Parasite Biodiversity Loss: Conservation Challenges and Biomedical Implications in the Era of Coextinction

This article synthesizes current research on parasite biodiversity and its conservation, addressing a critical knowledge gap for researchers and drug development professionals.

Parasite Biodiversity Loss: Conservation Challenges and Biomedical Implications in the Era of Coextinction

Abstract

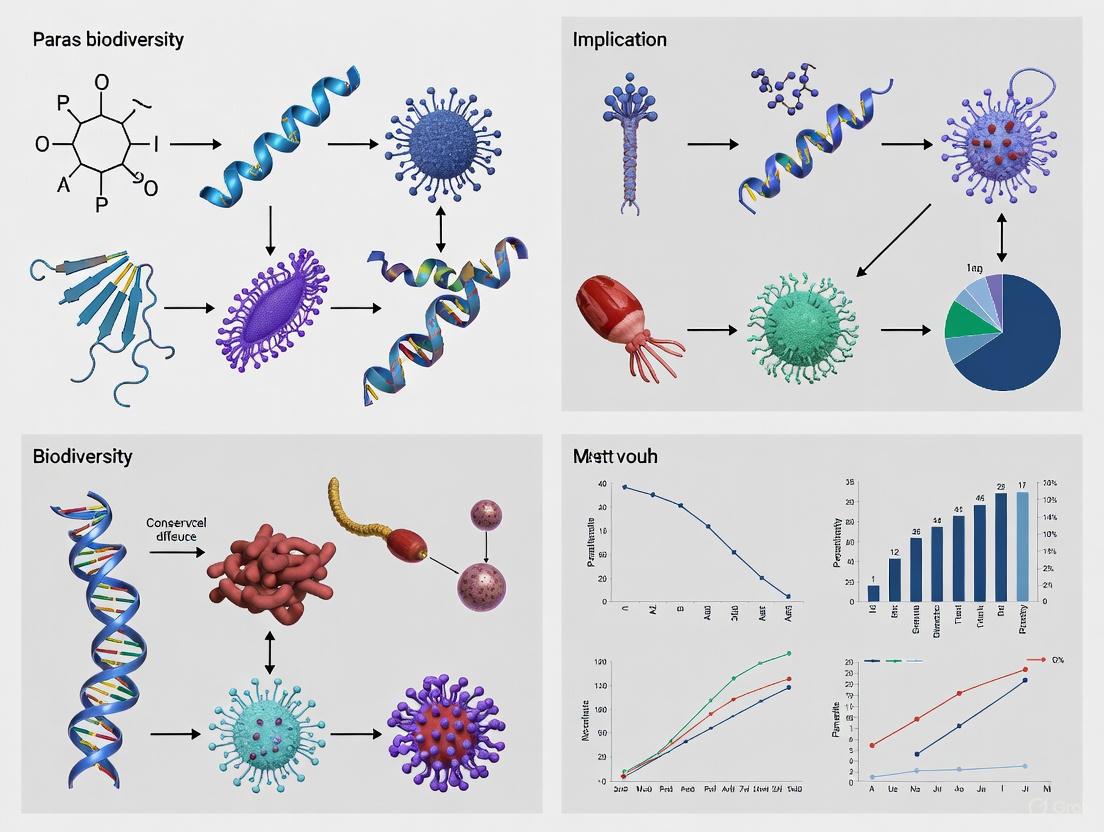

This article synthesizes current research on parasite biodiversity and its conservation, addressing a critical knowledge gap for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational concept of parasite coextinction, exemplified by recent findings that over 80% of parasite taxa have been lost in endangered host populations. The content examines methodological advances in documenting parasite loss through ancient DNA analysis and computational bioprospecting. It further investigates the paradoxical role of biodiversity in buffering disease and troubleshoots the challenges of integrating parasites into conservation frameworks. Finally, it validates the untapped value of parasitic organisms as a source for novel therapeutic agents, linking conservation imperatives directly to future drug discovery pipelines for neglected tropical diseases.

The Unseen Extinction: Documenting the Scale and Drivers of Parasite Biodiversity Loss

Coextinction represents a critical, yet often overlooked, frontier in the global biodiversity crisis. It is defined as the phenomenon where the loss of one species leads to the secondary extinction of another species that depends on it [1] [2]. For parasites, which constitute a substantial proportion of the planet's biological diversity, this process poses an existential threat. Parasitism is the most common consumer strategy on Earth, and the dependency of parasites on their hosts creates a fundamental vulnerability when host populations decline [3]. The conservation of parasites has historically been neglected in favor of more charismatic fauna, yet a growing body of evidence demonstrates that parasites are ecologically significant and highly susceptible to coextinction events [3] [4]. This technical guide examines the mechanisms and implications of parasite coextinction, framing the issue within the broader context of parasite biodiversity and conservation science.

The Coextinction Mechanism and Parasite Vulnerability

The coextinction process operates through direct and indirect pathways that link parasite survival to host availability. The fundamental mechanism can be visualized as a dependency network where host extinction triggers a cascade of secondary losses.

The vulnerability of parasites to coextinction is primarily governed by two key factors: the rate of host extinctions and the degree of host specificity exhibited by the parasite species [1]. Host specificity refers to the range of host species a parasite can successfully exploit, with specialists (those dependent on a single host species) being at greatest risk. Evidence from eriophyoid mites demonstrates this extreme specialization, where approximately 80% of known species depend on a single host plant species, 95% on a single plant genus, and 99% on a single plant family [1]. This dependency creates a direct pathway to coextinction when host plants disappear.

Parasites face the additional threat of falling below their transmission threshold host population size, which can occur well before host extinction becomes irreversible [3]. This transmission threshold represents the minimum host population density required for parasites to maintain viable populations, making parasites vulnerable to host population declines that may not immediately threaten the hosts themselves.

Table 1: Factors Influencing Parasite Vulnerability to Coextinction

| Factor | Impact Mechanism | Example |

|---|---|---|

| High Host Specificity | Limits adaptability to alternative hosts; complete dependency on single host species | Eriophyoid mites (80% single-host dependent) [1] |

| Complex Life Cycles | Require multiple specific host species; disruption at any stage prevents completion | Trematodes requiring intermediate hosts [3] |

| Low Dispersal Ability | Limits capacity to locate new hosts or populations | Permanent mammalian mites lacking free-living stages [5] |

| Specialized Transmission | Dependent on specific behaviors, ecological interactions, or environmental conditions | Monarch butterfly protozoan requiring larval food plant [6] |

Quantitative Evidence and Case Studies

Eriophyoid Mites and Host Plants

The eriophyoid mites (Prostigmata: Eriophyoidea) present a compelling case study in parasite coextinction risk. These microscopic mites demonstrate extreme host specificity and have been documented from a enormous range of annual and perennial plants [1]. With a global species estimate of at least 250,000, and potentially much higher, this group represents a significant component of global biodiversity that is vulnerable to coextinction. The ongoing destruction of natural habitats, particularly tropical forests, coupled with climate change, poses extreme threats to these mites due to their dependency on host plants [1]. Notably, with approximately one-third of Earth's plant species currently threatened with extinction, the potential for massive coextinction events among eriophyoid mites is substantial [1].

Mammalian Parasitic Mites

Research on permanently parasitic mammalian mites provides quantitative insights into host-parasite relationships and extinction risks. A comprehensive global dataset encompassing 1,984 mite species and 1,432 mammal species reveals critical patterns in parasite host range and vulnerability [5]. Analysis shows that single-host parasites face higher extinction risk as their survival is entirely dependent on their host's persistence [5]. Certain mammalian lineages, including Rodentia (rodents), Chiroptera (bats), and Carnivora, are overrepresented as hosts for mites in the multi-host risk group, highlighting both their vulnerability to parasitic infestations and their potential role as reservoirs for parasites that could shift to new hosts [5].

