Parasites in Wildlife Disease Ecology: From Ecological Roles to One Health Interventions

This article synthesizes current research on the multifaceted roles of parasites in wildlife disease ecology, addressing a professional audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development specialists.

Parasites in Wildlife Disease Ecology: From Ecological Roles to One Health Interventions

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the multifaceted roles of parasites in wildlife disease ecology, addressing a professional audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development specialists. It explores the foundational ecological principles of parasitism, including their critical functions in trophic interactions, population regulation, and biodiversity maintenance. The content delves into advanced methodological approaches such as social network analysis and long-term ecological monitoring for studying parasite transmission. It further examines the ecological consequences of parasite removal and the challenges of drug-induced environmental impacts, framed within the One Health context. Finally, the article evaluates innovative therapeutic strategies, including natural product discovery and computational biology, for managing parasitic diseases while considering ecosystem sustainability.

The Unseen Regulators: Ecological Roles of Parasites in Wildlife Populations and Ecosystems

Within the framework of wildlife disease ecology, parasites, traditionally viewed through a pathological lens, are increasingly recognized as critical mediators of ecosystem structure and stability. This whitepaper synthesizes evidence establishing parasites as keystone species whose impacts are disproportionately large relative to their biomass. Through direct regulation and indirect trait-mediated effects, parasites dictate community composition, influence energy flow, and modulate biodiversity. This document presents a quantitative analysis of these impacts, details standardized methodologies for their study, and proposes essential tools for a research framework integrating parasitology into ecosystem-level analysis. The objective is to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a technical foundation for investigating parasite roles in ecological networks, thereby informing conservation strategies and public health initiatives.

The keystone species concept, originally demonstrated in predator-prey dynamics, describes a species with a disproportionate influence on ecosystem structure and function relative to its abundance [1]. A growing body of evidence extends this concept to parasites, entities traditionally overlooked in ecosystem models. Parasitism represents the most widespread consumer strategy in nature, and its ecological impacts can equal or surpass those of free-living organisms [2].

Parasites function as keystone species through several mechanistic pathways: they can regulate host population densities, alter host behavior and physiology, and mediate competitive outcomes between species, a process known as parasite-mediated competition [2] [3]. These interactions can ultimately dictate community composition, energy flow through food webs, and overall ecosystem stability. The study of these dynamics is no longer a purely academic pursuit; it is critical for predicting ecosystem responses to change, managing wildlife diseases, and understanding the ecological consequences of pharmaceutical interventions in both domestic and wild animal populations.

Ecological Mechanisms of Keystone Parasites

Parasites exert their keystone influence through a variety of direct and indirect mechanisms. Understanding these pathways is essential for designing targeted ecological studies and interpreting their outcomes.

Direct and Indirect Effects on Host Populations

The impact of parasitism on community structure can be categorized into three primary modes of action [3]:

- Direct Effects: Parasites can directly reduce host survival and fecundity, thereby regulating host population sizes. When this impact is asymmetrical across host species, it can alter the competitive hierarchy within a community.

- Density-Mediated Indirect Effects: By reducing the population density of a host species that is a keystone predator or competitor, a parasite can initiate a trophic cascade, indirectly affecting the abundance and distribution of other species in the community.

- Trait-Mediated Indirect Effects: Even without significant mortality, parasites can alter host phenotypes, including behavior, morphology, and physiology. These changes can modify the host's ecological role, for instance, by increasing its susceptibility to predation or altering its foraging efficiency, thereby indirectly affecting other species in the ecosystem.

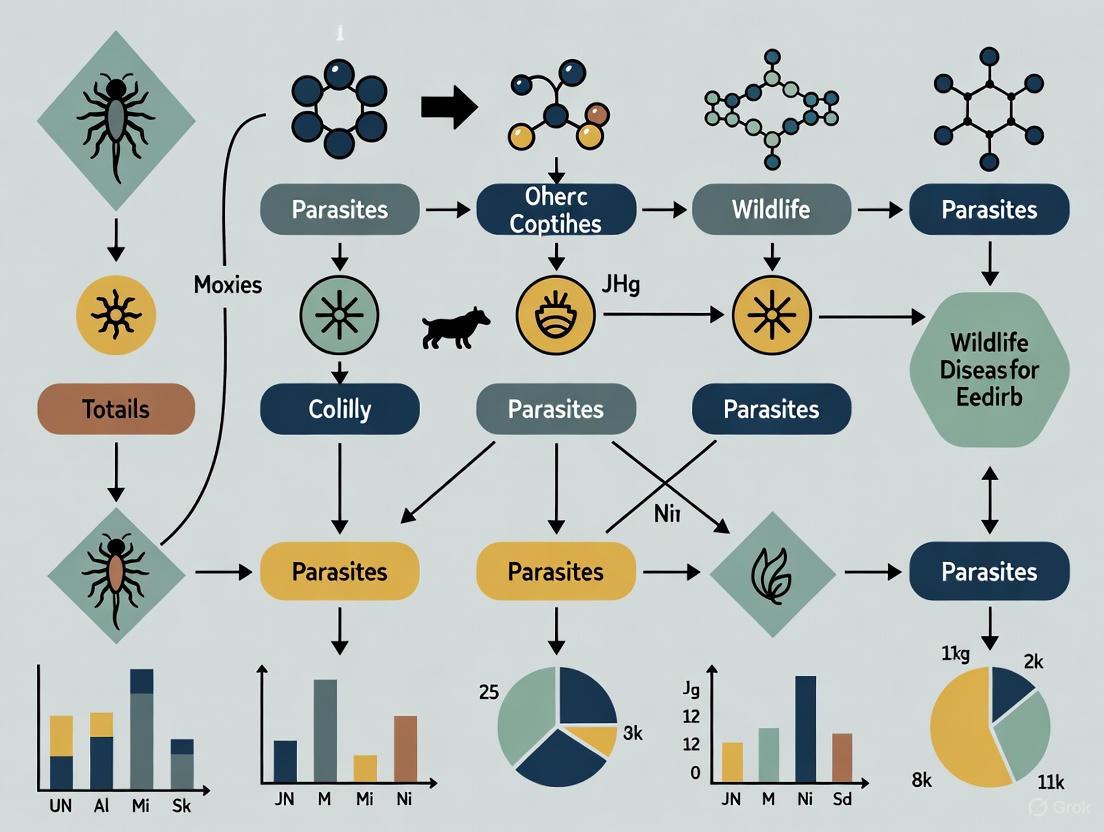

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and pathways through which parasites act as keystone species, integrating these direct and indirect mechanisms.

Figure 1: Conceptual framework of parasite keystone effects. This diagram outlines the primary pathways—direct, density-mediated, and trait-mediated indirect effects—through which parasites influence ecosystem structure and biodiversity.

Parasite-Mediated Competition and Biodiversity

A quintessential keystone effect of parasites is their ability to modulate competition between host species, a process termed parasite-mediated competition [2]. The outcome of this process can either increase or decrease local biodiversity, depending on which host species is most affected.

- Reducing Biodiversity: Invasions can be facilitated when a parasite disproportionately affects a native species. In Britain, the introduced grey squirrel is a reservoir for the Squirrelpox Virus (SQPV), which is highly virulent to the native red squirrel. This parasite-mediated competition has driven the decline of red squirrels, reducing biodiversity [2] [3].

- Enhancing Biodiversity: Conversely, parasites can promote coexistence by suppressing a competitively dominant species. On the Caribbean island of St. Maarten, the malarial parasite Plasmodium azurophilum more severely affects the competitively dominant lizard Anolis gingivinus. This reduces its competitive advantage, allowing the inferior competitor Anolis wattsi to coexist, thereby maintaining higher species diversity [2].

Quantitative Analysis of Ecosystem-Wide Impacts

The following case studies provide quantitative evidence of the profound ecosystem-level changes driven by parasitic infections. The data are synthesized into tables for clear comparison of impacts across different ecosystems.

Case Study 1: Rinderpest Virus in African Ungulates

The introduction and subsequent eradication of the rinderpest virus in Africa represents a large-scale, unintentional experiment demonstrating the keystone role of a pathogen [2] [3].

