Global Trends in Vector-Borne Parasitic Diseases: Burden, Modeling, and Future Outlook for Research and Control

This article synthesizes the latest data on the long-term trends in vector-borne parasitic disease (VBPD) prevalence, burden, and distribution to inform research and drug development.

Global Trends in Vector-Borne Parasitic Diseases: Burden, Modeling, and Future Outlook for Research and Control

Abstract

This article synthesizes the latest data on the long-term trends in vector-borne parasitic disease (VBPD) prevalence, burden, and distribution to inform research and drug development. Drawing on recent Global Burden of Disease studies and scientific literature, it explores the persistent and shifting global landscape of malaria, schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis, Chagas disease, and other parasitic infections. The content delves into advanced methodological approaches, including within-host modeling for antimalarial development, and evaluates the real-world challenges and optimization strategies for translating models into effective vector control. Finally, it provides a comparative analysis of intervention success and failures, offering a validated framework for prioritizing research and public health policy to achieve elimination targets.

The Evolving Global Burden of Vector-Borne Parasitic Diseases

Vector-borne parasitic diseases (VBPDs) constitute a significant and persistent global health challenge, accounting for more than 17% of all infectious diseases and causing substantial morbidity and mortality worldwide [1]. The World Health Organization estimates that vector-borne diseases collectively cause more than 700,000 deaths annually, with parasitic diseases representing a substantial proportion of this burden [1]. These diseases disproportionately affect impoverished populations in tropical and subtropical regions, where environmental conditions favor vector proliferation and socioeconomic factors complicate control efforts [2] [1].

Understanding the current global distribution and impact of dominant vector-borne parasitic pathogens requires comprehensive epidemiological analysis that examines temporal trends, geographic patterns, and demographic disparities. This comparative guide synthesizes the most recent available data (1990-2021) from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 and other contemporary sources to objectively analyze the relative burden of major VBPDs, their geographic concentrations, and temporal trajectories [2] [3]. Such analysis provides critical evidence for guiding research priorities, resource allocation, and public health interventions aimed at reducing the global burden of these diseases.

Global Burden of Vector-Borne Parasitic Diseases: Comparative Analysis

Dominant Pathogens and Relative Contribution to Global Burden

Analysis of data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 reveals significant disparities in the relative burden of different vector-borne parasitic diseases. The table below summarizes the prevalence and mortality metrics for the seven major VBPDs globally.

Table 1: Global Burden of Major Vector-Borne Parasitic Diseases (2021)

| Disease | Global Prevalence (%) | Global Deaths (%) | Dominant Regions | Primary Vector |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malaria | 42.0 | 96.5 | Sub-Saharan Africa | Anopheles mosquito |

| Schistosomiasis | 36.5 | N/A | Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, Latin America | Aquatic snails |

| Lymphatic filariasis | ~12.0 | Minimal | Tropics (Africa, Asia, Americas) | Mosquitoes |

| Leishmaniasis | ~5.0 | <1.0 | Multiple (Brazil, India, East Africa) | Sandflies |

| Chagas disease | ~2.5 | <1.0 | Latin America | Triatomine bugs |

| Onchocerciasis | ~1.5 | Minimal | Sub-Saharan Africa | Blackflies |

| African trypanosomiasis | <0.5 | <1.0 | Sub-Saharan Africa | Tsetse flies |

Malaria emerges as the dominant VBPD, representing approximately 42% of all cases and an overwhelming 96.5% of all deaths among major vector-borne parasitic diseases [2]. The age-standardized prevalence rate for malaria reached 2336.8 per 100,000 population in 2021, with an age-standardized DALY rate of 806.0 per 100,000 population [3]. Schistosomiasis ranks as the second most prevalent VBPD at 36.5% of cases, though it contributes minimally to mortality compared to malaria [2].

The remaining VBPDs—lymphatic filariasis, leishmaniasis, Chagas disease, onchocerciasis, and African trypanosomiasis—collectively account for approximately 20% of the global prevalence burden but contribute minimally to mortality, with the exception of leishmaniasis which shows concerning rising trends [2].

Geographic Hotspots and Regional Distribution

The geographic distribution of VBPDs demonstrates pronounced regional concentration, with the majority of cases concentrated in tropical and subtropical regions, particularly in areas with lower socioeconomic development.

Table 2: Geographic Distribution and Hotspots of Vector-Borne Parasitic Diseases

| Region | Dominant Diseases | Burden Level | Key Contributing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-Saharan Africa | Malaria, Schistosomiasis, African trypanosomiasis, Onchocerciasis | Very High | Low SDI, climate suitability, healthcare access limitations, vector control challenges |

| South Asia | Lymphatic filariasis, Malaria, Schistosomiasis, Leishmaniasis | High | Population density, unplanned urbanization, climate conditions |

| Latin America | Chagas disease, Schistosomiasis, Malaria | Moderate-High | Housing conditions, agricultural practices, forest encroachment |

| Southeast Asia | Lymphatic filariasis, Malaria, Schistosomiasis | Moderate | Urbanization, migration, agricultural practices |

| Middle East & North Africa | Leishmaniasis, Malaria | Moderate-Low | Conflict, displacement, water management issues |

Sub-Saharan Africa bears the highest burden of VBPDs globally, particularly for malaria, which disproportionately affects this region [2]. Low Socio-demographic Index (SDI) regions consistently demonstrate the highest age-standardized prevalence and DALY rates for all VBPDs except Chagas disease, highlighting the strong correlation between disease burden and socioeconomic development [3].

Specific country-level hotspots include Brazil and India, which face significant challenges from multiple VBPDs. Brazil has the highest burden of VBPDs across all Latin America and the Caribbean, with increasing incidence of dengue and other arboviruses [4]. India accounts for nearly 40% of all global lymphatic filariasis infections and approximately 18% of worldwide cases of visceral leishmaniasis [4].

Temporal Trends and Future Projections

Historical Trends (1990-2021)

Analysis of the period from 1990 to 2021 reveals divergent trends among different VBPDs. Overall, the age-standardized prevalence and DALY rates for VBPDs have generally decreased over the past three decades, though with some fluctuations and notable exceptions [3].

Significant declines have been observed for African trypanosomiasis, Chagas disease, lymphatic filariasis, and onchocerciasis, reflecting the success of targeted control programs and mass drug administration campaigns [2]. Lymphatic filariasis prevalence, in particular, has shown substantial reduction and is projected to approach elimination by 2029 based on ARIMA modeling [2].

In contrast, leishmaniasis has demonstrated a concerning rising prevalence, with an estimated annual percentage change (EAPC) of 0.713, indicating a significant upward trend across all burden metrics [2]. Malaria, while still showing an overall decrease in burden, continues to cause an estimated 249 million cases globally and results in more than 608,000 deaths every year, with most deaths occurring in children under 5 years [1].

Future Projections and Emerging Threats

Forecasts based on ARIMA modeling project continued divergent trends for VBPDs through 2036. Lymphatic filariasis prevalence is expected to approach elimination by 2029, representing a significant public health achievement [2]. Conversely, the burden of leishmaniasis is projected to rise across all metrics, suggesting an emerging priority for public health intervention [2].

Climate change is anticipated to significantly influence the future distribution and transmission dynamics of VBPDs. Vectors are expanding their latitude and altitude ranges, and the length of transmission seasons is increasing as global temperatures rise [1] [5]. Models project that approximately half of the global population may be exposed to Aedes aegypti by 2050, and that 60% of the world's population will be at risk of dengue by 2080, though these projections primarily concern viral diseases rather than parasitic ones [4].

The number of months suitable for dengue transmission in India has already increased over the last half-century, with similar patterns expected for other vector-borne diseases in tropical and subtropical regions [4]. Coastal regions may experience year-round transmission of vector-borne diseases in the future, though the highest transmission potential will continue to occur during monsoon seasons in many regions [4].

Methodological Framework for Burden Assessment

The primary data source for comparative analysis of VBPD burden is the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study 2021, which quantifies the burden of 371 diseases and injuries across 204 countries and territories worldwide from 1990 to 2021 [2]. Data on VBPDs can be accessed through the Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx) Results Tool, available at http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool [2].

The detailed search parameters for extracting VBPD data include:

- Metrics: Prevalence, deaths, and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs)

- Measures: Numbers and age-standardized rates

- Causes: Malaria, schistosomiasis, African trypanosomiasis, Chagas disease, lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, leishmaniasis

- Demographic stratification: Age groups, sex, Socio-demographic Index (SDI) levels

- Temporal range: 1990-2021, with annual granularity

The Socio-demographic Index (SDI) serves as a crucial composite metric in the GBD framework, capturing the socioeconomic development level of regions through analysis of under-25 fertility rates, education levels, and per capita income [2]. SDI values range from 0.00 to 1.00 and classify locations into five development levels: low (<0.46), low-middle (0.46-0.60), middle (0.61-0.69), high-middle (0.70-0.81), and high (>0.81) [2].

Analytical Workflow for Burden Assessment

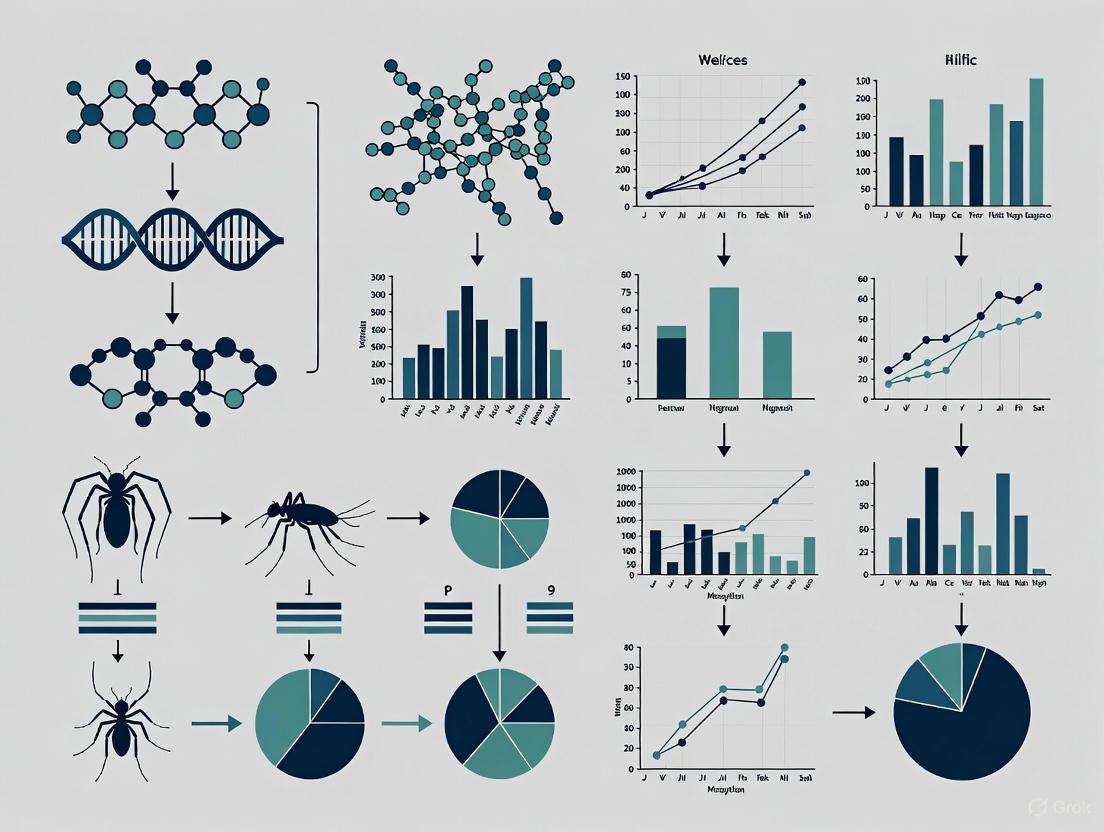

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive methodological workflow for assessing the global burden of vector-borne parasitic diseases:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for VBPD Studies

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Assays | Rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs), PCR reagents, ELISA kits, Microscopy reagents | Case confirmation, prevalence surveys, treatment monitoring | Varying sensitivity/specificity, platform requirements, cold chain needs |

| Molecular Biology Tools | DNA/RNA extraction kits, PCR/RT-PCR reagents, Sequencing platforms, Primers/Probes | Pathogen detection, strain typing, drug resistance monitoring | Extraction efficiency, amplification efficiency, contamination control |

| Vector Monitoring Tools | Insecticide susceptibility test kits, Vector collection traps, Morphological identification keys | Vector distribution mapping, insecticide resistance monitoring, control efficacy assessment | Standardized protocols, species identification accuracy, temporal sampling |

| Data Analysis Resources | GBD data extraction tools, Statistical software (R, Stata), GIS mapping software | Trend analysis, risk mapping, burden estimation, forecasting | Data quality validation, model selection, confounding control |

| Laboratory Infrastructure | Biosafety cabinets, Incubators, Microscopes, Cold storage equipment | Pathogen culture, sample processing, reagent storage | Biosafety compliance, maintenance protocols, temperature monitoring |

Discussion: Implications for Research and Control Strategies

Addressing Disparities in Disease Burden

The analysis reveals persistent and significant disparities in the distribution of VBPD burden, with low-SDI regions bearing the highest burden across nearly all diseases studied [2] [3]. This pattern underscores the interconnectedness of parasitic disease transmission with poverty, healthcare access limitations, and environmental factors [2]. The strong correlation between SDI and disease burden suggests that broader socioeconomic development represents a crucial component of sustainable disease control.

Males exhibit greater DALY burdens than females for most VBPDs, which studies attribute to occupational exposure and gender-based behavioral patterns that may increase contact with vectors [2]. Additionally, pronounced age disparities are evident, with children under five facing high malaria mortality and leishmaniasis DALY peaks, while older adults experience complications from chronic diseases like Chagas and schistosomiasis [2]. These demographic patterns highlight the need for targeted interventions that address specific risk profiles across different population subgroups.

Challenges in Disease Control and Elimination

Vector control remains a critical intervention for VBPDs, yet faces significant challenges including insecticide resistance in key vectors that compromises the effectiveness of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) and indoor residual spraying (IRS) [2]. Furthermore, there is growing evidence of adaptive changes in vector behavior, such as increased outdoor and early-evening biting activity, particularly noted in malaria vectors, which reduces the protective impact of current interventions [2].

Operational challenges include maintaining intervention coverage and access, ensuring effective community engagement, securing adequate funding, and establishing robust surveillance systems, particularly in remote or conflict-affected areas [2]. The complex epidemiology of many VBPDs, with multiple reservoir hosts and complex transmission cycles, further complicates control efforts and necessitates integrated, multidisciplinary approaches.

Research Priorities and Future Directions

Based on the burden analysis and trend projections, key research priorities include:

- Innovative vector control tools to address insecticide resistance and behavioral adaptation

- Enhanced surveillance systems with improved sensitivity and timeliness for outbreak detection

- Novel therapeutic approaches for diseases with limited treatment options or emerging drug resistance

- Climate adaptation strategies that anticipate and respond to changing transmission patterns

- Integrated control approaches that address multiple diseases simultaneously where they co-exist

The projected rise in leishmaniasis burden across all metrics indicates an urgent need for intensified research into its ecology, transmission dynamics, and control strategies [2]. Conversely, the success in reducing lymphatic filariasis toward elimination demonstrates the potential for achieving significant progress against VBPDs with sustained, evidence-based interventions.

The findings presented in this analysis provide a foundation for evidence-based policy development and precision public health efforts aimed at achieving elimination targets and advancing global health equity through reduced burden of vector-borne parasitic diseases.

Vector-borne parasitic diseases (VBPDs) represent a significant global health challenge, accounting for more than 17% of all infectious diseases and causing substantial mortality and disability worldwide [1] [6]. These diseases, including malaria, schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis, Chagas disease, African trypanosomiasis, lymphatic filariasis, and onchocerciasis, impose a disproportionate burden on vulnerable populations in tropical and subtropical regions [1]. The distribution and impact of these diseases are determined by a complex set of demographic, environmental, and social factors, with climate change, global travel, unplanned urbanization, and socioeconomic status significantly influencing transmission dynamics [1] [6]. This analysis examines the correlation between socio-demographic disparities—measured through the Socio-demographic Index (SDI), geographic region, and access to care—and the burden of VBPDs, providing a foundation for evidence-based policy and precision public health efforts to achieve elimination targets and advance global health equity [6].

Global Burden and Distribution of Vector-Borne Parasitic Diseases

Quantitative Assessment of Disease-Specific Burden

The global burden of VBPDs demonstrates striking disparities across diseases, regions, and demographic groups. Analysis of Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2021 data reveals that malaria dominates the VBPD landscape, accounting for approximately 42% of all VBPD cases and a staggering 96.5% of VBPD-related deaths globally [6]. Schistosomiasis ranks second in prevalence, representing 36.5% of VBPD cases, though it causes substantially fewer deaths compared to malaria [6]. While diseases such as African trypanosomiasis, Chagas disease, lymphatic filariasis, and onchocerciasis have shown significant declines in recent decades, leishmaniasis represents an emerging concern with a rising prevalence trend (EAPC = 0.713) [6].

Table 1: Global Burden of Major Vector-Borne Parasitic Diseases (2021)

| Disease | Global Prevalence | Global Deaths | Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) | Trend (1990-2021) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malaria | 42% of VBPD cases | 96.5% of VBPD deaths | 42.3% of VBPD DALYs | Stable prevalence, declining mortality |

| Schistosomiasis | 36.5% of VBPD cases | <0.5% of VBPD deaths | 28.7% of VBPD DALYs | Stable with regional variations |

| Leishmaniasis | 8.2% of VBPD cases | 1.8% of VBPD deaths | 12.5% of VBPD DALYs | Rising prevalence (EAPC = 0.713) |

| Lymphatic Filariasis | 7.1% of VBPD cases | <0.1% of VBPD deaths | 9.3% of VBPD DALYs | Significant decline |

| Chagas Disease | 3.5% of VBPD cases | 0.9% of VBPD deaths | 4.2% of VBPD DALYs | Significant decline |

| Onchocerciasis | 2.3% of VBPD cases | <0.1% of VBPD deaths | 2.7% of VBPD DALYs | Significant decline |

| African Trypanosomiasis | 0.4% of VBPD cases | 0.3% of VBPD deaths | 0.3% of VBPD DALYs | Significant decline |

Regional Disparities in Disease Burden

The burden of VBPDs demonstrates profound geographic concentration, with sub-Saharan Africa experiencing the highest impact. According to WHO data, approximately 95% of all malaria cases and deaths occur in the WHO African Region [7] [8]. This regional disparity extends to other VBPDs, with schistosomiasis, onchocerciasis, and African trypanosomiasis also disproportionately affecting sub-Saharan African populations [6]. In the Americas, malaria transmission persists primarily in the Amazonian territories, with Brazil, Venezuela, and Colombia accounting for 80% of all cases in the region [9]. Indigenous populations in the Americas face disproportionate burdens, representing 31% of all malaria cases and 41% of malaria-related deaths in the region despite constituting a much smaller percentage of the overall population [9].

Socio-Demographic Index (SDI) as a Determinant of Disease Burden

Correlation Between SDI and VBPD Metrics

The Socio-demographic Index (SDI)—a composite measure of income per capita, educational attainment, and fertility rate—shows a strong inverse correlation with VBPD burden [10]. Low-SDI regions bear the highest burden of VBPDs, linked to environmental conditions, socioeconomic constraints, and limited healthcare access [6]. Analysis of GBD 2021 data confirms that regions with lower SDI values consistently demonstrate higher incidence rates, mortality rates, and DALY rates for most VBPDs, with the most pronounced disparities observed in malaria burden [10].

Table 2: Malaria Burden in Children Under 15 by SDI Region (2021)

| SDI Region | Incidence Rate (per 100,000) | Mortality Rate (per 100,000) | Percentage of Global Cases | Percentage of Global Deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low SDI | 24,500 | 68.3 | 68.5% | 72.1% |

| Low-Middle SDI | 8,750 | 24.4 | 22.3% | 19.8% |

| Middle SDI | 1,230 | 3.4 | 5.1% | 4.2% |

| High-Middle SDI | 385 | 1.1 | 3.2% | 3.1% |

| High SDI | 42 | 0.1 | 0.9% | 0.8% |

Age and Gender Disparities in VBPD Burden

Significant disparities in VBPD burden exist across age groups and genders. Children under five face particularly high malaria mortality, while older adults experience complications from chronic conditions such as Chagas disease and schistosomiasis [6]. In 2021, there were 169,052,260 malaria cases and 469,881 deaths among children under 15 worldwide, with incidence and mortality rates highest in children under 5 [10]. Gender disparities are also evident, with males exhibiting greater DALY burdens for most VBPDs than females, attributed primarily to occupational exposure to vectors [6].

Diagram 1: Relationship between SDI and VBPD burden showing pathways of influence. Lower SDI influences disease burden through multiple mechanisms including limited healthcare access, reduced vector control capacity, poorer housing quality, and lower prevention awareness.

Methodological Framework for Burden of Disease Studies

GBD Analytical Approach

The Global Burden of Disease Study employs a systematic, multi-step process to estimate the incidence and mortality of VBPDs [10]. The methodology begins with the collection of data from routine case reports, geolocated infection rate surveys, and assessments of coverage for disease control interventions, complemented by environmental and socio-economic factors [10]. Bayesian spatiotemporal geostatistical models are then applied, tailored to the specific conditions of regions such as sub-Saharan Africa and other endemic areas [10]. These models predict infection rates which are subsequently converted into clinical incidence rates, combined with population data to estimate total cases, and finally translated into comprehensive measures of disease burden, including disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) [10].

Diagram 2: GBD analytical workflow for VBPD burden estimation, showing progression from data collection through modeling to burden calculation.

Statistical Analysis of Trends

The GBD study utilizes Estimated Annual Percentage Change (EAPC) to quantify time trends of disease burden [10]. A regression line is fitted to the natural logarithm of the rates (y = α + βx + ε, where y = ln(rate) and x = calendar year). EAPC is calculated as 100 × (exp(β) - 1), with 95% confidence intervals obtained from the linear regression model [10]. The term "increase" describes trends when the EAPC and its lower boundary of 95% CI are both > 0, while "decrease" is used when the EAPC and its upper boundary of 95% CI are both < 0 [10].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for VBPD Investigations

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Data Repositories | Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Data, Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx) | Epidemiological trend analysis, Comparative burden studies, Resource allocation modeling |

| Diagnostic Tools | Rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs), PCR assays, Microscopy with staining reagents | Case confirmation, Species differentiation, Drug resistance monitoring |

| Vector Control Products | Insecticide-treated nets (ITNs), Long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs), Larvicides | Intervention efficacy studies, Vector resistance monitoring, Transmission dynamics modeling |

| Therapeutic Agents | Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), Chloroquine, Primaquine | Treatment efficacy studies, Drug resistance surveillance, Pharmacokinetic research |

| Geospatial Tools | Climate projections, Vector migration data, Land use maps | Risk mapping, Predictive modeling, Climate change impact studies |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | Species-specific primers, DNA extraction kits, Sequencing platforms | Pathogen genetics, Vector competence studies, Resistance mechanism investigations |

Access to Care as a Determinant of Outcomes

Structural Barriers to Effective Care

Access to appropriate diagnosis and treatment represents a critical determinant of VBPD outcomes, with significant disparities observed across and within countries [9]. Indigenous communities, remote populations, and those in conflict-affected regions face particularly severe barriers to accessing timely and appropriate care [9] [8]. In the Americas, Indigenous peoples represent 31% of all malaria cases and 41% of malaria-related deaths despite constituting a much smaller percentage of the overall population, highlighting profound healthcare access disparities [9]. Scattered Indigenous communities, the high mobility of populations engaged in extractive activities such as gold mining, and security challenges represent significant obstacles to malaria elimination in high-burden areas [9].

Community-Based Interventions as an Equity-Focused Approach

Community engagement has emerged as an essential strategy for addressing access disparities in VBPD control [9]. This includes the active involvement of community leaders and trained health workers to carry out rapid diagnostic tests, provide treatment, and maintain consistent service delivery in hard-to-reach areas [9]. These efforts require strong political will, multi-level governance, regulatory changes, and the establishment of new partnerships, especially with affected communities [9]. The effectiveness of this approach is demonstrated by the certification of four countries in the Americas as malaria-free since 2018: Paraguay, Argentina, El Salvador, and Belize [9].

The burden of vector-borne parasitic diseases demonstrates profound correlations with socio-demographic indicators, geographic factors, and access to care resources. Low-SDI regions, particularly sub-Saharan Africa, experience disproportionate burdens, with malaria accounting for the majority of VBPD-related morbidity and mortality [6] [10]. Children under five, indigenous populations, and other marginalized groups face elevated risks due to biological vulnerability and structural barriers to care [9] [10]. Climate change, insecticide resistance, and operational challenges in remote regions further complicate control efforts [1] [6]. Future progress requires targeted interventions prioritizing vector control in endemic areas, enhanced surveillance for emerging threats like leishmaniasis, gender- and age-specific strategies, and optimized resource allocation in low-SDI regions [6]. As exemplified by the "Malaria Ends With Us: Reinvest, Reimagine, Reignite" campaign, achieving elimination targets necessitates both technical solutions and addressing underlying inequities in access to prevention, diagnosis, and treatment [7].

Vector-borne parasitic diseases (VBPDs) impose a significant and evolving global health burden, affecting hundreds of millions of people annually [6] [1]. Analyzing long-term trends in their prevalence reveals that this burden is not uniformly distributed across populations; instead, it falls disproportionately on specific demographic groups defined by age and sex [6] [3]. Understanding these disparities is fundamental to developing precision public health strategies, optimizing resource allocation, and ultimately achieving disease elimination targets [6]. This review synthesizes current evidence on the age and sex-specific incidence of major VBPDs—including malaria, leishmaniasis, Chagas disease, lymphatic filariasis, and Lyme disease—to identify vulnerable populations from childhood through older adulthood. By integrating global burden estimates, analytical models of transmission dynamics, and findings from regional studies, we provide a comprehensive comparison of demographic risk patterns and the methodologies used to uncover them.

Global Burden and Demographic Disparities

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2021 study provides critical quantitative evidence of the profound demographic disparities in VBPD incidence and associated health impacts. The data reveal distinct patterns across different diseases and metrics, such as disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), which combine years of life lost due to premature mortality and years lived with disability [6] [3].

Table 1: Age-Standardized DALY Rates for Major Vector-Borne Parasitic Diseases (2021)

| Disease | Global Age-Standardized DALY Rate (per 100,000) | Population with Highest DALY Burden | Key Sex-Based Disparity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malaria | 806.0 | Children under 5 years (High mortality) [6] | Males exhibit greater DALY burdens than females [6] |

| Leishmaniasis | Data Not Specified | Children under 5 (DALY peak) [6] | Data Not Specified |

| Chagas Disease | Data Not Specified | Older adults (Complications) [6] | Data Not Specified |

| Lymphatic Filariasis | Data Not Specified | Data Not Specified | Data Not Specified |

| Onchocerciasis | Data Not Specified | Data Not Specified | Data Not Specified |

Table 2: Age-Specific Vulnerability to Common Vector-Borne Diseases

| Age Group | Vulnerable Diseases | Nature of Vulnerability |

|---|---|---|

| Children (<5 years) | Malaria, Leishmaniasis [6] | High mortality (malaria); Peak DALY rates (leishmaniasis) [6] |

| Children (5-9 years) | Lyme Disease [11] | Among the highest incidence rates [11] |

| Adults (20-50 years) | Malaria, Lyme Disease [11] [12] | Occupational exposure (e.g., farming, forestry) [6] [11] |

| Older Adults (>50 years) | Chagas Disease, Schistosomiasis, Lyme Disease [6] [11] | Complications from chronic infections; Highest incidence rates (Lyme) [6] [11] |

Sex-based differences are equally significant. Globally, males exhibit greater DALY burdens for VBPDs than females, a pattern largely attributed to higher occupational exposure through activities such as farming, forestry, and mining that increase contact with vectors [6]. This trend is observable in diseases like malaria and Lyme disease, where case data and behavioral studies indicate that males report more activity in wooded and tall grass areas, key habitats for disease vectors [6] [11].

Analytical Approaches for Identifying Vulnerable Groups

Methodologies in Burden Estimation and Cluster Analysis

Identifying vulnerable populations relies on robust analytical techniques. The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study employs a comprehensive framework to estimate the incidence, prevalence, and DALYs for 371 diseases and injuries across 204 countries and territories [6] [3]. The process involves the following key steps:

- Data Collation: Data are assembled from a wide array of sources, including scientific literature, hospital records, surveillance systems, and survey reports [6].

- Modeling and Estimation: Statistical models, primarily Bayesian meta-regression tools (DisMod-MR 2.1), are used to estimate disease metrics by location, year, age, and sex, accounting for data incompleteness and variability in quality [6] [3].

- Socio-demographic Index (SDI): The SDI, a composite measure of income per capita, average years of schooling, and total fertility rate, is used to analyze disease burden trends across different development levels [6].

Beyond broad burden estimation, partition clustering algorithms like K-prototypes offer a powerful, data-driven method to identify vulnerable subpopulations characterized by multiple attributes simultaneously. A study in Tengchong County, China, successfully used this method to cluster malaria cases based on sex, age, and occupation [12]. The workflow for this approach is outlined below:

This analysis revealed that the most vulnerable group for malaria were males aged 16-45 years working as farmers or migrant laborers, providing a precise target for intervention [12].

Theoretical Modeling of Sex-Biased Prevalence

Theoretical models provide a framework for understanding the mechanisms behind observed sex biases in infection prevalence. Kermack-McKendrick-type deterministic models analyze transmission dynamics in a two-sex population, incorporating biases in heterosexual transmission probability and additional transmission routes [13].

- Model 1: Heterosexual Transmission Only: The final attack ratio (the fraction of each sex infected) is biased in the same direction as gender-specific susceptibilities. The ratio of attack ratios depends solely on the ratio of gender-specific susceptibilities and the basic reproduction number (R₀) [13].

- Model 2: Heterosexual and Direct Transmission: When non-sexual, direct transmission is added, the qualitative results are similar, but the relative weight of direct versus heterosexual transmission becomes a key parameter determining the final attack ratio. If direct transmission accounts for most events, the sex ratio of final attack ratios is generally muted [13].

- Model 3: Vector-Mediated Transmission: Numerical simulations for this model show that the results on final attack ratios are quite similar to the model with direct transmission. However, transient patterns can differ, with new cases initially occurring more often in the more susceptible sex, while later depletion of susceptibles can bias the ratio in the opposite direction [13].

These models highlight that even a small bias in susceptibility or exposure can, through the process of community transmission, lead to a measurable disparity in overall prevalence between sexes.

Disease-Specific Evidence and Co-Infections

Malaria and Dengue Co-Infections

In regions where multiple VBPDs are endemic, co-infections present a complex clinical and public health challenge. A hospital-based study in Kassala, eastern Sudan, investigated the prevalence of malaria and dengue co-infections among febrile patients [14].

Table 3: Key Reagents and Assays for Diagnosing Malaria and Dengue Co-infections

| Research Reagent/Assay | Function/Application in Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Giemsa Stain | Stains thin and thick blood smears for microscopic visualization and identification of Plasmodium parasites [14]. |

| Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) | Confirms malaria parasite species (P. falciparum, P. vivax) from extracted DNA using outer and nested PCR protocols [14]. |

| Guanidine Chloride Protocol | A method for extracting DNA from blood samples for subsequent PCR analysis [14]. |

| Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) IgM | A serological test that detects Immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies against the dengue virus, indicating a recent infection [14]. |

The study found a co-infection prevalence of 6.6% (26/395) [14]. Patients with co-infections were eight times more likely to have fatigue and twice as likely to suffer from joint and muscle pain compared to those with mono-infections, indicating more severe clinical manifestations [14]. From a demographic perspective, younger individuals were more vulnerable to co-infection, while elder patients (41-60 years) had a significantly lower rate [14]. This underscores the need for integrated diagnostic protocols in febrile illness management in endemic zones.

The evidence consistently demonstrates that the incidence of vector-borne parasitic diseases is strongly shaped by age and sex. Key vulnerable populations include young children, who suffer high mortality from malaria and leishmaniasis; working-age adults, particularly males in specific occupations with high vector exposure; and older adults, who bear the burden of chronic complications from diseases like Chagas and schistosomiasis [6] [11] [12]. The identification of these groups has been enabled by methodologies ranging from global burden estimation and cluster analysis to theoretical transmission modeling [6] [13] [12]. Moving forward, addressing the persistent challenge of VBPDs requires a precision public health approach. Targeted interventions must be informed by continuous demographic surveillance and include vector control strategies, health communication, and resource allocation tailored to the specific vulnerabilities of these distinct sub-populations. This is essential for reducing global health disparities and achieving disease elimination goals.

Vector-borne parasitic diseases (VBPDs) represent a significant global health challenge, particularly in resource-limited settings. These diseases, transmitted through insects and other arthropods, disproportionately affect impoverished communities and impose substantial health and economic burdens [3] [6]. This analysis examines the epidemiological transitions in major VBPDs over three decades (1990-2021), identifying diseases with remarkable declines and those exhibiting concerning resurgences. Understanding these long-term trends provides critical insights for researchers, public health policymakers, and drug development professionals working toward disease elimination targets. The complex interplay of environmental factors, control interventions, and socioeconomic determinants has created divergent pathways for different parasitic diseases, with some approaching elimination while others continue to challenge global health systems [15].

Methodological Framework for Trend Analysis

This analysis utilizes data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study 2021, which provides comprehensive estimates for 371 diseases and injuries across 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2021 [3] [6]. The GBD database incorporates data from mortality registries, incidence reports, surveys, and systematic literature reviews, employing standardized methodologies to ensure comparability across regions and over time.

The study focused on seven major vector-borne parasitic diseases: malaria, lymphatic filariasis, leishmaniasis, African trypanosomiasis, Chagas disease, onchocerciasis, and schistosomiasis [6] [2]. Case definitions followed International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes, with regular updates to incorporate new diagnostic criteria throughout the study period.

Analytical Approach and Metrics

The primary metrics for assessing disease burden included:

- Age-standardized prevalence rate (ASPR): Cases per 100,000 population, adjusted for age distribution

- Age-standardized mortality rate (ASMR): Deaths per 100,000 population, age-adjusted

- Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs): Years of life lost due to premature mortality and years lived with disability

- Age-standardized DALY rate: DALYs per 100,000 population, age-adjusted

Temporal trends were quantified using Estimated Annual Percentage Change (EAPC) and Average Annual Percentage Change (AAPC) calculated through joinpoint regression analysis, which identifies inflection points in trends over time [16] [17]. The Socio-demographic Index (SDI), a composite measure of income, education, and fertility, was used to analyze relationships between development levels and disease burden [3] [6].

Table 1: Key Metrics for Assessing Disease Burden Trends

| Metric | Definition | Application in Trend Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Age-Standardized Prevalence Rate (ASPR) | Number of existing cases per 100,000 population, adjusted to a standard age distribution | Tracks changes in disease occurrence independent of demographic shifts |

| Age-Standardized Mortality Rate (ASMR) | Number of deaths per 100,000 population, adjusted to a standard age distribution | Monitors changes in disease-specific fatalities |

| Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) | Sum of years of life lost due to premature mortality and years lived with disability | Quantifies overall disease burden combining fatal and non-fatal outcomes |

| Estimated Annual Percentage Change (EAPC) | Average rate of change per year in age-standardized rates over a specific period | Measures pace of increase or decrease in disease burden metrics |

Documenting Significant Declines: Success Stories in Disease Control

Lymphatic Filariasis, Onchocerciasis, and African Trypanosomiasis

Substantial progress has been achieved against several VBPDs between 1990 and 2021. Lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, and African trypanosomiasis exhibited significant declines in age-standardized prevalence and DALY rates throughout the study period [6]. These successes are largely attributable to coordinated global control programs emphasizing preventive chemotherapy, vector control, and mass drug administration campaigns [2]. Projection models suggest that lymphatic filariasis is approaching elimination targets, potentially reaching this milestone by 2029 if current trends continue [6] [2].

The decline of African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) has been particularly remarkable, with both incidence and distribution decreasing dramatically over the study period [6] [2]. This success stems from strengthened surveillance systems, improved diagnostic capabilities, and vector control activities targeting tsetse fly populations in endemic regions of sub-Saharan Africa.

Visceral Leishmaniasis: A Complex Decline

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) demonstrated a declining trend in age-standardized incidence, prevalence, mortality, and DALY rates from 1990 to 2021 [16] [17]. The average annual percentage change for ASPR was -0.06, while ASPR showed a more substantial decline of -0.25 [16]. This progress is noteworthy given that VL remains the most severe form of leishmaniasis, with a historical mortality rate exceeding 95% if left untreated [16].

However, VL epidemiology reveals important disparities, with the highest mortality burden concentrated in children under 5 years [16] [17]. The disease remains a critical concern in Latin America, the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia, requiring ongoing surveillance and targeted interventions despite the overall declining trend.

Table 2: Diseases with Significant Declines (1990-2021)

| Disease | Key Trend Metrics | Primary Drivers of Decline | Regional Patterns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphatic Filariasis | Steady decline in ASPR and DALY rates | Mass drug administration, vector control | Approaching elimination; previously endemic in tropics |

| Onchocerciasis | Substantial reduction in ASPR and DALY rates | Community-directed treatment with ivermectin | Persistent foci in sub-Saharan Africa despite overall decline |

| African Trypanosomiasis | Dramatic decrease in incidence and distribution | Enhanced surveillance, vector control, improved diagnostics | Concentrated decline in sub-Saharan Africa |

| Visceral Leishmaniasis | ASPR AAPC = -0.06; ASPR AAPC = -0.25 | Improved case detection and treatment | Disproportionate burden in children under 5; persistent in South Asia, East Africa, Latin America |

Alarming Resurgences and Persistent Challenges

The Leishmaniasis Paradox

Despite progress against visceral leishmaniasis, the broader category of leishmaniasis demonstrates a concerning trend. Between 1990 and 2021, leishmaniasis overall showed a rising prevalence, with an EAPC of 0.713 [6] [2]. This increase is projected to continue, with models forecasting a growing burden across all metrics through 2036 [6].

The resurgence of leishmaniasis has been linked to several factors, including environmental changes that expand sandfly habitats, urbanization creating new transmission foci, and human migration introducing the parasite to new populations [16] [15]. The complex epidemiology of leishmaniasis, with multiple reservoir hosts and sandfly vector species, presents ongoing challenges for control efforts.

Malaria: Persistent Dominance in the VBPD Landscape

Malaria continues to dominate the landscape of vector-borne parasitic diseases, accounting for approximately 42% of all VBPD cases and a staggering 96.5% of VBPD-related deaths [6] [2]. While overall age-standardized rates have declined, the absolute burden remains exceptionally high, with an ASPR of 2336.8 per 100,000 population and an age-standardized DALY rate of 806.0 per 100,000 population in 2021 [3].

The disease disproportionately affects sub-Saharan Africa, where environmental conditions favor Anopheles mosquito vectors and socioeconomic barriers limit access to prevention and treatment [3] [6]. Children under five years bear the highest mortality burden, highlighting the need for continued focus on this vulnerable population [3].

Schistosomiasis: High Prevalence Despite Control Efforts

Schistosomiasis ranks as the second most prevalent VBPD, representing approximately 36.5% of all cases [6] [2]. The disease affects nearly 1 billion people globally who remain at risk of infection [6]. This persistent high prevalence occurs despite ongoing control efforts, reflecting the challenges of controlling a disease with complex transmission dynamics involving freshwater snails and human water contact patterns.

The age profile of schistosomiasis has shifted, with increasing recognition of long-term complications manifesting in older adults who experienced chronic exposure earlier in life [6]. This pattern underscores the importance of considering both incidence and prevalent complications in burden assessments.

Diagram: Interconnected Factors Driving Disease Resurgence and Persistence. Multiple environmental, vector, human, and systemic factors contribute to the resurgence of diseases like leishmaniasis and the persistent high burden of malaria and schistosomiasis.

Disparities in Disease Burden: Socioeconomic, Geographic and Demographic Dimensions

Socioeconomic Determinants

The burden of VBPDs demonstrates a strong inverse relationship with socioeconomic development. Low-SDI regions bear the highest burden, with ASPR and DALY rates showing significant negative correlations with SDI for most diseases [3] [6]. This pattern reflects the multifaceted connections between poverty and disease vulnerability, including limited access to healthcare, inadequate housing that increases vector exposure, and limited resources for vector control programs [15].

The exception to this pattern is Chagas disease, which shows a distinct epidemiological profile compared to other VBPDs, with its highest burden not exclusively concentrated in the lowest SDI regions [3]. This anomaly reflects the complex transmission dynamics of Chagas disease, which involves both vector-borne transmission and non-vector routes including congenital transmission and blood transfusion.

Geographic Hotspots

VBPDs display distinctive global distributions with clearly identified hotspots:

- Sub-Saharan Africa: Bears the highest burden of malaria, lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, and African trypanosomiasis [3] [6]

- South Asia and East Africa: Concentration of visceral leishmaniasis cases [16] [17]

- Latin America: Primary burden for Chagas disease, with ongoing transmission foci [3] [2]

- Africa, Asia, and Latin America: Schistosomiasis endemic regions [6] [2]

These geographic patterns reflect the ecological requirements of specific vector species, historical transmission patterns, and varying capacities of regional health systems to implement control measures.

Age and Sex Disparities

VBPD burden demonstrates distinct patterns across age groups and between sexes:

- Children under five years: Experience disproportionately high malaria mortality and peak leishmaniasis DALY rates [6] [16]

- Older adults: Face complications from chronic infections including Chagas disease cardiomyopathy and schistosomiasis-related morbidity [6]

- Males: Exhibit greater DALY burdens than females, attributed to occupational exposure that increases vector contact [6]

These disparities highlight the need for targeted interventions that address the specific vulnerability profiles of different population subgroups.

Table 3: Disparities in Vector-Borne Parasitic Disease Burden

| Dimension of Disparity | Pattern | Representative Example |

|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic | Strong inverse correlation between SDI and disease burden | Low-SDI regions have highest ASPR for all VBPDs except Chagas disease [3] |

| Geographic | Distinct regional concentrations with clear hotspots | Malaria disproportionately affects sub-Saharan Africa [6] |

| Age | Higher mortality in young children; chronic complications in older adults | Children under 5 have highest ASMR for visceral leishmaniasis [16] |

| Sex | Males generally experience higher DALY burdens | Occupational exposure increases vector contact for males [6] |

Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Laboratory Reagents for VBPD Research

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Vector-Borne Parasitic Disease Studies

| Research Reagent | Primary Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| GBD 2021 Dataset | Epidemiological trend analysis | Provides standardized, comparable data across diseases, regions, and time periods [3] [6] |

| Socio-demographic Index (SDI) | Analysis of socioeconomic determinants | Composite measure of development level used to examine relationships between socioeconomic factors and disease burden [3] [6] |

| Joinpoint Regression Analysis | Identification of trend inflection points | Statistical method for identifying significant changes in temporal trends [16] [17] |

| ARIMA Modeling | Forecasting future disease burden | Statistical projection of trends based on historical patterns [6] [2] |

Analytical Protocols for Trend Analysis

The research cited in this analysis employed sophisticated methodological approaches that can be adapted for ongoing surveillance and trend monitoring:

GBD Data Extraction Protocol:

- Access the Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx) results tool

- Define search parameters: measures (prevalence, deaths, DALYs), metrics (number, rate), causes (specific VBPDs)

- Extract data stratified by age, sex, region, and SDI level

- Apply statistical modeling to address data gaps and ensure comparability [3] [6]

Temporal Trend Analysis Protocol:

- Calculate age-standardized rates using a standard population distribution

- Perform joinpoint regression to identify significant trend change points

- Compute Estimated Annual Percentage Change (EAPC) and Average Annual Percentage Change (AAPC)

- Conduct correlation analysis between disease metrics and SDI [3] [16] [17]

Diagram: Analytical Framework for VBPD Trend Analysis. This workflow outlines the key steps in processing GBD data to generate standardized rates, trend metrics, and future projections for vector-borne parasitic diseases.

The period from 1990 to 2021 witnessed both remarkable progress and persistent challenges in the control of vector-borne parasitic diseases. The significant declines observed for lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, African trypanosomiasis, and visceral leishmaniasis demonstrate the effectiveness of coordinated control programs when sustained over decades. However, the resurgence of leishmaniasis and the ongoing high burden of malaria and schistosomiasis highlight the fragility of these gains and the need for continued investment.

Future control strategies must address the multifactorial drivers of disease transmission, including climate change, insecticide and drug resistance, and urbanization patterns that create new transmission foci [15]. The strong socioeconomic gradients in disease burden underscore that VBPDs are not merely biological phenomena but manifestations of structural inequalities that require addressing social determinants alongside biomedical interventions.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these trends highlight several priorities: (1) developing new tools for diseases showing resurgent trends; (2) strengthening surveillance systems to detect epidemiological transitions early; and (3) creating adaptive control strategies that can respond to changing transmission patterns. As the global health community works toward the 2030 elimination targets for neglected tropical diseases, this analysis provides both encouragement from past successes and urgency for addressing ongoing challenges.

Vector-borne parasitic diseases (VBPDs) continue to represent a significant global health challenge, accounting for more than 17% of all infectious diseases and imposing a substantial burden on healthcare systems worldwide [6]. The complex epidemiology of these diseases is influenced by an array of factors including environmental conditions, socioeconomic development, vector control interventions, and climate change patterns. Current research indicates divergent future pathways for various VBPDs, with some diseases progressing toward elimination while others demonstrate concerning expansion trends. Understanding these trajectories is crucial for researchers, public health officials, and drug development professionals working to allocate resources effectively and develop targeted interventions.

The period to 2036 represents a critical timeframe for achieving the World Health Organization's elimination targets for several neglected tropical diseases, while simultaneously addressing the rising prevalence of others. This analysis examines the projected paths for major vector-borne parasitic diseases—malaria, schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis, Chagas disease, human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), lymphatic filariasis, and onchocerciasis—based on current surveillance data, modeling studies, and intervention scenarios. By comparing forecasting methodologies and results across different diseases and geographical contexts, this guide provides a comprehensive overview of the expected evolution of the VBPD landscape over the next decade.

Comparative Projections of Major Vector-Borne Parasitic Diseases to 2036

Table 1: Global Burden and Projected Trends for Vector-Borne Parasitic Diseases (1990-2036)

| Disease | Current/Recent Burden | Projected Trend to 2036 | Key Influencing Factors | Regional Variations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malaria | 42% of VBPD cases, 96.5% of VBPD deaths (2021) [6] | Variable: 25-30% increase by 2050 in Uganda without interventions; highly dependent on control measures [18] | Temperature (25-27°C optimal), rainfall, intervention coverage (LLINs, IRS), drug resistance [18] | Sub-Saharan Africa bears disproportionate burden; highland areas may see emergence [19] [18] |

| Schistosomiasis | 36.5% prevalence among VBPDs, ranked 2nd [6] | Not specifically projected in sources | Water contact patterns, snail intermediate host distribution, treatment coverage | Concentrated in Asia, Africa, Latin America [6] |

| Leishmaniasis | Rising prevalence (EAPC = 0.713) [6] | Projected to rise across all metrics by 2036 [6] | Sandfly distribution, reservoir hosts, climate change, urbanization | Visceral leishmaniasis in anthroponotic regions; cutaneous forms vary by region [20] |

| Chagas Disease | Significant burden in Latin America [6] | Significant decline by 2036 [6] | Vector control, housing improvement, blood screening | Primarily Latin America with global spread through migration [6] |

| Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT) | <1000 annual cases since 2018 [21] | Continued decline toward elimination [6] [21] | Active case detection and treatment, vector control | Foci persist in DRC and other endemic countries; elimination validated in 8 countries [21] |

| Lymphatic Filariasis | Second major contributor to global disability [6] | Nears elimination by 2029 [6] | Mass drug administration, vector control | 39 countries remain at risk; mapping to elimination targets [6] |

| Onchocerciasis | Concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa [6] | Significant decline by 2036 [6] | Mass drug administration, vector control | Focal persistence in endemic regions of Africa [6] |

Table 2: Projected Impact of Vector Control Interventions on Malaria Burden in Uganda (2050s)

| Intervention Scenario | Projected Reduction in Annual Malaria Cases | Additional Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| No Intervention | 25-30% increase by 2050s [18] | Upward trend with large variability in predictions |

| LLINs Alone | 35.1% reduction [18] | Baseline protection that may be compromised by insecticide resistance |

| IRS Alone | 63.8% reduction [18] | Higher protection than LLINs alone but more resource-intensive |

| Combination (IRS + LLINs) | 76.5% reduction [18] | Most effective strategy; potential additive or synergistic effects |

Methodological Approaches in Forecasting Disease Trajectories

Global Burden of Disease Statistical Modeling

The comprehensive analysis of global VBPD trends employs data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2021 study, which quantifies the burden of 371 diseases and injuries across 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2021 [6]. The modeling approach incorporates:

- Data Integration: Prevalence, deaths, and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) are extracted from the GBD database, categorized by geographic region, sex, age group, and Socio-demographic Index (SDI) [6].

- Trend Analysis: Age-standardized rates (ASRs) and estimated annual percentage changes (EAPC) are calculated to analyze trends over time.

- Projection Methodology: ARIMA (AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average) modeling is applied to project future trends to 2036, accounting for historical patterns and their persistence [6].

- Stratified Analysis: Disparities are analyzed across SDI levels (low, middle, and high), regions, sexes, and age groups to identify populations at highest risk.

This approach successfully identified the divergent paths of VBPDs, with lymphatic filariasis nearing elimination by 2029 while leishmaniasis shows rising prevalence [6].

Climate-Informed Predictive Modeling for Malaria

Recent studies have enhanced traditional disease modeling by incorporating climatic variables to predict malaria risk under different climate change scenarios:

- Environmental Variables: Models integrate rainfall, humidity, temperature, vegetation indices (EVI), and elevation data [18] [22].

- Intervention Components: The impact of vector control interventions (LLINs and IRS) is quantified and included in projections [18].

- Climate Scenarios: Models utilize Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP4.5 and RCP8.5) from Regional Climate Models to project future climate conditions and their impact on transmission [18].

- Statistical Approach: Negative binomial regression models account for the non-linear relationship between environmental factors and malaria incidence, applied to weekly malaria surveillance data from multiple sites [18].

In Uganda, this approach predicted an increase of 25-30% in malaria cases by the 2050s in the absence of interventions, but also demonstrated that combination vector control could reduce cases by 76.5% [18].

High-Resolution Spatial-Temporal Modeling

Advanced modeling techniques now enable predictions with unprecedented spatial and temporal resolution:

- Multi-Criteria Evaluation (MCE): This technique combines multiple environmental factors using weighted criteria to predict malaria risk [22].

- Geospatial Integration: Satellite-derived data on elevation, land surface temperature, vegetation indices, and population density are incorporated at high resolution (2km) [22].

- Temporal Precision: Models generate daily predictions based on climate data from prior periods (1-16 weeks), accounting for mosquito development cycles [22].

- Validation: Predictions are compared with actual malaria case numbers from health zones to validate model accuracy [22].

Implemented in South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo, this approach successfully identified high-risk regions by considering the 2km flight range of Anopheles mosquitoes and their 2-4 week lifespan [22].

Visualization of Forecasting Approaches

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Vector-Borne Disease Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Primary Application | Research Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| IDEXX SNAP 4Dx Plus Test | Serological surveillance [23] | Simultaneous detection of heartworm antigen and antibodies to tick-borne pathogens (B. burgdorferi, Ehrlichia spp., Anaplasma spp.) | Canine sentinel studies to map pathogen distributions and assess human risk [23] |

| Card Agglutination Test for Trypanosomiasis (CATT) | HAT field screening [21] | Serological screening for T.b. gambiense antibodies in mass screening programs | Initial rapid assessment in HAT elimination campaigns [21] |

| HAT Sero-K-SeT | HAT diagnosis [21] | Rapid diagnostic test for serodiagnosis of sleeping sickness caused by T.b. gambiense | Case detection and confirmation in resource-limited settings [21] |

| SHERLOCK4HAT CRISPR-based Toolkit | HAT diagnosis [21] | Molecular detection of trypanosome DNA with high sensitivity | Confirmation of infection and monitoring treatment efficacy [21] |

| ERA5 Climate Data | Environmental disease modeling [22] | Hourly climate reanalysis data providing historical and current weather variables | Input for climate-informed disease risk models [22] |

| SRTM Elevation Data | Geospatial analysis [22] | High-resolution digital elevation models from NASA's Shuttle Radar Topography Mission | Terrain analysis in vector habitat modeling [22] |

| Sentinel-2 Satellite Imagery | Land cover classification [22] | Multispectral imaging at high spatial resolution | Vegetation and water body identification for breeding site mapping [22] |

The divergent projections for vector-borne parasitic diseases to 2036 highlight both remarkable progress in disease control and persistent challenges. The successful pathways toward elimination of lymphatic filariasis and human African trypanosomiasis demonstrate the effectiveness of targeted interventions, sustained surveillance, and international collaboration [6] [21]. Conversely, the projected rise in leishmaniasis prevalence and the climate-sensitive nature of malaria transmission underscore the need for continued research investment and adaptive control strategies.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these projections emphasize the importance of:

Targeted Product Development: Vaccines for leishmaniasis represent a significant unmet need, with projected demand ranging from 300-830 million doses for visceral leishmaniasis and 557-1400 million doses for cutaneous leishmaniasis over a 10-year introduction period [20].

Intervention Optimization: The superior protection offered by combination vector control (76.5% reduction) compared to single interventions supports integrated approaches [18].

Adaptive Surveillance Systems: High-resolution spatial-temporal modeling enables precision public health responses, particularly important in the context of changing climate conditions [22].

Regional Customization: The substantial geographic variation in disease trends necessitates tailored approaches rather than one-size-fits-all solutions.

As the 2030 elimination targets approach, these forecasts provide both encouragement and caution—demonstrating that elimination is achievable for some VBPDs, while others will require renewed focus and innovation in the coming decade.

Advanced Modeling of Parasite-Host Dynamics in Preclinical and Clinical Development

Mathematical modeling of within-host infection dynamics represents a critical tool in the fight against vector-borne parasitic diseases, particularly malaria. These computational frameworks integrate our understanding of complex biological systems, from the microscopic interaction between parasites and red blood cells (RBCs) to the macroscopic effects of antimalarial drugs [24] [25]. The primary strength of within-host models lies in their ability to quantify and simulate the dynamics of infection and treatment response in a controlled, ethical manner, providing insights that would be challenging or unethical to obtain through human trials alone [24]. By capturing the essential components of parasite biology and host physiology, these models serve as translational bridges across the drug development pipeline, from preclinical murine studies to human clinical trials [24] [25]. This guide compares the predominant within-host modeling frameworks, their structural components, applications, and limitations to assist researchers in selecting appropriate methodologies for specific research questions in antimalarial drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Modeling Frameworks

Within-host models vary significantly in their complexity, biological fidelity, and specific applications. The table below provides a systematic comparison of the primary frameworks identified in current literature.

Table 1: Comparison of Within-Host Modeling Frameworks for Malaria

| Model Category | Key Biological Components | Primary Applications | Notable Findings | Limitations/Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Parasite Growth Models (ODE-based) [25] | RBC dynamics (constant production/decay), merozoites, infected RBCs with age-structured compartments. | Initial assessment of crude drug efficacy; foundation for more complex models. | Serves as a base structure; assumes constant RBC availability and synchronous parasite growth. | Does not account for resource limitation, immune responses, or changing parasite traits. |

| Enhanced Host-Parasite Interaction Models [25] | Includes features like bystander RBC death, compensatory erythropoiesis, parasite life cycle lengthening, and reticulocyte preference. | Investigating how host-specific factors (e.g., anemia, immune reactions) influence infection dynamics and drug efficacy. | In P. berghei infections, resource limitation and parasite maturation are key drivers of dynamics and drug response [25]. | Increased complexity requires more parameters; may be difficult to fit with limited data. |

| Multi-Scale Coupled Models [26] [27] [28] | Combines within-host dynamics (RBCs, immunity, multiple strains) with between-host transmission dynamics in human and mosquito populations. | Studying the evolution and spread of drug resistance; evaluating population-level impact of treatment strategies. | Within-host competition can delay the establishment of drug resistance in high-transmission settings [27]. | Computationally intensive; requires parameterization at multiple biological scales. |

| Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic (PKPD) Models [24] | Integrates drug concentration (PK) with drug effect on parasite clearance (PD), often built upon a parasite growth model. | Predicting efficacious human dosing regimens from murine studies; optimizing drug candidate selection. | Maximum parasite clearance rates vary across systems: ~0.2/h (P. berghei-mouse) vs. ~0.12-0.18/h (P. falciparum-human) [24]. | PK parameters are often host-specific; translation between species requires careful scaling. |

| Ensemble Modeling Approaches [25] | A workflow employing multiple model structures (e.g., models with different RBC handling or parasite behaviors) simultaneously. | Robustly assessing drug efficacy across labs and systems; highlighting critical knowledge gaps and uncertainties. | Identified that experimental constraints primarily drive P. falciparum dynamics in SCID mice, unlike the biological drivers in P. berghei models [25]. | Provides a range of outcomes rather than a single prediction; interpretation can be more complex. |

Experimental Protocols for Model Parameterization and Validation

The development and validation of robust within-host models rely on data generated from controlled experimental systems. The following protocols outline key methodologies cited in the literature.

Preclinical Murine Infection Models

Objective: To generate quantitative data on parasite growth kinetics and drug response for parameterizing within-host models [24] [25].

Murine Systems:

- P. berghei-NMRI Model: Normal (immunocompetent) NMRI mice are infected with the rodent-adapted Plasmodium berghei ANKA strain. This model produces a severe, rapidly progressing infection [25].

- P. falciparum-SCID Model: Immunodeficient NOD

scid IL-2Rγ-/-(SCID) mice, engrafted with human erythrocytes, are infected with the human parasite Plasmodium falciparum (e.g., strain 3D7). This system supports longer-term studies of the human pathogen [24] [25].

Procedure:

- Inoculation: Mice are inoculated intravenously with a known quantity of infected RBCs (iRBCs)—typically >1x10^7 parasites for mice [24].

- Monitoring: Parasitemia (percentage of iRBCs) is monitored daily via blood smears.

- Drug Administration: At a predetermined parasitemia (e.g., 72 hours post-infection), mice are treated with single or multiple doses of the investigational antimalarial.

- Data Collection: Parasitemia and hematocrit are tracked frequently post-treatment until recrudescence (parasite recurrence) or clearance. Data on survival and cure rates are also recorded [24] [25].

Key Parameters for Modeling: Inoculum size, parasitemia over time, hematocrit dynamics, drug dosage and regimen, and cure/survival outcomes [25].

Volunteer Infection Studies (VIS) / Controlled Human Malaria Infection (CHMI)

Objective: To obtain high-quality human data on parasite dynamics and drug efficacy for translational model validation [24].

Procedure:

- Ethical Oversight: Studies are conducted under strict ethical guidelines with informed consent from malaria-naive, healthy adult volunteers.

- Infection: Volunteers are infected via the bite of infected mosquitoes or by intravenous injection of P. falciparum sporozoites or infected RBCs.

- Early Treatment: Parasitemia is monitored with high sensitivity using quantitative PCR. Treatment with the investigational drug begins at a very low parasite density (e.g., ~1,000 - 10,000 parasites/mL) to prevent symptom development [24].

- Intensive Sampling: Frequent blood sampling is performed to measure parasite clearance kinetics and, concurrently, drug concentration in plasma (for PK modeling).

Key Parameters for Modeling: Baseline parasite growth rate, parasite reduction ratio (PRR) over 48 hours, parasite clearance rate, and drug concentration-time profiles [24].

Visualizing a Multi-Scale Within-Host Modeling Framework

The DOT language script below generates a diagram illustrating the integration of key components within a multi-scale modeling framework.

Diagram 1: Integrated Multi-Scale Malaria Modeling Framework. This diagram illustrates the core components of a within-host model, including the parasite life cycle within red blood cells (RBCs), the action of drugs and immune responses, and the coupling to between-host transmission dynamics via gametocyte production.

Successful implementation and parameterization of within-host models depend on specific experimental and computational resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Within-Host Modeling

| Category | Item/Solution | Function in Modeling Context |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Systems | Plasmodium berghei ANKA (rodent parasite) & NMRI mice | Provides a rapid, standardized system for initial crude efficacy screening of compounds and for studying aggressive infection dynamics [25]. |

| Plasmodium falciparum (human parasite) & SCID mice engrafted with human RBCs | Allows for in vivo testing of drug efficacy against the human pathogen, providing a critical translational step before human trials [24] [25]. | |

| Data Generation | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays | Enables highly sensitive, quantitative tracking of parasite density in blood, essential for fitting dynamic models, especially in human VIS where parasitemia is low [24]. |

| Pharmacokinetic (PK) sampling & LC-MS/MS analysis | Measures drug concentration in plasma over time. This data is used to build PK models that are linked to pharmacodynamic (PD) effects on parasites in PKPD models [24]. | |

| Computational Tools | Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) solvers (e.g., in R, MATLAB, Python) | The numerical engine for simulating the time-course of infection and treatment as described by the mechanistic model equations [26] [25]. |

| Parameter estimation/optimization algorithms (e.g., MCMC, MLE) | Used to calibrate model parameters (e.g., infection rate, drug kill rate) by finding the best fit to experimental data [24] [25]. | |

| Global Sensitivity Analysis (e.g., Sobol', PRCC) | Identifies which model parameters (e.g., RBC production rate, drug efficacy) have the greatest influence on model outputs, guiding research focus and assessing robustness [28]. |

The choice of a within-host modeling framework is fundamentally guided by the research question at hand. For rapid, high-throughput screening of antimalarial candidates, simpler ODE-based or PKPD models parameterized with murine P. berghei data offer an efficient solution [25]. When the goal is to translate preclinical findings to humans, models incorporating P. falciparum dynamics from SCID mouse models and, crucially, human VIS data become indispensable [24]. Finally, for addressing broader public health challenges such as the evolution and spread of drug resistance, multi-scale models that integrate within-host dynamics with population-level transmission are essential [26] [27]. The emerging trend of ensemble modeling, which runs multiple plausible model structures in parallel, highlights a move towards quantifying uncertainty and making more robust predictions in antimalarial drug development [25]. As these frameworks continue to evolve, their integration with experimental data across scales will remain paramount for guiding the effective and sustainable control of malaria and other vector-borne parasitic diseases.

Translational pharmacology is a critical scientific discipline dedicated to bridging the gap between preclinical research findings and clinical application in human patients. This field operates along a continuum known as translational research, which the National Institutes of Health defines as including two primary areas of translation: the process of applying discoveries generated during laboratory research and preclinical studies to the development of human trials, and research aimed at enhancing the adoption of best practices in the community [29]. The first stage of translational research (T1) specifically serves as the bridge between basic laboratory research and human clinical trials, where findings from animal models, cell cultures, and molecular studies are prepared for application in human studies [29].

Murine models have become the mainstay in preclinical pharmacological research due to several practical advantages. Mice are small, breed readily, can be genetically modified with relative ease, and are generally inexpensive to maintain [30]. Their short gestation period and life span allow researchers to breed large numbers of animals and conduct multiple studies in a relatively short timeframe, accelerating the pace of drug discovery [30]. The central role of animal models in modern translational medicine is underscored by their position as the backbone for understanding disease pathophysiology and developing novel therapies for a wide spectrum of currently untreatable conditions [29].

Quantitative Analysis of Translation Rates

Success Rates Across Development Phases

A comprehensive 2024 umbrella review analyzing 122 articles encompassing 54 distinct human diseases and 367 therapeutic interventions provides robust quantitative data on animal-to-human translation rates. This large-scale analysis revealed that contrary to widespread assertions about poor translation, the transition rates from animal studies to human application were higher than previously reported, though significant attrition remains throughout the development process [31].

Table 1: Success Rates and Timeframes in Animal-to-Human Translation

| Development Stage | Success Rate | Median Transition Time | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any Human Study | 50% | 5 years | Half of therapies tested in animals advance to some form of human study |

| Randomized Controlled Trials | 40% | 7 years | Significant attrition occurs between early human studies and rigorous RCTs |

| Regulatory Approval | 5% | 10 years | Only 1 in 20 therapies reaching animal studies achieves final approval |

The data clearly demonstrates that while initial translation from animal models to human studies occurs at a relatively high rate (50%), significant attrition occurs throughout the development pipeline, with only 5% of therapies that reach animal studies ultimately achieving regulatory approval [31]. This indicates substantial challenges in both the design of animal studies and early clinical trials.

Concordance Between Animal and Human Results

The same comprehensive review conducted a meta-analysis on the concordance between animal and human study results, focusing on relative risks—the ratio of the proportion of positive animal studies to the proportion of positive clinical studies. This analysis was restricted to therapies with five or more published animal studies to reduce dataset noise [31].

The findings revealed an 86% concordance between positive results in animal and clinical studies, suggesting that when animal models show positive effects, these findings generally translate to human studies [31]. However, this high concordance must be interpreted alongside the low overall regulatory approval rate (5%), indicating that while efficacy often translates, safety concerns or insufficient clinical benefit may emerge in later development stages.

Methodological Protocols in Translational Research

Standardized Experimental Workflows

Robust methodological protocols are essential for generating translatable data from murine models. The following workflow outlines a standardized approach for translational pharmacology studies:

Diagram 1: Workflow for Murine to Human Translation

Murine Model Selection Criteria