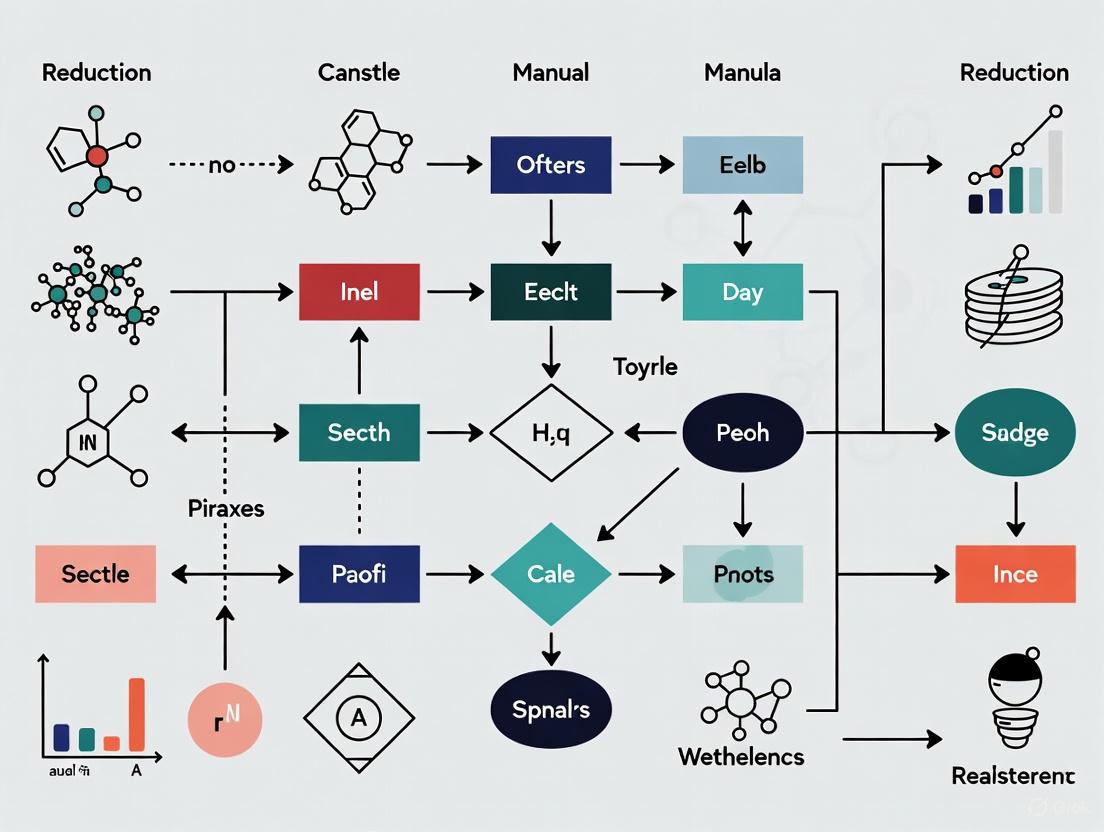

Diagram: Manual vs Automated Microscopy Workflows. The manual path highlights scalability bottlenecks that the automated path seeks to resolve.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Parasite Imaging and Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Examples / Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Giemsa Stain | Standard stain for blood smears to visualize malaria parasites and differentiate species [1] [6]. | 10% Giemsa solution for 15 minutes is a common protocol [6]. |

| Formol-Ether | A concentration technique for stool samples to improve the detection of Soil-Transmitted Helminth (STH) eggs [2]. | Helps in sedimenting eggs for easier microscopic identification [2]. |

| CellBrite Red | A fluorescent membrane dye. Used in research to stain the erythrocyte membrane, aiding in the annotation of cell boundaries for training AI models [9]. | |

| Airyscan Microscope | A type of high-resolution microscope that enables detailed 3D imaging with reduced light exposure, ideal for live-cell imaging of light-sensitive parasites like P. falciparum [9]. | |

| Cellpose | A deep learning-based, pre-trained convolutional neural network (CNN) for cell segmentation. Can be re-trained with minimal annotated data for specific tasks like segmenting infected erythrocytes [9]. | Supports both 2D and 3D image analysis [9]. |

| Ilastik / Imaris | Interactive machine learning and image analysis software packages. Used for annotating and segmenting images to create ground-truth datasets for training AI models [9]. | Ilastik offers a "carving workflow" for volume segmentation [9]. |

FAQs on Annotation Challenges and Solutions

What are the primary bottlenecks in creating pixel-perfect annotations for parasite datasets? The primary bottlenecks are the extensive human labor, time, and specialized expertise required. Manual microscopic examination, the traditional gold standard for parasite diagnosis, is inherently "labor-intensive, time-consuming, and susceptible to human error" [10] [11]. Creating precise annotations like pixel-level masks compounds this burden, as the process "relies on human annotators" and demands "skilled human annotators who understand annotation guidelines and objectives" [12].

Can automated labeling methods replace manual annotation without a significant performance drop? Yes, under specific conditions. Recent research into deep learning for histopathology images found that automatic labels can be as effective as manual labels, identifying a threshold of approximately 10% noisy labels before a significant performance drop occurs [13]. This indicates that an algorithm generating labels with at least 90% accuracy can be a viable alternative, effectively reducing the manual burden.

What annotation quality should I target for a parasite detection model? For high-stakes applications like medical diagnostics, the quality benchmarks are exceptionally high. State-of-the-art automated detection models, such as the YOLO Convolutional Block Attention Module (YCBAM) for pinworm eggs, demonstrate that targets of over 99% in precision and recall are achievable [10]. Your Quality Assurance (QA) processes should aim to match this rigor, employing "manual reviews, automated error checks, and expert validation" [12].

Which annotation techniques are best for capturing detailed parasite morphology? The choice of technique depends on the specific diagnostic task:

- Pixel-Level Annotation / Semantic Segmentation: This is ideal for capturing fine-grained morphology. It "targets identifying specific areas" and "produces a detailed mask or silhouette that outlines an object from its background," providing "pixel-level exactness" [12]. This is confirmed in parasite research, where U-Net and ResU-Net models achieved high dice scores for segmenting pinworm eggs [10].

- Polygons: Offer a strong balance between precision and efficiency. They "outline objects using varied vertices instead of four corners," enabling a "more accurate representation of complex shapes" than bounding boxes [12].

- Instance Segmentation: Crucial for multi-parasite analysis. It "involves assigning a unique label to each individual occurrence of an object," allowing the model to differentiate between separate instances of the same parasite type [12].

How can I improve my model's performance without solely relying on more manual annotations? Integrating advanced preprocessing and model architectures can significantly boost performance. For example, one study on malaria detection showed that applying Otsu thresholding-based image segmentation as a preprocessing step improved a CNN's classification accuracy from 95% to 97.96% [11]. This emphasizes parasite-relevant regions and reduces background noise, making the model more robust from the same amount of annotated data.

