Overcoming PCR Inhibition in Stool Samples: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Protozoan Detection

Molecular diagnosis of intestinal protozoa in stool samples is critically limited by PCR inhibitors, which can lead to false-negative results, reduced sensitivity, and unreliable data.

Overcoming PCR Inhibition in Stool Samples: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Protozoan Detection

Abstract

Molecular diagnosis of intestinal protozoa in stool samples is critically limited by PCR inhibitors, which can lead to false-negative results, reduced sensitivity, and unreliable data. This article provides a systematic framework for researchers and scientists to understand, troubleshoot, and overcome these challenges. We explore the foundational causes of inhibition in complex stool matrices and present optimized DNA/RNA extraction protocols validated for parasitic targets. The guide details advanced troubleshooting strategies, including the use of digital PCR and additive enhancers, and offers a comparative analysis of commercial versus in-house molecular tests. Finally, we establish best practices for validation and quality control to ensure accurate, reproducible detection of pathogenic protozoa such as Giardia duodenalis, Entamoeba histolytica, and Cryptosporidium spp., thereby supporting robust drug development and clinical research.

Understanding the Stool Matrix: The Fundamental Challenge of PCR Inhibition

The molecular diagnosis of intestinal protozoa from stool samples presents a formidable challenge due to the complex composition of stool, which contains numerous substances known to inhibit Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) amplification. These inhibitors frequently lead to false-negative results, significantly compromising diagnostic accuracy and epidemiological studies. The efficient extraction of microbial DNA from stool is complicated by the presence of a diverse array of PCR inhibitors, including complex polysaccharides, bile salts, bilirubin, lipids, and various metabolic byproducts. The concentration and composition of these inhibitors are not consistent; they vary considerably between individuals based on clinical status, diet, gut microbiota, and other environmental and lifestyle factors [1]. This article provides a detailed troubleshooting guide to help researchers identify, overcome, and prevent the detrimental effects of PCR inhibition in their protozoa research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

What are the common signs of PCR inhibition in my stool sample assays? The primary indicator of PCR inhibition is the failure to amplify the internal control in a real-time PCR reaction, despite successful amplification of positive controls. A noticeable delay or complete absence of amplification curves for samples that are expected to be positive, based on microscopy or clinical symptoms, is another strong indicator. Furthermore, inconsistent results across replicate samples or a general reduction in assay sensitivity can also point towards the presence of inhibitors [2] [1].

Which DNA extraction methods are most effective against PCR inhibitors in stool? Research consistently demonstrates that the choice of DNA extraction method is the most critical factor in overcoming PCR inhibition. Studies comparing various techniques have found that commercial kits specifically designed for fecal samples, particularly those incorporating mechanical lysis like bead-beating, yield the best results.

Table: Comparison of DNA Extraction Method Efficiencies for Stool Samples

| Extraction Method | Key Features | Reported PCR Detection Rate | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenol-Chloroform (P) | Chemical lysis, organic extraction | 8.2% | Lowest detection rate; ineffective for most parasites except Strongyloides [1] |

| Phenol-Chloroform + Bead-Beating (PB) | Adds mechanical disruption | Higher yield than P alone | Improved DNA quantity but not fully effective against inhibitors [1] |

| QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Q) | Silica-column based | Not specified | Better than phenol-chloroform, but inferior to more advanced kits [1] |

| QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QB) | Bead-beating + inhibitor removal chemistry | 61.2% | Highest detection rate; effective for a wide range of protozoa and helminths [1] |

Why is mechanical lysis so important for extracting DNA from intestinal protozoa? Intestinal protozoa form robust protective walls around their cysts and oocysts to survive harsh environmental conditions. Similarly, helminth eggs have strong shells that are difficult to break. Mechanical lysis methods, such as bead-beating with glass beads, are essential to physically disrupt these resilient structures and release DNA for subsequent amplification. Without this step, DNA remains trapped inside, leading to false-negative PCR results [1].

How can I confirm that a negative PCR result is due to inhibition and not a true negative? The most reliable method to test for the presence of residual PCR inhibitors is to perform a "spike" test. This involves adding a known quantity of a control DNA (e.g., a plasmid containing a non-target gene) into the extracted DNA sample and then running a PCR specific to that control. If the control fails to amplify, it confirms that inhibitors are still present in the sample. One study noted that after spiking, 60 samples that were negative using the phenol-chloroform method remained negative, confirming persistent inhibition, whereas only 5 samples were negative when using the optimized QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QB) [1].

Beyond extraction, what other steps can reduce inhibition? Two key strategies can be employed post-extraction. First, diluting the DNA template can reduce the concentration of co-eluted inhibitors to a level that no longer affects the PCR reaction. It is crucial to balance this, as excessive dilution may also reduce the target DNA concentration below the detection limit. Second, the use of PCR master mixes that are specially formulated to be resistant to common inhibitors found in complex samples like stool can significantly improve amplification reliability [2].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimized DNA Extraction using Bead-Beating

This protocol is adapted from methods validated in recent comparative studies [1].

- Sample Preparation: Aliquot 200 mg of stool into a 2 mL sterile microcentrifuge tube. If the sample is preserved in ethanol, wash it three times with sterile distilled water before proceeding.

- Lysis and Bead-Beating: Add stool lysis buffer and a mixture of glass beads to the sample. Secure the tubes and process them in a bead-beater homogenizer for the recommended time (e.g., 2-3 minutes at high speed).

- Incubation: Incubate the homogenate at elevated temperatures (e.g., 65°C for 10-30 minutes) to further facilitate lysis.

- DNA Purification: Transfer the supernatant to a new tube and continue with the DNA binding and washing steps as per the manufacturer's instructions for a kit like the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit.

- Elution: Elute the purified DNA in a low-EDTA TE buffer or nuclease-free water. Store the DNA at -20°C.

Protocol 2: Validated Workflow for Multiplex PCR Detection

This workflow is based on multicentric evaluations of the AllPlex GI-Parasite Assay [3] [2] [4].

- Automated Nucleic Acid Extraction: Use an automated system, such as the Microlab Nimbus IVD or MagNA Pure 96, with reagents designed for stool samples. This ensures reproducibility and minimizes cross-contamination.

- PCR Setup: Prepare the multiplex real-time PCR reaction according to the kit's instructions. The AllPlex GI-Parasite Assay, for example, targets Giardia duodenalis, Cryptosporidium spp., Entamoeba histolytica, Dientamoeba fragilis, Blastocystis spp., and Cyclospora spp.

- Amplification: Run the PCR on a real-time cycler (e.g., CFX96 from Bio-Rad) using the recommended cycling conditions. Fluorescence is typically measured at two different temperatures (e.g., 60°C and 72°C).

- Result Interpretation: Analyze the amplification curves using the provided software (e.g., Seegene Viewer). A sample is considered positive if a sharp exponential fluorescence curve crosses the threshold (Ct) before cycle 45 for the specific target, with the internal control also amplifying correctly.

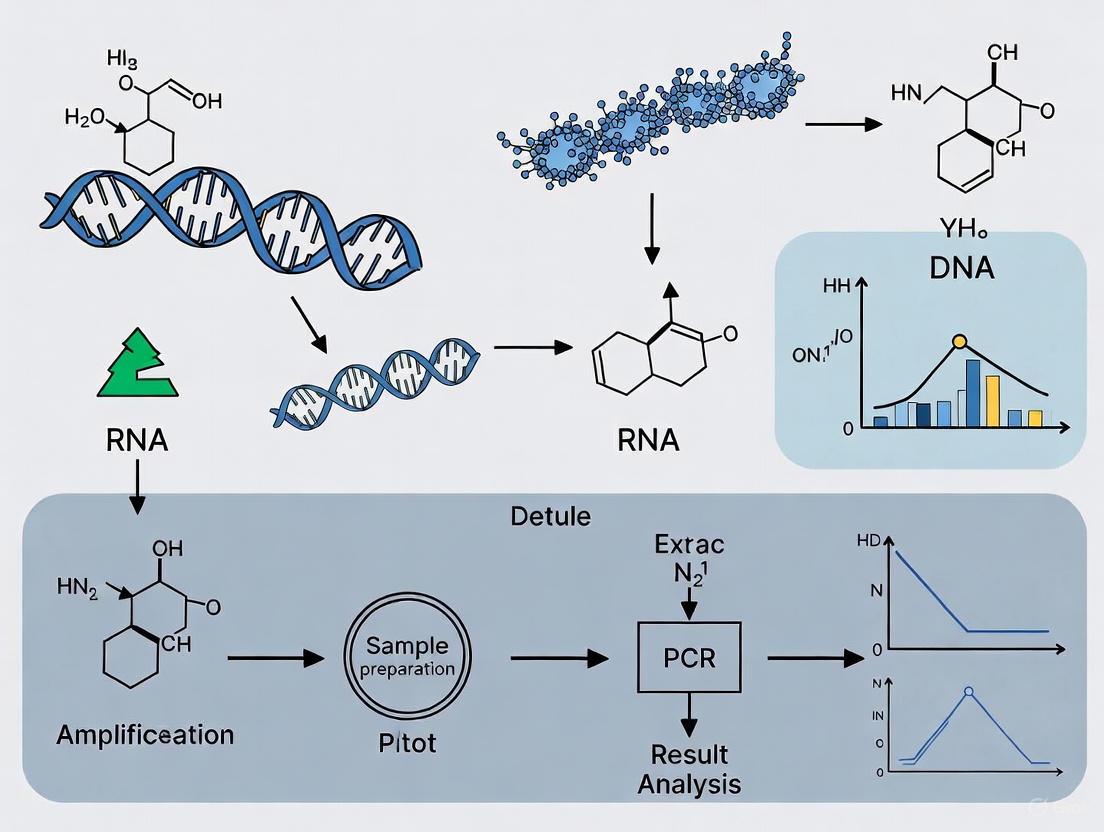

The following diagram illustrates the critical decision points in a standard stool PCR workflow and the recommended steps to mitigate inhibition.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Reagents and Kits for Overcoming PCR Inhibition in Stool

