Overcoming PCR Inhibition in Stool Samples: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Molecular Diagnostics

Accurate molecular analysis of stool samples is critical for clinical diagnostics, gut microbiome research, and drug development.

Overcoming PCR Inhibition in Stool Samples: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Molecular Diagnostics

Abstract

Accurate molecular analysis of stool samples is critical for clinical diagnostics, gut microbiome research, and drug development. However, the pervasive challenge of PCR inhibition significantly compromises sensitivity and reliability. This article provides a systematic framework for researchers and scientists to understand, identify, and overcome PCR inhibition. We explore the foundational sources of inhibitors in stool, present optimized methodological approaches for nucleic acid extraction and assay design, detail practical troubleshooting strategies, and review validation techniques for comparative method analysis. By integrating the latest evidence and protocols, this guide aims to empower professionals in achieving consistent and reproducible molecular results from complex fecal specimens.

Understanding the Enemy: Foundational Principles of PCR Inhibitors in Stool

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) inhibition is a major challenge in molecular diagnostics and research, particularly when analyzing complex samples like stool. Inhibitors are substances that interfere with the biochemical processes of PCR, leading to reduced sensitivity (false negatives) and specificity (false positives or non-specific amplification) [1] [2]. In stool samples, a wide array of organic and inorganic compounds can act as potent inhibitors, compromising the accuracy and reliability of your results [3] [4].

Mechanisms of Action: PCR inhibitors can disrupt amplification through several mechanisms:

- Direct DNA Polymerase Inhibition: Many inhibitors, such as humic substances, bile salts, and complex polysaccharides, bind directly to the DNA polymerase enzyme, degrading it or blocking its active center [1] [4].

- Interaction with Nucleic Acids: Inhibitors like collagen and humic acid can bind to the template DNA, making it unavailable for primer binding and elongation [1] [2].

- Cofactor Chelation: Substances such as EDTA and heparin chelate or compete for magnesium ions (Mg²⁺), an essential co-factor for DNA polymerase activity [1] [3]. Some inhibitors may also quench the fluorescence signals used in real-time qPCR and digital PCR (dPCR) detection systems [1].

Quantitative Impact of Inhibition on Assay Performance

The presence of inhibitors can significantly skew quantitative results and reduce detection sensitivity. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from research on PCR inhibition in fecal samples.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of PCR Inhibition in Fecal Samples

| Metric | Impact Without Inhibition Management | Impact With 5-Fold Dilution of DNA Extract | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rate of Inhibition | 19.94% of fecal DNA extracts showed evidence of inhibition | Not Applicable | [3] |

| Test Sensitivity | 55% (compared to fecal culture) | 80% (compared to fecal culture) | [3] |

| DNA Quantification | Underestimation due to suppression of amplification | 3.3-fold average increase in quantified DNA | [3] |

| Predictors of Inhibition | DNA extracts with higher DNA and protein content had significantly higher odds (19.33x and 10.94x, respectively) of showing inhibition | Not Applicable | [3] |

Inhibition rates can vary significantly depending on the sample matrix. One large-scale study of clinical specimens found an overall inhibition rate of 0.87% when the inhibition control was added pre-extraction. However, for certain sample types like urine and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue, inhibition rates were notably higher [5].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guide

FAQ 1: How can I detect PCR inhibition in my experiments? Inhibition can be detected through several methods. The most robust is the use of an Internal Amplification Control (IAC). An IAC is a non-target DNA sequence added to each reaction. If the IAC fails to amplify while a positive external control works, it indicates the presence of an inhibitor in the sample [3]. Other signs include a reduction in amplification efficiency, an increase in quantification cycle (Cq) values in qPCR, complete amplification failure, or inconsistent results between replicates [1] [6] [4].

FAQ 2: What are the most common PCR inhibitors in stool samples? Stool is a complex matrix containing numerous potential inhibitors, including:

- Complex polysaccharides [2] [3]

- Bile salts [5] [3]

- Bacterial metabolites and porphyrins [2]

- Calcium, hemoglobin derivatives, and immunoglobulin G [1] [3]

FAQ 3: My PCR shows no product. Is this always due to inhibition? No. A lack of product can have multiple causes. Before concluding inhibition is the issue, systematically check the following [7] [6]:

- Template DNA: Verify quantity, quality, and integrity.

- Reagent Integrity: Ensure all reagents, especially primers, dNTPs, and polymerase, are active and not degraded.

- Thermal Cycler Programming: Confirm that temperatures and times for denaturation, annealing, and extension are correct.

- Primer Design: Check for specificity and the absence of self-complementarity.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for PCR Inhibition

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No amplification, but internal control also fails | Severe PCR inhibition | Dilute the DNA template 1:5 or 1:10 [3]. Add Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) to a final concentration of 0.1-0.5 μg/μL [2] [4]. Use an inhibitor-tolerant DNA polymerase blend [1] [6]. |

| High Cq value, low yield, or reduced sensitivity | Moderate PCR inhibition | Dilute DNA template [3]. Increase the amount of DNA polymerase in the reaction [7]. Use a PCR additive like BSA or betaine [4]. Switch to digital PCR (dPCR), which is less affected by moderate inhibitors [1]. |

| Non-specific bands or primer-dimer formation | Reaction conditions compromised by inhibitors | Use a hot-start DNA polymerase to prevent non-specific amplification at low temperatures [7] [6] [4]. Optimize Mg²⁺ concentration and annealing temperature [7] [6]. |

| Inaccurate DNA quantification via spectrophotometry | Co-purified inhibitors like humic substances affecting UV absorption | Use a fluorescence-based quantification method (e.g., Picogreen, SYBR Green), which is more specific for DNA and less affected by contaminants [2]. |

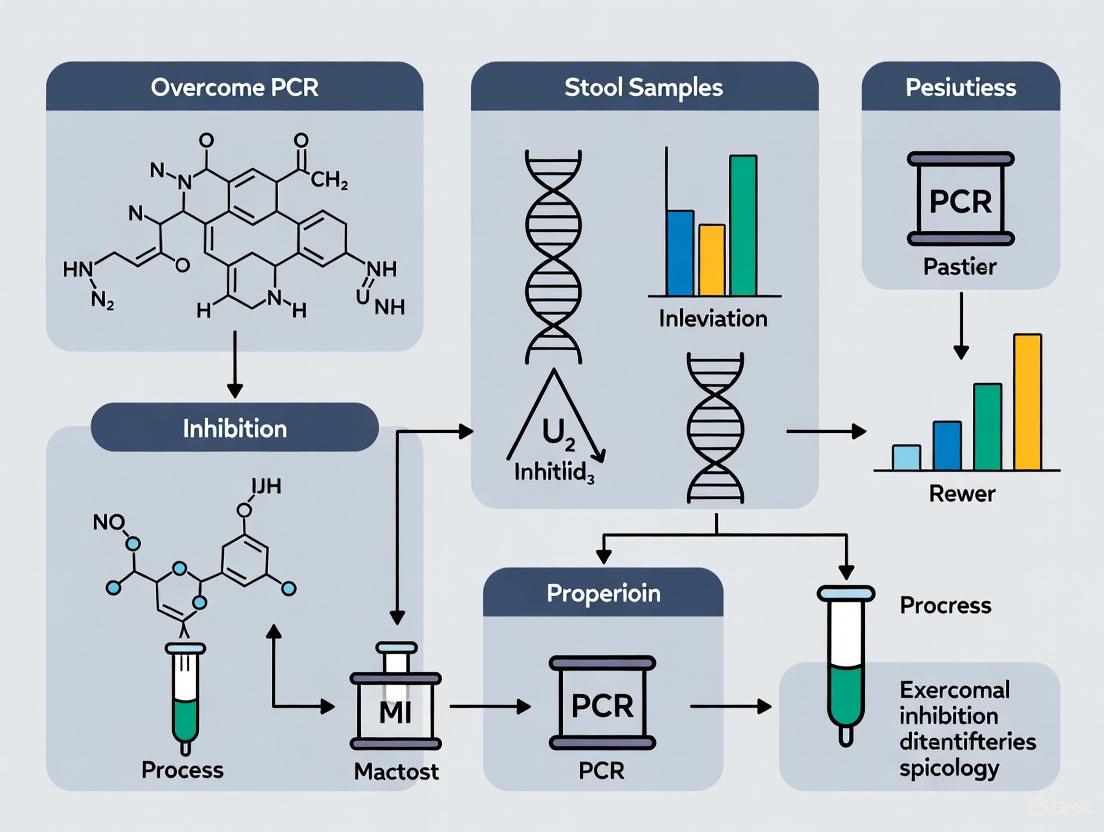

Experimental Workflow to Overcome Inhibition

The diagram below outlines a logical workflow for diagnosing and overcoming PCR inhibition in stool sample analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Overcoming PCR Inhibition

