Microscopy vs. Molecular Methods for Protozoan Diagnosis: A Critical Comparison for Modern Laboratories

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the evolving landscape of protozoan parasite diagnostics.

Microscopy vs. Molecular Methods for Protozoan Diagnosis: A Critical Comparison for Modern Laboratories

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the evolving landscape of protozoan parasite diagnostics. It explores the foundational principles of traditional microscopy and the technological advancements of molecular techniques. The content delves into methodological applications, troubleshooting common challenges, and presents validation data from recent comparative studies. By synthesizing evidence on sensitivity, specificity, and practical implementation, this review serves as a strategic guide for selecting diagnostic approaches, optimizing laboratory workflows, and informing the development of next-generation diagnostic tools and therapeutics.

The Diagnostic Paradigm Shift: From Microscopy to Molecular Assays

The Enduring Role and Inherent Limitations of Conventional Microscopy

Despite the advent of advanced molecular techniques, conventional microscopy remains a cornerstone for diagnosing pathogenic intestinal protozoa, which are significant causes of diarrheal diseases affecting approximately 3.5 billion individuals globally each year [1]. In many clinical and resource-limited settings, microscopic examination of stool specimens persists as the reference standard, providing a low-cost diagnostic method capable of detecting a broad range of parasites [2]. However, this technique faces significant challenges related to sensitivity, specificity, and operational requirements, which continue to fuel the comparison with emerging molecular diagnostics [1] [3].

This application note details the standardized protocols for conventional microscopic examination, analyzes its performance characteristics against molecular methods, and provides a technical resource for researchers and laboratory professionals working in parasitology diagnostics and drug development.

Established Protocols for Microscopic Diagnosis

Specimen Collection and Preparation

Optimal recovery and identification of protozoa depend critically on proper specimen handling. Key considerations include:

- Collection Interval: Collect multiple specimens, optimally every other day [2].

- Specimen Number: Analysis of three specimens increases detection yield by 11.3% for Giardia, 22.7% for E. histolytica, and 31.1% for D. fragilis compared to single samples [2].

- Preservation: Fresh specimens should be examined immediately or preserved appropriately. Fixed specimens (e.g., in Para-Pak media or formalin) enable concentration techniques and better morphological preservation [1].

Stool Concentration and Staining Workflow

The formalin-ethyl acetate (FEA) concentration method enhances parasite detection and represents the standard workflow for fixed specimens [1].

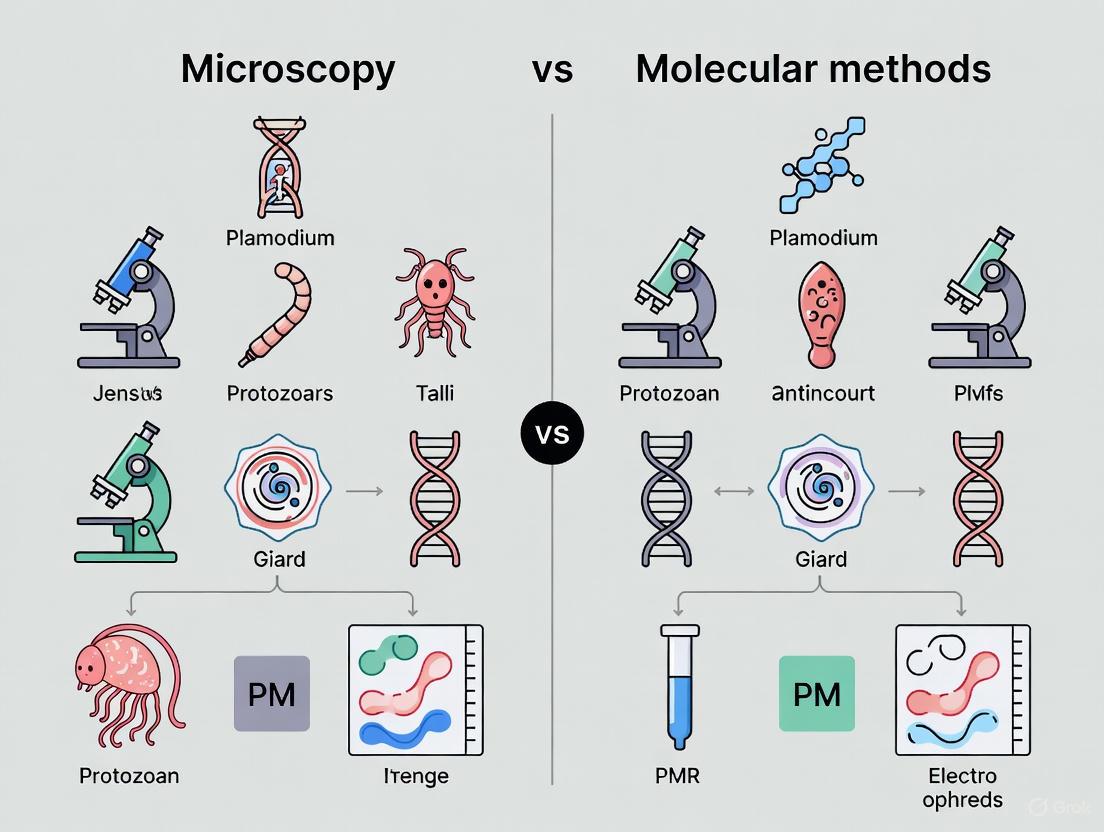

Figure 1: Standardized workflow for microscopic detection of intestinal protozoa, integrating both fresh and preserved sample pathways [1].

Microscopic Examination Procedure

- Fresh Specimens: Examine directly with Giemsa staining for immediate morphological assessment [1].

- Fixed Specimens: Process using the FEA concentration technique to concentrate parasitic elements [1].

- Microscopy: Systematically scan smears under both low-power (10×) and high-power (40×) objectives, with oil immersion (100×) for definitive identification.

- Quality Assurance: Review positive specimens with multiple trained technologists to maintain staff competency and identification accuracy [2].

Performance Analysis: Microscopy vs. Molecular Methods

Comparative Diagnostic Performance

Recent multicenter studies directly comparing microscopy with molecular techniques reveal distinct performance patterns across protozoan species.

Table 1: Comparative performance of microscopy versus molecular methods for protozoan detection [1] [4]

| Parasite | Microscopy Sensitivity Limitations | Molecular Method Advantages | Agreement (κ statistic) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Giardia duodenalis | Moderate; cyst excretion can be intermittent | High sensitivity and specificity; complete agreement between commercial & in-house PCR | Almost perfect (κ = 0.88) [4] |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | Low; requires special stains for oocyst visualization | Enhanced detection of low-intensity infections | Substantial (κ = 0.74) [4] |

| Entamoeba histolytica | Cannot differentiate from non-pathogenic E. dispar | Specific identification of pathogenic species | Critical for accurate diagnosis [1] |

| Dientamoeba fragilis | Low sensitivity (31.1% increase with 3 samples) [2] | Detects 16 additional infections missed by microscopy [4] | Limited sensitivity due to DNA extraction issues [1] |

Operational Limitations in Clinical Practice

Conventional microscopy faces significant implementation challenges that affect diagnostic reliability and efficiency.

Table 2: Key limitations of conventional microscopy in diagnostic parasitology [2]

| Limitation Category | Specific Challenges | Impact on Diagnostic Service |

|---|---|---|

| Technical Expertise | Requires experienced microbiologists; declining skilled workforce | Misidentification of species; inability to differentiate pathogens from non-pathogens |

| Sensitivity Issues | Single specimen detects only 58-72% of protozoa; irregular parasite shedding | False negatives; requirement for multiple specimens increases cost and turnaround |

| Operational Burden | Labor-intensive; time-consuming processing and analysis | Long turnaround times; testing often deferred until other tasks completed |

| Proficiency Maintenance | Low specimen positivity rates in non-endemic areas | Reduced technologist competency; challenges in training new staff |

| Differentiation Capacity | Cannot morphologically distinguish E. histolytica from E. dispar | Clinical misinterpretation; potential unnecessary treatment |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and materials constitute the fundamental toolkit for conventional protozoan diagnosis.

Table 3: Essential research reagents for microscopic detection of intestinal protozoa

| Reagent/Material | Application | Technical Function |

|---|---|---|

| Para-Pak Preservation Media | Stool specimen transport and storage | Preserves parasite morphology for delayed examination [1] |

| Formalin-Ethyl Acetate (FEA) | Stool concentration | Separates parasitic elements from fecal debris for enhanced detection [1] |

| Giemsa Stain | Fresh specimen staining | Highlights nuclear and cytoplasmic details of trophozoites and cysts [1] |

| Saline Solution | Wet mount preparation | Provides medium for immediate examination of motile trophozoites [2] |

| Iodine Solution | Wet mount staining | Enhances internal structures of cysts for morphological identification [2] |

Integration with Modern Diagnostic Approaches

While microscopy remains fundamental, its limitations have driven development of supplemental and replacement technologies:

- Immunoassays: Immunochromatographic and ELISA tests offer rapid screening for specific pathogens like Giardia and Cryptosporidium but may yield false positives/negatives [1] [2].

