Comparing Next-Generation Sequencing Platforms for Parasite Detection in 2025: A Guide for Researchers and Developers

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is revolutionizing parasitology by moving diagnostics beyond traditional, low-throughput methods.

Comparing Next-Generation Sequencing Platforms for Parasite Detection in 2025: A Guide for Researchers and Developers

Abstract

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is revolutionizing parasitology by moving diagnostics beyond traditional, low-throughput methods. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of modern NGS platforms—including Illumina, Oxford Nanopore, and PacBio—for detecting and characterizing protozoan and helminth infections. We explore foundational sequencing principles, detail methodological applications like metagenomic NGS (mNGS) and targeted sequencing, and offer troubleshooting strategies for workflow optimization. A critical validation and comparative analysis guides platform selection based on accuracy, throughput, cost, and specific parasitological applications, empowering researchers and drug development professionals to leverage these powerful tools for advanced diagnostics, outbreak surveillance, and drug discovery.

The NGS Revolution in Parasitology: Moving Beyond Microscopy

Parasitic diseases remain a significant global health challenge, affecting millions of people worldwide and causing substantial morbidity and mortality, particularly in underprivileged populations and low-income societies [1]. The accurate and timely diagnosis of these infections is crucial for effective treatment, control, and prevention. Traditional diagnostic methods have served as the cornerstone of parasitology for decades, but they present significant limitations that can impact patient care and public health outcomes. This article examines the critical diagnostic gap created by these conventional approaches and explores how next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies are addressing these shortcomings in research settings.

The World Health Organization estimates that intestinal parasitic infections alone affect approximately 67.2 million people worldwide, accounting for 492,000 disability-adjusted life years [1]. This substantial disease burden underscores the critical importance of reliable diagnostic methods that can accurately detect and identify parasitic infections. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the limitations of existing diagnostic approaches is fundamental to advancing the field and developing more effective detection strategies.

Conventional Diagnostic Methods and Their Limitations

Traditional techniques for parasite detection primarily include microscopy, immunodiagnostic-based approaches, and conventional molecular assays such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [1]. While these methods have been invaluable in both clinical and research contexts, they suffer from several inherent constraints that limit their effectiveness, particularly in complex diagnostic scenarios.

Microscopic Examination

Microscopy has long been considered the gold standard for parasite detection, but it demonstrates notably low sensitivity, especially in cases of low parasite burden. For instance, the sensitivity of light microscopy for detecting Entamoeba histolytica ranges from just 10% to 40% [1]. This technique is highly dependent on the skill and experience of the technician, is time-consuming and labor-intensive, and requires specialized equipment [2]. Furthermore, microscopic examination often fails to differentiate between morphologically similar species, which is particularly problematic for helminth eggs that cannot be morphologically differentiated at the species level without additional culturing steps [3].

Immunodiagnostic Methods

Serological tests like enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) provide an alternative to microscopy but introduce their own limitations. The sensitivity of serologic testing for E. histolytica in acute disease ranges from 70% to 80% but increases to nearly 100% in patients with hepatic amoebiasis [1]. These assays are prone to cross-reactivity with antigens from different parasite species, potentially leading to false-positive results [2]. Additionally, they may fail to distinguish between past and current infections, limiting their utility in acute clinical settings and outbreak investigations.

Conventional Molecular Assays

Standard PCR methods offer improved specificity over microscopy and serology but require meticulously designed primers tailored to specific target parasites [2]. This primer design demands an in-depth understanding of the parasite's genetic makeup, making the process often time-consuming and expensive [2]. Traditional PCR also typically lacks the capacity for multiplexing, limiting researchers to targeting single or few pathogens per reaction and potentially missing co-infections or unexpected pathogens.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Traditional Parasite Detection Methods

| Method | Sensitivity Limitations | Species Differentiation Capability | Multiplexing Capacity | Technical Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopy | Low (10-40% for E. histolytica) [1] | Limited; requires additional culturing for some helminths [3] | None | Labor-intensive; requires skilled technician [2] |

| Immunodiagnostics | Variable (70-80% for acute E. histolytica) [1] | Prone to cross-reactivity [2] | Limited | Cannot distinguish past vs. current infections [2] |

| Conventional PCR | Higher than microscopy but target-dependent | Good for specific targets | Low; requires multiple reactions | Primer design complex and time-consuming [2] |

The NGS Approach: Bridging the Diagnostic Gap

Next-generation sequencing technologies have emerged as powerful tools that address many limitations of traditional diagnostic methods. NGS enables the comprehensive sequencing of millions of DNA fragments simultaneously, providing unprecedented insights into parasitic infections [1] [4]. This high-throughput approach has transformed parasitology research by enabling comprehensive pathogen detection without prior assumptions about the causative agents.

Key NGS Methodologies in Parasitology

Several NGS approaches have proven particularly valuable in parasite detection and characterization. Metagenomic NGS (mNGS) allows for unbiased sequencing of all nucleic acids in a sample, making it ideal for detecting unexpected or novel pathogens [1]. Targeted NGS approaches, such as metabarcoding, focus on specific genetic regions like the 18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene, enabling highly sensitive detection of multiple parasite species simultaneously [2]. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) provides complete genetic information of parasites, facilitating studies on genetic diversity, drug resistance mechanisms, and transmission patterns [1].

Table 2: NGS Methodologies and Their Research Applications in Parasitology

| NGS Approach | Key Features | Primary Research Applications | Example Study Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metagenomic NGS (mNGS) | Unbiased sequencing of all nucleic acids in sample [1] | Detection of unexpected pathogens; outbreak investigation [1] | Higher positive detection rate for ESKAPE pathogens and/or fungi (28.4% vs 16.3% with culture) [5] |

| Targeted Metagenomics (Metabarcoding) | Amplification of specific marker genes (e.g., 18S rRNA, ITS-2) [2] | Species identification; parasite community profiling [3] | Simultaneous detection of 11 parasite species with varying read abundance [2] |

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Sequencing of entire parasite genomes [1] | Genetic diversity studies; drug resistance mechanism identification [1] | Understanding genetic interrelationships among parasites; identifying anti-parasitic drug resistances [1] |

Featured Experimental Protocol: 18S rRNA Metabarcoding for Intestinal Parasites

A recent study published in Scientific Reports exemplifies the application of NGS in parasite detection research. The protocol aimed to optimize 18S rRNA metabarcoding for the simultaneous diagnosis of 11 intestinal parasite species, demonstrating how NGS methodologies can overcome limitations of traditional approaches [2].

Sample Preparation and Library Construction

The researchers cloned the 18S rDNA V9 region of 11 parasite species into plasmids, creating a standardized reference panel. The target parasites included Clonorchis sinensis, Entamoeba histolytica, Dibothriocephalus latus, Trichuris trichiura, Fasciola hepatica, Necator americanus, Paragonimus westermani, Taenia saginata, Giardia intestinalis, Ascaris lumbricoides, and Enterobius vermicularis [2]. Equal concentrations of these 11 plasmids were pooled, and amplicon NGS targeting the 18S rDNA V9 region was performed using the Illumina iSeq 100 platform. The selection of the V9 region was strategic, as it efficiently captures a broader range of eukaryotes on the Illumina sequencing platform [2].

For library preparation, researchers amplified the plasmids using primers targeting the 18S rRNA V9 region with attached adaptors for NGS: 1391F (5′-TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAG GTACACACCGCCCGTC-3′) and EukBR (5′-GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAG TGATCCTTCTGCAGGTTCACCTAC-3′) [2]. The PCR amplification utilized KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix with the following cycling conditions: 95°C for 5 minutes, 30 cycles of 98°C for 30 seconds; 55°C for 30 seconds; 72°C for 30 seconds, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes. A limited-cycle (8-cycle) amplification followed to add multiplexing indices and Illumina sequencing adapters [2].

Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis

The mixed amplicons were pooled and sequenced on an Illumina iSeq 100 system using the Illumina iSeq 100 i1 Reagent v2 kit. For data analysis, the researchers employed Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology v2 (QIIME 2, 2023.2) to process the iSeq 100 data [2]. The workflow included demultiplexing and trimming low-quality sequence reads using Cutadapt (v4.5), followed by denoising, dereplication, and chimera filtering using DADA2 (v1.26) [2]. Taxonomic assignment of amplicon sequence variants utilized a custom database built from NCBI nucleotide sequences to encompass a broader range of parasite sequences compared to curated databases.

