Parasite-Mediated Population Regulation in Wildlife: Ecological Mechanisms and Biomedical Implications

This article synthesizes current research on the mechanisms by which parasites regulate wildlife populations, a phenomenon with critical implications for conservation, disease ecology, and biomedical modeling.

Parasite-Mediated Population Regulation in Wildlife: Ecological Mechanisms and Biomedical Implications

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the mechanisms by which parasites regulate wildlife populations, a phenomenon with critical implications for conservation, disease ecology, and biomedical modeling. We explore the foundational ecological principles of density-dependent exposure and susceptibility, detailing how resource availability and host immunity interact to shape infection outcomes. The review examines innovative methodological approaches, including long-term field studies, experimental manipulations, and hierarchical modeling, that disentangle complex host-parasite dynamics. We address key challenges in interpreting parasite-mediated selection and competitive outcomes, while validating findings through cross-system comparisons and meta-analytical evidence. For researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis highlights how insights from wildlife systems can inform preclinical models and therapeutic strategies, emphasizing the importance of ecological context for predicting population outcomes and managing zoonotic disease risks.

Unveiling the Core Ecological Mechanisms of Parasite-Driven Population Control

The regulation of wildlife populations by parasites is a cornerstone of ecological and epidemiological theory. Central to this process is the principle of density-dependent transmission, where the rate of infection increases with host population density. Historically, this has been conceptualized as a single pathway. However, emerging evidence reveals that density dependence operates through two distinct, yet potentially synergistic, mechanisms: density-dependent exposure and density-dependent susceptibility [1]. The former increases contact rates and environmental contamination, while the latter modulates host defense mechanisms via resource-driven trade-offs. This whitepaper synthesizes current research to untangle these dual pathways, providing wildlife researchers and drug development professionals with a mechanistic framework and methodological toolkit for investigating their independent and interactive effects on infection dynamics and population regulation.

Conceptual Framework and Definitions

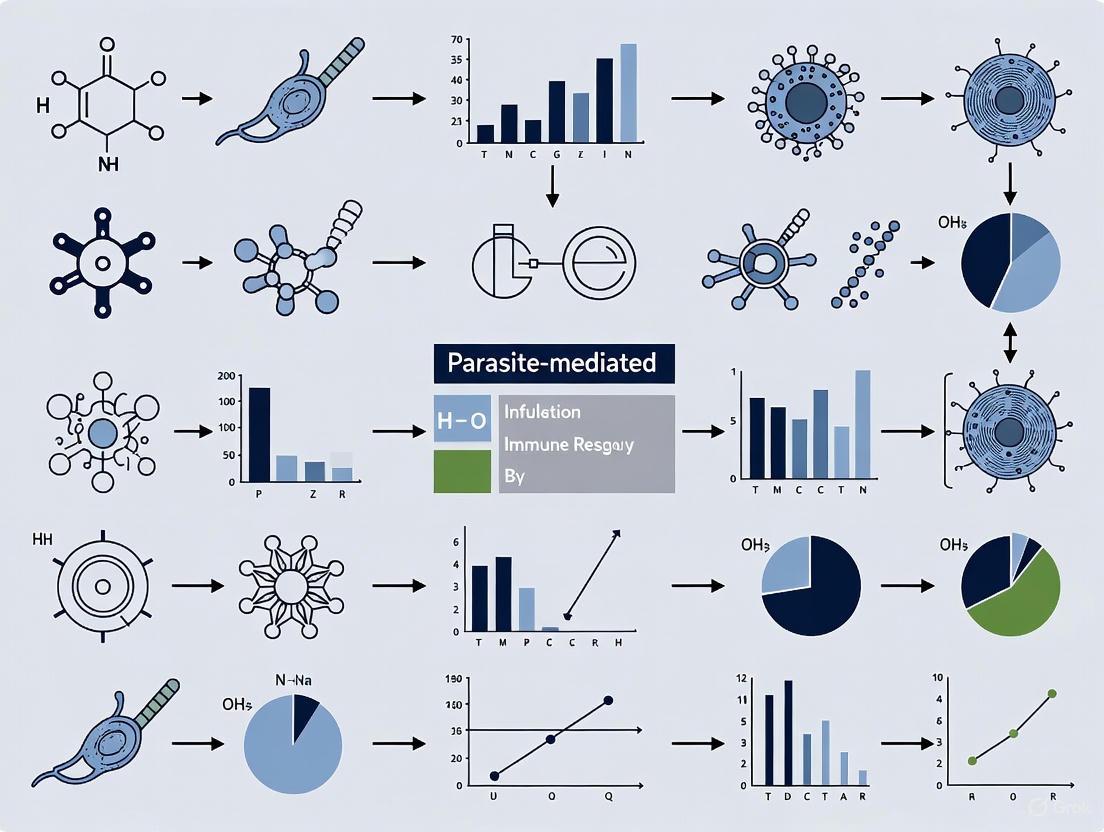

The following diagram illustrates the core conceptual framework of the two density-dependent pathways to infection and their consequences.

Distinguishing the Pathways

Density-Dependent Exposure: This pathway is fundamentally ecological. As host density increases, the rate of contact between infected and susceptible individuals rises, and the environment becomes more heavily contaminated with infective parasite stages [2]. This leads to a greater force of infection, independent of the host's physiological state.

Density-Dependent Susceptibility: This pathway is fundamentally physiological. High population density intensifies competition for limited resources like food. To cope, hosts may sacrifice costly immune function, leading to a higher per-capita susceptibility upon exposure [2] [1]. A related concept is Density-Dependent Prophylaxis (DDP), where individuals pre-emptively invest more in immunity at high densities as an adaptive response to the elevated risk of disease exposure [1].

Key Empirical Evidence from Wildlife Systems

Robust evidence for the dual pathways comes from long-term studies of wildlife populations, which allow researchers to measure density, resource availability, immune markers, and parasite burdens simultaneously.

The Red Deer (Cervus elaphus) Helminth System

A long-term study of wild red deer on the Isle of Rum provides a definitive example of both pathways operating in tandem. Researchers combined decades of individual-based life-history data with spatial mapping and parasite counts to dissect the mechanisms [2].

- Experimental & Observational Approach: Detailed demographic and health monitoring of a known population, coupled with spatial analysis to account for heterogeneous distribution. Immunity was assessed via antibody levels, and resource availability was estimated using the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) as a proxy for forage quality [2].

- Key Findings:

- Exposure Pathway: A direct, positive correlation was found between local deer density and burdens of strongyle and tissue nematodes, indicating accumulation of infective stages in the environment [2].

- Susceptibility Pathway: Density was negatively correlated with resource availability (NDVI). Furthermore, resource availability was positively correlated with immune function, which was in turn negatively correlated with parasite burdens. This demonstrated an independent resource-based pathway reducing host immunity and increasing susceptibility [2].

The quantitative findings from this seminal study are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Quantitative Relationships in the Red Deer-Helminth System [2]

| Variable | Relationship with Density | Relationship with Resource Availability (NDVI) | Relationship with Immunity | Relationship with Parasite Burden |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Host Density | --- | Negative | Indirectly Negative (via resources) | Positive |

| Resource Availability | Negative | --- | Positive | Negative (independent of density) |

| Immunity | Indirectly Negative | Positive | --- | Negative |

| Parasite Burden | Positive | Negative | Negative | --- |

The Multimammate Mouse (Mastomys natalensis) and Morogoro Virus System

Research on African multimammate mice and Morogoro virus (MORV) highlights how host behavior interacts with these pathways, adding a layer of complexity.

- Experimental Approach: A replicated semi-natural experiment was used to monitor populations over a density gradient. Viral infection status was determined by antibody (MORVab) detection, and host personality was assayed by measuring exploration behavior in a standardized test [3].

- Key Findings:

- Exposure Pathway: A strong positive correlation was found between host density and the prevalence of MORV antibodies, confirming density-dependent transmission for this directly transmitted virus [3].

- Behavioral Modulation: Contrary to expectations, less explorative individuals were more likely to be seropositive. However, exploration score was itself positively correlated with density, suggesting an indirect, and counterintuitive, effect of density on infection risk via behavior [3].

