Ensuring Accuracy in Genetic Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide to DNA Barcoding Quality Control and Sequence Validation

This article provides a complete framework for implementing robust quality control and validation protocols in DNA barcoding workflows.

Ensuring Accuracy in Genetic Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide to DNA Barcoding Quality Control and Sequence Validation

Abstract

This article provides a complete framework for implementing robust quality control and validation protocols in DNA barcoding workflows. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, methodological applications, troubleshooting strategies, and comparative validation techniques. By synthesizing current best practices and data-driven guidelines, this guide addresses critical challenges in sequence reliability, database selection, and error mitigation to ensure the integrity of genetic data for biomedical research, species identification, and diagnostic applications. The content emphasizes practical implementation across various sample types and technological platforms, from conventional Sanger sequencing to high-throughput NGS workflows.

The Building Blocks of Reliable DNA Barcoding: Understanding Quality Fundamentals and Common Pitfalls

Fundamental Concepts: Understanding Q Scores and Error Rates

What is a Q Score in next-generation sequencing?

A Quality Score (Q Score) in sequencing is a logarithmic measure that represents the probability that a given base was called incorrectly by the sequencing instrument. It is defined by the equation: Q = -10logâ‚â‚€(e), where e is the estimated probability of an incorrect base call [1]. Higher Q scores indicate a much lower probability of error and therefore higher base-calling accuracy.

How are Q Scores and error rates practically related?

The relationship between Q scores, error probabilities, and base call accuracy is standardized. The following table summarizes key benchmarks [1]:

| Quality Score (Q) | Probability of Incorrect Base Call | Inferred Base Call Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Q20 | 1 in 100 | 99% |

| Q30 | 1 in 1,000 | 99.9% |

| Q10 | 1 in 10 | 90% |

In practice, Q30 is a common benchmark for high-quality data in next-generation sequencing (NGS), as this level of accuracy ensures that virtually all reads are perfect, with no errors or ambiguities [1]. A Q20 score, representing 99% accuracy, is often considered the minimum for many analytical applications.

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Addressing Common Data Quality Issues

1. Why is a high percentage of my data failing the quality filter (e.g., low Q scores)?

Several factors can lead to poor overall read quality [2]:

- Degraded or Impure Starting Material: The quality of your input DNA or RNA is critical. Assess sample integrity and purity before library preparation. For DNA, use spectrophotometry (e.g., NanoDrop) and look for an A260/A280 ratio of ~1.8 or higher. For RNA, an A260/A280 ratio of ~2.0 and a high RNA Integrity Number (RIN) are desirable [2].

- Issues During Library Preparation: Inefficient adapter ligation, over- or under-amplification during PCR, and contamination can all introduce errors and reduce quality. Ensure your library preparation kit is compatible with your sample type and follow protocols meticulously to minimize cross-contamination [2].

- Technical Sequencing Errors: Sequencing instruments can have hardware or software issues mid-run. Monitor run metrics in real-time if possible and contact your platform provider for troubleshooting if you suspect instrument failure [2].

2. My overall yield (number of reads) is lower than expected. What could be the cause?

Low yield can stem from problems at various stages [2]:

- Insufficient or Degraded Input DNA: Quantify your input DNA accurately using fluorescent methods (e.g., Qubit) rather than spectrophotometry alone, as the latter can overestimate concentration in the presence of contaminants.

- Inefficient Library Preparation: Errors during the library prep process, such as incomplete adapter ligation or poor PCR amplification efficiency, will result in a low-concentration final library. Always perform quality control checks on your final library to determine its size, distribution, and concentration before sequencing [2].

- Suboptimal Flow Cell Performance: For platforms like Illumina and Nanopore, the flow cell must have a sufficient number of active pores or clusters. Always check your flow cell quality before starting a run. For example, Oxford Nanopore recommends checking that a MinION/GridION flow cell has at least 800 active pores [3].

3. How can I improve the detection of low-frequency variants (e.g., below 0.1% allele frequency)?

Standard NGS protocols struggle with variant detection at very low frequencies due to background noise from DNA damage and polymerase errors. To achieve this sensitivity [4]:

- Implement Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): Also known as barcodes, UMIs are short random sequences used to tag individual DNA molecules before PCR amplification. After sequencing, bioinformatic analysis can group reads originating from the same original molecule (creating a "consensus read"), which effectively filters out errors introduced in later PCR cycles or during sequencing.

- Use High-Fidelity Polymerases: Employing high-fidelity DNA polymerases during the initial library amplification steps, especially during the UMI-barcoding step, can further suppress background error rates. One study found that using a high-fidelity polymerase in the barcoding PCR led to a 3.9-fold error reduction compared to a standard fidelity polymerase [4].

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Polymerase Fidelity in Barcoded NGS

This protocol is adapted from research investigating how polymerase fidelity impacts error rates in sequencing experiments that use molecular barcodes (UMIs) [4].

1. Objective: To quantify the effect of polymerase fidelity on background error rates in a barcoded NGS library preparation workflow.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- DNA Sample: High-quality genomic DNA.

- Barcoding Kit/Primers: Oligonucleotides containing unique molecular identifiers (UMIs).

- Polymerases: A set of DNA polymerases with a range of documented fidelities (e.g., from 1X to >100X relative to Taq polymerase).

- PCR Reagents: dNTPs, appropriate buffers.

- Agarose Gel Electrophoresis or TapeStation for size verification.

- Library Quantification Kit (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit [3]).

- Next-Generation Sequencer and associated library preparation reagents.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Initial Barcoding PCR. For each test polymerase, set up an identical PCR reaction containing the DNA template and UMI-containing primers. Use a low cycle number (e.g., 3 cycles) to minimally amplify the target while attaching the barcodes [4].

- Step 2: Adapter PCR. In a second PCR step, amplify the barcoded products from Step 1 using primers that add the full sequencing adapters (e.g., Illumina P5 and P7 sequences). This can be done with a standard, high-efficiency polymerase [4].

- Step 3: Library Completion. Purify the final PCR products, quantify the library, and load onto a sequencer.

- Step 4: Data Analysis. After sequencing, process the data to separate reads by their UMIs and generate consensus sequences for each original DNA molecule. Calculate and compare both the raw error rate (all reads) and the consensus error rate (after UMI-based correction) for the data generated with each polymerase [4].

4. Expected Outcome: The use of UMIs will dramatically reduce the error rate regardless of polymerase. However, using a high-fidelity polymerase in the initial barcoding step will provide a further, significant reduction in the consensus error rate, enabling more sensitive detection of true low-frequency variants [4].

Visual Guides and Workflows

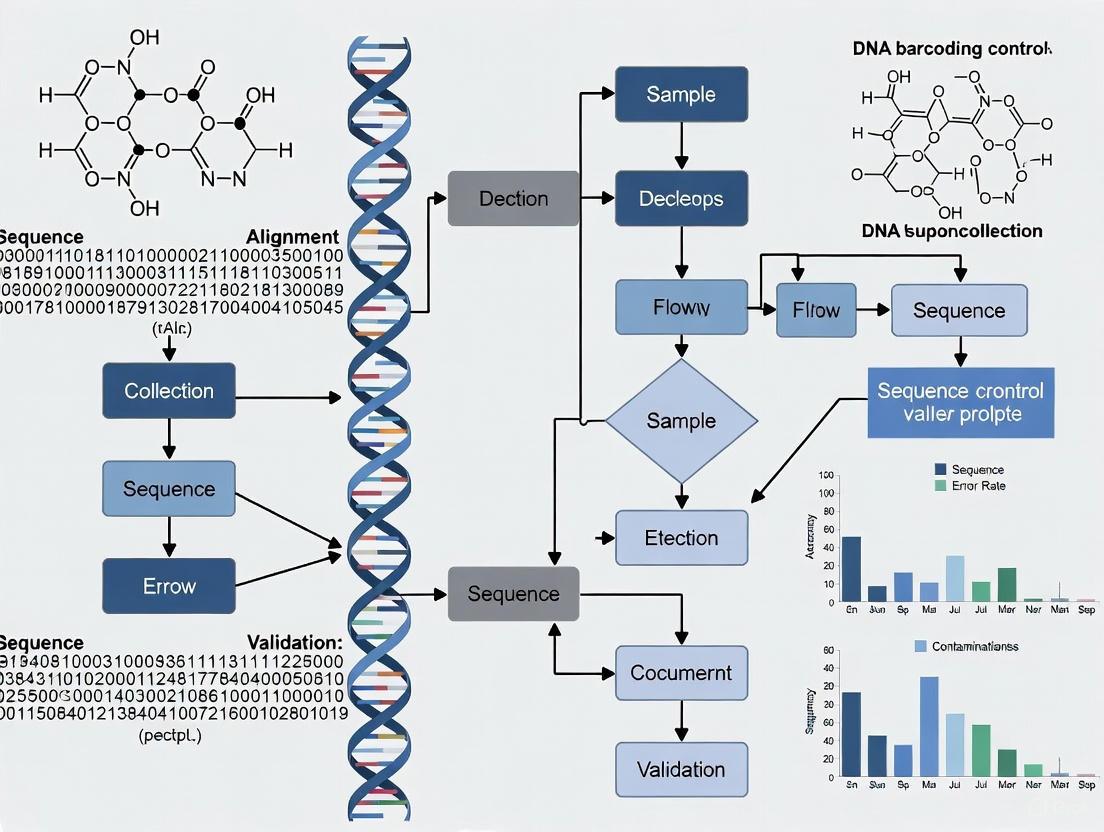

Sequencing Quality Control Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for NGS quality control, from sample preparation to data filtering, incorporating best practices from the literature [2] [4].