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor-Resistant DNA Polymerases | PCR enzymes designed to remain active in the presence of common stool inhibitors. | Included in commercial master mixes from various manufacturers. |

| Mechanical Lysis Tubes | Contains beads to physically break open sturdy parasite (oo)cysts and eggshells during homogenization. | Glass beads in 2 mL tubes for bead-beaters [1]. |

| Automated Nucleic Acid Extractors | Standardizes the extraction process, improving reproducibility and throughput while reducing contamination. | Microlab Nimbus IVD system, MagNA Pure 96 System [2] [5]. |

| Internal Control DNA | A non-target DNA sequence added to the sample to monitor for PCR inhibition throughout the process. | Included in commercial PCR kits like the AllPlex GI-Parasite Assay [3] [2]. |

| Stool DNA Extraction Kits | Commercial kits optimized for fecal samples, combining lysis and purification steps to remove inhibitors. | QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit, QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit [1]. |

| Stool Transport & Lysis Buffers | Preserves nucleic acids and begins the breakdown of stool components and parasite walls upon collection. | FecalSwab medium, S.T.A.R. Buffer, ASL Lysis Buffer [3] [2] [5]. |

The following workflow summarizes the optimized, multi-stage strategy to effectively manage PCR inhibitors from sample collection to final result interpretation.

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a powerful tool for diagnosing intestinal protozoan infections in clinical and research settings. However, the complex composition of human stool presents a significant challenge for molecular diagnostics. Stool samples contain a heterogeneous mix of PCR inhibitors that can severely reduce the sensitivity of detection or cause complete amplification failure. These inhibitors interfere with the enzymatic polymerization process, ultimately leading to false-negative results and an underestimation of pathogen presence. Understanding the specific mechanisms by which these components impede polymerase activity is fundamental to developing effective countermeasures, particularly for research focused on protozoa such as Giardia intestinalis, Cryptosporidium spp., and Entamoeba histolytica [6].

The impact of these inhibitors is not trivial; one study on the detection of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP) found that 19.94% of fecal DNA extracts showed evidence of inhibition. When this inhibition was relieved, the average DNA quantification increased by 3.3-fold, and the test sensitivity of the qPCR rose dramatically from 55% to 80% compared to fecal culture [7]. This highlights the critical importance of addressing inhibition for accurate diagnosis and research outcomes.

Mechanisms of PCR Inhibition

PCR inhibitors present in stool samples disrupt the amplification process through several distinct biochemical mechanisms. The following diagram illustrates the primary points of interference in the PCR workflow.

The mechanisms can be broadly categorized as follows:

- Direct Inhibition of DNA Polymerase: Many stool components can directly affect the activity of the DNA polymerase enzyme. Proteases can degrade the enzyme, while other compounds like polysaccharides may mimic the structure of nucleic acids and compete for binding sites. Substances such as humic acids, hemoglobin, and bile salts can bind to the polymerase, altering its conformation and reducing its enzymatic efficiency [8] [9].

- Chelation of Essential Cofactors: Magnesium ions (Mg²⁺) are an essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity. Inhibitors such as complexing agents (e.g., from plant materials) and calcium ions can bind to magnesium, making it unavailable for the enzymatic reaction. This depletion of free magnesium directly impairs polymerase function [8].

- Interaction with Nucleic Acids: The template DNA itself can be a target for inhibition. Humic substances can bind directly to nucleic acids, making the template unavailable for amplification. Under oxidizing conditions, phenolic compounds can cross-link DNA, while nucleases may degrade the template DNA or RNA [8] [9].

- Interference with Fluorescence Detection: For real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR), an additional mechanism of inhibition exists. Some compounds can quench fluorescence, interfering with the detection of the accumulating amplicon. This can happen through collisional quenching, where the quencher collides with the excited fluorophore, or static quenching, where a non-fluorescent complex is formed [9].

Key Inhibitors and Their Properties

The following table summarizes the major classes of PCR inhibitors found in stool samples, their specific components, and their primary modes of action.

Table 1: Common PCR Inhibitors in Stool Samples and Their Mechanisms

| Inhibitor Class | Specific Components | Primary Mechanism of Action | Sample/Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bile Salts | Bilirubin, Bile Acids | Disruption of cell membranes and potential denaturation of enzymes [7]. | Fecal samples [7]. |

| Complex Polysaccharides | Undigested food matter, Plant fibers | They can mimic the structure of DNA, interfering with primer annealing and polymerase binding [8]. | Stool, food, and plant samples [8]. |

| Heme and Related Compounds | Hemoglobin, Hematin | Interferes with the polymerase activity and can be a potent inhibitor [9]. | Fecal samples, blood [9]. |

| Humic Substances | Humic Acid, Fulvic Acid | Binds to the DNA polymerase and to the nucleic acids, preventing the enzymatic reaction [8] [9]. | Soil, environmental water, and stool [9]. |

| Proteins | Immunoglobulin G (IgG), Digestive Enzymes | IgG has a high affinity for single-stranded DNA, making it unavailable for amplification. Proteases can degrade the DNA polymerase [8]. | Blood, serum, plasma, and stool [8]. |

| Calcium Ions | Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) | Competes with magnesium ions (Mg²⁺) for binding to the DNA polymerase, which relies on Mg²⁺ as a cofactor [8]. | Various biological samples [8]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

A variety of reagents and kits are available to help researchers overcome PCR inhibition. The selection of an appropriate DNA polymerase, additives, and extraction methodology is crucial for success.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Mitigating PCR Inhibition

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Description | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Amplification Facilitators | ||

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Binds to inhibitors like phenolics, humic acids, and tannic acids, neutralizing their effect [8]. | Protein-based facilitator. |

| T4 Gene 32 Protein (gp32) | A single-stranded DNA-binding protein that can protect DNA and neutralize proteinases [8]. | Protein-based facilitator. |

| Betaine | Reduces the formation of secondary structures in DNA, improving amplification efficiency [8]. | Biologically compatible solute. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Influences the thermal stability of primers and DNA, increasing amplification specificity [8]. | Organic solvent. |

| Commercial DNA Extraction Kits | ||

| QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit | Utilizes mechanical lysis (bead-beating) and silica-based technology to purify DNA while removing inhibitors. | In a comparative study, this kit showed the highest PCR detection rate (61.2%) for various intestinal parasites [1]. |

| Phenol-Chloroform Method | A traditional method using organic solvents to separate DNA from proteins and other contaminants. | Can provide high DNA yields but is labor-intensive and showed a low PCR detection rate (8.2%) in one study [1]. |

| Inhibitor-Tolerant DNA Polymerases | ||

| Phusion Flash | A engineered DNA polymerase blend designed for high resistance to PCR inhibitors present in blood and stool. | Enables direct PCR approaches with minimal sample purification [9]. |

| rTth & Tfl Polymerase | DNA polymerases isolated from Thermus thermophilus and Thermus flavus, respectively. | Exhibit greater resistance to inhibitors in blood compared to standard Taq polymerase [8]. |

Experimental Protocols for Overcoming Inhibition

Evaluating and Relieving Inhibition via Dilution

A proven method to relieve PCR inhibition is the dilution of the DNA extract, which simultaneously dilutes the inhibitors to a non-critical concentration.

Protocol:

- Extract DNA from the stool sample using your method of choice (e.g., QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit) [1].

- Prepare a five-fold dilution of the extracted DNA in a low-EDTA TE buffer or the elution buffer used in your extraction kit (e.g., AVE buffer) [7].

- Run parallel qPCR assays with both the undiluted and the five-fold diluted DNA.