The Theoretical Backbone: Population Dynamics and DDP

The population-level consequences of these processes are explored through mathematical models, which have yielded critical insights, particularly regarding Density-Dependent Prophylaxis (DDP).

Modeling Density-Dependent Prophylaxis

A foundational theoretical study developed a host-pathogen model to explore how DDP influences population stability [1]. The model treated the transmission rate as a function of host density, reflecting the increased immune investment at higher densities.

- Critical Finding: The Role of Time Delay: The model identified the time delay between the change in population density and the phenotypic change in resistance as the critical factor determining population dynamics [1].

- Short/No Delay: DDP has a destabilizing effect, promoting population cycles.

- Long Delay: DDP has a stabilizing effect, damping population fluctuations.

- Interpretation: This highlights a crucial trade-off. While DDP is adaptive for the individual, its population-level impact depends on the speed of the physiological response, which varies across systems.

The workflow for building and applying such theoretical models to understand host-parasite interactions is complex, as shown in the following diagram.

Implications for Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Intervention

Understanding these ecological mechanisms is not merely an academic exercise; it directly informs the discovery and development of antiparasitic drugs.

- Challenges in Antiparasitic Drug Development: The pipeline for new antiparasitic drugs faces high attrition rates. A major challenge is the meaningful translation of drug efficacy from preclinical models (e.g., mice infected with rodent-specific parasites like P. berghei) to human applications (e.g., P. falciparum malaria) [4].

- The Host-Parasite System as a Variable: Mechanistic modeling shows that host-parasite interactions, including resource availability and parasite maturation rates, significantly drive dynamics in preclinical systems. Ignoring these density-dependent host factors can lead to misinterpretation of a drug's pharmacodynamic properties [4].

- Two Strategic Approaches to Drug Discovery:

- Whole-Organism Screening: The source of all current market-approved antiparasitic drugs. This involves screening compound libraries against the entire parasite in vitro (e.g., Plasmodium blood stages) or in vivo, then identifying the target later [5].

- Target-Based Drug Design: A post-genomic strategy that starts with identifying essential parasite proteins (e.g., calcium-dependent protein kinases in apicomplexans) via genomic mining, followed by rational drug design [5]. While intellectually appealing, this approach has yet to yield a market-ready antiprotozoal drug, highlighting the complexity of parasite biology within a host [5].

Table 2: Key Reagents and Methodologies for Investigating Density-Dependent Infection

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Relevant Example |

|---|---|---|

| Long-Term Individual Monitoring Data | Provides high-resolution data on host life history, density, and health status. | Red deer study: individual-based records over decades [2]. |

| Spatial GIS Mapping | Quantifies local host density and environmental heterogeneity. | Mapping deer territory use to calculate local density [2]. |

| Remote Sensing (e.g., NDVI) | Proxies for host resource availability in landscapes. | Using satellite-derived NDVI to assess forage quality for deer [2]. |

| Immunological Assays (e.g., ELISA) | Quantifies host immune investment (antibody levels, cytokine profiles). | Measuring antibody levels as a marker of immune competence in red deer [2]. |

| Behavioral Assays | Characterizes consistent animal personalities (e.g., exploration) that may affect infection risk. | Open-field tests to score exploration in multimammate mice [3]. |

| Semi-Natural Enclosure Experiments | Allows controlled manipulation of density while preserving natural behaviors. | Replicated enclosures for multimammate mice with varying densities [3]. |

| Mechanistic Mathematical Models | Integrates data to test hypotheses and predict population dynamics under different scenarios. | Host-pathogen ODE models exploring DDP stability [1] [4]. |

The distinction between density-dependent exposure and susceptibility is fundamental to a mechanistic understanding of parasite-mediated population regulation. Evidence from wild systems like red deer and multimammate mice confirms that both pathways operate simultaneously, yet independently, driven by ecological contact and physiological trade-offs, respectively. The integration of long-term field studies, controlled experiments, and mechanistic modeling is essential to untangle their effects. For professionals in drug discovery, acknowledging these complex host-parasite-environment interactions is critical for improving the translation of preclinical findings and developing effective therapeutic interventions that are robust in the face of real-world ecological dynamics.

Resource availability serves as a fundamental moderator of individual physiology, species interactions, and population dynamics in wildlife systems. This relationship is particularly critical in the context of host-parasite interactions, where energy allocation trade-offs directly influence immune competence, pathogen persistence, and ultimately population outcomes. Within parasite-mediated population regulation, the balance between host nutritional status, immune investment, and pathogen virulence determines whether parasites act as regulating forces or destabilizing threats to wildlife populations.

Mounting evidence suggests that parasites can significantly influence host population density and persistence [6]. The interplay between resource availability and parasite effects creates a complex feedback loop: host internal resource abundance depends partially on the external environment, while within-host dynamics influence among-host disease transmission and population trajectories [7]. Understanding these resource-mediated pathways is therefore essential for predicting population responses to environmental change and implementing effective conservation strategies.

Theoretical Framework: Resource Allocation Models

The interaction between host immune systems and pathogens is often characterized as a predator-prey relationship, but this oversimplification ignores their shared dependence on host resources for reproduction and function [7]. Consumer-resource theory provides a more nuanced framework for understanding how energetic constraints modify host-parasite interactions across different ecological scenarios.

Energy Allocation Topologies

Four primary models describe the resource-based interactions between host energy reserves (E), immune function (I), and pathogens (N), each with distinct predictions for how pathogen load responds to increasing resource supply [7]:

Table 1: Theoretical Models of Immune-Pathogen Resource Competition

| Model Type | Resource Pathway | Predicted Pathogen Response to Increased Resources |

|---|---|---|

| Independent Resources | Separate energy bins for immune system (EI) and pathogens (EN) | Pathogen load increases |

| Pathogen Priority | Pathogens access reserves directly; immune system uses allocated bin | Pathogen load increases |

| Immune Priority | Immune system accesses reserves directly; pathogens use allocated bin | Pathogen load decreases |

| Energy Antagonism | Both immune system and pathogens compete for same resource pool | Pathogen load peaks at intermediate resources |

The energy antagonism model is particularly insightful as it demonstrates non-monotonic responses, where pathogen load peaks at intermediate resource levels because low resources constrain pathogen replication while high resources enable effective immune function [7]. This explains why empirical studies document all three patterns (increase, decrease, and peak) across different host-parasite systems.

Life History Trade-Offs

Host life history strategy significantly moderates how resource availability translates to population outcomes. Meta-analysis of parasite effects on wild vertebrate hosts reveals that host lifespan correlates strongly with parasite virulence, with long-lived species experiencing more pronounced population-level effects from parasitic infections [8]. This likely reflects differential energy allocation strategies, where long-lived hosts prioritize survival over reproduction and thus invest more heavily in immune defense when resources permit.

The cost of immune defense manifests not only in energy expenditure but also in oxidative stress. Immune activation can generate reactive oxygen species during oxidative burst, creating a potential trade-off between immune function and antioxidant defenses [9]. This resource allocation network creates a complex decision matrix for hosts facing multiple challenges in resource-limited environments.

Empirical Evidence: From Immunological to Population Outcomes

Resource Modulation of Immune Function

Evidence from wild populations demonstrates that immune investment is highly sensitive to resource availability. Research on Antarctic fur seals reveals that pup immune responses are more responsive than adults to variation in food availability, with immune investment associated with different oxidative status markers in pups versus mothers [9]. This suggests that early life stages show greater sensitivity to extrinsic effectors like resource limitation, making them particularly vulnerable to parasite-mediated population regulation.

The same study documented significant ontogenetic changes in immune profiles, with bacterial killing capacity, hemagglutination, hemolysis, IgG, and oxidative damage markers increasing significantly in pups from birth to molt, while lysozyme and neopterin concentrations decreased [9]. This dynamic immune development makes juvenile survival particularly dependent on adequate resource acquisition.

