Optimizing FEA Concentration for Sensitive Detection of Low-Intensity Parasitic Infections in Clinical and Research Settings

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Formalin-Ethyl Acetate (FEA) concentration technique for diagnosing low-intensity intestinal parasitic infections, a critical challenge in drug efficacy trials and surveillance programs.

Optimizing FEA Concentration for Sensitive Detection of Low-Intensity Parasitic Infections in Clinical and Research Settings

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Formalin-Ethyl Acetate (FEA) concentration technique for diagnosing low-intensity intestinal parasitic infections, a critical challenge in drug efficacy trials and surveillance programs. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of FEA, details advanced methodological protocols, and offers troubleshooting strategies to maximize sensitivity. The content further validates FEA's performance against emerging diagnostic platforms, including molecular assays like qPCR and automated digital systems, synthesizing evidence to guide optimal method selection for high-stakes clinical research and public health initiatives.

The Critical Challenge of Low-Intensity Parasitic Infections and the Role of FEA Concentration

Defining Low-Intensity Infections and Their Impact on Morbidity and Drug Efficacy Trials

The accurate definition and assessment of low-intensity infections are critical for advancing research and development of new anti-parasitic compounds, including Fixed-Dose Combination (FDC) formulations. In parasitology, infection intensity refers to the quantitative measure of parasite burden within a host, typically measured by egg excretion rates in stool or urine samples [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has established classification systems to categorize infection intensity, which serve as important tools for guiding public health decisions and mass drug administration programs [1]. However, traditional intensity categories do not always correlate well with morbidity outcomes, particularly for certain parasite species, creating challenges for clinical trial endpoints and drug efficacy assessments [1].

Within the context of FDC development for low-intensity parasitic infections, understanding these relationships becomes paramount. This application note provides a structured framework for defining low-intensity infections, summarizes their variable impact on morbidity across different parasitic diseases, and outlines optimized experimental protocols for drug efficacy trials in this specific context.

Quantitative Definitions of Low-Intensity Infections

The WHO has established standardized intensity classifications for major human helminth infections, which are essential for harmonizing research methodologies and interpreting trial results across different epidemiological settings [1].

Table 1: WHO Infection Intensity Categories for Key Helminth Infections

| Parasite Species | Diagnostic Method | Intensity Category | Quantitative Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schistosoma haematobium | Urine filtration (eggs/10ml) | Light | 1–49 eggs/10 ml urine [1] |

| Heavy | ≥50 eggs/10 ml urine [1] | ||

| Schistosoma mansoni | Kato-Katz (eggs per gram - EPG) | Light | 1–99 EPG [1] |

| Moderate | 100–399 EPG [1] | ||

| Heavy | ≥400 EPG [1] |

The relationship between these intensity categories and clinical morbidity is not consistent across parasite species. For S. haematobium, even light infections are associated with significant morbidity, including urinary bladder lesions, microhematuria, and pain during urination [1]. In contrast, for S. mansoni, the established intensity categories show a weaker correlation with morbidity indicators such as irregular hepatic ultrasound patterns, enlarged portal vein, or diarrhea in school-age children [1]. This discrepancy has profound implications for selecting primary endpoints in clinical trials.

Core Experimental Protocols for Morbidity and Drug Efficacy Assessment

Protocol 1: Traditional Microscopy for Infection Intensity and Cure Rate (CR)

This protocol outlines the standard method for baseline infection intensity determination and the calculation of Cure Rate (CR), a traditional efficacy endpoint.

Principle: Visualization and quantification of parasite eggs in patient samples using concentration and microscopic examination techniques.

Materials:

- Urine Filtration Kit: For S. haematobium; includes syringes, filter holders, and nylon filters [1].

- Kato-Katz Kit: For S. mansoni and Soil-Transmitted Helminths (STHs); includes template, cellophane strips soaked in glycerol-malachite green, and microscope slides [1].

- Light Microscope:

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Collect a single 10ml urine sample for S. haematobium or a single stool sample for S. mansoni/STHs [1].

- Processing:

- Calculation:

- Egg Count: For S. haematobium, report as eggs/10ml urine. For S. mansoni, multiply the egg count by 24 to obtain Eggs Per Gram (EPG) of stool [1].

- Cure Rate (CR): Calculate as the percentage of baseline-infected subjects diagnosed as egg-negative at a defined post-treatment time point (e.g., 21 days) [2].

Notes: A major limitation of this method is its low sensitivity, especially for detecting low-intensity infections and assessing CR after treatment when egg output is significantly reduced [2].

Protocol 2: Molecular Monitoring of Drug Efficacy and Resistance

This protocol describes a qPCR-based method for more sensitive assessment of infection intensity and the detection of molecular markers associated with anthelmintic resistance.

Principle: Quantitative detection of parasite-specific DNA and Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with benzimidazole resistance.

Materials:

- DNA Extraction Kit: For stool or urine samples.

- qPCR Thermocycler:

- Primers/Probes: Specific for target parasite DNA (e.g., Ascaris lumbricoides, Necator americanus, Trichuris trichiura) [2].

- Assays for SNP Detection: e.g., Pyrosequencing, SmartAmp, or RFLP-PCR for detecting β-tubulin mutations (F167Y, E198A, F200Y) [2].

Procedure:

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract total DNA from patient samples collected pre- and post-treatment.

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR):

- Run samples in multiplex qPCR assays for relevant parasites.

- Use standard curves to convert cycle threshold (Ct) values into quantitative measures of parasite load [2].

- Data Analysis:

- Infection Intensity Reduction Rate: Calculate the percentage reduction in parasite DNA load from pre- to post-treatment, analogous to ERR [2].

- SNP Genotyping: Perform genotyping assays on positive samples to detect and quantify the frequency of known resistance-associated SNPs (e.g., F200Y in T. trichiura) [2].

Notes: qPCR offers significantly higher sensitivity than microscopy, allowing for more accurate detection of light infections and true treatment failures. Monitoring for resistance markers is crucial for understanding the long-term efficacy of anthelmintics, including components of FDCs [2].

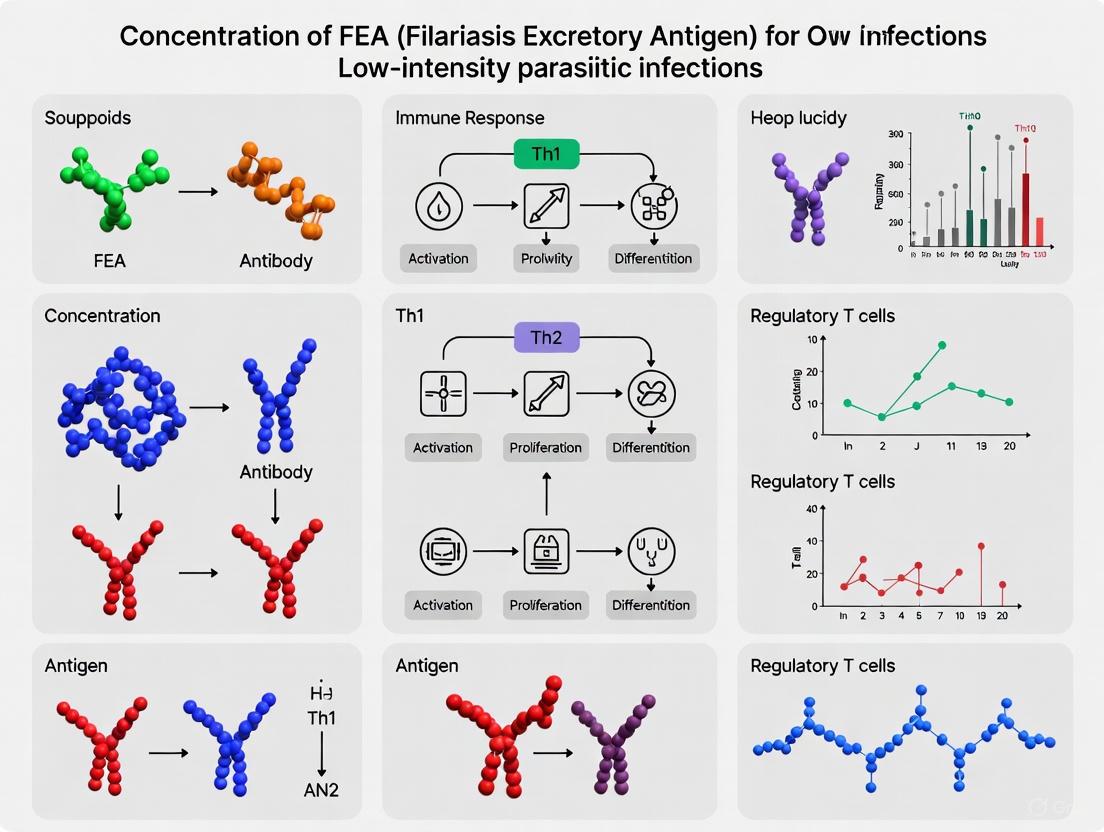

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Drug Efficacy Trial Workflow