Error Correction with Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs)

This diagram outlines the core process of using UMIs to distinguish true biological variants from errors introduced during sequencing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials used in modern sequencing and barcoding workflows, as cited in the literature.

| Item | Function / Explanation | Example Context |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Polymerase | DNA polymerase with superior accuracy due to proofreading activity, reducing errors during PCR amplification. | Essential for barcoding NGS to enable detection of variants below 0.1% allele frequency [4]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences used to uniquely tag individual DNA molecules before amplification. | Allows bioinformatic error correction by generating consensus sequences from reads sharing a UMI [4]. |

| Rapid Barcoding Kit | A commercial kit that streamlines the process of attaching sample-specific barcodes for multiplexing. | Enables simultaneous sequencing of 1-96 samples with a library prep time of ~60 minutes [3]. |

| AMPure XP Beads | Magnetic beads used for the size-selective purification and clean-up of DNA fragments. | Used in library preparation protocols to remove short fragments, unincorporated nucleotides, and salts [3]. |

| Flow Cell | The consumable device where the sequencing reaction occurs, containing nanopores or patterned lawns of primers. | Must be checked for sufficient active pores (e.g., >800 for MinION) before a sequencing run [3]. |

| Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit | A fluorescent-based method for accurate quantification of double-stranded DNA concentration. | Used for quantifying input DNA and final library concentration, more specific than spectrophotometry [3] [2]. |

| Agilent TapeStation | An automated electrophoresis system that assesses DNA/RNA integrity, size distribution, and concentration. | Provides RNA Integrity Number (RIN) for sample QC and checks library fragment size post-preparation [2]. |

| Furan-2,5-dione;prop-2-enoic acid | Furan-2,5-dione;prop-2-enoic Acid|26677-99-6 | Furan-2,5-dione;prop-2-enoic acid is a reactive copolymer for materials science research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Ascorbyl Dipalmitate | Ascorbyl Dipalmitate, CAS:28474-90-0, MF:C38H68O8, MW:652.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers and scientists working on DNA barcoding for species identification. The content is framed within broader thesis research on DNA barcoding quality control and sequence validation.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common DNA Barcoding Workflow Issues

Low DNA Yield or Quality from Extraction

Problem: Inconsistent or low-quality DNA extraction from source material, leading to failed PCR amplification.

Solutions:

- Verify tissue preservation: For long-term storage of critical samples, tissues should be stored at -80°C. For short-term storage, preserve in fresh 95% ethanol [5].

- Check sample handling: Use flame-sterilized scalpels and forceps for each sample to prevent cross-contamination [5].

- Assess DNA quality: Use spectrophotometry to confirm a 260 nm/280 nm ratio of approximately 1.8. A lower ratio may indicate protein contamination [5]. Gel electrophoresis can assess DNA fragmentation, which is critical for processed products [6].

PCR Amplification Failure

Problem: The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) fails to amplify the target COI gene fragment, showing no or faint bands on a gel.

Solutions:

- Confirm DNA quantity: Ensure you have at least 5 ng/µL of DNA template for the PCR reaction [5].

- Use supportive molecular targets: If the standard ~650 bp COI fragment fails to amplify, especially from processed samples with fragmented DNA, use a "mini-barcoding" approach with shorter targets (e.g., a 139 bp COI fragment) [6].

- Switch polymerase for difficult samples: For bivalves or other challenging samples, substitute the standard Taq polymerase with a 5'-exonuclease deficient Taq polymerase (e.g., KlenTaq LA) to improve amplification [6].

Poor-Quality Sequencing Chromatograms

Problem: The resulting sequencing chromatogram (AB1 file) shows overlapping peaks or a high background signal, making base calls unreliable.

Solutions:

- Purify PCR products: Always perform a cleanup step on your PCR product before the sequencing reaction to remove excess primers and dNTPs [5].

- Confirm successful PCR: Perform a check (e.g., gel electrophoresis) to ensure a single, strong band of the correct size is present before proceeding to sequencing [5].

- Sequence both strands: Use both forward and reverse primers for cycle sequencing. Align the resulting sequences with a program like Clustal W to resolve ambiguities [6] [5].

Inconclusive Species Identification from Sequence Data

Problem: After sequencing, the data does not lead to a clear, unambiguous species match in reference databases.

Solutions:

- Employ a multi-target approach: If the primary target (e.g., COI) does not provide species-level resolution, amplify and sequence supportive genetic markers like cytochrome b (cytb) or 16S rRNA [6].

- Use multiple databases and parameters: Query your final sequence against both GenBank (using BLAST) and the Barcode of Life Data (BOLD) Systems (using the IDS engine). Use a validated identity score cut-off and Neighbour-Joining analysis for identification [6].

- Check for database gaps: Be aware that a lack of reference sequences for a particular species in public databases can prevent identification. This is a known limitation of the method [6].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the minimum quality thresholds for DNA to be suitable for barcoding? A: Success criteria from an FDA single laboratory validation (SLV) state you should obtain a DNA concentration of ≥5 ng/µL and a 260 nm/280 nm ratio of ~1.8, measured via spectrophotometry. A negative control should read ~0 ng/µL [5].

Q2: My sample is highly processed (e.g., cooked, canned). Can I still use DNA barcoding? A: Yes, but it requires protocol adjustments. For samples with medium-to-high DNA fragmentation, you must shift from a full-length barcode (FLB) approach to a mini-barcoding strategy, which targets much shorter DNA fragments (under 500 bp) that are more likely to survive processing [6].

Q3: What constitutes a "positive" species identification from a sequence? A: Identification relies on comparing your unknown sequence to a validated reference library. A positive identification is made when your sequence shows a high percentage match (exceeding a pre-defined identity score cut-off) to a sequence from a vouchered specimen in databases like BOLD or GenBank [6]. Statistical methods like Neighbour-Joining trees are often used to support the identification [6].

Q4: How can I design a self-checking program for my supply chain using DNA barcoding? A: DNA barcoding has been proven as an effective tool for verifying supplier compliance within a company's self-checking activities. You can apply a decision-tree protocol to analyze samples from incoming goods. This involves using a standard COI barcode first, followed by a multi-target approach if needed, to verify that the species identified matches the species declared on the label [6].

Workflow and Decision Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the critical control points (CCPs) and key decision points in the DNA barcoding workflow for species identification, based on established laboratory protocols [6] [5].

DNA Barcoding Workflow with Critical Control Points

Quantitative Performance Data

The following table summarizes key performance metrics from relevant DNA barcoding studies, providing benchmarks for your own quality control.

Table 1: Performance Metrics from DNA Barcoding Studies

| Study Focus | Total Samples Analyzed | Success Rate of Species ID | Primary Reason for Failure | Non-Compliance / Substitution Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seafood Identification (Fish & Molluscs) [6] | 182 | 96.2% (175/182) | Lack of reference sequences; low resolution of molecular targets [6] | 18.1% (33/182) [6] |

| Poultry Meat Products (Metabarcoding) [7] | 13 | 100% (for detecting declared species) | Not Applicable (Method was successful) | 61.5% (8/13 contained undeclared species) [7] |

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential materials and reagents used in the DNA barcoding workflow, as cited in the validated protocols.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for DNA Barcoding Experiments

| Item | Function in Protocol | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) | DNA extraction and purification from various tissue types [5]. | Used in the FDA SLV for tissue lysis and DNA extraction [5]. |

| Primers for COI (e.g., FishF1/FishR1) | Amplification of the standard ~650 bp cytochrome c oxidase subunit I barcode region from fish DNA [6] [5]. | Used as the first-choice target for fish and mollusk identification [6]. |

| Primers for Mini-Barcode | Amplification of a short (~139 bp) COI fragment from degraded or processed samples where the full-length barcode fails [6]. | Applied when DNA fragmentation is detected to cope with processed products [6]. |

| Primers for Alternative Targets (cytb, 16S rRNA) | Provide supportive data for species identification when the COI gene alone is not conclusive [6]. | Used in a multi-target approach to resolve ambiguous identifications [6]. |

| KlenTaq LA DNA Polymerase | A 5'-exonuclease deficient Taq polymerase used for improved amplification of difficult templates, such as bivalves [6]. | Substituted for standard Taq to amplify DNA from bivalves [6]. |

In DNA barcoding research, the reliability of your findings is directly dependent on the quality of your underlying sequence data. Poor-quality data can stem from a myriad of sources—biological, technical, and computational—leading to misidentification, failed experiments, and invalid conclusions. This technical support center is designed to help you, the researcher, diagnose and resolve these issues efficiently. The following guides and FAQs are framed within the critical context of DNA barcoding quality control and sequence validation, providing targeted solutions for the problems you might encounter in the lab or during data analysis [8].