Table 2: Immune and Oxidative Status Markers in Ecological Immunology

| Marker Category | Specific Marker | Immune Function | Resource Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constitutive Innate | Bacterial Killing Assay (BKA) | Overall constitutive innate function | Low energetic & pathological costs |

| Hemagglutination | Natural antibody function | Low energetic & pathological costs | |

| Lysozyme | Lysis of gram-positive bacteria | Low energetic & pathological costs | |

| Induced Innate | Haptoglobin | Antibacterial, immunomodulatory | High energetic & pathological costs |

| Innate & Adaptive | Neopterin | Pro-inflammatory responses | High energetic & pathological costs |

| Adaptive | Immunoglobulin G (IgG) | Immunological memory, pathogen neutralization | High energetic, low pathological costs |

| Cellular | White Blood Cell counts | Various phagocytic and adaptive functions | Variable costs by cell type |

| Oxidative Status | dROM, OXY, GPx, SOD | Oxidative damage, antioxidant capacity | Linked to immune activation costs |

Parasite-Mediated Competition in Wildlife Systems

The moose (Alces alces) and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) system in northern New York provides compelling evidence for parasite-mediated competition driven by resource-mediated effects. Research demonstrates that moose occupancy is limited by parasite-mediated competition via shared parasites (meningeal worm Parelaphostrongylus tenuis and giant liver fluke Fascioloides magna), with no evidence of population-level effects from direct competitive interactions [10].

This system exemplifies asymmetric parasite-mediated competition, where white-tailed deer as definitive hosts suffer minimal morbidity from meningeal worm infection, while moose as abnormal hosts experience severe neurological disease and death [10]. The persistence of this asymmetric interaction depends critically on environmental factors affecting host distribution and resource availability, particularly recent declines in winter severity and snowfall that have increased spatiotemporal overlap between these cervid species [10].

Methodological Approaches

Experimental Designs for Resource-Immune-Pathogen Interactions

Longitudinal Field Studies

The Antarctic fur seal study employed a fully crossed, repeated measures design sampling 100 pups and their mothers from colonies of contrasting density during seasons of contrasting food availability [9]. Blood collection for 13 immune and oxidative status markers at two key life-history stages (after birth and at approximately 60 days during molting) enabled assessment of how intrinsic and extrinsic factors influence immune trade-offs.

Key methodological considerations:

- Timing: Measurements must align with biologically relevant life-history stages

- Covariates: Collection of biometric, endocrine (cortisol), and environmental data

- Repeatability: Assessment of individual consistency over time requires repeated measures

- Scale: Simultaneous measurement of multiple immune effectors to capture system complexity

Hierarchical Occupancy Modeling

The moose-deer parasite study leveraged detection/non-detection data and parasite loads from fecal samples within a hierarchical abundance-mediated interaction model [10]. This approach accounts for imperfect detection in wildlife surveys while testing hypotheses regarding direct versus indirect species interactions.

Implementation protocol:

- Multi-species sampling across heterogeneous landscape

- Parasite load quantification from fecal samples

- Incorporation of detection probabilities into interaction models

- Joint modeling of observation and state processes

- Comparison of models with and without competitive interactions

The Researcher's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methods for Ecological Immunology

| Reagent/Method | Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Killing Assay (BKA) | Quantifies plasma ability to kill bacteria (e.g., S. aureus, E. coli) | Measures constitutive innate function; low cost |

| Hemagglutination-Hemolysis Assay | Measures natural antibody and complement titers | Low technical requirement; indicates humoral immunity |

| Enzyme Immunoassays | Quantifies specific proteins (haptoglobin, neopterin, IgG) | Requires species-specific antibodies; high cost |

| White Blood Cell Counts | Differential counts of immune cell populations | Requires blood smears and staining expertise |

| Oxidative Status Panels | Measures antioxidant capacity (OXY) and damage (dROM) | Multiple assays needed for complete picture |

| Hormone Assays | Quantifies cortisol, other stress hormones | Radioimmunoassay or ELISA; requires validation |

| Genetic Sequencing | Identifies immunogenetic adaptations | Requires specialized facilities and bioinformatics |

Conservation Implications and Management Applications

Understanding resource moderation of immune function and parasite impacts is critical for effective wildlife conservation. Treatment success for wildlife diseases depends critically on host immune responses, which are themselves resource-dependent [11]. For example, modeling of white-nose syndrome in bats demonstrates that treatment can accelerate extirpation if hosts are defended by responsive immunity, whereas treatment can help populations undergoing evolutionary rescue regain viability faster [11].

The growing recognition of parasites as conservation targets in their own right further complicates management decisions [12] [13]. Parasites represent a substantial proportion of Earth's biodiversity and play important ecological roles, yet they remain underrepresented in conservation planning [13]. Resource-mediated approaches suggest that effective parasite conservation requires maintaining access to suitable hosts and the ecological conditions that permit successful transmission, rather than focusing solely on species-centered approaches [12].

Climate change and habitat alteration are rapidly transforming resource availability for wildlife populations, making understanding of these pathways increasingly urgent. Urban environments, for instance, create novel selective pressures on animal immunity, with evidence for pathogen-driven immunostimulation in urban-dwelling animals [14]. The polygenic nature of immune adaptations to urban life suggests that resource constraints may shape host-parasite coevolution in human-altered landscapes.

Resource availability serves as a critical moderator linking individual immune function to population-level outcomes in wildlife systems. The integration of theoretical models, empirical evidence, and methodological advances provides a robust framework for predicting how environmental change will alter host-parasite dynamics through resource pathways. Future research should prioritize interdisciplinary approaches that connect molecular mechanisms to ecological consequences, particularly in the context of rapid global change. Conservation success will depend on acknowledging these complex resource-mediated interactions when managing both hosts and parasites in increasingly human-dominated landscapes.

Parasite-mediated competition represents a critical indirect interaction that structures ecological communities by altering competitive outcomes between species through shared parasites. This review synthesizes current empirical evidence, demonstrating that parasite-mediated competition frequently supersedes direct competition in regulating host populations and distributions. Focusing on cervid communities and other wildlife systems, we analyze the mechanisms whereby differential parasite virulence shapes species coexistence, with profound implications for population regulation, conservation planning, and ecosystem management. Our analysis integrates quantitative meta-analytical findings with recent case studies to provide a technical framework for investigating parasite-driven ecological dynamics.

Parasite-mediated competition occurs when competing species share parasites, and these parasites differentially affect the competitors' fitness, thereby altering the competitive balance between them [10]. This interaction represents a powerful yet underappreciated ecological mechanism that can structure communities and regulate populations without direct interference between species. Two primary theoretical frameworks explain how parasites influence competitive outcomes: (1) apparent competition, where a shared parasite generates asymmetric negative effects on host species without direct competition between them, potentially destabilizing coexistence; and (2) parasite-mediated competition, where parasites modulate existing competitive interactions between species that directly compete for resources [10]. Understanding these pathways is essential for predicting population dynamics and designing effective conservation strategies, particularly in systems where parasites may be driving enigmatic population declines or range contractions.

Theoretical Framework and Population Regulation

The theoretical foundation for parasite-mediated competition stems from ecological models demonstrating that shared natural enemies can profoundly influence species coexistence. The "prudent parasite" model suggests that parasites evolve toward a balance between short-term and long-term transmission needs, potentially conferring a range of effects on infected hosts [15]. In contrast, the "mutual aggression" model posits that parasites evolve toward maximal virulence, making them a primary regulatory force [15]. The population-level consequences of these evolutionary trajectories are determined by key host life-history traits, particularly average host lifespan, which correlates significantly with observed parasite virulence [15]. Meta-analytical syntheses indicate that shorter-lived hosts experience higher parasite virulence due to fewer opportunities for parasite dispersal to new hosts, creating selective pressure for more aggressive transmission strategies [15].