- Molecular Diagnostics: PCR-based methods provide superior sensitivity and specificity, particularly for low-prevalence settings, but require DNA extraction optimization and cannot detect organisms not targeted by the assay [1] [5].

- Algorithmic Testing: Some laboratories implement front-line antigen testing followed by microscopy for negatives, though this requires clinical context often unavailable to laboratories [2].

The relationship between diagnostic methodologies can be visualized as a complementary system where each approach addresses specific limitations.

Figure 2: Evolution of diagnostic technologies for intestinal protozoa, showing complementary strengths at each developmental stage [3] [5].

Conventional microscopy maintains an enduring role in protozoan diagnosis due to its low cost, broad spectrum detection capability, and accessibility in resource-limited settings. However, its inherent limitations—including operator dependency, variable sensitivity, and inability to differentiate morphologically similar species—necessitate supplemental approaches for comprehensive diagnostic accuracy. Modern laboratories increasingly implement integrated diagnostic algorithms that leverage the strengths of both conventional and molecular methods, particularly for pathogenic species like Entamoeba histolytica and Dientamoeba fragilis where microscopic differentiation proves problematic. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these limitations is crucial for designing effective diagnostic strategies and interpreting clinical trial data across different geographical and resource settings.

The Global Burden of Protozoan Infections Driving Diagnostic Innovation

Pathogenic intestinal protozoa represent a significant global health challenge, with an estimated 3.5 billion people affected annually and approximately 1.7 billion episodes of diarrheal disorders each year [6] [7]. These infections contribute substantially to global diarrheal morbidity and mortality, particularly in resource-limited settings [8]. The most clinically significant enteric protozoa include Giardia duodenalis, Cryptosporidium spp., and Entamoeba histolytica, which collectively account for an estimated 500 million annual diarrheal cases worldwide [8]. These pathogens disproportionately affect children under five in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where they are responsible for 10-15% of diarrheal deaths and are increasingly recognized as contributors to long-term growth faltering and cognitive impairment [8].

The epidemiological control of protozoan diseases remains unsatisfactory due to difficulties in vector and reservoir control, while progress in vaccine development has been slow and arduous [9]. Currently, chemotherapy remains an essential component of both clinical management and disease control programs in endemic areas, though existing drugs face limitations including high cost, poor compliance, drug resistance, low efficacy, and poor safety [9]. Accurate diagnosis is therefore critical for both effective treatment and understanding the true burden of these diseases, yet diagnostic challenges persist, with microscopy-based surveillance potentially missing 30-50% of cases detectable by molecular methods [8].

Global Burden and Distribution

Quantitative Assessment of Protozoan Infections

Recent meta-analyses reveal that protozoan pathogens are found in approximately 7.5% of diarrheal cases globally, with the highest prevalence rates observed in the Americas and Africa [8]. The distribution and impact of these pathogens vary significantly by species, geographic region, and population characteristics.

Table 1: Global Prevalence and Health Impact of Major Intestinal Protozoa

| Parasite | Global Prevalence in Diarrheal Cases | Annual Symptomatic Infections | Key Health Impacts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Giardia duodenalis | 2-7% (developed countries), 30-40% (developing countries) [8] | ~280 million [8] [7] | Watery diarrhea, bloating, malabsorption, chronic malnutrition [8] |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | 1-4% worldwide; up to 10% in children in low-income regions [8] | ~200 million (estimated) [8] | Severe watery diarrhea; life-threatening in immunocompromised patients [8] |

| Entamoeba histolytica | ~1-2% true infections (10% carry Entamoeba species) [8] | Not specified | Amoebiasis - bloody diarrhea, dysentery, liver abscess [8] |

| Blastocystis spp. | 10-60% worldwide [8] | Not specified | Sometimes causes diarrhea and abdominal pain; often asymptomatic [8] |

Regional Distribution and Risk Populations

The burden of protozoan infections displays striking geographical disparities. The highest age-standardized prevalence rates for diseases like Chagas disease are found in southern Latin America (2485.9 per 100,000) and Andean Latin America (2313.8 per 100,000) [10]. While prevalence rates in endemic countries have decreased over time due to socioeconomic development and public health measures, non-endemic regions have experienced notable increases in prevalence due to migration from endemic countries [10].

Vulnerable populations include young children, pregnant people, travelers, and immunocompromised individuals, who are most likely to fall ill and endure chronic complications [11]. Nutritional status significantly influences both infection susceptibility and clinical outcomes, with malnourished children facing significantly higher mortality risks from infections like cryptosporidiosis [8].

Diagnostic Challenges and Methodological Comparisons

Limitations of Conventional Microscopy

Microscopic examination of concentrated fecal specimens remains the reference diagnostic method in clinical laboratories for protozoan intestinal infections, primarily due to its low cost and utility in resource-limited settings [6] [7]. However, this method presents substantial limitations:

- Requires qualified microscopists and is time-consuming [7]

- Exhibits limited sensitivity and specificity compared to molecular methods [6]

- Cannot differentiate closely related species (e.g., pathogenic E. histolytica from non-pathogenic E. dispar) [7]

- May miss 30-50% of cases detectable by molecular methods [8]

Immunofluorescence microscopy shows greater sensitivity and specificity than traditional microscopy but is expensive and still requires expert personnel [7]. Similarly, immunochromatography and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) are regarded as suitable techniques for rapid screening but frequently yield elevated rates of false positive and false negative results [7].

Advancements in Molecular Diagnostics

Molecular diagnostic technologies, particularly real-time PCR (RT-PCR), are gaining traction in non-endemic areas characterized by low parasitic prevalence owing to their enhanced sensitivity and specificity [6] [7]. Recent multicenter studies comparing commercial and in-house molecular tests have demonstrated their potential while highlighting specific technical challenges.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Diagnostic Methods for Intestinal Protozoa

| Parasite | Microscopy Limitations | Molecular Method Advantages | Technical Challenges in PCR Detection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Giardia duodenalis | Moderate sensitivity and specificity [6] | Complete agreement between commercial and in-house PCR methods; high sensitivity and specificity [6] [7] | Minimal challenges; reliable detection [6] |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | Cannot differentiate species; variable sensitivity [7] | High specificity; essential for accurate species identification [6] [7] | Limited sensitivity due to inadequate DNA extraction from oocysts [6] [7] |

| Entamoeba histolytica | Cannot differentiate from non-pathogenic E. dispar [7] | Critical for accurate diagnosis and differentiation from non-pathogenic species [6] [7] | Less challenging; effective detection with proper methods [6] |

| Dientamoeba fragilis | Detection challenging; often missed [6] | Enables detection of this neglected pathogen [6] [7] | Inconsistent results; limited sensitivity [6] [7] |

Experimental Protocols for Diagnostic Evaluation

Multicenter Study Design for Method Comparison

A recent multicenter study involving 18 Italian laboratories provides a robust protocol for comparing diagnostic methods for intestinal protozoa [7]. The study analyzed 355 stool samples (230 freshly collected and 125 stored in preservation media) examining infections with Giardia duodenalis, Cryptosporidium spp., Entamoeba histolytica, and Dientamoeba fragilis [6] [7].

Sample Processing Protocol:

- Sample Collection: Collect fresh stool samples or preserve in Para-Pak media [7]

- Microscopic Examination: Process all samples using conventional microscopy following WHO and CDC guidelines [7]

- Staining Procedures: Stain fresh samples with Giemsa; process fixed samples using the FEA (formalin-ethyl acetate) concentration technique [7]

- Storage: Freeze samples promptly at -20°C until molecular analysis [7]

DNA Extraction and Molecular Analysis

DNA Extraction Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Mix 350 µl of S.T.A.R (Stool Transport and Recovery Buffer) with approximately 1 µl of each fecal sample using a sterile loop [7]

- Incubation: Incubate for 5 minutes at room temperature [7]

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 2000 rpm for 2 minutes [7]

- Supernatant Collection: Carefully collect 250 µl of supernatant and transfer to a fresh tube [7]

- Internal Control: Combine with 50 µl of internal extraction control [7]

- Automated Extraction: Extract DNA using MagNA Pure 96 DNA and Viral NA Small Volume Kit on MagNA Pure 96 System [7]

In-house RT-PCR Amplification:

- Reaction Mixture: 5 µl MagNA extraction suspension, 12.5 µl 2× TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix, 2.5 µl primers and probe mix, sterile water to final volume of 25 µl [7]

- PCR Cycling Conditions:

- 1 cycle: 95°C for 10 minutes

- 45 cycles: 95°C for 15 seconds followed by 60°C for 1 minute [7]

- Detection System: ABI 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System [7]

Diagnostic Workflows and Methodological Integration

The following diagnostic workflow illustrates the integrated approach to protozoan diagnosis, combining traditional and molecular methods:

