Preserving Parasite Integrity: Advanced Strategies to Prevent Specimen Deterioration in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on preventing specimen deterioration in parasitology.

Preserving Parasite Integrity: Advanced Strategies to Prevent Specimen Deterioration in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on preventing specimen deterioration in parasitology. It synthesizes current evidence on preservation mediums, collection methodologies, and storage protocols to maintain specimen integrity for both morphological and molecular analyses. The scope covers foundational principles of parasite degradation, practical application of preservation techniques, troubleshooting for common pre-analytical errors, and a comparative validation of traditional versus modern diagnostic platforms. By addressing critical pre-analytical variables, this resource aims to enhance diagnostic reliability, ensure reproducible research outcomes, and support the development of robust parasitological assays in clinical and pharmaceutical settings.

The Science of Specimen Degradation: Understanding Parasite Vulnerability and Preservation Fundamentals

In parasitology, the integrity of collected specimens is a foundational requirement for accurate diagnosis and reproducible research. Rapid degradation of samples post-collection directly compromises diagnostic sensitivity by altering morphological features, breaking down antigenic targets, and causing nucleic acid fragmentation. This degradation manifests as false-negative results, reduced accuracy in parasite identification, and ultimately, an inability to replicate experimental findings across different laboratories. The challenges are particularly acute in field conditions and resource-limited settings where controlled storage is often unavailable. Understanding and mitigating these degradation pathways is therefore not merely a technical concern, but a prerequisite for generating reliable data in parasitology education, research, and drug development [1] [2].

Understanding the Degradation Challenge

Primary Mechanisms of Specimen Degradation

Parasitology specimens are vulnerable to several environmental and intrinsic factors that drive their degradation. The table below summarizes the key mechanisms and their specific impacts on diagnostic targets.

Table 1: Key Mechanisms of Specimen Degradation and Their Impacts

| Degradation Mechanism | Primary Effects on Specimen | Impact on Diagnostic Targets |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic Activity | Autolysis (self-digestion) of tissues and cells; breakdown of proteins and nucleic acids [2]. | Degradation of antigen epitopes for immunological tests; fragmentation of DNA/RNA for molecular assays [3]. |

| Oxidation | Damage to proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids via reactive oxygen species [4]. | Alteration of protein antigens, reducing antibody binding affinity in immunoassays [4]. |

| Microbial Putrefaction | Overgrowth of saprophytic bacteria and fungi consuming the specimen [2]. | Destruction of parasite structures; consumption of parasite DNA/RNA; obscuring of morphological details [2]. |

| Desiccation | Loss of moisture, leading to structural collapse and crystallization of biomolecules [2]. | Shriveling of helminth eggs and larval stages, making them unrecognizable under microscopy [2]. |

| Photolysis | Breakdown of molecules due to exposure to light, particularly UV radiation [4]. | Loss of fluorescence in labeled assays; bleaching of pigments in parasites like Plasmodium [4]. |

Consequences for Diagnostic Sensitivity

The practical consequence of these degradation processes is a marked decline in diagnostic sensitivity. For example, the viability of first-, second-, and third-stage larvae of nematodes from the Ancylostomatidae and Strongyloididae families is rapidly lost if fecal samples are frozen or dried immediately after collection, as these larvae require specific conditions for concentration techniques like the Baermann apparatus to work effectively. This can directly lead to false-negative results [2]. Similarly, morphological identification of adult worms is hampered if they are preserved incorrectly; placing worms directly in ethanol or cold buffer causes muscle contraction, distorting key taxonomic structures and leading to misidentification [2]. For molecular methods, which are increasingly central to parasitology, DNA degradation begins immediately after a sample is produced and accelerates at higher temperatures, directly reducing the sensitivity of PCR and other amplification techniques [2].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This section addresses common, specific challenges faced by researchers in managing specimen degradation.

FAQ 1: What is the single most critical step to ensure the reproducibility of parasitological results from field-collected samples?

Answer: The most critical step is the immediate stabilization and appropriate preservation of the sample based on the intended downstream analysis. There is no universal preservative, and the choice must be tailored to the diagnostic or research method planned. For instance, sample storage at room temperature is suitable for analysis within 24 hours, but DNA degradation begins immediately. For molecular studies, freezing at -20°C is the preferred method, though some larval forms may lose viability. The key to reproducibility is meticulously documenting the time of collection, the preservation method, and the time to final storage, and ensuring these protocols are uniform across all sample collections in a study [2].

FAQ 2: Our laboratory frequently obtains conflicting results when using molecular versus microscopic methods on the same batch of samples. Could degradation be a factor, and how can we troubleshoot this?

Answer: Yes, differential degradation is a likely factor. Microscopy relies on intact morphological structures, while molecular methods require high-quality nucleic acids. These components degrade at different rates.

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Positive microscopy but negative PCR.

- Possible Cause: Inhibitors in the sample or poor DNA extraction efficiency.

- Solution: Include an internal control in the PCR reaction to detect inhibitors. Re-optimize the DNA extraction protocol, including mechanical lysis for tough cysts or oocysts.

- Problem: Negative microscopy but positive PCR.

- Possible Cause: The parasites are degraded and no longer morphologically identifiable, but their DNA is still intact and detectable.

- Solution: This highlights the higher sensitivity of PCR for degraded samples. Standardize the time between collection and analysis to minimize this discrepancy and establish a clear criterion for a positive result.

- General Action: Always record the time lapse between sample collection and processing for both analyses. Using a multiplex PCR approach that can detect several parasites simultaneously can also help clarify ambiguous results [1] [2].

FAQ 3: For long-term biobanking of parasitic specimens, what preservation method best balances the needs for morphological, molecular, and immunological studies?

Answer: A single method is often insufficient for multi-modal research. The best practice involves tripartite preservation:

- For Morphology: Fixation in 10% neutral buffered formalin is the gold standard for preserving morphological detail for histology.

- For Molecular Biology: Preservation in 95%-100% ethanol or freezing at -80°C is optimal for maintaining DNA integrity. RNA requires immediate stabilization in RNAlater or flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen.

- For Immunology: Freezing at -80°C is generally best for preserving protein antigens for western blot or ELISA. Note that formalin fixation can cross-link and mask epitopes, making it unsuitable for many immunological assays [2].

Table 2: Optimal Sample Preservation Methods by Downstream Application

| Application | Recommended Method | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Microscopy (Ova/Parasite) | 10% Formalin, SAF, PVA (for fresh samples) [1] | Room temperature storage is acceptable; avoids freezing artifacts. |

| Molecular (PCR, NGS) | 95-100% Ethanol, Freezing (-20°C or -80°C) [2] | Freezing is superior for long-term DNA/RNA integrity. |

| Culture | Analysis within 1-2 hours; no preservative [1] | Refrigeration (4°C) can briefly maintain viability. |

| Immunoassays | Freezing (-80°C), Specific commercial buffers | Avoid formalin; can denature protein targets. |

| Morphology (Adult Worms) | Warm PBS/Saline (to relax), then 70% Ethanol [2] | Prevents contraction and distortion of taxonomic structures. |

Standardized Experimental Protocols to Mitigate Degradation

Protocol: Collection and Preservation of Fecal Samples for Multi-Method Analysis

Principle: To standardize the collection of fecal specimens to maximize their utility for concurrent microscopic, molecular, and cultural diagnostics, while minimizing pre-analytical degradation.

Materials:

- Clean, leak-proof, wide-mouth containers

- Disposable gloves and applicator sticks

- Labels and waterproof pens

- Cooler with ice packs or liquid nitrogen for flash freezing

- Preservatives: 10% formalin, 95% ethanol, RNAlater

- Pre-portioned containers for sub-sampling

Procedure:

- Collection: Using an applicator stick, collect multiple portions of the fecal specimen, focusing on areas with mucus or visible abnormalities. Place them into the primary container.

- Immediate Sub-sampling (Within 1-2 hours of collection):

- For Microscopy: Aliquot 1-2 g of feces into a container with 10 mL of 10% formalin. Mix thoroughly.

- For Molecular Biology: Aliquot 1-2 g of feces into a container with 5-10 mL of 95% ethanol. Ensure the sample is fully submerged. Alternatively, flash-freeze a 0.5 g aliquot in a cryovial.

- For Culture/Baermann: Process the fresh sample immediately. If a delay is unavoidable, refrigerate (4°C) for no more than 24 hours. Do not freeze or preserve.

- Documentation: Record the time of collection, time of preservation, and any preservatives used.

- Storage and Transport: Store formalin-fixed samples at room temperature. Store ethanol-preserved and frozen samples at -20°C (short-term) or -80°C (long-term). Transport on ice or with cold packs [2].