Quantitative Data on Annotation and Model Performance

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Deep Learning Models in Parasitology

| Parasite / Disease | Model Architecture | Key Performance Metrics | Annotation Type & Dataset Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pinworm Parasite [10] | YOLO-CBAM (YCBAM) | Precision: 0.9971, Recall: 0.9934, mAP@0.5: 0.9950 | Object Detection (Bounding Boxes) |

| Malaria Parasite [11] | CNN with Otsu Segmentation | Accuracy: 97.96% (vs. 95% without segmentation) | Image Classification; 43,400 images |

| Malaria Parasite [14] | Hybrid Capsule Network (Hybrid CapNet) | Accuracy: Up to 100% (multiclass), Parameters: 1.35M (lightweight) | Multiclass Classification; Four benchmark datasets |

| Digital Pathology [13] | Multiple (CNNs, Transformers) | Automatic labels effective within ~10% noise threshold | Weak Labels; 10,604 Whole Slide Images |

Table 2: Image Annotation Techniques and Their Applications in Parasitology

| Annotation Technique | Description | Common Use-Case in Parasitology | Relative Workload |

|---|---|---|---|

| Image Classification [12] | Single label for entire image (e.g., "infected" vs. "uninfected"). | Initial screening and binary classification. | Low |

| Object Detection [12] | Locates objects using bounding boxes and class labels. | Counting and locating parasite eggs in a sample. | Medium |

| Semantic Segmentation [12] | Classifies every pixel of an object, but doesn't distinguish instances. | Analyzing infected regions within a single host cell. | High |

| Instance Segmentation [12] | Classifies every pixel and distinguishes between individual objects. | Differentiating between multiple parasites of the same type in one image. | Very High |

| Panoptic Segmentation [12] | Unifies instance (e.g., parasites) and semantic segmentation (e.g., background). | Holistic scene understanding of a complex sample. | Highest |

Experimental Protocols for Reducing Annotation Burden

Protocol 1: Implementing a Hybrid Annotation Workflow with AI Pre-labeling

This protocol leverages AI to automate the initial annotation, which human experts then refine, significantly speeding up the process while maintaining high quality.

- Tool Selection: Choose a platform that supports AI-assisted labeling and complex ontologies, such as Encord or Supervisely, which offer features like "SOTA automated labeling" and "AI-based labeling" [15].

- Model Integration: Integrate a pre-trained model (e.g., a CNN or YOLO-based detector) into your annotation pipeline to perform initial "pre-labeling" on your raw parasite image dataset [15].

- Human-in-the-Loop Refinement: Annotators focus their effort on correcting the AI-generated labels rather than starting from scratch. This step should include a "multi-step review stages and consensus benchmarking for quality assurance" [15].

- Quality Control: Use the platform's QA tools to "automatically surface labeling errors" and ensure the final dataset meets the required precision standard (e.g., >99%) [15].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Automated Labels Against a Noisy Label Threshold

This methodology assesses whether an automated labeling system is reliable enough to be used for training, based on the 10% noise threshold identified in recent research [13].

- Create a Gold Standard Benchmark: Manually annotate a small, high-quality subset of your dataset (e.g., 100-200 images) with pixel-perfect accuracy. This is your ground truth.

- Generate Automatic Labels: Run your automatic labeling algorithm on the benchmark subset.

- Quantify Label Noise: Compare the automatic labels to the gold standard. Calculate the percentage of images or objects where the automatic label is incorrect or noisy.

- Performance Validation: If the measured noise is below 10%, you can proceed to train your model with the automatic labels. The model's performance should then be validated on a separate, manually annotated test set to confirm it reaches the required F1-scores or accuracy [13].

Protocol 3: Preprocessing with Otsu Segmentation for Enhanced Model Performance

This protocol uses a classic image segmentation technique to improve model performance, reducing the need for extremely large annotated datasets [11].

- Image Acquisition: Collect your dataset of blood smear or parasite images.

- Apply Otsu's Thresholding: For each image, apply Otsu's method for global image thresholding. This algorithm automatically calculates the optimal threshold value to separate the foreground (potential parasites and cells) from the background.

- Create Segmentation Mask: The output is a binary mask that highlights the parasite-relevant regions. Studies validating this step achieved a "mean Dice coefficient of 0.848 and Jaccard Index (IoU) of 0.738" against manual masks [11].

- Train Model on Processed Data: Use the segmented images (or the original images with the masks applied) to train your deep learning classification model (e.g., a CNN). Research shows this can lead to a significant gain in accuracy [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Reagents for Automated Parasite Image Analysis

| Item / Tool Name | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Otsu Thresholding Algorithm [11] | A preprocessing method to segment and isolate parasitic regions from the image background, boosting subsequent model accuracy. |

| YOLO-CBAM Architecture [10] | An object detection framework combining YOLO's speed with attention mechanisms (CBAM) for highly precise parasite localization in complex images. |

| Hybrid CapNet [14] | A lightweight neural network architecture designed for precise parasite identification and life-cycle stage classification with minimal computational cost. |

| AI-Assisted Annotation Platforms [15] | Software (e.g., Encord, Labelbox) that uses models to pre-label data, drastically reducing the manual effort required for annotation. |

| Segment Anything Model (SAM) [15] | A foundation model for image segmentation that can be integrated into annotation tools to automate the creation of pixel-level masks. |

Workflow Visualization

AI-Human Hybrid Annotation and Preprocessing Workflow

Noisy Label Threshold Validation Protocol

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Insufficient or Low-Quality Training Data

Problem: Model performance is poor, with low accuracy and generalization, due to a lack of sufficient, high-quality labeled data for training.

Solution: Implement a confidence-based pipeline to maximize the utility of limited data and identify the most valuable samples for manual review.

- Step 1: Train Initial Model - Begin by training your initial deep learning classifier (e.g., a Convolutional Neural Network) on your available, often limited, labeled dataset [16].

- Step 2: Generate Predictions and Confidence Scores - Use the trained model to generate predictions (class labels) and, crucially, the associated confidence scores for the unlabeled data. The confidence score is typically the probability output from the model's final softmax layer [16].

- Step 3: Set a Confidence Threshold - Determine an acceptable confidence threshold based on your project's accuracy requirements. This threshold defines how certain the model must be before its automated label is accepted [16].

- Step 4: Automatically Accept/Reject Labels - Automatically accept all model-generated labels that have a confidence score at or above your chosen threshold. Reject and flag all predictions below the threshold for manual expert review [16].

- Step 5: Iterate and Retrain - Incorporate the newly accepted high-confidence labels into your training set. The manually reviewed labels can also be added. Retrain your model on this expanded dataset for improved performance.

The table below outlines the expected trade-off between accuracy and data coverage when using this method, based on a model with an initial 86% accuracy [16].

Table 1: Accuracy vs. Coverage Trade-off with Confidence Thresholding

| Confidence Threshold | Resulting Accuracy | Data Coverage | Use Case Suggestion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | ~86% (Baseline) | ~100% | Initial data exploration and filtering |

| Medium | >95% | ~60% | General research and analysis |

| High | >99% | ~35% | Accuracy-critical applications and final validation |

Guide 2: Managing Computational Costs for Resource-Intensive Models

Problem: Complex AI models are too slow or computationally expensive to run, making them unsuitable for deployment in field clinics or resource-limited labs.

Solution: Adopt lightweight neural network architectures designed for efficiency without a significant sacrifice in accuracy.

- Step 1: Benchmark Model Efficiency - Before selecting a new architecture, establish baseline metrics for your current model. Key metrics include the number of parameters (in millions) and computational cost in Giga Floating Point Operations (GFLOPs) [14].

- Step 2: Select a Lightweight Architecture - Choose a model architecture designed for efficiency. For example, the Hybrid Capsule Network (Hybrid CapNet) has been successfully used for malaria parasite classification with only 1.35 million parameters and 0.26 GFLOPs [14].

- Step 3: Optimize Input Data - Preprocess your images to a resolution that balances detail and computational load. The Tryp dataset, for instance, used frames extracted from microscopy videos [17].