Research Reagent Solutions for Protozoan Diagnosis

The implementation of robust diagnostic protocols requires specific research reagents and laboratory materials. The following table details essential solutions for protozoan detection studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Protozoan Diagnostic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Manufacturer/Source | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Para-Pak Preservation Media | N/A | Preserves stool samples for transport and storage; maintains parasite integrity [7] |

| S.T.A.R Buffer (Stool Transport and Recovery Buffer) | Roche Applied Sciences | Facilitates stool sample processing for DNA extraction; stabilizes nucleic acids [7] |

| MagNA Pure 96 DNA and Viral NA Small Volume Kit | Roche Applied Sciences | Automated nucleic acid extraction using magnetic separation technology [7] |

| TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Provides enzymes, dNTPs, and optimized buffer for efficient RT-PCR amplification [7] |

| Giemsa Stain | Various suppliers | Stains fresh stool samples for microscopic identification of parasites [7] |

| Formalin-Ethyl Acetate (FEA) | Various suppliers | Concentration technique for fixed stool samples prior to microscopic examination [7] |

| AusDiagnostics RT-PCR Test | AusDiagnostics Company (R-Biopharm Group) | Commercial molecular test for detection of major intestinal protozoa [6] [7] |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

Molecular methods show significant promise for the diagnosis of intestinal protozoan infections, particularly in non-endemic regions with low prevalence where high sensitivity is crucial [6] [7]. The molecular assays evaluated in recent studies perform well for G. duodenalis and Cryptosporidium spp. in fixed fecal specimens, though detection of D. fragilis remains inconsistent [6]. Overall, PCR results from preserved stool samples demonstrate better performance than those from fresh samples, likely due to superior DNA preservation in fixed specimens [6].

The integration of molecular diagnostics into parasitology laboratories represents a significant advancement, yet requires further standardization of sample collection, storage, and DNA extraction procedures to ensure consistent results [6]. While PCR techniques offer reliable and cost-effective parasite identification, some authors recommend molecular techniques as a complementary method rather than a replacement for conventional microscopy, as microscopic examination can reveal additional parasitic intestinal infections not targeted by specific PCR assays [7].

Future directions in protozoan diagnosis include the exploration of innovative drug repurposing strategies [12], enhanced food safety protocols to address foodborne transmission [11], and the application of artificial intelligence to improve diagnostic accuracy [12]. As the field continues to evolve, the combination of traditional and molecular methods will likely provide the most comprehensive approach to managing the global burden of protozoan infections.

Comparative Diagnostic Performance of Detection Methods

Table 1: Comparison of diagnostic sensitivity across detection methods for key protozoan pathogens.

| Pathogen | Microscopy | Immunoassay | PCR-Based Methods | Key Diagnostic Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giardia duodenalis | Variable sensitivity [1] | Suitable for rapid screening [1] | High sensitivity and specificity [1] [6] | Differentiation of viable vs. non-viable cysts [13] |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | 6%-23.2% [14] [15] | 15% [14] | 18%-26.8% [14] [15] | Requires high oocyst concentration (>50,000/mL) for microscopy [14] |

| Entamoeba histolytica | 3.17% [16] | Coproantigen ELISA: 4.6% [16] | Nested PCR: 4.75% [16]; Real-time PCR sensitivity: 75-100% [17] | Microscopy cannot differentiate from non-pathogenic E. dispar [17] [16] |

| Blastocystis hominis | Lower sensitivity than culture/molecular methods [18] | Not prominently reported | HRM analysis enables subtyping [18] | Pathogenicity debated; requires subtyping for clinical relevance [18] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Conventional Microscopy and Staining

2.1.1 Direct Wet Mount Microscopy

- Principle: Direct visualization of motile trophozoites, cysts, oocysts, or other parasitic forms in fresh stool.

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Emulsify a small portion of fresh, unpreserved stool (approximately 1-2 mg) in a drop of 0.9% saline on a clean glass slide. Prepare a second smear in a drop of Lugol's iodine solution [16].

- Examination: Apply a coverslip and examine systematically under a light microscope using 10x and 40x objectives [14] [16].

- Identification: Look for characteristic structures: Giardia trophozoites/cysts, Cryptosporidium oocysts, Entamoeba cysts/trophozoites, or Blastocystis vacuolar forms [18] [16].

2.1.2 Concentration Techniques (Formalin-Ether Acetate - FEA)

- Principle: Increase detection sensitivity by concentrating parasitic elements.

- Procedure:

2.1.3 Special Stains

- Modified Kinyoun's Acid-Fast Stain (for Cryptosporidium):

- Procedure: Prepare a stool smear, fix it on a hot plate at 55°C, and stain with Kinyoun's carbol fuchsin for 1 minute. Decolorize with 1% HCl for 2 minutes, then counterstain with methylene blue. Examine under oil immersion (100x objective); Cryptosporidium oocysts stain bright red [14].

Immunological and Antigen-Detection Methods

2.2.1 Coproantigen Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

- Principle: Detect pathogen-specific antigens in stool samples using antibody-coated wells.

- Procedure (for E. histolytica):

- Coating: Use a microtiter plate pre-coated with specific antibodies [16].

- Incubation: Add 100 µL of diluted stool specimen to the well and incubate for 1 hour at 37°C. Wash the plate [16].

- Conjugate: Add 100 µL of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody and incubate for another hour at 37°C. Wash again [16].

- Detection: Add 100 µL of TMB substrate, incubate for 15 minutes at room temperature, and stop the reaction with a stop solution. Measure the absorbance at 450 nm. A sample is positive if the optical density exceeds the predetermined cutoff [16].

2.2.2 Immunochromatography (ICT)

- Principle: Rapid lateral flow test for detecting parasitic antigens.

- Procedure (for Cryptosporidium):

Molecular Detection and Characterization

2.3.1 DNA Extraction from Stool Samples

- Protocol (Silica Column-Based):

- Lysis: Transfer 200 mg of stool to a bead tube. Add lysis buffer and Proteinase K, then incubate at 60°C for 20 minutes [18].

- Binding: Centrifuge the sample and load the supernatant onto a silica column [18].

- Washing and Elution: Wash the column with wash buffers to remove impurities. Elute the purified DNA in 50-200 µL of elution buffer or deionized water [18]. Store extracted DNA at -20°C.

2.3.2 Real-Time PCR (RT-PCR) for Entamoeba histolytica

- Principle: Amplify and detect species-specific DNA sequences in real-time using fluorescent probes.

- Reaction Setup:

- Cycling Conditions: Follow standard real-time PCR cycles (denaturation, annealing, extension) on a suitable thermocycler with fluorescence detection [1]. Results are interpreted based on Cycle Threshold (Ct) values.

2.3.3 High-Resolution Melting (HRM) Analysis for Blastocystis Subtyping

- Principle: Distinguish Blastocystis subtypes based on the unique melting temperature of PCR amplicons from the SSU rRNA gene.

- Procedure:

- PCR Amplification: Perform real-time PCR with EvaGreen dye and specific primers targeting the SSU rRNA gene [18].

- Melting Curve Analysis: After amplification, gradually increase the temperature while continuously monitoring fluorescence. The dye is released from the DNA as it denatures, causing a drop in fluorescence [18].

- Subtype Identification: Different subtypes (ST1-ST7, etc.) are identified by their characteristic melting curve profiles and temperatures [18].

Diagnostic Workflow and Method Selection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential reagents and materials for protozoan pathogen research and diagnosis.

| Category | Specific Item / Kit | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture | Diamond's TYI-S-33 Medium | In vitro culturing of trophozoites | Giardia lamblia trophozoite culture [13] |

| Staining Reagents | Modified Kinyoun's Carbol Fuchsin | Acid-fast staining of oocysts | Cryptosporidium detection [14] |

| Immunoassays | Crypto/Giardia Rapid ICT Assay (Biotech, Spain) | Rapid immunochromatographic antigen detection | Cryptosporidium and Giardia screening [14] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | FavorPrep Stool DNA Isolation Mini Kit; MagNA Pure 96 System | Isolation of PCR-quality DNA from complex stool matrices | DNA extraction for PCR [1] [18] |

| PCR Reagents | HOT FIREPol EvaGreen HRM Mix; TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix | Fluorescent detection in real-time PCR and HRM | Blastocystis subtyping by HRM [18]; Multiplex RT-PCR [1] |

| Antibodies | Anti-Giardia Cyst Antibody (e.g., sc-57744) | Immunofluorescence labeling and confirmation | Cyst wall visualization in Giardia [13] |

The diagnosis of intestinal protozoan infections represents a significant challenge in clinical and research settings. For decades, microscopy has served as the conventional diagnostic method, yet it is hampered by limitations in sensitivity, specificity, and its inability to differentiate morphologically identical species [19] [1] [20]. Molecular detection methods, particularly Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and Real-Time PCR (RT-PCR), have emerged as powerful tools that overcome these limitations, providing superior accuracy, species-level differentiation, and higher throughput for protozoan detection [19] [21] [20]. This document outlines the fundamental principles of these molecular techniques and provides detailed application protocols within the context of protozoan diagnosis, supporting research that compares traditional and molecular diagnostic approaches.