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Binds to inhibitors, preventing them from interacting with the DNA polymerase or nucleic acids [2] [4]. | Add to a final concentration of 0.1-0.5 μg/μL in the PCR mix to neutralize a wide range of inhibitors in stool extracts. |

| Inhibitor-Tolerant DNA Polymerase | Specially engineered enzyme blends with high resistance to common PCR inhibitors [1] [6]. | Use as a direct replacement for standard Taq polymerase when working with crude or difficult-to-purify DNA extracts. |

| dPCR Master Mix | Reagents optimized for digital PCR, a technique less affected by inhibitors due to sample partitioning and end-point analysis [1]. | For absolute quantification of target DNA in inhibited samples where qPCR results are unreliable. |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) or Betaine | Additives that can help destabilize secondary structures in DNA and mitigate the effects of some inhibitors [4]. | Can be added to the PCR mix to improve amplification efficiency from inhibitor-rich environmental samples. |

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) inhibition remains a significant challenge in molecular diagnostics and research, particularly when working with complex biological matrices like human stool. The presence of inhibitors in fecal samples can lead to false-negative results, reduced sensitivity, and unreliable data, ultimately compromising experimental outcomes and diagnostic accuracy. This technical support guide addresses the most common sources of PCR inhibitors in stool samples and provides evidence-based troubleshooting strategies to overcome these challenges. Understanding the chemical nature and origin of these inhibitors is the first step toward developing effective protocols for their removal or neutralization, thereby enhancing the reliability of PCR-based assays in stool research.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the most common PCR inhibitors found in stool samples?

The primary PCR inhibitors in stool samples include complex polysaccharides, bile salts, and various dietary components. Research has specifically identified:

- Complex polysaccharides: These are frequently derived from plant material in the diet and are a major class of PCR inhibitors in feces [8] [9] [10].

- Bile salts: These digestive components have been specifically studied and shown to partition in aqueous two-phase systems, confirming their role as PCR inhibitors [11].

- Dietary components: The presence of inhibitors correlates with dietary changes. One study found no inhibition in infants younger than 6 months, but inhibition became prevalent in 17% of samples from infants aged 6-24 months who had begun consuming solid foods, suggesting a direct link to diet [12] [13].

How can I detect the presence of PCR inhibitors in my sample?

The most reliable method for detecting inhibitors is to use an internal control. This involves spiking a known quantity of target DNA or RNA (non-competitive control) into the extracted sample nucleic acid and performing amplification. A significant decrease in amplification efficiency or a delay in quantification cycle (Cq) compared to a clean control sample (e.g., spiked water) indicates the presence of inhibitors [12] [13]. Many commercial PCR kits include an internal control for this purpose.

What is the most effective way to remove polysaccharide inhibitors?

A comparative study of DNA extraction methods for intestinal parasite detection found that a commercial kit incorporating a bead-beating step was most effective. The QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QB) demonstrated a significantly higher PCR detection rate (61.2%) compared to the conventional phenol-chloroform method (8.2%) and a similar kit without bead-beating [14]. This highlights the importance of both chemical lysis and mechanical disruption for efficient removal of inhibitors and access to microbial DNA.

Troubleshooting Guide: Overcoming PCR Inhibition

Problem: Inconsistent or Failed PCR Amplification from Stool DNA

This is a multi-step diagnostic and corrective process. The following workflow outlines a systematic approach to identify and resolve the issue.

Step 1: Confirm Inhibition

As outlined in the FAQ, perform a spike test with an internal control. If inhibition is confirmed, proceed to the following steps.

Step 2: Optimize DNA Extraction

The choice of DNA extraction method is critical. Research demonstrates that methods incorporating silica-based purification and mechanical lysis are highly effective at removing inhibitors.

- Evidence: Silica membranes significantly reduce inhibition rates. One study on respiratory and non-respiratory specimens (including stool) showed that adding a silica membrane purification step reduced the overall PCR inhibition rate from 12.5% to 1.1% [15].

- Protocol: Solid-Phase Extraction with Silica Membranes [16] [15]:

- Cell Lysis: Use a chaotropic salt-based lysis buffer (e.g., containing guanidinium isothiocyanate) to disrupt cells and inactivate nucleases.

- Nucleic Acid Adsorption: Bind the DNA to the silica membrane in the presence of chaotropic salts.

- Washing: Pass wash buffers containing ethanol or competitive agents through the membrane to remove proteins, salts, and other contaminants, including inhibitory polysaccharides.

- Elution: Release the pure nucleic acid in a low-salt buffer or water.

- Recommendation: For stool samples, select a commercial kit designed for fecal DNA extraction that includes a bead-beating step for mechanical disruption of hardy parasite eggs and microbial cells [14].

Step 3: Employ PCR Enhancers

Adding specific compounds to the PCR reaction can neutralize remaining inhibitors.

- Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA): Effectively binds to and neutralizes a range of inhibitors. One study found that the addition of BSA eliminated the effect of inhibitors in stool samples, making all previously inhibited samples positive [12] [13].

- T4 Gene 32 Protein (gp32): This single-stranded DNA-binding protein can stabilize DNA and prevent the action of inhibitors like humic acids [17].

- Other Enhancers: Additives like TWEEN-20 (a detergent), DMSO, and glycerol can also help counteract inhibition by various mechanisms, such as destabilizing secondary structures or protecting the polymerase [17].

The table below summarizes the effectiveness of various enhancers tested in a wastewater study (a similarly complex matrix), providing a reference for expected outcomes [17].

Table 1: Effectiveness of PCR Enhancers in a Complex Matrix

| Enhancer | Concentration Tested | Reported Effect on Cq Value | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| BSA | 0.1 - 1 µg/µL | No change or slight improvement | Binds to and neutralizes inhibitors |

| T4 gp32 | 50 - 200 ng/µL | No change or slight improvement | Binds single-stranded DNA, stabilizes reaction |

| TWEEN-20 | 0.1 - 1% | No change | Counteracts inhibitory effects on Taq polymerase |

| DMSO | 1 - 10% | No change or slight deterioration | Lowers DNA melting temperature (Tm) |

| Formamide | 1 - 3% | Deterioration | Destabilizes DNA helix |

| Glycerol | 1 - 10% | Deterioration | Protects enzymes from degradation |

Step 4: Dilute the Sample

A simple and often effective strategy is to dilute the extracted nucleic acid. This reduces the concentration of co-eluted inhibitors below their inhibitory threshold.

- Consideration: While a 10-fold dilution is common, it also dilutes the target DNA, which can reduce sensitivity and lead to underestimation of viral or bacterial load, especially when target abundance is low [17]. This method is best used when the target is expected to be at a high concentration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Overcoming PCR Inhibition in Stool

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Key Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit | DNA purification via silica membrane & bead-beating | Most effective for diverse intestinal parasites; superior inhibitor removal [14] |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | PCR enhancer that binds inhibitors | Easy, cost-effective addition to PCR mix to neutralize inhibitors [12] [13] |

| PEG-Dextran Aqueous Two-Phase System | Sample preparation to partition inhibitors | Separates bacteria (bottom phase) from inhibitors (top phase) [11] |

| Silica Membranes/Columns | Solid-phase nucleic acid extraction | Effectively removes polysaccharides and other contaminants [16] [15] |

| T4 Gene 32 Protein (gp32) | PCR enhancer that binds ssDNA | Protects DNA and counters inhibitors like humic acids [17] |

| Inhibitor Removal Kits | Specifically designed to remove humics, tannins, etc. | Contains column matrix for efficient removal of common environmental inhibitors [17] |

Key Experimental Protocols

This method separates PCR inhibitors from bacterial cells prior to DNA extraction.

- Prepare the System: Create an aqueous two-phase system with final concentrations of 8% (w/w) PEG 4000 and 11% (w/w) Dextran 40 in your fecal sample suspension.

- Mix and Separate: Vortex the mixture thoroughly and then centrifuge it to achieve phase separation.

- Collect Phase: The PEG-rich top phase will concentrate most PCR inhibitors (like bile salts), while the bacterial cells partition to the dextran-rich bottom phase and interface.

- Proceed with DNA Extraction: Use the bottom phase for your standard DNA extraction protocol (e.g., with a silica-based kit). This method has been shown to improve PCR detection sensitivity by 3-5 orders of magnitude for H. pylori in inoculated fecal samples.

This protocol validates your PCR results by detecting the presence of inhibitors.

- Extract Nucleic Acid: Perform your standard DNA/RNA extraction from the stool sample.

- Spike the Sample: Take an aliquot of the eluted nucleic acid and spike it with a known amount of a non-competitive control (e.g., purified virus RNA or a plasmid containing a unique target sequence).

- Run Parallel PCR: Amplify the spiked sample and a positive control (the same amount of spike added to clean water) using the same PCR conditions.