- Compare the quantification cycle (Cq) values. A significantly lower Cq (indicating higher DNA quantity) in the diluted sample is indicative of successful relief of inhibition. One study reported an average 3.3-fold increase in DNA quantification after a five-fold dilution [7].

Considerations: While simple and effective, this method also dilutes the target DNA, which could reduce sensitivity for samples with very low pathogen load. It is therefore most effective for moderate to high-template samples.

Assessing Inhibition with Internal Controls and Spike Tests

To distinguish between a true negative result and a false negative caused by inhibition, the use of internal controls is essential.

Protocol (Internal Amplification Control - IAC):

- Utilize a qPCR assay that includes a non-competitive IAC. This is a synthetic DNA sequence with its own primer and probe set that is amplified simultaneously with, but does not interfere with, the target sequence.

- Spike the IAC into the master mix at a known, low concentration.

- Interpret the results:

- If both the target and IAC amplify, the sample is negative and inhibition is absent.

- If the target amplifies but the IAC does not, the sample is positive.

- If the target does not amplify and the IAC also fails to amplify or shows a significantly delayed Cq, inhibition is present [7].

Protocol (Plasmid Spike Test): For samples that are negative by PCR, a spike test can retrospectively confirm the absence of inhibitors.

- Add a known quantity of a plasmid containing a specific target gene to the negative extracted DNA sample.

- Perform a PCR targeting the plasmid gene.

- Interpret the results: Successful amplification of the plasmid gene indicates the absence of significant inhibitors, suggesting the original negative result was true. Failure to amplify the plasmid indicates the presence of PCR inhibitors [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: My PCR results are consistently negative, even when I know the target should be present. How can I determine if inhibition is the problem?

- Run an Internal Control: The most direct method is to use an Internal Amplification Control (IAC) in your qPCR assay. Failure of the IAC to amplify is a strong indicator of inhibition [7].

- Perform a Dilution Test: Dilute your DNA template 1:5 and 1:10 and re-run the PCR. A positive result from a diluted sample, but not from the neat sample, is classic evidence of PCR inhibition [7].

- Spike with a Positive Control: Add a known amount of a control DNA (e.g., a plasmid) to your negative sample. If this control also fails to amplify, your sample contains inhibitors [1].

FAQ 2: I am working with frozen stool samples. Are there any special considerations for DNA extraction? Yes, freezing and thawing can disrupt the oocyst walls of protozoa like Cryptosporidium, releasing sporozoites and DNA into the fecal matrix. This makes purification methods that rely on intact oocysts (e.g., immunomagnetic separation) less effective. For frozen samples, methods that directly extract DNA from the whole stool are more appropriate, such as the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit which includes a bead-beating step for efficient lysis [1] [10].

FAQ 3: Which DNA extraction method is most effective for a broad range of intestinal parasites in stool? A comparative study found that the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QB) was the most effective method for extracting DNA from a wide range of parasites, including fragile protozoa like Blastocystis sp. and hardy helminths like Ascaris lumbricoides. This kit achieved a PCR detection rate of 61.2%, significantly higher than the phenol-chloroform method (8.2%) and other commercial kits tested. The incorporation of mechanical lysis (bead-beating) is a key factor in its success [1].

FAQ 4: Besides optimizing DNA extraction, what else can I add to my PCR reaction to reduce inhibition? Consider adding amplification facilitators to your master mix:

- Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA): Effective at neutralizing a wide range of inhibitors, including humic acids, phenolics, and tannic acids [8].

- Single-Stranded DNA-Binding Proteins (e.g., gp32): Can protect the DNA polymerase from proteases and stabilize single-stranded DNA templates [8].

- Use an Inhibitor-Tolerant Polymerase: Selecting a DNA polymerase engineered for resistance to inhibitors (e.g., Phusion Flash, rTth) is often more effective than trying to remove all inhibitors from the sample [8] [9].

FAQ 5: How does digital PCR (dPCR) compare to qPCR in dealing with inhibitors? Digital PCR (dPCR) has been demonstrated to be more tolerant of PCR inhibitors than qPCR. Because dPCR is an end-point measurement that does not rely on amplification kinetics (Cq values), it is less affected by inhibitors that merely slow down the reaction rather than stop it completely. Partitioning the sample into thousands of individual reactions also reduces the local concentration of inhibitors in positive partitions, which can prevent complete amplification failure [9].

Accurate molecular detection of intestinal protozoa in stool samples is critically dependent on pre-analytical procedures. Errors introduced during specimen collection, transport, or storage can lead to false-negative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results, primarily due to the presence of inhibitors or degradation of nucleic acids. This guide addresses key variables to reduce inhibition in stool PCR for protozoa research, providing troubleshooting and frequently asked questions for researchers and scientists in drug development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common causes of PCR inhibition when working with stool specimens?

PCR inhibitors in stool samples are heterogeneous and can originate from the sample itself or be introduced during processing. Common inhibitors include:

- Sample-derived inhibitors: Bilirubin, bile salts, complex carbohydrates, hemoglobin, and immunoglobulins from the host; humic substances from gut microbiota [8].

- Process-derived inhibitors: Ionic detergents (SDS, sarkosyl), alcohols (ethanol, isopropanol), phenol, and EDTA from extraction procedures [8]. These substances can inhibit PCR by degrading or denaturing DNA polymerases, binding to nucleic acids, or depleting essential co-factors like magnesium ions [8].

Q2: Which specimen preservatives are compatible with molecular detection of protozoa?

The choice of preservative is crucial for successful molecular diagnosis. The CDC recommends preservatives that maintain DNA integrity for PCR [11].

Table: Compatibility of Stool Preservatives with Molecular Detection

| Recommended Preservatives | Non-Recommended Preservatives |

|---|---|

| TotalFix [11] | Formalin [11] |

| Unifix [11] | SAF (Sodium Acetate-Acetic Acid-Formalin) [11] |

| Modified PVA (Zinc- or Copper-based) [11] | LV-PVA [11] |

| EcoFix [11] | Protofix [11] |

| Potassium Dichromate (2.5%) [11] | |

| Absolute Ethanol [11] |

Q3: What is the best DNA extraction method to minimize PCR inhibition for diverse intestinal parasites?

A 2022 comparative study evaluated four DNA extraction methods for various parasites, including fragile protozoa like Blastocystis sp. and helminths with robust eggshells like Ascaris lumbricoides [12]. The methods were assessed based on DNA yield, quality, and most importantly, PCR detection rates.

Table: Comparison of DNA Extraction Methods for Intestinal Parasite PCR

| Extraction Method | Description | Average PCR Detection Rate | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenol-Chloroform (P) | Conventional organic solvent extraction [12] | 8.2% | Lowest detection rate; only detected S. stercoralis [12] |

| Phenol-Chloroform with Bead-Beating (PB) | P method with mechanical lysis using glass beads [12] | Information Missing | Provided higher DNA yield than kit methods [12] |

| QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Q) | Commercial silica-column based kit [12] | Information Missing | |

| QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QB) | Commercial kit designed for inhibitor-rich samples [12] | 61.2% | Most effective; detected all parasite groups tested and showed least inhibition in spike tests [12] |

The study concluded that the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QB) was the most effective method for the PCR-based diagnosis and monitoring of a wide range of intestinal parasites due to its high detection rate and superior handling of PCR inhibitors [12].

Q4: How should unpreserved stool specimens be handled for PCR analysis?

If a preservative is not used, stool must be collected in a clean container and immediately refrigerated [13] [11]. For transport, the specimen must be kept cold with cold packs and shipped via an overnight courier to ensure it arrives on a weekday and does not sit over a weekend [13]. Unpreserved specimens can also be frozen and shipped on dry ice [11].

Troubleshooting Common PCR Inhibition Issues

Table: Troubleshooting Guide for Inhibited Stool PCR

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions & Preventive Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Complete PCR amplification failure despite good DNA yield | High concentration of potent inhibitors (e.g., humic acids, IgG, bile salts) [8] | 1. Dilute the DNA template to reduce inhibitor concentration [8].2. Re-purify DNA using a kit designed for inhibitor removal [12] [8].3. Add amplification facilitators like BSA (0.1-0.5 μg/μL) or T4 gp32 protein to the PCR mix [8]. |

| High Ct values or reduced sensitivity | Low to moderate level of inhibitors; suboptimal DNA polymerase activity [8] | 1. Use a DNA polymerase known for high inhibitor tolerance (e.g., rTth or Tfl polymerase) [8].2. Include facilitators like betaine (1-1.5 M) or DMSO (1-5%) in the reaction mix [8].3. Ensure complete removal of ethanol during DNA extraction washing steps [8]. |

| Inconsistent results across samples from the same batch | Variable inhibitor load due to differences in stool composition [12] | 1. Standardize the input stool amount (e.g., 180-200 mg) [12].2. Implement a rigorous homogenization step, such as bead-beating, to ensure uniform lysis [12].3. Use an internal control (e.g., a spiked plasmid) to identify samples with inhibition [12]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Cited Studies

This protocol is adapted from the 2022 study that identified the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit as the most effective method.