Table 2: Documented and Projected Coextinction Risks Across Parasite Groups

| Parasite Group | Host Association | Conservation Status | Projected Loss |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eriophyoid Mites | Highly host-specific (80% on single plant species) | Threatened by habitat destruction and climate change | Many thousands of species disappearing in current extinction event [1] |

| Mammalian Mites | Varying specificity; ~50% single-host | Vulnerable to host population declines | Single-host species at higher extinction risk; some predicted to become multi-host [5] |

| Wildlife Parasites (General) | Diverse dependencies | Threatened by ecosystem disturbance, pollution, climate change | Significant proportion threatened or already extinct [3] |

Methodological Framework for Studying Coextinction

Experimental Approaches

Understanding coextinction processes requires both observational studies and controlled experiments. Research on the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) and its protozoan parasite Ophryocystis elektroscirrha (OE) provides a methodological template for investigating host density effects on parasite transmission [6].

Experimental Protocol: Host Density and Parasite Transmission

Host Preparation: Source monarch families from non-inbred genetic stocks. Collect eggs on greenhouse-reared milkweed plants (Asclepias curassavica).

Treatment Assignment: Randomly assign 2nd instar larvae to density treatments:

- Singles: one caterpillar per plant

- Doubles: two caterpillars per plant

- Tens: ten caterpillars per plant

Parasite Exposure: Apply parasite spores at varying doses:

- Control: 0 spores

- Low dose: 10-100 spores (Experiment 1) or 100-1,000 spores (Experiment 2)

- High dose: 100 spores (Experiment 1) or 1,000-10,000 spores (Experiment 2)

Measurement Parameters:

- Infection rates (proportion of infected hosts)

- Parasite load (spore count per infected adult)

- Adult lifespan and morphological characteristics

Statistical Analysis: Compare infection metrics across density treatments to test for foraging dilution effects [6].

This experimental design demonstrated that crowded hosts can reduce per-capita infection risk through foraging dilution, where crowded caterpillars removed more parasites from their environment, thereby lowering individual exposure [6].

Predictive Modeling of Host Range Expansion

Advanced statistical modeling approaches enable prediction of which single-host parasites are most likely to become multi-host, representing a key methodology for anticipating coextinction risks.

Modeling Protocol: Predicting Host Range Expansion

Data Assembly: Compile comprehensive dataset of host-parasite associations (e.g., 1,984 mite species vs. 1,432 mammal species).

Predictor Variables: Incorporate parameters related to:

- Parasite biology (feeding specialization, immune system interaction)

- Host traits (phylogenetic similarity, spatial co-distribution)

- Environmental factors (temperature, humidity, habitat disturbance)

Addressing Data Challenges:

- Implement down-sampling or up-sampling to correct class imbalance

- Apply positive-unlabeled learning to account for unobserved multi-hosts

- Weight data by publication counts to address sampling bias

Model Validation: Use k-fold cross-validation with independent test datasets to evaluate predictive performance.

Risk Assessment: Identify single-host parasite species with high probability of host range expansion and host lineages enriched with risk-group mites [5].

The most effective model identified statistically significant predictors including the parasite's contact level with the host immune system, host phylogenetic similarity, and spatial co-distribution [5].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Tools

| Research Tool | Application | Function in Coextinction Research |

|---|---|---|

| Host-Parasite Databases | Compilation of known associations | Baseline data for modeling extinction risks and host specificity [5] |

| Molecular Identification | Species delimitation and phylogenetics | Accurate identification of parasite species and evolutionary relationships [5] |

| Environmental Chamber Systems | Controlled experiments | Maintain standardized conditions for host-parasite interaction studies [6] |

| Statistical Modeling Platforms | Predictive analytics | Forecast host range expansion and identify at-risk parasite species [5] |

| Geographic Information Systems | Spatial analysis | Map host distributions and identify areas of high coextinction risk [5] |

Conservation Implications and Future Directions

The conservation of parasitic biodiversity requires a fundamental shift in perspective, recognizing parasites as meaningful conservation targets rather than undesirable entities to be eliminated [3] [4]. Arguments for parasite conservation include their intrinsic value as components of biodiversity, their functional roles in ecosystem processes, and their value as indicators of ecosystem health [4]. Effective conservation strategies must address the unique challenges of preserving species that exist in dependent relationships.

A proposed decision tree for integrating parasites into conservation planning begins with assessing whether the parasite is host-specific, then evaluates the conservation status of required hosts, identifies critical resources needed for parasite transmission, and finally implements targeted conservation actions [4]. This approach emphasizes that conserving parasites requires maintaining access to suitable hosts and the ecological conditions that permit successful transmission [4].

Ecosystem-centered conservation may prove more effective than species-centered approaches for preventing parasite extinctions, as intact ecosystems maintain the complex ecological networks necessary for host-parasite dynamics [4]. However, current criteria for identifying protected areas typically lack information on the ecological conditions required for effective parasite transmission, representing a critical gap in conservation planning [4].

Coextinction represents a potent threat to global parasite biodiversity, with potentially thousands of species disappearing unnoticed as their hosts decline. The vulnerability of parasites to coextinction is primarily determined by their host specificity and the population trajectories of their required hosts. Understanding these linked fates through rigorous experimental and modeling approaches provides the foundation for effective conservation strategies that recognize parasites as integral components of ecological communities. As the biodiversity crisis intensifies, incorporating parasite conservation into broader conservation frameworks becomes increasingly urgent to preserve the ecological and evolutionary processes that sustain life on Earth.

The global biodiversity crisis extends beyond the loss of charismatic vertebrate species to include the less visible, but ecologically significant, decline of parasitic organisms. This case study examines the quantification of historical parasite loss in the critically endangered kākāpō parrot (Strigops habroptila) through ancient DNA (aDNA) analysis, establishing a paradigm for understanding coextinction dynamics. Research indicates that parasite coextinction represents a major, yet underdocumented, component of overall biodiversity loss [7]. As host populations decline, their dependent parasites often face an extinction debt, disappearing even before their hosts do due to diminished transmission opportunities [8] [9]. The kākāpō, with its comprehensive scat and coprolite record spanning centuries of population decline and intensive conservation management, provides an unparalleled model system for quantifying these hidden extinctions through paleogenomic approaches [7].

Results: Quantifying Parasite Loss in the Kākāpō

Magnitude of Parasite Disappearance

Analysis of kākāpō fecal samples revealed a dramatic reduction in parasite diversity between historical and contemporary populations, with over 80% of parasite taxa detected in pre-1990 samples no longer present in modern populations [8] [9]. This represents the loss of 13 of the original 16 parasite taxa identified in the historical record [7].

Table 1: Timeline of Parasite Loss in Kākāpō Populations

| Time Period | Parasite Taxa Present | Parasite Taxa Lost | Cumulative Loss |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-1990 (Historical) | 16 | 0 | 0% |

| Pre-1990 to 1990 | 7 | 9 | 56% |

| Post-1990 (Management Era) | 3 | 4 | 81% |

Patterns of Taxon Vulnerability

The research identified differential vulnerability among parasite species, with four of seven recurrent, possibly host-specific parasite taxa (57%) undetected in contemporary samples and potentially extinct [7]. This suggests that specialist parasites with complex life cycles or narrow host ranges face disproportionately higher extinction risk compared to generalist species.

Table 2: Parasite Community Composition Across Time Periods

| Parasite Characteristic | Pre-1990 Community | Contemporary Community | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Taxa Richness | 16 | 3 | -81% |

| Recurrent/Host-Specific Taxa | 7 | 3 | -57% |

| Taxonomic Diversity | High | Low | Severe reduction |

| Transmission Potential | Stable | Diminished | Significantly reduced |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Ancient Parasite DNA Analysis

Sample Collection and Preservation

The research utilized scats and coprolites from fourteen localities, with samples dating from over 800 years ago to recent specimens [7]. This temporal spread enabled comparison of parasite communities before and after the kākāpō's near-extinction and subsequent intensive management. Proper sample preservation is crucial for aDNA survival, with dry, cool, and stable conditions providing optimal preservation environments.

DNA Extraction and Purification

The sediment DNA (sedaDNA) extraction protocol followed established ancient DNA methodologies with specific modifications for parasite recovery [10] [11]:

- Subsampling: 0.25g of material was subsampled in dedicated ancient DNA facilities to prevent contamination [10] [11].

- Chemical Disruption: Samples were placed in garnet PowerBead tubes with lysis buffer containing 750 μL of 181 mM NaPO₄ and 121 mM guanidinium isothiocyanate [10] [11].