- Analyze Results: A significant increase in Cq value (e.g., >3 cycles) or a failure to amplify in the spiked sample compared to the positive control indicates the presence of PCR inhibitors in the extracted nucleic acid.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the most common sources of PCR inhibitors in stool samples? Stool samples are particularly challenging as they contain a complex mixture of undigested food, bile salts, bilirubin, complex polysaccharides, and various bacteria. Furthermore, parasites themselves can be a source of inhibition due to their difficult-to-lyse structures, such as strong eggshells and hard, sticky cuticles [14].

What are the core molecular mechanisms by which inhibitors disrupt PCR? PCR inhibitors interfere with amplification through two primary mechanisms:

- Interaction with the DNA Template: Some inhibitors bind directly to single or double-stranded DNA, making the template unavailable for the polymerase [18].

- Interference with DNA Polymerase: Inhibitors can degrade DNA polymerase, bind to it reversibly, or reduce the availability of essential co-factors like Mg2+ ions, which are crucial for polymerase activity [18].

Why can a sample positive by microscopy yield a false-negative PCR result? This is a common issue caused by PCR inhibitors. Even if intact parasites or their DNA are present in the sample (visible under a microscope), co-purified inhibitors can prevent the PCR reaction from proceeding, leading to a false negative. This underscores the importance of effective DNA extraction and inhibitor removal [14].

How can I verify that my PCR failure is due to inhibition? The most reliable method is a spike test (or inhibition test). After extracting DNA, add a known quantity of a control DNA template (e.g., a plasmid with a specific target gene) to your sample's extracted DNA and run a PCR. If the control DNA fails to amplify, it indicates the presence of PCR inhibitors in your sample. If it amplifies successfully, then the original negative result is likely a true negative [14].

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving PCR Inhibition

Problem: Consistent PCR Failure with Stool Samples

Potential Cause: The DNA extraction method is inefficient at lysing hardy parasite structures (e.g., Ascaris eggs) and/or removing common stool-derived inhibitors.

Solutions:

- Optimize your DNA Extraction Protocol: Incorporate a mechanical disruption step. A study comparing methods found that a phenol-chloroform protocol with a bead-beating step (PB) yielded ~4 times more DNA than a kit without one. However, for the highest detection rates, a specialized kit like the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QB), which includes inhibitor removal technology, is recommended [14].

- Use a Kit Designed for Inhibitor-Rich Samples: Commercial kits are optimized for this purpose.

- QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QB): In a comparative study, this kit showed the highest PCR detection rate (61.2%) for a range of intestinal parasites, outperforming other methods [14].

- PowerClean DNA Clean-Up Kit: Another study specifically evaluating inhibitor removal found this kit and the DNA IQ System to be very effective at removing a wide array of known inhibitors, leading to more complete STR profiles [19] [20].

- Modify the PCR Reaction:

- Increase DNA Polymerase Concentration: Using a higher concentration of a robust, inhibitor-resistant DNA polymerase can sometimes overcome mild inhibition [18].

- Add Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA): BSA is known to mitigate the effects of various PCR inhibitors, particularly in samples like blood, and can be a valuable additive [18].

- Dilute the DNA Template: A simple dilution of the extracted DNA (e.g., 1:5 or 1:10) can reduce the concentration of inhibitors to a level that no longer affects the reaction. However, this also dilutes the target DNA, so it is not suitable for low-copy-number samples [20].

Quantitative Comparison of DNA Extraction Methods for Stool

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from a study comparing four DNA extraction methods for the PCR detection of intestinal parasites in 85 stool samples [14].

| Method | Description | Relative DNA Yield | PCR Detection Rate | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | Phenol-Chloroform | ~4x higher | 8.2% | Lowest detection rate; only detected S. stercoralis. |

| PB | Phenol-Chloroform + Bead-Beating | ~4x higher | Not Specified | High yield, but detection rate lower than QB. |

| Q | QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit | Baseline | Not Specified | Standard kit without specialized inhibitor removal. |

| QB | QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit | Baseline | 61.2% | Highest detection rate; effective for all parasites tested. |

Experimental Protocol: DNA Extraction with Bead-Beating and Inhibitor Removal

This protocol is adapted from the methods described in the search results for effectively handling tough parasite cysts and inhibitor-rich stool samples [14].

Title: Protocol for DNA Extraction from Stool Samples Using Mechanical Lysis and Silica-Binding

Principle: This method uses mechanical disruption via bead-beating to break down sturdy parasitic structures, followed by chemical lysis and the binding of DNA to a silica membrane in the presence of reagents that wash away PCR inhibitors.

Materials:

- QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QIAGEN) or equivalent.

- 0.5 mm glass beads (sterile)

- Microcentrifuge tubes (2 mL)

- Vortex mixer with horizontal (tube-lying) attachment

- Microcentrifuge

- Ethanol (96-100%)

- Stool sample preserved in 70% ethanol

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Wash approximately 200 mg of stool sample preserved in 70% ethanol three times with sterile distilled water to remove the preservative. Aliquot 200 mg into a 2 mL microcentrifuge tube.

- Mechanical Lysis: Add 250 mg of sterile 0.5 mm glass beads and 400-600 µL of lysis buffer (from the kit, or a standard lysis solution with proteinase K) to the tube.

- Homogenization: Secure the tubes in a horizontal vortex adapter and vortex at maximum speed for 10 minutes, or until the stool sample is fully homogenized.

- Thermal Lysis: Incubate the homogenized mixture at 65°C for 10-30 minutes, then at 95°C for 5-10 minutes to complete the lysis and inactivate proteinase K and other enzymes.

- Inhibitor Removal & DNA Binding: Follow the specific kit instructions. Typically, this involves transferring the supernatant to a new tube, adding a binding solution, and loading the mixture onto a silica membrane spin column. Contaminants and inhibitors are washed away through a series of centrifugation steps with wash buffers containing ethanol.

- DNA Elution: Elute the pure, inhibitor-free DNA from the membrane using a low-salt buffer or nuclease-free water (50-100 µL).

Molecular Pathways of PCR Inhibition

The following diagram illustrates the key pathways through which common inhibitors disrupt the PCR process.

Experimental Workflow for Overcoming Inhibition

This workflow outlines a systematic, evidence-based approach to diagnosing and solving PCR inhibition in stool sample research.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and kits essential for effective DNA extraction and inhibition removal in stool sample research.

| Reagent / Kit | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit | A comprehensive solution for simultaneous mechanical and chemical lysis, and removal of PCR inhibitors from difficult stool samples via a silica membrane [14]. |

| PowerClean DNA Clean-Up Kit | Used as a post-extraction clean-up step to specifically remove a wide range of known PCR inhibitors (humic acid, hematin, etc.) from existing DNA extracts [19] [20]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | An additive to the PCR master mix that binds to and neutralizes certain classes of inhibitors, preventing them from interfering with the DNA polymerase [18]. |

| Proteinase K | A broad-spectrum serine protease used during lysis to degrade contaminating proteins and nucleases, facilitating better DNA release and purity [14]. |

| Glass Beads (0.5 mm) | Used for mechanical disruption (bead-beating) to break open resilient parasitic cysts, spores, and eggshells that are resistant to chemical lysis alone [14]. |

| Inhibitor-Resistant DNA Polymerase | Engineered polymerases that are more tolerant to common inhibitors found in complex samples, providing an additional layer of protection against PCR failure [18]. |

How can I tell if my stool sample PCR is inhibited?

Inhibition in qPCR can be detected by analyzing both the quantitative cycle (Cq) values and the shape of the amplification curves. Key indicators include:

- Delayed Cq Values: A consistent increase in Cq values across samples, including controls, suggests general inhibition. This can be confirmed using an Internal PCR Control (IPC); if the IPC Cq is also delayed, inhibition is likely [21] [22].

- Abnormal Amplification Curves: Curves may appear flattened, lack a clear exponential phase, or fail to cross the detection threshold. This can indicate interference with the DNA polymerase or fluorescence detection [22].

- Reduced Amplification Efficiency: When creating a standard curve from serial dilutions, an efficiency outside the ideal 90–110% range (slope steeper than -3.1 or shallower than -3.6) suggests inhibition is affecting the reaction kinetics [21] [22].

The table below summarizes these key indicators and their interpretations.

Table: Key Indicators of PCR Inhibition in qPCR

| Indicator | Observation | Possible Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Cq Shift | Delayed Cq in test samples and Internal PCR Control (IPC) | General inhibition affecting polymerase activity or primer binding [21] [22] |

| Amplification Efficiency | Standard curve slope outside -3.1 to -3.6 range | Inhibition skewing reaction kinetics, leading to underestimation [21] |

| Curve Morphology | Flattened curve, low signal, or failure to reach threshold | Fluorescence quenching or severe polymerase inhibition [22] |

What does the data show about inhibition in stool samples?

Stool samples are a complex matrix known to contain PCR inhibitors. Research specifically on infant stool samples has quantified this challenge.

