FECRT vs. Coproantigen Reduction Test: A Comprehensive Agreement Analysis for Detecting Flukicide Resistance

This article provides a systematic analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the agreement, application, and interpretation of the Faecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT) and the Coproantigen Reduction...

FECRT vs. Coproantigen Reduction Test: A Comprehensive Agreement Analysis for Detecting Flukicide Resistance

Abstract

This article provides a systematic analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the agreement, application, and interpretation of the Faecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT) and the Coproantigen Reduction Test (CRT) for diagnosing anthelmintic resistance in Fasciola hepatica. It covers the foundational principles of both diagnostics, details standardized methodological protocols for field and experimental trials, and addresses key challenges and optimization strategies. By synthesizing evidence from controlled studies and field validations across ruminant species, this review highlights the complementary value of a multi-diagnostic approach and discusses its implications for sustainable parasite control and future research directions.

Understanding the Core Diagnostics: Principles of FECRT and CRT for Fluke Resistance

Definition and Core Principle

The Faecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT) is a primary in vivo diagnostic tool used in veterinary medicine to estimate the efficacy of anthelmintic compounds and to detect anthelmintic resistance in gastrointestinal nematodes of livestock and companion animals [1] [2]. The test's core principle is to calculate the percentage reduction in faecal egg counts (FEC) after the administration of an anthelmintic treatment, providing a direct measure of the treatment's performance in the field [1] [3].

The FECRT is performed by comparing the mean faecal egg count from a group of animals before treatment to the mean count from the same or a comparable group of animals after treatment [1]. The resulting percentage reduction indicates the proportion of the parasite population that was susceptible to the drug. A reduction below a specific threshold suggests that a portion of the parasite population is resistant, meaning the anthelmintic failed to eliminate them effectively [4] [1]. The test is crucial for monitoring the development and spread of drug-resistant parasites, a growing problem in veterinary parasitology [5].

Historical Context and Evolution

The FECRT has been the cornerstone for diagnosing anthelmintic resistance for decades. The World Association for the Advancement of Veterinary Parasitology (WAAVP) provided the first standardized methods for its detection in nematodes of veterinary importance, establishing critical guidelines for interpretation [1].

Recent advancements have led to significant updates in the recommended methodology. The table below summarizes the evolution of key FECRT guidelines:

Table: Evolution of FECRT Methodological Guidelines

| Aspect | Earlier WAAVP Guidelines | Current Recommendations and Updates |

|---|---|---|

| Study Design | Relied on post-treatment counts from both treated and untreated control groups (unpaired design) [1] | Now generally recommends using pre- and post-treatment counts from the same animals (paired design) for improved accuracy [2] |

| Minimum Egg Count | Required a minimum group mean faecal egg count (e.g., 150 EPG) before treatment [1] | New requirement focuses on a minimum total number of eggs counted under the microscope, not just a mean EPG [2] |

| Statistical Analysis | Based on arithmetic means and confidence intervals assuming normal data distribution [1] | Recognition that FEC data are non-normal; recommendation for Bootstrap or Bayesian methods to calculate confidence intervals [6] |

| Sample Size | Suggested using groups of at least 10-15 animals [1] | Flexible, power-based sample size calculations tailored to expected egg counts and variability [7] |

Furthermore, the understanding of faecal egg count data itself has evolved. Recent research demonstrates that FEC data are inherently non-normal, even upon transformation, and are often best represented by zero-inflated or negative binomial distributions [6]. This has prompted a shift away from statistical methods that assume normality and toward more robust frameworks like Bootstrapping and Bayesian hierarchical models for calculating confidence intervals, which provide more reliable efficacy estimates [1] [6].

Diagnostic Criteria and Interpretation

The interpretation of the FECRT relies on comparing the calculated percentage reduction against established species-specific thresholds. The criteria often involve both a point estimate for the percentage reduction and its associated confidence interval to account for statistical variability.

For sheep and goats, the WAAVP guidelines state that anthelmintic resistance is considered present if both of the following conditions are met:

- The percentage reduction in faecal egg counts is less than 95%.

- The corresponding lower 95% confidence limit is less than 90% [1].

If only one of these two criteria is met, then anthelmintic resistance is suspected but not confirmed [1]. It is critical to note that these thresholds are specific to small ruminants, and different thresholds are applied for other livestock such as cattle and horses [2]. For instance, in a cattle setting, a reduction of 90% or greater may be indicative of a successful deworming program [3].

Table: Interpretation of FECRT Results for Sheep and Goats

| Percentage Reduction | Lower 95% Confidence Limit | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| < 95% | < 90% | Resistance is present |

| < 95% | ≥ 90% | Resistance is suspected |

| ≥ 95% | < 90% | Resistance is suspected |

| ≥ 95% | ≥ 90% | Susceptible (no resistance indicated) |

The upcoming new WAAVP guidelines are expected to provide a more rigorous, dual-test classification framework. This framework uses a one-sided inferiority test for resistance and a one-sided non-inferiority test for susceptibility, which may lead to classifications of "resistant," "susceptible," or "inconclusive" [7]. To maintain a 5% Type I error rate with this two-test approach, the use of a 90% confidence interval is recommended instead of the historical 95% CI [7].

Standard Experimental Protocol

Conducting a reliable FECRT requires careful adherence to a standardized protocol. The following workflow and detailed steps outline the general process for a paired study design, which is now the recommended approach [2].

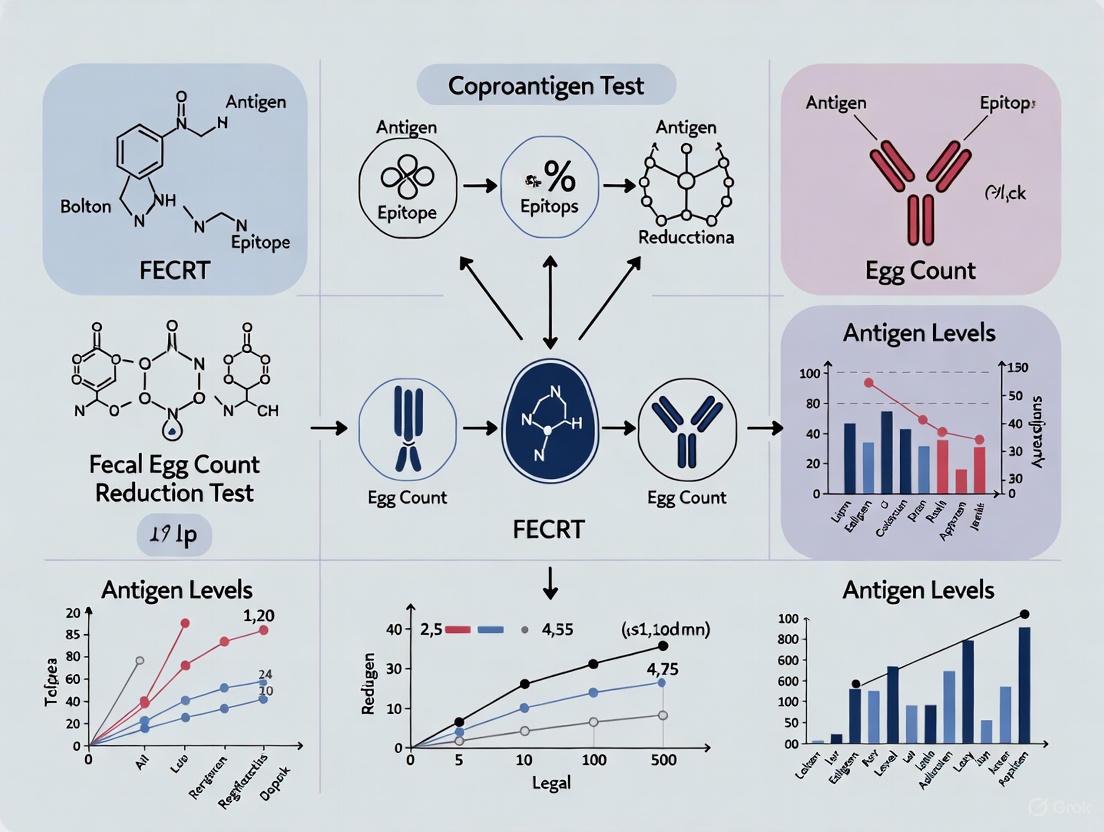

Figure 1: A standardized workflow for conducting a Faecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT).

Pre-Treatment Phase

- Animal Selection: Select a cohort of at least 10-15 animals from the same age and management group [1] [3]. For cattle, sampling about 20 head is often sufficient [3]. The ideal subjects are often young animals, such as those between six months and two years of age, as they are more likely to harbor significant parasite burdens [3].