- Mechanical Disruption: Bead beating for 15 minutes physically broke down organo-mineralized content and resilient parasite eggs, significantly improving DNA recovery [10].

- Protein Digestion: Proteinase K was added after bead beating, with tubes continuously rotated in an oven at 35°C overnight [10] [11].

- Inhibitor Removal: Samples were centrifuged at 4500 rpm at 4°C for 6-24 hours to precipitate enzymatic inhibitory compounds common in sediment and fecal samples [10].

- DNA Binding and Elution: Silica-based purification methods following Dabney et al. protocols were used, with final elution in 50 μL elution buffer [10].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Double-Stranded Library Construction: DNA libraries were prepared for Illumina sequencing using a double-stranded method with modifications for blunt end repair [10].

- Metabarcoding Approach: Ancient DNA metabarcoding was employed to target and amplify parasite-specific genetic markers across multiple samples [7].

- Microscopic Analysis: Complementary microscopic examination of samples provided morphological confirmation of parasite remains and enabled a multimethod approach to parasite identification [7].

Data Analysis and Authentication

- Metagenomic Classification: Initial screening assigned sequencing reads to taxonomic groups.

- Damage Pattern Authentication: Characteristic ancient DNA damage patterns were used to distinguish authentic ancient sequences from modern contamination [12].

- Reference Database Comparison: Curated, decontaminated reference databases are essential for accurate parasite identification, as standard databases often contain contaminated sequences that yield false positives [13].

Diagram 1: Ancient Parasite DNA Analysis Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the major steps in recovering and analyzing parasite DNA from historical specimens, from sample collection through data interpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Ancient Parasite DNA Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Guanidinium Isothiocyanate | Chemical disruption of cells and nucleoproteins | Component of lysis buffer for releasing DNA from complex matrices [10] |

| Proteinase K | Protein digestion | Breaks down structural proteins and nucleases after mechanical disruption [10] [11] |

| Silica Columns | DNA binding and purification | Selective binding of DNA while removing PCR inhibitors [10] |

| Garnet PowerBeads | Mechanical disruption | Physical breakdown of tough parasite eggs and sediment matrices [10] |

| NaPO₄ Buffer | Lysis buffer component | Maintains optimal pH and ionic conditions for DNA release [10] |

| Illumina Sequencing Chemistry | High-throughput sequencing | Enables parallel sequencing of multiple samples [10] |

| Parasite-Specific Primers | Target enrichment | Amplification of parasite DNA from complex mixtures [7] |

| ParaRef Database | Taxonomic reference | Decontaminated reference database for accurate parasite identification [13] |

Technical Considerations and Methodological Challenges

Contamination Management in Reference Databases

The pervasive issue of contamination in public genome databases presents significant challenges for accurate parasite detection. Recent research has demonstrated that over 50% of scaffold-level and contig-level parasite genome assemblies contain contaminating sequences, with some assemblies consisting entirely of contaminant DNA from bacteria or host species [13]. The development of decontaminated reference databases like ParaRef, created by systematically screening 831 published endoparasite genomes, significantly reduces false detection rates and improves overall detection accuracy in metagenomic studies [13].

Multimethod Validation

Relying solely on genetic approaches may provide an incomplete picture of historical parasite communities. Studies comparing microscopy, ELISA, and sedimentary ancient DNA demonstrate that a multimethod approach provides the most comprehensive reconstruction of parasite diversity [10] [11]. Microscopy proves most effective for identifying helminth eggs, ELISA provides superior sensitivity for detecting protozoa that cause diarrhea, while sedimentary DNA analysis can identify additional taxa and confirm species identification [11].

Diagram 2: Multimethod Validation Strategy. A combined approach utilizing complementary techniques provides the most comprehensive assessment of historical parasite communities, leveraging the unique advantages of each methodology.

Implications for Parasite Biodiversity and Conservation

The kākāpō case study demonstrates that vertebrate population declines can result in permanent parasite loss, with unknown consequences for host health and ecosystem functioning [7]. The research documented that parasite extinctions may be far more prevalent than previous estimates suggested, highlighting the need for a "global parasite conservation plan" to address these hidden losses [8] [9].

From a conservation perspective, these findings reveal that even successfully recovering host populations may harbor only fractions of their original parasite communities [8]. This has potential implications for host immune system development, as parasites may help with immune function and compete to exclude more harmful parasites [8] [9]. The kākāpō paradigm thus provides a quantitative framework for assessing coextinction risk across endangered species worldwide and emphasizes the importance of considering dependent organisms in conservation planning.

The intricate and often fragile relationships between hosts and their parasites are being fundamentally reshaped by anthropogenic global change. Invasive species and habitat loss and fragmentation (HLF) act as synergistic "threat multipliers," disrupting co-evolved interactions and vacating ecological niches for parasites [14] [15]. While often perceived negatively, parasites are integral components of ecosystem biodiversity, contributing to stable food webs and regulating host populations [16]. The erosion of this parasitic fauna through the vacated niche phenomenon carries profound implications for ecosystem health, disease dynamics, and conservation outcomes.

This technical guide synthesizes current research to delineate the mechanistic pathways through which invasive species and HLF vacate parasite niches. We frame these processes within the broader context of parasite biodiversity conservation, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a foundational understanding of the underlying ecological theory, key methodological approaches for its study, and the consequent implications for disease emergence and ecosystem management.

Theoretical Frameworks and Key Hypotheses

Understanding host-parasite dynamics in changing environments requires a synthesis of several ecological hypotheses, which provide predictive frameworks for research and intervention.

The Vacated Niche Hypothesis

The Vacated Niche Hypothesis posits that the extinction, elimination, or loss of a parasite species leaves an ecological niche open that can be invaded and exploited by another species, most likely a taxonomically or ecologically similar parasite [14]. This hypothesis draws on the principle that related parasite species compete more strongly for resources within hosts, including direct competition for space and nutrients and indirect immune-mediated competition [14]. The niche overlap among related parasites suggests that host susceptibility to one parasite is likely similar for its relatives, enabling a new parasite to exploit the host more successfully in the absence of competitors. This hypothesis moves beyond classic case studies (e.g., smallpox eradication and subsequent monkeypox concerns) to establish a general pattern in parasite community assembly [14].

The Enemy Release Hypothesis

The Enemy Release Hypothesis (ERH) is a cornerstone of invasion ecology, stating that invasive species are successful, in part, because they escape natural enemies—including parasites—from their native range [14] [17]. This release from regulation often facilitates rapid population growth and expansion of the invader. The ERH is intrinsically linked to the Vacated Niche Hypothesis, as the process of parasite loss (enemy release) creates the vacated niches that can subsequently be filled by new parasite acquisitions [14].

Synthesizing the Frameworks

These hypotheses are not mutually exclusive but represent interconnected stages in a dynamic process. Enemy release through parasite loss creates vacated niches. The filling of these niches through the acquisition of new parasites can then lead to transient enemy release, where the initial competitive advantage of the invader is gradually eroded [14]. Furthermore, habitat fragmentation can disrupt the delicate co-evolutionary arms race between hosts and parasites, potentially pushing one or both parties toward extinction and creating further vacant niche space [15]. The conceptual relationship between these drivers and outcomes is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Conceptual model of threat multiplier pathways. This diagram illustrates the logical relationships showing how primary anthropogenic drivers lead to vacated parasite niches and ecological consequences, integrating the Enemy Release and Vacated Niche hypotheses.

Quantifying Niche Vacancy: Methodologies and Experimental Approaches

Robust, multi-faceted methodologies are required to detect and quantify vacated parasite niches and their consequences.

Macroecological Analysis and Taxonomic Null Modeling

Large-scale analyses of host-parasite associations across native and invasive ranges provide powerful evidence for niche vacancy dynamics.

Data Acquisition and Preparation:

- Primary Data Source: The Global Mammal Parasite Database (GMPD) is a core resource, containing meticulously curated records of parasite associations for terrestrial mammals [14] [18].

- Host-Parasite Fate Classification: For each invasive host species, parasites are categorized into four fates based on their presence across the host's native and introduced ranges:

- Retention: Parasites carried with the host during invasion.

- Loss: Parasites not carried with the host during invasion.

- Acquisition: Parasites newly picked up by the host post-invasion.

- Non-acquisition: Parasites not picked up by the host post-invasion [14].

- Net Enemy Release Calculation: The difference in parasite species richness between the native and invasive ranges is calculated to test for net enemy release [14].

Taxonomic Null Modeling: This novel analytical approach tests whether acquired parasites are taxonomically more similar to lost parasites than expected by chance.

- Taxonomic Tree Construction: For each parasite group (arthropods, bacteria, helminths, protozoa, viruses), a taxonomic tree is built based on their Linnaean classification [18].

- Pairwise Distance Calculation: The taxonomic distance between each lost parasite and each acquired parasite is computed.

- Null Distribution Generation: Random sets of parasites are drawn from the regional pool to create a null distribution of expected pairwise taxonomic distances.

- Z-score Calculation: A z-score is computed to determine if the observed mean distance between lost and acquired parasites is significantly smaller than the null expectation, indicating taxonomic replacement [14] [18].

Table 1: Key Quantitative Findings from Macroecological Studies

| Study System | Key Metric | Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive Terrestrial Mammals [14] | Net Parasite Richness | Significant reduction in parasite species richness in invasive ranges | Supports the Enemy Release Hypothesis |

| Invasive Terrestrial Mammals [14] | Null Model Z-score | Significantly negative z-scores across multiple parasite taxa | Acquired parasites are taxonomically similar to lost ones, supporting the Vacated Niche Hypothesis |

| Cane Toad (Rhinella marina) [19] | Realized Niche Overlap (Schoener's D) | Low niche equivalence (D = 0.28) between native and invasive ranges | Demonstrates a realized niche shift in the invaded range |

Individual-Based Simulation of Coevolutionary Dynamics

Computational models are essential for studying how HLF affects coevolutionary processes that are otherwise impossible to observe directly.

Model Framework for Cuckoo-Host Brood Parasitism: This individual-based model simulates the antagonistic coevolution between a brood parasite (e.g., common cuckoo, Cuculus canorus) and its host, incorporating both stochastic inheritance and reinforcement learning [15].

Key Parameters and Initialization:

- Virtual Populations: Construct virtual cuckoo and host groups with parameters for lifespan, egg number, and behavioral probabilities (e.g., parasitism success, host rejection) [15].

- Stochastic Processes: Incorporate natural variability using:

- Truncated normal distributions for probabilistic parameters (e.g., hatching rates).

- Truncated Weibull distributions for long-tailed variables (e.g., lifespan).

- Truncated Poisson distributions for discrete variables (e.g., egg number) [15].

Simulation Workflow: The simulation proceeds iteratively over a given number of years, modeling key biological processes. Figure 2 outlines the core workflow and its integration with habitat constraints.

Figure 2. Coevolutionary simulation workflow. This experimental workflow diagrams the key processes in an individual-based simulation model for studying how habitat loss and fragmentation (HLF) affects host-parasite coevolution, based on cuckoo-host systems.

Application to HLF: The model is run under different habitat scenarios (intact, moderate HLF, severe HLF). The primary finding is that severe HLF significantly narrows the range of host rejection rates that allow for the stable coexistence of both cuckoos and hosts, thereby increasing the extinction risk for the parasite and disrupting the coevolutionary arms race [15].

Experimental Manipulation of Parasitism and Competition

Controlled experiments are critical for establishing causality and elucidating the mechanisms underlying patterns observed in the field.

Protocol: Effects of Parasitism on Invasive vs. Native Plant Competition [20]

Objective: To test whether the parasitic plant Cuscuta grovonii differentially affects the competitive abilities of invasive and native host plants.

Experimental Design:

- Factors: The experiment employs a fully factorial design with three factors:

- Host Plant Invasive Status: Three invasive species vs. three native congeners.

- Parasitism: Presence or absence of the parasitic plant Cuscuta grovonii.

- Competition Status: Host plant grown alone or in competition with a native competitor (Coix lacryma-jobi).

- Replication: Six replicates per treatment combination [20].

Key Procedures:

- Plant Cultivation: Host plants and the competitor are grown from seeds or cuttings in a standardized substrate under controlled greenhouse conditions.

- Parasitism Treatment: Four weeks after transplantation, a 10 cm stem of C. grovonii is wound around the stems of host plants in the parasitism treatment group.

- Harvest and Measurement: Aboveground biomass of all plants is harvested, dried, and weighed after a predetermined growth period [20].

Data Analysis:

- Relative Competition Intensity (RCI): Calculated as

(Biomass_alone - Biomass_competition) / Biomass_aloneto measure the impact of competition on a plant's growth. - Deleterious Effect (DE): Calculated as

(Biomass_parasitized - Biomass_unparasitized) / Biomass_unparasitizedto quantify the harm caused by the parasite [20].

Key Finding: Parasitism increased the competitive ability of invasive plants but did not affect that of native plants, suggesting that parasitic plants can inadvertently facilitate plant invasion by differentially impacting competitors [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Materials and Reagents for Studying Vacated Niches

| Tool / Reagent | Primary Function | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Global Mammal Parasite Database (GMPD) | Provides structured, global data on host-parasite associations for macroecological analysis. | Serves as the primary data source for analyzing parasite retention, loss, and acquisition in invasive mammals [14] [18]. |

| WorldClim Bioclimatic Variables | Supplies high-resolution global climate data for ecological niche modeling. | Used to extract bioclimatic data for ecoregions associated with native and invasive host ranges to control for environmental effects [18]. |

| PanTHERIA Database | A comprehensive database of life history, ecology, and geographic traits for mammals. | Provides species-level trait data (e.g., body mass, litter size) for use as covariates in enemy release analyses [18]. |

| Molecular Assays (e.g., PCR, NGS) | Enables precise taxonomic identification of parasites and detection of co-infections. | Critical for identifying host-specific parasites in conservation contexts and for studying parasite community composition [16]. |

| R Statistical Environment | An open-source platform for statistical computing and graphics. | The core software used for data cleaning, analysis, null modeling, and visualization in contemporary parasitology research [18]. |

Implications for Parasite Biodiversity and Conservation

The vacated niche phenomenon directly threatens parasite biodiversity, necessitating a paradigm shift in conservation science.

- Co-extinction Risk: Host-specific parasites are particularly vulnerable to co-extinction if their host population declines or disappears. Many such parasites may be lost before they are even known to science, especially those associated with endangered hosts [16].

- Conservation Translocations: Translocating endangered hosts presents an opportunity for holistic conservation that includes their parasites. Success in co-translocating parasites has been variable, driven by factors that are not yet fully predictable, highlighting a critical need for integrated monitoring and reporting [16].

- Shifting Perceptions and Practice: Effective parasite conservation requires reshaping public and scientific perceptions to recognize parasites as intrinsic components of biodiversity. Initiatives like the Global Parasitologist Coalition are developing innovative science communication tools—such as parasite personality quizzes and trading cards—to bridge the gap between ecological research and public understanding [16].

Invasive species and habitat fragmentation act as potent threat multipliers, driving the vacancy and subsequent taxonomic reshuffling of parasite niches through defined ecological pathways. The interplay of the Enemy Release and Vacated Niche hypotheses provides a robust framework for understanding these complex dynamics, which can be quantitatively investigated through macroecological null modeling, individual-based simulations, and controlled experimentation.

The implications extend beyond pure ecology to influence emerging infectious disease risk, the success of biocontrol efforts, and the design of effective conservation strategies. A proactive approach to research, integrating the methodologies detailed in this guide, is essential for predicting and mitigating the consequences of these changes. Ultimately, the conservation of ecosystem health in the Anthropocene will depend on our ability to conserve not only the hosts but also their diverse and ecologically significant parasitic fauna.

Parasites have historically been overlooked in ecology, often perceived as mere consumers that negatively impact their hosts. However, a paradigm shift is occurring as research reveals their profound influence on ecosystem structure and function. Parasitism represents the most widespread life-history strategy in nature, arguably more common than traditional predation as a consumer lifestyle [21]. Despite constituting approximately 40% of described species [22], parasites have been conspicuously absent from traditional ecological models and conservation frameworks. This whitepaper synthesizes current understanding of parasitic biodiversity and its functional significance, arguing for a systematic re-evaluation of parasites as integral components of ecosystem diversity beyond their biomass contributions alone.

