Optimizing Wildlife Disease Surveillance: A Comprehensive Guide to Pooled Testing Strategies

This article provides a comprehensive framework for implementing and optimizing pooled testing in wildlife health surveillance.

Optimizing Wildlife Disease Surveillance: A Comprehensive Guide to Pooled Testing Strategies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for implementing and optimizing pooled testing in wildlife health surveillance. Aimed at researchers and surveillance professionals, it covers foundational principles, advanced methodological protocols, strategies for troubleshooting and cost optimization, and rigorous validation techniques. By synthesizing current research and practical applications, this guide aims to enhance the efficiency, accuracy, and cost-effectiveness of large-scale wildlife disease screening programs, crucial for managing emerging infectious diseases and protecting biodiversity.

The Principles and Imperatives of Wildlife Health Surveillance

Troubleshooting Guide for Pooled Testing in Wildlife Surveillance

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when implementing pooled testing protocols for wildlife disease surveillance.

FAQ 1: Our pooled testing results are inconsistent, with unexpected false negatives. What could be the cause?

Several factors can lead to false negatives in pooled testing. The table below outlines common causes and corrective actions based on proficiency testing guidance [1].

| Suspected Cause | Troubleshooting Actions | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Specimen Handling Error | Check sample storage temperature and handling delays. Verify pipette calibration [1]. | Train staff on proper routing and storage. Implement a lab calendar for PT sample arrival [1]. |

| Reagent Issue | Check for recent reagent lot changes or near-expiry reagents. Review QC records from the day of testing [1]. | Establish a rigorous validation process for new reagent lots using patient samples. Improve reagent storage and expiration date management [1]. |

| Pool Size Too Large | Re-test samples individually to confirm false negatives. Review the disease prevalence in your population [2]. | Re-calculate the optimal pool size using statistical tools to minimize dilution effects. Use prevalence data to inform pool size selection [3] [2]. |

| Instrument Technical Problem | Check instrument maintenance logs and action logs for errors around the time of testing [1]. | Perform preventative maintenance. Contact the manufacturer for assistance if systematic errors are suspected [1]. |

FAQ 2: How do we determine the optimal pool size for a new wildlife disease surveillance program?

Optimal pool size is a balance between cost efficiency and test sensitivity. The goal is to use the largest pool size that does not significantly reduce the assay's ability to detect a positive sample [2]. This depends primarily on two factors:

- Disease Prevalence: Pooled testing is most efficient for screening diseases with low prevalence [4] [2]. As prevalence increases, more pools test positive, requiring individual retests and reducing efficiency.

- Assay Sensitivity: The more sensitive the test, the larger the potential pool size. For example, one study found that while ELISA could detect CWD in a 1:9 pool, the more sensitive RT-QuIC assay could detect it in a 1:49 pool [3].

Actionable Protocol: To determine your pool size:

- Estimate Prevalence: Use historical data or preliminary surveys to estimate the disease prevalence (p) in your population.

- Validate Experimentally: Conduct a pilot study. Create pools of various sizes (e.g., 1:5, 1:10, 1:20) by diluting a known positive sample with confirmed negative samples. The largest pool size that consistently returns a positive result is your maximum viable size [3].

- Use Statistical Tools: Leverage available R packages and software designed to optimize pool size based on prevalence and test accuracy metrics [2].

FAQ 3: What are the primary advantages and disadvantages of implementing a pooled testing strategy?

Pooled testing offers significant benefits but also presents unique challenges, as summarized below [4].

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Conserves testing reagents and reduces overall costs [3] [4]. | Reduces test sensitivity due to sample dilution, risking false negatives [4]. |

| Increases surveillance capacity, allowing more individuals to be tested [3] [4]. | Lacks established infrastructure for sample aliquoting and data management, increasing manual error risk [4]. |

| Useful for large-scale screening in low-prevalence populations [2]. | Increases turnaround time for positive results due to the need for retesting [4]. |

| Can facilitate the use of ultra-sensitive, commercially viable new assays [3]. | Does not conserve sample collection materials (swabs, vials) [4]. |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Pooling Thresholds for Wildlife Disease Surveillance

The following detailed methodology is adapted from a study on Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) testing [3].

1. Objective To evaluate the efficacy of pooled testing for a wildlife disease using both a standard screening assay (e.g., ELISA) and a novel, highly sensitive assay (e.g., RT-QuIC).

2. Materials and Reagents

- Tissue Samples: Collected from a wildlife species of interest (e.g., medial retropharyngeal lymph nodes (RPLNs) from white-tailed deer).

- Homogenization Equipment: Grinding tubes and a homogenizer.

- Diagnostic Kits:

- Standard assay (e.g., TeSeE ELISA Purification and Detection Kits).

- Novel assay (e.g., reagents for Real-Time Quaking-Induced Conversion (RT-QuIC)).

- Laboratory Equipment: Microplate reader, plate washer, and real-time thermoshaker.

3. Procedure

- Step 1: Sample Collection and Storage

- Collect tissue samples post-mortem from wildlife, following standard field protocols.

- Place samples in individually labeled bags and store frozen (-20°C) until processing.

Step 2: Assigning Tissue Pools

- Use a predefined number of confirmed positive and test-negative samples.

- Create tissue pools by combining one positive "spike" sample with an increasing number of negative samples. Each individual contributes an equal tissue mass.

- Example pooling thresholds: 1:1, 1:2, 1:4, 1:9, 1:19, and 1:49 [3].

Step 3: Tissue Homogenization for Pooled Testing

- Partially thaw samples and trim excess connective tissue.

- For each pool, apportion the calculated tissue mass from each constituent sample into a tared grinding tube.

- The tissue mass per individual decreases as the pool size increases (e.g., from 100mg per individual in a 1:1 pool to 20mg in a 1:9 pool) [3].

- Homogenize the tissue according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Step 4: Diagnostic Testing

- ELISA Screening: Test the pooled homogenates using the standard commercial ELISA kit, following the manufacturer's instructions. Record optical densities (ODs).

- Novel Assay Testing: Test the pooled homogenates using the sensitive assay (e.g., RT-QuIC). This may require a specific tissue dilution (e.g., 0.02% tissue homogenate) [3].

Step 5: Data Analysis

- Determine the maximum pooling threshold at which each assay reliably returns a positive result for the spiked sample.

- Compare the cost per test and detection sensitivity between the two assays at different pool sizes.

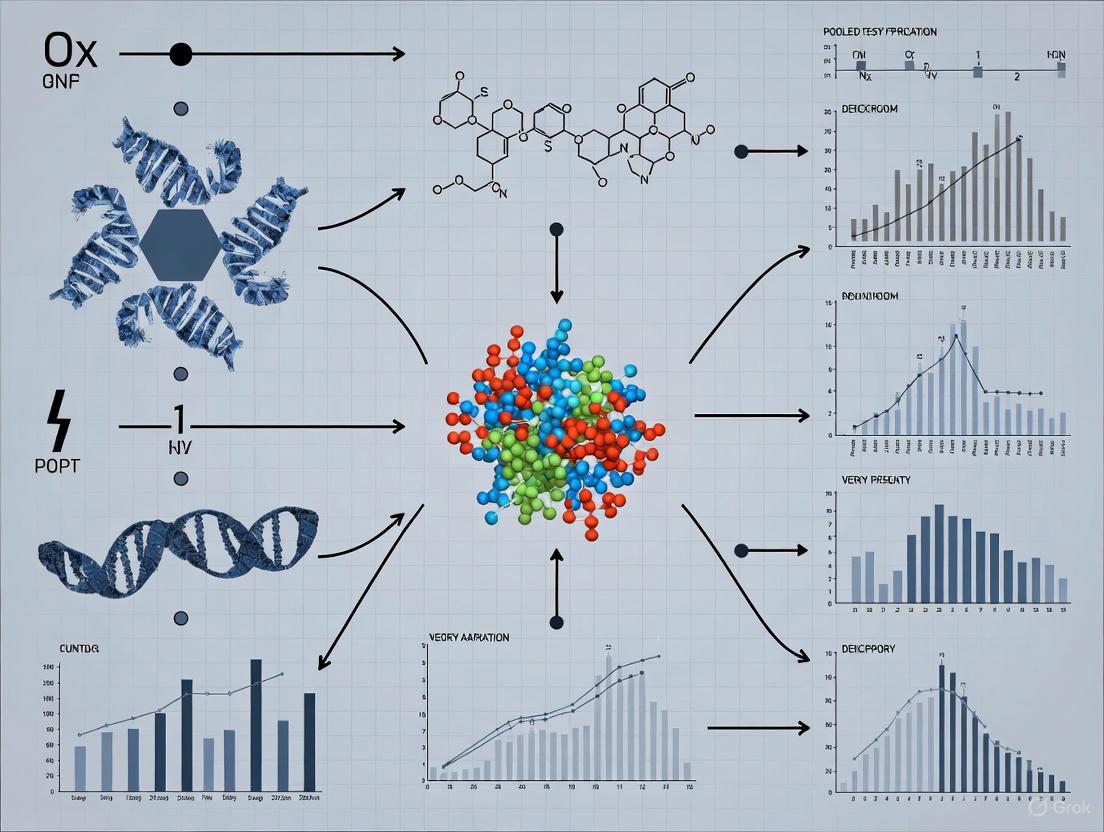

Wildlife Pooled Testing Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow for implementing a pooled testing strategy in wildlife disease surveillance.