- Step 4: Validate Performance - Rigorously test the new, lighter model on your validation and test sets to ensure diagnostic accuracy has been maintained. Cross-dataset validation is recommended to check generalizability [14].

Table 2: Computational Efficiency Comparison for Diagnostic Models

| Model / Architecture | Parameters (Millions) | Computational Cost (GFLOPs) | Reported Accuracy | Suitable for Mobile Deployment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid CapNet (for malaria) [14] | 1.35 | 0.26 | Up to 100% (multiclass) | Yes |

| Typical CNN Models (Baseline) [14] | >10 | >1.0 | Varies | Often No |

Guide 3: Mitigating Dataset Bias and Ensuring Generalizability

Problem: A model performs excellently on its original dataset but fails when presented with images from a different microscope, staining protocol, or patient population.

Solution: Proactively build diversity into your dataset and apply rigorous cross-dataset validation.

- Step 1: Source Data from Multiple Sources - Actively collect images from different types of microscopes (e.g., Olympus IX83, CKX53 [17]), using various staining protocols (including unstained samples [17]), and from diverse geographic locations.

- Step 2: Implement Cross-Dataset Validation - During testing, evaluate your model's performance not just on a held-out test set from the same source, but on a completely separate dataset. This is the most reliable way to measure true generalizability [14].

- Step 3: Use Data Augmentation - During training, artificially increase the diversity of your dataset using techniques like rotation, flipping, and color jittering to simulate different conditions.

- Step 4: Analyze Failure Cases - When the model performs poorly on a new dataset, use interpretability tools like Grad-CAM to visualize which image regions led to the decision. This can help identify the specific bias (e.g., over-reliance on a particular staining artifact) [14].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Can I truly trust labels that are generated automatically, or must all training data be manually verified by an expert?

With the correct safeguards, automatically generated labels can be highly reliable. Research shows that if the automatic labeling process produces less than 10% noisy labels, the performance drop-off of the subsequent AI model is minimal [13]. By implementing a confidence-thresholding method, you can selectively use automated labels with a known, high accuracy (e.g., over 95% or 99%), while sending only the lower-confidence predictions for manual review. This creates a highly efficient human-in-the-loop pipeline [16].

FAQ 2: What are the most critical factors to ensure the success of an automated labeling project for parasite images?

Three factors are paramount:

- Initial Expert-Labeled Seed Data: A core set of high-quality, expert-labeled images is non-negotiable to train the initial model [18].

- Confidence Calibration: The model must output confidence scores that accurately reflect the true probability of a prediction being correct. Without this, thresholding is ineffective [16].

- Domain Expertise in the Loop: The process cannot be fully automated. Experts are essential for setting initial labels, reviewing edge cases, and validating results [18] [17].

FAQ 3: Our research lab has limited funding for computational resources. How can we develop effective AI models?

Focus on lightweight model architectures from the start. Models like the Hybrid Capsule Network are specifically designed to deliver high accuracy with a low computational footprint (e.g., 1.35M parameters, 0.26 GFLOPs), making them suitable for deployment on standard laptops or even mobile devices, which drastically reduces costs [14].

FAQ 4: How can we handle patient privacy (HIPAA) when collecting and annotating medical images for AI?

When dealing with medical images, it is critical to work with annotation platforms and protocols that are fully HIPAA compliant. This involves de-identifying all patient data, using secure and encrypted data transfer methods, and ensuring that all annotators are trained in and adhere to data privacy regulations [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Parasite Image AI Research

| Item / Tool Name | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Olympus Microscopes (e.g., IX83, CKX53) [17] | High-quality image acquisition for creating new datasets. | Built-in vs. mobile phone attachment capabilities can affect data uniformity. |

| Roboflow & Labelme [17] | Platforms for drawing and managing bounding box annotations on images. | Supports export to standard formats (e.g., COCO) needed for model training. |

| Hybrid CapNet Architecture [14] | A lightweight deep learning model for image classification. | Ideal for resource-constrained settings due to low computational demands. |

| DICOM Viewers & Annotation Tools [18] | Specialized software for handling and annotating medical imaging formats. | Essential for working with standard clinical data like MRIs and CTs. |

| Confidence-Thresholding Pipeline [16] | A methodological framework for improving automated label accuracy. | Allows trading data coverage for higher label accuracy based on project needs. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common causes of mislabeling in automated blood smear analysis? Automated digital morphology analyzers can mislabel cells due to several factors. A primary challenge is the difficulty in recognizing rare and dysplastic cells, as the performance of AI algorithms for these cell types is variable [19]. Furthermore, the quality of the blood film and staining techniques significantly influences accuracy; poor-quality samples, including those with traumatic morphological changes from automated slide makers, can lead to errors [19]. Finally, elements like degenerating platelets can be misidentified as parasites, such as trypomastigotes of Trypanosoma spp., while nucleated red blood cells may be confused for malaria schizonts [20].

FAQ 2: Why might multiple stool samples be necessary for accurate parasite detection? Collecting multiple stool samples is crucial because the diagnostic yield increases with each additional specimen. A 2025 study found that while many parasites were detected in the first sample, the cumulative detection rate rose with the second and third specimens, reaching 100% in the studied cohort [21]. Some parasites, like Trichuris trichiura and Isospora belli, are frequently missed if only one specimen is examined [21]. This intermittent excretion of parasitic elements means a single sample provides only a snapshot, potentially leading to false negatives in labeling datasets.

FAQ 3: What non-parasitic objects are commonly mistaken for parasites in stool samples? Stool samples often contain various artifacts that can be mistaken for parasites, including [20]:

- Yeast and fungal spores, which can be confused for Giardia cysts or helminth eggs.

- Pollen grains, which can closely resemble the fertile eggs of Ascaris lumbricoides or operculated trematode eggs.

- Plant hairs and plant material, which may be misidentified as helminth larvae, such as Strongyloides stercoralis.

- Charcot-Leyden crystals, which are breakdown products of eosinophils and indicate an immune response but are not parasites themselves.

FAQ 4: How can staining and preparation issues lead to false results in ELISA? Conventional ELISA buffers can cause intense false-positive and false-negative reactions due to the hydrophobic binding of immunoglobulins in samples to plastic surfaces, a phenomenon known as "background (BG) noise reaction" [22]. These non-specific reactions can be mitigated by using specialized buffers designed to reduce such interference without affecting the specific antigen-antibody reaction. It is also critical to include antigen non-coated blank wells to determine the individual BG noise for each sample [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Challenge 1: Inconsistent Cell Pre-classification in Digital Blood Smear Analysis

- Problem: A digital morphology analyzer provides inconsistent pre-classification of white blood cells (WBCs), especially in samples with abnormal morphology.

- Solution:

- Verify Sample Quality: Ensure the blood film has a clear feather edge and is free of artifacts caused by improper spreading. Automated slide makers can sometimes introduce traumatic morphological changes [19].

- Check Staining Protocol: DM analyzers are designed for specific staining protocols. Confirm that your laboratory's staining method (e.g., Romanowsky, RAL) is compatible and consistent. Adhere strictly to the recommended staining times [19].

- Implement Expert Review: For complex cases with atypical or rare cells, an expert's manual review remains essential. The DM analyzer should be used as a pre-classifier, with a skilled operator making the final verification [19].

Challenge 2: Low Detection Rate of Parasites in Stool Sample Analysis

- Problem: A study finds that a single stool examination fails to detect a target parasite in a significant number of known positive cases.

- Solution:

- Adopt a Multi-Sample Protocol: Implement a standard operating procedure of collecting three stool specimens over consecutive days [21].

- Understand Parasite-Specific Yield: Be aware that the required number of samples can vary by parasite. For example, detecting Strongyloides stercoralis may require examination of up to seven samples for high sensitivity [21].

- Consider Patient Factors: The diagnostic yield of additional samples is significantly higher in immunocompetent hosts compared to immunocompromised individuals [21].

Challenge 3: High Rate of False Positives from Artifacts in Stool Microscopy

- Problem: During manual review or algorithm training, numerous objects are incorrectly labeled as parasitic elements.

- Solution:

- Use a Reference Guide: Consult artifact identification resources, such as the CDC DPDx artifact gallery, to familiarize yourself and your team with common mimics [20].

- Key Identification Features:

- Plant Hairs: Often broken at one end and lack the internal structures (e.g., esophagus, genital primordium) seen in true helminth larvae [20].

- Pollen Grains: May have spine-like structures on the outer layer or lack the refractile hooks found in some helminth eggs [20].

- Yeast in Acid-Fast Stains: Can be confused for Cryptosporidium oocysts; careful observation of size and internal morphology is needed [20].

Structured Data for Experimental Design

Table 1: Diagnostic Yield of Consecutive Stool Specimens for Pathogenic Intestinal Parasites (n=103) [21]

| Number of Specimens | Cumulative Detection Rate (%) |

|---|---|

| First Specimen | 61.2% |

| First and Second | 85.4% |

| First, Second, Third | 100.0% |

Table 2: Common Artifacts and Their Parasitic Mimics in Microscopy [20]

| Artifact Category | Example Artifact | Common Parasitic Mimic(s) | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fungal Elements | Yeast | Giardia cysts, Cryptosporidium oocysts | Size, shape, and internal structure; yeast in acid-fast stains may not have the correct morphology |

| Plant Material | Pollen grains | Ascaris lumbricoides eggs, Clonorchis eggs | Presence of spine-like structures on pollen; size is often smaller than trematode eggs |

| Plant hairs | Larvae of hookworm, Strongyloides stercoralis | Broken ends, refractile center, lack of defined internal structures (esophagus, genital primordium) | |

| Blood Components | Degenerating platelets | Trypanosoma spp. trypomastigotes | Context (blood smear); lacks a distinct nucleus and kinetoplast |

| Nucleated red blood cells | Plasmodium spp. schizonts | Cellular morphology and staining properties | |

| Crystals | Charcot-Leyden crystals | N/A (but may indicate parasitic infection) | Characteristic bipyramidal, hexagonal shape; product of eosinophil breakdown |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standardized Method for Multi-Sample Stool Microscopy

This protocol is designed to maximize parasite detection rates for a diagnostic study [21].

- Sample Collection: Instruct patients to submit three separate stool specimens. All specimens should be collected within a 7-day window from the first sample.

- Preservation and Transport: Use appropriate preservatives (e.g., formalin) for fixed samples or ensure fresh samples are processed promptly.

- Microscopic Examination:

- Prepare each specimen using a combination of Kato’s thick smear and direct smear techniques (or formalin-ethyl acetate concentration, FECT) [21].

- Systematically examine each smear under the microscope.

- Data Recording: Record the findings for each specimen separately. Note if a parasite is detected for the first time in the second or third specimen.

- Analysis: Calculate the diagnostic yield for the first specimen alone, then for the first and second combined, and finally for all three.

Protocol 2: Workflow for Validating an Automated Blood Smear Analyzer

This protocol outlines key steps for verifying the performance of a digital morphology analyzer, such as a CellaVision or Sysmex DI-60 system, in a research setting [19].

- Sample Set Selection: Curate a set of blood smears that includes a range of normal and abnormal findings, with an emphasis on rare cells and dysplastic cells that are known to be challenging for automated systems.

- Reference Standard Establishment: Have all slides in the set classified by multiple expert hematologists to establish a "gold standard" label for each cell.

- Blinded Analysis: Run the curated sample set through the DM analyzer, ensuring the system's pre-classifications are recorded without operator influence.

- Discrepancy Review: Compare the analyzer's pre-classifications against the expert consensus. All discrepancies must be reviewed by an expert to determine the correct label.

- Performance Assessment: Calculate accuracy, precision, and reproducibility metrics for the analyzer, paying special attention to its performance on the previously identified challenging cell types.

Analysis Workflow Diagram

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Context |

|---|---|

| Romanowsky Stains (e.g., May-Grünwald Giemsa, Wright-Giemsa) | Standard staining for peripheral blood smears; allows for differentiation of white blood cells and morphological assessment of red blood cells and platelets. Essential for digital morphology analyzers [19]. |

| Formalin-Ethyl Acetate | Used in the formalin-ethyl acetate concentration technique (FECT) for stool samples to concentrate parasitic elements for easier microscopic detection [21]. |

| ChonBlock Buffer | A specialized ELISA buffer designed to reduce intense false-positive and false-negative reactions caused by non-specific hydrophobic binding of immunoglobulins to plastic surfaces, thereby improving assay accuracy [22]. |

| Acid-Fast Stains | Staining technique used to identify certain parasites, such as Cryptosporidium spp. and Cyclospora spp., in stool specimens. Requires careful interpretation to distinguish from yeast and fungal artifacts [20]. |

| Trichrome Stain | A stain used for permanent staining of stool smears to visualize protozoan cysts and trophozoites. White blood cells and epithelial cells in the stain can be mistaken for amebae [20]. |

| Alum Hematoxylin (e.g., Harris, Gill's) | A core component of H&E staining; used as a nuclear stain in histology. The type of hematoxylin (progressive vs. regressive) and differentiation protocol can be customized for optimal contrast [23]. |

| Eosin Y | The most common cytoplasmic counterstain in H&E staining, typically producing pink shades that distinguish cytoplasm and connective tissue fibers from cell nuclei [23]. |

Practical Self-Supervised and Semi-Supervised Learning Methods for Parasitology

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

This technical support center provides practical guidance for researchers applying Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) to medical imaging, with a specific focus on parasite image analysis. The content is designed to help you overcome common technical challenges and implement experiments that reduce reliance on manually labeled datasets.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of SSL models like DINOv2 over traditional supervised learning for our parasite image dataset? SSL models are pre-trained on large amounts of unlabeled images, learning general visual features without the cost and time of manual annotation. This is particularly beneficial for parasite image analysis, where expert labeling is a significant bottleneck. Models like DINOv2 can then be fine-tuned for specific tasks (e.g., identifying parasite species) with very few labeled examples, achieving high performance [24] [25].

Q2: My SSL training is unstable and results in collapsed representations (all outputs are the same). How can I prevent this? Representation collapse is a common challenge. You can address it by:

- Using Simplified Frameworks: Newer frameworks like SimDINO incorporate a coding rate regularization term into the loss function, which directly prevents collapse and makes training more stable and robust without needing complex hyperparameter tuning [26].

- Leveraging Built-in Mechanisms: If using models like SimSiam, ensure you are using the stop-gradient operation and a prediction MLP head, which are essential for preventing collapse [27].

Q3: When should I choose a self-supervised model like SimSiam over a supervised one for my project? The choice depends on your dataset size and label availability. Recent research on medical imaging tasks suggests that for small training sets (e.g., under 1,000 images), supervised learning (SL) may still outperform SSL, even when only a limited portion of the data is labeled [28]. SSL begins to show its strength as the amount of available unlabeled data increases.

Q4: We have a high-class imbalance in our parasite data (some species are very rare). Will SSL still work? Class imbalance can challenge SSL methods. However, studies indicate that some SSL paradigms, like MoCo v2 and SimSiam, can be more robust to class imbalance than supervised learning representations [28]. The performance gap between models trained on balanced versus imbalanced data is often smaller for SSL than for SL.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Transfer Learning Performance After SSL Pre-training

- Problem: After pre-training an SSL model on your unlabeled parasite images, fine-tuning it on a labeled task yields low accuracy.

- Solution:

- Verify Data Alignment: Ensure the domain of your pre-training data (e.g., general parasite images) is relevant to your downstream task (e.g., specific species identification). Domain mismatch is a common cause of poor transfer [28].

- Inspect Data Quality: Check your unlabeled dataset for extreme class imbalance or a large number of corrupted, non-informative images. Applying a data curation pipeline, as used in DINOv2 training, can help [26].

- Adjust Fine-tuning: Use a lower learning rate for the pre-trained backbone and a higher rate for the new classification head during fine-tuning. This protects the learned features while adapting to the new task.

Issue: Long Training Times or Memory Errors

- Problem: Training an SSL model is computationally expensive and crashes due to insufficient GPU memory.

- Solution:

- Reduce Batch Size: Start with a smaller batch size. Note that SimSiam is known to perform robustly across a wide range of batch sizes, making it a good choice if large batches are not feasible [27].

- Use Smaller Models or Checkpoints: Begin experimentation with smaller model variants (e.g., DINOv2-small or ViT-Small) instead of the large versions. You can also use models pre-trained on large public datasets [24] [25].

- Gradient Accumulation: Simulate a larger batch size by accumulating gradients over several forward/backward passes before updating model weights.

Experimental Protocols & Performance Data

Methodology: Fine-tuning DINOv2 for Intestinal Parasite Identification This protocol is based on a published study that achieved high accuracy in identifying intestinal parasites from stool samples [24].

Data Preparation:

- Microscopy Images: Collect stool sample images prepared using techniques like formalin-ethyl acetate centrifugation (FECT) or Merthiolate-iodine-formalin (MIF).

- Train/Test Split: Split the labeled dataset, for example, using 80% for training and 20% for testing.

- Preprocessing: Resize images to the input size expected by the model (e.g., 224x224 for standard ViTs).

Model Setup:

- Backbone: Load a pre-trained DINOv2 model (e.g.,

facebook/dinov2-baseorfacebook/dinov2-large) using the Hugging Facetransformerslibrary [25]. - Classifier: Replace the default head with a new linear classification layer that has output nodes equal to the number of parasite species in your dataset.

- Backbone: Load a pre-trained DINOv2 model (e.g.,

Training (Fine-tuning):

- Loss Function: Use Cross-Entropy Loss.

- Optimizer: Use Adam or SGD with momentum.

- Training Loop: Fine-tune the entire model (backbone and classifier) on your labeled training set.

The following performance data from the study illustrates the potential of this approach [24]:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Deep Learning Models on Intestinal Parasite Identification

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Sensitivity | Specificity | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DINOv2-large | 98.93% | 84.52% | 78.00% | 99.57% | 81.13% |

| YOLOv8-m | 97.59% | 62.02% | 46.78% | 99.13% | 53.33% |

| YOLOv4-tiny | Information missing | 96.25% | 95.08% | Information missing | Information missing |

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) Paradigms

| SSL Model | Key Principle | Advantages | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SimSiam [27] | Simple Siamese network without negative pairs. | No need for negative samples, large batches, or momentum encoders. Robust across batch sizes. | Requires stop-gradient operation to prevent collapse. |

| DINOv2 [26] | Self-distillation with noise-resistant objectives. | Produces strong, general-purpose features; suitable for tasks like segmentation and classification. | Training can be complex; using simplified versions like SimDINO is recommended. |

| VICReg [26] | Regularizes variance and covariance of embeddings. | Prevents collapse by decorrelating features. | May not address feature variance as effectively as other methods. |

Workflow Diagram: SSL for Parasite Image Analysis

Architecture Diagram: SimSiam Simplified

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Resources for SSL Experiments in Parasitology

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Microscopy Images | The core unlabeled data. Images of stool samples, nematodes (e.g., C. elegans), or other parasites used for SSL pre-training and evaluation [24] [29]. |

| Pre-trained SSL Models (DINOv2, SimSiam) | Foundational models that provide a strong starting point. They can be fine-tuned on a specific parasite dataset, saving computation time and data [24] [25]. |

| Data Augmentation Pipeline | Generates different "views" of the same image (via cropping, color jittering, etc.), which is crucial for SSL methods like SimSiam and DINOv2 to learn meaningful representations [27]. |

| GPU Accelerator | Hardware essential for training deep learning models in a reasonable time frame due to the high computational load of processing images and calculating gradients [25]. |

| Formalin-Ethyl Acetate Centrifugation (FECT) | A routine diagnostic procedure for stool samples. Used to prepare high-quality, concentrated microscopy images that serve as a reliable ground truth for evaluation [24]. |

Welcome to the SSL Technical Support Center

This resource is designed for researchers and scientists developing automated diagnostic tools for parasite image analysis. Here, you will find solutions to common technical challenges encountered when implementing Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) pipelines to reduce dependency on manually labeled data.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Can SSL genuinely reduce the need for manual labeling in our parasite image analysis? Yes. SSL allows a model to learn powerful feature representations from unlabeled images through pre-training. This model can then be fine-tuned for a specific downstream task, like parasite classification, using a very small fraction of labeled data. For instance, one study on zoonotic blood parasites achieved 95% accuracy and a 0.960 Area Under the Curve (AUC) by fine-tuning an SSL model with just 1% of the available labeled data [30].

Q2: What is a simple yet effective SSL method to start with for image data? A straightforward and powerful approach is contrastive learning, exemplified by frameworks like SimCLR [31]. In this method, the model is presented with two randomly augmented versions of the same image and is trained to recognize that they are "similar," while treating augmented versions of other images as "dissimilar." This forces the model to learn meaningful, invariant features without any labels [32] [31].

Q3: Our model performs well pre-training but poorly after fine-tuning on our small labeled parasite set. What could be wrong? This is often a sign of catastrophic forgetting or an improperly tuned fine-tuning stage. To mitigate this:

- Freeze early layers: During initial fine-tuning, keep the weights of your pre-trained feature backbone (the early layers) frozen. Only update the weights of the final classification layer [32].

- Use a lower learning rate: The fine-tuning phase typically requires a much lower learning rate than pre-training to make subtle weight adjustments without overwriting previously learned knowledge [33] [34].

- Incorporate regularization: Techniques like learning rate warm-up can help maintain stability during fine-tuning [33].

Q4: How do we create "labels" from unlabeled data during the pre-training phase? SSL uses pretext tasks that generate pseudo-labels automatically from the data's structure. Common tasks for images include:

- Rotation Prediction: Randomly rotate images (e.g., 0°, 90°, 180°, 270°) and train the model to predict the rotation angle [32].

- Colorization: Train the model to predict the color version of a grayscale input image [31].

- In-painting: Mask parts of an image and train the model to reconstruct the missing content [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Feature Representation After Pre-training Your model fails to learn meaningful features, leading to low performance on the downstream task.

- Potential Cause 1: The pretext task is not relevant to your domain.

- Solution: Choose a pretext task that encourages the model to learn features relevant to medical imaging. For instance, in-painting or contrastive learning have been shown to help models capture important visual features for polyp classification in colon cancer imagery [31].

- Potential Cause 2: Insufficient or inadequate data augmentation.

- Solution: Contrastive learning frameworks like SimCLR rely heavily on strong data augmentation. Ensure your augmentation pipeline includes a robust combination of techniques like random cropping, color distortion, and Gaussian blur [31].

Problem: Fine-tuned Model Fails to Generalize to Novel Parasite Classes The model performs well on classes seen during meta-training but poorly on unseen species during testing.

- Potential Cause: The feature backbone is not class-agnostic enough.

- Solution: Introduce a meta-training step between pre-training and fine-tuning. This involves using a simple algorithm like ProtoNet on a set of "base" classes to teach the model how to quickly adapt to new classification tasks. Research shows that combining self-supervised pre-training with meta-training significantly improves performance on novel classes [34].

Quantitative Performance Data

The following table summarizes key results from a study that applied SSL to classify various zoonotic blood parasites from microscopic images, demonstrating its effectiveness with limited labels [30].

Table 1: Performance of a BYOL SSL model (with ResNet50 backbone) for parasite classification.

| Metric | Performance with 1% Labeled Data | Performance with 20% Labeled Data |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 95% | ≥95% |

| AUC | 0.960 | Not Specified |

| Precision | Not Specified | ≥95% |

| Recall | Not Specified | ≥95% |

| F1 Score | Not Specified | ≥95% |

Table 2: F1 Scores for multi-class classification of specific parasites using the SSL model.

| Parasite Species | F1 Score |

|---|---|

| Babesia | >91% |

| Leishmania | >91% |

| Plasmodium | >91% |

| Toxoplasma | >91% |

| Trypanosoma evansi (early stage) | 87% |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: SSL for Blood Parasite Identification [30]

This protocol outlines the successful SSL approach from the research cited in the tables above.

Dataset:

- Public dataset of Giemsa-stained thin blood film images.

- Parasite classes: Trypanosoma, Babesia, Leishmania, Plasmodium, Toxoplasma, and Trichomonad, alongside white and red blood cells.

SSL Pre-training:

- Model: Bootstrap Your Own Latent (BYOL) algorithm.

- Backbone: ResNet50, ResNet101, and ResNet152 were evaluated.

- Input: Unlabeled microscopic images.

- Process: The model learns by comparing two augmented views of the same image through an online and a target network, without using negative pairs.

Downstream Fine-tuning:

- Process: The pre-trained model is adapted for the specific task of parasite classification.

- Data Regime: As little as 1% of the labeled data was used for fine-tuning to evaluate performance with extreme data scarcity.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational tools for implementing an SSL pipeline.

| Item / Tool | Function in the SSL Pipeline |

|---|---|

| BYOL (Bootstrap Your Own Latent) | An SSL algorithm that learns by comparing two augmented views of an image without needing negative examples, effective for medical images [30]. |

| ResNet (e.g., ResNet50) | A robust convolutional neural network architecture often used as the feature extraction backbone (encoder) in SSL models [30]. |

| Giemsa-stained Image Dataset | The raw, unlabeled input data. For parasite research, this consists of high-quality microscopic images of blood smears [30]. |

| ProtoNet Classifier | A simple yet effective meta-learning algorithm used for few-shot classification. It classifies images based on their distance to prototype representations of each class [34]. |

| Vision Transformer (ViT) | A transformer-based architecture for images. When pre-trained with SSL (e.g., DINO), it can learn powerful class-agnostic features for novel object detection [34]. |

SSL Workflow Diagrams

SSL Pipeline for Parasite Image Analysis

BYOL Self-Supervised Learning Architecture

This technical support document outlines a self-supervised learning (SSL) strategy that achieves high accuracy in classifying multiple blood parasites from microscopy images using approximately 100 labeled images per class [35]. This approach directly addresses the critical bottleneck of manual annotation in medical AI, a key focus of thesis research on reducing labeling efforts. The method uses a large unlabeled dataset to learn general visual representations, which are then fine-tuned for a specific classification task with a minimal set of labels.

➤ Experimental Workflow and Protocol

The following diagram illustrates the three-stage pipeline for self-supervised learning and classification.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

1. Data Collection and Preprocessing [35]

- Image Acquisition: Collect blood sample images from multiple sites using a standardized method (e.g., a smartphone attached to a conventional microscope). Include images at different magnifications (e.g., 10×, 40×, 100×).

- Image Curation: Divide each high-resolution Field-of-View (FoV) image into a 3x3 grid to create smaller patches (e.g., 300x300 pixels). This increases dataset size and granularity.

- Data Segregation: Strictly separate the entire dataset into:

- A large pool of unlabeled images (e.g., ~89,600 patches) for self-supervised pre-training.

- A smaller, expertly labeled set (e.g., ~15,268 patches across 11 parasite classes) for the final classification task. Ensure no overlap between these sets.

2. Self-Supervised Pre-training with SimSiam [35]

- Objective: Train a model to learn meaningful image representations without manual labels.

- Network Architecture: Use a ResNet50 as the backbone encoder. Add a 3-layer Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) projector and a 2-layer MLP predictor.

- Algorithm:

- Input: Take an unlabeled image (

x). - Augmentation: Generate two randomly augmented views of the image (

x1,x2). Use transformations like random cropping, color jittering, and random flipping. - Processing: Pass both views through the encoder and projector to get embeddings (

z1,z2). - Prediction: Pass one embedding through the predictor to get

p1. - Loss Calculation: Maximize the similarity between

p1andz2using a negative cosine similarity loss, while using a "stop-gradient" operation onz2to prevent model collapse. Repeat symmetrically for the other view.

- Input: Take an unlabeled image (

- Training: Initialize with ImageNet weights. Train for 25 epochs using SGD optimizer with momentum and cosine decayed learning rate.

3. Supervised Fine-tuning for Classification [35]

- Transfer Weights: Initialize a new classification model with the weights from the pre-trained encoder.

- Training Strategies:

- Linear Probe: Freeze the weights of the initial layers, only training the last convolutional layers and the new classification head.

- Full Fine-tuning: Allow all weights in the network to be updated during training.

- Handling Data Imbalance: Apply a weighted loss function based on class distribution to avoid overfitting to majority classes.

- Incremental Evaluation: Systematically evaluate performance by increasing the size of the labeled training set (e.g., 5%, 10%, 15%, 25%, 50%, 75%, 100%).

➤ Key Results and Performance Data

The quantitative results below demonstrate the efficacy of the self-supervised learning approach with limited labels.

Table 1: Incremental Training Performance (F1 Score) [35]

| Percentage of Labeled Data Used | Performance with SSL Pre-training | Performance from Scratch (ImageNet) |

|---|---|---|

| 5% | ~0.50 | ~0.31 |

| 10% | ~0.63 | ~0.45 |

| 15% | ~0.71 | ~0.55 |

| ~100 labels/class | ~0.80 | ~0.68 |

| 50% | ~0.88 | ~0.83 |

| 100% | ~0.91 | ~0.89 |

Table 2: Reagent and Computational Solutions

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Giemsa Stain | Standard staining reagent used on blood smears to make malaria parasites visible under a microscope [36] [37]. |

| ResNet50 Architecture | A deep convolutional neural network that serves as the core "backbone" for feature extraction from images [35]. |

| SimSiam Algorithm | A self-supervised learning method that learns visual representations from unlabeled data by maximizing similarity between different augmented views of the same image [35]. |

| SGD / Adam Optimizer | Optimization algorithms used to update the model's weights during training to minimize error [35]. |

| Weighted Cross-Entropy Loss | A loss function adjusted for imbalanced datasets, giving more importance to under-represented classes during training [35]. |

➤ Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is self-supervised learning particularly suited for parasite detection research? Manual annotation of medical images is time-consuming, expensive, and requires scarce expert knowledge [35]. SSL mitigates this by leveraging the abundance of unlabeled microscopy images already available in clinics. It learns general features of blood cells and parasites without manual labels, drastically reducing the number of annotated images needed later for specific tasks.

Q2: What is the minimum amount of labeled data needed to see a benefit from this SSL approach? The methodology shows a significant benefit even with very small amounts of data. Performance gains over training from scratch are most pronounced when using less than 25% of the full labeled dataset. With just 5-15% of labels, the SSL model can achieve F1 scores that are 0.2-0.3 points higher [35].

Q3: My dataset contains multiple parasite species with a severe class imbalance. How does this method handle that? The protocol includes specific strategies for class imbalance. During the supervised fine-tuning stage, a weighted cross-entropy loss function is used [35]. This assigns higher weights to under-represented classes during training, forcing the model to pay more attention to them and improving overall performance across all species.

Q4: Can I use a different backbone network or SSL algorithm? Yes. The ResNet50 and SimSiam combination is one effective configuration. The core concept is transferable. You could experiment with other encoders (e.g., Vision Transformers) or SSL methods (e.g., SimCLR, MoCo). However, SimSiam was chosen for its computational efficiency as it does not require large batch sizes or negative pairs [35].

➤ Troubleshooting Guide

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor performance even after SSL pre-training. | The unlabeled pre-training data is not representative of your target classification domain. | Ensure the unlabeled dataset comes from a similar source (same microscope type, staining protocol, etc.) as your labeled data. |

| Model fails to learn meaningful representations in SSL. | Inappropriate image augmentations are destroying biologically relevant features. | Review and tune the augmentation parameters (e.g., crop scale, color jitter strength) to ensure they generate realistic variations of microscopy images [35]. |

| Training is unstable or results in collapsed output. | This is a known risk in some SSL algorithms, though SimSiam uses a stop-gradient to prevent it [35]. | Double-check the implementation of the stop-gradient operation and the loss function. Ensure you are using the recommended hyperparameters. |

| Fine-tuning overfits to the small labeled dataset. | The model capacity is too high, or the learning rate is too aggressive for the small amount of data. | Try the "Linear Probe" strategy first before full fine-tuning. Implement strong regularization (e.g., weight decay, dropout) and use a lower learning rate. |

This technical support center document provides essential guidance for researchers integrating attention mechanisms like the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) into their deep-learning models, particularly within the context of parasite image analysis. A core challenge in this field is the reliance on large, manually labeled datasets, which are time-consuming and expensive to create. This guide is designed to help you effectively implement CBAM to enhance your model's feature extraction capabilities, which can improve performance and potentially reduce dependency on vast amounts of perfectly annotated data. The following sections offer troubleshooting advice, experimental protocols, and resource lists to support your research.

FAQs: Core Concepts of CBAM

Q1: What is CBAM and how does it help in feature extraction for medical images?

CBAM is a lightweight attention module that can be integrated into any Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to enhance its representational power [38] [39]. It sequentially infers attention maps along two separate dimensions: channel and spatial [38]. This allows the network to adaptively focus on 'what' (channel) is important and 'where' (spatial) the informative regions are in an image [40]. For parasite image analysis, this means the model can learn to prioritize relevant features, such as the structure of a specific parasite, while suppressing less useful background information, leading to more robust feature extraction [41].

Q2: Why should I use both channel and spatial attention? Isn't one sufficient?

While using either module can provide benefits, they are complementary and address different aspects of feature refinement [42]. Channel attention identifies which feature maps are most important for the task, effectively telling the network "what" to look for [40] [42]. Spatial attention, on the other hand, identifies "where" the most informative parts are located within each feature map [40] [42]. Using both sequentially provides a more comprehensive refinement of the feature maps, which has been shown to yield superior performance compared to using either one alone [38] [42].

Q3: Can the use of CBAM help in scenarios with limited or noisily labeled data?

Yes, this is a key potential benefit. By helping the network focus on meaningful features, CBAM can improve a model's robustness [38]. Research in digital pathology has shown that deep learning models can tolerate a certain level of label noise (around 10% in one study) without a significant performance drop [13]. When your model is guided by a powerful attention mechanism like CBAM to focus on salient features, it may become less likely to overfit to erroneous labels in the training set. However, the foundational data must still be of reasonably good quality, as severely mislabeled data can still lead to model degradation [43].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common CBAM Integration Issues

Problem 1: No Performance Improvement or Performance Degradation After Integration

- Possible Cause 1: Incorrect Placement of CBAM Modules. CBAM is designed to be integrated at every convolutional block within a network [38] [42]. Placing it only at the end may not allow for hierarchical feature refinement.

- Solution: Integrate CBAM modules after the convolution and activation layers within each core block of your network (e.g., within each ResNet block) [38] [44].

- Possible Cause 2: Over-refinement from Excessive Attention Modules. Adding too many attention modules or making them too complex can potentially overwhelm the network during initial training.

- Solution: Start with a standard implementation, such as integrating CBAM into a ResNet-50 architecture, and use the hyperparameters reported in successful studies [44] [42]. You can find official and unofficial implementations on GitHub to ensure correct structure [44] [45].

Problem 2: Exploding or Vanishing Gradients During Training

- Possible Cause: The sequential multiplication of attention maps can exacerbate gradient issues, especially in very deep networks.

- Solution: Ensure that standard stabilization techniques are correctly applied. Use Batch Normalization layers within the CBAM modules themselves, as is done in the spatial attention block [42]. Also, consider using residual connections in your base network (e.g., ResNet) to help gradient flow.

Problem 3: Model Overfitting to Noisy Labels in the Training Set

- Possible Cause: While CBAM can improve feature extraction, it is not immune to learning from incorrect supervisory signals if the training labels are noisy.

- Solution:

- Implement Robust Labeling Practices: Establish clear, detailed labeling guidelines for annotators, including examples of correct and incorrect labels, especially for ambiguous cases in parasite images [43].

- Leverage Automatic Labeling with Care: For large datasets, you can use automated tools to generate "weak" or noisy labels, but ensure the estimated noise level is below ~10% to prevent significant performance drops [13].

- Use Visualization Techniques: Employ methods like Grad-CAM or analyze the spatial attention maps produced by CBAM to understand what your model is focusing on. This can help you identify if the model is learning spurious correlations from mislabeled data [41].

Experimental Protocols & Performance Data

Protocol 1: Integrating CBAM into a Standard CNN

This protocol details how to integrate CBAM into a ResNet architecture for image classification.

- Base Model: Select a base CNN, such as ResNet-50 [44] [42].

- Integration Points: Insert the CBAM module after the convolution and activation within each residual block, before the final addition with the skip connection.

- CBAM Structure:

- Training: Use standard training protocols for the base model (e.g., on ImageNet). You can initialize with pre-trained weights and fine-tune.

Protocol 2: Evaluating CBAM for a Medical Imaging Task

This protocol is based on a study that used CBAM-augmented EfficientNetB2 for lung disease detection from X-rays [41].

- Dataset: Obtain a curated dataset of medical images (e.g., chest X-rays or whole-slide parasite images) with confirmed labels.

- Model Customization:

- Select a pre-trained EfficientNetB2 model.

- Integrate the CBAM module into the convolutional blocks.

- Add additional convolutional layers for improved feature extraction.

- Implement multi-scale feature fusion to capture features at different scales.

- Training & Evaluation:

- Train the model on your dataset.

- Use visualization techniques on the intermediate layers and attention maps to gain insights into the model's decision-making process [41].

- Evaluate on a held-out test set to measure performance metrics.

Quantitative Performance of CBAM-Enhanced Models

The tables below summarize the performance improvements observed from integrating CBAM.

Table 1: ImageNet-1K Classification Performance (ResNet-50) [44]

| Model | Top-1 Accuracy (%) | Top-5 Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Vanilla ResNet-50 | 74.26 | 91.91 |

| ResNet-50 + CBAM | 75.45 | 92.55 |

Table 2: Impact of Different Spatial Attention Configurations on ResNet-50 [42]

| Architecture (CAM + SAM) | Top-1 Error (%) | Top-5 Error (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Vanilla ResNet-50 | 24.56 | 7.50 |

| AvgPool + MaxPool, kernel=7 | 22.66 | 6.31 |

Table 3: Performance on a Medical Imaging Task (Lung Disease Detection) [41]

| Model | Task | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|

| CBAM-Augmented EfficientNetB2 | COVID-19, Viral Pneumonia, Normal CXR Classification | 99.3% Identification Accuracy |

Architectural Visualizations

Diagram 1: High-Level CBAM Workflow

Diagram 2: Detailed CBAM Architecture

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Components for CBAM Integration and Experimentation

| Item | Function / Description | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Base CNN Model | The foundational architecture to be enhanced with attention. | ResNet [44] [42], EfficientNet [41]. |

| CBAM Module | The core attention component for adaptive feature refinement. | Can be added to each convolutional block [38] [39]. |

| Deep Learning Framework | Software library for building and training models. | PyTorch [40] [44] [42] or TensorFlow. |

| Image Dataset | Domain-specific data for training and evaluation. | ImageNet-1K [38] [44], medical image datasets (e.g., chest X-rays [41], parasite images). |

| Visualization Toolkit | Tools for interpreting model decisions and attention. | Grad-CAM, tensorboardX [44], layer activation visualization [41]. |

| Automatic Labeling Tool | Software to generate initial labels, reducing manual effort. | Tools like Semantic Knowledge Extractor; requires <10% noise [13]. |

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

This technical support center addresses common challenges researchers face when building automated pipelines for parasite image analysis, with a focus on reducing reliance on manually labeled datasets.

Core Concepts and Setup

Q1: What is a data-centric AI strategy, and why is it crucial for parasite imagery research?

A data-centric AI strategy is a development approach that systematically engineers the data to build an AI system, rather than focusing solely on model architecture. For parasite research, this is crucial because the core challenge often originates from data issues—such as limited annotated datasets, high variability in image quality, and class imbalance—not from readily available benchmark data. This approach provides a framework to conceptually design an AI solution that is robust to the realities of biological data, enabling researchers to achieve reliable performance with minimal manual annotation. [46]

Q2: My deep learning model performs well on some parasite images but fails on others. What could be the cause?

This is a classic sign of a data issue, not a model issue. The likely cause is that your training dataset does not adequately represent the full spectrum of data variation in your problem domain. This includes variations in:

- Staining and Preparation: Differences in Giemsa staining intensity or fecal smear thickness. [47] [36]

- Microscope & Camera: Variations in optics, resolution, and lighting conditions. [36]

- Parasite Morphology: Different life-cycle stages (e.g., rings, trophozoites, schizonts in Plasmodium falciparum) and species. [36]

- Image Artifacts: Presence of impurities, platelets, or debris that can be confused with parasites. [36]

Solution: Adopt a data-centric framework that includes a phase for systematically assessing your dataset. Use a pre-trained model to analyze your raw image dataset in a latent space and identify the most representative samples for initial annotation, ensuring your training set covers the data diversity. [46]

Implementation and Workflow

Q3: What is a practical, step-by-step workflow for reducing manual labeling in a new parasite image project?

A proven workflow is the four-stage BioData-Centric AI framework: [46]

- Pre-training: Use self-supervised learning (e.g., Masked Autoencoder) on your entire unlabeled raw image dataset. This allows the model to learn general features and patterns of your specific image domain without any manual labels. [46]

- Assessing the Dataset: Use the pre-trained model to map all images into a latent space. Then, select a small "core set" of the most representative image patches for manual annotation. This maximizes the informational value of each manual label. [46]

- Hunting for Mistakes Iteratively: Use the initially trained model to predict on the remaining data and identify a "critical set" of images where it is most uncertain or makes errors. Manually curate only these hard cases and add them to the training set for model fine-tuning. Repeat this process. [46]

- Monitoring Performance: Once deployed, continuously monitor the model's performance on new data, even without ground truth, using techniques like Reverse Classification Accuracy (RCA) to estimate segmentation errors. [46]

The following diagram illustrates this iterative, human-in-the-loop workflow:

Q4: What are effective image pre-processing steps to improve model generalization for parasite detection?

Effective pre-processing is a key data-centric activity that enhances data quality before modeling. Recommended steps include:

- Denoising: Apply filters like Block-Matching and 3D Filtering (BM3D) to effectively remove Gaussian, Salt and Pepper, Speckle, and Fog noise from microscopic images. [48]

- Contrast Enhancement: Use Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) to improve contrast between parasites and the background, making features more distinct. [48]

- Normalization and Standardization: Normalize pixel intensities across all images to ensure consistent input to the model. This is a critical step to mitigate batch effects from different imaging sessions or equipment. [49]

- Cropping and Resizing: For high-resolution images, use a sliding window to crop images into smaller patches compatible with model input size, preserving fine morphological features. Always resize while maintaining aspect ratio to prevent distortion, using padding if necessary. [36]

Performance and Optimization

Q5: My model has high accuracy but I'm concerned about false negatives in parasite detection. How can I address this?

High accuracy can be misleading if there is a class imbalance (e.g., many more uninfected cells than infected ones). A model can achieve high accuracy by always predicting "uninfected." To address false negatives:

- Check your Evaluation Metrics: Rely on a suite of metrics, not just accuracy. Specifically, monitor Sensitivity (Recall) and F1-Score, which are more sensitive to false negatives. The table below shows the performance of various models on parasitic infection tasks, highlighting their sensitivity scores. [47] [24]

- Use Data Augmentation: Strategically augment the minority class (parasitized cells) by applying rotations, flips, slight blurring, and color variations to create more training examples and prevent the model from ignoring this class. [47]

- Investigate Model Architecture: For object detection tasks, models like YOLOv3 have demonstrated high recognition accuracy (94.41%) and low false-negative rates (1.68%) for Plasmodium falciparum in thin blood smears. [36]

Q6: How do I know if my dataset is large and diverse enough, and what can I do if it isn't?

- Assessment: A key data-centric practice is to lock your training and validation cohorts at the start of your study. If you find that you cannot train a stable model or the performance on the locked validation set is unacceptably low and highly variable, your dataset is likely insufficient. [49]

- Solutions:

- Leverage Self-Supervised Learning (SSL): Models like DINOv2 can learn powerful features from unlabeled images, achieving high accuracy (98.93%) even with limited labeled data resources (e.g., using only 10% of the data fraction). [24]

- Use Transfer Learning: Start with models pre-trained on large general image datasets (e.g., ImageNet). Fine-tuning these on your specific parasite imagery requires less data than training from scratch. For example, ResNet-50 has been successfully applied to malaria cell images with over 95% accuracy. [47] [24]

- Data Augmentation: As mentioned above, this is a primary tool for artificially increasing the size and diversity of your training data. [47]

Performance Comparison of Featured Models