DNA Barcoding vs. PCR: A Comparative Guide to Molecular Diagnostics for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive comparison for researchers and drug development professionals between DNA barcoding and other PCR-based diagnostic methods.

DNA Barcoding vs. PCR: A Comparative Guide to Molecular Diagnostics for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison for researchers and drug development professionals between DNA barcoding and other PCR-based diagnostic methods. It explores the foundational principles of both techniques, delves into their specific methodologies and diverse applications in biomedical research, and addresses common challenges and optimization strategies. A critical validation and comparative analysis equips scientists with the knowledge to select the most appropriate tool for their work, from species identification and pathogen detection to ensuring the safety and authenticity of herbal medicines and food products.

Core Principles: From Species Identification to Pathogen Detection

In the molecular toolkit of researchers and drug development professionals, few techniques are as fundamental yet distinct as DNA barcoding and the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). While the terms are often mentioned together, they represent different concepts: one is a specific application for species identification, and the other is a versatile method for amplifying DNA. This guide objectively compares their performance, supported by experimental data, to clarify their roles in modern molecular diagnostics and research.

Core Concepts: Purpose and Principle

At its core, PCR is a foundational technique for amplifying specific DNA sequences. Think of it as a molecular photocopier; it can make millions to billions of copies of a particular DNA segment from a complex sample, enabling detailed analysis [1]. This process involves repeated cycles of heating and cooling to denature DNA strands, allow primers to anneal, and extend new DNA chains using a thermostable enzyme [1]. The real power of PCR lies in its versatility—it's not a single test but a platform that enables countless applications, from genotyping and gene expression analysis to cloning and sequencing [2].

In contrast, DNA barcoding is a diagnostic application that uses a short, standardized genetic sequence to identify an organism at the species level. Imagine it as a universal product code for life [3]. This method relies on comparing the sequence of a specific gene region from an unknown sample against a reference library of known sequences for classification [4]. The most common barcode for animals is a segment of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) gene, while plants often use a combination of chloroplast genes like matK and rbcL [3] [5].

The relationship between the two is hierarchical: DNA barcoding almost always uses PCR as a critical step to amplify the target barcode region before it can be sequenced and identified [4] [3]. The table below summarizes their defining characteristics.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of PCR and DNA Barcoding

| Feature | PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) | DNA Barcoding |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Enzymatic amplification of a targeted DNA region [1]. | Species identification via comparison of a standardized DNA sequence [3]. |

| Primary Purpose | To generate numerous copies of a DNA sequence for detection, analysis, or other uses [2]. | To assign an unknown biological sample to a known species [4]. |

| Key Output | Amplified DNA fragments (amplicons) [1]. | A species-level identification based on sequence match [3]. |

| Relationship | A foundational enabling technology. | An application that typically relies on PCR for amplification. |

Experimental Comparison: A Case Study in Species Identification

A direct comparison of their performance can be illustrated by a 2025 study on canned tuna species identification, a field challenged by mislabelling and high DNA degradation due to heat processing [6] [7]. This research compared three methods for identifying tuna species: DNA barcoding (using a Control Region mini-barcode), real-time PCR (a quantitative PCR method), and multiplex PCR (a type of PCR that detects multiple targets at once) [7].

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Canned Tuna Identification (n=24 products)

| Method | Identification Rate | Relative Cost & Time | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real-Time PCR | 100% [7] | ~$6 per sample; 3-6 hours [7] | High sensitivity (detected 0.1-1% of target species); ideal for rapid screening [7]. | Requires species-specific probes; limited to pre-defined targets [7]. |

| DNA Barcoding | 33% [7] | Higher cost and time [7] | Can detect a range of expected and unexpected species via sequencing [6]. | Less effective with highly degraded DNA; slower due to sequencing step [7]. |

| Multiplex PCR | 29% [7] | ~$6 per sample; 3-6 hours [7] | Can detect multiple target species simultaneously in a single assay [7]. | Lower sensitivity and identification rate compared to real-time PCR in this application [7]. |

The study concluded that while real-time PCR was superior for rapid, sensitive screening of known species, a combination with DNA barcoding was recommended for its ability to provide sequencing-based confirmation and detect unexpected species [6] [7]. This demonstrates a key trade-off: targeted PCR methods excel in speed and sensitivity for known targets, whereas DNA barcoding offers broader discovery power at the cost of efficiency.

Workflow and Methodology

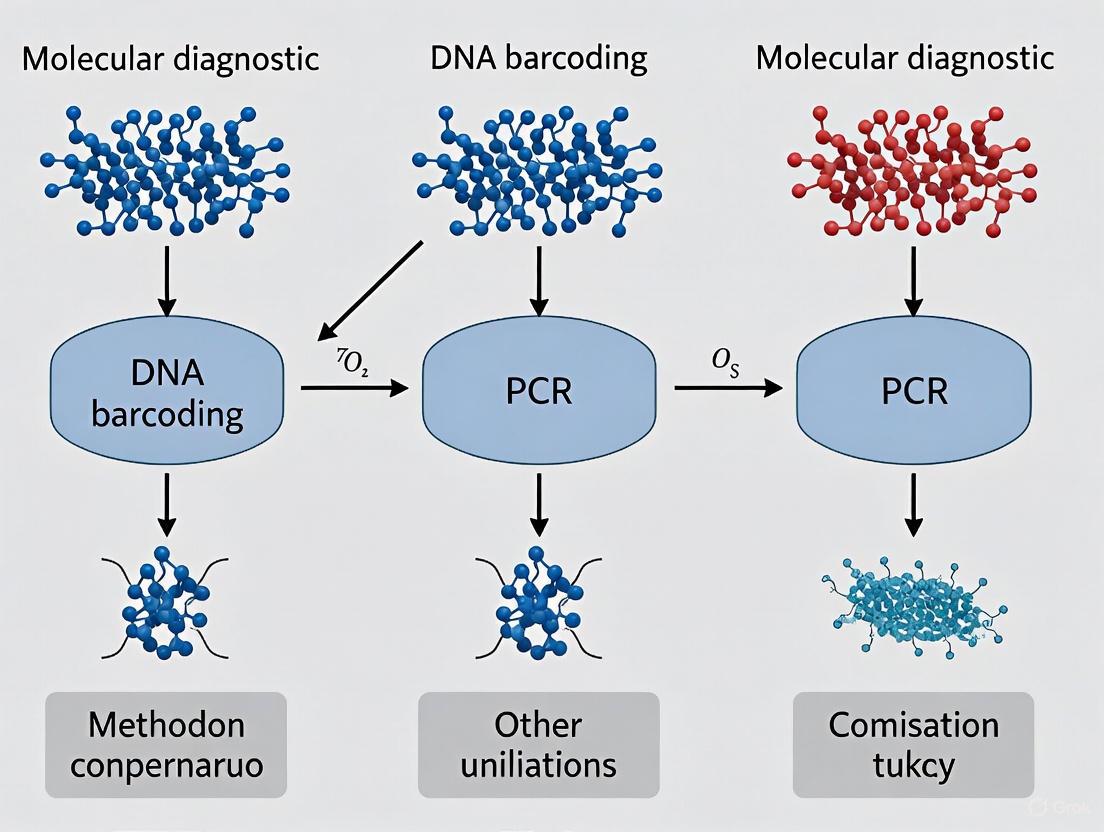

The following diagram illustrates the key steps and decision points in the processes of a DNA barcoding workflow and a targeted PCR assay, highlighting where they converge and diverge.

A 2024 study on mosquito surveillance provides another compelling performance comparison. Researchers evaluated a multiplex PCR assay against DNA barcoding for identifying eggs of different Aedes mosquito species collected from ovitraps. The results were striking: the multiplex PCR successfully identified the species in 1,990 out of 2,271 samples and detected mixtures of species in 47 samples. In contrast, DNA barcoding could only identify 1,722 samples and could not reliably detect species mixtures in a single sample [8]. This underscores a major limitation of standard DNA barcoding: its inability to deconvolute mixtures without cloning, which is far more time-consuming and expensive than a multiplex PCR setup.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and their functions in these molecular workflows.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for PCR and DNA Barcoding

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Thermostable DNA Polymerase | Enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands during PCR [1]. | High-fidelity enzymes are critical for minimizing errors in barcoding and cloning [2]. |

| Primers (Oligonucleotides) | Short DNA sequences that are complementary to the target and define the region to be amplified [1]. | Barcoding uses universal primers; targeted PCR uses species-specific primers [3] [8]. |

| dNTPs | Deoxynucleotide triphosphates (A, T, C, G); the building blocks for new DNA [1]. | Required in all PCR-based amplification reactions. |

| Buffer Solutions | Provide optimal chemical environment (pH, salts) for polymerase activity [1]. | May include additives to enhance amplification of difficult templates (e.g., GC-rich). |

| DNA Extraction Kit | To isolate and purify DNA from tissue, cells, or environmental samples [7]. | Critical first step; choice of kit depends on sample type (e.g., canned tuna vs. mosquito eggs) [7] [8]. |

| Agarose Gel Electrophoresis | To separate and visualize PCR products by size [4]. | Common initial check for successful amplification in both barcoding and endpoint PCR. |

| Sanger Sequencing Reagents | To determine the nucleotide sequence of a DNA fragment [4]. | Required for the final identification step in the DNA barcoding workflow. |

The distinction between DNA barcoding and PCR is clear: PCR is a broadly applicable amplification engine, while DNA barcoding is a specific identification system that uses this engine. The choice between using a targeted PCR assay (like real-time or multiplex PCR) and a broader DNA barcoding approach depends entirely on the research question.