Fundamental Principles of PCR and RT-PCR

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a laboratory technique for amplifying a specific DNA sequence exponentially [22]. Introduced by Kary Mullis in 1985, it utilizes a thermostable DNA polymerase (typically Taq polymerase) to synthesize DNA strands complementary to a target sequence. The process involves three core steps repeated for 30-40 cycles in a thermal cycler:

- Denaturation: The double-stranded DNA template is heated to 90–95°C, breaking hydrogen bonds to separate it into two single strands.

- Annealing: The temperature is lowered to 55–72°C, allowing short, sequence-specific primers to bind (anneal) to their complementary sequences on either side of the target DNA.

- Extension: The temperature is raised to 72°C, the optimal temperature for Taq polymerase to add nucleotides to the 3' end of each primer, synthesizing new DNA strands [22].

This process can amplify a target sequence by a factor of 10^6 to 10^9, producing enough DNA for analysis by methods such as agarose gel electrophoresis [22].

Real-Time PCR (RT-PCR)

Real-Time PCR (also known as quantitative PCR or qPCR) builds upon conventional PCR by enabling the monitoring of amplification as it occurs in real time [22]. This is achieved through fluorescent reporters, which can be either:

- DNA-binding dyes: Non-specific dyes that fluoresce when intercalated with double-stranded DNA.

- Sequence-specific probes: Fluorescently labelled probes (e.g., TaqMan) that provide higher specificity by only binding to the exact target sequence [22].

The key output is the Cycle threshold (Ct), the number of cycles required for the fluorescent signal to cross a predefined threshold. The Ct value is inversely proportional to the starting quantity of the target nucleic acid, allowing for both detection and quantification [22]. RT-PCR eliminates the need for post-amplification processing, reduces the risk of contamination, and provides quantitative data, making it highly suitable for diagnostic applications [19] [22].

Performance Comparison: Microscopy vs. Molecular Methods

Molecular methods offer significant advantages in diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for detecting key intestinal protozoa, as shown by recent comparative studies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Microscopy vs. Multiplex RT-PCR for Protozoan Detection

| Protozoan | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Positive Predictive Value (%) | Negative Predictive Value (%) | Key Advantage of RT-PCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blastocystis hominis | 93.0 [21] | 98.3 [21] | 85.1 [21] | 99.3 [21] | Higher throughput, objective readout [21] |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | 100 [21] | 100 [21] | 100 [21] | 100 [21] | Superior sensitivity, species differentiation [1] [20] |

| Cyclospora cayetanensis | 100 [21] | 100 [21] | 100 [21] | 100 [21] | Eliminates need for expert microscopy [21] |

| Dientamoeba fragilis | 100 [21] | 99.3 [21] | 88.5 [21] | 100 [21] | Detects parasite without cyst stage easily missed by microscopy [1] |

| Entamoeba histolytica | 33.3 - 75* [21] | 100 [21] | 100 [21] | 99.6 [21] | Differentiates pathogenic E. histolytica from non-pathogenic E. dispar [19] [20] |

| Giardia duodenalis | 100 [21] | 98.9 [21] | 68.8 [21] | 100 [21] | High sensitivity and specificity; automatable [1] [21] |

Sensitivity for *E. histolytica increased from 33.3% with fresh specimens to 75% when frozen specimens were included [21].

Table 2: Diagnostic Performance of Different PCR Primer Sets for Trypanosoma lewisi

| Primer Set | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Diagnostic Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|

| LEW1S/LEW1R | 100 [23] | 97.22 [23] | Highest accuracy; consistent, distinct amplicons [23] |

| CATLew F/CATLew R | 96.43 [23] | 97.22 [23] | High performance [23] |

| TC121/TC122 | 67.86 [23] | 97.22 [23] | Moderate sensitivity [23] |

Experimental Protocols for Molecular Detection of Intestinal Protozoa

Protocol: Duplex RT-PCR for Entamoeba and Cryptosporidium

This protocol, adapted from recent research, enables simultaneous detection of multiple protozoa in a 10 µL reaction volume [19].

1. Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

- Sample Collection: Collect stool samples and store unpreserved at -20°C or in preservation media (e.g., Cary-Blair media) for molecular analysis [21]. Preserved samples often yield better DNA quality [1].

- DNA Extraction: Use automated, high-throughput systems (e.g., Hamilton STARlet with STARMag kit) or manual kits (e.g., QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit) [21] [24]. Include an internal extraction control to monitor inhibition and extraction efficiency [24]. Elute DNA in a final volume of 100 µL [21].

2. Primer and Probe Design

- Target Genes: Conserved genomic regions, such as the small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) gene, are ideal targets [19].

- Design Criteria:

- Primer/Probe Sequences:

Table 3: Primer and Probe Sequences for Protozoan Detection

Organism Forward Primer (5'→3') Reverse Primer (5'→3') Probe Sequence (5'→3') Entamoeba histolytica / dispar AGG ATT GGA TGA AAT TCA GAT GTA CA [19] TAA GTT TCA GCC TTG TGA CCA TAC [19] TGA CGG AGT TAA TTG CAA TTA T [19] Cryptosporidium spp. ACA TGG ATA ACC GTG GTA ATT CT [19] CAA TAC CCT ACC GTC TAA AGC TG [19] ACT CGA CTT TAT GGA AGG GTT GTA T [19] Chilomastix mesnili TGC CTT GTC TTT TTG TTA CCA TAA AGA [19] GTC TGA ACT GTT ATT CCA TAC TGC AA [19] GCA GGT CGT GCC CTT GTG G [19]

3. RT-PCR Reaction Setup

- Reaction Mix (10 µL total volume):

- Thermal Cycling Conditions (on Bio-Rad CFX96 or similar):

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 10-20 min.

- 45 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 10 sec.

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 1 min (with fluorescence acquisition) [21].

4. Data Analysis

- A sample is considered positive if the cycle threshold (Ct) value is ≤43 [21].

- For melt curve analysis, ramp temperature from 40°C to 80°C in 1°C increments. A consistent melt temperature (e.g., 63-64°C for D. fragilis) confirms specific amplification, while shifts (e.g., 9°C lower) suggest cross-reactivity with non-target organisms [24].

Workflow: Molecular Detection of Intestinal Protozoa

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for the molecular detection of intestinal protozoa, from sample collection to final analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Molecular Detection of Protozoa

| Item | Function / Application | Example Products / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality DNA from complex stool matrices; critical for assay sensitivity. | QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit [24], STARMag Universal Cartridge [21] |

| PCR Master Mix | Provides buffer, dNTPs, and thermostable DNA polymerase for amplification. | TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix [1] |

| Primers & Probes | Sequence-specific binding for target amplification and detection. | HPLC-purified, designed against SSU rRNA [19] |

| Commercial Multiplex Kits | Validated, standardized panels for simultaneous detection of multiple pathogens. | Seegene Allplex GI-Parasite Assay [21], EasyScreen Enteric Protozoan Detection Kit [24] |

| Internal Controls | Monitor PCR inhibition and DNA extraction efficiency; essential for quality control. | qPCR Extraction Control Kits [24] |

| Automated Platforms | High-throughput, reproducible nucleic acid extraction and PCR setup. | Hamilton STARlet [21], MagNA Pure 96 System [1] |

| Real-Time PCR Cyclers | Instrument for amplification and fluorescent signal detection. | Bio-Rad CFX96 [19] [21] |

Critical Considerations for Molecular Detection

Primer Design and Specificity

Robust primer design is foundational for successful molecular detection. For protozoa, this involves:

- Accessing Genomic Data: Retrieve target sequences (e.g., SSU rRNA) from databases like NCBI [19].

- Identifying Conserved Regions: Align sequences to find highly conserved regions for broad detection and variable regions for species-specific differentiation [19].

- Specificity Checks: Use BLASTN to ensure minimal similarity to non-target organisms, especially close relatives [19] [25]. For example, primers must distinguish pathogenic E. histolytica from non-pathogenic E. dispar [19] [20].

- Validation: Test primers against a panel of positive and negative controls. Melt curve analysis and DNA sequencing of amplicons are crucial for verifying specificity and identifying cross-reactivity, as seen with Simplicimonas sp. in cattle samples misidentified as D. fragilis [24].

Optimization and Troubleshooting

- Annealing Temperature Optimization: Test a gradient (e.g., 55–65°C) to find the temperature yielding the lowest Ct and highest fluorescence with no non-specific amplification [25].

- Inhibition Management: Stool samples contain PCR inhibitors (e.g., bil salts, complex polysaccharides). Dilution of extracted DNA (e.g., 1:5) or use of inhibitor-resistant polymerases can mitigate this [22] [24].

- Cycle Threshold (Ct) Limit: Setting a maximum Ct (e.g., ≤43) helps prevent reporting false positives from late, non-specific amplification [21] [24]. Reducing the total number of cycles (e.g., to less than 40) is also recommended for the same reason [24].

Comparison of Molecular and Microscopy Methods

The following diagram summarizes the key procedural differences and outputs between conventional microscopy and molecular RT-PCR for protozoan diagnosis.

