DNA Barcoding vs. Morphological Analysis: A Modern Paradigm for Parasite Identification in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of DNA barcoding and traditional morphological identification for parasites, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

DNA Barcoding vs. Morphological Analysis: A Modern Paradigm for Parasite Identification in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of DNA barcoding and traditional morphological identification for parasites, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of both methods, delves into specific methodological protocols and their applications in drug discovery and diagnostics, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, and presents validation studies comparing their accuracy and efficiency. The synthesis aims to guide the selection and integration of these techniques to enhance precision in parasite research and therapeutic development.

The Building Blocks of Identification: Unpacking Morphological and DNA Barcoding Principles

Core Principles of Traditional Morphological Parasite Identification

For centuries, the identification of parasites through morphological examination has served as the cornerstone of parasitological diagnosis and research. This approach relies on the visual interpretation of parasite characteristics—including size, shape, internal structures, and staining properties—to differentiate species and determine infections. Despite the emergence of sophisticated molecular techniques like DNA barcoding, morphological identification remains fundamentally important in both clinical and research settings, particularly in resource-limited areas where it continues to provide a cost-effective and immediate diagnostic solution [1] [2]. The enduring relevance of morphological analysis is evidenced by its designation as the "gold standard" for numerous parasitic infections, such as malaria diagnosis via blood film examination, where it enables not only species identification but also the determination of parasite density crucial for clinical management [1].

The core premise of morphological identification rests on the consistent and discernible physical characteristics exhibited by different parasite species across their various life cycle stages. When performed by experienced diagnosticians, this method provides a reliable means of identification that requires minimal equipment compared to molecular techniques. However, the method is not without limitations, including its dependence on specimen quality, observer expertise, and the inherent challenges in distinguishing morphologically similar species or detecting low-level infections [1] [3]. This article examines the core principles, techniques, and applications of traditional morphological parasite identification, providing a comparative framework against which emerging molecular methods can be evaluated.

Fundamental Principles and Diagnostic Approaches

Core Morphological Concepts in Parasite Identification

Morphological identification of parasites is governed by several foundational principles that guide diagnosticians in accurate specimen interpretation. The first principle centers on life cycle stage recognition, as many parasites display markedly different morphological characteristics across their developmental stages. For intestinal protozoa, this typically involves distinguishing between the actively replicating but fragile trophozoite stage and the environmentally resistant, infectious cyst stage [4]. In helminths, identification may involve recognizing eggs, larvae, or adult forms, each with distinct morphological features.

The second principle involves the systematic observation of key diagnostic structures. For amoeboid parasites, critical features include nuclear characteristics (peripheral chromatin distribution and karyosomal chromatin appearance), cytoplasmic inclusions (presence of red blood cells, bacteria, or yeast), and overall size and motility patterns [4]. For flagellates, diagnosticians examine structures such as flagella number and insertion, undulating membranes, and adhesive discs. These characteristics remain consistent within species but vary sufficiently between species to allow differentiation when examined by trained personnel.

A third principle involves understanding staining affinities and optical properties of parasitic structures. Different components of parasites interact distinctively with various stains, providing critical diagnostic information. Chromatin structures typically stain deeply with basic dyes, while cytoplasmic elements may show variable affinity. The use of temporary stains like iodine helps visualize glycogen vacuoles and nuclear structures in cysts, while permanent stains provide detailed morphological information about internal structures [5] [4]. Refractivity—how light passes through parasitic structures—also provides important clues, particularly in unstained wet preparations where the presence of chromatoid bodies with characteristic shapes (elongated with rounded ends in Entamoeba histolytica versus splinter-like with pointed ends in Entamoeba coli) can aid identification [5] [4].

Essential Staining Techniques and Their Applications

Staining techniques enhance the visibility of key morphological features and are categorized based on their permanence and application. The table below summarizes the primary staining methods used in parasitology and their diagnostic utility:

Table 1: Staining Techniques for Morphological Parasite Identification

| Stain Category | Specific Types | Primary Applications | Key Diagnostic Features Enhanced |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporary Stains | Iodine, Buffered Methylene Blue, Neutral Red | Rapid examination of wet mounts | Glycogen vacuoles, nuclear structure, flagella, inclusion bodies |

| Permanent Stains | Trichrome, Iron Hematoxylin, Giemsa | Detailed morphological study, specimen preservation | Nuclear detail, cytoplasmic inclusions, intracellular structures |

| Specialized Stains | Acid-fast stains, Chromotrope-based stains | Specific parasite groups | Oocyst walls of coccidia, microsporidial spores, Cryptosporidium |

Iodine-based temporary stains are particularly valuable for demonstrating glycogen masses in cysts and revealing nuclear number and structure, which are critical for differentiating species like Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba coli [4]. Permanent staining methods, such as Trichrome and Iron Hematoxylin, provide exceptional detail of internal structures, allowing for definitive species identification based on nuclear characteristics and cytoplasmic inclusions [3] [4]. Specialized stains like the acid-fast method are essential for detecting particularly challenging organisms such as Cryptosporidium oocysts, which might otherwise be missed in routine examinations [4].

The mechanisms through which these stains interact with parasite structures involve complex physicochemical processes that are incompletely understood [5]. What is empirically established is that different staining protocols aim to maximize contrast between parasitic elements and background fecal material, a process described as differentiating "background from foreground" in the fecal smear [5]. This contrast enhancement facilitates the recognition of diagnostic features that might otherwise be obscured in unstained preparations.

Standardized Morphological Identification Workflows

The accurate morphological identification of parasites follows systematic procedures that vary depending on specimen type and suspected parasites. The workflow below illustrates the general process for stool specimen examination, one of the most common applications of morphological parasitology:

Specimen Processing and Examination Procedures

The diagnostic process begins with proper specimen collection and handling, as the integrity of parasitic structures is highly dependent on timely and appropriate preservation [3]. Fresh specimens are preferred for observing motility in trophozoites, while preserved specimens are adequate for cyst identification and concentration procedures. Gross examination of specimens provides initial clues about potential parasitic infections; for example, the presence of blood or mucus suggests possible invasive pathogens like Entamoeba histolytica or Balantidium coli [3].

The direct wet mount represents the most rapid diagnostic approach, allowing immediate assessment of specimen adequacy and potential detection of motile trophozoites. Saline preparations preserve motility and enable observation of characteristic movement patterns—the directional, progressive motility with hyaline pseudopods in Entamoeba histolytica versus the sluggish, non-progressive motility with blunt pseudopods in Entamoeba coli [4]. Iodine wet mounts highlight nuclear features and glycogen masses in cysts, providing critical diagnostic information.

Concentration techniques (such as formalin-ethyl acetate sedimentation or zinc sulfate flotation) increase diagnostic sensitivity by concentrating parasitic forms from larger stool volumes [3]. These procedures are particularly valuable for detecting low-intensity infections where organisms might be too scarce to visualize in direct preparations alone. Following concentration, permanent staining creates a durable preparation that allows detailed study of morphological features under high magnification, facilitating definitive species identification based on nuclear structure, cytoplasmic characteristics, and inclusion bodies [3] [4].

Microscopy and Interpretation Guidelines

Systematic microscopic examination follows a standardized approach to ensure comprehensive specimen evaluation. Initial screening using the 10x objective allows rapid scanning of the entire preparation for detecting parasitic forms and assessing overall specimen characteristics. Subsequent examination under high-power (40x) and oil immersion (100x) objectives enables detailed morphological assessment of any suspected parasites [1] [3].