Table 1: Ecosystem impacts of rinderpest virus introduction and eradication in Africa.

| Ecosystem Component | Impact of Virus Introduction (c. 1890) | Impact of Virus Eradication (c. 1950s) |

|---|---|---|

| Virus & Host | Introduced via domestic livestock; spread continent-wide in ~10 years [3]. | Widespread vaccination led to local eradication [3]. |

| Primary Host Populations | Drastic reduction in populations of buffalo, wildebeest, and other native ungulates [2] [3]. | Populations of wild ungulates recovered significantly [3]. |

| Trophic Cascades | Altered grazing pressure on primary producers [3]. | Recovery of ungulate populations changed plant community structure [3]. |

| Predator Communities | Predators relying on ungulates as prey were impacted [3]. | Predator communities recovered with increased prey availability [3]. |

| Ecosystem Structure | Disruption of the entire grassland ecosystem [3]. | Shift back towards a pre-rinderpest ecosystem state [3]. |

Case Study 2: Microbial Pathogens of Diadema Urchins

A mass mortality event of the long-spined sea urchin Diadema antillarum in the Caribbean provides a stark example of a parasite acting on a keystone herbivore [2].

Table 2: Impacts of the Diadema urchin mass mortality event on Caribbean coral reefs.

| Ecosystem Metric | Pre-Outbreak State | Post-Outbreak State | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parasite/Pathogen | Presumed absence of a virulent pathogen. | Mass die-off associated with microbial pathogens. | [2] |

| Keystone Host (Diadema) | High population density; intense grazing on reefs. | Populations eliminated or severely reduced. | [2] |

| Trophic Cascade (Algae) | Algal cover kept low (~1%) by urchin grazing. | Algal cover increased dramatically to ~95%. | [2] |

| Ecosystem Engineers (Corals) | Mature corals dominant; new coral settlement possible. | Algae displaced mature corals and prevented new settlement. | [2] |

| Ecosystem State | Coral-dominated ecosystem. | Algae-dominated ecosystem; reduced biodiversity. | [2] |

Case Study 3: Trematode Parasites in Aquatic Food Webs

Trematode parasites in estuarine systems demonstrate that parasites can contribute significantly to ecosystem energetics, with biomass comparable to that of top predators [2].

Table 3: Quantitative measures of parasite impact in estuarine and grassland ecosystems.

| Ecosystem & Location | Parasite Group | Key Quantitative Finding | Ecological Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estuarine System, California | Trematodes | Yearly parasite productivity was higher than the biomass of birds. [2] | Parasites are major contributors to energy flow, challenging the traditional Eltonian pyramid. |

| Salt Marsh, California | Parasites (general) | Parasites were involved in 78% of all trophic links; increased food web connectance by 93%. [2] | Parasites dramatically increase food web complexity, which may influence stability. |

| Grassland, Minnesota | Plant fungal pathogens | Biomass of fungal pathogens was comparable to that of herbivores. [2] | Parasites can exert top-down control on primary producers rivaling that of herbivores. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

To ground the theoretical framework in empirical science, this section details the methodologies underpinning key studies cited in this whitepaper.

Documenting Parasite-Induced Trophic Cascades

Objective: To quantify the ecosystem-wide effects of a parasite that regulates a keystone host species. Methodology Overview: This approach combines long-term ecological monitoring, manipulative experiments, and historical data analysis, as exemplified by research on the rinderpest virus [3] and Diadema urchins [2].

Baseline Data Collection:

- Host Population Surveys: Conduct standardized transect or aerial surveys to establish population densities of the keystone host and other community members before and after a parasite introduction or eradication event.

- Ecosystem State Assessment: Measure relevant ecosystem metrics (e.g., algal cover on reefs, grassland plant biomass, tree recruitment) using quadrant sampling or remote sensing.

Parasite Monitoring:

- Pathogen Surveillance: Collect host tissue, blood, or environmental samples (e.g., water, soil) for molecular analysis (e.g., PCR) to detect and quantify parasite presence and load [4].

- Serological Testing: Use assays like ELISA to screen host populations for pathogen antibodies, providing data on exposure history and herd immunity [4].

Data Integration and Causal Inference:

- Comparative Analysis: Statistically compare ecosystem states before, during, and after the parasite's impact. Control sites (where the parasite is absent) are crucial for establishing causality.

- Pathway Modeling: Use structural equation modeling (SEM) or similar statistical techniques to test the strength of causal pathways linking parasite presence to host decline and subsequent ecosystem changes.

Investigating Trait-Mediated Indirect Effects

Objective: To determine how parasite-induced alterations in host phenotype influence trophic interactions and community structure. Methodology Overview: This involves controlled laboratory and field experiments to isolate the effects of parasite infection on host behavior and its ecological consequences, as demonstrated in trematode-infected killifish and amphibians [2].

Host Phenotype Characterization:

- Behavioral Assays: Compare the behavior of infected vs. uninfected hosts in controlled arenas. Key metrics include:

- Activity Level: Measured via movement tracking software.

- Predator Avoidance: Assessed by recording response to simulated predator attacks (e.g., model birds).

- Foraging Efficiency: Quantified as food consumption rate in a standard timeframe.

- Morphological Assessment: Document parasite-induced physical deformities (e.g., limb malformations in amphibians) through morphometric analysis and imaging.

- Behavioral Assays: Compare the behavior of infected vs. uninfected hosts in controlled arenas. Key metrics include:

Quantifying Ecological Consequences:

- Predation Risk Experiment: In mesocosms (controlled outdoor tanks) or natural enclosures, introduce a known number of infected and uninfected hosts along with their natural predators. Monitor and compare predation rates on each group over a set period (e.g., 24-48 hours). The 30x higher susceptibility of infected killifish to bird predators was quantified this way [2].

Field Validation:

- Population Correlation: Survey natural populations to correlate local parasite prevalence with the abundance of the predator species that relies on trophic transmission, providing real-world validation of experimental findings.

The experimental workflow for investigating trait-mediated effects is visualized below.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for trait-mediated effects. This flowchart outlines the key steps, from laboratory phenotyping to field validation, for investigating how parasite-induced changes in host phenotype create ecosystem-level effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Solutions

Advancing the study of parasites as keystone species requires a multidisciplinary toolkit. The following table details essential reagents, technologies, and methodologies critical for experimental and observational research in this field.

Table 4: Essential research reagents and solutions for studying wildlife parasites and their ecosystem impacts.

| Category / Item | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Diagnostics | PCR, qPCR, ELISA | Detecting and quantifying parasite presence, load, and host immune response in tissue, blood, or environmental samples. [4] |

| Sample Collection & Preservation | RNAlater, Ethanol, Sterile Swabs, Fecal Collection Kits | Preserving host and pathogen genetic material and antigen integrity during field collection and storage. [4] |

| Field Monitoring & Tracking | GPS, Camera Traps, Acoustic Recorders, Drones | Monitoring host population density, behavior, and spatial distribution non-invasively at the landscape level. |

| Data Standardization | FAIR Data Principles, Darwin Core Standards | Ensuring collected data are Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable; critical for meta-analyses and global health security. [4] |

| Microbiome Analysis | 16S rRNA Sequencing, Metagenomics | Characterizing the gut or skin microbiome of hosts to understand its role in health, disease susceptibility, and response to anthelmintics. [5] |

The evidence presented solidifies the role of parasites as potent keystone species capable of dictating ecosystem structure, function, and biodiversity. Moving forward, the field of wildlife disease ecology must integrate several key priorities. First, the widespread adoption of minimum data standards is paramount to ensure that wildlife disease data are transparent, reusable, and globally interoperable, thereby enhancing our early warning systems for emerging zoonotic threats [4]. Second, research must expand beyond single-host, single-parasite systems to embrace the complexity of the host microbiome, understanding how these microbial communities influence host health, parasite susceptibility, and the efficacy of pharmaceutical treatments [5]. Finally, there is a critical need to move from observation to prediction by developing models that can forecast ecosystem outcomes following parasite introductions or control measures. By incorporating parasites into the core of ecological theory and practice, researchers, conservationists, and drug development professionals can better anticipate and mitigate the wide-ranging consequences of pathogen dynamics in a changing world.