Key Findings and Optimization Insights

The analysis yielded 434,849 reads, successfully detecting all 11 parasite species, though with varying read abundances: Clonorchis sinensis (17.2%), Entamoeba histolytica (16.7%), Dibothriocephalus latus (14.4%), Trichuris trichiura (10.8%), Fasciola hepatica (8.7%), Necator americanus (8.5%), Paragonimus westermani (8.5%), Taenia saginata (7.1%), Giardia intestinalis (5.0%), Ascaris lumbricoides (1.7%), and Enterobius vermicularis (0.9%) [2]. The researchers identified that DNA secondary structures showed a negative association with output read numbers, and variations in amplicon PCR annealing temperature affected relative read abundances, providing crucial optimization parameters for future assay development.

NGS Workflow and Technical Considerations

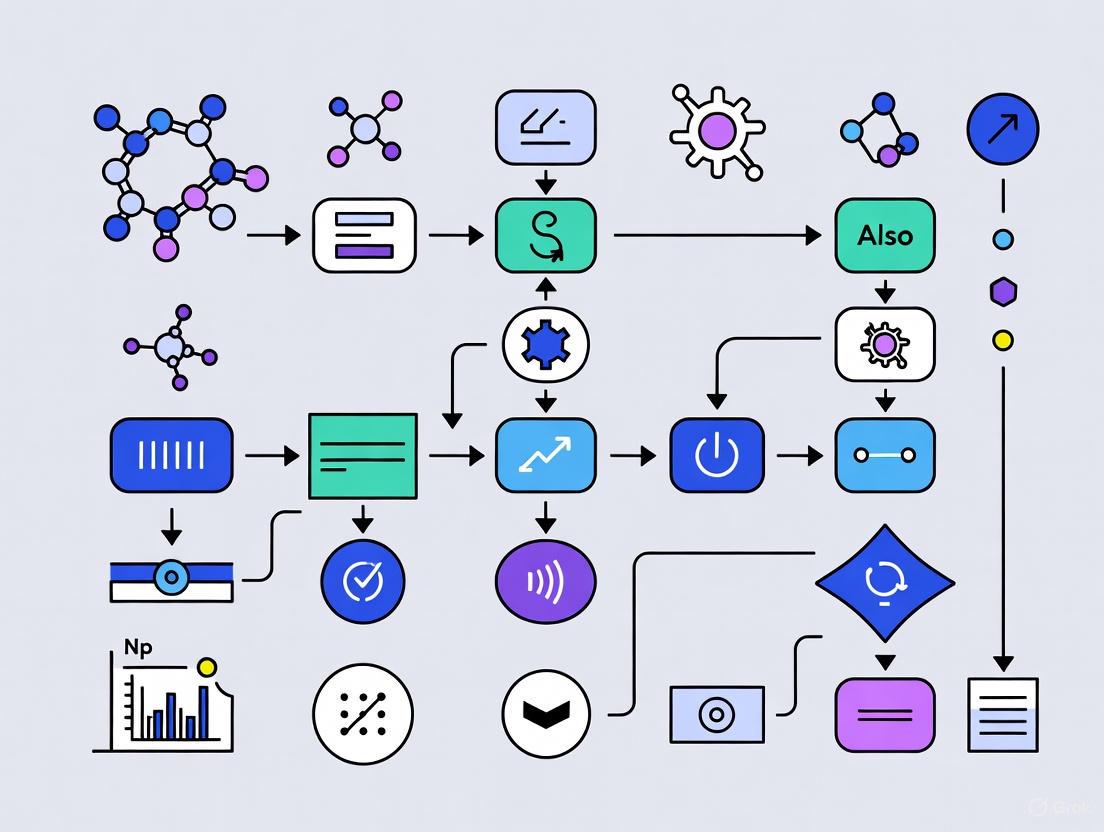

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for next-generation sequencing in parasite detection research, from sample preparation to data analysis:

NGS Workflow for Parasite Detection

Critical Optimization Parameters

Successful implementation of NGS for parasite detection requires careful optimization of several technical parameters. The aforementioned study demonstrated that annealing temperature during amplicon PCR significantly influences the relative abundance of output reads for each parasite [2]. Additionally, DNA secondary structures were found to negatively associate with read numbers, suggesting that bioinformatic correction algorithms may be necessary for accurate quantification. Background amplification of host and other eukaryotic DNA can compete with target protozoan sequences, potentially affecting detection sensitivity [6]. Establishing appropriate thresholds for true positives is also essential, as low numbers of target sequences may appear in negative controls [6].

Comparative Performance Data: NGS vs. Traditional Methods

Research directly comparing NGS with conventional diagnostic methods demonstrates the superior capabilities of the former in various applications. In veterinary parasitology, NGS-based nemabiome metabarcoding has proven invaluable for differentiating stronglyle species that are morphologically identical as eggs, providing crucial information for anthelmintic resistance management and epidemiological studies [3]. A study on kidney transplantation patients found that for organ preservation fluids, the positive rate of conventional culture was significantly lower than that of mNGS (24.8% vs 47.5%) [5]. Similarly, for recipient wound drainage fluids, conventional culture showed a positivity rate of just 2.1% compared to 27.0% with mNGS [5].

Table 3: Direct Comparison of Detection Rates Between Conventional Culture and mNGS

| Sample Type | Conventional Culture Positive Rate | mNGS Positive Rate | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organ Preservation Fluids | 24.8% (35/141) | 47.5% (67/141) | p < 0.05 [5] |

| Recipient Wound Drainage Fluids | 2.1% (3/141) | 27.0% (38/141) | p < 0.05 [5] |

| ESKAPE Pathogens and/or Fungi | 16.3% (23/141) | 28.4% (40/141) | p < 0.05 [5] |

Research Reagent Solutions for NGS-Based Parasite Detection

Implementing NGS methodologies for parasite detection requires specific reagents and tools. The following table outlines key research reagent solutions and their functions in typical NGS workflows for parasitology research.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for NGS-Based Parasite Detection

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolation of DNA/RNA from diverse sample types | Specialized kits (e.g., Fast DNA SPIN Kit for Soil) effective for parasite DNA extraction [2] |

| 18S rRNA V9 Region Primers | Amplification of target region for metabarcoding | 1391F and EukBR primers with adapter sequences enable NGS library preparation [2] |

| PCR Amplification Master Mix | High-fidelity DNA amplification | KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix provides high fidelity for accurate sequence representation [2] |

| Sequencing Kits | Library sequencing on NGS platforms | Illumina iSeq 100 i1 Reagent v2 kit suitable for targeted metabarcoding studies [2] |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Data processing and analysis | QIIME 2, Cutadapt, DADA2, and custom databases essential for sequence processing [2] |

The diagnostic gap created by traditional parasite detection methods represents a significant challenge in both clinical management and research contexts. Limitations in sensitivity, species differentiation capability, and multiplexing capacity constrain our understanding of parasitic diseases and hinder effective control strategies. Next-generation sequencing technologies offer powerful alternatives that overcome these limitations, enabling comprehensive parasite detection, species identification, and genetic characterization.

For researchers and drug development professionals, NGS platforms provide unprecedented insights into parasite biodiversity, transmission dynamics, and drug resistance mechanisms. The ability to simultaneously screen for multiple parasite species without prior assumptions about the causative agents represents a paradigm shift in diagnostic approaches. While challenges remain in standardization, bioinformatic analysis, and cost accessibility, the continued refinement and adoption of NGS methodologies promise to significantly advance parasitology research and contribute to improved global control of parasitic diseases.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have revolutionized parasite detection and genomic research, enabling scientists to decode complex pathogen genomes with unprecedented resolution. These technologies fall into two primary categories: short-read sequencing (exemplified by Illumina and Ion Torrent platforms) and long-read sequencing (pioneered by Oxford Nanopore Technologies [ONT] and Pacific Biosciences [PacBio]). Each platform employs distinct biochemical principles for detecting nucleotide incorporation, leading to characteristic strengths and limitations in output quality, read length, and application suitability [7] [8].

For parasitic disease research, where pathogens often possess complex genomes with repetitive elements and atypical genomic structures, platform selection critically impacts detection sensitivity, species resolution, and functional insight [1] [9]. This guide provides an objective comparison of dominant NGS platforms, supported by experimental data from parasite-focused studies, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting optimal methodologies for their specific applications.

Platform Comparison: Technical Specifications and Performance Metrics

The following tables summarize the core technical characteristics and performance metrics of major NGS platforms, based on aggregated data from recent comparative studies.