Research Reagent Solutions for Wildlife Pooled Testing

The table below lists key materials and reagents essential for conducting pooled testing in wildlife disease surveillance.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Pooled Testing |

|---|---|

| Homogenization Tubes | Containers designed for grinding and homogenizing solid tissue samples (e.g., lymph nodes) into a uniform liquid suspension for testing [3]. |

| ELISA Kits | Commercial test kits containing all necessary antibodies, substrates, and buffers to detect pathogen-specific proteins (antigens) via an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The current standard for CWD screening [3]. |

| RT-QuIC Reagents | Chemicals and recombinant prion protein substrate required for the Real-Time Quaking-Induced Conversion assay, an ultra-sensitive method to amplify and detect misfolded prion proteins [3]. |

| Retropharyngeal Lymph Node (RPLN) Tissue | The target tissue routinely collected from cervids for CWD surveillance. Serves as the source of the pathogen in the test sample [3]. |

| Sample Collection Kits | Include Whirl-Pak bags, labels, and preservatives for sterile and organized sample collection and transport from the field to the lab [3]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the primary zoological and ecological factors that can lead to errors in my wildlife disease study design? A1: The main factors are related to the intrinsic characteristics of wildlife populations and their environments. Impediments include the unknown population densities of free-ranging animals, diverse zoological and behavioral characteristics, and limited access to investigation materials. These can lead to biased samples and incorrect prevalence estimates if not properly accounted for in your study design [5].

Q2: Why is my pooled testing protocol yielding inaccurate prevalence estimates for a wildlife pathogen? A2: Traditional pooled testing algorithms often assume each individual has the same probability of being positive. This is frequently unrealistic in wildlife populations, where individuals have varying risks based on species, age, location, or behavior. Using non-informative procedures in a heterogeneous population can reduce the accuracy of your prevalence estimates and testing efficiency [6].

Q3: How can I improve the cost-efficiency of a wildlife disease surveillance program that uses pooled testing? A3: Consider implementing informative retesting procedures. These methods use known risk factors (e.g., species, sex, geographic origin) to estimate an individual's probability of infection. This information is then used to form pools strategically, minimize the number of positive pools, and determine the order of individual retesting, which significantly reduces the total number of tests required [6].

Q4: What is the key difference between scanning and targeted surveillance in wildlife health? A4: Scanning (or passive) surveillance typically involves the investigation of sick or dead animals that are found and submitted, making it effective for detecting mortality events. Targeted (or active) surveillance involves proactively sampling live or apparently healthy animals to detect specific pathogens or antibodies, which is crucial for identifying healthy carriers of important zoonotic or economically significant pathogens [5].

Q5: We demonstrated freedom from a disease in a wildlife population, but the results are being questioned. What common pitfall might we have encountered? A5: Demonstrating disease freedom requires robust survey design and a thorough understanding of population parameters. A common pitfall is the lack of data on free-ranging population densities, which makes it difficult to confirm that your sample size is sufficiently large and representative to reliably detect the disease if it were present [5].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconclusive or conflicting diagnostic test results from wildlife samples.

- Potential Cause: Many diagnostic tests are developed and validated for domestic animals and may not perform accurately with wildlife species due to physiological and immunological differences [5].

- Solution: Whenever possible, use diagnostic tests that have been specifically validated for your target wildlife species. If such tests are unavailable, clearly state this as a limitation in your research and interpret results with caution. There is a recognized need for more development and validation of diagnostic tests specifically for wildlife [5].

Problem: Pooled testing results in an unexpectedly high number of positive pools, making the process inefficient.

- Potential Cause: The pool size may be too large for the actual disease prevalence, or the population may be more heterogeneous than anticipated.

- Solution: Optimize your pool size using statistical models that account for the estimated prevalence. For heterogeneous populations, switch from a standard Dorfman testing method to an informative procedure like Pool-specific Optimal Dorfman (PSOD) or Informative Sterrett, which leverage individual risk factors to create smarter pool configurations [6].

Problem: Failure to detect an emerging disease outbreak in a wildlife population during routine surveillance.

- Potential Cause: Reliance on a single data source (e.g., only carcass collection) and a lack of an interdisciplinary approach.

- Solution: Implement a triangulation approach by integrating multiple data sources. Enhance your surveillance by incorporating data from wildlife rehabilitation centers, camera trapping for animals with visible lesions, and samples from hunted or farmed wildlife. This creates a more sensitive early-warning system [5].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Detailed Methodology: Informative Dorfman Testing for Wildlife Surveillance

This protocol adapts pooled testing for heterogeneous wildlife populations.

1. Pre-Sampling Phase: Data Collection and Risk Modeling

- Step 1: For each individual or sample, collect all available risk factors (e.g., species, age class, sex, geographical location, known migration patterns, proximity to human settlements).

- Step 2: If a training dataset exists (historical surveillance data from a similar population), use it to fit a binary regression model (e.g., logistic regression) to predict the probability of infection based on the risk factors.

- Step 3: Apply this model to your current sample set to estimate an individual risk probability of being positive for each specimen.

2. Pool Formation Phase

- Step 4: Order all specimens from highest to lowest estimated risk.

- Step 5: For Threshold Optimal Dorfman (TOD), set a probability threshold. Specimens above the threshold are tested individually. Specimens below the threshold are grouped into pools of optimal size

s, calculated to minimize the expected number of tests. - Step 6: For Pool-specific Optimal Dorfman (PSOD), starting from the highest-risk specimen, algorithmically assign successive specimens into pools of variable sizes

s1, s2, s3,...that collectively minimize the expected number of tests.

3. Testing and Decoding Phase

- Step 7: Test each pool. Any pool that tests negative is declared free of infection; all members are categorized as negative.

- Step 8: For any pool that tests positive, all individual specimens within that pool are tested to decode and identify the positive individual(s).

Table 1: Comparison of Wildlife Health Surveillance Types [5]

| Surveillance Type | Key Objective | Typical Data Source | Best For | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scanning (Passive) | Early detection of outbreaks/mortality events | Carcasses; sick animals from the public | Detecting novel disease events; clinical diseases | Reporter bias; often no population denominator data |

| Targeted (Active) | Estimate disease prevalence; demonstrate disease freedom | Proactive sampling of live or hunter-harvested animals | Monitoring known pathogens; healthy carriers | Requires knowledge of population ecology for valid sampling |

Table 2: Overview of Common Pooled Testing Procedures [6]

| Procedure | Type | Key Principle | Ideal Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dorfman | Non-Informative | Simple two-stage: test pool, then test all individuals in positive pools. | Homogeneous populations; low prevalence; simplicity is key. |

| Halving (3H, 4H) | Non-Informative | Iteratively split a positive pool into smaller sub-pools. | Moderately high-throughput; can be more efficient than Dorfman. |

| Sterrett | Non-Informative | After a positive pool, test individuals one-by-one and re-pool remainder. | Populations where most positive pools contain only one positive. |

| Matrix Testing | Non-Informative | Arrange samples in a grid; test row and column pools. | Very high-throughput screening of many samples. |

| TOD / PSOD | Informative | Use risk probabilities to form optimal pools. | Heterogeneous wildlife populations with known risk factors. |

| Informative Sterrett | Informative | Use risk probabilities to determine retesting order in positive pools. | Heterogeneous wildlife populations where re-pooling is feasible. |

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Material Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Wildlife Health Investigations

| Item / Solution | Function in Wildlife Health Investigations |

|---|---|

| Validated Diagnostic Assays | Species-specific serological or molecular tests (e.g., ELISA, PCR) validated for wildlife to ensure accurate detection of pathogens or antibodies [5]. |

| Risk Factor Data | Pre-existing data on species, ecology, and individual traits used to build statistical models for informative pooled testing and study design [6]. |

| Standardized Necropsy Kits | Field kits for thorough post-mortem examination of carcasses, which is the foundation of scanning surveillance and mortality event investigation [5]. |

| Sample Pooling Matrix | The liquid medium (e.g., transport media) used to composite individual specimens (blood, tissue homogenate) into a single pool for group testing [6] [7]. |

| Metadata Tracking System | A standardized database for recording crucial ecological, spatial, and temporal metadata alongside health data, which is essential for valid analysis and interpretation [5]. |

This technical support center provides troubleshooting and guidance for researchers implementing pooled testing approaches in wildlife disease surveillance. Pooled testing, where samples from multiple animals are combined and tested as a single unit, is a efficient strategy for large-scale screening, particularly when disease prevalence is low [8]. This resource addresses common experimental challenges and outlines best practices to ensure your data is reliable, reproducible, and compliant with emerging global standards for wildlife disease data [9] [10].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: When is pooled testing most effective, and how do I determine the optimal pool size?

A: Pooled testing is most efficient for screening large populations with a low disease prevalence and when testing a consistent subpopulation repeatedly [8] [4]. The efficiency gains are mechanical and epidemiological: frequent testing removes infected individuals quickly, lowering subsequent infection probability within the group and making future pooled tests more likely to be negative [8].

- Troubleshooting Guide: Inefficient Pooling

- Problem: Too many pools are testing positive, requiring costly individual re-testing.

- Potential Cause: The disease prevalence in your sampled population is higher than anticipated.

- Solution: Re-assess your population's infection rate. Reduce the pool size to minimize dilution effects and false negatives. The optimal pool size is a balance; while larger pools test more individuals at once, they also increase the risk of sample dilution and lower test sensitivity [4].

Q2: How does frequent testing and the "natural groupings" of wildlife impact pooled testing strategy?

A: Increasing testing frequency can paradoxically reduce the total number of tests required. When a population is tested frequently, the probability of infection at any given test is low, making large pools more efficient [8]. Furthermore, using natural groupings (e.g., animals from the same herd, social group, or geographic cluster) is highly advantageous because their correlated infection risk lowers the overall likelihood of a positive pool result, enhancing efficiency [8].

Q3: Our pooled test was positive, but subsequent individual tests were all negative. What happened?

A: This discrepancy could arise from several factors:

- Sample Cross-Contamination: During the manual aliquoting and pooling process, samples can be contaminated [4]. Review sterile pipetting techniques and use a laboratory information system to track samples.

- Test Sensitivity/Specificity Issues: The test may have imperfect specificity, leading to a false positive pool result.

- Low Viral Load: An individual with a very low viral load may test positive in a concentrated pool but fall below the detection threshold when tested individually due to dilution [4].

Q4: What are the critical data fields I must report when publishing pooled testing results for wildlife?

A: To ensure data is FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable), adhere to minimum data standards. The table below summarizes key required and conditional fields based on a recent standard for wildlife disease research [9] [10].

- Crucially, you must report negative results and data at the finest possible spatial, temporal, and taxonomic scale, not just summaries [9] [10].

| Field Category | Field Name | Requirement Level | Notes for Pooled Testing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling Data | Sample ID | Required | Unique identifier for each sample collected. |

| Animal ID | Conditional | Leave blank if animals are not individually identified [9]. | |

| Pool ID | Recommended | Critical for pooling. A unique identifier for the sample pool. | |

| Test date | Required | Date the diagnostic test was performed. | |

| Host Data | Host species | Required | Use a controlled vocabulary (e.g., GBIF) where possible [9]. |

| Location | Required | Geographic coordinates of sampling. May require obfuscation for sensitive species [10]. | |

| Parasite/Pathogen Data | Pathogen tested for | Required | The target parasite or pathogen. |

| Diagnostic test | Required | e.g., PCR, ELISA. | |

| Test result | Required | Positive, negative, or inconclusive for the pool. | |

| Pathogen identity | Conditional | Report if available (e.g., GenBank accession for positive samples) [9]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Workflow for Pooled Sample Testing

The following diagram illustrates the core decision-making process for a pooled testing strategy, from sample collection to final result reporting.

Detailed Methodology: Implementing a Pooled PCR Testing Protocol

This protocol is adapted for detecting a viral pathogen (e.g., a coronavirus) in oral or rectal swabs from bats [9], a common wildlife surveillance target.

Sample Collection & Storage:

- Collect individual swab samples from each animal in the field, placing them in labeled vials containing viral transport media.

- Store samples immediately on dry ice or in a liquid nitrogen dry shipper for transport to the laboratory.

- Metadata Recording: Record all required data fields (see Table above) for each sample at the time of collection.

Pool Construction (in a BSL-2 or appropriate containment lab):

- Determine Pool Size: Based on preliminary prevalence estimates, define a optimal pool size (e.g., 5 samples per pool) [8].

- Thaw and Vortex Samples.

- Aliquot and Combine: Using sterile pipette tips for each sample, aliquot a defined volume (e.g., 50 µL) from each individual sample vial into a new, labeled master tube (the "pool").

- Maintain Chain of Custody: Meticulously track which individual samples constitute each pool. Using a Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) is highly recommended to avoid human error [4].

Nucleic Acid Extraction & PCR:

- Extract total nucleic acid from the pooled sample according to your preferred kit's manufacturer instructions.

- Perform the PCR reaction using pathogen-specific primers and controls (negative and positive).

- Follow the workflow in the diagram above: If the pool tests negative, report all constituent samples as negative. If positive, proceed to step 4.

Deconvolution of Positive Pools:

- Return to the original, archived sample vials for every member of the positive pool.

- Perform individual nucleic acid extraction and PCR testing on each of these original samples.

- Report the final results for each individual animal.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and their functions for setting up a pooled testing experiment for wildlife disease surveillance.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Viral Transport Media | Preserves virus viability and nucleic acids during sample transport from the field to the lab. |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit | Isolates DNA/RNA from the pooled sample for downstream molecular analysis. |

| Pathogen-specific Primers/Probes | For PCR/dPCR assays; designed to target conserved regions of the pathogen's genome. |

| PCR Master Mix | Contains enzymes, dNTPs, and buffer necessary for the nucleic acid amplification reaction. |

| Positive Control | Contains a known, non-infectious fragment of the target pathogen's genome to validate the test's performance. |

| Negative Control | Nuclease-free water to monitor for cross-contamination during the testing process. |

| Laboratory Information Management System | Tracks samples, pool compositions, and test results to prevent manual errors [4]. |

FAQs: Wildlife Disease Data Management and Standardization

Q1: What is a wildlife disease data standard and why is it important?

A data standard is a common structure and set of properties for recording and sharing information. For wildlife disease research, a minimum data standard ensures that data from different studies are Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR). This is critical for aggregating datasets to test ecological theory, monitor the impacts of climate change, and track emerging threats to human and ecosystem health. Standardization solves the problem of reconciling datasets that vary greatly in scope and granularity, enabling more powerful and actionable synthesis research [9].

Q2: My study uses a pooled testing approach. How does this affect my data reporting?

The data standard is flexible enough to accommodate pooled testing designs. When samples from multiple animals are combined in a single test:

- If individual animals are identified, you can link the single test result to multiple Animal ID values.

- If animals are not individually identified (e.g., mosquito pools), the Animal ID field can be left blank. You must still report all relevant information about the pool, including the diagnostic method used, the test result, and the location and date of sampling [9].

Q3: What are the most critical data fields to report?

