DINOv2-Large for Parasite Classification: A Self-Supervised Breakthrough in Biomedical AI

This article explores the transformative application of Meta AI's DINOv2-large, a self-supervised vision transformer model, for the automated classification of intestinal parasites.

DINOv2-Large for Parasite Classification: A Self-Supervised Breakthrough in Biomedical AI

Abstract

This article explores the transformative application of Meta AI's DINOv2-large, a self-supervised vision transformer model, for the automated classification of intestinal parasites. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive analysis spanning from foundational concepts to real-world validation. We detail the model's mechanism, which eliminates dependency on vast labeled datasets, and present a methodological guide for implementation in stool sample analysis. The content further addresses common optimization challenges, validates performance against state-of-the-art models and human experts, and concludes with the profound implications for enhancing diagnostic accuracy, streamlining global health interventions, and accelerating biomedical research.

Understanding DINOv2-Large: A Self-Supervised Revolution for Biomedical Imaging

Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) and its Advantage over Supervised Methods in Medical Domains

Self-supervised learning (SSL) is a machine learning paradigm that learns meaningful feature representations from unlabeled data by generating its own supervisory signals, eliminating complete reliance on manually annotated datasets [1]. This approach creates pretext tasks—such as predicting missing parts of an image or determining the relative position of image patches—forcing the model to learn underlying data patterns and structures without human-provided labels [2]. The knowledge acquired from these pretext tasks is subsequently transferred to downstream tasks (e.g., classification or detection) through fine-tuning, often with minimal labeled data [2] [3].

SSL is particularly transformative for medical domains, where acquiring large-scale, expertly annotated datasets is a fundamental challenge due to the cost, time, and specialized expertise required for labeling [4] [5]. By leveraging abundant unlabeled data, SSL reduces this annotation bottleneck and demonstrates strong potential for improving model generalization and performance in specialized applications [6] [1].

SSL Advantages in Medical Domains: Evidence from Comparative Studies

Key Advantages of SSL

- Reduced Reliance on Labeled Data: SSL minimizes the need for costly and time-consuming manual annotation by leveraging the inherent structure of unlabeled data for pre-training [4] [1]. This is crucial in medical fields where expert annotation is a scarce resource [5].

- Improved Generalization and Robust Features: SSL encourages models to learn general, transferable features rather than overfitting to narrow task-specific labels, often leading to better performance on diverse datasets and tasks [6] [7].

- Flexibility Across Domains and Data Types: The same SSL principles can be applied to images, text, audio, or graph data with minimal adjustments, making it a versatile tool for various medical data modalities [6] [1].

Case Study: Superior Performance in Parasite Classification

Recent research on intestinal parasite identification demonstrates SSL's advantage. The study evaluated multiple models, including the SSL-based DINOv2 and supervised models like ResNet-50 and YOLOv8-m. DINOv2-large achieved state-of-the-art performance, surpassing its supervised counterparts [8] [9] [10].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Deep Learning Models in Intestinal Parasite Identification

| Model | Learning Paradigm | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | F1 Score (%) | AUROC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DINOv2-large | Self-supervised | 98.93 | 84.52 | 78.00 | 99.57 | 81.13 | 0.97 |

| YOLOv8-m | Supervised | 97.59 | 62.02 | 46.78 | 99.13 | 53.33 | 0.755 |

| ResNet-50 | Supervised | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported |

The results show DINOv2-large substantially outperforms YOLOv8-m in precision, sensitivity, and F1 score, indicating its superior ability to correctly identify parasites with fewer false positives and false negatives [9]. The high AUROC (0.97) further confirms its strong discriminatory power [8] [10].

Performance in Low-Data and Imbalanced Regimes

While SSL excels with large unlabeled datasets, its performance in low-data or imbalanced scenarios is nuanced. One comprehensive study comparing SSL and supervised learning on small, imbalanced medical imaging datasets found that in most experiments with small training sets, supervised learning outperformed selected SSL paradigms, even with limited labeled data [4].

However, other research suggests SSL representations can be more robust to class imbalance than supervised learning. One analysis concluded that the performance gap between models pre-trained on balanced versus imbalanced datasets was notably smaller for SSL compared to supervised learning, indicating greater robustness to dataset imbalance [4].

Table 2: SSL vs. Supervised Learning on Small Medical Imaging Datasets

| Experiment Context | Key Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Small training sets (e.g., 771-1,214 images) | SL often outperformed SSL | Careful paradigm selection needed for small data |

| Class-imbalanced pre-training | SSL performance declines but may still surpass SL | SSL shows greater robustness to imbalance |

| Domain-specific downstream tasks | In-domain low-data SSL pretraining can outperform large-scale general pretraining | Data relevance can compensate for quantity |

For domain-specific applications, in-domain low-data SSL pretraining can outperform large-scale pretraining on general datasets (e.g., ImageNet), highlighting the importance of data relevance [3].

Experimental Protocol: SSL Framework for Medical Image Classification

SSL Pre-training with DINOv2

Principle: The DINOv2 framework employs self-distillation with no labels, where a student network learns to match the output of a teacher network on different views of the same image. The teacher network is built from the student using an exponential moving average (EMA) [7].

DINOv2 Self-Distillation Training

Procedure:

- Input Preparation: Generate multiple different views (crops) of each input image through data augmentation. Create both global views (lower resolution, e.g., 224×224) and local views (smaller crops, e.g., 96×96) [7].

- Network Setup: Initialize identical Vision Transformer (ViT) architectures for both teacher and student networks.

- Forward Pass:

- Pass global views through the teacher network

- Pass local views through the student network

- Loss Calculation: Compute cross-entropy loss between the student's output (from local views) and teacher's output (from global views).

- Parameter Update:

- Update student network parameters via gradient descent

- Update teacher network parameters as exponential moving average (EMA) of student parameters

Technical Enhancements in DINOv2:

- Patch-Level Objective: Incorporates masked image modeling (MIM) where random patches to the student are masked [7].

- Sinkhorn-Knopp Centering: Replaces standard softmax centering with an online Sinkhorn-Knopp batch normalization technique for more stable training [7].

- KoLeo Regularizer: Promotes uniformly distributed embeddings to prevent dimensional collapse [7].

Downstream Task Fine-tuning for Parasite Classification

Principle: Leverage features learned during SSL pre-training for specific medical classification tasks with minimal labeled data.

Downstream Task Fine-tuning

Procedure:

- Feature Extraction:

- Use pre-trained DINOv2 backbone with frozen parameters

- Process labeled stool sample images through the network

- Extract feature vectors from the final layer

- Classifier Training:

- Initialize a linear classification head on top of frozen features

- Train only the linear layer using labeled parasite data

- Use standard cross-entropy loss and Adam optimizer

- End-to-End Fine-tuning (Optional):

- For optimal performance, unfreeze the entire network after initial linear training

- Fine-tune all parameters with a very low learning rate (e.g., 1e-6)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Computational Resources for SSL in Medical Imaging

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in SSL Research |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow, LightlyTrain | Provide SSL method implementations and training pipelines |

| SSL Model Architectures | DINOv2, SimCLR, BYOL, MoCo | Offer pre-trained models and reference implementations for transfer learning |

| Medical Imaging Datasets | LVD-142M, Institutional stool sample databases | Supply unlabeled data for pre-training and labeled data for fine-tuning |

| Data Augmentation Libraries | Torchvision, Albumentations, Imgaug | Generate diverse views for contrastive learning and prevent overfitting |

| Vision Transformer Models | ViT-S (Small), ViT-B (Base), ViT-L (Large) | Serve as backbone architectures for feature extraction |

| Evaluation Metrics | Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, AUROC | Quantify model performance for classification tasks |

Self-supervised learning, particularly through advanced frameworks like DINOv2, offers significant advantages over traditional supervised methods in medical domains. By reducing dependence on scarce labeled data while learning robust, transferable features, SSL enables more scalable and effective deep learning solutions for healthcare applications. The demonstrated success in parasite classification, with DINOv2-large achieving 98.93% accuracy and 0.97 AUROC, underscores SSL's potential to transform medical image analysis. As SSL methodologies continue to evolve, they promise to further bridge the gap between limited medical annotations and the data-hungry nature of deep learning, accelerating innovation across diverse healthcare domains.

DINOv2 (self-DIstillation with No labels) represents a significant advancement in self-supervised learning for computer vision, developed by Meta AI to generate robust, general-purpose visual features without requiring fine-tuning [7] [11]. This model functions as a visual foundation model capable of producing universal features applicable to diverse vision tasks including image classification, segmentation, depth estimation, and instance retrieval [7]. For research in parasite classification, DINOv2 offers a powerful backbone that can understand complex morphological features of parasites without the need for extensive labeled datasets, which are often scarce in medical diagnostics [9]. The architecture leverages a student-teacher framework within a Vision Transformer (ViT) backbone, enabling learning from uncurated images through self-supervision—a particularly valuable characteristic for medical imaging applications where manual annotation is costly and time-consuming [12].

Core Architectural Components

Vision Transformer Backbone

DINOv2 utilizes various sizes of Vision Transformers (ViT) including ViT-S/14, ViT-B/14, ViT-L/14, and ViT-g/14, with the largest model containing approximately 1 billion parameters [11]. The ViT architecture processes images by dividing them into fixed-size non-overlapping patches (typically 14×14 pixels), which are linearly embedded and processed through deep stacks of self-attention layers [11]. This patch-based processing enables the model to capture both local and global image contexts, essential for recognizing intricate parasite structures and morphological variations. Key architectural advancements in DINOv2 include untied projection heads for image-level and patch-level losses, SwiGLU feed-forward layers in from-scratch models, and efficient attention mechanisms through FlashAttention implementation [11]. The model also employs aggressive stochastic depth (up to 40% drop rates) to facilitate stable training of deep transformer architectures [11].

Student-Teacher Mechanism

The student-teacher framework forms the core of DINOv2's self-supervised learning approach, employing a dynamic knowledge distillation process where both networks share identical architectural designs but differ in parameter updates [7] [13]. In this framework, the student model (with learnable parameters) is trained to match the output distributions of a teacher model whose parameters are an exponential moving average (EMA) of past student iterations [7] [13]. This mechanism operates through two parallel augmented views of the same input image: the student network processes randomly masked patches while the teacher network processes visible tokens without masking [7]. The training employs a composite loss function combining cross-entropy losses for both image-level and patch-level predictions, enabling the model to learn robust representations invariant to various transformations [7].

Table: DINOv2 Model Variants and Specifications

| Model Variant | Patch Size | Feature Dimension | Parameters | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ViT-S/14 | 14×14 | 384 | 21M | Resource-constrained environments |

| ViT-B/14 | 14×14 | 768 | 85M | Standard classification tasks |

| ViT-L/14 | 14×14 | 1024 | 300M | Complex segmentation tasks |

| ViT-g/14 | 14×14 | 1536 | 1.1B | State-of-the-art performance |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Feature Extraction for Parasite Classification

This protocol outlines the methodology for extracting features from stool sample images using DINOv2's frozen backbone, adapted from successful implementations in parasite identification research [9].

Materials and Reagents:

- Stool sample slides prepared using Formalin-Ethyl Acetate Centrifugation Technique (FECT) or Merthiolate-Iodine-Formalin (MIF) staining [9]

- Microscope with digital imaging capabilities (≥20x magnification)

- Computing system with NVIDIA GPU (≥8GB VRAM) and PyTorch framework

Procedure:

- Image Acquisition: Capture digital micrographs of stained stool samples at consistent magnification (recommended: 40x). Ensure each image contains at least one identifiable parasite structure.

- Preprocessing: Resize images to 518×518 pixels to match DINOv2's training resolution. Apply normalization with mean=0.5 and std=0.2 across RGB channels [14].

- Feature Extraction: Utilize a pre-trained DINOv2 model (recommended: DINOv2-large for optimal performance) to extract features without fine-tuning:

- Classification: Train a linear classifier (logistic regression or SVM) on the extracted features for parasite species identification.

Validation: In recent studies, this approach achieved 98.93% accuracy, 84.52% precision, 78.00% sensitivity, and 99.57% specificity for intestinal parasite identification using DINOv2-large [9].

Protocol 2: Few-Shot Learning for Rare Parasites

This protocol enables effective model adaptation with limited labeled examples of rare parasite species, leveraging DINOv2's robust feature representations.

Procedure:

- Support Set Curation: Gather a minimal dataset (5-20 samples per class) of rare parasite species, ensuring morphological diversity in the samples.

- Feature Embedding Extraction: Follow Protocol 1 to extract features from both the support set (rare species) and a larger base dataset (common species).

- Similarity-based Classification: Implement a k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) classifier in the feature space using cosine similarity as the distance metric:

- Evaluation: Assess performance using leave-one-out cross-validation on the support set.

Performance Expectations: DINOv2 has demonstrated strong few-shot learning capabilities, with studies showing it can match or exceed supervised baselines when using only 1-10% of available training data [12].

Table: DINOv2 Performance in Parasite Identification (Adapted from Corpuz et al., 5)

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Sensitivity | Specificity | F1 Score | AUROC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DINOv2-large | 98.93% | 84.52% | 78.00% | 99.57% | 81.13% | 0.97 |

| DINOv2-base | 97.82% | 79.15% | 72.34% | 98.92% | 75.61% | 0.94 |

| DINOv2-small | 96.45% | 75.28% | 68.91% | 98.15% | 71.95% | 0.91 |

| YOLOv8-m | 97.59% | 62.02% | 46.78% | 99.13% | 53.33% | 0.76 |

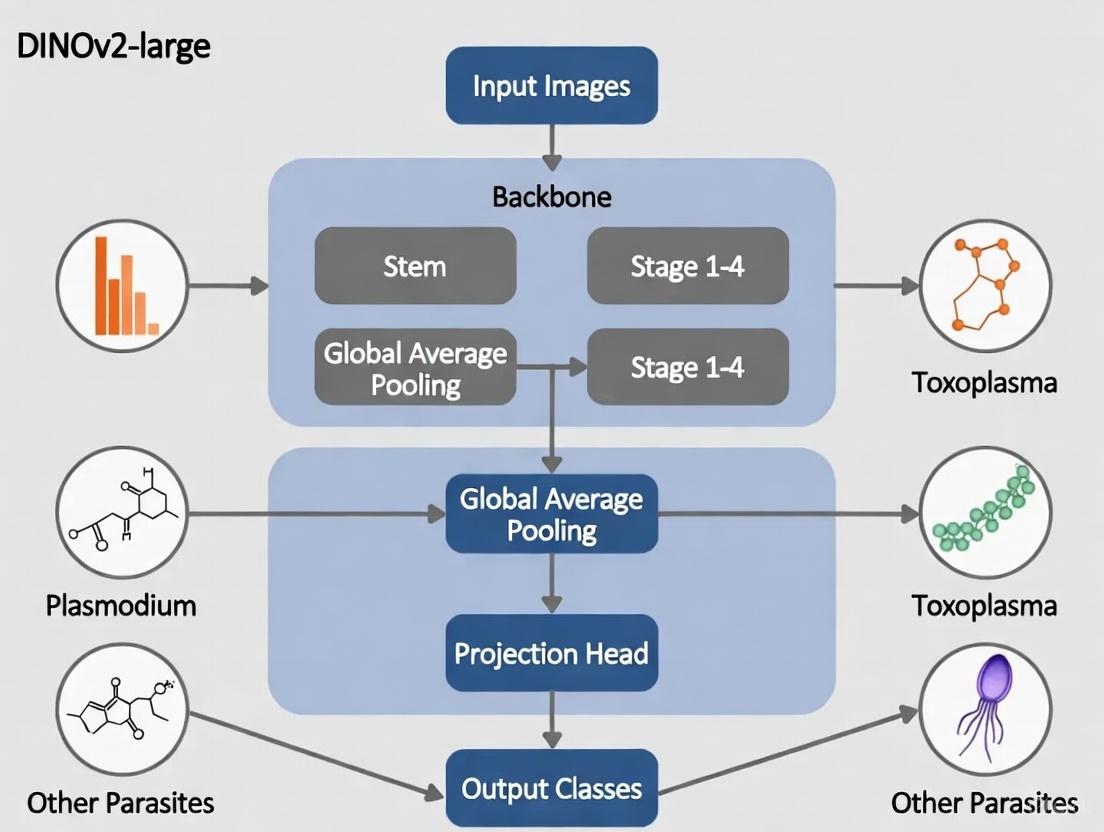

Architectural Workflow Visualization

Student-Teacher Training Mechanism

Patch Processing in Vision Transformer

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for DINOv2-based Parasite Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained DINOv2 Models | Provides foundation features without training from scratch | torch.hub.load('facebookresearch/dinov2', 'dinov2_vitl14') |

| FAISS Similarity Search | Enables efficient k-NN classification for few-shot learning | index = faiss.IndexFlatIP(features.shape[1]) |

| PyTorch Framework | Core deep learning infrastructure for model implementation | import torch; import torchvision.transforms |

| Data Augmentation Pipeline | Generates varied training samples from limited data | transforms.RandomHorizontalFlip(), RandomRotation() |

| Gradient Optimization | Adjusts model parameters during fine-tuning | optimizer = torch.optim.AdamW(model.parameters()) |

| Feature Visualization | Projects high-dimensional features to 2D for analysis | Principal Component Analysis (PCA), t-SNE |

Performance Optimization and Scaling

DINOv2 incorporates several technical innovations that enhance training stability and efficiency when scaling to larger models and datasets. The implementation uses Fully Sharded Data Parallel (FSDP) training across multiple GPUs with mixed-precision computation, reducing memory consumption by approximately 3× compared to previous approaches [7] [15]. The model also employs FlashAttention for efficient ViT attention computation and KoLeo regularizer to encourage uniform distribution in the feature space, preventing representation collapse [7] [11]. For parasite classification tasks, these optimizations enable researchers to work with high-resolution microscopy images (up to 518×518 pixels) while maintaining computational efficiency, which is crucial for detecting subtle morphological features that differentiate parasite species [9]. The training process also includes a final high-resolution adaptation phase that significantly improves performance on pixel-level tasks like segmentation without substantial computational overhead [11].

DINOv2 represents a significant breakthrough in computer vision, providing high-performance visual foundation models trained via self-supervised learning (SSL). Unlike supervised approaches that require extensive manually labeled datasets, DINOv2 learns directly from any collection of images without metadata, making it particularly valuable for specialized domains like medical imaging and parasitology where expert annotations are scarce and costly [13] [16]. The model family is based on the Vision Transformer (ViT) architecture, which processes images as sequences of patches and excels at capturing both global and local visual information [17]. This capability is crucial for detailed analysis in scientific applications such as parasite classification, where distinguishing subtle morphological features determines diagnostic accuracy.

A key advantage of DINOv2 is its effectiveness as a multipurpose backbone for diverse computer vision tasks. Once pre-trained, the models generate general-purpose features that can be used directly for tasks like classification, segmentation, and image retrieval without task-specific fine-tuning, often requiring only a simple linear classifier to achieve strong performance [16]. This "out-of-the-box" capability significantly simplifies deployment workflows and reduces computational overhead, especially beneficial in resource-constrained research environments focused on applications like parasite classification [13].

Model Variants and Key Characteristics

The DINOv2 family includes several model sizes, distilled from larger architectures to balance performance and efficiency [16]. The following table summarizes their key specifications and performance characteristics:

Table 1: DINOv2 Model Variants Specification and Performance Comparison

| Model Variant | Parameters | Image Embedding Dimension | Key Performance Characteristics | Inference Hardware Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DINOv2 Large (ViT-L) | ~300 million [16] | 1024 [17] | Highest accuracy; State-of-the-art on complex tasks [9] [18] | Server-grade GPU (e.g., NVIDIA A100) |

| DINOv2 Base (ViT-B) | ~86 million [17] | 768 [17] | Balanced performance/size; ~2% lower ImageNet-1k accuracy vs. fine-tuned [16] | High-end Consumer GPU (e.g., NVIDIA RTX 3080/4090) |

| DINOv2 Small (ViT-S) | ~21 million [13] | 384 | Good efficiency; Minimal accuracy drop vs. larger models [16] | Mid-range GPU/Edge Device (e.g., NVIDIA Jetson) |

Quantitative Performance in Domain-Specific Tasks

Independent validation studies across specialized domains, including medical imaging and parasitology, demonstrate the robust performance of DINOv2 models, particularly the large variant.

Table 2: DINOv2 Performance in Scientific and Medical Applications

| Application Domain | Task Description | Model Variant | Key Results | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parasite Classification | Identifying intestinal parasites from stool images [9] | DINOv2-Large | Accuracy: 98.93%, Precision: 84.52%, Sensitivity: 78.00%, Specificity: 99.57%, F1: 81.13%, AUROC: 0.97 [9] | Brondolo et al., 2025 |

| Medical Imaging (3D) | Diagnosing breast cancer, lung nodules, meniscus tears via MRI/CT [18] | MST (DINOv2-based) | AUC: 0.94 (Breast), 0.95 (Chest), 0.85 (Knee); Superior to 3D ResNet [18] | Scientific Reports, 2025 |

| Geological Analysis | Classification/segmentation of rock sample CT scans [19] | DINOv2 (Base, non-fine-tuned) | Strong out-of-distribution performance; Effective feature extraction for specialized domains [19] | Brondolo et al., 2025 |

Case Study: DINOv2 for Parasite Classification

Experimental Context and Workflow

A 2025 study validated DINOv2's effectiveness in identifying human intestinal parasitic infections (IPI), a significant global health challenge affecting billions [9]. Researchers evaluated several state-of-the-art models, including DINOv2 variants, on stool sample images to automate and improve diagnostic accuracy. The experimental workflow is summarized below:

Key Findings and Research Reagents

The study demonstrated that DINOv2-large achieved exceptional performance in parasite identification, outperforming other deep learning models like YOLOv8 and ResNet-50, and showing strong agreement with human expert assessments [9]. The following table details key research reagents and computational tools employed in this experiment:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for DINOv2-based Parasite Classification

| Reagent/Tool | Specification/Version | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| DINOv2 Models | ViT-L (Large), ViT-B (Base), ViT-S (Small) [9] | Feature extraction backbone for parasite image analysis |

| CIRA CORE Platform | In-house computing platform [9] | Operating environment for running deep learning models |

| Linear Classifier | Custom implementation | Task-specific adaptation for parasite classification |

| Stool Sample Images | Modified direct smear microscopy [9] | Raw input data for model training and evaluation |

| Reference Standards | FECT & MIF techniques [9] | Ground truth establishment by human experts |

Resource-Aware Deployment Strategies

Deployment Decision Framework

Selecting the appropriate DINOv2 variant requires careful consideration of performance requirements, computational constraints, and deployment environment. The following decision workflow provides a structured approach for researchers:

Deployment Infrastructure Considerations

Successfully deploying DINOv2 models in production environments requires appropriate infrastructure selection and configuration:

Cloud-Based Deployment: Ideal for large models (ViT-L, ViT-g) requiring scalable GPU resources. Services like AWS SageMaker, Google Vertex AI, and Microsoft Azure Machine Learning provide managed environments for serving DINOv2 models with automatic scaling [20] [21]. This approach benefits research teams needing maximum performance without managing physical hardware.

Edge Deployment: Smaller DINOv2 variants (ViT-S, ViT-B) can be deployed on edge devices with specialized processors like Neural Processing Units (NPUs) or optimized GPUs [21]. This is particularly relevant for point-of-care diagnostic applications in parasitology, where data privacy and real-time processing are prioritized over cloud connectivity.

Hybrid Approaches: For complex research workflows, a hybrid strategy can balance performance and efficiency. Larger DINOv2 models process challenging cases in the cloud, while common analyses run locally using smaller variants [20]. This architecture supports scalable parasite classification systems that maintain functionality despite network limitations.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation Guidelines

Standard Protocol for DINOv2 Feature Extraction

This protocol outlines the fundamental steps for utilizing DINOv2 models in downstream tasks like parasite classification, using the Hugging Face Transformers library.

Materials and Software Requirements

- Python 3.8+

- PyTorch 1.12+

- Transformers library

- DINOv2 model weights (facebook/dinov2-base, facebook/dinov2-large, or facebook/dinov2-small)

Procedure

- Environment Setup: Install required packages:

pip install torch transformers pillow requests - Model Initialization: Load pre-trained DINOv2 model and processor:

- Image Preprocessing: Process input images for model compatibility:

- Feature Extraction: Generate image embeddings:

- Downstream Application: Use the extracted features (lasthiddenstates) for specific tasks:

- For classification: Add a linear layer on top of the [CLS] token embeddings

- For similarity search: Compare embedding vectors using cosine similarity [17]

Protocol for Linear Probing Evaluation

This methodology evaluates DINOv2 features by training a linear classifier on top of frozen features, simulating the parasite classification study conditions [9].

Procedure

- Feature Extraction: Extract features from your labeled dataset using DINOv2 without fine-tuning.

- Classifier Design: Implement a simple linear layer that maps from the DINOv2 embedding dimension (768 for Base, 1024 for Large) to the number of target classes.

- Training Configuration:

- Keep DINOv2 weights frozen

- Train only the linear classifier

- Use standard cross-entropy loss

- Optimize with SGD or AdamW with learning rate 0.001-0.01

- Evaluation: Measure performance on held-out test set using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and AUROC.

Protocol for Model Distillation (Large to Small)

For scenarios requiring deployment of smaller models without significant performance loss, this protocol outlines knowledge distillation from DINOv2-large to DINOv2-small.

Procedure

- Setup Teacher-Student Framework: Initialize DINOv2-large as teacher and DINOv2-small as student.

- Distillation Loss: Implement a combination of:

- KL divergence between teacher and student output distributions

- Cosine similarity between feature representations

- Task-specific loss (e.g., cross-entropy with ground truth)

- Training Regimen:

- Train student to mimic teacher outputs

- Use temperature scaling in softmax for softer targets

- Gradually reduce temperature during training

- Validation: Compare distilled student performance against original large model on validation set.

The DINOv2 model family offers a versatile suite of vision foundation models that balance performance and efficiency for scientific applications. As demonstrated in parasite classification research, DINOv2-large achieves exceptional accuracy (98.93%) while smaller variants provide practical alternatives for resource-constrained environments [9]. The self-supervised nature of these models makes them particularly valuable for specialized domains with limited annotated data. By following the structured deployment framework and experimental protocols outlined in this document, researchers can effectively leverage DINOv2 capabilities to advance computational parasitology and other scientific disciplines requiring robust visual analysis.

DINOv2-Large is a self-supervised vision transformer model that demonstrates exceptional performance in automated parasite classification, offering a significant technological advancement for medical diagnostics and research. In comparative studies, it has achieved performance metrics that meet or exceed human expert capabilities, making it particularly suited for analyzing complex parasitological images.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of DINOv2-Large in Parasite Classification

| Metric | Performance Value |

|---|---|

| Accuracy | 98.93% |

| Precision | 84.52% |

| Sensitivity (Recall) | 78.00% |

| Specificity | 99.57% |

| F1 Score | 81.13% |

| AUROC | 0.97 |

Comparative analyses reveal that DINOv2-Large outperforms other deep learning models in intestinal parasite identification, including YOLOv8-m (accuracy: 97.59%) and ResNet-50 [9] [8] [10]. The model exhibits strong agreement with medical technologists, achieving Cohen's Kappa scores greater than 0.90, indicating a high level of concordance with human expert assessments [9].

Technical Foundation of DINOv2

Architectural Framework

DINOv2-Large is built upon a Vision Transformer (ViT) architecture trained using a discriminative self-supervised learning method [22] [23]. The model employs a student-teacher framework where both networks are vision transformers, with the student network learning to mimic the representations learned by the momentum teacher network [23] [24]. This approach enables the model to learn rich visual representations without requiring manually labeled datasets, which is particularly advantageous in medical domains where expert annotations are scarce and costly [9] [25].

Key Technical Innovations

The model incorporates several groundbreaking technical innovations that enhance its feature extraction capabilities:

Multi-objective training: DINOv2 combines both image-level (DINO) and patch-level (iBOT) objectives, enabling it to learn both global and local features simultaneously [24]. This dual approach is particularly beneficial for parasite classification, where both the overall structure and fine morphological details are critical for accurate identification.

Self-distillation with no labels: The training process employs knowledge distillation without labels, where a student model learns from a teacher model through cross-entropy loss applied to feature similarities [24] [13]. This allows the model to learn meaningful representations without manual annotation.

Large-scale curated training: DINOv2 was pre-trained on 142 million carefully curated images (LVD-142M), providing a robust foundation of visual features that transfer effectively to specialized domains like parasitology [26] [23] [13].

DINOv2-Large Training Framework: Illustrates the student-teacher self-distillation process with global and local crops.

Experimental Protocol for Parasite Classification

Sample Preparation and Image Acquisition

The validation protocol for DINOv2-Large in parasite classification utilizes standardized parasitological techniques for sample preparation and imaging [9] [10]:

Sample Collection: Stool samples are collected and processed using formalin-ethyl acetate centrifugation technique (FECT) and Merthiolate-iodine-formalin (MIF) techniques performed by human experts to establish ground truth.

Slide Preparation: Modified direct smears are prepared from concentrated samples to ensure optimal parasite distribution and visualization.

Image Acquisition: Microscopic images are captured at appropriate magnifications (typically 100x-400x) to resolve key morphological features of parasites, including eggs, larvae, cysts, and trophozoites.

Dataset Splitting: Acquired images are divided into training (80%) and testing (20%) datasets, ensuring representative distribution of parasite species and developmental stages.

Model Implementation and Training

The implementation protocol for fine-tuning DINOv2-Large for parasite classification involves the following steps:

Model Initialization: Load pre-trained DINOv2-Large weights, leveraging features learned from the large-scale natural image corpus.

Feature Extraction: Process parasite images through the Vision Transformer backbone to generate embeddings. The model divides images into patches (14x14 for DINOv2-Large), processes them through transformer blocks, and produces feature representations.

Fine-tuning Approach: Employ linear probing or end-to-end fine-tuning based on available data. For limited datasets, linear probing (training only the classification head) often yields strong performance.

Performance Validation: Evaluate using confusion matrices, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, precision-recall (PR) curves, and statistical measures including Cohen's Kappa and Bland-Altman analysis.

Parasite Classification Workflow: From sample preparation through model evaluation.

Performance Analysis and Comparative Evaluation

Quantitative Performance Metrics

In validation studies, DINOv2-Large demonstrated superior performance in parasite classification across multiple metrics [9] [8]. The model achieved particularly high specificity (99.57%), indicating excellent capability to correctly identify negative samples and minimize false positives - a critical requirement in diagnostic applications.

Table 2: Class-wise Performance for Different Parasite Types

| Parasite Type | Distinguishing Features | Classification Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Helminth Eggs | Large size, distinct shapes, thick shells | High precision, sensitivity, and F1 scores |

| Protozoan Cysts | Smaller size, subtle morphological features | Good performance with sufficient image quality |

| Larvae | Elongated forms, internal structures | High detection accuracy |

| Trophozoites | Delicate, amorphous shapes | Moderate performance depending on preservation |

Class-wise analysis reveals that DINOv2-Large achieves particularly high precision, sensitivity, and F1 scores for helminthic eggs and larvae, attributed to their more distinct and consistent morphological features compared to protozoan forms [9]. The model's strong performance across diverse parasite types underscores its robust feature extraction capabilities.

Comparison with Alternative Models

When evaluated against other state-of-the-art models, DINOv2-Large consistently demonstrates superior performance in parasite classification tasks:

Table 3: Model Comparison for Parasite Identification

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Sensitivity | Specificity | F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DINOv2-Large | 98.93% | 84.52% | 78.00% | 99.57% | 81.13% |

| YOLOv8-m | 97.59% | 62.02% | 46.78% | 99.13% | 53.33% |

| ResNet-50 | Data not fully specified in studies | Data not fully specified in studies | Data not fully specified in studies | Data not fully specified in studies | Data not fully specified in studies |

The performance advantage of DINOv2-Large is particularly evident in precision and F1 scores, indicating more reliable positive classifications and better balance between precision and recall compared to YOLO-based approaches [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Formalin-Ethyl Acetate | Parasite concentration and preservation for FECT technique |

| Merthiolate-Iodine-Formalin (MIF) | Fixation and staining for enhanced morphological visualization |

| Microscopy Slides and Coverslips | Sample preparation for imaging |

| DINOv2-Large Pre-trained Weights | Base model for feature extraction and transfer learning |

| CIRA CORE Platform | In-house deep learning operational framework [9] [10] |

| Python/PyTorch Environment | Model implementation, fine-tuning, and inference |

| Annotation Software | Ground truth establishment by expert parasitologists |

Advantages for Parasitology Applications

DINOv2-Large offers several distinct advantages for parasite classification research and application:

Reduced Annotation Burden: The self-supervised pre-training approach minimizes the need for extensively labeled parasitology datasets, which are time-consuming and expensive to create [25].

Superior Feature Extraction: The model captures both local features (individual morphological characteristics) and global context (overall structure), enabling accurate identification even with challenging samples [24].

Transfer Learning Capability: Features learned from natural images transfer effectively to parasitological images, demonstrating the model's robust representation learning [26].

Multi-task Capability: Beyond classification, DINOv2 embeddings support related tasks such as image retrieval, segmentation, and similarity search, providing comprehensive analytical capabilities [25] [23].

The integration of DINOv2-Large into parasitological workflows represents a significant advancement toward automated, high-throughput parasite identification systems. Its robust performance and self-supervised nature make it particularly valuable for resource-limited settings and large-scale epidemiological studies where expert microscopy resources are constrained.

The Global Health Burden of Intestinal Parasitic Infections (IPIs) and Limitations of Conventional Diagnostics

Intestinal Parasitic Infections (IPIs) represent a significant global health challenge, affecting billions of people and contributing substantially to morbidity and mortality, particularly in resource-limited settings. Conventional diagnostic techniques, while widely used, are hampered by limitations in sensitivity, specificity, and operational efficiency. This document details the global epidemiology of IPIs, quantitatively analyzes the performance of standard diagnostic methods, and provides a comprehensive protocol for the application of the DINOv2-large deep learning model to automate and enhance parasite detection in stool samples. The integration of this advanced AI tool promises to revolutionize parasitological diagnostics by improving accuracy, standardizing results, and facilitating timely public health interventions.

Global Epidemiology and Health Impact of IPIs

Intestinal Parasitic Infections are caused by a variety of helminths and protozoa, disproportionately affecting children in low- and middle-income countries and contributing to a cycle of poverty through impaired cognitive and physical development [27].

The table below summarizes key quantitative data on the prevalence and impact of IPIs from recent meta-analyses and studies.

Table 1: Global and Regional Prevalence of Intestinal Parasitic Infections

| Location | Study Population | Overall Prevalence | Most Common Parasites Identified (Prevalence) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global (CRC Patients) | Patients with Colorectal Cancer | 19.67% (95% CI: 14.81%—25.02%) | Helminths: 20.79% (95% CI: 8.35%—36.96%); Protozoa: 19.4% (95% CI: 14.07%—25.37%) | [28] |

| Ghana | Children | 22% (95% CI: 12%—34%) | Hookworm (14%), Giardia intestinalis (12%), Schistosoma mansoni (8%) | [27] |

| Northwest Ethiopia | Patients at a Health Center | 55.2% | Entamoeba histolytica/dispar (46.5%), Ascaris lumbricoides (9.2%) | [29] |

The health burden of IPIs extends beyond mere infection. A systematic review and meta-analysis have identified a significant association between IPIs and colorectal cancer (CRC), with infected individuals having 3.61 times higher odds (95% CI: 2.41—5.43) of developing CRC [28]. The proposed mechanisms for this association include the induction of chronic inflammation, increased oxidative stress leading to DNA damage, and production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, and NF-κB, which collectively create a microenvironment conducive to carcinogenesis [28].

Conventional Diagnostic Techniques and Their Limitations

Despite the development of molecular methods, conventional techniques remain the gold standard for routine diagnosis of IPIs in most settings, primarily due to their simplicity and cost-effectiveness [8] [9].

Table 2: Conventional Diagnostic Methods for IPIs and Their Limitations

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations & Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formalin-Ether Centrifugation Technique (FECT) | Concentration of parasites via centrifugation using formalin-ether solution. | Suitable for preserved samples; improves detection of low-level infections. | Variable results based on analyst; procedure complexity [9]. |

| Merthiolate-Iodine-Formalin (MIF) Technique | Fixation and staining of stool samples for direct examination. | Easy preparation; long shelf life; good for field surveys. | Can distort trophozoite morphology; incompatibility with some stains [9]. |

| Kato-Katz Technique | Microscopic examination of a standardized smear of stool. | Simplicity; low cost; allows for egg quantification. | Unsuitable for multiple infections; performance varies with parasitic load [9]. |

| Direct Saline Wet Mount | Direct microscopic examination of fresh stool in saline. | Rapid; cost-effective; provides definitive diagnosis for primary assessment. | Low sensitivity for low-intensity infections; highly dependent on technician skill [29]. |

The primary limitations of these methods are their dependency on highly skilled technicians, subjectivity in interpretation, and variable sensitivity and specificity, especially for protozoan species with similar morphologies or in cases of low parasitic load [9]. These challenges underscore the need for innovative, automated diagnostic solutions.

Protocol: Application of the DINOv2-Large Model for Automated IPI Diagnosis

This protocol outlines the methodology for training and validating the DINOv2-large deep learning model for the identification of intestinal parasites from stool sample images, leveraging a self-supervised learning approach.

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end workflow for the AI-enhanced diagnostic process, from sample preparation to final classification.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Stool Examination and AI Model Development

| Item | Function/Application | Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Formalin-Ethyl Acetate | Parasite fixation and concentration in FECT. | Standardized reagents are critical for consistent sample preparation and image quality. |

| Merthiolate-Iodine-Formalin (MIF) | Fixation and staining of cysts, oocysts, and helminth eggs. | Preferred for field surveys due to long shelf life; enhances visual contrast for imaging [9]. |

| DINOv2-large Model | Self-supervised feature extraction from stool sample images. | Vision Transformer (ViT) architecture; pre-trained on curated dataset for robust feature learning [9]. |

| CIRA CORE Platform | Operational platform for running deep learning models. | In-house platform used to operate YOLO and DINOv2 models for parasite identification [9]. |

| Annotated Image Dataset | Training and testing data for deep learning models. | Dataset should include images of helminth eggs, larvae, and protozoan cysts/oocysts from modified direct smears [9]. |

Step-by-Step Experimental Procedure

Phase 1: Ground Truth Establishment and Dataset Curation

- Sample Processing: Collect fresh stool samples and process them using both the FECT and MIF techniques, performed by expert medical technologists. This establishes the diagnostic "ground truth" [9].

- Image Acquisition: From a modified direct smear of the samples, acquire high-resolution digital images using a microscope with an attached digital camera. Ensure consistent lighting and magnification across images.

- Data Annotation: Categorize images into training (80%) and testing (20%) datasets. For object detection models like YOLO, manually label images with bounding boxes and class labels for each parasitic object.

Phase 2: Model Training and Validation

- Model Selection: Employ the DINOv2-large model, a self-supervised learning model that learns features without manual labeling, and compare it against other models like YOLOv8-m and ResNet-50 [9].

- Feature Extraction & Training: Use the DINOv2-large model to extract discriminative features from the input images. Train a sequential classifier on top of these features to map them to specific parasite classes.

- Performance Validation: Evaluate the model on the held-out test set using the following metrics. The expected performance, based on published validation, is summarized below.

Table 4: Performance Metrics of Deep Learning Models in Parasite Identification

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Sensitivity (Recall) | Specificity | F1 Score | AUROC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DINOv2-large | 98.93% | 84.52% | 78.00% | 99.57% | 81.13% | 0.97 |

| YOLOv8-m | 97.59% | 62.02% | 46.78% | 99.13% | 53.33% | 0.755 |

| Human Expert (Benchmark) | Varies | Varies | Varies | Varies | Varies | - |

- Statistical Agreement: Assess the model's agreement with human experts using Cohen's Kappa (expecting a κ > 0.90, indicating strong agreement) and Bland-Altman analysis to visualize bias [9].

The integration of the DINOv2-large model into the diagnostic workflow for IPIs represents a paradigm shift, addressing critical limitations of conventional microscopy. Its high accuracy, specificity, and strong agreement with human experts demonstrate its potential for use in clinical and public health settings. The adoption of this AI-driven approach can facilitate early detection, high-throughput screening, and more effective management of IPIs, thereby reducing their global health burden. Future work should focus on the deployment of this technology in field settings and its continuous training with diverse datasets to enhance generalizability across different geographical regions.

Implementing DINOv2-Large: A Step-by-Step Pipeline for Parasite Classification

The application of deep learning models, such as DINOv2-large, to the classification of intestinal parasites represents a significant advancement in diagnostic parasitology [9]. These models show exceptional performance, with reported accuracy of 98.93% and a specificity of 99.57% in identifying parasitic elements [9] [8]. However, this performance is fundamentally dependent on the quality and integrity of the underlying digital image datasets. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for the systematic acquisition and preparation of image datasets from stool samples, specifically contextualized within a research framework utilizing the DINOv2-large model for parasite classification.

Data Acquisition: From Sample to Digital Image

The process of converting a physical stool sample into a usable digital image dataset requires meticulous attention to laboratory techniques and imaging protocols.

Laboratory Processing and Staining Techniques

The initial sample handling sets the foundation for image quality. The following techniques are commonly employed to prepare samples for microscopy, each with distinct advantages for subsequent deep learning analysis.

- Formalin-Ethyl Acetate Centrifugation Technique (FECT): This concentration technique is considered a gold standard for routine diagnosis [9]. It involves mixing the stool sample with a formalin-ether solution followed by centrifugation. This process improves the detection of low-level infections by concentrating parasitic elements [9]. Its simplicity and cost-effectiveness make it suitable for creating large-scale datasets.

- Merthiolate-Iodine-Formalin (MIF) Technique: This technique serves as an effective fixation and staining solution with easy preparation and a long shelf life, making it suitable for field surveys [9]. It provides competitive performance for evaluating a variety of intestinal parasitic infections (IPIs) [9]. A noted limitation is the potential for iodine to cause distortion, which must be considered during image annotation [9].

Digital Image Capture

Once prepared, slides are digitized using microscopy. Consistency in imaging is critical.

- Microscopy: Use a standard light microscope connected to a digital camera.

- Standardization: Maintain consistent magnification (typically 100x, 400x for protozoa) across images. Ensure uniform lighting conditions to avoid shadows and glare that could introduce artifacts.

- Resolution: Capture images at a high resolution to ensure that minute morphological features of parasites are preserved for the model to learn. The DINOv2-large model, being a Vision Transformer, processes images as a sequence of patches; high-resolution input allows for richer feature extraction [22].

Data Preprocessing and Region of Interest (ROI) Segmentation

Raw microscopic images often contain background and debris that can hinder model performance. Segmenting the Region of Interest (ROI) is a crucial preprocessing step.

Automated ROI Segmentation for Stool Images

An effective method for segmenting the stool region from the background uses saturation channel analysis and optimal thresholding [30]. The procedure is as follows:

- Color Space Transformation: Convert the original RGB image to a color space that separates saturation, such as HSV.

- Saturation Channel Extraction: Isolate the saturation component. The discrimination between stool and background is typically high in saturation maps [30].

- Optimal Thresholding: Employ an adaptive algorithm, such as the Otsu method, to determine the optimal threshold value

Tthat maximizes the inter-class variance between foreground (stool) and background pixels [30]. The operation is defined as:f(x,y)={1,g(x,y)<T; 0,g(x,y)≥T}, whereg(x,y)represents pixel values [30]. - Binary Mask Application: The resulting binary mask is used to extract the ROI from the original image, isolating the stool material for classification.

This approach reduces computational load and focuses the model's attention on relevant features.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete pipeline from sample collection to dataset preparation.

Dataset Preparation for Model Training

Expert Annotation and Ground Truth Establishment

Human experts perform techniques like FECT and MIF to establish the ground truth and reference for parasite species [9]. Subsequent annotation of digital images can follow two paradigms:

- Classification Dataset: Images are assigned a single class label (e.g., Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Uninfected).

- Object Detection Dataset: Each parasitic object within an image is localized with a bounding box and assigned a class label. This is crucial for identifying multiple infections in a single sample [9].

Dataset Splitting

For model development and evaluation, the annotated dataset should be partitioned as follows:

- Training Set (80%): Used to train the deep learning model.

- Testing Set (20%): Used for the final evaluation of the model's performance [9].

This split ensures the model is evaluated on data it has not seen during training, providing a realistic measure of its generalizability.

Performance of Deep Learning Models on Stool Datasets

The table below summarizes the quantitative performance of various deep learning models on intestinal parasite image classification, providing a benchmark for expected outcomes.

Table 1: Performance comparison of deep learning models in intestinal parasite identification. [9] [8]

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | F1-Score (%) | AUROC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DINOv2-large | 98.93 | 84.52 | 78.00 | 99.57 | 81.13 | 0.97 |

| YOLOv8-m | 97.59 | 62.02 | 46.78 | 99.13 | 53.33 | 0.755 |

| ConvNeXt Tiny | ~98.6* (F1) | N/R | N/R | N/R | 98.6 | N/R |

| MobileNet V3 S | ~98.2* (F1) | N/R | N/R | N/R | 98.2 | N/R |

Note: N/R = Not explicitly reported in the provided search results. Performance metrics for ConvNeXt Tiny and MobileNet V3 S are derived from a related study on helminth classification, where F1-score was the primary metric reported. [31]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions for setting up the described experiments.

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for stool sample processing and imaging.

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Formalin (10%) | Fixative for preserving parasitic morphology in stool samples for FECT. |

| Ethyl Acetate | Solvent used in the concentration technique to separate debris from parasitic elements. |

| Merthiolate-Iodine-Formalin (MIF) | A combined fixative and stain used for the preservation and visualization of cysts, oocysts, and eggs. |

| Microscope & Digital Camera | For high-resolution image acquisition of prepared slides. |

| Annotation Software | Software tools for labeling images with bounding boxes and class labels to create ground truth data. |

Implementation Notes for DINOv2-large

The DINOv2-large model is a Vision Transformer (ViT) pre-trained in a self-supervised fashion on a large collection of images [22]. To fine-tune it for parasite classification:

- Feature Extraction: The model learns an inner representation of images that can be used to extract features useful for classification [22].

- Classifier Placement: A standard linear layer is typically placed on top of the pre-trained encoder, often using the

[CLS]token's last hidden state as a representation of the entire image [22]. - Input Data: The model requires images to be presented as a sequence of fixed-size patches [22]. Ensure your preprocessing pipeline outputs consistently sized, high-quality ROIs.

The high performance of DINOv2-large, as shown in Table 1, underscores its potential for accurate and automated parasite diagnostics, facilitating timely and targeted interventions [9].

This application note details the image preprocessing pipeline for the DINOv2-large model, specifically contextualized within a research program aimed at the classification of intestinal parasites from stool sample images. The performance of deep learning models is profoundly dependent on the quality and consistency of input data. For a specialized visual task such as parasite classification, which involves distinguishing between morphologically similar species often in complex and noisy backgrounds, a robust and optimized preprocessing protocol is not merely beneficial—it is essential. This document provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed, experimentally-validated protocol for image preprocessing to maximize the efficacy of the DINOv2-large model in this critical domain.

The Critical Role of Preprocessing in DINOv2 Performance

The DINOv2 model, a state-of-the-art vision foundation model, generates rich image representations through self-supervised learning. Its performance on downstream tasks, however, is highly sensitive to input data conditions. Evidence from independent research highlights that an insignificant bug in the preprocessing stage, where image scaling was incorrectly omitted for NumPy array inputs, led to a significant performance drop of 10-15% on medical image analysis [32]. This underscores the non-negotiable requirement for a meticulous and correct preprocessing workflow.

Furthermore, studies validating deep-learning-based approaches for stool examination have demonstrated that the DINOv2-large model achieves superior performance in parasite identification, with reported metrics of 98.93% accuracy, 84.52% precision, 78.00% sensitivity, and 99.57% specificity [9] [8]. These results were contingent on proper image handling, reinforcing the need for the standardized protocol outlined herein.

Standard Preprocessing Protocol for DINOv2

This section defines the core, mandatory image transformation steps required to correctly format images for the DINOv2 model. Adherence to this protocol ensures compatibility with the model's expectations, which were established during its pretraining on large-scale datasets like ImageNet.

Detailed Step-by-Step Transformation

The standard preprocessing sequence is implemented as a torchvision.transforms pipeline. The following code block presents the canonical transformation procedure.

Protocol Component Specifications

Table 1: Specification of Standard Preprocessing Steps.

| Step | Parameter | Value | Purpose & Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resize | Size | 256 pixels on shorter side | Standardizes image size while initially preserving aspect ratio. |

| Interpolation | BICUBIC |

Provides higher-quality downsampling compared to bilinear. | |

| CenterCrop | Output Size | 224x224 pixels | Provides the exact input dimensions expected by the model, removing potential peripheral bias. |

| ToTensor | - | - | Converts a PIL Image or NumPy array to a PyTorch Tensor and scales pixel values to [0, 1] range. Crucial: Scaling is only automatic for PIL Images, not NumPy arrays [32]. |

| Normalize | Mean | [0.485, 0.456, 0.406] | Standard ImageNet channel-wise mean. Centers data. |

| Std | [0.229, 0.224, 0.225] | Standard ImageNet channel-wise standard deviation. Scales data. |

The following diagram illustrates the sequential flow of this standard preprocessing pipeline.

Advanced Preprocessing for Domain-Specific Challenges in Parasitology

Microscopic images of stool samples present unique challenges that the standard pipeline alone may not adequately address. These include variable lighting, complex biological debris, and the presence of tiny, low-contrast target objects (e.g., parasite eggs). The integration of additional preprocessing stages can significantly enhance model performance by reducing the domain gap between natural images (on which DINOv2 was trained) and medical images.

Low-Light Image Enhancement (LLIE)

Images captured under suboptimal lighting conditions can obscure critical morphological features. A low-light enhancement step can restore details and improve contrast.

Protocol: Conditional Low-Light Enhancement

- Brightness Assessment: Calculate the average pixel intensity of the grayscale-converted image.

- Thresholding: If the average intensity falls below a predefined threshold (e.g., 50 out of 255), apply an enhancement model.

- Enhancement Model: Employ a state-of-the-art LLIE model such as HVI [33] or CIDNet. These models operate in specialized color spaces to mitigate color bias and brightness artifacts, which is crucial for preserving the true color of stained parasites.

- Integration: This enhancement step should be applied before the standard DINOv2 transformation pipeline.

Background Removal and Region of Interest (ROI) Localization

A significant source of noise in stool sample images is the complex background, which can lead to false positives during model inference. Using foundational models to isolate the region of interest is an effective strategy.

Protocol: ROI Localization with Grounding-DINO and SAM

- Text-Guided Detection: Use an open-vocabulary detector like Grounding-DINO [33] with a task-specific text prompt (e.g., "parasite eggs," "helminth," or "protozoan cysts") to generate a bounding box around the region of interest.

- Image Cropping: Crop the image using the predicted bounding box coordinates.

- Segmentation Refinement (Optional): For more precise localization, the Segment Anything Model (SAM) can be used within the cropped region to generate pixel-level masks for individual objects [33].

- Camera Intrinsics Adjustment: If depth information is used or precise spatial measurement is required, adjust the camera intrinsics to account for the shifted image origin post-cropping.

The workflow for this advanced, domain-adapted preprocessing is more complex and is summarized in the following diagram.

Experimental Validation & Performance Data

The efficacy of the DINOv2 model, when fed with properly preprocessed data, has been rigorously validated in parasitology research. The following table summarizes key quantitative results from a recent benchmark study that compared multiple deep learning models on the task of intestinal parasite identification [9] [8].

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Deep Learning Models in Intestinal Parasite Identification.

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | F1-Score (%) | AUROC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DINOv2-Large | 98.93 | 84.52 | 78.00 | 99.57 | 81.13 | 0.97 |

| DINOv2-Base | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided |

| DINOv2-Small | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided |

| YOLOv8-m | 97.59 | 62.02 | 46.78 | 99.13 | 53.33 | 0.755 |

| ResNet-50 | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided |

Key Findings:

- The DINOv2-large model consistently outperformed other state-of-the-art models across all major metrics, demonstrating its exceptional capability for fine-grained parasite classification [9].

- The study reported a strong level of agreement (Cohen's Kappa > 0.90) between the classifications made by DINOv2 models and those made by human medical technologists, validating its potential for use in clinical diagnostics [9].

- Class-wise analysis revealed that models achieved higher precision, sensitivity, and F1-scores for helminthic eggs and larvae due to their more distinct and larger morphological structures compared to protozoan cysts [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Software and Model Components for the Preprocessing Pipeline.

| Item Name | Type / Version | Function in the Pipeline | Key Parameters / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DINOv2-Large | Vision Foundation Model | Core model for feature extraction and classification of preprocessed images. ViT-L/14 architecture with 300M+ parameters [34]. | |

| Grounding-DINO | Open-Vocabulary Object Detector | Localizes regions of interest in images using text prompts (e.g., "parminth eggs"), enabling automated background removal [33]. | Prompt engineering is critical for performance. |

| Segment Anything Model (SAM) | Image Segmentation Model | Generates high-quality object masks from ROI-cropped images; used for isolating individual parasites or eggs [33]. | Can be computationally intensive; FastSAM is a lighter alternative [33]. |

| HVI / CIDNet | Low-Light Image Enhancement Model | Restores detail and improves contrast in underexposed microscopy images, mitigating poor lighting artifacts [33]. | Applied conditionally based on average image intensity. |

| PyTorch & Torchvision | Deep Learning Framework | Provides the foundational code environment, data loaders, and standard image transformations (Resize, ToTensor, Normalize). | Ensure version compatibility with model repositories. |

| PIL (Pillow) | Image Library | Handles image loading, format conversion (e.g., RGBA to RGB), and basic image manipulation. | Critical for correct ToTensor() operation [32]. |

DINOv2-Large represents a significant advancement in self-supervised learning for computer vision, providing a powerful backbone for extracting rich visual embeddings without task-specific fine-tuning. Developed by Meta AI, DINOv2 is a Vision Transformer (ViT) model pretrained using a self-supervised methodology on a massive dataset of 142 million images, curated from 1.2 billion source images [13] [16]. This extensive training enables the model to learn robust visual representations that generalize effectively across diverse domains and applications. Unlike approaches that rely on image-text pairs, DINOv2 learns features directly from images, allowing it to capture detailed local information often missed by caption-based methods [16]. This capability makes it particularly valuable for specialized domains like medical image analysis, where textual descriptions may be insufficient or unavailable.

The "Large" variant refers to the ViT-L/14 architecture containing approximately 300 million parameters, positioning it as a substantial but manageable model for research applications [22] [35]. A key innovation of DINOv2 is its training through self-distillation, where a student network learns to match the output of a teacher network without requiring labeled data [13] [36]. This approach, combined with patch-level objectives inspired by iBOT that randomly mask input patches, enables the model to develop a comprehensive understanding of both global image context and local semantic features [36]. The resulting model produces high-performance visual features that can be directly employed with simple classifiers such as linear layers, making it suitable for various computer vision tasks including classification, segmentation, and depth estimation [35] [16].

Performance Evidence in Parasite Classification

Recent research has demonstrated the exceptional capability of DINOv2-Large for parasite classification in stool examinations. A comprehensive 2025 study published in Parasites & Vectors evaluated multiple deep learning models for intestinal parasite identification, with DINOv2-Large achieving state-of-the-art performance [9] [8] [37]. The study utilized formalin-ethyl acetate centrifugation technique (FECT) and Merthiolate-iodine-formalin (MIF) techniques performed by human experts as ground truth, with images collected through modified direct smear methods and split into 80% training and 20% testing datasets [9].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of DINOv2-Large in Parasite Classification

| Metric | Performance Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 98.93% | Overall correctness of classification |

| Precision | 84.52% | Ability to avoid false positives |

| Sensitivity (Recall) | 78.00% | Ability to identify true positives |

| Specificity | 99.57% | Ability to identify true negatives |

| F1 Score | 81.13% | Balance between precision and recall |

| AUROC | 0.97 | Overall classification performance (0-1 scale) |

When compared against other state-of-the-art models including YOLOv4-tiny, YOLOv7-tiny, YOLOv8-m, ResNet-50, and other DINOv2 variants, DINOv2-Large demonstrated superior performance across multiple metrics [9] [8]. The study reported that all models achieved a Cohen's Kappa score greater than 0.90, indicating an "almost perfect" level of agreement with human experts, with DINOv2-Large showing particularly strong performance in helminthic egg and larvae identification due to their distinct morphological characteristics [9] [37]. The remarkable specificity of 99.57% is especially significant for diagnostic applications, as it minimizes false positives that could lead to unnecessary treatments.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Deep Learning Models in Parasite Identification

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Sensitivity | Specificity | F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DINOv2-Large | 98.93% | 84.52% | 78.00% | 99.57% | 81.13% |

| YOLOv8-m | 97.59% | 62.02% | 46.78% | 99.13% | 53.33% |

| DINOv2-Small | Data not fully specified | Data not fully specified | Data not fully specified | Data not fully specified | Data not fully specified |

| YOLOv4-tiny | Data not fully specified | Data not fully specified | Data not fully specified | Data not fully specified | Data not fully specified |

The research concluded that DINOv2-Large's performance highlights the potential of integrating deep-learning approaches into parasitic infection diagnostics, potentially enabling earlier detection and more accurate diagnosis through automated detection systems [9] [38]. This is particularly valuable for addressing intestinal parasitic infections, which affect approximately 3.5 billion people globally and cause more than 200,000 deaths annually [8] [37].

Protocol: Feature Extraction Workflow for Parasite Imaging

Sample Preparation and Image Acquisition

The initial phase of the protocol involves careful sample preparation and standardized image acquisition to ensure consistent and reliable feature extraction. For intestinal parasite identification, the established methodology involves preparing stool samples using the formalin-ethyl acetate centrifugation technique (FECT) or Merthiolate-iodine-formalin (MIF) technique, which serve as the gold standard for parasite preservation and visualization [9] [8]. Following concentration techniques, modified direct smears are prepared on microscope slides to create uniform specimens for imaging [37]. Images should be captured using a standardized digital microscopy system with consistent magnification, lighting conditions, and resolution across all samples. The recommended image format is lossless (such as PNG or TIFF) to preserve fine morphological details crucial for accurate feature extraction. The dataset should be systematically organized, with 80% allocated for training and 20% for testing, mirroring the validation approach used in the published research [9].

Implementation Code for Feature Extraction

The following Python code demonstrates how to implement feature extraction using DINOv2-Large for parasite images:

This implementation provides two approaches for feature extraction: using the Hugging Face Transformers library or PyTorch Hub. The Hugging Face approach offers simpler integration with modern ML workflows, while the PyTorch Hub method provides access to additional model outputs and functionalities [22] [35].

Embedding Processing and Classification

Once features are extracted, they require processing before being used for classification tasks. The DINOv2-Large model outputs patch-level embeddings and a [CLS] token embedding that represents the entire image. For parasite classification, the [CLS] token embedding is typically used as the image-level representation [22]. These 1,296-dimensional embeddings can then be fed into a simple linear classifier:

This approach leverages the strong representational power of DINOv2-Large embeddings while maintaining a simple and interpretable classification head, which demonstrated exceptional performance in parasite identification tasks with 98.93% accuracy [9].

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Formalin-Ethyl Acetate | Concentration technique for parasite eggs, cysts, and larvae in stool samples | CDC-standardized concentration method [9] [8] |

| Merthiolate-Iodine-Formalin (MIF) | Fixation and staining solution for protozoan cysts and helminth eggs | Long shelf life, suitable for field surveys [9] [37] |

| DINOv2-Large Model | Feature extraction from parasite images | ViT-L/14 architecture, 300M parameters, self-supervised [22] [35] |

| CIRA CORE Platform | Deep learning model operation and evaluation | In-house platform for model training and inference [9] [37] |

| PyTorch with Transformers | Model implementation and inference | PyTorch 2.0+, transformers library [22] [35] |

Advanced Applications and Integration

The application of DINOv2-Large extends beyond basic parasite classification to more sophisticated diagnostic and research applications. The model's robust feature embeddings enable few-shot learning scenarios, where limited labeled examples are available for rare parasite species, leveraging its strong performance even with minimal fine-tuning [16]. Additionally, the patch-level features extracted by DINOv2-Large can be utilized for localization tasks, potentially identifying multiple parasite types within a single image or detecting parasites in complex backgrounds [13] [39].

For large-scale studies, the embeddings can be employed for content-based image retrieval, allowing researchers to quickly identify similar parasite morphologies across extensive databases. The strong out-of-domain performance noted in Meta's research suggests that models pretrained on DINOv2-Large features could generalize well to novel parasite species or imaging conditions not encountered during training [16]. This capability is particularly valuable for emerging parasitic infections or when adapting diagnostic systems to new geographical regions with different parasite distributions.

Future integration pathways include combining DINOv2-Large with lightweight task-specific heads for mobile deployment in field settings, or incorporating the features into multimodal systems that combine visual characteristics with clinical metadata or molecular data for comprehensive diagnostic assessments. The demonstrated performance in medical imaging tasks positions DINOv2-Large as a foundational component in next-generation parasitic infection diagnostics and research tools.

This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for integrating linear classifiers with the DINOv2-large model, specifically within the context of parasite classification research. The DINOv2 (Distillation with NO labels) model, developed by Meta Research, is a self-supervised vision transformer (ViT) that learns robust visual features from unlabeled images [35] [7]. Its ability to generate high-quality, general-purpose visual features makes it particularly valuable for specialized domains like medical and biological imaging, where labeled data is often scarce [40]. For researchers in parasitology and drug development, leveraging DINOv2's frozen features with a simple linear classifier enables the creation of highly accurate diagnostic tools without the computational expense and data requirements of full model fine-tuning [9] [40]. Recent validation studies have demonstrated the efficacy of this approach, with DINOv2-large achieving an accuracy of 98.93% in intestinal parasite identification, outperforming many traditional supervised models [9].

DINOv2 models produce powerful visual representations through self-supervised pre-training on a massive dataset of 142 million images [35] [7]. Unlike text-supervised models like CLIP, DINOv2 excels at capturing visual structure, texture, and spatial details—characteristics crucial for differentiating morphologically similar parasite eggs and cysts [40]. The model employs a combination of knowledge distillation and masked image modeling objectives, allowing it to learn both global image context and local patch-level information [7]. This dual understanding enables the model to discern fine-grained visual patterns that might be imperceptible to human observers or traditional computer vision approaches.

For parasite classification, the DINOv2-large model (ViT-L/14) is particularly recommended due to its superior performance on fine-grained visual tasks [9]. When using DINOv2 for classification, the standard approach involves keeping the backbone "frozen" (i.e., not updating its weights during training) and training only a linear classifier on top of the extracted features [40]. This transfer learning strategy is highly effective in low-data regimes common in medical imaging, as it leverages the general visual knowledge encoded in the pre-trained backbone while requiring minimal task-specific labeled data.

Experimental Protocols

Feature Extraction Protocol

Objective: Extract meaningful feature representations from parasite images using the frozen DINOv2-large backbone.

Materials:

- DINOv2-large model (

dinov2_vitl14ordinov2_vitl14_reg) - Microscope image dataset of parasite eggs/cysts (e.g., Ascaris lumbricoides, Taenia saginata)

- Computing environment with GPU acceleration and PyTorch

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

Model Initialization:

Feature Extraction:

- Process images through the model in batches

- Extract the [CLS] token or patch tokens as feature representations

- Save features and corresponding labels for classifier training

Validation: Extracted features should have dimensionality of 1024 for DINOv2-large. Visualize features using PCA to ensure class separation before proceeding to classification.

Linear Classifier Training Protocol

Objective: Train a linear layer to map DINOv2 features to parasite classes.

Materials:

- Extracted features from protocol 2.1

- PyTorch with optimizers and loss functions

- Standard computing environment

Procedure:

- Classifier Architecture:

Training Configuration:

- Optimization: SGD with momentum (0.9) or AdamW

- Learning rate: 0.001-0.01 (typically lower than standard training)

- Batch size: 32-128 (adjust based on dataset size)