Parasites represent a critical, yet often overlooked, component of ecosystem structure and function. Framing parasitic interactions within the established principles of trophic ecology reveals their dual roles as both consumers (predators) and resources (prey) within complex food webs. This whitepaper examines parasites not merely as pathogens, but as integral trophic nodes that influence energy flow, population dynamics, and community organization. Understanding these interactions is fundamental to wildlife disease ecology, as it provides a mechanistic framework for predicting how parasites affect host fitness, regulate populations, and respond to environmental change. The One Health perspective underscores that parasitic relationships are mediated by complicated ecological, socioeconomic, and behavioral factors operating at the human-animal-environment interface [6]. This document synthesizes current research and methodologies to provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a technical guide for quantifying and modeling parasitic interactions within trophic networks.

Quantitative Framework: Parasite Energetics and Trophic Transfer

The integration of parasites into food webs necessitates a quantitative understanding of their energetic demands and the efficiency with which they are transmitted between hosts. The foundational concept of energy transfer between trophic levels, where typically only 10% of energy is transferred from one level to the next, provides a critical lens through which to view parasite population dynamics and their ecosystem impacts [7].

Parasite-Mediated Energy Flow

Parasites, like free-living consumers, require energy from their hosts for survival and reproduction. This energy derivation represents a diversion of host resources, which can reduce host growth, reproduction, and survival. The table below summarizes key quantitative relationships in parasite trophic dynamics, illustrating the dose-dependent nature of infections and the resultant energetic costs to hosts.

Table 1: Quantitative Relationships in Parasite Trophic Dynamics

| Host-Parasite System | Key Quantitative Relationship | Experimental Findings | Ecological Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daphnia magna-Pasteuria ramosa [8] | Dose-dependent infection probability following a host heterogeneity model | Among 14 host clone-parasite isolate combinations, 5 showed pronounced dose-dependency; best fit to a model accounting for non-inherited phenotypic differences in host susceptibility | Challenges mass-action principle; highlights importance of individual host heterogeneity in disease outcomes |

| General Trophic Theory [7] | 10% energy transfer rule between trophic levels | Of the energy at one trophic level, only ~10% is available to the next level; explains why food chains are typically limited to 4-5 levels | Parasites, as consumers, further reduce the net energy available to the host for growth and reproduction, potentially shortening viable food chain length |

| Zoonotic Parasites (e.g., Echinococcus multilocularis, Sarcoptes scabiei) [6] | Prevalence linked to ecological drivers and host density | Fox feces density (and parasite prevalence) correlated with vegetation and proximity to urban centers; camel-to-human transmission poses occupational risk | Parasites act as sentinels of ecosystem health, with transmission dynamics modified by land use and wildlife-livestock-human interfaces |

Trophic Transmission and Food Web Links

Many parasites rely on predator-prey interactions for transmission, creating explicit trophic links. For instance, a trophically transmitted parasite encysts in the tissue of an intermediate host (prey), which must be consumed by a definitive host (predator) to complete the life cycle. This positions the parasite as both prey (for the definitive host) and a predator (exploiting the intermediate host). The quantitative relationship between parasite dose and infection probability, as demonstrated in the Daphnia-Pasteuria system, is central to modeling the strength of these trophic links [8].

Experimental Protocols: Quantifying Parasite Trophic Roles

Robust experimental design is essential for elucidating the mechanisms governing parasite trophic interactions. The following protocols provide a framework for investigating dose-response relationships and transmission dynamics in both laboratory and field settings.

Protocol 1: Dose-Response Infection Assay

This laboratory-based protocol is designed to quantify the relationship between parasite exposure dose and the probability of successful host infection, moving beyond the simple mass-action assumption [8].

Objective: To determine the infection probability across a gradient of parasite doses and identify the best-fit mathematical model (e.g., mass-action, parasite antagonism, host heterogeneity) for the relationship.

Materials:

- Subjects: Genetically defined host clones (e.g., Daphnia magna water fleas) [8].

- Pathogen: Standardized parasite isolate (e.g., bacterial endoparasite Pasteuria ramosa) [8].

- Equipment: Multi-well tissue culture plates, micropipettes, environmental growth chambers, microscope.

Methodology:

- Parasite Dilution Series: Prepare a logarithmic dilution series of the parasite inoculum (e.g., 8 different doses) in a sterile medium.

- Host Exposure: Randomly assign individual hosts from multiple clones to each dose treatment group. Expose each host to a defined volume of the parasite suspension.

- Control Groups: Maintain control hosts exposed to a sterile medium.

- Incubation and Monitoring: Maintain all hosts under standardized environmental conditions (temperature, photoperiod, food supply). Monitor hosts daily for mortality and signs of infection.

- Endpoint Assessment: After a predetermined period, dissect hosts or use diagnostic tools (e.g., microscopy, PCR) to confirm infection status.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the fraction of infected hosts at each dose level. Use a likelihood approach to compare the fit of different mathematical models (mass-action, antagonism, host heterogeneity) to the observed dose-infection data [8].

Protocol 2: Field Surveillance of Trophic Transmission

This protocol leverages field observation and molecular tools to track parasites across the wildlife-domestic interface, a key frontier in the One Health framework [6].

Objective: To document parasite presence, prevalence, and genotype sharing between wildlife, livestock, and environmental sources (e.g., water) to infer trophic transmission pathways.

Materials:

- Sample Collection: Sterile swabs, fecal collection kits, water sampling equipment, GPS units.

- Sample Storage: Liquid nitrogen or dry ice for field transport, -80°C freezers for long-term storage.

- Laboratory Analysis: DNA/RNA extraction kits, PCR thermocyclers, primers for specific parasites (e.g., Echinococcus, Cryptosporidium, Enterocytozoon bieneusi), sequencing equipment.

Methodology:

- Site Selection: Choose study sites based on ecological gradients (e.g., urban-rural, varying vegetation) and known host density [6].

- Sample Collection: Systematically collect fecal samples from target wildlife (e.g., foxes, rodents, Tibetan antelope) and sympatric livestock [6]. Collect water samples from shared water sources.

- Environmental Data: Record GPS coordinates, habitat type, and proximity to human settlements for each sample.

- Laboratory Processing: Extract genetic material from all samples. Use PCR and sequencing to identify parasite species and genotypes.

- Data Integration: Construct a matrix of parasite genotypes across host species and environmental samples. Analyze the distribution to identify shared genotypes, which indicate potential cross-species transmission and trophic interactions (e.g., predation, scavenging). Statistical models (e.g., network analysis) can then be used to infer the most likely transmission pathways.

Visualization of Parasite Trophic Networks

Diagrams are essential for conceptualizing the complex roles parasites play in food webs. The following Graphviz-generated diagram illustrates a simplified trophic network incorporating parasitic interactions.

Diagram 1: Parasite-Integrated Trophic Network. This diagram depicts a food web where parasites (ellipses) are integrated as nodes. Solid arrows represent traditional energy flow (predation, grazing), while colored dashed/dotted arrows represent parasitic relationships (infection, trophic transmission). Note the dual role of the Tissue Parasite, which is prey for the Carnivore and a predator of the Herbivore. The Hyperparasite illustrates a parasite that itself becomes prey.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Cutting-edge research into parasite trophic ecology relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key materials for the experimental protocols outlined in this guide.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Parasite Trophic Ecology

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Use Case Example |

|---|---|---|

| Genetically Defined Host Clones [8] | Controls for host genetic background in experiments; allows dissection of genetic vs. non-genetic susceptibility. | Dose-response infection assays using Daphnia magna clones to model host heterogeneity [8]. |

| Standardized Parasite Isolates [8] | Provides a consistent, quantifiable source of parasites for experimental challenges. | Preparing dilution series for dose-response experiments with the bacterial endoparasite Pasteuria ramosa [8]. |

| Species-Specific PCR Primers | Enables detection and identification of parasites from complex field samples with high sensitivity and specificity. | Identifying Echinococcus multilocularis in fox feces or Pentatrichomonas hominis in Tibetan antelope samples during field surveillance [6]. |

| Computational Biology Tools (Virtual Screening) | Identifies potential drug targets or inhibitory compounds against parasitic pathogens through in silico methods. | Screening for effective inhibitors (e.g., ZINC67974679) against Rickettsia felis via virtual screening and docking analysis [6]. |

| Natural Compound Libraries | Source of novel therapeutic agents with potential anti-parasitic activity for drug repurposing and development. | Evaluating the anti-cryptosporidial effect of eugenol or the use of artesunate against Babesia microti [6]. |