The proposed minimum data standard includes 40 core data fields. While the full list should be consulted, 9 fields are considered required to ensure basic interoperability and usefulness. The table below summarizes these mandatory fields [9].

| Category | Required Field Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Project Metadata | Project Title | The official title of the research project. |

| Project Personnel | Individuals responsible for creating the dataset. | |

| Project Funding | Organizations or grant numbers that funded the work. | |

| Project License | The license under which the data are published. | |

| Geodetic Datum | The coordinate reference system (e.g., WGS84). | |

| Sample Identifier | A unique ID for the sample, from which a test result is derived. | |

| Animal ID | A unique identifier for the host animal (can be blank for pooled samples). | |

| Observation Date | The date the host animal was sampled. | |

| Latitude | The latitude of the sampling location in decimal degrees. | |

| Longitude | The longitude of the sampling location in decimal degrees. | |

| Diagnostic Method | The method used for parasite detection (e.g., PCR, ELISA, culture). | |

| Test Result | The outcome of the diagnostic test (e.g., positive, negative, inconclusive). | |

| Parasite Taxon | The scientific name of the detected parasite, if applicable. |

Q4: Why must I report negative test results?

Reporting negative results is essential for calculating accurate disease prevalence and understanding pathogen dynamics. When only positive results are shared, it is impossible to compare prevalence across different populations, time periods, or host species. This creates significant bias in synthetic studies and meta-analyses. Including negative data provides the complete picture needed for robust epidemiological analysis [9] [10].

Q5: What are the best practices for sharing sensitive data, like locations of threatened species?

The standard includes guidance for ethical and secure data sharing. For sensitive data, such as precise locations of threatened species or high-risk pathogens, you should:

- Obfuscate location data: Generalize coordinates to a larger area (e.g., round to fewer decimal places) to protect vulnerable populations.

- Use context-aware sharing: Evaluate the potential for misuse (e.g., wildlife culling, bioterrorism) and employ data embargoes or restricted-access protocols in repositories where necessary [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent or Non-Interoperable Datasets

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inability to merge your data with other studies for analysis. | Missing required metadata; data shared only in summary tables, not disaggregated; inconsistent formatting. | Adopt the minimum data standard. Share disaggregated data in a "tidy" format where each row is a single test. Use the provided templates and validation tools to ensure consistency [9]. |

| Data cannot be understood or reused by others. | Lack of project metadata and data dictionaries. | Document the dataset with the 24 metadata fields (7 required), including license, geodetic datum, and detailed diagnostic method descriptions. Use controlled vocabularies where possible [9]. |

Issue 2: Challenges with Non-Invasive Sampling Methods

Non-invasive sampling minimizes stress and impact on wildlife, aligning with ethical 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) principles. Below are common methods and their applications [11].

| Sample Material | Primary Collection Method | Key Applications in Disease/Health Research |

|---|---|---|

| Faeces | Collection from habitat | Stress hormone assessment; diet studies; detection of viruses, bacteria, helminths, and protozoa. |

| Hair/Feathers/Skin | Hair traps; collection from resting sites | Genetics; pollutant studies; detection of some ectoparasites. |

| Urine | Collection from habitat/surfaces | Stress physiology; reproductive hormone assessment; detection of some pathogens (e.g., leptospirosis). |

| Saliva & Other Body Fluids | Collection from discarded materials (e.g., chewed plants) | Pathogen detection (e.g., rabies); immunoglobulin and antibody assays. |

| Invertebrates | Trapping blood-sucking invertebrates (e.g., mosquitoes, ticks) | Indirect collection of host blood for pathogen screening. |

Workflow for Implementing a Non-Invasive Method:

Issue 3: Data Formatting and Validation Errors

| Symptom | Solution |

|---|---|

| Errors when uploading to repositories or using validation tools. | Format data as a rectangular/tidy dataset (e.g., a CSV file). Use the provided template files (.csv or .xlsx) from the standard's GitHub repository to ensure correct structure [9]. |

| Uncertainty about whether your dataset is compliant. | Use the JSON Schema or the dedicated R package (wddsWizard) available on GitHub to automatically validate your data and metadata against the standard before submission [9]. |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and resources used in wildlife disease surveillance, from sample collection to data publication.

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Wildlife Disease Surveillance |

|---|---|

| Non-Invasive Sample Collection Kits | Used for gathering faeces, hair, or other materials without handling animals. Includes sterile swabs, gloves, and stable storage tubes for transport [11]. |

| Controlled Vocabularies & Ontologies | Standardized lists of terms (e.g., for species names, diagnostic methods) that improve data interoperability and machine-readability [9]. |

| Data Validation Software (R package/JSON Schema) | Automated tools that check a dataset's structure and content against the data standard, ensuring compliance before sharing [9]. |

| Generalist Data Repository (e.g., Zenodo) | An open-access platform for publishing and preserving final datasets, ensuring they are findable and citable with a persistent DOI [9] [10]. |

| Specialist Data Platform (e.g., PHAROS, GBIF) | A dedicated database for wildlife disease or biodiversity data, offering tools for analysis, visualization, and integration with other datasets [9] [12]. |

Workflow for Managing a Pooled Testing Study

This diagram outlines the key steps for designing, executing, and reporting a study that uses pooled samples, ensuring data is structured for broader integration.

The Role of Pooled Testing in Addressing Wildlife Surveillance Constraints

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is pooled testing and when should it be used in wildlife surveillance? Pooled testing is a procedure where individual specimens (e.g., tissue, swabs) from multiple animals are combined into a single pool and tested as one sample [6] [4]. It is most effective and cost-efficient for screening wildlife populations with low disease prevalence [4] [2]. This approach is particularly valuable for conserving limited testing reagents, reducing costs, and facilitating surveillance of large populations [4].

2. How does pooled testing affect the sensitivity of diagnostic tests? Pooling samples can lead to a reduction in sensitivity due to the dilution of positive material [4]. The degree of sensitivity loss depends on the pool size and the analytical sensitivity of the test itself. For example, in one study, ELISA detected Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) in pools of up to 9 individuals, while the more sensitive RT-QuIC assay detected it in pools of up to 49 individuals [3]. Each assay and pool size requires laboratory validation to confirm acceptable performance [4].

3. What are the key steps for validating a pooled testing protocol in my lab? Laboratories must conduct their own validation studies to demonstrate minimal loss of analytical sensitivity when moving from individual to pool testing [4]. This includes:

- Population-Specific Validation: Testing should be relevant to the wildlife populations being surveyed (e.g., species, tissue type).

- Assay-Specific Validation: Each diagnostic assay used must be individually validated for pooled samples.

- Determining Pooling Threshold: Establishing the maximum number of samples that can be pooled while maintaining reliable detection of a positive sample [3].

4. What are the main data reporting standards for wildlife disease research? When sharing data, researchers should adhere to minimum reporting standards. Key data fields include [9]:

- Sample Data: Sample ID, collection date, and geographic coordinates.

- Host Data: Host species, sex, and age class.

- Parasite Data: Diagnostic test used, test result, and parasite identity (if detected). Data should be shared in a "tidy" format where each row corresponds to a single test outcome, facilitating reuse and aggregation [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Number of Positive Pools Leading to Increased Testing

Problem: The number of positive pools is high, negating the cost and efficiency benefits of pooled testing.

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| High disease prevalence | Re-evaluate the suitability of pooled testing. It is not cost-effective when prevalence is high (e.g., >15%) [2]. Consider switching to individual testing or using more advanced algorithms like informative retesting that use risk factors to group animals [6]. |

| Inappropriately large pool size | Reduce the pool size. Larger pools are more likely to contain at least one positive individual. Determine the optimal pool size statistically, balancing test reduction with the probability of pool positivity [2]. |

| Contamination during pooling | Review and standardize manual aliquoting procedures. Implement rigorous quality control measures to avoid cross-contamination between samples, which can cause false positives [4]. |

Issue 2: Inconsistent or Unexpected Test Results

Problem: Test results from pooled samples are variable, or a known positive sample is not detected in a pool.

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Loss of analytical sensitivity | This is a common challenge [4]. Validate the pool size to ensure the target pathogen is still detectable after dilution. Use a more sensitive diagnostic assay (e.g., RT-QuIC over ELISA) to achieve higher pooling thresholds [3]. |

| Improper sample homogenization | Ensure tissue or specimen samples are thoroughly and consistently homogenized before creating the pool aliquot to guarantee a representative sample [3]. |

| Testing error | Implement retesting protocols for verification. Use controls in each test run to monitor assay performance and identify potential errors [4]. |

Issue 3: Logistical and Workflow Challenges

Problem: The process of manually creating pools is time-consuming and increases the risk of specimen mix-up.