Quantitative Evidence: Meta-Analytical Synthesis

A comprehensive meta-analysis of 38 experimental datasets on non-domesticated, free-ranging wild vertebrate hosts revealed a strong negative effect of parasites at the population level (Hedges' g = 0.49) [15]. The analysis demonstrated significant parasite effects on key demographic parameters, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Population-level effects of parasites across vertebrate hosts

| Response Variable | Effect Size (Hedges' g) | Statistical Significance | Number of Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clutch Size | -0.38 | p < 0.05 | 12 |

| Hatching Success | -0.45 | p < 0.05 | 9 |

| Young Produced | -0.52 | p < 0.01 | 14 |

| Survival Rate | -0.61 | p < 0.01 | 18 |

| Breeding Success | -0.19 | Not Significant | 11 |

Meta-regression analyses identified host life history traits that explain variation in parasite virulence across systems. Host lifespan emerged as the single most important predictor, with shorter-lived species experiencing disproportionately greater virulence [15]. Additional factors influencing virulence included nesting ecology (cavity-nesting species experienced increased parasite density and virulence) and sociality (colonial species showed heightened parasite transmission and effects) [15]. These findings provide a quantitative basis for predicting parasite impacts across host species with different life history strategies.

Case Study: Cervid Communities and Shared Parasites

The Moose-White-Tailed Deer System

A recent investigation of moose (Alces alces) and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) interactions provides compelling empirical evidence for parasite-mediated competition [10] [16]. This system involves two shared parasites with differential virulence:

- Meningeal worm (Parelaphostrongylus tenuis): White-tailed deer serve as the definitive host with minimal morbidity, while moose experience severe neurological disease and frequent mortality from infection [10].

- Giant liver fluke (Fascioloides magna): Deer maintain normal parasite life cycles, while moose suffer extensive organ damage and death from heavy infestations due to incomplete parasite development [10].

Researchers leveraged a natural experiment across a 4050 km² study area in northern New York, where moose and deer co-occur across gradients of parasite intensity [10]. Using a hierarchical abundance-mediated interaction model with two years of detection/non-detection data and parasite loads from fecal samples, the study tested competing hypotheses regarding moose population limitation.

Experimental Protocol and Methodological Framework

The experimental approach provided a rigorous template for investigating parasite-mediated competition:

Field Sampling: Researchers collected detection/non-detection data for both cervid species across multiple sites, simultaneously obtaining fecal samples for parasite load quantification [10].

Parasite Quantification: Fecal samples were analyzed to determine intensity of meningeal worm and giant liver fluke infection using standardized parasitological techniques [10].

Hierarchical Modeling: The team implemented an abundance-mediated interaction framework that accounted for imperfect detection in wildlife surveys while testing direct versus indirect interaction pathways [10].

Hypothesis Testing: The model specifically evaluated whether moose occupancy was better explained by (i) direct competitive effects of deer abundance, (ii) indirect effects via parasite abundance, or (iii) habitat factors alone [10].

This methodological approach overcame limitations of previous correlative studies by simultaneously quantifying interaction strengths while accounting for observational uncertainties in wildlife surveys.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Essential research materials for field studies of parasite-mediated competition

| Research Tool | Application | Technical Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Fecal Collection Kits | Parasite egg identification and quantification | Standardized containers with preservative for field collection |

| Hierarchical Abundance-Mediated Interaction Models | Statistical analysis of species interactions | Bayesian framework incorporating imperfect detection |

| GPS Telemetry Equipment | Animal movement and space use data | High-frequency location data to quantify overlap |

| Molecular Diagnostics | Parasite species identification and load quantification | PCR-based assays for specific parasite detection |

| Remote Camera Traps | Detection/non-detection data collection | Motion-activated cameras with timestamp functionality |

Contrasting Case Study: Flying Squirrel System

Not all investigations of putative parasite-mediated competition yield positive results. Research on northern (Glaucomys sabrinus) and southern flying squirrels (G. volans) examined the intestinal nematode Strongyloides robustus as a potential mediator of competition [17]. Contrary to the cervid system, this study found:

- Wide Host Range: S. robustus was detected in four squirrel species (flying squirrels, grey squirrels, and red squirrels), not just the putative competitors [17].

- Asymmetric Effects: Infection negatively affected body condition in northern flying squirrels and red squirrels, but not southern flying squirrels or grey squirrels [17].

- Limited Competitive Exclusion: Despite weak asymmetric effects, no evidence indicated that parasite-mediated competition could lead to competitive exclusion from woodlots [17].

This contrasting case highlights the importance of empirical verification and demonstrates that shared parasites do not invariably drive competitive outcomes.

Conceptual Framework and Visual Synthesis

The mechanistic pathway of parasite-mediated competition can be visualized through the following conceptual model:

Parasite-Mediated Competition in Cervids

This conceptual model illustrates how white-tailed deer as definitive hosts maintain parasite populations that spill over to moose, which suffer disproportionate fitness consequences. Environmental factors facilitate transmission, while direct competition appears negligible in regulating moose distribution.

Implications for Wildlife Conservation and Management

The evidence for parasite-mediated competition necessitates paradigm shifts in conservation planning:

Integrated Host-Parasite Management: Conservation strategies should consider endangered hosts and their parasites together as threatened ecological communities rather than automatically excluding parasites from protection considerations [12].

Ecosystem-Centered Approaches: Effective parasite conservation requires maintaining access to suitable hosts and ecological conditions that permit successful transmission, favoring ecosystem-centered over species-centered conservation [12].

Predictive Framework: Host life history traits, particularly lifespan, provide predictive power for anticipating parasite virulence and incorporating these interactions into population viability analyses [15].

Climate Change Interactions: Changing climatic conditions may alter host distributions and overlap, potentially exacerbating parasite-mediated competition in previously unaffected regions [10].

Parasite-mediated competition represents a potent ecological force that can structure wildlife communities and regulate populations through indirect pathways. The cervid case study demonstrates how shared parasites with differential virulence can limit dominant competitors without direct interference, while the flying squirrel system cautions against assuming universal applicability of this mechanism. Future research should prioritize experimental manipulations of parasite loads in long-lived hosts, where current evidence remains limited despite predicted heightened effects. Integrating parasite-mediated interactions into conservation planning and population models will enhance our ability to manage wildlife communities in an era of rapid environmental change.

Within the broader context of parasite-mediated population regulation in wildlife, the evolutionary interplay between hosts and parasites is a fundamental driver of population dynamics and genetic diversity. Host-parasite coevolution represents a reciprocal process of adaptation and counter-adaptation, where parasites evolve increased infectivity and hosts respond with enhanced resistance mechanisms [18]. This coevolutionary arms race has profound implications for wildlife management, conservation biology, and understanding emerging infectious diseases. Theoretical models have played a crucial role in shaping our understanding of these dynamics, demonstrating how parasitism can promote genetic variation through mechanisms such as negative frequency-dependent selection and trade-offs between resistance and other fitness-related traits [18] [19]. This technical guide synthesizes current understanding of how disruptive selection and local adaptation operate within host-parasite systems, with particular emphasis on their role in population regulation in wildlife species.

Theoretical Foundations of Host-Parasite Coevolution

The coevolutionary dynamics between hosts and parasites form a feedback loop that can maintain genetic diversity through various mechanisms. Understanding these theoretical foundations is essential for interpreting empirical patterns in natural systems.

Models of Coevolutionary Dynamics

Mathematical modeling has been crucial for developing our understanding of host-parasite coevolution, resulting in a rich body of theoretical literature spanning the last 70 years [18]. Early population genetic models considered coevolution at one or two loci and demonstrated the potential for negative frequency-dependent selection to cause cyclical allele frequency dynamics in both hosts and parasites [18]. These cyclical dynamics were later formalized in the Red Queen Hypothesis, which posits that species must continually evolve to maintain their fitness relative to coevolving species [18].

Different modeling approaches yield varying predictions about coevolutionary outcomes. Theoretical models vary widely in their assumptions, approaches, and aims, with two features having particularly significant qualitative impact: population dynamics and the genetic basis of infection [18]. The inclusion of population dynamics typically dampens or reduces the likelihood of fluctuating selection dynamics and increases the incidence of polymorphism, while highly specific infection genetics often lead to rapid fluctuating selection [18].