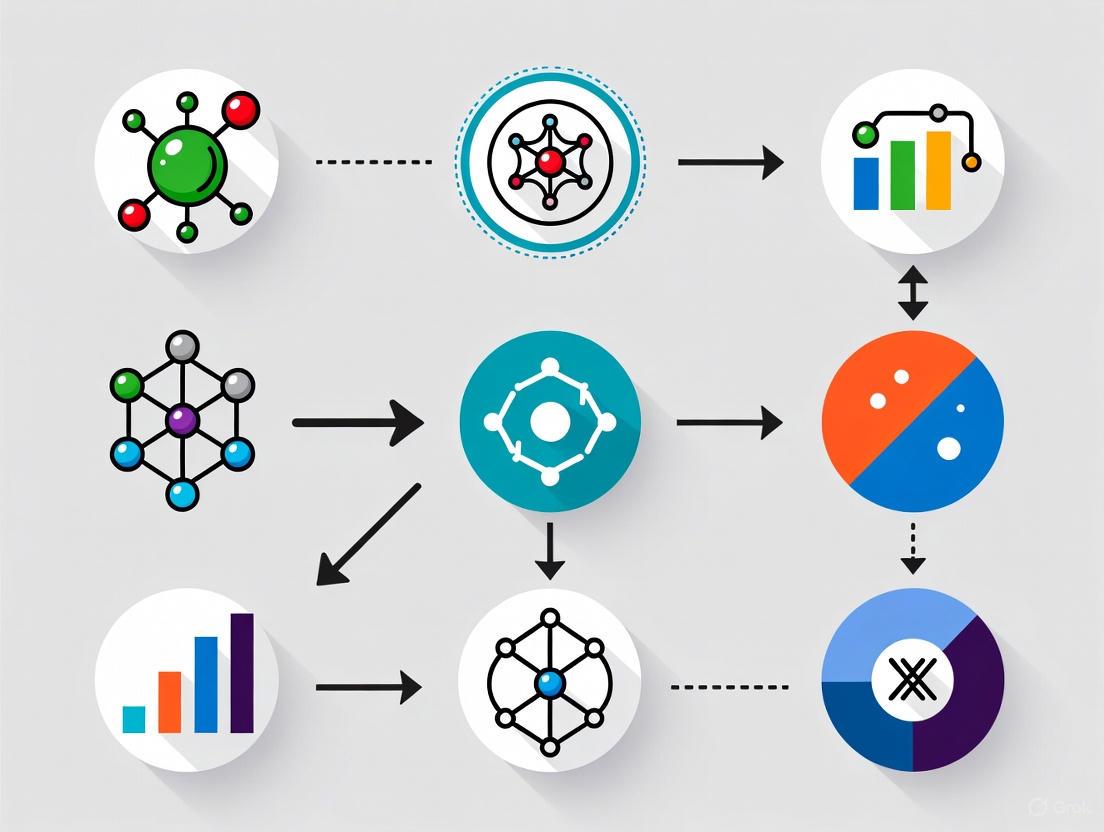

Workflow: Integrity Management of Parasitology Specimens

The following diagram illustrates the critical decision points and pathways for handling parasitology specimens to ensure integrity from collection to analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for preventing specimen degradation in parasitology research.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Specimen Integrity in Parasitology Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specific Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| 95-100% Ethanol | Nucleic acid preservation and fixation [2]. | Ideal for long-term storage of feces, tissue, or arthropod vectors for DNA-based PCR and sequencing. |

| RNAlater Stabilization Solution | Stabilizes and protects cellular RNA [2]. | Preserving gene expression profiles in parasite-infected tissues; critical for transcriptomic studies. |

| 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin | Tissue fixation and morphological preservation [2]. | Gold standard for histopathological examination of tissue sections containing parasites. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | Isotonic buffer for temporary specimen maintenance [2]. | Washing parasites collected from cultures; relaxing adult helminths before preservation to prevent contraction. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | Preservative and adhesive for fecal specimens [1]. | Fixing protozoan trophozoites and cysts in stool for permanent staining (e.g., Trichrome stain). |

| Sodium Acetate-Acetic Acid-Formalin (SAF) | All-purpose fixative for fecal specimens [1]. | Suitable for concentration procedures and permanent staining; allows for later molecular testing. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (3%) | Oxidative stressor in forced degradation studies [4]. | Modeling oxidative degradation of drug compounds or diagnostic antigens in stability studies. |

Parasite Biology and Vulnerabilities

Understanding the fundamental biology and life cycles of parasites is the first step in identifying their critical vulnerabilities for both therapeutic intervention and specimen preservation.

Hookworm Biology and Life Cycle

Hookworms are nematode parasites with a direct life cycle involving several distinct developmental stages. The primary species infecting humans are Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus [5] [6]. The table below summarizes the key stages and their characteristics:

Table 1: Hookworm Life Cycle Stages and Vulnerabilities

| Stage | Duration | Key Characteristics | Potential Vulnerabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Egg | 24-48 hours to hatch [7] | Passed in feces, thin-shelled oval shape [8] | Environmental conditions (desiccation, temperature extremes) [7] |

| Rhabditiform Larva (L1) | 1-2 days after hatching [5] | Feeds on feces, non-infective [5] | Limited survival outside host, requires specific conditions |

| Filariform Larva (L3) | 3-4 weeks in soil [5] | Developmentally arrested, infective stage [6] | Desiccation, direct sunlight, salt water [5] |

| Adult Worm | 1-5 years [5] | Inhabits small intestine, blood-feeding [7] | Blood-feeding mechanism, attachment to intestinal mucosa |

The life cycle begins when eggs are passed in human feces and deposited into soil [5]. Under appropriate warm, moist, shaded conditions, eggs hatch into first-stage rhabditiform larvae (L1) within 1-2 days [7] [5]. These larvae feed on feces and undergo two molts over 5-10 days to become infective filariform larvae (L3) [5]. These L3 larvae are developmentally arrested and can survive in damp soil for several weeks awaiting a host [5].

Infection occurs when L3 larvae penetrate human skin, most commonly through the feet [5] [6]. Upon penetration, larvae receive host-specific signals that cause them to resume development and secrete bioactive polypeptides [6]. The larvae migrate through the bloodstream to the lungs, break into alveoli, ascend the bronchial tree to the pharynx, and are swallowed [5] [8]. During pulmonary migration, they may cause Löffler syndrome with cough, wheezing, and eosinophilia [8].

Once in the small intestine, larvae undergo two further molts, developing a buccal capsule and attaining adult form [5]. Adult worms attach to the mucosal layer of the small intestine using teeth (A. duodenale) or cutting plates (N. americanus) [5] [6]. They release hydrolytic enzymes and anticoagulants that facilitate blood feeding and cause continuous blood loss from the host [5]. Adult worms become sexually mature in 3-5 weeks, after which females begin producing thousands of eggs daily that are passed in feces to continue the cycle [5].

Dientamoeba fragilis Biology and Challenges

Dientamoeba fragilis is a trichomonad parasite with a poorly understood life cycle and transmission mechanism [9] [10]. Unlike most intestinal protozoa, it appears to exist only in the trophozoite stage, with no confirmed cyst stage [10] [11]. This creates significant research challenges as the parasite is sensitive to aerobic environments and quickly degrades when placed in saline, tap water, or distilled water [11].

The parasite inhabits the mucosal crypts of the large intestine, from the cecum to the rectum, typically located close to the mucosal epithelium [11]. It is not considered invasive and does not cause cellular damage, but may invoke an eosinophilic inflammatory response that leads to superficial colonic mucosal irritation and symptoms [11].

Transmission mechanisms remain incompletely understood, with conflicting evidence. Proposed routes include direct fecal-oral spread, possible co-infection with pinworm (Enterobius vermicularis) eggs, and potential zoonotic transmission from pigs, which have been identified as natural hosts [10] [11]. The absence of a confirmed cyst stage and rapid degradation outside the host present significant challenges for both research and diagnostic purposes [11].

Specimen Preservation and Experimental Methodologies

Proper preservation of parasite specimens is critical for accurate research and diagnostic outcomes. Different parasites require specific handling protocols to maintain morphological integrity.

Hookworm Preservation Protocols

Stool Specimen Processing for Egg Identification:

- Collect fresh stool specimens in clean, dry containers

- Process within 24-48 hours for optimal egg viability [8]

- Use concentration techniques (e.g., formalin-ethyl acetate) for light infections

- Prepare permanently stained smears for morphological examination

- Maintain specimens at 4°C if immediate processing isn't possible

Adult Worm Preservation:

- Collect worms during endoscopic procedures or post-treatment

- For morphological studies, fix in 10% formalin or 70% ethanol

- For molecular studies, freeze at -80°C or preserve in RNA-later

- For teaching collections, consider plastination using S10 technique [12]

Plastination Protocol for Macroparasites (S10 Technique):

- Fixation: Specimens are fixed in 10% formalin

- Dehydration: Sequential dehydration in cold acetone baths (-25°C)

- Impregnation: Forced impregnation with silicone polymer under vacuum

- Curing: Gas curing with dichlorodimethylsilane [12]

This technique produces dry, odorless specimens free of carcinogenic preservatives, though some species may experience collapse requiring protocol modifications [12].

D. fragilis Preservation Challenges and Solutions

D. fragilis presents unique preservation challenges due to its lack of a cyst stage and sensitivity to environmental conditions [11]. The following workflow outlines the critical preservation pathway:

Critical Preservation Protocol:

- Immediate Processing: Preserve stool specimens immediately after passage using appropriate fixatives [11]

- Multiple Specimens: Collect a minimum of three fecal specimens every other day due to intermittent shedding [10]

- Fixative Selection: Use polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) or sodium acetate-acetic acid-formalin (SAF) fixatives

- Staining Requirements: Always prepare permanently stained smears (trichrome or iron-hematoxylin) for examination under oil immersion (1000×) [10]

- Molecular Preservation: For PCR studies, preserve samples in specific nucleic acid preservatives or freeze at -80°C

Culture Techniques: Though not routine in clinical laboratories, D. fragilis can be cultured from clinical specimens, providing another preservation method for research purposes [10].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table outlines essential research reagents and their applications in parasitology research, particularly for hookworms and D. fragilis:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Parasitology Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Preservation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixatives | 10% Formalin, PVA, SAF, 70% ethanol [12] | Morphological preservation | Formalin preferred for histology; ethanol for molecular work |

| Staining Reagents | Trichrome stain, Iron-hematoxylin, Kato-Katz reagents [10] [13] | Microscopic identification | Trichrome essential for D. fragilis; Kato-Katz for egg quantification |

| Molecular Biology Kits | DNA/RNA extraction kits, PCR master mixes, RT-PCR reagents | Species identification, genotyping | RNase-free environment for RNA work; specific preservatives for nucleic acids |

| Culture Media | Locke-egg-serum medium, other trichomonad media [10] | Parasite propagation and maintenance | Strict temperature control; regular subculturing |

| Anthelmintic Agents | Albendazole, Mebendazole, Pyrantel pamoate [8] [13] | Drug efficacy studies | Proper storage conditions; solubility considerations for in vitro studies |

| Protease Inhibitors | EDTA, protease inhibitor cocktails | Enzyme function studies | Temperature-sensitive; aliquot to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles |

| Silicone Polymers | Biodur S10/S15 [12] | Plastination for teaching collections | Specific curing protocols; vacuum impregnation requirements |

Troubleshooting Common Research Scenarios

Hookworm-Specific Issues

Problem: Rapid degradation of hookworm eggs in stool samples Solution: Process stool samples within 24 hours of collection. If delayed, refrigerate at 4°C but avoid freezing. Use concentration techniques for low egg burdens [8].

Problem: Inconsistent egg counts in quantitative studies Solution: Utilize standardized egg counting methods like Kato-Katz technique. Account for day-to-day variation in egg output by multiple sampling. Be aware that egg production varies by species (A. duodenale: 10,000-30,000 eggs/female/day; N. americanus: 5,000-10,000 eggs/female/day) [5].

Problem: Poor recovery of adult worms for molecular studies Solution: Collect worms post-treatment with anthelmintics. Preserve immediately in 70% ethanol or RNA-later for genetic studies. For morphological studies, fix in hot (60°C) 70% ethanol or 10% formalin.

D. fragilis-Specific Issues

Problem: False-negative results in stool examination Solution: Collect multiple stool specimens (minimum of three) every other day due to intermittent shedding [10]. Use permanent stains and examine under oil immersion (1000×). Consider PCR-based detection for improved sensitivity.

Problem: Rapid degradation of trophozoites after passage Solution: Preserve specimens immediately in appropriate fixatives. Avoid saline, tap water, or distilled water which cause rapid disintegration [11]. Process fresh specimens within a few hours of collection.

Problem: Inability to maintain long-term cultures Solution: Use specialized trichomonad media with regular subculturing. Consider co-culture systems or addition of antimicrobial agents to prevent bacterial overgrowth.

Advanced Experimental Workflows

For researchers investigating parasite biology and drug development, the following integrated workflow provides a framework for comprehensive study:

Target Identification Strategies

Hookworm Molecular Targets:

- Blood-feeding Mechanism: Metalloproteases and anticoagulant peptides that facilitate blood digestion [6]

- Larval Activation Proteins: Asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase and other secreted proteins released during host invasion [6]

- Neuronal Signaling Pathways: cGMP-dependent pathways involved in larval development resumption [6]

- Immune Evasion Molecules: Protease inhibitors and T-cell apoptosis inducers that enable chronic infection [13]

D. fragilis Research Targets:

- Metabolic Pathways: Unique enzymes identified through transcriptome sequencing [14]

- Kinome Analysis: Protein kinases potential drug targets [14]

- Degradome Characterization: Peptidases with potential pathogenicity roles [14]

- Virulence Factors: Mechanisms of pathogenicity despite non-invasive nature [14]

Drug Efficacy Testing Protocols

In vitro Hookworm Larval Assay:

- Collect fresh fecal samples containing hookworm eggs

- Incubate at 27°C for 7-10 days to allow development to L3 larvae

- Prepare drug dilutions in appropriate solvents

- Expose L3 larvae to various drug concentrations for 24-48 hours

- Assess larval motility and viability using standardized scoring systems

- Calculate LC50 values for compound comparison

Antigen Detection Assays for D. fragilis:

- Develop specific monoclonal antibodies against surface antigens

- Establish ELISA-based detection systems for culture supernatants

- Validate with clinical specimens of known status

- Correlate antigen levels with clinical symptoms and parasite burden

FAQs: Addressing Critical Research Challenges

Q: What is the most vulnerable stage in the hookworm life cycle for intervention? A: The L3 larval stage during skin penetration and migration is particularly vulnerable. At this stage, larvae are transitioning from free-living to parasitic forms and secreting various proteins essential for host invasion. These secreted proteins represent potential targets for vaccines or drugs [6].

Q: Why is D. fragilis so difficult to maintain in research settings? A: The primary challenges include: (1) absence of a confirmed cyst stage, limiting long-term survival; (2) sensitivity to aerobic environments; (3) rapid degradation in water-based solutions; and (4) lack of optimized axenic culture systems. Immediate preservation in appropriate fixatives and specialized culture media are essential [11].

Q: What preservation method is most suitable for teaching collections? A: Plastination using the S10 technique offers significant advantages: specimens are dry, odorless, maintain morphological features, and eliminate exposure to carcinogenic formaldehyde. However, protocol modifications may be needed for certain species prone to collapse [12].

Q: How can molecular techniques overcome limitations in parasite detection? A: PCR-based methods offer: (1) increased sensitivity for low-level infections; (2) species-specific identification; (3) ability to use fixed specimens; and (4) quantification of parasite burden. For D. fragilis, real-time PCR has shown superior sensitivity compared to microscopic examination [10].

Q: What are the key considerations when testing anthelmintic efficacy? A: Critical factors include: (1) parasite species and developmental stage; (2) drug solubility and stability; (3) appropriate outcome measures (egg reduction vs. worm burden); (4) accounting for natural variation in egg output; and (5) considering potential drug resistance mechanisms [8] [13].

Within parasitology education and research, the paramount goal is to prevent the deterioration of valuable and often irreplaceable biological specimens. The integrity of these specimens is foundational for accurate morphological diagnosis, training future parasitologists, and advancing research. Central to achieving this goal are preservatives, with formalin and ethanol being the most widely used. Understanding their mechanisms of action on cellular and molecular levels is not merely academic; it is crucial for selecting the right preservative for the intended application, whether for long-term morphological preservation, molecular analysis, or museum display. This technical support center delves into the science behind these common preservatives, providing troubleshooting guidance and protocols to empower researchers in making informed decisions for their specific experimental needs.

Core Mechanisms of Action

Formalin: The Cross-Linking Fixative

Formalin, an aqueous solution of formaldehyde, acts primarily through covalent cross-linking of biomolecules [15]. Its action can be broken down into a multi-step process:

- Initial Reaction: Formaldehyde rapidly reacts with primary amino groups (e.g., in lysine residues), sulfhydryl groups, and amide groups in proteins to form hydroxymethyl derivatives [16].

- Cross-linking: These hydroxymethyl groups then undergo slower condensation reactions with other nearby nitrogen atoms (e.g., from arginine, tryptophan, or tyrosine) or other reactive groups, forming stable methylene bridges (-CH2-) [16] [17]. This creates a three-dimensional network of cross-linked proteins.

Cellular and Molecular Consequences:

- Protein Immobilization: The cross-linking network stabilizes and hardens the tissue architecture, rendering proteins insoluble and inactivating enzymes that cause autolysis and decay [15] [17].

- Morphological Preservation: This cross-linking is exceptionally effective at preserving the fine structural details of cells and tissues, which is why it is the gold standard for histopathology [16].

- Nucleic Acid Impact: While it also reacts with and cross-links nucleic acids, this process fragments RNA and makes both DNA and RNA difficult to extract in a high-quality, intact form [18].

- Antigen Masking: Extensive cross-linking can sterically hinder antibody binding to specific epitopes, reducing immunorecognition in techniques like immunohistochemistry [16].

Diagram 1: Formalin's protein cross-linking mechanism.

Ethanol: The Dehydrating Agent

Ethanol (and other alcohols like methanol) functions primarily through dehydration and precipitation [17].

- Dehydration: Ethanol, being miscible with water, rapidly replaces water in the cells and tissues.

- Protein Precipitation: This dehydration disrupts the hydrogen-bonding network that maintains the tertiary and quaternary structures of proteins. This causes protein denaturation and precipitation, effectively halting enzymatic activity [17].

Cellular and Molecular Consequences:

- Bacterial Inhibition: By dehydrating and denaturing proteins, ethanol kills bacteria and fungi, preventing microbial decomposition [15] [19].

- Macromolecule Precipitation: It precipitates proteins and nucleic acids, which can help preserve them in a relatively stable state. Unlike formalin, it does not fragment RNA, allowing for the recovery of high-quality RNA for molecular studies [18].

- Structural Alteration: The precipitating action can cause tissue shrinkage and hardening. It is less effective than formalin at preserving fine cytological detail over the very long term and can leach color from specimens [19].

Diagram 2: Ethanol's protein dehydration and precipitation mechanism.

Comparative Data and Protocols

Quantitative Comparison of Preservative Effects

The choice between formalin and ethanol has measurable consequences for downstream analyses. The table below summarizes key comparative data.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Formalin vs. Ethanol Effects

| Parameter | Formalin (10% NBF) | 70% Ethanol | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Yield | Negligible quantity recovered [18] | ~70% of yield from fresh-frozen tissue [18] | Laser capture microdissected brain tissue [18] |

| RNA Integrity | Composed of low-MW fragments; RT-PCR often fails [18] | Integrity comparable to fresh frozen; RT-PCR successful [18] | Laser capture microdissected brain tissue [18] |

| Immunorecognition | Progressive loss with fixation >18h; complete loss for some antigens by 108h [16] | Maintained after transfer from 12h NBF fixation [16] | DU145 & SKOV3 cell lines, antibodies to PCNA, Ki67, cytokeratins [16] |

| Preservation Stability | Effective for several years; may discolor specimens [19] | Effective for several years; leaches color from specimens [19] | Long-term museum conservation [19] |

| Ideal Use Case | Morphological preservation for histology; long-term storage of structural detail [15] [16] | RNA/DNA preservation; post-fixation storage for IHC; disinfecting surfaces [16] [18] | Varies by experimental goal |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimized Fixation for Immunohistochemistry

This protocol, derived from cell line studies, demonstrates how to preserve immunorecognition by transferring specimens from formalin to ethanol [16].

Methodology:

- Fixation: Fix cells or thin (≤3mm) tissue samples in 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin (NBF) for 12 hours at room temperature.

- Transfer: Do not leave specimens in NBF indefinitely. After 12 hours, transfer them to 70% ethanol for storage until processing.

- Storage in Ethanol: Specimens can be stored in 70% ethanol for extended periods (tested up to 168 hours, or 7 days) without the significant loss of immunorecognition that occurs with prolonged formalin fixation [16].

- Processing: After storage in ethanol, process the tissues through standard dehydration and paraffin embedding.

Troubleshooting Note: Prolonged fixation in NBF beyond 18-36 hours leads to increased cross-linking and masking of epitopes for antibodies like PCNA and Ki67, resulting in decreased or complete loss of immunostaining [16].

Protocol 2: Preservation for RNA Analysis

This protocol highlights the superiority of ethanol for gene expression studies [18].

Methodology:

- Immersion Fixation: Immerse tissue samples (e.g., brain tissue) in 70% ethanol.

- Fixation Duration: Fixation can be performed at 4°C for up to 2 weeks without degrading RNA yield or quality [18].

- Processing: Process the ethanol-fixed tissues to paraffin embedding using standard protocols.

- RNA Extraction: Extract RNA using standard methods like TRIzol. The resulting RNA will be of high integrity, suitable for RT-PCR and cDNA microarray analysis, even after laser capture microdissection [18].

Troubleshooting Note: RNA extracted from formalin-fixed tissues is highly fragmented and often yields negligible amounts, making it unreliable for downstream molecular applications like RT-PCR [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Specimen Preservation

| Reagent / Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin (NBF) | Cross-linking fixative for superior morphological preservation. | Prevents acid formalin hematin pigment artifact; the buffer maintains neutral pH [15] [16]. |

| 70% Ethanol | Dehydrating fixative and storage medium. | Optimal concentration for penetration and protein precipitation; used for RNA preservation and storing formalin-fixed samples [16] [18]. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | Preservative for fecal specimens in parasitology. | Contains a plastic resin that adheres stool to slides; allows permanent staining but contains mercury [20]. |

| Sodium Acetate-Acetic Acid-Formalin (SAF) | All-purpose fecal preservative. | Used for concentration and stained smears; mercury-free but has poor adhesive properties [20]. |

| Methanol | Alcohol-based fixative and permeabilizing agent. | Often used as a stabilizer in formalin; pre-fixes blood smears for shipment; denatures proteins [15] [17]. |

| Triton X-100 | Non-ionic detergent for permeabilization. | Disrupts lipid bilayers to allow antibody access to intracellular antigens after fixation [17]. |

| Saponin | Cholesterol-binding detergent for permeabilization. | Selectively permeabilizes plasma membranes without disrupting organelles, useful for intracellular staining [17]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: Why did my immunostaining fail even though I used a validated antibody on formalin-fixed tissue?

Answer: The most likely cause is over-fixation. While 10% NBF is excellent for morphology, fixation for longer than 18-36 hours can lead to excessive cross-linking, which masks the epitope your antibody recognizes [16].

- Solution: Limit fixation time in NBF to 6-12 hours for thin tissues. For unavoidable delays, transfer the tissue from formalin to 70% ethanol after 12 hours. This "holds" the tissue in a state that preserves immunorecognition much better than prolonged formalin storage [16].

FAQ 2: We need to perform both histological examination and RNA sequencing from the same rare parasite specimen. What is the best preservation strategy?

Answer: This is a common dilemma as the fixatives are mutually exclusive for a single sample. Formalin destroys RNA integrity, while ethanol provides inferior morphology [18].

- Solution: If possible, divide the specimen. Place one part in 10% NBF for optimal histology and another part in 70% ethanol for optimal RNA extraction [18]. If the specimen cannot be divided, 70% ethanol is the compromise, as it provides adequate histology for many diagnostic purposes and preserves high-quality RNA [18].

FAQ 3: In parasitology, what is the best preservative for stool specimens if I want to do both a concentration test and a permanent stain?

Answer: No single preservative is perfect, but Sodium Acetate-Formalin (SAF) and Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) are the top choices.

- SAF is mercury-free and can be used for both concentration and stained smears, though staining quality with trichrome may be inferior to PVA [20].

- PVA is the traditional choice for excellent permanent stained smears but contains mercury and is less ideal for concentrating some helminth eggs [20]. Your choice may depend on local regulations regarding mercury disposal and the specific parasites you are targeting.

FAQ 4: My tissue specimen preserved in ethanol has become shrunken and brittle. Is this normal?

Answer: Yes, some degree of shrinkage and hardening is a normal consequence of ethanol's dehydrating and precipitating action [19] [17]. This is a trade-off for its superior nucleic acid preservation. For display purposes where texture and color are critical, museums are experimenting with alternative fluids like fluorinated hydrocarbons, but these are not yet common in research laboratories [19].

Core Concepts: The Cold Chain and Molecular Integrity

What is the cold chain in the context of parasitology research?

The cold chain is an uninterrupted series of temperature-controlled storage and distribution activities designed to preserve the quality and integrity of biological materials, such as parasitic specimens. In parasitology education research, this ensures that samples like stool specimens remain viable for microscopic analysis, maintaining the morphological details of ova, cysts, larvae, and trophozoites for accurate identification and study [21] [22].

Why are time and temperature so critical for preserving parasitic specimens?

Temperature control is fundamental because exposure to unsuitable temperatures accelerates molecular degradation. Key molecular interactions affected include:

- Protein and Enzymatic Activity: Higher temperatures increase protease activity, leading to the breakdown of parasitic proteins and loss of morphological integrity [23].

- Water and Ice Transitions: During freezing, ice crystal formation can physically damage cellular structures. Rapid freezing or temperature fluctuations can cause ice crystals to expand and puncture cell membranes, destroying trophozoites and delicate cysts [23].

- Solute Exclusion: As water freezes, solutes are concentrated in the remaining liquid, creating a hypertonic environment that can denature proteins and disrupt cellular structures [23].

Time is a multiplier of these effects. The longer a specimen is exposed to a non-ideal temperature, the greater the cumulative damage, ultimately leading to loss of sample viability and unreliable research data [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: How can I prevent my wet mount preparations from drying out during microscopy sessions?

Problem: Conventional saline or iodine wet mounts dry out quickly, especially in tropical climates, making detailed observation and demonstration difficult [22].

Solution: Use a methylene blue-glycerol wet mount preparation.

Detailed Protocol:

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare a methylene blue-glycerol solution by mixing methylene blue dye with glycerol. A 25% glycerol concentration is effective for prolonging slide life [22].

- Slide Preparation: Place a drop of the methylene blue-glycerol solution on a clean microscope slide. Add a small, thick smear of fresh, unpreserved faecal specimen and mix gently. Place a coverslip over the mixture [22].

- Examination: Examine the entire preparation under low-power (10x) and high-power (40x) objectives [22].

Why it Works: Glycerol is hygroscopic, absorbing water molecules from the environment and preventing the mount from drying out. This provides a semipermanent preparation that can last for hours, compared to minutes for conventional mounts [22]. Methylene blue stains internal structures of parasites, providing excellent contrast and making them easier to identify against background debris [22].

FAQ: Our lab has experienced a temperature excursion in our ultra-low freezer. How do I assess the impact on stored specimens?

Problem: A freezer alarm indicates that stored samples, including purified nucleic acids from parasites, were exposed to elevated temperatures.

Solution: Execute a systematic impact assessment and triage plan.

Action Plan:

- Immediate Containment: Do not open the freezer door until the temperature has stabilized. If possible, transfer samples to a backup unit while assessing the primary unit [24].

- Data Review: Download and review data from the continuous temperature monitoring system. Determine the exact duration and magnitude of the temperature deviation [25] [24].

- Sample Triage:

- Check Stability Data: Refer to stability studies for the specific specimen types. The table below summarizes general risks, but lab-specific data is crucial.

- Prioritize High-Risk Samples: Identify samples most susceptible to degradation, such as RNA, proteins, or live cultures [23] [26].

- Perform Quality Control: Select a representative subset of samples for integrity testing (e.g., RNA Integrity Number (RIN) analysis, protein assays, or viability staining) before using them in critical experiments [23].

Table: General Risk Assessment for Specimens After Temperature Excursion

| Specimen Type | Typical Storage Temp. | Potential Impact of Transient Warming | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA / Viral RNA | -80°C or liquid nitrogen | High risk of degradation by RNases; loss of integrity for PCR [23] | Perform QC (e.g., Bioanalyzer); prioritize for re-extraction if QC fails. |

| DNA | -20°C to -80°C | Lower risk; potential for slow degradation over time [26] | Generally stable; check by gel electrophoresis or PCR if concerned. |

| Proteins | -80°C | Risk of aggregation, loss of activity, or protease degradation [23] | Test functionality with an activity assay or Western blot. |

| Fixed Parasite Ova/Cysts | 2-8°C (refrigerated) | Lower risk from short excursions; morphology may be preserved [22] | Inspect under microscope for morphological changes. |

| Live Parasites/Cultures | Specific culture conditions | High risk of death or reduced viability [26] | Assess viability and subculture immediately. |

FAQ: What are the most common failure points in the cold chain during sample transport, and how can we mitigate them?

Problem: Samples arrive at the testing lab with evidence of temperature abuse, compromising their usability.

Solution: Implement proactive risk management at identified failure points.

Mitigation Strategies:

- Failure Point: Loading/Unloading (Dispatch/Receipt)

- Failure Point: Last-Mile Delivery

- Failure Point: Temperature Abuse in Transit

Cold Chain Failure Points & Solutions

Experimental Protocols & Best Practices

Detailed Protocol: Preserving Parasitic Morphology with Methylene Blue-Glycerol Mounts

This protocol is adapted from a published study evaluating techniques for intestinal parasite identification [22].

Principle: A combination of methylene blue dye and glycerol provides superior staining contrast for morphological details and prevents the rapid drying of wet mounts, facilitating accurate identification of parasites.

Materials Required:

- Fresh, unpreserved faecal specimen

- Microscope slides and coverslips

- Methylene blue dye

- Glycerol

- Physiological saline

- Lugol's iodine (for comparison)

- Compound microscope

Methodology:

- Prepare Staining Solution: Mix methylene blue dye with glycerol to create a 25% v/v glycerol solution.

- Create Smears:

- Prepare a saline wet mount and an iodine wet mount for initial comparison.

- For the test mount, place a drop of the methylene blue-glycerol solution on a slide. Add a larger volume of faeces to create a thick smear and apply a coverslip.

- Microscopic Examination:

- Systematically examine all mounts first under low-power (10x) and then high-power (40x) objectives.

- Document the clarity of morphological features, staining of internal structures, and contrast against artefacts.

- Assess Drying Time: Monitor the slides at ambient temperature (e.g., 25 ± 2°C) and record the time taken for the edges of the mount to show signs of drying.

Expected Results: The methylene blue-glycerol mount should provide clearer visualization of internal structures compared to saline and iodine mounts. Helminthic ova and cysts will be stained deep blue, offering excellent contrast. The preparation should remain intact for several hours, significantly longer than conventional mounts which may dry in under 10 minutes [22].

Best Practice: Temperature Mapping Storage Equipment

Objective: To identify temperature variations (hot/cold spots) within a storage unit (refrigerator, freezer, ultra-low freezer) to ensure all stored specimens are maintained within the required temperature range.

Methodology:

- Sensor Placement: Place calibrated temperature data loggers at critical locations defined in guidelines like those from WHO or ISPE. This includes the top, middle, and bottom shelves, near the door, vents, and in the center of the unit [25] [28].

- Study Duration: Run the study for a sufficient period (typically 24-72 hours) to capture normal operational cycles, including door openings and defrost cycles [28].

- Data Analysis: Download the data and create a map of the unit. Identify any locations where temperatures fall outside the validated range.

- Action: Based on the results, define the usable storage volume within the unit. Place the most temperature-sensitive specimens in the most stable zones. Repeat the mapping periodically (e.g., annually) or after any significant equipment maintenance [25] [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Materials for Parasite Specimen Integrity

| Item | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Phase Change Materials (PCMs) | Maintain specific temp profiles (2-8°C, -20°C) during sample transport in passive shipping containers [27] [29]. | Must be pre-conditioned at the correct temperature before use to ensure performance [27]. |

| Cryogenic Vials | Long-term storage of samples at ultra-low temperatures (-80°C) or in liquid nitrogen vapor phase [26]. | Use screw-cap containers to prevent leakage and evaporation during long-term storage [26]. |

| Methylene Blue-Glycerol Solution | Creation of semi-permanent wet mounts for microscopy; provides contrast and prevents drying [22]. | A 25% glycerol concentration offers a good balance between preservation time and preventing morphological distortion [22]. |

| Vacuum-Insulated Packaging (VIP) | Provides superior thermal insulation for shipping high-value, temperature-sensitive specimens [27]. | Reduces thermal transfer from external conditions, extending the safe transit duration [27]. |

| IoT Data Loggers / Sensors | Continuous, real-time monitoring of temperature (and optionally humidity, shock) during storage and transport [27] [24]. | Enable proactive intervention via alerts; data is critical for regulatory compliance and investigating excursions [27] [25]. |

| Cryoprotectants | Chemicals (e.g., DMSO, Glycerol) added to cell suspensions or live parasites to protect against ice crystal damage during freezing [23]. | Must be optimized for specific cell types; often require controlled-rate freezing for maximum viability [23]. |

Parasite Specimen Handling Workflow

Optimized Preservation Protocols: A Practical Guide for Field and Laboratory Workflows

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core trade-off between using formalin and ethanol for preserving parasitology specimens? Formalin is generally superior for long-term morphological studies as it preserves tissue structure by forming protein cross-links, making it ideal for microscopic identification. However, these cross-links fragment DNA, rendering samples unsuitable for most molecular studies. Ethanol, while it may cause some tissue dehydration and shrinkage, preserves DNA integrity effectively, enabling downstream genetic analyses like PCR and DNA barcoding [30] [31].

Q2: Can ethanol-preserved samples still be used for reliable morphological identification? Yes, under the right conditions. One study found that while formalin-preserved samples yielded a greater diversity of parasitic morphotypes, parasites in ethanol-preserved samples were still morphologically identifiable even after more than a year of storage [30] [31]. The key is that identification remains possible, though the quality of preservation for certain larval forms may be higher in formalin.

Q3: My primary goal is DNA analysis. Is formalin ever an option? For standard genetic analyses, formalin is not recommended. Research shows that RNA yield from formalin-fixed tissues is negligible and the RNA that is recovered is highly fragmented [32]. In contrast, RNA from ethanol-fixed tissues shows integrity comparable to that from fresh frozen specimens, making it suitable for techniques like RT-PCR and cDNA microarrays [32].

Q4: What concentration of ethanol is optimal for preserving specimens for molecular studies? High concentrations (e.g., 95% or 96% ethanol) are recommended for initial field preservation to denature proteins that might degrade DNA [30] [31] [33]. For very long-term storage, 70% ethanol is often used and has been shown to maintain DNA effectively while minimizing tissue brittleness [34] [33].

Q5: Are there any safety considerations when choosing a preservative? Yes. Formalin contains formaldehyde, which is toxic and a known carcinogen. It requires careful handling to prevent inhalation or skin contact. Ethanol is less toxic but is flammable and requires appropriate storage and shipping precautions [30] [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor DNA Yield or Quality from Specimens

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Use of formalin as a preservative.

- Solution: For future studies, preserve a portion of the sample in 95% ethanol. For existing formalin-fixed samples, be aware that DNA will be fragmented and may only be suitable for specialized assays designed for damaged DNA [32].

- Cause: Ethanol concentration was too low or sample was not adequately submerged.

- Cause: Prolonged storage at room temperature in suboptimal preservative.

- Solution: One study found that holding samples in 95% ethanol for up to six months at room temperature did not adversely affect DNA barcoding success. For maximum longevity, store samples in 70-95% ethanol in a cool, dark place [33].

Problem: Degraded Morphology Making Microscopic Identification Difficult

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Preservation in ethanol, which can dehydrate and shrink tissues.

- Cause: Inadequate fixation time or volume of preservative.

Problem: Need to Perform Both Morphological and Molecular Analyses on a Single Sample

Solution: Ideally, partition the sample upon collection.

- Step 1: Divide the fresh sample into two halves.

- Step 2: Preserve one half in 10% formalin for morphological work.

- Step 3: Preserve the other half in 96% ethanol for molecular work. This is the methodology successfully employed in a comparative study of capuchin monkey parasites, allowing for direct comparison from the same host and time point [30] [31].

Data Presentation: Quantitative Comparisons

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Formalin vs. Ethanol for Parasite Preservation

| Preservation Metric | 10% Formalin | 96% Ethanol | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morphotype Diversity | Higher [31] | Lower [31] | Formalin revealed a greater number of distinct parasite types. |

| Parasites per Fecal Gram (PFG) | No significant difference [30] [31] | No significant difference [30] [31] | Both media were equally effective for quantifying parasite load. |

| Larval Preservation (e.g., Filariopsis) | Superior [31] | Good, but inferior [31] | Formalin better maintained larval cuticle and internal structures. |

| Egg Preservation (e.g., Strongyle-type) | Good [31] | Good, no significant difference [31] | Both media were equally effective for preserving eggs. |

| DNA Integrity | Poor (fragmented) [30] [32] | High (stable) [30] [33] | Ethanol is essential for PCR, sequencing, and other molecular methods. |

Table 2: Reagent Solutions for Parasite Preservation and Analysis

| Research Reagent | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 10% Buffered Formalin | Primary fixative for morphological microscopy; preserves helminth eggs, larvae, and protozoan cysts [20] [31]. | Toxic; requires careful handling and ventilation. Neutral buffered formalin helps prevent formalin pigment formation [34]. |

| 95% Ethanol | Primary preservative for molecular studies; denatures nucleases to protect DNA/RNA [31] [33]. | Flammable; may make tissues brittle. A 2:1 or 3:1 preservative-to-sample ratio is a minimum requirement [31]. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | A resin added to fixatives (often Schaudinn's) as an adhesive for stool material to slides for permanent staining [20]. | Often contains mercury; disposal can be problematic. Allows for specimen shipment at room temperature [20]. |

| Sodium Acetate-Formalin (SAF) | A mercury-free, all-purpose fixative suitable for both concentration techniques and permanent stained smears [20] [35]. | Has poor adhesive properties; may require albumin-coated slides for optimal smear preparation [20]. |

| 70% Ethanol | Long-term storage solution for both gross specimens and DNA; minimizes tissue brittleness compared to higher concentrations [34] [35]. | Effective for preserving worm specimens for later identification [36]. |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Comparative Preservation Study

The following protocol is adapted from a published study comparing preservation media in primate fecal samples [30] [31].

1. Sample Collection and Partitioning:

- Collection: Collect fresh fecal samples immediately after defecation.

- Partitioning: Using a sterile tool, halve the sample. Approximately 2 grams of one half is placed in a 15 ml tube containing 10 ml of 10% buffered formalin. The other 2-gram half is placed in a separate 15 ml tube containing 6 ml of 96% ethanol [31].

- Storage: Gently agitate tubes to ensure the sample is fully permeated by the preservative. Samples can be stored at ambient temperature for several months prior to analysis [30] [31].

2. Coprological Processing (Modified Wisconsin Sedimentation):

- Separation: Pour the contents of each tube through a strainer to separate solid fecal matter from the liquid preservative. Weigh the solid portion to determine the fecal weight.

- Homogenization and Straining: Homogenize the solids with distilled water and strain the solution through a double-layered cheesecloth.

- Sedimentation: Centrifuge the strained solution at 1500 RPM for 10 minutes. Discard the supernatant.

- Microscopy: Re-homogenize the pellet with 5-10 ml of distilled water and distribute it into a 6-well microscopy plate for screening [30] [31].

3. Parasite Identification and Degradation Grading:

- Microscopy: Screen samples using a standard microscope. Identify parasites based on established morphological characteristics (e.g., size, shape, shell thickness for eggs; internal and external structures for larvae) [31].

- Grading Scale: Use a customized 3-point scale to grade preservation:

- Score 3 (Well-preserved): Intact cuticle (larvae) or shell (eggs); clear internal and external structures; easy to identify.

- Score 2 (Moderately preserved): Minor degradation of cuticle/shell or internal structures; identification is still possible.

- Score 1 (Poorly preserved): Severe degradation; difficult or impossible to identify [31].

Experimental Workflow and Decision Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting a preservation method based on research objectives.

Preservation Method Decision Workflow

This workflow provides a logical guide for selecting the appropriate preservation medium based on your primary research objectives, ensuring sample integrity for your intended analyses.

In parasitology education research, the integrity of experimental data is fundamentally linked to the quality of specimen collection and preservation. Specimen deterioration poses a significant threat to diagnostic accuracy and research validity, potentially compromising morphological identification, molecular analysis, and ultimately, scientific conclusions. Standardized procedures for collecting adequate sample volumes and maintaining proper fixative-to-sample ratios are not merely procedural formalities but are critical determinants of research success. This technical support center provides targeted guidance and troubleshooting resources to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals prevent pre-analytical errors that can lead to specimen degradation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

General Specimen Collection

What is the most critical factor to consider when choosing a fixative? The choice of fixative depends on your downstream applications. No single solution is optimal for all techniques [37]. For projects requiring both concentration techniques and permanent stained smears, SAF (Sodium Acetate Formalin) is a good mercury-free option, though it has poor adhesive properties requiring albumin-coated slides for smear preparation [37]. If permanent stained smears are the priority, especially for protozoan trophozoites and cysts, PVA (Polyvinyl Alcohol) is highly recommended, but it may not concentrate some helminth eggs as effectively as formalin-based fixatives [37].

Our laboratory is receiving specimens with distorted parasite morphology. What could be the cause? This is often a result of improper fixation or delayed processing [38].

- Cause 1: The fixative-to-sample ratio is incorrect. An inadequate volume of fixative will not properly preserve the specimen.

- Solution: Ensure a 3:1 or 5:1 ratio of preservative to fecal material is used [37] [35]. For liquid specimens, a 3:1 ratio is specifically recommended for PVA [37].

- Cause 2: Specimens are not being mixed thoroughly with the fixative, leading to incomplete fixation.

- Solution: After placing the specimen in the fixative, mix well by stirring with an applicator stick to create a homogeneous solution. Allow it to stand for 30 minutes at room temperature for adequate fixation [37].

Specific Specimen Types

Why is the timing of collection so important for certain specimens like blood and urine? Parasites can exhibit periodic shedding or circadian rhythms, meaning their presence in certain specimens fluctuates throughout the day. Collecting at the optimal time maximizes the probability of detection [35].

Table 1: Optimal Collection Times for Various Specimen Types

| Specimen Type | Target Parasite(s) | Optimal Collection Time / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Blood | Plasmodium spp. (malaria) | Between paroxysms (chills/fever) [35] |

| Blood | Wuchereria bancrofti | Approximately midnight [35] |

| Blood | Loa loa | Approximately noon [35] |

| Urine | Schistosoma haematobium | Midday collection (peak egg excretion between 12-3 p.m.); collect terminal portion of urine [38] [35] |

| Perianal Sample | Enterobius vermicularis (pinworm) | 10-11 p.m. or upon waking, before a bowel movement [35] |

We need to ship parasitology specimens to a reference laboratory. What are the key considerations? Only preserved fecal specimens should be shipped to prevent specimen deterioration and reduce infection risk [37].

- Preservation: Use appropriate vials with adequate fixative (e.g., PVA or SAF) [37].

- Packaging: Follow universal regulations for shipping clinical specimens. Place the primary container into a sealed secondary container (e.g., metal sleeve or sealable bag), and then into a sturdy shipping container [37].

- Documentation: Ensure all specimens are accurately labeled and accompanied by required documentation.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: Validating Fixative Performance for Fecal Specimens

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating the enhancement of the Kato-Katz method using formalin-fixed stool [39].

Objective: To compare the quality of parasite morphology and slide background clarity between formalin-fixed and unfixed stool specimens.

Materials:

- Fresh stool specimen (naturally infected or artificially seeded with parasite eggs like Echinostoma or Opisthorchis viverrini)

- 10% formalin solution

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) or Normal Saline Solution (NSS) at various pH levels

- Glycerol with 3% malachite green

- Standard Kato-Katz kit materials (cellophane strips, template, sieve)

- Light microscope

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Divide the stool specimen into multiple aliquots.

- Fixation Groups:

- Group A (Unfixed): Process fresh stool immediately.

- Group B (Formalin-fixed): Fix stool with 10% formalin at a 1:1 ratio for varying durations (e.g., 1, 3, 6, 12, 24 hours, and 7 days) [39].

- Group C (Formalin-fixed + Glycerol): After formalin fixation, incubate samples with glycerol for 1 hour to enhance clearing [39].

- Processing: Process all groups using the standard Kato-Katz technique [39].

- Analysis:

- Examine slides under a light microscope (40x magnification).

- Score parasite egg morphology as "normal" or "irregular."

- Score slide background clarity on a scale (e.g., +1 to +3, where +3 represents the clearest background with minimal fecal debris) [39].

- Perform statistical analysis (e.g., paired sample t-test) to compare the performance between groups. A p-value of < 0.05 is considered statistically significant [39].

Visual Workflow of the Validation Protocol:

Protocol 2: Assessing DNA Preservation in Different Fixatives

For research involving molecular parasitology, preserving DNA integrity is paramount.

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of different preservatives in maintaining DNA integrity for long-term storage and molecular analysis.

Materials:

- Parasite samples (e.g., nematodes, protozoan cysts)

- Preservative solutions:

- DNA extraction kit

- Equipment for gel electrophoresis or bioanalyzer

Methodology:

- Preserve identical parasite samples in the different fixative solutions for a predetermined period (e.g., 6 months, 1 year).

- Extract DNA from all samples using a standardized protocol.

- Analyze the quality and quantity of the extracted DNA. Key metrics include:

- DNA Yield.

- Fragment Size (e.g., ability to amplify large DNA fragments >15 kb, which is well-preserved in DESS [40]).

- PCR Amplification Success for specific parasite genes.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Parasitology Specimen Preservation

| Reagent Solution | Primary Function | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SAF (Sodium Acetate Formalin) | All-purpose fixative for concentration and stained smears [37]. | Mercury-free; good for helminth eggs and protozoan cysts; long shelf life [37]. | Poor adhesive property; protozoan morphology with trichrome stain not as clear as with PVA [37]. |

| PVA (Polyvinyl Alcohol) | Fixative with adhesive for permanent stained smears [37]. | Excellent for protozoan trophozoites and cysts; allows specimen shipment [37]. | Contains mercury compounds; some helminth eggs not concentrated well [37]. |

| 10% Formalin | Fixative for helminth eggs and larvae; used in concentration techniques [37] [39]. | Good routine preservative; long shelf life; suitable for Kato-Katz enhancement [37] [39]. | Permanent stained smears cannot be prepared [37]. |

| DESS (DMSO/EDTA/NaCl) | DNA and morphological preservation at room temperature [40]. | Maintains high molecular weight DNA; effective for morphology in many species [40]. | Not effective for organisms with calcium carbonate structures [40]. |

| Schaudinn's Fluid | Fixative for preparing smears from fresh specimens [37]. | Designed for slide fixation; easily prepared [37]. | Not for concentration techniques; contains mercury compounds [37]. |

Logical Framework for Preservative Selection

The following diagram outlines a decision-making pathway for selecting the appropriate preservative based on research objectives, from primary analysis to long-term storage considerations.

In the field of parasitology, the integrity of specimens is paramount for accurate diagnosis, education, and research. The decline in traditional morphological expertise, coupled with the increasing scarcity of parasite specimens in developed regions due to improved sanitation, underscores the need for robust specimen preservation and analysis methods [41]. Without proper techniques, specimens deteriorate, leading to a loss of valuable educational resources and potential diagnostic inaccuracies. The Merthiolate-Iodine-Formalin (MIF) method is a time-tested parasitological technique that combines fixation and staining to preserve and facilitate the identification of a wide range of parasitic structures in fecal samples [42] [43]. This article establishes a technical support center for implementing MIF within multi-method systems, focusing on protocols, troubleshooting, and its role in preventing specimen deterioration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The successful application of the MIF technique relies on a specific set of reagents. The table below details the key components and their functions.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for the MIF Technique

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Thimerosal (Merthiolate) | Acts as a preservative and bactericidal agent [44]. | Part of the stock MIF solution [45]. |

| Formalin | Fixes and preserves parasitic structures (cysts, eggs, larvae) [43]. | A component of the stock solution; ensures long-term structural integrity [43]. |

| Lugol's Iodine Solution | Stains parasitic structures (e.g., cysts), aiding in microscopic visualization [43]. | Added immediately before use; provides both fixation and staining [43]. |

| Glycerin | Helps prevent distortion of parasitic structures [44]. | A component of the stock MIF solution [45]. |

| Standard MIF Kit | A commercial collection system containing the necessary preservatives. | Typically a two-vial system for comprehensive specimen preservation [43]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

MIF Staining Procedure: A Step-by-Step Guide

The following workflow outlines the standard procedure for preparing a fecal sample using the MIF method.

Detailed Methodology [45]:

- Sample Preparation: Thoroughly resuspend 3–5 grams of fecal material in 20 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Filtration: Filter the homogenate through a sieve mesh with a 250 µm diameter to remove large debris.

- Concentration: Transfer the filtered suspension to a 10 ml tube and centrifuge at 1,500 rpm for 10 minutes. Carefully discard the supernatant after centrifugation.

- MIF Solution and Staining: The MIF solution is typically prepared as two stock solutions that are combined just before use [44]:

- MIF A: Contains distilled water, thimerosal (1:1000), formaldehyde, and glycerin.

- MIF B: Contains distilled water and potassium iodide (to form Lugol's iodine). The sediment is then mixed with the freshly prepared MIF solution.

- Microscopy: A smear is prepared from the mixture and examined under a microscope. The iodine component stains cysts, eggs, and larvae, aiding in their identification.

MIF in a Multi-Method Diagnostic Framework

For comprehensive parasite recovery, MIF should be part of a larger diagnostic strategy. The diagram below illustrates its role alongside other techniques.

Performance Data and Comparison

To inform method selection, the quantitative performance of MIF against other common techniques is critical.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of MIF Against Other Diagnostic Methods

| Method | Primary Application | Relative Sensitivity for Helminths | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIF | Broad qualitative survey of helminths and protozoa | Competitive with Kato-Katz for helminths like Trichuris trichiura [46]. | Simplicity; cost-effectiveness; stains and fixes simultaneously; good for field surveys [46] [43]. | Iodine can interfere with other stains and may distort some protozoa; not ideal for permanent stained smears [43]. |

| Kato-Katz | Quantitative detection of soil-transmitted helminths | Higher sensitivity for Trichuris trichiura and low parasite loads [46]. | Allows egg quantification (eggs per gram); gold standard for epidemiologic surveys [46]. | Not suitable for protozoa; may miss high parasite loads [46]. |

| Direct Immunofluorescence (DFA) | Detection of specific protozoa like Giardia and Cryptosporidium | Not applicable for helminths. | High sensitivity and specificity for target protozoa; considered a gold standard for these pathogens [45]. | Requires a fluorescence microscope; higher cost; limited to specific pathogens. |

| Formalin-ethyl Acetate Sedimentation | General concentration of parasites | Good recovery of helminth eggs and larvae, and protozoan cysts [42] [43]. | An all-purpose concentration method; excellent morphology preservation; suitable for immunoassays [43]. | Inadequate for trophozoite preservation [43]. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common MIF Procedure Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor staining of cysts/nuclei | Degraded or outdated Lugol's iodine solution. | Prepare fresh Lugol's solution immediately before use [43]. |

| Distorted protozoan morphology | Over-exposure to iodine or improper fixation. | Ensure the ratio of fecal sample to MIF is correct (1:3 to 1:5) and do not let smears sit too long before reading [43]. |

| Difficulty identifying Cryptosporidium | Method is not specific for this parasite; oocysts are very small. | Use modified acid-fast staining or, preferably, DFA or PCR for specific detection [45] [43]. |

| Low diagnostic sensitivity | Low parasitic load in a single sample. | Examine multiple specimens collected at 2-3 day intervals [43]. |

| Inconsistent results | Inadequate mixing of stool with preservative. | Ensure the specimen is thoroughly mixed with the MIF solution to guarantee uniform fixation and staining [43]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does MIF compare to PVA for preserving protozoan cysts for morphological study? A1: While MIF is excellent for field surveys and combined fixation/staining, low-viscosity Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) is generally superior for creating permanent stained smears (e.g., with Trichrome stain) for detailed cytological study of protozoan trophozoites and cysts [43]. However, PVA has disadvantages, such as containing mercuric chloride and being unsuitable for concentration procedures [43].

Q2: Can MIF-preserved samples be used for molecular testing like PCR? A2: This is generally not recommended. Iodine can interfere with PCR. For molecular studies, other preservatives like Sodium Acetate-Acetic Acid-Formalin (SAF) or specific one-vial, non-mercuric fixatives are more suitable [43].

Q3: What is the "refugia" concept and how does it relate to diagnostic methods? A3: While primarily discussed in veterinary parasitology and anthelmintic resistance management, "refugia" refers to the portion of a parasite population not exposed to a drug, thereby maintaining genetic diversity and susceptible genes [47]. From a diagnostic perspective, using highly sensitive methods like MIF helps accurately monitor parasite prevalence and intensity, which is crucial for making informed decisions about targeted treatment strategies that can preserve refugia and slow resistance development.

Q4: Why is MIF particularly valuable in a resource-limited or educational setting? A4: MIF is simple, inexpensive, and has a long shelf life [46] [43]. Its ability to both fix and stain in a single step reduces the need for multiple reagents and complex procedures. For educational purposes, this allows for the creation of stable, long-term reference material, which is crucial as physical specimens become increasingly scarce in regions with improved sanitation [41].

Q5: What are the key advantages of MIF over the Kato-Katz technique? A5: The primary advantage is its broader scope. While Kato-Katz excels at quantifying key soil-transmitted helminths, MIF is also effective at detecting other helminths like Strongyloides stercoralis and, importantly, intestinal protozoa, for which the Kato-Katz technique is not suitable [46].

Troubleshooting Guides

DNA Degradation in Long-Term Storage

Problem: DNA samples show signs of degradation during long-term storage, leading to poor PCR amplification results.

Solutions:

- For silica gel-desiccated filters: For storage beyond one month, transfer samples to -20°C. While silica gel prevents degradation well for up to one month at a range of temperatures (18°C, 4°C, or -20°C), only storage at -20°C prevents a noticeable decrease in detectability at 5 and 12 months [48].

- For ethanol-preserved samples: Ensure initial preservation is done with 95% ethanol, which provides better penetration and nuclease deactivation compared to lower concentrations [49]. Samples can remain stable for at least 60 days at 4°C [49].

- Confirm drying efficiency: When using silica beads, ensure they are actively drying by checking color indicators. Inadequate drying capacity leads to residual moisture and DNA degradation [50].

Insufficient DNA Yield After Preservation

Problem: Low DNA concentration or purity after extraction from preserved samples.

Solutions:

- Check preservation ratios: For 95% ethanol preservation, maintain a minimum 2:1 volumetric ratio of ethanol to sample. While a 5:1 ratio is often recommended, studies show successful DNA barcoding can be achieved with a 2:1 ratio [33].

- Add mechanical disruption: For difficult samples like soil-transmitted helminth eggs in stool, incorporate a bead-beating step during DNA extraction to break down rigid egg shells, which substantially improves DNA recovery [51].

- Optimize precipitation: When concentrating DNA by precipitation, use 0.6-0.7 volumes of room-temperature isopropanol for large sample volumes or low DNA concentrations. Ensure thorough mixing and adequate centrifugation [52].

Preservation Method Selection for Field Conditions

Problem: Choosing between 95% ethanol and silica bead desiccation for specific field conditions.

Solutions:

- Assess temperature conditions: At elevated temperatures (e.g., 32°C), silica bead desiccation outperforms ethanol preservation by preventing progressive decreases in eDNA sample quality [48]. A two-step process using 90% ethanol overnight followed by silica-based desiccation has proven effective for hookworm DNA preservation in stool at 32°C [49].

- Consider transport regulations: Ethanol is flammable and classified as hazardous, complicating transportation. Silica gels pose fewer safety concerns [33].

- Evaluate sample type: For phyllosphere samples, silica gel packs effectively preserve microbial community DNA for metabarcoding analyses at ambient temperatures [53]. For fecal specimens, 95% ethanol often provides the most pragmatic choice considering toxicity, cost, and effectiveness [49].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Which preservation method offers better DNA stability for long-term storage: 95% ethanol or silica beads?

A: The optimal method depends on storage temperature and duration:

- For storage up to one month: Both methods perform well across a range of temperatures (18°C to -20°C) [48].

- For storage beyond one month at room temperature: Silica gel desiccation demonstrates superior performance by preventing progressive decreases in eDNA quality [48].

- For long-term storage (>1 year): Silica gel preservation at -20°C maximizes sample integrity [48].

- At consistent 4°C: Both methods show comparable effectiveness for at least 60 days [49].

Q2: What is the minimum ethanol-to-sample ratio needed for effective DNA preservation?

A: A 2:1 volumetric ratio of 95% ethanol to sample is sufficient for successful DNA preservation and downstream molecular applications, as demonstrated in DNA barcoding studies with benthic macroinvertebrates. While higher ratios (5:1) are often recommended, the 2:1 ratio provides effective preservation while reducing logistical constraints [33].

Q3: How can I regenerate silica gel beads for reuse in DNA preservation?

A: Silica gel beads can be regenerated by heating:

- Oven method: Heat at 200-250°F (93-121°C) for 1-2 hours [50].

- Microwave method: Heat on defrost setting for 1.5-5 minutes, but avoid overheating which can damage beads [50].

- Important precautions: Never microwave cobalt chloride-containing (blue) beads due to toxicity concerns. Use only clear or orange indicator beads in microwaves, and preferably use non-indicating beads for this application [50].

Q4: How does temperature fluctuation during field transport affect DNA preserved with different methods?

A: Silica gel desiccation provides more consistent DNA preservation quality under temperature fluctuations:

- Silica gel beads: Maintain DNA detection stability even at 23°C/32°C, preventing the progressive decrease in sample quality observed with ethanol at elevated temperatures [48] [49].