The ecological interactions of parasites often challenge observation, as many live secretively in intimate contact with their hosts [21]. This cryptic nature has historically led to the assumption that parasites play less important roles in community ecology than free-living organisms. Yet advances in disease ecology demonstrate that parasites exert influences that equal or surpass those of free-living species in shaping community structure [21]. This document frames parasite diversity within broader biodiversity and conservation research, providing technical guidance for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to understand the complex roles these organisms play in ecosystem functioning.

The Ecological Significance of Parasites

Parasites as Regulators of Ecosystem Processes

Parasites function as critical regulators across multiple levels of ecological organization, from host individuals to entire ecosystems. Their effects extend beyond host pathology to include mediating species interactions, energy flow, and nutrient cycling.

Trophic Interactions: Parasites engage in specialized predation and serve as important prey sources. Predators on islands in the Gulf of California are significantly more abundant on islands with sea bird colonies because they feed on bird ectoparasites [21]. This demonstrates how parasites can represent substantial energy flows within food webs despite their small size and cryptic nature.

Food Web Architecture: Incorporating parasites into food webs dramatically alters web topology. In a California salt marsh food web, parasites were involved in 78% of all links and increased connectance estimates by 93% [21]. This enhanced complexity has potential implications for web stability and challenges the traditional Eltonian pyramid model, suggesting parasites may occupy the pinnacle when their feeding above host levels is considered [21].

Ecosystem Energetics: Contrary to assumptions of negligible contribution, parasite biomass can be substantial at ecosystem scales. In some estuarine systems, parasite biomass is comparable to that of top predators, with yearly productivity of trematode parasites exceeding bird biomass [21]. Similarly, plant fungal pathogen biomass equals that of herbivores in grassland ecosystems, with top-down control by pathogens more important than herbivory in predicting grass biomass [21].

Table 1: Quantitative Assessments of Parasite Functional Significance

| Ecosystem Role | System | Measurement | Impact | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Web Complexity | California Salt Marsh | Link Involvement | Parasites involved in 78% of links | [21] |

| Biomass Comparison | Estuarine Systems | Trematode Productivity | Higher than bird biomass | [21] |

| Population Control | African Ungulates | Rinderpest Elimination | Herbivore populations increased several-fold | [22] |

| Primary Production Regulation | Minnesota Grasslands | Fungal Pathogen Effects | Stronger control than herbivory | [21] |

Biodiversity Mediation Through Parasitism

Parasites significantly influence biodiversity through multiple mechanisms, with effects that can be both negative and positive depending on ecological context.

Parasite-Mediated Competition: Parasites alter competitive outcomes between host species. A classic example involves the displacement of red squirrels by grey squirrels in Britain, potentially facilitated by a parapoxvirus [21]. The virus infects both species, but native red squirrels experience severe effects while invasive grey squirrels show minor symptoms, reducing local biodiversity through competitive exclusion.

Coexistence Facilitation: Conversely, parasites can promote biodiversity by allowing competitively inferior species to persist. On St. Maarten, Anolis gingivinus outcompetes Anolis wattsi except where the dominant lizard is heavily parasitized by Plasmodium azurophilum [21]. This suggests malaria reduces competitive ability, enabling coexistence.

Keystone Species Effects: The ecological impacts of parasites are particularly pronounced when they infect keystone species. Caribbean Diadema urchins experienced mass mortality from microbial pathogens, eliminating their roles as grazers and bioeroders [21]. This triggered a phase shift from coral- to algal-dominated reefs, demonstrating how parasites can indirectly restructure entire ecosystems.

The introduction and subsequent removal of rinderpest in African ungulates provides another compelling example. Following its eradication, herbivore abundance increased dramatically, triggering increases in predator populations, reductions in fire frequency due to more efficient grazing, and a shift from grassland to woodland ecosystems [22]. The Serengeti transformed from a carbon source to a carbon sink, illustrating profound ecosystem-level consequences of parasite removal [22].

Quantitative Assessment of Parasite Diversity

The Scale of Unrecognized Diversity

The true extent of parasite diversity remains largely unknown, with current estimates suggesting the majority of species await discovery and description. Helminth parasites alone demonstrate this knowledge gap, with global totals estimated at 100,000–350,000 species, of which 85–95% are unknown to science [23]. This staggering lack of description has profound implications for understanding ecosystem complexity and function.

Analysis of accumulation curves for helminth parasites reveals no evidence of a slowing description rate, indicating we remain far from a complete catalogue [23]. Since 1897, an average of 163 helminth species have been described annually, with a linear trend (R² = 0.991, p < 0.001) showing no sign of approaching an asymptote [23]. At current rates, comprehensive sampling and description would require centuries, highlighting the immense scale of the task.

Table 2: Global Diversity Estimates for Helminth Parasites of Vertebrates

| Taxonomic Group | Estimated Global Richness | Proportion Undescribed | Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helminths (total) | 100,000–350,000 species | 85–95% | Endoparasites only | [23] |

| Nematodes | Not specified | Majority | Potential for 80M+ species of nematode parasites of arthropods | [23] |

| Amphibian/Reptile Parasites | Not specified | Most poorly described | Sampling priority | [23] |

| Bird/Bony Fish Parasites | Not specified | Majority of undescribed species | Largest pool of unknown diversity | [23] |

Biases in Research Effort

Research on parasite diversity suffers from significant taxonomic and geographical biases that limit comprehensive understanding. Analysis of over 2,500 helminth species reveals that research effort correlates with factors unrelated to ecological significance [24].

Taxonomic Bias: Descriptions of acanthocephalans and nematodes receive more citations than other helminths, while cestodes are less frequently mentioned in literature [24]. This creates uneven knowledge bases across taxonomic groups.

Host Conservation Status: Helminths infecting host species of conservation concern receive less research attention, likely due to constraints associated with working with threatened animals [24]. This creates a critical gap in understanding parasites in vulnerable ecosystems.

Geographical Disparities: Research effort correlates negatively with human population size of the country where a species was discovered, though not with economic strength [24]. This suggests sampling biases toward less populated regions regardless of economic development.

Description Practices: Species originally described by many co-authors subsequently attract more research effort than those described by few authors [24], indicating sociological factors influence scientific attention.

Most concerning is the finding that the majority of parasite species are not studied again after their initial discovery and description [24]. This lack of follow-up research severely limits understanding of parasite ecology, evolution, and ecosystem function.

Methodological Approaches for Parasite Biodiversity Research

Molecular Genetic Tools for Parasite Identification

Modern parasitology employs sophisticated molecular techniques to characterize parasite diversity, moving beyond traditional morphological approaches. These methods have revolutionized our ability to identify species, strains, and phylogenetic relationships.

Molecular Workflow for Parasite Diversity Studies

Microsatellite Analysis Protocol: Microsatellite loci provide abundant, putatively neutral, and highly polymorphic genetic markers ideal for analyzing parasite diversity [25]. The following protocol is adapted from Plasmodium falciparum genetic diversity studies:

Sample Collection: Obtain dried blood spots or tissue samples from infected hosts [25].

DNA Extraction: Use commercial kits (e.g., DNeasy Blood and Tissue extraction kit, Qiagen) following manufacturer protocols [25].

Semi-nested PCR Amplification: Amplify 12 microsatellite loci (Poly A, PfG377, TA81, ARA2, TA87, TA40, TA42, 2490, TA1, TA60, TA109, PfPk2) using fluorescently labeled primers [25].

Fragment Analysis: Pool labeled PCR products for electrophoresis on genetic analyzers (e.g., ABI 3500XL Genetic Analyzer) [25].

Data Processing: Use peak scanning software (e.g., PeakScanner, GeneMarker) to determine allele lengths and peak heights [25]. Consider minor peaks >20% the height of the predominant peak as multiple alleles.

Population Genetic Analysis: Calculate expected heterozygosity (He), allelic richness (Ar), effective alleles (Ne), and differentiation indices (Fst) using specialized software (e.g., GENALEX, ARLEQUIN, FSTAT) [25].

Key Genetic Metrics:

- Expected Heterozygosity (He): Probability of infection by two parasites with different alleles at a locus, calculated as He = n/(n-1), where n = number of isolates, p = allele frequency [25].

- Fixation Index (Fst): Measures population divergence, with values 0-0.05 indicating little differentiation, 0.05-0.15 moderate, and 0.15-0.25 great differentiation [25].

- Linkage Disequilibrium: Non-random association of alleles across loci, typically weaker in high-transmission regions due to frequent recombination [25].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Parasite Biodiversity Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Specific Example | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) | Nucleic acid purification | General parasite DNA isolation [25] |

| Microsatellite Primers | 12 P. falciparum loci (Poly A, PfG377, etc.) | Genetic marker amplification | Population genetics, strain differentiation [25] |

| Genetic Analyzer | ABI 3500XL System | Fragment separation and detection | High-resolution genotyping [25] |

| Analysis Software | GENALEX, ARLEQUIN, FSTAT | Population genetic statistics | Diversity quantification, structure analysis [25] |

| Museum Collections | US National Parasite Collection | Reference specimens | Taxonomic validation, historical comparisons [23] |

| Host-Parasite Databases | NHM Host-Parasite Database | Occurrence records | Distribution patterns, host associations [23] |

Conservation Implications and Future Directions

The Case for Parasite Conservation

The conservation of parasite biodiversity presents both ethical and practical challenges, yet compelling arguments support their inclusion in conservation planning.

Intrinsic Value: From an ecological perspective, parasites possess objective intrinsic value due to their evolutionary heritage and potential, independent of human valuation [26]. This philosophical foundation suggests parasites deserve protection equally with their hosts when equally endangered.

Ecosystem Services: Parasites contribute to supporting, regulating, and provisioning ecosystem services through their roles in population regulation, nutrient cycling, and community organization [26]. They can act as biological indicators of ecosystem health due to their sensitivity to environmental change [26].

Functional Roles: Evidence demonstrates that parasites mediate predatory and competitive interactions, shape community structure and diversity, enhance food web complexity, and influence energy flow [26]. Loss of parasite diversity potentially disrupts these critical functions.

The extinction of the California condor louse (Colpocephalum californici) during captive breeding efforts illustrates the conservation dilemma [26]. The investment of over $115 million across 35 years saved one free-living species but cost one parasitic species, raising questions about conservation priorities and the ecological consequences of single-species parasite extinction.

Threats to Parasite Diversity

Parasites face numerous threats with extinction rates potentially exceeding those of their hosts, yet they remain dramatically underrepresented on threatened species lists.

Invasive Species Impact: Invasive mammals reduce parasite diversity by replacing native hosts, supporting the "vacated niche hypothesis" [27]. Invasive mammals typically carry fewer parasite species than native counterparts, causing declines in parasites adapted to native hosts [27].

Host Population Declines: As host species decrease in abundance and distribution, their specific parasites face heightened extinction risk. This co-extinction process represents a largely hidden biodiversity crisis [28].

Habitat Fragmentation: Parasites with complex life cycles requiring multiple hosts are particularly vulnerable to habitat disruption that interferes with transmission pathways [26].

Climate Change: Alterations in temperature and precipitation regimes affect parasite development rates, survival, and transmission, potentially eliminating species unable to adapt or shift distributions [29].

Threats and Conservation Strategies for Parasite Diversity

Research Priorities and Framework

Addressing knowledge gaps in parasite ecology and conservation requires strategic research investment and methodological innovation.

Global Parasite Project: Inspired by initiatives like the Human Genome Project and Global Virome Project, a coordinated global effort could transform parasitology by inventorying parasite diversity at an unprecedented pace [23]. Such an endeavor would require substantial funding but yield invaluable baseline data.

Standardized Methodologies: Developing and implementing standardized sampling protocols, molecular techniques, and data curation standards would enable meaningful cross-system comparisons and meta-analyses [23] [25].

Integrated Conservation Planning: Effective parasite conservation requires maintaining access to suitable hosts and ecological conditions that permit successful transmission [26]. Ecosystem-centered conservation may prove more effective than species-centered approaches.

Parasite-Function Relationships: Research should focus on quantifying how specific parasite taxa influence ecosystem processes and services, moving beyond general observations to mechanistic understanding [29].

The thought experiment of "a world without parasites" reveals potential consequences extending from host individuals to populations, communities, and entire ecosystems [22]. While many uncertainties remain, available evidence suggests such a world would differ profoundly from current reality, emphasizing the need to incorporate parasitic diversity into comprehensive biodiversity conservation strategies.

Parasites represent a critical yet understudied component of global biodiversity with profound influences on ecosystem structure and function. Moving beyond biomass-based assessments to recognize their roles as regulators of trophic interactions, mediators of competition, and contributors to ecosystem stability provides a more comprehensive understanding of ecological complexity. The staggering proportion of undocumented parasite diversity, coupled with biases in research effort and significant threats from environmental change, underscores the urgency of focused research and conservation attention.

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding parasite diversity extends beyond academic interest to practical applications in disease management, ecosystem health assessment, and conservation prioritization. Integrating parasites into ecological models and conservation frameworks will require methodological innovations, standardized approaches, and coordinated global efforts. By re-evaluating parasites as essential components of ecosystem diversity rather than mere pathogens, we advance toward a more complete understanding of the ecological networks that sustain life on Earth.

Advanced Tools for a Hidden World: Genomic, Computational, and Ecological Methods in Parasitology

Paleoparasitology represents a critical interdisciplinary field at the intersection of archaeology, parasitology, and ecology, dedicated to recovering and analyzing parasite remains from archaeological materials and museum specimens. This discipline provides unparalleled insights into the evolutionary history of parasites, their historical distribution, and their long-term relationships with host populations [30]. The value of this research extends far beyond historical documentation; it offers fundamental data for understanding contemporary parasite biodiversity and informing conservation strategies [27]. As modern ecosystems face rapid changes due to human activity, climate change, and species invasions, paleoparasitological data provide crucial baseline information on pre-industrial parasite diversity and host-parasite coevolutionary relationships.

The field has demonstrated particular relevance to the "vacated niche hypothesis" in conservation biology, which posits that invasive species replacing native hosts can dramatically reduce parasite diversity due to host-specificity in many parasite lineages [27]. Recent research confirms that invasive mammals typically carry fewer parasite species compared to their native counterparts, leading to an overall reduction in parasite diversity as native hosts disappear [27]. This erosion of parasite biodiversity represents a significant yet often overlooked conservation concern, as parasites play vital ecological roles in regulating host populations, maintaining ecosystem stability, and contributing to overall biodiversity [27]. This whitepaper provides researchers and drug development professionals with comprehensive methodological guidance for reconstructing historical parasite communities, framing these techniques within contemporary parasite biodiversity and conservation implications research.

Core Materials and Sample Types

Archaeological Source Materials

Paleoparasitological investigations utilize specific archaeological and historical materials to extract parasite evidence. The most common sources include:

- Coprolites: Preserved or desiccated feces from humans and animals, which provide direct evidence of intestinal parasites [31]. These represent the most abundant source material for intestinal parasite studies.

- Mummified Remains: Both natural and intentional mummies, from which pelvic soil, visceral tissues, and intestinal contents can be sampled [30] [32].

- Skeletal Remains: Soil samples collected from the pelvic region and skull or foot areas of skeletons (the latter serving as control samples) [32].

- Sediment Samples: Environmental samples from latrines, middens, and occupation layers containing parasite eggs [33].

Museum Specimens

Historical biological collections, including preserved hosts in museum collections, provide complementary materials for studying more recent parasitological changes and validating molecular techniques [33].

Table 1: Paleoparasitological Sample Types and Their Applications

| Sample Type | Primary Analysis | Key Parasites Recoverable | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Coprolites | Microcopy, ELISA, aDNA | Helminths, Protozoa (e.g., Giardia, Cryptosporidium) | Limited to intestinal parasites; taphonomic bias [31] |

| Animal Coprolites | Microscopy, aDNA | Zoonotic parasites, wildlife parasites | Host identification challenges; ecological context required [31] |

| Mummy Visceral Tissues | Microscopy, immunohistochemistry, aDNA | Tissue-dwelling parasites (e.g., Trypanosoma cruzi) | Rare survival of soft tissues; invasive sampling [30] |

| Pelvic Soil Samples | Microscopy, aDNA | Common helminths (e.g., Ascaris, Trichuris) | Contamination risk; control samples essential [32] |

| Sediment Samples | Microscopy, ELISA | Environmental parasite stages | Difficult to associate with specific hosts [33] |

Critical Methodological Approaches

Conventional Microscopy Techniques

The foundation of paleoparasitology remains the microscopic identification of parasite eggs, larvae, and cysts, leveraging their remarkable preservation potential in archaeological contexts.

- Rehydration-Homogenization-Micro-sieving (RHM) Protocol: This standard approach begins with rehydration in aqueous tri-sodium phosphate solution (0.5% for 48+ hours), followed by homogenization and sequential micro-sieving with meshes typically ranging from 250μm to 20-25μm to concentrate parasite remains [33] [31]. For protozoan parasites like Cryptosporidium with small oocysts (4-6μm), modifications are required as the standard 20-25μm mesh would retain these elements.

- Brightfield Optical Microscopy: Standard light microscopy remains the primary tool for identifying helminth eggs based on size, shape, ornamentation, and biological origin [32]. This technique successfully identified thirty Ascaridida eggs in pelvic samples from 6 individuals (6.7-30% of samples) from Late Iron Age Italian necropolises [32].

- Quantitative Microscopy - Eggs Per Gram (EPG): EPG quantification provides crucial data about infection intensity and enables paleoepidemiological studies [31]. This method applies statistical techniques to estimate parasite prevalence and pathological potential in ancient populations, allowing comparison between archaeological and modern clinical data [31].

Molecular and Immunological Techniques

Advanced molecular methods have dramatically expanded paleoparasitological capabilities, particularly for protozoan parasites that leave minimal microscopic evidence.

- Ancient DNA (aDNA) Analysis: PCR-based amplification of parasite DNA fragments enables species-specific identification and phylogenetic studies [30] [33]. This approach was successfully validated through experimental "mummification" of infected mice at 40°C until complete desiccation, establishing protocols later applied to archaeological material [30]. Paleogenetic analysis complements microscopic examination, though taphonomic factors can limit DNA recovery [32].

- Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA): Immunodiagnostic techniques detect parasite-specific antigens in archaeological remains, proving particularly valuable for protozoan identification [30] [33]. ELISA kits have successfully detected Entamoeba histolytica in ancient samples, revealing its circulation in Western Europe since at least the Neolithic period (5,700 years BP) [33].

- Immunodiagnostic Standardization: Ongoing research focuses on standardizing immunodiagnostic techniques for specific parasites like Leishmania species and developing serological methods for antigen detection in archaeological remains [30].

Table 2: Molecular and Immunological Techniques in Paleoparasitology

| Technique | Target | Sensitivity | Applications | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR | Parasite aDNA fragments | High with preservation | Species identification, evolutionary history | Confirmed T. cruzi infection in 3,500-year-old Brazilian remains [30] |

| ELISA | Parasite antigens | Moderate to High | Protozoan detection (e.g., Giardia, Entamoeba) | Tracked E. histolytica from Neolithic Europe to pre-Columbian Americas [33] |

| Microscopy with Staining | Egg morphology | Limited by preservation | Helminth identification, quantification | Revealed hookworm in pre-Columbian coprolites, questioning Bering Strait migration [30] |

| Whole Genome Sequencing | Complete parasite genomes | Limited by aDNA fragmentation | Evolutionary studies, virulence factors | Emerging approach with technical challenges [33] |

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful paleoparasitological research requires specific reagents and materials tailored to ancient and historical samples.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Paleoparasitology

| Reagent/Material | Composition/Type | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tri-Sodium Phosphate Solution | 0.5% aqueous solution | Rehydrates desiccated coprolites and tissues | 48+ hour rehydration standard; enables microscopic analysis [31] |

| Micro-sieving Meshes | 250μm, 160μm, 20-25μm mesh sizes | Concentrates parasite remains by size | Smaller meshes (≤5μm) needed for Cryptosporidium recovery [33] |

| PCR Master Mix | Custom formulations for aDNA | Amplifies degraded DNA fragments | Requires optimization for inhibitor-rich archaeological samples [30] |

| ELISA Kits | Commercial or custom antibody preparations | Detects parasite-specific antigens | Validated for Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia duodenalis [33] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Silica-column or solution-based | Isulates aDNA from coprolites, tissues, sediments | Must accommodate co-extraction of PCR inhibitors [30] |

| Mounting Media | Glycerol, chemical fixatives | Preserves samples for microscopy | Maintains structural integrity of parasite elements [31] |

Experimental Workflows and Visualization

Integrated Paleoparasitology Workflow

The following workflow diagram illustrates the comprehensive approach to analyzing archaeological materials for parasite evidence, incorporating both traditional and molecular methods:

Pathoecological Analysis Framework

Understanding ancient parasite transmission requires reconstructing the ecological context of parasite-host relationships, as visualized below:

Data Interpretation and Paleoepidemiological Applications

Quantitative Analysis and Overdispersion

A significant advancement in paleoparasitology has been the adoption of quantitative epidemiological approaches, particularly the analysis of parasite overdispersion - the phenomenon where the majority of parasites aggregate in a minority of host populations [31].

- Negative Binomial Distribution: Analysis of coprolites from La Cueva de los Muertos Chiquitos demonstrated that 66% of samples were negative for pinworms, while the ten samples with the highest EPG counts contained 76% of the eggs, mirroring the overdispersion pattern observed in modern clinical studies [31].

- Comparative Paleoepidemiology: Korean studies comparing Joseon Dynasty (1400s-1800s) parasitological data with late 20th-century surveys found consistent distributions of Trichuris trichiura and Ascaris lumbricoides between periods, but higher prevalence and broader distribution of trematodes in ancient times, with hookworm emerging only after the Joseon Dynasty [31].

- Infection Intensity and Pathology: EPG quantification enables estimation of infection intensity and its health implications in past populations, connecting parasitological data with skeletal indicators of stress and disease [31].

Conservation Implications and Biodiversity Research

Paleoparasitological data provide critical insights for contemporary conservation biology, particularly regarding parasite biodiversity loss and ecosystem health.

- Vacated Niche Hypothesis: Invasive mammals carry fewer parasite species than native counterparts, reducing overall parasite diversity as they replace native hosts [27]. This represents a significant biodiversity loss with potential ecosystem consequences.

- Baseline Biodiversity Establishment: Paleoparasitology establishes pre-industrial parasite diversity baselines, essential for measuring anthropogenic impact on parasite communities and understanding coevolutionary histories [27].

- Parasite Conservation Significance: Parasites play vital ecological roles in regulating host populations, maintaining ecosystem stability, and contributing to overall biodiversity, making their conservation an important consideration [27].

Paleoparasitology has evolved from primarily documenting parasite presence to sophisticated quantitative analyses of infection patterns in historical contexts. The integration of microscopic, molecular, and immunological techniques enables comprehensive reconstruction of historical parasite communities, providing unprecedented insights into parasite-host relationships through time. For contemporary researchers and conservation professionals, this historical perspective offers crucial baseline data for understanding current parasite biodiversity loss and its ecosystem implications. As invasive species continue to alter ecosystems worldwide, displacing native hosts and their specific parasites, paleoparasitological data become increasingly valuable for informing conservation strategies that consider the complete ecosystem, including parasitic organisms. The methodological framework outlined in this whitepaper provides researchers with the tools necessary to generate robust data on historical parasite communities, contributing to both scientific understanding of parasite evolution and practical conservation applications in an rapidly changing world.

The accurate characterization of parasite communities is fundamental to understanding infectious disease dynamics, ecosystem health, and the evolutionary history of host-parasite interactions. Traditional morphological methods, while foundational, are often limited by taxonomic resolution, sensitivity, and throughput. The advent of high-throughput sequencing has revolutionized this field, with metabarcoding and shotgun metagenomics emerging as the two primary molecular approaches for profiling parasite diversity across ancient and modern samples [34] [35]. These methods are particularly powerful for studying complex assemblages of eukaryotic endosymbionts—including helminths, protozoa, and other parasites—in both clinical and archaeological contexts [36].

Metabarcoding, a PCR-based approach, amplifies and sequences a short, standardized genomic region to identify taxa present in a sample. In contrast, metagenomics involves the direct, untargeted sequencing of all DNA fragments, providing a potentially unbiased view of the entire genetic content [37] [38]. This technical guide provides an in-depth comparison of these methodologies, details optimized experimental protocols, and discusses their applications and limitations within the broader context of parasite biodiversity research and conservation.

Core Technological Principles and Comparative Analysis

Methodological Workflows

The fundamental workflows for metabarcoding and metagenomics differ significantly, from initial sample processing to final data analysis, each with distinct advantages and challenges. The following diagram illustrates the key steps and decision points in each pathway.

Performance Comparison and Selection Criteria

The choice between metabarcoding and metagenomics involves trade-offs between specificity, sensitivity, cost, and analytical scope. The table below summarizes their core characteristics based on comparative studies.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Metabarcoding and Metagenomics for Parasite Detection

| Feature | Metabarcoding | Shotgun Metagenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Targeted amplification of a specific DNA barcode region (e.g., 18S V4/V9) [39] [36] | Untargeted sequencing of all DNA in a sample [37] |

| Key Strength | High sensitivity for specific taxa; cost-effective for large sample sets [39] | Freedom from PCR bias; detection of unknown/unexpected parasites; potential for genomic and functional analysis [37] [38] |

| Primary Limitation | PCR amplification bias; primer complementarity issues; limited to targeted taxa [37] [38] [36] | High cost for sufficient sequencing depth; vast majority of sequences unassignable due to limited reference databases [37] [38] |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Species to genus level, dependent on barcode region [39] [36] | Species to strain level, dependent on reference database quality [13] |

| Best Application Context | High-throughput screening for known parasite groups; paleoparasitology with well-preserved aDNA [34] [40] | Discovery of novel parasites; detailed community analysis without primer bias; studies of parasite function and evolution [37] [13] |

The performance differences between these methods have significant practical implications. A comparative study on marine sediment cores spanning 8000 years found limited taxonomic overlap, with only three metazoan genera detected by both methods [37]. Furthermore, metabarcoding detections became inconsistent in samples older than 2000 years, while metagenomics provided more consistent detection throughout the time series, highlighting its potential for ancient DNA (aDNA) studies where DNA is highly fragmented [37]. Conversely, in dietary analysis of pipefishes, metabarcoding failed to detect key copepod species due to amplification bias, a limitation overcome by metagenomics [38].

Optimized Experimental Protocols

Metabarcoding: The VESPA Protocol for Eukaryotic Endosymbionts

The VESPA (Vertebrate Eukaryotic endoSymbiont and Parasite Analysis) protocol represents an optimized metabarcoding workflow designed specifically for host-associated eukaryotes [36]. The key steps are:

- DNA Extraction: Employ a robust extraction method suitable for the sample type (e.g., feces, sediment). For bulk soil nematode communities, elutriation from large soil quantities (up to 500g) is recommended before extraction to increase sensitivity [40].

- PCR Amplification: Use the VESPA primer set targeting the 18S rRNA V4 region. The primers were selected for:

- Broad Taxonomic Coverage: Effective across helminths, protozoa, and microsporidia.

- Minimal Off-Target Amplification: Specifically designed to avoid amplification of host and prokaryotic DNA, which can dominate samples and consume sequencing resources [36].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Follow standard Illumina MiSeq library preparation protocols. The V4 region is optimally suited for the read length constraints of MiSeq v2 chemistry [36].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Process sequences using standard pipelines (e.g., QIIME 2) for denoising, chimera removal, and clustering into Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) [39] [36]. Taxonomic assignment requires a curated reference database.

Metagenomics: A Curated Database Workflow

Shotgun metagenomics for parasites requires careful wet-lab and computational steps to ensure reliable results [34] [13]:

- Library Preparation without Amplification: To avoid PCR bias, library preparation is performed directly on fragmented genomic DNA. This is crucial for capturing the true composition of the community [37].

- High-Depth Sequencing: Sequence to a sufficient depth (often hundreds of millions of reads) to detect low-abundance parasite DNA, which may represent a tiny fraction of the total DNA in a sample [37].

- Reference Database Curation: This is a critical step. The pervasive contamination in public parasite genome databases can lead to false positives. Use a decontaminated database like ParaRef, a curated resource of 831 endoparasite genomes systematically cleaned of contaminant sequences using FCS-GX and Conterminator tools [13]. This significantly reduces false detection rates.

- Taxonomic Profiling: Map sequencing reads against the curated database for species-level identification. For aDNA, tools like

mapDamagecan be used to authenticate ancient sequences by examining cytosine deamination patterns at fragment ends [34].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Successful implementation of these molecular approaches relies on a suite of specific reagents, reference materials, and computational tools.

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit for Parasite Metagenomics and Metabarcoding

| Category | Item | Specific Example / Properties | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primers | 18S rRNA V4 Primers | VESPA primers [36] | Optimized for broad coverage of vertebrate eukaryotic endosymbionts with minimal off-target amplification. |

| 18S rRNA V9 Primers | 1391F / EukBR [39] | An alternative barcode region used for general eukaryotic screening. | |

| Nematode-specific 18S | NF1/18Sr2b [40] | Provides optimal coverage and taxonomic resolution for soil or gut nematode communities. | |

| Reference Databases | Curated Parasite Database | ParaRef [13] | A decontaminated database of 831 endoparasite genomes; crucial for reducing false positives in metagenomics. |

| Custom NCBI Extractions | NCBI nucleotide database (18S rRNA subset) [39] | Used for building custom taxonomic classifiers for metabarcoding. | |

| Standards & Kits | Mock Community Standards | Cloned 18S V4 plasmids from 11 parasite species [39] [36] | Essential for validating and optimizing metabarcoding protocols and assessing PCR bias. |

| DNA Extraction Kit | For soil/sediment (e.g., Fast DNA SPIN Kit for Soil) [34] [39] | Robust lysis for recalcitrant parasite eggs and environmental samples. | |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Sequence Processing | QIIME 2, DADA2, Cutadapt [34] [39] | Demultiplexing, quality filtering, denoising, and chimera removal. |

| Contamination Screening | FCS-GX, Conterminator [13] | Identifies and removes contaminant sequences from reference genomes and sample data. | |

| aDNA Authentication | mapDamage [34] | Evaluates damage patterns to confirm the ancient origin of DNA sequences. |

Implications for Biodiversity and Conservation Research

The application of metabarcoding and metagenomics is reshaping our understanding of parasite biodiversity and its conservation implications.

- Reconstructing Historical Baselines: Paleoparasitology using these methods on archaeological samples (e.g., cesspits, coprolites) provides long-term time series data on parasite communities [34] [37]. This helps establish historical baselines, track species' responses to past environmental changes, and understand the evolution of human-parasite interactions, informing predictions of future dynamics under climate change.

- Soil Health Monitoring: Molecular-based nematode community analysis offers a powerful bioindicator for soil health. Metabarcoding-derived Nematode-based Indices (NBIs) can be applied at large scales to monitor the impacts of agricultural practices and land-use change on ecosystem functioning [40].

- Conservation of Endangered Species: Dietary analysis of endangered species via fecal samples (e.g., the estuarine pipefish) reveals critical ecological requirements and potential interspecific competition, guiding habitat restoration and conservation strategies [38].

- Combating Anthelmintic Resistance: In veterinary and human medicine, these tools enable precise monitoring of parasite populations. They can identify the emergence of multi-species infections and detect genetic markers of anthelmintic resistance, which is critical for managing drug efficacy and preserving treatment options [35].

Metabarcoding and metagenomics are complementary pillars in the modern parasitologist's toolkit. Metabarcoding remains the most cost-effective method for targeted, high-throughput surveillance of known parasite assemblages. In contrast, shotgun metagenomics, empowered by curated databases like ParaRef, offers an unbiased approach for discovery-based research and functional insights, despite its higher cost and computational demands.

The choice between them must be guided by the specific research question, sample type, and available resources. As reference databases continue to improve and sequencing costs decline, the integration of both approaches will undoubtedly provide the most holistic view of parasite diversity. This integrated molecular perspective is essential for advancing our fundamental knowledge of parasite ecology and for informing effective, evidence-based conservation and public health interventions.