Table 1: Key Modeling Approaches in Host-Parasite Coevolution

| Model Feature | Approach Variations | Impact on Dynamics |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Structure | Haploid vs. Diploid | Diploidy reduces incidence of cycling and makes local adaptation more likely [18] |

| Infection Genetics | Gene-for-gene vs. Matching alleles | Specific genetics produce rapid fluctuating selection; variation in specificity leads to stable polymorphism [18] |

| Population Dynamics | Included vs. Excluded | Increases likelihood of stable polymorphism and dampens oscillations [18] |

| Time Representation | Discrete vs. Continuous | Continuous time may generate damped cycles where discrete time generates stable cycles [18] |

| Spatial Structure | Well-mixed vs. Spatial | Leads to greater host resistance and lower parasite infectivity; increases fluctuating selection [18] |

From Theory to Empirical Patterns

Theoretical predictions have shaped our investigation of natural systems, particularly regarding how genetic diversity is maintained. While theory readily predicts that parasites can promote host diversity through mechanisms such as disruptive selection, empirical evidence for parasite-mediated increases in host diversity remains surprisingly scant [20]. This mismatch between models and data has driven the development of more sophisticated approaches to detect selection in natural populations.

Theoretical models suggest that with particular trade-offs, parasitism could drive disruptive selection, favoring hosts that are either resistant but have reduced fecundity, or susceptible and highly fecund (where the fitness benefits of increased reproduction outweigh the fitness costs of infection) [20]. This contrasts with the more commonly observed pattern of directional selection for resistant host genotypes, which typically leads to reduced genetic diversity within populations [20].

Disruptive Selection in Natural Host-Parasite Systems

Empirical Evidence from Daphnia-Yeast Systems

A compelling example of parasite-mediated disruptive selection comes from a natural population of the freshwater crustacean Daphnia dentifera during an epidemic of the yeast parasite Metschnikowia bicuspidata [20]. This system provides rare empirical support for parasite-driven increases in host genetic diversity and demonstrates how rapidly this evolution can occur.

During the epidemic, researchers observed that the mean susceptibility of clones collected before and after the epidemic did not differ significantly (pre-epidemic mean susceptibility = 0.28, post-epidemic = 0.24; F₁,₅₃ = 0.50, p = 0.48) [20]. However, the variance in susceptibility increased more than threefold (from 0.008 to 0.03; randomization test p = 0.004) [20]. This pattern of unchanged mean but increased variance is a hallmark signature of disruptive selection.

Table 2: Quantitative Changes in Daphnia dentifera Population During Yeast Epidemic

| Parameter | Pre-Epidemic | Post-Epidemic | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Susceptibility | 0.28 | 0.24 | F₁,₅₃ = 0.50, p = 0.48 |

| Variance in Susceptibility | 0.008 | 0.03 | Randomization test p = 0.004 |

| Clonal Variance (Vc) | Low | High | Increased dramatically |

| Broad-sense Heritability (H²) | Low | High | Increased dramatically |

| Distribution of Susceptibility | Unimodal | Bimodal | Maximum likelihood model selection [20] |

The application of a novel maximum likelihood method developed specifically for detecting selection in natural populations confirmed disruptive selection during the epidemic [20]. The best-fitting model indicated that the distribution of susceptibilities shifted from unimodal prior to the epidemic to bimodal afterward [20]. Interestingly, this same bimodal distribution was retained after a generation of sexual reproduction, suggesting potential assortative mating or other mechanisms maintaining the diversity [20].

Underlying Mechanisms and Trade-offs

In the Daphnia-Metschnikowia system, the most likely explanation for the observed disruptive selection is a trade-off between susceptibility and fecundity, mediated through their joint relationships with body size [20]. There is a positive correlation between body size and fecundity in Daphnia, and simultaneously a positive relationship between body size and susceptibility to Metschnikowia [20]. This creates a scenario where larger-bodied clones are more fecund but more susceptible, while smaller-bodied clones are less fecund but more resistant.

This evolutionary outcome reflects the competing needs of reproduction versus immunity that hosts face when allocating limited resources [19]. Both theoretical and empirical studies suggest that reproduction and immunity represent two competing needs in the host's overall resource allocation strategy [19]. The costs of immunity can be separated into two distinct classes: the standing defense cost of maintaining an immune system, and the acute cost of up-regulating the immune system once an individual is infected [19].

Diagram 1: Mechanism of parasite-mediated disruptive selection. Environmental pressures interact with genetic variation in host body size, creating trait correlations that drive disruptive selection during parasite epidemics.

Local Adaptation in Metapopulations

Theoretical Framework for Local Adaptation

Local adaptation in host-parasite systems occurs when parasites become better at infecting local hosts than allopatric hosts, or when hosts become better at resisting local parasites than allopatric parasites. The geographic mosaic theory of coevolution posits that spatial variation in selection pressures creates a patchwork of coevolutionary hot spots and cold spots across landscapes [18].

Theoretical models indicate that spatial structure generally leads to greater host resistance and lower parasite infectivity, while also making fluctuating selection more likely [18]. Environmental heterogeneity promotes generalism in both hosts and parasites and often increases polymorphism [18]. In metapopulation models, the dominant evolutionary stable strategy (ESS) sometimes differs from the population-level ESS and depends on the ratio of local extinction rate to host colonization rate [19].

Population and Metapopulation Dynamics

At the population level, the evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS) represents a balanced investment between reproduction and immunity that maintains parasites, even though the host has the capacity to eliminate them [19]. This balanced strategy emerges from the trade-off where resources allocated to immunity cannot be allocated to reproduction, and vice versa.

In a metapopulation context, the optimal allocation strategy shifts based on migration and extinction dynamics. Hosts exhibiting the population-level ESS can often invade other host populations through parasite-mediated competition, effectively using parasites as biological weapons [19]. This phenomenon may help explain why parasites are as common as they are and provides a modeling framework for investigating parasite-mediated ecological invasions [19].

Table 3: Comparison of Evolutionary Stable Strategies (ESS) in Different Population Structures

| Aspect | Single Population ESS | Metapopulation ESS |

|---|---|---|

| Investment Strategy | Balanced between reproduction and immunity | Varies with extinction/colonization ratio |

| Parasite Persistence | Maintained despite host capacity for elimination | May be eliminated in some demes |

| Competitive Ability | Can be invaded by other strategies | Depends on migration rates |

| Genetic Diversity | Maintains polymorphisms | Varies across spatial scales |

| Response to Change | Slower evolutionary response | Faster response due to spatial dynamics |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Detecting Disruptive Selection in Natural Populations

The study of disruptive selection in host-parasite systems requires specific methodological approaches that can detect changes in trait distributions and distinguish disruptive selection from other forms of selection.

Protocol 1: Longitudinal Sampling of Host Populations During Parasite Epidemics

- Pre-epidemic sampling: Collect host individuals from the population before the parasite epidemic begins. For clonal organisms like Daphnia, establish multiple clonal lines in the laboratory [20].

- Infection assays: Conduct standardized infection assays by exposing host clones to parasites under controlled conditions. Record susceptibility as the proportion of individuals that become infected [20].

- Epidemic monitoring: Monitor the natural population throughout the epidemic, tracking infection prevalence and population density [20].

- Post-epidemic sampling: Collect host individuals after the epidemic declines and establish clonal lines as in step 1 [20].

- Statistical analysis: Compare mean susceptibility, variance in susceptibility, and the distribution of susceptibilities between pre- and post-epidemic clones using both traditional methods and maximum likelihood approaches [20].

Protocol 2: Maximum Likelihood Method for Detecting Selection

- Model development: Create a set of candidate models representing different selection scenarios (directional, stabilizing, disruptive) [20].

- Parameter estimation: Use maximum likelihood estimation to fit each model to the observed distribution of susceptibilities [20].

- Model selection: Compare models using information-theoretic approaches (e.g., Akaike Information Criterion) to identify the best-supported model [20].

- Goodness-of-fit testing: Validate the selected model using appropriate goodness-of-fit tests [20].

Quantifying Local Adaptation

Protocol 3: Reciprocal Transplant Experiments for Local Adaptation

- Sample collection: Collect hosts and parasites from multiple geographic locations representing different potential evolutionary scenarios [18].

- Cross-infection experiments: In controlled laboratory conditions, conduct all possible combinations of infections between host and parasite populations [18].

- Fitness measurements: For hosts, measure resistance (probability of infection) and other fitness components (fecundity, survival). For parasites, measure infectivity and transmission potential [18].