Implementing Modern Diagnostic Protocols: Commercial Kits, In-House Assays, and Workflow Integration

Commercial Multiplex PCR Panels vs. Laboratory-Developed In-House Tests

The diagnosis of pathogenic intestinal protozoa, significant global causes of diarrheal diseases affecting approximately 3.5 billion people annually, has long relied on traditional microscopy [7]. While microscopy remains a low-cost reference method, it is constrained by limitations in sensitivity, specificity, and the need for experienced personnel, particularly for differentiating morphologically similar species [7] [26]. Molecular diagnostics, especially real-time PCR (RT-PCR) technologies, have emerged as powerful alternatives, offering enhanced sensitivity and specificity [7] [26]. Clinical laboratories implementing these molecular methods face a critical choice: adopt commercially developed, CE-IVD/FDA-marked multiplex PCR panels or utilize laboratory-developed tests (LDTs), often referred to as "in-house" assays. This application note delves into this comparison, framing the discussion within a broader thesis on microscopy versus molecular methods for protozoan diagnosis. It provides a structured analysis of performance data, detailed experimental protocols, and essential considerations for researchers and drug development professionals navigating this evolving diagnostic landscape.

Performance Comparison: Commercial Kits vs. In-House Assays

The relative performance of commercial multiplex PCR panels and in-house tests varies significantly across different pathogens and study conditions. The tables below summarize key comparative data from recent studies.

Table 1: Comparative Sensitivity of Commercial Multiplex PCR Panels for Intestinal Protozoa

| Commercial PCR Panel | Giardia duodenalis | Cryptosporidium spp. | Entamoeba histolytica | Dientamoeba fragilis | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BD Max | 89% | 75% (C. parvum/hominis) | Consistent results | Not Specified | Autier et al. [27] |

| RIDAGENE | 41% | 100% (all species) | Consistent results | 71% | Autier et al. [27] |

| G-DiaPara | 64% | 100% (C. parvum/hominis) | Consistent results | Not Specified | Autier et al. [27] |

| AusDiagnostics | High (similar to microscopy) | High Specificity, Limited Sensitivity | Critical for accurate diagnosis | Inconsistent | [7] |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of In-House vs. Commercial PCR for Helminths

| Parameter | In-House RT-PCR | Biosynex Helminths AMPLIQUICK RT-PCR | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. mansoni Sensitivity | Not significantly different (p=1) | Not significantly different (p=1) | Performance comparable [28] |

| S. mansoni Specificity | Not significantly different (p=1) | Not significantly different (p=1) | Performance comparable [28] |

| S. stercoralis Sensitivity | Not significantly different (p=1) | Not significantly different (p=1) | Performance comparable [28] |

| S. stercoralis Specificity | Not significantly different (p=1) | Not significantly different (p=1) | Performance comparable [28] |

| Concordance for S. mansoni cases | Poor (AC1 = 0.38) | Poor (AC1 = 0.38) | Despite comparable metrics, discrepancies exist [28] |

| Concordance for S. stercoralis cases | Good (AC1 = 0.78) | Good (AC1 = 0.78) | [28] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Multicenter Comparison of Commercial and In-House PCR for Intestinal Protozoa

This protocol is adapted from a multicenter study comparing a commercial RT-PCR test (AusDiagnostics) and an in-house RT-PCR assay against traditional microscopy for identifying infections with Giardia duodenalis, Cryptosporidium spp., Entamoeba histolytica, and Dientamoeba fragilis [7].

1. Sample Collection and Storage

- Collect stool samples (e.g., 355 consecutive samples).

- Examine all samples using conventional microscopy (e.g., Giemsa staining for fresh samples; formalin-ethyl acetate (FEA) concentration technique for preserved samples) as a reference method.

- Preserve samples. Note: The study found that PCR results from preserved stool samples were better than those from fresh samples, likely due to superior DNA preservation [7].

- Store samples frozen at -20°C until molecular analysis.

2. DNA Extraction

- Use an automated nucleic acid extraction system (e.g., MagNA Pure 96 System with the MagNA Pure 96 DNA and Viral NA Small Volume Kit).

- Employ a stool transport and recovery buffer (e.g., S.T.A.R. Buffer).

- Include an internal extraction control.

- Critical Step: The study identified DNA extraction from the robust wall of protozoan oocysts as a critical challenge, directly impacting sensitivity [7].

3. In-House RT-PCR Amplification

- Reaction Mixture:

- 5 µL of extracted DNA.

- 12.5 µL of 2x TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix.

- 2.5 µL of custom primer and probe mix.

- Sterile water to a final volume of 25 µL.

- Cycling Conditions on a real-time PCR system (e.g., ABI 7900HT):

- 1 cycle: 95°C for 10 minutes (initial denaturation).

- 45 cycles: 95°C for 15 seconds (denaturation) and 60°C for 1 minute (annealing/extension).

4. Commercial RT-PCR Assay

- Perform the commercial test (e.g., AusDiagnostics kit) strictly according to the manufacturer's instructions on the same DNA extracts.

5. Data Analysis

- Compare the sensitivity, specificity, and positive/negative predictive values of the in-house and commercial PCR methods against the microscopy reference standard.

Protocol: Comparative Performance Evaluation of Commercial Multiplex PCR Assays

This protocol outlines the methodology for a head-to-head evaluation of multiple commercial multiplex PCR assays using a characterized DNA panel, as demonstrated in a study comparing four commercial kits [26].

1. Reference DNA Panel Preparation

- Establish a well-characterized DNA panel extracted from stool specimens of clinically confirmed patients.

- Include positive samples for target pathogens (e.g., Cryptosporidium hominis, C. parvum, Giardia duodenalis, Entamoeba histolytica) and negative controls.

- Include DNA from other organisms (e.g., E. dispar, Leishmania infantum) to assess cross-reactivity.

- Prepare multiple aliquots of each DNA sample to avoid freeze-thaw degradation.

2. Multiplex Real-Time PCR Testing

- Test all commercial kits (e.g., Diagenode Gastroenteritis/Parasite Panel I, R-Biopharm RIDAGENE Parasitic Stool Panel, Seegene Allplex Gastrointestinal Parasite Panel, FTD Stool Parasites) in parallel.

- Use a standardized input of DNA (e.g., 5 μL per reaction for most assays).

- Perform all reactions in a 25 μL final volume, following the manufacturer's instructions.

- Run assays on an appropriate real-time PCR cycler (e.g., Corbett Rotor-Gene 6000, CFX96, Mx3005P).

- Include negative, positive, and inhibition controls in each run.

3. Assessment of Mixed Infections and Limit of Detection

- Simulated Co-infections: Artificially generate mixes by combining equal amounts of positive DNA samples for different pathogens to mimic natural co-infections and assess assay specificity in a complex background [26].

- Relative Limit of Detection: Perform ten-fold serial dilutions of positive DNA samples to determine and compare the detection limits of each assay [26].

4. Analysis

- Calculate diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for each assay against the reference panel.

- Compare the results from simulated mixed infections and limit of detection experiments across the different kits.

Decision Workflow: Selecting a Diagnostic PCR Approach

The following diagram outlines the key decision points and considerations for researchers and laboratories when choosing between commercial and in-house PCR tests.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Molecular Diagnosis of Intestinal Parasites

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stool Transport & Recovery Buffer | Stabilizes nucleic acids in stool samples prior to DNA extraction, reducing PCR inhibitors. | S.T.A.R. Buffer (Roche) [7] [28] |

| Automated Nucleic Acid Extraction Systems | Standardizes and automates DNA purification, a critical step for sensitivity and reproducibility. | MagNA Pure 96 System (Roche) [7], KingFisher Flex (Thermo Fisher) [29], STARlet (Seegene) [29] |

| Internal Extraction Controls | Monitors efficiency of DNA extraction and identifies PCR inhibition. | Phocid alphaherpesvirus 1 (PhHV-1) [28] |

| Commercial Multiplex PCR Master Mixes | Pre-mixed solutions containing enzymes, dNTPs, and buffers optimized for multiplex real-time PCR. | TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix [7] |

| Commercial Protozoan PCR Panels | CE-IVD/FDA-marked kits for standardized, simultaneous detection of multiple enteric protozoa. | AusDiagnostics [7], RIDAGENE [27], BD MAX [26], Allplex (Seegene) [26] |

| Digital PCR Systems | Provides absolute quantification of target DNA without a standard curve; offers superior accuracy for viral load and co-infection studies. | QIAcuity (QIAGEN) [29] |

Regulatory and Implementation Considerations

The regulatory landscape for LDTs is dynamic and varies by region. In the United States, the FDA has historically exercised enforcement discretion, but this policy has been subject to recent legal challenges and rulemaking. As of late 2025, a federal court vacated a 2024 rule that would have regulated LDTs as medical devices, effectively restoring the status quo of FDA enforcement discretion for these tests [30] [31]. This is significant for hospital and health system labs, as stringent device regulations could have limited the availability of these tests [30]. In the European Union, the In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation (IVDR) imposes stringent requirements. Laboratories must justify the use of in-house assays over commercially available CE-IVD-marked kits and maintain detailed documentation of the entire test lifecycle [28]. From an implementation perspective, DNA extraction has been consistently identified as a critical step affecting sensitivity, particularly for parasites with robust cyst walls like Cryptosporidium and Dientamoeba fragilis [27] [7]. Furthermore, while molecular methods are highly sensitive for specific targets, microscopic examination retains value as it can reveal additional parasitic infections not covered by a targeted PCR panel [7].

Standardized Protocols for DNA Extraction from Stool Specimens

The diagnosis of intestinal protozoan parasites is undergoing a transformative shift from traditional microscopic examination to molecular techniques. Microscopy, while cost-effective and widely used, suffers from limitations in sensitivity and specificity and requires significant technical expertise [32] [7]. Molecular methods, particularly polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and related technologies, offer enhanced sensitivity and specificity, and have become increasingly central to diagnostic and research workflows [33] [32]. The reliability of these molecular assays is fundamentally dependent on the first and most critical step: the extraction of high-quality DNA from stool specimens [34] [35]. Stool samples present a unique challenge for molecular biology, as they contain inherent PCR inhibitors such as lipids, bil salts, and complex carbohydrates, while the robust cyst and oocyst walls of parasites like Giardia and Cryptosporidium are difficult to lyse [34] [36]. Failure to adequately address these challenges can lead to false-negative results, undermining the diagnostic process [34]. Therefore, the selection and optimization of a DNA extraction protocol is not merely a preliminary step but a decisive factor in the success of downstream applications. This Application Note details standardized protocols for DNA extraction, framed within the context of a thesis comparing microscopy and molecular methods for the diagnosis of protozoan parasites, to ensure reproducible, reliable, and high-quality results for researchers and scientists.

Comparative Analysis of DNA Extraction Methodologies

Performance Evaluation of Different Extraction Methods

The choice of DNA extraction method significantly impacts the quantity, quality, and ultimate amplifiability of DNA recovered from stool samples. A 2022 study directly compared four methods for extracting DNA from various intestinal parasites, including fragile protozoa like Blastocystis sp. and hardy helminths like Ascaris lumbricoides [34]. The methods evaluated were the conventional phenol-chloroform technique (P), a modified phenol-chloroform technique with a bead-beating step (PB), the QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Q), and the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QB) [34]. While the phenol-chloroform-based methods (P and PB) yielded approximately four times higher DNA quantities, the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QB) demonstrated superior performance in the most critical parameter: PCR detection rate [34]. The QB method achieved a 61.2% PCR detection rate, far exceeding the 8.2% rate of the conventional phenol-chloroform method [34]. This underscores that DNA yield alone is a poor indicator of method efficacy; the efficient removal of inhibitors and successful lysis of parasitic forms are paramount.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of DNA Extraction Methods for Protozoan Parasites from Stool Samples

| Extraction Method | Reported DNA Yield | PCR Inhibition Resistance | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Primary Application/Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenol-Chloroform (P) | High [34] [36] | Low [34] | High DNA yield; cost-effective [34] [36] | Time-consuming; hazardous organic solvents; poor inhibitor removal [34] | Research settings where cost is primary and inhibitors are less concern |

| Phenol-Chloroform with Bead-Beating (PB) | High [34] | Moderate [34] | Effective lysis of tough cyst/walls [34] | Time-consuming; requires specialized equipment (bead beater) [34] | Samples with hardy parasites (e.g., helminth eggs) |

| QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Q) | Moderate [34] | Moderate-High [34] | Commercial standardization; good inhibitor removal [34] | May be less effective for certain tough-walled parasites [34] | Routine diagnostic PCR for common protozoa |

| QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QB) | Moderate [34] | High [34] | Highest PCR detection rate; superior inhibitor removal; effective for wide parasite range [34] | Higher cost per sample than in-house methods [34] | Gold standard for sensitive detection of mixed parasitic infections |

| YTA Stool DNA Kit | Moderate [36] | Moderate [36] | Commercial; cost-effective alternative | 60% diagnostic sensitivity for G. duodenalis [36] | PCR-based detection when budget is a constraint |

Similar comparative studies focusing on specific parasites reinforce these findings. For instance, in the detection of Giardia duodenalis, the phenol-chloroform method showed a higher diagnostic sensitivity (70%) compared to two commercial kits (QIAamp and YTA, both at 60%) when targeting the SSU rRNA gene [36]. Furthermore, the method of extraction can influence the apparent composition of the sample. A 2020 study on Blastocystis sp. found that a manual DNA extraction method (QIAamp DNA Stool Minikit) identified significantly more positive specimens than an automated method (QIAsymphony), particularly in samples with a low parasite load [37].

Impact of Pre-Treatment and Sample Preservation

The DNA extraction process begins long before the application of lysis buffers. Sample preservation and pre-treatment are critical "front-end" factors that dictate the success of the entire molecular workflow.

Sample Preservation: The choice of transport medium directly affects DNA recovery. A 2024 study comparing ethanol and lysis buffer for preserving mammalian fecal samples found that lysis buffer was significantly superior [38]. Samples transported in lysis buffer yielded DNA concentrations and subsequent sequencing reads up to three times higher than those preserved in ethanol. The lysis buffer also provided more consistent DNA purity (A260/280 mean: 1.92, SD: 0.27) compared to ethanol (mean: 1.94, SD: 1.10) [38]. This highlights the importance of matching the preservation medium to the downstream molecular application.

Pre-Treatment (Bead-Beating): The inclusion of a mechanical lysis step, such as bead-beating, is one of the most significant modifications to improve DNA extraction efficiency from stool samples. The tough walls of protozoan cysts and oocysts can be resistant to chemical and enzymatic lysis alone [34] [36]. The bead-beating process uses rapid shaking of the sample with small, sterile glass or ceramic beads to physically disrupt these resilient structures. As evidenced in the 2022 study, adding a bead-beating step to the phenol-chloroform protocol (PB) substantially improved its performance over the standard protocol (P) [34]. For Giardia cyst disruption, protocols often employ multiple cycles of freeze-thawing in liquid nitrogen and a boiling water bath prior to DNA extraction to further facilitate wall breakdown [36].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Extraction from Stool

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Lysis Buffer (e.g., S.T.A.R. Buffer) | Sample preservation & transport; stabilizes DNA and inhibits nucleases [38] [7] | Superior to ethanol for DNA yield and quality in long-term storage [38] |

| Proteinase K | Enzymatic digestion of proteins; disrupts cellular structures [34] [36] | Critical for breaking down organic material and parasite stages; requires incubation at 55-65°C [34] |

| Silica Membrane Columns | Binding and purification of DNA; removal of PCR inhibitors [34] [37] | Core component of many commercial kits; allows washing and elution of pure DNA |

| Glass Beads (0.5mm) | Mechanical disruption (bead-beating) of tough cyst/oocyst walls [34] | Essential for hardy parasites; improves DNA recovery from a broad range of organisms [34] |

| Phenol:Chloroform:IAA | Organic extraction of DNA; separates DNA from proteins and other contaminants [34] [36] | Effective for high yield; involves hazardous chemicals and is time-consuming [34] |

| Inhibitor Removal Reagents (e.g., BSA) | Added to PCR to bind residual inhibitors and improve amplification [36] | Counteracts inhibitors that may persist even after efficient DNA extraction |

Recommended Standardized Protocols

Protocol 1: Phenol-Chloroform Extraction with Bead-Beating

This in-house protocol is effective for obtaining high DNA yields and lysing tough-walled parasites, though it requires more hands-on time and involves hazardous chemicals [34] [36].

Materials:

- Lysis Solution (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 150 µg/mL proteinase K, 0.5% Tween-20)

- Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol (25:24:1)

- Chloroform

- Ice-cold absolute ethanol and 70% ethanol

- 3M sodium acetate (pH 5.2)

- TE buffer (elution buffer)

- 0.5 mm sterile glass beads

- Microcentrifuge tubes

- Microcentrifuge

- Bead beater or vortex adapter for horizontal vortexing

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Transfer 200 mg of stool specimen into a 2 mL microcentrifuge tube. For specimens preserved in ethanol, wash the sample three times with sterile distilled water before use [34].

- Bead-Beating and Lysis: Add 250 mg of sterile 0.5 mm glass beads and 400 µL of lysis solution to the sample. Securely cap the tube and horizontally vortex at maximum speed for 10 minutes until the stool is homogenized [34].

- Incubation: Incubate the homogenized sample at 65°C for 3 hours, followed by a 10-minute incubation at 90°C to inactivate the proteinase K [34].

- Organic Extraction:

- Add 200 µL of phenol:chloroform:IAA to the lysate. Vortex thoroughly and centrifuge at 13,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 minutes [34].

- Carefully transfer the upper aqueous phase to a new microcentrifuge tube.

- Add 2 volumes of chloroform, mix thoroughly by inversion, and centrifuge again at 13,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 minutes. Transfer the upper aqueous phase to a new tube [34].

- DNA Precipitation:

- Add 2.5 volumes of ice-cold absolute ethanol and 0.1 volume of 3M sodium acetate (pH 5.2) to the aqueous phase. Mix and precipitate DNA at -20°C overnight [34].

- Pellet the DNA by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 minutes.