For rapid, high-throughput screening of a few known target species, targeted PCR methods are more sensitive, faster, and more cost-effective. When the goal is to discover unexpected species, identify unknown specimens, or detect a wide range of organisms in a complex sample, DNA barcoding (or its community-level counterpart, metabarcoding) is the superior, albeit slower, tool [5].

The future of molecular diagnostics lies in leveraging the strengths of both. As seen in the tuna study, a combined approach of rapid real-time PCR screening with confirmatory DNA barcoding creates a powerful framework for ensuring product authenticity, protecting consumer health, and enforcing accurate labeling [6] [7]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this hierarchy and the performance trade-offs is essential for designing robust and accurate molecular assays.

In the evolving landscape of molecular diagnostics, DNA barcoding has emerged as a powerful taxonomic tool for species identification. First formally proposed in 2003, the technique utilizes short, standardized gene sequences to discriminate between species, functioning much like a universal product code for life forms [9] [10]. The fundamental premise rests on the "barcoding gap"—the principle that genetic variation within species is significantly less than the variation between species [9]. While traditional PCR-based methods target specific known organisms, DNA barcoding enables both the identification of known species and the discovery of new ones by comparing sequences to reference libraries. This guide objectively examines the core architectural principles of DNA barcoding—its specificity, inheritance, and manipulability—and provides a direct performance comparison with alternative molecular diagnostic methods such as multiplex PCR.

The Three Building Blocks: A Conceptual Foundation

The operational efficacy of DNA barcoding is underpinned by three fundamental properties.

Specificity: The technique's power derives from its use of short DNA sequences (generally 400-800 base pairs) from standardized genomic regions that exhibit high inter-specific (between species) and low intra-specific (within species) variation [9] [3]. This allows for precise species-level identification. Specificity also enables high-throughput sequencing (HTS) applications for the simultaneous identification of DNA from different origins in complex, multi-taxa samples [11].

Inheritance: DNA barcodes are constructed from genetic material that is passed from one generation to the next. This hereditary nature allows researchers to track lineages through time, overcoming previous challenges in observing clonal population dynamics in fields such as evolution, development, and cancer research [11]. This property is crucial for both prospective lineage tracing (using engineered barcodes) and retrospective studies (using naturally occurring variations) [12].

Manipulability and Adaptability: DNA barcodes are highly manipulable and can be adapted to a wide range of molecular applications. Their unique sequences can be identified via PCR, sequencing, or direct hybridization without enzymatic amplification [11]. This adaptability has led to the development of advanced protocols, such as the use of fluorescent molecular barcodes for highly multiplexed gene expression profiling, demonstrating the technology's versatility beyond simple species identification [11].

DNA Barcoding vs. Multiplex PCR: An Experimental Comparison

A direct comparison of DNA barcoding and multiplex PCR was performed in a 2024 study focused on identifying container-breeding Aedes mosquito species from ovitrap samples, a common task in ecological monitoring and public health [8] [13].

Experimental Protocols

- Sample Collection: Mosquito eggs were collected weekly using ovitraps (black containers filled with water with a wooden spatula for oviposition) set across Austria during 2021 and 2022 [8].

- DNA Extraction: Eggs from each spatula were homogenized, and DNA was extracted using commercial kits (innuPREP DNA Mini Kit or BioExtract SuperBall Kit) [13].

- DNA Barcoding Protocol: The standard mitochondrial Cytochrome c Oxidase subunit I (mtCOI) gene was amplified by PCR. The resulting amplicons were then sequenced using Sanger sequencing, and the sequences were compared to reference databases like NCBI GenBank for species identification [8] [13].

- Multiplex PCR Protocol: An adapted multiplex PCR protocol was used, which incorporated a universal forward primer and species-specific reverse primers for four target species: Ae. albopictus, Ae. japonicus, Ae. koreicus, and Ae. geniculatus. Species identification was determined by the presence and size of the amplified bands following gel electrophoresis [8].

Performance Results and Comparative Analysis

The study analyzed 2,271 samples, and the results are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of DNA Barcoding and Multiplex PCR for Mosquito Egg Identification

| Performance Metric | DNA Barcoding | Multiplex PCR |

|---|---|---|

| Total Samples Successfully Identified | 1,722 out of 2,271 | 1,990 out of 2,271 |

| Samples with Multiple Species Detected | Not reliably achievable with Sanger sequencing | 47 samples |

| Primary Strength | Discovers cryptic species; identifies a broad range of taxa without prior knowledge of targets. | High-throughput, cost-effective identification of pre-defined target species. |

| Key Limitation | Cannot detect multiple species in a single sample using Sanger sequencing. | Limited to a pre-determined set of species; cannot discover novel or unexpected species. |

| Best Application Context | Biodiversity discovery, diet analysis, and linking different life stages of organisms [10]. | Targeted monitoring and surveillance of specific, known species of interest. |

The experimental data demonstrates that for the specific application of targeted surveillance, the multiplex PCR protocol was more successful, identifying over 250 more samples than DNA barcoding [8]. Crucially, multiplex PCR detected mixtures of different species in 47 samples, a feat not possible with standard DNA barcoding that relies on Sanger sequencing [8] [13]. This highlights a key limitation of DNA barcoding for analyzing bulk samples.

The following workflow diagrams illustrate the core technical processes and their relationship to the three building blocks.

DNA Barcoding Core Workflow

Core Principles Drive Diverse Applications

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

The implementation of DNA barcoding and its alternatives relies on a suite of specific research reagents and tools. The following table details key components essential for conducting these experiments.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Barcoding and Comparative Methods

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Universal PCR Primers | Amplify standardized barcode regions from diverse specimens. | Folmer primers for the COI gene in metazoans [9] [3]. |

| Taxon-Specific PCR Primers | Target conserved flanking sites for a particular group of organisms. | ITS primers for fungi; rbcL & matK primers for plants [9] [3]. |

| DNA Polymerases | Enzymatic amplification of target DNA barcode regions. | Critical for both standard barcoding PCR and multiplex PCR protocols [8] [3]. |

| Reference Databases | Curated libraries of barcode sequences for taxonomic identification. | BOLD (Barcode of Life Data) Systems, NCBI GenBank [9] [10]. |

| High-Throughput Sequencers | Parallel sequencing of millions of DNA fragments. | Enables metabarcoding of complex environmental samples [14] [15]. |

| Species-Specific Probes | Short oligonucleotides for hybridization-based detection. | Used in multiplex PCR for band differentiation and NanoString's nCounter system for direct gene counting [11] [8]. |

Within the broader thesis of molecular diagnostics, DNA barcoding establishes its unique niche not as a replacement for other PCR-based methods, but as a complementary tool with distinct strengths. Its core building blocks—specificity, inheritance, and manipulability—enable applications that are difficult for targeted assays to replicate, including biodiversity discovery, lineage tracing, and dietary analysis. However, when the task shifts from discovery to high-throughput, targeted monitoring of known species—as in the case of invasive mosquito surveillance—alternative methods like multiplex PCR can offer superior detection rates and the critical ability to identify mixed samples. The choice of technology, therefore, must be guided by the specific research question, whether it requires casting a wide net for the unknown or efficiently screening for a defined set of targets.