- Statistical analysis: Analyze using ANOVA frameworks with host population, parasite population, and their interaction as factors. Local adaptation is indicated by significant host-by-parasite population interactions [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for Studying Host-Parasite Evolution

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Clonal Lines | Maintain genetic identity for repeated experiments; quantify genetic variance | Establishing pre- and post-epidemic clones in Daphnia studies [20] |

| Standardized Infection Assays | Quantify susceptibility under controlled conditions | Measuring infection rates in different host genotypes [20] |

| Environmental Mesocosms | Semi-natural experimental systems bridging lab and field | Studying population dynamics under controlled environmental conditions [6] |

| Molecular Markers | Genotype identification; population genetic analyses | Tracking clone frequencies in natural populations [20] |

| Maximum Likelihood Models | Detect and differentiate forms of selection from trait distributions | Identifying disruptive selection from bimodality in susceptibility [20] |

| Trade-off Assay Systems | Quantify relationships between resistance and other fitness components | Measuring correlations between body size, fecundity, and susceptibility [20] |

Environmental Modulation of Selection Dynamics

Environmental change can significantly alter host-parasite evolutionary trajectories and their resulting impacts on population regulation. Both rapid and gradual environmental changes modify host immune responses, parasite virulence, and the specificity of interactions [21]. Two major environmental stressors—temperature change and nutrient input—have demonstrated effects on host-parasite evolutionary dynamics.

There is evidence for both disruptive and accelerating effects of environmental pressures on speciation that appear to be context-dependent [21]. A prerequisite for parasite-driven host speciation is that parasites significantly alter the host's Darwinian fitness, which can rapidly lead to divergent selection and genetic adaptation [21]. However, these evolutionary changes are likely preceded by more short-term plastic and transgenerational effects that may provide alternative pathways to speciation [21].

Environmental change acts at multiple levels: directly on individual physiology, on host-parasite interaction outcomes, and on the ecological context in which these interactions occur [21]. Understanding these multi-level effects is crucial for predicting how wildlife populations will respond to ongoing global environmental change.

Diagram 2: Environmental modulation of host-parasite coevolution. Environmental drivers affect host and parasite biology, which in turn alter selection pressures and evolutionary trajectories through both immediate and long-term responses.

Implications for Wildlife Population Regulation

The evolutionary dynamics of disruptive selection and local adaptation have direct consequences for parasite-mediated population regulation in wildlife systems. Parasites can influence host population density and persistence, with specific characteristics determining the strength of these effects [6].

Mathematical models predict different population dynamics for hosts infected with microparasites that reduce host fecundity versus those that reduce host survival [6]. Host density decreases monotonically with the negative effect that a parasite has on host fecundity, while mean host population density first decreases and then increases as parasite-induced host mortality rises [6]. This occurs because parasites that kill their hosts very rapidly are less likely to be transmitted and therefore remain at low prevalence [6].

Empirical studies with Daphnia parasites confirm that parasite species with strong effects on host fecundity are powerful agents for host population regulation [6]. The fewer offspring an infected host produced, the lower the density of its population, with this effect being relatively stronger for vertically transmitted parasite strains than for horizontally transmitted parasites [6].

From a conservation perspective, understanding these evolutionary dynamics is crucial for predicting population responses to environmental change, managing wildlife diseases, and preserving genetic diversity in threatened populations. The evidence that parasitism can increase genetic variance within host populations, and that this increase can occur rapidly, highlights the importance of incorporating evolutionary principles into wildlife management strategies [20].

While the role of parasites in regulating host populations is a cornerstone of disease ecology, their broader influence on ecosystem structure and function extends far beyond simple population decline. This whitepaper synthesizes current research to elucidate the multifaceted ecosystem roles of parasites, framing these interactions within the context of parasite-mediated population regulation in wildlife. We detail the mechanisms through which parasites influence trophic interactions, competitive hierarchies, and biodiversity patterns. Supported by quantitative data and explicit experimental protocols, this guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with a mechanistic understanding of how parasites act as keystone species in ecological communities, with implications for conservation biology and ecosystem management.

Parasitism represents one of the most widespread life-history strategies in nature, arguably more common than traditional predation as a consumer lifestyle [22]. Despite their historical omission from many ecological models, advances in disease ecology have revealed that parasites are not only ecologically important but can sometimes exert influences that equal or surpass those of free-living species in shaping community structure [22]. The traditional focus on parasite-induced population decline has overshadowed the complex ecosystem functions that parasites mediate, including their roles in trophic interactions, energy flow, and maintenance of biodiversity.

This technical guide reframes parasites as integral components of ecosystems, emphasizing their functions beyond population regulation. Within the broader thesis of parasite-mediated population regulation, we explore how the effects of parasites on individual hosts and host populations scale up to influence community structure and ecosystem processes. By integrating empirical evidence, quantitative data, and experimental methodologies, we provide a comprehensive resource for researchers investigating the ecological consequences of parasitism.

Parasite Influences on Community Structure: Mechanisms and Evidence

Modulating Competitive Interactions and Biodiversity

Parasites can profoundly alter competitive outcomes between host species, a phenomenon termed parasite-mediated competition. This process can either reduce or enhance biodiversity depending on which host species are most affected and whether the parasites disproportionately impact competitively dominant or inferior species [22].

Mechanisms and Empirical Evidence:

- Facilitating Species Coexistence: On the Caribbean island of St. Maarten, the competitively dominant lizard Anolis gingivinus outcompetes Anolis wattsi across most of the island. However, the two species coexist in the interior where the malarial parasite Plasmodium azurophilum heavily infects A. gingivinus. The parasite reduces the competitive ability of the dominant species, thereby creating a refuge for the inferior competitor and maintaining higher local biodiversity [22].

- Driving Competitive Exclusion: Conversely, the introduction of a parapoxvirus facilitated the displacement of native red squirrels by invasive grey squirrels in Britain. The virus infected both species, but native red squirrels experienced high susceptibility and mortality, while invasive grey squirrels suffered only minor effects. In this case, a parasite reduced biodiversity by accelerating the exclusion of a native species [22].

- Genetic Dilution Effects: Recent research demonstrates that these effects extend to parasite genetic diversity. A study of gastrointestinal strongylid nematodes (Oesophagostomum aculeatum) in a Bornean primate community found that higher primate host diversity reduced strongylid genetic richness (Amplicon Sequence Variant richness) during the wet season—a phenomenon termed a "genetic dilution effect" [23]. This suggests that biodiversity conservation can directly suppress the expansion of parasite genetic diversity, with potential implications for disease emergence risks.

Table 1: Documented Cases of Parasite-Mediated Competition and Biodiversity Outcomes

| Host System | Parasite | Effect on Competition | Impact on Biodiversity | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caribbean Lizards | Plasmodium azurophilum | Reduced dominance of A. gingivinus | Increased (Coexistence promoted) | [22] |

| Red vs. Grey Squirrels | Parapoxvirus | Enhanced advantage of invasive grey squirrels | Decreased (Native species declined) | [22] |

| Bornean Primates | Oesophagostomum aculeatum | Primate diversity diluted parasite genetic richness | Potential reduction in disease risk | [23] |

| Daphnia Species | Caullerya mesnili | Reversed competitive hierarchy | Altered community composition | [6] |

Integrating Parasites into Trophic Networks and Energy Flow

Parasites are integral components of food webs, functioning as both predators and prey, and facilitating significant energy flows within ecosystems.

Roles in Trophic Interactions:

- Parasites as Prey: Parasites can represent a substantial food resource for predators. On islands in the Gulf of California, predators such as lizards, scorpions, and spiders are one to two orders of magnitude more abundant on islands with sea bird colonies because they feed extensively on bird ectoparasites [22]. Similarly, cleaner wrasses and shrimp consume ectoparasites removed from host fish, constituting a direct energy transfer from parasites to higher trophic levels.

- Trophic Transmission and Host Manipulation: Many parasites with complex life cycles manipulate host behavior or morphology to facilitate transmission to subsequent hosts. The trematode Euhaplorchis californiensis infects estuarine killifish, causing erratic swimming behavior that increases predation by bird definitive hosts by up to 30-fold [22]. Another trematode, Ribeiroia ondatrae, causes severe limb deformities in amphibians, impairing escape responses and increasing susceptibility to predation [22].

- Contribution to Ecosystem Energetics: The biomass and productivity of parasites can rival that of top predators in some systems. In estuarine ecosystems, the yearly productivity of trematode parasites was found to be higher than the biomass of birds [22]. In Minnesota grasslands, the biomass of plant fungal pathogens was comparable to that of herbivores, and these pathogens exerted stronger top-down control on grass biomass than herbivory [22]. These findings challenge the traditional assumption that parasites contribute negligibly to ecosystem energy flow.

Table 2: Quantitative Evidence of Parasite Contributions to Ecosystem Energetics

| Ecosystem | Parasite Group | Metric | Comparison | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estuarine System | Trematodes | Yearly Productivity | Higher than bird biomass | [22] |

| Minnesota Grasslands | Fungal Pathogens | Biomass & Control | Comparable to herbivores; stronger control of plant biomass | [22] |

| Salt Marsh Food Web | Various Parasites | Link Involvement | Involved in 78% of all trophic links | [22] |

Keystone Effects and Ecosystem Engineering

When parasites infect dominant or keystone host species, their effects can cascade through the entire ecosystem, radically altering habitat structure and function.

Case Study: Diadema Urchins in the Caribbean The sea urchin Diadema antillarum functioned as a key grazer on Caribbean coral reefs. A massive die-off of these urchins, linked to a microbial pathogen, removed this critical ecological function. The result was a dramatic phase shift from coral- to algae-dominated reefs, as algal cover increased from 1% to 95% within two years in affected areas [22]. This single parasite-mediated event fundamentally re-engineered the ecosystem. The subsequent, albeit slow, recovery of Diadema populations in some areas has initiated a shift back toward coral dominance, highlighting the profound keystone role that parasites can play by modulating the abundance of a key host species [22].

Quantitative Frameworks and Experimental Approaches

Investigating Biodiversity-Disease Relationships

A central question in disease ecology is how host biodiversity influences disease risk, encapsulated in the dilution effect hypothesis, which posits that greater biodiversity can reduce disease transmission.

Key Meta-Analysis Findings: An analysis of 205 biodiversity-disease relationships revealed critical patterns [24]:

- Nonlinearity: Biodiversity-disease relationships are most commonly nonlinear (61% of studies), not linear.

- Scale Dependence: Biodiversity generally inhibits disease (dilution effect) at local scales, but this effect weakens or reverses as spatial scale increases.

- Context Dependence: The shape of the relationship (e.g., left- or right-skewed hump) determines whether amplification or dilution effects predominate across observed diversity gradients.

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying Biodiversity-Disease Relationships

- Objective: To test the effect of host diversity on parasite transmission and infection prevalence in a controlled setting.

- Model System: Daphnia-parasite systems are ideal for such experiments due to their tractability [6].

- Methodology:

- Establishment of Microcosms: Create replicated aquatic microcosms with varying levels of host species richness (e.g., 1, 2, 4, or 6 species of Daphnia), while controlling for total host density.

- Parasite Introduction: Introduce a known quantity of a specific parasite (e.g., the bacterium Pasteuria ramosa or the fungus Metschnikowia bicuspidata) to each microcosm.

- Monitoring: Track host population densities and parasite prevalence over time through regular sampling.

- Endpoint Measurements: Quantify parasite infection intensity in individual hosts via microscopy or molecular methods and record host population extinction events.

- Key Metrics: Final host density, parasite prevalence and intensity, time to host population extinction.

- Expected Outcomes: As demonstrated by Ebert et al. (2000), parasites with strong effects on host fecundity are powerful regulators of host population density and increase extinction risk. The relationship between host diversity and parasite success is expected to be nonlinear and context-dependent [6] [24].

A Constraint-Based Approach to Parasite Aggregation

The axiom that macroparasites exhibit aggregated distributions (many hosts have few parasites, few hosts have many) is a cornerstone of disease ecology. A constraint-based approach provides a robust null model for understanding these patterns.

Theoretical Framework: Traditional approaches try to infer mechanism from the degree of aggregation. The constraint-based approach, in contrast, posits that the total number of parasites (P) and hosts (H) in a sample imposes fundamental constraints on the possible shapes of the host-parasite distribution [25]. The most likely distribution can be predicted using these constraints alone, without specifying biological mechanisms.

Experimental Protocol: Sampling for Constraint-Based Analysis

- Objective: To collect field data on host-parasite distributions for testing against constraint-based null models.

- System: Amphibian-trematode systems are well-suited, as used in a study analyzing 842 host-parasite distributions [25].

- Field Sampling:

- Systematic Sampling: Collect a representative sample of hosts from a defined population (e.g., via standardized visual encounter surveys for amphibians).

- Parasite Quantification: Necropsy hosts and count all macroparasites of the target species (e.g., trematodes in the digestive tract). Molecular identification can be used for cryptic species.

- Data Recording: Record the total number of hosts (H) and the total number of parasites (P) found in the entire sample, along with the distribution of parasites per host.

- Data Analysis:

- Compare the observed variance-to-mean ratio (a measure of aggregation) of parasites per host to the distribution predicted by the constraint-based null model.

- If the observed distribution matches the null model, the aggregation pattern contains no additional information about mechanism beyond P and H.

- Significant deviation from the null model suggests the action of specific biological processes (e.g., host heterogeneity, parasite-induced mortality) that further constrain the distribution [25].

Long-Term Monitoring of Climate-Parasite Interactions

Climate change is altering host-parasite dynamics, and long-term studies are critical for documenting and understanding these changes.

Experimental Protocol: Long-Term Avian Malaria Surveillance

- Objective: To assess the impact of climate warming on the prevalence and transmission of vector-borne parasites in a wild bird population.

- System: A 26-year study of malaria parasites (Haemoproteus, Plasmodium, Leucocytozoon) in blue tits (Cyanistes caeruleus) in southern Sweden serves as a model [26].

- Methodology:

- Host Sampling: Annually, during the breeding season (April-July), capture birds from a monitored population (e.g., using nest boxes). Collect blood samples via venipuncture.

- Molecular Screening: Extract DNA from blood samples and use nested PCR protocols targeting the cytochrome b gene to detect and identify haemosporidian parasite lineages.

- Climate Data: Obtain daily temperature and precipitation data from nearby meteorological stations for the study period.

- Climate Window Analysis: Use statistical models (e.g., sliding window analysis) to identify specific time windows (e.g., May 9th-June 24th) when temperature is most strongly correlated with parasite transmission to juvenile birds [26].

- Key Metrics: Annual parasite prevalence for each genus, infection intensity, and correlation coefficients between climate variables and prevalence.

- Findings: Such a study revealed that all three malaria parasite genera increased significantly in prevalence over 26 years, with the most common parasite, Haemoproteus majoris, increasing from 47% to 92%. This increase was directly correlated with warmer temperatures during the host nestling period [26].

Conceptual Synthesis and Visualization

The ecosystem roles of parasites and the methodologies used to study them can be synthesized into a conceptual workflow that connects mechanisms, investigation approaches, and ecological outcomes. The following diagram illustrates this integrative framework and the relationships between its components.

