Resolving Parasitic Cryptic Species Complexes: DNA Barcoding Approaches for Accurate Identification and Research

Cryptic species complexes, comprising morphologically identical but genetically distinct organisms, present a significant challenge in parasitology, impacting disease diagnosis, transmission tracking, and drug development.

Resolving Parasitic Cryptic Species Complexes: DNA Barcoding Approaches for Accurate Identification and Research

Abstract

Cryptic species complexes, comprising morphologically identical but genetically distinct organisms, present a significant challenge in parasitology, impacting disease diagnosis, transmission tracking, and drug development. This article explores the transformative role of DNA barcoding in resolving these complexes. We cover the foundational concepts of species delimitation and the limitations of traditional morphology. The article provides a methodological guide to common genetic markers (e.g., COI, ITS) and analytical pipelines, supported by case studies from helminths and vectors. We address troubleshooting for common pitfalls like hybridization and degraded DNA, and evaluate barcoding against proteomic and morphological methods. Finally, we discuss the validation of barcoding data and its critical implications for controlling parasitic diseases and advancing clinical research.

The Hidden World of Parasites: Unraveling Cryptic Species and Their Clinical Impact

Defining Cryptic Species Complexes in Parasitology

Cryptic species complexes represent groups of closely related species that are morphologically indistinguishable but genetically distinct. In parasitology, the inability to differentiate these species can obscure disease dynamics, drug efficacy, and vector control efforts. DNA barcoding has emerged as a powerful tool for resolving these complexes by utilizing short, standardized genetic markers to provide molecular identifications. This guide compares the performance of DNA barcoding methodologies for identifying cryptic species in parasites and vectors, evaluating experimental protocols, analytical approaches, and practical applications within parasitological research.

Cryptic species are a significant challenge in parasitology, where morphologically similar species may exhibit critical differences in host specificity, pathogenicity, drug resistance, and vector competence. The ecological and medical implications of these unrecognized species are substantial, as they can lead to misleading conclusions in epidemiology, ecology, and disease management strategies [1] [2].

DNA barcoding utilizes sequence variation in a standardized segment of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) mitochondrial gene to enable rapid and reliable species identification [3]. This approach is particularly valuable for parasites, where morphological identification can be extraordinarily difficult due to their small size, complex life cycles, and existence within host tissues [1]. Since its formal proposal in 2003, DNA barcoding has been increasingly applied to parasites and their vectors, demonstrating approximately 94-95% accuracy in specimen identification according to recent assessments [4].

Performance Comparison of DNA Barcoding Approaches

DNA barcoding performance varies across taxonomic groups and methodological approaches. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies applying DNA barcoding to cryptic species identification.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of DNA Barcoding in Various Organism Groups

| Organism Group | Study Focus | Specimens Analyzed | Identification Success Rate | Cryptic Species Detected | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plateau Loach Fishes [3] | Biodiversity assessment | 1,630 specimens | 14 of 24 species reliably identified | 2 cryptic species (Triplophysa robusta sp1, T. minxianensis sp1) | 10 closely related species remained challenging due to rapid differentiation or introgression |

| Korean Curved-Horn Moths [5] | Cryptic diversity detection | 509 specimens, 154 morphospecies | 75.97% (117/154 species) consistent across delimitation methods | 3 species with cryptic diversity | 2.5% genetic divergence threshold effectively differentiated most morphological species |

| Mosquito Species in Singapore [6] | Vector identification | 128 specimens, 45 species | 100% success rate | N/A | Achieved perfect identification despite previous challenges with closely related species |

| Medically Important Parasites/Vectors [4] | Method assessment | Comprehensive review | 94-95% accuracy | N/A | Barcodes available for 43% of 1,403 species, covering more than half of 429 medically important species |

Comparison of Barcode Length Efficacy

The standard DNA barcode consists of a 658-bp fragment of the COI gene. However, shorter "mini-barcodes" (e.g., 175 bp) have been developed for specimens with degraded DNA. Research on apid bees has demonstrated that both full-length and mini-barcodes display similar probabilities of correct identification, making them equivalent for bee identification tasks [7]. This finding is particularly relevant for parasitology, where historical specimens or poorly preserved samples may only yield shorter DNA fragments.

Despite its utility, DNA barcoding faces several challenges. A comprehensive analysis of Hemiptera barcodes found that errors in public databases are not rare, with most attributable to human errors including specimen misidentification, sample confusion, and contamination [8]. Additionally, DNA barcoding may struggle with closely related species that have recently diverged or show evidence of introgression or incomplete lineage sorting [3]. These limitations highlight the importance of integrating DNA barcoding with other data sources rather than relying on it exclusively.

Experimental Protocols for DNA Barcoding in Parasitology

Standard DNA Barcoding Workflow

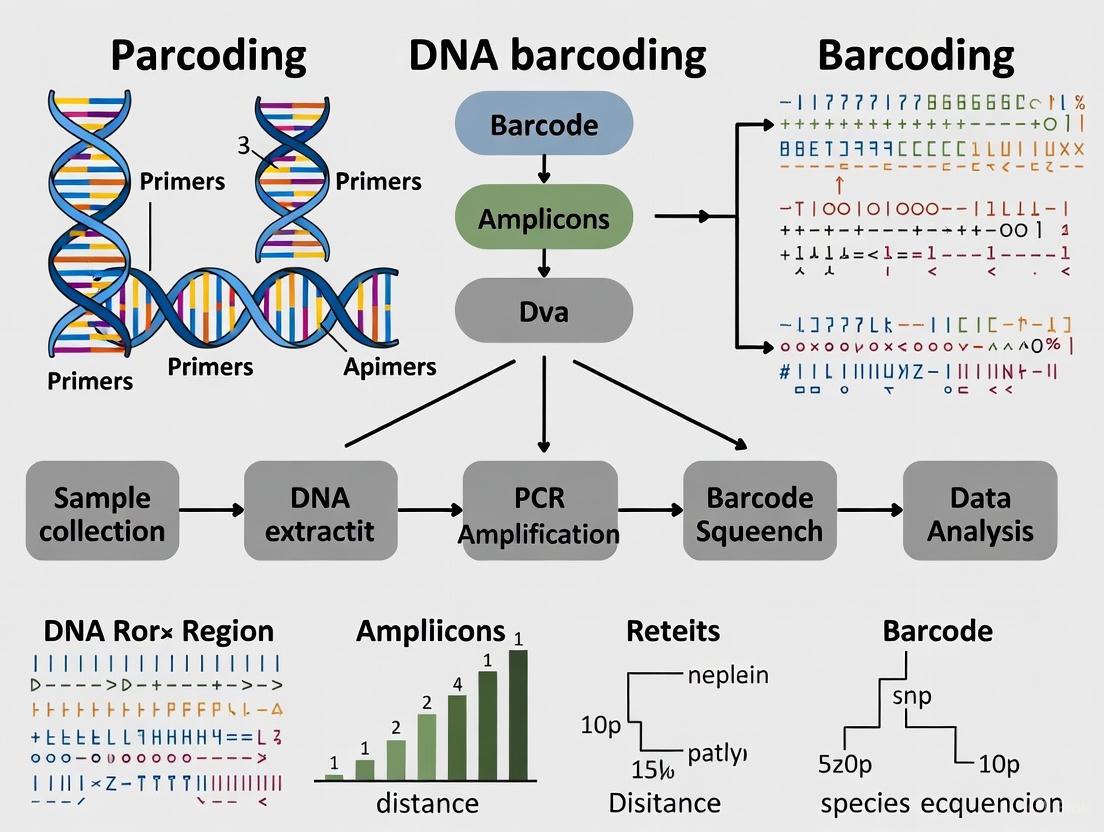

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for DNA barcoding of parasites and vectors, highlighting critical quality control checkpoints:

Detailed Methodological Components

Specimen Collection and Preservation

Proper specimen collection is fundamental to successful DNA barcoding. Researchers should:

- Record detailed geographic information including coordinates and altitude [8]

- Document habitat information, microenvironment, and host associations [8]

- Preserve specimens in 95-100% ethanol or at ultra-low temperatures (-80°C) to prevent DNA degradation

- Create voucher specimens deposited in accessible collections for future reference [6]

DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification

DNA extraction typically utilizes commercial kits (e.g., DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit, Qiagen) on tissue samples from legs, body segments, or entire small specimens [5] [6]. The standard PCR amplification targets the 658-bp barcode region using primers such as:

- LCO1490 (5'-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3') and HCO2198 (5'-TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA-3') [5]

- Alternative primers: BarbeeF and MtD9 for bees [7]

Thermal cycling conditions typically include: initial denaturation (95°C for 2-5 minutes), 35-40 cycles of denaturation (94-95°C for 30-40 seconds), annealing (45-55°C for 30-60 seconds), and extension (72°C for 60 seconds), followed by a final extension (72°C for 5-10 minutes) [5] [6].