Since its inception in the 1980s, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has fundamentally transformed molecular biology, establishing itself as the undisputed gold standard for nucleic acid detection [16] [17]. This revolutionary technique enables researchers to amplify specific DNA sequences millions to billions of times, creating sufficient material for detection and analysis. The core principle of PCR involves repeated thermal cycling—denaturation, annealing, and extension—to exponentially amplify target DNA sequences using thermally stable DNA polymerase enzymes [18]. Over decades, PCR technology has evolved significantly, giving rise to advanced real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) and digital PCR (dPCR) methods that offer enhanced quantification capabilities and precision [16] [19]. In the specialized field of DNA barcoding, where species identification relies on amplifying and sequencing short, standardized genetic markers, PCR remains the foundational technology that enables accurate taxonomic discrimination across diverse biological samples [20] [21].

Principles of PCR Amplification

The fundamental power of PCR lies in its elegant simplicity, mimicking natural DNA replication but achieving exponential amplification through repeated temperature cycles. The process relies on several key components: a DNA template containing the target sequence, two specific oligonucleotide primers flanking the target, thermostable DNA polymerase (typically Taq polymerase), deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs), and a buffer solution containing magnesium ions [18].

The Thermal Cycling Process

PCR amplification occurs through three repeating temperature steps that typically cycle 25-40 times:

- Denaturation: The reaction mixture is heated to 94-98°C, causing the double-stranded DNA template to separate into single strands by breaking the hydrogen bonds between complementary bases.

- Annealing: The temperature is lowered to 50-65°C, allowing the primers to bind specifically to their complementary sequences on the single-stranded DNA templates.

- Extension: The temperature is raised to 72°C, the optimal temperature for DNA polymerase activity, which synthesizes new DNA strands by adding dNTPs to the 3' end of the primers, creating complementary copies of the target sequence.

This cyclic process results in exponential amplification, theoretically producing 2^n copies of the target sequence after n cycles [18]. The specificity of PCR is determined by the primer design, while the efficiency depends on multiple factors including primer annealing kinetics, enzyme processivity, and buffer conditions.

Evolution to Real-Time Methods

The transition from conventional PCR to real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) marked a significant advancement in molecular diagnostics. While conventional PCR provides end-point detection, qPCR enables monitoring of the amplification process in real-time through fluorescent detection systems [19]. This quantification capability transformed PCR from a qualitative tool to a precise quantitative method, allowing researchers to determine initial template concentrations with remarkable accuracy.

Two main chemistries facilitate real-time detection:

- DNA-binding dyes: Non-specific fluorescent dyes that intercalate with double-stranded DNA, with fluorescence increasing proportionally with amplicon accumulation.

- Fluorescent probes: Sequence-specific probes (such as TaqMan probes) that provide higher specificity through hybridization to internal target sequences.

The quantitative capability of qPCR is based on the cycle threshold (Ct) value, which represents the number of cycles required for the fluorescent signal to cross a threshold above background levels. Lower Ct values indicate higher initial template concentrations, enabling precise quantification through comparison with standard curves [19].

Comparative Performance of PCR Technologies

The evolution of PCR technologies has created distinct platforms with unique advantages and limitations. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of conventional PCR, quantitative PCR (qPCR), and digital PCR (dPCR):

Table 1: Comparison of Major PCR Technologies

| Parameter | Conventional PCR | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Digital PCR (dPCR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amplification Principle | End-point exponential amplification | Real-time fluorescent monitoring during exponential phase | Partitioning and end-point detection |

| Quantification Capability | Qualitative or semi-quantitative (relative) | Relative quantification (requires standard curve) | Absolute quantification (no standard curve) |

| Sensitivity | Moderate | High | Very High (can detect rare variants) |

| Variant Detection Sensitivity | ~10% variant allele frequency | ~1% variant allele frequency [16] | ~0.1% variant allele frequency [16] |

| Detection Method | Gel electrophoresis or other post-amplification detection | Fluorescent probes or DNA-binding dyes | Fluorescent probes with Poisson statistical analysis |

| Throughput | Low to moderate | High | Moderate to high |

| Key Applications | Cloning, sequencing, preliminary detection | Gene expression, pathogen quantification, mutation detection | Rare variant detection, liquid biopsy, copy number variation |

Digital PCR represents the most significant recent advancement in PCR technology, providing absolute quantification without requiring standard curves [16] [22]. By partitioning a single PCR reaction into thousands of individual reactions (either in droplets or nanowells), dPCR enables precise counting of target molecules through Poisson statistics [16]. This partitioning provides superior sensitivity for detecting rare mutations and precise quantification, particularly valuable for liquid biopsy applications where minute amounts of circulating tumor DNA must be detected against a background of wild-type DNA [16].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of qPCR vs. dPCR for Respiratory Virus Detection

| Virus | Viral Load Category | qPCR Performance | dPCR Performance | Superior Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza A | High (Ct ≤25) | Moderate precision and consistency | Superior accuracy and precision [22] | dPCR [22] |

| Influenza B | High (Ct ≤25) | Moderate precision and consistency | Superior accuracy and precision [22] | dPCR [22] |

| RSV | Medium (Ct 25.1-30) | Variable quantification | Greater consistency and precision [22] | dPCR [22] |

| SARS-CoV-2 | High (Ct ≤25) | Good detection | Superior accuracy [22] | dPCR [22] |

| All Viruses | Low (Ct >30) | Challenging detection | Improved sensitivity for low viral loads [22] | dPCR [22] |

PCR in DNA Barcoding and Molecular Diagnostics

DNA barcoding utilizes PCR to amplify standardized genetic markers for species identification, with applications ranging from food authentication to biodiversity assessment [20] [21]. The cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (CO1) gene region serves as the primary barcode for animal identification, while other genetic markers (rbcL, matK, ITS2) are used for plants [20].

Experimental Workflow for DNA Barcoding

The standard DNA barcoding protocol involves:

- Sample Collection and DNA Extraction: Tissue samples are obtained and DNA is extracted using commercial kits (e.g., DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit) [21] [23]

- PCR Amplification: Target barcode regions are amplified using specific primers. For mixed samples, multiplex PCR may be employed to simultaneously target multiple species [20]

- Sequencing: Amplified products are sequenced using Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing platforms

- Sequence Analysis: Resulting sequences are compared against reference databases (e.g., BOLD, GenBank) for species identification

Advanced Applications: PCR Cloning for Mixed Samples

Standard DNA barcoding faces limitations when analyzing mixed-species samples, as Sanger sequencing produces overlapping chromatograms that are unreadable [21] [23]. PCR cloning overcomes this challenge by inserting amplicons into bacterial vectors, transforming E. coli, and sequencing individual clones to separate mixed templates [21] [23].

Table 3: Performance of PCR Cloning for Mixed-Species Fish Product Identification

| Method | Single Species Identification Rate | Mixed Species Identification Rate | Species Detection in Mixed Samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Full Barcoding (655 bp) | 100% (15/15 samples) [23] | 80% (identification of at least one species) [23] | Limited to dominant species only |

| Standard Mini-Barcoding (226 bp) | 100% (15/15 samples) [23] | 51% (identification of at least one species) [23] | Limited to dominant species only |

| Full Barcoding + PCR Cloning | Not applicable | Increased detection of multiple species | Nile tilapia: 100% (12/12 samples); Pacific cod: 50% (6/12 samples) [23] |

| Mini-Barcoding + PCR Cloning | Not applicable | Increased detection of multiple species | Nile tilapia: 100% (12/12 samples); Pacific cod: 75% (9/12 samples) [23] |

Alternative Nucleic Acid Amplification Techniques

While PCR remains the most widely used nucleic acid amplification technique, several alternative methods have been developed with distinct advantages for specific applications:

Table 4: Comparison of PCR with Alternative Amplification Techniques

| Technique | Amplification Principle | Temperature Requirements | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR | Thermal cycling with DNA polymerase | Variable temperatures (denaturation, annealing, extension) | Gold standard, highly versatile, well-established | Requires thermal cycler, susceptible to inhibitors |

| LAMP | Auto-cycling strand displacement DNA synthesis | Isothermal (60-65°C) | Rapid, simple detection (turbidity/colorimetry), resistant to inhibitors [18] | Complex primer design, limited multiplexing capability [18] |

| NASBA | RNA amplification via reverse transcriptase and RNA polymerase | Isothermal (41°C) | High sensitivity for RNA detection, suitable for viral pathogens [18] | Expensive commercial kits, challenges in master mix preparation [18] |

| TMA | RNA transcription amplification | Isothermal | Highly sensitive, rapid results (<2 hours), used for HIV/HCV detection [18] | Requires specific equipment, more complex protocol [18] |

| SDA | Strand displacement with nicking enzyme | Isothermal | Can amplify both ssDNA and dsDNA, high sensitivity [18] | Generates shorter amplicons, complex enzyme system [18] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful PCR experimentation requires careful selection of reagents and optimization of reaction conditions. The following table outlines essential components for modern PCR-based research:

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for PCR-Based Experiments

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Thermostable DNA Polymerase | Enzymatic DNA synthesis during amplification | Choice depends on fidelity (proofreading activity), processivity, and resistance to inhibitors |

| Primers | Sequence-specific initiation of amplification | Design affects specificity, annealing temperature, and amplification efficiency; HPLC purification recommended |

| dNTPs | Building blocks for new DNA strands | Quality affects error rate; concentration balance crucial (equal molarity of A, T, G, C) |

| Buffer Systems | Optimal reaction environment for enzyme activity | Typically contain Tris-HCl, KCl, Mg²⁺; Mg²⁺ concentration requires optimization |

| Probe Systems | Sequence-specific detection in qPCR/dPCR | Hydrolysis (TaqMan) or hybridization (Molecular Beacon) probes; require careful design and validation |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Nucleic acid purification from various sample types | Choice depends on sample matrix (blood, tissue, FFPE); affects yield, purity, and inhibitor removal |

PCR maintains its position as the gold standard for nucleic acid amplification due to its robust methodology, continuous innovation, and adaptability to diverse research needs. The evolution from conventional PCR to real-time qPCR and digital dPCR has expanded its applications from basic DNA amplification to precise quantification and rare variant detection. In DNA barcoding, PCR remains indispensable for species identification, while advanced approaches like PCR cloning extend its utility to complex mixed samples. Despite the emergence of isothermal alternatives, PCR's versatility, well-established protocols, and ongoing technological advancements ensure its continued dominance in molecular diagnostics and research. As PCR technologies continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly address current limitations and open new frontiers in genetic analysis, maintaining PCR's critical role in scientific discovery and applied diagnostics.

Infectious diseases and product authentication represent two frontiers where accurate identification is critical for public health and safety. In 2025, infectious diseases such as tuberculosis (claiming an estimated 1.25 million lives annually), H5N1 bird flu (with 81 confirmed human cases in 2024), and measles (with resurgences linked to declining vaccination rates) continue to pose substantial global threats [24]. Simultaneously, the globalization of food supply chains has created vulnerabilities in product authentication, with studies revealing that up to 75% of plant genetic diversity has been lost due to agricultural intensification, complicating the verification of food products [25].

These parallel challenges share a common need for precise, reliable, and scalable diagnostic solutions. Traditional methods often fall short: morphological identification of species can be slow and requires specialized expertise, while conventional molecular techniques may lack the specificity, sensitivity, or multiplexing capability needed for comprehensive analysis [13] [15]. This diagnostic gap has accelerated the development of advanced molecular techniques, with DNA barcoding emerging as a powerful tool for species identification across diverse applications from clinical diagnostics to food authenticity verification [26].

Technology Comparison: DNA Barcoding Versus Alternative Molecular Diagnostics

Molecular diagnostics encompass a range of technologies for identifying biological materials. The table below compares DNA barcoding with other established and emerging molecular methods.

Table 1: Comparison of Molecular Diagnostic Technologies

| Technology | Principle | Key Applications | Multiplexing Capability | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Barcoding | Species identification using short, standardized DNA fragments [26] | Species identification, biodiversity assessment, food authentication [15] [25] | Limited with Sanger sequencing; enhanced with metabarcoding [15] | Requires reference databases; primer-template mismatches possible [26] |

| Singleplex PCR | Amplification of a single target sequence per reaction | Pathogen detection, genetic testing [27] | None | Low throughput; more sample/reagent consumption for multiple targets |

| Multiplex PCR | Simultaneous amplification of multiple targets in a single reaction [13] | Respiratory panels, STI testing, mosquito surveillance [13] [28] | High (dozens of targets) | Primer interference risk; optimization complexity |

| qPCR (Real-Time PCR) | Quantitative PCR with fluorescent monitoring of amplification | Viral load monitoring, gene expression analysis [27] | Moderate (typically 4-6 targets) | Requires specific instrumentation; quantification challenges at low targets |

| Digital PCR (dPCR) | Absolute quantification by partitioning samples into nanoreactors [27] | Low-abundance target detection, liquid biopsies, antimicrobial resistance [27] | Moderate | High cost; specialized equipment needed |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Massively parallel sequencing of multiple DNA fragments | Genomic surveillance, variant detection, metagenomics [29] | Very high (thousands to millions of fragments) | Higher cost; complex data analysis; longer turnaround times |

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Aedes Mosquito Identification (n=2271 samples)

| Method | Successfully Identified Samples | Mixed-Species Detection | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiplex PCR [13] | 1990 (87.6%) | 47 samples | Higher success rate; detects species mixtures; faster turnaround |

| DNA Barcoding (mtCOI gene) [13] | 1722 (75.8%) | Not detected | Broad taxonomic applicability; creates reference data |

The performance advantage of multiplex PCR for specific surveillance applications is demonstrated in Table 2. In a direct comparison of 2,271 mosquito egg samples, multiplex PCR successfully identified 87.6% of samples compared to 75.8% with DNA barcoding, and critically detected 47 mixed-species samples that conventional barcoding missed [13]. This illustrates how method selection must be guided by specific application requirements rather than assuming universal superiority of any single technology.

DNA Barcoding: Principles and Experimental Workflows

Fundamental Principles and Barcode Selection

DNA barcoding operates on the principle that short, standardized DNA sequences can reliably distinguish between species due to genetic variation. The fundamental requirement is identifying a DNA region with sufficient interspecies variability for discrimination while maintaining adequate intraspecies conservation for consistent identification [15]. For animal species, the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) gene serves as the primary barcode region, while plants often employ a combination of the chloroplastic ribulose-bisphosphate carboxylase (rbcL) gene and the nuclear internal transcribed spacer (ITS) due to slower mitochondrial evolution in plants [26] [25].

The experimental workflow follows a systematic process from sample collection to sequence analysis, with careful attention to minimizing contamination and ensuring reproducibility. The diagram below illustrates the core DNA barcoding workflow.

Diagram 1: DNA Barcoding Workflow

Key Research Reagents and Materials

Successful DNA barcoding requires specific reagents and materials tailored to sample type and analysis goals. The table below details essential components of the DNA barcoding toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for DNA Barcoding Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits (e.g., silica column-based kits, CTAB protocol) [25] | Isolation of high-quality DNA from diverse sample matrices | CTAB protocol preferred for plant tissues with high polyphenols; pre-washing with Sorbitol Washing Buffer reduces inhibitors [25] |

| PCR Primers (e.g., COI, ITS, rbcL-specific) [15] | Target amplification of standardized barcode regions | Degenerate primers broaden taxonomic coverage; sample-specific "tags" enable multiplexing [15] |

| DNA Polymerase (e.g., hot-start, high-fidelity) | PCR amplification of barcode regions | Hot-start enzymes reduce non-specific amplification; proofreading polymerases enhance sequence accuracy |

| Agarose Gels & Electrophoresis Systems | Verification of successful PCR amplification and amplicon size confirmation | Quality control step before sequencing; identifies failed amplifications or contamination |

| Sanger Sequencing Reagents | Generation of sequence data from amplified barcodes | Standard for single-species identification; cannot resolve mixtures [13] |

| Reference Databases (e.g., BOLD, GenBank) [26] | Species identification by sequence comparison | Database completeness critical for accuracy; curated references reduce misidentification |

Comparative Experimental Data: Case Studies Across Applications

Infectious Disease Monitoring: Aedes Surveillance

The critical importance of method selection is exemplified in mosquito surveillance programs, where accurate identification of invasive species directly impacts public health responses. A 2024 study directly compared multiplex PCR against DNA barcoding for identifying four Aedes species in Austria, using 2,271 ovitrap samples collected in 2021-2022 [13].

Table 4: Experimental Protocol for Mosquito Surveillance Study

| Aspect | Methodological Details |

|---|---|

| Sample Collection | Ovitraps with black plastic containers and wooden spatulas; weekly collection [13] |

| DNA Extraction | Homogenization with ceramic beads/TissueLyser; innuPREP DNA Mini Kit or BioExtract SuperBall Kit [13] |

| Multiplex PCR | Adapted from Bang et al. protocol; targets: Ae. albopictus, Ae. japonicus, Ae. koreicus, Ae. geniculatus [13] |

| DNA Barcoding | Mitochondrial COI gene amplification and Sanger sequencing [13] |

| Analysis | Band size comparison (multiplex PCR) vs. sequence database matching (barcoding) |

The multiplex PCR protocol demonstrated clear operational advantages, detecting 47 mixed-species samples that Sanger sequencing-based barcoding missed [13]. This methodological superiority directly impacts public health preparedness, particularly for monitoring invasive species like Ae. albopictus, a known vector for dengue, Zika, and chikungunya viruses [13].

Food Authentication: Biodiversity in Plant-Based Products

Food authentication represents another critical application where DNA barcoding provides unique capabilities. A 2025 study evaluated ten commercial plant-based products to verify biodiversity claims and detect mislabeling using ITS and rbcL markers [25].

Table 5: Experimental Protocol for Food Authentication Study

| Aspect | Methodological Details |

|---|---|

| Sample Processing | Homogenization of entire package contents; grinding (dried products) or mortar/pestle with liquid nitrogen (frozen/canned) [25] |

| DNA Extraction | Comparison of 3 methods: 2 commercial silica column kits and CTAB protocol; pre-washing with Sorbitol Washing Buffer [25] |

| Barcode Amplification | PCR with ITS and rbcL primers; verification on agarose gels [25] |

| Sequencing & Analysis | Sanger sequencing; BLAST against reference databases; heat map analysis of label vs. detected contents [25] |

The study successfully identified numerous plant genera and species across six tested products, with strong correlation between ITS and rbcL markers supporting their combined use for reliable species-level identification [25]. While most products showed high concordance with label claims, researchers detected undeclared species and absent labeled taxa in some cases, highlighting potential mislabeling or cross-contamination issues in commercial food supply chains [25].

The diagram below illustrates the specialized workflow for food authentication studies.

Diagram 2: Food Authentication DNA Barcoding Workflow

The comparative analysis of DNA barcoding and alternative molecular diagnostics reveals a nuanced technological landscape where method selection must be driven by specific application requirements. DNA barcoding provides unmatched versatility for species identification across biological kingdoms, making it particularly valuable for biodiversity assessment, food authentication, and pathogen discovery [26] [15] [25]. However, for targeted surveillance of known pathogens or specific adulterants, multiplex PCR offers superior sensitivity, speed, and mixed-target detection capabilities [13].

The future diagnostic landscape will likely see increased integration of these complementary technologies rather than exclusive selection. Emerging approaches include DNA barcoding coupled with nanozymes and biochips for enhanced sensitivity [26], CRISPR-based detection systems for field applications [27], and metabarcoding with next-generation sequencing for comprehensive microbiome analysis [15]. Furthermore, the CDC's 2025 priorities emphasize Advanced Molecular Detection (AMD) programs that combine genomic technologies with bioinformatics to address emerging infectious threats [29].

For researchers and public health professionals addressing diagnostic challenges in infectious disease and product authentication, the strategic approach involves matching methodological capabilities to specific use cases: DNA barcoding for discovery and biodiversity applications, multiplex PCR for targeted surveillance of known threats, and integrated approaches for the most complex diagnostic challenges. As global threats continue to evolve, this methodological precision will be essential for protecting public health and ensuring product authenticity in increasingly complex global supply chains.

Techniques in Action: From Lab Bench to Real-World Solutions

DNA barcoding has emerged as a revolutionary technique in molecular diagnostics, enabling precise species identification through the analysis of short, standardized gene regions. This method provides a standardized, reproducible approach that complements and often surpasses traditional morphological identification and broader molecular diagnostics techniques. Unlike diagnostic PCR that targets specific known sequences, DNA barcoding discovers identity through comparison to reference libraries, making it exceptionally valuable for biodiversity studies, forensic analysis, and food safety testing [4] [30]. This guide details the complete workflow from specimen collection to sequence analysis while contextualizing its place within molecular biology research.

Core DNA Barcoding Workflow

The standard DNA barcoding process follows a systematic pathway to ensure reliable and reproducible specimen identification. The entire procedure, from sample collection to final identification, can be visualized as a coherent workflow [4] [31]:

Diagram 1: Complete DNA barcoding workflow from specimen to sequence identification.

Step 1: Experimental Design and Sample Collection

Effective DNA barcoding begins with careful planning. Researchers must define study objectives, select appropriate barcode markers for their target taxa, and establish quality control protocols [31]. Proper specimen collection involves using sterile tools to avoid cross-contamination and immediate preservation using methods appropriate for downstream applications—typically 95% ethanol, silica gel drying, or freezing at -20°C or lower [4] [31]. Comprehensive metadata including geographical location, collection date, and morphological descriptions should be recorded to support future reference library development.

Step 2: DNA Extraction and Quality Control

DNA extraction employs tissue-specific kits that effectively lyse cells and purify nucleic acids while removing inhibitors like polyphenols (common in plants) and polysaccharides (common in fungi) [32] [31]. The extraction process typically involves:

- Cell Lysis: Using mechanical disruption (e.g., bead beating) combined with chemical lysis buffers

- Purification: Column-based or magnetic bead-based separation of DNA from contaminants

- Elution: DNA recovery in buffer or molecular grade water [32]

Quality control measures include spectrophotometric analysis (A260/280 ratio of ~1.8-2.0 indicates pure DNA) and gel electrophoresis to confirm high molecular weight DNA [31]. Including extraction blanks controls for contamination during the process.

Step 3: PCR Amplification of Barcode Regions

Successful barcoding requires amplifying specific genomic regions using carefully selected primers. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) targets these standardized barcode regions with primers that flank variable sequences [4]. Key considerations include:

- Primer Design: Selecting taxa-specific primers that bind to conserved flanking regions

- Reaction Optimization: Adjusting annealing temperatures and cycle numbers for specific primer-template combinations

- Additives: Including BSA or DMSO to overcome inhibitors in difficult samples [31]

PCR success is verified through gel electrophoresis, where a single bright band at the expected amplicon size indicates specific amplification [4].

Step 4: Sequencing Technologies

Two main sequencing approaches dominate DNA barcoding applications, each with distinct advantages:

Sanger Sequencing: The conventional method for single-specimen barcoding, providing read lengths up to 1000bp with high accuracy for clean templates [33]. It requires relatively high DNA concentration (100-500ng) and produces a single consensus sequence per reaction [33].

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Enables massive parallel sequencing of multiple specimens simultaneously through DNA tagging (multiplexing) [33]. NGS platforms like Illumina and Oxford Nanopore are particularly valuable for:

- Metabarcoding of complex mixtures

- Degraded DNA samples (using mini-barcodes)

- High-throughput projects processing hundreds to thousands of specimens

- Detecting heteroplasmy, pseudogenes, and symbiont sequences [33]

Step 5: Data Analysis and Species Identification

The final stage transforms sequence data into species identifications through bioinformatics analysis. The process includes:

- Sequence Quality Control: Trimming low-quality bases, removing primer sequences, and contig assembly

- Database Query: Comparing unknown sequences against reference libraries using BLAST or specialized BOLD systems

- Interpretation: Evaluating match quality based on percent identity, coverage, and database reliability [31]

The Barcode of Life Data Systems (BOLD) provides curated records with voucher specimens and rich metadata, while GenBank offers broader taxonomic coverage [30] [31]. Responsible reporting includes acknowledging uncertainty when matches are borderline and using genus-level identification when species-level confidence is insufficient.

DNA Barcode Markers by Taxonomic Group

Different taxonomic groups require specific DNA barcode markers due to variations in evolutionary rates and genomic organization [4] [30] [31].

Table 1: Standard DNA Barcode Markers Across Major Biological Groups

| Taxonomic Group | Primary Barcode Marker(s) | Alternative Markers | Typical Amplicon Size | Resolution Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animals | Cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) | - | ~650 bp | High species-level resolution |

| Plants | rbcL + matK | ITS, trnH-psbA | 500-800 bp | Good genus-level, variable species-level |

| Fungi | Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) | - | 500-700 bp | High species-level resolution |

| General Purpose | ITS (for multiple kingdoms) | - | Variable | Dependent on taxonomic group |

Comparative Analysis: DNA Barcoding vs. Other Molecular Diagnostic Methods

DNA barcoding occupies a distinctive position within the landscape of molecular diagnostics, with specific advantages and limitations compared to other approaches.

Table 2: DNA Barcoding Compared to Other Molecular Diagnostic Methods

| Method | Primary Application | Target Specificity | Throughput | Cost per Sample | Technical Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Barcoding | Species identification | Unknown species discovery | Moderate to High | $5-$50 (varies with scale) | Moderate |

| Diagnostic PCR | Pathogen detection | Known specific targets | High | $2-$10 | Low to Moderate |

| qPCR | Quantification and detection | Known specific targets | High | $5-$15 | Moderate |

| Multiplex PCR | Detection of multiple targets | Known specific targets | High | $8-$20 | Moderate to High |

| DNA Microarrays | Parallel screening of many targets | Known specific targets | Very High | $50-$200 | High |

| Metabarcoding | Community profiling | Mixed species identification | Very High | $10-$100 (depends on scale) | High |

Advanced Protocol: Fusarium Species Identification Using Multilocus Barcoding

Recent research demonstrates how DNA barcoding can be enhanced for challenging taxonomic groups. A 2025 study on Fusarium species identification from post-harvest maize integrated four genomic regions for robust species differentiation within the Fusarium fujikuroi complex [32].

Experimental Methodology

Sample Collection and Preparation: 50 maize kernel samples collected from storage facilities in Bulgaria following ISO 24333:2009 protocols [32]

DNA Extraction:

- 5-day-old mycelium frozen at -20°C for 24 hours and pulverized with quartz sand

- Column-based DNA purification (Jena Bioscience Tissue DNA Preparation Kit)

- DNA concentration standardized to 10 ng/μL for all samples [32]

Multilocus PCR Amplification:

- Four genetic loci amplified: ITS1, IGS, TEF-1α, and β-TUB

- Reaction conditions: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, 30 cycles of (95°C for 30s, primer-specific annealing for 45s, 72°C for 1min), final extension at 72°C for 9min [32]

Multiplex PCR for Toxigenic Potential:

- Three separate multiplex reactions targeting toxin gene pairs: fum6/fum8, tri5/tri6, and tri5/zea2

- Enabled simultaneous screening for fumonisin, trichothecene, and zearalenone biosynthesis potential [32]

Results and Performance Data

The integrated approach successfully identified 17 Fusarium isolates with the following distribution: F. proliferatum (52.9%), F. verticillioides, F. oxysporum, F. fujikuroi, and F. subglutinans [32]. All isolates harbored at least one toxin biosynthesis gene, with 18% containing genes for both fumonisins and zearalenone [32]. The multilocus method provided significantly enhanced species resolution compared to single-locus barcoding, particularly for closely related taxa.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful DNA barcoding requires specific laboratory reagents and materials optimized for different sample types and taxonomic groups.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for DNA Barcoding Workflows

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Column-based kits (e.g., Jena Bioscience), CTAB protocol | Cellular lysis and DNA purification | CTAB methods preferred for polyphenol-rich plant tissues |

| PCR Master Mixes | Taq polymerase with optimized buffers | Amplification of barcode regions | BSA addition improves amplification from difficult samples |

| Primer Sets | LCO1490/HCO2198 (COI), ITS1/ITS4 (ITS) | Taxa-specific barcode amplification | Validated primers reduce optimization time |

| Sequencing Chemistries | BigDye Terminator v3.1 (Sanger) | DNA sequence determination | NGS library prep kits for high-throughput applications |

| Quality Control Tools | Spectrophotometers, gel electrophoresis systems | DNA quantity/quality assessment | Fragment analyzers for NGS library QC |

| Positive Controls | Verified specimens with known barcodes | Process validation | Essential for diagnostic and regulatory applications |

DNA barcoding represents a sophisticated molecular diagnostic tool that balances standardization with taxonomic flexibility. While conventional PCR methods target known sequences for specific detection, DNA barcoding's power lies in its ability to identify unknown specimens through comparison to reference libraries. The workflow detailed above—from careful specimen collection through rigorous data analysis—ensures reliable identifications across diverse applications. For challenging taxa like Fusarium, multilocus approaches significantly enhance resolution beyond single-locus barcoding [32]. As reference libraries expand and sequencing technologies become more accessible, DNA barcoding continues to transform species identification in research, conservation, and commercial applications.

In the evolving landscape of molecular diagnostics, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technologies remain foundational tools for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. While conventional PCR established the basic principle of DNA amplification, technological advancements have spawned a suite of sophisticated assays including real-time PCR, digital PCR, and multiplex PCR, each with distinct advantages and applications. This expansion of the PCR arsenal occurs alongside other powerful molecular techniques like DNA barcoding, a method for species identification based on DNA sequences. DNA barcoding utilizes a standardized short sequence of DNA (400–800 bp) that is specific to each species, creating a massive online digital library for classifying unidentified specimens [34] [11]. This guide objectively compares the performance, capabilities, and experimental applications of major PCR types and contrasts them with DNA barcoding, providing structured data and methodologies to inform your research choices.

Comparative Analysis of PCR Techniques and DNA Barcoding

The following table provides a high-level overview of the core principles, capabilities, and primary uses of each diagnostic method.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of PCR Assays and DNA Barcoding

| Method | Core Principle | Quantitative? | Key Advantage | Primary Application(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional PCR | End-point detection of amplified DNA after cycles. | No (semi-quantitative at best) [35]. | Simplicity and low cost; good for presence/absence detection [1] [35]. | Amplification of DNA for sequencing, genotyping, and cloning [35]. |

| Real-Time PCR (qPCR) | Measures PCR amplification in real-time during the exponential phase using fluorescent dyes or probes [1] [35]. | Yes (relative quantification) [35]. | Wide dynamic range; no post-PCR processing; high throughput [35]. | Gene expression quantitation, pathogen detection, SNP genotyping [35]. |

| Digital PCR (dPCR) | Partitions a sample into many individual reactions for absolute counting of target molecules [22] [35]. | Yes (absolute quantification) [35]. | No need for standard curves; superior precision; more tolerant to inhibitors [22] [35]. | Absolute viral load quantification, rare allele detection, NGS library quantification [35]. |

| Multiplex PCR | Amplification of multiple targets in a single reaction using multiple primer sets. | Varies (often qualitative, but can be quantitative in qPCR/dPCR formats). | High-throughput detection of multiple targets; saves sample and reagents [13] [8]. | Simultaneous detection of multiple pathogens or genetic markers [13] [36]. |

| DNA Barcoding | Uses a standardized short DNA sequence (e.g., COI gene) for identification via database matching [34] [11]. | No | Can identify unknown species without prior knowledge; high specificity [37] [11]. | Species identification, biodiversity studies, authentication of herbal products [34] [11]. |

Performance and Experimental Data

Quantitative Performance in Viral Load Analysis

A 2025 study directly compared the performance of digital PCR and real-time RT-PCR for quantifying respiratory viruses during the 2023–2024 tripledemic. The results underscore dPCR's superior accuracy, especially in samples with medium to high viral loads [22].

Table 2: Comparative Diagnostic Performance of dPCR vs. Real-Time RT-PCR in Viral Load Quantification [22]

| Virus | Superior Method (by Viral Load Category) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Influenza A | Digital PCR (High viral load) | Demonstrated greater accuracy and consistency. |

| Influenza B | Digital PCR (High viral load) | Demonstrated greater accuracy and consistency. |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Digital PCR (High viral load) | Demonstrated greater accuracy and consistency. |

| RSV | Digital PCR (Medium viral load) | Showed greater precision in quantifying intermediate viral levels. |

Identification Efficiency: Multiplex PCR vs. DNA Barcoding

A 2024 study on container-breeding mosquitoes provides a clear comparison between multiplex PCR and DNA barcoding, highlighting a key limitation of standard DNA barcoding with Sanger sequencing.

Table 3: Identification Success Rate: Multiplex PCR vs. DNA Barcoding [13] [36] [8]

| Method | Samples Identified (out of 2271) | Detection of Mixed-Species Samples | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiplex PCR | 1990 (87.6%) | Yes (47 samples detected) | Requires prior knowledge of target species for primer design. |

| DNA Barcoding | 1722 (75.8%) | No | Cannot identify multiple species in one sample using Sanger sequencing. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Comparative Viral Quantification with dPCR and Real-Time RT-PCR

This protocol is adapted from a 2025 study comparing dPCR and real-time RT-PCR for respiratory viruses [22].

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Viral Quantification Protocol

| Reagent/Kit | Function |

|---|---|

| KingFisher Flex system & MagMax Viral/Pathogen kit | Automated nucleic acid extraction [22]. |

| Allplex Respiratory Panel Assays (Seegene) | Multiplex real-time RT-PCR detection and Ct value determination [22]. |

| QIAcuity platform (Qiagen) | Nanowell-based digital PCR system for absolute quantification [22]. |

| QIAcuity Suite Software | Analyzes fluorescent signals and calculates absolute copy numbers [22]. |

Workflow Diagram: Viral Load Comparison Study

Methodology Details:

- Sample Collection and Preparation: A total of 123 respiratory samples (122 nasopharyngeal swabs and one bronchoalveolar lavage) were collected from symptomatic patients. Samples were stratified into high (Ct ≤ 25), medium (Ct 25.1–30), and low (Ct > 30) viral load categories based on initial real-time RT-PCR results [22].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: RNA was extracted using an automated platform (KingFisher Flex system) with the MagMax Viral/Pathogen kit to ensure purity and minimize PCR inhibitors [22].

- Real-Time RT-PCR Analysis: Multiplex real-time RT-PCR was performed using commercial respiratory panel kits (Allplex Respiratory Panel) on a CFX96 thermocycler. Cycle threshold (Ct) values were recorded for quantification relative to a standard curve [22].

- Digital PCR Analysis: Extracted RNA was analyzed on the QIAcuity platform using a five-target multiplex assay. The sample was partitioned into approximately 26,000 nanowells, and endpoint PCR was performed. The QIAcuity Suite software applied a Poisson statistical algorithm to the fraction of negative wells to determine the absolute copy number/μL of each target, without a standard curve [22].

- Data Analysis: Viral load quantification and consistency between the two methods were compared across the different viral load categories and virus types (Influenza A, Influenza B, RSV, SARS-CoV-2) using statistical analysis, including the Kruskal-Wallis test [22].

Protocol: Species Identification with Multiplex PCR and DNA Barcoding

This protocol is adapted from a 2024 study identifying Aedes mosquito species [13] [8].

Table 5: Key Research Reagents for Mosquito Identification Protocol

| Reagent/Kit | Function |

|---|---|

| Ovitrap (black container with wooden spatula) | Collection of mosquito eggs from the field [13] [8]. |

| innuPREP DNA Mini Kit / BioExtract SuperBall Kit | DNA extraction from homogenized egg samples [8]. |

| Species-Specific Primers (e.g., for Ae. albopictus) | Target conserved, species-specific genetic regions in multiplex PCR [8]. |

| mtCOI Primers | Amplify the mitochondrial Cytochrome C Oxidase subunit I gene for DNA barcoding [13] [8]. |

| Sanger Sequencing | Determines the nucleotide sequence of the mtCOI amplicon [13] [8]. |

Workflow Diagram: Mosquito Species Identification

Methodology Details:

- Sample Collection: Mosquito eggs were collected from ovitraps deployed across Austria. Eggs were morphologically identified where possible and stored at -80°C [8].

- DNA Extraction: All eggs from a single spatula were homogenized, and DNA was extracted using a commercial kit (e.g., innuPREP DNA Mini Kit) [8].

- Multiplex PCR: An adapted multiplex PCR protocol was used. The reaction mixture included a universal forward primer and multiple species-specific reverse primers designed to produce amplicons of distinct sizes for Ae. albopictus, Ae. japonicus, Ae. koreicus, and Ae. geniculatus. The PCR products were separated by gel electrophoresis, and species were identified based on the resulting band sizes [8].

- DNA Barcoding: A separate PCR was run to amplify a ~650 bp fragment of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase I (mtCOI) gene. The resulting amplicon was purified and sequenced using Sanger sequencing. The obtained sequence was compared to reference sequences in databases such as NCBI GenBank for species identification [13] [8].

- Data Analysis: The identification results from both the multiplex PCR and DNA barcoding were compared for all 2271 samples. The success rates of each method were calculated, and samples with discrepant results were further investigated [8].

The data demonstrates that the choice of molecular diagnostic tool is highly dependent on the specific research question. Digital PCR excels in applications requiring absolute quantification and high precision, such as viral load monitoring and assay validation, though it comes with higher costs and less automation than real-time PCR [22] [35]. Real-Time PCR remains the workhorse for relative quantification and high-throughput applications due to its wide dynamic range and established workflows [35]. Multiplex PCR offers clear efficiency advantages when testing for a predefined set of targets, saving time, reagents, and precious sample material [13] [8].

When contrasted with these PCR assays, DNA barcoding serves a different primary purpose: species identification. Its power lies in the ability to identify an unknown specimen by matching its sequence to a reference library, without needing to know the target species beforehand [37]. However, a significant limitation is its inability to reliably identify multiple species in a mixed sample using standard Sanger sequencing, a task where multiplex PCR shines [13] [8]. Consequently, DNA barcoding and various PCR formats are not mutually exclusive but are often complementary tools in the molecular diagnostics arsenal.

DNA barcoding has emerged as a transformative molecular tool for species identification, offering significant advantages over traditional methods in both herbal medicine authentication and food safety. This technique uses short, standardized DNA sequences from specific genes to uniquely identify organisms, functioning similarly to a supermarket barcode scanner identifying products [3]. The core principle relies on the "barcoding gap," where genetic differences between species exceed variations within a species, enabling precise identification [3] [38].

The application of DNA barcoding has expanded rapidly since its conceptualization in 2003, particularly in quality control fields where authenticating biological materials is crucial [26] [38]. In herbal medicine, it addresses challenges of product adulteration and mislabeling in complex polyherbal formulations [39] [40]. Similarly, in food safety, it provides a powerful solution for detecting species substitution and economic fraud in global supply chains [41] [42]. This review systematically compares DNA barcoding with other molecular diagnostic methods within a broader thesis on molecular diagnostics PCR research, providing experimental data and protocols to guide researchers and drug development professionals in method selection.

Principles and Workflow of DNA Barcoding

Fundamental Concepts and Standard Markers

DNA barcoding utilizes specific genomic regions that exhibit sufficient genetic variation to distinguish between species while maintaining enough conservation to allow amplification with universal primers [3] [34]. The selection of an appropriate barcode region depends on the taxonomic group being identified, as no single gene region works universally across all organisms [3].

Table 1: Standard DNA Barcode Markers Across Taxonomic Groups

| Taxonomic Group | Primary Barcode Marker(s) | Alternative Markers | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animals | Cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) [3] | Cytb, 12S, 16S [3] [42] | High interspecific variability, maternal inheritance, multiple copies per cell [42] |

| Plants | matK, rbcL [3] [34] | ITS, trnH-psbA [3] [40] | Low mutation rates in mitochondrial DNA necessitate chloroplast markers [3] |

| Fungi | Internal transcribed spacer (ITS) [3] | 28S LSU rRNA [3] | High variability, established use in mycological taxonomy [3] |

| Bacteria | 16S rRNA [3] | cpn60, rpoB [3] | Highly conserved with variable regions [3] |

| Protists | V4 region of 18S rRNA gene [3] | D1-D2 regions of 28S rDNA, COI [3] | Group-specific approaches often required |

The mitochondrial COI gene serves as the standard barcode for animals due to its high evolutionary rate and sufficient variation to distinguish even closely related species [3] [38]. For plants, however, mitochondrial genes evolve too slowly, necessitating chloroplast markers such as matK and rbcL, sometimes supplemented with ITS or trnH-psbA for better resolution [3] [34] [40]. Fungi typically utilize the ITS region of ribosomal DNA, while bacteria and protists require different markers such as 16S rRNA and 18S rRNA genes, respectively [3].

Standardized Laboratory Workflow

The DNA barcoding process follows a standardized workflow from sample collection to sequence analysis, with specific adaptations based on sample type and condition.

Figure 1: DNA Barcoding Workflow. The process involves sample collection, DNA extraction, PCR amplification, sequencing, bioinformatic analysis, and species identification against reference databases.

Sample Collection and Preservation

Sample collection strategies vary based on the material being tested. For herbal products, representative samples of the manufactured product are collected, while for food authentication, the actual product samples are obtained [39] [42]. Preservation is crucial to prevent DNA degradation. Animal tissues are typically preserved in 70-95% ethanol, plant materials desiccated with silica gel, and environmental samples (eDNA) filtered and preserved in Longmire's buffer or ethanol [3] [38]. Proper documentation including GPS coordinates, collection date, and collector information is essential for reference specimens [38].

DNA Extraction and Amplification

DNA extraction methods must be optimized for the sample type. Commercial silica-based kits (e.g., Qiagen DNeasy kits) are widely used for their efficiency and purity [38]. For plant materials rich in polysaccharides and secondary metabolites, the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method is often preferred [38]. The extracted DNA must be of sufficient quality and quantity for amplification, which can be challenging in processed products where DNA is fragmented or degraded [39] [41].

PCR amplification uses primers specific to the barcode region of interest. Universal primers are preferred but taxon-specific primers may be necessary for certain groups [3]. For conventional barcoding, the target fragment size is typically 400-800 base pairs, while for metabarcoding or degraded DNA, smaller fragments (<200 bp) are targeted [3].