The identification process involves methodical comparison of observed structures against established morphological criteria, with particular attention to:

- Size measurements: Using micrometer calibration to determine if structures fall within species-specific ranges [4]

- Nuclear characteristics: Number, peripheral chromatin distribution, karyosomal appearance [4]

- Cytoplasmic features: Appearance (finely versus coarsely granular), presence of inclusions (red blood cells, bacteria, yeast) [4]

- Specialized structures: Flagella, undulating membranes, chromatoid bodies, glycogen vacuoles [4]

For blood parasites like malaria, examination of both thick and thin blood films follows similar principles—thick films for sensitive parasite detection and thin films for detailed morphological study and species identification based on staining characteristics, parasite stages, and infected red cell morphology [1]. The entire process requires considerable technical expertise, as morphological identification is classified as a high-complexity procedure under clinical laboratory regulations [3].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful morphological identification depends on properly equipped laboratory facilities and specific reagent systems. The following table details essential materials required for comprehensive parasitological examination:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Morphological Identification

| Category | Specific Items | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collection & Preservation | Formalin, PVA, SAF vials | Preserve morphological integrity | Choice affects available testing options |

| Staining Reagents | Iodine, Trichrome, Giemsa, Acid-fast stains | Enhance structural visualization | Staining protocols require quality control |

| Microscopy Supplies | Microscope with oil immersion, Slides, Coverslips | Specimen examination | 100x oil immersion objective essential |

| Concentration Materials | Formalin-ethyl acetate, Centrifuge, Filters | Concentrate scarce organisms | Increases diagnostic sensitivity |

| Reference Materials | Morphological atlases, Digital image libraries | Comparative identification | Essential for accurate species differentiation |

The selection of preservation methods significantly impacts subsequent morphological analyses. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) preservation is preferred for protozoa as it simultaneously fixes specimens and provides appropriate consistency for staining, while formalin-based preservatives are adequate for helminth eggs and larvae [3]. Staining systems must be properly quality-controlled, as aging stains or improper pH can diminish morphological detail; for example, trichrome stain must maintain proper pH to effectively differentiate nuclear and cytoplasmic structures [3].

Microscopy equipment represents the most significant capital investment for morphological identification, requiring high-quality light microscopes with 100x oil immersion objectives capable of resolving fine nuclear details [1] [3]. For malaria diagnosis, examination of 200-300 oil immersion fields may be necessary before declaring a specimen negative, particularly in low-parasitemia infections or cases with partial chemoprophylaxis [1]. Reference collections of well-characterized specimens and digital image libraries provide crucial comparative material for accurate identification, helping mitigate the interpretive subjectivity inherent in morphological analysis [5].

Performance Assessment and Comparative Data

When evaluated against molecular reference methods, morphological identification demonstrates variable performance characteristics depending on parasite group, specimen quality, and examiner expertise. The following table summarizes comparative performance data across different parasite categories:

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Morphological Identification

| Parasite Category | Sensitivity Range | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intestinal Protozoa | ~51-95% (varies by species) | Cost-effective, provides immediate results | Requires multiple specimens, expertise-dependent |

| Blood Parasites (Malaria) | ~50-100 parasites/μL (detection limit) | Quantification possible, species differentiation | Sensitivity decreases with low parasitemia |

| Helminth Eggs | ~85-95% (with concentration) | Simple equipment needs, high specificity | Irregular egg shedding affects sensitivity |

| Microsporidia | ~30-50% (with special stains) | Detects unexpected pathogens | Requires specialized staining, low sensitivity |

For intestinal protozoa, performance varies substantially based on parasite load, with markedly reduced sensitivity in chronic or low-intensity infections [3]. Concentration techniques improve detection for many helminth eggs and protozoan cysts, but may be less effective for fragile trophozoites which are better detected in permanent stained smears [3]. In malaria diagnosis, skilled microscopists can achieve detection thresholds of approximately 50-100 parasites/μL of blood, with species identification accuracy exceeding 90% in experienced hands [1].

Several factors significantly impact morphological identification performance. Specimen quality profoundly affects outcomes, with delayed processing leading to diagnostic degradation of fragile trophozoites [3]. Examiner expertise represents perhaps the most significant variable, with studies demonstrating substantial inter-technician variability, particularly for less common parasites or atypical morphological presentations [1] [3]. This expertise dependency is reflected in the classification of parasitological procedures as high-complexity tests requiring extensive training and experience [3].

Integration with Modern Diagnostic Approaches

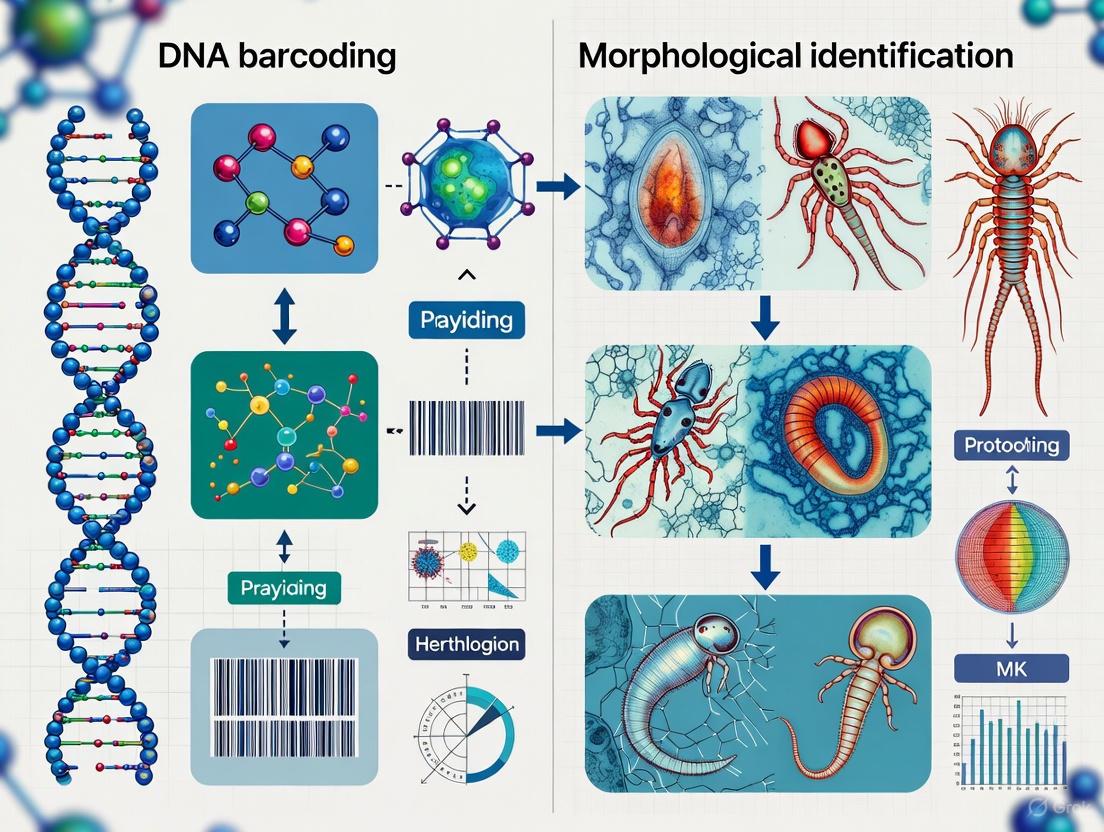

The evolving diagnostic landscape increasingly favors integrated approaches that combine traditional morphological expertise with advanced technologies. This hybrid model leverages the respective strengths of each method while mitigating their individual limitations. The conceptual relationship between these approaches is illustrated below:

Morphological and molecular methods exhibit complementary strengths that make them particularly powerful when used in concert. Traditional morphology provides a broad, unbiased screening approach capable of detecting unexpected pathogens without prior suspicion, while DNA barcoding offers exceptional specificity for distinguishing morphologically similar species [6] [7]. This complementary relationship is especially valuable for complex taxonomic groups where morphological differentiation challenges even experienced diagnosticians, such as the Entamoeba genus or helminth larvae [6] [7].

The integration of these approaches follows several practical pathways. Morphology often serves as an initial screening tool, with molecular methods providing definitive confirmation for morphologically ambiguous cases [7]. Conversely, DNA barcoding can rapidly screen large specimen collections, with morphological examination reserved for specimens yielding unexpected genetic results or representing potential new species [6] [8]. This bidirectional validation enhances overall diagnostic accuracy while simultaneously building reference databases that bridge morphological and genetic information.

Emerging technologies promise to further enhance traditional morphological approaches. Digital imaging and artificial intelligence are being developed to reduce interpretive subjectivity in morphological analysis, with studies demonstrating 98.8-99.0% precision in automated parasite detection systems [2]. Geometric morphometrics applies statistical shape analysis to quantify subtle morphological variations that may elude visual assessment, achieving 94.0-100.0% accuracy in species discrimination [2]. These technological enhancements preserve the accessibility and cost structure of morphological methods while addressing their primary limitations related to subjective interpretation.

Traditional morphological parasite identification remains an essential component of parasitological practice, providing a cost-effective, immediately actionable diagnostic method that continues to serve as the gold standard for numerous parasitic infections. Its core principles—based on systematic observation of diagnostic morphological features enhanced by appropriate staining techniques—have demonstrated remarkable resilience despite the emergence of sophisticated molecular alternatives. The future of morphological identification lies not in competition with molecular methods, but in strategic integration with them, creating hybrid diagnostic approaches that leverage the respective strengths of each technology. For researchers and clinical laboratories, maintaining morphological expertise remains imperative, both as a practical diagnostic tool and as a fundamental discipline that provides crucial context for interpreting molecular data. As technological advancements like digital imaging and artificial intelligence continue to evolve, they promise to enhance the precision and objectivity of morphological analysis while preserving its essential character as a direct observational science.

The accurate identification of species is a cornerstone of biological research, with profound implications for biodiversity conservation, pharmaceutical discovery, and ecosystem monitoring. For centuries, morphological identification—the visual analysis of physical characteristics—served as the primary method for species classification. However, this approach faces significant challenges, including phenotypic plasticity, the need for highly specialized taxonomic expertise, and difficulties in identifying larval, embryonic, or fragmentary specimens [6]. In response to these limitations, DNA barcoding has emerged as a powerful molecular tool that uses standardized short genetic sequences to discriminate between species, revolutionizing the field of taxonomic identification [9].

This paradigm shift is particularly relevant in pharmaceutical and bioprospecting contexts, where the accurate identification of source organisms is critical. For instance, plants in the genus Syringa are valued not only for their ornamental qualities but also as sources of diverse chemical constituents used in medical and cosmetic applications. The chemical composition varies significantly among different Syringa species, creating a pressing need for precise identification methods to prevent adulteration in raw material procurement for traditional medicines [9]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of DNA barcoding and morphological identification methods, examining their respective performance characteristics, experimental protocols, and applications in research and drug development.

Principles and Genetic Architecture of DNA Barcoding

Core Genetic Markers for Taxonomic Groups

DNA barcoding relies on standardized genetic markers that provide sufficient sequence variation to distinguish between species while being conserved enough for universal amplification. These markers differ across major taxonomic groups, with researchers selecting appropriate gene regions based on the target organisms.

Table 1: Standard DNA Barcode Regions for Major Organism Groups

| Organism Group | Primary Barcode Markers | Additional/Complementary Markers |

|---|---|---|

| Animals | Cytochrome c Oxidase I (COI) [10] [6] | Cytochrome b (cyt b), 18S ribosomal RNA [11] |

| Plants | ITS2, matK, rbcL [9] | psbA-trnH, trnL-trnF, trnL intron [9] |

| Plants (Chloroplast) | rbcL, matK [9] | psbA-trnH, trnL-trnF, trnC-petN [9] |

The COI gene has become the universal standard for animal identification due to its high mutation rate, which provides sufficient interspecific variability while maintaining minimal intraspecific variation. In plants, the selection of barcode markers is more complex due to slower evolutionary rates in chloroplast genomes, often necessitating multi-locus approaches combining nuclear and chloroplast regions for reliable discrimination [9]. For example, in Syringa species identification, the combination of ITS2 + psbA-trnH + trnL-trnF achieved an identification rate of 93.6%, significantly outperforming single-marker approaches [9].

Workflow and Mechanism of Action

The DNA barcoding process follows a standardized workflow from sample collection to species identification, with quality control measures at each stage to ensure reliability. The following diagram illustrates this integrated process:

Diagram 1: DNA Barcoding Workflow (47 characters)

The fundamental principle underlying DNA barcoding is the "barcoding gap"—the phenomenon where genetic differences between species exceed variation within species. This divergence creates distinct genetic clusters that computational algorithms can identify, enabling species-level discrimination. The Barcode of Life Data System (BOLD) serves as the primary repository and analysis platform, employing the Barcode Index Number (BIN) system to assign operational taxonomic units that typically correspond to biological species [10].

Performance Comparison: DNA Barcoding vs. Morphological Identification

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Direct comparative studies reveal significant differences in the performance characteristics of DNA barcoding and morphological identification across multiple metrics.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Identification Methods

| Performance Metric | DNA Barcoding | Morphological Identification |

|---|---|---|

| Species-Level Identification Rate | 93.6% for Syringa with combined markers [9] | Highly variable; as low as 13.5% for larval fish by expert taxonomists [6] |

| Genus-Level Identification Rate | 96.6% for larval fish [6] | 41.1% for larval fish across five laboratories [6] |

| Family-Level Identification Rate | 96.6% for larval fish [6] | 80.1% for larval fish across five laboratories [6] |

| Capability with Damaged Specimens | Effective identification of 35 out of 37 damaged larval fish [6] | 0% identification rate for damaged specimens [6] |

| Embryo/Larval Identification | Successful identification of 103 fish embryos [6] | Not possible due to lack of morphological features [6] |

| Cost Efficiency | More cost-effective for large-scale monitoring [6] [12] | Requires highly trained specialists, increasing costs [6] |

The data demonstrate DNA barcoding's particular advantage in challenging identification scenarios, including larval stages, damaged specimens, and closely related species where morphological characters are limited or convergent. In one study of larval fish identification, the consistency between five morphological taxonomy laboratories was only 13.5% at the species level, compared to 96.6% genus-level and family-level consistency with DNA barcoding [6].

Despite its advantages, DNA barcoding faces several technical and practical challenges that researchers must consider in experimental design:

Database-Dependent Accuracy: The identification reliability is directly proportional to reference database completeness and quality. In one empirical test, more than half of butterfly species encountered problems in obtaining correct scientific names due to errors in the BOLD database [10].

Resolution Limitations with Recent Radiations: Recently diverged species complexes, such as fish in the genus Coregonus, may show insufficient genetic differentiation in standard barcode regions, resulting in shared haplotypes between morphologically distinct species [6].

Technical Failures: PCR amplification failures affected 23 larval fish specimens (3.5% of samples) in one study, preventing barcode sequence generation despite morphological identifiability [6].

Taxonomic Ambiguity: DNA barcoding can reveal cryptic species or populations that challenge existing taxonomic frameworks, requiring integrated approaches with morphology and ecology for resolution [10].

Morphological identification maintains advantages in certain contexts, particularly for preliminary field assessments, when specialized taxonomic expertise is available, and for distinguishing species with recent divergence where genetic markers show insufficient differentiation.

Experimental Protocols for DNA Barcoding

Standard Laboratory Workflow

The following protocol outlines the core DNA barcoding procedure, with specific examples from published studies:

Sample Collection and Preservation

- Tissue Sampling: Collect 5-10mg of tissue (muscle, leaf, liver) using sterile instruments. For endangered species, non-lethal sampling (feathers, hair, buccal swabs) is recommended.

- Preservation: Store samples in 95-100% ethanol at -20°C for long-term preservation. For field collections, DNA/RNA shield stabilization solutions prevent degradation.

DNA Extraction

- Method Selection: Use CTAB protocol for plants [10] or commercial kits (DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit) for animal tissues.

- Quality Control: Verify DNA integrity via agarose gel electrophoresis and quantify using spectrophotometry (Nanodrop) or fluorometry (Qubit).

PCR Amplification

- Primer Design: Select appropriate barcode markers for target taxa (Table 1). For example:

- Reaction Setup: 15μL reaction volume containing: 9.9μL ddH₂0, 0.3μL of each primer (10μM), 3μL ScreenMix, and 1.5μL template DNA [10]

- Thermocycling Conditions: Initial denaturation at 94°C for 3min; 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30s, annealing at 50-55°C for 30s, extension at 72°C for 45s; final extension at 72°C for 10min [10]

Sequencing and Analysis

- Sequencing Method: Sanger sequencing for single specimens; nanopore sequencing (MinION) for high-throughput in situ applications [11]

- Data Processing: Trim sequences for quality, align using MUSCLE or ClustalW, perform genetic distance calculations (K2P), and construct phylogenetic trees (Neighbor-Joining, Maximum Likelihood) [9]

- Database Submission: Compare sequences against BOLD and GenBank using BLAST, and submit high-quality barcodes to public repositories

Advanced Integrated Methodologies

For taxonomically complex groups, iterative taxonomy approaches that combine morphological and molecular methods yield the most robust identifications. This integrated methodology includes:

Initial Morphological Assessment: Document diagnostic characters (e.g., leaf shape and base, inflorescence structure for plants; meristic counts for fish) [9] [13]

Multi-Locus Barcoding: Combine complementary markers to increase resolution, such as:

Phylogenetic Analysis: Construct trees with reference sequences to validate monophyly of putative species groups

Morphological Re-evaluation: Re-examine specimens in light of molecular results to identify previously overlooked diagnostic characters

This integrated approach significantly enhances identification rates. In a study of marine gastropods, combining all genetic markers improved species-level identification to 79% compared to 62% with COI alone, while also enabling the correlation of molecular groups with morphological synapomorphies [13].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful DNA barcoding requires specific laboratory reagents and materials optimized for different sample types and experimental conditions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for DNA Barcoding

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CTAB Extraction Buffer | DNA extraction from polysaccharide-rich tissues | Essential for plants and fungi; contains CTAB, NaCl, EDTA, Tris-HCl, β-mercaptoethanol [10] |

| Proteinase K | Protein digestion during DNA extraction | Improves yield from animal tissues; standard concentration 100μg/mL |

| ScreenMix | PCR amplification | Pre-mixed master mix containing polymerase, dNTPs, buffer; enables standardized amplification [10] |

| LEP Primers | COI amplification | F1 (5′-ATTCAACCAATCATAAAGATAT-3′) and R1 (5′-TAAACTTTCTGGATGTCCAAAAA-3′) for Lepidoptera and other arthropods [10] |

| ITS2 Primers | Nuclear marker amplification | Plant-specific primers for the ITS2 region; universal primers require taxon-specific optimization [9] |

| Agarose | Gel electrophoresis | Quality assessment of DNA extracts and PCR products; standard 1-2% gels with ethidium bromide or SYBR Safe |

| Ethanol (95-100%) | Sample preservation and DNA precipitation | Critical for field collections; prevents DNA degradation [11] |

| Nanopore Flow Cells | Portable sequencing | R9.4.1 or newer chemistry for field barcoding; enables in situ sequencing [11] |

The selection of appropriate reagents directly impacts success rates, particularly for challenging samples such as historical museum specimens, environmental samples, or preservative-exposed tissues. For example, the CTAB (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) method is particularly effective for plant tissues high in polysaccharides and secondary metabolites that can inhibit PCR amplification [10].

Technological Innovations and Future Directions

Portable and Decentralized Technologies

Recent advances have democratized DNA barcoding through the development of portable, field-deployable technologies that enable in situ species identification:

Miniaturized Sequencing: Oxford Nanopore's MinION sequencer (smartphone-sized) permits real-time barcoding in remote locations, as demonstrated in the Peruvian Amazon where researchers generated 1,858 barcodes for vertebrates and plants entirely in situ [11]

Portable PCR Equipment: Battery-powered thermal cyclers and mini centrifuges facilitate complete molecular workflows outside traditional laboratories [11]

Citizen Science Integration: Simplified DNA barcoding protocols allow public participation in biodiversity monitoring, engaging community members in sample collection, DNA extraction, and PCR amplification [14]

These innovations are particularly valuable for reducing the geographic bias in genetic databases. Currently, the BOLD database contains only 0.52% of records from Peru despite its status as a megadiverse country, highlighting the need for decentralized sequencing capacity in biodiversity hotspots [11].

Bioinformatics and Data Integration

The growing volume of barcode data necessitates advanced computational approaches for effective analysis and interpretation:

Massive Parallel Barcoding (Megabarcoding): High-throughput approaches for soil macrofauna monitoring successfully identified 1,124 out of 1,283 previously unidentifiable individuals at competitive costs [12]

Morphological Profiling Integration: Automated image analysis and machine learning algorithms can correlate morphological features with molecular data, creating comprehensive bioactivity profiles for drug discovery applications [15]

Database Curation Improvements: Enhanced error detection algorithms and collaborative curation platforms address the high rates of misidentification (30% species-level, 26% generic errors) found in some reference databases [10]

The integration of DNA barcoding with other data streams creates powerful frameworks for biodiversity assessment and pharmaceutical discovery. For example, morphological profiling of small molecules generates bioactivity profiles that can be correlated with genetic barcodes of source organisms, enabling target prediction and mode-of-action analysis for novel compounds [15].

DNA barcoding represents a transformative methodology in species identification, offering significant advantages in accuracy, efficiency, and application range compared to traditional morphological approaches. The experimental data presented in this guide demonstrate that multi-locus barcoding strategies achieve superior discrimination rates (93.6% for Syringa) compared to single-marker approaches or morphological identification alone [9]. However, the most robust taxonomic frameworks emerge from integrative approaches that combine molecular data with morphological, ecological, and geographic information.

For research and drug development professionals, DNA barcoding provides an indispensable tool for quality control in natural product sourcing, identification of novel bioactive organisms, and monitoring of environmental impacts. The ongoing development of portable sequencing technologies and expanded reference databases will further enhance applications in field research and conservation. As the technology continues to evolve, DNA barcoding is poised to become an increasingly accessible and standardize method for species discrimination across diverse scientific disciplines.

The DNA barcoding gap represents a critical concept in molecular taxonomy, postulating that the genetic variation between species (interspecific) exceeds the variation within a species (intraspecific). This guide provides a comparative analysis of DNA barcoding performance against traditional morphological identification, focusing on applications in parasite research and drug development. We synthesize experimental data from diverse taxonomic groups, evaluate methodological protocols, and assess the reliability of barcoding gap application across different genetic markers and organismal types. The findings demonstrate that while barcoding offers substantial advantages for cryptic species identification and standardized diagnostics, its efficacy is contingent upon marker selection, taxonomic group, and reference database completeness.

Theoretical Foundation of the Barcoding Gap

The barcoding gap is formally defined as the separation between the distribution of intraspecific pairwise genetic distances and interspecific distances among related taxa using a standardized molecular marker [16] [17]. This concept provides the theoretical foundation for DNA-based species identification, proposing that a "gap" exists where genetic divergence between species exceeds variation within species, creating distinct boundaries for taxonomic classification [18].

The conceptual relationship between genetic distance and species delineation can be visualized as follows:

For optimal species discrimination, barcode markers must satisfy specific criteria: contain low intraspecific variation while maintaining high interspecific divergence, possess conserved flanking regions for universal primer design, and be short enough for practical amplification and sequencing [18]. Different taxonomic groups require specific molecular markers, as no single gene region works universally across all life forms:

- Animals: Cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) is the predominant marker [19] [17] [18]

- Plants: Combinations of matK, rbcL, trnH, and ITS regions [18]

- Fungi: Internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions, with noted variability between ITS1 and ITS2 [16]

- Parasitic Protozoa: Multi-locus approaches using metabolic network models [20]

The practical manifestation of the barcoding gap varies significantly across taxonomic groups. In spiders, COI barcodes effectively identified species across geographical scales regardless of morphological diagnosability [17]. Conversely, fungal studies revealed substantial variation in barcode gap size between ITS1 and ITS2 regions, with ITS2 demonstrating larger gaps due to lower intraspecific variance [16].

Performance Comparison: DNA Barcoding vs. Morphological Identification

Quantitative Comparison Across Taxonomic Groups

Table 1: Method Performance Across Organismal Groups

| Organism Group | Identification Method | Species Identified | Identification Rate | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nematodes | Morphological | 22 species | 100% (baseline) | Traditional microscopy | [21] |

| Nematodes | Single-specimen barcoding (28S) | 20 OTUs* | 90.9% | Comparable to morphology | [21] |

| Nematodes | Metabarcoding (28S) | 48 OTUs, 17 ASVs | Higher OTU count | Overestimation potential | [21] |

| Mosquitoes | Morphological | 45 species | 100% (baseline) | Gold standard | [19] |

| Mosquitoes | COI barcoding | 45 species | 100% | Perfect concordance | [19] |

| Forest Soil Macrofauna | Morphological | 130/1413 individuals | 9.2% | Limited expertise | [12] |

| Forest Soil Macrofauna | Megabarcoding | 1124 additional individuals | 79.5% | Massive improvement | [12] |

| Host-Parasitoid Systems | Morphological | Baseline | Varies | Cryptic species missed | [22] |

| Host-Parasitoid Systems | DNA barcoding | Higher diversity | >39.4% | Revealed cryptic diversity | [22] |

OTU: Operational Taxonomic Unit; *ASV: Amplicon Sequence Variant*

Methodological Advantages and Limitations

Table 2: Method Comparison for Parasite Research

| Parameter | Morphological Identification | DNA Barcoding | Metabarcoding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Species Resolution | Limited for cryptic species, larvae, damaged specimens [19] | High for most species, reveals cryptic diversity [22] | Variable, depends on reference database [21] |

| Expertise Requirement | High (taxonomic specialists) [21] | Moderate (molecular biology) | Bioinformatics intensive |

| Processing Time | Slow (individual handling) | Moderate (batch processing) | Fast (high-throughput) |

| Cost per Sample | Low (microscopy) | Moderate (reagents, sequencing) | Low for large batches |

| Quantification Ability | Good (direct counting) | Limited (presence/absence) | Biased (PCR amplification) [21] |

| Reference Database | Taxonomic keys, literature | BOLD, GenBank (growing) [18] | Specialized curated databases |

| Ideal Application | Well-characterized taxa, intact specimens | Cryptic species, larvae, damaged samples [19] | Biodiversity surveys, bulk samples [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Barcoding Gap Analysis

Standard DNA Barcoding Workflow

The general workflow for DNA barcoding analysis involves sequential steps from sample collection to data interpretation:

Key Methodological Considerations

Sample Collection and Preservation: Collection strategy depends on target organisms. For parasite studies, this may involve host dissection, fecal sampling, or environmental collection. Proper preservation is crucial to prevent DNA degradation – options include silica gel desiccation, ethanol preservation, or freezing at -80°C [18]. For mosquito identification studies, legs were removed carefully to preserve voucher specimens while obtaining sufficient DNA material [19].

DNA Extraction Protocols: The choice of extraction method significantly impacts DNA yield and quality. The cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method is particularly effective for plant and fungal material containing polysaccharides and polyphenols [23]. Commercial silica column-based kits provide consistent results for animal tissues. For processed materials or complex samples, pre-washing with Sorbitol Washing Buffer can improve DNA quality by removing PCR inhibitors [23].

Marker Amplification and Sequencing:

- COI for animals: Primers LCO1490 and HCO2198 amplify ~658 bp region [19] [18]

- ITS for fungi: ITS1-F and ITS4 primers target the full ITS region [16]

- Multi-locus for plants: Combinations of rbcL, matK, and ITS provide sufficient resolution [23] [18]

Thermocycling conditions typically involve initial denaturation (94-95°C for 2-5 minutes), 35-40 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 30-45s), annealing (45-55°C for 45-60s), and extension (72°C for 45-60s), with final extension (72°C for 5-10 minutes) [19].

Barcoding Gap Analysis: Genetic distances are calculated using models like Kimura-2-Parameter (K2P). Intra- and interspecific distances are compared through pairwise distance calculations. The barcode gap is visualized by plotting intraspecific distances against interspecific distances for each species [16] [17]. Statistical validation may involve randomization tests to confirm significant separation between distance distributions [17].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Barcoding Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits (DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit) | Nucleic acid purification | Consistent yield for animal tissues [19] |

| CTAB Extraction Buffer | Plant/fungal DNA isolation | Effective for polysaccharide-rich samples [23] |

| Proteinase K | Protein digestion | Enhances DNA release during extraction |

| Universal PCR Primers (LCO1490/HCO2198) | COI amplification | Standard for metazoan barcoding [19] |

| ITS Primers (ITS1-F/ITS4) | Fungal barcode amplification | Targets ITS region with broad taxonomic coverage [16] |

| PCR Master Mix | DNA amplification | Provides reaction components, magnesium optimization critical |

| Agarose Gels | Amplicon verification | Quality control pre-sequencing |

| Sanger Sequencing Reagents | DNA sequencing | Standard for single-specimen barcoding |

| NGS Library Prep Kits | Metabarcoding studies | Essential for high-throughput applications [21] [12] |

| Reference Databases (BOLD, GenBank) | Species identification | Taxonomic assignment of sequences [18] |

Discussion and Research Implications

The barcoding gap remains a powerful but nuanced concept in taxonomic research. Studies consistently demonstrate that DNA barcoding complements rather than replaces morphological identification, addressing specific limitations of traditional taxonomy while introducing new considerations for data interpretation.

In parasite research, molecular approaches enable identification of cryptic species and life stages that challenge morphological diagnosis. For protozoan parasites like Plasmodium, Toxoplasma, and Cryptosporidium, molecular tools facilitate comparative analyses across species boundaries, aiding drug target identification despite experimental challenges with unculturable species [20]. Metabolic network models (ParaDIGM) provide frameworks for comparing biochemical capabilities across parasite species, enhancing extrapolation from model organisms to clinically relevant pathogens [20].

The reliability of barcoding gap application varies taxonomically. Spider studies demonstrated effective species identification across geographical scales using COI barcodes [17], while fungal research revealed significant variation in barcode gap size between ITS1 and ITS2 regions, with implications for primer selection and taxonomic splitting practices [16]. These findings emphasize that a universal threshold for species delimitation remains elusive, necessitating taxon-specific validation.

Future methodological developments should focus on reference database expansion, standardization of multi-locus approaches for challenging taxa, and integration of morphological and molecular data within unified taxonomic frameworks. For drug development professionals and parasitologists, DNA barcoding offers robust species identification that strengthens epidemiological studies, therapeutic target validation, and biodiversity monitoring in changing ecosystems.

The accurate identification of parasites is a cornerstone of ecological, medical, and veterinary research. For decades, scientists relied primarily on morphological taxonomy, using microscopic examination of physical characteristics to distinguish species. However, this approach presents significant challenges, particularly for parasites like chironomid larvae, where high phenotypic plasticity, the existence of cryptic species, and the need for access to complete, identified individuals for comparison can make species-level identification difficult or even impossible [7]. This limitation can hinder the accurate assessment of biodiversity and the understanding of parasite life cycles.

The advent of DNA barcoding has provided a powerful alternative or complementary tool. This technique uses the sequence of a short, standardized genetic fragment as a unique identifier for a species. DNA barcoding not only allows for the identification of sister species but also facilitates the discovery of new, previously unknown ones [7]. To maximize accuracy and efficiency, the scientific community has converged on a suite of standard genetic markers for different kingdoms of life. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these standard markers—COI for animals, ITS for fungi, and chloroplast genes for plants—framed within the ongoing discussion of DNA barcoding versus traditional morphological identification.

Standardized Genetic Markers Across Kingdoms

The selection of a genetic marker for barcoding is based on several criteria: the presence of sufficiently conserved regions for primer design, interspecific variation (divergence between species) to distinguish them, and intraspecific conservation (similarity within a species) to group individuals correctly. The table below summarizes the key markers for animals, fungi, and plants.

Table 1: Standard DNA Barcode Markers for Major Organism Groups

| Organism Group | Primary Marker | Marker Full Name | Key Characteristics | Examples of Use in Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animals | COI | Cytochrome c Oxidase subunit I | A mitochondrial gene; provides strong species-level discrimination across most animal phyla. | The universal animal barcode; used in broad biodiversity surveys. |

| Fungi | ITS | Internal Transcribed Spacer | A non-coding region between ribosomal RNA genes; possesses a high degree of sequence variation. | Identification of phytopathogenic fungi; fungal metagenomics studies on fruits and vegetables [24]. |

| Plants | Chloroplast Genes | Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase large subunit (rbcL), Maturase K (matK) | Uniparentally inherited, structurally conserved genome with a combination of slow- and fast-evolving genes. | Core plant barcode; often used together for better resolution [25]. |

| Plants | Chloroplast Intergenic Spacers | trnH-psbA | A non-coding spacer region; often highly variable and useful for distinguishing closely related species. | Supplement to the core barcodes; provides higher resolution in specific genera [25]. |

The Hybrid Approach: Integrating Molecular and Morphological Data

While DNA barcoding is powerful, molecular techniques have limitations, including the lack of a complete barcode library for all taxa and the need for access to properly purified genetic material [7]. Consequently, the most robust methodological solution is a hybrid approach that integrates molecular data with elementary ecological knowledge and morphological identification. This synergy allows for the validation of molecular findings with physical evidence and helps interpret the ecological significance of the results, providing a fundamental tool for accurately assessing parasite communities and biodiversity [7].

Graphviz diagram illustrating the workflow for the integrated morphological and DNA barcoding identification method:

Workflow for Integrated Species Identification

Experimental Protocols and Data

Detailed Methodology for DNA Barcode Analysis

The following protocols are synthesized from standard methodologies used in recent genomic studies, particularly those involving plant chloroplast genomes and microbial sequencing [26] [25] [27].

Protocol 1: DNA Extraction, Sequencing, and Assembly for Chloroplast Genomes

Plant Material and DNA Extraction:

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Construct a shotgun library with an average insert size (e.g., 250-400 bp) following the manufacturer's guidelines [26] [25].

- Sequence the library on a next-generation sequencing (NGS) platform such as the Illumina Novaseq 6000 or X Ten Platform using a paired-end sequencing strategy (e.g., 150 bp reads) [26] [25].

Genome Assembly and Annotation:

- Trim raw reads for quality using tools like Skewer to remove low-quality bases and adapters [25].

- Assemble the chloroplast genome using a dedicated organelle assembler like GetOrganelle or by referencing a closely related species' genome [26] [25].

- Annotate the assembled genome using software such as CpGAVAS or Geneious Prime by aligning with a reference genome, manually adjusting start and stop codons [26] [25].

Protocol 2: Identification of Hypervariable Regions and Phylogenetic Analysis

Sequence Comparison and Divergence Hotspot Identification:

- Align multiple chloroplast genome sequences using MAFFT v7 [26].

- Analyze the aligned sequences for nucleotide variability using DnaSP software. Calculate Pi (nucleotide diversity) values using a sliding window approach (e.g., 200 bp step size, 800 bp window length) [26]. Genomic regions with high Pi values are considered hypervariable hotspots.

Phylogenetic Tree Construction:

- Compile a dataset of sequenced genomes, including outgroup species from related families [26].

- Select the best-fit nucleotide substitution model (e.g., K3Pu + F + R5) using ModelFinder [26].

- Construct a phylogenetic tree using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method in IQ-tree with ultrafast bootstrap (1000 replicates) to assess branch support [26].

Quantitative Comparison of Marker Performance

Data from comparative genomic studies allows for a quantitative assessment of the characteristics of different markers, particularly for plants.

Table 2: Experimental Data from Comparative Chloroplast Genome Studies

| Study Focus | Genome Size Range | Number of Genes Annotated | Identified Hypervariable Regions | Phylogenetic Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ficus (8 species) [26] | 160,333 bp (F. heteromorpha) to 160,772 bp (F. curtipes) | 127 unique genes (83 protein-coding, 8 rRNA, 36 tRNA) | 8 hypervariable regions (e.g., trnS-GCU_trnG-UCC, trnT-GGU_psbD, ndhF_trnL-UAG, ycf1) |

Clarified relationships within subgenera; suggested merger of two subgenera. |

| Polygonum (4 species) [25] | 159,015 bp to 163,461 bp | 112 genes (78 protein-coding, 30 tRNA, 4 rRNA) | High variation in non-coding regions; IR region changes key for evolution. | Resolved phylogenetic tree; confirmed placement of one species in Fallopia genus. |

| Styrax (5 species) [27] | 157,817 bp to 158,015 bp | 132 genes (87 protein-coding, 37 tRNA, 8 rRNA) | Specific mutation hotspot regions involving IR expansion/contraction. | Revealed conflicts between trees from coding vs. complete genomes. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful DNA barcoding and genomic analysis rely on a suite of specific reagents, kits, and bioinformatics tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Genetic Marker Studies

| Item | Function | Specific Example / Target |

|---|---|---|

| CTAB Buffer | DNA extraction from plant and fungal tissues; effective against polysaccharides and polyphenols. | Standard protocol for chloroplast genome studies [26] [25]. |

| Illumina Sequencing Platform | High-throughput sequencing to generate raw genomic data. | Novaseq 6000, X Ten Platform [26] [25]. |

| GetOrganelle / SOAPdenovo2 | Software for de novo assembly of organelle genomes from NGS data. | Used for assembling chloroplast genomes of Ficus and Polygonum [26] [25]. |

| MAFFT | Software for multiple sequence alignment of genomic data. | Aligning complete chloroplast genomes for comparison [26]. |

| MISA | Software for identifying Simple Sequence Repeats (SSRs/microsatellites). | SSR analysis in Ficus and Styrax chloroplast genomes [26] [27]. |

| IQ-tree | Software for constructing maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees. | Phylogenetic analysis of Ficus with bootstrap support [26]. |

| Specific PCR Primers | Amplifying target barcode regions (e.g., ITS, rbcL, matK, COI). | ITS for fungal identification; chloroplast gene primers for plants [24]. |

The debate between DNA barcoding and morphological identification is most productively resolved through integration. While morphological taxonomy provides essential ecological context and visual validation, DNA barcoding offers a powerful, objective tool for distinguishing cryptic species and processing large numbers of samples. The standard markers—COI for animals, ITS for fungi, and a combination of chloroplast genes like rbcL and matK for plants—each provide a robust foundation for this molecular identification. As sequencing technologies continue to advance and reference libraries expand, this hybrid approach will become increasingly indispensable for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working in parasitology, biodiversity, and beyond.

For researchers in parasitology, ecology, and drug development, accurate species identification is foundational to scientific progress. The traditional method of morphological identification, while essential, faces significant challenges including the need for specialized taxonomic expertise, the existence of cryptic species complexes, and the difficulty in identifying immature life stages. DNA barcoding has emerged as a powerful complementary tool, using short, standardized gene regions to facilitate species identification and discovery. The mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) gene serves as the primary barcode for animals, while other markers like ITS are used for fungi and a combination of plastid regions for plants [28] [29]. Two platforms form the core infrastructure for this molecular approach: The Barcode of Life Data System (BOLD) and GenBank. While both serve as massive repositories of genetic data, their architectures, curation processes, and identification performance differ substantially. Understanding these differences is crucial for researchers choosing the appropriate tool for specific applications, particularly in the context of parasite identification which informs drug and vaccine development [30].

System Architectures and Core Functions

BOLD and GenBank, while both genetic databases, were built with fundamentally different philosophies and operational goals, reflected in their data structures and curation standards.

The Barcode of Life Data System (BOLD)

BOLD is a specialized workbench and data repository specifically designed for the DNA barcoding community. Its architecture is built around the core concept of a barcode record, which persistently links a DNA sequence to its source specimen [31]. A record gains formal "BARCODE" designation only after meeting seven specific data standards, including species name, voucher specimen details with depository institution, collection record with geospatial coordinates, collector information, a COI sequence of at least 500 bp, PCR primer information, and associated trace files [31]. This rigorous linkage ensures data integrity and facilitates verification.

BOLD employs automated quality checks, including translation of COI sequences into amino acids to verify they derive from the correct gene and not nuclear pseudogenes, and screening for contaminants [31]. A key analytical feature of BOLD is the Barcode Index Number (BIN) system, which clusters sequences into molecular operational taxonomic units (mOTUs) using private algorithms, providing a registry for all animal species that often corresponds closely with known species [28]. The platform also provides a dedicated Identification Engine that compares query sequences against its curated library.

GenBank

GenBank, managed by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), is a comprehensive, open-access sequence database that forms part of the International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration (INSDC), which also includes the DNA DataBank of Japan (DDBJ) and the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) [32]. Its mission is to be an all-inclusive repository for all publicly available DNA sequences, supporting a vast range of biological research beyond taxonomy, including genomics, molecular biology, and drug development [30] [32].

As a foundational bioinformatics resource, GenBank imposes minimal formatting requirements, leading to a more flexible but less standardized data structure compared to BOLD. Its primary tool for sequence-based identification is the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST), which finds regions of local similarity between a query sequence and sequences in the database [32]. While extremely powerful, BLAST is a general-purpose homology search tool not exclusively optimized for species identification. The data in GenBank is subject to quality assurance checks for issues like vector contamination and correct taxonomy, but the system operates on a "self-policing" model where the community is expected to report and correct errors [30]. Notably, GenBank allows authors to request a hold on data release until publication to prevent scooping [32].

Table 1: Fundamental Architectural Differences Between BOLD and GenBank.

| Feature | BOLD Systems | GenBank |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mission | Specialized workbench for DNA barcoding; species identification and discovery [31] | Comprehensive, public nucleotide sequence archive for all biological research [32] |

| Core Data Unit | Specimen-vouchered barcode record with required collateral data [31] | Sequence record with associated annotation and bibliography [32] |

| Data Standards | Strict, seven-element standard for "BARCODE" designation [31] | Flexible formatting to accommodate diverse data types [32] |

| Identification Engine | Dedicated BOLD Identification Engine | Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) [32] |

| Curation Model | Automated quality checks (COI translation, contamination); project-based data ownership [31] | Centralized quality checks; community-driven error correction [30] |

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data and Analysis

Independent studies have systematically evaluated the identification accuracy of BOLD and GenBank across various taxa, providing crucial empirical data for researchers.

Large-Scale Insect Identification Accuracy

A 2023 study analyzing 1,160 COI sequences from eight insect orders in Colombia provides a direct performance comparison. The research assessed accuracy at the family, genus, and species levels by comparing the engine suggestions with taxonomic identifications made by specialists. The results are summarized in Table 2 below [33].

Table 2: Identification Accuracy of BOLD and GenBank for Insect Orders [33].

| Taxonomic Level | Overall Performance | Order-Specific Outperformer |

|---|---|---|

| Family Level | BOLD outperformed GenBank [33] | Coleoptera (BOLD higher) [33] |

| Genus Level | BOLD outperformed GenBank [33] | Coleoptera & Lepidoptera (BOLD higher); Other orders performed similarly [33] |

| Species Level | BOLD outperformed GenBank [33] | Coleoptera & Lepidoptera (BOLD higher); Other orders performed similarly [33] |

| Key Finding | For a subset of Scarabaeinae (Coleoptera), BOLD correctly identified species only when the match percentage was above 93.4% [33] |

The study concluded that BOLD exhibited "great potential" to accurately place insects into taxonomic categories and highlighted its reliability "in the absence of a large reference database for a highly diverse country" [33].

Despite the overall strong performance, DNA barcoding is not infallible. A systematic evaluation of 68,089 Hemiptera barcode sequences found that errors in public repositories "are not rare," with most being human errors such as specimen misidentification, sample confusion, and contamination [29]. A significant portion of these errors can be traced back to inappropriate practices in the DNA barcoding workflow, underscoring the need for rigorous protocols [29]. This affects both BOLD and GenBank, as data is often shared between them.

Another study on pygmy hoppers (Tetrigidae) revealed specific database limitations, noting that many records lack photographic vouchers and that the "taxonomic backbone of BOLD is out of date" [34]. This can lead to misidentifications being propagated through the system. Furthermore, while the BIN system is valuable for clustering, its algorithm is not public and the clusters can be unstable when new data is added, sometimes conflicting with clusters generated by other algorithms like ABGD and ASAP [34].

Diagram 1: Comparative workflow for species identification using BOLD and GenBank, highlighting key differences in quality control and analysis that contribute to varying identification accuracy.

Practical Applications and Research Toolkit

The choice between BOLD and GenBank, or the decision to use both, depends heavily on the specific research objectives, whether for biodiversity surveys, pathogen vector monitoring, or discovering novel bioactive compounds from organisms.

Case Studies in Applied Research

- Mosquito Surveillance: A 2024 study comparing multiplex PCR and DNA barcoding for identifying container-breeding Aedes species found that a tailored multiplex PCR protocol outperformed COI barcoding in ovitrap samples, correctly identifying 1990 out of 2271 samples compared to 1722 for barcoding [35]. Crucially, the multiplex PCR detected species mixtures in 47 samples, which Sanger sequencing-based barcoding missed. This demonstrates that while barcoding is powerful, purpose-built molecular assays can be more effective for targeted surveillance of known parasite vectors [35].

- Medicinal Plant Identification: Research on Syringa species, which contain pharmacologically active compounds, evaluated multiple DNA barcodes to combat market adulteration. The study found that a combination of three markers (ITS2 + psbA-trnH + trnL-trnF) achieved a 98.97% identification rate via BLAST, underscoring GenBank's utility for authenticating medicinal plant materials [9].

- Cryptic Diversity Discovery: Studies on insects consistently reveal that DNA barcoding can uncover cryptic species—morphologically similar but genetically distinct organisms [33] [29]. This is critical in parasitology, where cryptic species may differ in host specificity, pathogenicity, or drug susceptibility, directly impacting disease management and drug development strategies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting DNA barcoding studies, based on methodologies cited in the research.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for DNA Barcoding Workflows.

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| COI Primers (e.g., LCO1490/HCO2198) | Amplify the ~658 bp "barcode region" of the cytochrome c oxidase I gene via PCR [33]. | Standard barcoding for animal species, including insects and parasites [33]. |

| Alternative Genetic Markers (e.g., ITS2, psbA-trnH) | Used for barcoding non-animal taxa (ITS2 for Fungi; plastid markers for plants) [28] [9]. | Identifying fungal pathogens or medicinal plants [9] [28]. |

| High-Throughput DNA Isolation Kit | Efficient nucleic acid extraction from diverse specimen types, including tissues and whole small organisms [33]. | Processing large numbers of samples in biodiversity surveys [33]. |

| Taq DNA Polymerase & PCR Master Mix | Enzymatic amplification of the target barcode region from extracted DNA [33]. | A core step in all DNA barcoding protocols [33] [35]. |

| Sanger Sequencing Reagents | Determine the nucleotide sequence of the amplified PCR product. | Generating the barcode sequence for submission and analysis [35]. |

| Reference Database Access (BOLD, GenBank) | Platforms for sequence comparison, identification, and data storage. | The final step for identifying an unknown specimen via its barcode [33] [32]. |

Both BOLD and GenBank are indispensable tools in the modern biologist's arsenal, yet they serve complementary roles. BOLD, with its stricter data standards, specimen-centric model, and specialized identification engine, is generally more reliable and accurate for taxonomic identification, particularly in animals [33]. GenBank's strength lies in its comprehensive, all-inclusive nature and powerful BLAST tool, making it an unparalleled resource for broader genomic and bioinformatics research, including drug target identification [30].

For researchers focused on parasite identification, the choice is context-dependent. A taxonomist conducting a biodiversity survey of potential disease vectors would benefit from BOLD's curated structure and higher accuracy. A drug development researcher hunting for homologs of a potential target gene discovered in a parasite would rely on GenBank's vast genomic data. Ultimately, an integrative approach that combines morphological expertise with data from both molecular platforms, while being critically aware of the potential for errors in both, represents the most robust strategy for scientific discovery and its application in public health and medicine.

From Theory to Bench: Protocols and Cutting-Edge Applications in Biomedicine

The accurate identification of parasites and other organisms is a cornerstone of biological research, drug development, and diagnostic applications. For centuries, morphological identification was the primary method, relying on the visual assessment of physical characteristics under a microscope. While this method is still used, it requires highly specialized taxonomic expertise and often proves inadequate for damaged specimens, early life stages, or cryptic species complexes [6]. In contrast, DNA barcoding utilizes short, standardized genetic markers from an organism's genome to enable precise species identification, overcoming many of the limitations inherent in morphological approaches [36] [37].

The fundamental advantage of DNA barcoding lies in its standardization and reproducibility. Where morphological identification can be subjective—with studies showing consistency among taxonomists as low as 13.5% at the species level for larval fish—DNA barcoding provides an objective, data-driven metric for classification [6]. This is particularly critical in parasitology, where accurate identification directly impacts disease diagnosis, treatment strategies, and drug development efforts. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these methodologies, with a detailed, step-by-step workflow for implementing DNA barcoding in a research setting.

Performance Comparison: DNA Barcoding vs. Morphological Identification

Direct experimental comparisons reveal clear operational and performance differences between these two identification strategies.

Table 1: Experimental Performance Comparison in Species Identification

| Parameter | DNA Barcoding | Morphological Identification |

|---|---|---|

| Species-Level Accuracy | 76.9% concordance (with discrepancies due to recently diverged species) [6] | 76.9% concordance (limited for cryptic species) [6] |

| Genus-Level Accuracy | 96.6% concordance [6] | 96.6% concordance [6] |

| Damaged Specimen ID | Successful in 35 out of 37 damaged larval fish [6] | Impossible for 37 out of 37 damaged larval fish [6] |

| Embryo Identification | Successfully identified 103 embryos [6] | Unable to identify embryos due to lack of morphological features [6] |

| Technical Consistency | High objectivity; results are reproducible across labs [6] | Low objectivity; ~13.5% consistency among experts at species level [6] |

| Resolution in Problematic Genera | Limited for recently diverged groups (e.g., Coregonus) [6] | Limited for morphologically similar groups (e.g., Catostomus) [6] |

| Cost & Efficiency | More cost-effective and efficient for large-scale monitoring [6] | Less cost-effective, requires highly trained taxonomists [6] |

The data show that while both methods can achieve high taxonomic-level accuracy, DNA barcoding provides decisive advantages for non-ideal samples like embryos, larvae, or damaged specimens. Morphological identification remains a valuable tool but suffers from subjectivity and limitations when key physical characteristics are absent.

DNA Barcoding Workflow: A Step-by-Step Guide

The implementation of DNA barcoding follows a multi-stage process, from sample collection to sequence analysis. The workflow below illustrates the key steps, with detailed protocols and considerations for researchers.

Step 1: Sample Collection and Nucleic Acid Extraction

The first critical step is obtaining high-quality genetic material from the biological sample.

- Sample Collection: Samples can include tissue biopsies, whole small parasites, blood, cultured cells, or environmental samples. Fresh material is always preferred, but archived samples (e.g., FFPE tissue) can also be used, albeit with lower DNA yield and quality [38].

- Cell Lysis: The cellular structure is disrupted to create a lysate. This can be achieved through:

- Physical Methods: Grinding with a mortar and pestle (often under liquid nitrogen), bead beating, or sonication. These are essential for structured materials like tissues or plant/parasite cell walls [39].

- Chemical Methods: Using detergents (e.g., SDS) and chaotropic salts (e.g., guanidine hydrochloride) to disrupt cell membranes and denature proteins [39].

- Enzymatic Methods: Applying enzymes like proteinase K to digest proteins and lysozyme to break down bacterial cell walls [39].

- Nucleic Acid Purification: The DNA is separated from other cellular components. Silica-based purification is the most common methodology. It relies on the fact that DNA binds to silica in the presence of high-salt chaotropic conditions, allowing contaminants to be washed away before the pure DNA is eluted in a low-salt buffer [39]. The success of extraction is gauged by assessing DNA yield (quantity), purity (A260/A280 ratio ~1.8), and integrity (high molecular weight and lack of degradation) [40].

Step 2: Library Preparation for Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

This step fragments the purified DNA and adds platform-specific oligonucleotide adapters to make it "sequenceable."

- DNA Fragmentation: The long, extracted DNA is broken into short fragments of a defined size (typically 200-600 bp). This can be done enzymatically or via acoustic shearing [40] [38].

- Adapter Ligation: Short, synthetic DNA sequences, called adapters, are ligated to the ends of the DNA fragments. These adapters are complementary to the oligonucleotides on the sequencing flow cell and contain molecular barcodes (indices) that allow multiple samples to be pooled and sequenced together in a single run—a process known as multiplexing [40] [38].

- Library Quantification and Normalization: The final prepared library is quantified using methods like fluorometry or qPCR to ensure an optimal concentration of DNA fragments is loaded onto the sequencer, which is critical for generating high-quality data [40].

Step 3: Clonal Amplification and Sequencing

The prepared library is loaded onto an NGS platform for the sequencing reaction itself.

- Clonal Amplification: Individual DNA fragments from the library are amplified locally on the flow cell to create clusters of identical copies through a process called bridge amplification [40]. This amplification is necessary because the fluorescence from a single DNA molecule is too weak to be detected.

- Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS): The Illumina platform, the most common for DNA barcoding applications, uses SBS chemistry with fluorescently labeled, reversibly terminated nucleotides. In each cycle, a single complementary base is incorporated into the growing DNA strand, its fluorescence is imaged, and the terminator is cleaved to allow the next cycle to begin. This process is repeated for a predetermined number of cycles (e.g., 150-300) to determine the base sequence of each cluster [40] [41].

Step 4: Bioinformatic Data Analysis

The final step converts raw sequencing data into a species identification.

- Base Calling and Demultiplexing: The instrument's software translates the fluorescence images into nucleotide sequences (FASTQ files). Samples are then separated (demultiplexed) based on their unique barcodes [40].

- Processing and Analysis: This involves several sub-steps:

- Quality Filtering: Removing low-quality sequences and adapter sequences [40].

- Sequence Alignment: Assembling the short reads into a contiguous sequence or aligning them to a reference database [40].

- Variant Calling: Identifying nucleotide differences between the sample sequence and reference sequences.

- Interpretation and Identification: The final, high-quality DNA barcode sequence (e.g., the COI gene for animals) is queried against a reference database such as the International Barcode of Life (iBOL) to assign a species identity [36] [37].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of the DNA barcoding workflow depends on a suite of specialized reagents and kits.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Kits for DNA Barcoding Workflow

| Reagent / Kit Type | Primary Function | Examples & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolate DNA from various sample types. | Silica-membrane columns (e.g., Promega, Thermo Fisher); choice depends on sample type (tissue, blood, FFPE) [42] [39]. |

| DNA Polymerases | Amplify target barcode regions via PCR. | High-fidelity polymerases are critical to minimize errors during amplification prior to sequencing [40]. |

| Library Preparation Kits | Fragment DNA and attach sequencing adapters. | Illumina DNA Prep kits; include enzymes for fragmentation, end-repair, A-tailing, and ligation [40]. |

| Sequence Adapters & Barcodes | Unique identification of multiplexed samples. | Illumina CD Indexes; dual indexing is recommended to index both ends of a fragment, reducing sample cross-talk [40] [38]. |

| Quality Control Assays | Assess DNA and library quantity/quality. | Fluorometric assays (Qubit dsDNA HS Assay) for accurate quantification; gel electrophoresis for size confirmation [40]. |

The comparative data and detailed workflow presented in this guide demonstrate that DNA barcoding offers a powerful, standardized, and highly reliable alternative to traditional morphological identification. Its ability to identify damaged specimens, early developmental stages, and resolve taxonomically challenging groups makes it an indispensable tool for modern researchers and drug development professionals. While morphology retains its value for initial specimen sorting and field studies, the integration of DNA barcoding into research pipelines ensures a higher degree of accuracy, reproducibility, and efficiency, ultimately accelerating scientific discovery and diagnostic precision.

The accurate identification of parasites is a cornerstone of medical diagnostics, epidemiological surveillance, and biological research. For centuries, scientific discovery has relied on morphological taxonomy, which identifies species based on physical characteristics observable under a microscope. While this method provides the foundational classification for most known parasites, it faces significant limitations, including the inability to identify larvae, damaged specimens, or cryptic species complexes that are morphologically identical but genetically distinct [43] [7]. The advent of molecular biology has introduced DNA barcoding as a powerful, complementary tool. This technique uses a short, standardized gene sequence from a specific region of an organism's genome as a molecular "barcode" for species identification and discovery [44] [22].