1. Sample Preparation:

- Preserve approximately 2 g of stool in 5 mL of 70% ethanol.

- Before extraction, wash the preserved stool three times with sterile distilled water.

- Aliquot 200 mg (or 0.2 mL) of stool into a 2 mL microcentrifuge tube for extraction.

2. DNA Extraction using the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QB):

- Follow the manufacturer's instructions with the following critical steps:

- Add the recommended lysis buffer and vortex thoroughly.

- Perform bead-beating: Use a vortex adapter or homogenizer with the provided beads for a minimum of 10 minutes to ensure mechanical disruption of hardy parasite eggs and cysts.

- Incubate the lysate at elevated temperatures (e.g., 95°C for 5-10 minutes) to further facilitate lysis and inactivate nucleases.

- Centrifuge to pellet stool debris and inhibitors.

- Bind DNA to the spin column, wash with provided buffers, and elute in a low-volume elution buffer.

3. Quality Assessment:

- Quantify DNA using spectrophotometry (e.g., Nanodrop).

- Assess DNA integrity and success of extraction by running a PCR for a ubiquitous host gene (e.g., β-actin) or a spiked internal control to check for inhibition.

This protocol is based on the 2025 study that implemented a low-volume qPCR assay.

1. Primer and Probe Design:

- For novel targets (e.g., C. mesnili), retrieve sequence data from NCBI and identify highly conserved regions using BLASTN.

- Design primers and probes to meet the following criteria:

- GC content: ~50%

- Length: 20-24 bases

- Estimated Tm: ~58°C

- Validate specificity in silico with BLASTN against the NCBI database.

2. qPCR Reaction Setup:

- Use a 10 μL total reaction volume [14].

- Mastermix components typically include:

- 1X PCR buffer

- Primers (0.3-0.5 μM each, see table below)

- Probe (sequence-specific, e.g., TaqMan)

- DNA Polymerase (e.g., Hot Start Taq)

- dNTPs

- MgCl₂

- Add 2-5 μL of template DNA.

Table: Example Primer and Probe Concentrations from Implemented Assays [14]

| Organism | Forward Primer (c) | Reverse Primer (c) | Probe |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blastocystis spp. | 0.3 μM | 0.3 μM | Information Missing |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | 0.5 μM | 0.5 μM | Information Missing |

| E. dispar / E. histolytica | 0.5 μM | 0.5 μM | Information Missing |

| G. duodenalis | 0.5 μM | 0.5 μM | Information Missing |

3. qPCR Cycling Conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 3-5 minutes.

- 45 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 10-15 seconds.

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 30-60 seconds (with fluorescence readout).

- Analyze results using a cycle threshold (Ct) of ≤43 as a potential positive cutoff, as used in validated automated platforms [15].

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Reducing Inhibition in Stool PCR

| Reagent / Kit | Specific Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit | DNA extraction optimized for difficult samples; includes beads for mechanical lysis and reagents to remove PCR inhibitors [12]. | Most effective for broad-range parasite detection; superior to conventional phenol-chloroform and other kit methods [12]. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Amplification facilitator; binds to inhibitors like phenolics and humic acids, preventing them from interfering with the polymerase [8]. | Use at 0.1-0.5 μg/μL in the PCR mix to mitigate inhibition from complex samples. |

| Betaine | Amplification facilitator; reduces secondary structure formation in DNA, equalizes Tm of primers, and enhances polymerase stability [8]. | Use at 1-1.5 M concentration in the PCR reaction to improve specificity and yield. |

| Inhibitor-Tolerant DNA Polymerase | Engineered polymerases (e.g., rTth, Tfl) with higher resistance to common inhibitors found in blood, stool, and soil [8]. | Select over standard Taq when working with unpreserved or inhibitor-rich stool samples. |

| Seegene Allplex GI-Parasite Assay | Automated multiplex real-time PCR panel for detection of 6 protozoal pathogens (B. hominis, Cryptosporidium, C. cayetanensis, D. fragilis, E. histolytica, G. lamblia) [15]. | Validated for use with automated extraction platforms; reduces hands-on time and cross-contamination risk. |

| Hamilton STARlet + StarMag Kit | Automated liquid handling system and magnetic bead-based nucleic acid extraction platform [15]. | Integrated system for high-throughput, reproducible DNA extraction from stool samples in clinical or large-scale studies. |

Understanding Diagnostic Accuracy and the Nature of False Negatives

In diagnostic testing, a false negative occurs when a test incorrectly indicates the absence of a condition or pathogen when it is truly present. This stands in contrast to a false positive, where the test incorrectly indicates the presence of a condition. Understanding the metrics of diagnostic test accuracy is crucial for interpreting these results [16].

Sensitivity and specificity are fundamental indicators of test accuracy. Sensitivity measures a test's ability to correctly identify patients with a disease, while specificity measures its ability to correctly identify patients without the disease [16]. The formulas for these metrics are:

- Sensitivity = True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives)

- Specificity = True Negatives / (True Negatives + False Positives)

These metrics are often inversely related, requiring careful balancing in test development [16]. For stool PCR diagnostics, this balance is particularly critical as false negatives can lead to untreated infections, ongoing transmission, and distorted clinical decisions [17].

The pretest probability significantly influences how negative results should be interpreted. In high-prevalence settings or patients with strong clinical symptoms, a single negative result from a test with limited sensitivity may not be sufficient to rule out infection [17]. Understanding this context helps researchers and clinicians appreciate why false negatives represent a "hidden risk" that creates a false sense of security, potentially delaying appropriate interventions [17].

Clinical and Research Consequences in Stool Protozoa PCR

Direct Impacts on Patient Care and Public Health

False negative results in stool protozoa PCR can lead to several significant clinical consequences:

- Delayed or Withheld Treatment: Patients with undetected infections do not receive appropriate therapy, leading to prolonged illness and potential complications. For example, undiagnosed Entamoeba histolytica can progress to invasive amoebiasis, including liver abscesses [3] [5].

- Continued Disease Transmission: Individuals with false negative results may remain in community settings, unknowingly transmitting pathogens through fecal-oral routes. This is particularly concerning in outbreak situations or areas with poor sanitation [14].

- Misallocation of Resources: Clinical investigations may shift toward other potential causes of symptoms, leading to unnecessary tests, treatments, and extended diagnostic journeys.

Impacts on Research and Drug Development

In research contexts, false negatives introduce specific challenges:

- Underestimation of Protozoa Prevalence: Studies measuring infection rates may report artificially low prevalence if diagnostic methods have unaccounted-for false negatives [14] [5].

- Compromised Efficacy Assessments: Clinical trials evaluating new anti-protozoal therapies may underestimate true efficacy if pre-treatment infections are missed, potentially leading to erroneous conclusions about drug effectiveness [14].

- Distorted Epidemiological Understanding: Inaccurate detection hampers understanding of true disease burden and distribution, affecting public health planning and resource allocation.

Table 1: Comparison of Detection Methods for Intestinal Protozoa

| Method | Reported Sensitivity | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Microscopy | Varies by pathogen and operator [3] | Low cost, detects multiple parasites simultaneously [5] | Limited sensitivity, subjective, requires high expertise [14] [3] |

| Real-time PCR | Generally high (>90% for major protozoa) [18] | Species-level differentiation, objective interpretation [14] | Requires specific equipment, potential inhibition issues [5] |

| Commercial Multiplex PCR | High for most targets (e.g., 94.3% in validation studies) [19] | Multiplexing capability, standardized protocols [3] | May miss uncommon pathogens not included in panel [3] |

| Artificial Intelligence (AI) | 98.6% after discrepant resolution [19] | Automated, consistent, detects more organisms than humans [19] | Emerging technology, requires validation across diverse populations [19] |

Technical Guide: Troubleshooting False Negatives in Stool PCR

Comprehensive Troubleshooting Framework

When facing suspected false negatives in stool PCR for protozoa detection, systematically address these potential issues:

Sample Quality and Collection Issues

- Problem: Suboptimal sample collection, storage, or transportation

- Solutions:

PCR Inhibition

- Problem: Stool components (e.g., complex polysaccharides, bile salts, heme) inhibit polymerase activity

- Solutions:

- Include internal controls in extraction and amplification steps to detect inhibition [5] [18]

- Dilute template DNA to reduce inhibitor concentration

- Use inhibitor-resistant polymerases or additives like bovine serum albumin (BSA) [18]

- Implement additional purification steps (e.g., alcohol precipitation, spin column cleanup) [20]

Primer and Probe Issues

- Problem: Suboptimal primer/probe design or degradation

- Solutions:

Reaction Component Problems

- Problem: Variations in master mix performance between batches or manufacturers

- Solutions:

Instrument and Protocol Issues

- Problem: Suboptimal cycling conditions or instrument calibration

- Solutions:

Advanced Technical Solutions

DNA Extraction Optimization

- Implement mechanical disruption (bead beating) alongside chemical lysis for robust protozoan cyst walls [5]

- Include pre-treatment steps such as freezing followed by boiling (10 minutes at 100°C) to improve DNA release [18]

- Use polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (PVPP) in storage buffers to adsorb PCR inhibitors [18]

Multiplex Assay Validation

- When developing duplex or multiplex assays (e.g., Entamoeba dispar + E. histolytica), ensure all targets amplify with similar efficiency [14]

- Verify primer compatibility and check for primer-dimer formation

- Validate reduced reaction volumes (e.g., 10 µL) to enhance cost-effectiveness without sacrificing sensitivity [14]

Experimental Protocols for Sensitivity Optimization

Protocol for Assessing PCR Inhibition

Purpose: To identify and quantify inhibition in stool DNA extracts Materials:

- Test DNA samples

- Internal control DNA (e.g., Phocine Herpes Virus type-1 [PhHV-1]) [18]

- PCR master mix with appropriate primers/probes for control target

Procedure:

- Prepare duplicate reactions: one with sample DNA only, one with sample DNA spiked with known quantity of control DNA

- Run real-time PCR with conditions optimized for control target

- Compare Cq values between spiked and unspiked reactions

- A significant delay (e.g., ΔCq > 2) in the spiked reaction indicates inhibition

Interpretation: If inhibition is detected, implement additional purification steps or template dilution

Protocol for Limit of Detection (LOD) Determination

Purpose: To establish the lowest concentration of target detectable by the assay Materials:

- Reference material with known quantity of target protozoa

- Serial dilution materials

- PCR reagents and equipment

Procedure:

- Prepare serial dilutions of reference material in negative stool matrix

- Extract DNA from each dilution using standard protocol

- Amplify each dilution in replicate (minimum 8 replicates per dilution)

- Determine the lowest concentration where ≥95% of replicates test positive

Documentation: Record LOD as concentration (cysts/oocysts per gram) or genome copies per reaction

Research Reagent Solutions for Enhanced Sensitivity

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Optimizing Stool PCR Sensitivity

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition-Resistant Polymerases | Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase, OneTaq Hot Start DNA Polymerase [20] | DNA amplification with reduced inhibitor sensitivity | Particularly useful for GC-rich templates or complex stool backgrounds [20] |

| Inhibitor Binding Agents | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (PVPP) [18] | Bind PCR inhibitors present in stool | Add to extraction or reaction buffers; BSA concentration typically 2.5 µg/reaction [18] |

| DNA Extraction Enhancers | S.T.A.R. Buffer, PreCR Repair Mix [20] [5] | Improve DNA recovery and integrity | PreCR Mix repairs damaged DNA; S.T.A.R. Buffer maintains DNA stability [20] [5] |

| Internal Controls | Phocine Herpes Virus (PhHV-1), manufacturer-supplied internal controls [18] | Monitor extraction efficiency and PCR inhibition | Include in extraction process; should amplify with consistent Cq in absence of inhibition [18] |

| Nucleic Acid Preservation Media | Para-Pak, FecalSwab medium, formalin-ethyl acetate [3] [5] | Stabilize nucleic acids between collection and processing | Preserved samples may yield better DNA than fresh samples in some cases [5] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why might our stool PCR assays suddenly start producing false negatives when we haven't changed our protocol? A: Sudden appearance of false negatives may indicate:

- New batch of critical reagents (especially master mix) with different performance characteristics [22]

- Deterioration of primer/probe stocks due to repeated freeze-thaw cycles [21]

- Introduction of new sample collection materials containing inhibitors

- Changes in local water quality affecting reaction components

- Instrument calibration drift affecting temperature uniformity [20]

Q2: How can we validate that our negative PCR results are true negatives rather than false negatives? A: Implement a comprehensive validation approach:

- Include internal controls in every reaction to detect inhibition [18]

- Periodically test known positive samples as controls

- For research studies, consider parallel testing with alternative methods (e.g., microscopy, antigen testing) [5]

- Use digital PCR for absolute quantification when extreme sensitivity is required

- In clinical contexts, correlate with patient symptoms and epidemiological data

Q3: What is the most effective approach to reduce inhibition in stool DNA extracts? A: A multi-pronged strategy works best:

- Incorporate inhibitor-binding agents like BSA or PVPP during extraction [18]

- Dilute template DNA (1:5 or 1:10) to reduce inhibitor concentration while maintaining detectable target

- Use inhibitor-resistant polymerases specifically designed for complex matrices [20]

- Implement additional purification steps such as silica-based column cleanups [20]

- For persistent issues, consider pre-treatment methods like bead beating or freeze-thaw cycles [18]

Q4: How does sample preservation method affect PCR sensitivity for intestinal protozoa? A: Preservation method significantly impacts sensitivity:

- Fresh samples may provide better sensitivity for certain pathogens but are more susceptible to degradation [5]

- Preserved samples (e.g., in formalin-based media) offer better DNA stability but may require modified extraction protocols [5]

- Specific preservation media can influence inhibitor levels and DNA recovery efficiency

- The optimal method may vary by target protozoan, requiring validation for each organism of interest

Workflow Diagram: Systematic Approach to Addressing False Negatives

Systematic Troubleshooting Pathway for False Negatives

Minimizing false negatives in stool protozoa PCR requires a comprehensive approach addressing pre-analytical, analytical, and post-analytical factors. Researchers must recognize that a negative result should not be interpreted as a definitive "does not have it," but rather as a reduction in probability that must be weighed against clinical and epidemiological context [17].

The most effective strategy combines:

- Rigorous validation of methods with known positive samples

- Systematic monitoring of assay performance through internal controls

- Careful attention to sample quality and storage conditions

- Proactive troubleshooting when deviations from expected performance occur

By implementing these practices, researchers and clinicians can significantly reduce the risk of false negatives, leading to more accurate diagnosis, better patient outcomes, and more reliable research data in the study of intestinal protozoan infections.

Optimized Workflows: From Sample Collection to Amplification

The accurate molecular diagnosis of intestinal protozoa, a critical tool for researchers and public health professionals, is highly dependent on the quality of the starting specimen. The choice of fixative and subsequent DNA extraction protocol directly impacts the yield and purity of nucleic acids, which can determine the success or failure of downstream polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays. Inhibition of PCR by substances co-extracted from stool samples remains a significant challenge. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting advice and technical protocols to help researchers select appropriate fixatives and optimize methods to reduce inhibition in stool PCR for protozoa research.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the main advantage of using a non-crosslinking fixative like RCL2 over formalin for molecular studies?

Formalin, the traditional pathological fixative, creates cross-links between proteins and nucleic acids that can fragment DNA and RNA, impairing subsequent molecular analyses [23]. In contrast, the non-crosslinking fixative RCL2-CS100 provides excellent preservation of both cellular architecture for histological diagnosis and high-quality nucleic acids. Studies show that DNA isolated from RCL2-fixed tissues is of sufficient quality for demanding molecular techniques including the amplification of large DNA fragments, comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) arrays, and genotyping [23].

Q2: Why is microscopy still sometimes necessary when using multiplex PCR panels for protozoan diagnosis?

While multiplex real-time PCR (qPCR) assays are highly sensitive and specific for detecting major protozoan parasites, they have defined target lists. Microscopy remains a crucial complementary technique for two main reasons: it can detect parasites not included in the PCR panel (such as Cystoisospora belli and helminths), and it can identify non-pathogenic protozoa that may be of interest for ecological or epidemiological studies [3]. This is particularly important for immunocompromised patients or returning travelers who may harbor a wider range of parasites.

Q3: What are the key steps in optimizing DNA extraction from protozoan oocysts and cysts in feces?

Successful DNA extraction from robust protozoan oocysts and cysts requires specific optimizations to overcome PCR inhibitors common in stool and to break down resistant cyst walls. Key amendments to the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit protocol that significantly improved sensitivity, particularly for Cryptosporidium, include [24]:

- Increasing the lysis temperature to the boiling point (100°C) for 10 minutes

- Extending the incubation time with the InhibitEX tablet to 5 minutes

- Using pre-cooled ethanol for nucleic acid precipitation

- Eluting in a small volume (50–100 µL) to concentrate the final DNA extract

PCR Troubleshooting Guide for Stool Samples

Table 1: Common PCR Issues and Solutions Specific to Stool-Based Protozoan Detection

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No PCR Product | PCR inhibitors from stool (e.g., bilirubin, bile salts, complex carbohydrates) co-purified with DNA [24]. | - Further purify DNA by alcohol precipitation or use a commercial cleanup kit [25].- Dilute the DNA template (1:10, 1:100) to dilute out inhibitors [24].- Use a DNA polymerase with high processivity and tolerance to inhibitors [26]. |

| Inefficient lysis of tough oocyst/cyst walls (e.g., Cryptosporidium, Giardia) [24]. | - Incorporate a mechanical disruption step (bead beating, sonication) or freeze-thaw cycles prior to extraction [24].- Increase lysis temperature and duration during extraction [24]. | |

| Suboptimal DNA concentration or purity. | - Re-purify DNA to remove residual salts, EDTA, or proteins [26].- Ensure the elution volume is small enough to yield a concentrated DNA sample [24]. | |

| Multiple or Non-Specific Bands | Mispriming due to suboptimal annealing. | - Increase the annealing temperature in 1–2°C increments [26] [25].- Use a hot-start DNA polymerase to prevent nonspecific amplification at lower temperatures [25]. |

| Excessive primer or DNA polymerase concentration. | - Optimize primer concentrations (typically 0.1–1 µM) [26].- Review and adjust the amount of DNA polymerase in the reaction [25]. | |

| Inconsistent Results Between Replicates | Non-homogeneous stool sample or uneven distribution of oocysts/cysts. | - Thoroughly homogenize the stool sample before aliquoting for DNA extraction.- Ensure reagent stocks and prepared reactions are mixed thoroughly [26]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Optimized DNA Extraction Protocol for Stool Samples

The following amended protocol for the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit has been validated to significantly improve DNA recovery from protozoan oocysts and cysts, raising sensitivity for Cryptosporidium from 60% to 100% in controlled studies [24].

Materials Needed:

- QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen)

- Variable temperature water bath or heat block

- Pre-cooled (4°C) 100% ethanol

- Microcentrifuge

Method:

- Lysis: Add approximately 200 mg of stool to the provided ASL buffer. Incubate at 100°C for 10 minutes to ensure efficient disruption of tough oocyst/cyst walls [24].

- Inhibition Removal: Transfer the supernatant to a new tube containing an InhibitEX tablet. Vortex vigorously and incubate at room temperature for 5 minutes to maximize binding of PCR inhibitors [24].

- DNA Binding: Centrifuge and transfer the supernatant to a new tube with proteinase K and AL buffer. Incubate at 70°C for 10 minutes.

- Precipitation: Add pre-cooled ethanol to the lysate, mix, and apply the mixture to the QIAamp spin column [24].

- Washing: Centrifuge and wash the column with AW1 and AW2 buffers as per the standard protocol.

- Elution: Elute the DNA in 50–100 µL of AE buffer or nuclease-free water. Using a small elution volume concentrates the DNA, improving the probability of detection in downstream PCR [24].

Diagnostic Workflow for Intestinal Protozoa

The following workflow diagram integrates molecular and microscopic methods for a comprehensive parasitological diagnosis, leveraging their respective strengths as evidenced in recent studies [3] [27].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Kits for Molecular Detection of Intestinal Protozoa

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| RCL2-CS100 Fixative | Tissue and sample preservation. | A non-crosslinking alternative to formalin; provides excellent histology and high-quality nucleic acids for PCR, CGH, and genotyping [23]. |

| AllPlex Gastrointestinal Panel (GIP) (Seegene) | Multiplex real-time PCR detection. | Targets 6 major protozoa (Giardia, Cryptosporidium, E. histolytica, D. fragilis, Blastocystis, Cyclospora). More sensitive than microscopy for targeted parasites [3]. |

| QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen) | Nucleic acid extraction from stool. | Requires protocol optimization (e.g., increased lysis temperature) for efficient DNA recovery from robust oocysts/cysts [24]. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Amplification of target DNA. | Reduces nonspecific amplification and primer-dimers, which is crucial for complex samples like stool [26] [25]. |

| InhibitEX Tablets / Buffer | Removal of PCR inhibitors. | Binds common fecal inhibitors (hemes, bilirubins, bile salts) during the DNA extraction process [24]. |

Within the specific context of protozoa research from stool samples, selecting an optimal DNA extraction method is a critical first step to reducing PCR inhibition and ensuring reliable results. The robust cell walls of protozoan cysts and oocysts, combined with the complex, inhibitor-rich nature of stool, present a significant challenge. This technical support guide benchmarks the three primary extraction technologies—Silica Spin Column, Silica Magnetic Bead, and Phenol-Guanidine methods—to help you establish a robust and efficient workflow for your research.

Technical Comparison: Extraction Methods at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of each DNA extraction method family, with a focus on their application in stool-based protozoa research.

Table 1: Technical Overview of DNA Extraction Methods

| Method | Core Principle | Best For | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silica Spin Column | DNA binds to silica membrane in a column under chaotropic salts; washed and eluted [28]. | Standardized protocols; high purity needs; manual processing [28] [5]. | Simpler and safer than phenol-chloroform; less prone to error; higher purity outputs [28]. | Potential loss of shorter DNA fragments; higher cost per sample; not easily automated [28]. |

| Silica Magnetic Beads | Silica-coated paramagnetic beads bind DNA; separated via magnetic rack [28] [29]. | High-throughput workflows; automation; rapid protocols [28] [30]. | Fastest technique; highly amenable to automation (e.g., 96-well plates); no centrifugation [28]. | Yield and purity similar to spin columns; requires specialized magnetic racks or automated systems [28]. |

| Phenol-Guanidine (e.g., Trizol) | Phase separation using acid-guanidinium-phenol-chloroform; RNA in aqueous phase, DNA at interphase [28] [31]. | Maximizing yield from difficult-to-lyse samples; cost-sensitive labs [32] [31]. | Essentially no loss of nucleic acids; low cost; effective on tough cell walls [28] [31]. | Time-consuming; use of toxic chemicals (phenol/chloroform); requires careful handling to avoid contamination [28] [31]. |

Performance Data & Benchmarking

The following tables consolidate quantitative findings from recent studies comparing the performance of different DNA extraction methods, with a focus on outcomes relevant to downstream molecular applications like PCR.

Table 2: Performance Comparison from Recent Studies

| Study Context | Methods Compared | Key Findings (Performance Metrics) | Conclusion for Stool/PCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA from Dried Blood Spots (DBS) [32] | • Chelex Boiling• Roche High Pure Kit (Column)• QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Column)• DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Column)• TE Boiling | • Chelex boiling yielded significantly higher DNA concentrations (p<0.0001) [32].• Roche Column showed higher DNA concentration than other column methods [32].• Smaller elution volumes (50µL) increased final DNA concentration significantly [32]. | For cost-effective PCR from micro-samples, a simple Chelex protocol can outperform more expensive column methods. |

| Bacterial Genomes for Nanopore Sequencing [29] | • ZymoBIOMICS DNA Miniprep (Beads/Column)• Nanobind CBB Big DNA Kit• Fire Monkey HMW-DNA Kit• Roche MagNaPure 96 (Automated Beads) | • ZymoBIOMICS provided the highest DNA purity (A260/A280) [29].• Nanobind and Fire Monkey kits yielded the longest read lengths (N50), crucial for genome assembly [29].• Roche MagNaPure (automated beads) performed well in genome assembly, especially for gram-negative bacteria [29]. | For long-read sequencing from complex samples, specialized HMW kits and automated bead systems provide superior results. |

| RNA Extraction from Blood & Oral Swabs [31] | • Manual Acid-Phenol-Chloroform (AGPC)• QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Column)• OxGEn Kit | • Manual AGPC yielded significantly higher RNA amounts (p<0.0001) [31].• Commercial Column Kits provided significantly higher purity (A260/A280) (p<0.0001) [31]. | The phenol method maximizes yield but at the cost of purity, which is critical for sensitive downstream PCR. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My PCR from stool samples for protozoa is consistently inhibited. Which method should I prioritize? Inhibition is often due to co-purification of contaminants. Silica-based methods (both spin column and magnetic beads) generally provide superior purity over phenol-chloroform extraction due to more rigorous wash steps [28] [29]. For stool samples, ensuring the protocol includes a robust lysis step to break open resilient protozoan cysts is also crucial. An automated magnetic bead system can offer the best combination of effective lysis, high purity, and consistency by minimizing human error [30] [29].

Q2: I need to process hundreds of stool samples for a large-scale study. What is the most scalable method? Silica-coated magnetic bead systems are the most scalable. They are uniquely suited for automation in 96-well plate formats, allowing you to process dozens of samples simultaneously with minimal hands-on time using robotic platforms like the Hamilton STAR, ThermoFisher KingFisher, or Roche MagNaPure 96 [28] [30] [29]. This makes them the gold standard for high-throughput diagnostics and surveillance studies.

Q3: Why would I choose a phenol-based method given its handling difficulties? The primary reasons are yield and cost. If your starting material is limited or the pathogen has a very tough cell wall (like some protozoan oocysts), phenol-chloroform can recover more nucleic acids than other methods [28] [31]. Furthermore, if you are in a resource-limited setting, the reagents for a phenol-chloroform extraction can be prepared locally at a much lower cost than purchasing commercial kits [31].

Q4: How does the choice of extraction method impact downstream next-generation sequencing (NGS)? The method directly impacts DNA fragment length and purity, which are critical for NGS. For short-read sequencing, standard silica columns are often sufficient. However, for long-read sequencing technologies (e.g., Nanopore), which require High Molecular Weight (HMW) DNA, gentler extraction methods are essential. Kits specifically designed for HMW DNA, such as the Fire Monkey HMW-DNA Kit or the Nanobind CBB Big DNA Kit, which minimize mechanical shearing, have been shown to produce longer reads and better genome assemblies [30] [29].

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 3: Common DNA Extraction Problems and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low DNA Yield | • Incomplete cell lysis (tough cyst/oocyst walls).• Overloaded binding column/magnetic beads.• Improper elution. | • Incorporate a more rigorous lysis step (e.g., bead-beating, extended proteinase K digestion) [3] [5].• Do not exceed the recommended input amount of starting material [33].• Ensure elution buffer is applied directly to the silica membrane/beads and incubated for 1-2 minutes before centrifugation [33]. |

| Low DNA Purity (Low A260/A280) | • Protein contamination (incomplete lysis or purification).• Residual organic solvents (phenol). | • Add an optional wash step with a buffer like 70% ethanol to remove salts and other contaminants [33].• In phenol-based methods, take care not to transfer the interphase or organic phase [28] [31]. |

| PCR Inhibition | • Co-purification of PCR inhibitors from stool (e.g., bile salts, complex carbohydrates).• Carryover of guanidine salts from lysis/binding buffer. | • Use a DNA extraction kit that includes specific inhibitors removal steps [34].• Ensure wash buffers contain ethanol and are completely removed. Avoid touching the column's sides with the pipette tip when discarding flow-through [33].• Dilute the DNA template or use a PCR additive like BSA to counteract mild inhibition [34]. |

| DNA Degradation | • Sample degradation before extraction (delayed preservation).• Nuclease activity during extraction. | • Stabilize stool samples immediately after collection using appropriate preservatives or freezing [33] [34].• Work quickly on ice and use nuclease-free reagents and tubes. |

Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Extraction

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen) | A widely used silica spin-column kit optimized for the efficient purification of genomic DNA from stool and its challenging inhibitors [34]. |

| Quick-DNA HMW MagBead Kit (Zymo Research) | A magnetic bead-based kit designed specifically to isolate pure High Molecular Weight (HMW) DNA, suitable for long-read sequencing from complex samples [30]. |

| TRIzol / QIAzol Reagents | Monophasic solutions of phenol and guanidine isothiocyanate used for the simultaneous liquid-phase separation of RNA, DNA, and proteins from various sample types [28] [31]. |

| MagNA Pure 96 System (Roche) | An automated, high-throughput nucleic acid purification system based on magnetic bead technology, ensuring reproducibility and minimal hands-on time [3] [29]. |

| Proteinase K | A broad-spectrum serine protease critical for digesting contaminating proteins and degrading nucleases during the lysis step, especially important for tough gram-positive bacteria and protozoan cysts [33]. |

Experimental Workflow & Decision Pathway

The following diagram summarizes the experimental workflow for a kit benchmarking study and provides a logical decision pathway for selecting the most appropriate extraction method based on your research goals.

The Role of Inhibitor Removal Steps and DNase Treatment in Purification Protocols

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is my stool PCR for protozoan parasites showing false negatives or inhibited amplification? PCR inhibition is a major challenge in stool-based molecular diagnostics. Fecal samples contain complex mixtures of substances that can co-purify with nucleic acids and inhibit downstream enzymatic reactions. Common inhibitors include bile salts, complex polysaccharides, lipids, and hemoglobin [35]. The robustness of your PCR assay is directly dependent on the efficacy of the DNA extraction protocol in removing these substances [36]. Selecting a method that includes dedicated wash steps and inhibitor removal technology is crucial for success.

2. How does DNase treatment benefit my RNA workflow from stool samples? While DNase is primarily used to remove contaminating genomic DNA from RNA preparations, its principles are relevant for managing inhibition. DNase I is an endonuclease that cleaves DNA into short fragments. In diagnostic workflows, its activity must be carefully controlled and then the enzyme must be completely removed or inactivated after digestion, as it can degrade your target nucleic acid in subsequent steps if left active. Effective removal often requires a dedicated inactivation step using a chelating agent like EDTA or a specific removal reagent [37] [38].

3. My nucleic acid yield from stool is low. What could be the cause? Low yield can stem from several factors:

- Incomplete Lysis: Protozoan cysts, like those of Giardia duodenalis, have tough walls that are difficult to disrupt. Protocols often require mechanical disruption (e.g., bead beating) or multiple freeze-thaw cycles to break them open effectively [35].

- Suboptimal Binding: The binding of nucleic acids to silica matrices is influenced by pH. A lower pH (e.g., ~4.1) reduces electrostatic repulsion between the negatively charged silica and DNA, significantly improving binding efficiency and yield [39].

- Overloaded Column: Using too much starting material can clog the silica membrane of spin columns, preventing efficient binding and elution. Always adhere to the recommended input amounts for your kit [40].

4. The purity of my extracted DNA is poor (low A260/A230 ratio). How can I improve it? A low A260/A230 ratio often indicates carryover of guanidine salts from lysis or wash buffers. These salts are potent PCR inhibitors. The solution is to ensure thorough washing of the silica membrane with ethanol-based wash buffers. Perform the recommended number of washes, and consider a brief centrifugation after the final wash to remove any residual liquid before elution [40] [41].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low DNA Yield | Inefficient lysis of tough cyst walls (e.g., Giardia, Cryptosporidium). | Incorporate mechanical disruption (bead beating [42]) or multiple freeze-thaw cycles [35]. |

| Suboptimal binding to silica matrix. | Ensure the binding buffer is at an optimal low pH (~4.1) to enhance DNA binding [39]. | |

| Column/membrane overloaded with sample or clogged with debris. | Do not exceed recommended input amounts. For fibrous samples, centrifuge the lysate to pellet debris before loading onto the column [40]. | |

| PCR Inhibition | Carry-over of PCR inhibitors (bile salts, polysaccharides, guanidine salts). | Use inhibitor removal reagents like polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) [42] or BSA [35]. Perform additional wash steps with 70-80% ethanol [41]. |

| Incomplete removal of contaminants during purification. | For difficult samples, a second purification using a different kit (e.g., QIAquick PCR purification kit) can improve purity [42]. | |

| DNA Degradation | DNase activity in the sample post-collection. | Store samples immediately at -80°C or in a preservative like potassium dichromate or ethanol [42]. Keep samples on ice during processing [40]. |

| Poor DNase Treatment | Inactivation of DNase I by improper buffers. | Ensure the reaction buffer contains the required co-factors (Mg²⁺ and Ca²⁺) for DNase I activity [37]. |

| Incomplete removal of DNase I after treatment. | After digestion, chelate Mg²⁺ ions with EDTA and/or use a specialized DNase Removal Reagent to sequester the enzyme before proceeding to cDNA synthesis [37]. |

Experimental Protocols for Inhibitor Management

Protocol 1: CDC-Recommended DNA Extraction from Fecal Specimens

This protocol from the CDC DPDx outlines a comprehensive procedure for extracting parasite DNA from stool, incorporating key inhibitor removal steps [42].

Special Equipment:

- FastPrep FP120 Disrupter or similar bead-beating instrument.

Key Reagents and Functions:

- Lysing Matrix Multi Mix E: Contains silica beads for mechanical lysis of tough cyst walls.

- CLS-VF (Cell Lysis Solution): A chaotropic salt-based solution to denature proteins and inactivate nucleases.

- PPS (Protein Precipitation Solution): Precipitates and removes proteins from the lysate.

- PVP (Polyvinylpyrrolidone): Added to a final concentration of 0.1-1% to bind to and remove polyphenolic compounds and other PCR inhibitors.

- Binding Matrix: Silica matrix for nucleic acid binding.

- SEWS-M (Salt/Ethanol Wash Solution): Washes and desalts the bound nucleic acids.

- DES (DNA Elution Solution): Low-salt buffer (e.g., TE or water) to elute purified DNA.

Procedure:

- Wash: Centrifuge 300-500 µL of stool specimen and suspend the pellet in PBS-EDTA. Repeat this wash two more times.

- Lysate Preparation: Transfer 300 µL of the washed sample to a tube containing Lysing Matrix E. Add 400 µL of CLS-VF, 200 µL of PPS, and PVP.

- Mechanical Lysis: Homogenize using the FP120 disrupter at a speed of 5.0-5.5 for 10 seconds.