Sequencing and Analysis

Sanger sequencing remains the standard for individual barcoding, while next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms are essential for metabarcoding applications [3] [39]. The resulting sequences are processed through bioinformatic pipelines that include quality filtering, sequence alignment, and comparison against reference databases such as the Barcode of Life Data System (BOLD) or GenBank [3] [38]. Species identification is achieved when the query sequence shows high similarity to a reference sequence, with statistical support for the match [3].

DNA Barcoding in Herbal Medicine Authentication

Experimental Approaches and Case Studies

DNA barcoding has become particularly valuable for authenticating herbal medicines, where morphological identification is impossible in processed materials. The approach has evolved from single-locus barcoding to multi-locus and metabarcoding strategies for complex polyherbal formulations.

Table 2: DNA Barcoding Applications in Herbal Medicine Authentication

| Study Focus | Method Used | Key Findings | Adulteration/Mislabeling Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Renshen Jianpi Wan (RSJPW) authentication [40] | DNA metabarcoding with ITS2 + psbA-trnH | Detected 10/11 declared ingredients; key fungal ingredient (Poria cocos) consistently undetectable | Frequent detection of non-prescribed species from Fabaceae, Apiaceae, Brassicaceae |

| Commercial Chinese polyherbal preparations [39] | DNA metabarcoding with multiple barcodes | High variability in ingredient detection; common substitution of declared species | 30-70% adulteration in many products; over 80% in some studies |

| Rhodiola rosea products [39] | Multi-locus barcoding (rbcL, trnH-psbA, matK, ITS) | ITS region optimal for discrimination between R. rosea and other Rhodiola species | Widespread species substitution in commercial products |

| Traditional Chinese Medicine Baitouweng [39] | ITS2 barcoding with PCR-RFLP | Effective differentiation of Pulsatilla species from adulterants | 98% substitution in commercial products |

A 2025 case study on Renshen Jianpi Wan (RSJPW), a classical Chinese polyherbal preparation containing 11 botanical drugs, demonstrates both the power and limitations of DNA metabarcoding for quality control [40]. Researchers analyzed 56 commercial products alongside eight laboratory-prepared reference samples using a dual-marker approach combining ITS2 and psbA-trnH regions. The highest detection rate was 10 out of 11 prescribed ingredients in a single sample, but the key fungal ingredient Poria cocos was consistently undetectable, likely due to DNA degradation during processing and challenges in extracting fungal DNA from complex matrices [40]. The study also frequently detected multiple high-abundance non-prescribed species from Fabaceae, Apiaceae, and Brassicaceae families as potential contaminants or adulterants [40].

For single-ingredient herbal products, DNA barcoding has revealed startling rates of adulteration. In traditional Chinese medicine Baitouweng products, which should contain Pulsatilla chinensis, ITS2 barcoding detected a 98% substitution rate with other species [39]. Similarly, Rhodiola rosea products showed widespread species substitution, leading to the development of specific PCR assays for quality verification [39].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Herbal Medicine Authentication

The following protocol for authenticating herbal medicines using DNA metabarcoding is adapted from Zhou et al. (2025) and other recent studies [39] [40]:

Sample Preparation: Grind 100 mg of herbal product to a fine powder using a sterile mortar and pestle or bead mill. Include both test samples and reference materials for comparison.

DNA Extraction: Use the CTAB method or commercial kit (e.g., Qiagen DNeasy Plant Mini Kit) with modifications for processed samples. Add polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) to binding buffer to remove polyphenols. Perform extraction in duplicate to account for potential heterogeneity.

DNA Quantification and Quality Assessment: Measure DNA concentration using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay). Verify quality through agarose gel electrophoresis or spectrophotometric ratios (A260/A280 ≈ 1.8-2.0).

PCR Amplification: Amplify barcode regions using multiplex PCR approach. For plants, use primers for ITS2, matK, rbcL, and trnH-psbA. Reaction conditions: 25 μL volume containing 1× PCR buffer, 2.5 mM MgCl₂, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.2 μM each primer, 1 U DNA polymerase, and 10-50 ng template DNA. Cycling parameters: 95°C for 5 min; 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 50-58°C (primer-dependent) for 40 s, 72°C for 1 min; final extension at 72°C for 7 min.

Library Preparation and Sequencing: Purify PCR products using magnetic beads. Prepare sequencing libraries with dual indexing to enable sample multiplexing. Quality control using Bioanalyzer or Tapestation. Sequence on Illumina MiSeq or similar platform with 2×250 bp paired-end reads.

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Demultiplex sequences based on dual indexes.

- Merge paired-end reads, quality filter (Q-score >30), and remove chimeras.

- Cluster sequences into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 97% similarity.

- Compare OTUs against reference databases (BOLD, GenBank) using BLAST with minimum 97% identity threshold for species assignment.

- Perform taxonomic assignment with QIIME2 or OBITools pipelines.

Data Interpretation: Compare detected species against declared ingredients. Report potential adulterants or contaminants, considering relative read abundance as a semi-quantitative measure of composition.

DNA Barcoding in Food Safety

Applications in Food Fraud Detection

DNA barcoding has become an essential tool for combating food fraud, which costs the global food industry an estimated $30-40 billion annually [41]. The technology detects species substitution, mislabeling, and economic adulteration across various food sectors.

Table 3: DNA Barcoding Applications in Food Authentication

| Food Category | Common Fraud Issues | Standard Barcode(s) | Detection Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seafood [41] | Species substitution, mislabeling of premium species | COI, 16S rRNA, Cyt b | Identification of endangered species, cheaper substitutes |

| Meat Products [42] | Substitution with cheaper meats, undeclared species | COI, Cyt b, 12S rRNA | Detection of lymph meat, pork in halal products, species mixtures |

| Herbal Supplements [39] [40] | Species substitution, undeclared fillers, adulterants | ITS2, matK, rbcL, trnH-psbA | Identification of toxic substitutes, low-cost fillers |

| Processed Foods [41] | Complex adulteration in highly processed products | Short barcode fragments (<200 bp) | Detection in cooked, canned, or powdered products |

In the seafood industry, DNA barcoding has revealed widespread mislabeling, where premium fish species are substituted with cheaper alternatives [41]. For example, studies have identified endangered shark species in generic "fish" products and substitution of expensive tuna with lower-value species [41]. The COI gene serves as the primary barcode, with 16S rRNA and Cyt b as supplementary markers, especially for processed products where DNA fragmentation occurs [41] [42].

In meat authentication, DNA barcoding detects adulteration such as the addition of pork to halal products or substitution of prime cuts with lower-quality meats [42]. A concerning case revealed in 2024 involved the use of lymph meat in pre-prepared meals, posing significant health risks to consumers [42]. Mitochondrial genes (COI, Cyt b, 12S rRNA) are standard for species identification, while nuclear markers (SSRs, STRs, SNPs) enable individual identification and breed tracing [42].

Comparison of Detection Methods for Food Authentication

Various molecular methods are available for food authentication, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

Table 4: Comparison of Molecular Methods for Food Authentication

| Method | Detection Principle | Sensitivity | Multiplexing Capacity | Cost per Sample | Suitability for Processed Foods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Barcoding [41] [42] | Sequencing of specific gene regions | High (can detect <1% adulteration) | Moderate (with metabarcoding) | $10-50 | Good to Excellent (with short fragments) |

| Real-time PCR [42] | Target-specific amplification with fluorescence detection | Very High (can detect <0.1% adulteration) | Limited (usually 4-6 targets) | $5-15 | Good |

| LAMP [41] | Isothermal amplification with visual detection | High | Very Limited | $2-8 | Moderate |

| Metabarcoding [39] [41] | High-throughput sequencing of barcode regions | Moderate to High | Excellent (100+ species simultaneously) | $50-150 | Good to Excellent |

| Microarrays [41] | Hybridization to species-specific probes | Moderate | Good (50-100 targets) | $30-80 | Moderate |

DNA barcoding offers a balanced combination of accuracy, sensitivity, and applicability to processed foods, particularly when combined with emerging technologies like blockchain and IoT sensors for enhanced traceability [41]. While real-time PCR provides higher sensitivity for specific targets, DNA barcoding enables broader species identification without prior knowledge of potential adulterants [42]. Metabarcoding extends this capability further by simultaneously identifying multiple species in complex mixtures, making it ideal for polyherbal formulations and multi-ingredient food products [39] [41].

Comparative Analysis with Other Molecular Diagnostic Methods

Performance Metrics in Clinical Diagnostics