- DNA Washing and Elution:

- Carefully decant the supernatant and wash the DNA pellet with 1 mL of 70% ethanol. Air-dry the pellet at room temperature.

- Resuspend the purified DNA pellet in 100 µL of TE buffer [34].

Protocol 2: QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QB)

This commercial kit protocol is recommended for its high detection rate and effectiveness in removing PCR inhibitors, making it ideal for sensitive diagnostic applications [34].

Materials:

- QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QIAGEN) containing InhibitEX tablets, proteinase K, buffers, and spin columns

- Microcentrifuge tubes

- Microcentrifuge

- Water bath or heating block set to 70°C

- Ethanol (96-100%)

Methodology:

- Sample Lysis:

- Aliquot 200 mg of stool sample into a tube. Add 1 mL of PowerFecal Pro Solution to the sample and vortex continuously for 5-15 minutes to homogenize. This step includes mechanical lysis [34].

- Inhibitor Removal:

- Centrifuge the lysate briefly to pellet coarse particles. Transfer up to 700 µL of the supernatant to a new tube containing an InhibitEX tablet. Vortex immediately and continuously for 1 minute to dissolve the tablet and bind inhibitors.

- Incubate the mixture at room temperature for 5 minutes.

- Centrifuge at full speed for 1 minute to pellet the inhibitor-bound matrix.

- DNA Binding:

- Transfer the supernatant to a new microcentrifuge tube. Add 15 µL of proteinase K.

- Add 650 µL of Buffer FPP and mix by vortexing.

- Incubate at 70°C for 10-15 minutes.

- Column Purification:

- Briefly centrifuge the tube to remove drops from the lid.

- Add 650 µL of the lysate to an MBT Spin Column and centrifuge at full speed for 1 minute. Discard the flow-through and repeat with the remaining lysate.

- Washing and Elution:

- Add 500 µL of Buffer EA to the column. Centrifuge at full speed for 1 minute and discard the flow-through.

- Add 500 µL of Buffer EB to the column. Centrifuge at full speed for 1 minute and discard the flow-through.

- Place the column in a new collection tube and centrifuge at full speed for 1 minute to dry the membrane.

- Transfer the column to a clean elution tube. Apply 50-100 µL of Buffer ET to the center of the membrane, incubate at room temperature for 1-5 minutes, and centrifuge at full speed for 1 minute to elute the DNA [34].

Workflow Integration and Quality Control

The DNA extraction process is an integral component of a larger diagnostic and research workflow. As visualized below, it bridges the gap between sample collection and the final molecular analysis, and its quality directly influences all subsequent results.

Diagram 1: Integrated diagnostic workflow for intestinal protozoa, highlighting the parallel and complementary roles of microscopy and molecular methods.

To ensure the reliability of the extracted DNA, stringent quality control measures must be implemented:

- Spectrophotometry: Use a NanoDrop or similar instrument to assess DNA concentration (A260) and purity. Optimal A260/280 ratios are ~1.8, indicating minimal protein contamination. The A260/230 ratio should be >2.0, indicating removal of organic salts and other contaminants [34] [36].

- Inhibition Testing: A key quality control step is to test for the presence of residual PCR inhibitors. This can be done by spiking a known quantity of control plasmid DNA or a separate control amplicon into the extracted DNA and performing PCR. A delay or failure in the amplification of the spike indicates the presence of inhibitors [34]. Alternatively, some commercial multiplex PCR kits include an internal control within the reaction to monitor for inhibition [33] [37].

- Amplification of a Housekeeping Gene: Performing PCR for a conserved host or bacterial gene (e.g., 16S rRNA) can confirm the successful extraction of amplifiable DNA.

The transition from microscopy to molecular methods for protozoan parasite diagnosis represents a significant advancement in clinical and research parasitology. The efficacy of these powerful molecular tools, however, is fundamentally contingent upon the DNA extraction protocol employed. This Application Note has detailed that while mechanical pre-treatment like bead-beating is crucial for disrupting resilient parasitic forms, the use of specialized commercial kits (e.g., QIAamp PowerFecal Pro) generally provides the best combination of high DNA quality, effective inhibitor removal, and a superior PCR detection rate compared to traditional organic extraction methods [34]. Researchers must be aware that the entire process—from sample preservation and pre-treatment through extraction and amplification—forms an interconnected system where each step must be optimized for the specific sample type and parasitic targets of interest [35]. By adopting these standardized protocols and rigorous quality control measures, scientists can ensure the generation of robust, reliable, and reproducible molecular data, thereby strengthening both diagnostic accuracy and research outcomes in the field of intestinal parasitology.

The diagnosis of intestinal protozoan infections, such as Giardia duodenalis, Cryptosporidium spp., and Entamoeba histolytica, is a critical component of public health and clinical microbiology. The ongoing comparison between traditional microscopy and advanced molecular methods for protozoan diagnosis research hinges on a fundamental, pre-analytical factor: the initial choice between fresh or preserved stool specimens. Proper collection and preservation are paramount, as they directly impact the sensitivity and reliability of all subsequent diagnostic procedures [2]. This application note provides a detailed framework for optimizing stool sample collection, presenting structured data, validated protocols, and practical tools to guide researchers and scientists in making evidence-based decisions that enhance diagnostic accuracy.

Comparative Analysis: Diagnostic Performance in Context

The selection of sample type directly influences the detection capabilities of both microscopy and molecular techniques. The table below summarizes key performance characteristics.

Table 1: Impact of Sample Type on Diagnostic Method Performance

| Diagnostic Method | Recommended Sample Type | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopy (O&P Exam) | Fresh (for motility); Preserved (10% Formalin & PVA) [39] [40] | Low cost; Allows broad detection of parasites & helminths [2] | Low sensitivity (20-90%); Requires skilled technologist; Cannot differentiate pathogenic species [1] [2] |

| Molecular Methods (PCR/qPCR) | Preserved (SAF, 95% Ethanol) [1] [41] | High sensitivity & specificity; Species-specific differentiation; Automation-friendly [1] [42] | Higher cost; Limited target spectrum; May miss helminths [42] [2] |

Molecular assays have demonstrated superior sensitivity for detecting key protozoa. A large prospective study over three years found that multiplex qPCR detected Giardia intestinalis, Cryptosporidium spp., and Entamoeba histolytica in 1.28%, 0.85%, and 0.25% of samples, respectively, whereas microscopy detected the same organisms in only 0.7%, 0.23%, and 0.68% of samples [42]. Furthermore, a 2025 multicentre study confirmed that PCR results from preserved stool samples were often better than those from fresh samples, likely due to better DNA preservation [1].

Specimen Collection and Preservation Protocols

Universal Collection Guidelines

- Container: Collect stool in a dry, clean, leak-proof container. Care must be taken to avoid contamination with urine, water, or soil [39].

- Timing: Multiple specimens collected every 2-3 days are recommended to account for irregular shedding of parasites. A single stool specimen detects only 58-72% of protozoan infections [2].

- Interfering Substances: Specimens should be collected before the administration of, or after clearance from, substances like barium, bismuth, antacids, mineral oil, antimicrobial agents, and certain antidiarrheal preparations [39].

Processing Workflow: Fresh vs. Preserved Stool

The following workflow outlines the critical decision points and procedures for handling stool samples based on their initial state.

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Processing Fresh Stools for Microscopy

This protocol is optimal for observing motile trophozoites, which is not possible with preserved specimens [40].

Direct Wet Mount Preparation:

- Place a drop of 0.9% saline on a clean microscope slide.

- Emulsify a very small amount of fresh stool (about 2 mg) in the saline using an applicator stick.

- Add a coverslip. The mount should be thin enough to read newsprint through it.

- Examine systematically under microscope (10x and 40x objectives) for motile trophozoites, cysts, and helminth eggs.

Concentration for Enhanced Detection (Formalin-Ethyl Acetate Sedimentation): [40]

- Step 1: Strain approximately 3-5 ml of emulsified stool through wetted gauze into a 15 ml conical centrifuge tube. Add saline or 10% formalin to bring the volume to 15 ml.

- Step 2: Centrifuge at 500 × g for 10 minutes. Decant the supernatant.

- Step 3: Resuspend the sediment in 10 ml of 10% formalin and mix thoroughly.

- Step 4: Add 4 ml of ethyl acetate, stopper the tube, and shake vigorously for 30 seconds. Centrifuge again at 500 × g for 10 minutes.

- Step 5: Free the debris plug from the tube side and decant the top layers. Examine the resuspended sediment under a microscope.

Protocol 2: Preserving Stools for Molecular Diagnosis

For PCR-based methods, preservation with Sodium Acetate-Acetic Acid-Formalin (SAF) or 95% Ethanol is recommended for optimal DNA recovery [43] [41].

Preservation with SAF: [43]

- Add 1 volume of stool to 3 volumes of SAF preservative in a labeled, leak-proof container.

- Mix thoroughly until the specimen is homogenous. The fixed sample is stable for several months at room temperature.

- DNA Extraction Note: For DNA extraction from SAF-preserved stool, use a mechanical disruption step (e.g., bead beating) to break down robust protozoan walls, which is critical for efficient DNA recovery [1].

Preservation with 95% Ethanol: [41]

- Add 1 volume of stool to 2-3 volumes of 95% ethanol.

- Mix immediately and thoroughly to ensure the ethanol penetrates the entire sample, inactivating nucleases.

- This method provides a pragmatic and effective field-based option for stabilizing DNA, even at simulated tropical ambient temperatures (32°C) for up to 60 days.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Stool Sample Preservation and Processing

| Reagent/Fixative | Primary Function | Key Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10% Formalin | All-purpose fixative; preserves morphology of cysts, eggs, and larvae [39] | Concentration procedures; immunoassays; UV fluorescence | Not suitable for permanent stained smears with trichrome; can interfere with PCR after extended fixation [39] |

| Polyvinyl-Alcohol (PVA) | Preserves protozoan trophozoites and cysts; provides adhesive for slides [39] | Preparation of permanent stained smears (e.g., trichrome) | Contains mercuric chloride (disposal concerns); not suitable for concentration or immunoassays [39] [40] |

| SAF (Sodium Acetate-Acetic Acid-Formalin) | Fixative suitable for concentration and permanent staining [39] | Microscopy and molecular diagnostics; compatible with concentration and acid-fast stains | Requires an additive (e.g., albumin) for specimen adhesion to slides [39] |

| 95% Ethanol | Dehydrates and inactivates nucleases, preserving target DNA [41] | Optimal for PCR-based molecular studies | Pragmatic choice for field settings; balances DNA preservation with cost and toxicity [41] |

| RNAlater | Stabilizes nucleic acids by precipitating proteins and inactiating RNases [41] | Preservation of RNA and DNA for molecular studies | Provides some protective effect at elevated temperatures, but may be less effective than other methods for parasite DNA [41] |

| FTA Cards | Chemically treated cards for nucleic acid lysis and immobilization [41] | Room-temperature storage and shipping of samples for PCR | Effective for minimizing DNA degradation at 32°C; suitable for specific sample types [41] |

The optimization of stool sample collection is a critical first step that dictates the success of downstream diagnostic applications. While fresh specimens remain valuable for the immediate observation of motile forms under microscopy, preserved specimens offer unparalleled practicality, stability, and compatibility with both traditional and modern molecular techniques. The evidence strongly indicates that for the specific detection of pathogenic intestinal protozoa within a research framework comparing diagnostic methodologies, the use of appropriately preserved stool specimens—particularly with fixatives like SAF or 95% ethanol for molecular studies—provides the most reliable and robust foundation.

For many years, microscopy has been the cornerstone of diagnosing intestinal protozoan infections, requiring the examination of multiple stool samples collected on alternate days to overcome its limited sensitivity [44]. This approach is labor-intensive, time-consuming, and demands highly skilled personnel [7] [44]. The emergence of molecular diagnostic methods, particularly real-time PCR (RT-PCR), offers a paradigm shift by providing enhanced sensitivity and specificity, enabling accurate identification and differentiation of pathogenic protozoa, such as Entamoeba histolytica, from non-pathogenic species [6] [7].

This application note details the implementation of a single-sample molecular diagnostic workflow. Evidence demonstrates that a protocol utilizing one fecal sample for both a coproparasitological exam and RT-PCR achieves high sensitivity, reducing costs and saving time for patients and laboratories alike [44]. We provide a detailed protocol and resources to facilitate the integration of this efficient approach into routine laboratory practice.

Performance Comparison: Microscopy vs. Molecular Methods

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Diagnostic Methods for Key Intestinal Protozoa

| Pathogen | Microscopy Sensitivity & Specificity Limitations | Molecular Method (RT-PCR/RPA) Performance | Notes on Molecular Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Giardia duodenalis | Poor sensitivity; requires skilled microscopist [45] [44] | High sensitivity and specificity; complete agreement between commercial and in-house PCR [6] [7] | Performs well on both fresh and preserved stool samples [7] |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | Low sensitivity (47.2-68.8% for some commercial EIAs); requires acid-fast staining [45] | High specificity; RPA showed 100% correlation with PCR in a clinical study [45] | Sensitivity can be limited by inadequate DNA extraction from oocysts [6] [7] |

| Entamoeba histolytica | Cannot differentiate from non-pathogenic E. dispar and E. moshkovskii [7] [44] | Critical for accurate diagnosis; enables specific identification of pathogenic species [6] [7] | Resolves a major limitation of microscopy [44] |

| Dientamoeba fragilis | Requires permanent staining for visualization; sensitivity variable [7] | High specificity; detection can be inconsistent, potentially due to DNA extraction issues [6] [7] | Molecular methods are more sensitive than microscopy for this pathogen [44] |

Table 2: Impact of Single-Sample Molecular Workflow on Laboratory Efficiency

| Parameter | Traditional Microscopy (3 Samples) | Single-Sample Molecular Approach | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Samples | 3 collected on alternate days | 1 | [44] |

| Workflow Complexity | High (multiple processing steps per sample) | Simplified (single processing workflow) | [44] |

| Personnel Skill Demand | High (requires expert microscopist) | Standardized (reduced reliance on specialized morphology skills) | [7] [44] |

| Differentiation of Entamoeba species | Not possible without additional tests | Direct and specific identification | [7] [44] |

| Reported Sensitivity | Lower (dependent on parasite load and examiner skill) | High sensitivity maintained despite sample reduction | [44] |

Experimental Protocols

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

This protocol is adapted from a multicentre study comparing molecular methods for detecting intestinal protozoa [7].

Reagents and Equipment:

- Stool sample (fresh or preserved in Para-Pak media)

- S.T.A.R. Buffer (Stool Transport and Recovery Buffer; Roche Applied Sciences)

- Internal Extraction Control

- MagNA Pure 96 DNA and Viral NA Small Volume Kit (Roche Applied Sciences)

- MagNA Pure 96 System (Roche Applied Sciences)

- Sterile loops

- Microcentrifuge tubes

- Centrifuge

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Using a sterile loop, mix approximately 1 µl of fecal sample with 350 µl of S.T.A.R. Buffer.

- Incubation: Incubate the mixture for 5 minutes at room temperature.

- Clarification: Centrifuge the sample at 2000 rpm for 2 minutes.

- Supernatant Collection: Carefully transfer 250 µl of the supernatant to a fresh tube. Add 50 µl of the internal extraction control to the supernatant.

- Automated Extraction: Load the prepared sample into the MagNA Pure 96 System and execute the DNA extraction protocol using the MagNA Pure 96 DNA and Viral NA Small Volume Kit, following the manufacturer's instructions. The DNA is eluted in a final volume of 100 µl.

In-House Real-Time PCR (RT-PCR) Amplification

This protocol describes a multiplex RT-PCR for the simultaneous detection of Giardia duodenalis, Dientamoeba fragilis, and Blastocystis sp. [44]. A second multiplex can be performed for Entamoeba histolytica/E. dispar and Cryptosporidium sp. [44].

Reagents and Equipment:

- Extracted DNA template

- 2× TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific)

- Primers and probes specific for target protozoa (see Table 3 for sequences and concentrations)

- Sterile, nuclease-free water

- ABI 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific) or equivalent real-time cycler

Procedure:

- Reaction Mix Preparation: For each reaction, combine the following components in a PCR tube or plate:

- 5 µl of extracted DNA

- 12.5 µl of 2× TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix

- 2.5 µl of primer and probe mix (for multiplex, see Table 3 for final concentrations)

- Sterile water to a final volume of 25 µl

- Thermal Cycling: Place the plate in the real-time PCR instrument and run the following program:

- Initial Denaturation: 1 cycle of 95°C for 10 minutes.

- Amplification: 45 cycles of:

- 95°C for 15 seconds (denaturation)

- 60°C for 1 minute (annealing/extension)

- Data Analysis: Analyze the amplification curves and determine cycle threshold (Ct) values. Include positive and negative controls in each run to ensure assay validity.

Table 3: Primer and Probe Sequences for Multiplex RT-PCR [44]

| Target | Primer/Probe | Sequence (5' to 3') | Final Concentration in Reaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Giardia duodenalis | Forward Primer | AAC GGC GCA GGC GGA AAA | 300 nM each |

| Reverse Primer | GTT CGA GTT CGA TTC CGG AGT T | ||

| Probe | (CY5.5) CCC GCG GCG GTC CCT GCT AG (BHQ3) | 200 nM | |

| Dientamoeba fragilis | Forward Primer | CGG CCG AAG CGC TAT T | 100 nM each |

| Reverse Primer | CCT TCC TCA AAG TGT TTT ACG AA | ||

| Probe | (VIC) CGG AAT TCT TGG CCT TC (MGB) | 100 nM | |

| Blastocystis sp. | Forward Primer | GGA GGT AGT GAC AAT AAAT C | 300 nM each |

| Reverse Primer | TGC TAT TCA CCA AAT TAA GC | ||

| Probe | (FAM) CAT CTA GTT CAA TTA AGC ACA (MGB) | 100 nM |

Workflow Integration Diagram