Sequence Analysis and Species Delimitation

After sequencing and quality control, several analytical approaches are used for species identification and delimitation:

- Genetic Distance Methods: Calculate Kimura-2-Parameter (K2P) distances and apply thresholds (typically 2-3%)

- Tree-Based Methods: Construct Neighbor-Joining or Maximum Likelihood trees to assess monophyly

- Automated Delimitation Algorithms: Implement methods such as ABGD (Automatic Barcode Gap Discovery), PTP (Poisson Tree Processes), and bPTP (Bayesian PTP) [5]

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

The table below outlines key reagents and materials required for implementing DNA barcoding protocols in parasitology research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for DNA Barcoding

| Reagent/Material | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Nucleic acid purification from specimens | DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) [5] [6] |

| PCR Primers | Amplification of barcode region | LCO1490/HCO2198 [5], BarbeeF/MtD9 [7] |

| PCR Master Mix | DNA amplification reaction | Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, MgCl₂ [5] [6] |

| Agarose Gels | Visualization of PCR products | 1-1.5% gels with DNA staining dyes [6] |

| Sequencing Kit | Determination of nucleotide sequence | BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit [6] |

| Positive Control DNA | Verification of PCR efficiency | Verified specimen with known barcode sequence |

| Reference Databases | Sequence comparison and identification | BOLD (Barcode of Life Data Systems), GenBank [3] [8] |

Discussion and Future Directions

DNA barcoding has substantially advanced the resolution of cryptic species complexes in parasitology, but several considerations merit attention. The technique performs optimally when integrated with morphological data, ecological information, and other genetic markers rather than used in isolation [3] [6]. Future developments will likely focus on multi-locus approaches, environmental DNA (eDNA) applications, and portable sequencing technologies for field-based identification.

The establishment of comprehensive, curated reference libraries remains crucial, as current databases contain barcodes for only approximately 43% of known parasite and vector species [4]. Enhanced collaboration between field parasitologists, taxonomists, and molecular biologists will accelerate progress in documenting and understanding cryptic diversity in parasites. As these resources grow, DNA barcoding will increasingly illuminate the hidden diversity within parasite species complexes, ultimately strengthening disease management and conservation efforts.

DNA barcoding provides parasitologists with a powerful tool for discriminating cryptic species complexes that defy morphological diagnosis. When implemented with rigorous protocols and appropriate analytical frameworks, this approach delivers identification accuracy exceeding 90% for many parasite and vector groups. The continuing expansion of reference databases, refinement of mini-barcode applications for degraded materials, and integration with complementary data sources will further enhance the utility of DNA barcoding in revealing the true diversity of parasitic organisms and addressing the medical and ecological challenges they present.

Limitations of Morphological Identification for Parasite Diagnosis

The accurate identification of parasites is a cornerstone of effective disease control, yet traditional methods that rely on morphological characteristics face significant and growing challenges. For decades, microscopic examination of parasite eggs, larvae, and adults has served as the gold standard in diagnostic and clinical settings [9]. This approach, while cost-effective and providing rapid results, requires highly trained personnel and struggles with increasing limitations, particularly when dealing with cryptic species complexes and specimens with overlapping morphological features [9] [10]. The emergence of molecular tools, especially DNA barcoding, has revealed substantial deficiencies in morphology-based identification systems, prompting a critical re-evaluation of traditional parasitological diagnostics. This guide examines the specific limitations of morphological identification for parasite diagnosis within the broader context of DNA barcoding's capacity to resolve cryptic species complexes, providing researchers and drug development professionals with comparative data and methodologies to enhance diagnostic accuracy.

Comparative Analysis: Morphological vs. Molecular Identification

Fundamental Limitations of Morphological Approaches

Morphological identification of parasites faces several intrinsic constraints that impact diagnostic accuracy and reliability. Operator dependence represents a primary limitation, as the technique requires extensive training and expertise, with veteran parasitologists still facing significant challenges when distinguishing closely related taxa that share visual characteristics [9]. This problem is exacerbated by morphological conservation, where phylogenetically distinct species exhibit nearly identical physical traits, particularly in egg and larval forms where diagnostic characters are limited [9].

The subjectivity in interpretation further complicates morphological diagnosis, as degradation during preservation can alter key identifying features. A study evaluating preservation methods found that ethanol storage caused cuticle shrinking, puckering, and increased opacity in nematode larvae, while formalin preservation led to internal structures being obscured by bubbles within the body cavity [9]. These preservation artifacts frequently necessitate broad taxonomic assignments (e.g., "strongyle-type" eggs) that mask true biological diversity and complicate treatment decisions [9].

Quantitative Comparisons of Diagnostic Accuracy

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Morphological versus Molecular Identification Across Parasite Taxa

| Parasite Group | Morphological Identification Challenge | Molecular Resolution | Key Genetic Marker(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angiostrongylus spp. | Significant misidentification between A. cantonensis and A. malaysiensis due to overlapping morphological characters | Nuclear ITS2 region provided reliable species discrimination, revealing 8.2% hybrid forms | ITS2 (Nuclear), cytb (Mitochondrial) | [10] |

| Toxocara cati complex | Historically treated as a single species | DNA barcoding revealed 5 distinct clades with 6.68-10.84% genetic divergence in cox1 | cox1 | [11] |

| Gastrointestinal strongyles | Broad categorization as "strongyle-type" eggs due to morphological similarity | Multi-marker approaches enable species-level identification from eggs | ITS1, ITS2, COI | [12] [9] |

| Thrips species | Cryptic diversity undetectable morphologically; 1% known as virus vectors | 14 morphospecies contained more than one Molecular Operational Taxonomic Unit (MOTU) | mtCOI | [13] |

Table 2: Impact of Preservation Method on Morphological Identification Quality

| Preservation Medium | Morphotype Diversity Recovery | Larval Preservation Quality | Egg Preservation Quality | Suitability for Molecular Analysis | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10% Formalin | Higher morphotype identification rate | Significantly better preserved | No significant difference from ethanol | Poor (causes DNA fragmentation) | [9] |

| 96% Ethanol | Lower morphotype diversity observed | Moderate preservation with cuticle degradation | No significant difference from formalin | Excellent (maintains stable DNA) | [9] |

Molecular Solutions: DNA Barcoding and Beyond

DNA Barcoding Fundamentals and Workflow

DNA barcoding provides a precise method for identifying species by assigning a unique genetic 'barcode' to each species using short, standardized genome regions [14]. This approach is particularly valuable for distinguishing closely related species that may look similar morphologically and only requires a small tissue sample for analysis [14]. The technique has demonstrated particular utility in resolving species complexes where morphological identification fails, such as in the Toxocara cati complex, where DNA barcoding revealed five distinct clades corresponding to different host species [11].

The following diagram illustrates the comparative workflow between traditional morphological identification and integrated molecular approaches:

Essential Molecular Markers for Parasite Identification

Different genetic markers offer varying levels of resolution for parasite identification, with selection dependent on the taxonomic group and diagnostic requirements:

- Mitochondrial markers: Cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) serves as the standard barcode region for many metazoan parasites, providing strong species-level discrimination [15]. Cytochrome b (cytb) offers alternative resolution for specific taxonomic groups [10].

- Nuclear ribosomal markers: Internal Transcribed Spacer regions (ITS1, ITS2) provide reliable species identification, particularly for nematodes, with the advantage of detecting hybridization events through heterozygous sites [10].

- Multi-locus approaches: Combining chloroplast (rbcL, matK, trnH-psbA) and nuclear (ITS2) markers enhances resolution for complex taxonomic groups, as demonstrated in plant parasite identification [14].

Experimental Protocols for Molecular Identification

DNA Barcoding Standard Protocol

The fundamental DNA barcoding protocol involves several standardized steps:

- DNA Extraction: Using commercial kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA Mini Kit) with non-destructive methods when voucher specimens are valuable [13].

- PCR Amplification: Employing universal primers for target barcode regions (e.g., LCO-HCO for COI) with cycling parameters optimized for parasite taxa [13].

- Sequencing and Analysis: Bidirectional Sanger sequencing followed by sequence validation using Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) homology analysis and phylogenetic methods [14].