Diagram 2: Molecular Detection of Benzimidazole Resistance

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Low-Intensity Infection Research

| Item | Primary Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Kato-Katz Kit | Quantification of STH and S. mansoni eggs per gram (EPG) of stool. | The standard for field-based intensity measurement. Low sensitivity in low-intensity/post-treatment settings is a key limitation [1] [2]. |

| Urine Filtration Kit | Quantification of S. haematobium eggs per 10ml of urine. | Essential for classifying urogenital schistosomiasis intensity per WHO guidelines [1]. |

| qPCR Assays | Quantitative detection of parasite-specific DNA. | Higher sensitivity for detecting light infections and monitoring treatment response. Allows for species differentiation [2]. |

| Pyrosequencing Assays | Detection and quantification of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs). | Used for monitoring frequency of benzimidazole resistance markers (e.g., β-tubulin SNPs) in parasite populations [2]. |

| Benzimidazoles (Albendazole/Mebendazole) | Broad-spectrum anthelmintics; also induce selection pressure. | Used in efficacy trials and mass drug administration. Their use is a driver for selecting resistant genotypes, necessitating monitoring [2]. |

| Praziquantel | Primary drug for treating schistosomiasis. | Used for efficacy trials and preventive chemotherapy against schistosome infections [1]. |

For researchers and drug development professionals working on low-intensity parasitic infections, the choice of diagnostic technique is paramount. Direct smear microscopy, a foundational parasitological method, demonstrates significant limitations in low-burden scenarios, which are a critical focus for evaluating drug efficacy in intervention studies. This application note details the performance gap between direct smear examinations and fecal concentration techniques, providing quantitative data and standardized protocols to underscore the necessity of advanced methods like the Formol-Ethyl Acetate Concentration (FAC) for sensitive detection and accurate quantification in research settings.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The sensitivity of a diagnostic method is its most critical parameter in low-burden infection research. The following table summarizes the performance of various microscopy techniques as reported in recent comparative studies.

Table 1: Comparative Sensitivity of Microscopy Techniques for Parasite Detection

| Diagnostic Technique | Reported Sensitivity (%) | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Wet Mount | 41% (Overall) [3] | Rapid, low-cost, detects motile parasites [4] [5] | Low sensitivity; affected by low infection intensity and intermittent egg excretion [4] | [3] |

| Formol-Ether Concentration (FEC) | 62% (Overall) [3] | Better sensitivity than direct smear; good for protozoal cysts [6] | Lower recovery rate compared to FAC [3] | [3] |

| Formol-Ethyl Acetate Concentration (FAC) | 75% (Overall) [3] | Highest recovery rate for diverse parasites; safer and more feasible in rural labs [3] | Requires centrifugation and specific reagents [3] | [3] |

| Kato-Katz | 67.5% (Accuracy) [6] | Allows egg quantification (EPG); WHO-recommended for STH [4] | Low sensitivity for low-intensity infections and Strongyloides [4] | [6] |

| Mini-FLOTAC | N/A (Specific data not provided) | Allows egg quantification; accurate for helminths [6] | Requires specific equipment [6] | [6] |

Experimental Protocols for Critical Methods

Protocol: Direct Fecal Smear (The Standard of Comparison)

Principle: A thin smear of fresh feces is examined microscopically to identify parasite eggs, larvae, or cysts [5].

Materials:

- Fresh stool sample

- Sterile saline (0.9% NaCl)

- Microscope slides and coverslips

- Iodine solution (e.g., Lugol's iodine)

- Microscope

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Place a drop of saline and a drop of iodine on a clean glass slide [6].

- Sampling: Using a toothpick or applicator stick, take a small (1-2 mg) portion of feces, preferably from an area with mucus or blood [5].

- Emulsification: Thoroughly emulsify the fecal sample in the saline and iodine drops.

- Coverslipping: Place a coverslip over each preparation.

- Microscopy: Examine the entire coverslip area systematically under 10x and 40x objectives. The saline preparation is used to observe motile trophozoites, while the iodine preparation stains protozoan cysts for easier identification [6].

- Interpretation: Identify parasites based on morphological characteristics. A negative result is inconclusive and should be followed by a concentration technique [5].

Protocol: Formol-Ethyl Acetate Concentration (FAC) Technique

Principle: Formalin fixes the parasitic elements, while ethyl acetate dissolves fats and debris, concentrating parasites into a sediment for superior detection [3].

Materials:

- Stool sample (approx. 1 g)

- 10% Formalin (Formol saline)

- Ethyl acetate

- Gauze or sieve

- Conical centrifuge tubes (15 mL)

- Centrifuge

- Microscope slides and coverslips

Procedure:

- Emulsification: Emulsify approximately 1 g of stool in 7 mL of 10% formalin in a centrifuge tube. Fix for 10 minutes [3].

- Filtration: Pour the suspension through a sieve or three layers of gauze into a second centrifuge tube to remove large debris [3].

- Solvent Addition: Add 3 mL of ethyl acetate to the filtrate. Securely stopper the tube and shake vigorously for 30 seconds [3].

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 1500 rpm (approx. 500 x g) for 5 minutes. This will yield four layers: a sediment containing parasites, a formalin layer, a debris plug, and an ethyl acetate layer at the top [3].

- Separation: Loosen the debris plug from the tube walls and carefully decant the top three layers.

- Examination: Use a pipette to resuspend the remaining sediment. Transfer a drop to a microscope slide, apply a coverslip, and examine under 10x and 40x objectives [3].

Workflow Visualization: Direct vs. Concentration Method

The logical relationship and procedural differences between the direct and concentration techniques are mapped in the diagram below, highlighting critical points of sensitivity loss and enhancement.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Fecal Parasitology Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Protocol | Research Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| 10% Formalin (Formol Saline) | Fixes parasitic elements (cysts, eggs), preserving morphology and preventing degradation [3]. | Essential for preserving sample integrity, especially when processing is delayed. Ensures standardized starting material. |

| Ethyl Acetate / Diethyl Ether | Acts as a lipid solvent and debris extractor. Reduces interfering fecal matter, concentrating parasites in the sediment [3]. | Ethyl acetate is generally preferred over ether due to its lower flammability and safer profile, enhancing lab safety [3]. |

| Zinc Sulfate (Sp. Gr. 1.18-1.20) | Flotation fluid for centrifugal flotation techniques. Creates a density gradient that buoys parasites for recovery [5]. | Particularly useful for recovering Giardia cysts and delicate helminth larvae with minimal distortion [5]. |

| Saline & Iodine Solution | Basic media for direct smears. Saline maintains trophozoite motility; iodine stains cyst nuclei and internal structures [6] [5]. | A fundamental, rapid qualitative check. Iodine staining is critical for differentiating protozoan cyst species. |

| Centrifuge | Enables sedimentation of parasites through rapid acceleration, a cornerstone of concentration methods [3] [5]. | Critical for maximizing parasite yield. Standardization of speed and time (e.g., 1500 rpm for 5 min) is key to reproducible results [3]. |

The evidence clearly demonstrates that direct smear microscopy is an inadequate standalone tool for research on low-burden parasitic infections. Its characteristically low sensitivity, as quantified in Table 1, poses a significant risk of generating false-negative data, thereby compromising the assessment of infection prevalence and, crucially, the evaluation of drug efficacy in clinical trials. The adoption of standardized concentration protocols, particularly the Formol-Ethyl Acetate Concentration technique, is non-negotiable for generating reliable, reproducible, and quantitatively accurate data. For research aimed at disease elimination and sensitive drug monitoring, integrating these sensitive morphological techniques with emerging molecular tools represents the most robust path forward.

Finite Element Analysis (FEA) represents a transformative approach in diagnostic parasitology, enabling significant enhancements in detection sensitivity for low-intensity parasitic infections. This computational method allows researchers to model and optimize the physical processes involved in parasite concentration techniques, moving beyond traditional trial-and-error approaches. By applying FEA to the design of diagnostic devices and protocols, scientists can precisely analyze factors such as fluid dynamics, sediment behavior, and force distribution during sample processing. The resulting optimizations lead to improved recovery rates of parasitic elements from clinical specimens, directly addressing the critical need for reliable detection in cases with low parasitic burden, which is essential for both accurate patient management and large-scale epidemiological research.

The Scientific Basis of Concentration-Enhanced Sensitivity

The Challenge of Low-Intensity Infections

The accurate detection of low-intensity parasitic infections remains a formidable challenge in global public health. Traditional manual microscopy, while considered a gold standard, exhibits significant limitations in sensitivity, particularly when parasitic load is minimal. A large-sample retrospective study demonstrated that manual microscopy methods achieved a parasite detection level of only 2.81% (1,450 out of 51,627 cases), highlighting the critical need for enhanced concentration and detection methodologies [7]. These limitations are further compounded by the subjective nature of manual interpretation, biosafety risks, and procedural cumbersomeity, driving the development of advanced concentration protocols and automated detection systems [7].