The integration of parasites into food web ecology is not merely an academic exercise; it is a necessary step for developing a predictive understanding of ecosystem dynamics and disease risk. By quantifying their roles as both predators and prey, we can better model energy flows, appreciate their function in regulating host populations, and anticipate the ecological consequences of their removal or introduction. Future research must prioritize cross-sectoral collaboration, combining molecular biology, field ecology, computational science, and veterinary epidemiology to build a holistic understanding [6]. Furthermore, building diagnostic and research capacity in low-resource environments, where parasitic burdens are often highest, is an essential component of the global One Health agenda. As climate change and habitat alteration shift the ranges and interactions of hosts and parasites, the framework outlined here will be critical for mitigating emerging threats to wildlife, domestic animal, and human health.

Understanding the mechanisms that regulate species coexistence and maintain biodiversity is a fundamental objective in ecology. This complex interplay dictates population dynamics, community structure, and ecosystem function. The traditional framework for investigating these processes has centered on competition for abiotic resources and predation. However, a paradigm shift is underway, recognizing that a complete understanding requires integrating the pivotal, yet often overlooked, role of parasites and pathogens [6]. These organisms are not merely passengers but active mediators of ecological interactions, influencing competition, driving evolutionary adaptations, and altering habitat use. Their effects resonate across scales, from regulating individual host populations to shaping entire community assemblages and ecosystem stability. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the mechanisms by which competition and its mediators, with a specific focus on parasites, structure biodiversity, framed within modern wildlife disease ecology research.

Theoretical Foundations of Competition and Coexistence

The conceptual models explaining species coexistence and population regulation provide the foundation for empirical research. The dominant theories highlight distinct mechanistic pathways.

Niche-Based Competition vs. Ecological Neutrality

A long-standing paradigm posits that species coexist by occupying distinct ecological niches, thereby minimizing direct competition. This limiting-similarity competition predicts that assemblages will be composed of species with dissimilar trait values, reflecting their differential use of resources, space, or time [9]. In contrast, the neutral theory explores the structure of communities under the assumption of ecological equivalence, where species exhibit community drift dynamics analogous to genetic drift [10]. The critical distinction lies in the mechanisms of population regulation: community drift emerges only when the density-dependent effects of each species on itself are identical to its effects on every other guild member. If each species limits itself more than it limits others, coexistence is possible even among functionally similar species [10].

Trait-Mediated Interactions and Hierarchical Competition

Mounting evidence suggests that absolute trait dissimilarity does not solely reflect niche differences. Hierarchical differences in trait values can distinguish competitive abilities for a common resource, leading to trait-mediated hierarchical competition [9]. For instance, an invasive species might succeed not by exploiting a different niche, but by possessing superior traits (e.g., larger body size, higher thermal tolerance, or greater aggression) that allow it to outcompete natives for shared resources. The resulting community patterns are complex, with some traits showing overdispersion (driven by limiting similarity) and others showing clustering (driven by environmental filtering or hierarchical competition) [9]. This necessitates a multi-trait approach to accurately infer assembly processes.

Parasites as Key Mediators in Ecological Networks

Parasites are integral components of ecosystems, acting at the interface of human, animal, and environmental health—the core of the One Health framework [6]. Their influence on competition and biodiversity is multifaceted and profound.

Table 1: Mechanisms by Which Parasites Mediate Competition and Biodiversity

| Mechanism | Functional Description | Impact on Community |

|---|---|---|

| Regulation of Dominant Competitors | Parasites disproportionately impact abundant host species, reducing their competitive superiority and freeing up resources for inferior competitors. | Promotes species coexistence and increases local diversity. |

| Induction of Apparent Competition | Shared parasites create a hidden interaction network; a rise in one host species can increase parasite density, negatively affecting a second host species. | Alters host community composition; can lead to exclusion of susceptible species. |

| Modification of Host Behavior & Traits | Parasites can alter host foraging, habitat selection, or boldness, thereby changing their ecological role and competitive interactions. | Modifies interaction strengths in food webs; can shift competitive hierarchies. |

| Immunomodulation & Cross-Protection | Infection with one parasite can modulate the host immune system, altering susceptibility to secondary infections or other pathologies. | Creates complex disease dynamics; pre-infection with Trichinella spiralis was shown to prevent hepatic fibrosis from Schistosoma mansoni in a murine model [6]. |

The surveillance of parasites in wildlife is crucial for understanding disease ecology. For example, the detection of Pentatrichomonas hominis in Tibetan antelope and the varied genotypes of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in wild rodents across China highlight the role of wildlife as reservoirs and the potential for parasite adaptation and translocation in changing environments [6]. Furthermore, the re-emergence of zoonotic Sarcoptes scabiei from dromedary camels to humans underscores the dynamic nature of parasitic disease boundaries and the necessity for integrated veterinary and human health monitoring [6].

Quantitative Frameworks for Measuring Biodiversity Change

Human pressures—including habitat change, pollution, climate change, and the introduction of invasive species and their parasites—are driving unprecedented biodiversity change. Quantifying these changes requires robust metrics that capture different dimensions of diversity.

Alpha (α) and Beta (β) Diversity

Ecologists measure biodiversity at different scales. α-diversity refers to the diversity within a single community or habitat, while β-diversity quantifies the difference in species composition between communities [11]. Assessing β-diversity is critical for understanding biotic homogenization (decreasing compositional variation among sites) or biotic differentiation (increasing variation) in response to anthropogenic pressures [12].

Qualitative vs. Quantitative β-Diversity Measures

The choice of β-diversity metric can dramatically influence ecological inference, as they reveal different aspects of community change.

Table 2: Comparison of Qualitative and Quantitative Beta-Diversity Measures

| Feature | Qualitative Measures (e.g., unweighted UniFrac) | Quantitative Measures (e.g., weighted UniFrac) |

|---|---|---|

| Data Used | Presence/absence of taxa. | Relative abundance of each taxon. |

| Sensitivity To | Factors that determine which taxa can live in an environment (e.g., temperature, pH, restrictive filters). | Factors that influence the success of taxa (e.g., nutrient availability, transient disturbances). |

| Reveals Patterns of | Founding populations, historical colonization, and environmental filtering. | Blooms of specific taxa and changes in dominant species. |

| Interpretation | High value indicates communities share few taxa. | High value indicates communities differ in the relative abundance of lineages. |

A landmark global meta-analysis of human impacts demonstrated that while human pressures consistently decrease local α-diversity and shift community composition, their effect on β-diversity is scale-dependent. Contrary to long-held expectations, there is no general pattern of biotic homogenization; instead, pressures like resource exploitation and pollution cause biotic differentiation at local scales, while homogenization is more likely at larger scales [12]. This highlights the necessity of multi-scale assessments in biodiversity monitoring.

Experimental Protocols for Key Mechanisms

Elucidating the causal mechanisms structuring communities requires rigorous experimental designs. Below are detailed protocols for investigating two critical areas: parasite-mediated competition and trait-based invasion ecology.

Protocol 1: Assessing Parasite-Mediated Apparent Competition

Objective: To determine if a shared parasite facilitates apparent competition between two sympatric host species. Background: Apparent competition occurs when two host species, which do not directly compete for resources, are linked by a shared pathogen. An increase in the density of one host species can elevate pathogen prevalence, leading to a decline in the second host species. Materials:

- Mesocosms (field enclosures or laboratory microcosms).

- Experimental populations of two host species (e.g., rodent species A and B).

- A defined shared parasite (e.g., a helminth with a direct life cycle).

- Diagnostic tools (e.g., PCR primers, ELISA kits, microscope) for parasite detection and quantification.

- Mark-recapture equipment (traps, tags).