Diagram 1: An integrative framework illustrating the key parasite-mediated mechanisms, the research approaches used to investigate them, and the resulting ecological outcomes. The blue arrows indicate the primary flow from mechanism to investigation to outcome, while the dashed red arrows represent feedback loops through which ecological outcomes can subsequently influence the initial mechanisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The study of parasites in ecosystem contexts requires a multidisciplinary toolkit, ranging from field biology equipment to advanced molecular genetics technologies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Ecological Parasitology

| Tool Category | Specific Item/Technique | Primary Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Field Sampling & Ecology | Standardized transects/boat surveys | Quantify host density and distribution | Primate and bird population surveys [23] [26] |

| Nest boxes/banding equipment | Monitor marked individuals over time | Long-term avian studies (e.g., blue tits) [26] | |

| Microcosm/Mesocosm setups | Controlled experimentation | Testing biodiversity-disease relationships in Daphnia [6] | |

| Molecular Genetics | High-Throughput Sequencing (HTS) | Characterize parasite communities/genetic diversity | Identifying Strongylid ASVs in primates [23] |

| ITS2 rDNA / cytochrome b PCR | Parasite detection and lineage identification | Screening avian blood for malaria parasites [26] [23] | |

| Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) | High-resolution metric of parasite genetic diversity | Measuring "genetic dilution effect" [23] | |

| Data Analysis & Modeling | Multivariate Regression Trees (MRT) | Identify key determinants of parasite abundance | Analyzing multi-scale coral reef fish parasite data [27] |

| Constraint-Based Null Models | Provide robust null for parasite aggregation | Testing if aggregation conveys mechanistic info [25] | |

| Climate Window Analysis | Identify temporal correlation between climate and disease | Linking temperature to malaria transmission peaks [26] |

The evidence is clear that parasites are not merely passengers in ecosystems but are active drivers of community structure and function. Their roles in mediating competition, influencing trophic dynamics, and acting as keystone species demonstrate that their ecological impact extends far beyond the population-level declines that are often the focus of wildlife disease studies. Understanding these broader roles is not only critical for developing a complete picture of ecosystem functioning but also for predicting the consequences of biodiversity loss and climate change. The frameworks and methodologies detailed in this guide provide a pathway for researchers to further elucidate the complex and integral ecosystem roles of parasites.

Advanced Approaches for Quantifying Parasite Impacts in Wild Systems

Longitudinal field studies provide unparalleled insights into the complex interplay of ecological and evolutionary forces that shape wildlife populations. This review synthesizes findings from three cornerstone systems—red deer (Cervus elaphus), Soay sheep (Ovis aries), and the water flea (Daphnia magna)—to elucidate the mechanisms of parasite-mediated population regulation. By integrating decades of individual-based data with advanced modeling approaches, these studies demonstrate how parasites act as powerful selective agents through direct mortality, effects on reproductive success, and interactions with host density, genetic diversity, and climate. The evidence underscores the necessity of long-term, individual-based datasets for unraveling the feedback loops between host demography, parasite pressure, and environmental change, offering critical frameworks for conservation, management, and understanding disease dynamics.

Parasites are increasingly recognized as drivers of population regulation in wildlife species, exerting profound influences on host survival, reproduction, and long-term evolutionary trajectories [8]. The principle of parasite-mediated population regulation posits that infectious agents can modulate host population growth through density-dependent and frequency-dependent processes, often interacting with environmental factors and host genetics. Longitudinal studies—tracking known individuals over substantial portions of their lifespans—provide the essential temporal depth and resolution needed to disentangle these complex relationships. Research on wild populations of red deer, Soay sheep, and Daphnia has been instrumental in moving beyond correlation to demonstrate causal pathways through which parasites influence host population dynamics.

These model systems highlight three critical dimensions of host-parasite interactions: (1) the role of host genetic diversity in determining susceptibility and the resulting inbreeding depression via parasitism [28], (2) the demographic and environmental context that modulates the strength of parasite effects [29] [30], and (3) the energetic and life-history trade-offs hosts make in response to parasitic infection [31]. The integration of individual-level infection data with long-term life-history and pedigree information has revealed that parasites can impose significant fitness costs, reducing host survival [32], fecundity [33], and competitive ability [10], with consequences that scale to the population level.

Core Study Systems and Key Quantitative Findings

Red Deer (Cervus elaphus)

The long-term study of red deer on the Isle of Rum, Scotland, has provided groundbreaking insights into the evolutionary ecology of a large mammal population, particularly regarding parasite-mediated selection.

Table 1: Key Findings from the Red Deer Study System

| Aspect | Key Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Inbreeding Depression | Genomic inbreeding reduces juvenile survival, partly mediated by higher strongyle nematode burdens [28]. | Reveals a pathway for parasites to purge genetic load. |

| Parasite Community | Population monitored for three common helminths: strongyle nematodes, liver fluke (Fasciola hepatica), and tissue worms (Elaphostrongylus cervi) [28]. | Different parasites exert distinct selective pressures. |

| Fitness Costs | Inbreeding reduced overwinter survival in adult females, independent of effects on parasitism [28]. | Demonstrates multiple pathways of inbreeding depression. |

Soay Sheep (Ovis aries)

The Soay sheep of St. Kilda, Scotland, represent a classic example of a fluctuating population regulated by the synergistic effects of density dependence, climate, and parasites.

Table 2: Key Findings from the Soay Sheep Study System

| Aspect | Key Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Population Dynamics | The population experiences dramatic "boom-bust" cycles, shrinking by up to 70% in some years [30]. | Illustrates strong density-dependent regulation. |

| Parasite Role in Mortality | Sheep with high parasite loads (esp. strongyle nematodes) are more likely to die during harsh winters [32]. | Parasitism interacts with climate to cause mortality. |

| Density Dependence | Local host density has distinct, parasite-specific effects on infection intensity, with positive relationships for some GI nematodes [34]. | Shows that parasite transmission is spatially explicit. |

| Genetic Effects | Individuals with higher genomic homozygosity have higher parasite loads and lower winter survival [32]. | Confirms parasite-mediated inbreeding depression. |

Water Flea (Daphnia magna)

Daphnia serves as a model organism in aquatic ecology, with experimental studies allowing for precise manipulation of environmental variables to test their interactive effects with parasites.

Table 3: Key Findings from the Daphnia magna Study System

| Aspect | Key Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Allocation | An allometric growth model showed unpredictable temperatures reduce energy allocated to reproduction, similar to constant high temperatures [31]. | Climate variability imposes energetic costs. |

| Multi-generational Stress | Long-term exposure to pharmaceuticals like ibuprofen altered reproduction and habitat selection behavior [33]. | Highlights transgenerational effects of pollutants. |

| Experimental Utility | Short lifespan and clonal reproduction enable high-replication studies of host-parasite coevolution [35]. | Ideal for controlled experiments on evolutionary dynamics. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Longitudinal Field Monitoring (Red Deer and Soay Sheep)

The power of long-term vertebrate studies stems from rigorous, standardized protocols for data collection.

- Individual Marking and Life-History Monitoring: In both the Rum red deer and St. Kilda Soay sheep populations, a high proportion of individuals are uniquely marked and followed throughout their lives. For deer, approximately 90% of calves are caught soon after birth, weighed, permanently marked, and sampled for genetic analysis [28]. Soay sheep are similarly marked, with over 95% of individuals in the core study area tagged [34].

- Parasitological Sampling: Fecal samples are collected non-invasively from known individuals. For red deer, observers note defecating deer from a distance and collect samples, which are refrigerated at 4°C and processed within three weeks for parasitological examination [28]. For Soay sheep, fecal samples are often collected during annual captures in August. The standard method for quantifying gastrointestinal parasite burden is the modified McMaster technique, which provides fecal egg counts (FEC) for nematodes or fecal oocyst counts (FOC) for protozoans [34]. These counts serve as a validated proxy for actual parasite burden within the host.

- Spatial and Demographic Data: Regular population censuses are conducted (e.g., 30 per year in the Soay sheep study) where observers record individual identity, location, and group membership [34]. This allows for the calculation of local density metrics and the integration of spatial ecology.

Controlled Laboratory Experiments (Daphnia magna)

Daphnia protocols allow for the isolation of specific stressors under replicable conditions.

- Culturing and Exposure: Test organisms are typically clones, ensuring genetic uniformity. As described in one study, individuals are placed in individual glass containers and exposed to specific experimental conditions (e.g., temperature regimes, pharmaceutical concentrations) for their entire lives [31] [33]. The culture medium is changed regularly, and individuals are fed a fixed, above ad libitum concentration of algae to control for food availability.

- Life-History Trait Measurement: Key response variables include:

- Body Size: Measured microscopically or via image analysis software like ImageJ from the tip of the head to the base of the tail spine [31].

- Reproduction: The number of neonates produced in each brood is recorded, along with the timing of reproductive events [31] [33].