High-Throughput Parasite Screening: Advanced Methodologies for Drug Discovery and Diagnostic Innovation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern high-throughput screening (HTS) methodologies transforming parasite research and drug development.

High-Throughput Parasite Screening: Advanced Methodologies for Drug Discovery and Diagnostic Innovation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern high-throughput screening (HTS) methodologies transforming parasite research and drug development. It explores foundational principles of HTS automation and miniaturization, details specific applications across major human parasites including Plasmodium, Trichomonas, and helminths, and offers practical troubleshooting guidance for assay optimization. Through comparative analysis of molecular, phenotypic, and image-based approaches, we validate screening platforms that enable rapid antimalarial resistance profiling, natural product discovery, and anthelmintic testing. This resource equips researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to implement robust, scalable screening strategies that accelerate therapeutic innovation and improve diagnostic capabilities in parasitology.

The Foundations of High-Throughput Parasite Screening: Principles, Technologies, and Market Landscape

Defining High-Throughput Screening (HTS) and Ultra-HTS in Parasitology

Core Definitions and Quantitative Benchmarks

What is the fundamental difference between HTS and uHTS in a parasitology screening context?

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) is an automated method for scientific discovery, crucially used in drug discovery, that allows a researcher to rapidly conduct millions of chemical, genetic, or pharmacological tests [1]. Using robotics, data processing software, liquid handling devices, and sensitive detectors, HTS facilitates the identification of active compounds, antibodies, or genes that modulate a particular biomolecular pathway [1]. In parasitology, this technique is applied to identify compounds active against parasitic targets [2] [3].

Ultra-High-Throughput Screening (uHTS) is an evolution of HTS, representing an automated methodology for conducting hundreds of thousands of biological or chemical screening tests per day [4]. The distinction is somewhat arbitrary but is generally defined by a throughput in excess of 100,000 compounds per day [1] [4]. uHTS has become accessible to smaller research companies and academic groups as instrumentation costs have decreased [4].

Table 1: Key Quantitative Benchmarks for HTS and uHTS

| Parameter | Traditional HTS | uHTS |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput (compounds per day) | Tens of thousands to 100,000 [1] [4] | In excess of 100,000; systems exist for over 1,000,000 [1] [4] |

| Common Microplate Formats | 96, 384, 1536-well plates [1] | 1536, 3456, 6144-well plates; chip-based and droplet microfluidics [1] [4] |

| Assay Volume | Microliters (μL) to nanoliters (nL) in microplates [1] | Nanoliters (nL); picoliter (pL) volumes in droplet-based microfluidics [1] |

| Primary Screening Goal | Identify "hits" - compounds with a desired size of effects [1] | Rapidly process immense compound libraries to identify initial hits [5] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: A Multiplexed Glycolysis Screen inTrypanosoma brucei

The following protocol is adapted from a recent (2024) open-access study that developed a high-throughput flow cytometry screening assay to identify glycolytic probes in bloodstream form Trypanosoma brucei, a kinetoplastid parasite [6].

1. Assay Principle: This method uses live parasites transfected with biosensors to simultaneously measure multiple glycolysis-relevant metabolites. It multiplexes biosensors for glucose (a FRET biosensor), ATP (a FRET biosensor), and glycosomal pH (a GFP-based biosensor), alongside a viability dye (thiazole red), in a single flow cytometry run [6].

2. Key Materials and Reagents:

- Cell Line: Bloodstream form Trypanosoma brucei parasites.

- Biosensors: Transfected cell lines expressing the FRET-based glucose and ATP sensors, and the GFP-based pH sensor.

- Compound Library: For example, the Life Chemicals Compound Library or other relevant chemical collections.

- Assay Plates: 384-well or 1536-well microplates.

- Instrumentation: A flow cytometer capable of high-throughput sampling from microplates.

3. Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Cell Preparation: Pool the sensor cell lines. The pH sensor has a different fluorescent profile from the FRET sensors, allowing simultaneous measurement of pH with either glucose or ATP [6].

- Plate Loading: Dispense the pooled sensor cell lines into the assay plates, which have been pre-loaded with the compound library. The library is analyzed twice: once with the pooled pH and glucose sensor cell lines, and once with the pooled pH and ATP sensor cell lines [6].

- Incubation: Incubate the plates to allow compound-parasite interaction.

- High-Throughput Flow Cytometry: Analyze the plates using the flow cytometer. The cytometer measures the fluorescence signals from all biosensors and the viability dye for each well simultaneously [6].

- Data Analysis: Process the data to determine the impact of each compound on the measured parameters (glucose, ATP, pH, and viability). Calculate Z'-factor values to confirm assay quality. Hit rates from the pilot screen of 14,976 compounds were between 0.2% and 0.4% [6].

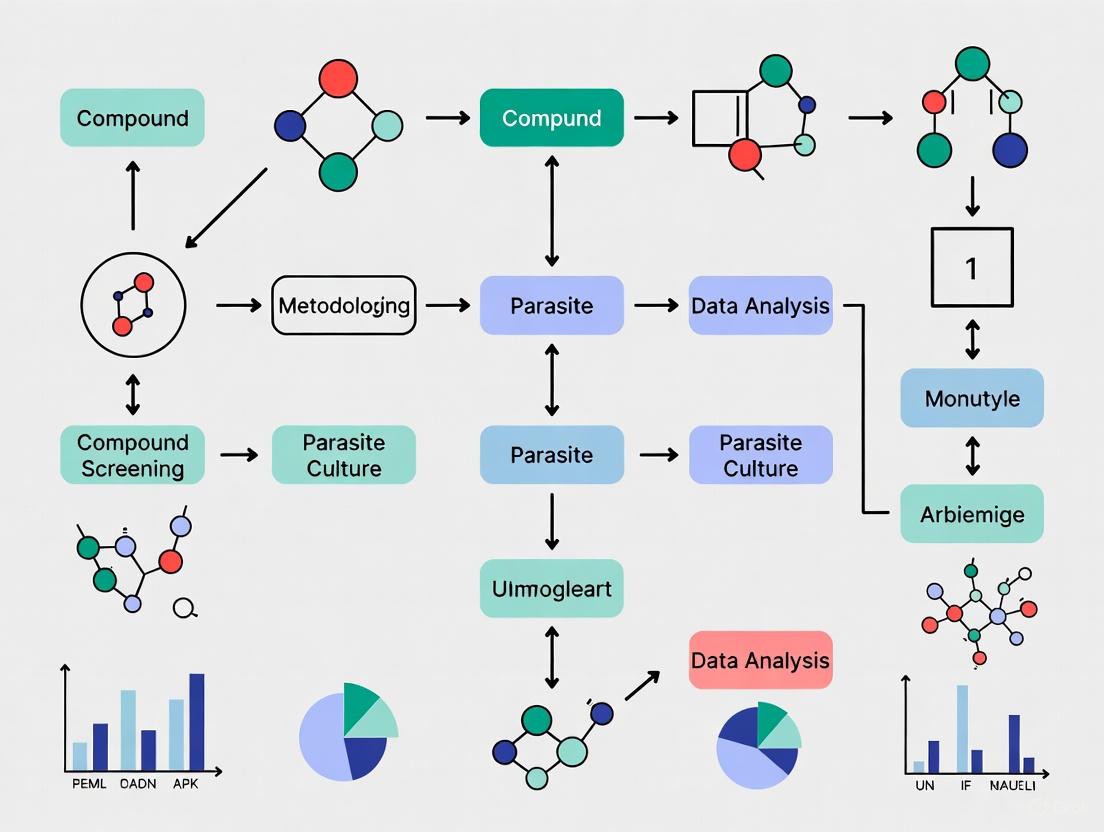

Diagram 1: Workflow for a multiplexed glycolysis screen.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: Our HTS campaign in Plasmodium is generating an unacceptably high number of false positives. What are the primary quality control measures we can implement? A high false-positive rate often indicates underlying assay quality issues. Implement these QC steps:

- Effective Plate Design: Incorporate both positive controls (a known inhibitor) and negative controls (DMSO-only) randomly across the plate to identify and correct for systematic errors, such as edge effects [1].

- Calculate a QC Metric: Use the Z'-factor to evaluate the assay's quality and its suitability for HTS. An assay with a Z'-factor >= 0.5 is considered excellent for screening [6]. The Z'-factor assesses the separation between the positive and negative control signals, factoring in their variations [1].

- Use Robust Hit Selection Methods: For primary screens without replicates, avoid simple metrics like percent inhibition that don't capture data variability. Instead, use robust statistical methods like the z-score or SSMD which are less sensitive to outliers [1].

FAQ 2: We have identified "hits" from our primary uHTS against Leishmania. What is the critical next step to confirm biological relevance? Primary hits must be advanced to secondary screening [5]. This involves:

- Hit Confirmation: Re-test the selected hits in a dose-response manner to confirm activity and eliminate false positives resulting from assay interference.

- Determine Specificity: Test confirmed hits for cytotoxicity against mammalian cell lines to assess selectivity for the parasite.

- Understand Mechanism: Begin to investigate the compound's mechanism of action and specificity, which may involve additional, more complex phenotypic assays [2] [5].

FAQ 3: Our assay uses a 384-well format, but we are considering moving to 1536-wells to increase throughput. What are the key technical challenges? Miniaturization to 1536-well plates and beyond introduces specific challenges:

- Liquid Handling: Requires highly accurate and precise nanoliter-volume liquid handlers to avoid volumetric errors that can cripple assay performance.

- Evaporation: Smaller volumes are more susceptible to evaporation, particularly in edge wells, which can create significant well-to-well variation. Using sealed plates or controlled humidity environments is critical.

- Assay Signal Strength: With less biological material and fewer cells per well, the signal intensity decreases. This requires highly sensitive detection systems, such as confocal imaging or advanced luminescence readers, to maintain a robust signal-to-noise ratio [4] [7].

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting a high false-positive rate.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for HTS in Parasitology

| Item | Function in HTS/uHTS | Example in Parasitology |

|---|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates | The key labware for HTS; disposable plastic plates with a grid of wells to hold assays and compounds. | Used in various formats (96 to 1536 wells) to host parasite cultures, recombinant parasitic enzymes, or cell-free systems for screening [1]. |

| Compound Libraries | Diverse collections of small molecules, natural product extracts, or oligonucleotides used to find initial "hits." | Unbiased compound collections screened against whole parasites (phenotypic) or specific parasitic targets (target-based) [2] [3]. |

| Biosensors | Genetically encoded or chemical tools that report on a specific metabolic or ionic state in live cells. | FRET-based biosensors for glucose or ATP, and GFP-based biosensors for organellar pH in T. brucei [6]. |

| Fluorescence & Luminescence Detection Kits | Enable highly sensitive, automation-compatible detection of biological activity. | Fluorescence polarization (FP), FRET, and luminescence assays are common. Thiazole red used as a viability dye in flow cytometry [7] [6] [8]. |

| Automated Liquid Handlers | Robotics for accurate and precise transfer of nanoliter to microliter volumes for assay plate preparation. | Critical for creating assay plates from stock compound plates and for adding reagents/parasites during uHTS campaigns [1] [4]. |

| Antibacterial agent 176 | Antibacterial agent 176, MF:C21H23ClN4O2, MW:398.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Hsd17B13-IN-80 | Hsd17B13-IN-80, MF:C25H18Cl2F3N3O3, MW:536.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Within high-throughput screening (HTS) for parasite research, automation and miniaturization are critical for efficiently testing thousands of compounds. This technical support center addresses common operational challenges in these workflows, providing targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers maintain data integrity and experimental efficiency in critical research, such as the search for new anthelmintics [9].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. My automated liquid handler is dripping from the tips, contaminating the deck. What could be wrong? Dripping tips are often caused by a mismatch between the vapor pressure of your sample and the water used for system adjustment, or by the viscous nature of certain reagents [10] [11]. Solutions include sufficiently pre-wetting tips, adding an air gap after aspiration, or adjusting the aspirate and dispense speeds to account for the liquid's characteristics [11].

2. Our high-throughput screening of a 30,000-compound library is showing an unexpected rate of false negatives. What could be the source of this error? In the context of parasite screening, false negatives can be severely detrimental as active compounds may be overlooked [10]. A potential cause is the under-delivery of critical reagents by the liquid handler, which leads to lower-than-intended reagent concentrations in assay wells [10]. It is crucial to regularly verify the accuracy and precision of volume transfers through calibration and quantitative verification checks [10].

3. When performing serial dilutions for dose-response assays, the observed EC50 values are inconsistent. Where should I look? A common source of error in serial dilution protocols is insufficient mixing [10]. If the reagents in the wells are not homogenized before transfer, the concentration of critical reagents will differ from the theoretical concentration, leading to flawed results [10]. Ensure your method includes adequate mixing steps, such as multiple aspirate/dispense cycles, and validate that volumes are consistent across all dilution steps [10].

4. The robot arm is not moving to its taught positions correctly. What are the first things to check? First, check the teach pendant for any fault or alarm codes [12] [13]. Confirm that all safety mechanisms, such as gate sensors, have not been triggered [13]. A simple system restart can sometimes clear errors. If problems persist, check for mechanical issues like worn cables or calibrate the robot's motion and axis systems [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Liquid Handling Inaccuracies

Liquid handling errors can compromise screening data. Follow this logical pathway to diagnose common issues.

Common Liquid Handling Errors and Solutions The table below summarizes specific errors, their possible sources, and proven solutions [11].

| Observed Error | Possible Source of Error | Possible Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Dripping tip or hanging drop | Difference in vapor pressure of sample vs. adjustment water [11] | Sufficiently pre-wet tips; Add an air gap after aspiration [11] |

| Droplets or trailing liquid during delivery | Viscosity and other liquid characteristics [11] | Adjust aspirate/dispense speed; Add air gaps/blow outs [11] |

| First/last dispense volume difference in sequential dispensing | Inherent to sequential dispense method [10] [11] | Dispense first/last quantity into reservoir/waste [11] |

| Serial dilution volumes varying from expected concentration | Insufficient mixing in the wells [10] | Measure and improve liquid mixing efficiency [11] |

| Incomplete aspiration or dispensing | Loose tip fit or worn equipment [15] | Press tip firmly for a 'click'; use correct pipette size; schedule calibration [15] |

Guide 2: General Robotic System Failure

When an industrial robot or automated system stops working, a systematic approach is key to minimizing downtime [13].

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Protocol: Validating Liquid Handler Performance for Critical Reagents

Purpose: To ensure automated liquid handlers dispense accurate and precise volumes of critical reagents, thereby protecting the integrity of HTS data and controlling costs associated with rare compounds [10].

Background: Inaccurate liquid handling can have severe economic consequences. For example, a 20% over-dispensing of a reagent costing $0.10 per well can lead to hundreds of thousands of dollars in additional annual costs in a large screening laboratory. More critically, under-dispensing can cause false negatives, potentially causing a promising therapeutic compound to be overlooked [10].

Methodology:

- Selection of Verification Method: Use a standardized, quantitative platform (e.g., gravimetric, photometric, or fluorometric) suitable for the volumes being tested [10].

- Assay Setup: Program the liquid handler to dispense the target volume(s) into a suitable microplate. Include a comparison of different tip types (vendor-approved vs. generic) if this is a variable [10].

- Execution: Run the verification protocol multiple times (e.g.,

n=50cycles) to observe repeatability and identify surface-level errors [12]. - Data Analysis: Calculate the accuracy (% deviation from target volume) and precision (% coefficient of variation) for each dispensing channel.

- Acceptance Criteria: Define and apply action limits based on the requirements of your specific assay. Systems failing these limits should be calibrated, serviced, or have their methods re-optimized [10].

Data Presentation: Economic Impact of Volume Transfer Error The following table models the potential financial impact of liquid handling inaccuracies in a large-scale screening environment, based on data from [10].

| Screening Parameter | Baseline Scenario | With 20% Over-Dispensing | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wells per screen | 1.5 million | 1.5 million | - |

| Screenings per year | 25 | 25 | - |

| Cost per well | $0.10 | $0.12 | +$0.02 |

| Annual reagent cost | $3.75 million | $4.5 million | +$750,000 |

Protocol: Automated Parasite Detection with the Orienter Model FA280

Purpose: To provide a high-throughput, automated alternative to the manual formalin-ethyl acetate concentration technique (FECT) for detecting parasite ova in stool samples [16].

Workflow Overview:

Key Considerations:

- Throughput: The FA280 processes batches of 40 samples in approximately 30 minutes [16].

- Agreement with FECT: The FA280 with user audit showed perfect agreement (κ = 1.00) with FECT for species identification of protozoa and strong agreement for helminths (κ = 0.857) in one study [16].

- Limitations: The FA280 may have lower sensitivity than FECT, potentially due to the smaller stool sample size (0.5 g vs. 2 g). Cost per test may also be higher [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Vendor-Approved Pipette Tips | Accurate aspiration and dispensing of liquids [10]. | Cheap bulk tips may have variable properties (wettability, flash) causing delivery errors [10]. |

| Air Displacement Liquid Handler | Versatile pipetting for aqueous reagents [11]. | Prone to errors from pressure changes or leaks; ensure tight seals [11]. |

| Positive Displacement Liquid Handler | Pipetting viscous, foaming, or volatile liquids [11]. | Requires checking for bubbles, kinks, and leaks in tubing; liquid temperature affects flow rate [11]. |

| FRET-based Biosensors | Multiplexed measurement of metabolites (e.g., glucose, ATP) in live parasites during HTS [6]. | Enables simultaneous analysis of multiple pathways; Z'-factor should be acceptable for HTS [6]. |

| Formalin-Ethyl Acetate | Sedimentation and concentration of parasites in stool for FECT, the traditional gold standard [16]. | Uses a larger sample size (2 g), potentially increasing sensitivity compared to some automated methods [16]. |

| Microplates (96-well) | Standard platform for HTS assays [10]. | Proper deck layout definition in software is critical to avoid errors [10]. |

| Ret-IN-26 | Ret-IN-26, MF:C23H27N5O2, MW:405.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (Trp4)-Kemptide | (Trp4)-Kemptide, MF:C40H66N14O9, MW:887.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

This technical support center addresses the key technological considerations for implementing and troubleshooting microplate-based assays within high-throughput screening (HTS) for parasite research. The transition from standard 96-well formats to higher-density plates (384-well, 1536-well, and beyond) is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, enabling the rapid testing of thousands of compounds against pathogenic parasites such as Plasmodium and Trypanosoma [17] [18]. The following guides and FAQs are designed to help researchers navigate the practical challenges of assay miniaturization and automation, directly supporting methodologies in high-throughput parasite screening.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary factors to consider when choosing between a 96-well and a 384-well plate for a phenotypic screen of Plasmodium falciparum?

The choice involves a trade-off between throughput, sample volume, and experimental complexity [19].

- 96-well plates are suitable for smaller compound libraries or when larger sample volumes (typically 100-300 µL) are required for complex assay setups [20] [19]. They are also more amenable to manual pipetting.

- 384-well plates offer a four-fold increase in throughput and significantly reduce reagent and compound consumption, with well volumes typically ranging from 30-100 µL [20] [19]. This makes them ideal for large-scale HTS campaigns. However, they usually require automated liquid handling systems for efficient and accurate pipetting [20].

2. How does microplate color affect my assay readout in fluorescence-based parasite viability screens?

The microplate color is critical for optimizing signal-to-background ratios and minimizing well-to-well crosstalk [20].

- Black Microplates are recommended for standard fluorescence intensity assays (e.g., using fluorescent dyes like Hoechst 33342 [18]). The black color quenches signal, reducing background and crosstalk, which is vital when detecting strong signals [20].

- White Microplates are best for luminescence assays and time-resolved fluorescence (TRF) protocols, which typically have lower signal yields. The white color reflects the signal, maximizing the detected output [20].

- Clear Microplates are reserved for absorbance measurements, where light must pass through the sample [20].

3. My HTS data is showing a high rate of false positives. What are the common causes and solutions?

False positives are a well-known challenge in HTS and can arise from several factors [21]:

- Assay Interference: Compounds may chemically react with assay components, exhibit autofluorescence, or form colloidal aggregates that non-specifically inhibit enzymes [21].

- Solution: Implement counter-screens and use cheminformatic filters (e.g., pan-assay interference compound substructure filters) to triage HTS output [21]. The use of robust statistical methods for hit selection, such as setting a threshold at three standard deviations from the mean of control wells, is also recommended [17].

4. What are the key steps in validating a cell-based HTS assay for parasite drug discovery?

A robust HTS assay must be validated for performance and reproducibility [21].

- Robustness and Reproducibility: The assay should be optimized for miniaturization and automation, and tested for consistency across multiple experimental runs [21].

- Pharmacological Relevance: The assay should accurately reflect the biological pathway or phenotype being targeted [21].

- Statistical Validation: Use metrics like the Z′-factor to quantify the assay's suitability for HTS. A Z′-factor value of >0.5 is generally considered excellent for screening [6]. This involves measuring the signal-to-noise ratio by comparing positive and negative controls.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Signal or Poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Absorbance Readouts

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Incorrect Microplate Material: Standard polystyrene plates do not transmit UV light (<320 nm). For nucleic acid quantification (A260) or assays requiring UV light, use plates made from cyclic olefin copolymer (COC) or quartz [20].

- Absorbance Value Too High: For reliable quantitative measurements, absorbance values should ideally be between 0.1 and 1.0. Samples with absorbance greater than 3.0 are outside the reliable detection range and should be diluted [22].

- Suboptimal Sample Volume: As a general rule, the lowest recommended volume in a well is one-third of its maximum fill volume. For a standard 96-well plate (max 300 µL), do not go below 100 µL [20].

Problem: Inconsistent Results in a 384-Well Automated Screening Run

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Pipetting Errors: Automated liquid handlers require regular calibration. Check for clogged tips or inconsistent dispensing.

- Edge Effects: Evaporation in outer wells can cause inhomogeneity. Use a plate sealer and ensure consistent temperature regulation across the plate during incubation [23].

- Cell Settling or Clumping: For cell-based parasite assays (e.g., with T. brucei), ensure cells are homogeneously suspended before dispensing. Using U-bottom or C-bottom plates can facilitate mixing and prevent uneven cell distribution [20].

Problem: High Well-to-Well Crosstalk in Fluorescence Assay

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Incorrect Plate Color: As outlined in the FAQs, using a black microplate is essential for fluorescence assays to absorb stray light and prevent signal leakage between adjacent wells [20].

- Well Shape: Square wells with shared walls are more susceptible to crosstalk than round wells. If crosstalk is a significant issue, consider switching to a microplate with round wells [20].

- Signal Saturation: If very bright samples are adjacent to dim ones, optical crosstalk can occur even in black plates. Consider re-arranging samples or diluting highly fluorescent ones.

Experimental Protocol for an Image-Based Antimalarial HTS

This protocol is adapted from a published HTS for Plasmodium falciparum inhibitors [18].

1. Objective: To identify novel antimalarial compounds from a chemical library using an image-based phenotypic screen.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Parasites: Synchronized Plasmodium falciparum culture (e.g., strain 3D7).

- Compound Library: Pre-dispensed in 384-well glass-bottom microplates.

- Staining Solution: 1 µg/mL wheat agglutinin–Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate (stains RBCs) and 0.625 µg/mL Hoechst 33342 (stains nucleic acid) in 4% paraformaldehyde [18].

- Equipment: Automated plate washer, liquid handler, high-content imaging system (e.g., Operetta CLS).

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Compound Transfer. Using an automated liquid handler, transfer compounds from the library to the assay plate. The final test concentration is typically 10 µM.

- Step 2: Parasite Inoculation. Dispense synchronized P. falciparum schizont-stage cultures at 1% parasitemia and 2% hematocrit into the compound-treated assay plates.

- Step 3: Incubation. Incubate the plates for 72 hours at 37°C in a mixed-gas chamber (1% O₂, 5% CO₂, balanced N₂).

- Step 4: Staining and Fixation. After incubation, dilute the plates to 0.02% hematocrit and stain with the staining solution for 20 minutes at room temperature.

- Step 5: Image Acquisition. Acquire nine microscopy image fields from each well using a 40x water immersion lens.

- Step 6: Image Analysis. Transfer images to analysis software (e.g., Columbus). An algorithm is used to identify and classify parasites based on the fluorescent stains, quantifying parasite growth inhibition for each well.

4. Data Analysis:

- Hit Selection: Compounds that cause a reduction in parasite count exceeding a pre-defined threshold (e.g., three standard deviations from the mean of the DMSO control wells) are classified as "hits" [17].

- Dose-Response: Confirm "hits" by retesting in a dose-dependent manner (e.g., from 10 µM to 20 nM) to determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) [18].

Quantitative Data for Microplate Selection

Table 1: Comparison of Common Microplate Formats for HTS [20]

| Well Format | Total Wells | Typical Working Volume | Key Applications in Parasite HTS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 96-Well | 96 | 100 - 300 µL | Smaller-scale phenotypic screens, assay development. |

| 384-Well | 384 | 30 - 100 µL | Standard for large compound library screening against Plasmodium or Trypanosoma [18]. |

| 1536-Well | 1536 | 5 - 25 µL | Ultra-high-throughput screening (uHTS) for miniaturized assays; requires specialized automation [21]. |

| 3456-Well | 3456 | 1 - 5 µL | Specialized uHTS; not commonly used due to extreme handling requirements [20]. |

Table 2: Microplate Material and Color Selection Guide [20]

| Property | Options | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|

| Material | Polystyrene | Standard absorbance assays and microscopy (transmits visible light). |

| Cyclic Olefin Copolymer (COC) | UV light applications (e.g., DNA/RNA quantification). | |

| Polypropylene | PCR or sample storage (stable across a wide temperature range). | |

| Color | Clear | Absorbance assays (e.g., ELISA). |

| Black | Fluorescence intensity assays (reduces crosstalk). | |

| White | Luminescence and time-resolved fluorescence (TRF) assays. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

HTS Workflow for Parasite Screening

Microplate Format Selection Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for High-Throughput Parasite Screening

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| EZ DNA Methylation-Lightning Kit | Bisulfite conversion of DNA for methylation analysis [24]. | Epigenetic studies in parasite development or drug resistance. |

| NEBNext Ultra II End repair/dA-tailing Module | Prepares DNA ends for adapter ligation [25]. | Next-generation sequencing library preparation for parasite genomics. |

| NEB Blunt/TA Ligase Master Mix | Ligates barcodes and adapters to DNA fragments [25]. | Multiplexing samples for high-throughput sequencing. |

| Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit | Highly specific quantification of double-stranded DNA [25]. | Accurate DNA measurement pre- and post-library prep. |

| Wheat agglutinin–Alexa Fluor 488 | Fluorescently labels red blood cell membranes [18]. | Image-based HTS to distinguish host cells from background. |

| Hoechst 33342 | Cell-permeant nucleic acid stain [18]. | Image-based HTS to identify and quantify intracellular parasites. |

| AMPure XP Beads | Solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) for DNA size selection and clean-up [25]. | Purifying and size-selecting sequencing libraries. |

| Mao-IN-4 | Mao-IN-4, MF:C18H11Cl2N3OS, MW:388.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Aurein 2.4 | Aurein 2.4, MF:C77H133N19O19, MW:1629.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technical Support Center: High-Throughput Parasite Screening

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High False-Positive Rates in Primary Screening

- Problem: Initial HTS hits prove to be inactive in confirmatory assays.

- Solution:

- Confirm with Secondary Assays: Validate primary hits using an orthogonal assay with a different readout (e.g., follow a fluorescence-based assay with a microscopy-based viability check) [26] [27].

- Counter-Screens: Implement detergent-based or other counter-screens to identify and eliminate compounds that cause assay interference or non-specific binding [28].

- Check Compound Integrity: Confirm the identity and purity of the hit compounds to rule out degradation or mislabeling [27].

Issue 2: Poor Assay Performance (Low Z'-factor)

- Problem: The positive and negative controls in your assay plate are not well separated, leading to unreliable data.

- Solution:

- Optimize Reagents: Re-titrate key assay reagents, such as parasite density, substrate concentration, and incubation time, to improve the dynamic range [29] [27].

- Review Protocol: Check for inconsistencies in liquid handling, mixing, or incubation times that could increase variability. Automation can help standardize these steps [28].

- Aim for Z' > 0.5: A Z'-factor above 0.5 is generally considered acceptable for a robust HTS assay [6] [28].

Issue 3: Inconsistent Parasite Viability Measurements

- Problem: Cell viability readings are inconsistent across replicate wells.

- Solution:

- Standardize Culture: Ensure parasites are harvested during logarithmic growth phase and are maintained in a consistent, healthy state before the assay [6].

- Multiplexed Viability Readout: Incorporate a viability marker like thiazole red directly into a multiplexed flow cytometry assay to simultaneously measure metabolic activity and cell health [6].

- Use Validated Assays: Employ established cell viability or cytotoxicity assays, such as ATP-based luminescence assays, which are known for their sensitivity and wide dynamic range [27].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the recommended number of compounds to screen for a novel parasite target? Screening campaigns can range from focused libraries of 10,000 compounds to larger libraries exceeding 30,000 compounds. The size depends on the project goals and resources [26] [9]. For example, one study successfully identified hits by screening 10,000 drug-like molecules against Leishmania donovani, while another screened over 30,000 compounds for anthelmintic activity [26] [9].

Q2: How many technical and biological replicates are sufficient for an HTS campaign? For primary screening, duplicates or even single-point measurements are often used due to the high volume. However, all initial "hit" compounds must be confirmed in dose-response curves (IC50 determinations) with at least triplicate replicates and multiple biological repeats to ensure reproducibility and accurate potency measurement [26] [9].

Q3: What are the key parameters to prioritize hits before moving to medicinal chemistry? Beyond potency (IC50), key parameters include:

- Selectivity Index (SI): The ratio of cytotoxicity in mammalian cells to anti-parasitic activity. An SI > 10 is often considered favorable [26].

- Drug-Likeness: Predicted ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion) properties should indicate a high probability of oral bioavailability and a low risk of adverse effects [26].

- Morphological Assessment: Confirmation of anti-parasitic activity through visual techniques like scanning electron microscopy, which can reveal compound-induced physical damage to the parasites [26].

Q4: Our laboratory is new to HTS. What are the essential components for setting up a screening pipeline? A basic HTS pipeline requires:

- Compound Library: A curated collection of small molecules.

- Assay Reagents: Optimized biological components (e.g., stable parasite lines, substrates, buffers).

- Automation: Liquid handling robots for dispensing into microtiter plates (96, 384, or 1536-well format) [28].

- Detection Instrumentation: Plate readers or flow cytometers capable of measuring fluorescence, luminescence, or absorbance [27] [6].

- Data Analysis Software: Tools for data normalization, hit identification, and statistical analysis [28].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Representative Quantitative Data from Recent HTS Campaigns Against Parasites

| Parasite | Library Size | Primary Hits (>80% Inhibition) | Confirmed Hits (IC50 < 10 µM) | Key Assay Type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leishmania donovani | 10,000 | 99 | 4 | Cell viability / Phenotypic | [26] |

| Gastrointestinal Nematodes | 30,238 | 55 (Broad-spectrum) | 1 novel scaffold (F0317-0202) | Motility / Phenotypic | [9] |

| Trypanosoma brucei | 14,976 | 28 (Repeatable activity) | 1 (Low µM EC50) | Multiplexed Flow Cytometry | [6] |

Detailed Protocol: Multiplexed Flow Cytometry Screening for Glycolytic Probes in Trypanosoma brucei [6]

- Preparation of Biosensor Cell Lines: Transfect T. brucei bloodstream form parasites with biosensors for glucose (FRET-based), ATP (FRET-based), and glycosomal pH (GFP-based).

- Cell Pooling and Plating: Pool the sensor cell lines and dispense them into assay plates containing the compound library using automated liquid handling.

- Compound Incubation: Incubate the plates to allow compounds to take effect.

- Flow Cytometry Analysis: Analyze the plates using a high-throughput flow cytometer. The system simultaneously measures:

- FRET signals for glucose or ATP levels.

- GFP fluorescence for organelle pH.

- Thiazole red fluorescence for cell viability.

- Data Processing: Calculate Z'-factors for each biosensor readout to validate assay quality. Identify hits that cause significant changes in the measured metabolites compared to controls.

- Hit Confirmation: Re-test primary hits in dose-response experiments to determine EC50 values for the relevant sensors.

Detailed Protocol: High-Throughput Phenotypic Screening for Anti-Leishmanial Compounds [26]

- Parasite Culture: Maintain Leishmania donovani promastigotes or amastigotes in appropriate culture media.

- Assay Setup: Use automation to dispense parasites into 384-well plates. Add compounds from the library (e.g., 10,000 compounds from ChemDiv) at a single concentration (e.g., 50 µM).

- Incubation: Incubate plates for a predetermined period (e.g., 72 hours) to allow compound action.

- Viability Measurement: Add a cell viability indicator (e.g., alamarBlue or resazurin) and measure fluorescence or absorbance.

- Hit Identification: Calculate percent inhibition relative to untreated (100% viability) and compound-only (0% viability) controls. Select compounds showing >80% inhibition as primary hits.

- Dose-Response Confirmation: Re-test primary hits in a dilution series to determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50).

- Secondary Assays:

- Cytotoxicity: Assess hits against mammalian cell lines (e.g., THP-1, J774) to calculate the Selectivity Index.

- Morphology: Use scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to examine compound-induced morphological alterations in the parasites.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

HTS Drug Discovery Cascade

Multiplexed Biosensor Screening

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for High-Throughput Parasite Screening

| Item | Function & Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Libraries | Collections of small molecules for screening against parasitic targets. | In-house ChemDiv library [26]; Life Chemicals Compound Library [6]; Target-focused (kinase, GPCR) libraries [9]. |

| Cell Viability Assays | Measure parasite metabolic activity or membrane integrity to assess compound lethality. | Fluorescence (e.g., alamarBlue) or luminescence (ATP-based) readouts [26] [27]. |

| Biosensor Cell Lines | Genetically engineered parasites expressing fluorescent reporters to monitor specific metabolic pathways in live cells. | FRET-based glucose/ATP sensors; GFP-based pH sensors [6]. |

| Automation Platforms | Robotics for precise, high-speed dispensing of liquids into microtiter plates. | Tecan or Hamilton liquid handlers; 384-well or 1536-well plate formats [28]. |

| Detection Instruments | Devices to measure assay signals from microtiter plates or cell suspensions. | Multimode plate readers (absorbance, fluorescence); High-throughput flow cytometers [6] [28]. |

| Antigen Detection Kits | Immunoassays (EIA, DFA, rapid tests) for specific, morphology-independent parasite diagnosis. | Commercial kits for Cryptosporidium, Giardia, and Entamoeba histolytica [30]. |

| iRGD-CPT | iRGD-CPT, MF:C75H100N18O27S3, MW:1781.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Mbl-IN-2 | Mbl-IN-2, MF:C9H12F3NO3S, MW:271.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Addressing Parasitic Disease Burden Through Scalable Screening Solutions

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main limitations of traditional diagnostic methods I might use in my research, and why are they unsuitable for high-throughput screening?

Traditional methods like microscopy, serology, and histopathology, while foundational, have several limitations for scalable screening. They are often time-consuming, require a high level of technical expertise, and are impractical in resource-limited settings. Their sensitivity and specificity can be variable, making them less reliable for large-scale or surveillance studies where high throughput and accuracy are critical [31].

Q2: Which advanced molecular techniques are most suitable for developing a high-throughput screening pipeline?

Several advanced techniques have shown great promise for scalable screening:

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and Digital PCR: These methods offer enhanced sensitivity and specificity for detecting parasite DNA, even in cases of low parasitemia [31].

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): NGS allows for the untargeted discovery of pathogens, detailed genomic characterization, and the ability to track drug resistance markers, making it powerful for comprehensive screening [31].

- Loop-mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP): This technique is particularly valuable for field applications or resource-limited settings as it does not require sophisticated thermocycling equipment and provides rapid results [31].

- CRISPR-Cas Systems: Emerging CRISPR-based diagnostics offer high specificity, portability, and potential for rapid, point-of-care detection of parasitic DNA or RNA [31].

Q3: How can "signature-based" diagnostics improve the accuracy of parasitic disease detection?

Signature-based diagnostics move beyond reliance on a single biomarker. Instead, they utilize a unique combination of multiple biomarkers—a diagnostic "fingerprint"—for a specific disease state. This approach can significantly improve both diagnostic accuracy and specificity. For example, a signature might combine specific parasite antigens with host-derived antibodies or cytokines to create a more robust and reliable diagnostic panel than any single marker could provide [32].

Q4: What are the key considerations for integrating Point-of-Care (POC) tests into a large-scale screening strategy?

When planning for POC integration, focus on tests that are:

- Rapid and Simple: They should deliver results quickly and require minimal training to administer.

- Equipment-Independent: Ideal POC tests for scalable screening do not rely on complex lab equipment.

- Stable: They must remain effective in various environmental conditions, especially when deployed in the field. The goal of POC testing is to enable rapid and accurate detection at or near the patient care site, which is vital for screening in remote or endemic areas without centralized laboratories [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Sensitivity in Molecular Detection

Problem: Your PCR or other molecular assay is failing to detect known positive samples, indicating low sensitivity.

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Inadequate DNA/RNA extraction | Optimize the extraction protocol for the specific sample type (e.g., blood, stool). Include a sample preparation step that efficiently breaks down tough parasite structures. |

| Inhibitors present in the sample | dilute the nucleic acid template or use purification kits designed to remove common inhibitors like heme or humic acids. Incorporate an internal control to detect the presence of inhibitors. |

| Suboptimal primer/probe design | Re-design primers and probes to target multi-copy genes or conserved regions specific to your parasite of interest. Validate them against a panel of well-characterized positive and negative controls. |

Issue 2: Inconsistent Results in Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs)

Problem: Lateral flow immunoassays (RDTs) are producing variable results, including false negatives or faint test lines.

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Improper storage or expired tests | Strictly adhere to manufacturer storage recommendations (often 2-30°C). Never use tests beyond their expiration date. |

| Deviation from protocol | Ensure precise sample and buffer volumes. Use a timer to adhere strictly to the recommended reading time, as reading too early or too late can cause errors. |

| Prozone effect (high analyte concentration) | If antigen levels are very high, it can paradoxically cause a false negative. Dilute the sample and re-run the test to check for a positive result. |

| Low parasite burden | Be aware that RDTs may fail during the early or chronic phases of infection when antigen/antibody levels are low. Confirm with a more sensitive molecular method [31]. |

Issue 3: High Background Noise in Serological Assays (e.g., ELISA)

Problem: Your ELISA plate shows high background signal, reducing the signal-to-noise ratio and making results difficult to interpret.

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Insufficient washing | Increase the number of wash cycles after each incubation step and ensure the wash buffer is fresh and correctly prepared. |

| Non-specific antibody binding | Include a protein blocking step (e.g., with BSA or non-fat dry milk) prior to adding the primary antibody. Titrate antibodies to find the optimal concentration that maximizes specific signal and minimizes background. |

| Contaminated reagents | Prepare fresh reagents and ensure all buffers are free of microbial contamination. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Multiplex PCR for Parallel Pathogen Detection

Objective: To simultaneously detect and differentiate multiple parasitic pathogens in a single reaction, increasing screening throughput.

Materials:

- Template DNA from patient samples

- Multiplex PCR Master Mix (containing buffer, dNTPs, hot-start polymerase)

- Primer mix (multiple primer pairs specific to different parasite targets, designed to have similar annealing temperatures)

- Thermocycler

- Gel electrophoresis equipment or capillary electrophoresis system for analysis

Methodology:

- Primer Design: Design primers to generate amplicons of distinct sizes for each target (e.g., 100bp, 200bp, 300bp) to allow for clear differentiation by gel electrophoresis. Ensure all primers have minimal self-complementarity and similar melting temperatures.

- Reaction Setup: Prepare the PCR reaction on ice. A typical 25µL reaction may contain: 12.5µL Master Mix, 2.5µL primer mix, 5µL template DNA, and nuclease-free water up to 25µL.

- Thermocycling: Use a standardized cycling protocol:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 5 minutes

- 35-40 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds

- Annealing: 60°C for 30 seconds (optimize temperature based on primers)

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute

- Final Extension: 72°C for 7 minutes

- Analysis: Separate the PCR products by gel electrophoresis. The presence of specific bands, corresponding to the expected sizes, indicates detection of that particular parasite.

Protocol 2: Biomarker Signature Validation using a Microfluidic Immunoassay

Objective: To validate a panel of putative biomarkers (a signature) for a specific parasitic disease using a highly parallelized microfluidic chip.

Materials:

- Microfluidic chip with multiple parallel chambers, each pre-functionalized with a capture antibody for a different biomarker [32].

- Fluorescently-labeled detection antibodies.

- Patient serum or plasma samples.

- 1X PBS buffer and blocking buffer (e.g., 1% BSA in PBS).

- Fluorescence scanner or microscope for detection.

Methodology:

- Chip Preparation: Prime the microfluidic channels with PBS. Load the blocking buffer to cover all potential protein-binding sites and incubate.

- Sample Incubation: Introduce the patient sample into the chip. Biomarkers of interest will bind specifically to their corresponding capture antibodies in the different chambers.

- Washing: Flush the chip with PBS buffer to remove unbound proteins and sample matrix.

- Detection: Introduce a mixture of fluorescent detection antibodies. Each detection antibody will bind to its specific captured biomarker.

- Final Wash and Reading: Perform a final wash to remove unbound detection antibodies. Scan the chip to measure the fluorescence intensity in each chamber.

- Data Analysis: The fluorescence pattern across the chambers constitutes the biomarker signature. Use statistical or machine learning models to determine if this signature accurately classifies the sample as infected or not, and potentially by which parasite [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Parasite Screening |

|---|---|

| Monoclonal Antibodies | Highly specific reagents used in immunoassays (ELISA, RDTs, microfluidics) to capture and detect parasite-specific antigens with high consistency [32]. |

| Primers/Probes for qPCR | Oligonucleotides designed to target unique genomic sequences of parasites, enabling highly sensitive and quantitative detection of parasite DNA/RNA in patient samples [31]. |

| CRISPR-Cas Enzymes (e.g., Cas12a, Cas13) | Used in novel diagnostic platforms for their ability to specifically cleave parasite nucleic acids, often coupled with a reporter molecule for highly sensitive and specific point-of-care detection [31]. |

| Functionalized Magnetic Nanoparticles | Nanoparticles coated with antibodies or other capture molecules are used to isolate and concentrate specific parasites or their biomarkers from complex sample matrices like blood or stool, improving downstream assay sensitivity [31]. |

| Reference Genomic DNA | Purified DNA from well-characterized parasite strains serves as essential positive controls for validating molecular assays like PCR and NGS, ensuring accuracy and reliability [33]. |

| Synthetic Biomarker Panels | Defined mixtures of synthetic antigens or nucleic acids representing a diagnostic "signature." These are used to develop, optimize, and calibrate multi-analyte screening tests [32]. |

| Eupenicisirenin C | Eupenicisirenin C, MF:C13H18O4, MW:238.28 g/mol |

| Sydowimide A | Sydowimide A, MF:C15H16N2O4, MW:288.30 g/mol |

Advanced HTS Applications: From Molecular Detection to Phenotypic Drug Screening

The accurate detection of low-density malaria parasitemias is a critical challenge in elimination settings. Conventional molecular methods typically evaluate finger-prick capillary blood samples (∼5 μl), limiting detection to parasite densities above approximately 200 parasites/mL [34]. To address this sensitivity barrier, researchers have developed a highly sensitive "high-volume" quantitative PCR (qPCR) method based on Plasmodium sp. 18S RNA, adapted for blood sample volumes of ≥250 μl [34]. This technical support center provides comprehensive guidance for implementing this methodology within high-throughput parasite screening programs, addressing common experimental challenges and providing validated solutions for the research community.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Core High-Volume qPCR Methodology

Blood Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

- Sample Collection: Collect whole blood samples (1 ml) in EDTA tubes [34]

- Processing: Centrifuge at 2,500 rpm for 10 min to remove all plasma together with 70-100 μl of the buffy coat per 1 ml of whole blood [34]

- Storage: Freeze the packed red blood cells (RBCs) at -30°C until DNA extraction [34]

- DNA Extraction: Use QIAamp blood minikit for sample volumes ≤200 μl or QIAamp blood midi kit for volumes between 200-2,000 μl packed RBCs [34]

- DNA Concentration: Completely dry purified DNA in a centrifugal vacuum concentrator and resuspend in a small volume of PCR-grade water to create a concentrate (1 μl template corresponds to 100 μl of whole blood) [34]

Quantitative Real-Time PCR Setup

- Template Volume: Use 2-μl aliquot of concentrated DNA per qPCR reaction [34]

- Chemistry: QuantiTect multiplex PCR NoROX with 1× QuantiTect buffer, 0.4 μM each primer, and 0.2 μM hydrolysis probe [34]

- Thermocycling Conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 15 minutes

- Amplification: 50 cycles of 94°C for 15s (denaturation) and 60°C for 60s (annealing/extension) [34]

- Internal Control: Multiplex human beta-actin gene assay to monitor reaction efficiency [34]

Workflow Visualization

Performance Characteristics & Validation Data

Analytical Performance Metrics

Table 1: Validation Parameters of High-Volume qPCR for Malaria Detection

| Validation Parameter | Performance Result | Reference Method Comparison |

|---|---|---|

| PCR Efficiency | 90-105% | Similar to conventional qPCR |

| Analytical Detection Limit (LOD) | 22 parasites/mL (95% CI: 21.79-74.9) | 50x more sensitive than conventional PCR from filter paper [34] |

| Diagnostic Specificity | 99.75% | Comparable to established molecular methods [34] |

| Sample Throughput | ~700 samples/week | Higher than manual extraction methods [34] |

| Blood Volume Processed | ≥250 μL | 50x larger than standard 5μL filter paper spots [34] |

| Dynamic Range | 20 - 250,000 parasites/mL | Broader than microscopy and RDTs [34] |

Comparative Method Performance

Table 2: Comparison of Malaria Diagnostic Methods for Low-Density Infections

| Method | Effective Blood Volume | Limit of Detection | Throughput | Suitable for Asymptomatic Screening |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Volume qPCR | ≥250 μL | 22 parasites/mL | High (700 samples/week) | Yes [34] |

| Conventional PCR | 2-5 μL | ~1,000 parasites/mL | Moderate | Limited [34] |

| Droplet Digital PCR | Varies | <1 parasite/μL | Moderate | Yes [35] |

| Light Microscopy | 0.025-0.0625 μL | 50-100 parasites/μL | Low | No [35] |

| Rapid Diagnostic Tests | Varies | ~100-200 parasites/μL | High | Limited [36] [37] |

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of high-volume qPCR over conventional molecular methods for malaria detection?

High-volume qPCR increases the effective blood volume processed by 50-100 times compared to conventional methods that use only 2-5μL of blood [34]. This substantially improves the limit of detection to 22 parasites/mL, enabling identification of low-density infections that would be missed by standard PCR, microscopy, or rapid diagnostic tests [34]. These submicroscopic infections are increasingly recognized as important reservoirs for ongoing malaria transmission.

Q2: How should we handle inconsistent results between technical replicates in low-density samples?

For samples with densities <2 copies/μL, some replicates may return negative results due to stochastic effects [35]. We recommend:

- Running triplicate reactions for all samples

- Considering a sample positive if ≥2/3 replicates are positive

- Using a standardized DNA concentration method to minimize variation

- Implementing droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) for absolute quantification if replicate inconsistency persists, as ddPCR shows higher reproducibility for low-template samples [35]

Q3: What quality control measures are essential for reliable high-volume qPCR results?

Implement a comprehensive QC system including:

- Standard curves using FACS-sorted ring-stage parasites (range: 20-10,000 parasites) [34]

- Internal control (human beta-actin) multiplexed in each reaction [34]

- Extraction controls with known parasite densities in uninfected whole blood

- Regular monitoring of PCR efficiency (maintain 90-105%)

- Prospective CT cutoff set at 40 cycles to maximize sensitivity while maintaining specificity [34]

Q4: How does high-volume qPCR compare to emerging diagnostic technologies like droplet digital PCR?

While high-volume qPCR provides excellent sensitivity and throughput for population screening, ddPCR offers advantages in absolute quantification without standard curves and better reproducibility at very low parasite densities [35]. However, high-volume qPCR remains more practical for large-scale studies, processing ~700 samples weekly with automated systems [34]. The choice depends on study objectives: high-volume qPCR for high-throughput screening and ddPCR for precise quantification in mechanistic studies.

Q5: What are the common sources of false positives and how can they be minimized?

False positives in high-volume qPCR primarily occur due to contamination during sample processing. Root cause analysis identified these key areas [34]:

- Cross-contamination during DNA extraction: Use separated pre- and post-PCR areas

- Carryover during sample concentration: Implement unidirectional workflow

- Amplicon contamination: Use uracil-N-glycosylase systems and thorough cleaning Maintain diagnostic specificity >99.7% through rigorous contamination control protocols and include no-template controls in every run [34].

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for High-Volume qPCR Implementation

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Their Applications in High-Volume qPCR

| Reagent/Equipment | Specification | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp blood minikit (≤200μL) or midi kit (200-2,000μL) [34] | Parasite DNA purification from packed RBCs |

| qPCR Master Mix | QuantiTect multiplex PCR NoROX [34] | Amplification with optimized buffer system |

| Primers/Probes | Plasmodium 18S rRNA-targeting with hydrolysis probes [34] | Species-specific detection and quantification |

| Internal Control Assay | Human beta-actin primers/probe [34] | Monitoring extraction and amplification efficiency |

| Reference Standards | FACS-sorted P. falciparum 3D7 ring stages [34] | Standard curve generation for absolute quantification |

| Automated Extraction System | QIAsymphony with DSP DNA midi kit [34] | High-throughput, reproducible DNA purification |

Advanced Applications in Parasite Screening

Integration with High-Throughput Surveillance Strategies

High-volume qPCR represents a cornerstone technology for modern malaria surveillance programs aiming for elimination. Its exceptional sensitivity (50-fold greater than conventional PCR) enables detection of the "submicroscopic reservoir" - asymptomatic individuals with low parasite densities who contribute significantly to transmission [34]. When processing 700 samples weekly, this method facilitates large-scale screening of populations in pre-elimination settings, providing crucial data for targeted intervention strategies [34].

The methodology is particularly valuable for:

- Molecular Monitoring of Interventions: Tracking real-time changes in parasite prevalence following control measures

- Asymptomatic Carrier Detection: Identifying reservoirs in low-transmission settings [38]

- Drug Efficacy Studies: Detecting emerging resistance through precise parasite density measurements

- Vaccine Trials: Providing sensitive endpoints for protective efficacy assessment

For comprehensive malaria surveillance programs, high-volume qPCR can be integrated with complementary approaches including bead-based antigen detection for high-throughput screening [37] and droplet digital PCR for absolute quantification in research applications [35]. This multi-platform approach provides program managers with the granular data needed to make informed decisions about intervention strategies in the pursuit of malaria elimination.

Image-Based High-Content Screening for Natural Product Discovery Against Trichomonas vaginalis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why is a resazurin-based assay insufficient for our anti-T. vaginalis screening, and what is a superior alternative?

Answer: Resazurin assays lack sensitivity for detecting partial inhibition at standard inoculum sizes. A population of approximately 10,000 trichomonads per well in a 96-well plate is the threshold for a consistent signal, meaning a compound achieving 75% parasite kill could be misclassified as inactive. An image-based, high-content assay is a validated superior alternative. This method fixes parasites with glutaraldehyde and uses a dual cell-staining system with acridine orange (cell-permeable, stains all cells) and propidium iodide (cell-impermeant, stains only dead cells) for precise live/dead determination. This assay is robust (Z-factor of 0.92), can detect as few as one trichomonad per image field, and is compatible with colored or UV-active natural products, as images can be manually inspected to rule out interference [39].

FAQ 2: How do we address rapid parasite movement that causes blurring in live-cell imaging?

Answer: The rapid movement of flagellated trichomonads, which causes blurring even with fast exposure times, is resolved by fixing the cells with glutaraldehyde prior to imaging. This process halts all motion, enabling clear and quantifiable imaging of individual parasites for subsequent live/dead analysis using fluorescent DNA stains [39].

FAQ 3: Our natural product extracts are colored or fluorescent. Will this interfere with the assay readout?

Answer: Unlike colorimetric or fluorescence-intensity-based assays, the image-based high-content assay is highly resilient to such interference. While colored compounds can quench signals in other assay formats, the direct visualization and counting of individual cells in this platform allow for manual inspection of stored image files to identify and discount any potential false positives or negatives caused by interfering properties of the test substances [39].

FAQ 4: What is an appropriate vehicle for compound testing, and at what concentration?

Answer: Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) is an acceptable vehicle for compound testing. A concentration of 1% by volume has been demonstrated to have no detrimental impact on the viability of T. vaginalis cells and is therefore suitable for use in this assay [39].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Image-Based High-Content Screening Assay forT. vaginalisViability

This protocol is adapted from the method developed to test a library of fungal natural product extracts and pure compounds [39].

1. Principle The assay fixes trichomonads to eliminate motility-based blurring and uses a dual fluorescent DNA stain to differentiate live from dead cells based on membrane integrity. Acridine orange penetrates all cells, while propidium iodide only penetrates cells with compromised membranes.

2. Materials

- Parasite Strain: T. vaginalis (e.g., ATCC strain)

- Culture Medium: Trypticase-yeast extract-maltose (TYM) or Diamond's medium, pH ~6.2 [40]

- Fixative: Glutaraldehyde solution

- Stains: Acridine Orange (AO) and Propidium Iodide (PI)

- Equipment: High-content imaging system (e.g., Operetta, PerkinElmer), 96-well or 384-well microtiter plates, anaerobic chamber or sealed environment for incubation [39]

3. Step-by-Step Procedure Step 1: Parasite Inoculation

- Harvest mid-logarithmic phase T. vaginalis cells by low-speed centrifugation.

- Resuspend parasites in fresh culture medium and adjust concentration.

- Dispense 40,000 trichomonads in a volume of 100-200 µL into each well of a 96-well microtiter plate. Include negative (medium only) and positive (untreated parasites) controls [39].

Step 2: Compound Addition

- Add test compounds, extracts, or controls (e.g., 25 µM metronidazole as a positive control) to respective wells. The final concentration of DMSO should not exceed 1% [39].

- Seal plates to maintain anaerobic conditions and incubate at 37°C for 24-48 hours.

Step 3: Fixation and Staining

- Carefully add glutaraldehyde to each well to a final concentration sufficient to fix cells (e.g., 0.5-1.0%). Incubate for a fixed time at room temperature.

- Remove fixative and wash cells with buffer if necessary.

- Add a solution containing both Acridine Orange and Propidium iodide to stain the fixed cells.

- Incubate in the dark for a predetermined time [39].

Step 4: Imaging and Analysis

- Image each well using a high-content imager, capturing at least two image fields per well.

- Use appropriate excitation/emission filters for AO (e.g., 502/526 nm, green) and PI (e.g., 536/617 nm, red).

- Employ analysis software to count total cells (AO-positive) and dead cells (PI-positive). The number of live cells is calculated as the difference [39].

Protocol 2: Validation with a Phenol Red pH-Based Growth Assay

This protocol provides a simpler, cost-effective complementary method for growth assessment [40].

1. Principle Trichomonad growth in culture medium produces acidic metabolites that lower the pH. The color change of the phenol red indicator from red (pH ~7.4) to yellow (pH ~6.0) can be used as a quantitative and qualitative indicator of growth.

2. Materials

- Phenol red-containing culture medium

- 96-well or 384-well microtiter plates

- Plate reader (to measure absorbance at ~560 nm)

3. Procedure

- Inoculate parasites into phenol red-containing medium in microtiter plates as in Protocol 1, Step 1.

- After incubation, measure the absorbance of the medium. A decrease in absorbance correlates with a drop in pH and increased parasite growth.

- This assay has demonstrated consistent dynamic ranges with Z′-factor values of 0.741 (384-well) and 0.870 (96-well), confirming its robustness for screening [40].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Screening Assays for T. vaginalis

| Assay Type | Key Metric | Value | Significance/Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Image-Based High-Content [39] | Z-factor | 0.92 | Excellent robustness for high-throughput screening. |

| Detection Limit | 1 cell/field | Highly sensitive, can detect very low parasite numbers. | |

| Phenol Red (pH-Based) [40] | Z'-factor (384-well) | 0.741 | Robust for medium-throughput screening. |

| Z'-factor (96-well) | 0.870 | Robust for high-throughput screening. | |

| Resazurin-Based [39] | Detection Threshold | ~10,000 cells/well | Low sensitivity; may miss partial inhibition. |

Table 2: Exemplar Hit Compound from a Natural Product Screen

| Compound Name | Class | ECâ‚…â‚€ vs. T. vaginalis | Selectivity Index (SI) vs. 3T3 cells | Selectivity Index (SI) vs. Ect1 cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrrolocin A [39] | Decalin-linked tetramic acid | 60 nM | 100 | 167 |

| 2-Bromoascididemin [39] | Not Specified | Not Specified | 14 | Not Specified |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Image-Based HTS

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Assay | Key Details & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Acridine Orange | Cell-permeant nucleic acid stain. Labels all cells (live and dead). | Used in combination with PI for live/dead determination in fixed cells [39]. |

| Propidium Iodide (PI) | Cell-impermeant nucleic acid stain. Labels only dead/damaged cells. | Used in combination with AO. PI-positive cells are counted as dead [39]. |

| Glutaraldehyde | Fixative. Cross-links proteins, immobilizing parasites for clear imaging. | Eliminates motility-induced blurring. Concentration and exposure time must be optimized [39]. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Universal solvent for hydrophobic compounds and natural product extracts. | Final concentration in assay should be ≤1% to avoid cytotoxicity to parasites [39]. |

| Metronidazole | Nitroimidazole drug; standard positive control for inhibition. | Used as a reference compound (e.g., 25 µM) to validate assay performance [39]. |

| Phenol Red | pH indicator in culture medium. | Allows for chromogenic, growth-based screening in 96-/384-well formats [40]. |

| Hsd17B13-IN-32 | Hsd17B13-IN-32, MF:C23H15Cl2N5O3, MW:480.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Parp7-IN-17 | Parp7-IN-17, MF:C20H20F3N7O2, MW:447.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

High-Throughput Screening Workflow

Real-Time Motility Monitoring for Anthelmintic Drug Screening and Resistance Diagnosis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: Our motility readings for a known anthelmintic drug show high variability between assay plates. What could be causing this inconsistency?

A: Inconsistent results can stem from several sources related to parasite preparation and assay conditions.

- Parasite Health: Ensure parasites are harvested from synchronized cultures and are in the same developmental stage. Using a mix of stages can lead to differential drug responses [41] [42].

- Culture Conditions: Maintain strict temperature control. For example, Strongyloides ratti L3 are assayed at 21°C, while adult hookworms require 37°C [41] [42]. Evaporation can be minimized by filling inter-well spaces with PBS [41].

- Drug Preparation: Use a consistent DMSO concentration across all wells and dilutions. High concentrations can be toxic and confound results [43].

- Instrument Calibration: Perform regular background readings and calibrations as specified by the instrument manufacturer (e.g., the xCELLigence system or WMicrotracker) before initiating experiments [41] [43].

Q2: We are not detecting a significant motility phenotype for a compound that is known to be effective in vivo. Is our assay failing?

A: Not necessarily. Many effective anthelmintics require host immune components for full efficacy and may only produce subtle or "cryptic" phenotypes in vitro [44] [45].

- Phenotype Expansion: Move beyond simple motility reduction. Investigate other endpoints like oscillation frequency, movement speed, or changes in movement patterns (e.g., from sinusoidal to hyperactive/paralytic) [46]. High-content imaging combined with machine learning can analyze these complex phenotypes [44] [45].

- Assay Modification: Consider co-culturing parasites with host immune cells (e.g., neutrophils or peripheral blood mononuclear cells) to make the environment more "in vivo like." Drugs like ivermectin and diethylcarbamazine show enhanced activity in the presence of immune cells [44].

- Life Stage Consideration: Test the compound on different life stages (L3 larvae, adults) as sensitivity can vary significantly [41] [42].

Q3: How can we distinguish between a true resistance profile and a false positive caused by poor worm health in our resistance diagnosis assay?

A: Robust internal controls are essential.

- Control Strains: Always include known drug-susceptible and drug-resistant parasite isolates in parallel. The assay should clearly differentiate their motility responses, as demonstrated with Haemonchus contortus strains [41] [43].

- Viability Control: Include a vehicle control (e.g., DMSO) to confirm baseline parasite motility and health throughout the assay duration.

- Reference Drug: Use a reference anthelmintic with a well-defined mechanism of action. A significant shift in the ICâ‚…â‚€ value of the reference drug in your test isolate, compared to a susceptible one, indicates resistance [43].

Q4: Our high-throughput screen of a large compound library identified hits that paralyze worms, but we are concerned these may not translate to in vivo efficacy. How can we prioritize hits?

A: This is a common challenge. Prioritization should be based on a multi-parameter approach.

- Phenotypic Profiling: Use high-content imaging to determine if the paralysis is accompanied by other damaging effects, such as tegument disruption, which is a stronger indicator of irreparable damage [45].

- Chemical Properties: Filter hits based on novelty, pharmacokinetic properties (Cmax, T1/2), and cytotoxicity in mammalian cells [18].

- Secondary Assays: Subject hits to more physiologically relevant secondary assays, such as larval migration or development assays, to confirm efficacy [44].

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol 1: Motility-Based Drug Screening on Larval Nematodes

This protocol is adapted for use with the WMicrotracker (WMA) system and third-stage larvae (L3) [43].

1. Reagent Preparation:

- Compound Plates: Prepare a dilution series of test compounds in DMSO in 96- or 384-well plates. The final DMSO concentration in the assay should not exceed 1% [43].

- Assay Buffer: Use an appropriate buffer, such as 0.5x PBS or culture medium, depending on the parasite species [41].

2. Parasite Preparation:

- Source: Harvest H. contortus L3 larvae from fecal cultures using standard migration techniques [41] [42].

- Concentration: Adjust the larval suspension to a density of approximately 3,000 L3 per 200 µL of assay buffer [41].

3. Assay Execution:

- Dispensing: Transfer 180 µL of the larval suspension to each well of the assay plate.

- Baseline Reading: Place the plate in the WMicrotracker and record baseline motility for 1-2 hours.

- Drug Addition: Add 20 µL of the 10x concentrated drug solution (or DMSO control) to the respective wells.

- Data Acquisition: Monitor and record motility continuously for 24-72 hours. The instrument automatically quantifies movement as a Cell Index or arbitrary motility units [43].

4. Data Analysis:

- Normalize motility data to the pre-drug baseline.

- Generate dose-response curves and calculate half-maximal inhibitory concentration (ICâ‚…â‚€) values using non-linear regression analysis.

Protocol 2: Phenotypic Resistance Diagnosis in Field Isolates

This protocol allows for the detection of macrocyclic lactone (ML) resistance in nematodes like H. contortus [43].

1. Isolate Collection:

- Collect eggs from sheep feces from both a farm with suspected resistance (based on FECRT) and a farm with known drug efficacy [43].

- Harvest L3 larvae from these eggs through standard laboratory culture.

2. Motility Assay:

- Follow the drug screening protocol (Protocol 1) using a dilution series of ML drugs (e.g., ivermectin, moxidectin, eprinomectin).

- Test the susceptible and suspected resistant isolates on the same plate to ensure direct comparability.

3. Analysis and Interpretation:

- Calculate the ICâ‚…â‚€ for each drug-isolate combination.

- Determine the Resistance Factor (RF) using the formula:

RF = ICâ‚…â‚€ (field isolate) / ICâ‚…â‚€ (susceptible isolate). - An RF significantly greater than 1 indicates a resistant phenotype. The WMA has successfully discriminated isolates with a 2.12-fold reduction in ivermectin sensitivity [43].

Table 1: Instrument Comparison for Real-Time Motility Monitoring

| Instrument / Platform | Technology Principle | Key Applications | Throughput | Reported Parasite Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| xCELLigence (RTCA) | Measures electrical impedance changes caused by parasite movement on microelectrodes [41] [42] | Drug screening, ICâ‚…â‚€ determination, resistance diagnosis [41] [42] | High (96-well plate format) [41] | H. contortus L3, S. ratti L3, adult hookworms, adult S. mansoni [41] [42] |

| WMicrotracker (WMA) | Uses infrared light to detect interruptions in a beam grid caused by moving organisms [43] | Drug screening, resistance detection, high-throughput compound library screening [43] | High (96- and 384-well compatible) [43] | C. elegans, H. contortus L3 [43] |

| Lensless Holographic Imaging | Records time-varying holographic speckle patterns; analyzes motion via computational algorithms [47] | Sensitive detection of motile pathogens in bodily fluids (e.g., blood, CSF) for diagnosis [47] | Medium (screens ~3.2 mL in 20 min) [47] | Trypanosoma brucei, T. cruzi, T. vaginalis [47] |

Table 2: Exemplar Motility-Based Drug Response Data

| Parasite / Strain | Drug | Reported ICâ‚…â‚€ (nM) | Resistance Factor (RF) | Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. elegans (IVR10) | Ivermectin | Not specified | 2.12 | IVM-selected strain vs. wild-type N2B [43] |

| H. contortus (Susceptible) | Moxidectin | Most potent among MLs | - | Compared to IVM and EPR; highest efficacy observed [43] |

| H. contortus (Resistant) | Eprinomectin | Significant increase | Substantial RF | Isolate from a farm with EPR-treatment failure [43] |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Workflow for Motility-Based Screening

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Usage in Context |

|---|---|---|

| xCELLigence RTCA E-Plate | Specialized microtiter plate with integrated gold microelectrodes for label-free, real-time monitoring of parasite motility via electrical impedance [41] [42]. | Used for screening against larval and adult stages of helminths like H. contortus and S. mansoni [41] [42]. |

| WMicrotracker Assay Plates | Microplates designed for use with the WMicrotracker system, which uses infrared light beams to detect organism movement in a high-throughput format [43]. | Employed for high-throughput drug screening on C. elegans and H. contortus L3, and for assessing macrocyclic lactone resistance [43]. |

| Synchronized Parasite Cultures | Populations of parasites (eggs, larvae, adults) at the same developmental stage, crucial for obtaining consistent and reproducible drug response data [41] [43]. | Larvae are hatched and synchronized from eggs isolated from feces for assays; adult worms are harvested from infected hosts [41] [43]. |

| Reference Anthelmintic Drugs | Pharmacopeial-standard compounds (e.g., Ivermectin, Moxidectin, Praziquantel) used as positive controls to validate assay performance and for comparative resistance profiling [41] [43]. | Used to generate standard dose-response curves and to calculate Resistance Factors (RF) for field isolates [43]. |

| Drug-Resistant Parasite Strains | Genetically defined or field-derived parasite isolates with confirmed resistance to specific anthelmintic classes, serving as essential controls for resistance diagnosis assays [41] [43]. | Strains like H. contortus Wallangra (multi-resistant) and C. elegans IVR10 (IVM-selected) are used to optimize and validate resistance detection [41] [43]. |

| Myt1-IN-4 | Myt1-IN-4|Potent MYT1 Kinase Inhibitor|RUO | Myt1-IN-4 is a potent MYT1 kinase inhibitor for cancer research. It abrogates the G2/M cell cycle checkpoint. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| SOS1 Ligand intermediate-3 | SOS1 Ligand intermediate-3, MF:C24H27F3N4O2, MW:460.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Next-Generation Sequencing for High-Throughput Antimalarial Resistance Profiling

The emergence and spread of Plasmodium falciparum resistance to antimalarial drugs represents a critical challenge to global malaria elimination efforts. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized antimalarial resistance profiling by enabling high-throughput, cost-effective surveillance of parasite populations. This technical support center provides comprehensive troubleshooting guides and FAQs to assist researchers in implementing NGS-based resistance profiling methodologies within their laboratories, supporting the broader application of high-throughput parasite screening in malaria research and drug development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the key genetic markers for antimalarial drug resistance in P. falciparum?

Multiple genes harbor polymorphisms associated with resistance to various antimalarial drugs. The primary targets include:

- Pfcrt: Mutations associated with chloroquine resistance [48] [49]