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Manual specimen handling | Automated specimen aliquoting systems can minimize human error but require investment [4]. Without automation, develop a strict sample tracking system and standardized workflows to manage pooling and deconstruction of positive pools. |

| Lack of software support | Utilize or develop laboratory information system (LIS) support to track individual specimens through the pooling and retesting process, reducing the risk of data entry errors [4]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Validating a Pooled Testing Protocol for CWD

The following protocol, adapted from a study evaluating CWD in white-tailed deer, provides a template for validating pooled testing for other wildlife diseases [3].

1. Tissue Collection and Preparation:

- Collect tissue samples (e.g., retropharyngeal lymph nodes) according to standard field surveillance procedures.

- Partially thaw samples and trim excess connective tissue.

- For each pool, apportion a defined mass of tissue from each individual into a homogenization tube. The mass per individual decreases as the pool size increases (e.g., from 100 mg per individual in a 1:1 pool to 20 mg in a 1:9 pool) [3].

2. Creating Tissue Pools:

- Prepare pools by combining tissue from one known positive individual with tissue from a increasing number of known negative individuals (e.g., 1:1, 1:4, 1:9, 1:19).

- Homogenize the combined tissue thoroughly using a standardized method (e.g., grinding tubes) [3].

3. Analytical Testing:

- Test the pooled tissue homogenates using the standard screening assay (e.g., ELISA) and/or more sensitive research assays (e.g., RT-QuIC).

- Include appropriate positive and negative controls in each test run.

- Record the results for each pool size to determine the maximum pooling threshold at which the positive sample is still reliably detected [3].

Quantitative Data from Wildlife Pooled Testing Studies

The table below summarizes key findings from a study on Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD), demonstrating how different assays perform under pooled conditions [3].

| Diagnostic Assay | Target | Maximum Validated Pool Size | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| ELISA | Prion protein (PrPCWD) | 1:9 | Remained positive at a standard tissue homogenate volume, but with a lower pooling threshold than more sensitive assays. |

| RT-QuIC (Real-Time Quaking-Induced Conversion) | Prion protein (PrPCWD) | 1:49 | Detected the target pathogen in much larger pools due to its signal amplification nature, significantly reducing per-sample costs. |

Comparison of Pooled Testing Algorithms

The table below compares different pooling algorithms, which can be chosen based on prevalence and available individual risk information [6].

| Algorithm | Description | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Dorfman Testing | Simple two-stage method; test pools, then retest all individuals in positive pools. | Low prevalence populations; simplest to implement. |

| Halving | A positive pool is split into two sub-pools for testing, recursively. | Low prevalence; can be more efficient than Dorfman. |

| Sterrett's Procedure | After a positive pool, test individuals one-by-one until a positive is found, then re-pool the remainder. | Populations where only one positive per pool is likely. |

| Array Testing | Individuals are assigned to multiple pools in a grid; retesting occurs at intersections of positive rows/columns. | High-throughput screening; can be more efficient than hierarchical methods. |

| Informative Retesting | Uses individual risk factors (e.g., age, location) to assign individuals to pools and order retesting. | Heterogeneous populations where some individuals have higher known risk. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Pooled Testing |

|---|---|

| TeSeE ELISA Kit (Bio-Rad) | A commercially available immunoassay for detecting the abnormal prion protein associated with CWD, used for initial screening of individual or pooled samples [3]. |

| Homogenization/Grinding Tubes | Specially designed tubes containing lysing matrix for mechanical disruption and homogenization of tissue samples, ensuring a uniform representative aliquot for testing [3]. |

| RT-QuIC Reagents | Components for the Real-Time Quaking-Induced Conversion assay, including recombinant prion protein substrate, buffers, and a fluorescent dye (e.g., Thioflavin T) to detect amyloid fibril formation through amplification [3]. |

| Pooling Matrix Software | Custom or commercial software to manage the complex logistics of sample pooling, including tracking individual specimens through pool assignment and decoding positive pools [4]. |

Workflow Diagram

Implementing Pooled Testing Protocols: From Dorfman to Advanced Strategies

Dorfman testing, introduced by Robert Dorfman in 1943, is a two-stage hierarchical group testing algorithm designed to efficiently identify rare diseases in large populations. Originally proposed to screen military recruits for syphilis, this method reduces the total number of tests required by initially pooling specimens for testing [13] [2].

In this approach, individual specimens are combined into a single master pool during the first stage. If the pool tests negative, all individuals within it are declared disease-free. If the pool tests positive, a second stage of individual testing is performed to identify the specific positive cases [13]. This method is particularly advantageous in wildlife disease surveillance, where researchers often monitor diseases with low prevalence and operate under significant cost constraints [14] [2].

▷ How Dorfman Testing Works: A Visual Guide

The following diagram illustrates the two-stage hierarchical testing process.

▷ Optimal Pool Size Configuration

Determining the optimal pool size is critical for maximizing testing efficiency. The following table summarizes recommended pool sizes for different disease prevalence rates, based on empirical studies.

| Disease Prevalence | Optimal Pool Size | Expected Test Reduction | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (0.1% - 1%) | 11 - 33 | Up to 90% | Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) surveillance with RT-QuIC assay [14] |

| Moderate (1% - 5%) | 8 - 15 | 50% - 80% | Chlamydia/Gonorrhea screening with multiplex assays [13] [2] |

| High (>5%) | 3 - 8 | 20% - 50% | Not generally recommended above 10% prevalence [2] |

★ Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

▷ General Principles

What is the primary advantage of Dorfman testing in wildlife surveillance? Dorfman testing significantly reduces the number of tests required, which lowers costs and allows for more extensive monitoring within budget constraints. This is particularly valuable for natural resource agencies managing diseases like Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) in cervids, where diagnostic costs represent a major expenditure after staff time [14].

When is Dorfman testing not appropriate? This method is less efficient for high-prevalence diseases (>10%) where most pools would test positive, necessitating many second-stage individual tests. It also requires careful validation when using assays susceptible to dilution effects, which can reduce sensitivity when pooling multiple specimens [15].

▷ Experimental Design & Implementation

How do I determine the optimal pool size for my study? Optimal pool size depends primarily on disease prevalence and assay sensitivity. Lower prevalence allows for larger pools. For CWD surveillance using RT-QuIC, pools of up to 50 have been validated, while ELISA-based testing typically uses smaller pools of 5-10 [14]. Statistical optimization techniques can precisely calculate the most efficient size [2].

What are the critical considerations for specimen collection and handling? Ensure each specimen contributes an equal volume to the pool. For CWD testing, studies used precisely weighed tissue samples (e.g., 20±2mg per individual in a 1:9 pool). Proper homogenization is essential for consistent results across the pool [14].

▷ Troubleshooting Experimental Issues

How can I address dilution effects that reduce test sensitivity? Use more sensitive detection methods like RT-QuIC instead of ELISA, as they maintain detection capability even in large pools. For CWD, RT-QuIC detected positives in 1:49 pools at 0.02% tissue dilution, while ELISA was limited to 1:9 pools [14]. Alternatively, reduce pool size to maintain adequate target concentration.

What is the impact of assay error rates on classification accuracy? Assay sensitivity and specificity directly impact the number of false positives and negatives. Higher error rates necessitate smaller pools and may require confirmatory testing. The Markov chain approach can model these error rates to predict overall classification accuracy [13].

▷ Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table outlines key materials and their functions for implementing Dorfman testing in wildlife disease surveillance.

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Aptima Combo 2 Assay | Simultaneous detection of multiple infections (e.g., chlamydia, gonorrhea) | Discriminating between infections in pooled specimens [13] [2] |

| TeSeE ELISA (Bio-Rad) | Detection of prion protein (PrPCWD) in CWD surveillance | Initial screening of pooled retropharyngeal lymph nodes [14] |

| RT-QuIC Assay | Ultra-sensitive detection of prion aggregates through amplification | Identifying CWD positives in large pools (up to 1:49) [14] |

| Homogenization Tubes with Beads | Standardized tissue disruption for consistent pooling | Preparing uniform tissue homogenates from wildlife specimens [14] |

| Nucleic Acid Preservation Buffer | Stabilizes genetic material during transport and storage | Maintaining integrity of pathogen targets in field collections [9] |

▷ Advanced Methodological Extensions

Multiplex Assays for Multiple Infections Modern applications increasingly use discriminating multiplex assays that can detect multiple infections simultaneously from a single pool. The Aptima Combo 2 Assay simultaneously detects chlamydia and gonorrhea, while the Procleix Ultrio Assay discriminates among HIV, HBV, and HCV [13].