Table 1: Core Technical Specifications of Major NGS Platforms

| Platform/Technology | Representative Instruments | Read Length | Typical Run Time | Primary Detection Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina (Short-read) | MiSeq, NextSeq | 75-300 bp [7] | 1-3 days [7] | Fluorescently labeled reversible-terminator nucleotides [10] |

| Ion Torrent (Short-read) | PGM, S5 | ~200-400 bp [11] | Hours to a day [11] | Semiconductor detection of pH changes [11] |

| Oxford Nanopore (Long-read) | MinION, GridION | 5-20+ kb [7] [8] | < 24 hours to 72 hrs [7] [12] | Nanopore-based electrical current modulation [8] |

| PacBio (Long-read) | Sequel II, Revio | Several kb to >10 kb [7] [8] | Hours to days [8] | Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) fluorescence [8] |

Table 2: Comparative Performance in Pathogen Detection Studies

| Performance Metric | Illumina | Oxford Nanopore | Notes and Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Per-base Raw Accuracy | >99.9% [7] | ~99% with latest chemistry [8] | Nanopore accuracy has improved with R10+ pores & Dorado basecaller. |

| Sensitivity in LRTI Dx | 71.8% (average) [7] | 71.9% (average) [7] | Meta-analysis of lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) studies. |

| Specificity in LRTI Dx | 42.9% - 95% [7] | 28.6% - 100% [7] | Specificity range varies widely across studies. |

| Strengths | Superior genome coverage, high per-base accuracy [7] | Rapid turnaround, superior sensitivity for Mycobacterium [7] | ONT offers versatility and real-time sequencing capability [8]. |

| Cost & Throughput | High throughput, relatively low cost per base [7] | Lower upfront cost (MinION), portable [8] | PacBio HiFi is cost-intensive but offers high accuracy [8]. |

Experimental Approaches and Workflows

Targeted Amplicon Deep Sequencing (TADs) for Antimalarial Resistance

Objective: To compare the performance of Ion Torrent PGM and Illumina MiSeq platforms for targeted sequencing of Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance markers using TADs [10].

Methodology:

- Gene Targets: Six antimalarial drug resistance genes (pfcrt, pfdhfr, pfdhps, pfmdr1, pfkelch, pfcytochrome b)

- Sample Types: Whole blood samples (N=20) and rapid diagnostic test (RDT) blood spots (N=5) from patients with uncomplicated falciparum malaria

- Library Preparation: Target amplicons were amplified via PCR for the six genes and pooled across samples

- Sequencing: Libraries were sequenced on both Ion Torrent PGM and Illumina MiSeq platforms

- Validation: Variant calls were compared against conventional Sanger sequencing as the reference standard

- Analysis Metrics: Coverage (reads per amplicon), sequencing accuracy, variant accuracy, false positive/negative rates, and alternative allele detection in artificial mixed infections [10]

Key Findings:

- Both platforms demonstrated 99.83% sequencing accuracy and 99.59% variant accuracy compared to Sanger sequencing

- Illumina MiSeq provided significantly higher coverage (mean 28,886 reads/amplicon) than Ion Torrent PGM (mean 1,754 reads/amplicon)

- Both platforms could detect minor alleles down to 1% density in artificial mixtures at 500X coverage

- The methods enabled multiplexing of 96 samples per run, reducing costs by 86% compared to Sanger sequencing [10]

16S rRNA Profiling of Respiratory Microbiomes

Objective: To compare Illumina NextSeq and ONT MinION platforms for 16S rRNA gene sequencing of respiratory microbial communities, with relevance to parasite detection in complex samples [12].

Methodology:

- Sample Types: 34 respiratory samples (20 from ventilator-associated pneumonia patients, 14 from a swine model)

- Platform-Specific Protocols:

- Illumina: Targeted amplification of V3-V4 hypervariable region (∼300 bp) using QIAseq 16S/ITS Region Panel, sequenced on NextSeq (2×300 bp)

- Nanopore: Full-length 16S rRNA gene amplification (∼1,500 bp) using ONT 16S Barcoding Kit, sequenced on MinION Mk1C with R10.4.1 flow cell

- Bioinformatic Processing:

- Illumina: nf-core/ampliseq pipeline with DADA2 for error correction and SILVA 138.1 database for taxonomy

- Nanopore: Dorado basecaller (v7.3.11) and EPI2ME Labs 16S Workflow with the same reference database

- Analysis: Alpha/beta diversity, taxonomic profiling, and differential abundance analysis [12]

Key Findings:

- Illumina captured greater species richness, while ONT provided superior species-level resolution for dominant taxa

- ONT overrepresented certain taxa (e.g., Enterococcus, Klebsiella) while underrepresenting others (e.g., Prevotella, Bacteroides)

- Community evenness was comparable between platforms

- ONT's performance improved with longer sequencing durations (up to 72 hours) [12]

Figure 1: Core NGS Workflows for Pathogen Detection - This diagram illustrates the key steps in metagenomic (mNGS) and targeted (tNGS) next-generation sequencing approaches, highlighting the methodological divergence after nucleic acid extraction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NGS in Parasitology

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Products/Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality DNA/RNA from diverse sample types | QIAamp UCP Pathogen DNA Kit, MagPure Pathogen DNA/RNA Kit, Sputum DNA Isolation Kit [13] [12] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Preparation of sequencing libraries with platform-specific adapters | Illumina Nextera XT, ONT 16S Barcoding Kit, Ion Plus Fragment Library Kit [11] [12] |

| Target Enrichment Panels | Selective amplification or capture of target pathogen sequences | Respiratory Pathogen Detection Kit (198 primers), Custom probe panels for parasite genomes [14] [13] |

| Positive Controls | Monitoring assay performance and sensitivity | QIAseq 16S/ITS Smart Control, Synthetic DNA controls [12] |

| Barcoding/Indexing Kits | Multiplexing samples to increase throughput and reduce costs | QIAseq 16S/ITS Index Kit, ONT Native Barcoding Kit [12] |

Application in Parasite Research: Case Studies and Data Interpretation

Genomic Surveillance of Antimalarial Drug Resistance

Targeted NGS has proven particularly valuable for monitoring molecular markers of antimalarial drug resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. The well-defined resistance markers for chloroquine (pfcrt), antifolates (pfdhfr, pfdhps), and artemisinins (pfkelch) make this pathogen ideally suited for tNGS approaches [10]. In a study from Ubon Ratchathani, TADs on both Ion Torrent and Illumina platforms successfully identified complex haplotypes in pfcrt, with the dominant haplotype shifting from 58% prevalence in 2014 to 88% in 2017 samples, demonstrating the utility of NGS for tracking resistance dynamics [10].

Resolving Complex Parasite Genomes

Long-read sequencing technologies excel in characterizing complex genomic features of parasites that are difficult to resolve with short-read technologies. For Leishmania species, which exhibit remarkable genomic plasticity including mosaic aneuploidy and gene amplification, ONT and PacBio platforms have enabled complete assembly of repetitive regions and structural variants [9]. These features are crucial for understanding drug resistance mechanisms and virulence factors in these parasites. Similarly, ONT's ability to sequence full-length 16S rRNA genes provides superior species-level resolution for identifying bacterial co-infections in parasitic diseases [12].

Metagenomic versus Targeted Approaches for Polymicrobial Infections

A comprehensive comparison of mNGS and tNGS for lower respiratory infections revealed distinct performance characteristics relevant to parasite detection. While mNGS identified the highest number of species (80 species vs. 71 for capture-based tNGS and 65 for amplification-based tNGS), capture-based tNGS demonstrated superior diagnostic accuracy (93.17%) and sensitivity (99.43%) when benchmarked against comprehensive clinical diagnosis [13]. Amplification-based tNGS showed poor sensitivity for gram-positive (40.23%) and gram-negative bacteria (71.74%) but required fewer resources, suggesting its utility as a screening tool in resource-limited settings [13].

The choice between short-read and long-read sequencing technologies for parasite research depends heavily on the specific research objectives, required resolution, and available resources.

Short-read platforms (Illumina, Ion Torrent) remain the gold standard for applications requiring maximal base-level accuracy, high throughput, and cost-effectiveness for large sample sizes. They are ideal for single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) detection, variant calling, and targeted sequencing of well-characterized resistance markers, as demonstrated in antimalarial resistance monitoring [10]. However, their limited read length challenges assembly of complex repetitive regions common in parasite genomes.

Long-read platforms (ONT, PacBio) provide superior resolution for complex genomic regions, structural variants, and full-length gene sequencing, enabling species-level identification and assembly of challenging genomes like Leishmania [9]. ONT's portability and rapid turnaround time facilitate real-time field surveillance, crucial for outbreak response. While historically limited by higher error rates, recent chemistry and basecalling improvements have substantially enhanced accuracy [8].