Database Quality Assessment for DNA Barcoding

The reference database you select is a primary factor in the success and accuracy of DNA barcoding. The table below summarizes a comparative evaluation of two major databases, highlighting common quality issues you need to be aware of.

Table 1: Evaluation of COI Barcode Reference Databases for DNA Barcoding

| Evaluation Criteria | NCBI (Nucleotide Database) | BOLD (Barcode of Life Data System) |

|---|---|---|

| Barcode Coverage | Generally higher coverage for marine metazoan species in the WCPO [9] | Lower public barcode coverage, partly due to stricter submission requirements [9] |

| Sequence Quality | Lower overall sequence quality; more prone to errors and inconsistencies [9] | Higher sequence quality due to stricter quality control and curation [9] |

| Common Quality Issues | Over- or under-represented species; short sequences; ambiguous nucleotides; incomplete taxonomy; conflicting records [9] | Quality issues are less common but can include over-represented species and conflicting records [9] |

| Key Quality Feature | Lacks an integrated, automated quality evaluation system [9] | Features the Barcode Index Number (BIN) system to cluster sequences and flag problematic records [9] |

| Primary Weakness | Reliability is debated due to less robust curation of user-submitted data [9] | Lack of barcode records can reduce taxonomic resolution [9] |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

â–· PCR Failure Playbook

Symptom: No band or a very faint band on the gel.

- Likely Causes: Inhibitor carryover from the sample, low DNA template concentration, primer mismatch, or suboptimal PCR cycling conditions [10].

- First Fixes:

- Dilute the DNA template (1:5 to 1:10) to reduce the concentration of potential inhibitors.

- Add Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) to the reaction to mitigate inhibitors from complex sample matrices.

- Optimize the reaction by running a small annealing temperature gradient and modestly increasing the cycle number [10].

- Advanced Protocol: If initial fixes fail, consider a validated mini-barcode primer set, especially when working with degraded DNA, as it targets a shorter, more amplifiable region [10].

Symptom: Smears or non-specific bands on the gel.

- Likely Causes: Excessive template DNA input, high Mg²⺠concentration, low annealing stringency, or primer-dimer formation [10].

- First Fixes:

- Reduce the amount of DNA template used in the reaction.

- Optimize the Mg²⺠concentration and increase the annealing temperature.

- Use touchdown PCR to improve amplification specificity [10].

Symptom: Clean PCR product but a messy Sanger trace (e.g., double peaks).

- Likely Causes: Mixed template (contamination), leftover primers/dNTPs due to poor cleanup, heteroplasmy, or nuclear mitochondrial DNA segments (NUMTs) [10].

- First Fixes:

- Perform a thorough cleanup of the PCR product using enzymatic (e.g., EXO-SAP) or bead-based methods to remove residual primers and dNTPs before sequencing.

- Re-amplify from a diluted template to reduce co-amplification of non-target products.

- Sequence in both forward and reverse directions. If traces still disagree, suspect NUMTs and validate with a second, independent genetic locus [10].

â–· Sequencing Issues: Sanger and NGS

FAQ: How can I resolve low signal or mixed peaks in Sanger sequencing?

- Re-clean amplicons to thoroughly remove primers and dNTPs.

- If you observed smearing or multiple bands on the gel, gel-purify the correct band before sequencing.

- Use sequencing primers with an appropriate melting temperature (Tm) and avoid ends with extreme GC content.

- Always sequence both directions for confirmation, especially when heterozygous indels or ambiguous regions are suspected [10].

FAQ: What should I do when my NGS amplicon run yields low reads per sample?

- Likely Causes: Over-pooling of libraries, presence of adapter or primer dimers, low diversity of amplicons, or index misassignment [10].

- First Fixes:

- Re-quantify your libraries accurately using qPCR or fluorometry.

- Repeat bead cleanup to remove dimer artifacts and verify the result using fragment analysis.

- Spike in a higher percentage of PhiX control (e.g., 5-20%) to stabilize clustering with low-diversity amplicon libraries.

- Review your index design and pooling strategy to ensure even representation [10].

FAQ: How can I recognize and avoid NUMTs in COI barcoding?

- Red Flags: Frameshift mutations in the coding sequence, presence of stop codons in the translated amino acid sequence, unusual GC content, or disagreement between forward and reverse reads [10].

- Mitigation Strategies:

- Translate your nucleotide sequence to check for premature stop codons.

- Cross-validate species identification with a second, independent genetic locus.

- If NUMTs are suspected, report identification conservatively at the genus level and seek confirmation [10].

â–· Contamination Control

FAQ: My no-template controls (NTCs) are showing amplification. What should I do?

- Likely Cause: Aerosolized amplicon contamination (carryover) or shared equipment between pre- and post-PCR areas [10].

- Immediate Actions:

- Quarantine the entire batch of reagents and samples from the affected run.

- Hard-separate your pre-PCR and post-PCR laboratory spaces, ensuring dedicated equipment, reagents, and personnel flow for each. Never use post-PCR equipment in pre-PCR areas.

- Decontaminate workspaces and equipment with UV light and fresh bleach.

- Implement a chemical carryover control system using dUTP/UNG. This involves using dUTP instead of dTTP in PCR mixes. A subsequent treatment with Uracil-DNA Glycosylase (UNG) before thermal cycling will degrade any contaminating uracil-containing amplicons from previous runs, preventing their amplification [10].

Table 2: Essential Controls for Contamination Detection

| Control Type | Purpose | Action if Positive |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Blank | Detects contamination introduced during DNA extraction and purification. | Quarantine the batch and repeat the extraction from the last known clean step. |

| No-Template Control (NTC) | Detects contamination in the PCR reagents or from aerosolized amplicons. | Discard the affected reagent batch, decontaminate the workspace, and repeat the assay. |

| Positive Control | Confirms that the entire PCR and sequencing workflow is functioning correctly. | N/A |

Experimental Protocols for Quality Assurance

â–· Protocol: Evaluation of DNA Extraction Methods for Processed Foods

Background: This protocol is adapted from a study on DNA barcoding for food authenticity, which is directly relevant to obtaining high-quality data from challenging, processed samples where DNA is often degraded [11].

Sample Homogenization:

- For dried products (legumes, seeds, pasta), use a grinder to create a fine, homogeneous powder.

- For frozen, canned, or raw products, homogenize the material using a mortar and pestle under liquid nitrogen.

- Store all homogenized samples at -20°C or lower.

Inhibitor Removal (Pre-wash):

- To mitigate the effects of PCR-inhibiting compounds (e.g., polyphenols, polysaccharides), wash all samples twice with a Sorbitol Washing Buffer prior to DNA extraction [11].

DNA Extraction Comparison:

- Test multiple extraction methods in parallel to identify the most effective one for your specific sample matrix. The cited study compared:

- Two commercial silica column-based kits.

- A CTAB-based protocol with modifications.

- CTAB Protocol Modifications: After incubation with CTAB buffer and RNase treatment, add half a volume of 5 M NaCl, followed by three volumes of ice-cold absolute ethanol to precipitate the DNA. Incubate at -20°C for one hour, then centrifuge to pellet the DNA [11].

- Test multiple extraction methods in parallel to identify the most effective one for your specific sample matrix. The cited study compared:

DNA Quality Assessment:

- Quantify DNA using fluorometry for accuracy.

- Check DNA integrity and the presence of inhibitors by attempting to amplify a short, quality control locus (e.g., a mini-barcode) before proceeding with the full barcode assay.

â–· Protocol: In Silico Error Suppression for Deep NGS Data

Background: This methodology is crucial for detecting low-frequency genetic variants in deep next-generation sequencing data, as it computationally suppresses substitution errors that can mimic true biological signals [12].

Establish a Benchmark Dataset:

- Use a dilution series of a known sample (e.g., a cell line with known somatic mutations) to create a "truth set" for benchmarking. This allows you to characterize false-positive calls [12].

Measure Substitution Error Rates:

- For each genomic site i in a region known to be devoid of true genetic variation, calculate the error rate for each possible nucleotide substitution using the formula:

Error Rate_i (g>m) = (Number of reads with nucleotide m at position i) / (Total number of reads at position i)[12]. - This provides a baseline for the background error rate in your dataset.

- For each genomic site i in a region known to be devoid of true genetic variation, calculate the error rate for each possible nucleotide substitution using the formula:

Identify and Filter Low-Quality Reads:

- Trim 5 bp from both ends of each read to remove potentially low-quality bases and adapter contamination [12].

- Filter out reads with low overall mapping quality.

- Evaluate the per-cycle base quality score distribution. A gradual decline in quality with increasing cycle number is expected, but random dips or peaks may indicate technical issues [12] [13].

Error Suppression:

- Use the calculated error profiles and quality filters to set appropriate thresholds for variant calling. This computational suppression can reduce substitution error rates to the range of 10â»âµ to 10â»â´, significantly improving the sensitivity and specificity of low-frequency variant detection [12].

Visualization of Workflows

â–· DNA Barcoding and Data Quality Assessment Workflow

The diagram below outlines the core DNA barcoding process and key points where data quality must be assessed and validated.

This diagram categorizes the major sources of experimental error throughout a conventional NGS workflow, from sample to sequence.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for DNA Barcoding Quality Control

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Mitigates the effects of PCR inhibitors commonly found in complex biological samples (e.g., plant polyphenols). | Add to PCR reactions when amplification from difficult matrices is failing [10]. |

| Sorbitol Washing Buffer | Pre-wash buffer used to remove phenolic compounds and other contaminants from samples prior to DNA extraction. | Critical for improving DNA yield and purity from plant and food materials [11]. |

| Silica Column-Based Kits | For efficient purification of DNA, separating it from proteins, salts, and other impurities. | Commercial kits offer standardized, reliable protocols for obtaining high-quality DNA [11]. |

| CTAB Buffer | A detergent-based lysis buffer effective at breaking down plant cell walls and denaturing proteins. | A key component in classical plant DNA extraction protocols; useful for a wide range of tough samples [11]. |

| dUTP/UNG Carryover Control System | Prevents amplification of contaminating amplicons from previous PCR reactions. | dUTP is used in place of dTTP; UNG enzyme degrades uracil-containing DNA before PCR [10]. |

| PhiX Control Library | Used as a spike-in control for NGS runs to monitor sequencing quality and improve base calling for low-diversity libraries. | Particularly important for amplicon sequencing (e.g., DNA barcoding) where library diversity is low [10]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Enzyme with proofreading activity for accurate DNA amplification, reducing errors introduced during PCR. | Essential for generating high-quality sequences for barcode reference libraries [12]. |

| 1,1-Diethoxyhexane | 1,1-Diethoxyhexane|3658-93-3|Hexanal Diethyl Acetal | 1,1-Diethoxyhexane (Hexanal Diethyl Acetal) is a key acetalization reagent and flavor/fragrance intermediate for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or therapeutic use. |

| Tricyclo[6.2.1.02,7]undeca-4-ene | Tricyclo[6.2.1.02,7]undeca-4-ene, CAS:91465-71-3, MF:C11H16, MW:148.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

FASTQ Quality Score FAQs

What is a sequencing quality score?

A quality score (Q-score) is a numerical value that represents the probability that a base was called incorrectly by the sequencing instrument. It is defined by the equation: Q = -10logâ‚â‚€(e), where e is the estimated probability of an incorrect base call [1]. Higher Q-scores indicate higher accuracy.

What do the different Q-score values mean?

The table below shows how quality scores translate into base-calling accuracy:

| Quality Score | Probability of Incorrect Base Call | Base Call Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Q10 | 1 in 10 | 90% |

| Q20 | 1 in 100 | 99% |

| Q30 | 1 in 1000 | 99.9% |

| Q40 | 1 in 10,000 | 99.99% |

In practice, Q30 is considered a benchmark for high-quality data in next-generation sequencing, as virtually all reads will be perfect at this level [1].

How are quality scores encoded in a FASTQ file?

In FASTQ files, quality scores are encoded into a compact form using ASCII characters to represent numerical values. In the standard Phred+33 encoding, the quality score is represented as the character with an ASCII code equal to its value + 33 [14] [15].

The first few characters in this encoding scheme are [14] [15]:

| Symbol | ASCII Code | Q-Score |

|---|---|---|

! |

33 | 0 |

" |

34 | 1 |

# |

35 | 2 |

$ |

36 | 3 |

% |

37 | 4 |

Higher ASCII characters represent higher quality scores, with the full range extending from ! (lowest quality) to ~ (highest quality) [16].

Why does my FastQC report show "FAIL" for some modules when the data looks fine?

This is a common occurrence and doesn't necessarily indicate problematic data. Some FastQC warnings and failures can be safely ignored because [17]:

- FastQC applies assumptions designed for genomic libraries, so specialized libraries like RNAseq may naturally trigger failures

- Per base sequence content frequently fails for Illumina TruSeq RNAseq libraries due to hexamer priming bias

- Kmer content often fails in real-world datasets

- The key is to interpret results in the context of your experiment and sample type rather than treating all flags as critical errors

How can I resolve quality score encoding format issues?

If tools cannot process your FASTQ files, you may have a format/encoding mismatch. The solution is to ensure your data is in Sanger Phred+33 format (designated as fastqsanger in Galaxy) as this is what most tools expect [18].

You can [18]:

- Convert files using standardization tools

- Download reads from NCBI SRA already in

fastqsangerformat using specialized download tools - Check that the

+quality score lines are properly annotated

| Resource | Function | Relevance to DNA Barcoding QC |

|---|---|---|

| FastQC | Quality control tool for high throughput sequence data | Provides initial assessment of read quality, adapter contamination, and potential issues [17] |

| Trimmomatic/cutadapt | Read trimming and adapter removal | Improves overall data quality by removing poor quality bases and adapter sequences [17] |

| Dorado Basecaller | Converts raw electrical signals to nucleotide sequences | Oxford Nanopore's production basecaller; uses neural networks for accurate basecalling [19] |

| BOLD Systems | Barcode of Life Data repository | Curated reference database for validating DNA barcode sequences [20] |

| Remora/modkit | Modified base detection tools | Specialized tools for calling base modifications like 5mC, 5hmC [19] |

| GEANS Reference Library | Curated DNA barcode library for North Sea macrobenthos | Example of taxonomically reliable reference library for biodiversity monitoring [20] |

Quality Score Encoding Reference Table

This comprehensive table shows the complete Phred+33 encoding scheme used in FASTQ files:

| Symbol | ASCII Code | Q-Score | Symbol | ASCII Code | Q-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

! |

33 | 0 | 0 |

48 | 15 |

" |

34 | 1 | 1 |

49 | 16 |

# |

35 | 2 | 2 |

50 | 17 |

$ |

36 | 3 | 3 |

51 | 18 |

% |

37 | 4 | 4 |

52 | 19 |

& |

38 | 5 | 5 |

53 | 20 |

' |

39 | 6 | 6 |

54 | 21 |

( |

40 | 7 | 7 |

55 | 22 |

) |

41 | 8 | 8 |

56 | 23 |

* |

42 | 9 | 9 |

57 | 24 |

+ |

43 | 10 | : |

58 | 25 |

, |

44 | 11 | ; |

59 | 26 |

- |

45 | 12 | < |

60 | 27 |

. |

46 | 13 | = |

61 | 28 |

/ |

47 | 14 | > |

62 | 29 |

The encoding continues through uppercase letters, with A=65=Q32, up to I=73=Q40 [14] [15].

DNA Barcoding Context: Why Quality Scores Matter

In DNA barcoding research, quality scores are critical for reliable species identification. High-quality sequencing ensures:

- Accurate reference libraries: The GEANS project created a curated DNA reference library containing 4,005 COI barcode sequences from 715 North Sea macrobenthic species, where data quality was essential for reliable biodiversity monitoring [20]

- Valid species identification: Poor quality scores can lead to misidentification, particularly problematic for detecting non-indigenous species or cryptic species complexes [20]

- Reliable biodiversity assessment: Massive DNA barcoding approaches enable monitoring of soil macrofauna where traditional morphological identification is difficult, but only with high-quality sequence data [21]

Troubleshooting Workflow

FASTQ Quality Control Decision Pathway

This workflow guides researchers through systematic quality assessment, highlighting critical checkpoints for encoding verification and quality trimming that are essential for producing reliable DNA barcoding data.

Impact of Starting Material Quality on Downstream Analysis Success

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common consequences of poor-quality starting materials in DNA barcoding? Poor-quality starting materials lead to several common downstream problems:

- Misidentification: Contamination or sample mix-ups can result in sequences being assigned to the wrong species, compromising the entire dataset [22] [23]. One study on Hemiptera insects found that errors in public barcode databases are "not rare," often stemming from these initial issues [22].

- Failed Analyses: Poor DNA purity can inhibit the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), preventing the amplification of the target barcode region [24] [5]. The FDA's protocol emphasizes that success depends on obtaining DNA of sufficient quality and concentration [5].

- Unreliable Data: Low-quality sequencing reads, often reflected in low Q-scores, increase the probability of base-calling errors and false-positive variant calls, leading to inaccurate conclusions [1] [2].

2. How can I quickly assess the quality of my nucleic acid starting material before sequencing? A quick assessment can be made using the following methods and metrics:

Table 1: Quick Assessment Methods for Nucleic Acid Quality

| Method | Metric | Target Value for High Quality | Indication of Problem |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectrophotometry (e.g., NanoDrop) | A260/A280 Ratio | ~1.8 (DNA), ~2.0 (RNA) [2] | Significant deviation suggests protein or other contamination. |

| Spectrophotometry | A260/A230 Ratio | >2.0 | Indicates chemical contamination (e.g., salts, solvents) [2]. |

| Electrophoresis (e.g., TapeStation) | RNA Integrity Number (RIN) | 8-10 (RNA) [2] | A low RIN (e.g., <7) indicates RNA degradation. |

| Fluorometry (e.g., Qubit) | DNA/RNA Concentration | Varies | Provides a more accurate quantification of nucleic acids than spectrophotometry. |

3. My NGS data has a sudden drop in quality scores partway through the reads. What is the likely cause? A steady decrease in quality scores, particularly towards the 3' end of reads, is a normal artifact of sequencing-by-synthesis technologies [2]. However, an abrupt or abnormal drop in quality is often indicative of a technical error during the sequencing run, such as an issue with the sequencing instrument or its associated hardware [2]. This can also be caused by over-clustering on the flow cell, which leads to signal impurities [2].

4. A high percentage of my reads are unusable or cannot be mapped. What steps should I take? First, use quality control tools like FastQC to visualize your raw read data [2]. The likely culprit and solution involve read trimming and filtering:

- Problem: The presence of low-quality bases and adapter sequences.

- Solution: Use trimming tools (e.g., CutAdapt, Trimmomatic) to remove adapter sequences and trim low-quality bases (typically with a quality threshold below Q20) from the 3' end of reads [2]. After trimming, filter out reads that fall below a minimum length (e.g., <50 bp) to ensure only high-quality data proceeds to alignment [2].

5. My DNA barcode results conflict with the morphological identification of my specimen. What should I do? This discrepancy is a key application of DNA barcoding for quality control [23]. You should:

- Re-inspect the specimen: Re-examine the morphological characteristics, ideally with input from a trained taxonomist [22].

- Re-audit your workflow: Retrace all steps from specimen collection to DNA extraction and sequencing to check for potential sample mix-ups or contamination [22] [23].

- Re-sequence: Repeat the DNA extraction and barcoding process to rule out a one-off error.

- Check reference databases: Verify that the reference sequences in databases like BOLD and GenBank for your expected species are themselves based on correctly identified specimens, as errors in public repositories are a known issue [22] [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Failed PCR Amplification in DNA Barcoding

Problem: The target COI gene region fails to amplify during PCR.

Table 2: Troubleshooting PCR Amplification Failure

| Observed Issue | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| No PCR product on gel. | Degraded or low-quality DNA template. | Re-assess DNA quality (see Table 1). Extract new DNA, optimizing tissue lysis [5]. |

| No PCR product on gel. | PCR inhibitors present in DNA sample. | Dilute the DNA template. Use a cleanup kit to re-purify the DNA, or add bovine serum albumin (BSA) to the PCR reaction to counteract inhibitors. |

| Faint or smeared bands. | Suboptimal PCR conditions. | Optimize annealing temperature using a gradient PCR. Check primer specificity and concentration. |

| Amplification in negative control. | Contamination at some stage of the process. | Use dedicated pre- and post-PCR lab areas. Use UV irradiation and bleach to decontaminate surfaces. Prepare fresh reagents [22]. |

Troubleshooting Poor NGS Data Quality

Problem: Initial quality control of sequencing data (e.g., via FastQC) shows poor per-base quality scores.

NGS Quality Troubleshooting Flow

The workflow above, guided by the following actions, helps diagnose and resolve common issues:

- If quality drops at read ends: This is expected. Use trimming tools (e.g., Trimmomatic, CutAdapt) to remove low-quality bases from the ends, which will improve overall mapping rates [2].

- If there is an abrupt quality drop mid-read: This may indicate a temporary hardware or fluidics issue during the sequencing run. It is advisable to contact your sequencing facility for diagnostics and troubleshooting [2].

- If adapter content is high: Adapter sequences need to be removed from the reads prior to alignment. Use tools like CutAdapt or Porechop (for Oxford Nanopore data) to trim these artifacts, which is an essential step for data usability [2].

Key Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: DNA Extraction and Barcoding for Species Identification

This protocol is adapted from the FDA's single laboratory validated method for DNA barcoding of fish [5].

Goal: To consistently generate high-quality COI (Cytochrome c Oxidase subunit I) DNA barcodes from tissue samples for species identification.

Critical Materials and Reagents:

- DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) or equivalent for DNA extraction.

- PCR Reagents: Taq DNA polymerase, dNTPs, PCR buffer, MgCl2.

- COI Primers: Vertebrate-specific primers (e.g., FishF1, FishR1) [5].

- Agarose Gel materials for electrophoresis.

- Cycle Sequencing Kit (e.g., BigDye Terminator v1.1).

- Ethanol (96-100%) for precipitation and cleaning steps.

Step-by-Step Method:

- Tissue Sampling:

- Use a small cube (5-7 mm) of muscle tissue or a fin clip.

- Critical: Flame-sterilize forceps and scalpel between each sample to prevent cross-contamination [5].

- Preserve tissue in 95-100% ethanol or freeze at -20°C for short-term storage.

Tissue Lysis and DNA Extraction:

- Follow the protocol of your selected DNA extraction kit (e.g., DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit).

- Success Criteria: DNA concentration should be ≥5 ng/µL, with a A260/A280 ratio of ~1.8, measured on a spectrophotometer [5]. A negative control should yield ~0 ng/µL.

PCR Amplification of COI:

- Set up a 50 µL PCR reaction containing: 1x PCR buffer, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM each dNTP, 0.2 µM each primer, 1.25 U Taq polymerase, and 2-100 ng of DNA template.

- Thermocycler Conditions: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min; 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 50-54°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min; final extension at 72°C for 10 min [5].

PCR Product Check and Cleanup:

- Verify successful amplification by running 5 µL of the PCR product on a 1-2% agarose gel. A single, bright band at the expected size (~650 bp) should be visible.

- Clean up the remaining PCR product using a commercial cleanup kit to remove excess primers and dNTPs.

DNA Sequencing and Analysis:

- Perform cycle sequencing in both forward and reverse directions using the same primers as in the PCR step.

- Clean up the sequencing reactions to remove unincorporated dyes.

- Run the samples on a DNA sequencer and analyze the resulting chromatograms. Assemble forward and reverse reads and compare the consensus sequence to a validated reference database like BOLD.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for DNA Barcoding and NGS Workflows

| Item | Function/Application | Example Products/Brands |

|---|---|---|

| DNA/RNA Extraction Kits | Isolate high-purity nucleic acids from diverse tissue types. Critical for successful downstream applications. | DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) [5] |

| Spectrophotometer / Fluorometer | Quantify nucleic acid concentration and assess purity (A260/280 ratio). Fluorometers provide more accurate quantification. | NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher), Qubit (Thermo Fisher) [2] [5] |

| Electrophoresis System | Visually assess RNA integrity (RIN) or check size and quality of PCR products and sequencing libraries. | Agilent TapeStation, standard agarose gel systems [2] |

| NGS Library Prep Kits | Prepare DNA or RNA samples for next-generation sequencing by fragmenting, size-selecting, and adding platform-specific adapters. | Illumina DNA Prep, KAPA HyperPrep |

| Quality Control Software | Analyze raw sequencing data to evaluate quality scores, GC content, adapter contamination, and more. | FastQC [2] |

| Read Trimming & Filtering Tools | Programmatically remove low-quality bases, adapter sequences, and poor-quality reads from NGS data. | CutAdapt, Trimmomatic, Nanofilt [2] |

# Core Concepts: Why Size and Adapter Content Matter

In next-generation sequencing (NGS), the integrity of your library preparation is paramount. Two of the most critical quality control (QC) checkpoints are the size distribution of your DNA fragments and the adapter content of the final library. Proper assessment of these parameters is essential for a successful sequencing run, as failures here can lead to wasted reagents, poor data quality, and inaccurate downstream bioinformatics analysis [25] [26].

Assessing the average insert size and the tightness of the size distribution ensures optimal clustering on the flow cell and prevents issues like overlapping reads. Similarly, monitoring for excess adapter content or adapter dimers is crucial, as these can dominate the sequencing run, drastically reducing the yield of useful data [26]. Within the context of DNA barcoding research, where the goal is accurate species identification, these quality checks are non-negotiable. A compromised library can lead to failed barcode amplification or misassignment of sequences, undermining the validity of the entire study [9] [20].

# Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: My Bioanalyzer trace shows a sharp peak around 70-90 bp. What is this and how do I fix it?

- Problem: A sharp peak at ~70-90 bp is a classic signature of adapter dimers [26]. These are short fragments formed by the self-ligation of free adapters. They contain very little to no genomic insert and can outcompete your target library during cluster generation, leading to a very high proportion of useless sequences.

- Causes: This is typically caused by an suboptimal adapter-to-insert molar ratio during ligation, where adapters are in excess [26]. It can also result from inefficient purification after ligation, failing to remove unligated adapters.

- Solutions:

- Re-optimize Ligation: Titrate the adapter concentration to find the optimal ratio for your input DNA [25] [26].

- Improve Cleanup: Use a rigorous size selection method, such as magnetic beads with adjusted ratios (e.g., AMPure XP beads) or gel extraction, to specifically remove short fragments [25] [27]. Always follow cleanup protocols precisely to avoid sample loss or carryover of contaminants [26].

- Verify Input DNA: Ensure your starting DNA is not severely degraded, as low-molecular-weight DNA can also contribute to short fragments.

FAQ 2: My library yield is acceptable, but the fragment size distribution is very broad and uneven. What does this indicate?

- Problem: A wide or multi-peaked size distribution indicates inefficient or inconsistent fragmentation [25]. This can lead to uneven coverage, where some genomic regions are overrepresented and others are missed.

- Causes:

- Mechanical Shearing: Inconsistent sonication or acoustic shearing parameters (time, energy) [25].

- Enzymatic Fragmentation: Fluctuations in enzyme-to-DNA ratio or reaction time, or potential sequence bias in enzymatic methods [25].

- Over-amplification: Too many PCR cycles during library amplification can skew the representation of fragments, amplifying some sizes more than others [25] [26].

- Solutions:

- Calibrate Fragmentation: If using mechanical shearing, re-optimize the settings (e.g., duration, peak incident power) for your specific instrument and DNA quality. For enzymatic methods, standardize the reaction conditions and enzyme lots [25].

- Minimize PCR Cycles: Use the minimum number of PCR cycles necessary for your input material to avoid amplification bias [25].

- Implement Size Selection: Introduce a stringent size selection step (e.g., double-sided bead cleanup) to narrow the fragment size range before sequencing [25].

FAQ 3: My sequencing data shows high levels of adapter contamination in the FastQC report. How did this happen?

- Problem: High adapter content in your raw sequencing reads means that the sequencer was reading into the adapter sequence because the DNA fragment was shorter than the read length.

- Causes: This is often a result of insufficient removal of adapter dimers prior to sequencing or starting with overly short DNA fragments after fragmentation [2].

- Solutions:

- Pre-Sequencing QC: Always check your final library on a Bioanalyzer or TapeStation to confirm the absence of the adapter-dimer peak before loading the flow cell [2].

- Post-Processing: While not ideal, adapter sequences can be removed bioinformatically from the raw data using tools like CutAdapt or Trimmomatic [2]. However, this reduces the usable read length and is a corrective, not a preventive, measure.

- Preventive Action: The most robust solution is to address the issue during library prep by ensuring proper size selection and optimizing fragmentation to yield fragments longer than your intended read length.

Table 1: Common Library Prep Issues and Diagnostic Signals

| Problem | Primary Failure Signal | Common Root Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Adapter Dimer Contamination | Sharp ~70-90 bp peak on Bioanalyzer; high adapter content in FastQC [26] [2] | Excess adapters; inefficient post-ligation cleanup [26] |

| Skewed Size Distribution | Broad, multi-peaked, or shifted profile on Bioanalyzer [25] | Inefficient fragmentation (over/under-shearing); over-amplification [25] [26] |

| Low Library Yield | Low concentration via qPCR/fluorometry; faint electropherogram peaks [26] | Poor input DNA quality; suboptimal ligation; sample loss during cleanup [26] |

| Uneven Coverage / High Duplication | Bioinformatics analysis reveals biased read distribution | Over-amplification; low library complexity starting material [26] |

# Detailed Experimental Protocols for Assessment

Protocol 1: Assessing Library Size Distribution with a Fragment Analyzer

This protocol details the use of an Agilent Bioanalyzer or TapeStation system, the gold standard for assessing library size distribution.

- Preparation: Prime the instrument and prepare the gel-dye mix according to the manufacturer's instructions for the appropriate DNA sensitivity kit (e.g., High Sensitivity DNA kit).

- Sample Loading: Dilute 1 µL of your final library according to the kit's recommendations (typically to a concentration within 0.1-50 ng/µL). Load this volume into the specified well on the chip.

- Run: Start the analysis run. The instrument electrophoretically separates the DNA fragments by size.

- Data Interpretation:

- The software will generate an electropherogram (a trace plot) and a virtual gel image.

- The main peak represents your average library insert size plus the adapter length.

- A tight, single peak indicates a well-size-selected library. A broad peak or shoulder peaks suggest heterogeneous fragment sizes.

- Crucially, inspect the region around 70-90 bp for any sign of a peak, which indicates adapter dimer [26] [2].

Protocol 2: Bioinformatic Assessment of Adapter Content with FastQC

After sequencing, FastQC provides a direct assessment of adapter contamination in your data.

- Input: Provide your raw sequencing data in FASTQ format to the FastQC tool. This can be run from the command line or via a web portal like Galaxy [2].

- Analysis: Execute FastQC. It will generate a comprehensive HTML report with multiple modules.

- Interpretation: Navigate to the "Adapter Content" plot. This graph shows the cumulative percentage of reads in which an adapter sequence was detected at each position.

- A good result shows lines at or near 0%.

- Lines that rise, especially towards the end of the read, indicate significant adapter contamination, meaning your library contained short fragments or adapter dimers [2].

# Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Kits and Reagents for Library QC

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Application in DNA Barcoding |

|---|---|---|

| AMPure XP Beads | Magnetic beads for post-ligation cleanup and size selection. | Critical for removing adapter dimers and selecting the optimal barcode amplicon size, ensuring clean barcode libraries [25] [26]. |

| Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit | Microfluidic capillary electrophoresis for precise sizing and quantification of DNA libraries. | The primary tool for visually confirming library integrity and the absence of adapter dimers before costly sequencing [2]. |

| Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit | Fluorometric quantification of double-stranded DNA. | Provides accurate concentration measurement of amplifiable library molecules, superior to UV absorbance for precious barcoding samples [26] [2]. |

| Illumina Tagment DNA TDE1 Enzyme | Transposase for tagmentation (combined fragmentation and adapter tagging). | Used in streamlined protocols like Nextera for efficient library prep, though requires optimization to avoid bias [25] [28]. |

| CutAdapt / Trimmomatic | Bioinformatics software tools. | Used post-sequencing to trim adapter sequences from raw reads, a corrective action for contaminated barcode data [2]. |

# Workflow Diagram: Ensuring Library Integrity

The following diagram outlines the key steps and decision points for assessing and ensuring library preparation integrity, from sample to sequence.

Implementing Robust DNA Barcoding Protocols: From Wet Lab to Bioinformatics

Standardized DNA Extraction Protocols for Diverse Sample Types

The reliability of DNA barcoding and metabarcoding, powerful tools for species identification in research and drug development, is fundamentally dependent on the quality of input DNA. These techniques require reliable reference databases to ensure accurate assignment of DNA sequences to specific taxa, and the entire process begins with effective nucleic acid extraction [9] [20]. The integrity, purity, and yield of extracted DNA directly influence downstream applications, including PCR amplification and sequencing success. Standardized extraction protocols are therefore not merely preliminary steps but foundational components of rigorous DNA barcoding quality control and sequence validation research. This guide addresses the key technical challenges and provides standardized, reproducible methods for researchers working with diverse sample types.

Troubleshooting Guides for Common DNA Extraction Issues

Problem: Low DNA Yield

Low yield can halt projects and compromise data quality. Below are the common causes and their solutions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Low DNA Yield

| Potential Cause | Sample Type | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete cell lysis | All types | Increase incubation time with lysis buffer; increase speed/time of agitation; use a more aggressive lysing matrix or bead-beating [29] [30]. |

| Input amount too low | Cells, Blood | Use recommended input amounts. For cells, working with < 1 x 10^5 cells is not recommended. For low inputs, use a reduced lysis volume protocol [31]. |

| DNA did not attach to beads | All types (bead-based kits) | Ensure proper technique during binding. For precipitated DNA not attaching, twist the tube to create contact. If unsuccessful, spin down the precipitate and resuspend manually [31]. |

| Frozen blood sample thawed | Blood | Add Proteinase K and Lysis Buffer directly to frozen samples, allowing them to thaw during incubation to inhibit nuclease activity [29] [31]. |

| Protein precipitates clogged membrane | Blood, Tissue | Reduce Proteinase K lysis time to prevent insoluble hemoglobin complexes. Pellet protein precipitates by centrifuging at 12,000 × g for 10+ minutes before applying lysate to spin filter [29]. |

Problem: DNA Degradation

Degraded DNA is unsuitable for long-range PCR or high-molecular-weight applications.