Methodology:

- Pre-treatment Baseline: Establish replicate, isolated populations of each host species at controlled densities. Conduct a pre-treatment census and screen all individuals for the target parasite to ensure a naive starting state.

- Experimental Treatment: Assign mesocosms to one of three treatments:

- Treatment 1 (Control): Single-species populations of A and B.

- Treatment 2 (Single Infection): Single-species populations, but introduce the parasite to Species A populations only.

- Treatment 3 (Apparent Competition): Mixed-species populations of A and B; introduce the parasite to Species A only.

- Monitoring: Conduct weekly censuses to track host population densities, survival, and fecundity. Collect fecal or blood samples regularly to monitor parasite prevalence and load in both host species in all treatments.

- Data Analysis: Compare the population growth rates and fitness measures of Species B across treatments. A significant decline in Species B's fitness in Treatment 3 compared to Treatments 1 and 2 provides evidence for parasite-mediated apparent competition, as the presence of Species A amplifies the parasite's impact on Species B.

Protocol 2: Trait-Based Analysis of Invasion Mechanisms

Objective: To disentangle the roles of environmental filtering, limiting-similarity competition, and hierarchical competition in driving a biological invasion. Background: The success of an invasive species can be attributed to fitting the abiotic environment (filtering), exploiting an empty niche (limiting similarity), or simply being a superior competitor (hierarchical competition). These mechanisms can be distinguished by analyzing the traits of the invader relative to the resident community [9]. Materials:

- Defined study plots (e.g., 4m x 4m quadrats) across invaded and uninvaded areas.

- Pitfall traps, bait stations, or other species-specific collection methods.

- Calibrated instruments for morphological measurement (digital calipers, microscope with camera).

- Equipment for physiological trait measurement (e.g., thermal tolerance chamber).

- High-resolution camera and behavioral tracking software.

Methodology:

- Community Sampling: Quantify the abundance of the invader and all resident species in each plot using standardized methods (e.g., pitfall traps over 48 hours, followed by bait station observations) [9].

- Trait Characterization: Measure a comprehensive suite of traits for the invader and all resident species. Key traits include:

- Morphological: Body size, leg length, mandible length.

- Physiological: Critical thermal maximum (CTmax).

- Dietary: Trophic position via stable isotope analysis.

- Behavioral: Interference ability (e.g., outcomes of aggressive encounters at baits).

- Data Analysis:

- Environmental Filtering: Test if the invader's presence/abundance is correlated with abiotic variables (e.g., ground cover, temperature).

- Limiting Similarity: For each trait, calculate the absolute dissimilarity between the invader and each resident species. Use generalized linear models to test if invasion success is higher when the invader is more dissimilar from the resident community.

- Hierarchical Competition: For each trait, calculate the hierarchical difference (the invader's trait value minus the resident's value). Test if invasion success is higher when the invader's trait values are superior (e.g., larger size, higher CTmax, greater aggression).

Visualization of Conceptual Models and Workflows

Visualizing the complex relationships and experimental workflows is essential for clarity. The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate key concepts and protocols.

Diagram 1: Mechanisms of Community Assembly

This diagram outlines the primary pathways through which environmental and biotic filters shape ecological communities, leading to distinct trait distribution patterns.

Title: Community Assembly Mechanisms

Diagram 2: Parasite-Mediated Apparent Competition Workflow

This chart details the experimental workflow for investigating how a shared parasite can indirectly link the fates of two host species.

Title: Apparent Competition Experimental Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Cutting-edge research in disease ecology and competition relies on a suite of specialized reagents, technologies, and analytical tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Wildlife Disease Ecology

| Category / Item | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Field Sampling & Monitoring | Pitfall traps, bait stations, camera traps, thermologgers, soil corers. | Standardized collection of arthropods, observation of behavior, and recording of microclimatic data. |

| Parasite Detection & Diagnostics | PCR/RT-PCR primers & probes, ELISA kits, monoclonal antibodies, portable DNA sequencers. | Sensitive and specific detection, quantification, and genotyping of parasites in host tissues and environmental samples. |

| Host & Parasite Characterization | Stable isotope analyzers (C, N), thermal tolerance chambers (CTmax), high-resolution microscopes, digital calipers. | Measuring trophic position, physiological limits, and morphological traits for functional diversity studies. |

| Computational & Analytical Tools | R packages (e.g., phyloseq, picante), UniFrac software, GIS software, meta-analysis packages. |

Statistical analysis of community data, phylogenetic diversity calculations, spatial mapping, and large-scale data synthesis. |

| Experimental Manipulation | Mesocosms (field/enclosure), selective whole-genome amplification (SWGA) kits, anti-helminthic drugs (e.g., Albendazole). | Conducting controlled manipulative experiments, enriching pathogen DNA from low-biomass samples, and treating infections to test causality. |

The application of computational tools is vital. For instance, weighted and unweighted UniFrac are used to quantify microbial β-diversity from sequencing data, revealing how factors like temperature (qualitative) or nutrient blooms (quantitative) structure communities [11]. Furthermore, selective whole genome amplification (SWGA) is a crucial method for generating genomic data from pathogens present in low abundance in wildlife host tissues, enabling the study of parasite diversity and evolution [6].

The intricate dance of species coexistence and population regulation is governed by a complex interplay of competitive abilities, environmental filters, and critical biotic mediators, chief among them being parasites. A holistic understanding of biodiversity dynamics is no longer possible without integrating the principles of wildlife disease ecology and the One Health framework. Future research must prioritize several key areas: 1) the fortification of integrated surveillance networks that monitor parasites across human, animal, and environmental interfaces; 2) the application of advanced computational biology and phylogenetic tools to predict the ecological consequences of parasite-mediated interactions; and 3) the explicit incorporation of trait-based hierarchical competition into models of invasion biology and community assembly. By embracing this integrated and mechanistic approach, researchers can better predict biodiversity responses to global change and inform effective conservation and public health strategies.

Avian malaria, caused by parasites of the genera Plasmodium and Haemoproteus, provides a powerful model system for investigating the impacts of climate change on wildlife disease ecology. This review synthesizes evidence from long-term studies demonstrating significant range expansions, increased prevalence, and altered transmission dynamics of avian malaria parasites in response to climatic warming. We present quantitative data from empirical studies, detail methodological frameworks for monitoring and prediction, and discuss the implications for global biodiversity, particularly in previously protected or naive host populations. The findings underscore the critical role of parasites in wildlife disease ecology and the urgent need for multidisciplinary approaches to forecast and mitigate climate-change-driven disease emergence.

Within the broader thesis on the role of parasites in wildlife disease ecology, avian malaria systems exemplify how environmental change can disrupt host-parasite dynamics. The genetic diversity, broad host range, and vector-borne nature of avian malaria parasites make them exceptionally sensitive to climatic variables [13] [14]. Long-term datasets now provide compelling evidence that rising global temperatures are facilitating parasite expansion into new geographic regions and host populations, with potentially devastating consequences for avian health and conservation [15] [16]. This technical guide synthesizes current evidence, experimental methodologies, and theoretical frameworks essential for researchers and drug development professionals working at the intersection of climate change and parasitic disease.

Avian Malaria as a Model System in Disease Ecology

Avian malaria parasites, particularly those of the genus Plasmodium, are structurally and functionally similar to human malaria parasites, offering an invaluable model for studying general principles of parasite ecology and evolution [16]. Key features enhancing their utility include:

- Phylogenetic Position: Genomic analyses confirm that avian Plasmodium species form an outgroup to mammalian-infective lineages, having diverged approximately 10 million years ago, providing an evolutionary baseline for comparative studies [16].

- Broad Host Specificity: Species like Plasmodium relictum can infect birds from over 300 species across 11 orders, enabling studies of cross-species transmission and host switching events in changing environments [13] [14].

- Complex Life Cycle: Avian malaria parasites undergo two obligate exoerythrocytic cycles in the reticuloendothelial system, unlike mammalian parasites that primarily infect hepatocytes, offering insights into diverse host-parasite interactions [16].

- Global Distribution: These parasites are found on all continents except Antarctica, providing replicated systems for studying geographic variation in climate responses [14].