- Clarify: Centrifuge the lysate for 5 minutes at 14,000 × g and transfer 600 µL of supernatant to a new tube.

- Bind DNA: Add 600 µL of Binding Matrix to the supernatant, mix by inversion, and incubate for 5 minutes at room temperature.

- Wash: Pellet the binding matrix, pour off the supernatant, and resuspend the pellet in 500 µL of SEWS-M. Centrifuge and discard the supernatant.

- Elute: Resuspend the matrix in 100 µL of DES, incubate for 2-3 minutes, and centrifuge. Transfer the supernatant (containing DNA) to a clean tube.

- Optional Further Purification: If PCR inhibition persists, purify the eluted DNA using a QIAquick PCR purification kit per the manufacturer's instructions [42].

Protocol 2: DNase I Treatment for DNA Contamination Removal

This protocol is adapted for treating DNA contaminants in RNA samples, a common issue in gene expression studies from complex samples [37] [38].

Reaction Setup:

- For a 100 µL reaction, combine:

- RNA sample (diluted to ~100 µg/mL total nucleic acid).

- 10X DNase I Buffer (Final concentration: 100 mM Tris pH 7.5, 25 mM MgCl₂, 5 mM CaCl₂).

- 2 units of DNase I per ~10 µg of RNA.

- Mix gently and incubate at 37°C for 30-60 minutes.

DNase I Inactivation/Removal:

- EDTA Method: Add EDTA to a final concentration of 5-10 mM to chelate Mg²⁺ and stop the reaction. This is suitable if the RNA will be used immediately.

- Purification Method (Recommended): Use a dedicated DNase Removal Reagent. Add the reagent to the reaction mix, incubate for a few minutes, and pellet the reagent by centrifugation. The purified RNA is in the supernatant. This method effectively removes the enzyme and cations, preventing residual activity and RNA degradation [37].

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Extraction Method Sensitivities for Protozoan Parasites

| Parasite | Extraction Method / Protocol Combination | Reported Detection Limit | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclospora cayetanensis | Extraction-free, filter-based (FTA filters) | 10 - 30 oocysts per 100 g of raspberries | [43] |

| Cryptosporidium parvum | FTD Stool Parasite + Nuclisens Easymag extraction | 100% detection in comparative study | [36] |

| Giardia duodenalis | Phenol-Chloroform Isoamyl Alcohol (PCI) | 70% diagnostic sensitivity | [35] |

| Giardia duodenalis | QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit | 60% diagnostic sensitivity | [35] |

Table 2: Impact of DNA Extraction Method on Microbial Community Analysis

| Sample Type | Extraction Kit | Key Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black-capped Chickadee Feces | Five different commercial kits | All kits worked, but influenced measured diversity and composition of microbiota | [44] |

| Blue Tit Feces | Five different commercial kits | Only two of five kits successfully recovered DNA | [44] |

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Troubleshooting PCR Inhibition in Stool Samples

Inhibition Troubleshooting Path

Diagram 2: DNase Treatment and Removal Workflow

DNase Treatment Process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Inhibitor Removal

Table 3: Key Reagents for Effective Nucleic Acid Purification from Complex Samples

| Reagent / Material | Function / Principle | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Chaotropic Salts (e.g., Guanidine Thiocyanate) | Denature proteins, inactivate nucleases, and facilitate binding of nucleic acids to silica matrices. | Core component of lysis/binding buffers in most silica-based kits (e.g., FastDNA Kit [42], PowerSoil [44]). |

| Inhibitor Removal Reagents (e.g., PVP, BSA) | Bind to specific classes of PCR inhibitors (e.g., polyphenolics, humic acids) present in stool and environmental samples. | Adding PVP to the lysis buffer for stool DNA extraction [42]. BSA can be added directly to PCR mixes [35]. |

| Silica Membranes / Magnetic Beads | Solid matrix that binds nucleic acids in the presence of chaotropic salts, allowing for efficient washing and elution. | The core of spin-column technology (e.g., QIAamp kits [35]) and magnetic bead-based automated systems (e.g., MagMAX [44], Nuclisens Easymag [36]). |

| Mechanical Disruption Aids (e.g., Ceramic/Silica Beads) | Physically break open tough cell and cyst walls through bead-beating, ensuring complete lysis and DNA release. | Essential for breaking Giardia cysts [35] and for homogenizing stool samples in the FastDNA Kit protocol [42]. |

| DNase I Enzyme | Endonuclease that degrades double-stranded and single-stranded DNA. Requires Mg²⁺ and Ca²⁺ for optimal activity. | Removal of contaminating genomic DNA from RNA preparations prior to RT-PCR to prevent false positives [37]. |

Why target multi-copy genes? In molecular diagnostics, the sensitivity of a PCR assay is fundamentally limited by the number of target sequences present in a sample. For low-abundance targets or challenging sample types like stool, targeting genomic loci that are present in multiple copies distributed across the genome dramatically enhances detection capability. This approach is particularly valuable for detecting intestinal protozoa in stool samples, where target organisms may be present in low numbers and PCR inhibitors are abundant.

The core principle is straightforward: by targeting sequences that repeat multiple times within a single organism's genome, the effective target concentration for each reaction increases significantly. This provides a substantial advantage over single-copy gene targets, especially when analyzing samples with minimal pathogen load or substantial PCR inhibition. Multicopy targets minimize stochastic sampling errors and improve assay reliability by ensuring that more template molecules are available for amplification in each reaction [45].

Theoretical Foundation and Design Principles

Fundamental Advantages of Multi-Copy Targets

Enhanced Sensitivity and Reduced Stochastic Effects When working with low-template DNA, targeting single-copy genes risks underestimating the true DNA amount due to stochastic sampling errors. Modern forensic qPCR assays, which face similar sensitivity challenges, analyze genomic loci present in many copies per genome that are uniformly distributed across several chromosomes. This ensures the quantitation reflects the overall DNA amount regardless of which genome fraction is sampled [45].

The statistical advantage is clear: if an organism has 100 copies of a target sequence versus a single-copy gene, the probability of detecting the organism in a sample with low pathogen load increases exponentially. For intestinal protozoa detection in stool samples, this sensitivity boost is crucial for identifying low-level infections that might be missed by other methods [3] [46].

Improved Tolerance to Inhibitors Complex samples like stool contain numerous PCR inhibitors including complex polysaccharides, lipids, proteins, and metal ions. These substances interfere with PCR amplification through various mechanisms, including inhibition of DNA polymerase activity, fluorescent signaling interference, template degradation or sequestration, and chelation of essential metal ions [47] [48].

With multi-copy targets, the higher initial template concentration means reactions can withstand greater dilution to reduce inhibitor concentration while maintaining detectable signal. This inherent robustness is particularly valuable for stool-based protozoa detection where inhibitor burden is high [47].

Selection of Appropriate Multi-Copy Targets

Ribosomal RNA Genes Ribosomal RNA genes (rDNA) represent ideal targets for protozoa detection due to their high copy number in parasitic genomes. Multiple studies on intestinal protozoa detection have leveraged this advantage [46] [5]. The ribosomal RNA operon is typically present in hundreds of copies per genome, providing abundant template for amplification.

Other Multi-Copy Elements Beyond rDNA, researchers can target other repetitive genomic elements specific to their organism of interest. The key consideration is ensuring these elements are uniformly distributed and conserved enough to allow reliable primer-probe design while being unique to the target organism to maintain specificity [45].

Table 1: Comparison of Target Types for PCR Detection

| Target Type | Copies/Genome | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-copy genes | 1 | Specific, easy to design | Prone to stochastic effects, lower sensitivity |

| Ribosomal RNA genes | 100-500 | High sensitivity, conserved | Potential cross-reactivity needs careful validation |

| Distributed repetitive elements | 10-100 | High sensitivity, specific | May be less conserved |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Primer and Probe Design Methodology

Conserved Region Identification The protocol for designing primers and probes for multi-copy targets begins with identifying highly conserved regions within the repetitive elements. As demonstrated in the implementation of qPCR assays for intestinal protozoa including the first molecular detection of Chilomastix mesnili, researchers retrieved multiple sequences for the target region from databases like NCBI using BLASTN [46].

These sequences were aligned to identify conserved regions, which were then compared against the entire database to assess similarity to non-target organisms, excluding nonspecific sequence similarities. This step ensures species-specific detection despite targeting conserved multi-copy elements [46].

Design Parameters and Validation For the C. mesnili assay, primers and probes were selected meeting specific criteria: GC content of approximately 50%, length between 20-24 bases, and an estimated melting temperature (Tm) of ~58°C [46]. All proposed primer and probe sequences should undergo individual BLASTN searches to confirm their uniqueness to the target organism.

The development process includes testing primer and probe sequences using confirmed positive samples and plasmid controls containing the target sequence. Cycle conditions and reagent concentrations are refined to optimize the signal-to-noise ratio based on both plasmid standards and biological samples [46].