FEA as a Solution for Protocol Optimization

Finite Element Analysis addresses these challenges by providing researchers with sophisticated computational tools to model and optimize the physical processes underlying parasite concentration techniques. FEA enables the virtual simulation of complex phenomena including fluid dynamics, particle sedimentation, filtration efficiency, and force distribution within sample processing devices. For example, researchers can utilize FEA to model the flow paths and sedimentation patterns of parasitic elements within centrifugation systems, allowing for the optimization of parameters such as rotational speed, tube geometry, and fluid properties to maximize recovery yield [8] [9]. This computational approach minimizes reliance on resource-intensive empirical optimization, accelerating the development of highly sensitive diagnostic protocols tailored to the specific physical characteristics of target parasites.

Quantitative Evidence: FEA-Enhanced Detection Performance

Substantial evidence demonstrates that methodologies developed through FEA principles significantly outperform traditional approaches in parasite detection. The following table summarizes key performance comparisons between advanced systems utilizing concentration enhancements and conventional microscopy:

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Advanced Detection Systems vs. Traditional Microscopy

| Detection Method | Parasite Detection Level | Number of Parasite Species Detected | Key Performance Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|

| KU-F40 Fully Automated Fecal Analyzer | 8.74% (4,424/50,606 cases) [7] | 9 species [7] | χ² = 1661.333, P < 0.05 [7] |

| Traditional Manual Microscopy | 2.81% (1,450/51,627 cases) [7] | 5 species [7] | Reference baseline [7] |

| Deep-Learning Models (DINOv2-large) | Accuracy: 98.93%; Sensitivity: 78.00% [10] | Multiple helminths and protozoa [10] | Specificity: 99.57%; F1 score: 81.13% [10] |

| AI-Assisted Wet-Mount Analysis | 94.3% agreement pre-resolution; 98.6% after resolution [11] | 27 different parasites trained [11] | Detected more organisms at lower dilutions than human technologists [11] |

The implementation of a KU-F40 fully automated fecal analyzer, which incorporates principles of fluid dynamics and particle analysis analogous to FEA optimization, demonstrated a 3.11-fold increase in sensitivity compared to traditional manual microscopy [7]. This system achieved particularly significant improvements in detecting Clonorchis sinensis eggs, hookworm eggs, and Blastocystis hominis (P < 0.05) [7]. Similarly, artificial intelligence platforms leveraging enhanced imaging and analysis detected 169 additional organisms in validation specimens that were not initially identified through conventional methods [11].

Table 2: Statistical Performance Metrics of Advanced Detection Models

| Model/System | Precision | Sensitivity/Recall | Specificity | F1 Score | AUROC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DINOv2-large [10] | 84.52% | 78.00% | 99.57% | 81.13% | 0.97 |

| YOLOv8-m [10] | 62.02% | 46.78% | 99.13% | 53.33% | 0.755 |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) [11] | 94.3% agreement | 250/265 positive specimens | 94/100 negative specimens | N/A | N/A |

Experimental Protocols for FEA-Enhanced Parasite Detection

Protocol 1: Automated Fecal Analysis Using KU-F40 System

Principle

This protocol utilizes a fully automated fecal analyzer that employs flow counting chambers and image analysis to detect and identify parasitic elements in stool specimens. The system optimizes sample processing through controlled dilution, mixing, and filtration parameters that can be enhanced through FEA modeling of fluid dynamics and particle settlement [7].

Materials and Reagents

- KU-F40 fully automatic fecal analyzer (Zhuhai Keyu Biological Engineering Co., Ltd.)

- Specialized sample collection cups

- Compatible reagents and diluents

- 0.9% saline solution

- Standardized fecal sample (soybean-sized, approximately 200 mg)

Procedure

- Sample Collection: Collect fresh fecal specimen in a clean, sterile container. For optimal results, prioritize sampling areas containing mucus, pus, or blood if present.

- Instrument Setup: Initialize the KU-F40 analyzer according to manufacturer specifications, ensuring proper calibration of imaging systems and fluidics.

- Automated Processing:

- Place the sample container in the designated instrument bay.

- The instrument automatically dilutes, mixes, and filters the specimen.

- 2.3 ml of the diluted fecal sample is drawn into a flow counting chamber.

- Allow for precipitation over the instrument-defined period.

- Image Acquisition and Analysis:

- High-definition cameras capture multiple field images of the sample.

- Artificial intelligence algorithms identify potential parasitic elements based on morphological characteristics.

- Manual Review: Technicians review suspected parasites (eggs) before result verification.

- Result Interpretation: Final report generation with parasite identification and quantification.

Quality Control

- Process all samples within 2 hours of collection to preserve parasite morphology.

- Perform regular instrument maintenance according to manufacturer guidelines.

- Implement proficiency testing with known positive and negative samples.

Protocol 2: Deep-Learning Enhanced Wet-Mount Microscopy

Principle

This protocol combines traditional wet-mount microscopy with advanced deep-learning algorithms to enhance detection sensitivity for intestinal parasites. The convolutional neural network (CNN) model is trained on diverse parasite morphologies to assist in identification and classification [11] [10].

Materials and Reagents

- Microscope with digital imaging capability

- Slide preparation system

- Formalin-ethyl acetate centrifugation reagents

- Merthiolate-iodine-formalin (MIF) staining solution

- Deep-learning platform (CIRA CORE or equivalent)

- Training dataset of parasite images

Procedure

- Sample Preparation:

- Process stool specimens using formalin-ethyl acetate centrifugation technique (FECT).

- Prepare concentrated wet mounts according to standard protocols.

- Alternatively, use MIF technique for fixation and staining.

- Digital Imaging:

- Capture digital images of wet mounts using standardized microscopy parameters.

- Ensure adequate image resolution and field diversity.

- AI Analysis:

- Upload images to the deep-learning platform.

- Implement state-of-the-art models (YOLOv4-tiny, YOLOv7-tiny, YOLOv8-m, ResNet-50, or DINOv2).

- Generate preliminary classifications based on trained algorithms.

- Validation and Adjudication:

- Technologists review AI-generated classifications.

- Perform discrepant analysis through scan review and additional microscopy as needed.

- Finalize results incorporating both AI and expert technologist input.

Quality Control

- Validate model performance with unique holdout sets.

- Monitor algorithm performance with ongoing proficiency testing.

- Maintain inter-observer agreement statistics (>0.90 k score recommended).

Visualization of FEA-Enhanced Parasite Detection Workflow

FEA-Enhanced Parasite Detection Workflow: This diagram illustrates the comparative pathway between traditional microscopy and FEA-enhanced detection systems, demonstrating the significant improvement in sensitivity achieved through optimized protocols.

Research Reagent Solutions for Enhanced Parasite Detection

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for FEA-Enhanced Parasite Detection

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Formalin-Ethyl Acetate Solution | Preserves parasite morphology and facilitates concentration | Standard concentration protocol for wet-mount preparation [11] [10] |

| Merthiolate-Iodine-Formalin (MIF) | Fixation and staining solution for enhanced visualization | Field surveys and resource-limited settings [10] |

| Sodium Hydroxide (14M) and Sodium Silicate | Alkali activation for structural analysis | Geopolymer concrete modeling in FEA validation studies [9] |

| Zhuhai Keyu KU-F40 Reagents | Automated dilution, mixing, and filtration | Fully automated fecal analysis systems [7] |

| Deep-Learning Training Datasets | Algorithm training and validation | AI-assisted parasite identification platforms [11] [10] |

The integration of Finite Element Analysis principles into parasitology diagnostics represents a significant advancement in the detection of low-intensity parasitic infections. Through the optimization of concentration protocols and the development of advanced analytical systems, FEA-enhanced methodologies demonstrate marked improvements in sensitivity, specificity, and operational efficiency compared to traditional microscopy. The quantitative evidence presented confirms that these approaches can increase detection rates by more than threefold while expanding the range of detectable parasite species. For researchers and drug development professionals, these advancements offer powerful tools for more accurate epidemiological surveillance, clinical trial monitoring, and treatment efficacy assessment. The continued refinement of these protocols, particularly through the integration of computational modeling and artificial intelligence, promises to further enhance diagnostic capabilities in the ongoing effort to control and eliminate parasitic diseases globally.

Epidemiological and Clinical Significance of Detecting Subpatent Infections

Subpatent infections, characterized by parasite densities below the detection limit of routine diagnostic tests such as microscopy and rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs), present a formidable challenge to global malaria control and elimination efforts [12] [13]. These infections contribute significantly to the infectious reservoir, sustain transmission cycles, and undermine intervention strategies in target regions [12] [14]. The epidemiological significance of subpatent infections is particularly pronounced in low transmission settings heading toward elimination, where they may constitute the majority of the infected population [13] [15].