Higher-Stage Hierarchical Algorithms For even greater efficiency, researchers can implement S-stage hierarchical algorithms (S>2). These involve splitting positive pools into smaller subpools for additional stages of testing before proceeding to individual testing. This approach can provide an estimated 11% further reduction in tests compared to standard two-stage Dorfman testing [13].

Bayesian Approaches for Heterogeneous Populations Bayesian group testing methods incorporate prior information about infection probabilities and account for dilution effects. These approaches are particularly valuable when prevalence varies across subpopulations or when testing error is a significant concern [15].

Pooled testing is a cornerstone of efficient disease surveillance in wildlife research. While the Dorfman procedure is widely known, this guide details more sophisticated algorithms—Halving, Sterrett, and Array Testing—that can further reduce the number of tests required and conserve valuable reagents. These methods are particularly valuable for screening large wildlife populations for pathogens like bovine leukemia virus (BLV) or other diseases of interest where prevalence is low [6] [16]. The following sections provide a technical deep-dive, complete with troubleshooting guides and experimental protocols, to support their implementation in your research.

Comparison of Advanced Pooled Testing Procedures

The table below summarizes the core operational characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the three advanced procedures.

| Procedure | Core Operational Principle | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation | Ideal Use-Case Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halving [6] | A positive pool is split into two equal sub-pools. The process repeats for positive sub-pools (e.g., 3-4 steps) before individual testing. | Reduces the number of retests compared to Dorfman by eliminating sub-pools that test negative. | Can involve multiple testing rounds; may be time-consuming for very large pools. | Screening large batches where positivity is expected to be very low. |

| Sterrett [6] | Individuals from a positive pool are tested one-by-one until a positive is found. Remaining specimens are re-pooled and the process repeats. | Highly efficient when the number of positives in a pool is very small (often just one). | Efficiency decreases rapidly as the number of positives within a single pool increases. | Ideal for surveillance of very rare diseases within a population. |

| Array (Matrix) [6] | Specimens are arranged in a grid. Pools are made from each row and each column. Positives are identified at the intersection of a positive row and column. | Can screen a large number of specimens (n²) with only 2n tests in the first stage. | Decoding can be complex; testing errors can lead to misclassification. | High-throughput screening of many specimens when test accuracy is very high. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I consider using Halving over the standard Dorfman procedure? Use Halving when working with large initial pool sizes and you want to avoid the inefficiency of individually testing every member of a positive pool. Halving is more efficient than Dorfman when prevalence is low because it systematically eliminates negative sub-groups, reducing the total number of tests [6].

Q2: Our lab is dealing with a very rare pathogen. Which method is most suitable? For very rare pathogens, the Sterrett procedure is often optimal. Its efficiency is highest when there is a high probability that a positive pool contains only a single positive individual. By stopping individual testing after finding the first positive and re-pooling the rest, it minimizes test usage in this specific scenario [6].

Q3: What is the impact of test sensitivity and specificity on Array Testing? Array testing is susceptible to test errors. If a test yields a false positive or false negative, it can lead to the misclassification of multiple individuals. For example, a single false negative in a row or column could cause a true positive to be missed. Therefore, array testing requires a highly accurate and reliable PCR assay to be effective [6].

Q4: Can these methods be used for multiplex assays that detect multiple pathogens? Yes, the principles of these pooling algorithms can be extended to multiplex testing. Research is ongoing to develop and optimize regression models and hierarchical group testing protocols for the joint estimation of multiple disease prevalences from a single testing round, making it highly relevant for comprehensive wildlife disease surveillance [17].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High number of positive pools in Halving | Pool size is too large for the disease prevalence. | Re-estimate prevalence and use a smaller initial pool size. Re-configure the halving steps (e.g., use 3-step instead of 4-step). |

| Sterrett procedure is inefficient | Multiple positive individuals are present within single pools. | Re-evaluate the initial pool size. If prevalence is higher than anticipated, switch to a method like Halving or use smaller pools. |

| Inconsistent results in Array Testing | Low test sensitivity leading to false negatives, or cross-contamination leading to false positives. | Verify the limit of detection (LOD) of your PCR assay and confirm it is suitable for the dilution factor of pooling. Implement stringent anti-contamination protocols. |

| Low overall sensitivity in any pooled method | Specimen pooling has diluted the target pathogen below the assay's detection threshold. | Validate the pool size against your specific PCR assay's LOD. For a 5:1 pool, one study found PPA could range from 82% to 100%, depending on the test platform used [18]. Reduce pool size to mitigate dilution effects. |

| Difficulty identifying positive individuals in Array Testing | Complex pattern of positive rows/columns, potentially due to multiple infections or test error. | Perform individual (retesting) on all specimens located at the intersections of positive rows and columns. If a row tests positive but no columns do (or vice versa), individually test all members of that row/column [6]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Halving Procedure

This protocol is designed for screening wildlife samples for a specific genetic marker, such as the BoLA-DRB3*009:02 allele in cattle, using real-time PCR [16].

1. Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction

- Collect biological samples (e.g., blood, tissue) from the target wildlife population.

- Extract genomic DNA from each individual sample using a commercial kit (e.g., Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit or equivalent automated system).

- Quantify and normalize DNA concentrations to ensure uniformity.

2. Initial Pool Formation and Testing

- Pool Size: Based on preliminary prevalence estimates, form an initial pool of size n (e.g., n=8). Use a validated model to optimize the size for your expected prevalence.

- Pooling: Combine equal volumes of normalized DNA from each of the n individuals into a single microcentrifuge tube.

- Stage 1 PCR: Perform your validated real-time PCR assay (e.g., using a TaqMan MGB probe) on the pooled sample.

- Interpretation: If the pool tests negative, all n individuals are declared negative. If positive, proceed to the next stage.

3. Halving and Sub-Pool Testing

- Stage 2: Split the positive initial pool into two sub-pools of size n/2 (e.g., 4 and 4).

- Test each sub-pool individually.

- Stage 3: For any sub-pool that tests positive, split it again into two further sub-pools of size n/4 (e.g., 2 and 2). Test these new sub-pools.

- Individual Testing: The positive sub-pools from the final halving step (size 2) are resolved by testing each of the two remaining individuals separately.

Halving Procedure Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Item | Function / Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| TaqMan MGB Probe Assays | Highly specific and sensitive real-time PCR probes. The Minor Groove Binder (MGB) increases the melting temperature (Tm) allowing for better discrimination between similar sequences. | Discriminating between the BoLA-DRB3*009:02 allele and other closely related alleles in cattle [16]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | A DNA polymerase with proofreading activity to minimize errors during PCR amplification, crucial for accurate genotyping. | Used in the initial conventional PCR step to verify the specificity of designed primers for a new target [16]. |

| Automated Nucleic Acid Extraction System | A system that automates the purification of nucleic acids from raw samples, ensuring high throughput, consistency, and reduced risk of cross-contamination. | Processing hundreds of wildlife blood or tissue samples for high-volume surveillance projects [16]. |

| Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) | Software-based system for tracking and managing samples and their associated data. | Essential for keeping track of complex sample relationships in Array Testing and Halving procedures, ensuring correct decoding of results. |

Array Testing Layout and Decoding

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: My pooled testing results are inconsistent. How can I improve accuracy?

Problem: Inconsistent results from pooled testing protocols in wildlife disease surveillance. Impact: Unreliable prevalence estimates, potentially missing emerging pathogen threats, and wasted laboratory resources. Context: Often occurs when using non-informative procedures (like standard Dorfman testing) on a heterogeneous wildlife population with varying infection risks [6].

Solution Architecture:

- Quick Fix (Time: 5 minutes): Review and refine your pooling strategy. Ensure animals with similar known risk factors (e.g., same species, age class, or sampling location) are grouped into the same pool to reduce heterogeneity [6].

- Standard Resolution (Time: 15 minutes): Switch from a non-informative to an informative pooled testing procedure. Implement Ordered Halving (3H.order or 4H.order), which sorts individuals by estimated risk and creates sub-pools to isolate positives more efficiently [6].

- Root Cause Fix (Time: 30+ minutes): Develop a risk probability model for your study population. Use historical data on species, age, sex, and ecological factors to estimate individual infection probabilities. Apply a sophisticated informative algorithm like Pool-Specific Optimal Dorfman (PSOD) that uses these probabilities to determine optimal pool sizes and compositions [6].

FAQ: How do I handle a positive pool without testing every individual?

Problem: A testing pool returns a positive result, and individual retesting of all members is cost-prohibitive or sample volume is limited. Impact: Inability to identify the specific positive individuals within the pool, leading to incomplete data and potential underestimation of transmission dynamics. Context: A common challenge in large-scale wildlife surveillance where sample materials or test kits are limited [6].

Solution Architecture:

- Quick Fix (Time: 5 minutes): Use the Sterrett procedure. After a pool tests positive, retest individuals one-by-one until the first positive is found. Then, re-pool the remaining untested individuals and repeat the process [6].

- Standard Resolution (Time: 15 minutes): Implement an informative version of the Sterrett procedure (One-Stage or Two-Stage Informative Sterrett). Order individuals within the positive pool by their estimated risk (highest risk first) before beginning individual retesting. This often finds positives with fewer tests [6].

- Root Cause Fix (Time: 30+ minutes): Adopt matrix (array) testing for initial screening. Individuals are assigned to multiple pools (e.g., in a grid), and results are decoded based on the pattern of positive rows and columns, which can identify one or more positives without universal individual retesting [6].

FAQ: My data are not comparable with other wildlife disease studies. What is the issue?

Problem: Collected data on pathogen presence/absence cannot be easily aggregated or compared with datasets from other research groups. Impact: Hinders meta-analyses, ecological synthesis, and global health threat assessment, violating FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) data principles [9] [10]. Context: A systemic issue in wildlife disease ecology often caused by a lack of standardized data and metadata reporting, especially the omission of negative test results and key methodological details [9].

Solution Architecture:

- Quick Fix (Time: 5 minutes): Ensure your dataset includes all individual-level test results, both positive and negative. Do not report only summary statistics [9].

- Standard Resolution (Time: 15 minutes): Adopt a minimum data standard for wildlife disease research. Format your data into a "tidy" rectangular format where each row is a single diagnostic test. Include the 9 required core fields: host identification, diagnostic method, test outcome, parasite identification, and date/location of sampling [9] [10].

- Root Cause Fix (Time: 30+ minutes): Fully implement the wildlife disease data standard. Use the provided templates and validation tools (e.g., JSON Schema, R package) to structure your dataset with all 40 core data fields and 24 metadata fields. Share the complete, standardized dataset in an open-access repository like Zenodo or the PHAROS platform [9].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol: Implementing Informative Dorfman Retesting

Objective: To reduce the number of tests required for pathogen screening in a heterogeneous wildlife population by using risk factors to inform pool construction.

Methodology:

- Risk Probability Estimation: For each individual in the study cohort, estimate a probability of infection (p) using a pre-existing logistic regression model. The model can incorporate risk factors such as host species, age, sex, body condition, and known exposure history [6].

- Ordering and Pool Formation: Order all individuals from highest to lowest estimated risk (p).

- Algorithm Selection:

- Threshold Optimal Dorfman (TOD): Apply a threshold (e.g., p > 0.2). Test high-risk individuals individually. Group the remaining low-risk individuals into pools of optimal size (see table below) [6].

- Pool-Specific Optimal Dorfman (PSOD): Without a threshold, use a greedy algorithm to partition the ordered list of individuals into successive pools of variable sizes that minimize the expected number of tests [6].

- Testing and Decoding:

- Test each formed pool.

- If a pool tests negative, all individuals within it are declared negative.

- If a pool tests positive, all individuals within that pool are tested individually to decode the positive from the negative individuals [6].

Workflow Visualization:

Diagram: Informative Dorfman Retesting Workflow

Quantitative Data Comparison

Table 1: Comparison of Non-Informative and Informative Pooled Testing Procedures [6]

| Procedure | Key Principle | Requires Risk Estimates? | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dorfman | Simple two-stage: pool test, then individual retest if positive. | No | Homogeneous populations; simplest to implement. |

| Halving (3H, 4H) | Iteratively split positive pools into halves for testing. | No | Scenarios where a moderate reduction in tests beyond Dorfman is desired. |

| Sterrett | After a positive pool, test individuals until a positive is found, then re-pool remainder. | No | Populations expected to have very few (often one) positive per pool. |

| Matrix Testing | Individuals assigned to multiple pools in a grid; decode via row/column results. | No | High-throughput screening of many samples. |

| TOD / PSOD | Use risk probabilities to set pool sizes and composition (informed Dorfman). | Yes | Heterogeneous populations with known risk factors (e.g., species, age). |

| Ordered Halving | Halving procedure performed on pools ordered by individual risk. | Yes | Heterogeneous populations where iterative refinement is feasible. |

| Informative Sterrett | Sterrett procedure with individuals ordered by risk for retesting. | Yes | Heterogeneous populations with low prevalence where sequential decoding is efficient. |

Table 2: Essential Data Fields for Standardized Wildlife Disease Reporting [9]

| Field Category | Required Fields (9) | Example Data | Purpose in Informative Retesting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Host Data | Host species, Animal ID (if applicable) | Myotis lucifugus, BZ19-114 | Core variables for stratifying risk and forming informed pools. |

| Sample Data | Sample date, Sample ID, Location (e.g., latitude/longitude) | 2019-03-15, SWAB-001, 17.2500° N, 88.7667° W | Critical spatiotemporal context for estimating risk probabilities. |

| Parasite Data | Test result, Pathogen target, Diagnostic method | Positive, Alphacoronavirus, PCR | The fundamental outcome of the diagnostic test. |

| Additional Context | Host age, Host sex, Diagnostic test citation | Adult, Female, (Smith et al. 2020) | Additional covariates for building accurate risk models. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Pooled Pathogen Screening

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Sample Lysis Buffer | Inactivates pathogens for safe handling and releases nucleic acids or antigens for downstream testing. |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit | Purifies DNA/RNA from composite pool samples or individual samples for PCR-based assays. |

| PCR Master Mix | A pre-mixed solution containing enzymes, dNTPs, and buffer for the amplification of pathogen genetic material. |

| Pathogen-Specific Primers/Probes | Oligonucleotides designed to bind to and detect a specific sequence from the target pathogen. |

| ELISA Kit | Detects pathogen-specific antibodies (serology) or antigens in a sample using an enzyme-linked immunoassay. |

| Risk Factor Data | Pre-existing data on host ecology (species, age, sex) used to estimate infection probability for informative pooling [6]. |

| Data Standard Template | A predefined spreadsheet format (e.g., .csv) with required fields to ensure data is FAIR and reusable [9]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Pooled Testing Issues and Solutions

Issue 1: Loss of Detection Sensitivity in Pooled Samples

- Problem: A known positive sample is not detected when pooled with negative samples, leading to false negatives.

- Cause: Dilution of the target analyte (e.g., viral RNA, prion protein) below the assay's limit of detection [4] [19]. This is more pronounced with larger pool sizes and in samples with low initial analyte concentration.

- Solution:

- Validate Pool Size: Conduct in-house validation to determine the maximum pool size that does not significantly compromise sensitivity for your specific assay and sample type [4] [20]. For SARS-CoV-2, studies have shown that pool sizes of 5:1 often maintain >85% positive percent agreement [20].

- Use More Sensitive Assays: Employ ultra-sensitive assays like RT-QuIC, which can maintain detection even at high pooling thresholds (e.g., 1:49) due to signal amplification [3].

- Adjust Thresholds: For some assays, lowering the positive/negative cut-off threshold can recover sensitivity lost due to pooling [20].

- Concentrate Samples: Use centrifugal filters to concentrate the pooled sample to the maximal volume compatible with a single extraction column, countering the dilution effect [19].

Issue 2: Cross-Contamination and Specimen Mix-Ups

- Problem: Contamination between samples or mislabeling leads to inaccurate results.

- Cause: Manual aliquoting and pipetting steps during pool formation are prone to human error [4].

- Solution:

- Automate the Process: Implement automated liquid handling systems for pool formation. This increases throughput, reduces pipetting errors, and enables automated sample tracking [20].

- Implement Dual-Check Systems: For manual workflows, a two-person verification system for sample labeling and pooling can drastically reduce errors [21].

- Use Barcodes/RFID: Implement a barcode or RFID system to track samples and pools throughout the entire workflow, ensuring accurate identification [21].

Issue 3: Increased Turnaround Time for Positive Results

- Problem: Reporting times for positive individuals are delayed compared to individual testing.

- Cause: The multi-stage nature of pooled testing requires positive pools to be "decoded" through subsequent rounds of individual retesting [4].

- Solution:

- Archive Aliquots: Before creating pools, set aside a portion of every individual sample. If a pool tests positive, the archived aliquots can be tested immediately without recalling individuals, which is time-prohibitive [22].

- Use Efficient Algorithms: Implement informative or hierarchical retesting protocols (e.g., halving, Sterrett's procedure) that minimize the number of retests needed to identify all positives within a positive pool [6].

Issue 4: Inefficient Pool Sizing in Heterogeneous Populations

- Problem: The cost-saving benefits of pooling are not realized because too many pools test positive, requiring full retesting.

- Cause: Using a fixed pool size for a population with a high or variable disease prevalence [22].

- Solution:

- Prevalence-Based Sizing: Use statistical models to calculate the optimal pool size based on the estimated disease prevalence in the population being tested. Pooling is most cost-effective when prevalence is low (e.g., <10%) [22] [23].

- Informative Pooling: Use known risk factors (e.g., species, location, age) to categorize individuals by their probability of being positive. High-risk individuals can be tested in smaller pools or individually, while low-risk individuals are grouped into larger pools, minimizing the number of positive pools [6].

Laboratory Processing and Workflow Challenges

- Challenge: Lack of established infrastructure and software for managing the pooling workflow [4].

- Solution: Utilize Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS) or electronic lab notebooks with specific functionalities for sample pooling. These systems can manage pool construction, track parent-child sample relationships, and guide the deconstruction of positive pools [21] [24].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the single most important factor for successful pooled testing? A1: Low disease prevalence is the most critical factor. When prevalence is low (typically below 10%), the vast majority of pools will test negative, leading to significant savings in reagents and time. As prevalence increases, the number of positive pools rises, making retesting more frequent and less efficient [22] [4] [23].

Q2: How do I determine the optimal pool size for my surveillance project? A2: The optimal pool size is a balance between cost-saving and maintaining detection sensitivity. It depends on:

- Estimated Prevalence: Lower prevalence allows for larger pools.

- Assay Sensitivity: More sensitive assays can tolerate larger pool sizes without loss of detection [3].

- Sample Type and Volume: Ensure each sample still contributes sufficient analyte after dilution. You should perform a validation study using your specific assay and sample matrix to determine the maximum pool size that does not unacceptably reduce sensitivity [4] [20].

Q3: Can I use pooled testing for any disease or pathogen? A3: No. Pooled testing is best suited for screening purposes for infectious diseases in large populations where the expected prevalence is low. It is commonly used for blood-borne pathogens (HIV, Hepatitis), SARS-CoV-2 in low-prevalence areas, and wildlife diseases like Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) [22] [4] [3]. It is less suitable for diagnostic testing in symptomatic, high-prevalence populations.

Q4: What are the key steps in validating a pooled testing protocol in my lab? A4: Key validation steps include [4] [20]:

- Determining Analytical Sensitivity: Compare the limit of detection (LLOD) of your assay for individual samples versus pooled samples at your intended pool size.

- Establishing Percent Positive Agreement: Test a panel of known positive and negative samples individually and in pools to ensure the pooled testing agrees with individual results (the FDA recommends >85% positive agreement for SARS-CoV-2) [20].

- Assaying Specificity: Confirm that negative pools consistently test negative.

- Documenting the Workflow: Fully document the procedures for pool formation, testing, and data analysis to ensure consistency and avoid errors.

Q5: Our pooled testing workflow is too manual and time-consuming. How can we improve it? A5: The primary solution is automation.

- Automated Liquid Handlers: These systems can accurately and rapidly create sample pools, reducing human error and hands-on time [20].

- Digital Management Software: A Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) designed for pooling can automate sample tracking, pool assignment, and result interpretation, streamlining the entire workflow [21] [24].

Experimental Protocols and Data

Detailed Methodology: Validation of Pooling Thresholds for Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD)

This protocol, based on published research, outlines how to evaluate pooling thresholds for wildlife disease surveillance [3].

1. Sample Collection and Preparation

- Sample Type: Medial retropharyngeal lymph nodes (RPLNs) from white-tailed deer.

- Initial Screening: Test all individual "A" samples with a screening test (e.g., ELISA for prion protein). Retain the paired "B" sample frozen.

- Sample Selection: Select confirmed positive and confirmed negative "B" samples for the pooling study. Re-test them individually to confirm their status before pooling.

2. Pool Formation

- Tissue Homogenization: Partially thaw RPLNs and trim connective tissue. For each pool, combine tissue from one positive "spike" sample with tissue from a variable number of negative samples.

- Standardized Contribution: Each individual sample in a pool must contribute an equal tissue mass. For example:

- 1:4 Pool: 100 mg from 1 positive + 100 mg from 4 negatives (total 500 mg).

- 1:9 Pool: 50 mg from 1 positive + 50 mg from 9 negatives (total 500 mg).

- Homogenize the combined tissue in a grinding tube with appropriate buffer.

3. Testing of Pools

- Test the pooled homogenates with the desired assay(s) (e.g., ELISA and/or a more sensitive assay like RT-QuIC).

- For RT-QuIC, a tissue homogenate dilution series (e.g., 0.02%) may be used.

- Record the results (Positive/Negative) and quantitative values (e.g., Optical Density for ELISA, Ct value for PCR).

4. Data Analysis

- Determine the maximum pooling threshold (e.g., 1:4, 1:9, 1:19) at which the assay can consistently detect the positive sample.

- Compare the sensitivity and specificity of different assays under pooled conditions.

Quantitative Data from Pooled Testing Studies

Table 1: Impact of Pool Size on SARS-CoV-2 Assay Performance (Panther Fusion System) [20]

| Pool Size | Positive Percent Agreement (vs. Neat Testing) | Average CT Value Increase | Meets FDA >85% PPA? |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5:1 | >85% | 1.92 - 2.41 CT | Yes |

| 10:1 | Reduced Performance | 3.03 - 3.29 CT | No (for this validation) |

| Key Finding | Pool sizes ≤ 5:1 maintained acceptable diagnostic sensitivity. |

Table 2: Pooling Thresholds for Chronic Wasting Disease Detection [3]

| Assay Type | Tissue Preparation | Maximum Validated Pooling Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| ELISA (TeSeE) | Standard volume tissue homogenate | 1:9 (1 positive in 9 total) |

| RT-QuIC | 0.02% tissue homogenate | 1:49 (1 positive in 49 total) |

| Key Finding | RT-QuIC, an ultra-sensitive amplification assay, allows for significantly larger pool sizes, drastically reducing costs. |

Workflow Visualization

Pooled Testing Decoding Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Pooled Testing in Wildlife Surveillance

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Liquid Handler | Precisely combines individual samples into pools, reducing human error and increasing throughput [20]. | High-volume surveillance of cervids for CWD [3]. |

| Centrifugal Filters | Concentrates diluted pooled samples, helping to counteract analyte dilution and maintain test sensitivity [19]. | SARS-CoV-2 RNA concentration from pooled nasopharyngeal swabs. |

| Sensitive Detection Assays (e.g., RT-QuIC) | Ultra-sensitive assays that can detect low levels of pathogen even after significant dilution in a pool, enabling larger, more cost-effective pool sizes [3]. | CWD prion detection in 1:49 pools of deer lymph nodes [3]. |

| Barcode/RFID System | Provides unique identifiers for samples and pools, ensuring traceability and preventing misidentification throughout the complex workflow [21]. | Tracking thousands of individual and pooled samples in a large-scale study. |

| Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) | Software that manages sample metadata, pool assignments, and results; crucial for tracking the parent-child relationships in pooled testing [21] [24]. | Managing the workflow for a multi-site wildlife disease surveillance program. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)