Cross-Reactivity in Immunoassays: Advanced Strategies for Detection, Troubleshooting, and Validation in Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals confronting the pervasive challenge of cross-reactivity in immunoassays.

Cross-Reactivity in Immunoassays: Advanced Strategies for Detection, Troubleshooting, and Validation in Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals confronting the pervasive challenge of cross-reactivity in immunoassays. It explores the fundamental causes and impacts of cross-reactivity, from structural similarity to reagent choice. The content delivers practical methodological approaches for detection and application, advanced techniques for troubleshooting and optimization, and robust frameworks for assay validation and comparative analysis against gold-standard methods. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with cutting-edge strategies, this resource empowers scientists to improve assay reliability, data accuracy, and decision-making in preclinical and clinical studies.

Understanding Immunoassay Cross-Reactivity: From Fundamental Causes to Clinical Consequences

FAQs: Understanding and Troubleshooting Cross-Reactivity

What is cross-reactivity in the context of an immunoassay?

Cross-reactivity is the ability of an antibody to bind to molecules other than its intended target antigen. These molecules, called cross-reactants, often have a high structural similarity or homology to the target analyte [1]. This is not merely nonspecific binding; it is a specific reaction with a known, structurally similar substance that can be proven experimentally [2] [1].

Why is cross-reactivity more than just a nuisance in drug development?

In drug development, cross-reactivity is a critical safety and efficacy parameter. For therapeutic antibodies, a standard required test prior to Phase I clinical studies is the Tissue Cross-Reactivity (TCR) assay [2]. This immunohistochemistry-based method screens for off-target binding of the therapeutic candidate to human tissues, helping to identify potential toxicities early in the development process [3]. Undetected cross-reactivity can lead to drug failure or adverse patient effects.

I am developing a multiplex assay. What types of cross-reactivity should I test for?

In a multiplexed array format, where multiple assays run simultaneously on a single sample, you must test for several specific types of cross-reactivity to ensure each result is a true positive [4]. The table below summarizes the key types.

Table: Types of Cross-Reactivity in Multiplex Immunoassays

| Type of Cross-Reactivity | Description | Impact on Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Antigen-Capture Antibody [4] | A capture antibody binds the wrong antigen. | The two cross-reactive systems cannot be multiplexed under the tested conditions. |

| Detection-Capture Antibody [4] | A detection antibody binds directly to a capture antibody spot. | Often resolvable through reagent or diluent optimization. |

| Antigen-Detection Antibody [4] | A captured antigen is detected by the detection antibody from a different assay. | Not necessarily problematic; can sometimes be used as an additional detection method. |

| Capture Antibody-Conjugate [4] | The label (e.g., streptavidin-HRP) binds directly to a capture antibody. | Unacceptable; must be resolved for the assay to be valid. |

| Antigen-Conjugate [4] | The label binds directly to a captured antigen. | Unacceptable; must be resolved for the assay to be valid. |

My immunoassay is producing false positives. How can I determine if cross-reactivity is the cause?

A core experimental method to test for sample-based interference, including cross-reactivity, is the spike and recovery experiment [5]. This validation assesses whether components in a sample matrix interfere with accurate analyte detection.

Protocol: Spike and Recovery Experiment

- Sample Preparation: Prepare three sets of samples in duplicate or triplicate:

- Neat Matrix: The sample matrix (e.g., serum, plasma) with no additions.

- Spiked Buffer (Control): A known concentration of the pure analyte spiked into an ideal assay buffer.

- Spiked Matrix (Test): The same known concentration of analyte spiked into the actual sample matrix.

- Analysis: Run all samples according to your assay protocol.

- Calculation and Interpretation: Calculate the percentage recovery for the spiked matrix compared to the spiked buffer control [5].

Table: Interpreting Spike and Recovery Results

| % Recovery | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 80–120% | Acceptable; minimal interference. |

| < 80% | Signal suppression; indicates matrix interference. |

| > 120% | Signal enhancement; suggests interference or cross-reactivity. |

A recovery value outside the acceptable range indicates that something in the sample matrix is interfering, prompting further investigation into the root cause [5].

How can I reduce or prevent cross-reactivity in my assays?

Several strategic and practical steps can minimize cross-reactivity:

- Use High-Affinity, Specific Antibodies: Antibodies with high affinity are less likely to have problematic cross-reactivity [1]. Monoclonal antibodies often provide higher specificity than polyclonal antibodies because they recognize a single epitope [6].

- Employ Blocking Agents: Use normal serum, Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), casein, or commercial heterophilic antibody blockers to saturate potential interfering sites and prevent nonspecific binding [5].

- Optimize Assay Conditions: Cross-reactivity is not an immutable property of the antibodies alone. It can be influenced by the assay format, the concentrations of immunoreactants, and the reaction time. Shifting to assays that use lower reagent concentrations can sometimes increase specificity and lower cross-reactivity [7].

- Dilute the Sample: Dilution can reduce the concentration of interfering substances. Ensure the assay is validated for diluted samples [5] [6].

- Utilize Matched Antibody Pairs: Using validated matched monoclonal or polyclonal antibody pairs can significantly improve specificity [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Cross-Reactivity Assessment and Mitigation

| Reagent / Material | Function in Cross-Reactivity Studies |

|---|---|

| Monoclonal Antibodies [6] | Provide high specificity by recognizing a single epitope; ideal as capture antibodies to establish assay specificity. |

| Blocking Agents (BSA, Casein) [5] | Reduce nonspecific binding by saturating potential interfering sites on the solid support or sample proteins. |

| Heterophilic Antibody Blockers [5] | Specifically reduce interference from human anti-animal antibodies (HAAA), a common source of false positives. |

| Positive Control Sera/Plasma [5] | Contain known interferents (e.g., HAMA, Rheumatoid Factor) used as controls to validate mitigation strategies. |

| Matrix Effects Controls [5] | Purified substances (e.g., bilirubin, hemoglobin, cholesterol) used to spike samples and characterize their interfering effects. |

| High-Throughput Protein Arrays [3] | Platforms that screen antibody binding against hundreds or thousands of protein targets simultaneously to comprehensively profile cross-reactivity. |

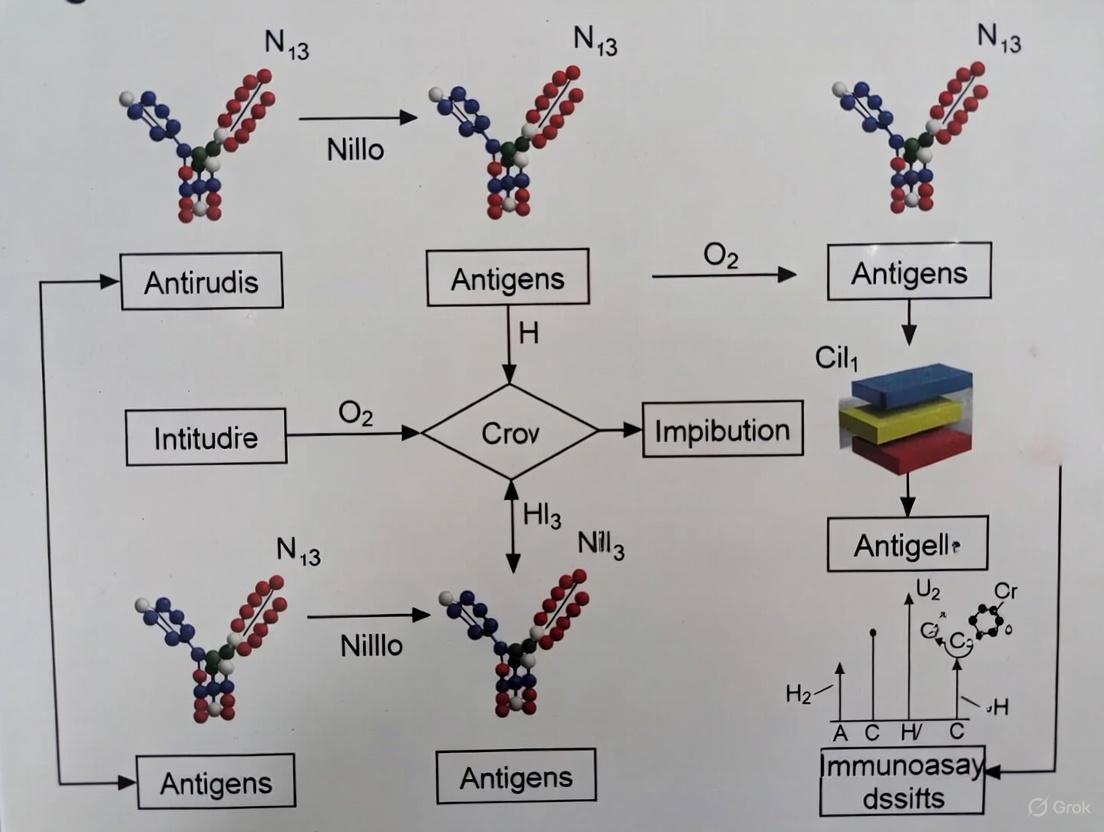

Experimental Guide: A Workflow for Systematic Cross-Reactivity Assessment

For a rigorous assessment, follow a structured workflow. The diagram below outlines the key stages, from initial testing to implementation of solutions.

A critical step is quantifying the level of cross-reactivity, especially in competitive immunoassays. The most accepted method is to compare the dose-response curves of the target analyte and the cross-reactant.

Protocol: Calculating Percent Cross-Reactivity

- Generate Dose-Response Curves: For both the target analyte and the potential cross-reactant, run a dilution series to create standard curves. The assay should be performed under equilibrium conditions for accurate comparison [7] [8].

- Determine IC50 Values: Calculate the concentration of each substance that causes a 50% decrease in the maximum assay signal (e.g., 50% binding of the labeled analyte) [2] [8].

- Calculate % Cross-Reactivity: Use the following formula [8]: > % Cross-Reactivity = (IC50 of Target Analyte / IC50 of Cross-Reactant) × 100%

A lower percentage indicates higher specificity of the assay for the target analyte over the interfering substance. This quantitative measure is essential for validating an assay's reliability [8].

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the fundamental mechanism behind antibody cross-reactivity? Cross-reactivity occurs when an antibody's antigen-binding site (paratope) recognizes and binds to two or more different antigens that share similar structural regions or epitopes. This similarity can exist in the three-dimensional shape and physicochemical properties of the epitopes, even if their amino acid sequences aren't identical. The antibody's Fab region has a specific amino acid sequence that dictates its affinity, and if another antigen presents a sufficiently similar structural region, binding can occur [9].

Why do some assays show cross-reactivity while others don't, even with the same antibodies? Cross-reactivity is not an intrinsic property of antibodies alone but is significantly influenced by assay conditions. Immunoassays implemented with sensitive detection systems that use low concentrations of antibodies and competing antigens typically demonstrate lower cross-reactivity and higher specificity. Conversely, assays requiring high concentrations of reagents tend to be less specific and show higher cross-reactivity. The format (competitive vs. sandwich), reagent concentrations, and reaction times all contribute to the observed cross-reactivity profile [7].

How can I computationally predict if my antibody will cross-react? You can perform a quick assessment using NCBI-BLAST for pair-wise sequence alignment between your immunogen sequence and the potential cross-reactive protein [9].

- >75% homology: Almost guaranteed cross-reactivity

- >60% homology: Strong likelihood of cross-reactivity, requires experimental verification Polyclonal antibodies generally have a higher propensity for cross-reactivity as they recognize multiple epitopes, whereas monoclonal antibodies, recognizing a single epitope, offer higher specificity [6] [9].

What are the key structural factors that make two epitopes cross-reactive? Two primary structural scenarios can lead to cross-reactivity [10]:

- Sequence Similarity: Epitopes with similar amino acid composition can produce similar interaction surfaces.

- Structural Mimicry: Sequences with no obvious similarity can exhibit nearly identical topographical and electrostatic charge distribution patterns, creating similar TCR interaction surfaces.

What are the practical consequences of cross-reactivity in research and diagnostics?

- Positive Implications: Enables broader pathogen protection; useful for developing cross-protective vaccines [11].

- Negative Implications: Causes false positives/negatives in immunoassays; may trigger autoimmune reactions when self and non-self epitopes are similar [12] [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unexpected Cross-Reactivity in Immunoassay

Unexpected cross-reactivity can lead to inaccurate data interpretation, particularly when detecting a specific analyte in the presence of structurally similar compounds.

Step-by-Step Investigation:

- Verify Assay Conditions: Transition your assay to conditions that use lower concentrations of antibodies and labeled antigens. This increases specificity by favoring only the highest-affinity interactions [7].

- Identify Potential Cross-Reactants: Compile a list of structurally similar compounds that might be present in your sample. Use database searches (e.g., PubChem) to find analogs and metabolites.

- Check Homology: Perform NCBI-BLAST alignment of your antibody's immunogen sequence against the proteome of your sample source to identify proteins with high sequence homology (>60%) [9].

- Test for Interference:

- Serial Dilution: A non-linear dilution curve suggests the presence of interference [13].

- Spike-and-Recovery: Add a known quantity of the target analyte and a suspected cross-reactant to the sample matrix. Poor recovery indicates interference [6].

- Use a Different Assay Format: If using a competitive format, try a sandwich format (if applicable), as it typically uses two antibodies and is less prone to certain cross-reactivities [13].

- Switch Antibody Type: If using a polyclonal antibody, consider switching to a monoclonal antibody for higher specificity to a single epitope [6] [9].

Problem: Determining Cross-Reactivity During Antibody Validation

Accurately characterizing an antibody's cross-reactivity profile is essential for ensuring experimental specificity.

Experimental Protocol:

- Objective: To quantify the ability of an antibody to distinguish between its target antigen and potential cross-reactants.

- Principle: A competitive immunoassay format is used to determine the concentration of cross-reactant required to displace the binding of a labeled reference analyte, compared to the unlabeled target itself.

| Step | Action | Key Parameter |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Preparation | Coat plates with the target antigen. | Use a consistent coating concentration. |

| 2. Competition | Pre-incubate a fixed antibody concentration with a serial dilution of either the target or cross-reactant. Then transfer to antigen-coated plates. | Use a wide concentration range (e.g., 0.1-1000 nM). |

| 3. Detection | Add detection antibody (species-specific) and substrate. Measure signal. | Signal is inversely proportional to competitor concentration. |

| 4. Analysis | Plot log(concentration) vs. response to generate inhibition curves. Calculate IC50 for target and cross-reactant. | IC50 is the concentration causing 50% signal inhibition. |

| 5. Calculation | Calculate cross-reactivity (CR):CR (%) = [IC50(target) / IC50(cross-reactant)] × 100% | A lower CR % indicates higher specificity [7]. |

Problem: Cross-Reactivity in Multiplexed Immunostaining

In experiments like immunohistochemistry or immunofluorescence, cross-reactivity can occur between secondary antibodies and off-target species immunoglobulins, leading to false-positive signals.

Solutions:

- Use Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibodies: These antibodies undergo an additional purification step to remove members that bind to off-target immunoglobulins, drastically reducing species cross-reactivity [9].

- Employ Directly Conjugated Primary Antibodies: By conjugating your primary antibody with a fluorophore or enzyme, you eliminate the need for secondary antibodies, thereby removing the source of this type of cross-reactivity [9].

- Select Antibodies from Different Hosts: Ensure that primary antibodies raised in different species are used when multiplexing. Then, use highly specific secondary antibodies that are raised against the immunoglobulin of one species and cross-adsorbed against others [9].

- Utilize Monoclonal Antibodies of Different Subtypes: When using multiple mouse monoclonal antibodies, select antibodies of different IgG subtypes (e.g., IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3). You can then use subtype-specific Nano-Secondary antibodies that show no cross-reactivity with other subclasses [9].

Data Presentation

Quantitative Guidance for Predicting Cross-Reactivity

The following table summarizes key quantitative thresholds and their implications for cross-reactivity based on sequence and structural analysis.

| Parameter | Threshold/Value | Implication for Cross-Reactivity | Source/Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Homology | >75% | Almost guaranteed cross-reactivity [9] | NCBI-BLAST alignment of immunogen sequence. |

| >60% | Strong likelihood; requires experimental verification [9] | NCBI-BLAST alignment of immunogen sequence. | |

| Assay Concentration | Low [Ab], [Ag*] | Lower cross-reactivity; higher specificity [7] | Competitive immunoassay format. |

| High [Ab], [Ag*] | Higher cross-reactivity; lower specificity [7] | Competitive immunoassay format. | |

| Performance Metric (Influenza) | AUC ~0.9 | Stable, high performance in predicting antigenic similarity [14] | CE-BLAST tool validation on HI data. |

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential materials and computational tools used to study, predict, and mitigate cross-reactivity.

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Description | Utility in Cross-Reactivity Context |

|---|---|---|

| Monoclonal Antibody (mAb) | Homologous IgG population recognizing a single epitope [9]. | Increases assay specificity; reduces cross-reactivity risk. |

| Polyclonal Antibody (pAb) | Heterogeneous mixture recognizing multiple epitopes [6]. | Higher sensitivity; may show desired cross-reactivity across species. |

| Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody | Secondary antibody purified to remove off-target species reactivity [9]. | Critical for multiplex staining to prevent false positives. |

| NCBI-BLAST | Tool for pair-wise sequence alignment [9]. | Quickly predicts potential cross-reactivity based on sequence homology. |

| CE-BLAST | Computational tool for calculating antigenic similarity based on 3D conformational epitopes [14]. | Predicts cross-reactivity for newly emerging pathogens independent of binding-assay data. |

| DockTope/CrossTope | In silico tools for modeling pMHC-I structures and comparing them to immunogenic targets [10]. | Identifies T-cell cross-reactivity by analyzing structural/physicochemical similarities. |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Calculating Cross-Reactivity in a Competitive ELISA

This protocol provides a standardized method to quantify the cross-reactivity of an antibody against structurally similar compounds.

1. Materials

- Target antigen and potential cross-reactants

- Validated primary antibody

- Coating buffer (e.g., carbonate-bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6)

- Blocking buffer (e.g., PBS with 1-5% BSA)

- Washing buffer (e.g., PBS with 0.05% Tween 20)

- Detection antibody (enzyme-conjugated, specific for the primary antibody host species)

- Enzyme substrate

- Stop solution

2. Procedure 1. Coating: Dilute the target antigen in coating buffer to a predetermined optimal concentration. Add to the wells of a microtiter plate and incubate overnight at 4°C. 2. Blocking: Wash the plate 3 times with washing buffer. Add blocking buffer to each well and incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature to block non-specific binding sites. 3. Competition: Prepare a fixed, constant concentration of primary antibody (determined from prior titration). In separate tubes, pre-incubate this antibody with a series of dilutions (e.g., from 0.1 nM to 1000 nM) of either: - The target antigen (standard curve) - Each potential cross-reactant - A negative control (buffer only) Incubate for a set time (e.g., 1-2 hours) at room temperature. 4. Binding: Transfer the pre-incubated mixtures to the washed, antigen-coated plate. Incubate to allow the free antibody to bind to the coated antigen. 5. Detection: Wash the plate. Add the enzyme-conjugated detection antibody and incubate. Wash again. Add the substrate solution and incubate for a defined period. 6. Stop and Read: Add stop solution and immediately measure the absorbance.

3. Data Analysis

1. Plot the mean absorbance (or % of maximum signal) for each concentration against the logarithm of the competitor concentration.

2. Fit a four-parameter logistic (4PL) curve to the data for the target and each cross-reactant.

3. From the curve, determine the IC50 value for each compound.

4. Calculate the percentage cross-reactivity for each cross-reactant using the formula:

Cross-Reactivity (%) = (IC50 of Target / IC50 of Cross-Reactant) × 100% [7].

Workflow: An Integrated Structural Approach to Troubleshoot T-Cell Cross-Reactivity

This workflow diagram outlines a computational and experimental pipeline for investigating T-cell epitope cross-reactivity, which is crucial for vaccine design and understanding immune responses.

Visualization of Concepts

Epitope Recognition and Cross-Reactivity Scenarios

This diagram illustrates the fundamental concepts of epitope recognition by antibodies and the two main scenarios that lead to cross-reactivity: shared linear sequence motifs and conformational similarity.

FAQ: Understanding Immunoassay Interference

What are the main types of interference in immunoassays? Interferences in immunoassays can be broadly categorized into two groups: those that alter the measurable concentration of the analyte in the sample and those that alter antibody binding [12]. The first group includes factors like hormone-binding proteins, autoanalyte antibodies, and pre-analytical errors. The second group includes heterophile antibodies, human anti-animal antibodies (HAAAs), rheumatoid factors, and the high-dose hook effect [12] [15].

How does cross-reactivity differ from other interferences? Cross-reactivity is a specific and often predictable type of interference where substances structurally similar to the target analyte compete for the antibody-binding site [8]. This is distinct from non-specific interferences like heterophile antibodies, which can bind to reagent antibodies regardless of the analyte's structure [12]. Cross-reactivity is a particular issue in competitive immunoassays and with drug metabolites [16] [15].

Why is cross-reactivity a significant problem in Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM)? In TDM, metabolite cross-reactivity can lead to significant overestimation or underestimation of drug levels, potentially resulting in incorrect dosage adjustments. For example [16]:

- Digoxin immunoassays are affected by endogenous digoxin-like immunoreactive substances and various drugs and herbal supplements.

- Carbamazepine is metabolized to an epoxide, and the cross-reactivity of this metabolite in immunoassays can range from 0% to 94%.

- Immunosuppressants like cyclosporin A are subject to significant metabolite interference, leading to results up to 174% higher than reference methods [12].

What are some common sources of pre-analytical errors? Pre-analytical errors arise from issues in sample collection, storage, or processing [17]. These include:

- Haemolysis: The breakdown of red blood cells can release interferents.

- Incorrect Anticoagulants: The use of EDTA, citrate, or fluoride can chelate ions necessary for assay chemistry or inhibit enzyme labels [12] [17].

- Sample Contamination: Components from blood collection tubes (e.g., stoppers, separator gels) can leach into specimens or adsorb analytes [17].

- Delay in Processing or Incorrect Storage: This can lead to analyte degradation or generation of interfering substances [17].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Addressing Interference

The following table summarizes key interference sources, their effects, and potential solutions.

| Interference Source | Effect on Assay | Troubleshooting & Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolite Cross-reactivity [16] [15] | Falsely elevated or decreased reported drug concentration. | Use a more specific method (e.g., LC-MS/MS); verify results with a different immunoassay platform; be aware of metabolite profiles in specific patient populations. |

| Heterophile Antibodies & HAAAs [12] [15] | Primarily false-positive results in sandwich immunoassays; can also cause false negatives. | Use blocking reagents in the assay; re-analyze with a heterophile antibody blocking tube; dilute the sample to check for non-linearity; use an alternative assay format. |

| Endogenous Binding Proteins (e.g., cortisol-binding globulin) [12] | Alters the measurable free (active) concentration of the analyte. | Use assays that include steps to denature or block binding proteins; measure free analyte if clinically relevant. |

| Pre-analytical Variations [12] [17] | Variable and unpredictable effects on analyte stability and detection. | Follow standardized collection and storage protocols; ensure correct fill volumes; centrifuge samples to remove particulates and lipids [18]. |

| Concomitant Medications (structurally similar) [19] | False-positive results in drug screens (e.g., amphetamine, methadone assays). | Confirm all presumptive positive screening results with a specific method like GC-MS or LC-MS/MS. |

| Lipemia, Icterus, Hemolysis [12] | Can interfere with nephelometry/turbidimetry or physically quench signals. | Clarify samples by high-speed centrifugation prior to analysis [18]. |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Interference

Protocol 1: Assessing Cross-Reactivity Using a Spiked Specimen

This methodology is commonly used to validate assay specificity and is detailed in commercial assay package inserts [8].

- Preparation of Spiked Samples: Obtain a drug-free biological matrix (e.g., pooled human serum or plasma). Prepare a concentrated stock solution of the potential cross-reactant. Spike the matrix with a known concentration of the cross-reactant. A common approach is to add 100 µg/dL of the cross-reactant to the specimen [8].

- Measurement: Assay both the unspiked (baseline) and spiked specimens using the immunoassay under investigation.

- Calculation of Cross-Reactivity: Calculate the percentage cross-reactivity using the formula: Cross-reactivity (%) = (Measured concentration in spiked sample – Baseline concentration) / Concentration of cross-reactant added × 100% [8]. Interpretation: A high percentage indicates significant cross-reactivity, which may lead to clinically relevant false positives.

Protocol 2: A Data-Driven Approach for Discovering Novel Cross-Reactivities

This systematic protocol, based on analysis of Electronic Health Record (EHR) data, can be used to discover previously unknown interferents [19].

- Data Assembly: Extract a large dataset of immunoassay results linked to documented medication exposures for the corresponding patients. The dataset should include both negative and presumptive positive results that were later confirmed as false positives by a reference method.

- Statistical Analysis: For each assay-ingredient pair, use logistic regression to quantify the association between previous exposure to a drug and a false-positive screen result. The outcome is expressed as an odds ratio, where a high odds ratio suggests the ingredient is a potential cross-reactant [19].

- Experimental Validation: Select compounds with the strongest statistical associations. Spike the candidate cross-reactant into drug-free urine or serum and test the spiked samples on the immunoassay to confirm the interference [19].

Visualizing Interference Mechanisms and Workflows

Interference Mechanisms in Immunoassays

Workflow for Systematic Interference Investigation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions for troubleshooting cross-reactivity.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|

| Heterophile Blocking Reagents | Contains inert animal antibody fragments that bind to heterophile antibodies and HAAAs, preventing them from interfering with the assay antibodies [12]. |

| Stripped / Matrix-Matched Serum | Analyte-free biological matrix used as a baseline control and for preparing spiked samples in cross-reactivity and recovery experiments [8]. |

| Monoclonal vs. Polyclonal Antibodies | Monoclonal antibodies offer high specificity for a single epitope, while polyclonal antibodies may be more sensitive but can show broader cross-reactivity; choice depends on the desired selectivity [7]. |

| LC-MS/MS System | A reference method that separates molecules by mass, providing high specificity to confirm immunoassay results and definitively identify cross-reacting substances [16] [19]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Used to clean up complex samples (e.g., urine, serum) by removing salts, lipids, and other potential interferents prior to analysis, reducing matrix effects. |

This technical support center provides a targeted resource for researchers troubleshooting cross-reactivity in immunoassays. The following guides and FAQs are framed within the context of a broader thesis on mitigating these issues in pharmaceutical and clinical research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is cross-reactivity and why is it a problem?

Cross-reactivity occurs when an antibody in an immunoassay binds not only to its target analyte but also to structurally similar compounds it was not designed to detect [20]. Think of it like a lock (antibody) that can be opened by several similar, but not identical, keys (analytes) [20]. This is problematic because it can lead to false-positive results or inflated quantitative readings, compromising data integrity and leading to incorrect conclusions in both clinical diagnostics and drug development [19] [21]. For example, in urine drug screening, cross-reactivity from medications can suggest illicit drug use where there is none, potentially damaging the patient-provider relationship [19] [20].

Does a positive screening result always mean the target is present?

No. A presumptively positive result on an immunoassay screen should be interpreted with caution, as it may be caused by a cross-reactive substance [19] [20]. For example, the over-the-counter decongestant pseudoephedrine can cause a positive amphetamine screen [20]. It is a standard best practice to confirm presumptive positive results with a more specific technique, such as LC-MS/MS or GC-MS [19] [20].

Is cross-reactivity an inherent property of the antibodies alone?

Not exclusively. Recent research demonstrates that cross-reactivity is not a fixed parameter determined solely by the antibodies used [7]. The same antibody can exhibit different cross-reactivity profiles depending on the assay format (e.g., ELISA vs. FPIA), the concentration of reagents, and whether the assay is run under kinetic or equilibrium conditions [7]. Shifting to assay conditions that require lower concentrations of reagents and markers can reduce cross-reactivity, making the assay more specific [7].

Can the host species of a sample influence cross-reactivity?

Yes. Studies on serological assays have shown that absolute and relative antibody titers can vary systematically across different host species, even when infected with the identical pathogen strain [22] [23]. This means that the same infecting serovar can produce different cross-reactivity profiles in different host species, and the highest antibody titer is not always a reliable indicator of the infecting agent [23].

Quantitative Data on Common Cross-Reactants

The following table summarizes documented and potential cross-reactivities that can lead to false-positive or inflated results. Data is compiled from systematic analyses of electronic health records and subsequent experimental validation [19].

Table 1: Documented and Potential Cross-Reactivities in Urine Drug Screening Immunoassays

| Target Assay | Cross-Reactive Compound | Impact / Outcome | Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amphetamines | Pseudoephedrine | False Positive | Known Cross-Reactivity [20] |

| Amphetamines | Other Unspecified Medications | False Positive | Newly Discovered [19] |

| Buprenorphine | Unspecified Medications | False Positive | Newly Discovered [19] |

| Cannabinoids (THC) | Unspecified Medications | False Positive | Newly Discovered [19] |

| Methadone | Unspecified Medications | False Positive | Newly Discovered [19] |

| Opiates | Poppy Seeds | False Positive | Known Interference [20] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Mitigating Cross-Reactivity

Problem: Suspected cross-reactivity is causing inconsistent or unexpected positive results.

Step 1: Review Medication and Exposure History

- Action: Compile a complete list of the donor's or subject's prescriptions, over-the-counter medications, and supplements [20].

- Rationale: Many cross-reactivities are caused by legitimate medications with structures similar to the target illicit drug [19] [20].

Step 2: Implement Confirmatory Testing

- Action: Send the sample for confirmatory testing using a highly specific method like GC-MS or LC-MS/MS [19] [20].

- Rationale: These techniques can distinguish between the target analyte and structurally similar cross-reactants, providing a definitive result [20].

Step 3: Optimize Your Immunoassay Protocol

- Action: Consider adjusting your assay conditions to enhance specificity.

- Vary Reagent Concentrations: Using lower concentrations of antibodies and competing antigens can reduce cross-reactivity [7].

- Explore Heterologous Formats: Using a different antigen derivative in the assay than the one used for immunization can narrow the spectrum of antibody selectivity [7].

- Utilize Antibody Fragments: Using F(ab) antibody fragments instead of full IgG can help avoid interference from endogenous factors like rheumatoid factor and complement [21].

- Rationale: Cross-reactivity is modulated by assay conditions, not just antibody affinity, offering a path to improve specificity without developing new reagents [7].

Step 4: Use Blocking Agents

- Action: For specific interferents, add blocking agents to the sample or diluent.

- Rheumatoid Factor (RF): Add heat-aggregated IgG or use 2-mercaptoethanol to degrade RF [21].

- Complement: Use EDTA to chelate calcium and magnesium, preventing complement activation [21].

- Heterophilic Antibodies: Add an excess of animal IgG (e.g., mouse IgG) to the sample to block these antibodies [21].

- Rationale: These agents bind to or inactivate common interfering substances before they can interfere with the assay antibodies [21].

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Discovery of Cross-Reactive Substances

This methodology, adapted from a large-scale study using Electronic Health Record (EHR) data, provides a framework for proactively identifying unknown cross-reactants [19].

Objective: To systematically identify and validate previously unknown cross-reactive substances for a given immunoassay.

Materials:

- EHR dataset linked to historical immunoassay results (e.g., 698,651 results) [19].

- Data on previous medication exposures for tested individuals [19].

- Drug-free urine for spiking experiments [19].

- Suspect cross-reactive compounds and metabolites [19].

- Target immunoassay platform and confirmatory LC-MS/MS or GC-MS equipment [19].

Procedure:

Data Linkage and Analysis:

- Link each historical immunoassay result to all documented drug exposures for that individual in the 1-30 days prior to testing [19].

- Use statistical models (e.g., Firth's logistic regression) to quantify the association between exposure to a specific ingredient and the odds of a false-positive screen. An odds ratio (OR) greater than 1 suggests potential cross-reactivity [19].

- Prioritize compounds with the strongest statistical associations for experimental testing [19].

Experimental Validation:

- Spike drug-free urine with the suspected cross-reactive compound (or its metabolites) at physiologically relevant concentrations [19].

- Run the spiked sample on the target immunoassay.

- A presumptive positive result on the immunoassay, followed by a negative confirmation on the specific LC-MS/MS for the target drug, validates the substance as a cross-reactant [19].

The workflow below visualizes this systematic approach:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Resources for Investigating Cross-Reactivity

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| F(ab) Antibody Fragments | Replaces full IgG to avoid interference from RF, complement, and heterophilic antibodies [21]. | Increases specificity but may require custom preparation. |

| Animal IgG (e.g., Mouse IgG) | Added to sample as a blocking agent to neutralize heterophilic antibodies [21]. | Concentration is critical; insufficient amount will be ineffective [21]. |

| EDTA | Chelating agent used as an anticoagulant to inhibit complement interference [21]. | A simple and effective step for specific interferents. |

| Heterologous Assay Format | Uses a different antigen derivative in the assay than was used for immunization [7]. | Can narrow selectivity but requires additional chemical synthesis [7]. |

| Computational Tools (e.g., ARDitox) | AI-driven platform to predict off-target and cross-reactive epitopes for T-cell receptors, supporting safer immunotherapy design [24]. | Useful for early-stage risk assessment in cell therapy development. |

| Normalization Algorithms (for Luminex) | Computational methods (e.g., orthogonal regression, GAM) to correct for background fluorescence and machine drift, reducing false signals [25]. | Enhances assay reproducibility and minimizes technical noise. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are the most common causes of interference in steroid hormone immunoassays? Interference in steroid hormone immunoassays primarily arises from:

- Cross-reactivity: Structurally similar compounds, such as endogenous steroid precursors, metabolites, or synthetic drugs (e.g., prednisolone), are mistakenly recognized by the assay antibodies [26] [27].

- Endogenous Antibodies: Human anti-animal antibodies (HAAA) or heterophile antibodies can bind to assay reagents, causing false elevation or suppression of results [26] [12] [28].

- Biotin: High circulating concentrations of biotin from supplement intake can interfere with assays that use biotin-streptavidin technology [26] [28].

- The High-Dose Hook Effect: In sandwich immunoassays, extremely high analyte concentrations can saturate both capture and detection antibodies, leading to a falsely low reported result [26] [28].

- Sample Matrix Effects: Abnormal levels of lipids, bilirubin, or haemoglobin can interfere with some assay detection systems [12] [28].

2. How can I recognize potential interference in my immunoassay results? Interference should be suspected when:

- The laboratory result is clinically inconsistent with the patient's presentation or previous history [26] [28].

- Results from different immunoassay platforms for the same sample are discordant [29] [30].

- There is an implausible hormone profile or a lack of correlation between related biomarkers [26].

- A result changes dramatically upon sample dilution in a non-linear fashion, which may indicate the hook effect [28].

3. What practical steps can I take to investigate suspected interference? If you suspect interference, the following investigative steps are recommended:

- Consult the Package Insert: Review the cross-reactivity data provided by the assay manufacturer for known interfering substances [27].

- Perform Serial Dilutions: A lack of linearity upon dilution can confirm the presence of an interferent [28] [6].

- Use a Blocking Reagent: Pre-incubating the sample with commercial blocking agents can neutralize heterophile antibody or HAAA interference [12].

- Re-assay with an Alternative Method: The most definitive approach is to re-measure the analyte using a different immunoassay platform or a reference method like liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), which is less susceptible to such interferences [29] [27] [30].

4. When should I consider using mass spectrometry instead of immunoassay? Mass spectrometry (e.g., LC-MS/MS) is the preferred method in scenarios requiring high specificity and sensitivity, such as:

- Measuring steroids in pediatric endocrinology, where hormone concentrations are very low [29] [30].

- Diagnosing and monitoring complex endocrine disorders like congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), where multiple structurally similar steroids need to be quantified accurately [30].

- Verifying unexpected or clinically implausible results obtained from an immunoassay [29] [27].

- Quantifying vitamin D metabolites, as LC-MS/MS minimizes cross-reactivity issues common in immunoassays [30].

Troubleshooting Guide: A Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol for Investigating Cross-Reactivity

This protocol outlines a systematic approach to confirm and characterize cross-reactivity in a steroid hormone immunoassay, based on established guidelines [27].

Objective: To determine if a specific compound (the "cross-reactant") interferes with the accurate measurement of the target steroid hormone.

Materials:

- The immunoassay platform and reagents under investigation.

- Pooled normal human serum or plasma (as an analyte-free matrix).

- Purified target analyte (the steroid of interest).

- Purified cross-reactive compound.

- Appropriate solvents for dissolving standards (ensure they do not interfere with the assay).

Experimental Workflow:

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for the experimental protocol.

Methodology:

- Preparation of Spiked Samples:

- Target Analyte Calibration Curve: Prepare a series of calibration standards by spiking the analyte-free matrix with known concentrations of the purified target analyte. This establishes the standard dose-response curve.

- Cross-reactant Samples: Prepare a separate series of samples by spiking the analyte-free matrix with a range of concentrations of the purified cross-reactive compound.

Immunoassay Execution:

- Run all spiked samples (both the target analyte and cross-reactant series) in the same immunoassay run to minimize inter-assay variability.

- Ensure each sample is analyzed in duplicate or triplicate for precision.

Data Analysis and Calculation:

- For the cross-reactant sample that produces an assay signal closest to the 50% inhibition point (IC₅₀) on the target analyte's calibration curve, calculate the percent cross-reactivity using the formula below [7] [27]:

% Cross-Reactivity = (IC₅₀ of Target Analyte / IC₅₀ of Cross-Reactant) × 100%

- IC₅₀ of Target Analyte: The concentration of the target analyte that reduces the assay signal by 50%.

- IC₅₀ of Cross-Reactant: The concentration of the cross-reactant that reduces the assay signal by 50%.

Interpretation:

- Strong Cross-Reactivity: ≥ 5% - High likelihood of clinical significance.

- Weak Cross-Reactivity: 0.5% - 4.9% - Clinical significance depends on the concentration of the interferent in patient samples.

- Very Weak/Negligible: < 0.5% - Unlikely to be clinically significant [27].

Data Presentation: Clinically Significant Cross-Reactivity Examples

The tables below summarize experimental data for compounds with known clinically significant cross-reactivity in common steroid hormone immunoassays [27].

Table 1: Cross-Reactivity in a Cortisol Immunoassay

| Compound | % Cross-Reactivity | Context for Clinical Significance | Reported Plasma Concentration (ng/mL) | Estimated False Cortisol (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prednisolone | 69% | Glucocorticoid therapy | 100 - 1,500 [27] | 69 - 1,035 |

| 6-Methylprednisolone | 41% | Glucocorticoid therapy | 10 - 300 [27] | 4 - 123 |

| 21-Deoxycortisol | 11% | 21-Hydroxylase Deficiency | 2 - 60 [27] | 0.2 - 6.6 |

| 11-Deoxycortisol | 2.2% | 11β-Hydroxylase Deficiency / Metyrapone test | 50 - 500 [27] | 1.1 - 11 |

Table 2: Cross-Reactivity in a Testosterone Immunoassay

| Compound | % Cross-Reactivity | Context for Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Methyltestosterone | 35% | Anabolic steroid use |

| Danazol | 13% | Treatment of endometriosis |

| Norethindrone | 2.1% | Progestin therapy (may impact female testosterone measurements) |

| DHEA Sulfate | 0.6% | Endogenous androgenic precursor (may be significant at high concentrations) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key materials and methodologies essential for developing and troubleshooting steroid hormone assays.

| Item | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Monoclonal Antibodies | Provide high specificity by recognizing a single epitope; ideal for capture antibody in sandwich assays to minimize cross-reactivity [6]. | Lower sensitivity compared to polyclonals as only one antibody binds per antigen [6]. |

| Polyclonal Antibodies | Recognize multiple epitopes; often used as detection antibodies to increase assay sensitivity [6]. | More prone to cross-reactivity due to a broader range of epitope recognition [6]. |

| Blocking Reagents | Neutralize interfering substances like heterophile antibodies and HAAA in patient samples prior to assay [12]. | A critical step for investigating and mitigating antibody-mediated interference. |

| LC-MS/MS | A highly specific reference method that separates and detects steroids based on mass, virtually eliminating antibody-based cross-reactivity [29] [30]. | Overcomes fundamental limitations of immunoassays; recommended for low-concentration steroids and complex diagnoses [30]. |

| Automated Platform (e.g., Gyrolab) | Uses microfluidics and flow-through technology to minimize reagent/sample contact time, reducing matrix interference and reagent consumption [6]. | Useful for precious samples and for improving assay robustness during development. |

Methodological Approaches for Detecting and Leveraging Cross-Reactivity

What is Cross-Reactivity? In immunoassays, cross-reactivity occurs when an antibody binds to an analyte that is structurally similar to, but different from, its target antigen. This binding can lead to false-positive results or an overestimation of the target analyte's concentration, compromising the accuracy and reliability of your data [12] [6]. In drug testing, for example, the over-the-counter decongestant pseudoephedrine can cause a positive amphetamine screen due to its similar molecular structure [20]. Understanding and quantifying cross-reactivity is therefore not merely an academic exercise but a critical component of assay validation.

The IC50 Method Explained The IC50 method is the most widely accepted approach for quantifying cross-reactivity in competitive immunoassay formats. Cross-reactivity is calculated by comparing the concentration of the target analyte required to produce a 50% reduction in the assay signal to the concentration of a cross-reactant needed to produce the same effect [7] [19]. The standard formula for calculating percent cross-reactivity (%CR) is: %CR = [IC50 (Target Analyte) / IC50 (Cross-Reactant)] × 100% [7] An IC50 value represents the inhibitory concentration of a compound that reduces a given biological or biochemical process by half [31]. In the context of a competitive immunoassay, this "process" is the binding of a marker (like a labeled antigen) to the antibody, which is inhibited by the presence of the free analyte.

Step-by-Step Calculation Protocol

Experimental Workflow for IC50 Determination

The following diagram outlines the complete experimental workflow for determining IC50 values and calculating percent cross-reactivity.

Detailed Experimental Methodology

Materials and Reagents:

- Target analyte and cross-reactant compounds of known purity

- Specific antibody (monoclonal or polyclonal)

- Labeled antigen (e.g., enzyme-conjugated, fluorescent)

- Assay buffers and substrate (if applicable)

- Microplates and laboratory equipment for liquid handling and signal detection

Procedure:

- Prepare Serial Dilutions: Create a series of dilutions for both the target analyte and the cross-reactant. A wide concentration range (e.g., spanning several orders of magnitude) is crucial for an accurate curve fit.

- Run Competitive Immunoassay: For each concentration, incubate the sample (containing the target or cross-reactant) with a fixed concentration of antibody and labeled antigen. Perform this in replicate (e.g., n=3) to ensure statistical robustness.

- Measure Signal: After incubation and washing (if required), measure the assay signal (e.g., absorbance, fluorescence, luminescence) for each well.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the average signal for each concentration.

- Normalize the data, expressing the signal as a percentage of the maximum signal (typically from the zero-concentration control).

- Plot the normalized signal (%) against the logarithm of the concentration.

- Fit the data to a 4-parameter logistic (4PL) curve. The equation is: Y = Bottom + (Top - Bottom) / (1 + (X/IC50)^HillSlope) where Y is the response, X is the concentration, "Top" and "Bottom" are the plateaus, and the HillSlope describes the steepness of the curve.

- From the fitted curve, determine the IC50 value for both the target and the cross-reactant.

- Calculate % Cross-Reactivity: Apply the standard formula using the obtained IC50 values.

Example Calculation

Assume you have determined the following IC50 values for your target analyte and a potential cross-reactant:

- IC50 (Target Analyte): 5.0 nM

- IC50 (Cross-Reactant): 250.0 nM

The percent cross-reactivity is calculated as: %CR = (5.0 nM / 250.0 nM) × 100% = 2.0%

This result indicates that the cross-reactant is two orders of magnitude less potent than the target analyte in displacing the labeled antigen from the antibody.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The reliability of your cross-reactivity data is fundamentally dependent on the quality and appropriateness of your research reagents. The table below details key materials and their functions.

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Cross-Reactivity Studies

| Reagent | Function & Importance | Selection Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Antibody | The primary binding agent; its affinity and specificity define the assay's potential for cross-reactivity [6]. | Monoclonal antibodies offer higher specificity to a single epitope. Polyclonal antibodies can provide higher sensitivity but may increase cross-reactivity risk [6]. |

| Labeled Antigen | Competes with the free analyte for antibody binding sites; generates the detectable signal [7]. | The choice of label (enzyme, fluorescent, etc.) dictates the detection method. Using a "heterologous" label (different from the immunogen) can sometimes improve specificity [7]. |

| Target Analyte & Cross-Reactants | The molecules being tested; their purity and structural integrity are critical for accurate results. | Source compounds from reputable suppliers. Include known metabolites and structurally similar compounds likely to be present in sample matrices. |

| Assay Buffer | Provides the chemical environment (pH, ionic strength) for the antigen-antibody reaction. | Buffer composition can influence antibody affinity and specificity. Optimize to minimize non-specific binding [12]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why did I get a different cross-reactivity value when I changed my assay format (e.g., from ELISA to FPIA)? Cross-reactivity is not an absolute, fixed parameter of an antibody. It is highly dependent on assay conditions. A key factor is the concentration of immunoreagents used. Assays with sensitive detection that use low concentrations of antibodies and labeled antigens are typically more specific and show lower cross-reactivity. Formats requiring higher reagent concentrations can appear less specific [7]. Even within the same format, changing the ratio of reagents or the incubation time (shifting from kinetic to equilibrium conditions) can alter the measured cross-reactivity [7].

Q2: My assay shows high cross-reactivity with an unexpected compound. What should I do? First, verify the result by repeating the experiment. If confirmed, systematically investigate the cause:

- Check Structural Similarity: Analyze the molecular structures of your target and the unexpected cross-reactant. Even seemingly unrelated compounds can share a common sub-structure or epitope that the antibody recognizes [32].

- Review Reagent Specificity: The primary antibody may be promiscuous. A study found that 95% of monoclonal antibodies tested bound to non-target proteins, highlighting the pervasiveness of this issue [6]. Consider screening for a more specific antibody.

- Assay Conditions: Investigate if factors like pH, ionic strength, or matrix components are contributing to the interference [12].

Q3: Is there a way to make my existing immunoassay more specific without developing new antibodies? Yes, you can modulate selectivity by optimizing assay conditions. As demonstrated in research on sulfonamide and fluoroquinolone detection, shifting to lower concentrations of reagents can reduce cross-reactivities by up to five-fold, making the assay more specific [7]. Other strategies include using a heterologous assay format (where the labeled antigen is structurally different from the one used for immunization) or adding blocking agents to the matrix to reduce non-specific interference [7] [6].

Q4: How do I interpret a cross-reactivity value of 0.5%? A cross-reactivity of 0.5% means that the cross-reactant is 200 times less potent than the target analyte in your assay. Specifically, it would require 200 times more of the cross-reactant to produce the same 50% signal inhibition as the target analyte. This level of cross-reactivity is generally considered low, but its acceptability depends on the expected concentration of the cross-reactant in your real samples and the clinical or analytical decision limits of your assay.

Q5: Why is it important to use the IC50 point for calculation instead of another point on the curve? The IC50 point lies on the linear, steepest part of the sigmoidal dose-response curve. This region is most sensitive to changes in concentration and is generally the most precise and reproducible for comparative measurements. Using points at the extremes of the curve (e.g., IC20 or IC80), where the slope is shallow, can lead to greater variability and less reliable cross-reactivity estimates [7] [19].

Key Differences at a Glance

The choice between monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies is fundamental to experimental design, directly impacting specificity, sensitivity, and the potential for cross-reactivity. The table below summarizes their core characteristics:

| Feature | Monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs) | Polyclonal Antibodies (pAbs) |

|---|---|---|

| Origin & Composition | Derived from a single B-cell clone; homogeneous population [33] [34] | Derived from multiple B-cell clones; heterogeneous mixture of antibodies [33] [35] |

| Specificity | Bind to a single, specific epitope; high specificity [33] [36] | Recognize multiple epitopes on the same antigen; broader specificity [33] [35] |

| Cross-Reactivity Potential | Lower inherent risk due to single epitope recognition [35] [6] | Higher inherent risk as different epitopes on similar antigens may be recognized [35] [37] |

| Sensitivity | Can be more sensitive for protein level quantification; lower background noise [35] [36] | High sensitivity for detecting low-quantity proteins; quicker antigen capture [35] |

| Production | Time-consuming (∼6+ months), complex, and costly hybridoma technology [33] [36] | Relatively quick (∼3-4 months), simple, and cost-effective [33] [35] |

| Batch-to-Batch Variability | Low; high reproducibility and unlimited supply from hybridomas [33] [34] | High; requires careful validation for reproducible results [35] [36] |

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

How do I proactively check if an antibody will cross-react?

A: Cross-reactivity occurs when an antibody binds to non-target antigens that share structural similarities with the intended target [37]. Proactive checks are crucial for assay validation.

Step 1: Immunogen Sequence Analysis The most straightforward initial check is to perform a pair-wise sequence alignment using the NCBI BLAST tool. This assesses the percentage homology between the antibody's immunogen sequence and related proteins or the protein from your model organism [37].

- Action: Locate the immunogen sequence for your antibody (usually found in the product datasheet) and paste it into the NCBI BLAST "query sequence" box.

- Interpretation: Homology above 75% almost guarantees cross-reactivity. A homology over 60% indicates a strong likelihood and requires experimental verification [37].

Step 2: Antibody Type Consideration

- Polyclonal Antibodies: Have a higher inherent risk of cross-reactivity because they recognize multiple epitopes. If cross-reactivity is a persistent issue, consider switching to a monoclonal antibody [35] [37].

- Monoclonal Antibodies: Offer higher specificity but are not infallible. A single paratope can sometimes bind to unrelated epitopes (mimotopes) that share complementary shape and charge [38].

Step 3: Experimental Validation Always validate antibody specificity within your specific assay system. Key methods include:

- Using a knockout cell line or tissue to confirm the absence of signal.

- Pre-adsorption controls, where the antibody is incubated with an excess of the purified target antigen before application, should abolish the signal.

- Western Blotting to ensure the antibody detects a single band at the expected molecular weight.

My immunoassay shows high background noise. Could antibody choice be the cause?

A: Yes, antibody choice is a primary factor. The solution depends on the nature of the noise.

Scenario: High Background from Non-Specific Binding

- Problem: Polyclonal antibodies, due to their heterogeneity, can contain subpopulations that bind non-specifically to components in the sample matrix [35].

- Solution:

- Use Monoclonal Antibodies: Their uniform structure and single-epitope specificity make them superior for minimizing background noise [35] [36].

- Affinity-Purify Polyclonals: If you must use a polyclonal, ensure it is affinity-purified against the specific antigen to remove non-specific antibodies [35].

- Optimize Blocking and Dilution: Increase the concentration of blocking agents (e.g., BSA, non-fat milk) and titrate the antibody to find the optimal signal-to-noise ratio [39].

Scenario: Cross-Reactivity with Related Proteins

- Problem: The antibody is detecting homologous proteins or protein isoforms present in the sample [12] [6].

- Solution:

- Switch Antibody Type: A monoclonal antibody with high specificity for a unique epitope is the most direct solution [6].

- Use a "Heterologous" Assay Format: In competitive immunoassays, using a modified antigen (heterologous) that differs from the one used for immunization can narrow the spectrum of selectivity by ensuring only a subset of high-affinity antibodies are involved in the detection [7].

- Try a Different Assay Format: Shifting to an assay format that uses lower reagent concentrations (e.g., miniaturized, flow-through systems) can favor high-affinity, specific interactions and reduce low-affinity cross-reactivity [7] [6].

I need to detect a low-abundance target. Which antibody offers the best sensitivity?

A: For maximum sensitivity, polyclonal antibodies are often the preferred first choice.

- Reason: Because a polyclonal antibody mixture targets multiple epitopes on the same antigen, more antibody molecules can bind to a single target protein. This multi-valent binding amplifies the detection signal, making it highly effective for capturing low-quantity proteins [35].

- Best Applications: This makes polyclonal antibodies excellent as capture antibodies in sandwich ELISA, for immunoprecipitation (IP), and for detecting native proteins where epitopes may be partially masked [35] [36].

- Trade-off: The enhanced sensitivity comes with a potentially higher risk of cross-reactivity, which must be managed through careful validation and controls [35].

How can I minimize cross-reactivity in multiplex immunoassays?

A: Multiplex assays require careful planning to prevent secondary antibodies from cross-reacting with primary antibodies from different species.

Strategy 1: Use Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibodies

- Action: Always select secondary antibodies that have been cross-adsorbed or highly cross-adsorbed against the immunoglobulins of other species present in your experiment.

- Function: These antibodies undergo an additional purification step to remove contaminants that could bind to off-target immunoglobulins, drastically reducing species cross-reactivity [37].

Strategy 2: Use Monoclonal Antibodies of Different Subtypes

- Action: When multiplexing with mouse primary antibodies, use monoclonals of different IgG subtypes (e.g., IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b).

- Function: You can then use subtype-specific secondary antibodies (e.g., anti-mouse IgG1, anti-mouse IgG2b) that will only bind to their designated primary antibody, eliminating cross-talk [37].

Strategy 3: Use Directly Conjugated Primaries

- Action: Label your primary antibodies directly with fluorophores or enzymes.

- Function: This eliminates the need for secondary antibodies altogether, thereby completely avoiding secondary antibody-mediated cross-reactivity [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and strategies for troubleshooting antibody-related issues.

| Reagent / Strategy | Function in Troubleshooting Cross-Reactivity & Improving Specificity |

|---|---|

| Monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs) | Provides high specificity to a single epitope; ideal for reducing background noise and minimizing cross-reactivity with structurally similar antigens [35] [6] [36]. |

| Affinity-Purified Polyclonal Antibodies | Reduces non-specific binding in polyclonal preparations by isolating only the antibodies that bind specifically to the target antigen [35]. |

| Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibodies | Critical for multiplexing; removes antibodies that react with immunoglobulins from other species, preventing off-target signal in complex experiments [37]. |

| Recombinant Antibodies | Defined amino acid sequence ensures no batch-to-batch variability and superior reproducibility. Their genetic nature allows for humanization and engineering for enhanced specificity [35] [36]. |

| "Heterologous" Immunoassay | A competitive assay format that uses a modified antigen to narrow antibody selectivity. This is a powerful method to increase specificity without developing new antibodies [7]. |

| Blocking Buffers (e.g., ChonBlock) | Specialized buffers designed to prevent non-specific binding interactions, thereby reducing background signal and false positives in assays like ELISA [39]. |

Experimental Protocol: Modifying Assay Conditions to Reduce Cross-Reactivity

This protocol is based on research demonstrating that cross-reactivity is not an immutable property of an antibody but can be modulated by the assay format and conditions [7].

Objective: To lower the cross-reactivity of an existing immunoassay by optimizing reagent concentrations and reaction times.

Principle: Immunoassays implemented with sensitive detection and low concentrations of reagents are characterized by lower cross-reactivities and higher specificity. Favoring kinetic over equilibrium conditions can further reduce low-affinity, cross-reactive binding [7].

Materials:

- Your current antibody and cross-reactive antigen.

- Components for your immunoassay (e.g., buffers, plates, detection system).

- Microplate reader or other appropriate detector.

Method:

- Titrate Reagent Concentrations: Set up your standard competitive immunoassay but with a significant (e.g., 5-10 fold) reduction in the concentration of both the antibody and the competing antigen (e.g., enzyme-conjugated hapten).

- Compare Cross-Reactivity: Run standard curves for both your target analyte and the main cross-reactant under the new (low-concentration) and old (standard-concentration) conditions.

- Calculate Cross-Reactivity (CR): For both conditions, calculate the CR using the formula:

CR (%) = [IC₅₀ (Target Analyte) / IC₅₀ (Cross-Reactant)] × 100%where IC₅₀ is the concentration causing 50% inhibition of the maximum signal [7]. - Shorten Incubation Times (Kinetic Mode): To shift the assay from equilibrium to kinetic mode, substantially reduce the incubation times for the antigen-antibody reaction. This favors the formation of high-affinity specific complexes over slower, low-affinity cross-reactive binding.

- Repeat Comparison: Measure the IC₅₀ values for the target and cross-reactant under these shortened incubation times and re-calculate the CR.

Expected Outcome: The low-concentration and kinetic-mode assays should show a lower cross-reactivity percentage (i.e., better differentiation between the target and cross-reactant) compared to the standard assay format, resulting in a more specific immunoassay [7].

Decision Workflow for Antibody Selection

The following diagram visualizes the key questions to guide your initial choice between monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies.

Immunoassays are powerful tools for quantifying molecules of biological interest, leveraging the specific binding between an antibody and its target analyte. The choice of assay format is a critical decision that directly impacts key performance parameters, including sensitivity, specificity, and perhaps most importantly for many applications, cross-reactivity. Cross-reactivity occurs when an antibody binds to structurally similar molecules other than the intended target, potentially leading to false positives or overestimation of analyte concentration [6]. This technical guide explores the fundamental differences between the two primary immunoassay formats—competitive and sandwich—within the context of troubleshooting cross-reactivity, providing researchers with clear protocols and decision-making frameworks.

FAQ: Core Concepts and Selection

What is the fundamental difference between a competitive and a sandwich immunoassay?

The fundamental difference lies in the assay design and the type of analyte each is best suited to detect.

- Sandwich Immunoassays are non-competitive and require that the analyte has multiple, distinct epitopes (antigenic sites). Two antibodies—a capture antibody and a detection antibody—bind to different parts of the same analyte molecule, effectively "sandwiching" it. The measured signal is directly proportional to the amount of analyte present. This format is almost exclusively used for large molecules, such as proteins [40].

- Competitive Immunoassays are used for small molecules (haptens) that typically possess only a single epitope. The labeled analyte (or analog) and the unlabeled analyte from the sample compete for a limited number of antibody-binding sites. The measured signal is inversely proportional to the amount of analyte in the sample [40].

When should I choose a competitive format over a sandwich format, and vice versa?

Your choice is primarily dictated by the size of your analyte.

- Choose a Sandwich Immunoassay if: Your target analyte is a large protein (typically >5 kDa) with at least two distinct antibody-binding sites. This format generally offers higher specificity, greater sensitivity, and a broader dynamic range [40].

- Choose a Competitive Immunoassay if: Your target analyte is a small molecule (hapten), such as a hormone, drug, or toxin, which is too small to be bound by two antibodies simultaneously. This is the standard format for quantifying small-molecule drugs, like sulfonamides and fluoroquinolones [7] [40].

How does the assay format influence cross-reactivity?

Cross-reactivity is an antibody-dependent phenomenon, but the assay format and its conditions can significantly modulate its impact.

- In Sandwich Immunoassays: The requirement for two distinct antibodies to bind simultaneously to the same molecule inherently increases specificity and can reduce cross-reactivity. A cross-reacting molecule must have epitopes for both the capture and detection antibodies to generate a signal [40].

- In Competitive Immunoassays: Cross-reactivity is a more common challenge. A molecule with a similar structure to the target analyte may bind to the antibody's single binding site. The degree of cross-reactivity can be influenced by assay conditions. Research shows that using lower concentrations of antibodies and competing antigens can make a competitive assay more specific by reducing cross-reactivities by up to five-fold [7].

Can I change the cross-reactivity of an assay without developing new antibodies?

Yes, cross-reactivity is not an immutable property of the antibody itself. For competitive immunoassays, you can modulate selectivity by adjusting experimental conditions [7]:

- Reagent Concentration: Shifting to lower concentrations of antibodies and labeled antigens can decrease cross-reactivity, making the assay more specific.

- Incubation Time: Varying the reaction time can shift the assay from a kinetic to an equilibrium mode, which can alter the measured cross-reactivity profile.

- Heterologous Assay Formats: Using a labeled antigen analog that is structurally different from the one used for immunization can narrow the spectrum of selectivity by making the assay dependent on only a subset of the antibodies produced [7].

Troubleshooting Guide: Cross-Reactivity

Problem: Suspected cross-reactivity causing false positive results.

Potential Cause 1: The sample contains a structurally similar compound (e.g., a metabolite, a related protein, or a common drug) that is cross-reacting with the antibody.

- Solution:

- Confirm with an Orthogonal Method: Always follow up a positive immunoassay screen with a confirmatory test using a more specific technique, such as LC-MS/MS or GC-MS [20].

- Test for Known Cross-reactants: Spike the sample with suspected cross-reactants (e.g., pseudoephedrine in an amphetamine assay) and observe the signal change [20].

- Perform Dilutional Linearity: If the sample is serially diluted and the measured analyte concentration does not dilute proportionally, it may indicate interference from a cross-reactant with a different affinity [6].

Potential Cause 2: The assay format or conditions are amplifying the inherent cross-reactivity of the antibody.

- Solution:

- Optimize Reagent Concentrations: For competitive assays, titrate down the concentrations of the antibody and labeled antigen. Assays with sensitive detection and low reagent concentrations are often more specific [7].

- Shorten Incubation Time: Reducing the contact time between reagents and the sample can favor high-affinity, specific interactions over lower-affinity, cross-reactive binding [6].

- Explore a Heterologous Format: If possible, test a different labeled antigen (heterologous assay) to potentially improve specificity [7].

Problem: High background noise reducing assay specificity.

Potential Cause: Non-specific binding of antibodies or other proteins to the solid phase or to matrix components.

- Solution:

- Optimize Blocking: Ensure that all non-specific binding sites on the solid phase (e.g., the microplate) are effectively blocked. Test different blocking buffers (e.g., 1% BSA, 10% host serum, or commercial protein-free blockers) [41].

- Increase Stringency of Washes: Add a mild detergent (e.g., 0.05% Tween-20) to the wash buffer and increase the number or volume of wash steps [41].

- Use a Monoclonal Antibody: For the capture antibody in a sandwich assay, a monoclonal antibody can provide higher specificity and lower background than a polyclonal mixture [6].

Experimental Protocols & Data Analysis

Protocol 1: Establishing a Competitive ELISA

This protocol is adapted for the detection of a small molecule analyte, such as an antibiotic or drug [7] [41].

1. Reagent Preparation:

- Coating: Dilute an antigen conjugate (e.g., a drug-protein conjugate) in a carbonate-bicarbonate coating buffer (50 mM, pH 9.6).

- Blocking: Prepare a blocking buffer (e.g., 1% BSA in PBS or Tris-buffered saline).

- Antibody & Analyte: Prepare dilutions of the primary antibody and the standard analyte in an appropriate matrix diluent.

2. Plate Coating & Blocking:

- Add the antigen conjugate to a high-binding microplate (e.g., 100 µL/well).

- Incubate overnight at 4°C or for 1-2 hours at 37°C.

- Wash the plate 3 times with a wash buffer (e.g., PBS with 0.05% Tween-20).

- Add blocking buffer (200-300 µL/well) and incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature.

- Wash the plate 3 times.

3. Competitive Reaction:

- Add a fixed concentration of the primary antibody to all wells.

- Simultaneously add the standard (calibrator) or sample to the wells. The antibody, labeled antigen (on the plate), and unlabeled analyte (from the sample) will compete during incubation.

- Incubate for a defined period (e.g., 1 hour at 37°C).

- Wash the plate 3-5 times to remove unbound antibody.

4. Detection:

- Add an enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody (if using an unconjugated primary) or a streptavidin-enzyme conjugate (if using a biotinylated primary). Incubate and wash.

- Add the enzyme substrate (e.g., TMB for HRP) and incubate in the dark for a set time.

- Stop the reaction with an acid (e.g., 2M H₂SO₄ for TMB).

5. Data Analysis:

- Read the absorbance (450 nm for TMB).

- Plot the mean absorbance (or B/B₀, where B is the bound signal and B₀ is the maximum binding signal) against the log of the analyte concentration.

- Fit a 4- or 5-parameter logistic (4PL/5PL) curve to the data.

- Calculate the IC₅₀ (the concentration of analyte that inhibits 50% of the maximum signal). Cross-reactivity (CR) for a similar compound is calculated as: CR (%) = [IC₅₀ (Target Analyte) / IC₅₀ (Cross-reactant)] × 100% [7].

Protocol 2: Key Experiment to Modulate Cross-Reactivity

This experiment demonstrates how reagent concentration in a competitive immunoassay can be used to tune specificity [7].

Objective: To determine the effect of antibody and labeled antigen concentration on the observed cross-reactivity profile.

Methodology:

- Set up two versions of the same competitive immunoassay (e.g., for sulfonamides):

- Format A (High Stringency): Use a low, pre-optimized concentration of antibody and labeled antigen.

- Format B (Low Stringency): Use a higher concentration of the same reagents.

- For both formats, run a standard curve for the primary target analyte and for at least one key cross-reactant.

- Generate the dose-response curves and calculate the IC₅₀ for each compound in both formats.

- Calculate the cross-reactivity (%) for the cross-reactant in both Format A and Format B.

Expected Outcome: The data will typically show that Format A (low reagent concentration) yields a lower cross-reactivity percentage than Format B, demonstrating enhanced specificity under these conditions [7].

Table 1: Example Data from a Cross-Reactivity Modulation Experiment

| Assay Format | Reagent Concentration | IC₅₀ (Target) (ng/mL) | IC₅₀ (Cross-reactant) (ng/mL) | Cross-reactivity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Format A | Low | 1.0 | 25.0 | 4.0% |

| Format B | High | 5.0 | 25.0 | 20.0% |

Visual Workflows and Diagrams

Competitive vs. Sandwich Immunoassay Workflow

Troubleshooting Cross-Reactivity in Competitive Immunoassays

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Immunoassay Development

| Item | Function & Description | Example Use Cases & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Phase | Surface to which the capture molecule (antigen or antibody) is immobilized. | Microplates: Greiner, Costar, Nunc high-binding plates. Choice affects background and binding capacity [41]. |

| Coating Buffers | Provide optimal pH and ionic conditions for adsorbing proteins to the solid phase. | 50 mM Sodium Bicarbonate, pH 9.6 is common. PBS (pH 7.4) can also be used [41]. |

| Blocking Buffers | Proteins or other agents used to saturate remaining binding sites on the solid phase to reduce non-specific binding. | 1% BSA, 10% host serum, or commercial casein buffers. Critical for lowering background noise [41]. |

| Wash Buffers | Solutions with detergents used to remove unbound reagents and matrix components between assay steps. | PBS or Tris with 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST/TBST). Ensures specificity of the final signal [41]. |

| Detection Enzymes | Enzymes conjugated to antibodies or antigens that generate a measurable signal. | Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) & Alkaline Phosphatase (AP). HRP with TMB substrate is a common colorimetric system [41]. |

| Antibody Pairs | Matched set of capture and detection antibodies that bind to different epitopes on the same analyte. | Critical for Sandwich ELISA. Must be validated for pairing to ensure they do not sterically hinder each other [41] [40]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: What is cross-reactivity in multiplexed sensor arrays, and why is it considered advantageous?