- Pre-Treatment Sampling: Collect fresh faecal samples directly from the rectum of each selected animal immediately before anthelmintic treatment (Day 0) [4] [3]. A sample of 3-5 grams per animal is typically required [4]. These samples should be placed in leak-proof containers, refrigerated (not frozen), and shipped promptly to a diagnostic laboratory with a freezer pack [4] [3].

Treatment and Post-Treatment Phase

- Anthelmintic Administration: Administer the anthelmintic treatment at the correct dosage based on an accurate individual body weight measurement to avoid under-dosing, a common cause of treatment failure [6].

- Post-Treatment Sampling: Precisely 10 to 14 days after treatment, collect a second set of faecal samples from the same animals [4] [3]. This timing is critical as it allows for the drug to take effect and clears the eggs from susceptible worms, but is before new infections become patent.

Laboratory Analysis and Calculation

- Faecal Egg Counting: The faecal samples are processed in a laboratory using a quantitative technique, such as the McMaster method, to determine the number of eggs per gram (EPG) of faeces [8] [6]. The sensitivity of this method (e.g., 15, 25, or 50 EPG) can influence the results, particularly when counts are low [1] [6].

Calculation of Efficacy: The percentage reduction (FECR) is calculated using the formula:

FECR (%) = [1 - (Mean Post-Treatment FEC / Mean Pre-Treatment FEC)] × 100 [1]

The confidence interval for this percentage reduction is then calculated. As noted previously, modern approaches recommend using bootstrap or Bayesian methods due to the non-normal distribution of FEC data [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successfully executing a FECRT requires specific materials and reagents. The following table details the key components of the research toolkit.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for FECRT

| Item | Function/Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative FEC Method | A technique to count nematode eggs in faeces. The McMaster technique is most widely used. | Different diagnostic sensitivities exist (e.g., 15, 25, 50 EPG). The choice affects the detection of low-level counts and data distribution [8] [6]. |

| Anthelmintic Compounds | The drug(s) being tested for efficacy. Major classes include Benzimidazoles (BZ), Macrocyclic Lactones (ML), and Imidazothiazoles/Tetrahydropyrimidines (LV) [3] [5]. | Must be administered at the correct dosage based on accurate body weight. Resistance can be class-specific. |

| Larval Culture & Identification | Culturing faecal samples to develop larvae for morphological or molecular identification to genus/species level. | Visual morphology has limitations. DNA-based identification (e.g., nemabiome sequencing) increases accuracy and can prevent false-negative diagnoses [9]. |

| Statistical Software | Tools for calculating percentage reduction, confidence intervals, and interpreting results. | Standard software (e.g., R) with packages like "eggCounts" or "bayescount" are available to implement recommended Bayesian or bootstrap methods [1]. |

Limitations and Emerging Alternatives

Despite being the field method of choice, the FECRT has recognized limitations. The conventional counting techniques introduce variability not fully accounted for in traditional statistical analyses [1]. Furthermore, the test only detects patent infections and the correlation between egg counts and actual worm burden can be weak [8] [6]. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) regards the FECRT as an estimation of efficacy, not a confirmation of resistance, which requires controlled slaughter studies [6].

Emerging alternatives and refinements aim to overcome these challenges:

- Molecular Identification: Identifying larvae to species using DNA, rather than morphology, significantly increases the accuracy and confidence of efficacy estimates. One study found that genus-level identification resulted in a 25% false-negative diagnosis of resistance compared to species-level identification [9].

- Advanced Statistical Models: Bayesian hierarchical models and zero-inflated models are being developed to better handle the complex, aggregated distribution of faecal egg count data, providing more reliable efficacy estimates and confidence limits [1] [6].

- Coproantigen Reduction Tests: While not the focus of this guide, the user's thesis context mentions agreement analysis with coproantigen tests. These tests detect parasite-specific molecules in faeces and may offer advantages in detecting pre-patent infections or specific species. Research is ongoing to correlate coproantigen reduction with FECRT results for improved diagnostic accuracy.

The control of Fasciola hepatica (liver fluke) infections in livestock and humans relies heavily on anthelmintic drugs, with triclabendazole (TCBZ) being the frontline treatment due to its efficacy against both immature and adult fluke stages. However, the emergence and spread of TCBZ-resistant F. hepatica poses a significant threat to global health and food security. Accurate diagnosis of resistance is crucial for implementing effective control measures. This guide explores the Coproantigen Reduction Test (CRT), a refined diagnostic method for detecting TCBZ resistance, and objectively compares its performance with the traditional Faecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT) within the context of agreement analysis between these two assays.

Mechanism of the Coproantigen Reduction Test

The Coproantigen Reduction Test is an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-based diagnostic that detects specific parasite-derived proteins, known as coproantigens, in the faeces of infected hosts.

- Target Antigen: The primary antigen detected by commercial CRT kits (e.g., BIO K201, Bio-X Diagnostics) is cathepsin L, a protease secreted by the gastrodermal cells of both juvenile and adult Fasciola hepatica [10] [11]. Immunocytochemical studies have confirmed the specificity of this coproantigen to the fluke's gastrodermal cells [10] [12].

- Principle of Operation: The test employs a sandwich ELISA format. A capture antibody (e.g., the MM3 monoclonal antibody) is coated onto the microtiter plate to bind Fasciola-specific coproantigens from faecal supernatant samples. A detection antibody, often a polyclonal, is then used to form an antibody-antigen-antibody "sandwich," which is measured colorimetrically [11]. The test is designed to be semi-quantitative, with the optical density (OD) readings correlating with the level of infection [11].

- Reduction Test Protocol: For resistance diagnosis, the CRT protocol involves collecting a faecal sample before treatment and a second sample at 14 days post-treatment (dpt). Successful treatment (i.e., susceptibility to the drug) is indicated by the absence of coproantigens (a negative test result) at the 14-day post-treatment check [10] [13].

Key Advantages of CRT Over FECRT

The CRT offers several distinct diagnostic advantages over the traditional Faecal Egg Count Reduction Test, primarily stemming from the fundamental differences between detecting parasite proteins versus parasite eggs.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of CRT and FECRT

| Feature | Coproantigen Reduction Test (CRT) | Faecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT) |

|---|---|---|

| Target Analyte | Parasite-derived proteins (e.g., cathepsin L) | Parasite eggs in faeces |

| Detection of Pre-Patent Infection | Yes (as early as 4-6 weeks post-infection) [14] [12] | No (only during patent infection, ~10+ weeks) [14] |

| Indicator of Current Infection | Yes (antigens persist only for infection lifetime) [12] | Potentially no (eggs from dead flukes can be released from gall bladder) [14] [12] |

| Time to Post-Treatment Result | 14 days post-treatment [10] [13] | 14 days post-treatment [14] [13] |

| Definition of Treatment Success | Negative coproantigen result at 14 dpt [10] [13] | ≥95% reduction in faecal egg count at 14 dpt [14] [13] |

Diagram 1: The standardized workflow for conducting a Coproantigen Reduction Test (CRT) to diagnose triclabendazole resistance in F. hepatica.

Agreement Analysis: Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Numerous controlled and field studies have directly compared the CRT and FECRT, demonstrating a strong agreement between the two methods while also highlighting the superior sensitivity of the CRT in specific scenarios.

Controlled Sheep Trials

A key study compared both tests in sheep experimentally infected with F. hepatica isolates of known TCBZ susceptibility [14] [13]. The results demonstrated 100% agreement between the FECRT and CRT in correctly classifying the TCBZ-resistant Oberon isolate and the TCBZ-susceptible Cullompton and Fairhurst isolates. Furthermore, the study highlighted the CRT's ability to detect infection much earlier in the pre-patent period than sedimentation-based egg counts [14].

Field Studies in Cattle

A study on Australian cattle properties with suspected TCBZ resistance found the CRT to be a robust and sometimes more sensitive alternative to the FECRT [15] [16]. The results confirmed TCBZ-resistant F. hepatica on multiple farms.

Table 2: Comparative Field Efficacy of TCBZ in Cattle Using FECRT and CRT

| Property Type | % Reduction (FECRT) | % Reduction (CRT) | Resistance Diagnosis (FECRT) | Resistance Diagnosis (CRT) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dairy Property | 6.1 - 14.1% | 0.4 - 7.6% | Confirmed | Confirmed |

| Beef Properties | 25.9 - 65.5% | 27.0 - 69.5% | 3 out of 6 properties | 4 out of 7 properties |

The data from this field investigation confirmed that the CRT agreed with the FECRT in diagnosing resistance and, in one instance, identified an additional beef property with resistant flukes that the FECRT did not categorize as resistant [15] [16]. This suggests the CRT may have practical advantages in field settings with naturally acquired, mixed-burden infections.

Diagnostic Sensitivity and Correlation with Burden

Recent research continues to validate the performance of the coproantigen ELISA. A 2024 study found a moderate, statistically significant positive correlation (r²=0.716) between Fasciola faecal egg count (FFEC) and coproantigen optical density (OD) readings from the cELISA [11]. The study also established that the coproantigen ELISA had a 100% positivity rate for samples with more than 4.5 eggs per gram (epg), demonstrating its high sensitivity for detecting clinically relevant infections [11].

Essential Research Reagents and Protocols

The following toolkit details the core materials and methodological steps required to perform a standardized CRT.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for the Coproantigen Reduction Test

| Reagent / Material | Function and Specification |

|---|---|

| BIO K201 ELISA Kit | Commercial kit containing MM3 monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies, conjugates, and controls for detecting F. hepatica coproantigens. |

| MM3 Monoclonal Antibody | A highly sensitive and specific antibody that binds Fasciola coproantigens (primarily cathepsin L), forming the core of the capture ELISA. |

| Anti-Fasciola Polyclonal Antibody | Used as a complementary coating or detection antibody in the sandwich ELISA to improve antigen capture. |

| Reference Fasciola Antigen | Purified positive control antigen supplied with the kit to validate each test run and ensure proper assay functionality. |

| ProClin 300 | A preservative used in the preparation of faecal supernatants to prevent microbial growth and maintain antigen integrity. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

- Sample Collection: Collect individual faecal samples directly from the rectum of animals prior to anthelmintic treatment (Day 0) and again at 14 days post-treatment [10] [15].

- Sample Storage and Transport: Faecal samples can be stored at -20°C for several months without significant degradation of coproantigens [15]. Studies indicate that coproantigens are stable at low to moderate temperatures but may degrade at higher temperatures [10] [12].

- Faecal Supernatant Preparation:

- cELISA Procedure:

- Load 100 μL of the prepared supernatant into the wells of the BIO K201 ELISA plate, which are pre-coated with monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies [11].

- Follow the manufacturer's instructions for incubation, washing, and addition of the avidin-peroxidase conjugate and substrate [11].

- Measure the optical density (OD) at a wavelength of 450 nm.

- Interpretation of Results for Resistance:

- A test is considered positive if the OD value exceeds the kit's specified cut-off (e.g., OD > 8) [11].

- Successful Treatment/Susceptibility: A faecal sample that is coproantigen-positive on Day 0 becomes negative at 14 days post-treatment [10] [13].

- Treatment Failure/Resistance: The faecal sample remains coproantigen-positive at 14 days post-treatment, indicating surviving, active flukes [10] [15].

The Coproantigen Reduction Test represents a significant advancement in the diagnosis of anthelmintic resistance in Fasciola hepatica. Its core advantages—the ability to detect active infection during the pre-patent period and to provide a clear indicator of current infection status—address critical limitations of the traditional FECRT. Experimental data from both controlled trials and field studies show a strong agreement between CRT and FECRT, with CRT potentially offering enhanced sensitivity in field conditions. For researchers and veterinarians, the CRT is a robust, reliable tool that is crucial for monitoring drug efficacy, implementing evidence-based control strategies, and combating the growing threat of triclabendazole-resistant liver fluke.

Within the ongoing paradigm shift in parasite control—from calendar-based anthelmintic treatments to targeted, diagnostic-led approaches—the accurate detection of anthelmintic resistance has become a cornerstone of sustainable livestock production [17] [18]. The Faecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT) has long been the cornerstone technique for this purpose. The emergence of the Coproantigen Reduction Test (CRT) presents a complementary diagnostic tool. This guide objectively compares the performance of these two tests, framing the analysis within the context of agreement studies between FECRT and CRT protocols. It is designed to provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a clear comparison of diagnostic windows, technical challenges, and experimental applications of these key methodologies.

Core Diagnostic Principles and Workflows

Faecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT)

The FECRT is the established method for quantifying anthelmintic efficacy in the field by measuring the reduction in parasite egg output in faeces following treatment [2]. The test involves performing faecal egg counts (FEC) on samples collected from a group of animals immediately before treatment and then again at a defined interval afterwards (typically 14 days for ruminant nematodes, and 14-21 days for Fasciola hepatica) [13] [2]. The percentage reduction is calculated, with values below a defined threshold (e.g., <95% for triclabendazole against F. hepatica, or host- and drug-specific thresholds for nematodes) indicating suspected resistance [13] [2].

Typical FECRT Workflow:

Coproantigen Reduction Test (CRT)

The CRT detects parasite-specific antigen biomarkers shed into the host's faeces, typically using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) [19]. For Fasciola hepatica, a common commercial assay is the BIO K201 coproantigen ELISA (Bio-X Diagnostics) [13] [19]. Unlike the FECRT, which relies on visual egg counting, the CRT provides a quantitative optical density (OD) reading. Effective treatment is defined by the disappearance of coproantigens, often with the outcome interpreted as a binary positive/negative result at a specific post-treatment time point (e.g., 14 days) [13] [20].

Typical CRT Workflow:

Comparative Performance Analysis

Diagnostic Windows and Key Parameters

The following table summarizes the core performance characteristics of the FECRT and CRT, highlighting critical differences in their diagnostic windows and operational parameters.

Table 1: Comparative Diagnostic Windows and Key Parameters of FECRT and CRT

| Parameter | Faecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT) | Coproantigen Reduction Test (CRT) |

|---|---|---|

| Target of Detection | Intact parasite eggs [17] [18] | Parasite-derived coproantigens (e.g., cathepsin-type enzymes) [19] |

| Primary Output | Eggs per Gram (EPG); Percentage Reduction [2] | Optical Density (OD); Positive/Negative [13] [20] |

| Pre-Patent Detection | No, detects patent infections only [21] | Yes, can detect infections prior to egg production [19] |

| Post-Treatment Monitoring Interval | 14 days (nematodes), 14-21 days (F. hepatica) [13] [2] | 14 days (for F. hepatica) [13] |

| Key Threshold for Resistance | <95% reduction for TCBZ in F. hepatica [13] | Positive coproantigen result at 14 days post-treatment [13] |

| Correlation with Burden | Direct correlation with egg output [17] | Variable; can correlate with burden, but may plateau in high-burden infections [20] |

Technical Challenges and Limitations

A clear understanding of the limitations inherent to each method is crucial for robust experimental design and data interpretation.

Table 2: Technical Challenges and Limitations of FECRT and CRT

| Challenge Category | Faecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT) | Coproantigen Reduction Test (CRT) |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity & Specificity | Low sensitivity for non-patent, single-sex, or low-intensity infections [21]. Cannot differentiate eggs of many GIN species [17] [18]. | High sensitivity and specificity reported (e.g., 94.7% Se, 98.5% Sp for human fascioliasis) [20]. May fail to detect some high-burden cases [20]. |

| Sample & Storage Issues | Egg counts can decline due to hatching or degradation; samples must be kept cool and processed rapidly [17] [18]. | Less affected by storage conditions, but standard protocols for sample handling are still recommended. |

| Methodological Variability | High. Results vary with FEC method (McMaster, FLOTAC), flotation solution, analyst skill, and faecal consistency [17] [18]. | High standardization via commercial ELISA kits reduces operational variability [19]. |

| Key Practical Constraints | Requires adequate pre-treatment egg counts for statistical power [2]. Labor-intensive and time-consuming [21]. | Requires specialized equipment (ELISA plate reader) and reagents [19] [20]. Higher cost per sample. |

Experimental Protocols for Comparative Studies

Protocol for a Paired FECRT Study

Recent W.A.A.V.P. guidelines recommend a paired study design (pre- and post-treatment FEC from the same animals) over an unpaired design (comparing treated and untreated controls) [2].

- Animal Selection and Grouping: Select at least 10-15 animals per group. Animals should be of the same category and managed under identical conditions [17] [18]. Pre-treatment screening should ensure a minimum level of infection; modern guidelines focus on the total number of eggs counted rather than just a mean EPG [2].

- Pre-Treatment Sampling: Collect individual faecal samples directly from the rectum. Weigh a standardized amount of faeces (e.g., 3g for small ruminants, 5-6g for cattle). Process using a validated FEC method (e.g., McMaster, Mini-FLOTAC, or modified Wisconsin). Record pre-treatment EPG [2] [17].

- Treatment Administration: Accurately dose all animals with the anthelmintic under investigation, ensuring the correct formulation and dosage based on body weight.

- Post-Treatment Sampling: Collect individual faecal samples again at the appropriate interval (e.g., 14 days post-treatment for most nematodes and F. hepatica). Process samples using the identical FEC method used at pre-treatment [2].

- Calculation and Interpretation: Calculate the percentage reduction for each animal and the group mean. The FECRT percentage is calculated as FECRT (%) = (1 - (Mean Post-Treatment FEC / Mean Pre-Treatment FEC)) × 100. Compare the result against the established resistance threshold for the host species, parasite, and drug [2].

Protocol for a CRT Study

- Animal Selection and Grouping: Follow the same animal selection criteria as for the FECRT.

- Pre-Treatment Sampling: Collect individual faecal samples. A small sub-sample (e.g., 1-2g) is sufficient. Process samples according to the specific commercial ELISA kit instructions (e.g., BIO K201). This typically involves extracting soluble antigens from the faeces.

- Treatment Administration: Identical to the FECRT protocol.

- Post-Treatment Sampling: Collect individual faecal samples at the designated time point (14 days for F. hepatica). Process samples using the same ELISA protocol.

- Interpretation: The result is often interpreted as a binary outcome. Effective treatment is defined as samples becoming negative for coproantigen at the post-treatment check, whereas a positive result indicates treatment failure and potential resistance [13]. The rapid negativization of the test after successful treatment is a key advantage [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for FECRT and CRT Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Kource |

|---|---|---|

| BIO K201 ELISA Kit | Commercial coproantigen ELISA for detecting Fasciola hepatica antigens in faeces [13] [19]. | Bio-X Diagnostics, Jemelle, Belgium |

| MM3 Monoclonal Antibody | The core mAb used in capture ELISAs for F. hepatica coproantigen detection; likely targets a cathepsin-type enzyme [19] [20]. | In-house or commercial assay development |

| Flotation Solution | Solution with high specific gravity to float helminth eggs for microscopic counting in FEC (e.g., saturated sodium chloride, sucrose, or sodium nitrate) [17]. | Various suppliers |

| McMaster Slide | Standardized counting chamber for quantifying eggs per gram (EPG) of faeces in FECRT [17] [18]. | Various suppliers |

| Mini-FLOTAC Apparatus | Refined FEC technique that offers improved sensitivity and accuracy compared to traditional methods [17] [21]. | |

| Anti-Ascaris/Toxocara Coproantigen Antibodies | Polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies used in ELISA formats for detecting coproantigens of other helminths (e.g., Toxocara canis, Ancylostoma caninum) in research settings [19]. |

Both the FECRT and CRT are validated for the diagnosis of anthelmintic resistance, particularly for Fasciola hepatica [13]. The FECRT provides a direct measure of parasite fecundity but is constrained by the patent period and significant technical variability. The CRT, with its ability to detect pre-patent infections and offer high standardization, presents a valuable complementary tool. A multi-modal diagnostic approach, utilizing both tests in parallel, is increasingly recommended to improve diagnostic accuracy and the interpretation of anthelmintic efficacy studies, especially in the face of rising triclabendazole resistance [22] [23]. For researchers conducting agreement analysis, understanding the distinct diagnostic windows—where CRT can signal success via antigen disappearance before FECRT shows full egg reduction—is critical for reconciling results and advancing resistance detection protocols.

The Critical Need for Resistance Monitoring in the Era of Triclabendazole Overreliance

Triclabendazole (TCBZ) occupies a critical and unparalleled role in the control of fascioliasis, a parasitic disease caused by the liver fluke Fasciola hepatica that poses significant burdens on both global livestock production and human health in endemic regions. As the only anthelmintic drug with high efficacy against both immature and adult stages of the liver fluke, TCBZ has become the cornerstone of treatment and control strategies worldwide [24] [22]. This unique position has led to profound overreliance on a single chemical entity across veterinary and human medicine—a scenario that now threatens global fascioliasis control efforts. The emergence and spread of TCBZ-resistant Fasciola hepatica represents one of the most significant challenges in parasitology today, with resistance now confirmed across multiple continents and in both animal and human infections [24] [25] [26].

The economic implications of fascioliasis are substantial, with the parasite ranking as the 13th most important cause of economic loss in the Australian sheep meat industry alone [24] [22]. Similar significant losses are documented in Europe, estimated at €635 million annually across 18 countries, while in developing nations, the full economic impact remains underestimated due to limited data collection infrastructure [27]. In Argentina's Patagonia region, where prevalence reaches 60-70% in livestock, TCBZ resistance has now been confirmed, further complicating control efforts in endemic areas [25]. Perhaps more alarming is the rapid increase in treatment failures in human populations, with studies from Peru showing efficacy rates dropping to 55% after the first treatment and as low as 23% after four treatment rounds in pediatric populations [26]. This diminishing efficacy threatens to undo decades of public health progress and highlights the urgent need for enhanced resistance monitoring strategies that can detect resistance early and inform stewardship practices.

Diagnostic Assays for Resistance Detection: A Comparative Analysis

The accurate detection of TCBZ resistance depends on standardized diagnostic approaches that can differentiate true resistance from other causes of treatment failure. Two principal methodologies have emerged for field diagnosis: the faecal egg count reduction test (FECRT) and the coproantigen reduction test (CRT). Both assays are aligned with guidelines from the World Association for the Advancement of Veterinary Parasitology (W.A.A.V.P.), though specific guidelines for Fasciola remain under development [24] [22].

Fundamental Principles and Methodologies

The Faecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT) is a long-established method that defines successful TCBZ treatment as a ≥95% reduction in fluke faecal egg counts (FECs) at 14 days post-treatment [13] [28]. The test involves collecting individual faecal samples pre-treatment and at 14 days post-treatment, processing them through standardized sedimentation techniques to concentrate and count Fasciola eggs, and calculating the percentage reduction [13] [18]. The Coproantigen Reduction Test (CRT) offers an alternative approach that defines effective TCBZ treatment as faeces negative for Fasciola coproantigens at 14 days post-treatment as measured by commercial coproantigen ELISA tests such as the BIO K201 (Bio-X Diagnostics, Belgium) [13] [28]. This method detects metabolic antigens produced by late immature and adult flukes that are released into the bile and passed in faeces, enabling detection before egg laying begins [29].

Comparative Performance Data

Recent field studies have provided robust comparative data on the performance of these two diagnostic approaches under real-world conditions. The table below summarizes key comparative characteristics and performance metrics of both tests based on current research findings.

Table 1: Comparison of FECRT and CRT for Detection of Triclabendazole Resistance

| Parameter | Faecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT) | Coproantigen Reduction Test (CRT) |

|---|---|---|

| Measurement Principle | Quantification of faecal egg reduction | Detection of coproantigen clearance |

| Definition of Resistance | <95% reduction in FECs at 14 days post-treatment | Positive coproantigen result at 14 days post-treatment |

| Time to Result | 14 days post-treatment | 14 days post-treatment |

| Earliest Infection Detection | 8-12 weeks post-infection (patent period) | 6-8 weeks post-infection (late prepatent period) |

| Differentiates Active vs. Past Infection | Yes | Yes |

| Key Limitations | Low sensitivity in low-burden infections; requires patent infection | Diagnostic sensitivity issues reported in some field evaluations |

A significant 2025 Australian field investigation across eight farms demonstrated the practical utility of both approaches while highlighting their complexities in natural infections [24]. This study confirmed TCBZ resistance on one sheep property with 86-89% efficacy based on FECRT assessment, while also documenting the first potential report of albendazole resistance in F. hepatica infecting goats (79% efficacy) [24] [22]. The research emphasized that multi-modal diagnostics incorporating both FECRT and CRT improved resistance interpretation, particularly given the limitations of either test used alone [24].

Agreement Between Diagnostic Methods

Studies specifically designed to evaluate agreement between FECRT and CRT have demonstrated generally concordant results, with both tests successfully identifying known resistant and susceptible isolates [13]. However, important distinctions emerge in their operational characteristics. The enhanced MM3-COPRO ELISA test (eMM3-COPRO) has demonstrated higher sensitivity than coproscopy, detecting coproantigens in all samples with positive coproscopy and in 12% of samples with negative coproscopy [29]. This enhanced sensitivity for detecting active infection, even in pre-patent stages, provides the CRT with a theoretical advantage for earlier detection of resistance, particularly in low-burden infections where FECRT may yield false negatives due to the insensitivity of egg counting methods [29].

The diagnostic workflow for implementing these tests in resistance monitoring follows a structured pathway that incorporates both methodological approaches to maximize detection accuracy.

Figure 1: Diagnostic Workflow for TCBZ Resistance Monitoring

Beyond Phenotypic Detection: Molecular Insights into Resistance Mechanisms

The genetic underpinnings of TCBZ resistance have remained elusive until recent advances in genomic technologies enabled comprehensive investigations into resistance mechanisms. Groundbreaking research published in 2025 has revealed that TCBZ resistance has emerged independently in different global regions through distinct genetic pathways—a finding with profound implications for resistance monitoring strategies [30] [27].

Regional Heterogeneity in Resistance Mechanisms

Genomic analysis of more than 300 adult liver fluke samples from Peru has identified distinctive TCBZ resistance signatures that differ significantly from those found in the United Kingdom, demonstrating independent evolutionary origins rather than global spread of a single resistant genotype [30] [27]. The Peruvian resistant flukes exhibited genomic regions of high differentiation (FST outliers above the 99.9th percentile) that encode genes involved in the EGFR-PI3K-mTOR-S6K pathway and microtubule function [27]. Transcript expression differences in microtubule-related genes were observed between TCBZ-sensitive and TCBZ-resistant flukes, both without drug treatment and in response to treatment [27]. This contrasts with the ~3.2 Mb locus associated with TCBZ resistance identified in UK fluke populations, indicating that effective genetics-based surveillance must account for heterogeneous loci under selection across geographically distinct populations [27].

Toward Genetic Diagnostic Tools

This research has identified a set of 30 genetic markers capable of distinguishing drug-sensitive from drug-resistant parasites with ≥75% accuracy, laying the foundation for genetics-based surveillance tools [30] [27]. The potential development of such tools represents a paradigm shift in resistance monitoring, moving from phenotypic detection after treatment failure to genotypic prediction of resistance before treatment administration. The pathway analysis below illustrates the key molecular pathways implicated in TCBZ resistance mechanisms.

Figure 2: Molecular Pathways in TCBZ Resistance

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Implementing a comprehensive TCBZ resistance monitoring program requires specific research reagents and diagnostic tools. The following table details essential materials and their applications in resistance detection workflows.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for TCBZ Resistance Studies

| Reagent/Test | Application in Resistance Monitoring | Specific Utility |

|---|---|---|

| BIO K201 Coproantigen ELISA (Bio-X Diagnostics, Belgium) | CRT implementation | Detects Fasciola coproantigens in faecal samples; defines resistance as positive result at 14 days post-treatment |

| Enhanced MM3-COPRO Test | Early detection of active infection | Identifies coproantigens in late prepatent period (6-8 weeks post-infection); higher sensitivity than coproscopy |

| Triclabendazole Sulfoxide | In vitro susceptibility testing | Active metabolite of TCBZ used in motility assays for phenotypic resistance assessment |

| Genetic Marker Panels | Molecular surveillance | 30 identified SNPs enable differentiation of TCBZ-sensitive and resistant parasites with ≥75% accuracy |

| Nemabiome Sequencing | Co-infecting nematode analysis | Characterizes gastrointestinal nematode communities and detects benzimidazole resistance mutations |

The integration of these tools enables researchers to implement the multi-modal diagnostic approach increasingly recommended for accurate anthelmintic resistance detection [24] [18]. This comprehensive strategy is particularly important given the complex real-world scenarios where liver fluke infections coexist with gastrointestinal nematodes that may also exhibit resistance profiles, as demonstrated by Australian research that confirmed widespread benzimidazole resistance in co-infecting nematodes through Nemabiome sequencing [24] [22].

The critical threat of TCBZ resistance demands a coordinated, multifaceted approach to resistance monitoring that integrates phenotypic, immunodiagnostic, and emerging genotypic methods. The overreliance on a single anthelmintic agent has created a precarious situation for global fascioliasis control, with resistance now documented across five continents and treatment failures increasingly reported in human populations [24] [25] [26]. The comparative analysis of FECRT and CRT demonstrates that while both methods provide valuable resistance detection capabilities, their combined implementation offers superior diagnostic accuracy than either method alone.

Future resistance management must incorporate several key strategies: First, the development of Fasciola-specific W.A.A.V.P. guidelines is urgently needed to standardize resistance detection and reporting [24] [22]. Second, genetic tools must be refined and validated for field-deployable surveillance that accounts for the independent evolutionary origins of resistance across different geographical regions [30] [27]. Finally, integrated parasite management that reduces selection pressure through rational drug use, non-chemical control methods, and possibly future vaccination strategies represents the only sustainable path forward.

The era of TCBZ overreliance must give way to an era of sophisticated resistance monitoring and antimicrobial stewardship. Without such efforts, the global community risks losing its most effective tool against a parasite that affects millions of people and causes substantial economic losses in livestock production worldwide. The time to implement these comprehensive monitoring strategies is now, before expanding resistance creates an irreversible crisis in fascioliasis control.

Executing the Tests: Standardized Protocols and Field Application for Reliable Results

Fasciolosis, caused by the trematode Fasciola hepatica, represents a significant global threat to livestock health and production economics, with estimated annual losses exceeding $3.2 billion [31]. The emergence and spread of anthelmintic resistance, particularly to frontline drugs like triclabendazole (TCBZ), has intensified the need for robust diagnostic protocols to detect resistance early and accurately [22]. The Faecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT) stands as a cornerstone methodology for assessing drug efficacy against Fasciola hepatica in both research and field settings. When performed with standardized protocols, FECRT provides critical quantitative data on drug performance, informing treatment strategies and resistance management programs. This guide examines the standardized FECRT protocol within the broader context of diagnostic agreement with the coproantigen reduction test (CRT), providing researchers and drug development professionals with experimental methodologies, data interpretation frameworks, and technical specifications for implementation.

Experimental Protocols: FECRT Methodology

Animal Selection and Group Allocation

For reliable FECRT results, appropriate animal selection and group allocation are fundamental. Current guidelines recommend using young animals rather than adults due to their generally higher parasite burdens and more uniform egg shedding patterns [32]. A minimum of 10-15 animals per treatment group is necessary for statistical reliability in natural infection settings [22]. Animals should be allocated to treatment groups in a manner that ensures baseline comparability of infection levels, typically through stratified random assignment based on pre-treatment faecal egg counts (FECs).

Faecal Sample Collection and Processing

Collection Protocol: Fresh faecal samples should be collected directly from the rectum whenever possible. If collecting from freshly voided feces is unavoidable, samples should be taken from the top of the fecal pad to minimize environmental contamination [31]. For individual animal assessment, approximately 20-40g of feces is required [18].

Storage Conditions: Immediate processing is ideal. If delayed analysis is necessary, samples can be refrigerated (4-8°C) for up to 5 days for coproscopy. For coproantigen testing, analysis should occur within 2 days of collection. Samples intended for PCR analysis should be preserved at -20°C until DNA extraction [31].

Faecal Egg Counting Methods

Multiple techniques exist for quantifying Fasciola hepatica eggs in faecal samples:

Sedimentation Techniques: Simple sedimentation methods remain widely used globally. Approximately 5-10g of feces is suspended in normal saline or phosphate-buffered saline (100-200mL), sieved to remove coarse materials, and left to sediment for 30 minutes. After discarding supernatant, washing procedures repeat until the suspension clears, followed by microscopic examination of the sediment [31]. The Becker sedimentation method shows reliable performance, particularly with cattle feces [33].

Flukefinder Method: This specialized sedimentation system demonstrates superior egg recovery capabilities compared to simple sedimentation, particularly at low egg densities. Validation studies indicate Flukefinder reliably recovers eggs from samples with densities above 5 eggs per gram (EPG) and recovers approximately one-third of all eggs present across spiked samples [33].

Centrifugation Methods: Filtrate is centrifuged for 5 minutes at 1000 × g, after which supernatant is discarded and sediment examined microscopically. While widely used, prolonged centrifugation at high speed may cause egg distortion or disruption [31].

FLOTAC System: This quantitative technique uses 10g fecal samples suspended in 90mL tap water, followed by filtration and centrifugation in a specialized device with saturated sodium chloride solution (specific density 1.2). Both chambers of the FLOTAC reading disk are examined microscopically, with each observed egg representing 1 EPG [32].

Treatment Administration and Timing

The FECRT protocol involves precise timing of sampling relative to anthelmintic treatment:

Pre-treatment Sampling: Baseline faecal samples should be collected immediately before treatment administration (day 0).

Treatment Administration: Drugs should be administered at recommended label doses, with careful documentation of product, batch number, expiration date, and administration route. Accurate body weight measurement is essential for proper dosing [32].

Post-treatment Sampling: Follow-up samples should be collected 14 days post-treatment for TCBZ efficacy evaluation against Fasciola hepatica [14] [13] [28]. This interval allows sufficient time for drug action while minimizing potential reinfection.

Calculation Methods and Interpretation Criteria

The FECRT calculation follows a standardized formula:

FECR (%) = (1 - [arithmetic mean post-treatment FEC ÷ arithmetic mean pre-treatment FEC]) × 100

For Fasciola hepatica, successful TCBZ treatment is defined as ≥95% reduction in fluke faecal egg counts at 14 days post-treatment [14] [13] [28]. Results below this threshold indicate potential resistance, though confirmatory testing is recommended.

Recent studies have highlighted methodological variations in FECRT interpretation. Different statistical approaches, including Bayesian methods used by eggCounts and bayescount packages, can yield varying confidence intervals, influencing resistance classification [32]. Researchers should explicitly state the statistical methods employed when reporting FECRT results.

Comparative Performance Data: FECRT vs. CRT

Diagnostic Agreement Between FECRT and CRT

Multiple studies have evaluated the correlation between FECRT and coproantigen reduction test (CRT) for detecting anthelmintic resistance. The following table summarizes key comparative findings:

Table 1: Comparative Performance of FECRT and CRT in Triclabendazole Efficacy Evaluation

| Fluke Isolate | Previously Reported Status | FECRT Result | CRT Result | Necropsy Confirmation | Diagnostic Agreement | Study Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cullompton | Susceptible | Susceptible | Susceptible | Susceptible | Full agreement | [14] [13] |

| Leon | Resistant | Susceptible | Susceptible | Susceptible | Full agreement | [14] [13] |

| Fairhurst | Susceptible | Susceptible | Susceptible | Susceptible | Full agreement | [14] [13] |

| Oberon | Resistant | Resistant | Resistant | Resistant | Full agreement | [14] [13] |

Quantitative Reduction Metrics

Table 2: Reduction Metrics for FECRT and CRT in Field Efficacy Studies

| Parameter | FECRT | CRT | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Target | Viable eggs in feces | Fluke metabolic antigens in feces | CRT detects current infection, not just patency [14] |

| Time to Diagnosis | 14 days post-treatment | 14 days post-treatment | Comparable timing |

| Efficacy Threshold | ≥95% reduction in FEC | Negative coproantigen status | Different metrics, similar interpretation [13] |

| Pre-patent Detection | Limited to patent infections | Detects pre-patent infections | CRT enables earlier intervention [14] |

| Field Implementation | Accessible, requires microscope | Requires specialized ELISA | FECRT more suitable for resource-limited settings |

| Potential Confounders | Gall bladder egg release post-treatment | None identified | FECRT potentially affected by residual eggs [14] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Fasciola hepatica FECRT and CRT Studies

| Reagent/Kit | Application | Specifications | Research Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| BIO K201 ELISA | Coproantigen detection | Commercial ELISA (Bio-X Diagnostics) | Quantifies fluke metabolic antigens; defines CRT efficacy as negative status at 14dpt [14] [13] [28] |

| Flukefinder | Faecal egg counting | Specialized sedimentation device | Recovers eggs at densities >5 EPG; superior recovery compared to simple sedimentation [33] |

| FLOTAC System | Faecal egg counting | Quantitative centrifugation method | Provides standardized egg counting with high sensitivity [32] |

| Saturated NaCl Solution | Faecal flotation | Specific density: 1.200 | Standard flotation solution for egg isolation [32] |

| eggCounts Package | Statistical analysis | Bayesian framework for FECRT | Calculates FEC reduction with confidence intervals [32] |

Workflow and Diagnostic Pathways

Diagram 1: Standardized FECRT Workflow for Fasciola hepatica

Diagram 2: Diagnostic Pathways for Fasciola hepatica and Resistance Detection

Discussion

The standardized FECRT protocol provides a critical tool for detecting anthelmintic resistance in Fasciola hepatica, with the 14-day post-treatment sampling and ≥95% efficacy threshold serving as well-validated benchmarks. The strong diagnostic agreement between FECRT and CRT demonstrated in controlled studies supports the validity of both methods for TCBZ resistance detection [14] [13]. However, each method presents distinct advantages: FECRT offers accessibility and technical simplicity, while CRT provides earlier detection capability and potentially fewer confounders.

Recent field investigations highlight the practical challenges in FECRT implementation, including the impact of diagnostic sensitivity on resistance interpretation [22]. Methodological variations in faecal egg counting techniques, particularly between simple sedimentation and specialized systems like Flukefinder, can significantly influence egg recovery rates and consequently, FECRT results [33]. This technical variability underscores the necessity for standardized protocols when comparing results across studies or monitoring resistance trends over time.

The emergence of multi-drug resistant helminth populations further complicates FECRT interpretation. Recent research employing nemabiome sequencing has revealed complex gastrointestinal nematode communities co-infecting study animals, with widespread benzimidazole resistance signatures detected in Haemonchus contortus populations [22]. This highlights the importance of comprehensive parasite community assessment alongside FECRT implementation to contextualize anthelmintic efficacy findings.

For drug development professionals, these standardized protocols provide critical frameworks for evaluating novel fasciolicides against established benchmarks. The consistent methodology enables meaningful comparison across clinical trials and facilitates regulatory evaluation of efficacy claims. For field veterinarians and researchers, understanding the technical nuances of FECRT implementation ensures appropriate application and interpretation of resistance testing results, ultimately supporting more sustainable liver fluke control programs.

The standardized FECRT protocol for Fasciola hepatica, characterized by precise sampling timing at 14 days post-treatment, standardized egg counting methodologies, and the ≥95% efficacy threshold, provides an essential tool for anthelmintic resistance detection and drug efficacy evaluation. The strong diagnostic agreement between FECRT and CRT supports both methods' validity, with each offering complementary advantages for different research and field applications. As anthelmintic resistance continues to emerge globally, adherence to these standardized protocols becomes increasingly critical for generating comparable, reliable data to inform treatment strategies and drug development pipelines. The integration of these diagnostic methods within comprehensive parasite management programs represents the most sustainable approach to addressing the growing threat of fasciolosis in global livestock production.

The diagnosis of anthelmintic resistance represents a critical challenge in veterinary parasitology, relying on standardized diagnostic assays and rigorously interpreted efficacy thresholds. The Faecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT) has served as the primary phenotypic test for detecting resistance in gastrointestinal nematodes and liver fluke for decades, typically using a 95% reduction threshold in faecal egg counts to define susceptibility. More recently, the Coproantigen Reduction Test (CRT) has emerged as a valuable diagnostic tool for liver fluke, particularly for Fasciola hepatica, defining successful treatment by the absence of coproantigens post-treatment. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these tests, their established efficacy cut-offs, and experimental protocols, contextualized within research on their agreement for detecting resistance to key anthelmintics like triclabendazole.

Anthelmintic resistance threatens sustainable livestock production globally. The Faecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT) is the most widely used method for detecting resistance at the farm level due to its direct measurement of anthelmintic efficacy (phenotype) across all anthelmintic classes [34]. Its utility spans gastrointestinal nematodes in ruminants and horses, as well as liver fluke (Fasciola hepatica) infections. The test operates on a simple principle: calculating the percentage reduction in mean faecal egg count (FEC) in a group of animals following treatment with an anthelmintic. A reduction below a defined cut-off (historically <95% for many nematodes) indicates resistance [14] [35].

For liver fluke, specifically Fasciola hepatica, the Coproantigen Reduction Test (CRT) has been developed to address several limitations of the FECRT. The CRT employs a sandwich ELISA (e.g., the BIO K201 ELISA, Bio-X Diagnostics) to detect Fasciola-specific proteins in host faeces [10] [36]. A successful treatment is indicated by the absence of these coproantigens at a defined time point post-treatment (e.g., 14 days) for triclabendazole (TCBZ) [10]. The CRT offers a significant advantage by enabling efficacy assessment during the pre-patent period of infection, a period when immature flukes are present but not yet producing eggs [14] [36].

Establishing Efficacy Cut-Offs: A Data-Driven Comparison

The interpretation of both FECRT and CRT hinges on pre-defined efficacy thresholds that distinguish susceptible from resistant parasite populations. The tables below summarize the key efficacy cut-offs and diagnostic performance characteristics for both tests.

Table 1: Standard Efficacy Cut-Offs for Anthelmintic Resistance Tests

| Test | Target Parasite | Efficacy Threshold for Susceptibility | Time Point Post-Treatment | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FECRT | Gastrointestinal Nematodes | ≥ 95% reduction in FEC | 10-14 days | [34] [4] |

| FECRT | Fasciola hepatica | ≥ 90-95% reduction in FEC | 14-21 days | [35] [13] |

| CRT | Fasciola hepatica | Absence of coproantigens (or ≥90% reduction in positivity) | 14 days | [14] [10] [35] |

Table 2: Comparative Diagnostic Performance of FECRT and CRT for F. hepatica

| Characteristic | Faecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT) | Coproantigen Reduction Test (CRT) |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Marker | Faecal egg count (FEC) | Fluke-derived coproantigens (e.g., cathepsin L) |

| Pre-Patent Detection | Not possible | Yes, from ~5 weeks post-infection |

| Time to Post-Tx Result | 14-21 days | 14 days |

| Potential False Positives | Yes, from gall bladder-stored eggs post-treatment | No, indicates current, active infection |

| Standardized Guideline | No WAAVP guidelines for fluke; available for nematodes | Protocol standardized in experimental trials |

| Key Limitation | Cannot assess efficacy against immature flukes | Diagnostic sensitivity can be lower in low-burden infections [22] |

Experimental Protocols for FECRT and CRT

Robust, standardized protocols are essential for generating reliable and comparable data on anthelmintic efficacy.

Faecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT) Protocol

The following protocol is adapted for Fasciola hepatica, with notes for nematode applications.

- Animal Selection and Grouping: Select at least 10-15 animals from the same management group with confirmed patent infection via faecal egg count [4] [35]. For nematodes, 10-12 animals per treatment group are common [34].

- Pre-Treatment Sampling: Collect individual faecal samples directly from the rectum of each selected animal. Record the identity of each animal. Perform a faecal egg count (e.g., using sedimentation for fluke eggs or McMaster technique for nematode eggs) on each individual sample [34] [35].

- Anthelmintic Treatment: Administer the anthelmintic to be tested at the manufacturer's recommended dose, ensuring accurate dosing based on individual animal weight. Best practice dosing must be followed to avoid under-dosing, a common cause of apparent failure [35].

- Post-Treatment Sampling: At 14 days post-treatment (dpt) for fluke [14] or 10-14 dpt for nematodes [4], collect faecal samples from the same individually identified animals.

- Post-Treatment Faecal Egg Count: Perform faecal egg counts on the post-treatment samples using the same method as the pre-treatment counts.

- Calculation and Interpretation: Calculate the percentage reduction in mean faecal egg count using the formula: % Reduction = (1 - (Mean Post-Tx FEC / Mean Pre-Tx FEC)) × 100 For F. hepatica, a reduction of <90-95% is suggestive of resistance [35] [13]. For nematodes, the standard threshold is <95% [34].

Coproantigen Reduction Test (CRT) Protocol forFasciola hepatica

- Animal Selection and Pre-Treatment Sampling: As for the FECRT, collect individual faecal samples from 10 or more animals [35].

- Coproantigen Analysis: Test the faecal samples using the commercial BIO K201 coproantigen ELISA (or equivalent) according to the manufacturer's instructions. This typically involves preparing a faecal supernatant which is then applied to the ELISA plate [10] [36].

- Anthelmlmintic Treatment: Treat the animals with the anthelmintic (e.g., triclabendazole) at the recommended dose rate.

- Post-Treatment Sampling and Analysis: At 14 days post-treatment, collect faecal samples from the same animals and re-test them using the coproantigen ELISA [14] [10].

- Interpretation: Successful treatment (susceptibility) is defined by the absence of coproantigens in the faeces at 14 dpt. The continued presence of coproantigens indicates treatment failure and potential resistance [10] [36]. Some protocols also interpret a reduction in mean percentage positivity of less than 90% as indicative of resistance [35].

Diagram 1: Standard FECRT workflow for detecting anthelmintic resistance.

Agreement Analysis Between FECRT and CRT in Research

Comparative studies have evaluated the concordance between FECRT and CRT for diagnosing resistance, particularly to triclabendazole (TCBZ) in Fasciola hepatica.

A controlled sheep trial comparing the two tests using TCBZ-susceptible and TCBZ-resistant F. hepatica isolates found a high level of agreement. Both the FECRT and CRT correctly indicated TCBZ success against the susceptible Cullompton and Fairhurst isolates and TCBZ failure against the resistant Oberon isolate [14] [13]. This study underscored a key advantage of the CRT: its ability to provide a clear negative result for coproantigens post-treatment in successful treatments, eliminating the ambiguity that can arise in FECRT from the release of stored fluke eggs from the gall bladder after fluke death [14] [36].

However, the agreement is not infallible and can be influenced by the stage of infection and diagnostic sensitivity. The CRT allows for efficacy evaluation during the pre-patent period, where the FECRT is inherently useless [14]. Furthermore, a recent 2025 field study highlighted that low-burden F. hepatica infections can challenge the diagnostic sensitivity of the coproantigen ELISA, potentially affecting CRT results and leading to discrepancies with FECRT findings [22]. The study concluded that a multi-modal diagnostic approach, using both FECRT/sedimentation and CRT in parallel, improves the accuracy of resistance interpretation in field trials [22].

Diagram 2: Logical relationship between FECRT and CRT results in agreement analysis.

Advancements in FECRT: The Nemabiome and Statistical Frameworks

Traditional FECRT, which relies on total strongyle egg counts, has a significant limitation: it cannot differentiate efficacy against different nematode species within a polyparasitic infection. Larval culture and morphological identification have been used to apportion egg counts to genera, but this method is often inaccurate for species-level identification [34].

- Nemabiome Deep Amplicon Sequencing: This molecular technique involves deep amplicon sequencing of DNA from larvae cultured from faeces, allowing for precise identification of all nematode species present [34] [22]. Research demonstrates that relying on genus-level identification can lead to a 25% false negative diagnosis of resistance; a genus may appear susceptible while one underlying resistant species is masked [34]. Furthermore, increasing the number of larvae identified (sample size) to over 500 significantly reduces uncertainty around the efficacy estimate for each species [34].

- Statistical Framework and Sample Size: The FECRT has also been strengthened by improved statistical frameworks. New approaches use a combination of inferiority and non-inferiority tests to classify results as resistant, susceptible, or inconclusive [7]. This framework, which underpins upcoming WAAVP guidelines, facilitates prospective sample size calculations based on statistical power, ensuring tests are sufficiently robust to detect resistance [7].

Table 3: Impact of Larval Identification Method on FECRT Diagnosis

| Identification Method | Level of Identification | Key Limitation | Impact on Resistance Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morphological | Genus/Species-complex | Inaccurate for some species; L3 stages of some species are morphologically similar. | Can mask resistance; led to 25% false negative diagnosis in one study [34]. |

| Nemabiome (DNA) | Species | Higher cost and technical requirement. | Reveals resistance in poorly represented species; increases accuracy and confidence in efficacy estimates [34] [22]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for FECRT and CRT Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| BIO K201 Coproantigen ELISA | Commercial kit for detection of Fasciola coproantigens in faeces; core of the CRT. | Bio-X Diagnostics, Jemelle, Belgium [10] [36]. |

| McMaster Slide | For performing faecal egg counts (FECs). Enumerates eggs per gram (EPG) of faeces. | Typically with a sensitivity of 50 EPG or lower [34]. |

| Triclabendazole (TCBZ) | The frontline fasciolicide for which resistance is commonly tested. | Formulated for oral or injectable administration. Activity against immature and adult flukes [14] [35]. |

| Closantel & Nitroxynil | Alternative flukicides used in resistance management or as positive controls in trials. | Primarily active against adult fluke stages [22] [35]. |

| PCR Reagents & Nemabiome Panels | For DNA-based identification of nematode larvae to species from faecal cultures. | Includes primers for the ITS-2 rDNA region and high-throughput sequencing capabilities [34] [22]. |

| Standard Sedimentation Kit | For concentrating and detecting Fasciola eggs in faeces. | Used for patent infection diagnosis and FECRT for liver fluke [22] [35]. |

Diagram 3: Workflow for a nemabiome-enhanced FECRT, enabling species-specific efficacy estimates.

The definition of anthelmintic resistance continues to rely on the rigorous application and interpretation of in vivo efficacy tests. The FECRT, with its historical 95% reduction cut-off, remains a cornerstone of resistance detection. However, the advent of the CRT for liver fluke provides a crucial tool for earlier and potentially more definitive efficacy assessment. Research confirms a strong agreement between these tests, though discrepancies necessitate an understanding of their respective limitations. Future directions are firmly pointed towards the integration of molecular tools like nemabiome sequencing into the FECRT framework and the adoption of more powerful statistical models. These advancements collectively enhance the diagnostic accuracy, confidence, and repeatability essential for researchers and drug development professionals combatting the pervasive threat of anthelmintic resistance.

The Coproantigen Reduction Test (CRT) has emerged as a critical diagnostic tool for detecting anthelmintic resistance in liver fluke (Fasciola hepatica), particularly against the frontline drug triclabendazole (TCBZ). Within the context of agreement analysis between Faecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT) and coproantigen reduction test research, CRT offers distinct advantages for assessing drug efficacy. Unlike FECRT, which relies on microscopic identification of eggs, CRT detects coproantigens present during pre-patent infections, providing earlier indicators of current infection and treatment failure [14]. This technical comparison guide examines standardized CRT protocols, performance characteristics relative to alternative methods, and experimental data supporting its application in veterinary parasitology research and drug development.

Methodological Comparison: CRT Versus FECRT

Fundamental Technical Differences

The FECRT and CRT employ fundamentally different approaches to assess anthelmintic efficacy. The FECRT measures reduction in faecal egg counts post-treatment, with successful treatment defined as ≥95% reduction at 14 days post-treatment for Fasciola hepatica [14]. In contrast, the CRT utilizes a coproantigen ELISA to detect parasite-derived proteins in faeces, with successful treatment indicated by absence of coproantigens at 14 days post-treatment [14] [10].

A key distinction lies in their temporal application: coproantigens are detectable from approximately 5 weeks post-infection onward, significantly earlier than faecal eggs, allowing the CRT to evaluate drug efficacy against immature fluke stages that would be undetectable by FECRT [10]. Furthermore, the CRT eliminates potential false positives from fluke eggs released from the gall bladder after successful treatment, a documented limitation of FECRT [14].

Comparative Diagnostic Performance

Research comparing these assays against four different Fasciola hepatica isolates (Cullompton, Leon, Fairhurst, and Oberon) demonstrated concordance between FECRT and CRT in identifying TCBZ-resistant and susceptible isolates, with both tests correctly classifying the Oberon isolate as resistant [14]. However, the CRT provided additional advantages in early infection detection, identifying positives significantly sooner than faecal egg examination across all isolates [14].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of FECRT and CRT for Fasciola hepatica

| Parameter | FECRT | CRT |

|---|---|---|

| Time to Post-Treatment Assessment | 14 days | 14 days |

| Efficacy Threshold | ≥95% reduction in egg counts | Absence of coproantigens |

| Pre-patent Infection Detection | No | Yes (from 5 weeks post-infection) |

| Risk of False Positives | Possible from gall bladder eggs | Minimal |

| Sample Stability Considerations | Standard faecal preservation | Temperature-sensitive; avoid high temperatures |

Recent field investigations (2025) in naturally infected sheep, cattle, and goats have confirmed the utility of combined diagnostic approaches, utilizing both FECRT and CRT to improve interpretation accuracy for detecting TCBZ resistance [22]. This multi-modal approach helps address limitations of either test used independently under field conditions.

Standardized CRT Protocol Implementation

Sample Collection and Processing

Standardized CRT protocol requires collection of individual faecal samples from 10 animals prior to treatment with a flukicide [35]. Following treatment administered using best practice dosing procedures, faecal samples are collected from the same 10 animals at 14 days post-treatment for Fasciola hepatica [14] [10] or 21 days post-treatment according to some field guidelines [35].

Critical consideration must be given to sample storage conditions, as research indicates that while low to moderate temperatures have minimal impact on coproantigen stability, higher temperatures may degrade the target antigens [10]. For optimal results, samples should be processed promptly or stored at -20°C to preserve antigen integrity until testing [10].

ELISA Methodology and Interpretation

The standardized CRT employs the BIO K201 Fasciola coproantigen ELISA (Bio-X Diagnostics, Jemelle, Belgium) for detection of Fasciola hepatica coproantigens [14] [10]. The assay procedure follows standard sandwich ELISA protocol:

- Coated plates are incubated with samples and standards

- Biotin-conjugated detection antibody is added

- Avidin-HRP conjugate is introduced

- TMB substrate solution is added for color development

- Reaction is stopped with acid and absorbance measured at 450nm [37] [38]

For triclabendazole efficacy assessment, successful treatment is indicated by conversion from coproantigen-positive to coproantigen-negative at 14 days post-treatment [10]. Quantitative interpretation suggests that the mean percentage positivity should ideally fall by at least 90% following successful treatment [35].

Immunocytochemical studies have confirmed that the target coproantigen originates specifically from the gastrodermal cells of both adult and juvenile flukes, explaining its correlation with active infection [10].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for CRT Implementation

| Item | Specification | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| BIO K201 Fasciola coproantigen ELISA | Sandwich ELISA format; detects F. hepatica coproantigens | Primary test for CRT; specific to fasciolid coproantigens |

| Pre-coated 96-well microplate | Antibody-specific coating | Provided with commercial ELISA kits |

| Biotin-conjugated antibody | Detection reagent A | Target-specific binding |

| Avidin-HRP conjugate | Detection reagent B | Enzyme conjugation for signal generation |

| TMB Substrate | Colorimetric development | Yields measurable color change proportional to antigen concentration |

| Stop Solution | Acidic solution (typically sulfuric acid) | Terminates enzyme-substrate reaction |

| Wash Buffer | 30× concentrate, diluted to 1× | Removes unbound reagents between steps |

| Microplate Reader | 450nm filter capability | Quantification of optical density |

Experimental Data and Efficacy Assessment

Controlled Trial Evidence

In controlled sheep trials evaluating TCBZ efficacy against different Fasciola hepatica isolates, the CRT correctly identified treatment outcomes consistent with necropsy confirmation. The test demonstrated 100% sensitivity for detecting coproantigens in known infected animals from 5 weeks post-infection onward, and successfully differentiated between TCBZ-susceptible (Cullompton) and TCBZ-resistant (Sligo) isolates based on coproantigen presence/absence at 14 days post-treatment [10].

The diagnostic performance of CRT in field conditions was demonstrated in a 2025 Australian study, where it helped confirm TCBZ resistance on one sheep property (86-89% efficacy) while identifying susceptibility on a goat property (97-98% efficacy) [22]. The same study also reported the first potential case of albendazole resistance in Fasciola hepatica infecting goats (79% efficacy), detectable through the CRT methodology [22].

Quantitative Comparison Data

Table 3: Experimental Efficacy Results from FECRT and CRT Comparative Studies

| Fluke Isolate | Reported Status | FECRT Result | CRT Result | Necropsy Confirmation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cullompton | TCBZ-susceptible | Efficacy confirmed | Efficacy confirmed | Flukes eliminated |

| Leon | TCBZ-resistant | Efficacy confirmed | Efficacy confirmed | Flukes eliminated |

| Fairhurst | TCBZ-susceptible | Efficacy confirmed | Efficacy confirmed | Flukes eliminated |

| Oberon | TCBZ-resistant | Reduced efficacy | Reduced efficacy | Flukes survived |

| Sligo | TCBZ-resistant | N/A | Reduced efficacy | Flukes survived |

Methodological Workflow and Diagnostic Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the standardized CRT protocol and its relationship to FECRT within anthelmintic resistance research:

The standardization of CRT protocols represents a significant advancement in anthelmintic resistance detection, particularly for liver fluke infections where FECRT alone has recognized limitations. The robust methodology, supported by commercial ELISA kits and defined interpretation criteria, enables reliable assessment of drug efficacy against both immature and mature parasite stages.

Current research indicates strong agreement between FECRT and CRT for classifying resistant and susceptible isolates [14], supporting the use of combined diagnostic approaches for enhanced confidence in resistance detection [22]. Future development of species-specific WAAVP guidelines for flukicide resistance testing would further strengthen standardization across research and diagnostic settings [22].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the CRT protocol offers a validated, sensitive approach for monitoring anthelmintic efficacy in both experimental trials and field investigations, providing critical data for understanding resistance emergence and developing sustainable parasite control strategies.

The emergence of anthelmintic resistance in Fasciola hepatica (liver fluke) represents a significant threat to global livestock production and food security. The economic impact is substantial, with liver fluke identified as the 13th most important cause of economic loss in the Australian sheep meat industry alone [22]. Triclabendazole (TCBZ) remains the frontline anthelmintic for managing Fasciola hepatica due to its unique efficacy against both immature and mature fluke stages, but its utility is increasingly compromised by widespread drug resistance [14] [22].

Robust field trial design is essential for accurately detecting resistance and informing sustainable control strategies. This guide compares two primary diagnostic assays—the Faecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT) and the Coproantigen Reduction Test (CRT)—focusing on their experimental protocols, performance characteristics, and practical integration with modern farm management systems. The analysis is framed within the context of agreement analysis between these diagnostic methods, providing researchers with evidence-based guidance for implementing these tools in resistance surveillance programs.

Comparative Assay Analysis: FECRT vs. CRT

Fundamental Principles and Definitions

The FECRT and CRT employ distinct approaches to assess anthelmintic efficacy post-treatment: