Host Species Heterogeneity and Parasite Virulence: A Comparative Analysis of Evolutionary Drivers and Biomedical Applications

This review synthesizes current research on the comparative analysis of parasite virulence across host species, addressing a core challenge in evolutionary ecology and disease management.

Host Species Heterogeneity and Parasite Virulence: A Comparative Analysis of Evolutionary Drivers and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This review synthesizes current research on the comparative analysis of parasite virulence across host species, addressing a core challenge in evolutionary ecology and disease management. We explore the foundational principles governing virulence evolution, particularly the trade-offs between transmission, recovery, and host exploitation. The article details advanced methodological approaches, from experimental evolution to omics technologies, that are revolutionizing virulence research. We critically examine troubleshooting challenges such as coinfection and drug resistance, and validate findings through cross-comparative studies of diverse host-parasite systems. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this analysis provides a comprehensive framework for understanding virulence mechanisms and their implications for therapeutic intervention and public health strategy.

Theoretical Frameworks and Ecological Drivers of Virulence Evolution

Within the field of evolutionary ecology, defining virulence has proven to be a complex challenge with significant implications for research and drug development. The most general conceptual definition characterizes virulence as the reduction in host fitness caused by infection [1]. This host-centred perspective encompasses both mortality and fecundity costs, framing virulence as the ultimate measure of parasite impact on host evolutionary success. However, this comprehensive definition stands in contrast to the operational definitions typically employed in mathematical models, where virulence is most often quantified as the infection-induced increase in host mortality rate (α) [2] [1]. This divergence between conceptual foundations and practical measurement creates a fundamental tension in virulence research, particularly in comparative studies across host species and parasite systems.

The theoretical framework for understanding virulence evolution is dominated by the trade-off hypothesis, which posits that virulence represents an evolutionary balancing act [1] [3]. Pathogens face a trade-off between the benefits of increased host exploitation (typically leading to higher transmission rates) and the costs of reduced infection duration due to host mortality [1]. This classic virulence-transmission trade-off suggests that natural selection should favour intermediate levels of virulence that maximize the basic reproductive number (R₀) of the pathogen [3]. However, this traditional model has been complicated by the recognition that infection-induced mortality often stems not from direct pathogen exploitation alone, but from immunopathological responses where the host's own immune defences cause collateral tissue damage [4]. This more nuanced understanding necessitates refined approaches to defining and measuring virulence across different host-parasite systems.

Theoretical Frameworks: From Trade-Offs to Immunopathology

The Traditional Trade-Off Hypothesis

The dominant paradigm in virulence evolution theory centres on the assumed relationship between host exploitation and pathogen fitness. According to this framework, pathogens that more aggressively exploit their hosts gain transmission benefits but incur mortality costs [1]. The fundamental trade-off emerges because higher exploitation increases both transmission rate (β) and pathogen-induced host mortality rate (α), creating a non-linear optimization problem where R₀ is maximized at intermediate virulence levels [3]. This relationship can be expressed mathematically through the standard epidemiological model:

R₀ = β(α)S / (α + γ + μ)

Where β is the transmission rate (an increasing function of α), γ is the recovery rate, μ is background host mortality, and S is susceptible host density [3]. The evolutionary stable strategy occurs where the marginal gain in transmission equals the marginal cost in reduced infection duration [1]. This theoretical framework predicts that virulence should vary systematically with ecological factors, potentially explaining why vector-borne pathogens often evolve higher virulence—they are less constrained by host mobility [1].

Expanding the Framework: Immunopathology and Alternative Costs

Recent theoretical work has complicated the traditional trade-off model by recognizing that infection-induced mortality often results from immunopathology rather than direct pathogen exploitation [4]. In this model, host mortality comprises two elements: direct damage from parasite exploitation and collateral damage from immune responses. This distinction matters profoundly for virulence evolution, as the relationship between exploitation and mortality may be positive or negative depending on how immunopathology correlates with parasite clearance [4]. Some pathogens may evolve immunosuppression to reduce immunopathology, while others might trigger excessive immune responses that become lethal.

The classical assumption that mortality costs primarily constrain virulence evolution has also been challenged. For many diseases, particularly in human populations, infection fatality rates are too low for mortality costs to plausibly limit virulence evolution [3]. Instead, detection costs—where symptomatic infections cause hosts to reduce contacts—may impose stronger evolutionary constraints than mortality itself [3]. This perspective emphasizes that behavioural responses to infection can shape pathogen evolution as significantly as physiological ones.

Table 1: Key Theoretical Frameworks in Virulence Evolution

| Framework | Core Mechanism | Evolutionary Predictions | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Trade-Off | Balance between transmission benefits and mortality costs | Intermediate virulence optimizes R₀; affected by transmission mode | Assumes direct link between exploitation and mortality; ignores host responses |

| Immunopathology Model | Host immune responses cause collateral damage | Virulence may increase or decrease with exploitation depending on immune interaction | Complex relationships difficult to parameterize empirically |

| Detection Cost Model | Symptomatic hosts reduce contacts | Virulence constrained by morbidity-induced behavioural changes | Limited empirical validation across systems |

Methodological Approaches: Quantifying Virulence in Model Systems

Experimental Models and Virulence Metrics

Comparative virulence research employs diverse model systems, each with distinct methodological approaches and measurement challenges. The choice of model system significantly influences how virulence is operationalized and quantified, as illustrated by three established experimental systems:

Galleria mellonella (Greater Wax Moth): This invertebrate model provides a high-throughput alternative to mammalian systems for studying bacterial pathogens like Pseudomonas aeruginosa [5]. Virulence quantification in Galleria presents unique challenges because extreme sensitivity to P. aeruginosa makes LD₅₀ (50% lethal dose) measurements difficult, as even 1-5 colony-forming units can be lethal [5]. Consequently, researchers have developed standardized LT₅₀ (50% lethal time) protocols, where larvae are injected with a range of bacterial doses and time-to-death is monitored hourly [5]. The logarithmic relationship between dose and LT₅₀ enables accurate virulence comparisons across strains, with statistical differentiation based on non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals [5].

Daphnia-Pasteuria System: The water flea Daphnia magna and its bacterial parasite Pasteuria ramosa provide powerful insights into virulence in natural populations [6]. Laboratory studies indicate extreme virulence, with infected juveniles losing 90-100% of their residual reproductive value [6]. However, field assessments often show much weaker effects because environmental constraints (like resource limitation) reduce fecundity in both infected and uninfected hosts, masking parasite-specific virulence [6]. This system highlights how environmental context dramatically influences virulence measurements, with laboratory conditions potentially amplifying relative fitness differences.

House Finch-Mycoplasma System: The emergence of Mycoplasma gallisepticum in house finches provides a natural experiment for studying host-pathogen coevolution [7]. Virulence assessment in this system integrates multiple metrics: conjunctivitis severity, pathogen load quantification through qPCR, and host immune responses (M. gallisepticum-specific IgY antibodies) [7]. This multifaceted approach reveals that antibody levels reflect both host resistance and pathogen virulence, complicating their interpretation as simple resistance markers [7].

Table 2: Virulence Metrics Across Experimental Systems

| Model System | Primary Virulence Metrics | Methodological Considerations | Key Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Galleria-Pseudomonas | LT₅₀ (50% lethal time) at specified doses | Requires multiple dose measurements to account for inoculation error; standardized temperature (37°C) | Extreme sensitivity enables high-resolution virulence discrimination |

| Daphnia-Pasteuria | Castration (fecundity reduction), mortality, gigantism | Discrepancy between lab and field measurements; environmental conditions affect virulence expression | Parasite-induced fecundity reduction depends strongly on environmental context |

| House Finch-Mycoplasma | Conjunctivitis severity, pathogen load, antibody responses | Antibody levels reflect both host resistance and pathogen virulence; paired experimental designs | Immune responses do not necessarily signal clearance ability |

Experimental Workflows in Virulence Research

The experimental workflow for virulence quantification varies by system but follows consistent principles across models. The diagram below illustrates a generalized approach for virulence assessment using the Galleria-Pseudomonas model as a template:

Diagram 1: Generalized workflow for virulence quantification in invertebrate models

This methodology emphasizes several critical aspects of robust virulence assessment: standardized culture conditions, precise inoculation techniques, controlled environmental parameters, appropriate sample sizes (typically 10 larvae per dose), and statistical approaches that account for measurement error in dose preparation [5]. The multiple-dose approach is particularly valuable as it enables virulence comparison without requiring exact dose matching across strains.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Successful virulence research requires specialized reagents and methodologies tailored to specific host-parasite systems. The table below summarizes key resources across different experimental approaches:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies in Virulence Studies

| Reagent/Method | Application | Function in Virulence Research | Example System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Artificial Daphnia Medium (ADaM) | Daphnia maintenance | Standardized culture conditions minimizing environmental variation | Daphnia-Pasteuria [6] |

| Lysogeny Broth (LB) | Bacterial culture | Standardized growth medium for pathogen propagation | Galleria-Pseudomonas [5] |

| Syringe Pump Inoculation | Precise pathogen delivery | Ensures consistent inoculation volume and reduces technical variability | Galleria-Pseudomonas [5] |

| qPCR Assays | Pathogen load quantification | Measures infection intensity within hosts | House Finch-Mycoplasma [7] |

| ELISA for IgY | Antibody response measurement | Quantifies host immune activation specific to pathogen | House Finch-Mycoplasma [7] |

| DRC Package (R) | LT₅₀ calculation | Statistical analysis of dose-response relationships | Galleria-Pseudomonas [5] |

Comparative Analysis: Integrating Theoretical and Empirical Approaches

The integration of theoretical predictions with empirical measurements remains a central challenge in virulence research. The table below synthesizes key insights from diverse experimental systems regarding the expression and evolution of virulence:

Table 4: Comparative Virulence Across Host-Parasite Systems

| Host-Parasite System | Virulence Manifestation | Environmental Sensitivity | Evolutionary Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daphnia-Pasteuria | Castration, gigantism, mortality | High: Feeding conditions dramatically affect relative fecundity reduction | Chronic infections; prevalence increases with host age/size [6] |

| House Finch-Mycoplasma | Conjunctivitis, pathogen load, immune response | Moderate: Antibody responses reflect both host resistance and pathogen virulence | Coevolutionary arms race: increasing virulence selects for host resistance [7] |

| Galleria-Pseudomonas | Rapid mortality (hours to days) | Low: Standardized conditions enable reproducible LT₅₀ measurements | Extreme virulence maintained despite potential detection costs [5] |

| Human Influenza | Respiratory symptoms, cytokine storms | Moderate: Immunopathology varies with host immune status | Virulence constrained by detection costs rather than mortality [4] [3] |

This comparative analysis reveals several unifying themes. First, the environmental context significantly influences virulence expression, particularly for parasites that affect host fecundity rather than survival [6]. Second, multiple metrics of virulence—including mortality, fecundity reduction, and pathogen load—provide complementary information, with the most appropriate measure depending on the specific research question and biological system. Third, the timescale of infection shapes which virulence measures are most informative, with acute infections favouring mortality-based metrics and chronic infections requiring integration of fecundity and mortality effects.

The relationship between theoretical predictions and empirical observations remains complex. While traditional trade-off models successfully explain some patterns of intermediate virulence [1], the incorporation of immunopathological mechanisms [4] and detection costs [3] provides a more comprehensive framework for understanding why pathogens harm their hosts. This expanded theoretical foundation better accommodates empirical observations from diverse biological systems, moving the field toward a more nuanced understanding of virulence evolution across the tree of life.

The virulence-transmission trade-off hypothesis represents a cornerstone concept in evolutionary biology and disease ecology. Proposed over three decades ago, this theory suggests that pathogen evolution is constrained by a fundamental trade-off: the same parasite replication that enables transmission to new hosts also inflicts harm on the current host (virulence). This framework predicts that natural selection should favor intermediate levels of virulence that balance these competing demands to maximize overall transmission success [8] [9]. While this hypothesis has profoundly influenced theoretical work and disease management strategies, empirical evidence has revealed surprising complexities, leading to modern extensions that incorporate environmental persistence, host heterogeneity, and transmission timing.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of experimental approaches and findings in virulence-transmission research, offering methodological insights and resource information to support scientific investigation in this field.

Historical Foundations of the Trade-Off Hypothesis

The formal theoretical foundation of the virulence-transmission trade-off was primarily established in the 1980s through the work of Anderson and May [10] [8]. Their models proposed that:

- Parasite fitness depends on successful transmission, which requires balancing replication within the host against the harm this replication causes

- Virulence (parasite-induced host mortality) evolves as an unavoidable cost of parasite transmission

- Evolutionary constraints emerge because excessive replication increases transmission rate but reduces transmission opportunities by killing the host prematurely

This framework became the dominant paradigm for understanding host-parasite coevolution and informed numerous disease control strategies. However, the assumption that transmission depends exclusively on host survival began to face challenges as researchers documented exceptions where environmental persistence decoupled this relationship [10].

Modern Empirical Tests and Extensions

Critical Assessment Through Meta-Analysis

A comprehensive 2019 meta-analysis quantitatively evaluated empirical support for the trade-off hypothesis by synthesizing data from 29 studies after reviewing over 6,000 published papers [8] [9]. The analysis revealed:

Table 1: Key Findings from the Virulence-Transmission Trade-Off Meta-Analysis

| Relationship Tested | Support Found | Key Findings | Uncertainties Remaining |

|---|---|---|---|

| Within-host replication vs. virulence | Strong support | Positive correlation between replication rate and host harm | Whether the relationship generally decelerates |

| Within-host replication vs. transmission | Strong support | Increased replication enhances transmission potential | High within-study variability patterns |

| Virulence vs. transmission | Insufficient data | -- | Need for more empirical studies |

| Virulence vs. recovery rate | Insufficient data | -- | Need for more empirical studies |

The meta-analysis concluded that while partial support exists for the trade-off hypothesis, particularly for the replication-virulence and replication-transmission relationships, the empirical evidence remains insufficient to generalize all core predictions [8]. This highlighted a significant gap between theoretical advances and empirical validation.

Environmental Persistence and the Curse of the Pharaoh

Modern extensions of virulence evolution theory incorporate the crucial role of environmental stages in parasite life cycles. The "Curse of the Pharaoh" hypothesis predicts that long-lived infective stages in the external environment reduce the cost of host mortality, thereby selecting for higher virulence [10]. When parasites can persist in the environment after host death, the evolutionary constraint between virulence and transmission is relaxed.

A 2025 experimental study using the microsporidian Vavraia culicis and its mosquito host Anopheles gambiae provided critical insights into this relationship [10]. Researchers selected parasite lines for either early or late transmission, corresponding to shorter or longer times within the host. Counter to classical expectations, they discovered that:

- Late-transmission parasites evolved higher virulence and more rapid replication

- These within-host adaptations came with a survival cost in the external environment

- This inverse relationship between within-host performance and environmental survival reveals a novel trade-off axis in parasite evolution [10]

Virulence-Transmission Trade-off Extensions: Modern theories incorporate environmental persistence and within-host performance, revealing complex evolutionary constraints.

HIV-1 Virulence Evolution in Human Populations

A landmark study analyzing data from a large HIV-1 cohort in Uganda provided compelling evidence for the trade-off hypothesis in a natural human pathogen system [11]. Researchers examined the relationship between set-point viral load (SPVL - a key determinant of HIV virulence) and transmission parameters:

Table 2: HIV-1 Virulence-Transmission Relationships in the Ugandan Cohort

| SPVL (copies/mL) | Transmission Rate (/year) | Time to AIDS (years) | Evolutionary Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (~10²) | 0.019 | ~40 | Suboptimal transmission |

| Intermediate | 0.14 (peak) | Intermediate | Evolutionary optimum |

| High (~10⁷) | 0.14 (plateau) | ~5 | Limited transmission duration |

The study demonstrated that:

- Higher SPVL values were associated with significantly increased transmission rates but substantially shorter asymptomatic periods

- Evolutionary models predicted stabilizing selection toward intermediate virulence

- Empirical data confirmed viral attenuation over 20 years, with SPVL declining in the population [11]

This research provided robust evidence that virulence-transmission trade-offs operate in natural human pathogens and can predict evolutionary trajectories.

Host-Parasite Specificity in Infection Dynamics

Recent multi-host studies have revealed that infection dynamics emerge from complex interactions between specific host and parasite characteristics rather than general host traits alone [12]. Research using three rodent species from Israel's Negev Desert and their bacterial pathogens (Bartonella krasnovii and Mycoplasma haemomuris-like bacterium) demonstrated:

- Both pathogens showed reduced performance in Gerbillus gerbillus compared to other rodent species, supporting the "host trait variation" hypothesis

- However, most aspects of infection dynamics exhibited unique patterns for each host-parasite combination, supporting the "specific host-parasite interaction" hypothesis

- This specificity suggests that generalized predictions about virulence evolution must account for the unique biology of each system [12]

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Selection Experiments with Vavraia culicis

The 2025 V. culicis-mosquito experimental system provides a robust protocol for studying virulence evolution [10] [13]:

Parasite Selection Regime:

- Early transmission lines: Parasites from the first third of mosquitoes to die (host death before 7 days) were selected for transmission

- Late transmission lines: Parasites from the last third of mosquitoes to die (host death after 20 days) were selected

- Control population: Unselected stock parasites maintained in parallel

Infection and Maintenance:

- Mosquito larvae (Anopheles gambiae) were exposed to 10,000 spores per larva

- Dead mosquitoes were collected daily up to day 20

- Spores were extracted homogenization with stainless steel beads using a TissueLyser

- Spore concentrations were quantified with a hemocytometer under phase-contrast microscopy

Environmental Survival Assay:

- Spore aliquots (500,000 spores/mL) were prepared in antibiotic-antimycotic solution

- Aliquots were stored at 4°C or 20°C in darkness

- Infectivity was assessed at 0, 45, and 90 days post-storage [10]

HIV-1 Virulence Assessment Protocol

The HIV-1 study methodology offers insights into human pathogen evolutionary tracking [11]:

Cohort Design:

- Longitudinal data from the Rakai Community Cohort Study in Uganda (1995-2012)

- Analysis of 647 HIV incident cases and 817 serodiscordant couples

Virulence Measurement:

- Set-point viral load (SPVL): Stable viral load during asymptomatic infection

- Transmission rate estimation: Based on observed transmission events in serodiscordant couples

- Disease progression: Time from infection to AIDS, estimated from incident cases

Evolutionary Modeling:

- Compartmental ODE models stratified by SPVL

- Integration of transmission and survival functions

- Prediction of evolutionary trajectories using setting-specific parameters [11]

Virulence Evolution Experimental Workflow: Comprehensive assessment requires parasite selection, environmental assays, and host response measurement.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Virulence-Transmission Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| Vavraia culicis parasite lines | Model microsporidian for selection experiments | Studying environmental persistence trade-offs [10] |

| Anopheles gambiae host system | Mosquito host for parasite evolution studies | Maintaining selected parasite lines [10] [13] |

| Antibiotic-antimycotic cocktail | Prevents microbial contamination in spore storage | Maintaining spore viability assays [10] |

| TissueLyser with stainless steel beads | Homogenizes host tissue for spore extraction | Quantifying spore production [10] |

| Hemocytometer with phase-contrast microscopy | Quantifies spore concentrations | Standardizing infection doses [10] |

| Gerbil rodent model system (Gerbillus spp.) | Multi-host studies of infection dynamics | Testing host specificity hypotheses [12] |

| Bartonella krasnovii A2 | Model flea-borne bacterial pathogen | Acute infection dynamics studies [12] |

| Mycoplasma haemomuris-like bacterium | Model chronic infection pathogen | Within-host persistence investigations [12] |

The virulence-transmission trade-off hypothesis remains a vital framework for understanding parasite evolution, though modern research has revealed substantial complexity beyond the original formulations. Key insights emerging from contemporary studies include:

- The classical trade-off between within-host replication and between-host transmission represents only one axis of a multi-dimensional fitness landscape

- Environmental persistence can fundamentally alter evolutionary constraints, selecting for different virulence strategies

- Host-parasite specificity often supersedes general patterns, requiring case-specific investigation

- Empirical evidence partially supports theoretical predictions but highlights significant knowledge gaps, particularly regarding virulence-recovery relationships

These findings underscore the importance of considering ecological context, environmental stages, and specific host-parasite biology when predicting virulence evolution. Future research should prioritize experimental designs that capture the full transmission cycle and integrate multiple fitness components to advance our understanding of host-parasite coevolution.

Host heterogeneity, the genetic diversity present within a host population, represents a fundamental evolutionary force shaping parasite virulence trajectories. In both natural ecosystems and clinical settings, parasites encounter host populations that vary in their genetic composition, immune responses, and susceptibility to infection. This heterogeneity creates a complex selective landscape that profoundly influences how parasite populations adapt and evolve. Contemporary research has demonstrated that the genetic architecture of host populations can either accelerate or constrain the evolution of pathogenic virulence, with significant implications for disease management in agricultural, conservation, and medical contexts.

The evolutionary dynamics between hosts and parasites represent one of the most compelling examples of co-evolution in nature. According to the Red Queen hypothesis, interacting species must constantly evolve to maintain their position in what constitutes an evolutionary arms race [14]. While traditionally modeled as pairwise interactions, these relationships are increasingly recognized as being influenced by a broader ecological context, including host genetic diversity, symbiont communities, and intraguild predation [14]. This review provides a comparative analysis of experimental studies examining how host heterogeneity shapes parasite evolution, with a specific focus on virulence trajectories across diverse host-parasite systems.

Theoretical Framework and Key Concepts

The relationship between host heterogeneity and parasite evolution is underpinned by several foundational biological concepts. The monoculture effect describes the phenomenon where genetically homogeneous host populations experience higher parasite prevalence and more rapid parasite adaptation compared to heterogeneous populations [15]. This effect mirrors observations in agricultural systems, where crop genetic uniformity can facilitate devastating disease outbreaks [16].

The phylogenetic distance effect posits that host susceptibility is often inversely correlated with phylogenetic distance from the parasite's natural host, as closely related species typically offer more similar cellular environments and resources [17]. However, exceptions occur through the phylogenetic clade effect, where certain host clades possess conserved traits affecting susceptibility regardless of their distance from the natural host [17].

The evolutionary arms race between hosts and parasites is further complicated by factors including trade-offs in parasite fitness, where adaptation to one host genotype may reduce fitness on others, and mutational target size, which determines the genetic flexibility of parasites to overcome host defenses [17]. These concepts collectively provide a framework for interpreting empirical findings across experimental systems.

Comparative Experimental Models and Systems

Bacterial-Nematode Model Systems

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Experimental Systems in Host Heterogeneity Research

| Host-Parasite System | Experimental Design | Key Metrics | Major Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. elegans vs. S. marcescens [15] | Laboratory evolution with homogeneous vs. heterogeneous host populations | Host mortality rates | 29% virulence increase in homogeneous CB4856 hosts; 19% increase in homogeneous ewIR68 hosts; heterogeneous hosts impeded virulence evolution |

| C. elegans vs. S. aureus [16] | Passage through 24 host genotypes in monoculture vs. polyculture | Virulence, infectivity, host range | Pathogen virulence varied across host genotypes; diverse host populations selected for highest virulence but constrained infectivity |

| Invasive raccoon parasites [18] | Field study of natural populations with different MHC-DRB alleles | Parasite prevalence and intensity | Specific MHC-DRB alleles associated with resistance to Digenea; allele frequencies changed over time due to selection |

The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans has emerged as a powerful model system for investigating host-parasite evolutionary dynamics. In a landmark study, hosts were exposed to the bacterial parasite Serratia marcescens in either genetically homogeneous populations (single genotype) or heterogeneous populations (mixed genotypes) over multiple generations [15]. Parasites evolved in homogeneous host populations showed significant increases in virulence—29% in CB4856 hosts and 19% in ewIR68 hosts—compared to the ancestral strain. In striking contrast, parasites evolved in heterogeneous host populations showed no significant increase in virulence, demonstrating that host heterogeneity impedes parasite adaptation [15].

A complementary study using Staphylococcus aureus passaged through wild nematode populations revealed that host genotype significantly influences pathogen evolutionary trajectories [16]. Pathogens selected in distantly-related host genotypes diverged more than those in closely-related genotypes, and diverse host populations selected for the highest levels of pathogen virulence but constrained infectivity [16]. These findings suggest that population heterogeneity might pool together individuals that contribute disproportionately to the spread of infection or to enhanced virulence.

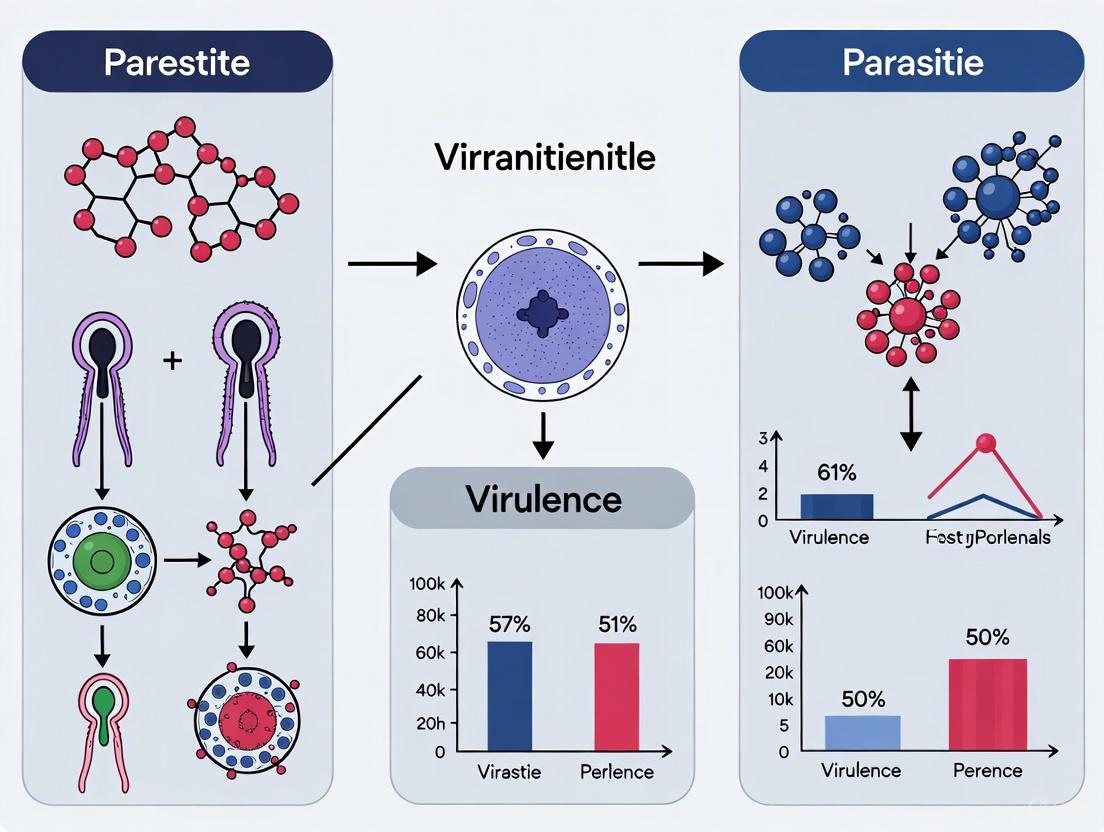

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow and Evolutionary Outcomes in Host Heterogeneity Studies. This diagram illustrates the divergent evolutionary trajectories of parasites exposed to homogeneous versus heterogeneous host populations, leading to specialized adaptation or generalist strategies.

Natural Systems and Vertebrate Hosts

Field studies on invasive raccoon populations in Europe provide compelling evidence for host heterogeneity effects in natural systems. Research revealed that different raccoon populations formed distinct genetic clusters with varying MHC-DRB allele frequencies due to founder effects and genetic drift [18]. These genetic differences translated into significant variation in parasite infection patterns, with specific MHC-DRB alleles conferring resistance to Digenea parasites [18]. Over time, the frequency of susceptibility alleles decreased, demonstrating parasite-mediated selection and highlighting how functional genetic variation shapes host-parasite relationships in natural populations.

In a hospital outbreak setting, Klebsiella pneumoniae evolved within patients over a five-year period, showing strong positive selection targeting key virulence factors including capsule polysaccharides, lipopolysaccharides, and iron uptake systems [19]. Notably, combinations of mutations in these enriched targets were more common in clinical isolates than colonizing isolates, suggesting niche adaptations for growth outside the gastrointestinal tract [19]. This within-host evolution demonstrates how opportunistic pathogens dynamically adapt to specific host environments, with implications for virulence trajectories.

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Table 2: Virulence Evolution Metrics Across Experimental Studies

| Study System | Host Type | Evolutionary Time Scale | Virulence Increase | Genetic Changes Obsed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. marcescens in C. elegans [15] | Homogeneous | 10 passages (hundreds of generations) | 19-29% increased mortality | Not specified |

| S. aureus in C. elegans [16] | Diverse monocultures vs. polyculture | 10 host generations | Varied across host genotypes; highest in polyculture | Genomic divergence correlated with host genetic distance |

| K. pneumoniae in humans [19] | Immunocompromised patients | 5-year outbreak | Adaptation to specific host niches | Convergent mutations in capsule, LPS, and iron uptake genes |

The quantitative data from these experimental systems reveal consistent patterns in how host heterogeneity influences virulence evolution. Across studies, genetically homogeneous host populations consistently selected for increased parasite specialization and virulence, while heterogeneous host populations constrained this evolutionary trajectory. The S. marcescens-C. elegans system demonstrated that homogeneous host populations led to 19-29% increases in host mortality rates, whereas heterogeneous populations showed no significant virulence evolution [15].

The time scale of evolution varies considerably across systems, from hundreds of bacterial generations in laboratory settings to multi-year outbreaks in clinical contexts. Despite these differences, the consistent finding across systems is that host genetic diversity creates a complex selective landscape that impedes specialized adaptation, often through trade-offs that limit parasite fitness across different host genotypes.

Molecular Mechanisms and Adaptive Responses

At the molecular level, parasites employ diverse strategies to adapt to host heterogeneity. In the K. pneumoniae hospital outbreak, strong positive selection acted on genes associated with capsule synthesis (wzc, wcoZ), lipopolysaccharide production (manB, manC), and iron utilization (sufB, sufC, fepA/fes intergenic region) [19]. The dN/dS ratio for genes with three or more independent mutations was 49.7, indicating intense positive selection [19]. These molecular adaptations represent responses to specific host environments and immune pressures.

In viral host shifts, mutations often occur in genes encoding host-binding proteins, such as tail fibres in bacteriophages or hemagglutinin in influenza viruses, enabling utilization of novel host receptors [17]. The number of mutations required for host adaptation, the size of the mutational target, and the presence of epistatic interactions collectively determine the likelihood of successful host shifting [17]. Parasites with higher mutation rates, such as RNA viruses, may have enhanced capacity to overcome the challenges posed by host heterogeneity.

Figure 2: Molecular Mechanisms of Parasite Adaptation to Host Heterogeneity. This diagram illustrates how diverse host characteristics select for different parasitic adaptation strategies, leading to specialized or constrained evolutionary outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Resources

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Representative Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| C. elegans wild genotypes | Model host with known genetic diversity | Experimental evolution studies with defined host heterogeneity [16] [15] |

| Mannitol Salt Agar (MSA) | Selective medium for S. aureus isolation | Pathogen extraction and passage in evolution experiments [16] |

| MHC-DRB genotyping assays | Assessment of immune gene diversity in vertebrates | Field studies of host-parasite coevolution in raccoons [18] |

| Half-sib quantitative genetic design | Partitioning genetic and environmental variance | Studying indirect genetic effects in aphid-parasitoid systems [14] |

| Viscous media (HPMC cellulose) | Mitigation of host behavioral avoidance | Ensuring standardized pathogen exposure in nematode studies [16] |

The experimental investigation of host heterogeneity effects requires specialized reagents and methodologies. Model host organisms with well-characterized genetic diversity, such as wild genotypes of C. elegans, provide the foundation for controlled studies of host-parasite coevolution [16] [15]. Selective media like Mannitol Salt Agar enable researchers to isolate and passage specific bacterial pathogens during experimental evolution studies [16].

For vertebrate systems, genotyping assays targeting immunologically relevant genes like MHC-DRB provide insights into how functional genetic variation influences parasite resistance [18]. Quantitative genetic designs, including half-sib breeding approaches, allow researchers to partition genetic and environmental variance, revealing indirect genetic effects across species boundaries [14]. Technical solutions like viscous media help standardize exposure by mitigating host behaviors such as pathogen avoidance, ensuring consistent selection pressures across experimental treatments [16].

The consistent finding across experimental systems—from laboratory models to natural populations—is that host heterogeneity acts as a significant evolutionary force constraining parasite virulence evolution. This conclusion has profound implications for disease management across multiple domains. In agricultural systems, it supports the value of crop diversification strategies for sustainable disease control. In conservation biology, it highlights the importance of maintaining genetic diversity in threatened populations to enhance resilience against emerging pathogens. In clinical settings, it suggests that understanding patient population heterogeneity may improve predictions of pathogen evolution during outbreaks.

Future research should focus on integrating molecular genomics with experimental evolution to identify the precise genetic changes underlying adaptation to homogeneous versus heterogeneous host populations. Additionally, more complex models incorporating multiple trophic levels, symbiont communities, and environmental variables will better reflect natural systems and enhance our ability to predict virulence trajectories in response to host heterogeneity. As technological advances continue to provide deeper insights into host-parasite interactions, the fundamental principle of host heterogeneity as an evolutionary constraint remains essential for understanding and managing infectious disease.

The evolutionary trade-offs between specialist and generalist strategies represent a core question in parasite ecology. Specialists, adapted to a narrow host range, are often hypothesized to achieve superior exploitation in their preferred hosts, while generalists sacrifice peak performance for the ability to infect a broader range of species. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these strategies by synthesizing recent empirical data and experimental findings. We objectively evaluate the performance of specialist and generalist parasites across key metrics—including prevalence, infection intensity, and virulence—to address the central theoretical conflict: the trade-off hypothesis, which posits that generalists pay a cost in reduced performance due to adaptations for multiple hosts, versus the niche breadth hypothesis, which argues that generalists achieve higher overall success through their wide host range and colonizing efficiency [20] [21]. Framed within a broader thesis on comparative analysis of parasite virulence, this guide serves researchers and drug development professionals by summarizing quantitative evidence, detailing experimental methodologies, and presenting a conceptual framework for understanding host-parasite dynamics.

Theoretical Frameworks: Trade-Off vs. Niche Breadth Hypotheses

The evolution of parasite virulence—defined as the reduction in host fitness due to infection—is fundamentally shaped by the parasite's host range [22]. The table below contrasts the two primary hypotheses governing the relationship between host range and parasite performance.

Table 1: Core Hypotheses on Host Specificity and Parasite Performance

| Hypothesis | Core Prediction | Proposed Mechanism | Expected Outcome for Generalists |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trade-Off Hypothesis [20] | Negative association between host range and performance per host. | Evolutionary costs of adapting to diverse host immune systems and physiologies reduce maximum exploitation efficiency. | Lower prevalence and infection intensity in any single host species. |

| Niche Breadth Hypothesis [20] [21] | Positive association between host range and performance. | Ability to infect more host species and efficiently colonize host communities leads to broader success. | Higher prevalence and infection intensity across host communities. |

These hypotheses offer testable predictions for empirical studies. The trade-off hypothesis suggests a constrained evolution of virulence for generalists, where their broad infectivity comes at the expense of optimized damage and transmission in any single host [22]. Conversely, the niche breadth hypothesis allows for generalists to be highly virulent and successful, as their ability to infect more hosts increases overall transmission opportunities and may select for increased within-host growth [20] [21].

Comparative Performance Data Across Parasite Systems

Empirical studies across diverse host-parasite systems provide data to test these competing hypotheses. The following tables synthesize quantitative findings from recent research.

Avian Blood Parasites

A large-scale study of avian malaria parasites (Plasmodium and Haemoproteus) in house sparrows directly tested the hypotheses, measuring prevalence (the proportion of infected hosts) and host specificity.

Table 2: Performance of Avian Malaria Parasites by Host Specificity [20] [21]

| Parasite Lineage Specificity | Number of Host Species | Prevalence in House Sparrows | Geographic Distribution (No. of Localities) | Supporting Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generalist Lineages | Higher | Higher | Higher (wider) | Niche Breadth Hypothesis: Positive association between host range and prevalence. |

| Specialist Lineages | Lower | Lower | Lower (more restricted) |

The study found a significant positive correlation between the number of host species a lineage could infect and its prevalence within house sparrow populations. Lineages found in more geographical localities also exhibited both higher prevalence and a broader host range [20] [21]. These results strongly support the niche breadth hypothesis in this system.

Bacterial Pathogens in Rodent Hosts

Research on bacterial pathogens in wild rodents reveals how infection dynamics are shaped by the interplay of host and parasite traits.

Table 3: Infection Dynamics of Bacterial Pathogens in Three Gerbil Species [12]

| Bacterial Pathogen | Host Species | Performance / Infection Dynamics | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bartonella krasnovii (Flea-borne, acute infection) | Gerbillus andersoni, G. pyramidum | High performance (longer duration, higher loads) | Supports Host Trait Variation: Both pathogens performed poorly in the same host, G. gerbillus. |

| Gerbillus gerbillus | Reduced performance (shorter duration, lower loads) | ||

| Mycoplasma haemomuris-like (Contact-transmitted, chronic infection) | Gerbillus andersoni, G. pyramidum | High performance | Supports Specific Interaction: All other aspects of dynamics (e.g., recurrence) were unique to each host-parasite pair. |

| Gerbillus gerbillus | Reduced performance |

This system demonstrates that while some aspects of infection (e.g., overall performance in G. gerbillus) align with the "host trait variation" hypothesis, the unique dynamics of each pathogen point to a "specific host-parasite interaction" hypothesis, where outcomes emerge from complex interplay rather than host traits alone [12].

Virulence and Within-Host Distribution

The trematode Ribeiroia ondatrae, which causes severe limb malformations in amphibians, demonstrates how within-host distribution is a key mechanistic driver of virulence. A study of 319 populations of Pacific chorus frogs (Pseudacris regilla) revealed that:

- Malformation risk was 2.7x greater in low-elevation ponds, even after controlling for total parasite infection load [23].

- This difference was linked to within-host parasite distribution: ~90% of parasites from low-elevation sites aggregated around the hind limbs (the site of malformations), compared to <60% from high-elevation sites [23].

- Reciprocal cross experiments showed that this difference was driven by parasite pathogenicity (a parasite contribution to virulence), not by host resistance or tolerance [23].

This case highlights that virulence is not just a function of parasite load, but also of the location of parasites within the host, a factor that can vary significantly among parasite populations.

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

To facilitate replication and critical evaluation, this section details the methodologies from pivotal studies cited in this guide.

Experimental Evolution of a Bacterial Pathogen in Novel Hosts

This protocol is adapted from a study investigating how host genotype and genetic diversity shape the evolution of Staphylococcus aureus virulence in a novel nematode host [16].

- Host Model: 24 wild genotypes of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, plus a lab-adapted strain (N2), were used. Hosts were maintained on Nematode Growth Medium (NGM) plates seeded with E. coli OP50 as food.

- Pathogen: The human pathogenic isolate Staphylococcus aureus MSSA476.

- Evolution Experiment Design:

- Treatments: Pathogens were passaged through (i) host monocultures (24 single-genotype populations) and (ii) host polycultures (a mix of all 24 genotypes).

- Passaging Cycle: For ten host generations, ~500 synchronized L4 stage nematodes were exposed to a concentrated S. aureus inoculum in a viscous media (TSB + HPMC cellulose) for 24 hours at 25°C. This media limited nematode avoidance behaviors.

- Pathogen Harvesting: After exposure, nematodes were washed and a subset was mechanically crushed with zirconia beads. The resulting solution was plated on Mannitol Salt Agar (MSA) to select for S. aureus. Approximately 100 colonies were picked to inoculate a culture for the next passage.

- Traits Measured: The evolved pathogen populations were assessed for changes in:

- Virulence: Pathogen-induced host mortality.

- Infectivity: Bacterial load within the host (infection load).

- Host Range: Performance of evolved pathogens on novel host genotypes.

This experimental design allowed researchers to directly test how selection in homogeneous versus diverse host populations drives the evolution of pathogen traits [16].

Field Survey and Reciprocal Cross-Experiments for Virulence Components

This protocol outlines the approach used to disentangle host and parasite contributions to virulence in the amphibian-trematode system [23].

- Field Survey Component:

- Scope: 319 populations of Pacific chorus frogs (Pseudacris regilla) across an elevation gradient in California were surveyed.

- Data Collected: For each population, researchers recorded the frequency of limb malformations and quantified infection load (number of Ribeiroia ondatrae metacercariae) via necropsy. The within-host distribution of cysts (e.g., aggregation around hind limbs) was also recorded.

- Reciprocal Cross Experiment:

- Factorial Design: Hosts (tadpoles) and parasites (R. ondatrae cercariae) from both high- and low-elevation sites were crossed in a full-factorial design with multiple levels of parasite exposure.

- Response Variables:

- Infection Success: To partition host resistance (host contribution) from parasite infectivity (parasite contribution).

- Host Pathology (Mortality & Growth): To differentiate host tolerance (host damage limitation per parasite) from parasite pathogenicity (parasite-induced damage per parasite).

- Within-Host Parasite Distribution: The location of encysted parasites within the host body.

This integrated methodology allowed researchers to attribute the observed differences in malformation risk to higher parasite pathogenicity and specific within-host aggregation in low-elevation trematode populations, rather than to differences in host defense [23].

Conceptual Framework and Visualizations

A Compartmental Model for Virulence Evolution in Opportunistic Pathogens

The following diagram illustrates a conceptual framework for understanding how selection in multiple environments shapes the evolution of virulence factors in opportunistic pathogens, which are typically generalists [24].

Diagram 1: Multi-Compartment Model of Virulence Evolution

This framework divides the microbe's world into two compartments [24]:

- The Asymptomatic Compartment (A): Environments where the microbe lives without causing disease (e.g., soil, host nasopharynx).

- The Virulence Compartment (V): Sensitive parts of a host where microbial Virulence Factors (VFs) cause disease.

The evolution of VF expression is driven by selective pressures across these compartments:

- Coincidental Selection: VFs are maintained because they provide a benefit in the Asymptomatic compartment (A), with their expression in the Virulence compartment (V) being a harmful byproduct [24].

- Colonization Selection: VF expression enhances the movement from A to V.

- Within-Host Selection: VFs directly enhance growth within the Virulence compartment (V).

- Export Selection: VF expression enhances shedding or transmission from V back to A or new hosts.

This model explains why generalist opportunistic pathogens may exhibit "maladaptive virulence" in a given host—their VFs are often maintained for reasons unrelated to causing disease in that particular host [24] [22].

Disentangling Host and Parasite Contributions to Virulence

The following diagram outlines the experimental and conceptual process for partitioning the components of virulence, as applied in the amphibian-trematode study [23].

Diagram 2: Framework for Partitioning Virulence Components

This workflow demonstrates how factorial experiments (crossing host and parasite genotypes/sources) and measurements of parasite load and host fitness allow researchers to attribute variation in virulence to specific host and parasite traits [23]. The final step often involves identifying the mechanism, such as the within-host distribution of parasites, which was a key driver in the trematode system.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs essential materials and reagents used in the experimental studies featured in this guide, providing a resource for designing related research.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Host-Parasite Evolution Studies

| Reagent / Material | Specification / Model | Primary Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Host Organisms | Caenorhabditis elegans (wild genotypes) [16]; House sparrows (Passer domesticus) [20]; Gerbil species (Gerbillus spp.) [12] | In vivo host: Provides a genetically tractable or natural host system for studying infection dynamics and evolution. | Experimental evolution of S. aureus [16]; Screening for avian malaria prevalence [20]. |

| Model Pathogens | Staphylococcus aureus MSSA476 [16]; Avian Plasmodium/Haemoproteus lineages [20]; Trematode Ribeiroia ondatrae [23] | Infectious agent: The parasite or pathogen whose evolutionary dynamics and virulence are under investigation. | Studying evolution of virulence and infectivity [16]; Testing host specificity hypotheses [20]. |

| Selective Culture Media | Mannitol Salt Agar (MSA) [16] | Pathogen isolation & selection: Selects for specific pathogens (e.g., S. aureus) from a mixed sample, such as a homogenized host. | Harvesting S. aureus from infected nematodes during experimental passaging [16]. |

| DNA Extraction Kit | QIAamp DNA Micro Kit (Qiagen) [25] | Nucleic acid purification: Extracts high-quality DNA from small samples (e.g., single lice, blood spots) for molecular analysis. | Preparing DNA from individual lice for microbiome and lineage identification [25]. |

| 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing | Primers 341F/805R for V3-V4 region; Illumina MiSeq [25] | Microbiome characterization: Profiles the bacterial community composition within a host or parasite sample. | Comparing microbiome structure between generalist and specialist louse lineages [25]. |

The evolutionary and ecological dynamics of host-parasite interactions are profoundly shaped by environmental conditions. Factors such as temperature, host density, and host life history act as critical modulators of parasite virulence, driving divergent evolutionary outcomes across different biological systems. This comparative guide synthesizes experimental data from recent research to objectively analyze how these environmental modulators influence parasite virulence evolution, host defense strategies, and infection outcomes. By integrating findings from diverse model systems—including nematodes, insects, rodents, and cervids—this analysis provides researchers and drug development professionals with a structured framework for understanding context-dependent virulence patterns and predicting disease dynamics in a changing world.

Comparative Data Analysis: Environmental Effects on Virulence

Table 1: Temperature Effects on Host-Pathogen Interactions Across Model Systems

| Host System | Pathogen | Temperature Regime | Key Findings on Virulence/Resistance | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caenorhabditis elegans (nematode) | Leucobacter musarum (bacterium) | Prolonged warming (25°C) vs. ambient (20°C) | Warming during development induced plastic defenses; prolonged warming selected for genetic resistance | Host mortality and fecundity assays; evolutionary passages [26] |

| Drosophilidae (45 species) | Drosophila C Virus (DCV) | Low (17°C), Medium (22°C), High (27°C) | Variance in viral load increased with temperature; most susceptible species became more susceptible | Viral load quantification across species and temperatures [27] |

| Anopheles gambiae (mosquito) | Vavraia culicis (microsporidian) | 4°C vs. 20°C (environmental persistence) | Virulent parasite lines had reduced environmental survival at both temperatures | Infectivity and infection severity assays after environmental storage [10] |

Table 2: Host Density and Life History Effects on Parasite Virulence and Transmission

| Host-Parasite System | Modulator Type | Experimental Manipulation | Impact on Virulence/Transmission | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moose-White-tailed deer | Host density & Shared parasites | Natural experiment with parasite load quantification | Moose occupancy limited by parasite-mediated competition, not direct competition | [28] |

| Paramecium caudatum-Holospora undulata | Host life span | Serial transfer with early (11d) vs. late (14d) host killing | Early-killing parasites evolved shorter latency and higher virulence | [29] |

| Gerbil species-Bartonella/Mycoplasma | Host species heterogeneity | Cross-inoculation of three rodent species with two bacteria | Infection dynamics varied by specific host-parasite combination, not just host traits | [12] |

| Rodent-Heligmosomoides polygyrus/Plasmodium yoelii | Co-infection timing | Sequential infections with varying order | Previous nematode infection increased malaria severity; order critical to outcome | [30] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Temperature Manipulation in Nematode-Bacteria Systems

The experimental protocol for assessing temperature effects on host-pathogen evolution in the C. elegans-L. musarum system involves several key stages. Researchers maintained nematode populations under controlled temperature regimes (ambient: 20°C; warming: 25°C) with timing varied during development (L1 larvae to L4 young adults) and adult pathogen exposure stages [26].

Infection Assay Protocol:

- Synchronize L1 larval populations of susceptible (N2) and resistant (srf-2) genotypes

- Culture larvae on E. coli OP50 food source at designated temperatures (20°C or 25°C) for 36-48 hours until reaching L4 stage

- Wash L4 young adults and transfer approximately 300-400 worms to infection or control plates

- Expose to L. musarum pathogen for 24 hours at experimental temperatures

- Assess host mortality by counting live/dead nematodes; confirm death by lack of response to platinum wire touch

- Evaluate population fecundity by washing worms and eggs off plates, collecting unhatched sterile eggs via bleaching

- Count total and resistant L1 larvae after 12-hour incubation in M9 buffer using fluorescent microscopy

For evolutionary experiments, researchers competed resistant and susceptible genotypes across 10 serial passages, tracking resistance frequency in populations under different temperature regimes [26].

Host Density and Parasite-Mediated Competition Assessment

The protocol for evaluating parasite-mediated competition in cervid systems employs hierarchical abundance-mediated interaction models to quantify the relative importance of direct competition versus indirect parasite effects [28].

Field Sampling and Analysis Protocol:

- Collect detection/non-detection data for moose and white-tailed deer across heterogeneous landscapes

- Obtain fecal samples for parasite load quantification (Parelaphostrongylus tenuis, Fascioloides magna)

- Analyze data using hierarchical models that account for imperfect detection

- Test competing hypotheses regarding moose occupancy limitations:

- Direct competition with deer (measured via deer abundance index)

- Indirect effects via parasite-mediated competition (measured via local parasite intensities)

- Habitat factors (biotic and abiotic landscape effects)

- Parameterize models with field data to determine relative support for each mechanism

This approach demonstrated that moose occupancy was limited by parasite-mediated competition rather than direct competitive interactions with deer, with no evidence of population-level effects from direct competition [28].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Temperature-Induced Plastic Defense Pathways

The molecular basis for temperature-induced plastic defenses in C. elegans involves heat shock response pathways that confer multipathogen resistance. Warming during host development activates heat shock transcription factors (HSF-1) that trigger production of heat shock proteins and other chaperones, enhancing protein homeostasis and cellular stress resistance [26]. This preemptive activation of stress response pathways provides broad-spectrum protection against subsequent bacterial infection, reducing the selective pressure for costly genetic-based resistance mechanisms.

Coinfection-Induced Immunomodulation Pathways

In sequential parasite infections, the order of exposure triggers distinct immune modulation pathways that significantly alter disease outcomes. Research on Heligmosomoides polygyrus (intestinal nematode) and Plasmodium yoelii (malaria parasite) coinfection revealed that prior nematode infection induces immunosuppressive pathways that exacerbate subsequent malaria severity [30].

The mechanistic basis involves increased proportions of regulatory T cells (Tregs) expressing the CTLA-4 immune checkpoint and exhausted CD8+ T cells expressing PD-1 and LAG-3 markers, impairing anti-malarial immunity and reducing tolerance to infection-induced anemia [30].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Environmental Modulation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Research Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Host Organisms | Caenorhabditis elegans (N2, srf-2); Drosophilidae (45 species); Gerbil species (G. andersoni, G. pyramidum, G. gerbillus) | Comparative virulence assays | Testing temperature effects on resistance evolution [26] [27] |

| Pathogen Stocks | Leucobacter musarum; Drosophila C Virus (DCV); Bartonella krasnovii A2; Mycoplasma haemomuris-like | Controlled infection studies | Host shift potential across temperatures [27] |

| Temperature Control Systems | Precision incubators (17°C, 20°C, 22°C, 25°C, 27°C) | Thermal regime manipulation | Testing plastic defenses vs. genetic adaptation [26] |

| Molecular Detection Tools | 18S rRNA primers (1391f, EukBr); Antibiotic-antimycotic cocktails; Phase-contrast microscopy | Parasite load quantification | Eukaryotic community analysis in fecal samples [31] |

| Cell Culture Lines | Ect1/E6E7 (human ectocervical); Schneider's Drosophila line 2 | In vitro infection models | Host-bacteria-parasite interaction studies [32] |

The experimental data compiled in this analysis demonstrate that environmental modulators exert predictable yet system-dependent effects on parasite virulence evolution and host defense strategies. Temperature shifts alter selection pressures on both host and pathogen, host density facilitates parasite-mediated competition that can override direct competitive interactions, and host life history traits determine the optimal balance between plastic and genetic defense mechanisms. For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings highlight the critical importance of environmental context in predicting virulence evolution and designing effective intervention strategies. The experimental protocols and reagent toolkit provided herein offer a foundation for systematic investigation of these dynamics across diverse host-parasite systems, ultimately supporting the development of environment-informed disease management approaches.

Advanced Methodologies: From Experimental Evolution to Omics Technologies

Parasite-host interactions represent a fundamental driver of evolutionary change, leading to highly dynamic co-evolutionary arms races characterized by repeated cycles of host counter-adaptations and parasite offenses [33] [34]. The investigation of these complex relationships requires robust experimental model systems that permit controlled manipulation and detailed observation. Two such systems—the Caenorhabditis elegans-Serratia marcescens and mosquito-microsporidian models—have emerged as powerful platforms for studying the evolutionary dynamics of parasite virulence and host resistance. These systems provide complementary advantages: the C. elegans-Serratia model offers unparalleled genetic tractability and molecular tools [33] [35], while mosquito-microsporidian systems deliver ecological relevance and insights into vector-borne disease control [36] [37]. This comparative analysis examines the experimental applications, quantitative outcomes, and methodological approaches of these two systems, providing researchers with a structured framework for selecting appropriate models for investigating parasite virulence across host species.

The C. elegans-S. marcescens system centers on a soil-dwelling nematode and a gram-negative bacterial pathogen with broad host range, including humans [35]. S. marcescens infects C. elegans through intestinal colonization, disrupting pharyngeal function and leading to lethal infection [35]. This system benefits from the nematode's short generation time, genetic tractability, and transparency, allowing direct observation of infection processes [33] [35].

The mosquito-microsporidian system involves various mosquito species (particularly Aedes aegypti and Anopheles gambiae) and microsporidian parasites such as Vavraia culicis [36] [37]. Microsporidia are obligate intracellular eukaryotic parasites that infect mosquito larvae through spore ingestion, primarily colonizing adipose tissue and digestive system epithelium [38] [37]. This system offers ecological relevance for disease vector control and opportunities to study complex host-parasite interactions in an epidemiologically significant context.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Experimental Evolution Systems

| Characteristic | C. elegans-S. marcescens System | Mosquito-Microsporidian System |

|---|---|---|

| Host Organism | Caenorhabditis elegans (nematode) | Aedes aegypti, Anopheles gambiae (mosquitoes) |

| Parasite Type | Gram-negative bacterium (Serratia marcescens) | Microsporidian eukaryotes (e.g., Vavraia culicis) |

| Infection Route | Intestinal colonization via ingestion [35] | Spore ingestion, intracellular infection [37] |

| Primary Tissues Affected | Intestinal lumen, epithelial cells [35] | Gut epithelium, fat body, multiple tissues [38] [37] |

| Key Experimental Advantages | Genetic tractability, transparency, short life cycle [33] [35] | Ecological relevance, vector control applications, tissue tropism studies [36] [37] |

Quantitative Virulence and Resistance Profiles

Genetic Variation and Specific Interactions in C. elegans-S. marcescens

Comprehensive analyses of natural C. elegans isolates infected with diverse S. marcescens strains reveal significant variation in host susceptibility and pathogen virulence [33] [34]. In survival assays comparing eight C. elegans strains with five S. marcescens strains, nematode strains MY6 and MY18 demonstrated highest resistance, while MY14 and MY15 showed greatest susceptibility [33] [34]. Bacterial strain Sm2170 exhibited highest virulence, whereas strains Sma3 and Sma13 produced minimal mortality and morbidity [33] [34]. Statistical analyses confirmed significant strain- and genotype-specific interactions between hosts and parasites, fulfilling key prerequisites for frequency-dependent selection dynamics in co-evolutionary arms races [33] [34].

Host-Specific Effects in Mosquito-Microsporidian Systems

Infection dynamics and virulence expression differ markedly between mosquito species infected with V. culicis [37]. Aedes aegypti experiences more pronounced effects during aquatic stages but can clear infections as adults, while Anopheles gambiae shows inability to clear infections and exhibits sexual dimorphism in parasite loads [37]. Larval mortality increases significantly upon exposure to V. culicis—by a factor of 3.7 in Ae. aegypti and 2.3 in An. gambiae [37]. Parasite infection also induces developmental delays, with exposed mosquitoes pupating approximately half a day later than unexposed counterparts [37].

Table 2: Quantitative Virulence Metrics Across Host-Parasite Systems

| Parameter | C. elegans-S. marcescens System | Aedes aegypti-V. culicis | Anopheles gambiae-V. culicis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Host Mortality | Strain-dependent; up to complete mortality with virulent strains [33] [34] | Larval mortality increased 3.7x; pupal mortality unaffected [37] | Larval mortality increased 2.3x; pupal mortality unaffected [37] |

| Development Impact | Not explicitly measured | 0.5-day pupation delay [37] | 0.5-day pupation delay [37] |

| Infection Persistence | Progressive, lethal infection [35] | Adults can clear infection [37] | Persistent infection through lifespan [37] |

| Sexual Dimorphism | Not reported | Minimal differences in spore density [37] | Males have higher average parasite load [37] |

| Spore Density/Bacterial Load | Exponential growth in intestinal lumen [35] | Plateaus at 10^4-10^5 spores/mosquito [37] | Plateaus at 10^4-10^5 spores/mosquito [37] |

Experimental Methodologies and Workflows

Standardized Infection Protocols

C. elegans-S. marcescens Survival Assays: Experiments are typically performed in 96-well plates with synchronized L4 larval-stage worms transferred to lawns of S. marcescens grown under standardized conditions [33] [34]. Survival is monitored through automated or manual scoring of worms categorized as "alive," "morbid," or "dead" [33] [34]. Control groups receive heat-killed bacteria to account for background mortality. For virulence factor screening, transposon-induced mutant banks of S. marcescens are tested against nematode populations, with attenuated clones further validated in insect and murine models [35].

Mosquito-Microsporidian Infection Protocols: Mosquito larvae are individually reared in multi-well plates containing deionized water [37]. Two-day-old larvae are exposed to microsporidian spores during a synchronized 24-hour infection window [37]. Mortality assessments occur every 24 hours through larval and pupal stages. Upon adult emergence, infection intensity is quantified by spore counting using hemocytometers, with sampling conducted at regular intervals throughout the mosquito lifespan [37].

High-Throughput Phenotyping Approaches

Recent advances in both systems have introduced multiplexed competitive fitness assays that enable efficient screening of multiple host genotypes under selective pressure. The PhenoMIP (Phenotyping using Molecular Inversion Probes) approach allows pooled cultivation of up to 22 C. elegans wild isolates infected with multiple microsporidia species, with strain-specific fitness determined through unique genomic signatures [39]. This methodology has identified strains with opposing resistance and susceptibility traits to different microsporidia species, demonstrating species-specific genetic interactions [39].

Host Defense Mechanisms and Immune Responses

C. elegans Antibacterial Defense Pathways

C. elegans mounts inducible antibacterial defenses against S. marcescens infection characterized by upregulated expression of genes encoding lectins and lysozymes [40]. Microarray analyses demonstrate that these infection-inducible genes are partially regulated by the DBL-1/TGFβ pathway, with dbl-1 mutants exhibiting increased susceptibility to infection [40]. Conversely, overexpression of lysozyme gene lys-1 enhances resistance to S. marcescens, confirming the functional importance of these immune effectors [40].

Against microsporidian parasites, C. elegans activates the Intracellular Pathogen Response (IPR)—a transcriptional program characterized by upregulation of specific genes that promote resistance against diverse intracellular pathogens [41] [39]. The IPR represents a novel innate immune/stress response distinct from classical immune pathways, and mutations in negative regulators of this pathway confer elevated microsporidia resistance [41] [39].

Mosquito Immune Responses and Microbiome Modulation

Microsporidian infection in mosquitoes alters the composition and functional capacity of the host-associated microbiome, shifting bacterial communities toward taxa including Aerococcaceae, Lactobacillaceae, and Microbacteriaceae [38]. Functional prediction analyses reveal enrichment in biosynthetic pathways for ansamycin and vancomycin antibiotic groups in infected larvae, suggesting microbiome-mediated enhancement of antimicrobial capabilities [38]. These modifications demonstrate the complex tripartite interactions between host, parasite, and microbiota in determining infection outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Resources

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Host Strains | Genetic diversity studies; resistance/susceptibility mapping | C. elegans: MY6 (resistant), MY14/MY15 (susceptible) [33] [34]; C. elegans JU1400 (opposing phenotypes) [39]; Mosquitoes: Aedes aegypti, Anopheles gambiae [37] |

| Pathogen Strains | Virulence studies; host range analysis | S. marcescens: Db11, Sm2170 (high virulence), Sma3/Sma13 (low virulence) [33] [35] [34]; Microsporidia: Vavraia culicis, Nematocida species [41] [37] |

| Molecular Tools | Genetic manipulation; pathway analysis | Transposon mutant banks (S. marcescens) [35]; RNAi libraries (C. elegans); GFP-tagged pathogens (infection visualization) [35] |

| Assay Systems | High-throughput screening; fitness measurements | PhenoMIP/MIP-seq (multiplexed competition assays) [39]; Survival assays in 96-well plates [33] [34]; Individual larval rearing systems [37] |

| Imaging & Analysis | Infection progression; spore quantification | Fluorescence microscopy (GFP-tagged pathogens) [35]; Hemocytometers (spore counting) [37]; Automated worm transfer systems [33] |

The C. elegans-S. marcescens and mosquito-microsporidian experimental systems provide complementary approaches for investigating the evolutionary dynamics of parasite-host interactions. The C. elegans system offers unparalleled genetic tractability and high-throughput screening capabilities, enabling detailed molecular dissection of host defense pathways and virulence mechanisms [33] [35] [39]. In contrast, mosquito-microsporidian systems deliver ecological relevance and direct applications to vector-borne disease control, with the additional complexity of microbiome modulation influencing infection outcomes [38] [37]. Both systems demonstrate substantial genetic variation in host susceptibility and parasite virulence, with genotype-specific interactions driving co-evolutionary arms races [33] [34] [37]. The continued development of sophisticated phenotyping methods like PhenoMIP ensures these model systems will remain at the forefront of evolutionary parasitology research, providing insights into conserved mechanisms of innate immunity and pathogen evasion strategies [39].

This guide provides an objective comparison of key molecular diagnostics—Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), targeted Next-Generation Sequencing (tNGS), and metagenomic NGS (mNGS)—within parasite research, focusing on their performance in detecting and characterizing parasitic virulence across host species.

The comparative analysis of parasite virulence hinges on precise diagnostic tools. While traditional microscopy remains a cornerstone, molecular techniques offer superior sensitivity and specificity for identifying fastidious, rare, or co-infecting parasites. These tools are crucial for understanding host-parasite dynamics, genetic diversity, and the mechanisms underlying antiparasitic drug resistance [42]. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies, in particular, are transforming parasitology laboratories into smart platforms, enabling high-resolution insights into parasitic populations without prior culturing [42] [43].

Technical Performance Comparison

The selection of a molecular method involves trade-offs between detection breadth, sensitivity, speed, and cost. The table below summarizes the comparative performance of PCR, mNGS, and tNGS based on recent experimental studies.

Table 1: Comparative Diagnostic Performance of PCR, mNGS, and tNGS

| Feature | Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) | Metagenomic NGS (mNGS) | Targeted NGS (tNGS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Amplification of specific, known DNA sequences | Unbiased sequencing of all nucleic acids in a sample [44] | Enrichment and sequencing of predefined pathogen targets [45] [44] |

| Pathogen Detection Scope | Narrow; limited to pre-specified targets [46] | Broad; capable of detecting bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites simultaneously [42] [44] | Intermediate; focused on a panel of pre-selected pathogens [45] |

| Sensitivity | High for targeted organisms; can miss novel/unknown pathogens [47] [46] | High; can detect low-abundance and unexpected pathogens [42] [48] | High for targeted pathogens; comparable or superior to mNGS for some infections [45] [49] |

| Specificity | High, if primers are well-designed [47] | Variable; requires careful bioinformatics to manage contamination [48] [50] | Very high, due to targeted enrichment [45] [49] |

| Quantitative Capability | Yes (via qPCR) | Semi-quantitative | Semi-quantitative |

| Turnaround Time | Short (hours) [47] | Long (20-48 hours) [45] [50] | Moderate; shorter than mNGS [45] |

| Cost | Low | High (e.g., ~$840/sample) [45] | Moderate; lower than mNGS [45] |

| Ideal Use Case | Routine detection of specific, known parasites [47] | Hypothesis-free detection of rare, novel, or mixed infections [45] [42] | Routine syndromic testing with comprehensive pathogen panels [45] |

Experimental Data and Protocols

Key Experimental Findings in Parasitology