- Species Delimitation: Applying multiple algorithms (Barcode Index Numbers (BIN), Assemble Species by Automatic Partitioning (ASAP), Poisson Tree Processes (PTP)) to establish molecular operational taxonomic units (MOTUs) [11] [13].

Advanced Molecular Detection Systems

Integrated platforms like the Parasite Genome Identification Platform (PGIP) leverage metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) for comprehensive parasite detection [16]. The PGIP workflow incorporates:

- Host DNA depletion using alignment tools (Bowtie2) with sensitivity parameters

- K-mer based classification against curated reference databases (Kraken2)

- Metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) reconstruction via probabilistic clustering tools (MetaBAT) [16]

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Parasite Molecular Identification

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Example | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| QIAGEN DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit | DNA extraction from various sample types | High-quality genomic DNA from ethanol-preserved specimens | Non-destructive protocols allow voucher specimen preservation [13] |

| Universal PCR Primers (LCO-HCO) | Amplification of standard barcode region (COI) | Broad-spectrum parasite barcoding | 648 bp 5' region of COI; annealing ~49°C [13] |

| Species-Specific qPCR Primers | Quantitative detection of target species | Differentiating A. cantonensis and A. malaysiensis in clinical samples | SYBR Green chemistry with cytb gene target [10] |

| BOLD Systems Database | Reference database for barcode sequences | Species identification via BIN assignment | Curated database with quality control; requires specific metadata [15] |

| NCBI GenBank | Comprehensive sequence repository | BLAST homology analysis for identification | Larger but less curated than BOLD; potential quality issues [15] |

| Trimmomatic/FastQC | Quality control of raw sequencing data | Pre-processing of NGS data for metagenomic identification | Adapter removal, quality filtering, and visualization [16] |

Database Reliability and Quality Considerations

The accuracy of molecular identification depends heavily on reference database quality and coverage. Recent evaluations of cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) barcode records for marine metazoans revealed significant concerns in both the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) and Barcode of Life Data System (BOLD) databases [15]. NCBI exhibited higher barcode coverage but lower sequence quality compared to BOLD, with issues including over- or under-represented species, short sequences, ambiguous nucleotides, incomplete taxonomic information, conflict records, high intraspecific distances, and low inter-specific distances [15]. The Barcode Index Number (BIN) system in BOLD demonstrated potential for identifying and addressing problematic records, highlighting the benefits of curated databases for reliable species identification [15].

Morphological identification of parasites presents significant limitations in sensitivity, specificity, and reliability, particularly for cryptic species complexes, environmentally degraded samples, and taxa with overlapping morphological characters. DNA barcoding and related molecular methods provide powerful complementary tools that overcome these limitations through genetic discrimination at species and sub-species levels. The integration of morphological and molecular approaches, supported by curated reference databases and standardized protocols, offers the most robust framework for contemporary parasitological diagnosis, biodiversity assessment, and drug development targeting specific parasite species and strains. As molecular technologies become increasingly accessible and reference databases expand, the parasitological research community must continue to develop integrated diagnostic workflows that leverage the respective strengths of both morphological and molecular identification methods.

The Fundamental Principles of DNA Barcoding for Species Delimitation

DNA barcoding has emerged as a transformative tool for species delimitation, addressing critical challenges in biodiversity research and parasitology. This guide examines the fundamental principles of DNA barcoding, focusing on its capacity to resolve cryptic species complexes that defy traditional morphological identification. We compare the performance of single-locus barcoding against multi-locus approaches and integrate experimental data demonstrating applications in parasite research. The technical protocols, reagent specifications, and analytical frameworks presented herein provide researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for implementing DNA barcoding to uncover hidden diversity within parasite groups, with significant implications for disease control and drug development.

Core Principles and Genetic Targets of DNA Barcoding

DNA barcoding constitutes a standardized method for species identification and discovery using short, reproducible DNA sequences from conserved genomic regions. The methodology addresses the Linnaean shortfall—the discrepancy between described species and actual biodiversity—particularly critical for parasites where morphological distinctions are often subtle or cryptic [17]. The foundational principle leverages sequence variation within a universal marker that demonstrates appreciable divergence between species yet relative conservation within species.

The cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene of the mitochondrial genome serves as the primary barcode region for animals, including many parasite groups. This 658-base pair region, often called the Folmer region, provides optimal characteristics for barcoding: conserved primer binding sites for reliable amplification flanking a variable sequence that accumulates species-level differences [17] [18]. The efficiency of COI stems from maternal inheritance, absence of introns, and limited recombination, providing clear phylogenetic signal across diverse taxa.

For parasitic organisms, DNA barcoding has proven particularly valuable in resolving species complexes—groups of morphologically similar but genetically distinct species that may exhibit different host specificities, pathological effects, or drug susceptibilities. The methodology enables researchers to document diversity at unprecedented scales, with DNA sequence variation providing the initial hypothesis of species boundaries that can be tested with additional evidence including morphology, ecology, and geography [17].

Performance Comparison: Assessing Barcoding Efficacy Across Parasite Taxa

Quantitative Delimitation Success Across Study Systems

Table 1: DNA Barcoding Performance Metrics Across Parasite and Vector Groups

| Organism Group | Genetic Marker | Intraspecific Divergence (%) | Interspecific Divergence (%) | Identification Success Rate (%) | Cryptic Lineages Detected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culicoides biting midges [18] | COI | 0.00–0.97 (mean: 0.009) | 4.5–20.1 (mean: 13.3) | 94.7–97.4 | 8 larval species identified |

| Toxocara cati complex [19] | COI | Not specified | 6.68–10.84 (domestic vs. wild felids) | 100% species delimitation | 5 distinct clades |

| General arthropods [17] | COI | Typically <2% | Typically >2.2% threshold | Varies with taxonomic group | Massive scale predicted |

Methodological Comparison: Single vs. Multi-Locus Approaches

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of DNA Barcoding Methodologies

| Approach | Genetic Data | Strengths | Limitations | Ideal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional morphology | None | Direct observation; No specialized equipment | Limited for cryptic species; Requires expertise | Initial surveys; Well-differentiated taxa |

| Single-locus barcoding | COI (animals) | Standardized; Cost-effective; Large reference databases | Limited phylogenetic resolution; Mitochondrial introgression | Large-scale biodiversity surveys; Rapid identification |

| Multi-locus barcoding | COI + nuclear markers | Improved resolution; Detects hybridization | Higher cost; Complex analysis | Cryptic species complexes; Taxonomic revisions |

| Barcode Index Number (BIN) [17] | COI clusters | Automated delimitation; Handles large datasets | Proprietary algorithm; 2.2% threshold may not fit all taxa | Biodiversity informatics; Community ecology |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard DNA Barcoding Protocol for Parasite Specimens

Specimen Collection and Preservation: Proper handling begins with field collection of parasite specimens using host necropsy or established sampling methods. Immediate preservation in 95-100% ethanol is critical for DNA integrity, with morphological vouchers preserved similarly for subsequent verification. Detailed collection metadata including host species, geographic location, and collection date must be documented [18].

DNA Extraction and Amplification: Tissue samples from individual specimens undergo DNA extraction using commercial kits (e.g., DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit). The standard COI barcode region is amplified using universal primers LCO1490 and HCO2198, generating a 658-bp amplicon via PCR with standard cycling conditions: initial denaturation at 94°C for 2 minutes; 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 50-52°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 1 minute; final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes [18] [19].

Sequencing and Data Analysis: PCR products are sequenced bidirectionally using Sanger sequencing or increasingly through high-throughput platforms (Oxford Nanopore, PacBio). Contig assembly generates consensus sequences, which are aligned against reference databases. The Barcode of Life Data System (BOLD) provides an integrated platform for data management, analysis, and publication [17] [18].

Species Delimitation Using Barcode Gap Analysis

The core analytical approach identifies the "barcode gap"—the separation between maximum intraspecific variation and minimum interspecific divergence. Genetic distances (typically Kimura 2-parameter model) are calculated between all sequences. Specimens are grouped into Molecular Operational Taxonomic Units (MOTUs) using clustering algorithms like the BOLD's Refined Single Linkage (RESL), which employs a 2.2% divergence threshold to create Barcode Index Numbers (BINs) as putative species proxies [17].

The workflow below illustrates the standard DNA barcoding process for species delimitation:

Case Study: Resolving the Toxocara cati Complex

A recent investigation of the parasite Toxocara cati infecting domestic and wild felids demonstrates barcoding's power to uncover cryptic species complexes. Researchers sequenced the COI barcode from specimens collected across different hosts and geographical regions. Phylogenetic analysis revealed five distinct clades with sequence divergences of 6.68–10.84% between parasites from domestic cats versus wild felids—differences substantial enough to suggest separate species status rather than host variants [19].