For comprehensive pathogen detection in complex samples, hybrid approaches leveraging both technologies may provide optimal results, using short-read data for accuracy and long-read data for scaffolding and resolving repetitive elements. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve, the integration of these complementary platforms will further empower parasite research and drug development initiatives.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have revolutionized parasitology research, enabling the precise identification of pathogens, investigation of host-parasite interactions, and tracking of drug resistance mechanisms. Selecting the appropriate sequencing platform is crucial for designing effective studies, as each technology offers distinct advantages in read length, accuracy, throughput, and cost. This guide provides an objective comparison of three major platforms—Illumina, Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), and PacBio—focusing on their performance characteristics and applications in parasite detection and analysis. By examining experimental data and technical specifications, this overview equips researchers with the information needed to select the optimal platform for their specific research requirements in parasitology and drug development.

Technology Comparison at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of the three major sequencing platforms, highlighting key differences in their sequencing principles, output, and typical applications.

Table 1: Core sequencing platform characteristics

| Feature | Illumina | Oxford Nanopore (ONT) | PacBio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Principle | Short-read; sequencing by synthesis with fluorescently labeled nucleotides [1] | Long-read; nanopore electrical signal detection [15] | Long-read; Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) with fluorescent detection in zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs) [15] |

| Typical Read Length | 50-300 bp [16] | 20 kb to >4 Mb (ultra-long reads) [17] | 10-20 kb (HiFi reads) [15] |

| Raw Read Accuracy | >99.9% (Q30) [18] | ~99% (Q20) with latest chemistries [19] [17] | >99.9% (Q30) for HiFi reads [17] |

| Typical Run Time | 1-3 days [13] | 72 hours (standard), 24 hours (rapid) [17] | 24 hours [17] |

| Key Strengths | High throughput, low per-base cost, well-established bioinformatics tools | Portability, real-time data analysis, ultra-long reads, direct RNA/DNA sequencing | Very high accuracy, long reads, simultaneous epigenetic modification detection |

| Common Parasitology Applications | Targeted sequencing (amplicon & capture-based), metagenomic surveys, population genetics | Rapid field surveillance, whole-genome sequencing, structural variant detection, direct RNA sequencing | High-quality genome assembly, discovery of structural variants, haplotype phasing |

Performance Data in Microbial and Parasitic Research

Empirical data from recent studies directly comparing these platforms provide critical insights for platform selection. Performance varies significantly based on the specific application, such as 16S rRNA gene sequencing for microbiome studies or targeted methods for pathogen detection.

Taxonomic Resolution in 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

A 2025 study comparing 16S rRNA gene sequencing for gut microbiota analysis demonstrated clear differences in species-level classification performance.

Table 2: Species-level classification performance in rabbit gut microbiota (2025 study) [19]

| Platform | Target Region | Species-Level Classification Rate | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina MiSeq | V3-V4 hypervariable region | 48% | Lower resolution due to shorter read length |

| PacBio Sequel II | Full-length 16S rRNA gene | 63% | Improved resolution with full-length sequencing |

| ONT MinION | Full-length 16S rRNA gene | 76% | Highest resolution among the three platforms |

While ONT showed the highest technical resolution, a significant limitation across all platforms was that many species-level classifications were assigned ambiguous labels like "uncultured_bacterium," highlighting database limitations rather than technological failures [19].

Diagnostic Performance in Respiratory Infection Pathogen Detection

A 2025 clinical study on lower respiratory tract infections compared different sequencing approaches, providing valuable data on pathogen detection capabilities relevant to parasitology research.

Table 3: Diagnostic performance of different NGS approaches in lower respiratory infections [13]

| Sequencing Method | Total Species Detected | Accuracy vs. Clinical Diagnosis | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metagenomic NGS (mNGS) | 80 species | Not specified | Highest number of species identified; suited for rare/novel pathogen detection |

| Capture-based tNGS | 71 species | 93.17% | Best overall diagnostic performance; ideal for routine diagnostics |

| Amplification-based tNGS | 65 species | Lower sensitivity for bacteria | Faster results with lower resource requirements; lower sensitivity for Gram-positive (40.23%) and Gram-negative (71.74%) bacteria |

This study demonstrates that targeted NGS (tNGS) methods, particularly capture-based approaches, can provide superior diagnostic accuracy compared to unbiased metagenomic sequencing, though with fewer total species detected [13].

Experimental Protocols for Parasite Detection

Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS) Workflow

The mNGS protocol enables comprehensive, unbiased detection of parasites and other pathogens in clinical samples without prior knowledge of the causative agent [13] [20].

Figure 1: mNGS workflow for comprehensive pathogen detection.

Key Steps and Reagents:

Sample Collection & Nucleic Acid Extraction: Collect bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), tissue, or stool samples in sterile containers. Extract total nucleic acids using kits such as the QIAamp UCP Pathogen DNA Kit (Qiagen) or MagPure Pathogen DNA/RNA Kit (Magen), which efficiently lyse diverse pathogens including hardy parasite cysts [13] [20].

Host Depletion: Treat samples with Benzonase and Tween20 to degrade human DNA and enrich for microbial sequences, significantly improving detection sensitivity for low-abundance parasites [13].

Library Preparation: Fragment purified DNA, followed by adapter ligation and amplification. For RNA viruses or parasite transcripts, include ribosomal RNA depletion and reverse transcription steps [13].

Sequencing: Process libraries on Illumina (e.g., NextSeq 550Dx) or Nanopore (MinION) platforms. Illumina typically generates 75-150 bp reads, while ONT produces long reads spanning full-length parasite genes [13] [21].

Bioinformatic Analysis: Process raw data through quality filtering, adapter trimming, and host sequence subtraction. Classify microbial reads using curated databases such as the Parasite Genome Identification Platform (PGIP), which contains 280 quality-filtered parasite genomes for accurate taxonomic assignment [20].

Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing (tNGS) Using Molecular Inversion Probes

Targeted NGS approaches like Molecular Inversion Probes (MIPs) enrich specific parasite sequences before sequencing, improving sensitivity and reducing cost compared to mNGS [18].

Figure 2: Targeted sequencing workflow using molecular inversion probes.

Key Steps and Reagents:

MIP Design: Design single-stranded DNA probes with target-specific arms flanking a universal linker sequence. MIPs can multiplex >10,000 probes in a single reaction, covering diverse parasite genomes, virulence factors, and drug-resistance markers [18].

Hybridization & Gap-Fill: Incubate MIP pool with sample DNA. Probes hybridize to complementary target regions, and DNA polymerase extends across the gap using the target sequence as a template [18].

Ligation: DNA ligase (e.g., Ampligase) seals the nicks, creating circular DNA molecules containing the captured parasite sequences [18].

Exonuclease Treatment: Add exonuclease I and III to degrade remaining linear DNA, enriching for circularized MIP products while reducing non-target background [18].

Amplification & Sequencing: Amplify circularized templates with universal primers containing platform-specific adapters and barcodes for multiplexing. Sequence on Illumina (MiniSeq) or Nanopore platforms, requiring only ~0.1 million reads per sample for sensitive detection [18] [13].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below outlines key reagents and kits used in parasite sequencing workflows, with their specific functions in the experimental pipeline.

Table 4: Essential research reagents for parasite sequencing workflows

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| QIAamp UCP Pathogen DNA Kit (Qiagen) | Efficient lysis and purification of pathogen nucleic acids from clinical samples | mNGS library prep; effective for tough parasite cysts [13] |

| DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (QIAGEN) | Optimized DNA extraction from complex, inhibitor-rich samples like soil or stool | 16S rRNA sequencing; parasite egg detection in environmental samples [19] |

| Oxford Nanopore 16S Barcoding Kit | Amplification and barcoding of full-length 16S rRNA gene for multiplexing | Microbiome studies; analysis of parasite-induced dysbiosis [19] [12] |

| Respiratory Pathogen Detection Kit (KingCreate) | Amplification-based tNGS with 198 microorganism-specific primers | Targeted detection of parasite co-infections in respiratory samples [13] |

| SMRTbell Prep Kit 3.0 (PacBio) | Library preparation for HiFi sequencing of long DNA fragments | Full-length parasite gene sequencing and genome assembly [16] |

| Parasite Genome Identification Platform | Curated database of 280 parasite genomes for taxonomic classification | Bioinformatic parasite identification from mNGS/tNGS data [20] |

The choice between Illumina, Oxford Nanopore, and PacBio platforms for parasite research depends heavily on the specific study objectives, required resolution, and available resources. Illumina remains the workhorse for high-throughput targeted sequencing and metagenomic surveys where cost-effectiveness is paramount. Oxford Nanopore excels in rapid field deployment, real-time analysis, and detecting structural variants through ultra-long reads. PacBio's HiFi sequencing provides the gold standard for accurate long-read data, ideal for genome assembly and detecting genetic variations.

For comprehensive pathogen detection without prior assumptions, mNGS on Illumina or ONT platforms offers the broadest coverage. For sensitive detection of specific parasites in complex samples, targeted approaches like MIPs or capture-based tNGS provide superior performance. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve, these platforms will further empower researchers to tackle challenging questions in parasite biology, host-pathogen interactions, and drug development.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized infectious disease research by providing a powerful, high-throughput tool for pathogen detection, genotyping, and drug resistance screening. For researchers and drug development professionals working with parasites and other complex pathogens, NGS offers unparalleled advantages over traditional diagnostic methods, enabling a more comprehensive and precise approach to understanding and combating infectious diseases [22] [1].

Core Advantages of NGS in Pathogen Research

The transition from traditional methods to NGS represents a paradigm shift in diagnostic and research capabilities. The table below summarizes the key advantages NGS holds over conventional techniques.

Table 1: Comparison of Pathogen Detection Methods

| Feature | Traditional Methods (Microscopy/Culture) | PCR/Multiplex PCR | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Low | Moderate | Ultra-high (millions of fragments in parallel) [4] [23] |

| Pathogen Hypothesis | Required | Required | Unbiased; no prior hypothesis needed [24] |

| Sensitivity | Low (e.g., 10-40% for some parasites) [1] | High for targeted agents | High, capable of detecting low-frequency variants (<1%) [25] [23] |

| Detection Scope | Limited to cultivable/visible pathogens | Limited to predefined primers/probes [22] | Comprehensive; can discover novel pathogens [22] [26] |

| Typing & Resistance | Phenotypic testing possible but slow | Limited to known resistance genes | Comprehensive genotyping and detection of known/novel resistance mechanisms [22] [1] |

| Turnaround Time | Days to weeks | Hours to days | Days (rapidly improving) [4] |

Comparative Performance of NGS Platforms

Selecting an appropriate NGS platform is critical for research outcomes. The choice often involves a trade-off between read length, accuracy, and cost. The following table compares the characteristics of major short-read and long-read sequencing technologies.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of NGS Platform Characteristics

| Platform/Technology | Read Length | Key Principle | Key Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina (SBS) | Short (50-600 bp) [27] | Sequencing-by-Synthesis with reversible dye-terminators [27] | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS), Targeted Sequencing, RNA-Seq [26] [23] | High accuracy (>99%); industry standard; higher cost for WGS [4] [27] |

| Ion Torrent | Short (200-400 bp) [27] | Semiconductor sequencing detecting H+ ions [27] | Targeted sequencing, WGS | Faster run times; may struggle with homopolymer regions [27] |

| Oxford Nanopore | Long (avg. 10,000-30,000 bp) [27] | Electrical detection of nucleic acids via protein nanopores [27] | Whole Genome Sequencing, Metagenomics, Structural variant detection | Real-time sequencing; portable; higher error rate requires robust bioinformatics [4] [27] [25] |

| PacBio (SMRT) | Long (avg. 10,000-25,000 bp) [27] | Real-time sequencing in zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs) [27] | De novo genome assembly, Epigenetics, Complex region resolution | Lower throughput; higher cost per sample [27] |

Recent experimental data directly compares the performance of these platforms. A 2025 study compared four NGS platforms—Illumina iSeq100, Illumina MiSeq, MGI DNBSeq-G400, and Oxford Nanopore Mk1C MinION—for detecting drug resistance mutations in HIV, HBV, HCV, SARS-CoV-2, and Tuberculosis samples [25]. The study demonstrated a high concordance for majority and minority variants across all platforms. However, Nanopore technology was noted to report a higher number of minority mutations (those with a frequency below 20%), which may reflect its different error profile or sensitivity [25]. This highlights the importance of understanding platform-specific performance when analyzing minority variants in quasispecies populations, such as those found in viruses and parasites.

Experimental Protocols for NGS-Based Pathogen Analysis

Metagenomic NGS (mNGS) for Pathogen Detection

Metagenomic NGS allows for the unbiased detection of all pathogens in a sample without prior culturing or specific hypothesis, making it ideal for diagnosing unknown or mixed infections [24] [28].

Detailed Workflow:

- Sample Collection & Nucleic Acid Extraction: Collect relevant clinical sample (e.g., blood, BALF, tissue). Extract total DNA/RNA using commercial kits (e.g., TIANamp Micro DNA Kit). The choice of extracting DNA, RNA, or both is critical for a comprehensive pathogen profile [24].

- Library Preparation: Fragment the nucleic acids mechanically (sonication) or enzymatically. Ligate platform-specific adapter sequences to the fragments. These adapters allow the fragments to bind to the sequencer and serve as priming sites. Optional amplification is performed to generate sufficient material [4] [23]. For multiplexing, unique index barcodes are added to samples from different sources [1] [23].

- Sequencing: Load the prepared library onto the chosen NGS platform (e.g., Illumina, Nanopore) for massively parallel sequencing [4].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Control & Preprocessing: Use tools like FastQC and Trimmomatic to remove low-quality reads and adapter sequences [28].

- Host Depletion: Map reads to a host reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) using Bowtie2 and remove aligned reads to enrich for pathogen sequences [28].

- Pathogen Identification: Classify the remaining reads against curated pathogen databases (e.g., using Kraken2) or perform de novo assembly to identify unknown organisms [28]. Platforms like the Parasite Genome Identification Platform (PGIP) automate this process with a dedicated, quality-controlled parasite genome database [28].

The following diagram illustrates the core logical workflow of mNGS analysis:

Diagram 1: mNGS Pathogen Detection Workflow

Targeted NGS for Drug Resistance Screening

Targeted NGS focuses on specific genomic regions associated with drug resistance, providing deep coverage that enables the detection of low-frequency minority variants that can lead to treatment failure [22] [25].

Detailed Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Extract DNA/RNA from the pathogen of interest.

- Target Amplification: Using PCR, amplify the specific genes known to harbor resistance mutations. For example, in tuberculosis, this could target genes like rpoB (rifampin resistance) and katG (isoniazid resistance). Multiplex PCR assays can cover multiple regions simultaneously. Commercially available kits like the DeepChek assays are designed for this purpose for various pathogens [25].

- Library Preparation: Pool the resulting amplicons. The library can be prepared similarly to the mNGS workflow, often involving fragmentation (though sometimes amplicons are used directly), adapter ligation, and indexing [25].

- Sequencing & Analysis: Sequence the library, typically using high-accuracy short-read platforms like Illumina to ensure confident variant calling. Bioinformatic analysis involves:

The diagram below outlines the key steps in this targeted approach.

Diagram 2: Targeted NGS for Resistance Screening

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of NGS-based pathogen research relies on a suite of reliable reagents and software tools. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments and the broader field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for NGS-Based Pathogen Research

| Item | Function | Example Products / Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolate high-quality DNA/RNA from diverse clinical samples. | Viral NA Large Volume kit (Roche) [25], TIANamp Micro DNA Kit [24] |

| Targeted Amplification Assays | Amplify specific genomic regions for resistance screening. | DeepChek Assays (HIV, HBV, HCV, TB, SARS-CoV-2) [25] |

| Library Prep Kits | Fragment, end-repair, A-tail, and ligate adapters for sequencing. | DeepChek NGS Library Prep Kit [25], Platform-specific kits (Illumina) |

| Sequence Analysis Software | For quality control, alignment, variant calling, and reporting. | DeepChek Software [25], PGIP (Parasite Genome ID Platform) [28] |

| Curated Genomic Databases | Reference for accurate pathogen identification and typing. | PGIP Curated Parasite Database [28], NCBI, WormBase, VEuPathDB [28] |

In conclusion, NGS technologies provide researchers and drug developers with a powerful, multifaceted toolkit that surpasses traditional methods in scope, sensitivity, and depth of information. The ability to comprehensively detect pathogens, precisely type them, and screen for drug resistance markers in a single assay positions NGS as an indispensable technology for advancing infectious disease research and personalized treatment strategies.

Implementing NGS for Parasite Detection: From mNGS to Targeted Approaches

Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS) represents a paradigm shift in diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease research. This culture-independent, hypothesis-free approach enables the comprehensive detection of pathogens—including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites—by sequencing all nucleic acids in a clinical sample and comparing them against microbial databases [29]. Unlike targeted molecular methods that require prior suspicion of specific pathogens, mNGS offers the unique advantage of identifying unexpected, novel, or co-infecting organisms, making it particularly valuable for diagnosing complex infections where conventional tests fail [30] [29]. As sequencing technologies advance and costs decline, mNGS is increasingly transitioning from research settings to clinical laboratories, offering researchers and drug development professionals a powerful tool for pathogen discovery, outbreak investigation, and antimicrobial resistance surveillance. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of mNGS performance against alternative diagnostic methods, supported by experimental data and technical specifications to inform platform selection for parasite detection research and broader infectious disease applications.

Performance Comparison: mNGS Versus Established Diagnostic Methods

Diagnostic Accuracy Across Infection Types

Extensive clinical studies have validated the diagnostic performance of mNGS across various infection types and sample matrices. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent investigations:

Table 1: Diagnostic Performance of mNGS Across Different Infection Types

| Infection Type | Comparison Method | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Area Under Curve (AUC) | Sample Size | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spinal Infections | Tissue Culture Technique | 81 | 75 | 0.85 | 770 patients | [31] |

| Tuberculosis | Culture | 66.7 | 97.1 | N/A | 70 patients | [32] |

| Tuberculosis | Xpert MTB/RIF | 76.9 | N/A | N/A | 19 patients | [32] |

| Tuberculosis | Real-time PCR | 92.31 | 100 | N/A | 556 samples | [33] |

| Lower Respiratory Tract Infections | Traditional Methods | 86.7% positive rate | N/A | N/A | 165 patients | [30] |

The data demonstrates that mNGS consistently outperforms conventional culture methods in sensitivity while maintaining high specificity. In spinal infection diagnosis, mNGS showed markedly higher sensitivity (81%) compared to tissue culture technique (34%), though with moderately lower specificity (75% versus 93%) [31]. For tuberculosis detection, mNGS demonstrated superior sensitivity (66.7%) to culture (36.1%) and comparable sensitivity to Xpert MTB/RIF (76.9% versus 61.5%) [32]. A large-scale study on tuberculosis diagnosis found nearly perfect agreement between mNGS and real-time PCR, with 98.38% overall agreement and a kappa value of 0.896, indicating that both molecular methods perform exceptionally well for Mycobacterium tuberculosis detection [33].

Advantages in Complex Diagnostic Scenarios

mNGS provides particular value in diagnostically challenging scenarios. In lower respiratory tract infections, mNGS showed significantly higher positive detection rates (86.7%) compared to traditional methods (41.8%), with special advantage in detecting polymicrobial infections and rare pathogens [30]. The technology identified 29 pathogen species missed by conventional methods, including non-tuberculous mycobacteria, Prevotella, anaerobic bacteria, and various viruses [30]. This comprehensive detection capability directly impacts patient management, with one study reporting that mNGS results led to treatment modifications in 72.13% of patients, including antibiotic reduction in 32.73% of cases [30].

Comparison with Emerging Targeted NGS

Targeted NGS (tNGS) has emerged as an alternative approach that uses amplification or probe capture to enrich for predefined pathogen targets before sequencing. A prospective study comparing tNGS and mNGS in lower respiratory tract infections found no statistically significant difference in overall sensitivity (74.75% vs 78.64%) or specificity (81.82% vs 93.94%) between the two methods [34]. However, tNGS demonstrated significantly higher sensitivity for fungal detection (27.94% vs 17.65%) and successfully identified cases of Pneumocystis jirovecii that were missed by other methods [34]. The tNGS approach offers advantages including simultaneous DNA/RNA detection, lower cost, reduced host DNA interference, and easier workflow standardization [34].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard mNGS Workflow for Pathogen Detection

The standard mNGS workflow consists of multiple critical steps that influence downstream results:

Table 2: Key Steps in mNGS Laboratory Protocol

| Step | Description | Common Kits/Reagents | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Processing | Volume: 200-300 µL of BALF, CSF, blood, or tissue homogenate | TIANamp Micro DNA Kit (DP316) [32] [34] | Release and stabilize nucleic acids |

| DNA Extraction | Purification of total nucleic acid | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kits [34] | Quantity DNA mass (>5 ng required) |

| Library Preparation | DNA fragmentation (200-300 bp), end repair, adapter ligation | Illumina Nextera, Ion Xpress Fragment Library Kit [35] | Prepare fragments for sequencing |

| Quality Control | Assess library concentration and fragment size | Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer [32] | Ensure library quality before sequencing |

| Sequencing | Platform-dependent run | Illumina NextSeq, MiSeq, NovaSeq; Ion Torrent PGM [33] [35] | Generate sequence reads |

The workflow begins with sample collection, typically involving bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), blood, or tissue samples collected using sterile techniques to minimize contamination [30]. Nucleic acid extraction then isolates total DNA, with many protocols using the TIANamp Micro DNA Kit or similar products [32] [34]. For sequencing platforms requiring nanogram inputs, the total DNA mass must be quantified using fluorescent assays such as Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kits [34].

Library preparation involves fragmenting DNA to 200-300 bp, followed by end repair, adapter ligation, and potential amplification. Enzymatic fragmentation methods (e.g., "Fragmentase" in Ion Xpress kits) can reduce hands-on time compared to physical shearing [35]. The Nextera method (Illumina) uses transposase enzyme to simultaneously fragment DNA and add adapters, enabling library preparation in approximately 90 minutes [35]. Quality control steps using instruments like the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer ensure appropriate library concentration and fragment size distribution before sequencing [32].

Bioinformatic Analysis Pipeline

Following sequencing, raw data undergoes comprehensive bioinformatic processing:

Quality Filtering: Tools like fastp remove low-quality reads (Q-score <30), short sequences (<35 bp), and adapter contamination [33] [34].

Host DNA Depletion: Alignment to human reference genomes (GRCh38/hg19) using BWA or bowtie2 removes host-derived sequences, which can constitute >90% of reads in BALF samples [33] [32] [34].

Microbial Alignment: Remaining reads are aligned against curated pathogen databases (bacterial, viral, fungal, parasitic) using tools like SNAP or BLAST [32] [34]. These databases typically include RefSeq genomes from NCBI and clinically relevant species from microbiology references.

Pathogen Identification: Statistical thresholds determine true pathogens versus background. For Mycobacterium tuberculosis, some protocols use SMRNs (Standardized Microbial Read Numbers) ≥1 [33], while other approaches use genome coverage (>1%) and minimum read counts (>3) to filter out contaminants [34].

Negative controls processed alongside clinical samples help identify environmental or reagent contaminants that must be subtracted from final results [30] [34].

Sequencing Platform Comparison

Technical Specifications of Major Platforms

Multiple sequencing platforms support mNGS applications, each with distinct performance characteristics:

Table 3: Comparison of Sequencing Platforms for mNGS Applications

| Platform | Maximum Output | Read Length | Run Time | Reads per Run | Best Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina MiSeq | 15 Gb | 2 × 300 bp | 5-55 hours | 25 million | Amplicon sequencing, small genomes |

| Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | 6000 Gb | 2 × 150 bp | 19-40 hours | 20 billion | Large studies, high-depth sequencing |

| Ion Torrent PGM | 2 Gb | 200-400 bp | 3-4 hours | 4-5 million | Rapid turnaround, small panels |

| Pacific Biosciences | Variable | >10,000 bp | 0.5-4 hours | 500,000 | Complete genome assembly, structural variants |

Platform selection depends on research priorities. Illumina platforms generally provide higher throughput and accuracy, with MiSeq suitable for targeted applications and NovaSeq enabling large-scale studies [36] [37]. Ion Torrent systems offer faster turnaround times but may exhibit sequence context bias, particularly in extremely AT-rich genomes like Plasmodium falciparum, where approximately 30% of the genome may receive no coverage [35]. Pacific Biosciences and Oxford Nanopore Technologies generate long reads that facilitate assembly and structural variant detection but at lower throughput and higher per-base cost [35].

Platform Performance in Microbiome Studies

Direct comparisons between platforms reveal performance differences relevant to pathogen detection. In oral microbiome studies, NovaSeq produced significantly higher read counts (193,081 ± 91,268) compared to MiSeq (71,406 ± 35,095), resulting in more operational taxonomic units (OTUs) and better detection of rare taxa [37]. Both platforms showed similar community diversity metrics and strong correlation in relative abundance measurements, though NovaSeq's higher sensitivity makes it preferable for large-scale studies requiring detection of low-abundance organisms [37].

Performance varies across genomic contexts. While most platforms handle GC-rich, neutral, and moderately AT-rich genomes effectively, extreme GC content affects coverage uniformity. In one systematic comparison, Ion Torrent displayed profound bias when sequencing the extremely AT-rich Plasmodium falciparum genome, while Pacific Biosciences and Illumina platforms maintained more uniform coverage [35]. The enzyme used for amplification during library preparation significantly influences this bias, with Kapa HiFi polymerase demonstrating reduced bias compared to standard enzymes [35].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful mNGS implementation requires carefully selected reagents and tools at each workflow stage:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for mNGS Workflows

| Category | Product Examples | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | TIANamp Micro DNA Kit (DP316) [32] | Optimal for low-biomass samples; minimum 5 ng input |

| DNA Quantitation | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kits [34] | Fluorometric quantification superior to spectrophotometry |

| Library Preparation | Illumina Nextera, Ion Xpress Fragment Library Kit [35] | Nextera enables rapid preparation (90 minutes) |

| Polymerase Enzymes | Kapa HiFi Polymerase [35] | Reduces GC bias in amplification steps |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NextSeq CN500 [33] | Used in clinical validation studies with 75 bp reads |

| Bioinformatics Tools | fastp, BWA, bowtie2, SNAP [33] [34] | Open-source options for quality control and alignment |

Interpretation Guidelines and Diagnostic Criteria

Distinguishing True Pathogens from Background

Accurate interpretation of mNGS results requires distinguishing true infections from environmental contamination or background microbial communities:

Critical interpretation factors include:

Read Thresholds: Establishing minimum read counts or relative abundance thresholds specific to sample type and pathogen. For Mycobacterium tuberculosis, some protocols consider any reads (SMRNs ≥1) as significant due to its clinical importance and low background rates [33].

Genomic Coverage: Calculating the percentage of reference genome covered by sequencing reads. Most true pathogens show >1% genome coverage, while contaminants exhibit patchy or minimal coverage [34].

Background Contamination: Subtracting organisms present in negative controls and those known to be common contaminants (e.g., skin flora in tissue samples).

Clinical Correlation: Integrating patient symptoms, immune status, radiologic findings, and other test results to determine clinical significance.

For spinal infections, a multidisciplinary team approach incorporating histopathological findings, imaging results, and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) criteria provides the most accurate reference standard [31]. In lower respiratory tract infections, final diagnosis should integrate mNGS results with culture, PCR, antigen testing, and clinical presentation [30].

Resolving Discordant Results

When mNGS and conventional tests yield discordant results, resolution strategies include:

Additional Testing: Using alternative molecular methods like Xpert MTB/RIF for tuberculosis confirmation [33].

Quantitative Correlation: Analyzing relationships between mNGS read counts and PCR cycle threshold (Ct) values. Strong negative correlation (r = -0.668, P < 0.001) between mNGS standardized read numbers and RT-PCR Ct values supports true positive calls [33].

Sample Quality Assessment: Reviewing internal control performance and DNA quality metrics.

In tuberculosis diagnosis, discordant cases often involve extremely low bacterial loads. mNGS-positive/RT-PCR-negative samples typically show low standardized read numbers (median: 7 vs. 1788 in concordant positives), while mNGS-negative/RT-PCR-positive samples exhibit higher Ct values (median: 22.97 vs. 17.06 in concordant positives) [33]. These patterns reflect the different detection limits and technical variations between methods rather than true discrepancies.

mNGS represents a transformative technology for comprehensive pathogen detection with demonstrated superiority to culture-based methods and complementary value to targeted molecular assays. Its unbiased nature makes it particularly valuable for diagnostically challenging cases, immunocompromised patients, and detection of fastidious or novel pathogens. While platform selection involves trade-offs between throughput, read length, cost, and turnaround time, Illumina systems currently dominate clinical applications due to their accuracy and established workflows. Successful implementation requires careful attention to each step from sample collection through bioinformatic analysis and clinical interpretation. As costs decline and workflows standardize, mNGS is poised to become an increasingly accessible tool for pathogen detection in both research and clinical settings, particularly when integrated with conventional methods within a structured diagnostic framework.

In the field of parasite detection research, next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized our ability to identify and characterize pathogenic organisms. Two principal approaches—targeted metagenomics (often referred to as metabarcoding) and shotgun metagenomics—enable researchers to detect and monitor parasitic infections with unprecedented resolution. Targeted metagenomics focuses on amplifying and sequencing specific marker genes, such as the 18S rRNA gene, for taxonomic classification [1]. In contrast, shotgun metagenomics sequences all DNA present in a sample without targeting specific regions [38]. For researchers investigating parasitic diseases, understanding the technical nuances, performance characteristics, and limitations of these approaches is crucial for selecting the appropriate methodology for their specific research objectives, whether for clinical diagnostics, biodiversity assessment, or surveillance studies [1] [38].

Technical Foundations and Key Differences

The fundamental distinction between these approaches lies in their scope and methodology. Targeted metagenomics using markers like 18S rRNA relies on PCR amplification of conserved, taxonomically informative gene regions before sequencing [39] [40]. This method requires careful primer selection to ensure amplification of the target parasite groups while minimizing amplification bias [41]. Shotgun metagenomics, however, employs random sequencing of all DNA fragments in a sample without prior amplification, followed by computational assembly and classification [38] [28].

The choice of genetic marker is critical in targeted metagenomics. The 18S rRNA gene is widely used for eukaryotic pathogens like parasites due to its conserved regions that facilitate primer design and variable regions that provide taxonomic discrimination [39] [41]. Other markers include the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions, which offer higher discriminatory power for specific fungal parasites [41].

Table 1: Core Methodological Differences Between Targeted and Shotgun Metagenomics

| Feature | Targeted Metagenomics (Metabarcoding) | Shotgun Metagenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Target | Specific marker genes (e.g., 18S rRNA, ITS) | All genomic DNA in sample |

| PCR Amplification | Required (potential source of bias) | Not required (PCR-free) |

| Read Depth for Targets | High (due to amplification) | Variable (depends on abundance) |

| Reference Database Dependency | High (for marker gene sequences) | Very High (for whole genomes) |

| Primary Output | Taxonomic profile | Genomic and functional potential |

Performance Comparison for Parasite Detection

Sensitivity and Taxonomic Resolution

Studies directly comparing these methods for parasite detection reveal divergent performance characteristics. Targeted metagenomics typically demonstrates higher sensitivity for detecting low-abundance parasites because PCR amplification enriches target sequences [40]. However, this sensitivity comes with significant limitations—primers may preferentially amplify certain taxa while missing others due to sequence mismatches, potentially leading to false negatives [41] [42].

Shotgun metagenomics can detect a broader spectrum of parasites without amplification bias but requires deeper sequencing to detect low-abundance organisms [28] [42]. A dietary study on pipefishes found that metabarcoding identified a dominant prey species (a proxy for parasite detection), while shotgun metagenomics revealed additional related species, suggesting that amplification bias in metabarcoding can obscure true diversity [42].

Quantitative Accuracy

Both methods face challenges in accurately quantifying parasite loads. Targeted metagenomics is considered semi-quantitative due to PCR amplification biases and variations in gene copy numbers [40]. For instance, the 18S rRNA gene copy number varies significantly across different parasitic species, distorting abundance measurements [40].

Shotgun metagenomics provides better relative abundance estimates by avoiding PCR bias, but results are still influenced by genome size variations [40]. Species with larger genomes contribute more DNA and thus appear more abundant, requiring normalization for accurate quantification [40].

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Parasite Detection

| Performance Metric | Targeted Metagenomics | Shotgun Metagenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Sensitivity | High for targeted groups (with amplification) | Lower for rare species (without enrichment) |

| Taxonomic Scope | Limited to primer specificity | Broad, all domains of life |

| Quantitative Accuracy | Semi-quantitative (affected by PCR bias, gene copy number) | Better relative abundance (affected by genome size) |

| Ability to Detect Novel Species | Limited by primer binding sites | Possible with adequate sequencing depth |

| Reference Database Completeness | Critical (but smaller database needed) | Extremely Critical (large, incomplete databases) |

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Laboratory Workflows

Targeted Metagenomics Workflow:

- DNA Extraction: Use kits designed for the sample type (e.g., stool, blood, tissue) [42]. Methods must be optimized for breaking resistant structures like fungal spores [39].

- Primer Selection: Choose primers based on target parasites. For broad eukaryotic detection, 18S rRNA primers like FF390/FR1 (amplicon ~330bp) provide good coverage [41]. For specific groups, use tailored primers (e.g., for Cryptomycota) [41].

- Library Preparation: Amplify target region with PCR, incorporating adapters for sequencing. Minimize PCR cycles to reduce bias [43].

- Sequencing: Perform on Illumina MiSeq or comparable platforms (2×300 bp for longer amplicons) [36].

Shotgun Metagenomics Workflow:

- DNA Extraction: Use methods yielding high-molecular-weight DNA (≥1kb) [40]. Quantity and quality are critical for library construction.

- Library Preparation: Fragment DNA, repair ends, and ligate adapters without target enrichment [44] [43].

- Sequencing: Requires high-output platforms (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq) for sufficient depth [36].

Bioinformatics Analysis

Targeted Metagenomics Analysis:

- Process raw sequences (demultiplex, quality filter, merge paired-end reads)

- Cluster sequences into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) or Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs)

- Classify taxa using reference databases (e.g., PR2, SILVA) with tools like QIIME2 [39]

Shotgun Metagenomics Analysis:

- Perform quality control and host DNA depletion

- Assemble reads into contigs using tools like MEGAHIT [28]

- Classify using genome-based tools (Kraken2) or assemble metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) with MetaBAT [28]

Figure 1: Comparative Workflows for Parasite Detection. Targeted metagenomics uses PCR to amplify specific marker genes like 18S rRNA, while shotgun metagenomics sequences all DNA without target-specific amplification.

Research Reagent Solutions and Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Metagenomic Parasite Detection

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Reagents | DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit [44] | Standardized DNA extraction from various samples |

| 18S rRNA Primers | nu-SSU-1333-5'/nu-SSU-1647-3′ (FF390/FR1) [41] | ~330bp amplicon covering V4-V5 regions, good fungal coverage |

| Blocking Oligonucleotides | Taxon-specific blocking oligos [41] | Reduce co-amplification of non-target eukaryotes |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina MiSeq (targeted), NovaSeq (shotgun) [36] | Platform choice depends on required depth and read length |

| Bioinformatics Tools | BROCC [39], PGIP [28], Kraken2 [28] | Taxonomic classification tools for parasite identification |

Applications in Parasitology Research

Targeted metagenomics excels in large-scale biodiversity surveys and clinical screening for known parasites where cost-effectiveness and high sensitivity are priorities [1] [40]. Its application is particularly valuable for detecting parasitic infections in stool samples, where traditional microscopy has limited sensitivity [1].

Shotgun metagenomics is indispensable for discovering novel parasites, investigating outbreak strains, and understanding functional potential like drug resistance mechanisms [1] [28]. This approach successfully identified Dirofilaria repens in Colombia for the first time, demonstrating its power for detecting emerging pathogens [1].

Figure 2: Decision Framework for Method Selection. The choice between targeted and shotgun metagenomics depends on multiple factors including research goals, sample quality, and available resources.

Targeted metagenomics and shotgun metagenomics offer complementary approaches for parasite detection using deep sequencing technologies. Targeted metagenomics provides a cost-effective, sensitive method for identifying known parasites in large sample sets, making it ideal for clinical screening and biodiversity monitoring [40]. Shotgun metagenomics offers a comprehensive, unbiased approach capable of discovering novel pathogens and revealing functional characteristics, albeit at higher cost and computational requirements [28] [40].

For researchers designing parasite detection studies, the optimal approach depends on specific research questions, sample types, and available resources. As reference databases expand and sequencing costs decrease, hybrid approaches and integrated bioinformatics platforms like PGIP [28] will further enhance parasitic disease research, surveillance, and clinical diagnostics.

Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) for High-Resolution Genetic Characterization

Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) has emerged as a transformative technology in infectious disease research, providing unprecedented resolution for characterizing pathogens. For parasitic diseases, WGS enables high-resolution typing that surpasses traditional methods like microscopy, serology, and targeted molecular assays [45] [1]. By delivering comprehensive genomic data in a single assay, WGS facilitates the detection of co-infections, identification of imported parasite strains, and discovery of drug resistance markers—critical applications for both clinical management and public health surveillance [46]. The technology has evolved through multiple generations, from first-generation Sanger sequencing to modern next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms that can sequence millions of DNA fragments in parallel, dramatically reducing costs while increasing throughput [47]. This guide objectively compares WGS performance against alternative genomic approaches, examining their respective capabilities for genetic characterization of parasites in research settings.

Technology Comparison: WGS Versus Alternative Sequencing Approaches

Head-to-Head Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Genomic Sequencing Approaches for Parasite Characterization

| Parameter | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) | Targeted Sequencing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Coverage | Complete genome (coding + non-coding) | Protein-coding regions only (~1-2% of genome) | Pre-defined genomic regions |

| Variant Detection Range | SNVs, indels, structural variants, copy number variants, regulatory variants | Primarily coding SNVs and small indels | Limited to targeted markers |

| Diagnostic Yield (Pediatric Rare Disease Cohort) | 68.1% (primary & secondary findings) [48] | 30.6% (primary diagnoses) [48] | Not applicable |

| Ability to Detect Novel Variants | High | Moderate | Limited to known targets |

| Best Applications | Outbreak investigation, transmission tracking, drug resistance surveillance, population genomics | Diagnosis of known hereditary disorders, variant screening in coding regions | High-throughput screening of specific markers, field surveillance |

| Key Limitations | Higher computational requirements, more complex data interpretation | Misses non-coding and structural variants | Limited by prior knowledge of targets |

WGS Versus WES: Diagnostic Superiority in Clinical Contexts

A direct patient-level comparison demonstrates WGS's superior diagnostic capability. In a prospective study of 72 pediatric patients with suspected genetic disorders, WGS provided diagnostic or secondary findings in 68.1% of cases, more than doubling WES's primary diagnostic rate of 30.6% [48]. WGS exclusively identified diagnoses in 37.5% of patients, resolving complex phenotypes and detecting variant types consistently missed by WES, including deep intronic, regulatory, and structural variants [48]. This performance advantage extends to parasite research, where WGS comprehensively characterizes the full genomic landscape of pathogens rather than just preselected regions.

Advantages Over Traditional Pathogen Characterization Methods

WGS offers significant improvements over conventional parasitic diagnostic methods. Microscopy and rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) lack sensitivity for low-density infections and cannot differentiate between parasite species with similar morphology [46]. In contrast, WGS can identify all six malaria species causing human disease and detect co-infections, with one study of 9,321 clinical isolates identifying co-infections in 4.8% of samples [46]. Unlike PCR-based genotyping methods that target limited genomic regions, WGS provides genome-wide data enabling high-resolution transmission tracking and population studies [45].

Experimental Data: WGS Performance Across Studies

Reproducibility and Concordance Between Analysis Pipelines

Table 2: Inter-Pipeline Variability in WGS Analysis (SNP-based Pipelines)

| Performance Metric | European Sample (NA12878) | African Sample (NA19240) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Variants Identified | 9,120,618 | 16,293,639 | Autosomes + X chromosome [49] |

| Biallelic SNPs | 6,464,817 (91.8% of biallelic variants) | 11,802,101 (93.2% of biallelic variants) | [49] |

| Pipeline Variability (max/min ratio) | 1.3-3.4 | 1.3-3.4 | Higher for indels [49] |

| Average Call Concordance Between Pipelines | 58.1% (SNPs), 34.1% (indels) | 40.1% (SNPs), 25.0% (indels) | [49] |

| Key Influencing Factors | Minor allele frequency, repetitive elements, GC content, coverage depth | Minor allele frequency, repetitive elements, GC content, coverage depth | [49] |

The remarkable difference in variant calls between analytical pipelines highlights the importance of standardized bioinformatics approaches. A comprehensive evaluation of 70 analytic pipelines (combining 7 short-read aligners and 10 variant calling algorithms) found that variant call sets clustered more closely by variant calling algorithms than by aligners [49]. Concordance rates were significantly higher for common variants than for rare variants, with pipelines performing more consistently on the European genome than the African genome, underscoring the need for diverse reference datasets [49].

WGS for Parasite Surveillance and Drug Resistance Monitoring

In parasitology, WGS has demonstrated exceptional utility for large-scale surveillance applications. The Malaria-Profiler tool, which utilizes WGS data, can rapidly predict Plasmodium species, geographical origin, and antimalarial drug resistance profiles across thousands of samples [46]. In an analysis of 7,462 P. falciparum isolates, the tool identified resistance markers for chloroquine (49.2%), sulfadoxine (83.3%), pyrimethamine (85.4%), and markers associated with partial artemisinin resistance (30.6% in Southeast Asian samples) [46]. The geographical prediction accuracy was high at both continental (96.1%) and regional (94.6%) levels, demonstrating WGS's utility for tracking imported malaria cases [46].

Methodological Protocols: WGS in Practice

Standardized WGS Wet-Lab Procedures

Wet-Lab Workflow Diagram

Reproducible WGS requires strict adherence to established laboratory protocols. The process begins with sample collection (blood, saliva, or dried blood spots for clinical parasites), followed by DNA extraction using commercial kits such as QIAamp DNA Mini Kit or Gentra Puregene Blood Extraction Kit [50] [48]. For library preparation, PCR-free methods are preferred to minimize bias, with platforms like Illumina DNA PCR-Free Prep providing optimal results [51]. Sequencing typically occurs on Illumina platforms (NovaSeq 6000 or HiSeq 2500) with a minimum coverage of 30x for WGS and 20x for WES to ensure variant calling accuracy [48]. Quality control measures include monitoring PhiX control error rates (<1%) and assessing sample coverage breadth (>95% for SNP pipelines) [50] [51].

Bioinformatics Pipelines for Parasite WGS Data