One study found that inhibitors were present in a significant proportion of samples from 3- to 24-month-old children, with 12% showing complete inhibition and 19% showing partial inhibition [12]. A striking finding was that inhibition was age-related: none of the samples (0/31) from infants younger than 6 months showed inhibition, compared to 17% of samples (13/77) from older infants (6-24 months), suggesting a link to dietary changes away from exclusive breastfeeding [12].

The table below summarizes the quantitative findings from this study.

Table: PCR Inhibition in Infant Stool Samples [12]

| Age Group | Sample Size | Complete Inhibition | Partial Inhibition | No Inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 6 months | 31 | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 100% (31) |

| 6-24 months | 77 | ~17% (13) | ~19% (21) | ~64% (49) |

| Total | 108 | ~12% (13) | ~19% (21) | ~69% (74) |

What is a proven method to overcome inhibition in stool samples?

The addition of Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) to the reaction mixture is a well-documented and effective method for relieving inhibition in stool samples and other complex matrices.

- Protocol from Stool Sample Study: In the study of infant stool samples, the addition of BSA directly to the cDNA and PCR reactions completely eliminated the inhibitory effect, making all previously inhibited samples positive [12].

- Mechanism of Action: BSA acts by binding to a variety of inhibitory compounds present in samples, such as phenolics, humic acids, and tannins. It can also serve as a competitive target for proteinases that might degrade the DNA polymerase [23].

- Validation in High-Throughput Settings: The efficacy of BSA is not limited to stool. A recent large-scale study on buccal swab samples, which can also suffer from sporadic inhibition, found that incorporating BSA into the PCR mix significantly improved robustness, lowering the assay failure rate to 0.1% across 1,000,000 samples [24].

Other additives have also been evaluated for relieving inhibition in complex environmental samples like wastewater, which shares some inhibitory components with stool. These include T4 gene 32 protein (gp32), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and non-ionic detergents like Tween-20 [17] [23].

How do PCR inhibitors actually work?

PCR inhibitors disrupt the amplification process through several distinct mechanisms. The following diagram illustrates the primary points of interference within the PCR workflow.

What are the key reagent solutions for tackling inhibition?

A combination of robust reagents and specific additives is crucial for successful PCR in the presence of inhibitors. The following table lists essential solutions for your toolkit.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Overcoming PCR Inhibition

| Solution | Function / Mechanism | Example Context |

|---|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Binds to a wide range of inhibitors (e.g., phenolics, humic acids); acts as a competitive target for proteinases [12] [23]. | Stool samples [12], buccal swabs [24]. |

| T4 Gene 32 Protein (gp32) | A single-stranded DNA-binding protein that stabilizes DNA and can also relieve inhibition, potentially by protecting the polymerase [17] [23]. | Wastewater samples [17]. |

| Inhibitor-Tolerant Polymerase | Specially engineered or selected DNA polymerases with higher affinity for DNA and inherent resistance to common inhibitors [23] [21]. | Blood, soil, and plant-derived samples [21]. |

| Organic Solvents (DMSO, Formamide) | Destabilize DNA secondary structures, lower melting temperature, and can enhance specificity, helping in complex templates [17] [23]. | Wastewater, GC-rich templates [17]. |

| Non-Ionic Detergents (Tween-20) | Stimulate Taq DNA polymerase activity and can counteract inhibitory substances [17] [23]. | Fecal samples, wastewater [17]. |

Optimized Workflows: From Sample Collection to Amplification

Best Practices in Sample Collection and Storage to Preserve Nucleic Acid Integrity

This technical support guide provides detailed protocols and troubleshooting advice to help researchers overcome challenges in nucleic acid preservation, specifically within the context of preventing PCR inhibition in stool sample research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the most critical factor to prevent RNA degradation during sample collection? The most critical step is immediate sample stabilization to halt the activity of ubiquitous and stable RNase enzymes. This can be achieved by flash-freezing samples in liquid nitrogen or using commercial stabilization reagents immediately upon collection. For RNA, the single-stranded structure and the presence of a 2'-hydroxyl group make it particularly susceptible to degradation by RNases and hydrolysis, especially at elevated temperatures or humidity [25].

2. How can I prevent the introduction of RNase contamination during extraction? Establishing a dedicated RNase-free workspace is essential. Key practices include:

- Regularly decontaminating work surfaces with RNase-inactivating reagents.

- Using certified RNase-free, disposable plasticware and pipette tips.

- Wearing gloves and replacing them frequently.

- Using nuclease-free water and reagents [25].

3. What are the best long-term storage conditions for purified nucleic acids? For long-term storage, purified DNA and RNA should be stored at -70 °C to -80 °C. It is crucial to divide the nucleic acids into small single-use aliquots to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles, which cause degradation. DNA can be stored in TE buffer (Tris-EDTA), where the EDTA chelates metal ions to inhibit nucleases. For even greater long-term stability, especially in the face of equipment failure, storage in the vapor phase of liquid nitrogen (below -150 °C) is optimal [25] [26] [27].

4. My PCR from stool samples shows no product or poor yield. What could be wrong? This is a common symptom of PCR inhibition or poor nucleic acid integrity. Please refer to the troubleshooting table below for a systematic analysis.

Troubleshooting Guide: PCR Failure in Stool Sample Research

Table 1: Common issues, causes, and solutions for PCR amplification from stool samples.

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No Product or Weak Yield | Poor DNA/RNA integrity due to degradation during collection/storage. | Flash-freeze or chemically stabilize (e.g., with lysis buffer) samples immediately upon collection [25] [28]. Avoid freeze-thaw cycles. |

| Presence of PCR inhibitors (e.g., complex polysaccharides, bile salts, phenolic compounds) from stool. | Re-purify the DNA. Use ethanol precipitation or a dedicated cleanup kit to remove inhibitors [7] [29]. | |

| Insufficient DNA polymerase activity due to inhibitors. | Use DNA polymerases known for high processivity and tolerance to inhibitors [7]. Increase the amount of polymerase slightly. | |

| Suboptimal primer design or concentration. | Verify primer specificity and recalculate Tm. Optimize primer concentration, typically between 0.1–1 µM [7] [29]. | |

| Multiple or Non-Specific Bands | Primer annealing temperature is too low. | Increase the annealing temperature in 1-2°C increments. Use a hot-start polymerase to prevent activity at room temperature [29]. |

| Excess Mg2+ concentration. | Optimize the Mg2+ concentration in the PCR reaction, testing in 0.2–1 mM increments [29]. | |

| Contamination with exogenous DNA. | Use dedicated pipettes and workspace. Use filter tips and set up reactions in a UV-treated hood [25] [29]. |

Experimental Protocol: Preserving Rumen Microbiome Samples for DNA Analysis

The following protocol, adapted from a high-throughput study on rumen samples, provides a robust method for preserving complex microbial communities (like those in stool) for subsequent DNA extraction and PCR analysis [28].

Objective: To preserve microbial community DNA in complex biological samples at the point of collection, preventing degradation and changes in community profile.

Materials:

- TNx2 Lysis Buffer: 800 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris HCl, 1.2% SDS, 200 mM EDTA, pH 8.0.

- GHx2 Lysis Buffer: 2 M Guanidine Hydrochloride (GuHCl), 200 mM Tris HCl, 6% Tween-20, 1% Triton X-100, 40 mM EDTA, pH 8.0.

- 100% Ethanol.

- RNase-free, screw-cap vials.

- Personal protective equipment (gloves, lab coat).

Procedure:

- Preparation: Dispense preservative solutions (TNx2, GHx2, or Ethanol) into labeled, sterile screw-cap vials prior to sample collection.

- Sample Collection: Collect the stool (or rumen) sample using a standardized procedure.

- Preservation: Immediately add the sample to the preservative vial at the specified ratio:

- For TNx2 and GHx2, use a 1:1 ratio of sample to preservative.

- For Ethanol, use a 1:2 ratio of sample to preservative [28].

- Mixing: Secure the cap and mix the vial thoroughly by inversion to ensure the sample is fully immersed and homogenous with the preservative.

- Storage: Store the preserved samples at room temperature for transport. For long-term storage, keep at -80°C. The lysis buffers (TNx2, GHx2) will lyse cells and inactivate nucleases upon contact, stabilizing the microbial DNA profile.

Workflow: Sample Collection to PCR

The diagram below illustrates the critical steps from sample collection to successful PCR amplification, highlighting key decision points to preserve nucleic acid integrity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Nucleic Acid Preservation

Table 2: Key reagents and materials for effective sample preservation and handling.