The Assemble Species by Automatic Partitioning (ASAP) analysis supported the species status of these clades, illustrating how barcoding can prompt taxonomic revisions in parasite groups with implications for understanding host specificity, transmission patterns, and potential zoonotic risk [19].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Barcoding Experiments

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Specification | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit | DNA extraction | Silica-membrane technology; Handles minute specimens | Optimal for parasite tissue with inhibitor removal |

| Folmer Primers (LCO1490/HCO2198) | COI amplification | Universal primers for metazoans; 658-bp product | Standardized barcoding across animal taxa |

| GoTaq G2 Flexi DNA Polymerase | PCR amplification | Robust amplification; Buffer optimization | Reliable performance with diverse template quality |

| BigDye Terminator v3.1 | Sanger sequencing | Fluorescent dye-terminator chemistry | Bidirectional sequencing for consensus building |

| MinION Sequencer | Portable sequencing | Oxford Nanopore technology; Real-time data | Field-deployable for rapid biodiversity assessment |

Technological Advancements and Future Directions

DNA barcoding is transitioning from Sanger sequencing to high-throughput sequencing platforms that dramatically reduce costs and increase throughput. Oxford Nanopore's MinION and Pacific Biosciences platforms enable massive parallel sequencing, with costs reduced by up to two orders of magnitude compared to traditional methods [17]. This accessibility is accelerating the discovery of cryptic diversity, particularly in arthropods which comprise approximately 85% of animal diversity with an estimated 10 million species awaiting documentation [17].

The Barcode of Life Data System (BOLD) represents the central informatics platform for barcoding data, hosting over 16 million barcode sequences representing more than 376,000 described species alongside countless unidentified lineages [17]. For parasitic organisms, this expanding reference library enables more accurate identification of vectors, intermediate hosts, and the parasites themselves, providing critical data for understanding disease transmission cycles.

Advanced algorithms for species delimitation continue to evolve, with the Barcode Index Number (BIN) system providing automated grouping of sequences into putative species. However, concerns remain about fully automated approaches, emphasizing the need for integrative taxonomy that combines molecular data with other lines of evidence [17]. As DNA barcoding reveals unprecedented cryptic diversity, the taxonomic impediment—the limited global capacity to formally describe species—represents a significant challenge, particularly for parasites where accurate identification directly impacts public health interventions [17].

Implications for Parasite Research and Drug Development

For researchers studying parasitic diseases, DNA barcoding provides critical tools for identifying cryptic species complexes that may exhibit different transmission dynamics, host specificities, or drug susceptibilities. The accurate delimitation of parasite species directly impacts diagnostic assay development, drug target identification, and vaccine development by ensuring biological materials are correctly identified [19].

The application of barcoding to larval stages and immature forms—as demonstrated in Culicoides studies—enables researchers to connect life history stages and understand complete transmission cycles [18]. Similarly, the identification of cryptic species within morphologically similar parasites, as seen in Toxocara, highlights potential differences in zoonotic potential that must be considered in control programs [19].

As DNA barcoding technologies continue to evolve toward greater accessibility and throughput, their integration with complementary approaches like morphology, ecology, and genomics will provide increasingly robust frameworks for understanding parasite diversity and implementing targeted interventions against parasitic diseases.

Implications for Disease Epidemiology and Zoonotic Potential

DNA barcoding has revolutionized parasitology by providing researchers with powerful tools to accurately identify species, resolve cryptic species complexes, and trace transmission pathways of zoonotic diseases. Cryptic species complexes—groups of morphologically similar but genetically distinct organisms—represent a significant challenge in disease epidemiology, as different sibling species may exhibit varying vector competencies, host preferences, and pathogenic potentials. The application of DNA barcoding techniques has become indispensable for understanding the true diversity of parasites and their vectors, enabling more precise assessment of zoonotic risks and leading to more effective disease control strategies. This guide compares the performance of leading DNA barcoding approaches and their critical role in elucidating parasite transmission dynamics in an era of emerging infectious diseases.

Experimental Protocols in Parasite DNA Barcoding

Protocol 1: Cryptic Vector Species Identification Using COI Barcoding

This protocol was utilized for identifying cryptic species within Culicoides biting midges, potential vectors of Leishmania parasites in southern Thailand [20].

- Sample Collection: Female Culicoides were collected from leishmaniasis-affected areas in southern Thailand using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) ultraviolet light traps [20].

- Morphological Identification: Specimens were preliminarily sorted into species based on wing spot patterns [20].

- DNA Extraction and Amplification: Genomic DNA was extracted from individual midges. The cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene region of mitochondrial DNA was amplified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with specific primers [20].

- Sequencing and Analysis: PCR products were sequenced via Sanger sequencing. The resulting DNA barcodes were compared against reference databases like the Barcode of Life Data System (BOLD) and analyzed with the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) for species identification [20].

- Species Delimitation: To resolve cryptic species complexes, sequences were analyzed using three different species delimitation methods: Assemble Species by Automatic Partitioning (ASAP), Templeton, Crandall, and Sing (TCS) algorithm, and Poisson Tree Processes (PTP). These analyses group sequences into Molecular Operational Taxonomic Units (MOTUs), providing a hypothesis of species boundaries [20].

Protocol 2: Broad-Spectrum Blood Parasite Detection Using 18S rDNA Barcoding

This protocol demonstrates a targeted next-generation sequencing approach for comprehensive blood parasite detection, designed for use on portable nanopore sequencers [21] [22].

- Primer Design: Universal primers (F566 and 1776R) were selected to amplify a ~1,200 base pair region of the 18S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) gene, spanning the V4 to V9 variable regions. This longer barcode provides superior species-level resolution compared to shorter fragments, which is crucial for accurate identification on error-prone sequencing platforms [21] [22].

- Host DNA Suppression: To overcome the challenge of overwhelming host DNA in blood samples, two blocking primers were employed:

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: PCR is performed with the universal and blocking primers. The resulting amplicons are prepared into sequencing libraries and run on a portable nanopore sequencer [21] [22].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Sequences are classified using alignment tools like BLAST or ribosomal database project (RDP) classifiers against curated pathogen databases for species identification [21] [22].

The workflow below illustrates the key steps involved in a DNA barcoding study for vector-borne parasite detection.

Performance Comparison of DNA Barcoding Methodologies

The table below summarizes the performance and applications of two primary DNA barcoding approaches for parasitological research.

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Barcoding Methodologies for Parasite Research

| Feature | COI Barcoding (Sanger Sequencing) | 18S rDNA Barcoding (Nanopore NGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Species identification and delimitation of arthropod vectors and metazoan parasites [20]. | Broad-spectrum detection of eukaryotic blood parasites (e.g., Plasmodium, Trypanosoma, Babesia) [21] [22]. |

| Target Gene | Mitochondrial Cytochrome c Oxidase Subunit I (COI) [20]. | Nuclear 18S ribosomal RNA gene (V4–V9 regions) [21] [22]. |

| Sequencing Platform | Sanger sequencing [20]. | Portable nanopore sequencing [21] [22]. |

| Key Advantage | High resolution for distinguishing between metazoan species, including cryptic complexes [20]. | Comprehensive detection of diverse parasite taxa in a single assay, even without prior knowledge of pathogens present [21] [22]. |

| Typical Workflow | Individual DNA extraction, PCR, and sequencing [20]. | Bulk DNA extraction, PCR with host-blocking primers, and high-throughput sequencing [21] [22]. |

| Sensitivity | Effective for identifying the vector species from which DNA is extracted [20]. | High sensitivity; detected Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense in spiked human blood at 1 parasite/μL [21] [22]. |

| Data Output | A single DNA barcode sequence per PCR reaction [20]. | Thousands of sequences per run, enabling detection of multiple parasites and co-infections [21] [22]. |

Key Findings and Epidemiological Implications

Resolving Cryptic Vector Complexes

The integration of DNA barcoding with morphological identification has been pivotal in uncovering hidden diversity. A study on Culicoides biting midges in Thailand identified 25 morphologically distinct species but used DNA barcoding and species delimitation analyses (ASAP, TCS, PTP) to reveal an additional six cryptic species complexes within C. actoni, C. orientalis, C. huffi, C. palpifer, C. clavipalpis, and C. jacobsoni [20]. This refined resolution is critical for vector control, as it allows scientists to investigate whether specific cryptic species are more competent vectors, thereby refining risk maps and intervention strategies.

Tracking Zoonotic Pathogens in Reservoir Hosts

Metabarcoding, an extension of DNA barcoding applied to complex samples, is powerful for screening potential zoonotic risks in wildlife reservoirs. Research on dog feces in Seoul, South Korea, revealed significant differences in the eukaryotic pathogen communities between pet and stray dogs. Stray dogs carried a significantly higher prevalence of putative eukaryotic pathogens like Giardia and Pentatrichomonas, highlighting their role as reservoirs and the heightened zoonotic risk in urban environments [23] [24]. Similarly, a study of urban birds in Madrid detected 23 genera of eukaryotic parasites, including six with zoonotic potential such as Cryptococcus fungi and Cryptosporidium protists, pinpointing specific bird species as vectors and reservoirs [25].

Detecting Novel Transmission Cycles

Perhaps one of the most significant contributions of DNA barcoding is its ability to incriminate novel vectors in disease transmission. Traditional knowledge held that leishmaniasis is transmitted exclusively by sand flies. However, DNA-based detection confirmed the presence of Leishmania martiniquensis and L. orientalis DNA in several species of Culicoides biting midges collected in southern Thailand [20]. This finding was supported by the detection of mixed blood meals (from humans, cows, dogs, and chickens) in these midges, providing compelling evidence for their potential role in a previously unrecognized transmission cycle of leishmaniasis [20].

The table below summarizes quantitative findings from recent studies that utilized DNA barcoding to assess zoonotic parasite presence.

Table 2: Selected Epidemiological Findings Enabled by DNA Barcoding

| Host / Vector | Pathogen Detected | Key Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culicoides biting midges (Thailand) | Leishmania martiniquensis, L. orientalis | 6.42% of midges tested positive for Leishmania DNA; sympatric infection of both species found. | [20] |

| Stray Dogs (Seoul, S. Korea) | Giardia, Pentatrichomonas | Prevalence of these eukaryotic pathogens was significantly higher in stray dogs than in pet dogs. | [23] [24] |

| Urban-Associated Birds (Madrid, Spain) | Cryptosporidium spp. | Detected in 10% of White Stork and Lesser Black-backed Gull faecal samples. | [25] |

| Urban Birds and Bats (Madrid, Spain) | Campylobacter spp., Listeria spp. | Potentially zoonotic bacteria were found in faeces of nearly all studied urban bird species. | [26] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table details key reagents and materials critical for conducting DNA barcoding experiments in parasitology.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for DNA Barcoding in Parasite Research

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CDC UV Light Trap | Standardized collection of hematophagous insect vectors. | Collecting Culicoides biting midges from leishmaniasis-endemic areas [20]. |

| Universal COI Primers | Amplify the standard DNA barcode region from a wide range of metazoans. | Identifying and delimiting species of insect vectors [20]. |

| Universal 18S rDNA Primers (F566/1776R) | Amplify a broad-range eukaryotic barcode from various pathogens. | Detecting apicomplexan and trypanosomatid parasites in blood [21] [22]. |

| Host-Blocking Primers (C3, PNA) | Selectively inhibit the amplification of host DNA during PCR. | Enriching parasite DNA in blood samples for sensitive detection with nanopore sequencing [21] [22]. |

| Barcode of Life Data System (BOLD) | Integrated database for collating, managing, and analyzing DNA barcode records. | Identifying specimens by comparing unknown sequences to a reference library [20]. |

The accurate identification of insect vectors is a cornerstone of effective disease control. For many vector species, cryptic species complexes—groups of morphologically similar but genetically distinct species—can complicate this process, leading to an incomplete understanding of transmission dynamics [27]. DNA barcoding, which uses a short, standardized genetic marker from the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) gene, has become an indispensable tool for resolving these complexes [28]. This case study examines how the application of DNA barcoding to Culicoides biting midges in Thailand has unveiled a hidden layer of cryptic diversity, simultaneously transforming our understanding of the transmission cycle of Leishmania martiniquensis and L. orientalis, emerging pathogens causing human leishmaniasis [20] [29]. This integrative taxonomic approach provides a model for resolving cryptic species complexes in parasite research, demonstrating that vector diversity is a critical factor in the risk of zoonotic transmission.

Cryptic Diversity inCulicoidesBiting Midges: DNA Barcoding Reveals Hidden Species

Traditional identification of Culicoides species relies heavily on morphological characteristics, particularly wing spot patterns. However, this method is often insufficient for discriminating between cryptic species. In southern Thailand, an integrative approach combining morphology with DNA barcoding of the COI gene was applied to 875 Culicoides specimens, morphologically identifying them into 25 species [20]. The DNA barcoding achieved an 82.20% success rate for identification, but more importantly, it exposed significant hidden diversity.

Species delimitation analyses using ASAP, TCS, and PTP methods categorized six morphospecies into cryptic species complexes: Culicoides actoni, C. orientalis, C. huffi, C. palpifer, C. clavipalpis, and C. jacobsoni [20]. This discovery indicates that the actual species richness of Culicoides in the region is higher than previously recognized, which has profound implications for vector incrimination and monitoring. The use of COI for DNA barcoding, while powerful, is not without challenges; its reliability depends on a well-curated reference database, and the presence of a "barcoding gap" where intraspecific genetic variation is markedly less than interspecific variation [30] [28].

Table 1: Cryptic Culicoides Species Complexes Identified via DNA Barcoding in Southern Thailand

| Morphospecies | Subgenus/Species Group | Evidence for Cryptic Diversity |

|---|---|---|

| Culicoides actoni | Avaritia | Confirmed by multiple species delimitation methods (ASAP, TCS, PTP) [20] |

| Culicoides orientalis | Avaritia | Confirmed by multiple species delimitation methods (ASAP, TCS, PTP) [20] |

| Culicoides huffi | N/A | Confirmed by multiple species delimitation methods (ASAP, TCS, PTP) [20] |

| Culicoides palpifer | N/A | Confirmed by multiple species delimitation methods (ASAP, TCS, PTP) [20] |

| Culicoides clavipalpis | Clavipalpis Group | Confirmed by multiple species delimitation methods (ASAP, TCS, PTP) [20] |

| Culicoides jacobsoni | Hoffmania | Confirmed by multiple species delimitation methods (ASAP, TCS, PTP) [20] |

3Culicoidesas Potential Vectors ofLeishmaniaand Other Trypanosomatids

The paradigm of leishmaniasis transmission has been challenged with the incrimination of biting midges as potential vectors for species of the Leishmania subgenus Mundinia. Molecular screening of Culicoides populations in endemic areas of Thailand has provided compelling evidence supporting this hypothesis.

In southern Thailand, 6.42% of collected Culicoides tested positive for Leishmania DNA. The study revealed a sympatric circulation of both L. martiniquensis and L. orientalis in several Culicoides species in the Ron Phibun and Phunphin districts, while only L. orientalis was detected in the Sichon district [20]. This geographic variation in parasite distribution underscores the complexity of transmission landscapes. A separate study in northern Thailand found a 2.83% infection rate of L. martiniquensis in C. mahasarakhamense [31]. Perhaps the most conclusive evidence comes from a study of natural infections, which visualized various forms of Leishmania promastigotes in the foregut of wild-caught C. peregrinus in the absence of bloodmeal, indicating established infections rather than simple passage of a recent bloodmeal. The infection rate in these flies was between 2% and 6% [32].

Beyond Leishmania, other trypanosomatids have been detected in Culicoides. These include Trypanosoma sp. (closely related to avian trypanosomes) in C. huffi [31] and novel species of Crithidia, a monoxenous trypanosomatid, found co-infecting midges alongside L. martiniquensis [20] [32]. Blood meal analysis from engorged Culicoides in Ron Phibun showed they feed on cows, dogs, chickens, and humans, demonstrating their opportunistic feeding behavior and potential as bridge vectors between animal reservoirs and human populations [20].

Table 2: Detection of Pathogens in Culicoides Biting Midges in Thailand

| Pathogen | Detection Rate | Key Culicoides Species | Location | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leishmania martiniquensis & L. orientalis | 6.42% (of total midges) | Multiple species | Southern Thailand | [20] |

| Leishmania martiniquensis | 2.83% (in C. mahasarakhamense) | C. mahasarakhamense | Northern Thailand | [31] |

| Leishmania martiniquensis (natural infection) | 2% - 6% (in C. peregrinus) | C. peregrinus | Southern Thailand | [32] |

| Trypanosoma sp. (avian) | Detected in 1 sample | C. huffi | Northern Thailand | [31] |

| Crithidia spp. | Detected | C. peregrinus, C. subgenus Trithecoides | Southern Thailand | [20] [32] |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Vector and Pathogen Identification

The research findings cited in this case study are underpinned by rigorous and standardized experimental protocols. The following workflows detail the key methodologies for vector collection, identification, and pathogen detection.

Field Collection and Morphological Identification

- Collection Method: Culicoides biting midges are typically collected using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) ultraviolet (UV) light traps placed in areas of known leishmaniasis cases or near animal sheds [20] [33]. UV LED traps have been shown to outperform green LED traps in terms of the number of individuals collected [33].

- Specimen Sorting: Collected insects are anesthetized and sorted under a stereomicroscope. Female Culicoides are separated for analysis as they are the hematophagous life stage.

- Morphological Identification: Species are preliminarily identified based on key morphological characteristics, with wing spot patterns being a primary diagnostic feature [20]. Specimens are often mounted on microscope slides for detailed examination.

DNA Barcoding and Integrative Taxonomy

- DNA Extraction: Genomic DNA is extracted from individual Culicoides specimens, typically from the whole body or a part of it, such as the thorax.

- PCR Amplification: The cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) barcode region of mitochondrial DNA is amplified using universal primers such as LCO1490 and HCO2198 [20] [33].

- Sequencing and Analysis: PCR products are sequenced via Sanger sequencing. The resulting sequences are curated and compared against reference databases like the Barcode of Life Data System (BOLD) and GenBank using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) [20].

- Species Delimitation: To objectively classify sequences into molecular operational taxonomic units (MOTUs) and detect cryptic species, multiple analytical methods are employed, including:

- ASAP: Assemble Species by Automatic Partitioning.

- TCS: Templeton, Crandall, and Sing haplotype network analysis.

- PTP: Poisson Tree Processes model [20].

Pathogen Detection and Blood Meal Analysis

- Leishmania/Trypanosomatid Detection: Total DNA from individual midges is used for PCR. Detection of Leishmania and other trypanosomatids often targets the internal transcribed spacer 1 (ITS1) region and the small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) gene [20] [31]. Positive PCR products are sequenced for species and haplotype identification.

- Blood Meal Analysis: The source of blood in engorged female midges is identified using host-specific multiplex PCR. This assay uses primers designed to amplify the cytochrome b gene of different potential vertebrate hosts (e.g., cow, dog, human, chicken) [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful research in this field depends on a suite of specific reagents, tools, and technologies. The following table details key components of the research toolkit used in the studies discussed.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Culicoides and Leishmania Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Specific Examples/Details |

|---|---|---|

| CDC UV Light Trap | Field collection of adult Culicoides midges. | Uses ultraviolet light as an attractant; considered the gold standard for surveillance [20] [33]. |

| COI Primers | PCR amplification of the DNA barcode region. | Universal primers like LCO1490/HCO2198 target a ~658 bp region of the cytochrome c oxidase I gene [20] [28]. |

| ITS1 & SSU rRNA Primers | PCR detection and identification of Leishmania and other trypanosomatids. | ITS1 offers good resolution for species identification; SSU rRNA is useful for broader trypanosomatid screening [20] [31]. |

| Host-specific Cytochrome b Primers | Identification of blood meal sources in engorged females. | Multiplex PCR systems with primers specific to cows, dogs, chickens, humans, etc. [20]. |

| BOLD Database | Reference database for DNA barcode sequence comparison. | The Barcode of Life Data System is a central repository for curated DNA barcodes [20] [33]. |

| Species Delimitation Software | Objective classification of sequences into molecular taxa (MOTUs). | Packages for running ASAP, TCS, and PTP analyses are critical for uncovering cryptic diversity [20]. |

Discussion: Implications for Disease Control and Future Research

The resolution of cryptic species within Thai Culicoides populations fundamentally alters the landscape of leishmaniasis research and control in the region. The finding that multiple cryptic species are involved in the transmission of L. martiniquensis and L. orientalis suggests that control strategies based on a single "vector species" may be inherently flawed. Different cryptic species may exhibit variations in ecology, host preference, seasonality, and vector competence—factors that are critical for predicting disease risk and targeting interventions effectively [20].

The detection of natural, established infections of L. martiniquensis in C. peregrinus provides the strongest evidence to date that biting midges are natural vectors, not just potential ones [32]. This, combined with experimental studies showing that C. sonorensis can transmit Mundinia parasites [31], solidifies the need to shift vector control efforts beyond sand flies in certain endemic foci. Future research must focus on vector competence studies of the individual cryptic species to determine their relative efficiency in transmitting pathogens. Furthermore, the discovery of co-circulation and co-infection with other trypanosomatids like Crithidia raises questions about potential interactions within the midgut that could influence disease transmission dynamics [32].

The success of DNA barcoding in this system highlights its power but also its limitations, as its reliability is contingent on comprehensive reference libraries and the existence of a barcoding gap [30] [28]. The ~5x threshold for the global barcoding gap observed in some taxa may be a more realistic benchmark for species discovery than the often-cited 10x rule [30]. As taxonomy improves through integrative approaches, so too will the utility of DNA barcoding for disease vector surveillance.

This case study demonstrates that DNA barcoding is a powerful tool for uncovering cryptic species complexes in vector populations. Its application to Culicoides biting midges in Thailand has directly led to a paradigm shift in our understanding of Leishmania (Mundinia) transmission, confirming these insects as natural vectors. The integrative taxonomic approach—combining morphology, DNA barcoding, and species delimitation analyses—provides a robust framework for re-evaluating vector diversity and its role in disease epidemiology. For researchers and public health officials, these findings underscore that accurate vector identification at the species level is not merely a taxonomic exercise but a critical component for developing effective, evidence-based disease prevention and control strategies.

A Practical Toolkit: DNA Barcoding Workflows from Sample to Species

In parasitology, the accurate identification of species is foundational to understanding disease transmission, virulence, and drug susceptibility. This task is frequently complicated by the presence of cryptic species complexes—groups of morphologically identical but genetically distinct organisms [34]. The misidentification of these cryptic taxa can have direct clinical consequences, as they may differ in pathogenicity, drug resistance, and epidemiology [34]. DNA barcoding, the use of short standardized DNA sequences for species identification, has therefore become an indispensable tool. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the most commonly used genetic markers—COI, ITS, and 16S rRNA, among others—to help researchers select the most appropriate molecular tool for resolving cryptic diversity in parasite research.

Marker Comparison: Performance and Applications

The table below summarizes the core characteristics and documented performance of the primary DNA barcoding markers as applied to parasites and related taxa.

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Barcoding Markers for Parasitology Research

| Genetic Marker | Full Name | Best For | Advantages | Limitations | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COI | Cytochrome c Oxidase Subunit I | Arthropods, Birds, Trematodes [35] [36] | High interspecific divergence, standard for many metazoans [35] [36] | Highly variable priming sites in amphibians, can lead to amplification failure [35] | 94-95% accurate ID in parasites/vectors [4]; superior to 16S for salamander ID [37] |

| 16S rRNA | 16S Ribosomal RNA | Vertebrates, Amphibians, Nematodes [35] [38] | Highly conserved priming sites, universal amplification [35] | Lower resolution than COI in some taxa [37] | 100% amplification success vs. 50-70% for COI in frogs; discriminates amphibian larval stages [35] |

| ITS (ITS2) | Internal Transcribed Spacer 2 | Ticks, Fungi, Plants [36] | High variation for close species discrimination [36] | Requires alignment, challenging for distant taxa [35] | High correct ID rate (>96%) for tick species, comparable to COI and mitochondrial rRNAs [36] |

| 12S rRNA | 12S Ribosomal RNA | Nematodes, Vertebrates [38] | Slower evolution rate than COI, good for phylogenetics [38] | Smaller fragment size, less informative in some cases | More suitable for nematode systematics than 16S rRNA; supported monophyly of key clades [38] |

Performance Data from Key Taxonomic Groups

Experimental data from various organism groups provides critical insights for marker selection. The following table condenses quantitative findings from comparative studies.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data Across Organisms

| Organism Group | Compared Markers | Key Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amphibians (Frogs) | 16S rRNA vs. COI | 16S: 100% amplification success; COI primers: 50-70% success [35] | Vences et al., 2005 |

| Asiatic Salamanders | COI vs. 16S rRNA | COI enabled species identification where 16S sometimes failed [37] | Xia et al., 2012 |

| Ticks (Ixodida) | COI, 16S, ITS2, 12S | All four markers showed >96% correct identification rates using Nearest Neighbour methods [36] | Wang et al., 2014 |

| Parasitic Nematodes | 12S vs. 16S rRNA | 12S rRNA better supported phylogenetic relationships (monophyly of clades I, IV, V) [38] | Thaenkham et al., 2020 |

| Medically Important Parasites & Vectors | DNA Barcoding (Various) | Overall technique is 94-95% accurate compared to morphology/other markers [4] | Ondrejicka et al., 2014 |

Decision Workflow and Experimental Protocols

Workflow for Marker Selection

The following diagram outlines a logical pathway for selecting the most appropriate genetic marker based on your research organism and primary goal.

Standardized PCR Protocol for Multiple Markers

The methodology below is adapted from a comparative study on ticks, which provides a robust framework for evaluating multiple markers [36]. This can be adapted for parasites.

- DNA Extraction: Use a commercial kit (e.g., DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit from Qiagen) on ethanol-preserved tissue. Rinse specimens in distilled water prior to extraction.

- PCR Reaction Setup:

- Total Volume: 50 µL

- Reagent Mix:

- 25 µL of 2x PCR Buffer (with 1.75 mM final MgCl₂ concentration)

- 10 µL of 2 mM dNTPs

- 1 - 3 µL of primer mix (0.3 µM final concentration of each primer)

- 1 µL of DNA polymerase (e.g., KOD FX Neo, 1 unit)

- 2 µL of DNA template (~200 ng)

- Nuclease-free water to 50 µL

- Thermocycling Conditions: The protocol often uses a touchdown PCR to enhance specificity [36].

- Initial Denaturation: 94°C for 5 minutes.

- Amplification Cycles (35 cycles):

- Denaturation: 94°C for 30 seconds.

- Annealing: Variable temperature (see table below) for 30 seconds.

- Extension: 68°C for 30-60 seconds (duration depends on amplicon size).

- Final Extension: 68°C for 5 minutes.

- Post-Amplification: Verify PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis. Purify and sequence amplicons using standard protocols.

Table 3: Primer Sequences and Specific Annealing Conditions

| Marker | Primer Name | Sequence (5' to 3') | Annealing Temp. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COI | COI-F | Not specified in results | Touchdown from 52°C to 46°C | [36] |

| COI-R | Not specified in results | |||

| 16S rRNA | 16S-F | Not specified in results | Touchdown from 49°C to 43°C | [36] |

| 16S-R1 | Not specified in results | |||

| ITS2 | ITS2-F | Not specified in results | 55°C (constant) | [36] |

| ITS2-R | Not specified in results | |||

| 12S rRNA | T1B | Not specified in results | As per cited protocol | [36] |

| T2A | Not specified in results |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for DNA Barcoding Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Product / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial DNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA from parasite tissue. | DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) [36] [39] |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Accurate amplification of target barcode regions to minimize errors. | KOD FX Neo [36] |

| Species-Specific Primers | PCR amplification of the target barcode region. | Designed from conserved regions; see Table 3. |

| Agarose | Gel electrophoresis to confirm successful PCR amplification and amplicon size. | Standard molecular biology grade. |

| Sanger Sequencing Services | Determining the nucleotide sequence of the amplified DNA fragment. | Outsourced to specialized companies (e.g., BGI Tech) [36] |

| Reference Sequence Database | Comparing unknown sequences to identified species. | GenBank, BOLD (Barcode of Life Data System) [36] |

No single genetic marker is universally superior for all parasitology applications. The choice depends critically on the target organism and the specific research question. COI remains the first-choice standard for many metazoan groups, but researchers must be prepared for its potential limitations in amplification efficiency. In such cases, mitochondrial ribosomal RNAs (16S and 12S) provide a robust alternative, with 12S showing particular promise for nematode systematics [38]. The ITS2 region is a powerful, high-resolution marker for specific taxa like ticks and fungi.

The future of resolving cryptic species complexes lies in integrated taxonomy, which combines morphological, ecological, and molecular data [34] [40]. As sequencing technologies advance, the use of multiple markers simultaneously or even whole mitochondrial genomes will become more accessible, providing an even more powerful framework for understanding parasite biodiversity, evolution, and the clinical implications of cryptic diversity.

Accurate species identification is the cornerstone of effective parasitic disease control and research. However, traditional morphological identification often fails to resolve cryptic species complexes—genetically distinct species that are morphologically identical. DNA barcoding has emerged as a powerful solution, but its success is fundamentally dependent on the laboratory protocols used for DNA extraction, amplification, and sequencing. The choice of method can significantly impact the yield, purity, and molecular weight of the isolated DNA, which in turn influences the accuracy of subsequent amplification and sequencing results. This guide objectively compares the performance of various commercially available kits and techniques, providing supporting experimental data to help researchers select the most appropriate protocols for their work on parasitic cryptic species complexes.

DNA Extraction: A Critical First Step

The initial step in any DNA barcoding workflow is the extraction of high-quality genomic DNA. Effective protocols must successfully lyse a wide range of parasite organisms (e.g., Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, protozoa, helminths) and recover DNA in a pure, high-molecular-weight (HMW) form, free of inhibitors that could hamper downstream reactions.

Performance Comparison of DNA Extraction Methods

A 2023 systematic study directly compared six DNA extraction methods for their suitability for long-read metagenomic sequencing, a technique highly relevant to resolving complex parasite communities [41] [42]. The methods were evaluated using bacterial cocktail mixes and a synthetic fecal matrix to simulate a complex sample environment.

Table 1: Comparison of Six DNA Extraction Methods for Metagenomic Applications

| Extraction Method | Key Technology | Performance Summary | Suitability for Parasite Metagenomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quick-DNA HMW MagBead Kit (Zymo Research) | Magnetic Beads | Best yield of pure HMW DNA; accurate detection of nearly all bacterial species in a mock community [41]. | Highly Suitable |

| Phenol-Chloroform + Gravity Column | Chemical Lysis + Gravity Flow | Gentle on DNA, yielding HMW fragments; but time-consuming and uses hazardous chemicals [41]. | Moderately Suitable |

| Silica Spin Columns | Bead-beating + Centrifugation | Rapid and efficient; but can cause DNA shearing, potentially affecting long-read sequencing [41]. | Less Suitable for HMW DNA |

| Portable On-site Method | Not Specified | Designed for field use; convenience may come at a cost to DNA yield or quality [41]. | Situation Dependent |

The study concluded that among the tested methods, the Quick-DNA HMW MagBead Kit (Zymo Research) was the most suitable for long-read sequencing, as it provided the best yield of pure HMW DNA and allowed for the accurate detection of almost all species in a complex mock community [41].

Separate research comparing eleven DNA extraction methods for large-scale genotyping from blood samples—a common matrix for blood-borne parasites—identified only four that yielded satisfactory results [43]. The top performers were three modified silica-based commercial kits and an in-house magnetic beads-based protocol, highlighting that magnetic bead technology consistently delivers high-quality DNA.

Experimental Protocol: DNA Extraction from Complex Samples

The following protocol is summarized from the 2023 comparative study, which evaluated methods using defined bacterial communities, both pure and spiked into a synthetic fecal matrix [41].

- Sample Preparation: Cultures of Gram-positive (e.g., Bacillus subtilis) and Gram-negative (e.g., Escherichia coli) bacteria are pelleted by centrifugation, resuspended in a storage solution, and combined to create defined cell-count mixes. For matrix studies, a commercial microbial community standard is centrifuged, and the pellet is resuspended in a synthetic stool matrix.

- Cell Lysis: Protocols vary by kit. The recommended Quick-DNA HMW MagBead Kit uses a combination of lysis buffers and, potentially, gentle physical disruption to break open cells without excessively shearing the DNA.

- DNA Purification: This kit utilizes Solid-Phase Reversible Immobilization (SPRI) magnetic bead technology. The DNA binds to the magnetic beads in the presence of a binding buffer, allowing contaminants to be washed away.

- DNA Elution: The purified, high-molecular-weight DNA is eluted from the magnetic beads in a low-salt elution buffer or nuclease-free water. The extracted DNA is then quantified and qualified using spectrophotometric methods, Qubit fluorometry, and gel electrophoresis to confirm high concentration, purity, and fragment size.

Nucleic Acid Amplification: Bridging Extraction and Sequencing

Following DNA extraction, amplification is often required to increase the number of copies of a specific target gene, such as a DNA barcode region. While conventional PCR is widely used, isothermal amplification techniques offer alternatives, and hybrid methods can enhance sensitivity.

Comparison of Amplification Techniques

Different amplification techniques offer various trade-offs in speed, sensitivity, and equipment needs, which can be crucial for field applications or high-throughput screening of parasite samples.

Table 2: Comparison of Nucleic Acid Amplification Techniques

| Technique | Principle | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR | Thermal cycling with two primers | High sensitivity; gold standard for DNA amplification [44]. | Requires thermal cycler; relatively time-consuming. |

| LAMP | Isothermal amplification with 4-6 primers | Rapid (30-45 min); visual detection; does not require a thermal cycler [44] [45]. | Can be less sensitive than PCR for some targets (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 RNA) [45]. |

| NASBA/TMA | Isothermal amplification of RNA | Highly sensitive for RNA targets; useful for detecting RNA viruses [44]. | Commercial kits can be expensive. |

| Hybrid (PCDR, PCR-LAMP) | Combines PCR thermocycling with isothermal steps | Higher sensitivity and faster reaction rates than classic PCR or LAMP alone [45]. | Protocol complexity can be higher. |

A 2020 study on SARS-CoV-2 detection demonstrated that hybrid methods like Polymerase Chain Displacement Reaction (PCDR) and a novel PCR-LAMP technique showed higher sensitivity and faster reaction rates compared to conventional PCR or LAMP alone [45]. While this study focused on a virus, the principle is directly applicable to parasite diagnostics, where sensitivity is critical for detecting low-level infections.

Experimental Protocol: One-Step RT-q(PCR-LAMP)

This hybrid protocol, adapted from a SARS-CoV-2 detection study, is an example of a highly sensitive amplification workflow that could be applied to parasite RNA or DNA targets [45].

- Reaction Setup: A 25 μL reaction mixture is prepared containing the DNA or RNA template, reaction buffer, dNTPs, SYBR Green I intercalating dye, reverse transcriptase (for RNA targets), a strand-displacing DNA polymerase, and six LAMP primers (outer, inner, and loop primers).

- Amplification Profile: The reaction begins with a reverse transcription step (if needed). This is followed by a brief PCR phase (e.g., initial preheating at 92°C for 15s, followed by 1-6 cycles of 92°C denaturation and 66°C annealing/extension). The reaction then transitions to an isothermal LAMP phase at 66°C for 40 minutes.

- Detection: Amplification is monitored in real-time using the SYBR Green I dye. A positive reaction is confirmed by a characteristic amplification curve.

Sequencing and Bioinformatics for Species-Level Identification

The final step involves sequencing the amplified barcode region and using bioinformatics tools to assign taxonomic identity. The choice of sequencing platform and analysis pipeline is critical for differentiating between cryptic species.

Sequencing Platforms and Barcoding Strategies

- Long-Read Sequencing (e.g., Oxford Nanopore): Platforms like Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) MinION offer portability and long reads, which help resolve complex genomic regions. Its accuracy has continuously improved with updated basecalling algorithms [46]. A 2023 study confirmed its effectiveness when used with high-quality HMW DNA extracted via the best-performing kits [41].

- Barcoding Gene Region: For parasites, the 18S ribosomal RNA gene is a commonly used barcode. A 2025 study demonstrated that targeting the V4–V9 hypervariable regions of the 18S rDNA (~1 kb) provided superior species-level identification compared to using the shorter V9 region alone, especially on error-prone portable sequencers [21].

- Host DNA Depletion: In blood samples, host DNA can overwhelm parasite signal. The same 2025 study designed blocking primers (C3 spacer-modified oligos and Peptide Nucleic Acids) that bind to host 18S rDNA and suppress its amplification during PCR, thereby enriching for parasite DNA [21].

Bioinformatics and Identification Pipelines

After sequencing, specialized bioinformatics tools are required for accurate species assignment.

- The Probability of Correct Identification (PCI): This metric provides a quantitative measure of a barcode's efficacy. The overall PCI for a dataset is the average of the species-specific PCIs, providing a standardized way to compare different barcode markers or methods [47].

- Web-Based Platforms: Tools like the Parasite Genome Identification Platform (PGIP) have been developed to simplify bioinformatics for non-specialists. PGIP is a web server that uses a curated database of 280 parasite genomes and a standardized pipeline (including host DNA depletion and Kraken2 for taxonomic classification) to provide rapid, accurate species-level identification from sequencing data [16].

DNA Barcoding Workflow for Parasite ID

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for implementing the DNA barcoding workflow for parasite identification, as derived from the cited experimental protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Parasite DNA Barcoding

| Item | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Quick-DNA HMW MagBead Kit (Zymo Research) | Extraction of high molecular weight DNA from complex samples for long-read sequencing [41]. | Top-performing kit for bacterial metagenomics in a 6-method comparison [41]. |

| Magnetic Bead Stand | Separation of magnetic beads from solution during DNA purification steps. | Implied in all magnetic bead-based extraction protocols [41] [43]. |

| Blocking Primers (C3 spacer / PNA) | Suppresses amplification of host DNA (e.g., human, bovine) in blood samples to enrich parasite signal [21]. | Designed to block mammalian 18S rDNA in a blood parasite NGS test [21]. |

| Universal 18S rDNA Primers (F566 / 1776R) | Amplifies a ~1.2 kb barcode region (V4-V9) from a wide range of eukaryotic parasites for species-level identification [21]. | Used for broad-range detection of blood parasites from phyla Apicomplexa, Euglenozoa, etc. [21]. |

| Strand-Displacing DNA Polymerase | Essential enzyme for isothermal amplification methods like LAMP and hybrid PCR-LAMP [45]. | Used in RT-q(PCR-LAMP) and RT-qLAMP assays for SARS-CoV-2 [45]. |

| Kraken2 Software & Curated Database | Rapid taxonomic classification of sequencing reads against a reference database [16]. | Core of the reads-based identification module in the PGIP platform for parasites [16]. |

Bioinformatic Analysis and Species Delimitation Methods (ASAP, PTP, TCS)

Cryptic species complexes, where morphologically similar organisms constitute distinct biological species, represent a significant challenge in parasitology research. The accurate delimitation of these species is fundamental for understanding disease transmission dynamics, vector ecology, and for developing targeted control strategies. DNA barcoding, typically using the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene, has emerged as a powerful tool for disentangling these complexes. However, the analytical methods applied to barcode data significantly influence the resulting species hypotheses. This guide objectively compares three prominent species delimitation methods—ASAP, PTP, and TCS—within the context of resolving cryptic species complexes in parasites, providing researchers with experimental data and protocols to inform their methodological choices.

Core Principles and Requirements

ASAP (Assemble Species by Automatic Partitioning) is a hierarchical clustering algorithm that operates on pairwise genetic distances from single-locus alignments (e.g., DNA barcodes), avoiding the computational burden of phylogenetic reconstruction. It proposes species partitions ranked by a scoring system that requires no biological prior insight of intraspecific diversity. ASAP is highly efficient, capable of processing datasets of up to 10^4 sequences in minutes, and is accessible via both a graphical web interface and a standalone program [48] [49].

PTP (Poisson Tree Processes) models speciation events in terms of the number of substitutions, requiring a phylogenetic input tree where branch lengths represent the number of substitutions. Its fundamental assumption is that the number of substitutions between species is significantly higher than within species. A key advantage is that it does not require an ultrametric tree, thus avoiding the computationally intensive and potentially error-prone process of time-calibration. A Bayesian implementation (bPTP) provides posterior probabilities for delimitation hypotheses [50] [51] [52].

TCS (Statistical Parsimony) implements a network-based approach to estimate gene genealogies under a parsimony framework. It is commonly used to visualize evolutionary relationships among haplotypes and can delineate species boundaries by identifying disconnected networks at a given connection limit, often 95%. It is frequently integrated into analyses using software like PopART [53].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of ASAP, PTP, and TCS.

| Method | Underlying Concept | Primary Input | Key Requirement | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASAP | Hierarchical clustering based on genetic distances [48] [49] | Single-locus sequence alignment (e.g., COI) | Pairwise genetic distance matrix [48] [49] | Ranked species partitions |

| PTP/bPTP | Models speciation via number of substitutions (Poisson process) on a tree [50] [51] | Phylogenetic tree (Newick/NEXUS) | Branch lengths in substitutions [50] [51] | Species delimitation with support values (ML or Bayesian) |

| TCS | Statistical parsimony network estimation [53] | Sequence alignment (e.g., NEXUS format) | Connection limit (e.g., 95%) [53] | Haplotype network showing connectivity |

Workflow Integration