Table 2: Troubleshooting DNA Degradation

| Potential Cause | Sample Type | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Sample age or improper storage | Blood, Tissue | Use fresh whole blood within one week. For tissues, process immediately or snap-freeze in liquid nitrogen. Store at -80°C for long-term preservation [29] [31]. |

| Nuclease activity post-homogenization | Tissue | Place homogenized samples in lysis buffer into a thermal mixer immediately after homogenization to inactivate nucleases. Process samples individually to minimize delays [31]. |

| Improper handling of UHMW DNA | All types (HMW prep) | Always use wide-bore pipette tips. Avoid vortexing. Limit extended heating periods (e.g., do not exceed 15-30 minutes at 56°C) [31]. |

| Sample thawed before processing | Blood | Never thaw frozen blood before adding RBC Lysis Buffer. Add cold lysis buffer directly to the frozen sample [31]. |

Problem: Contamination and Impurities

| Potential Cause | Sample Type | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High hemoglobin content | Blood | Indicated by a dark red color after lysis. Extend lysis incubation time by 3–5 minutes to improve purity [29]. |

| Cross-contamination | All types | Use designated equipment and reagents. Thoroughly clean workspace. Use positive and negative controls to detect contamination early [29]. |

| Co-precipitation of polysaccharides/polyphenols | Plant Tissues | For plant tissues, use the CTAB method and add 2-5% PVP (polyvinylpyrrolidone) to the lysis buffer to adsorb polyphenols [30]. |

| Inhibitors in processed samples | Food, TCM | Pre-wash samples with Sorbitol Washing Buffer before extraction to remove PCR inhibitors like phenolics [11]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most critical factor for successful DNA extraction from plant-based materials used in drug development? The most critical factor is effectively counteracting secondary metabolites like polysaccharides and polyphenols, which can co-precipitate with DNA and inhibit downstream enzymes. The gold-standard method is the CTAB (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) protocol, often optimized with polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) to bind polyphenols and β-mercaptoethanol to prevent oxidation [30]. This is especially important for authenticating Traditional Chinese Medicine species where PCR inhibition can lead to misidentification [32].

Q2: How does the level of food processing impact DNA extraction efficiency for barcoding, and how can this be mitigated? Processing (e.g., thermal treatment, canning, drying) fragments and degrades DNA. To mitigate this:

- Use a Robust Lysis Protocol: The CTAB method with a pre-wash step is often more effective than simple commercial kits for breaking down processed matrices [11].

- Target Shorter Barcodes: If standard barcodes (~650 bp) fail to amplify, switch to "mini-barcoding" which targets shorter genetic regions (<300 bp) from degraded DNA [32].

- Increase Starting Material: Use 100-200 mg of processed sample to increase the chance of obtaining sufficient intact DNA molecules [11].

Q3: For high-throughput drug discovery projects, should I use manual or automated DNA extraction? Automation is highly recommended. Automated platforms using magnetic bead technology provide more consistency between samples, eliminate human error, save manual working time, and are ideal for processing 96-well plates or more. While upfront costs are higher, the time- and cost-savings are significant for large-scale projects like genomic sequencing or population studies [30].

Q4: Why is my extracted DNA difficult to resuspend, and how can I fix it? This is typically caused by overdrying the DNA pellet, especially after ethanol precipitation. To fix this:

- Air-dry pellets instead of using a vacuum centrifuge.

- Rehydrate by heating the pellet in a buffer like TE (pH 7-8) at 55-65°C for about 5 minutes. Do not exceed 1 hour.

- Gently pipette up and down with a wide-bore tip to homogenize without shearing the DNA [29] [31].

Standardized Experimental Protocols for Key Sample Types

Protocol: CTAB-Based DNA Extraction from Plant Leaves

This is a foundational method for challenging plant tissues, critical for building reliable DNA barcode libraries for medicinal plants [30] [32].

- Grinding: Grind 100 mg of leaf tissue to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen using a mortar and pestle.

- Lysis: Transfer the powder to a tube with 1 mL of preheated CTAB buffer (2% CTAB, 1.4 M NaCl, 100 mM Tris-Cl, 20 mM EDTA, 0.2% β-mercaptoethanol). Incubate at 65°C for 30-60 minutes with occasional gentle mixing.

- Deproteinization: Add an equal volume of chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1). Mix thoroughly by inversion to form an emulsion. Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 15 minutes.

- DNA Precipitation: Transfer the upper aqueous phase to a new tube. Add 1/10 volume of 5 M NaCl and an equal volume of isopropanol. Mix by inversion until DNA is visible as a stringy precipitate.

- Wash: Pellet the DNA by centrifugation. Wash the pellet with 1 mL of 70% ethanol. Centrifuge again and carefully discard the ethanol.

- Resuspension: Air-dry the pellet briefly and resuspend in 100 µL of TE buffer or nuclease-free water.

Protocol: Silica Column-Based Extraction from Whole Blood

A common method for obtaining high-quality DNA from human subjects in pharmacogenomic studies.

- Erythrocyte Lysis: Lyse red blood cells by mixing 1-10 mL of whole blood (with EDTA anticoagulant) with 3-4 volumes of RBC Lysis Buffer. Incubate on ice for 10-15 minutes, then centrifuge to pellet leukocytes. For frozen blood, add cold lysis buffer directly to the frozen sample. [31]

- Lysis of Leukocytes: Resuspend the leukocyte pellet in a cell lysis buffer containing Proteinase K. Incubate at 56°C until the solution is clear.

- Binding: Add ethanol to the lysate and mix. Load the mixture onto a silica membrane column.

- Washing: Centrifuge and pass wash buffers containing ethanol through the column to remove salts and impurities.

- Elution: Elute the pure DNA in a low-salt buffer like TE or nuclease-free water [30].

Workflow Visualization: From Sample to Validated Barcode

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of standardized DNA extraction and its pivotal role in ensuring the quality of DNA barcoding data for research and drug development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for DNA Extraction and Their Functions

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| CTAB (Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) | A cationic detergent that effectively lyses plant cell walls and membranes and complexes with polysaccharides to separate them from DNA. | Essential for starchy or polysaccharide-rich plant tissues. The high-salt (1.4 M NaCl) condition prevents co-precipitation of polysaccharides with DNA [30]. |

| Proteinase K | A broad-spectrum serine protease that degrades nucleases and other proteins, protecting DNA and facilitating lysis. | Critical for digesting tough tissues and inactivating DNases. Incubation is typically done at 56°C for 30 minutes to several hours [29] [30]. |

| Silica Columns / Magnetic Beads | Binds DNA under high-salt, low-pH conditions, allowing impurities to be washed away. DNA is eluted in a low-salt buffer. | The basis for most commercial kits. Ideal for high-throughput, automated workflows and provides consistent purity [30]. |

| PVP (Polyvinylpyrrolidone) | Binds to polyphenols and tannins in plant samples, preventing them from oxidizing and inhibiting downstream PCR. | Add 2-5% to lysis buffers when working with polyphenol-rich plants like tea, grapes, or conifers [30]. |

| β-mercaptoethanol | A reducing agent that denatures proteins and helps to inhibit polyphenol oxidation by scavenging oxygen. | Added to CTAB lysis buffer for plant samples. Note: Toxic and must be used in a fume hood. |

| EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) | A chelating agent that binds magnesium ions, which are essential cofactors for DNase enzymes, thus inhibiting DNA degradation. | Used as an anticoagulant in blood collection (preferable over heparin, which inhibits PCR) and as a component of most lysis and storage buffers [29] [30]. |

| (2s,3s)-1,4-Dibromobutane-2,3-diol | (2s,3s)-1,4-Dibromobutane-2,3-diol, CAS:299-70-7, MF:C4H8Br2O2, MW:247.91 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| N,N-dimethylaniline;sulfuric acid | N,N-dimethylaniline;sulfuric acid, CAS:58888-49-6, MF:C8H13NO4S, MW:219.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Primer Selection and PCR Optimization for Target Amplification

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Addressing Common PCR Challenges in DNA Barcoding

1. What are the first steps when my PCR reaction produces no amplification or a low yield? First, verify the presence, integrity, and purity of your DNA template using gel electrophoresis or spectrophotometry [33]. If the template is degraded or contaminated, re-purify it. Then, optimize your PCR conditions by adjusting the annealing temperature (typically 3–5°C below the primer Tm) and ensuring critical component concentrations are correct [33] [34]. Increase the amount of DNA polymerase or dNTPs if they are insufficient, and consider using polymerases with high sensitivity for challenging samples [33].

2. How can I reduce non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation? Non-specific products often result from low reaction stringency. Increase the annealing temperature stepwise in 1–2°C increments and review your Mg2+ concentration, as excess Mg2+ can promote nonspecific binding [33]. To prevent primer-dimer formation, which is exacerbated by high primer concentrations and self-complementary primers, carefully redesign primers to avoid complementary sequences, especially at the 3' ends [33] [35]. Using hot-start DNA polymerases is highly effective, as they remain inactive at room temperature, preventing spurious amplification during reaction setup [33] [34].

3. Why is primer optimization critical for multi-assay panels in quantitative applications? When running multiple RT-qPCR assays under identical thermal cycling conditions, optimizing primer concentration is essential for achieving high sensitivity and specificity. A study optimizing 60 RT-qPCR assays found that performance was highly dependent on primer concentration, with 65% of assays performing best with asymmetric primer concentrations [36]. This optimization significantly reduced Cq values and minimized primer-dimer formation, ensuring accurate and reproducible gene expression data [36].

Troubleshooting Common PCR Problems

Table: Common PCR Issues, Causes, and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No/Low Amplification [33] [34] | Poor template quality/quantity, suboptimal cycling conditions, insufficient reagents. | Repurify/concentrate DNA template. Optimize annealing temperature and Mg2+ concentration. Increase polymerase/dNTPs or cycle number. |

| Non-Specific Bands [33] [34] | Low annealing temperature, excess Mg2+, primer concentration too high, problematic primer design. | Increase annealing temperature. Optimize Mg2+ and primer concentrations. Use hot-start polymerase. Redesign primers for better specificity. |

| Primer-Dimer Formation [33] [35] | High primer concentration; primers with 3' complementarity. | Lower primer concentration (0.1–1 µM). Increase annealing temperature. Redesign primers to avoid self-complementarity. |

| Smeared Bands on Gel [34] | Degraded DNA template, contaminants, non-specific products from low stringency. | Repurify template DNA. Optimize PCR stringency (Mg2+, Ta). Separate pre- and post-PCR workspaces to prevent contamination. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standardized DNA Barcoding for Crustaceans Using 5' and 3' COI Fragments

Background: This protocol is optimized for identifying commercial decapod crustaceans, where the standard 5' COI barcode fragment may not efficiently amplify all shrimp species. Amplifying a non-overlapping 3' COI fragment can provide successful identification [37].

Primers:

- 5' COI Fragment: Use primers from established studies (e.g., Folmer et al., 1994) [38] [37].

- 3' COI Fragment: Requires a separate primer set targeting a 475 bp region near the 3' end of the COI gene [37].

Methodology:

- DNA Extraction: Isolate genomic DNA from tissue samples using a standard purification kit, ensuring final DNA is free of PCR inhibitors like phenol or EDTA [33].

- PCR Optimization: The key to success is optimizing MgCl2 and dNTP concentrations, which may need to be 2–4 fold higher than standard protocols [37].

- PCR Amplification: Perform two separate PCR reactions for the 5' and 3' COI fragments using optimized conditions.

- Capillary Sequencing: Purify PCR products and sequence them.

- Sequence Analysis: Trim sequences against appropriate reference sequences for each fragment and use BLAST or BOLD systems for species identification [37].

Protocol 2: Primer Optimization Matrix for Multiplex RT-qPCR Assays

Background: For profiling multiple gene transcripts simultaneously under uniform thermal cycling conditions, optimizing primer concentrations is crucial for assay sensitivity and specificity [36].

Methodology:

- Primer Design: Design gene-specific primers according to standard guidelines (e.g., 18-30 bp, Tm ~60-64°C) [35] [39].

- Matrix Setup: Prepare a primer optimization matrix by testing a range of forward and reverse primer concentrations (e.g., 100 nM, 200 nM, and 300 nM) in all possible combinations, keeping all other reaction components constant [36].

- qPCR Run and Analysis: Run the qPCR reactions with the different primer combinations. The optimal combination is identified by the lowest Cq value, lowest standard deviation between replicates, and the absence of primer-dimer peaks in melt curves or gel analysis [36].

- Probe Concentration (if applicable): For probe-based assays, further optimize by testing probe concentrations (e.g., 100 nM vs. 200 nM) using the optimal primer combination [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for DNA Barcoding and PCR Optimization

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Reduces non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation by remaining inactive until a high-temperature activation step [33] [34]. |

| PCR Additives (BSA, Betaine) | Helps amplify difficult targets (e.g., GC-rich sequences). BSA can bind inhibitors common in complex samples, while betaine destabilizes secondary structures [33] [34]. |

| dNTP Mix | The building blocks for DNA synthesis. Use balanced, high-purity dNTPs to prevent incorporation errors and ensure efficient amplification [33]. |

| Magnesium Salt (MgClâ‚‚/MgSOâ‚„) | A critical cofactor for DNA polymerase activity. Its concentration must be optimized, as it directly affects reaction stringency, yield, and specificity [33] [39]. |

| Universal Primers (e.g., LCO1490/HCO2198) | Well-established primers for amplifying the standard 5' region of the COI gene across a wide range of metazoan taxa for DNA barcoding [38] [20]. |

| (S)-2-Bromo-3-methylbutanoic acid | (S)-2-Bromo-3-methylbutanoic acid, CAS:26782-75-2, MF:C5H9BrO2, MW:181.03 g/mol |

| Benzene-1,2,4,5-tetracarboxamide | Benzene-1,2,4,5-tetracarboxamide Polyamine|RUO |

Workflow Diagrams

Primer Selection and Validation Workflow

Systematic PCR Troubleshooting Pathway

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My MultiQC report is missing results for some of my samples, even though the log files (e.g., from FastQC) are present. What could be the cause?

This is a common issue, often resulting from clashing sample names [40]. When multiple input files resolve to the same sample name, MultiQC will only display the last one processed. To investigate:

- Run MultiQC with the

-v(verbose) flag or check themultiqc_data/multiqc.logfile for warnings about duplicated sample names [40]. - Inspect the

multiqc_data/multiqc_sources.txtfile to see which source file was ultimately used for each sample [40]. - Use the

-d(debug) and-s(print files to stdout) flags for a more detailed report on file parsing [40].

Q2: MultiQC runs successfully but finds no logs for a tool I know ran and produced output. How can I fix this?

This can occur for several reasons [40]:

- Tool Support: First, verify the tool is officially supported by MultiQC.

- File Size Limits: By default, MultiQC skips files larger than 50MB. You may see a debug message like

Ignoring file as too large: filename.txt. Increase this limit via the config optionlog_filesize_limitin your MultiQC configuration file [40]. - Search Line Limits: MultiQC only scans the first 1000 lines of each file for content-matching patterns. If your relevant log entry is beyond this, increase the limit using the

filesearch_lines_limitconfig option [40]. - Concatenated Logs: If logs from multiple tools are in one file, a log might be "consumed" by one module and ignored by another. This can be resolved by configuring the

filesearch_file_sharedsetting [40].

Q3: Can I include both raw and trimmed FastQC results in the same MultiQC report?

Yes. A common challenge is that the raw and trimmed FastQC outputs often have identical filenames, causing one to overwrite the other. The solution in a pipeline context (like Nextflow) is to stage the files in separate subdirectories (e.g., file('fastqc_raw/*') and file('fastqc_trimmed/*')). This prevents filename clashes and allows MultiQC to process both sets of results independently [41] [42].

Q4: How can I add custom information, like my lab's logo and project details, to the MultiQC report?

MultiQC supports extensive customization through a configuration file [43]:

- Branding: Use

custom_logo,custom_logo_url, andcustom_logo_titleto add your logo [43]. - Report Info: Set a custom

title,subtitle, andintro_textfor the report [43]. - Project Metadata: Add key-value pairs (e.g., "Contact E-mail", "Sequencing Platform") under

report_header_infoto display project-level details at the top of the report [43].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Incomplete Sample Results in Report

Problem MultiQC generates a report, but it does not include all samples that were processed.

Diagnosis and Solutions This is typically caused by sample name collisions or issues with file parsing.

Solution A: Diagnose Name Clashes

- Run

multiqc . -vand examine the log for warnings about duplicate sample names [40]. - Use the

--forceflag to see all overwrite warnings interactively.

- Run

Solution B: Optimize for Large Files

- If log files are very large, MultiQC might skip them. The following configuration can be added to a MultiQC config file to adjust these limits [40]:

Issue: Pipeline-Specific MultiQC Configuration

Problem Integrating MultiQC into a bioinformatics pipeline (e.g., Nextflow, Snakemake) requires careful handling of file channels and naming.

Diagnosis and Solutions

Solution A: Nextflow Integration

- Collect Inputs: Use