The following table summarizes key parasite species and their characteristics relevant to climate change studies:

Table 1: Key Avian Malaria Parasite Species and Characteristics

| Parasite Species | Primary Host Range | Geographic Distribution | Climate Sensitivity | Conservation Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmodium relictum | Broad (11 bird orders) | Global except Antarctica | High - temperature affects development in vectors | High - responsible for honeycreeper declines in Hawaii |

| Plasmodium gallinaceum | Narrow (primarily galliformes) | Southeast Asia | Moderate - limited by host distribution | Moderate - poultry industry concerns |

| Lineage P43 | Restricted (e.g., black-capped chickadee) | Boreal regions | High - correlated with summer temperatures | Emerging - potential range expansion |

Empirical Evidence for Climate-Driven Range Expansions

Long-Term Temporal Studies in Boreal Regions

A decade-long study (2006-2015) of black-capped chickadees (Poecile atricapillus) in Alaska provides compelling evidence for climate-driven changes in avian malaria epidemiology. Key findings from this research include:

- Prevalence Correlates with Temperature: Analysis of over 2,000 blood samples revealed that interannual variation in Plasmodium prevalence at different sites was positively correlated with summer temperatures at the local scale, though not with statewide temperatures [15].

- Single Lineage Dominance: Sequence analysis of the parasite cytochrome b gene revealed a single Plasmodium lineage (P43), indicating specific climate responses rather than community-level shifts [15].

- Host Condition Effects: Birds with avian keratin disorder (a disease causing accelerated keratin growth in the beak) were 2.6 times more likely to be infected with Plasmodium than unaffected birds, demonstrating how host condition interacts with climate to influence disease outcomes [15].

Latitudinal and Habitat Gradients

Research along latitudinal gradients provides additional evidence for climate limitations on avian malaria distribution:

- Arctic Limitations: Shorebird studies in the High Arctic found an absence of avian malaria infections, while conspecifics in tropical West Africa showed significant infection rates [17].

- Habitat-Mediated Exposure: Shorebirds utilizing freshwater inland habitats showed significantly higher malaria prevalence than those in marine coastal habitats, attributed to differential vector exposure and environmental conditions favorable to parasite development [17].

- Migration Effects: Infections were not detected in birds migrating through temperate Europe despite being present in the same species in tropical Africa, suggesting thermal constraints on parasite development at higher latitudes [17].

The table below quantifies prevalence variations across habitats and host characteristics:

Table 2: Avian Malaria Prevalence Across Habitats and Host Characteristics

| Study System | Habitat Type | Host Species | Prevalence (%) | Key Correlates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alaskan boreal forest | Boreal forest | Black-capped chickadee | Variable by year (0.5-5.2%) | Summer temperatures, host age, avian keratin disorder |

| West African shorebirds | Freshwater inland | Multiple shorebird species | 12.8-24.3% | Habitat type, adult age class |

| West African shorebirds | Marine coastal | Multiple shorebird species | 0-3.1% | Lower vector exposure, salinity effects |

| European temperate | Various | Migratory shorebirds | 0% | Seasonal absence of suitable temperatures |

Methodological Frameworks for Studying Range Expansions

Field Sampling and Molecular Diagnostics

Long-term monitoring of avian malaria requires standardized field and laboratory methodologies:

- Blood Sample Collection: Blood samples (typically 10-50 μL) are collected via venipuncture of the brachial vein, stored in nucleic acid preservation buffer, and kept cool until laboratory analysis [15].

- Molecular Detection: DNA extraction followed by nested PCR amplification of the cytochrome b gene using primers targeting a approximately 480-bp fragment [15]. Protocols should include positive and negative controls to detect contamination.

- Lineage Identification: PCR products are sequenced and compared to databases such as MalAvi to identify known lineages and detect novel variants [14].

- Morphological Confirmation: Microscopic examination of blood smears stained with Giemsa should complement molecular methods to characterize parasite morphology and detect co-infections [13].

Metabolic Theory and Predictive Modeling

The metabolic theory of ecology provides a framework for predicting climate change impacts on parasite distributions:

- Fundamental Thermal Niche: This approach calculates the temperature range between the lowest and highest temperatures in which a specific parasite prospers, based on metabolic constraints [18].

- Parameter Estimation: The model uses knowledge of parasite body size and life cycle to predict how temperature alterations affect mortality, development, reproduction, and infectivity [18].

- Application to Avian Malaria: For Plasmodium species, the model incorporates temperature effects on development in mosquito vectors, which are critical transmission bottlenecks [18].

Diagram 1: Climate Impact on Parasite Range

Genomic Approaches

Comparative genomics of avian malaria parasites reveals features associated with lineage-specific evolution and host adaptation:

- Genome Sequencing: Advanced methods for separating parasite DNA from host DNA include methylated DNA depletion for host background reduction and sequencing from oocysts from dissected mosquito guts [16].

- Genetic Markers: The cytochrome b gene remains the standard for lineage identification, but additional markers such as the nuclear gene MSP1 (merozoite surface protein) reveal geographic genetic variation [14].

- Expanded Gene Families: Genomic analyses identify expansions in invasion-related gene families including the surf multigene family and reticulocyte binding protein homologs, which may facilitate host switching during range expansions [16].

Research Tools and Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Avian Malaria Studies

| Category | Specific Product/Kit | Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | Nucleic acid preservation cards/cards | Field sample stabilization | Maintains DNA integrity without refrigeration |

| DNA Extraction | DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) | High-quality DNA extraction from blood | Effective with nucleated avian erythrocytes |

| Molecular Detection | Avian malaria-specific primers (e.g., HaemNF/R, HaemF/R) | PCR amplification of cytochrome b | Detects both Plasmodium and Haemoproteus infections |

| Sequence Analysis | MalAvi database | Lineage identification | Curated database of avian haemosporidian lineages |

| Microscopy | Giemsa stain | Blood smear examination | Enables morphological identification to species level |

| Vector Studies | Mosquito trapping equipment | Vector collection and identification | Critical for understanding transmission ecology |

Implications for Wildlife Disease Ecology and Conservation

The range expansions of avian malaria parasites under climate change illustrate several fundamental principles in wildlife disease ecology:

- Host-Parasite Coevolution: Climate change disrupts evolved balances between hosts and parasites, potentially leading to novel interactions with severe consequences for naive host populations [19].

- Honeymoon Phases: During range expansion, "honeymoon phases" occur where invasion-front host populations experience a temporary release from parasites, which lag behind due to serial founder events and transmission failure in low-density frontal populations [19].

- Conservation Tragedies: The introduction of Plasmodium relictum to Hawaii, where it caused devastating declines and extinctions in native honeycreepers, exemplifies the potential consequences of parasite range expansions into naive host populations [14].

- Physiological Mismatches: Hosts in newly invaded areas may lack evolved resistance mechanisms, leading to more severe disease outcomes than in regions with long-standing host-parasite associations [19].

Diagram 2: Molecular Workflow for Detection

Future Research Directions

Critical gaps remain in our understanding of climate change impacts on avian malaria parasites, presenting opportunities for future research:

- Translational Framework Implementation: Adoption of a formal translational framework composed of serial phases along a "bidirectional continuum of research" would enhance the application of basic research to conservation solutions [20].

- Integrated Climate-Parasite Models: Development of models that incorporate both metabolic constraints and ecological factors such as host immunity, vector distribution, and land use change [18].

- Genomic Surveillance: Expanded genomic studies to identify genetic markers associated with thermal tolerance and host specificity, enabling better predictions of future range expansions [16].

- Multidisciplinary Approaches: Integration of human psychology and sociology into wildlife disease research to improve intervention strategies and public engagement [20].

Long-term studies of avian malaria provide compelling evidence that climate change is driving significant range expansions and altered transmission dynamics of parasitic diseases. The methodological frameworks, empirical data, and conceptual models presented in this review provide researchers and drug development professionals with the tools necessary to investigate, predict, and mitigate these changes. As climate change accelerates, understanding and addressing parasite range expansions becomes increasingly critical for wildlife conservation, ecosystem management, and broader ecological health. The avian malaria system exemplifies the complex interactions between environmental change, host ecology, and parasite dynamics that will define challenges in wildlife disease ecology for decades to come.

Parasite-mediated competition (PMC) is a pivotal ecological and evolutionary process wherein a parasite indirectly alters competitive interactions between host species. This paradigm provides a crucial framework for understanding population dynamics, species distributions, and conservation outcomes in wildlife disease ecology. Through detailed examination of two canonical host-parasite systems—Anolis lizards infected with Plasmodium and red-gray squirrel competition facilitated by squirrelpox virus—this review synthesizes fundamental principles, experimental methodologies, and quantitative evidence underpinning the PMC paradigm. The analysis reveals that differential parasite virulence, rather than direct competition, often determines species replacement and coexistence, with profound implications for biodiversity conservation, invasive species management, and emerging infectious disease response.

Parasite-mediated competition represents a sophisticated indirect interaction where two species competing for resources are differentially affected by a shared parasite, thereby altering the competitive balance between them [21]. This phenomenon moves beyond traditional concepts of direct interference or exploitation competition by introducing a pathogenic third party that disproportionately impacts one competitor. The theoretical foundation suggests that when species vary in their susceptibility or response to infection, the less susceptible species may gain a competitive advantage, potentially leading to the exclusion of the more susceptible species from shared habitats [21]. Within wildlife disease ecology, PMC has transitioned from a theoretical curiosity to a recognized driver of population dynamics and community structure, particularly in systems experiencing species invasions or environmental change. The investigation of PMC requires integration of field observation, population monitoring, molecular diagnostics, and experimental manipulation to disentangle the complex web of direct and indirect interactions shaping ecological outcomes.

Theoretical Framework and Ecological Context

The PMC paradigm operates within the broader framework of apparent competition, where two species negatively affect each other not through direct resource competition but through shared natural enemies, including predators, parasites, or pathogens [21]. Unlike direct competition, where superior resource acquisition or interference capabilities determine outcomes, PMC hinges on differential pathogenicity and asymmetric virulence between host species.

Theoretical models predict that PMC can drive competitive exclusion under specific conditions: (1) when the parasite exhibits high virulence in one host species but low virulence in another; (2) when the more resistant host species maintains higher parasite prevalence in the environment; and (3) when transmission rates are sufficient to impact population growth rates of the susceptible host [22]. The population dynamics of such systems can be modeled using modified Lotka-Volterra equations that incorporate parasite transmission and host-specific mortality terms, revealing thresholds where parasite effects overwhelm direct competitive interactions.

The ecological context of PMC extends beyond two-host, one-parasite systems to include environmental reservoirs, vector dynamics, and community-level interactions that modify transmission and impact. Habitat fragmentation, climate change, and anthropogenic disturbance can further modulate PMC outcomes by altering host distributions, parasite viability, and transmission opportunities, making this paradigm increasingly relevant to conservation biology and ecosystem management.

Canonical Case Study: Anolis Lizards and Malaria Parasites

The Anolis lizard system on the Caribbean island of St. Maarten provides a foundational example of PMC in natural populations. Two lizard species, Anolis gingivinus and Anolis wattsi, exhibit similar body sizes and ecological requirements, creating strong competitive pressures [23]. Under typical conditions, A. gingivinus represents the superior competitor and occupies the entire island, while A. wattsi remains restricted to central hill regions. The malarial parasite Plasmodium azurophilum infects both red and white blood cells of these lizards but demonstrates striking differential virulence between host species [23].

Empirical Evidence and Distribution Patterns

Research has revealed a precise spatial correlation between parasite distribution and species coexistence. Where P. azurophilum infects A. gingivinus, both lizard species coexist, but where the parasite is absent, only A. gingivinus persists [23]. This distribution pattern occurs over remarkably small spatial scales (hundreds of meters), suggesting localized PMC dynamics. The parasite imposes significant physiological costs on A. gingivinus, including increased immature erythrocytes, decreased hemoglobin, elevated monocytes and neutrophils, and reduced acid phosphatase production in infected white blood cells [24]. This pathology likely reduces the competitive dominance of A. gingivinus, permitting the persistence of A. wattsi in parasite-present areas.

Table 1: Pathological Effects of Plasmodium azurophilum in Anolis gingivinus from St. Maarten

| Physiological Parameter | Effect of Infection | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Erythrocyte maturation | Increase in immature cells | Reduced oxygen transport capacity |

| Hemoglobin concentration | Significant decrease | Impaired aerobic performance |

| Leukocyte profiles | Increased monocytes/neutrophils | Immune activation; energetic costs |

| Acid phosphatase production | Decreased in white cells | Reduced intracellular digestion capacity |

Experimental Approaches and Methodological Framework

Field studies of PMC in Anolis lizards employ integrated approaches combining:

- Population monitoring: Systematic surveys of species distribution and abundance across habitat gradients

- Parasite screening: Blood collection and microscopic examination of stained blood smears for parasite detection

- Physiological assessment: Hematological analysis including cell counts, hemoglobin measurement, and cytochemical staining

- Spatial analysis: Mapping of parasite prevalence and host distribution to identify correlation patterns

The methodological protocol for establishing PMC in this system involves:

- Blood collection: Capture of lizards via noosing or manual techniques followed by blood sampling from the retroorbital sinus or caudal veins

- Parasite detection: Preparation of thin blood smears, methanol fixation, Giemsa staining, and microscopic examination under oil immersion

- Pathology assessment: Differential blood cell counts, hemoglobin quantification, and functional assays of immune cell activity

- Population mapping: Geographic information system (GIS) analysis of species distributions relative to parasite prevalence

Canonical Case Study: Red and Gray Squirrels and Squirrelpox Virus

The competitive displacement of native Eurasian red squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris) by invasive Eastern gray squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis) in the United Kingdom represents a well-documented case of PMC with significant conservation implications [22]. While direct competition for resources occurs, the presence of squirrelpox virus (SQPV) dramatically accelerates population declines of red squirrels. SQPV, which is carried asymptomatically by gray squirrels, causes lethal squirrelpox (SQPx) disease in red squirrels, creating a powerful asymmetric interaction [22].

Quantitative Population Impacts

Long-term monitoring (2002-2012) in Merseyside, England, has provided robust quantitative evidence of SQPV impacts on red squirrel populations. Analysis demonstrates that SQPx incidence has a significant negative effect on red squirrel densities and population growth rates, while gray squirrel density shows little direct impact [22]. The dynamics of red squirrel SQPx cases are determined partly by previous infection in local gray squirrels, identifying gray squirrels as initiators of SQPx outbreaks in red squirrels [22]. Serological evidence suggests only approximately 8% of red squirrels exposed to SQPV survive infection during epidemics, highlighting the extreme virulence of this pathogen in the native species [22].

Table 2: Population-Level Impacts of Squirrelpox Virus on Red Squirrels in Merseyside, UK

| Population Parameter | Impact of SQPx Infection | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Red squirrel density | Significant negative impact | P < 0.05 |

| Population growth rate | Significant negative impact | P < 0.05 |

| Survival rate during epidemics | Approximately 8% survive | Based on retrospective serology |

| Outbreak initiation | Associated with prior gray squirrel infection | Significant correlation |

Monitoring and Diagnostic Methodologies

Research on the squirrel-SQPV system employs comprehensive field and laboratory techniques:

- Line transect surveys: Standardized walking transects (600-1200m) conducted biannually to monitor squirrel abundance and distribution

- Postmortem examination: Systematic necropsy of carcasses discovered by public or wildlife officers

- Virus detection: Histopathological confirmation of SQPV infection in cutaneous and tissue samples

- Serological analysis: Antibody detection to identify previous exposure and survival rates

The experimental protocol for this research includes:

- Population monitoring: Establishment of permanent transects walked consistently by trained volunteers recording species observations and perpendicular distances for density estimation

- Disease surveillance: Collection and pathological examination of deceased squirrels with tissue sampling from major organs and characteristic lesion sites

- Diagnostic confirmation: Gross lesion identification combined with histopathological analysis of tissue changes consistent with poxviral infection

- Data analysis: Integration of population density estimates with temporal and spatial patterns of disease incidence using statistical modeling

Conceptual Model of Parasite-Mediated Competition

The following diagram illustrates the general structure of parasite-mediated competition as observed in both case studies, highlighting the asymmetric relationships between host species and their shared parasite:

Figure 1: General Model of Parasite-Mediated Competition. The non-native host serves as an asymptomatic reservoir for the shared parasite, which causes lethal disease in the native host. Environmental transmission maintains the parasite, while direct competition (dashed line) may co-occur but is often less impactful than the parasitic effect.