The clinical significance of detecting subpatent infections extends beyond their role in transmission. Individuals with subpatent parasitemia may experience chronic morbidity and are at risk of developing future patent infections [13]. Furthermore, the presence of subpatent infections in household members has been shown to maintain malaria burden in vulnerable populations, such as children under seasonal malaria chemoprevention, suggesting that current interventions failing to address this reservoir may achieve suboptimal effectiveness [16].

Within the context of Formalin-Ethyl Acetate (FEA) concentration methods for low-intensity parasitic infections research, this application note provides a comprehensive framework for detecting, quantifying, and understanding subpatent infections, with specific protocols and data analysis approaches tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Quantitative Epidemiology of Subpatent Infections

Prevalence Across Transmission Settings

Table 1: Prevalence of Subpatent Plasmodium falciparum Infections Across Transmission Settings

| Location | Transmission Stratum | Overall Infection Prevalence (%) | Subpatent Infection Prevalence (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mainland Tanzania (14 regions) | High | - | - | [12] |

| - | Moderate | - | - | [12] |

| - | Low | - | 29.4 | [12] |

| - | Very Low | - | 13.0 | [12] |

| Burkina Faso (Nanoro District) | High | 68.6 | 41.2 | [16] |

| Southern Zambia | Pre-elimination | 2.6 | 47.0* | [14] |

| Proportion of all infections that were subpatent |

Subpatent infections are a consistent feature across all malaria transmission settings, with notable variations in their distribution and contribution to the overall infected reservoir. In Mainland Tanzania, the prevalence of subpatent infections exhibits a clear relationship with transmission intensity, ranging from 13.0% in very low transmission areas to 29.4% in low transmission strata [12]. This paradoxical pattern—where lower transmission settings harbor a higher proportion of subpatent infections among the infected population—highlights the critical challenge these infections pose for elimination campaigns.

In Burkina Faso's Nanoro Health District, a high-transmission region implementing seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC), subpatent infections accounted for 41.2% of all infections detected in household members of protected children [16]. This substantial reservoir among individuals not targeted by SMC likely contributes to the persistent transmission observed despite intervention efforts. The age distribution of these infections revealed distinct patterns, with patent infections declining with age (37.7% in 5-14 years to 17.1% in ≥25 years), while subpatent infections peaked in young adults (49.2% in 15-24 years) [16].

In pre-elimination settings such as southern Zambia, the proportion of infections that are subpatent can be exceptionally high. A study conducted between 2008-2013 found that 47% of all malaria infections were subpatent, with most (85%) being asymptomatic [14]. This population serves as a persistent reservoir that evades routine surveillance and treatment efforts.

Parasite Density and Diagnostic Sensitivity

Table 2: Diagnostic Performance Against Subpatent Infections

| Diagnostic Method | Limit of Detection (parasites/μL) | Sensitivity for Subpatent Infections | Sample-to-Result Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional RDT | 100-200 | 4.7-49.6% | 15-20 minutes |

| Expert Microscopy | 50-100 | 0-70.1% | 30-60 minutes |

| varATS qPCR | 0.03 | 100% (reference) | Several hours |

| LAMP-based Platform | 0.6 | 94.9-95.2% | <45 minutes |

| FEA Concentration + Microscopy | Varies by parasite | Significantly superior to FC | 30-45 minutes |

The parasite density of subpatent infections typically falls below 100 parasites/μL, with median densities in asymptomatically infected populations ranging from 1 to 1336 parasites/μL across different transmission settings [13]. This density distribution has profound implications for diagnostic sensitivity. Analyses of multiple datasets reveal that at a parasite density of 100 parasites/μL, the probability of detection by microscopy ranges from 3.8% to 69.7% across studies, with a median of 29.7% [13].

Molecular methods offer significantly enhanced sensitivity for detecting subpatent infections. A recently developed near point-of-care LAMP-based diagnostic platform demonstrated a limit of detection of 0.6 parasites/μL, detecting 94.9% of asymptomatic infections and 95.3% of submicroscopic cases, substantially outperforming both expert microscopy (70.1% and 0%, respectively) and RDTs (49.6% and 4.7%, respectively) [15].

For intestinal parasites, the Formalin-Ethyl Acetate Concentration Technique (FECT) has shown superior detection capability compared to formalin-based concentration methods alone. In a comparative study of 693 fecal samples, FECT detected significantly more infections with hookworm (145 vs. 89), Trichuris trichiura (109 vs. 53), and small liver flukes (85 vs. 39) [17].

Diagnostic Workflows and Methodologies

Integrated Diagnostic Pathway for Subpatent Infections

This diagnostic pathway illustrates the integrated approach necessary for comprehensive detection of subpatent infections. The critical branching point occurs after initial RDT screening, where RDT-negative samples require further molecular analysis to identify the subpatent reservoir [12] [16].

Molecular Detection of Subpatent Malaria Infections

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

Protocol: Tween-Chelex DNA Extraction from Dried Blood Spots (DBS)

- Sample Preparation: Punch three 6mm discs from DBS collected on Whatman 3MM filter paper and place in a 1.5mL microcentrifuge tube [12].

- Cell Lysis: Add 1mL of 0.5% Tween-20 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubate overnight on a shaker at room temperature [12].

- Washing: Remove supernatant after incubation and wash with 1× PBS [12].

- DNA Extraction: Add Chelex 100 resin, vortex, and boil at 95°C for 10-15 minutes [12] [16].

- DNA Recovery: Centrifuge at high speed (13,000-15,000 rpm) for 2 minutes and transfer 150μL of supernatant containing DNA to a clean tube [12].

- Storage: Store extracted DNA at -20°C until use in PCR assays [12].

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) forPlasmodium falciparum

Protocol: varATS qPCR Assay

- Principle: This assay targets the var gene acidic terminal sequence (varATS) with high sensitivity, achieving a limit of detection of 0.03 parasites/μL [16].

- Reaction Setup:

- Template DNA: 2-5μL

- varATS-specific primers: Forward and reverse as published

- Probe: FAM-labeled for detection

- qPCR master mix: Commercial preparation suitable for SYBR Green or probe-based detection

- Thermocycling Conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 5 minutes

- 45 cycles of: 95°C for 15 seconds (denaturation), 60°C for 1 minute (annealing/extension)

- Signal acquisition at the end of each cycle

- Quantification: Include standard curves with known parasite densities for absolute quantification [16].

Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP)

Protocol: Near Point-of-Care LAMP Detection

- Sample Preparation: Use 100μL of EDTA-anticoagulated whole blood with proteinase K lysis at 65°C for 5 minutes [15].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Employ magnetic bead-based extraction (SmartLid technology) transferring beads through multiple buffers for purification [15].

- Amplification Setup:

- Use lyophilized colorimetric LAMP chemistry

- Target: pan-Plasmodium and P. falciparum-specific genes

- Incubate at constant temperature (65°C) for 30-45 minutes in a dry-bath heat block [15].

- Result Interpretation: Visual color change from pink (negative) to yellow (positive) [15].

- Performance: This method achieves 95.2% sensitivity and 96.8% specificity compared to qPCR, with sample-to-result time under 45 minutes [15].

Formalin-Ethyl Acetate Concentration Technique (FECT) for Intestinal Parasites

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Subpatent Infection Detection| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | Tween-Chelex method [12], Magnetic bead-based kits (SmartLid) [15] | DNA extraction from DBS and whole blood | Tween-Chelex: Cost-effective for high-throughput studies; Magnetic beads: Faster, suitable for near point-of-care |

| Amplification Reagents | varATS qPCR primers/probes [16], Colorimetric LAMP kits [15] | Molecular detection of low-density infections | varATS qPCR: LOD 0.03 parasites/μL; LAMP: LOD 0.6 parasites/μL, field-deployable |

| Microscopy Enhancements | Formalin-Ethyl Acetate (FEA) [17], CONSED Sedimentation Reagent [18] | Concentration of parasitic elements in fecal samples | FEA significantly superior to formalin concentration for hookworm, T. trichiura, and small liver flukes |

| Sample Preservation | Whatman 903 filter paper (DBS) [14], Proto-fix [18], 10% Formalin [17] | Preservation of samples for downstream analysis | DBS ideal for molecular studies in remote settings; Proto-fix effective for morphology and concentration |

| Rapid Diagnostics | HRP2-based RDTs (SD Bioline, CareStart) [12] | Initial screening to identify RDT-negative, potentially subpatent infections | LOD ~100-200 parasites/μL; useful for triaging samples for molecular testing |

Research Implications and Applications

The detection and characterization of subpatent infections have profound implications for malaria control and elimination strategies. The high prevalence of subpatent infections across all transmission settings, particularly in low transmission areas and among specific demographic groups, indicates that routine diagnostic approaches are insufficient for elimination campaigns [12] [13] [14].

From a clinical perspective, subpatent infections represent a reservoir for continued transmission and potential future clinical episodes. The finding that approximately one quarter of individuals with subpatent parasitemia harbor detectable gametocytes underscores their importance in sustaining transmission [14]. Furthermore, the high prevalence of subpatent infections in household members of children under SMC coverage (41.2% in Burkina Faso) demonstrates how this reservoir maintains transmission to vulnerable populations [16].

For drug development professionals, subpatent infections present both challenges and opportunities. The unique biological state of low-density infections may differ in drug susceptibility and metabolic activity, requiring specialized assays for drug screening. The development of single-dose radical cure regimens effective against subpatent infections would significantly advance elimination efforts.

From a methodological perspective, the integration of sensitive detection methods into research protocols is essential for accurate endpoint measurement in intervention trials. The superior sensitivity of FEA concentration techniques for intestinal helminths [17] and molecular methods for malaria [15] [16] suggests that these should be incorporated as standard procedures in clinical trials and epidemiological studies aiming to measure intervention impact on transmission endpoints.

Subpatent infections represent a critical challenge and opportunity for disease control programs. Their detection requires specialized methodologies that exceed the sensitivity of routine diagnostics, including molecular techniques for malaria and concentration methods for intestinal parasites. The epidemiological significance of these infections is particularly pronounced in low transmission settings and among specific demographic groups, who may serve as reservoirs for continued transmission.

The protocols and methodologies outlined in this application note provide researchers with the tools to accurately detect and quantify subpatent infections, enabling more effective surveillance strategies and intervention assessments. As elimination efforts intensify, addressing the subpatent reservoir will be essential for achieving sustained success, necessitating the integration of these enhanced detection methods into both research and public health practice.

Mastering the FEA Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide for Maximum Parasite Recovery

Intestinal parasitic infections (IPIs), particularly those of low intensity, present a significant challenge in both clinical diagnostics and public health research. Accurate detection is crucial for effective disease management, drug efficacy studies, and understanding true infection prevalence. The Formol-Ether Acetate Concentration Technique (FECT), a type of fecal egg counting technique (FEA), is a standardized parasitological method designed to enhance the recovery of parasites, cysts, and eggs from stool specimens [3]. This protocol details a standardized procedure for FECT, from sample emulsification through microscopic examination of sediment, specifically framed within research on low-intensity infections where sensitivity is paramount.

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists the essential materials and reagents required for the successful execution of the FECT protocol.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for FECT

| Item Name | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| 10% Formol Saline | Serves as a fixative and preservative, maintaining the structural integrity of parasites and eliminating microbial activity. |

| Diethyl Ether | A lipid solvent that dissolves and removes fecal fats, debris, and other unwanted organic matter, clearing the sample. |

| Ethyl Acetate | An alternative solvent to ether; acts as a fat solvent and detergent, aiding in the removal of debris and concentration of parasites [3]. |

| Sterile Wide-Mouth Containers | Used for stool sample collection and transport; wide mouth facilitates easy sample placement. |

| Gauze or Sieve (3-layer) | Used to filter and remove large, coarse particulate matter from the emulsified stool sample. |

| Conical Centrifuge Tubes (15 mL) | Tubes used for the concentration steps, allowing for the distinct layering of solvents and sediment after centrifugation. |

| Centrifuge | A critical instrument for sedimenting parasitic elements by applying centrifugal force, separating them from the supernatant. |

| Microscope Slides & Cover Slips | For preparing the sediment for microscopic examination. |

Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide

Sample Preparation and Emulsification

- Collection: Collect approximately 1-2 grams of fresh stool specimen in a sterile, wide-mouth, leak-proof plastic container [3].

- Emulsification: Transfer about 1 gram of the stool specimen to a clean conical centrifuge tube. Add 7 mL of 10% formol saline to the specimen and mix thoroughly to create a homogenous emulsion. Allow the mixture to fix for 10 minutes [3].

- Filtration: Pour the emulsified mixture through three layers of wet gauze or a specialized sieve into a clean 15 mL conical centrifuge tube. This step removes large, undigested food particles and fibers.

Concentration Technique

- Solvent Addition: To the filtered filtrate, add 3 mL of ethyl acetate (or 4 mL of diethyl ether). Securely cap the tube and shake it vigorously for at least 10 seconds to ensure thorough mixing of the solvent with the fecal suspension [3].

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the tube at 1500 rpm for 5 minutes (or at 300 rpm for 1 minute, depending on the standardized protocol followed). This step creates four distinct layers [3]:

- Top Layer: A plug of debris and dissolved fats in the solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate or ether).

- Intermediate Layer: The formol saline.

- Bottom Layer: The sediment containing the concentrated parasitic elements.

- Debris Plug: At the interface between the solvent and formol saline.

- Separation: Loosen the debris plug by ringing it with an applicator stick. Carefully decant the entire supernatant, including the solvent, formol saline, and the debris plug. The remaining sediment at the bottom of the tube contains the concentrated parasites [3].

Sediment Examination

- Slide Preparation: Using a pipette, resuspend the remaining sediment. Place two drops of the sediment onto a clean, labeled microscope slide and carefully apply a cover slip.

- Microscopic Examination: Systematically examine the entire cover-slipped area under the microscope. Begin with a 10x objective to scan for larger structures like helminth eggs, then switch to the 40x objective for detailed observation and identification of protozoan cysts, eggs, and larvae [3].

- Identification: Identify and count parasitic structures based on morphological characteristics. The use of iodine staining can aid in visualizing protozoan cysts.

The entire workflow from sample receipt to result interpretation is summarized in the following diagram.

Results and Data Presentation

Comparative Performance of Diagnostic Techniques

A hospital-based cross-sectional study comparing the diagnostic performance of direct wet mount and concentration techniques revealed significant differences in sensitivity. The results, summarized in the table below, demonstrate the superior recovery rate of the Formol-Ethyl Acetate Concentration (FAC) method, making it particularly suitable for detecting low-intensity infections [3].

Table 2: Comparative Detection Rates of Parasites by Different Diagnostic Techniques (n=110) [3]

| Parasite Identified | Wet Mount | Formol-Ether Concentration (FEC) | Formol-Ethyl Acetate Concentration (FAC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blastocystis hominis | 4 (9%) | 10 (15%) | 12 (15%) |

| Entamoeba coli | 6 (14%) | 8 (12%) | 8 (10%) |

| Entamoeba histolytica | 13 (31%) | 18 (26%) | 20 (24%) |

| Giardia lamblia | 9 (20%) | 12 (18%) | 13 (16%) |

| Hymenolepis nana | 2 (1%) | 4 (6%) | 5 (6%) |

| Ascaris lumbricoides | 4 (10%) | 4 (6%) | 7 (8%) |

| Strongyloides stercoralis | 1 (2%) | 2 (3%) | 4 (5%) |

| Trichuris trichiura | 1 (2%) | 3 (4%) | 3 (4%) |

| Taenia sp. | 5 (11%) | 7 (10%) | 10 (12%) |

| Overall Detection Rate | 45 (41%) | 68 (62%) | 82 (75%) |

Enhanced Detection of Dual Infections

Concentration methods, especially FAC, prove critical in research settings for identifying polyparasitism. The same study demonstrated that dual infections (e.g., E. histolytica cyst with A. lumbricoides eggs) were detectable by both FEC and FAC. However, one case of A. lumbricoides eggs co-occurring with Strongyloides stercoralis larvae was detected only by the FAC technique, underscoring its higher sensitivity for complex, low-burden infections [3].

Discussion

Advantages of the FECT Protocol in Research

The standardized FECT protocol offers several key advantages for research on low-intensity parasitic infections:

- Higher Sensitivity: As evidenced in Table 2, FAC detected 75% of infections compared to 41% for direct wet mount, a significant increase crucial for accurate prevalence studies and endpoint measurement in clinical trials [3].

- Clearer Sediment: The use of solvents like ethyl acetate or ether effectively removes debris and fats, resulting in a cleaner sediment. This reduces obscuring material and facilitates easier and more accurate microscopic identification.

- Versatility and Safety: The protocol is effective for a wide range of parasites, including protozoan cysts and helminth eggs/larvae. Ethyl acetate is often preferred over diethyl ether due to its lower flammability, making it safer and more feasible for use in rural or resource-limited field settings with minimal infrastructure [3].

Context within Broader Research Trends

While traditional methods like FECT remain the gold standard for community-level screening and drug efficacy studies, the field of parasitological diagnostics is rapidly evolving. Researchers are increasingly exploring advanced technologies to push the boundaries of sensitivity and specificity.

- Limitations of Current Methods: Even with concentration techniques, challenges remain in standardizing spiking methods for difficult-to-test chemicals and ensuring ecological relevance when using natural sediments in toxicity testing [19].

- Future Directions: Nanobiosensors: The future of diagnosing low-intensity infections may lie in nanobiosensors. These analytical tools integrate nanotechnology with biology to detect parasites, antigens, or genetic material with high sensitivity and specificity [20]. They utilize various nanomaterials like gold nanoparticles, quantum dots, and carbon nanotubes, functionalized with biological molecules (antibodies, DNA probes) to target specific parasitic biomarkers [20]. The development of multiplex nanobiosensors and their integration into lab-on-a-chip (LoC) platforms represents a promising avenue for creating point-of-care (PoC) diagnostic tools that could revolutionize the detection and management of parasitic infections in the future [20].

Within public health and parasitology research, the accurate diagnosis of intestinal parasitic infections (IPIs) is fundamental, particularly as control programs progress and infection intensities decline [21] [4]. The Formalin-Ethyl Acetate (FEA) concentration technique, also referred to as the Formalin-Ether Acetate (FAC) technique, is a cornerstone diagnostic method for detecting parasitic elements in stool samples. This technique, alongside its variant the Formalin-Ether Concentration (FEC) technique, serves as a critical tool in epidemiological surveys, drug efficacy trials, and individual patient diagnosis [3] [21]. The core principle involves using formalin to fix parasitic structures and ethyl acetate (or diethyl ether) as a solvent to extract fats and debris, followed by centrifugation to sediment the target parasites for microscopic examination [3] [22]. This application note provides a comparative analysis of FEA against FEC and other methodological variants, framing the discussion within the context of a broader thesis on optimizing diagnostic techniques for low-intensity parasitic infections. It includes structured quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and practical tools to guide researchers and scientists in the field.

Comparative Performance Analysis

A hospital-based cross-sectional study conducted in 2023 provides direct, quantitative comparison of FEA, FEC, and direct wet mount techniques. The findings demonstrate clear performance differences crucial for low-intensity infection research [3].

Table 1: Comparative Detection Rates of Parasitological Techniques (n=110 samples)

| Parasite Category | Specific Parasite | Wet Mount (n, %) | Formalin-Ether (FEC) (n, %) | Formalin-Ethyl Acetate (FEA) (n, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protozoal Cysts | Blastocystis hominis | 4 (9%) | 10 (15%) | 12 (15%) |

| Entamoeba histolytica | 13 (31%) | 18 (26%) | 20 (24%) | |

| Giardia lamblia | 9 (20%) | 12 (18%) | 13 (16%) | |

| Entamoeba coli | 6 (14%) | 8 (12%) | 8 (10%) | |

| Helminth Eggs/Larvae | Taenia sp. | 5 (11%) | 7 (10%) | 10 (12%) |

| Ascaris lumbricoides | 4 (10%) | 4 (6%) | 7 (8%) | |

| Hymenolepis nana | 2 (1%) | 4 (6%) | 5 (6%) | |

| Strongyloides stercoralis | 1 (2%) | 2 (3%) | 4 (5%) | |

| Trichuris trichiura | 1 (2%) | 3 (4%) | 3 (4%) | |

| Overall Detection | 45 (41%) | 68 (62%) | 82 (75%) |

The overall detection rate of FEA (75%) was superior to both FEC (62%) and direct wet mount (41%) [3]. Furthermore, FEA proved more effective in identifying dual infections, a scenario often challenging to diagnose in low-intensity settings. For instance, in one sample, FEA detected Ascaris lumbricoides eggs co-infecting with Strongyloides stercoralis larvae, which was missed by the FEC method [3].

Table 2: Summary of Technique Advantages and Limitations

| Technique | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Suitability for Low-Intensity Infections |

|---|---|---|---|

| FEA (FAC) | Higher recovery rate for most parasites; safer reagent [3] [22] | May require procedural optimization for specific parasites [23] | High - Superior overall recovery rate [3] |

| FEC | Well-established; effective for protozoa [22] | Lower sensitivity for helminths; ether is flammable and volatile [3] [22] | Moderate - Lower overall sensitivity vs. FEA [3] |

| Kato-Katz | Quantifies egg counts; WHO recommended for STH [4] | Low sensitivity for light infections and Strongyloides [4] | Low in reduced intensity, but remains gold standard for STH morbidity assessment [4] |

| Modified FECT | High sensitivity for Strongyloides larvae [24] | Requires specific modification (wire mesh, reduced formalin time) [24] | High for Strongyloides - Detection rate comparable to agar plate culture [24] |

However, the performance of FEA can vary. One study on Schistosoma japonicum reported a low sensitivity of 28.6% for the formol-ethyl acetate technique in low-intensity infections when compared to a composite reference standard, suggesting that its efficacy might be parasite-specific [25]. For protozoan cysts, FEC has been noted to demonstrate high efficiency, sometimes surpassing other formalin-based techniques [22].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Standard Formalin-Ethyl Acetate (FEA) Concentration Technique

This protocol is adapted from established methods and is designed for optimal recovery of a broad range of intestinal parasites [3].

Principle: Formalin fixes parasitic structures and preserves morphology, while ethyl acetate acts as a solvent to extract fats, debris, and dissolved substances, reducing contaminating material. Centrifugation sediments the heavier parasitic elements for microscopic examination.

Materials & Reagents:

- 10% Buffered Formalin: Preserves parasitic structures.

- Ethyl Acetate: Solvent for extracting fecal debris.

- Centrifuge Tube (15 mL conical): For sample processing.

- Gauze or Sieve (approx. 500 µm mesh): For filtering coarse debris.

- Centrifuge: With swing-out rotor.

- Microscope Slides and Coverslips (22x22 mm or 24x50 mm): For sediment examination.

Procedure:

- Emulsification: Transfer approximately 1–2 grams of fresh or formalin-preserved stool to a centrifuge tube. Add 7–10 mL of 10% formalin and emulsify the sample thoroughly.

- Filtration: Pour the emulsified suspension through two layers of wet gauze (or a wire mesh sieve) into a clean 15 mL conical centrifuge tube. This step removes large, coarse particulate matter.

- Solvent Addition: Add 3–4 mL of ethyl acetate to the filtrate. Securely close the tube cap.

- Vigorous Mixing: Shake the tube vigorously for at least 30 seconds. Ensure the solvents are mixed completely by inverting the tube multiple times. Note: Vent the tube carefully to release pressure if necessary.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 500–700 x g for 5–10 minutes. This step creates four distinct layers:

- Top Layer: Ethyl acetate (plug of debris).

- Second Layer: Plug of fecal debris.

- Third Layer: Formalin.

- Fourth Layer: Sediment containing parasites.

- Supernatant Removal: Loosen the debris plug from the tube walls with an applicator stick. Decant the top three layers (ethyl acetate, debris plug, and formalin) in a single, smooth motion.

- Sediment Preparation: Using a pipette, mix the remaining sediment with the small amount of fluid left in the tube. Transfer one drop to a microscope slide, cover with a coverslip, and label.

- Microscopy: Systematically examine the entire sediment under the microscope at 100x (for initial screening and helminth eggs) and 400x magnification (for protozoan cysts and confirmation).

Modified Formalin-Ether Technique forStrongyloides stercoralis

Standard FEC/FEA can trap Strongyloides larvae in gauze filters. This modified protocol significantly improves larval recovery [24].

Principle: Replaces gauze with wire meshes to prevent larval adhesion and reduces formalin exposure time to maintain larval density, thereby enhancing detection sensitivity.

Materials & Reagents:

- Two Wire Meshes (Coarse: 2x2 mm; Fine: 1.2x1.2 mm): For filtration without trapping larvae.

- 0.85% Saline: For initial suspension.

- 10% Formalin and Diethyl Ether: Standard concentration reagents.

Procedure:

- Suspension: Emulsify 2 grams of fresh stool (not formalin-preserved) in 10 mL of 0.85% saline.

- Mesh Filtration: Filter the suspension through a funnel stacked with the fine wire mesh (on top) and the coarse mesh (about 1 cm above the fine mesh) into a centrifuge tube.

- Rinse: Wash any trapped material on both meshes with 3 mL of saline into the tube.

- Initial Centrifugation: Centrifuge the filtrate at 700 x g for 5 minutes. Decant the supernatant.

- Formalin Addition: Adjust the volume of the sediment to 7 mL with 10% formalin. Do not mix.

- Ether Addition and Mixing: Immediately add 3 mL of diethyl ether. Close the tube and shake vigorously by hand for 1 minute.

- Immediate Centrifugation: Centrifuge immediately at 700 x g for 5 minutes.

- Sediment Examination: Loosen the debris plug, pour off the top three layers, and examine the entire sediment microscopically for larvae.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for FEA/FEC Protocols

| Item | Function/Role in Protocol | Key Considerations for Researchers |

|---|---|---|

| 10% Buffered Formalin | Fixes and preserves cysts, eggs, and larvae. Prevents further development or degradation. | Buffering prevents acidic damage to parasitic structures. Essential for sample storage and transport. |

| Ethyl Acetate (FEA) | Solvent for extraction of fats, dissolved debris, and other contaminants from the fecal suspension. | Preferred over diethyl ether in many labs due to lower flammability and better safety profile [3] [22]. |

| Diethyl Ether (FEC) | Alternative solvent to ethyl acetate in the conventional protocol. | Highly flammable and volatile, requiring careful handling and storage. May form explosive peroxides [22]. |

| Gauze / Wire Mesh | Filters coarse, undigested fecal debris from the suspension prior to centrifugation. | Standard gauze can trap larvae (e.g., Strongyloides). Wire mesh (modified protocol) improves larval recovery [24]. |

| Centrifuge | Separates parasitic structures from other fecal components via differential sedimentation. | Swing-out rotors are ideal. Standard speed is 500-700 x g for 5-10 min. Specific protocols may require optimization [23]. |

| Merthiolate-Iodine-Formalin (MIF) | A combined fixative and stain used in alternative concentration techniques. | Useful for field surveys due to long shelf life. Iodine stains protozoan cysts, aiding identification [10]. |

Workflow and Decision Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the procedural workflow for the FEA technique and the decision-making process for selecting the appropriate concentration method in a research context.

Diagram 1: FEA Technical Workflow & Research Method Selection Guide. The chart outlines the step-by-step procedure for the Formalin-Ethyl Acetate (FEA) concentration technique and provides a decision pathway for selecting the most appropriate concentration method based on specific research goals.

The comparative analysis affirms that the Formalin-Ethyl Acetate (FEA) concentration technique offers a superior recovery rate for a broad spectrum of intestinal parasites compared to the traditional Formalin-Ether (FEC) method and direct smear, making it a highly suitable choice for surveys and research where general parasite detection is the goal [3]. Its enhanced safety profile due to the use of ethyl acetate is a significant operational advantage [22]. However, for research specifically targeting Strongyloides stercoralis or certain protozoan cysts, modified FEC protocols or alternative techniques may provide higher sensitivity [24] [22]. The findings from schistosomiasis research further underscore that no single technique is universally optimal [25]. Therefore, the selection of a concentration method must be guided by the target parasite, the expected infection intensity, and the specific research question. For the most accurate diagnosis in low-intensity infection research, a multi-method approach, combining the strengths of different techniques, is strongly recommended.

Application Notes

This document provides a detailed protocol and supporting application notes for the Formol-Ethyl Acetate (FEA) concentration technique, a critical diagnostic method for the detection of low-intensity intestinal parasitic infections. Optimizing this procedure is essential for research and drug development aimed at neglected tropical diseases, where sensitivity limitations can impact epidemiological studies and therapeutic efficacy assessments.

The sample size used during processing directly influences diagnostic yield. Larger samples increase the probability of detecting low-abundance parasites. The centrifugation speed and time are crucial for maximizing the recovery of parasitic elements from the stool suspension. Furthermore, in related microfluidic diagnostic development, solvent choice affects the polarity of the mixture during nanoprecipitation, directly influencing the self-assembly and characteristics of lipid-based nanoparticles used in novel assay systems [26].

The table below summarizes the quantitative impact of these key factors on diagnostic sensitivity.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Key Technical Factors on Assay Sensitivity

| Factor | Parameter Tested | Performance Outcome | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stool Sample Size [27] [3] | 0.5 g vs. 2.0 g | FAC Detection Rate: ~75% (2g) vs. lower sensitivity (0.5g) | A larger sample size (2g) significantly improves parasite recovery compared to smaller samples (0.5g). |

| Centrifugation Speed [28] | 2000×g vs. 6000×g | MGIT Positivity: 60% (2000×g) vs. 80% (6000×g); LJ Positivity: 10% (2000×g) vs. 70% (6000×g) | Higher centrifugation speeds (6000×g) markedly improve microbial yield and culture sensitivity. |

| Solvent Polarity in Microfluidics [26] | Methanol vs. Isopropanol (IPA) | Liposome particle size increases as solvent polarity decreases (MeOH to IPA). | Solvent polarity is a critical attribute; less polar solvents like IPA generally produce larger liposomes. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for optimizing the FEA concentration technique, integrating the three key factors discussed.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standardized Formol-Ethyl Acetate (FEA) Concentration Technique

This protocol is optimized for maximum recovery of parasites from stool specimens [3].

1. Sample Preparation and Emulsification

- Place approximately 1-2 grams of fresh or preserved stool into a clean 15 mL conical centrifuge tube [3].

- Add 7-10 mL of 10% formol saline (formalin) to the tube for fixation. Emulsify the stool sample thoroughly with the formalin using an applicator stick.

- Fix the suspension for 10 minutes [3].

2. Filtration and Solvent Addition

- Pour the emulsified suspension through a sieve or three layers of gauze into a new 15 mL conical centrifuge tube to remove large particulate matter.

- Add 3-4 mL of ethyl acetate (or diethyl ether) to the filtered solution [3].

- Securely close the tube cap and vigorously shake the mixture in an inverted position for at least 1 minute to ensure complete extraction of lipids and debris into the solvent layer.

3. Centrifugation and Examination

- Centrifuge the tube at 1500-3000 rpm for 5 minutes. For maximum recovery of organisms, higher speeds (e.g., 6000×g) have been shown to be highly effective, though adapter compatibility must be confirmed [28].

- After centrifugation, four distinct layers will form: a pellet of sediment (containing parasites) at the bottom, a layer of formalin, a plug of debris, and a top layer of ethyl acetate.

- Free the debris plug by ringing the sides of the tube with an applicator stick. Carefully decant the top three layers (supernatant, debris plug, and solvent) into a discard basin.

- Use a cotton-tipped applicator to wipe the inner walls of the tube clean of residual debris.

- Resuspend the final sediment pellet by tapping the tube. Transfer a drop of the sediment onto a microscope slide, cover with a coverslip, and examine systematically under a light microscope (begin at 10x objective, then confirm at 40x) for ova, cysts, and larvae [3].

Protocol 2: Microfluidic Liposome Formation for Assay Development

This protocol details the role of solvent selection in forming liposomes for novel assay development, using a bench-scale microfluidic system [26].

1. Lipid Solution Preparation

- Dissolve lipid components (e.g., DSPC, Cholesterol, DSPE-PEG2k) in the chosen organic solvent at a concentration of 4 mg/mL [26].

- Test solvents of varying polarity, such as methanol (MeOH), ethanol (EtOH), or isopropanol (IPA), either alone or in combination (e.g., 50/50 v/v% MeOH/IPA). Isopropanol is often preferred due to its lower toxicity (ICH Q3C Class 3) [26].

- Ensure the lipid mixture is fully dissolved.

2. Microfluidic Mixing and Liposome Formation

- Use a microfluidic system (e.g., Nanoassemblr) with controlled flow rates.

- Mix the organic lipid phase with an aqueous buffer (e.g., PBS or Tris-buffer, pH 7.4) at a defined flow rate ratio (e.g., 3:1 aqueous-to-organic ratio) [26].

- The rapid mixing and nanoprecipitation process, driven by the shifting polarity as the water-miscible solvent diffuses into the aqueous buffer, causes lipids to self-assemble into liposomes [26].

3. Liposome Characterization

- Analyze the resulting liposomes for particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential using dynamic light scattering.

- Expect to find that reducing solvent polarity (from MeOH to EtOH to IPA) generally results in larger liposome particle sizes [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit

The following table lists essential reagents and materials required for the experiments described in these protocols.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Formalin (10%) | Fixative and preservative for stool specimens. | Ensures parasite morphology is maintained and mitigates biohazard risk. |

| Ethyl Acetate | Solvent for extraction of fats and debris in FEC. | Key component for clearing stool extracts in FEA concentration [3]. |

| Methanol, Ethanol, Isopropanol | Organic solvents for dissolving lipids in microfluidics. | Choice impacts final liposome size; IPA offers lower toxicity [26]. |

| Phospholipids (e.g., DSPC, SoyPC) | Primary structural components of liposomes. | SoyPC, HSPC, DSPC are commonly used [26]. |

| Cholesterol | Liposome membrane stabilizer. | Incorporated at specific weight ratios (e.g., 3:1 or 2:1 phospholipid:Chol) [26]. |

| Pegylated Lipid (e.g., DSPE-PEG2k) | Implements a hydrophilic stealth coating on liposomes. | Enhances stability; ≥14 wt% can negate impact of solvent choice on size [26]. |

| Conical Centrifuge Tubes (15 mL) | Container for sample processing and centrifugation. | Withstands forces at high-speed centrifugation (e.g., 6000×g). |

| Microfluidic System | Instrument for controlled nanoprecipitation and liposome formation. | e.g., Nanoassemblr, Spark [26]. |

The relationships between solvent properties, process parameters, and the final product in microfluidic liposome formation are summarized below.

The accurate detection of low-intensity parasitic infections is a critical challenge in the advancement of helminth and protozoan research, particularly as control programs succeed and infection intensities decline [29]. Finite Element Analysis (FEA), an engineering computational method, has recently emerged as a novel tool in parasitology for analyzing the structural impact of parasites on host tissues [30]. This protocol details the adaptation of FEA and complementary diagnostic methods specifically for researching soil-transmitted helminths (STHs) and protozoan cysts, with particular emphasis on applications in low-intensity infection scenarios. The methodologies outlined herein are designed to support researchers and drug development professionals in overcoming significant sensitivity limitations inherent in conventional microscopy-based diagnostics, which often fail to detect infections in low-prevalence settings [31] [32].

Background and Significance

Diagnostic Challenges in Low-Intensity Infections

The declining sensitivity of routine diagnostic tests in low-transmission settings presents a substantial barrier to eradication efforts. The widely used Kato-Katz technique, for instance, demonstrates variable sensitivity that drops significantly at low infection intensities—from 74-95% at high intensities to just 53-80% for hookworm and Ascaris lumbricoides in low-intensity settings [31]. Similarly, molecular diagnostics like PCR, while offering superior sensitivity (approximately 98%), present challenges in resource-limited settings due to equipment requirements, cost, and necessary technical expertise [32]. This sensitivity gap necessitates the development and refinement of highly sensitive detection protocols, including the adaptation of advanced computational approaches like FEA.

Fundamental Parasite Biology Affecting Diagnostics

The structural and biological differences between helminths and protozoa necessitate distinct diagnostic approaches:

- Helminths (STHs): Large, multicellular worms including nematodes (roundworms like Ascaris lumbricoides, hookworms, Trichuris trichiura), cestodes (tapeworms), and trematodes (flukes). Diagnosis typically relies on microscopic identification of eggs in stool samples [33] [34].

- Protozoa: Microscopic, single-celled organisms including Giardia duodenalis, Cryptosporidium spp., and Entamoeba histolytica. These organisms multiply in human hosts and are typically detected as cysts or oocysts in stool [33] [34].

Table 1: Key Biological Characteristics of Target Parasites

| Parasite Category | Representative Species | Infective Stage | Key Morphological Features | Primary Detection Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil-Transmitted Helminths | Ascaris lumbricoides | Egg | Fertilized: 45-75 µm x 35-50 µm, unfertilized: longer, elliptical | Microscopy (Kato-Katz) [29] |

| Trichuris trichiura | Egg | 50-55 µm x 22-25 µm, barrel-shaped with polar plugs | Microscopy (Kato-Katz) [29] | |

| Hookworms (Necator americanus, Ancylostoma duodenale) | Egg | 55-75 µm x 36-40 µm, thin-walled, oval | Microscopy (Kato-Katz) [29] | |

| Protozoan Parasites | Cryptosporidium spp. | Oocyst | 4-6 µm, spherical, acid-fast positive | Immunofluorescence, molecular methods [35] |

| Giardia duodenalis | Cyst | 8-12 µm x 7-10 µm, oval, 4 nuclei | Microscopy, ELISA, molecular methods [34] |

Materials and Reagents

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Parasite Diagnostic Protocols

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Protocol Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Saturated Sodium Chloride (NaCl) Solution | Flotation medium for concentrating helminth eggs via density separation | SIMPAQ/Lab-on-a-Disk for STHs [36] |

| Formol-Ether/Ethyl Acetate | Preservation and concentration of parasites via sedimentation | Formol-ether concentration technique (FECT) for general parasitology [29] |

| Glycerol-Methylene Blue Solution | Clears fecal debris and stains parasites for microscopy | Kato-Katz thick smear for STHs [29] |

| Immunomagnetic Separation (IMS) Beads | Antibody-coated magnetic beads for specific capture of target parasites | Cryptosporidium detection in food/water samples [35] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of parasite genetic material from samples | Molecular detection (PCR/qPCR) for both helminths and protozoa [29] [32] |

| Surfactants (e.g., Tween 20) | Reduce egg adhesion to equipment surfaces during processing | Modified SIMPAQ protocol to minimize egg loss [36] |

| Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Master Mix | Amplification of parasite-specific DNA sequences | Molecular diagnosis, especially in low-intensity infections [29] [32] |

| Fixatives (e.g., Formalin, SAF) | Preserve parasite morphology for microscopy and DNA for molecular methods | Sample storage and transport [34] |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

FEA Application in Parasitology Research

The application of Finite Element Analysis in parasitology represents a novel approach for understanding parasite-host interactions. The protocol below adapts FEA methodology from paleontological applications to modern parasitic diagnostics [30].

Protocol 4.1.1: FEA for Analyzing Parasite-Induced Structural Modifications

Principle: FEA uses computational modeling to analyze stress distribution and structural integrity in biological specimens. In parasitology, this can be applied to understand how parasite infestation affects host tissues or to optimize diagnostic device design [30].

Materials:

- Micro-computed tomography (μCT) scanner

- FEA software (e.g., ANSYS, Abaqus, COMSOL)

- Preserved or fossilized specimens with parasite evidence

- High-performance computing workstation

Procedure:

- Specimen Selection and Imaging:

- Select specimens with clear evidence of parasitic infection (e.g., branchial swellings in crustaceans for epicaridean isopods)

- Perform high-resolution μCT scanning to generate detailed 3D models of infected and non-infected specimens

- Export 3D model data in standard format (e.g., STL, DICOM)

Model Reconstruction and Meshing:

- Import 3D models into FEA software

- Generate finite element mesh with appropriate element type and density

- Define material properties based on biological literature or experimental data

Boundary Conditions and Loading:

- Apply realistic constraints to mimic natural conditions

- Simulate physiological loads (e.g., point forces, pressure) that represent environmental stresses

- Run analysis to determine stress distribution patterns

Comparative Analysis:

- Compare stress distributions between infected and non-infected structures

- Identify areas of stress concentration in parasite-modified structures

- Correlate computational findings with observational data

Applications:

- Understanding biomechanical implications of parasite infestation

- Optimizing design of microfluidic devices for parasite egg capture [36]

- Predicting preservation potential of parasitic traces in archaeological contexts [30]

Figure 1: FEA Workflow for Parasitology Research

Advanced Diagnostic Protocols for Low-Intensity Infections

SIMPAQ/Lab-on-a-Disk Protocol for Helminth Eggs

Principle: The SIMPAQ (Single-Image Parasite Quantification) device employs lab-on-a-disk technology and centrifugal forces to concentrate and trap helminth eggs through two-dimensional flotation, enabling single-image quantification of eggs from stool samples [36].

Materials:

- SIMPAQ disk device

- Centrifuge compatible with LoD platforms

- Digital camera for imaging

- Saturated sodium chloride flotation solution

- Surfactant (e.g., Tween 20)

- 200 μm filter membrane

- Stool sample (1 g)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Homogenize 1 g of stool sample with 5 mL of saturated NaCl solution containing 0.1% surfactant

- Filter the mixture through a 200 μm mesh to remove large debris

Disk Loading and Centrifugation:

- Load the filtered sample into the disk chamber

- Centrifuge at optimized speed (protocol-dependent, typically 500-800 RPM)

- Centrifugal force directs eggs toward the center while debris sediments

Imaging and Quantification:

- Capture a single digital image of the Field of View (FOV)

- Count eggs manually or using image analysis software

- Calculate eggs per gram (EPG) based on known sample volume

Performance Characteristics:

- Sensitivity: 91.39-95.63% compared to McMaster technique [36]

- Capable of detecting low egg counts (30-100 EPG) [36]

- Strong correlation (0.91) with Mini-FLOTAC method [36]

Technical Notes:

- Modified protocols with reduced channel length (27 mm vs. 37 mm) minimize Coriolis and Euler forces that deflect eggs [36]

- Surfactant addition reduces egg adhesion to equipment surfaces [36]

- Significantly reduces egg loss compared to initial prototypes [36]

Molecular Detection with Sample Pooling

Principle: Pooling samples before DNA extraction and PCR analysis reduces costs while maintaining high sensitivity, particularly advantageous in low-prevalence settings or for large-scale surveillance [32].

Materials:

- Stool samples from multiple individuals

- DNA extraction kit

- PCR/qPCR reagents and equipment

- Platform shaker for homogenization

Procedure:

- Pool Construction:

- Combine equal portions (e.g., 100-200 mg) from each sample in the pool

- Homogenize thoroughly to ensure even distribution

- For prevalence estimation, optimal pool size depends on expected prevalence

- DNA Extraction and Analysis:

- Extract DNA from the pooled sample using standard protocols

- Perform species-specific PCR or multiplex qPCR

- For positive pools, individual samples can be tested to identify infected subjects

Optimization Considerations: