Evaluating Digital Specimen Databases for Morphology Training: A 2025 Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to critically evaluate and select digital specimen databases for morphology training.

Evaluating Digital Specimen Databases for Morphology Training: A 2025 Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to critically evaluate and select digital specimen databases for morphology training. It covers foundational principles of specimen digitization and data standards, practical methodologies for database integration into training workflows, strategies to overcome common data quality and technical challenges, and rigorous techniques for validating database utility and comparing platform performance. By synthesizing current standards and emerging trends, this guide empowers professionals to leverage high-quality digital data to enhance training efficacy and accelerate biomedical research.

Understanding Digital Specimen Databases: Core Concepts and Data Standards

The field of morphological research is undergoing a profound transformation, moving from the traditional examination of physical specimens under a microscope to the analysis of high-resolution digital representations. This digitization process enables unprecedented opportunities for data preservation, sharing, and large-scale computational analysis. For researchers in systematics, drug development, and comparative morphology, digital specimen databases have become indispensable tools that facilitate collaboration and enhance analytical capabilities. These databases vary significantly in their architecture, functionality, and suitability for different research scenarios. This guide provides an objective comparison of digital platforms for morphological data, with a specific focus on their application in training and research, supported by experimental data and clear performance metrics.

Digital Specimen Databases: A Comparative Landscape

Digital specimen databases serve as specialized repositories for storing, managing, and analyzing morphological data. They can be broadly categorized into vector databases designed for machine learning embeddings, media-rich platforms for images and associated metadata, and specialized morphological workbenches that combine both functions. The core function of these systems is to make morphological data findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR), while providing tools for quantitative analysis.

Table 1: Core Platform Types and Their Research Applications

| Platform Type | Primary Function | Typical Data Forms | Research Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vector Databases [1] | Similarity search on ML embeddings | Numerical vectors (e.g., from images) | Semantic search, phenotype clustering, anomaly detection |

| Media Archives [2] | Storage and annotation of media files | Images, 3D models, video | Phylogenetic matrices, comparative anatomy, educational datasets |

| Integrated Workbenches [3] | Combined analysis and storage | Images, numerical features, classifications | High-content screening, clinical pathology, automated cell classification |

Platform Performance Comparison: Quantitative Analysis

Vector Database Performance Metrics

Vector databases specialize in high-dimensional search and are optimized for storing and querying vector embeddings used in large language model and neural network applications [1]. Unlike traditional databases, they excel at similarity searches across complex, unstructured data such as images and natural language.

Table 2: Vector Database Performance Comparison [1]

| Database | Open Source | Key Strengths | Throughput | Latency | Primary Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinecone | No | Managed cloud service, no infrastructure requirements | High | Low | E-commerce suggestions, semantic search |

| Milvus | Yes | Highly scalable, handles trillion-scale vectors | Very High | Very Low | Image search, chatbots, chemical structure search |

| Weaviate | Yes | Cloud-native, hybrid search capabilities | High | Low | Question-answer extraction, summarization, classification |

| Chroma | Yes | AI-native, "batteries included" approach | Medium | Medium | LLM applications, document retrieval |

| Qdrant | Yes | Extensive filtering support, production-ready API | High | Low | Neural network matching, faceted search |

Digital Morphology Analyzer Performance

Digital morphology (DM) analyzers have advanced clinical hematology laboratories by enhancing the efficiency and precision of peripheral blood smear analysis [3]. These systems automate blood cell classification and assessment, reducing manual effort while providing consistent results.

Table 3: Digital Morphology Analyzer Capabilities [3]

| Platform | FDA Approved | Throughput (slides/h) | Cell Types Analyzed | Stain Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CellaVision DM1200 | Yes | 20 | WBC differential, RBC morphology, PLT estimation | Romanowsky, RAL, MCDh |

| CellaVision DM9600 | Yes | 30 | WBC differential, RBC overview, PLT estimation | Romanowsky, RAL, MCDh |

| Sysmex DI-60 | Yes | 30 | WBC differential, RBC overview, PLT estimation | Romanowsky, RAL, MCDh |

| Mindray MC-80 | No | 60 | WBC pre-classification, RBC pre-characterization | Romanowsky |

| Scopio X100 | Yes | 15 (40 with 200 WBC diff) | WBC differential, RBC morphology | Romanowsky |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Benchmarking Database Performance

Robust benchmarking is essential for evaluating database performance in research contexts. The Yahoo! Cloud Serving Benchmark (YCSB) provides a standardized methodology for assessing throughput and latency across different workload patterns [4]. A typical benchmarking protocol includes:

- Infrastructure Setup: Deployment in target region (e.g., Tokyo) with consistent hardware specifications

- Data Scaling: Initial dataset of 200M rows with 10M operations per execution

- Warm-up Phase: 1-hour warm-up time to stabilize performance measurements

- Execution Phase: 30-minute measurement window post warm-up

- Workload Variation: Testing across different read/write ratios (50/50 to 99/1)

- Metrics Collection: P50/P99 latency measurements and throughput in operations per second (OPS)

This methodology revealed that AlloyDB consistently delivered the lowest P50 and P99 latencies across all workloads, while CockroachDB showed higher P99 variance, indicating occasional latency spikes under heavy load [4].

Validation of Digital Morphology Analyzers

According to International Council for Standardization in Hematology (ICSH) guidelines, DM analyzer validation should include [3]:

- Precision and Accuracy Assessment: Comparison against manual differential counts by experienced technologists

- Reproducibility Testing: Evaluation across multiple operators and instruments

- Linearity Verification: Testing across analytical measurement range

- Carryover Contamination Checks: Ensuring sample-to-sample integrity

- Reference Interval Verification: Confirming established clinical ranges

- Method Comparison: Correlation with existing validated methods

These protocols help address limitations in recognizing rare and dysplastic cells, where algorithmic performance varies significantly and affects diagnostic reliability [3].

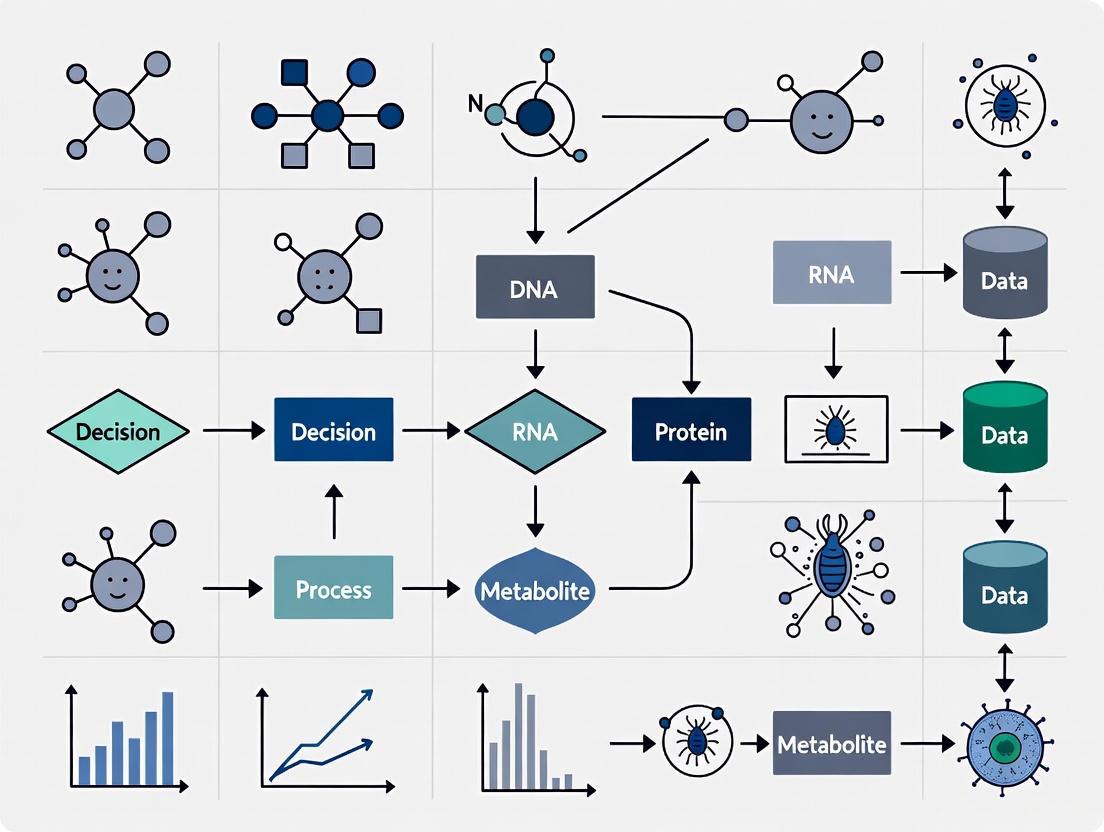

Architectural Workflows and System Diagrams

Digital Morphology Analysis Pipeline

The workflow for digital morphology analysis involves sequential steps from sample preparation to clinical reporting, with critical quality control checkpoints to ensure analytical validity.

Digital Morphology Analysis Workflow: This pipeline shows the integrated human-machine process for analyzing blood specimens, with critical quality control points at slide preparation, staining, and AI classification stages [3].

Vector Search Architecture for Morphological Data

Vector databases enable content-based image retrieval for morphological specimens by transforming images into mathematical representations and performing similarity searches in high-dimensional space.

Vector Search Architecture: This diagram illustrates the computational pipeline for content-based image retrieval in morphological databases, showing how raw images are transformed into searchable vector representations [1].

Successful implementation of digital morphology databases requires specific computational tools and resources. The following table details essential components for establishing a robust digital morphology research pipeline.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Digital Morphology

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vector Databases [1] | Milvus, Pinecone, Weaviate, Qdrant | High-dimensional similarity search | Choose based on scalability needs, metadata filtering, and hybrid search capabilities |

| Digital Morphology Analyzers [3] | CellaVision, Sysmex DI-60, Mindray MC-80 | Automated cell classification and analysis | Consider throughput, stain compatibility, and rare cell detection performance |

| AI/ML Frameworks [5] | CellCognition, Deep Learning Modules | Feature extraction and phenotype annotation | Evaluate based on novelty detection capabilities and training data requirements |

| Data Management Platforms [2] | MorphoBank, specialized repositories | Phylogenetic matrix management and media archiving | Assess collaboration features and data publishing workflows |

| Benchmarking Tools [4] | YCSB, custom validation protocols | Performance validation and comparison | Implement standardized testing across multiple workload patterns |

The digitization of morphological specimens has created powerful new paradigms for research and training. Vector databases like Milvus and Weaviate excel in similarity search and machine learning applications, while specialized platforms like MorphoBank provide domain-specific functionality for phylogenetic research [1] [2]. Digital morphology analyzers such as CellaVision and Sysmex systems offer automated cellular analysis but still require expert verification for complex cases [3]. Selection criteria should prioritize analytical needs, with vector databases chosen for embedding-based retrieval and specialized platforms selected for domain-specific workflows. As these technologies evolve, increased integration between vector search capabilities and domain-specific platforms will likely enhance both research efficiency and diagnostic precision in morphological studies.

This guide objectively compares three key data standards—Darwin Core, ABCD, and Audubon Core—evaluating their performance and applicability for managing digital specimen data in morphology training research.

For researchers in drug development and morphology, selecting the right data standard is crucial for integrating disparate biological specimen data. The table below provides a high-level comparison of the three standards to guide your choice.

| Feature | Darwin Core (DwC) | Access to Biological Collection Data (ABCD) | Audubon Core (AC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Sharing species occurrence data (specimens, observations) [6] | Detailed representation of biological collection specimens [7] [8] | Describing biodiversity multimedia and associated metadata [9] |

| Structural Complexity | Relatively simple; offers both flat ("Simple") and relational models [6] | High; a comprehensive, complex schema designed for detailed data [8] | Moderate; acts as an extension to DwC, reusing terms from other standards [9] |

| Adoption & Use Cases | Very widespread; used by GBIF, iDigBio, and Atlas of Living Australia for data aggregation [7] [10] [11] | Used by institutions requiring detailed specimen descriptions; can be mapped to DwC for publishing [8] | Used to describe multimedia; applicable to 2D images and 3D models (e.g., from CT scans) [9] |

| Best Suited For | Rapid data publishing, aggregation, and integration for large-scale ecological and biogeographic studies [6] [10] | Capturing and preserving the full complexity and provenance of specimens within institutional collections [7] [8] | Managing digital media assets (images, 3D models) derived from specimens, ensuring rich metadata is retained [9] |

Darwin Core

Darwin Core is a standard maintained by Biodiversity Information Standards (TDWG). Its mission is to "provide simple standards to facilitate the finding, sharing and management of biodiversity information" [6]. It consists of a glossary of terms (e.g., dwc:genus, dwc:eventDate) intended to provide a common language for sharing biodiversity data, primarily focusing on taxa and their occurrences in nature as documented by specimens, observations, and samples [6] [12]. Its simplicity and flexibility have led to its widespread adoption by global infrastructures like the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), which indexes hundreds of millions of Darwin Core records [6] [10].

Access to Biological Collection Data (ABCD)

ABCD is a more comprehensive TDWG standard designed for detailed data about biological collections. It is a complex schema that can capture the full depth of information associated with preserved specimens [7] [8]. While ABCD is a powerful standard for data storage and exchange between specialized collections, its complexity can be a barrier for some applications. Consequently, data are often mapped to the simpler Darwin Core standard for broader publishing and aggregation through portals like GBIF [8].

Audubon Core

Audubon Core is a standard and Darwin Core extension for describing biodiversity multimedia, such as images, videos, and audio recordings [9]. It is not an entirely new vocabulary but borrows and specializes terms from established standards like Dublin Core and Darwin Core. Its relevance has grown with new digitization techniques, as it can be used to describe the metadata of 3D data files generated from methods like surface scanning (laser scanners), volumetric scanning (microCT, MRI), and photogrammetry [9]. This makes it directly applicable to morphology research that relies on digital assets.

Experimental Protocols and Data Integration

Research in digital morphology often depends on integrating data from multiple sources and standards. The following workflow, titled "3D Morphology Data Integration," diagrams a typical pipeline from physical specimen to generated data.

Protocol: Generating and Publishing 3D Morphology Data

The methodology below, critical for creating FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data for morphology training, draws from community best practices for 3D digital data publication [13].

Step 1: Specimen Imaging and Raw Data Capture

- Action: Generate 3D digital data using modalities like micro-CT scanning (for internal morphology) or laser scanning/photogrammetry (for surface topology) [13].

- Data Output: The essential data produced is the full-resolution image stack (e.g., TIFF files for tomography) or the original capture data (e.g., point clouds for laser scanning, photographs for photogrammetry) [13].

- Standards Context: At this stage, data are not yet standardized, but the imaging device's metadata is recorded.

Step 2: Data Processing and Model Generation

- Action: Process the raw data to create usable 3D models. This involves segmenting image stacks to differentiate structures and generating surface or volume mesh models [13].

- Data Output: The key outputs are the final 3D models used in analysis (e.g., in STL or PLY format) and, as best practice, the prepared dataset (e.g., segmented image stacks) [13].

Step 3: Metadata Assignment and Standardization

- Action: Describe the digital specimen and its creation process using standard vocabularies.

- Data Output: A text file with critical metadata, including:

- Specimen Information: Link to the physical specimen via repository and accession number [13].

- Acquisition Parameters: Scanner settings, resolution, voxel size, and techniques used to produce the 3D models [13].

- Standards Application: Audubon Core is used to describe the digital media file (e.g., its format, creation method). Darwin Core is used to describe the biological occurrence (e.g., taxonomic identification, collection location). For highly detailed specimen data, ABCD may be used at the source.

Step 4: Data Integration and Publishing

- Action: Package and deposit the data into a repository. The 3D model files and their associated metadata are published together under a persistent identifier (e.g., a DOI) [13].

- Standards Application: A Darwin Core Archive can bundle the core specimen data with an extension using Audubon Core terms to describe the 3D media file. This allows the integrated dataset to be discovered through aggregators like GBIF [9] [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

For researchers conducting or utilizing experiments in digital morphology, the following tools and data components are essential.

| Item/Reagent | Critical Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Physical Voucher Specimen | Provides the ground-truth biological material. Essential for validating digital models and for future morphological or genetic study. Must be housed in a recognized collection with a stable accession number [7] [13]. |

| High-Resolution 3D Scanner (micro-CT, MRI) | Generates the primary 3D data. micro-CT is ideal for hard tissues (bone, teeth), while MRI is used for soft tissues. The choice directly impacts the resolution and type of morphological data acquired [13]. |

| Segmentation & Modeling Software | Enables the transformation of raw image stacks into 3D mesh models. Software like Avizo or SPIERS is used to isolate specific anatomical structures from the surrounding data, creating the models used in analysis [13]. |

| Standardized Metadata File | A text file documenting the entire data generation process. This is critical for reproducibility and data reuse. It allows other scientists to understand the limitations of the data and replicate the methodology [13]. |

| Data Repository (e.g., MorphoSource) | A dedicated platform for long-term storage and access to 3D data. Repositories ensure data preservation, assign DOIs for citation, and facilitate sharing under clear usage licenses, making data FAIR [13]. |

Performance Analysis and Discussion

Quantitative Data on Standard Implementation

The performance of a data standard can be inferred from its adoption rates and the volume of data it supports. The table below summarizes key metrics.

| Performance Metric | Darwin Core | ABCD | Audubon Core |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated Specimen Records | ~1.3 Billion+ (e.g., in GBIF) [8] | Data often mapped to DwC for publishing; precise count not specified in results. | Not typically measured in specimen counts, but in associated media files. |

| U.S. Digitization Progress | ~121 Million records in iDigBio (30% of estimated U.S. holdings) [10] | Information not available in search results. | Information not available in search results. |

| Implementation Flexibility | High: Can be implemented as simple spreadsheets (CSV), XML, or RDF [6] [12]. | Lower: Defined as a comprehensive XML schema, making it more complex [8]. | Moderate: Functions as an extension, inheriting DwC's flexibility [9]. |

Critical Interpretation of Performance Data

Interoperability vs. Complexity: The data shows a clear trade-off. Darwin Core's simplicity is a key driver behind its massive adoption, enabling the aggregation of over a billion records [8]. However, this simplicity can force a loss of detail, as complex data must be simplified for publication. ABCD excels at preserving data richness and provenance but at the cost of ease of use and direct interoperability at a global scale [7] [8].

The Role of Extensions: Audubon Core demonstrates how the limitations of one standard can be addressed by another. DwC alone is insufficient for describing complex multimedia. Using AC as an extension creates a powerful combination where DwC handles the "what, where, when" of the specimen, and AC handles the "how" of the digital representation [9]. This modular approach is likely the future of biodiversity data standards.

Fitness for Morphology Training: For machine learning and morphology training pipelines, data consistency and rich metadata are paramount. While DwC provides the easiest route to amassing large datasets, the critical metadata about 3D model creation (e.g., scanner settings, resolution) is best handled by Audubon Core. Therefore, the most robust data pipeline for advanced research would capture data using ABCD or similar detailed internal standards, then publish a streamlined version enriched with Audubon Core metadata via Darwin Core for global integration [10] [14].

In the evolving landscape of morphology training and research, the digital specimen has become a fundamental resource. A high-quality digital specimen is not merely a scanned image; it is a complex data object integrating high-resolution image data, rich structured metadata, and detailed provenance information. This integrated approach transforms static images into dynamic, computable resources that can power advanced research in drug development and morphological sciences. The transition to digital workflows in pathology and morphology has catalyzed the development of novel machine-learning models for tissue interrogation, enabling the discovery of disease mechanisms and comprehensive patient-specific phenotypes [15]. The quality of these digital specimens directly determines their fitness for purpose in research and clinical applications, making the understanding of their core components essential for researchers and scientists.

Core Components of Digital Specimens

Image Data: Resolution, Format, and Quality

The image data itself forms the visual foundation of any digital specimen. Quality is determined by multiple technical factors including resolution, color depth, and file format. Whole Slide Images (WSI), which can now be scanned in less than a minute, serve as effective surrogates for traditional microscopy [15]. These images represent the internal structure or function of an anatomic region in the form of an array of picture elements called pixels or voxels [16].

Pixel depth, the number of bits used to encode information for each pixel, determines the detail with which morphology can be depicted [16]. With clinical radiological images like CT and MR typically having a gray scale photometric interpretation, and nuclear medicine images like PET and SPECT often displayed with color maps, the technical specifications directly impact research utility [16].

The file format determines how image data is organized and interpreted. In medical imaging, several formats prevail, each with distinct strengths. The Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) standard provides a comprehensive framework including a metadata model, file format, and transmission protocol, widely used in healthcare environments [17]. Other research-focused formats like Nifti and Minc offer specialized capabilities for analytical workflows [16].

Metadata: Context and Machine-Readability

Metadata—text-based elements that describe the medical photograph or associated clinical information—provides essential context to ensure proper interpretation [17]. Without robust metadata, even the highest resolution image has limited research value.

Metadata in medical imaging encompasses technical parameters (how the image was acquired), clinical context (anatomy, patient information), and administrative data [17]. For pathology specimens, this might include information about staining protocols, magnification, and specimen preparation techniques. The DICOM standard represents a sophisticated metadata framework that has been successfully adopted across healthcare, with recent drives toward enterprise imaging strategies expanding its use beyond radiology and cardiology to all specialties acquiring digital images [17].

The emergence of standards like Minimum Information about a Digital Specimen (MIDS) reflects broader efforts to harmonize metadata practices across domains [18]. Such frameworks help clarify what constitutes sufficient documentation for digital specimens, ensuring they remain useful for the widest range of research purposes.

Provenance: Traceability and Authenticity

Provenance documentation provides the historical trail of a digital specimen, tracking its origin and any transformations throughout its lifecycle. This includes details about the specimen collection, preparation protocols, digitization processes, and any subsequent analytical procedures applied. In research contexts, particularly for regulatory purposes in drug development, robust provenance is essential for establishing data integrity and reproducibility.

Provenance information enables researchers to assess fitness-for-purpose of specific specimens for their research questions and provides critical context for interpreting analytical results. The development of structured frameworks for representing provenance alongside image data and metadata represents an advancing area in digital pathology and computational image analysis [15].

Comparative Analysis of Digital Specimen Databases and Standards

Database and Standards Comparison

The landscape of digital specimen management encompasses several specialized databases and standards, each designed with particular use cases and capabilities.

Table 1: Comparison of Digital Specimen Databases and Standards

| Database/Standard | Primary Focus | Metadata Model | Query Capabilities | Representative Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAIS (Pathology Analytic Imaging Standards) [19] | Pathology image analysis | Relational data model | Metadata and spatial queries | Breast cancer studies (4,740 cases), algorithm validation (66 GB), brain tumor studies (365 GB) |

| DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) [17] [16] | Medical image management and communication | Comprehensive metadata model | Workflow services, transmission protocol | Enterprise imaging, radiology, cardiology, expanding to all medical specialties |

| MIDS (Minimum Information about a Digital Specimen) [18] | Natural science specimens | Minimum information standard | Fitness-for-purpose assessment | Biodiversity collections, digitization reporting, specimen prioritization |

| TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) [20] | Cancer research | Multi-modal data integration | Cross-domain queries | PANDA challenge (prostate cancer), cancer biomarker discovery |

| CAMELYON Datasets [20] | Metastasis detection | Structured annotations | Lesion-level and patient-level queries | Breast cancer lymph node sections, metastasis detection algorithms |

Image File Format Comparison

The choice of file format significantly impacts what can be done with a digital specimen in research contexts. Different formats offer varying balances of image fidelity, metadata capacity, and analytical suitability.

Table 2: Medical and Research Image File Formats Comparison

| Format | Header Structure | Data Types Supported | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DICOM [16] | Variable length binary | Signed/unsigned integer (8-, 16-bit; 32-bit for radiotherapy) | Comprehensive metadata, workflow services, widely adopted in healthcare | Float not supported, complex implementation |

| Nifti [16] | Fixed-length (352 byte) | Signed/unsigned integer (8-64 bit), float (32-128 bit), complex (64-256 bit) | Extended header mechanism, comprehensive data type support | Primarily neuroimaging focus |

| TIFF [21] | Flexible | Varies by implementation | Lossless compression, suitable for high-quality prints and scans | Large file sizes, limited metadata structure |

| PNG [21] | Fixed | Varies by implementation | Lossless compression, transparency support, web-friendly | Not ideal for high-resolution photos or print projects |

| JPEG [21] | Fixed | Varies by implementation | Small file size, widely compatible, good for photos | Lossy compression, quality degradation with editing |

Experimental Protocols for Digital Specimen Analysis

Whole Slide Image Analysis Workflow

The analytical workflow for digital specimens in morphology research follows a structured pathway from specimen preparation through computational analysis. The following diagram illustrates this research pipeline:

Title: Digital Specimen Research Pipeline

Methodological Details: The process begins with specimen collection and tissue preparation, where biological samples are obtained and prepared using standardized protocols [15]. This is followed by slide digitization using whole-slide scanners capable of producing high-magnification, high-resolution images within minutes [19] [15]. Quality control addresses potential artifacts including out-of-focal plane issues and ensures diagnostic quality [15]. The metadata annotation phase incorporates both technical metadata (scanning parameters, resolution) and clinical context (anatomy, staining protocols) [17]. Data management leverages specialized databases like PAIS that can handle the vast amounts of data generated—reaching hundreds of gigabytes in research studies [19]. Computational analysis employs machine learning and deep learning techniques to extract features, patterns, and information from histopathological subject matter that cannot be analysed by human-based image interrogation alone [15].

Database Performance Benchmarking

Experimental evaluation of digital specimen databases involves multiple performance dimensions. The PAIS database implementation demonstrated capability to manage substantial data volumes, with benchmarks showing:

- TMA database: 4,740 breast cancer cases occupying 641 MB storage

- Algorithm validation database: 18 selected slides with markups and annotations using 66 GB storage

- Brain tumor study database: 307 TCGA slides utilizing 365 GB storage [19]

These databases supported a wide range of metadata and spatial queries on images, annotations, markups, and features, providing powerful query capabilities that would be difficult or cumbersome to support through other approaches [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The effective utilization of digital specimens in morphology research requires a suite of specialized tools and platforms. The following table details key resources and their research applications.

Table 3: Essential Digital Pathology Research Tools and Resources

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Slide Scanners [15] | Hardware | Converts glass slides to high-resolution digital images | Creation of digital specimens for analysis and archiving |

| PAIS Database [19] | Data Management System | Manages pathology image analysis results and annotations | Supporting spatial and metadata queries on large-scale pathology datasets |

| DICOM Standard [17] [16] | Interoperability Framework | Ensures consistent image formatting and metadata structure | Enabling enterprise-wide image management and exchange |

| Computational Image Analysis [15] | Analytical Methodology | Extracts quantitative data from digital images | Feature detection, segmentation, and classification of morphological structures |

| Digital Pathology Datasets [20] | Reference Data | Provides annotated images for algorithm training and validation | Benchmarking machine learning models (e.g., PANDA, CAMELYON) |

| Deep Learning Models [15] | Analytical Tool | Performs complex pattern recognition on image data | Automated detection, classification, and prognostication from histology |

The comparative analysis of digital specimen components reveals a complex ecosystem where image data quality, metadata richness, and provenance tracking collectively determine research utility. For researchers and drug development professionals, selection of appropriate standards and databases must align with specific research objectives. DICOM provides robust clinical integration for healthcare environments, while specialized research databases like PAIS offer advanced query capabilities for analytical workflows. The emergence of whole slide imaging and computational image analysis has positioned pathology at the forefront of efforts to redefine disease categories through integrated analysis of morphological patterns. As these technologies continue to evolve, the comprehensive anatomical understanding embodied in high-quality digital specimens will play an increasingly central role in personalized medicine and targeted therapeutic development.

In the evolving landscape of biodiversity informatics, digital specimen databases have become indispensable tools for morphological research and training. These aggregated portals provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with unprecedented access to standardized specimen data, enabling large-scale comparative analyses that were previously impossible. Within this ecosystem, three platforms stand out for their distinctive roles and capabilities: the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), which operates as an international network; the Integrated Digitized Biocollections (iDigBio), serving as the U.S. national coordinating center; and the Atlas of Living Australia (ALA), representing a mature national biodiversity data infrastructure. This guide objectively compares the scope, data architecture, and research applications of these critical platforms within the context of digital morphology training and specimen-based research, providing experimental data and methodological frameworks for their effective utilization.

Institutional Profiles and Primary Missions

GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility): An international network and data infrastructure funded by world governments to provide open access data about all life on Earth. Its primary mission is to make biodiversity data openly accessible to anyone, anywhere, supporting scientific research, conservation, and sustainable development [22].

iDigBio (Integrated Digitized Biocollections): Created as the U.S. national coordinating center in 2011 through the National Science Foundation's Advancing Digitization of Biodiversity Collections (ADBC) grant. iDigBio's mission focuses on promoting and catalyzing the digitization, mobilization, and use of biodiversity specimen data through training, open data, and innovative applications. Based at the University of Florida with Florida State University and the University of Kansas as subawardees, it specifically serves as a GBIF Other Associate Participant Node [23].

ALA (Atlas of Living Australia): A national biodiversity data portal that aggregates and provides open access to Australia's biodiversity data. While the search results do not contain extensive details about ALA, it is referenced as a significant data source in global biodiversity research workflows, particularly in the BeeBDC dataset compilation study [24].

Quantitative Data Comparison

Table 1: Comparative quantitative data for biodiversity aggregators

| Platform | Spatial Scope | Specimen Records | Media Files | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBIF | Global | Not specified in results | Not specified | International network of governments and institutions [22] |

| iDigBio | U.S. National Hub | >143 million records | >57 million media files | >1,800 recordsets from U.S. collections [23] |

| ALA | Australia | Part of >18.3 million bee records aggregated in study [24] | Not specified | Australian biodiversity institutions and collections [24] |

Table 2: Functional characteristics and research applications

| Platform | Primary Focus | Key Strengths | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| GBIF | Global data infrastructure | Cross-disciplinary research support, international governance | Climate change impacts, invasive species, human health research [22] |

| iDigBio | U.S. specimen digitization | Digitization training, specimen imaging, georeferencing | Morphological studies, collections-based research, digitization protocols [23] [25] |

| ALA | Australian biodiversity | National data aggregation, regional completeness | Regional conservation assessments, taxonomic studies [24] |

Experimental Data and Research Applications

Case Study: Large-Scale Bee Occurrence Data Integration

A 2023 study published in Scientific Data provides empirical evidence of how these platforms function within an integrated research workflow. The research aimed to create a globally synthesized and cleaned bee occurrence dataset, combining >18.3 million bee occurrence records from multiple public repositories including GBIF, iDigBio, and ALA, alongside smaller datasets [24].

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Sourcing: Records were downloaded from GBIF (August 14, 2023), iDigBio (September 1, 2023), and ALA (September 1, 2023) on a per-family basis

- Data Processing: Implementation of the BeeBDC R package workflow for standardization, flagging, deduplication, and cleaning

- Taxonomic Harmonization: Species names were standardized following established global taxonomy using Discover Life website data

- Quality Control: Record-level flags were added for potential quality issues, creating both "cleaned" and "flagged-but-uncleaned" dataset versions [24]

Results and Performance Metrics: The integration process yielded a final cleaned dataset of 6.9 million occurrences from the initial 18.3 million records, demonstrating the substantial data curation required when working with aggregated biodiversity data. The study highlighted that each platform contributed significant volumes of data but required substantial cleaning and standardization for research readiness [24].

Digital Morphology and Imaging Workflows

The adoption of whole-slide imaging (WSI) scanners and digital microscopy has transformed morphological research, creating new opportunities for integrating specimen data with high-resolution imagery. Technical considerations for digital morphology include:

- Scanning Specifications: Modern scanners capture images at 20× and 40× magnification, with 40× scans producing files approximately 4 times larger than 20× scans. Higher resolutions (60×/63× or 100×) are recommended for specialized applications like blood smears [26]

- File Management: The JPEG2000 compression scheme represents the current standard for WSI, based on discrete wavelet transforms that provide optimal compression-to-quality ratios [26]

- Data Integration: Platforms like iDigBio specifically accommodate associated images, audio, and video files, with over 57 million media files currently available through their portal [23]

Diagram 1: Data flow and relationships between aggregators in morphological research

Methodological Framework for Researchers

Data Quality Assessment Protocol

When utilizing these platforms for morphological research, implementing a systematic data quality assessment is essential:

- Provenance Tracking: Document the original source of each record, as aggregators like GBIF and iDigBio often contain overlapping but not identical datasets [27]

- Taxonomic Harmonization: Standardize species names using authoritative taxonomic backbones, as demonstrated in the bee dataset study where names were harmonized following Discover Life taxonomy [24]

- Spatial Validation: Implement coordinate checks for accuracy and precision, including tests for coordinate outliers and country code consistency

- Temporal Validation: Verify collection dates for chronological plausibility and internal consistency

- Duplicate Detection: Identify and merge duplicate records across platforms using specimen codes, coordinates, and taxonomic information [24]

Digitization Workflow Standards

The digitization process follows established workflows that ensure data quality and interoperability:

- Pre-digitization Curation: Includes specimen preparation and assignment of unique identifiers that persist through the digitization pipeline [28]

- Image Capture: Requires careful planning of work sequences, hardware selection, and storage solutions [28]

- Data Capture: The core process of transcribing specimen information into digital formats, increasingly utilizing advanced data entry technologies beyond manual keyboard entry [28]

- Georeferencing: Extracting accurate geographical information from collection records, which is particularly important for ecological and morphological studies [28]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential tools and platforms for biodiversity data management

| Tool Category | Specific Solution | Function in Research | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Aggregation | GBIF API | Programmatic access to global occurrence data | Downloading bee records by taxonomic family [24] |

| Data Cleaning | BeeBDC R Package | Reproducible workflow for data standardization, flagging, and deduplication | Processing >18.3 million bee records from multiple aggregators [24] |

| Digital Imaging | Whole Slide Imaging (WSI) Scanners | Digitization of histology slides for quantitative analysis | Creating virtual slides viewable at multiple magnifications [26] |

| Taxonomic Harmonization | Discover Life Taxonomy | Authoritative taxonomic backbone for name standardization | Harmonizing species names across aggregated bee records [24] |

| Data Publishing | Hosted Portals (GBIF) | Customizable websites for specialized data communities | Thematic portals for national or institutional data [22] |

| Digitization Training | iDigBio Digitization Academy | Professional development for biodiversity digitization | Course on databasing, imaging, and georeferencing protocols [25] |

The complementary roles of iDigBio, GBIF, and ALA create a robust infrastructure for digital morphology research, each contributing distinctive strengths to the scientific community. iDigBio excels as a national center for specimen digitization standards and training with deep specimen imaging expertise. GBIF provides unparalleled global scale and cross-disciplinary data integration capabilities. ALA represents a model for comprehensive national biodiversity data aggregation. For researchers focused on morphological training and analysis, success depends on understanding the specific strengths, data quality considerations, and interoperability frameworks of each platform, while implementing rigorous data validation protocols that acknowledge the specialized nature of morphological data. The continuing development of tools like the BeeBDC package and standardized digitization workflows promises to further enhance the research utility of these critical biodiversity data aggregators.

The Extended Specimen Concept (ESC) represents a transformative framework in biodiversity science, shifting the perspective of a museum specimen from a singular physical object to a dynamic hub interconnected with a vast array of digital data and physical derivatives [29]. This approach reframes specimens as foundational elements for integrative biological research, linking morphological data with genomic, ecological, and environmental information to address complex questions about life on Earth [29]. The ESC facilitates the exploration of life across evolutionary, temporal, and spatial scales by creating a network of associations—the Extended Specimen Network (ESN)—that connects primary specimens to related resources such as tissue samples, gene sequences, isotope analyses, field photographs, and behavioral observations [29]. This paradigm supports critical research areas including responses to environmental change, zoonotic disease transmission, sustainable resource use, and crop resilience [29]. For morphology training and research, particularly in fields like parasitology where access to physical specimens is diminishing due to improved sanitation, digital extensions such as virtual slides provide indispensable resources for education and ongoing discovery [30].

Comparative Analysis of Digital Specimen Database Architectures

Digital specimen databases form the technological backbone of the Extended Specimen Concept. These systems vary in architecture, data integration capabilities, and user interfaces, directly influencing their utility for morphological research and training. The following comparison examines three distinct models.

Table 1: Comparison of Digital Specimen Database Architectures

| Database Feature | Extended Specimen Network (ESN) | Preliminary Digital Parasite Specimen Database | MCZbase (Museum of Comparative Zoology) | High Throughput Experimental Materials (HTEM) Database |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Integrating biodiversity data across collections [29] | Parasitology education and morphology training [30] | Centralizing specimen records for a natural history museum [31] | Inorganic materials science and data mining [32] |

| Core Data Types | Physical specimens, genetic sequences, trait data, images, biotic interactions [29] | Virtual slides of parasite eggs, adults, arthropods; explanatory notes [30] | Georeferenced specimen records, digital media, GenBank links [31] | Synthesis conditions, chemical composition, crystal structure, optoelectronic properties [32] |

| Data Integration Mechanism | Dynamic linking via system of identifiers and tracking protocols [29] | Folder organization by taxon; server-based sharing [30] | Centralized database conforming to natural history standards [31] | Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) with API [32] |

| User Interface & Accessibility | Planned interfaces for diverse users, including dynamic queries [29] | Web-based; accessible to ~100 users simultaneously [30] | Searchable for researchers and public; supports global collaborations [31] | Web interface with periodic table search; API for data mining [32] |

| Impact on Morphology Training | Potential for object-based learning combined with digital data literacy [29] | Direct resource for practical training in parasite identification [30] | Enhances documentation through researcher collaboration [31] | Not directly applicable to biological morphology |

The ESN architecture is designed for maximum interoperability, aiming to create a decentralized network where data from many institutions can be dynamically linked [29]. In contrast, the Parasite Database and MCZbase represent more centralized models, with the former being highly specialized for a single educational purpose and the latter serving the needs of a single institution while contributing data to larger networks like the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) [30] [31]. The HTEM database, while from a different field (materials science), illustrates the power of a high-throughput approach and dedicated data infrastructure for generating large, machine-learning-ready datasets, a model that could inform future developments in biodiversity informatics [32].

Experimental Protocols for Extended Specimen Data Generation

The implementation of the Extended Specimen Concept relies on rigorous methodologies for generating, managing, and linking diverse data types. The following protocols are critical for building a robust Extended Specimen Network.

Digitization and Virtual Slide Creation

This protocol is essential for creating high-fidelity digital surrogates of physical specimens, particularly for morphology training.

- Specimen Curation and Selection: Acquire and curate physical specimens (e.g., microscope slides of parasite eggs, adults, and arthropods) from established collections. Ensure specimens represent key taxonomic groups and morphological features [30].

- High-Resolution Slide Scanning: Employ whole-slide scanning technology to capture digital images of specimens. The process must successfully scan diverse elements, from large structures (e.g., ticks observed under low magnification) to minute details (e.g., malarial parasites under high magnification) [30].

- Data Annotation and Curation: Attach multilingual explanatory notes (e.g., in English and Japanese) to each digital specimen. Organize the resulting virtual slides into a logical structure, such as folders arranged by taxon, to facilitate navigation and learning [30].

- Database Integration and Deployment: Compile the annotated virtual slides into a digital database. Host the database on a shared server capable of supporting simultaneous access by numerous users (e.g., ~100 individuals), enabling its use in practical training and research across institutions [30].

Data Integration via a Centralized Museum Database

This protocol outlines the process for moving from legacy systems to an integrated, standards-compliant database for museum collections.

- Legacy Data Migration: Consolidate specimen records from multiple independent, legacy sources (e.g., separate databases for different collections) into a single, centralized database [31].

- Standards Conformance and Enhancement: Ensure the new database conforms to recognized standards for natural history collections (e.g., those facilitating collaboration with GBIF and the Encyclopedia of Life). Implement capabilities for tracking collection management duties and making holdings publicly accessible [31].

- Linking Derived Data: Establish pathways to link various forms of digital media, GenBank data, and other research information directly to the relevant specimen record. This creates the foundational links of an extended specimen [31].

- Researcher Collaboration Framework: Develop guidelines and operational pathways for outside researchers to efficiently contribute specimen information, digital media, and other research data back into the museum database, thereby enhancing specimen documentation [31].

High-Throughput Data Generation and Management

Adapted from materials science [32], this protocol provides a template for the large-scale data generation needed to populate an ESN.

- Combinatorial Sample Generation: Utilize high-throughput methods (e.g., combinatorial physical vapor deposition for materials) to generate large sample libraries. In a biological context, this could translate to systematic imaging or genetic sequencing campaigns.

- Spatially-Resolved Characterization: Apply multiple characterization techniques (e.g., structural, chemical, optoelectronic) to each sample in the library to generate diverse data types for the same source material [32].

- Automated Data Harvesting: Automatically harvest raw data and metadata from synthesis and characterization instruments into a central data warehouse or archive [32].

- Extract-Transform-Load (ETL) Processing: Implement an ETL process to align, clean, and structure the disparate data and metadata into a consistent, object-relational database architecture [32].

- Multi-Channel Data Access: Deploy an Application Programming Interface (API) and a web-based user interface to allow both human-driven data exploration and programmatic access for large-scale data mining and machine learning [32].

Visualization of the Extended Specimen Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for generating and utilizing data within the Extended Specimen Network, from physical object to research and educational application.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing the Extended Specimen Concept requires a suite of technological and informatics "reagents." The following table details key components essential for constructing and utilizing a functional Extended Specimen Network.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Extended Specimen Research

| Tool or Resource | Primary Function | Role in Extended Specimen Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Whole-Slide Scanner | Creates high-resolution digital images of physical specimens (e.g., microscope slides) [30]. | Generates the core digital morphological data for education and remote verification of species identification [29] [30]. |

| Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) | Manages laboratory data, samples, and associated metadata throughout the research lifecycle [32]. | Provides the backbone for data tracking, from specimen collection through data generation, ensuring data integrity and provenance [32]. |

| Centralized Specimen Database (e.g., MCZbase) | A unified repository for specimen records, digital media, and genomic links conforming to collection standards [31]. | Serves as the primary hub for storing and managing core specimen data and its initial digital extensions [31]. |

| Persistent Identifier System | Provides unique, resolvable identifiers for specimens, samples, and data sets (e.g., DOIs) [29]. | Enables dynamic, reliable linking of all extended specimen components across physical and digital spaces, crucial for interoperability and attribution [29]. |

| Application Programming Interface (API) | Allows for programmable, automated communication between software applications and databases [32]. | Facilitates data mining, large-scale analysis, and machine learning by providing standardized access to the database contents [32]. |

| Global Biodiversity Data Portals (e.g., GBIF, iDigBio) | Aggregate and provide access to biodiversity data from thousands of institutions worldwide [29] [31]. | Enables large-scale, cross-collection research and provides the infrastructure for building a distributed network like the ESN [29]. |

The Extended Specimen Concept represents a fundamental evolution in how biodiversity specimens are conceptualized and utilized. By integrating traditional morphology with genomics, ecology, and other data domains through digital networks, the ESC creates a powerful, multifaceted resource for scientific inquiry. The comparative analysis of database architectures reveals that while specialized resources are vital for focused training, the future lies in interoperable networks that leverage common standards and persistent identifiers. The experimental protocols and tools detailed herein provide a roadmap for researchers and institutions to contribute to and benefit from this expanding framework. As these networks grow, they will continue to transform our ability to document, understand, and preserve biological diversity in an increasingly data-driven world.

Integrating Digital Databases into Morphology Training Workflows

The emergence of sophisticated digital specimen databases is fundamentally transforming morphology training and research. These resources provide unprecedented access to detailed three-dimensional morphological data, enabling a shift from traditional, hands-on specimen examination to interactive, data-driven exploration. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, mastering these tools is no longer optional but essential for maintaining competitive advantage. The digital era in morphology, fueled by advances in non-invasive imaging techniques like micro-computed tomography (μCT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), allows for high-throughput analyses of whole specimens, including valuable museum material [33]. This transition presents a critical challenge for curriculum design: effectively integrating these powerful digital resources to maximize research outcomes and foster robust morphological understanding. This guide provides a structured comparison of database performance and experimental protocols to inform the development of state-of-the-art digital morphology modules.

Comparative Analysis of Digital Morphology Database Platforms

A diverse ecosystem of digital databases supports morphological research. They can be broadly categorized into specialized repositories for specific data types and general-purpose databases with advanced features suitable for morphological data management. The following comparison outlines key platforms relevant to a morphology curriculum.

Table 1: Comparison of Specialized Morphological & Scientific Databases

| Database Name | Primary Focus | Key Morphological Features | Data Types & Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| NeuroMorpho.Org [34] [35] | Neuronal Morphology | Repository of 3D digital reconstructions of neuronal axons and dendrites; over 44,000 reconstructions identified in literature. | Digital reconstruction files (e.g., .swc); enables morphometric analysis and computational modeling. |

| L-Measure (LM) [35] | Neuronal Morphometry | Free software for quantitative analysis of neuronal morphology; computes >40 core metrics from 3D reconstructions. | Works with digital reconstruction files; online or local execution; outputs statistics and distributions. |

| Surrey Morphology Group Databases [36] | Linguistic Morphology | Covers diverse phenomena (e.g., inflectional classes, suppletion, syncretism) across many languages. | Typological databases; interactive paradigm visualizations; lexical data. |

| MCZbase [31] | Natural History Specimens | Centralized database for over 21-million biological specimens from the Museum of Comparative Zoology. | Specimen records with georeferencing; links to digital media and GenBank data; accessible via GBIF/EOL. |

Table 2: Comparison of General-Purpose Databases with Relevance to Morphology Research

| Database Name | Type | Relevant Features for Morphology Research | AI/Vector Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| PostgreSQL [37] | Relational (Open-Source) | Enhanced JSON support; PostgreSQL 17 offers advanced vector search for high-dimensional data (e.g., from imaging). | Yes |

| MongoDB [37] | NoSQL Document Store | Flexible BSON document storage; advanced vector indexing (DiskANN) for AI workloads. | Yes |

| Apache Cassandra [37] | Distributed NoSQL | Vector data types and similarity functions for scalable AI applications. | Yes |

Experimental Protocols for Validating Digital Morphology Tools

A critical component of integrating digital tools is understanding the experimental evidence that validates their utility and reliability. The following protocols from key studies provide a framework for assessing digital morphology resources.

Protocol: Validation of a Neuronal Morphometry Tool (L-Measure)

Objective: To quantitatively characterize neuronal morphology from 3D digital reconstructions, enabling the correlation of structure with function [35].

Workflow:

- Data Acquisition: Obtain 3D digital reconstructions of neurons. These are typically generated from histological preparations using specialized tracing software (e.g., Neurolucida) and represent neuronal arbors as sequences of interconnected cylinders.

- Tool Operation: Load reconstruction files into L-Measure. The tool can be accessed via a web-based Java interface or downloaded for local execution.

- Specificity Setting: Define the morphological region of interest for analysis (e.g., entire arbor, specific branch order, dendrites only).

- Function Selection: Choose from over 40 morphometric parameters to compute. Core metrics include:

- Branch Geometry: Length, Diameter, Taper, Contraction.

- Topology: Branch Order, Number of Bifurcations, Terminal Degree.

- Spatial Structure: Path Distance from Soma, Euclidian Distance from Soma, Sholl Analysis, Fractal Dimension.

- Branching Patterns: Partition Asymmetry, Rall Ratio.

- Execution and Output: Execute the analysis. L-Measure returns:

- Simple statistics (mean, standard deviation, min, max, total sum).

- Frequency distribution histograms.

- Interrelations between two measures (e.g., Sholl analysis).

- Application: Use the extracted parameters for comparative analysis, computational modeling, or classification of cellular phenotypes.

The diagram below illustrates the structured workflow for using L-Measure in neuronal morphometry analysis.

Protocol: Performance Comparison of AI-Based Analysis Systems

Objective: To compare the diagnostic performance of different versions of an artificial intelligence system for medical image analysis, providing a model for benchmarking digital analysis tools [38].

Workflow:

- Study Design: A retrospective multicenter study was conducted using 187 chest radiographs from six centers.

- Ground Truth Establishment:

- For 49 cases, the ground truth was established by a chest CT performed within a week of the radiograph.

- For the remaining 138 cases, ground truth was determined by consensus from three board-certified general radiologists.

- The final standard reference included 57 positive cases and 130 normal studies.

- Intervention: Each radiograph was analyzed by two versions of the AI system (Gleamer ChestView v1.5.0 and v1.5.4).

- Performance Metrics Calculation: Key metrics including accuracy, precision (positive predictive value), sensitivity (recall), specificity, and F1 score were calculated for each software version.

- Statistical Analysis: Performance metrics between versions were compared to determine statistically significant improvements, such as the increase in overall accuracy from 87.7% to 92.5% and precision from 75.0% to 85.2%.

Protocol: Validation of Digital vs. Optical Morphology

Objective: To evaluate the reliability of digital image analysis compared to classic microscopic morphological evaluation, specifically for bone marrow aspirates [39].

Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: 180 consecutive bone marrow needle aspirate smears were prepared.

- Digitization: All smears were scanned using a "Metafer4 VSlide" whole slide imaging (WSI) digital scanning system.

- Blinded Evaluation: The same morphologists evaluated the slides via both traditional optical microscopy and digital images on a screen.

- Data Collection: For both methods, reviewers assessed:

- Overall cellularity.

- Percentage values of different cell populations (e.g., neutrophilic granulocytes, erythroid series, lymphocytes, blasts).

- Identification of dysplastic features.

- Statistical Comparability: The means and medians of percentage values from both methods were compared. The study found average differences of 0% for key lineages, demonstrating high comparability.

The Researcher's Toolkit for Digital Morphology

Building and utilizing digital morphology modules requires a suite of specific tools and reagents. The table below details essential components for a functional research and training environment.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Digital Morphology

| Tool/Reagent | Function / Purpose | Example in Use |

|---|---|---|

| Digital Reconstruction Files | Standardized format for representing neuronal morphology as interconnected tubules for quantitative analysis. | The .swc file format used by NeuroMorpho.Org and L-Measure [35]. |

| L-Measure Software | Free tool for extracting morphometric parameters from digital reconstructions; enables statistical comparison. | Used to compute branch length, path distance, and fractal dimension from a 3D neuron reconstruction [35]. |

| Contrast Agents (e.g., Iodine, Gadolinium) | Enhance soft tissue visualization for non-invasive imaging techniques like μCT and MRI. | Application to century-old museum specimens to enable digital analysis without physical destruction [33]. |

| Whole Slide Imaging (WSI) System | Digitizes entire microscope slides for preservation, sharing, and remote digital analysis. | The "Metafer4 VSlide" system used to validate digital bone marrow aspirate analysis [39]. |

| Remote Visualization Setup | A data center with large storage and powerful graphics to enable real-time manipulation of large 3D datasets remotely. | Proposed setup for handling GB-sized μCT datasets, allowing analysis on any internet-connected computer [33]. |

Strategic Implementation in Research and Training Curricula

The comparative data and experimental protocols outlined above provide a foundation for integrating digital morphology databases into research and training. The validation of digital analysis tools against traditional methods and ground truth standards builds the confidence necessary for their adoption in critical research and potential diagnostic applications [38] [39]. Furthermore, the ability to re-use shared digital morphologies in secondary applications, such as computational simulations and large-scale comparative studies, dramatically extends the impact and value of original research data [34] [35].

Curriculum modules should, therefore, be designed to achieve the following: First, train researchers to select the appropriate database or tool based on their specific data type and analytical goal, leveraging the comparisons in Tables 1 and 2. Second, provide hands-on experience with the experimental protocols for tool validation, ensuring researchers can critically assess the performance and limitations of digital resources. Finally, foster an understanding of the end-to-end digital workflow—from specimen preparation and digital archiving to quantitative analysis and data sharing—to prepare a new generation of scientists for the future of fully digital morphology.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into clinical and research laboratories is fundamentally transforming cellular morphology analysis. Digital morphology analyzers, which automate the enumeration and classification of leukocytes in peripheral blood and body fluids, have emerged as pivotal tools for enhancing diagnostic precision, standardizing morphological assessment, and building rich digital specimen databases for research and training [40] [41]. These databases are invaluable resources for educating new laboratory scientists and for the development and refinement of AI algorithms themselves. This guide provides an objective comparison of two prominent platforms in this field—the CellaVision DI-60 (often integrated within Sysmex automation lines) and the Sysmex DI-60 system—focusing on their operational principles, analytical performance, and specific utility in a research context centered on morphology database development.

Both the CellaVision DI-60 and the Sysmex DI-60 are automated digital cell morphology systems designed to locate, identify, and pre-classify white blood cells (WBCs) from stained blood smears or body fluid slides. They consist of an automated microscope, a high-quality digital camera, and a computer system with software that acquires and pre-classifies cell images for subsequent technologist verification [42] [43]. This process enhances traceability, allowing researchers to link patient results directly to individual cell images, a critical feature for database curation.

Table 1: Core Technical Specifications at a Glance

| Feature | CellaVision/Sysmex DI-60 |

|---|---|

| Key Technology | Artificial Neural Network (ANN) [44] |

| Throughput (Peripheral Blood) | Up to 30 slides/hour [42] |

| WBC Pre-classification Categories | Up to 18 classes (e.g., segmented neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, blasts, atypical lymphocytes) [45] [43] |

| RBC Morphology Characterization | Yes (e.g., anisocytosis, poikilocytosis, hypochromasia) [46] [43] |

| Body Fluid Analysis Mode | Yes (pre-classifies 8 cell classes) [47] |

| Integration | Can connect with Sysmex XN-series hematology systems for full automation [42] |

Comparative Performance Data from Key Studies

Independent performance evaluations provide critical insights into the operational reliability of these platforms. The data below, derived from recent scientific studies, highlight the systems' strengths and limitations in different clinical and pre-analytical scenarios.

Performance in Peripheral Blood with Abnormal Samples

A 2024 study evaluating the Sysmex DI-60 on 166 peripheral blood samples, including both normal and a range of abnormal cases (e.g., acute leukemia, leukopenia), found a strong correlation with manual microscopy for most major cell types after expert verification [45]. The analysis revealed high sensitivity and specificity for all cells except basophils. The correlation was particularly high for segmented neutrophils, band neutrophils, lymphocytes, and blast cells [45]. A key finding was that the DI-60 demonstrated consistent and reliable analysis of WBC differentials within a wide WBC count range of 1.5–30.0 × 10⁹/L. However, manual review remained indispensable for samples outside this range (severe leucocytosis >30.0 × 10⁹/L or severe leukopenia <1.5 × 10⁹/L) and for enumerating certain cells like monocytes and plasma cells, which showed poor agreement [45].

Performance in Body Fluid Analysis

A March 2024 study specifically assessed the DI-60 for WBC differentials in body fluids (BF) [47]. The study, using five BF samples, each dominated by a single cell type, reported excellent precision for both pre-classification and verification. After verification, the system showed high sensitivity, specificity, and efficiency in neutrophil- and lymphocyte-dominant samples, with high correlations to manual counting (r = 0.72 to 0.94) for major cell types [47]. However, the turnaround time (TAT) was significantly longer for the DI-60 (median 6 minutes 28 seconds per slide) compared to manual counting (1 minute 53 seconds), with the difference being most pronounced in samples containing abnormal or malignant cells [47].

Critical Comparison with an AI-Based Whole-Slide Scanner

A 2025 preprint study provided a direct performance comparison relevant for database comprehensiveness, particularly in challenging leukopenic samples [44]. The study compared the blast cell detection capability of the CellaVision DI-60 (using its standard 200-cell analysis mode) against the Cygnus system, which utilizes a Vision Transformer deep learning architecture and offers a whole-slide scanning (WSI) mode.

Table 2: Blast Detection Performance in Markedly Leucopenic Samples (WBC ≤2.0 × 10⁹/L)

| Analysis Platform and Mode | Number of Blast-Positive Cases Detected (Total=17) | Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|

| CellaVision/Sysmex DI-60 (200-cell mode) | 8 | 47.1% |

| Cygnus System (200-cell mode) | 9 | 52.9% |

| Cygnus System (Whole-slide scanning mode) | 17 | 100% |

This study underscores a fundamental methodological difference. The DI-60's fixed 200-cell counting mode, while efficient, may miss rare pathological cells in severely leukopenic samples due to its limited scanning area. In contrast, WSI-based systems are designed to scan the entire slide, dramatically improving the detection of low-frequency events, which is a critical consideration for building robust morphological databases that include rare cell types [44].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Performance Assessment

To ensure the reproducibility of performance data and guide future validation studies in other research settings, the following section outlines the standard experimental methodologies cited in the comparison.

Protocol for Peripheral Blood Performance Evaluation

The following workflow was adapted from the 2024 study by [45] to assess DI-60 performance across a spectrum of WBC counts.

Workflow for Peripheral Blood Evaluation

- Sample Collection and Preparation: 166 peripheral blood specimens were collected in K₂-EDTA vacuettes. The WBC count of these specimens covered a broad reportable range (0.11–271 × 10⁹/L). The samples were categorized into groups based on their WBC count: moderate/severe leucocytosis (>30.0 × 10⁹/L), mild leucocytosis (10.0–30.0 × 10⁹/L), normal (4.0–10.0 × 10⁹/L), mild leukopenia (1.5–4.0 × 10⁹/L), and moderate/severe leukopenia (<1.5 × 10⁹/L) [45].

- Slide Preparation: Peripheral blood smears were automatically prepared and stained using an SP-10 slide maker/stainer and Wright's staining [45].

- DI-60 Analysis: Slides were loaded into the DI-60, which was set to scan in a battlement-track mode and count 200 cells per slide. The system's pre-classified cell images were subsequently verified by an expert hematologist [45].

- Reference Method (Manual Counting): Following CLSI H20-A2 guidelines, two experienced medical technologists, blinded to the DI-60 results, independently performed a 200-cell differential count on each slide using a light microscope. The average of their counts was used as the reference value [45].

- Statistical Analysis: The agreement between DI-60 (pre-classification and verification) and manual counting was assessed using Bland–Altman plots, Passing–Bablok regression, and calculation of correlation coefficients. Sensitivity, specificity, and other performance metrics were also evaluated [45].

Protocol for Body Fluid Analysis

The following methodology was used by [47] to evaluate the DI-60's performance on body fluids.

- Sample Preparation: Five body fluid samples (pleural fluids and ascites), each dominated (>80%) by a single cell type (neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages, abnormal lymphocytes, or malignant cells), were selected. Slides were prepared using a cytocentrifuge and stained with Wright-Giemsa on an SP-50 stainer [47].

- DI-60 and Manual Analysis: Each of the five BF slides was analyzed 10 consecutive times by the DI-60 operating in its BF mode. The pre-classified results were then verified by an expert. Manual counting of 200 WBCs was performed according to CLSI H56-A guidelines by a single expert [47].

- Turnaround Time (TAT) Assessment: The TAT for the DI-60 was automatically recorded from the system log, including preparation, scanning, pre-classification, and verification time. The TAT for manual counting was recorded with a stopwatch [47].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Building a high-quality digital morphology database requires standardized reagents and equipment to ensure image consistency and analytical reproducibility. The following table details key materials used in the featured experiments.

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Digital Morphology Research

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example from Cited Studies |

|---|---|---|

| K₂-EDTA Tubes | Anticoagulant for hematology samples; prevents clotting and preserves cell morphology for analysis. | Becton Dickinson vacuettes [45]. |

| Automated Slide Maker/Stainer | Standardizes the preparation and Romanowsky-type staining of blood smears, critical for consistent cell imaging. | Sysmex SP-10 or SP-50 systems [45] [47]. |

| Romanowsky Stains | A group of stains (e.g., Wright, May-Grünwald-Giemsa) used to differentiate blood cells based on cytoplasmic and nuclear staining. | Wright's staining (Baso Company) [45], Wright-Giemsa stain [47]. |

| Cytocentrifuge | Concentrates cells from low-cellularity fluids (e.g., body fluids) onto a small area of a slide for microscopic analysis. | Cytospin 4 centrifuge (Thermo Fisher Scientific) [47]. |

| Quality Control Slides | Commercially available or internally curated slides with known cell morphology to validate analyzer performance. | Implied by the use of characterized patient samples for validation [45] [47]. |

Analysis of Technological Foundations and Research Implications

The underlying AI technology directly impacts a platform's utility for research and database development. The CellaVision/Sysmex DI-60 systems utilize an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) for cell pre-classification [44]. This is a form of machine learning that relies on manually engineered feature extraction and pattern recognition. While highly effective for classifying common cell types, its performance can be constrained by its predefined feature set and the fixed area it scans to reach a target cell count (e.g., 200 cells) [44].

The comparative study with the Cygnus system highlights an emerging alternative: Vision Transformer-based Deep Learning [44]. This architecture uses self-attention mechanisms to autonomously learn hierarchical features directly from images, enabling more comprehensive, end-to-end image analysis. When coupled with whole-slide scanning (WSI) instead of a fixed cell count, this approach offers a significant advantage for detecting rare cells, a critical capability for ensuring database comprehensiveness and for applications like minimal residual disease detection [44].

For researchers, the choice involves a key trade-off:

- ANN-based systems (DI-60) offer proven, high-throughput performance for routine differentials and are integrated into automated workflows, making them excellent for building large datasets of common morphologies.

- WSI with advanced DL systems may be better suited for projects where the primary goal is the identification and capture of rare or aberrant cells, as they minimize sampling error by examining the entire slide.

Both the CellaVision and Sysmex DI-60 platforms represent sophisticated tools for automating cell identification and contributing to digital morphology databases. Performance data confirm they deliver reliable and standardized WBC differentials in peripheral blood within a broad WBC count range and in specific body fluid types after expert verification. Their integration into automated laboratory lines enhances efficiency and traceability for large-scale sample processing.