Sanger Sequencing vs. NGS for Parasite Barcoding: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

This article provides a definitive comparison of Sanger sequencing and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) for DNA barcoding of parasitic organisms.

Sanger Sequencing vs. NGS for Parasite Barcoding: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a definitive comparison of Sanger sequencing and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) for DNA barcoding of parasitic organisms. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles, methodological applications, and key considerations for selecting the appropriate technology. We detail practical workflows for barcoding protozoans like Toxoplasma gondii and Trypanosoma brucei, address common troubleshooting and optimization challenges such as primer bias and host DNA contamination, and present a data-driven validation of performance metrics including sensitivity, cost, and throughput. The goal is to equip scientists with the knowledge to effectively apply these sequencing tools to advance studies in parasite genetics, epidemiology, and drug discovery.

DNA Sequencing Fundamentals: From Sanger to NGS Barcoding

Sanger sequencing, developed by Frederick Sanger in 1977, is a foundational DNA sequencing method known as the "chain-termination method." It is renowned for its high accuracy (99.99%) and remains the gold standard for validating DNA sequences, including those generated by next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms [1] [2] [3]. In parasite barcoding research, this accuracy is crucial for confirming the identity of specific pathogens, though the higher throughput of NGS is often better suited for discovering diverse or mixed parasite communities [4] [5].

Core Principle: The Chain Termination Method

The fundamental principle of Sanger sequencing is the random incorporation of chain-terminating dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs) during in vitro DNA replication. The process relies on the following key components [1] [2] [3]:

- Template DNA: The single-stranded DNA to be sequenced.

- Primer: A short oligonucleotide that binds to a known sequence adjacent to the target region.

- DNA Polymerase: The enzyme that synthesizes a new DNA strand.

- dNTPs: The four standard deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dATP, dGTP, dCTP, dTTP), which are the building blocks of DNA.

- ddNTPs: Dideoxynucleotide triphosphates (ddATP, ddGTP, ddCTP, ddTTP). These are chemically altered nucleotides that lack a 3'-hydroxyl group required for forming a phosphodiester bond with the next nucleotide [2] [3].

During the sequencing reaction, the DNA polymerase extends the primer by incorporating dNTPs that are complementary to the template strand. However, when a fluorescently labeled ddNTP is incorporated by chance, the absence of the 3'-OH group halts DNA strand elongation at that point. This results in a collection of DNA fragments of varying lengths, each terminating at a specific base type (A, T, G, or C) [1] [2].

These fragments are then separated by capillary electrophoresis based on their size. As each fragment passes a detector, the fluorescent label on the terminal ddNTP is excited by a laser. The resulting sequence of fluorescent signals is translated into a chromatogram, which displays the order of bases in the original DNA template [3].

Comparative Performance in Parasite Research

While Sanger sequencing provides high accuracy for single targets, NGS platforms offer superior throughput for detecting diverse parasite communities. The following table summarizes key differences in their application to parasite barcoding.

| Feature | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Principle | Chain termination with ddNTPs [1] | Parallel sequencing of millions of fragments [1] |

| Typical Read Length | 500–1000 bp [2] [6] | Varies by platform; can be shorter [1] |

| Accuracy | ~99.99% [1] [2] | High, but can be lower than Sanger; errors may be corrected statistically [1] |

| Cost per Sample | Lower for single genes [1] | More economical for high-throughput projects [1] |

| Throughput | Low; sequences one DNA fragment per reaction [1] | Very high; sequences millions of fragments simultaneously [1] |

| Ideal Use Case in Parasite Barcoding | Confirming identity of a specific parasite; validating NGS results [6] [5] | Detecting mixed-species infections; discovering novel parasites; comprehensive biodiversity studies [7] [8] [5] |

Supporting Experimental Data

A 2022 comparative analysis of NGS for Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance markers demonstrated the utility of both methods. In this study, SNP calls from both Illumina MiSeq and Ion Torrent PGM NGS platforms were in complete agreement with conventional Sanger sequencing, validating NGS for molecular surveillance. However, NGS offered a significant advantage in throughput and cost, reducing the cost by 86% compared to Sanger sequencing when multiplexing 96 samples per run [4].

For detecting complex parasitic communities, NGS shows clear superiority. A 2025 study on gastrointestinal parasites in ruminants used 18S rDNA NGS and identified 192 operational taxonomic units (OTUs), including 10 phyla and 27 genera of parasites. This depth of analysis would be impractical with Sanger sequencing [7]. Similarly, metabarcoding approaches can "bypass the limitations of traditional Sanger sequencing by enabling insight into intra-species genetic diversity and the delineation of mixed species/subtype infection" [5].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Sanger Sequencing Workflow for Parasite Identification

The following protocol is typical for generating sequence data from a parasite gene for barcoding purposes [9] [6] [3].

Step 1: DNA Extraction

Step 2: Target Amplification by PCR

- Design and optimize primers to amplify a specific genetic locus (e.g., 18S rRNA, cytochrome b) from the parasite.

- Primer Design: Primers should be 18–25 bases long with a calculated annealing temperature (Tm). Avoid secondary structures and repetitive sequences [9] [6].

- Perform PCR to amplify the target region. The amplicon should appear as a single, sharp band on an agarose gel.

Step 3: PCR Product Purification

- Purify the PCR product to remove excess primers, dNTPs, salts, and polymerase. This can be done using bead-based, column-based, or enzymatic clean-up kits. Purification is critical for a clean sequencing reaction [6].

Step 4: Sanger Sequencing Reaction

- The reaction mixture includes:

- Purified PCR product: 1–10 ng/µL.

- Sequencing primer: 3–10 pmol/µL.

- DNA polymerase: 0.5–1.0 U per 10 µL reaction.

- Buffer: Contains salts and cofactors.

- dNTPs: Standard deoxynucleotides.

- Fluorescently labeled ddNTPs: Chain-terminating nucleotides.

- The reaction undergoes thermal cycling: denaturation (96°C for 1 min), annealing (50–60°C for 20 sec), and extension (60°C for 4 min) for 25–35 cycles [9] [3].

- The reaction mixture includes:

Step 5: Post-Reaction Clean-Up

- Remove unincorporated ddNTPs and salts from the sequencing reaction products to reduce background noise.

Step 6: Capillary Electrophoresis

Step 7: Data Analysis

- Software converts the fluorescent data into a chromatogram. The base sequence is determined, and the chromatogram is manually or automatically reviewed for quality. Low-quality bases at the ends are often trimmed [6].

Next-Generation Metabarcoding for Parasite Diversity

This protocol highlights key differences from the Sanger approach, particularly in the amplification and sequencing steps [7] [8] [5].

Step 1: DNA Extraction

- Similar to Sanger sequencing, high-quality DNA is extracted from complex samples like feces or blood.

Step 2: Amplification of Barcode Region with Adapters

- Design universal primers that target a conserved, variable region (e.g., V4-V9 of 18S rDNA) across a broad range of parasites.

- Primers include adapter sequences that are compatible with the NGS platform (e.g., Illumina).

- To overcome high levels of host DNA in samples like blood, blocking primers (e.g., C3-spacer modified oligos or Peptide Nucleic Acids) can be added. These bind specifically to host DNA and prevent its amplification, thereby enriching for parasite DNA [8].

Step 3: Library Preparation and Sequencing

- The PCR products (amplicons) are purified, quantified, and pooled together in equimolar ratios into a "library."

- The library is loaded onto an NGS platform (e.g., Illumina MiSeq, portable nanopore). The system performs massively parallel sequencing, generating hundreds of thousands to millions of sequence reads in a single run [7].

Step 4: Bioinformatic Analysis

- Raw sequence reads are demultiplexed and filtered for quality.

- High-quality reads are clustered into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) or Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) based on sequence similarity.

- These are classified taxonomically by comparison to reference databases to identify the parasites present [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Template DNA | The source of genetic material from the parasite or host sample. High purity and integrity are critical for success [9] [6]. |

| Sequence-Specific Primers | Short DNA fragments that specifically bind to the target region, providing a starting point for DNA synthesis by polymerase [9] [6]. |

| DNA Polymerase | Enzyme that catalyzes the template-directed synthesis of new DNA strands during PCR and the sequencing reaction [9]. |

| dNTPs (dATP, dGTP, dCTP, dTTP) | The fundamental building blocks used by the DNA polymerase to extend the DNA chain [1] [2]. |

| Fluorescently Labeled ddNTPs | Chain-terminating nucleotides that halt synthesis and provide a fluorescent signal to identify the terminal base. Key to the Sanger method [2] [3]. |

| Blocking Primers (PNA/C3-spacer) | Used in NGS metabarcoding to inhibit the amplification of abundant host DNA, thereby enriching the sample for parasite DNA [8]. |

| Universal 18S rDNA Primers | Used in NGS metabarcoding to amplify a target gene from a wide range of eukaryotic parasites in a single reaction [7] [8] [5]. |

| Capillary Electrophoresis System | The instrument that separates terminated DNA fragments by size and detects their fluorescent signals to generate the sequence data [2] [3]. |

The field of genomic research has been transformed by the advent of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), which enables the parallel sequencing of millions of DNA fragments. This technological revolution is particularly impactful in specialized areas such as parasite barcoding, where accurate species identification is crucial for diagnosis, treatment, and understanding transmission dynamics. For decades, Sanger sequencing served as the gold standard for genetic analysis. However, when comparing these methodologies for parasite barcoding, significant differences in capability, throughput, and application emerge. This guide provides an objective comparison of Sanger sequencing and NGS technologies, framed within parasite barcoding research, to help scientific professionals select the most appropriate method for their investigative needs.

Performance Comparison: Sanger Sequencing vs. NGS

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of Sanger sequencing and NGS in the context of parasite barcoding, based on recent experimental studies.

| Feature | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Chain-termination with capillary electrophoresis [10] | Massive parallel sequencing of library fragments [8] [11] |

| Multiplexing / Multi-Species Detection | Not suitable for identifying multiple species in a single sample [10] | Capable of detecting multiple species or co-infections in a single run [8] [10] |

| Typical Barcoding Read Structure | Single, continuous sequence read | Millions of short (Illumina) or long (Nanopore) reads [8] [12] |

| Sample Throughput | Low (one sample per run) | High (dozens to hundreds of samples multiplexed in one run) [13] |

| Sensitivity in Complex Samples | Can fail if host DNA overwhelms the sample or in mixed infections [10] | Can be combined with host DNA blocking primers to enrich for parasite DNA [8] [14] |

| Primary Barcoding Application | Identification of single parasites from pure samples or cultures | Comprehensive detection, species identification, and strain typing directly from clinical samples [8] [15] |

| Relative Cost and Speed | Lower cost per sample for small batches; faster turnaround for single samples | Higher startup cost, but lower cost per sample for high-throughput projects; rapid results with portable devices [15] |

Experimental Insights and Protocols

Supporting data for the comparison table comes from direct experimental applications of both technologies in parasite research.

Case Study 1: Mosquito Surveillance

A 2024 study directly compared a multiplex PCR protocol with DNA barcoding via Sanger sequencing for identifying container-breeding Aedes mosquito species from ovitraps [10].

- Sanger Sequencing Protocol: DNA was extracted from eggs, and the mitochondrial COI gene was amplified by PCR. The resulting amplicons were then sequenced using the Sanger method [10].

- Results: The multiplex PCR identified species in 1990 out of 2271 samples, while Sanger sequencing was successful in only 1722 samples. Furthermore, the multiplex PCR (an NGS-like approach) detected mixtures of different species in 47 samples, a feat not achievable with the standard Sanger sequencing workflow used in the study [10].

Case Study 2: Blood Parasite Detection with Nanopore NGS

A 2025 study developed a targeted NGS approach for blood parasites using a portable nanopore sequencer, highlighting key advantages of modern NGS [8] [14].

- NGS Protocol:

- Primer Design: Use of universal primers targeting the V4-V9 hypervariable regions of the 18S rDNA gene to achieve species-level resolution across a broad range of parasites [8] [14].

- Host DNA Suppression: Incorporation of two blocking primers—a C3 spacer-modified oligo and a Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA) oligo—to selectively inhibit the amplification of overwhelming host 18S rDNA, thereby enriching parasite DNA [8] [14].

- Sequencing & Analysis: Library preparation and sequencing on a portable nanopore platform, with subsequent bioinformatic analysis for species identification [8].

- Results: The assay demonstrated high sensitivity, detecting Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense, Plasmodium falciparum, and Babesia bovis in spiked human blood samples with concentrations as low as 1, 4, and 4 parasites per microliter, respectively. It also successfully revealed multiple Theileria species co-infections in field cattle blood samples [8].

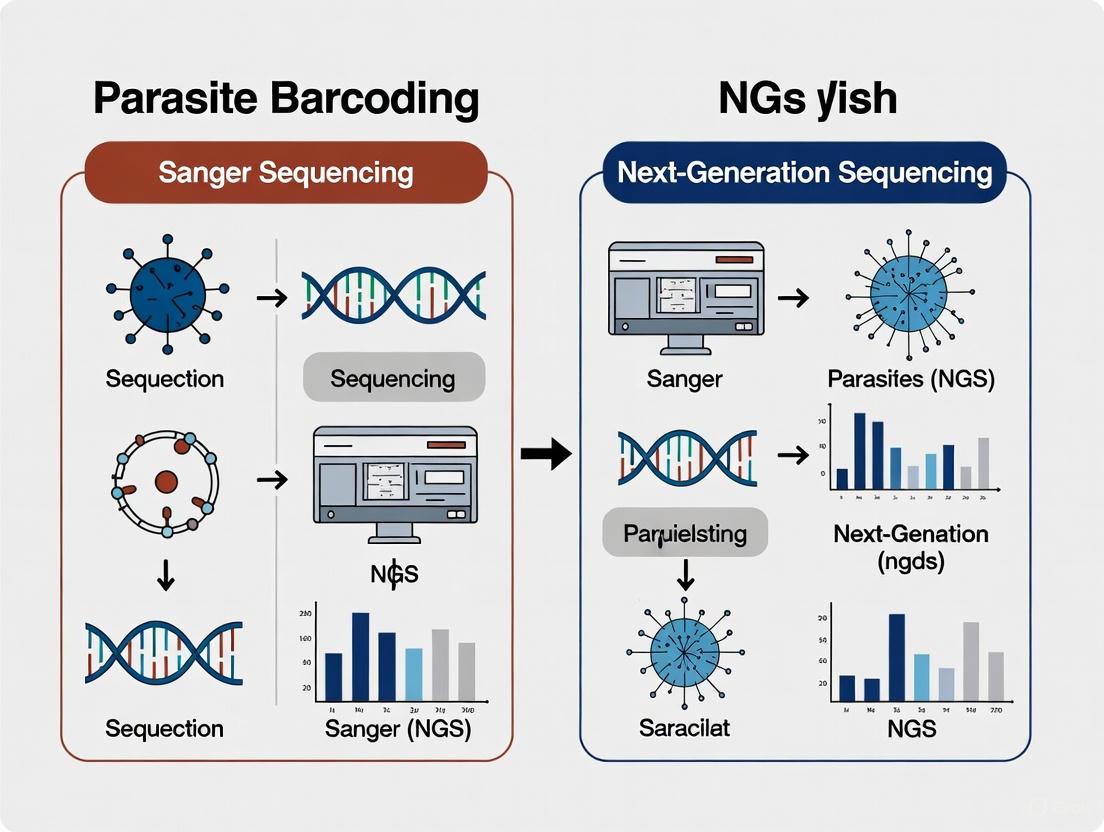

Visualizing the NGS Barcoding Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for amplicon-based NGS barcoding of parasites, integrating the key steps from the described protocols.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key reagents and materials used in NGS-based parasite barcoding, as featured in the cited experiments.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Parasite Barcoding |

|---|---|

| Universal 18S rDNA Primers | Amplify a conserved but variable genetic region across a wide range of eukaryotic parasites for species identification [8] [11]. |

| Host-Blocking Primers (PNA/C3) | Sequence-specific oligos that bind to host DNA and inhibit its amplification during PCR, dramatically enriching the relative proportion of parasite DNA in the sample [8] [14]. |

| Portable Nanopore Sequencer | A compact, low-cost sequencing device that enables real-time, long-read sequencing, making NGS feasible in resource-limited settings [8] [15]. |

| Characterized Reference Materials | Well-defined control samples (e.g., metagenomic controls, WHO reagents) essential for validating and standardizing NGS methods across different laboratories [12]. |

| Barcoded Index Adapters | Short, unique DNA sequences added to each sample's amplicons, allowing multiple samples to be pooled, sequenced in a single run, and computationally separated afterward [16] [13]. |

The revolution brought by NGS is evident in parasite barcoding research. While Sanger sequencing remains a reliable and cost-effective tool for identifying single organisms or validating results, NGS technologies offer unparalleled power for comprehensive pathogen detection, species differentiation, and understanding complex co-infections. The choice between them is not a matter of which is universally better, but which is more appropriate for the specific research question. For high-throughput surveillance, detecting unknown pathogens, or analyzing complex samples with mixed infections, NGS provides a depth of data that Sanger sequencing cannot match. As NGS protocols continue to be refined for simplicity, speed, and deployment in field settings, their role in advancing parasitology and global public health will only grow more prominent.

Defining DNA Barcoding and Its Critical Role in Parasitology

DNA barcoding has emerged as a revolutionary method for species identification in parasitology, providing unprecedented precision in distinguishing parasites and vectors. This method utilizes short, standardized gene regions to create genetic identifiers for species, overcoming limitations of traditional morphological identification. With the advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS), DNA barcoding has transformed into a high-throughput tool capable of processing hundreds of specimens simultaneously. This review comprehensively compares Sanger sequencing and NGS platforms for parasite barcoding, examining their technical capabilities, applications, and experimental protocols to guide researchers in selecting appropriate methodologies for parasitological research and diagnostics.

DNA barcoding is a molecular method for species identification that uses a short, standardized DNA sequence from a specific gene or genes [17]. The fundamental premise is that by comparing an unknown DNA sequence against a reference library of authenticated sequences, organisms can be identified to species level with high accuracy—analogous to how a supermarket scanner identifies products using UPC barcodes [17]. This approach has proven particularly valuable in parasitology, where morphological identification can be challenging due to the small size of many parasites, their complex life cycles, and the existence of cryptic species complexes [18] [19].

In the context of parasites and vectors, DNA barcoding provides several critical advantages over traditional methods. It enables identification of immature life stages that lack diagnostic morphological characters, differentiation of morphologically identical cryptic species with divergent medical significance, and detection of parasites in mixed infections or from environmental samples [17] [18]. For example, the technique can distinguish between the pathogenic Entamoeba histolytica and its non-pathogenic relative Entamoeba dispar, which are morphological twins but have vastly different clinical implications [5]. The utility of DNA barcoding extends across diverse parasitological applications, including epidemiological studies, vector control programs, biodiversity assessments, and understanding complex host-parasite interactions [19].

DNA Barcoding Markers for Parasites

The selection of appropriate genetic markers is fundamental to successful DNA barcoding. Ideal barcode regions combine sufficient variability to distinguish between species with conserved flanking regions for universal primer binding [17]. Different marker genes are employed for various parasite groups, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

Table 1: Standard DNA Barcoding Markers for Parasites

| Organism Group | Primary Barcode Marker | Alternative Markers | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animals & Helminths | Cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) [17] | Cytb, 12S, 16S [17] | Identification of nematodes, trematodes, cestodes, and arthropod vectors [19] |

| Protozoa | 18S rRNA (SSU) [14] [11] | COI [20] | Detection of Plasmodium, Trypanosoma, Leishmania, Giardia, Cryptosporidium [5] [19] |

| Fungi & Microsporidia | Internal transcribed spacer (ITS) [17] | 28S LSU rRNA [17] | Identification of microsporidian parasites [5] |

| Plants | rbcL, matK [17] | - | Identification of plant-derived parasites or hosts |

For parasitic helminths and arthropod vectors, the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) gene serves as the primary barcode region [17] [19]. This marker provides strong species-level discrimination across diverse animal taxa, with the "Folmer region" (approximately 658 base pairs) serving as the standard fragment for amplification and sequencing [17]. For protozoan parasites, the small subunit ribosomal RNA (18S rRNA) gene has emerged as the most commonly used barcode due to its appropriate evolutionary rate and comprehensive database coverage [14] [5] [11]. The 18S gene contains both conserved regions for primer design and variable regions (V4-V9) that provide species discrimination [14]. Research demonstrates that longer 18S fragments (e.g., V4-V9 spanning >1 kb) significantly improve species identification accuracy, especially when using error-prone sequencing platforms like Oxford Nanopore [14].

Sequencing Platforms for DNA Barcoding

Sanger Sequencing: The Traditional Approach

First-generation Sanger sequencing, based on the chain termination method using dideoxynucleoside triphosphates (ddNTPs), served as the foundational technology for DNA barcoding for nearly three decades [21] [22]. The method involves DNA synthesis from a single-stranded template with termination at specific points using fluorescently labeled ddNTPs, followed by fragment separation via capillary electrophoresis [21].

Sanger sequencing produces long, contiguous reads (500-1000 bp) with exceptionally high per-base accuracy (typically >99.999%) [21]. This makes it ideal for obtaining full-length barcode sequences from individual specimens with unambiguous results. However, the technology is fundamentally limited by low throughput, typically processing only individual samples or small batches per run [21] [20]. Additional limitations include the requirement for high-quality, high-quantity DNA template (100-500 ng) and difficulties resolving mixed infections or heteroplasmy due to its production of a single sequencing signal pattern [20].

Next-Generation Sequencing: High-Throughput Solutions

Next-generation sequencing platforms overcome many limitations of Sanger sequencing through massively parallel sequencing, enabling millions to billions of DNA fragments to be sequenced simultaneously [21] [22]. This high-throughput capability has revolutionized DNA barcoding applications in parasitology, particularly for large-scale biodiversity surveys, mixed infection detection, and environmental sampling [20] [5].

Table 2: Comparison of Sequencing Platforms for Parasite DNA Barcoding

| Platform/Technology | Sequencing Principle | Max Read Length | Throughput per Run | Key Advantages for Parasitology | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanger Sequencing [21] | Chain termination with ddNTPs | 500-1000 bp | Low (individual samples) | Gold standard accuracy; long contiguous reads; simple data analysis | Low throughput; cannot resolve mixed templates; high cost per sample |

| Illumina [22] | Sequencing by synthesis with reversible dye-terminators | 36-300 bp | High (millions to billions of reads) | Low cost per base; high accuracy; ideal for metabarcoding | Short reads limit phylogenetic utility; requires complex bioinformatics |

| 454 Pyrosequencing [20] [22] | Detection of pyrophosphate release during nucleotide incorporation | 400-1000 bp | Medium (~1 million reads) | Longer reads beneficial for complex barcodes; good for amplicon sequencing | Higher cost; production discontinued; homopolymer errors |

| Oxford Nanopore [14] [22] [23] | Electrical signal detection as DNA passes through protein nanopores | 10,000-30,000 bp | Variable (portable to high-throughput) | Ultra-long reads; portable sequencing; real-time analysis; minimal infrastructure | Higher error rates (~5-15%); requires specialized analysis |

| PacBio SMRT [22] [23] | Real-time sequencing by synthesis in zero-mode waveguides | 10,000-25,000 bp | Medium to High | Long reads; minimal GC bias; detects epigenetic modifications | Higher cost per sample; lower throughput than Illumina |

NGS technologies enable two primary approaches for parasite barcoding: amplicon-based NGS (metabarcoding), where specific barcode regions are amplified and sequenced from single or mixed specimens, and metagenomic NGS, where total DNA from a sample is sequenced without targeted amplification [5]. Amplicon-based NGS is particularly valuable in parasitology as it allows for highly sensitive detection of multiple parasite species in a single sample and can reveal mixed infections and genetic diversity within species [5] [11].

Comparative Analysis: Sanger Sequencing vs. NGS for Parasite Barcoding

Performance Metrics and Experimental Data

Direct comparisons between Sanger sequencing and NGS platforms reveal distinct performance characteristics that influence their suitability for different parasitological applications. A 2014 study directly compared Sanger sequencing with 454 pyrosequencing for DNA barcoding of 190 Lepidoptera specimens, demonstrating that NGS could recover full-length DNA barcodes for all but one specimen while simultaneously detecting additional genetic information such as Wolbachia infections, nontarget species, and heteroplasmic sequences [20]. The NGS approach provided an average of 143 sequence reads per specimen, enabling statistical confidence in sequence variants that would be ambiguous with Sanger sequencing [20].

A 2023 comparison of third-generation sequencing platforms for DNA barcoding applications found that Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) with R10 & Q20+ chemistry achieved the highest sample success rate, while ONT protocols required the shortest library preparation time [23]. The study also calculated economic break-even points, determining that third-generation platforms become more cost-effective than Sanger sequencing when studies require barcoding of more than 61 (Flongle), 183 (MinION), or 356 (PacBio) samples [23].

For diagnostic applications, a 2024 study optimized 18S rRNA metabarcoding for simultaneous detection of 11 intestinal parasite species (Clonorchis sinensis, Entamoeba histolytica, Dibothriocephalus latus, Trichuris trichiura, Fasciola hepatica, Necator americanus, Paragonimus westermani, Taenia saginata, Giardia intestinalis, Ascaris lumbricoides, and Enterobius vermicularis) using Illumina iSeq 100 platform [11]. The method successfully detected all species in a single run, though read counts varied substantially between species (0.9-17.2% of total reads), influenced by factors such as DNA secondary structure and PCR annealing temperature [11].

Technical Workflows: Traditional vs. Modern Approaches

The experimental workflows for Sanger sequencing versus NGS in parasite barcoding involve distinct procedures with implications for laboratory efficiency and data output.

DNA Barcoding Workflows: Sanger vs. NGS

The key distinction between these workflows lies in their parallelism. Sanger sequencing processes specimens individually throughout the entire workflow, while NGS incorporates sample multiplexing early in the process, enabling parallel processing of hundreds to thousands of specimens [21] [20]. The NGS approach also includes a more complex bioinformatic pipeline requiring specialized computational resources for demultiplexing, quality filtering, sequence alignment, and variant calling [21].

Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Barcoding Experiments

Successful implementation of DNA barcoding protocols requires specific reagents and materials tailored to different experimental approaches.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for DNA Barcoding Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Sanger Sequencing | NGS Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits (e.g., Nucleospin Tissue Kit [20]) | Isolation of high-quality DNA from diverse sample types | Required (high-quality template essential) | Required (quality less critical due to coverage depth) |

| Barcoding Primers (e.g., LepF1/LepR1 for COI [20]) | Amplification of target barcode region | Standard primers without adapters | Modified with sequencing adapters and sample indices |

| PCR Enzymes (e.g., Platinum Taq Polymerase [20]) | Amplification of barcode region | Standard formulation | High-fidelity enzymes to minimize amplification errors |

| Multiple Identifiers (MIDs) [20] | Unique oligonucleotide tags for sample multiplexing | Not required | Essential for pooling specimens in NGS runs |

| Blocking Primers (e.g., C3 spacer-modified oligos, PNA [14]) | Suppress amplification of host DNA | Rarely used | Critical for host-derived samples (e.g., blood, tissues) |

| Library Prep Kits (Platform-specific) | Prepare amplicons for sequencing | Not required | Essential for all NGS platforms |

| Bioinformatic Tools (e.g., QIIME2, DADA2 [11]) | Data processing and analysis | Basic alignment software | Sophisticicated pipeline required for demultiplexing, variant calling |

The selection of blocking primers represents a particularly important advancement for parasite barcoding from host-derived samples. A 2025 study developed novel blocking primers including a C3 spacer-modified oligo competing with the universal reverse primer and a peptide nucleic acid (PNA) oligo that inhibits polymerase elongation, significantly improving detection of blood parasites by reducing host DNA amplification [14].

Applications in Parasitology

Species Identification and Discovery

DNA barcoding has proven invaluable for the identification and discovery of parasite species, particularly for morphologically cryptic complexes. Research indicates that DNA barcodes provide highly accurate species identification in 94-95% of cases when compared with author identifications based on morphology or other markers [19]. This accuracy is especially important for medically important parasites where misidentification can have significant clinical consequences.

By 2014, DNA barcode coverage had reached 43% of 1,403 medically important parasite and vector species, with even higher coverage (over 50%) for species of greater medical importance [19]. This growing database enables more comprehensive identification capabilities and supports the discovery of novel species through the identification of divergent barcode sequences that may represent previously unrecognized taxa [18] [19].

Mixed Infection and Genetic Diversity Analysis

NGS-based DNA barcoding enables detailed analysis of mixed parasite infections and intra-species genetic diversity that would be impossible with Sanger sequencing. Amplicon-based NGS can detect multiple parasite species in a single sample and identify mixed subtype infections within a single host [5]. For example, studies of Blastocystis and Giardia have revealed extensive genetic diversity and frequent mixed infections that were previously undetectable with Sanger sequencing [5].

This capability provides crucial insights into parasite epidemiology, transmission dynamics, and potential drug resistance. A study on Cryptosporidium demonstrated that NGS could uncover within-host genetic diversity and delineate mixed subtype infections that were missed by Sanger sequencing [5]. This higher resolution enables more precise tracking of transmission routes and identification of potentially divergent strains with different clinical outcomes or treatment responses.

Environmental Sampling and One Health Approaches

DNA metabarcoding extends the utility of barcoding to complex environmental samples, enabling comprehensive surveillance of parasites in ecosystems. This approach aligns with One Health perspectives that recognize the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health. Applications include:

- Detection of zoonotic Cryptosporidium species in water catchments [5]

- Monitoring parasite diversity in river water and sediment using next-generation sequencing [5]

- Identification of parasite assemblages in wildlife and livestock reservoirs [5]

- Comprehensive screening of commercial products for parasite contamination [20]

These environmental applications provide early warning systems for emerging parasitic diseases and enable more effective management of zoonotic transmission risks.

DNA barcoding has fundamentally transformed parasitology by providing precise, standardized methods for species identification that overcome the limitations of morphological approaches. The technique has evolved from individual specimen processing with Sanger sequencing to high-throughput analysis of complex samples using NGS technologies. While Sanger sequencing remains the gold standard for confirming specific variants and processing small numbers of samples, NGS platforms offer superior capabilities for large-scale surveys, detection of mixed infections, and comprehensive biodiversity assessments.

The choice between sequencing technologies depends on multiple factors including project scale, required resolution, available resources, and specific research questions. For targeted confirmation of known parasites or small-scale projects, Sanger sequencing provides accuracy and simplicity. For large-scale biodiversity assessments, detection of cryptic diversity, or analysis of complex samples, NGS approaches offer unparalleled throughput and resolution. As sequencing technologies continue to advance, with improvements in accuracy, read length, and portability, DNA barcoding will play an increasingly central role in parasitological research, disease surveillance, and control programs.

For decades, Sanger sequencing has served as the cornerstone of molecular parasitology, providing reliable data for species identification and genotyping. However, its limitations in detecting mixed infections and resolving complex within-host diversity have become increasingly apparent. The emergence of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies addresses these limitations by offering unparalleled depth and resolution, revolutionizing how researchers study parasite populations.

This paradigm shift is particularly impactful for barcoding studies targeting key parasitic protists: Entamoeba, Cryptosporidium, Giardia, and Plasmodium. Each genus presents unique diagnostic and epidemiological challenges, from distinguishing pathogenic Entamoeba histolytica from non-pathogenic Entamoeba dispar to unraveling the complex subtype diversity of Giardia and Cryptosporidium in outbreak settings. This guide objectively compares the performance of Sanger sequencing and NGS barcoding for these parasites, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies to inform research and diagnostic development.

Performance Comparison: Sanger Sequencing vs. NGS Barcoding

The following table summarizes key performance metrics for Sanger sequencing and NGS based on published experimental studies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Sanger Sequencing and NGS for Parasite Barcoding

| Parasite Genus | Key Genetic Target(s) | Sanger Sequencing Limitations | NGS Advantages | Supporting Experimental Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entamoeba | 18S rRNA gene [24] | Cannot differentiate mixed archamoebid infections; lower sensitivity [25]. | Detects and differentiates mixed species/subtype infections in a single run [25] [5]. | Metabarcoding detected E. dispar, E. hartmanni, and E. coli RL1/RL2 in 61% (22/36) of samples [25]. |

| Cryptosporidium | gp60 gene [26] | Fails to detect minority variants in mixed infections [26]. | Identifies multiple subtype families and within-subtype diversity simultaneously [26]. | NGS detected minority variants (0.1-1%) in controlled mixtures; Sanger sequencing failed to detect them [26]. |

| Giardia | gdh, bg, tpi genes [27] [28] | Produces mixed chromatograms or misses rare types in mixed assemblages [27]. | Reveals extensive within-host subtype diversity and identifies shared outbreak strains [27]. | Metabarcoding identified multiple G. intestinalis subtypes in 13/16 human samples; Sanger sequencing missed shared outbreak strains [27]. |

| Plasmodium | Pfrh3 (for cellular barcoding), 18S rRNA [14] [29] | Low-throughput for competitive growth or fitness assays [29]. | Enables high-throughput, multiplexed tracking of barcoded strains for fitness and drug studies [29]. | Barcode sequencing (BarSeq) quantified growth dynamics of 6 uniquely barcoded P. falciparum lines in a single coculture [29]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Multiplex Real-Time PCR for Stool Protozoa

Application: Simultaneous detection and differentiation of Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia lamblia, and Cryptosporidium parvum from stool samples [24].

- DNA Extraction: Fecal suspensions are subjected to a sodium dodecyl sulfate-proteinase K treatment (2 hours at 55°C). DNA is then isolated using spin column technology (e.g., QIAamp tissue kit). An internal control (e.g., phocin herpesvirus 1) is added to the lysis buffer to monitor PCR inhibition [24].

- Primer and Probe Design: Species-specific primers and TaqMan probes are designed to target the small-subunit (SSU) rRNA gene for E. histolytica and G. lamblia, and a 138-bp fragment for C. parvum. The E. histolytica probe is designed to specifically bind to the pathogenic species and not the morphologically identical E. dispar [24].

- PCR Amplification: The multiplex real-time PCR is performed in a single tube containing all primer and probe sets. The reaction conditions are optimized to ensure 100% specificity and sensitivity as validated on well-defined stool samples and control DNA [24].

Metabarcoding for Complex Eukaryotic Communities

Application: Broad detection and differentiation of eukaryotic protists in fecal or environmental samples using 18S rDNA [25] [5].

- Library Preparation: This protocol involves a two-step PCR approach.

- Primary Amplification: Universal eukaryotic primers targeting hypervariable regions of the 18S rRNA gene (e.g., V3-V4, V4-V9) are used to generate the primary amplicon from fecal DNA [25].

- Indexing PCR: A second, limited-cycle PCR is performed to add dual indices and sequencing adapters required for the NGS platform (e.g., Illumina MiSeq) [25].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Sequencing reads are demultiplexed, quality-filtered, and clustered into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) or Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs). These are then classified taxonomically by comparison against curated reference databases (e.g., SILVA, in-house databases) to determine the species and subtypes present [25] [5].

Cellular Barcoding for Within-Host Population Dynamics

Application: Tracking the population dynamics and tissue colonization of parasites like Plasmodium falciparum and Toxoplasma gondii during infection [29] [30].

- Barcode Library Generation: A library of dozens to hundreds of unique DNA barcode sequences (e.g., 11 bp for P. falciparum, 60 nt for T. gondii) is cloned into a donor vector flanked by homology arms for a specific genomic locus (e.g., the non-essential pfrh3 or uprt gene) [29] [30].

- CRISPR/Cas9 Transfection: Parasites are co-transfected with the pool of barcoded donor vectors and a CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid that induces a double-strand break at the target locus. Homology-directed repair integrates a single barcode into the genome of individual parasites [29] [30].

- Pooled Phenotyping and Barcode Sequencing (BarSeq): A population of uniquely barcoded parasites is pooled and subjected to in vitro or in vivo assays (e.g., drug pressure, growth competition, host infection). Genomic DNA is extracted at different time points, and the barcode region is amplified and sequenced. The relative abundance of each barcode is quantified to track clonal dynamics within the population [29] [30].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for cellular barcoding of protozoan parasites.

Figure 1: Workflow for cellular barcoding of protozoan parasites to study population dynamics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of parasite barcoding requires specific reagents and tools. The following table lists key solutions used in the protocols cited in this guide.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Parasite Barcoding

| Reagent / Solution | Critical Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Universal 18S rDNA Primers (e.g., F566 & 1776R [14]) | Amplify a broad range of eukaryotic parasites from complex samples for metabarcoding. | Detection of apicomplexan and euglenozoan parasites from blood samples [14]. |

| Blocking Primers (C3 spacer-modified oligos, PNA oligos [14]) | Selectively inhibit amplification of host DNA (e.g., human, mammalian 18S rDNA) to enrich for parasite sequences. | Improving sensitivity of blood parasite detection by suppressing overwhelming host DNA background [14]. |

| Species-Specific TaqMan Probes (e.g., MGB probes [24]) | Enable specific detection and quantification of target parasite DNA in multiplex real-time PCR assays. | Differentiating pathogenic E. histolytica from non-pathogenic E. dispar in stool samples [24]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System & Donor Vectors | Enable precise integration of unique DNA barcodes into specific, non-essential parasite genomic loci. | Generating libraries of barcoded P. falciparum or T. gondii strains for competitive growth assays [29] [30]. |

| Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) Donor Templates (60-120 nt ss/ds oligos [30]) | Serve as the template for precise CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing, carrying the unique barcode sequence. | Cellular barcoding of T. gondii at the UPRT locus and T. brucei at the AAT6 locus [30]. |

The evidence from contemporary studies clearly demonstrates that NGS-based barcoding surpasses Sanger sequencing in critical areas for parasite research: detecting mixed infections, unraveling within-host diversity, and enabling high-throughput functional genomics. While Sanger sequencing remains a valuable tool for specific, single-target questions, NGS provides a more comprehensive and realistic view of parasite populations in clinical, environmental, and experimental contexts.

The choice between these technologies ultimately depends on the research question. For routine genotyping of a known, single-species infection, Sanger may suffice. However, for investigating outbreaks, understanding transmission dynamics, quantifying fitness costs of drug resistance, or discovering cryptic species, NGS barcoding is the unequivocally superior tool, providing the depth and breadth of data needed to advance the field of molecular parasitology.

The field of DNA sequencing has undergone a revolutionary transformation, evolving from techniques that read single gene fragments to technologies that can simultaneously process millions of DNA molecules. This evolution has profoundly impacted diverse areas of biological research, including parasitology, where accurate species identification and drug resistance profiling are paramount. For researchers tracking parasitic infections, the choice of sequencing technology directly influences diagnostic accuracy, depth of genetic information, and the ability to detect mixed infections or novel strains. Each generation of sequencing technology—from the first-generation Sanger method, to the second-generation massively parallel platforms like Illumina, to the third-generation single-molecule real-time approaches such as Oxford Nanopore—has brought distinct advantages and limitations. This guide provides an objective comparison of these platforms within the context of parasite barcoding research, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in their selection of appropriate genomic tools.

Technology Platform Comparison

Sequencing technologies are categorized into generations based on their underlying biochemistry and operational scale. First-generation sequencing, represented by the Sanger method, separates single DNA fragments. Second-generation or next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms, such as Illumina, perform massively parallel sequencing of clonally amplified DNA fragments. Third-generation technologies, including Oxford Nanopore, sequence single molecules in real time, producing significantly longer reads [31].

Performance Metrics for Parasite Research

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of each platform relevant to parasite barcoding studies, with data drawn from recent applications in the field.

Table 1: Sequencing Platform Comparison for Parasite Barcoding Applications

| Feature | Sanger Sequencing | Illumina (MiSeq) | Oxford Nanopore |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generation | First | Second | Third |

| Read Length | Up to ~1000 bp [32] | Short reads (e.g., 2x300 bp) [4] | Long reads (>1 kb demonstrated for 18S rDNA) [14] |

| Throughput | Low (single fragment) | High (millions of fragments) [33] | Moderate to High (varies by device) |

| Accuracy | High (~99.99%) [34] | High [4] | Lower than Illumina; improved with workflow [14] [35] |

| Cost per Sample | Cost-effective for <20 targets [33] | ~$75-$130 for targeted NGS (tNGS) [31] | Varies; portable options reduce capital cost |

| Typical Turnaround Time | Fast for small batches | 1-3 days | Real-time data streaming; minutes to hours after library prep |

| Sensitivity for Minor Variants | Low (limit of detection ~15-20%) [33] | High (can detect down to 1% minor alleles) [4] [33] | Can detect low-frequency variants, but error rate can be a confounder [35] |

| Key Parasitology Application | Validating known variants, single-gene sequencing [32] | Targeted NGS for drug resistance markers [4], 18S rDNA metabarcoding [7] | In-field species identification [14] [36], long-read barcoding |

Supporting Experimental Data in Parasitology

A direct comparative study of Targeted Amplicon Deep sequencing (TADs) for Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance markers on Ion Torrent PGM (a second-generation platform similar to Illumina) and Illumina MiSeq found that both platforms showed 99.83% sequencing accuracy and 99.59% variant accuracy when compared to Sanger sequencing. However, Illumina MiSeq provided a significantly higher average read coverage per amplicon (28,886 reads) compared to the Ion Torrent PGM (1,754 reads). Both NGS platforms could reliably detect minor alleles in artificial mixtures down to a 1% density, a level of sensitivity unattainable by standard Sanger sequencing [4].

In a comparison more relevant to field applications, a study on detecting aquatic invasive species and their parasites found that Illumina sequencing remained more efficient at assigning species-level taxonomy from eDNA samples. Interestingly, for an intracellular cryptic parasite (S. destruens), Illumina failed to detect the parasite while Nanopore returned positive identifications at multiple sites, a discrepancy potentially attributable to different bioinformatic approaches or the higher error rate of Nanopore leading to misassignments [35].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To illustrate how these technologies are applied in practice, below are detailed methodologies from key studies cited in this guide.

Protocol: Targeted NGS for Pf Drug Resistance Markers (Illumina/Ion Torrent)

This protocol, adapted from a 2022 Scientific Reports paper, outlines the steps for using TADs to genotype antimalarial drug resistance genes in P. falciparum [4].

- Sample Collection and DNA Extraction: Genomic DNA is extracted from whole blood samples or blood spots from Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs).

- Multiplex PCR Amplification: Target amplicons for genes of interest (e.g., pfcrt, pfdhfr, pfdhps, pfmdr1, pfkelch, and pfcytochrome b) are amplified using a multiplex PCR reaction.

- Library Preparation:

- For Ion Torrent PGM: Amplicons are barcoded and ligated to platform-specific adapters. The library is then clonally amplified on ion sphere particles via emulsion PCR.

- For Illumina MiSeq: Amplicons are similarly barcoded and adapted. The library is loaded onto a flow cell where bridge amplification generates clonal clusters.

- Sequencing: The prepared library is sequenced on the respective platform. The study used the Ion Torrent PGM and Illumina MiSeq.

- Data Analysis: Raw sequencing reads are aligned to a P. falciparum reference genome (e.g., strain 3D7). Variant calling is performed to identify single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with drug resistance. The results can be validated against conventional Sanger sequencing.

Protocol: 18S rDNA Barcoding for Blood Parasites (Nanopore)

This protocol, from a 2025 Scientific Reports paper, describes a targeted NGS approach for comprehensive blood parasite detection using the portable Nanopore platform [14].

- Primer Design: Universal primers (F566 and 1776R) targeting the V4–V9 hypervariable regions of the 18S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) gene are selected to cover a wide range of eukaryotic parasites and generate a >1 kb amplicon for improved species-level resolution.

- Blocking Primer Design: To overcome the challenge of overwhelming host DNA in blood samples, two blocking primers are designed:

- A C3 spacer-modified oligo that competes with the universal reverse primer for binding to host 18S rDNA.

- A Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA) oligo that binds to the host sequence and inhibits polymerase elongation.

- PCR Amplification with Host Suppression: The target 18S rDNA region is amplified from sample DNA using the universal primers in the presence of the blocking primers. This selectively suppresses the amplification of host (mammalian) 18S rDNA, thereby enriching for parasite DNA.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: The amplified products are prepared into a sequencing library using the Ligation Sequencing Kit and loaded onto a MinION flow cell (Oxford Nanopore).

- Real-Time Analysis and Species ID: Sequencing occurs in real-time. The generated reads are basecalled in real-time and aligned against a database of 18S rDNA sequences for species identification.

Workflow and Technology Selection

The following diagram visualizes the core workflows for Sanger, Illumina, and Nanopore sequencing technologies, highlighting their key operational stages from sample input to data output.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Parasite Barcoding

Successful implementation of sequencing projects for parasite research relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The table below details key solutions used in the featured experiments.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Parasite Sequencing Studies

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Universal 18S rDNA Primers | Primer pairs (e.g., F566/1776R) that anneal to conserved regions of the 18S gene to amplify hypervariable regions (e.g., V4-V9) across diverse eukaryotes [14]. | Broad-spectrum detection and identification of parasitic protists in blood or fecal samples [14] [7]. |

| Blocking Primers (PNA/C3-spacer) | Modified oligonucleotides that bind specifically to host (e.g., mammalian) DNA during PCR and block its amplification, thereby enriching for pathogen sequences in a host-dominated background [14]. | Selective amplification of parasite 18S rDNA from whole blood samples, where host DNA is abundant [14]. |

| Multiplex PCR Assays | Pre-designed sets of primers that simultaneously amplify multiple genomic targets of interest (e.g., drug resistance genes pfcrt, pfdhfr, pfdhps, etc.) in a single reaction [4]. | High-throughput genotyping of antimalarial drug resistance markers in Plasmodium falciparum [4]. |

| Barcodes/Index Adapters | Short, unique DNA sequences ligated to amplicons from individual samples, allowing multiple samples to be pooled and sequenced in a single run while maintaining sample identity during analysis [4] [7]. | Multiplexing up to 96 samples in one NGS run to significantly reduce per-sample costs [4] [31]. |

| Platform-Specific Sequencing Kits | Reagent kits containing enzymes, buffers, and nucleotides optimized for the specific biochemistry of each sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina MiSeq Reagent Kits, Oxford Nanopore Ligation Sequencing Kits). | Performing the sequencing reaction on the respective instrument according to the manufacturer's protocol [4] [14]. |

The evolution from first- to third-generation sequencing technologies has equipped parasitology researchers with a powerful and diverse toolkit. The choice of platform is not a matter of identifying a single "best" technology, but rather of selecting the most appropriate tool based on the specific research question. Sanger sequencing remains the gold standard for validating known variants and sequencing single genes in a limited number of samples. Illumina and other second-generation platforms offer unparalleled throughput, accuracy, and sensitivity for targeted NGS and deep metabarcoding studies, such as large-scale surveillance of drug resistance or complex parasite communities. Oxford Nanopore and other third-generation technologies provide the advantages of portability and long reads, enabling real-time, in-field species identification and simplifying the assembly of complex genomic regions. As costs continue to decrease and workflows become more streamlined, the integration of these complementary technologies will undoubtedly accelerate discoveries in parasite biology, epidemiology, and drug development.

Implementing Barcoding Protocols: From Sample to Sequence

For parasite barcoding research, selecting the appropriate sequencing technology is a critical decision that balances cost, throughput, and analytical requirements. Sanger sequencing, the chain-termination method developed by Frederick Sanger, has been the gold standard for decades for verifying DNA sequences and conducting targeted analyses [6] [21]. In contrast, Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) encompasses several massively parallel sequencing technologies capable of processing millions of fragments simultaneously [33] [37]. This guide provides a detailed, step-by-step breakdown of the Sanger barcoding workflow and objectively compares it with NGS, providing researchers with the data needed to select the optimal method for their specific parasite studies.

Sanger Sequencing vs. NGS: A Technical Comparison for Barcoding

The core difference between these technologies lies in their throughput and methodology. While Sanger sequences a single DNA fragment per reaction, NGS sequences millions of fragments in parallel [33]. The table below summarizes their key characteristics, which directly influence their application in barcoding projects.

Table 1: Key technical differences between Sanger sequencing and NGS

| Feature | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Method | Chain termination using dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs) [21] [38] | Massively parallel sequencing (e.g., Sequencing by Synthesis) [21] |

| Throughput | Low to medium; one fragment per reaction [21] | Extremely high; millions to billions of fragments per run [33] [21] |

| Read Length | Longer reads: 500 - 1000 base pairs [21] | Shorter reads: 50 - 300 base pairs for short-read platforms [21] |

| Cost Efficiency | Low cost per run for a few samples; high cost per base for large projects [21] | High cost per run; very low cost per base for high-volume sequencing [37] [21] |

| Optimal Barcoding Use Case | Targeted confirmation, single-gene barcoding, verifying known loci [6] [21] | Whole-genome sequencing, multiplexed barcoding of many samples, discovering novel variants [33] [20] |

| Variant Detection Sensitivity | Low sensitivity for rare variants (~15-20% limit of detection) [33] | High sensitivity; can detect rare variants down to ~1% allele frequency [33] [21] |

| Data Analysis | Simple; requires basic sequence alignment software [21] | Complex; requires sophisticated bioinformatics for alignment and variant calling [37] [21] |

| Speed per Sample | Fast for a few targets (hours to a day) [21] | Faster for high sample volumes (days for entire runs) [33] |

For parasite barcoding, this means Sanger is ideal for projects focusing on a small number of known genes or for confirming specific variants, such as identifying a suspected parasite species using a standardized barcode locus like COI [39]. NGS is more effective for discovering novel parasites, conducting population-level studies, or when the target is a complex mixture of organisms, as its deep coverage can reveal low-frequency variants missed by Sanger [33] [20].

Step-by-Step Sanger Barcoding Workflow

The Sanger barcoding process involves a series of critical steps from sample collection to data analysis. The following workflow diagram outlines the entire process.

Sanger barcoding workflow from sample to result.

Step 1: Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

The process begins with collecting parasite material, which must be preserved appropriately (e.g., in ethanol) to maintain DNA integrity [39]. The critical goal of DNA extraction is to obtain long, non-degraded strands of DNA [6]. The extraction method must be chosen to match the tissue type; for example, parasites with tough cuticles may require additional lysis steps [39]. The resulting DNA must be assessed for yield and purity using spectrophotometry (A260/280 ratio) to ensure it is of sufficient quality and free of contaminants that could inhibit subsequent reactions [39].

Step 2: PCR Amplification of the Barcode Locus

This step selectively amplifies the standard DNA barcode region using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). For parasites, common barcode loci include:

- COI (Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I): The standard for animal species, including many metazoan parasites [39].

- ITS (Internal Transcribed Spacer): The official barcode for fungi and often used for other groups [20] [39].

Primer design is crucial for success. Primers should be specific to the target parasite taxon to avoid co-amplification of host DNA or non-target organisms [6]. The PCR reaction must be optimized, and controls are essential: a no-template control checks for contamination, while a positive control with known DNA verifies the reaction works [39].

Step 3: Amplicon Purification

After PCR, the product must be purified to remove leftover reagents such as unused primers, dNTPs, and enzyme, which can interfere with the Sanger sequencing reaction [6]. This can be achieved using bead-based, column-based, or enzymatic clean-up kits [6]. The purified DNA is then quantified to ensure it meets the concentration requirements of the sequencing facility or instrument [6].

Step 4: Sanger Sequencing Reaction

The purified PCR product is used as the template in a cycle sequencing reaction. This specialized PCR, also known as chain-termination PCR, uses a single primer and a mixture of normal deoxynucleotides (dNTPs) and fluorescently labeled dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs) [38]. When a ddNTP is incorporated by the DNA polymerase, it terminates the growing DNA chain. This results in a collection of DNA fragments of varying lengths, each ending with a fluorescently labeled ddNTP corresponding to the terminal base [38].

Step 5: Capillary Electrophoresis

The products from the sequencing reaction are injected into a capillary array filled with a polymer matrix. An electrical current is applied, separating the DNA fragments by size [38]. As the shortest fragments pass a laser detector first, the laser excites the fluorescent dye, and the emitted light is captured. The sequence of colors translates directly into the DNA sequence, which is software-output as a chromatogram [38].

Step 6: Data Analysis and Identification

The raw sequence from the chromatogram must undergo quality checks: trimming low-quality base calls from the ends and inspecting for double peaks that might indicate mixed templates or contamination [39]. The clean, reliable sequence is then used for identification by querying public reference databases such as:

- BOLD (Barcode of Life Data Systems): A curated database specifically for DNA barcodes with tools for analysis [39].

- NCBI GenBank: A comprehensive public database that can be searched using the BLAST tool [39].

Identification is made based on the closest match, considering both the percentage of identity and the coverage of the alignment [39].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Sanger Barcoding

A successful Sanger barcoding experiment relies on several key reagents and materials.

Table 2: Key reagents and materials for Sanger barcoding

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolates DNA from parasite tissue. | Must be appropriate for sample type (e.g., tissue, blood, feces). Kits designed for long fragments are preferred [6]. |

| PCR Primers | Specifically amplifies the target barcode locus. | Must be designed for the parasite taxon and barcode gene (e.g., COI, ITS). Should avoid secondary structures and dimer formation [6] [39]. |

| DNA Polymerase | Enzymatically synthesizes new DNA strands during PCR. | Should have high fidelity and robust performance. |

| dNTPs & ddNTPs | The building blocks of DNA (dNTPs) and the chain-terminating nucleotides (ddNTPs) for sequencing. | In Sanger sequencing, ddNTPs are fluorescently labeled for detection [38]. |

| Purification Kit | Removes contaminants and unused reagents from PCR amplicons. | Bead- or column-based methods are common. Essential for a clean sequencing reaction [6]. |

| BigDye Terminators | Proprietary reagent mix containing fluorescent ddNTPs, enzymes, and buffer for the cycle sequencing reaction. | A standard for modern automated Sanger sequencing. |

Comparative Experimental Data: Sanger vs. NGS in Barcoding

The choice between Sanger and NGS is often dictated by the specific goals of the barcoding study. The following table summarizes performance comparisons based on key experimental parameters.

Table 3: Experimental performance comparison for DNA barcoding

| Experimental Parameter | Sanger Sequencing Performance | NGS Performance | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput (Samples/Run) | 1 - 96 samples (single reactions or plate) [40] | Millions of reads, 100s-1000s of samples via multiplexing [20] | NGS can barcode 190+ specimens in 12.5% of a sequencing run [20]. |

| Variant Detection Limit | ~15-20% allele frequency [33] | Can detect variants at 1-5% allele frequency [33] [21] | Crucial for detecting mixed parasite infections. |

| Ability to Resolve Complex Samples | Low; gives a single, consensus sequence. Fails with mixed templates [20] | High; can detect multiple species/strains in a single sample [20] | NGS can detect heteroplasmy, pseudogenes, and co-amplified Wolbachia in insects [20]. |

| Turnaround Time (for low target numbers) | Fast (hours to a day) [21] | Slower for workflow (days) [21] | Sanger is efficient for simple, targeted questions [21]. |

| Cost for Single-Gene Barcoding | Cost-effective for 1-20 targets [33] | Not cost-effective for a low number of targets [33] | Sanger remains the economical choice for focused studies [33]. |

Both Sanger sequencing and NGS are powerful tools for parasite barcoding, but their applications are distinct. Sanger sequencing is the recommended choice for focused, small-scale projects that require high accuracy for single genes, verification of specific variants, or when cost and simplicity are primary concerns. NGS is unequivocally superior for large-scale, discovery-oriented studies that aim to detect novel parasites, resolve complex mixtures of infections, or require high-throughput analysis of hundreds to thousands of samples. By understanding the workflows and comparative data outlined in this guide, researchers can make an informed, strategic decision that optimizes resources and maximizes the success of their parasite barcoding research.

Within parasitology, accurate species identification is fundamental for diagnosis, understanding transmission dynamics, and tracking drug resistance. DNA barcoding, the use of short, standardized genetic markers, has revolutionized this field. While Sanger sequencing long served as the standard for generating DNA barcodes, the advent of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has introduced high-throughput methods that can characterize pathogenic communities from complex samples. Two primary NGS approaches have emerged: metagenomic NGS (mNGS) and targeted NGS (tNGS), also known as amplicon-based NGS. Understanding their comparative advantages, supported by experimental data and tailored to parasite research, is crucial for selecting the appropriate tool in modern laboratories. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two powerful strategies.

Head-to-Head Comparison: mNGS vs. tNGS for Pathogen Detection

Extensive clinical studies, primarily from respiratory infection research, provide robust quantitative data on the performance characteristics of mNGS and tNGS. The table below summarizes key comparative metrics.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of mNGS and tNGS from Clinical Studies

| Performance Metric | Metagenomic NGS (mNGS) | Targeted NGS (tNGS) | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 74.75%–95.08% [41] [42] | 78.64%–96.1% [41] [43] | Lower respiratory tract infections [41] [42] [43] |

| Specificity | 81.82%–90.74% [41] [42] | 85.19%–93.94% [41] [42] | Lower respiratory tract infections [41] [42] |

| Turnaround Time (TAT) | ~20 hours [44] | Shorter than mNGS [44] | Lower respiratory tract infections [44] |

| Cost (Reagent & Labor) | ~$840 per sample [44] | Lower than mNGS [44] | Lower respiratory tract infections [44] |

| Number of Species Identified | 80 species [44] | 71 (capture-based) to 65 (amplification-based) species [44] | Lower respiratory tract infections [44] |

| Key Strength | Detection of rare, novel, or unexpected pathogens; no prior knowledge needed [44] [45] | High sensitivity for targeted taxa; superior for fungal detection (e.g., Pneumocystis jirovecii); identifies resistance genes [44] [41] [42] | Clinical infection diagnosis [44] [41] [42] |

A 2025 meta-analysis of periprosthetic joint infections confirmed these general trends, reporting that mNGS demonstrates higher sensitivity, while tNGS exhibits exceptional specificity [46]. The choice between them often hinges on the diagnostic question: whether to "rule out" with high sensitivity or "rule in" with high specificity.

Experimental Insights and Workflow Comparisons

Key Workflow Steps and Their Differences

The fundamental difference between mNGS and tNGS lies in the wet-lab workflow, which directly influences the data output and analytical requirements. The following diagram illustrates the two parallel processes.

Detailed Methodologies from Cited Experiments

Metagenomic NGS (mNGS) Protocol

A standard mNGS protocol, as used in comparative studies, involves the following steps [44] [42]:

- Sample Processing: 1 mL of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) is used. Human DNA is removed enzymatically using Benzonase and Tween20 to increase the relative proportion of microbial sequences [44].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Total DNA and RNA are co-extracted using a kit such as the QIAamp UCP Pathogen DNA Kit. RNA undergoes reverse transcription to cDNA [44] [42].

- Library Preparation: The DNA and cDNA are fragmented, and sequencing adapters are ligated using a system like the Ovation Ultralow System V2. No amplification of specific targets occurs at this stage [44].

- Sequencing: Libraries are sequenced on platforms like the Illumina NextSeq 550, generating millions of 75-bp single-end reads [44] [42].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Raw reads are quality-filtered (Fastp) and low-complexity sequences are removed.

- Human sequence reads are identified and excluded by alignment to the hg38 reference genome (using BWA or Bowtie2).

- The remaining microbial reads are aligned to a comprehensive microbial genome database using tools like SNAP.

- Statistical thresholds (e.g., Reads Per Million ratio of sample to negative control ≥10) are applied to distinguish true positives from background noise [44] [42].

Targeted NGS (tNGS) Protocol

The tNGS approach, specifically amplification-based, is detailed as follows [44] [42]:

- Sample Processing: BALF samples are liquefied with dithiothreitol. The same sample volume is used as for mNGS to allow direct comparison [42].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Total nucleic acid is extracted and purified using a kit like the MagPure Pathogen DNA/RNA Kit [42].

- Target Enrichment: This is the critical differentiating step. Ultra-multiplex PCR is performed using a pre-designed primer panel (e.g., 198 pathogen-specific primers) to amplify target sequences from bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. Some protocols use two rounds of PCR amplification for optimal enrichment [44] [42].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: The amplified PCR products are purified, and sequencing adapters/barcodes are added. The final library is sequenced on a platform like the Illumina MiniSeq, requiring a lower sequencing depth (~0.1 million reads) due to the enrichment [44].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Data is processed through a vendor-specific pipeline (e.g., KingCreate). After basic quality control, reads are directly aligned to a curated database of the targeted pathogens.

- The enrichment step simplifies analysis, as the data is predominantly composed of sequences from the pre-defined panel, allowing for sensitive detection and sometimes quantification [44].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The successful implementation of NGS barcoding strategies relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table itemizes key solutions required for the workflows described in the experimental protocols.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Barcoding

| Research Reagent | Function | Example Products (from cited studies) |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit | Simultaneous extraction of DNA and RNA from clinical samples, crucial for comprehensive pathogen detection. | QIAamp UCP Pathogen DNA Kit [44], MagPure Pathogen DNA/RNA Kit [42] |

| Host DNA Depletion Reagent | Selectively degrades host nucleic acids (e.g., human DNA) to increase microbial sequencing depth in mNGS. | Benzonase [44] |

| Library Preparation Kit | Prepares nucleic acid fragments for sequencing by adding required adapters. | Ovation Ultralow System V2 [44] |

| Targeted Enrichment Panel | Set of primers/probes designed to amplify and enrich genetic targets from a predefined list of pathogens (for tNGS). | Respiratory Pathogen Detection Kit (198-plex primer panel) [44] [42] |

| Blocking Primers | Oligonucleotides that suppress amplification of host DNA (e.g., mammalian 18S rDNA) during PCR, improving parasite detection in tNGS. | C3 spacer-modified oligos, Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA) oligos [8] |

| Bioinformatics Database | Curated genomic reference database used to assign sequenced reads to specific microbial species. | NCBI RefSeq, GenBank [44] [42] |

Both mNGS and tNGS are powerful successors to Sanger sequencing for parasite barcoding, each with a distinct clinical and research profile. mNGS is a discovery-oriented tool, ideal for detecting rare, novel, or completely unexpected pathogens without prior assumptions, making it invaluable for exploratory studies and difficult-to-diagnose cases [44] [45]. Its main drawbacks are higher cost and longer turnaround time. In contrast, tNGS is a precision tool best suited for sensitive and specific detection of a predefined set of pathogens, often at a lower cost and with a faster result [44] [41]. Its application in detecting fungi and resistance genes is particularly notable [41] [42]. The decision between them is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with the research question, available resources, and the specific clinical or investigative context.

Molecular barcoding has revolutionized parasitology, enabling precise species identification, drug resistance monitoring, and understanding of parasite epidemiology. The choice between Sanger sequencing and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) represents a critical methodological crossroad that directly influences primer design strategies and experimental outcomes. Each approach offers distinct advantages and limitations that must be carefully balanced against research objectives, resources, and the specific parasitic markers being investigated.

The 18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene serves as a cornerstone for eukaryotic parasite identification and phylogenetic studies due to its highly conserved regions interspersed with variable domains. The gp60 gene (also known as SAG60 or Cpgp40/15) is a crucial genetic marker for classifying subtypes and understanding the epidemiology of Cryptosporidium species, with implications for outbreak investigations and transmission dynamics. The K13 propeller gene (Plasmodium falciparum kelch13) has emerged as the primary molecular marker for tracking artemisinin resistance in malaria parasites, making its accurate sequencing vital for global antimicrobial resistance surveillance [4] [45].

This guide systematically compares primer design and performance across Sanger sequencing and NGS platforms, providing researchers with evidence-based recommendations for selecting appropriate methodologies for parasite barcoding research.

Comparative Analysis of Sequencing Platforms

Performance Characteristics of Sanger Sequencing vs. NGS

Table 1: Platform comparison for parasitic marker sequencing

| Parameter | Sanger Sequencing | Targeted NGS (Illumina MiSeq) | Targeted NGS (Ion Torrent PGM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reads per amplicon (mean) | Single sequence chromatogram | 28,886 reads [4] | 1,754 reads [4] |

| Detection of minor alleles | Limited, requires specialized deconvolution [47] | 1% minor allele frequency at 500X coverage [4] | 1% minor allele frequency at 500X coverage [4] |

| Multiplexing capacity | Low (individual reactions) | High (up to 96 samples per run) [4] | High (up to 96 samples per run) [4] |

| Cost efficiency | Lower for small batches | 86% cost reduction vs. Sanger for 96-plex [4] | 86% cost reduction vs. Sanger for 96-plex [4] |

| Variant accuracy | 99.59% [4] | 99.59% [4] | 99.59% [4] |

| Best suited for | Single isolate genotyping, low-complexity samples | Mixed infections, population studies, resistance surveillance [48] [4] | Mixed infections, population studies, resistance surveillance [4] |

Detection Sensitivity Across Methodologies

Table 2: Sensitivity comparison for parasite detection methods

| Method | Relative Sensitivity | Application Example | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopy | Low (10-40% for Entamoeba histolytica) [45] | Routine parasite screening | [45] |

| Conventional PCR (cPCR) + Sanger | Baseline (24% prevalence for Blastocystis) [48] | Single pathogen detection | [48] |

| qPCR + Sanger | Moderate (29% prevalence for Blastocystis) [48] | Quantification with genotyping | [48] |

| NGS (Illumina) | High (100% for known markers at >500X coverage) [4] | Comprehensive resistance profiling | [4] |

| Nanopore NGS | Emerging (detection of 1 parasite/μL blood) [14] | Field applications, unknown pathogen detection | [14] |

Primer Design Considerations by Genetic Marker

18S rRNA Gene Primers

The 18S rRNA gene remains the most widely used genetic marker for broad-spectrum parasite identification and phylogenetic studies. Primer selection must balance taxonomic coverage with specificity to avoid host DNA amplification.

Table 3: 18S rRNA primer selection guide

| Primer Set | Target Region | Amplicon Size | Coverage | Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F566/1776R | V4-V9 | ~1,200 bp | >60% eukaryotes [14] | Broad parasite detection, Nanopore sequencing | Requires host blocking primers for blood samples [14] |

| nu-SSU-1333-5'/nu-SSU-1647-3' (FF390/FR1) | V4-V5 | ~314 bp | 83.4-86.5% fungi [49] | Fungal parasite community analysis | Short length ideal for Illumina [49] |

| P-SSU-316F/GIC758R | V1-V4 | 482 bp | Rumen ciliates [50] | Gastrointestinal protozoa in ruminants | Limited to specific host systems [50] |

| V4 region primers | V4 only | ~400 bp | Highest discriminatory power [51] | Community ecology, biodiversity assessments | Paired-end reads ≥150bp required for genus-level discrimination [51] |

For blood parasites, the F566/1776R primer combination targeting the V4-V9 regions has demonstrated excellent performance when combined with blocking primers to suppress host 18S rDNA amplification. Two blocking strategies have proven effective: a C3 spacer-modified oligo competing with the universal reverse primer and a peptide nucleic acid (PNA) oligo that inhibits polymerase elongation [14].

The design of effective blocking primers requires:

- Sequence specificity to host 18S rRNA gene

- 3'-end modifications (C3 spacer or PNA) to prevent polymerase extension

- Optimal concentration titration to maximize host DNA suppression while minimizing non-specific effects