Molecular and Analytical Techniques in PMC Research

Advanced molecular techniques have significantly enhanced understanding of PMC dynamics, particularly in characterizing parasite diversity and transmission patterns. Research on lizard malaria parasites exemplifies this approach, combining traditional morphological identification with molecular phylogenetics [25]. Molecular methods enable detection of subclinical infections, discrimination of parasite strains, and reconstruction of transmission networks.

Molecular Characterization Protocols

Methodologies for molecular analysis of blood parasites include:

- DNA extraction: Protocol using Kapa Express DNA extraction kits from ethanol-preserved blood samples

- Nested PCR amplification: Target amplification of cytochrome b gene regions using Plasmodium-specific primers

- Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis: Sequence alignment and tree construction to establish parasite relationships

- Microsatellite analysis: Genotyping using multiple loci to determine multiplicity of infection (MOI) and clone distribution

Studies of Plasmodium mexicanum in lizards demonstrate that parasite clone distribution follows zero-inflated statistical models, suggesting heterogeneous exposure risk and partial immunity in host populations [26]. This sophisticated analysis moves beyond simple prevalence estimates to reveal complex transmission dynamics underlying PMC.

Experimental Workflow for Molecular Studies

The following diagram illustrates the integrated methodological approach for molecular characterization of parasites in PMC research:

Figure 2: Integrated Workflow for Parasite Characterization. Combined morphological and molecular approaches enable comprehensive understanding of parasite diversity, distribution, and dynamics in PMC systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Methods for PMC Investigation

| Tool/Reagent | Application in PMC Research | Specific Examples from Case Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Giemsa stain | Blood smear staining for parasite visualization | Identification of Plasmodium azurophilum in Anolis lizard blood cells [23] |

| Line transect protocols | Population density estimation | Monitoring red and gray squirrel abundance in Sefton Coast, UK [22] |

| Histopathology reagents | Tissue fixation and staining for lesion characterization | Formalin fixation, paraffin embedding, H&E staining for SQPV diagnosis [22] |

| PCR primers for parasite genes | Molecular detection and genotyping | Cytochrome b amplification for Plasmodium species identification [25] |

| Microsatellite markers | Multiplicity of infection (MOI) analysis | Determining clone distribution in Plasmodium mexicanum infections [26] |

| Serological assays | Antibody detection for exposure history | SQPV antibody screening to estimate survival rates in red squirrels [22] |

| GIS technology | Spatial analysis of host and parasite distributions | Mapping correlation between malaria presence and Anolis species coexistence [23] |

Implications for Wildlife Management and Conservation

The PMC paradigm has profound implications for conservation practice, particularly in managing invasive species and protecting threatened populations. The squirrel-SQPV system demonstrates that successful conservation of red squirrels requires integrated disease management alongside habitat protection, including gray squirrel control in critical areas [22]. Theoretical insights from disease ecology highlight the importance of understanding transmission dynamics, reservoir host ecology, and heterogeneity in susceptibility when designing intervention strategies [27].

Wildlife disease management increasingly incorporates ecological theory, with concepts such as density-dependent transmission, reservoir host dynamics, and environmental persistence informing management decisions [27]. However, emerging theoretical concepts including pathogen evolutionary responses to management, biodiversity-disease relationships, and within-host parasite interactions have not yet been fully integrated into conservation practice, representing a critical frontier for applied PMC research.

The One Health framework, which recognizes the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health, provides a comprehensive approach for addressing PMC in anthropogenic landscapes [6]. Parasite research at the human-wildlife-domestic animal interface reveals the complex ecological, socioeconomic, and behavioral factors influencing disease dynamics, emphasizing the need for transdisciplinary solutions to PMC-driven conservation challenges.

Parasite-mediated competition represents a powerful ecological force shaping species distributions, population dynamics, and conservation outcomes across diverse ecosystems. The examination of lizard malaria and squirrel-squirrelpox systems reveals consistent patterns of asymmetric virulence, reservoir host facilitation, and spatial correlation between parasite presence and competitive outcomes. These case studies demonstrate the necessity of integrating disease ecology with community ecology to fully understand species interactions and coexistence mechanisms.

Future research in PMC should prioritize:

- Molecular characterization of parasite diversity and virulence mechanisms across host species

- Experimental manipulations to establish causality in suspected PMC systems

- Long-term monitoring to capture dynamic responses to environmental change

- Integrated modeling incorporating both direct competition and parasite effects

- Management interventions informed by theoretical principles of disease ecology

As anthropogenic changes continue to alter species distributions and contact rates, PMC will likely play an increasingly important role in determining wildlife community composition and ecosystem function. Advancing our understanding of this paradigm remains essential for effective biodiversity conservation, invasive species management, and wildlife health protection in a rapidly changing world.

Advanced Tools for Tracing Transmission: Network Models, Surveillance, and Diagnostics

Social network analysis (SNA) has emerged as a transformative framework for understanding the ecology and transmission of parasites in wildlife systems. This approach moves beyond traditional models that assume homogeneous mixing within host populations, instead explicitly capturing the heterogeneous contact patterns that fundamentally shape disease dynamics [28]. By representing hosts as nodes and their interactions as edges, network models provide a powerful methodology for quantifying transmission pathways, identifying superspreading individuals, and testing targeted control strategies for wildlife parasites [29] [30].

The application of SNA to wildlife parasitology has expanded significantly from its initial focus on epidemic microparasites to encompass a diverse range of endemic parasites with complex life cycles [29]. This technical guide details the conceptual frameworks, methodological approaches, and analytical techniques for applying SNA to study parasite transmission in wildlife populations, with particular emphasis on its integration within broader wildlife disease ecology research.

Theoretical Foundations: Network Theory in Disease Ecology

Basic Network Epidemiology Principles

In epidemiological terms, the transmission rate (β) can be conceptualized as the product of the probability of pathogen transmission given a contact (γ) and the contact rate between individuals (K), expressed as β = γ × K [28]. Social network analysis provides a methodology to quantify the contact matrix (K) that serves as the conduit for transmission pathways. The resulting transmission network is typically a subset of the contact network, as not all contacts lead to successful parasite transmission [28].

Network models are particularly valuable for capturing the heterogeneous contact structures that characterize most wildlife and livestock populations. These heterogeneities arise from social systems, territorial behavior, spatial distribution across landscapes, or management practices in domesticated animals [28]. Unlike conventional compartmental models that assume homogeneous mixing, network approaches naturally incorporate superspreaders—individuals responsible for a disproportionate number of transmission events—and allow for targeted interventions based on network position [28].

Ecological Multiplex Framework for Complex Parasite Life Cycles

Many wildlife parasites, including those of significant conservation and zoonotic concern, have complex life cycles involving multiple transmission routes and host species. The "ecomultiplex" framework addresses this complexity by modeling interdependent transmission pathways as a spatially explicit multiplex network [31]. In this model, different types of ecological interactions (e.g., predator-prey relationships, vector-host contacts, spatial co-occurrence) are represented as distinct layers within a unified network structure [31].

This approach is particularly valuable for parasites like Trypanosoma cruzi, the causative agent of Chagas disease, which can be transmitted through both contaminative routes (via triatomine vectors) and trophic routes (when susceptible predators consume infected vectors or prey) [31]. The ecomultiplex model reveals how the interplay between different interaction layers can lead to phenomena such as parasite amplification, where top predators may unexpectedly facilitate parasite spread through their feeding ecology [31].

Table 1: Key Network Topologies and Their Epidemiological Implications

| Network Topology | Structural Characteristics | Epidemiological Implications | Wildlife Examples |

|---|---|---|---|