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lysis Buffers (TNx2/GHx2) | Cell lysis and nuclease inactivation at point of collection. Contains surfactants (SDS) and chaotropic salts (GuHCl) [28]. | Ideal for high-throughput field sampling. Compatible with downstream DNA extraction kits. |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | Chemically stabilizes RNA immediately, halting degradation. | Crucial for gene expression studies. Products like RNAprotect are sample-specific [25]. |

| Silica Gel | Rapidly desiccates tissue samples by absorbing moisture. | A low-cost method for preserving DNA in plant and tissue samples at room temperature [27]. |

| TE Buffer (Tris-EDTA) | Long-term storage buffer for purified DNA. Tris maintains pH, EDTA chelates divalent cations to inhibit nucleases [25] [26]. | Standard storage buffer for DNA aliquots at -20°C or -80°C. |

| Guanidine Isothiocyanate | Powerful chaotropic salt that denatures proteins and RNases. | A key component in many commercial RNA/DNA extraction kits [25]. |

| EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) | Chelates divalent cations (e.g., Mg2+), which are co-factors for many nucleases [25]. | Added to storage buffers and lysis solutions to prevent metal-catalyzed degradation. |

Comparative Analysis of DNA/RNA Extraction Kits for Complex Stool Matrices

Molecular analysis of stool samples is fundamental to advancements in genomics, microbiology, and drug development. However, the complex composition of stool, which includes PCR inhibitors like bile salts, complex polysaccharides, and humic substances, poses a significant challenge to obtaining high-quality nucleic acids. This technical support center is designed to help researchers overcome these hurdles by providing evidence-based troubleshooting guides, detailed protocols, and curated reagent solutions to ensure reliable PCR amplification from complex stool matrices.

FAQs: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

1. Why is my PCR failing even after successful DNA extraction from stool?

PCR failure after extraction is frequently caused by co-purified inhibitors. Stool samples contain organic (e.g., bile pigments, urea, complex polysaccharides) and inorganic (e.g., calcium) compounds that can inhibit DNA polymerases [30]. To resolve this:

- Dilute the Template: A 10- to 100-fold dilution of your DNA template can often reduce inhibitor concentration to a level that no longer affects the reaction [30] [7].

- Re-purify the DNA: Use a DNA clean-up kit or perform ethanol precipitation to remove contaminants [31] [7].

- Use Inhibitor-Tolerant Enzymes: Select polymerases specifically formulated for high tolerance to common inhibitors found in stool, soil, and plants [30] [7].

2. My RNA extracts from stool show low yield and purity. What steps can I take to improve this?

RNA isolation from stool is challenging due to high RNase activity and inhibitory substances.

- Stabilize Immediately: Upon collection, solubilize samples in a dedicated lysis buffer (e.g., TRIzol) or a stabilization reagent (e.g., DNA/RNA Shield) that inactivates RNases. This is critical for preserving RNA integrity [32].

- Ensure Complete Lysis: Pair your lysis buffer with a mechanical lysis step, such as bead beating, to efficiently break down tough microbial cell walls and stool particulates. Incomplete lysis leads to low yield and can cause column clogging [32].

- Eliminate DNA Contamination: Use RNA extraction kits that include an on-column DNase I treatment step. This removes DNA carryover without requiring additional clean-up steps, ensuring your RNA is suitable for sensitive downstream applications like RT-qPCR [32].

3. How does the choice of DNA extraction method affect the detection of diverse intestinal parasites?

Different parasites present different lysis challenges, from the fragile cells of protozoa to the tough eggshells of helminths. The DNA extraction method must be robust enough to handle this variety. A 2022 study compared four methods for extracting DNA from human stool samples infected with various parasites [33]. The key findings are summarized below:

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Extraction Methods for Parasite Detection via PCR

| Extraction Method | Description | Average DNA Yield (ng/μL) | PCR Detection Rate | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenol-Chloroform (P) | Conventional chemical lysis and extraction. | ~200 | 8.2% | Low detection rate; only detected S. stercoralis. |

| Phenol-Chloroform + Bead Beating (PB) | Chemical lysis with mechanical disruption. | ~200 | 45.9% | Significantly improved detection over method P. |

| QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Q) | Silica-column based kit. | ~50 | 47.1% | Better detection than P, but lower yield. |

| QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QB) | Silica-column kit with bead-beating step. | ~50 | 61.2% | Highest detection rate; effective for all parasites tested. |

The study concluded that the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QB), which incorporates a bead-beating step, was the most effective method for the comprehensive PCR-based diagnosis and monitoring of intestinal parasites [33].

4. For a large-scale ecosystem study requiring DNA from soil, invertebrates, and feces, which single DNA extraction kit is most suitable?

A 2024 study aimed to identify a single kit suitable for diverse sample types from a terrestrial ecosystem [34]. After evaluating five commercial kits across bulk soil, rhizosphere soil, invertebrate, and mammalian feces samples, the NucleoSpin Soil kit (MNS) was associated with the highest alpha diversity estimates and provided the highest contribution to overall sample diversity when compared to computationally assembled reference communities. The study recommended this kit for any large-scale microbiota study of terrestrial ecosystems where multiple sample matrices are processed [34].

Experimental Protocols for Key Cited Studies

Protocol 1: Evaluating DNA Extraction Kits for Wildlife Feces

This protocol is adapted from a 2024 comparative study of extraction kits for wildlife feces collected from the environment [35] [36].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Collect wildlife fecal samples and store them appropriately (e.g., frozen or in stabilization buffer).

- Dry homogenize the samples with physical mixing to create a consistent starting material.

- Split the homogenized sample into 100 mg (± 5 mg) subsamples for parallel extraction with different kits.

2. Nucleic Acid Extraction:

- Select the kits to be compared. The cited study evaluated four DNA kits, two DNA/RNA co-extraction kits, and one RNA-only kit.

- Standardize Bead-Beating: Perform a standardized bead-beating step across all methods to ensure consistent mechanical lysis.

- Follow the manufacturer's recommended protocol for each kit for all subsequent steps.

3. Extraction Success Metrics:

- Concentration: Quantify nucleic acids using a spectrophotometer or fluorometer.

- Integrity: Analyze extracts using a system like Agilent TapeStation to determine the DNA Integrity Number (DIN) or RNA Integrity Number (RIN).

- PCR Inhibition Test: Use a qPCR assay spiked with a synthetic internal control. Compare the Ct values of reactions using sample elutions to a reaction with nuclease-free water. A significant delay in Ct indicates the presence of PCR inhibitors [35].

Protocol 2: Efficient DNA Extraction from Intestinal Parasites in Human Stool

This detailed protocol is based on the 2022 study that identified the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QB) as the most effective method [33].

1. Sample Pretreatment:

- Take 200 mg of stool sample preserved in 70% ethanol.

- Wash the sample three times with sterile distilled water to remove ethanol and other soluble inhibitors.

- Aliquot the washed sample into a 2 mL microcentrifuge tube.

2. DNA Extraction using the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QB):

- Follow the manufacturer's instructions precisely. The key steps are visualized below:

3. Downstream Analysis:

- Quantification and Purity Check: Measure DNA concentration and purity using a spectrophotometer (e.g., A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios).

- PCR Amplification: Perform PCR with primers specific to your target parasites (e.g., Blastocystis sp., Ascaris lumbricoides, Strongyloides stercoralis).

- Inhibitor Check via Spike Test: For samples that are PCR-negative, add a known amount of a control plasmid to the extracted DNA and re-run PCR. If the plasmid fails to amplify, it confirms the presence of residual PCR inhibitors [33].

Essential Workflow for Reliable Stool NA Extraction

The following diagram synthesizes the critical steps, from sample collection to downstream analysis, for obtaining reliable nucleic acids from complex stool samples, integrating best practices from the cited literature.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for Nucleic Acid Extraction from Stool

| Product Name / Category | Primary Function | Key Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QB) [33] | DNA extraction from stool and soil. | Highly effective for lysing diverse parasites (helminths and protozoa); includes bead-beating for mechanical lysis. |

| NucleoSpin Soil Kit (MNS) [34] | DNA extraction from soil and environmental samples. | Recommended for large-scale ecosystem studies involving multiple sample types (soil, feces, invertebrates). |

| ZymoBIOMICS DNA/RNA Miniprep Kits [32] | Co-extraction of DNA and RNA from complex samples. | Designed for feces, soil, and biofilm; includes on-column DNase treatment for RNA. |

| DNA/RNA Shield [32] | Sample stabilization reagent. | Inactivates nucleases at collection, allowing ambient transport and storage; preserves nucleic acid integrity. |

| Inhibitor-Tolerant DNA Polymerases [30] [7] | PCR amplification from difficult samples. | Essential for amplifying DNA extracts that may contain residual inhibitors from stool. |

| Silica Magnetic Beads [37] | Solid-phase nucleic acid purification. | Enables rapid, automatable protocols; performance depends on binding/elution pH and mixing mode. |

The Role of Bead-Beating and Mechanical Lysis in Efficient Cell Disruption

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Problems and Solutions in Mechanical Cell Lysis

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Lysis of Resistant Microbes | Insufficient disruption energy or time; inappropriate bead size [38] [39]. | Increase bead-beating time in cycles (e.g., 5 cycles of 1 min with 5 min rest) [40]. Use smaller (e.g., 100-μm) beads for tough Gram-positive bacteria [38]. Validate protocol with a standardized microbial community standard [40]. |

| PCR Inhibition | Co-extraction of inhibitors (e.g., humic acids, bile salts, collagen) from sample matrix [17] [19]. | Use an inhibitor removal kit (e.g., PowerClean DNA Clean-Up Kit or DNA IQ System) [19]. Add PCR enhancers like BSA (0.1-0.5 μg/μL) or TWEEN-20 (0.1-1%) to the reaction [17]. Perform a 10-fold dilution of the DNA extract to dilute inhibitors [17]. |

| Low DNA Yield | Inefficient lysis; excessive heat or shear forces degrading DNA [40] [39]. | Ensure the correct bead-to-sample ratio and use the recommended bead material [40]. Use cooling intervals during bead-beating to prevent heat buildup [40]. Confirm lysis efficiency using a quantitative method like acid/HPLC [41]. |

| Biased Microbiome Profiles | Over-representation of easy-to-lyse microbes (e.g., Gram-negatives) due to non-uniform lysis [40] [39]. | Adopt a stochastic mechanical lysis method (bead-beating) over purely chemical or enzymatic methods [40]. Use a validated, high-intensity bead-beating protocol that is sufficient for tough spores and fungi [40] [39]. |

Optimizing Bead-Beating Protocols for Different Sample Types

| Sample Type | Challenge | Recommended Bead-Beating Parameters | Supported by |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stool Samples | Complex matrix with high levels of PCR inhibitors and diverse microbial community [17] [42]. | Intensity: High (e.g., 40 min total on a Vortex Genie with adapter) [40].Beads: Zirconia/Silica beads.Post-Processing: Use of inhibitor removal columns or enhancers like BSA is critical [17] [19]. | [17] [40] [42] |

| Gram-Positive Bacteria & Spores | Thick, tough cell walls resistant to chemical lysis [38] [39]. | Intensity: High. Protocols for Bacillus spores and Mycobacterium require several minutes of beating [38].Bead Size: 100-μm diameter beads are most effective [38]. | [38] [39] |

| Fungi | Highly resistant cell walls, often leading to severe underrepresentation [40] [39]. | Intensity: Very High. Fungal lysis requires more energy than Gram-negative bacteria [39].Protocol: Consider protocols with multiple cycles of beating and rest (e.g., 5 min on, 5 min rest, repeated 4x) [40]. | [40] [39] |

| General Microbiome Profiling | Avoiding bias between easy-to-lyse and tough-to-lyse organisms [40]. | Intensity: Use benchmarked protocols validated with a microbial community standard [40].Method: Bead-beating is the gold standard for stochastic, unbiased lysis [40]. | [40] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Why is mechanical lysis like bead-beating necessary for stool sample analysis?

Stool samples contain a complex mix of microorganisms, including tough-to-lyse Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., Clostridium spp.) and fungal elements. Purely chemical or enzymatic lysis methods are often insufficient for these resistant cells, leading to a biased microbial profile that over-represents easy-to-lyse Gram-negative bacteria [40] [39]. Bead-beating provides a stochastic mechanical force that ensures more uniform disruption across diverse cell types, which is critical for accurate microbiome analysis [40]. Furthermore, efficient lysis is the first step in liberating enough pure DNA for subsequent PCR, helping to overcome challenges related to PCR inhibition from the complex stool matrix [17].

How does inefficient lysis contribute to PCR inhibition?

Inefficient lysis is a dual-faceted problem. First, it fails to release sufficient nucleic acids from resistant cells, directly reducing the available template for PCR [39] [41]. Second, and perhaps less obviously, it can lead to an over-reliance on harsher chemical treatments or larger sample volumes to compensate for low yield. This increases the probability of co-purifying potent PCR inhibitors present in the sample matrix, such as humic acids, bile salts, and complex polysaccharides [17] [19]. Therefore, efficient and robust mechanical lysis is a key first step in minimizing downstream inhibition.

My PCR results are inconsistent even after bead-beating. What could be wrong?

Inconsistencies can arise from several factors related to the lysis process itself or subsequent steps:

- Non-Uniform Lysis: If the bead-beating protocol is not optimized or validated, it may lyse cells inconsistently across samples, leading to variable DNA template quantities [40] [39].

- Inhibitor Carryover: Bead-beating can liberate intracellular components and release additional inhibitors from the sample matrix. If not properly removed post-lysis, these can cause intermittent PCR failure [17] [19].

- Protocol Variability: Small changes, such as the number and weight of tubes in the bead beater, can significantly impact lysis efficiency and introduce bias [40]. Always follow validated protocols precisely.

Are there methods to quantitatively measure lysis efficiency?

Yes, traditional methods like cell counting or measuring total DNA yield are indirect and can be inaccurate [41]. A more direct method, the acid/HPLC technique, has been developed to precisely assess disruption efficiency. This method involves treating a portion of the bacterial sample with mild acid and alkali to depurinate DNA and hydrolyze RNA. The released purines (adenine and guanine) are then quantified using HPLC. By comparing the amount of DNA released by the lysis method to the total DNA in the sample determined by acid/HPLC, the true efficiency of the DNA extraction procedure can be calculated [41].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Kits

| Item | Function in Lysis and Inhibition Control | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Zirconia/Silica Beads (100μm) | Optimal for disrupting tough cell walls via high-shear forces during bead-beating [38]. | Acid-washed beads are recommended to minimize contaminating DNA [38]. |

| Inhibitor Removal Kits | Specifically designed to remove common PCR inhibitors (humic acids, collagen, bile salts, etc.) from complex sample extracts [19]. | PowerClean DNA Clean-Up Kit and DNA IQ System have been shown effective for forensic and environmental samples [19]. |

| PCR Enhancers | Compounds added to the PCR reaction to counteract the effects of lingering inhibitors by stabilizing the polymerase or binding inhibitors [17]. | BSA (0.1-0.5 μg/μL): Binds inhibitors [17].TWEEN-20 (0.1-1%): Counteracts inhibitors of Taq polymerase [17].DMSO/Formamide: Lower DNA melting temperature to aid amplification [17]. |

| Standardized Microbial Community | A defined mix of easy-to-lyse and tough-to-lyse microbes used to benchmark and validate lysis protocols for bias [40]. | The ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard is used to develop validated, unbiased bead-beating protocols [40]. |

| Lysis-Resistant Surrogates | Internal control organisms (e.g., B. subtilis spores, M. bovis BCG) added to samples to monitor lysis efficiency in each run [38]. | Helps distinguish between lysis failure and PCR inhibition as the cause of a negative result [38]. |

Experimental Workflows and Visual Guides

Diagram: Decision Pathway for Lysis and Inhibition Troubleshooting

Diagram: Integrated Workflow for Unbiased Analysis from Stool Samples

Selecting Robust Polymerases and Master Mixes for Inhibitor-Tolerant PCR

FAQ: Understanding PCR Inhibition in Complex Samples

What are the most common PCR inhibitors found in complex samples like stool? In complex samples, PCR inhibitors originate from various sources. Biological samples like blood contain hemoglobin and immunoglobulin G, while plant and food substances contain polysaccharides, polyphenols, and tannins. Environmental samples like soil and wastewater often contain humic and fulvic acids. Laboratory reagents like SDS, EDTA, and ethanol can also be inhibitory if not completely removed [21]. These compounds interfere with PCR through multiple mechanisms: directly inhibiting DNA polymerase activity, degrading or sequestering nucleic acid templates, or chelating essential co-factors like magnesium ions [4] [17].

How can I detect PCR inhibition in my qPCR results? In quantitative PCR, inhibition manifests through several key indicators: delayed quantification cycle (Cq) values across all samples and controls, poor amplification efficiency (outside the ideal 90-110% range), and abnormal amplification curves that may appear flattened or fail to cross the detection threshold [21]. The use of an internal PCR control is particularly valuable for differentiating between true inhibition and simply low target concentration. If the IPC shows delayed Cq values, inhibition is likely present in the reaction [21].

Why are some DNA polymerases more resistant to inhibitors than others? Different DNA polymerases exhibit varying tolerance to PCR inhibitors due to their structural differences and origins [43]. Research has demonstrated that blending DNA polymerases from different sources can create a synergistic effect that significantly enhances inhibitor resistance beyond what any single polymerase can achieve [43]. Additionally, engineered polymerase variants developed through directed evolution approaches contain specific mutations that stabilize the enzyme's structure or enhance nucleotide binding, making them less susceptible to inhibitor interference [44] [45].

Troubleshooting Guide: Overcoming PCR Inhibition

Problem: Complete PCR Failure or Significantly Reduced Yield with Stool Samples

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Co-purification of potent PCR inhibitors from stool matrix during DNA extraction.

Cause: Insufficient inhibitor tolerance of the DNA polymerase.

- Solution: Select an inhibitor-resistant DNA polymerase blend or engineered variant. Research shows that replacing standard Taq polymerase with specialized blends can increase complete DNA profiles from 82 to 105 out of 114 forensic samples [43]. Novel variants like Taq C-66 (E818V) and Klentaq1 H101 (K738R) show superior resistance to diverse inhibitors including those from plant and food sources [45].

Cause: Suboptimal reaction composition lacking necessary enhancers.

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Sample Replicates

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Incomplete removal of inhibitors during extraction leading to variable inhibitor carryover.

Cause: Non-homogeneous master mix components.

- Solution: Mix all reagent stocks thoroughly before use to eliminate density gradients that may have formed during storage. Prepare master mixes in sufficient volume to accommodate all replicates plus excess to ensure consistency [7].

Comparative Performance Data of Inhibitor-Tolerant PCR Solutions

Table 1: Performance Comparison of DNA Polymerases and Blends in Inhibitory Conditions

| Polymerase Type | Key Features | Inhibitor Resistance | Reported Improvement | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ExTaq/PicoMaxx Blend | 1:1 blend of two polymerases | Forensic samples (blood, saliva) | Increased complete profiles from 82 to 105/114 samples; Enabled profiling of 21/25 inhibitory blood stains vs. 2/25 with standard polymerase | [43] |

| Engineered Taq C-66 | E818V point mutation | Blood, humic acid, plant extracts, chocolate | Superior resistance to diverse inhibitors compared to wild-type; Structural mapping suggests enhanced nucleotide binding | [44] [45] |

| Engineered Klentaq1 H101 | K738R point mutation | Black pepper, plant tissues, blood | Intrinsic enzymatic tolerance persisting after purification; Stabilized polymerase-DNA complex | [45] |

| Bst DNA Polymerase | Strand displacement activity, isothermal amplification | Point-of-care testing applications | Robust performance in LAMP applications; Engineering efforts focus on enhancing specificity and inhibitor resistance | [47] |

Table 2: Effectiveness of PCR Enhancers Against Various Inhibitors

| Enhancer | Recommended Concentration | Mechanism of Action | Effective Against | Study Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | 0.1-0.5 μg/μL | Binds inhibitors, stabilizes enzyme | Humic acids, polyphenols, hematin | Significant improvement in detection of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater samples [17] |

| T4 Gene 32 Protein (gp32) | 0.1-0.5 μM | Binds single-stranded DNA, prevents secondary structure | Complex sample matrices | Enhanced amplification efficiency in inhibitory wastewater samples [17] |

| Tween-20 | 0.1-1% | Counteracts inhibitory effects on Taq | Fecal samples, complex matrices | Effective relief of inhibition in environmental samples [17] |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | 1-5% | Lowers DNA melting temperature | GC-rich templates, secondary structures | Moderate improvement in wastewater viral detection [17] |

Experimental Protocols for Inhibitor-Tolerant PCR

Protocol 1: Live Culture PCR Screening for Inhibitor-Resistant Polymerases

This innovative protocol enables rapid screening of polymerase variants for inhibitor resistance without requiring enzyme purification [45].

Materials:

- Randomly mutagenized Taq or Klentaq1 libraries in expression vectors

- Host bacterial cells (E. coli or X7029)

- PCR reagents: buffer, dNTPs, SYBR Green, primers

- PCR inhibitors for screening (e.g., chocolate, black pepper, blood extracts)

- 96-well PCR plates and thermal cycler with real-time detection

Procedure:

- Transform host bacterial cells with mutagenized polymerase libraries

- Plate transformed cells to obtain single colonies and incubate in 96-well plates containing Amp+ media with 1 mM IPTG for 12-16 hours at 37°C

- Transfer 5 μL of culture from each well to a replica PCR plate containing master mix with rDNA primers, SYBR Green, and challenging inhibitor

- Perform real-time PCR with cycling conditions: 94°C for 10 min, then 40-45 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 54°C for 40 s, and 70°C for 2 min

- Identify positive clones showing amplification in the presence of inhibitors that inhibit control polymerases

- Sequence ORFs of selected mutants and validate phenotype after purification

Diagram 1: Workflow for screening inhibitor-resistant polymerase variants using live culture PCR.

Protocol 2: Systematic Evaluation of PCR Enhancers for Inhibitory Samples

This protocol provides a standardized approach to evaluate different PCR enhancers for challenging sample types like stool extracts.

Materials:

- Inhibitory DNA samples (e.g., extracted from stool)

- Control DNA (inhibitor-free)

- Standard DNA polymerase

- PCR enhancers: BSA, gp32, DMSO, formamide, Tween-20, glycerol

- qPCR reagents: buffer, dNTPs, primers, probes

Procedure:

- Prepare a base master mix containing all standard PCR components except enhancers

- Aliquot the master mix and add different enhancers at various concentrations:

- BSA: 0.1, 0.25, 0.5 μg/μL

- gp32: 0.1, 0.25, 0.5 μM

- DMSO: 1%, 3%, 5%

- Tween-20: 0.1%, 0.5%, 1%

- Glycerol: 1%, 3%, 5%

- Include a negative control with no enhancer and a positive control with inhibitor-free template

- Add the inhibitory DNA template to all reactions

- Run qPCR with appropriate cycling conditions

- Compare Cq values, amplification efficiency, and curve shape across conditions

- Select the enhancer and concentration providing the best performance with minimal background

Strategic Approach to PCR Inhibition Challenges

Diagram 2: Strategic approach combining sample preparation, polymerase selection, and reaction enhancement to overcome PCR inhibition.

Research Reagent Solutions for Inhibitor-Tolerant PCR

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Inhibitor-Tolerant PCR

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor-Resistant Polymerases | GoTaq Endure qPCR Master Mix, ExTaq/PicoMaxx blend, Engineered Taq variants (C-66, H101) | Core amplification enzyme with enhanced tolerance to inhibitors | Select based on specific inhibitor profile; blends often outperform single enzymes [43] [21] [45] |

| PCR Enhancers | BSA (0.1-0.5 μg/μL), T4 gp32 (0.1-0.5 μM), Tween-20 (0.1-1%) | Bind inhibitors or stabilize reaction components | Optimize concentration for specific sample type; BSA particularly effective for humic acids [17] |

| Alternative Amplification Methods | Bst DNA polymerase for LAMP, Digital PCR (ddPCR) | Bypass inhibition through isothermal amplification or partitioning | ddPCR shows higher tolerance to inhibitors due to reaction partitioning [47] [17] |

| Specialized Extraction Kits | Inhibitor removal columns, bead-based homogenization systems | Remove co-purified inhibitors during nucleic acid extraction | Systems like Bead Ruptor Elite provide controlled homogenization while minimizing inhibitor release [46] |

In the molecular analysis of complex sample types like stool, Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) inhibition presents a significant challenge, often leading to false-negative results and inaccurate data. Inhibitory substances co-extracted with nucleic acids can disrupt enzyme activity and impede amplification. Within this context, designing assays with short amplicon length has emerged as a critical and powerful strategy for overcoming these limitations, ensuring sensitive and reliable detection, particularly when targeting degraded DNA.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Why is amplicon length so critical for PCR success in inhibitory samples?

The length of the DNA fragment you are trying to amplify (the amplicon) is directly related to the probability of the polymerase enzyme successfully copying the entire sequence. In the presence of inhibitors, which can reduce enzyme processivity, shorter amplicons have a much higher chance of being fully amplified.

- Mechanism of Inhibition: Inhibitors can bind to the DNA template, sterically hindering polymerase access, or they can partially disable the enzyme itself, reducing its efficiency. These effects become more pronounced with longer DNA fragments.

- Experimental Evidence: Research has conclusively shown that amplicon size is a dominating factor in susceptibility to inhibition. One study demonstrated that as amplicon size increases, amplification efficiency decreases in the presence of inhibitors. The effect of the DNA sequence itself (e.g., GC content) is less significant than the length of the amplicon [48].

How much does amplicon length impact sensitivity in real-world samples like stool?

The impact can be dramatic. A 2025 study on H. pylori detection in stool samples provides a compelling example. Researchers compared a long amplicon (454 bp) to a short amplicon (148 bp) using nested PCR on the same patient samples.

Table 1: Impact of Amplicon Length on Detection Sensitivity in Stool Samples

| Patient Group | Positive with Long Amplicon (454 bp) | Positive with Short Amplicon (148 bp) |

|---|---|---|

| Symptomatic Patients (n=208) | 6.25% | 51.0% |

| Asymptomatic Volunteers (n=100) | 22.0% | 66.6% |

The data shows that the short amplicon was significantly more sensitive, identifying over 8 times more positive samples in the symptomatic group. The study concluded that stool often contains short fragments of degraded H. pylori DNA, making shorter amplicons essential for reliable detection [49].

What is the optimal amplicon length for challenging samples?

While the ideal length can depend on the specific application and sample type, a general guideline is to design amplicons to be as short as possible while still encompassing the unique target sequence. For qPCR assays, many manufacturers and design guides recommend keeping amplicons below 150 base pairs to achieve optimal PCR efficiency, especially when expecting inhibitors or degraded DNA [50]. For heavily degraded samples, such as forensic evidence or ancient DNA, amplicons of 100 bp or less are often targeted.

Besides length, what other assay design factors help overcome inhibition?

A robust assay design incorporates multiple strategies:

- Internal Amplification Controls (IAC): An IAC is a non-target DNA sequence co-amplified in the same reaction tube. It is critical for distinguishing true target-negative results from false negatives caused by PCR inhibition. If the IAC fails to amplify, the test is invalid due to inhibition, regardless of the target signal [50].

- PCR Enhancers: Reagents like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) can bind to inhibitors such as humic acids, preventing them from interfering with the DNA polymerase. Other enhancers include TWEEN-20, DMSO, and glycerol, which can help counteract inhibitory effects [17] [21].

- Inhibitor-Tolerant Master Mixes: Using specialized PCR master mixes formulated with inhibitor-resistant polymerases and buffer components can significantly improve robustness in the presence of common inhibitors found in stool, soil, or blood [21].

Experimental Protocol: Designing & Validating a Short-Amplicon Assay

This protocol outlines the key steps for designing and testing a PCR assay optimized for inhibitory samples like stool.

Step 1: In-Silico Primer Design and Amplicon Optimization

Objective: To design primers that generate a short, specific amplicon. Methodology:

- Select Target Region: Identify a unique, conserved region within your gene of interest.

- Use Design Tools: Utilize online primer design tools (e.g., IDT's PrimerQuest Tool, QIAGEN's GeneGlobe). These tools incorporate bioinformatic calculations to manage factors like cross-reactivity and secondary structure [51] [52].

- Set Amplicon Parameters: In the design software, set the desired amplicon size range. For challenging samples, specify a narrow range of 80-150 bp.

- Check Specificity: Always perform an in-silico check for primer specificity using a tool like NCBI BLAST to ensure they do not bind to non-target sequences [51].

Step 2: Wet-Lab Validation with Inhibitor Spike-In

Objective: To experimentally verify that the short-amplicon assay performs well in the presence of inhibitors. Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Extract DNA from your sample type (e.g., stool using a kit like QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit) [49].

- Inhibition Model: Spike a known quantity of your target DNA (e.g., from a cultured organism) into the extracted nucleic acids. Create a dilution series of this sample to test assay sensitivity.

- Compare Amplicons: Test your new short-amplicon assay alongside any existing longer-amplicon assays on the same diluted, inhibitor-containing samples.

- Quantify Performance: Compare the Cycle quantification (Cq) values and endpoint detection rates between the short and long amplicon assays. The short amplicon should demonstrate lower Cq values and reliable detection at higher dilutions (lower target concentrations) [49] [48].

The following workflow diagrams this optimization and validation process:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Developing Inhibition-Resistant PCR Assays

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor-Tolerant Master Mix (e.g., GoTaq Endure) | Contains specialized polymerases and buffers for robust amplification in complex matrices like stool. | Designed for consistent performance in the presence of common inhibitors [21]. |

| PCR Enhancers (BSA, gp32, TWEEN-20) | Additives that bind to or neutralize inhibitory substances co-extracted from samples. | Requires optimization of concentration; effectiveness can vary by inhibitor type [17]. |

| Internal Amplification Control (IAC) | Non-target DNA sequence to distinguish true negatives from PCR inhibition. | Must be carefully designed to co-amplify without competing excessively with the primary target [50]. |

| Primer Design Software (e.g., IDT PrimerQuest) | Bioinformatics tool for designing primers with optimized parameters for short, specific amplicons. | Allows customization of ~45 parameters including amplicon size and Tm [51]. |

| Predesigned Assay Databases (e.g., QIAGEN GeneGlobe) | Repository of pre-optimized qPCR/dPCR assays, many with short amplicons. | Saves development time; offers wet-lab validated designs for many human, mouse, and rat targets [52]. |

Overcoming PCR inhibition in complex samples is a multi-faceted challenge, but the strategic design of short amplicons is one of the most effective approaches. By reducing the physical distance the polymerase must travel, shorter targets significantly increase the likelihood of successful amplification when inhibitors are present or when the template DNA is degraded. Coupling short amplicon design with the use of internal controls, PCR enhancers, and robust master mixes provides a comprehensive solution for generating reliable, reproducible, and sensitive molecular data from the most challenging sample types.

Practical Strategies for Troubleshooting and Assay Optimization

In the context of a broader thesis on overcoming PCR inhibition in stool sample research, the accurate detection and management of systematic inhibition is paramount. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) inhibition remains a significant challenge in molecular diagnostics and research, particularly when analyzing complex sample matrices like stool. Inhibitors present in these samples can lead to false-negative results, reduced sensitivity, and compromised data integrity. This technical support guide provides researchers with comprehensive strategies for detecting PCR inhibition through the implementation of internal controls and standard curves, enabling more reliable and reproducible experimental outcomes in stool-based research.

FAQs on PCR Inhibition Detection and Management

Stool samples contain numerous substances that can inhibit PCR amplification, including:

- Complex polysaccharides and bile salts that co-purify with nucleic acids [53]

- Phenolic compounds from dietary sources or bacterial metabolism [54]

- Degraded bacterial cell components from the gut microbiome [54]

- Heavy metals and other environmental contaminants [54]

- Hemoglobin derivatives and immunoglobulin G in certain pathological conditions [54]

The concentration of these inhibitors can vary significantly based on age, diet, health status, and medication use, with studies noting inhibitor presence ranging from 0% in newborn stools to 17% in samples from children aged 6-24 months [54].

How can I design an effective internal control for inhibition detection?

Internal controls are essential for distinguishing true target absence from PCR failure due to inhibition. Two primary approaches are recommended:

Non-competitive Synthetic Controls: Design a synthetic DNA or RNA sequence with the same primer binding regions as your target but with a different internal sequence, allowing differentiation during detection. This control should be added to the reaction mixture at a known, consistent concentration [55].

Spike-In Controls: Introduce a control sequence that is not present in your biological sample. For RNA detection in stool, the cel-miR-39 spike-in from microRNA spike-in kits has been successfully used [56]. The control should be added after the initial homogenization step but prior to nucleic acid extraction to monitor the entire process from extraction through amplification.

What is the optimal method for constructing standard curves to quantify inhibition?

Standard curves serve as critical tools for quantifying amplification efficiency and detecting inhibition. Follow this protocol for reliable standard curve construction:

- Template Preparation: Create a dilution series of your target nucleic acid (typically 5-10-fold dilutions) in the same matrix as your samples (e.g., stool extract from a negative sample) [56].

- Amplification: Amplify each dilution in triplicate alongside your experimental samples.

- Data Analysis: Plot the log of the initial template quantity against the quantification cycle (Cq) value for each dilution.

- Efficiency Calculation: Calculate PCR efficiency using the formula: ( E = (10^{-1/slope} - 1) \times 100\% )

- Interpretation: An ideal reaction has an efficiency of 90-105% (slope of -3.6 to -3.1). Significant deviation from this range indicates potential inhibition affecting reaction efficiency [57].

How can I troubleshoot sporadic PCR inhibition in my stool samples?

Sporadic inhibition can be particularly challenging in high-throughput settings. Implement these strategies:

- Sample Dilution: Dilute template DNA/RNA (1:10 or 1:100) to reduce inhibitor concentration while maintaining detectable target levels [54].

- BSA Enhancement: Incorporate bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 0.1-0.5 μg/μL final concentration in the PCR reaction. BSA binds inhibitors, preventing their interference with the polymerase. This approach reduced PCR failure rates to 0.1% in one large-scale study processing over 1,000,000 samples [24].

- Alternative Polymerases: Use inhibitor-resistant polymerase blends specifically formulated for challenging samples.

- Modified Extraction Protocols: Implement additional purification steps, such as silica-based columns or magnetic bead clean-up, to enhance inhibitor removal [56].

Research Reagent Solutions for Inhibition Management

Table 1: Essential reagents for overcoming PCR inhibition in stool samples

| Reagent | Function | Application Example | Recommended Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Binds to PCR inhibitors, preventing their interaction with polymerase | Overcoming sporadic inhibition in buccal swabs and stool samples [24] | 0.1-0.5 μg/μL in PCR reaction |

| cel-miR-39 Spike-in | RNA extraction and reverse transcription control | Monitoring RNA extraction efficiency from stool samples [56] | 3 μL per sample (as per manufacturer) |

| Stool Total RNA Purification Kit | Optimized RNA extraction with inhibitor removal | High-purity RNA extraction from stool for sensitive mRNA detection [56] | As per manufacturer protocol |

| RNase-Free DNase Set | DNA contamination removal | Eliminating genomic DNA contamination from RNA samples [56] | As per manufacturer protocol |