Comparative Transmission Dynamics of Parasite Genera: From Molecular Mechanisms to Global Health Implications

This article synthesizes current research on the transmission dynamics of diverse parasite genera, addressing critical gaps between ecological theory and applied disease control.

Comparative Transmission Dynamics of Parasite Genera: From Molecular Mechanisms to Global Health Implications

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the transmission dynamics of diverse parasite genera, addressing critical gaps between ecological theory and applied disease control. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, it explores foundational ecological principles of parasite transmission, examines advanced methodological approaches for tracking and quantifying transmission, discusses optimization strategies for overcoming diagnostic and control challenges, and provides rigorous validation through comparative case studies across key genera. By integrating perspectives from wildlife, human, and veterinary parasitology, this review aims to inform more effective and sustainable intervention strategies in an era of global change.

Ecological Principles and System Complexity in Parasite Transmission

Parasite transmission is not a single event but a complex, multi-stage process that fundamentally determines epidemiological dynamics and virulence evolution [1]. Understanding this process requires deconstructing the journey of a parasite from an infected host to a new susceptible host into distinct, definable stages. Each stage possesses its own unique constraints, selective pressures, and metrics for success, which collectively shape the parasite's overall fitness [1]. This framework moves beyond oversimplified models, such as the basic reproductive number (R0), by incorporating the critical role of individual heterogeneity and the environment outside the host. By dissecting transmission into its component stages—within-host infectiousness, between-host survival, and new host infection—researchers can identify precise intervention points and better predict parasite evolutionary trajectories [1]. This guide objectively compares the transmission dynamics of different parasite genera, synthesizing experimental data and methodologies to provide a resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

A Conceptual Framework for Deconstructing Transmission

A modern framework for analyzing parasite transmission proposes its division into three consecutive stages, each with a specific metric [1]:

- Within-Host Infectiousness (TA): This stage quantifies the production rate of transmissible parasite stages (e.g., spores, larvae, cells) within the primary host. The key metric is the number of parasites released from the host, influenced by factors like parasite load and infection duration.

- Between-Host Transmission Potential (Tp): This intermediate stage covers the survival of parasites in the environment (abiotic or biotic) before reaching a new host. The metric is the number of parasites surviving this period, determined by environmental conditions and parasite durability.

- New Host Infection Success (V): This final stage measures the successful establishment of an infection in a secondary host. The metric is the realized transmission success, which depends on host susceptibility, parasite infectivity, and the initial infectious dose.

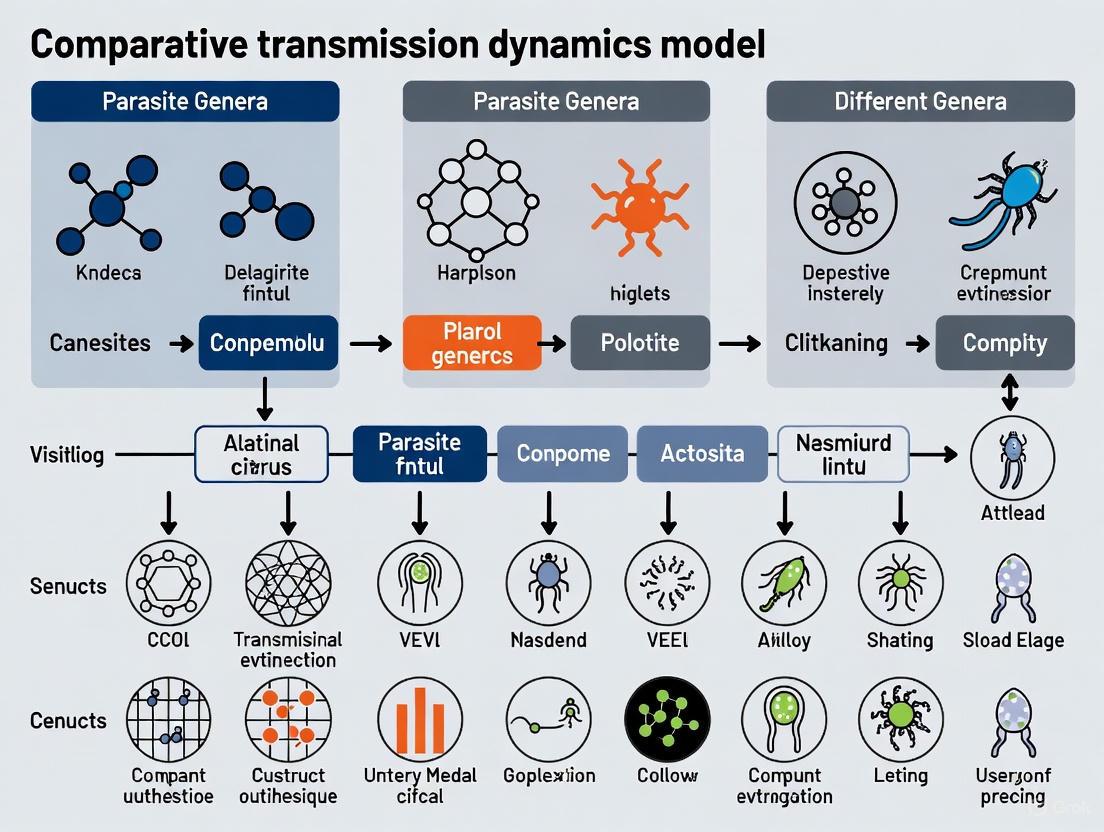

The following diagram illustrates the flow and key influences throughout this multi-stage process.

Comparative Analysis of Transmission Dynamics Across Parasite Genera

The defined framework reveals critical differences in how distinct parasites navigate the transmission process. The following case studies from empirical research highlight these comparative dynamics.

Case Study 1: Sea Lice (Lepeophtheirus salmonis) on Salmonids

Sea lice are ectoparasitic copepods that illustrate a complex, environmentally-mediated transmission pathway, significantly amplified by aquaculture practices [2] [3] [4].

Experimental Protocol for Field Quantification:

- Study Design: Field sampling along wild salmon migration corridors, both near to and distant from salmon farms [2].

- Host Sampling: Juvenile pink (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) and chum (Oncorhynchus keta) salmon were captured via beach seine at 1-4 km intervals along migration routes [2].

- Data Collection: Non-lethal visual inspection of individual fish using 10x magnification hand lenses to count and classify lice life stages (copepodid, chalimus, motile) [2].

- Spatial Modeling: A one-dimensional advection-diffusion model was used to calculate the infection pressure from farms relative to ambient background levels, correlating lice abundance with distance from the source [2].

Quantitative Data on Infection Pressure:

Table 1: Measured Transmission Dynamics of Sea Lice from Farm to Wild Salmon

| Transmission Metric | Parasite Stage | Quantitative Finding | Spatial Scale of Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infection Pressure (TA) | Planktonic copepodids | Farm source was 10,000x (10^4) greater than ambient levels [2] | Elevated levels detected up to 30 km along migration routes [2] |

| Peak Infection Pressure | Planktonic copepodids | Maximum pressure near farm was 73x greater than ambient levels [2] | Concentrated near farm site [2] |

| Composite Pressure (with 2nd Generation) | All stages | Increased by an additional order of magnitude [2] | Exceeded ambient levels for 75 km [2] |

| Wild Host Vulnerability | Motile lice | Juvenile pink/chum salmon are highly vulnerable due to thin skin and lack of scales [3] | Affects entire migratory host cohort [4] |

Case Study 2: Feather Lice on Rock Pigeons

Feather lice (Insecta: Phthiraptera) are permanent, host-specific parasites that demonstrate a trade-off between competitive ability and dispersal (transmission) capability, tested through controlled experiments [5].

Experimental Protocol for Transmission Mechanics:

- Study System: Two competing lice genera on Rock Pigeons (Columba livia): the competitively inferior wing louse (Columbicola columbae) and the competitively superior body louse (Campanulotes compar) [5].

- Hypothesis: Based on competition-colonization trade-off models, the inferior competitor (wing louse) should be a superior disperser [5].

- Experimental Tests:

- Vertical Transmission: Comparing lice transmission from adult pigeons to their nestlings in captive populations [5].

- Horizontal Transmission (Phoresy): Evaluating the ability of wing lice and body lice to hitchhike on parasitic flies (Pseudolynchia canariensis) to disperse to new hosts in both captive and wild birds [5].

Quantitative Data on Dispersal Trade-Offs:

Table 2: Comparative Transmission Success Between Competing Lice Species

| Transmission Mechanism | Wing Louse (C. columbae) | Body Louse (C. compar) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vertical Transmission | Significantly greater transmission to nestlings [5] | Lower transmission to nestlings [5] | Wing lice are more effective at direct, contact-based colonization |

| Phoresy (on flies) | Highly capable of phoretic transmission [5] | Non-phoretic; does not hitchhike on flies [5] | Wing lice have a specialized, long-range dispersal mechanism |

| Competitive Ability | Competitively inferior [5] | Competitively superior [5] | Confirms the competition-colonization trade-off |

Case Study 3: Blood Bacteria in Desert Rodents

The rodent-bacteria system in the Negev Desert provides insights into how host heterogeneity and specific host-parasite interactions shape within-host infection dynamics, influencing transmission potential (TA) [6].

Experimental Protocol for Dissecting Host-Parasite Specificity:

- Study Organisms: Three rodent species (Gerbillus andersoni, G. gerbillus, G. pyramidum) inoculated with two bacterial pathogens (Bartonella krasnovii and Mycoplasma haemomuris-like bacterium) [6].

- Host Preparation: Non-reproductive adult male rodents from a lab colony, confirmed pathogen-free prior to inoculation, were used to control for variability [6].

- Infection Dynamics Monitoring: Following inoculation, blood samples were taken regularly (e.g., every 9-11 days for Bartonella) and analyzed via molecular methods to quantify infection load and duration during primary infection and reinfection [6].

- Hypothesis Testing: The experiment tested the "host trait variation" hypothesis (similar pathogen performance across hosts) versus the "specific host-parasite interaction" hypothesis (unique dynamics for each pair) [6].

Key Finding: Both pathogens showed reduced performance in G. gerbillus, supporting a general host effect. However, all other aspects of the infection dynamics (e.g., duration, load) exhibited unique trends for each host-parasite pair, underscoring that transmission dynamics emerge from specific interactions rather than host traits alone [6]. This specificity must be considered when modeling transmission stages.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Research into parasite transmission stages relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details essential tools for experimental work in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Transmission Studies

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Emamectin Benzoate (SLICE) | Chemical control therapeutic for sea lice [7] [4] | Used in salmonid studies to create refugia or control lice populations on farmed hosts, allowing measurement of subsequent effects on wild populations [4]. |

| Cleaner Fish (e.g., Wrasse, Lumpfish) | Biological control agents for ectoparasites [7] | Deployed in salmon net-pens as a non-chemical method for reducing sea lice loads, constituting an integrated pest management strategy [7]. |

| Molecular Assays (qPCR, DNA sequencing) | Pathogen detection, load quantification, and strain identification [6] | Used to monitor within-host infection dynamics (e.g., Bartonella and Mycoplasma loads in rodent blood) and confirm host pathogen-free status prior to experiments [6]. |

| Hydrolab Quanta Meter | Measures environmental parameters (temperature, salinity) [2] | Characterizes the abiotic environment during field studies of sea lice, as louse survival and transmission are influenced by these factors [2] [4]. |

| Beach Seine Net | Capture of wild juvenile salmonids for non-lethal sampling [2] | Enables spatial sampling of migratory hosts along migration corridors to map parasite abundance and distribution relative to point sources like farms [2]. |

| Preserved Infected Blood | Source of uncultivable pathogens for experimental inoculation [6] | Essential for studying pathogens like Mycoplasma haemomuris, which cannot be cultured in vitro, allowing for controlled laboratory infections [6]. |

Deconstructing parasite transmission into discrete stages—within-host infectiousness, between-host survival, and new host establishment—provides a powerful, granular framework for comparative analysis. The case studies examined here demonstrate that the relative importance of each stage, and the factors governing it, vary profoundly across parasite genera and systems. In sea lice, the environmental stage and host density are paramount; in feather lice, behavioral and morphological adaptations for dispersal define transmission success; and in rodent blood bacteria, the specific molecular dialogue between host and parasite dictates within-host dynamics and thus transmissibility. For researchers and drug developers, this staged framework offers a strategic roadmap. It identifies vulnerable points in the parasite's life cycle for targeted intervention, predicts how control measures might exert selective pressure, and underscores the necessity of developing tools and models that account for the unique transmission biology of each pathogen. Future research that quantitatively links metrics across all three stages will be crucial for a predictive understanding of parasite spread and evolution.

Global change, encompassing climate shift, pollution, and land-use transformation, is fundamentally reshaping the transmission dynamics of parasitic diseases. Vector-borne diseases continue to pose significant threats to public health globally, with climate change exacerbating their transmission dynamics and expanding their geographic range [8]. These changes are creating complex, interconnected challenges for disease control efforts worldwide. The intricate relationships between environmental drivers, vector biology, pathogen development, and host interactions create evolving epidemiological patterns that demand sophisticated comparative analysis. Understanding these shifting dynamics is critical for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working to develop effective interventions in a rapidly changing world.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of how global change factors differentially affect transmission dynamics across major parasite genera, synthesizing experimental data and methodological approaches to inform future research and intervention strategies. The complex interactions between vectors, pathogens, hosts, and the changing environment underscore the urgent need for integrated approaches to disease control [8].

Comparative Tables: Transmission Dynamics Under Global Change

Table 1: Climate Change Impacts on Geographic Distribution of Vector-Borne Diseases

| Parasite/Vector System | Current Suitable Area | Projected Future Expansion | Key Climate Drivers | Population at Risk (Current/Projected) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anopheles stephensi (malaria vector) | 13% of Earth's land surface (17M km²) [9] | >30% by 2100 [9] | Temperature, urbanization | 2.37B / 4.73-5.78B by 2100 [9] |

| Malaria in Papua New Guinea | 61% of population (2010-2019) [10] | 74% by 2040 (+2.8M people) [10] | Warming temperatures | Additional 2.8M people by 2040 [10] |

| Triatomine bugs (Chagas disease) | Stable current distribution [11] | Significant shift to Amazon by 2080 [11] | Temperature, precipitation | Focus on Amazon's socioeconomically vulnerable [11] |

Table 2: Differential Urban-Rural Transmission Pathways Under Climate Change

| Transmission Factor | Urban Environments | Rural Environments |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Transmission Dynamics | Infrastructure-mediated [12] | Ecosystem-mediated [12] |

| Key Breeding Sites | Drainage systems, water storage containers, artificial habitats [12] | Natural water bodies, agricultural sites, riverine habitats [12] |

| Climate Amplification Effects | Heat island effects exceed vector survival thresholds [12] | Agricultural breeding sites, seasonal spillover from wildlife [12] |

| Epidemiological Patterns | Density-driven epidemic spread affecting healthcare surge capacity [12] | Healthcare accessibility challenges during extreme weather events [12] |

| Intervention Challenges | Infrastructure vulnerabilities, population density [12] | Diverse vector communities, limited healthcare access [12] |

Table 3: Molecular Mechanisms in Vector-Pathogen Interactions Under Changing Conditions

| Vector-Pathogen System | Key Molecular Pathways | Experimental Findings | Functional Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Haemaphysalis longicornis tick and Babesia microti [8] | Apoptosis and autophagy pathways [8] | B. microti infection significantly upregulates genes associated with cellular processes in tick midgut tissues [8] | Silencing of caspase-7, caspase-9, and ATG5 genes reduces parasite burden [8] |

| Tomato-potato psyllid and Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum [8] | Organ-specific gene expression patterns [8] | Salivary glands show enrichment in neuronal transmission, cell adhesion; ovaries exhibit changes in DNA replication, stress responses [8] | Distinct transcriptional signatures contribute to horizontal and vertical transmission [8] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Ecological Niche Modeling for Vector Distribution Projections

Protocol Application: This methodology was employed to assess future global distribution and climatic suitability of Anopheles stephensi [9] and potential geographic displacement of Chagas disease vectors [11].

Modeling Framework:

- Algorithms: Utilize ensemble forecasting with multiple algorithms (Maxent, Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, Bayesian Gaussian) [11]

- Climate Scenarios: Apply Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP2-4.5 moderate warming, SSP5-8.5 high emissions) [9] [11]

- Temporal Projections: Model distributions for 2050 and 2080 based on current climate baselines (1970-2000) [11]

Data Requirements:

- Occurrence Records: Compile spatially unique occurrence points (e.g., 11,640 triatomine records) [11]

- Environmental Variables: Process 19 bioclimatic variables via Principal Component Analysis (retaining components explaining ≥95% variance) [11]

- Validation: Use Jaccard threshold to minimize omission and commission errors [11]

Temperature-Dependent Basic Reproduction Number (R₀) Modeling

Protocol Application: This approach was used to assess changes in malaria transmission suitability across Papua New Guinea [10].

Model Implementation:

- Temperature Data: Acquire monthly minimum and maximum temperature data at 2.5 arcmin resolution [10]

- R₀ Calculation: Apply temperature-dependent basic reproduction number model integrating vector and parasite biology [10]

- Transmission Thresholds: Define areas "at risk" using R₀ > 0.1 threshold [10]

- Intervention Impact: Analyze incidence reduction in relation to R₀ values [10]

Key Parameters:

- Transmission Range: 17-33°C, with optimum at 25°C [10]

- Integration Factors: Biting rate, survival rates, and other vector and parasite biological components [10]

Molecular Analysis of Vector-Pathogen Interactions

Protocol Application: Used to investigate role of apoptosis and autophagy pathways in tick-Babesia interactions [8].

Methodological Workflow:

- Transcriptomic Analysis: Conduct RNA sequencing of vector tissues following pathogen infection [8]

- Pathway Identification: Identify significantly upregulated genes and pathways in infected vs. control tissues [8]

- Functional Validation: Implement RNA interference to silence candidate genes and quantify impact on parasite burden [8]

Experimental Controls:

- Tissue Specificity: Compare transcriptomic changes across different vector organs (salivary glands, ovaries, midgut) [8]

- Temporal Dynamics: Assess gene expression at multiple timepoints post-infection [8]

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Vector-Pathogen Interaction Pathways

Recent research has revealed sophisticated molecular interactions between vectors and pathogens that are influenced by environmental factors. In the Asian longhorned tick (Haemaphysalis longicornis) infected with Babesia microti, transcriptomic analysis reveals significant upregulation of genes associated with apoptosis and autophagy pathways in tick midgut tissues [8]. Functional validation using RNA interference demonstrates that silencing of caspase-7, caspase-9, and ATG5 genes effectively reduces parasite burden, highlighting the pro-parasitic roles of these pathways in facilitating infection [8].

In plant systems, the tomato-potato psyllid (Bactericera cockerelli) shows organ-specific transcriptomic changes when infected with Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum [8]. Salivary glands exhibit enrichment in processes related to neuronal transmission, cell adhesion, and respiration, while ovaries show changes in DNA replication, transcriptional regulation, and stress responses [8]. These distinct transcriptional signatures contribute to horizontal and vertical transmission of pathogens, providing potential targets for intervention strategies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Transmission Dynamics

| Reagent/Material | Primary Application | Specific Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Card Agglutination Test for Trypanosomiasis (CATT) [13] | Field screening for gHAT | Serological detection of Trypanosoma brucei gambiense antibodies | Initial population screening in DRC elimination programs [13] |

| Mini Anion Exchange Centrifugation Technique (mAECT) [13] | gHAT diagnosis | Parasite concentration and microscopic visualization | Confirmatory testing after CATT positive results [13] |

| RNA Interference (RNAi) Reagents [8] | Molecular pathway analysis | Targeted gene silencing in vector species | Functional validation of caspase and ATG genes in tick-pathogen interactions [8] |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Platforms [8] | Transcriptomic analysis | Genome-wide expression profiling | Identification of differentially expressed genes in vector tissues [8] |

| Species Distribution Modeling Algorithms [9] [11] | Ecological niche modeling | Prediction of vector distribution under climate scenarios | Projecting future range of Anopheles stephensi and triatomine bugs [9] [11] |

| Temperature-Controlled Insectaries [10] | Vector biology studies | Maintaining colonies under precise climatic conditions | Investigating thermal optima for parasite development [10] |

The comparative analysis of transmission dynamics across parasite genera reveals both shared patterns and distinct mechanisms in response to global change factors. Climate change emerges as a primary driver of geographic range expansion for multiple vector-borne diseases, with warming temperatures enabling altitudinal and latitudinal spread [10] [9]. The complex interactions between climate variables, vector biology, pathogen development, and host interactions create evolving epidemiological patterns that demand sophisticated surveillance and intervention approaches [8].

Future research should focus on developing predictive models that incorporate climate data to forecast disease outbreaks, identifying novel molecular targets for transmission-blocking interventions, enhancing surveillance systems using advanced technologies like NGS, and implementing community-based educational programs to improve public awareness and engagement [8]. As climate change continues to reshape the landscape of vector-borne diseases, interdisciplinary research and global collaboration will be essential to mitigate impacts on public health, agriculture, and ecosystems [8]. The distinct transmission pathways in urban versus rural environments further highlight the need for settlement-specific prevention strategies and healthcare preparedness approaches [12].

Parasites employ a remarkable array of strategies to survive and proliferate within their hosts, engaging in a complex molecular arms race that has shaped evolutionary pathways across species. The core of this battle revolves around three fundamental processes: within-host development (the parasite's life cycle progression), immune evasion (the parasite's ability to avoid host defenses), and resource sequestration (the parasite's mechanisms for nutrient acquisition). Understanding these interconnected strategies is crucial for developing novel therapeutic interventions against parasitic diseases that continue to cause significant global morbidity and mortality. This review synthesizes current knowledge of the comparative mechanisms employed by major parasite genera, providing a foundation for identifying vulnerable points in parasite biology that can be targeted for drug development.

Comparative Immune Evasion Strategies Across Parasite Genera

Parasites have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to evade host immune responses, which can be broadly classified into passive and active strategies. Passive evasion involves techniques such as hiding in immunoprivileged sites, becoming invisible to immune surveillance through surface component shielding, or changing surface identity through antigenic variation. In contrast, active evasion involves direct interference with the host's immune signaling networks, often through the production of modulatory molecules that disrupt immune cell function or communication [14].

Table 1: Comparative Immune Evasion Mechanisms Across Parasite Genera

| Parasite Genus | Evasion Type | Specific Mechanism | Molecular Players | Effect on Host Immunity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmodium spp. | Passive | Antigenic variation | PfEMP1 proteins (60 variants in P. falciparum) | Avoids antibody-mediated clearance [14] |

| Trypanosoma spp. | Passive | Antigenic variation | VSG coat (hundreds of variants) | Prevents sustained antibody response [14] [15] |

| Plasmodium | Passive | Sequestration in liver | CSP protein binding to heparan sulfate | Evades Kupffer cell surveillance [16] |

| Herpesviruses | Passive | Latency in neurons | Downregulated viral protein synthesis | Escapes T-cell detection [14] |

| Plasmodium | Active | Host cell manipulation | UIS4 protein binding host actin | Prevents autophagy and apoptosis [16] |

| Trypanosoma | Active | General immunosuppression | T-cell exhaustion, B-cell nonspecific activation | Reduces specificity and memory of antibody responses [15] |

| Poxviruses | Active | Complement inhibition | Viral complement control proteins | Blocks inflammatory signaling and cell recruitment [17] |

| Schistosoma | Active | Molecular mimicry | C-type lectins that sequester host recognition tags | Interferes with pathogen recognition [14] |

The diversity of these evasion strategies highlights the evolutionary adaptation of parasites to their specific host niches. Blood-borne parasites like Plasmodium and Trypanosoma rely heavily on antigenic variation, constantly changing their surface proteins to stay ahead of the adaptive immune response [14] [15]. Intracellular parasites, including Plasmodium during its liver stage, manipulate host cell pathways to create safe replicative niches, while large extracellular parasites like helminths employ molecular mimicry and immunosuppressive factors [14] [16].

Within-Host Development and Life Cycle Progression

The complex life cycles of parasites represent sophisticated developmental programs adapted to specific host environments. These developmental pathways are characterized by stage-specific gene expression, morphological changes, and metabolic adaptations that enable survival and replication within the host.

Table 2: Comparative Within-Host Development Across Parasite Genera

| Parasite Genus | Host Entry Point | Key Target Tissues/Cells | Developmental Transitions | Tissue-Specific Adaptations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmodium | Dermis via mosquito bite | Hepatocytes, erythrocytes | Sporozoite → Merozoite → Gametocyte | PVM formation in hepatocytes; antigenic variation in RBCs [16] |

| Trypanosoma brucei | Skin via tsetse fly bite | Blood, lymph, adipose tissue | Metacyclic → Slender → Stumpy forms | Quorum sensing for density regulation; tissue reservoirs [15] |

| Angiostrongylus | Oral (ingestion) | CNS, pulmonary arteries | L3 → Adult worms | Neural tissue tropism (A. cantonensis); vascular residence [18] |

| Trypanosoma cruzi | Skin/mucosa via triatomine feces | Multiple tissues including cardiac | Trypomastigote → Amastigote | Intracellular amastigote replication in various tissues [19] |

The developmental transitions are precisely regulated by both parasite-intrinsic factors and host-derived cues. For example, Trypanosoma brucei undergoes a density-dependent differentiation from replicative "long slender" forms to cell cycle-arrested "short stumpy" forms that are pre-adapted for transmission back to the tsetse fly vector [15]. Similarly, Plasmodium parasites undergo a developmental commitment toward gametocytogenesis, which is essential for transmission to mosquitoes [16]. Recent single-cell transcriptomic studies have revealed that these developmental transitions involve metabolic reprogramming, such as the shift from tricarboxylic acid metabolism to glycolytic metabolism in trypanosomes as they adapt to the mammalian bloodstream environment [15].

Tissue Tropism and Niche Adaptation

Different parasite genera exhibit distinct tissue tropisms that reflect their evolutionary adaptations:

- Neurological tropism: Angiostrongylus cantonensis preferentially migrates to the central nervous system, causing eosinophilic meningitis in accidental hosts [18]

- Hepatotropism: Plasmodium sporozoites specifically target hepatocytes, forming a protective parasitophorous vacuole membrane (PVM) that facilitates intracellular development [16]

- Dermatotropism: Trypanosoma brucei can establish skin tissue reservoirs that may serve as important transmission niches [15]

- Vascular tropism: Angiostrongylus vasorum resides in the pulmonary arteries and right heart of canids, causing cardiopulmonary disease [18]

Resource Sequestration: Metabolic Parasitism

Parasites must acquire essential nutrients from their hosts while overcoming nutritional immunity—host strategies to limit nutrient availability. The mechanisms of resource sequestration vary dramatically based on parasite localization and metabolic requirements.

Table 3: Nutrient Acquisition Strategies Across Parasite Genera

| Parasite Genus | Key Nutrients Sequestrated | Acquisition Mechanisms | Impact on Host Metabolism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmodium | Iron, lipids, amino acids | Hemoglobin degradation, erythrocyte import channels | Hemozoin formation, anemia [16] |

| Trypanosoma | Iron, carbohydrates | Receptor-mediated uptake, surface transporters | Anemia, hypergammaglobulinemia [15] |

| Angiostrongylus | Lipids, blood components | Direct nutrient uptake from host tissues | Coagulopathies, hemorrhage (A. vasorum) [18] |

| Bacteria (general) | Iron | Siderophore production | Host countermeasure: siderocalin production [17] |

Iron acquisition represents a critical battleground in host-parasite interactions. Plasmodium parasites digest host hemoglobin within their acidic food vacuoles, releasing heme which is subsequently crystallized into hemozoin to prevent oxidative damage [16]. Bacterial pathogens such as Escherichia coli and Bacillus anthracis secrete high-affinity siderophores to scavenge iron from the host environment, while the host counteracts this strategy by producing siderocalin receptors that competitively bind iron [17]. The competition for essential resources extends beyond micronutrients to include carbon sources and lipids, with different parasites evolving specialized transporters and metabolic pathways to exploit host nutrient pools.

Methodologies for Studying Host-Parasite Interactions

Experimental Models and Infection Systems

Research into host-parasite interactions employs diverse experimental models that capture different aspects of the infection dynamic:

- Rodent models: Used for Plasmodium yoelii studies to understand liver stage immunomodulation [16]

- Canine models: Employed for Angiostrongylus vasorum research, particularly for understanding coagulopathies [18]

- Non-human primates: Utilized for Plasmodium transmission blocking studies [16]

- In vitro culture systems: Used for Trypanosoma brucei metabolic studies and Plasmodium liver stage development [16] [15]

Molecular Detection and Quantification Methods

Advanced molecular techniques have revolutionized our ability to detect and quantify parasites within host tissues:

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR): Used for precise quantification of parasite loads, as applied in Trypanosoma cruzi studies in triatomine vectors [19]

- Amplicon next-generation sequencing: Employed for high-resolution haplotype analysis of Plasmodium falciparum infections in epidemiological studies [20]

- Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq: Reveals heterogeneity in both parasite populations and host immune responses, as demonstrated in Trypanosoma brucei tissue reservoirs [15]

- Spatial transcriptomics: Maps host and parasite gene expression within tissue architecture [15]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Studying Host-Parasite Interactions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Parasite Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Detection Primers/Probes | T. cruzi satellite DNA primers; Plasmodium 18S rRNA probes | Parasite detection and quantification in host tissues/vectors [19] | Trypanosoma cruzi, Plasmodium spp. |

| Genetic Markers for Typing | Plasmodium csp and ama1 gene targets; T. cruzi mini-exon targets | Genotype discrimination, transmission tracking, population genetics [19] [20] | Plasmodium falciparum, Trypanosoma cruzi |

| Cell Surface Markers | Antibodies to CD4, CD8, MHC molecules | Host immune response profiling by flow cytometry | Trypanosoma brucei, Plasmodium spp. |

| Cytokine Detection Assays | IL-12, IL-10, TNF-α, TGF-β ELISAs; multiplex cytokine panels | Quantifying host inflammatory and regulatory responses [16] | Plasmodium spp., Trypanosoma spp. |

| Metabolic Tracers | Stable isotope-labeled nutrients (e.g., 13C-glucose) | Tracking nutrient uptake and utilization by parasites | Trypanosoma brucei, Plasmodium spp. |

Implications for Therapeutic Development

Understanding the molecular basis of host-parasite interactions opens new avenues for therapeutic intervention. Several key strategies emerge from comparative analysis:

Targeting Immune Evasion Mechanisms

The precise molecular mechanisms parasites use to evade immunity represent attractive drug targets:

- Inhibition of antigenic variation: Small molecules that disrupt the expression or switching of VSG genes in trypanosomes or PfEMP1 in Plasmodium could render parasites vulnerable to host immunity [14] [15]

- Blocking host cell invasion: Monoclonal antibodies that target Plasmodium circumsporozoite protein (CSP) or thrombospondin-related anonymous protein (TRAP) can prevent hepatocyte invasion [16]

- Counteracting immunosuppression: Agents that reverse trypanosome-induced T-cell exhaustion or B-cell polyclonal activation could restore protective immunity [15]

Disrupting Developmental Transitions

Interrupting the precisely timed developmental programs of parasites represents another promising approach:

- Blocking differentiation signals: Compounds that interfere with quorum-sensing mechanisms in Trypanosoma brucei could prevent transition to transmissible stumpy forms [15]

- Inhibiting stage-specific metabolic pathways: Drugs that target the unique metabolic requirements of liver-stage Plasmodium parasites could prevent establishment of blood-stage infection [16]

Exploiting Metabolic Dependencies

The unique nutritional requirements and acquisition strategies of parasites reveal additional vulnerabilities:

- Iron metabolism inhibitors: Compounds that disrupt heme detoxification in Plasmodium or siderophore utilization in bacteria could limit parasite replication [17] [16]

- Nutrient transporter blockers: Small molecules that specifically parasite surface transporters for essential nutrients could starve parasites without affecting host cells

The comparative analysis of parasite genera reveals both conserved and unique strategies for within-host survival. While the specific molecular mechanisms differ, successful parasites universally navigate three core challenges: developmental programming adapted to host environments, multifaceted immune evasion, and efficient resource acquisition. The increasing application of single-cell technologies, spatial transcriptomics, and high-resolution genotyping is revealing unprecedented detail about these processes, highlighting the remarkable heterogeneity and adaptability of both parasite populations and host responses. Future therapeutic strategies will likely benefit from targeting the intersection points of these three core processes, where parasite vulnerabilities may be most exposed. As we deepen our understanding of the molecular dialogue between hosts and parasites, we move closer to the goal of disrupting these ancient relationships to alleviate the burden of parasitic diseases worldwide.

Parasite transmission is a complex, multi-stage process fundamentally driven by the parasite's need to maximize its reproductive success. The overall transmission rate is a key indicator of parasite fitness, reflecting its ability to infect a host, survive and reproduce within it, and subsequently infect new hosts [21]. To better understand how environmental drivers affect this process, a novel framework breaks transmission into three distinct stages: (1) within-host infectiousness (parasite numbers released), (2) an intermediate between-host stage (parasite survival outside the host), and (3) new host infection (successful establishment in a secondary host) [21]. Each stage is influenced by a dynamic interplay of intrinsic and extrinsic factors—the abiotic (non-living) and biotic (living) components of the environment—that together determine transmission success. This framework provides a structured approach for comparing transmission dynamics across different parasite genera, which is essential for developing targeted control strategies and predicting disease evolution in a changing world.

Comparative Analysis of Transmission Dynamics Across Parasite Genera

The influence of abiotic and biotic factors on transmission varies significantly across different parasite systems. The table below provides a structured comparison of several parasite genera, highlighting key environmental drivers and their impacts on transmission success.

Table 1: Comparative Influence of Abiotic and Biotic Factors on Transmission Across Parasite Genera

| Parasite Genus / Disease | Primary Transmission Route | Key Abiotic Drivers | Key Biotic Drivers | Impact on Transmission Success |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arboviruses (Dengue, Chikungunya) [22] [23] | Vector-borne (Aedes mosquitoes) | Temperature, rainfall patterns, urbanization [22] | Vector abundance, host population immunity, human mobility [22] [23] | Record-breaking heat in 2023 led to higher mosquito abundance, longer active season, and increased outbreak risk in Southern Europe [22]. |

| Trypanosoma cruzi (Chagas disease) [19] | Vector-borne (triatomine bugs) | Land use, housing quality (e.g., dog kennels) [19] | Reservoir hosts (dogs, wildlife), vector blood-feeding sources [19] | High parasite prevalence (81-100%) in vectors from dog kennels; dogs and humans identified as key blood-meal sources, supporting local transmission cycles [19]. |

| Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease) [24] | Vector-borne (Ixodes ticks) | Temperature, humidity [24] | Competent vector presence (ticks), reservoir hosts (rodents, birds) [24] | Mosquitoes experimentally ruled out as vectors; ticks are sole competent vectors, emphasizing the critical biotic driver of vector competence [24]. |

| Schistosoma mansoni [25] | Water-borne (snail intermediate host) | Water contamination, sanitation infrastructure [25] | Human migration, snail host presence, host immunity [25] | Genetic analyses reveal population structure tied to human communities, with occasional long-range migration connecting seemingly isolated outbreaks [25]. |

| General Parasite Models [21] | Variable | Host nutritional status, environmental conditions outside host [21] | Host immunity (resistance/tolerance), parasite load, host behavior (superspreading) [21] | Framework proposes that constraints at any transmission stage (e.g., resource competition within host, survival outside host) impact overall fitness [21]. |

Detailed Experimental Data and Methodologies

Understanding the comparative data presented above requires a deep dive into the experimental approaches that generate this knowledge. The following sections detail the protocols and reagents that form the backbone of research in this field.

Experimental Protocols in Vector-Borne Disease Research

1. Entomological Surveillance and Population Modeling (Arboviruses)

- Protocol: Adult mosquito collections are conducted using sticky traps (STs) dispersed within a set radius. Traps are replaced weekly, and captured mosquitoes are morphologically identified and counted. This entomological data is used to calibrate a temperature-dependent mosquito population model [22].

- Model Calibration: The model simulates the mosquito life cycle (eggs, larvae, pupae, adults) using a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) approach to estimate site-specific parameters like larval carrying capacity. Daily temperature records serve as a key abiotic input [22].

- Epidemiological Risk Assessment: The simulated mosquito population is incorporated into a standard SEI-SEIR (Susceptible-Exposed-Infectious for mosquitoes / Susceptible-Exposed-Infectious-Recovered for humans) model to compute the basic reproduction number (R₀) and simulate outbreak trajectories [22].

2. Molecular Characterization of Parasite Transmission (Trypanosoma cruzi)

- Field Collection & Morphological Identification: Vectors (triatomine bugs) are collected from field sites like dog kennels using hand collection and black light traps. Taxonomic identification is performed using morphological keys [19].

- DNA Extraction: A combination of mechanical, enzymatic, and automated extraction from the insect's abdominal section ensures high-quality DNA. This involves mechanical disruption with bead lysis, overnight incubation with Proteinase K, and processing on an automated system [19].

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR): Used for sensitive detection and quantification of parasite DNA, targeting a specific satellite DNA region for T. cruzi [19].

- Genotyping by Amplicon Sequencing: A fragment of the mini-exon gene is amplified by PCR and sequenced using Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) to identify Discrete Typing Units (DTUs) [19].

- Blood Meal Analysis: A 215-bp fragment of the 12S rRNA gene is amplified from vector DNA and sequenced via ONT to identify the host species from which the vector fed, revealing transmission networks [19].

3. Vector Competence Experiments (Lyme Disease)

- Acquisition Feeding: Laboratory-reared mosquitoes are allowed to feed on anaesthetized mice infected with Borrelia species. Engorged mosquitoes are dissected at various time points post-feeding [24].

- Artificial Membrane Feeding: An alternative method where mosquitoes feed on a Borrelia-spiked blood meal through a membrane, allowing precise control of parasite dose [24].

- Pathogen Detection in Vectors: Nested PCR and quantitative PCR (qPCR) are used to detect and quantify the presence and load of Borrelia in whole-mosquito homogenates [24].

- Trypsin Inhibition Assay: To investigate the mechanism of parasite clearance, mosquitoes are fed on blood containing a trypsin inhibitor, which blocks the activity of this digestive enzyme [24].

The logical workflow for an integrated study of parasite transmission dynamics, synthesizing these protocols, is visualized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Transmission Dynamics

| Research Reagent / Material | Primary Function in Experimentation | Example Application in Cited Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Sticky Traps (STs) [22] | Passive collection of adult mosquitoes for population surveillance. | Used to monitor abundance and seasonal dynamics of Aedes albopictus in Rome [22]. |

| Black Light Van Traps [19] | Attraction and collection of nocturnal insect vectors. | Employed to collect triatomine bugs (Triatoma sanguisuga) from dog kennels in Texas [19]. |

| BSK-H Medium [24] | In vitro culture and maintenance of pathogenic Borrelia spirochetes. | Used to grow infectious, low-passage strains of B. afzelii, B. burgdorferi, and B. garinii for vector competence experiments [24]. |

| qPCR Reagents & Probes [19] | Sensitive detection and absolute quantification of specific parasite DNA in samples. | Utilized to detect and quantify Trypanosoma cruzi satellite DNA in triatomine vectors, determining prevalence and parasitic load [19]. |

| Oxford Nanopore Sequencing Kits [19] | Long-read, real-time sequencing for genotyping and blood meal analysis. | Applied for amplicon sequencing of the mini-exon gene (for T. cruzi DTU identification) and the 12S rRNA gene (for blood meal host identification) [19]. |

| Microsatellite Markers [25] | Highly polymorphic DNA markers for population genetic and kinship analyses. | Used to uncover cryptic population structure and transmission dynamics of Schistosoma mansoni in Brazilian communities [25]. |

Discussion: Synthesis and Implications for Disease Control

The comparative analysis underscores that successful transmission is never the result of a single factor but arises from the intricate interplay between abiotic and biotic drivers across all stages of the parasite life cycle. The three-stage framework provides a universal scaffold for this analysis [21]. For example, within-host success (Stage 1) is influenced by biotic factors like host immunity and parasite manipulation of host behavior [21]. Survival outside the host (Stage 2) is heavily dependent on abiotic conditions like temperature, which can extend vector seasons or accelerate parasite development [22]. Finally, establishment in a new host (Stage 3) relies on biotic interactions such as vector host preference and the presence of susceptible hosts [19].

This integrated understanding has direct implications for public health and drug development. Control strategies must be multifaceted, targeting the critical drivers at the most vulnerable stage of transmission. For instance, the evidence that mosquitoes are not competent vectors for Lyme disease [24] directs public health communication and resources firmly toward tick surveillance and control. Conversely, the dramatic effect of temperature on arbovirus outbreaks [22] highlights the need for climate-informed surveillance and predictive modeling. Furthermore, identifying key reservoir hosts, like dogs in the T. cruzi cycle [19], points to potential targets for veterinary interventions that could disrupt the transmission chain to humans. For drug development, understanding how abiotic stress shapes host immunity [21] could inform the development of novel therapies or tolerance-inducing vaccines. The genetic connectivity between parasite populations revealed by advanced molecular tools [25] suggests that local control may be undermined by regional migration, arguing for coordinated, large-scale elimination campaigns.

The evolutionary trade-off between virulence and transmission provides a foundational framework for understanding pathogen evolution and remains a cornerstone of disease ecology and evolutionary medicine. This hypothesis, formally introduced over forty years ago, posits that a pathogen's ability to transmit to new hosts is intrinsically linked to the harm it causes to its current host [26] [27]. Pathogens must replicate within a host to produce transmission stages, yet this replication typically damages host tissues, potentially killing the host and terminating further transmission opportunities. This creates an evolutionary balancing act where natural selection is predicted to favor intermediate levels of virulence that maximize pathogen fitness across the host population [27] [28]. This review examines the historical development, empirical evidence, and modern refinements of this central paradigm, providing a comparative analysis of its application across different parasite genera and transmission systems. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for predicting pathogen evolution and developing effective, sustainable disease control strategies.

Historical Development of the Trade-Off Hypothesis

The theoretical foundation of the virulence-transmission trade-off hypothesis was largely established in the early 1980s through the work of Anderson and May, alongside Ewald [27] [29]. Their models demonstrated that parasite fitness, expressed mathematically as the basic reproductive number (R0), depends on both transmission rate and the duration of infection. The canonical R0 expression from susceptible-infected-recovered (SIR) models is:

R0 = βS / (μ + ν + γ)

Where β is the transmission rate, S is the density of susceptible hosts, μ is the background host mortality rate, ν is the virulence (infection-induced mortality rate), and γ is the recovery rate [27]. This equation illustrates the fundamental trade-off: while increased replication may enhance transmission (β), it often shortens the infectious period by increasing host mortality (ν). Anderson and May identified two core trade-offs: (1) between virulence and transmission, and (2) between virulence and host recovery rate [26].

Subsequent theoretical work has expanded these core ideas into a "Hierarchy-of-Hypotheses" (HoH), which differentiates between fitness benefits and fitness costs of virulence and encompasses diverse transmission modes and life-history strategies [26]. The following conceptual diagram illustrates the logical structure of these classical and expanded trade-offs:

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in Virulence-Transmission Trade-Off Theory

| Time Period | Key Theoretical Development | Primary Contributors | Central Concept |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early 1980s | Original Formal Models | Anderson & May; Ewald | Mathematical framework linking transmission rate, virulence, and parasite fitness (R0) |

| 1990s-2000s | Extended Trade-Off Models | Various | Incorporation of multiple infections, within-host dynamics, and specific transmission modes |

| 2010s | Empirical Meta-Analyses | Acevedo et al. | Systematic assessment of empirical support across diverse host-parasite systems |

| Recent (2020s) | Hierarchy-of-Hypotheses Framework | Mideo et al. | Structured differentiation of benefits/costs and expansion beyond classical assumptions |

Comparative Analysis of Trade-Off Dynamics Across Parasite Systems

The manifestation of virulence-transmission trade-offs varies considerably across different parasite taxa and transmission systems. This comparative analysis examines the empirical evidence and model predictions for several pathogen groups, highlighting both consistent patterns and system-specific particularities.

HIV-1: A Paradigm for Trade-Off Dynamics in Human Viruses

HIV-1 provides one of the most compelling case studies for the virulence-transmission trade-off hypothesis in a human pathogen. Research from the Rakai Community Cohort Study in Uganda demonstrated that set-point viral load (SPVL)—a heritable viral trait—directly influences both transmission probability and disease progression. Higher SPVL increases transmission rate to partners but accelerates progression to AIDS, shortening the infectious period [28]. This creates a fitness trade-off predicted to favor intermediate SPVL levels.

Longitudinal data from 1995-2012 revealed that SPVL in this population has been declining, with model predictions indicating stabilising selection toward lower virulence. This evolutionary trajectory is consistent with subtype A (with lower virulence) slowly outcompeting subtype D (associated with faster progression) [28]. The specific relationships between SPVL, transmission, and disease progression from this study are quantified in the following table:

Table 2: HIV-1 Trade-Off Parameters from Ugandan Cohort Study

| SPVL Level (log10 copies/mL) | Transmission Rate (per year) | Time to AIDS (years) | Evolutionary Trend |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (≈2-3) | 0.019 | ~40 | Favored in long-term evolution |

| Intermediate (≈4-5) | 0.04-0.08 | ~10-15 | Traditional predicted optimum |

| High (≈6-7) | 0.14 | ~5 | Selected against despite high infectiousness |

Avian Haemosporidians: Temperature-Driven Dynamics in Wildlife Systems

The transmission ecology of avian blood parasites (genera Plasmodium, Haemoproteus, and Leucocytozoon) in temperate ecosystems illustrates how environmental factors modulate virulence-transmission trade-offs. Mathematical modeling of Leucocytozoon fringillinarum in White-crowned Sparrows revealed that seasonal relapse of chronic infections in adult birds is crucial for parasite persistence across breeding seasons [30]. This system demonstrates two key adaptations: (1) timing of relapse to coincide with vector emergence and susceptible juvenile hosts, and (2) temperature-dependent effects on black fly vectors that ultimately determine transmission efficiency.

Sensitivity analysis of model parameters indicated that parasite prevalence and host recruitment are most affected by seasonal temperature changes that influence black fly emergence and gonotrophic cycles, highlighting the importance of environmental drivers in modifying trade-off dynamics [30].

Malaria Parasites: Genetic Insights into Transmission Heterogeneity

Molecular epidemiological studies of Plasmodium falciparum in high-transmission settings have utilized next-generation sequencing of polymorphic genes (csp and ama1) to elucidate fine-scale transmission dynamics. Research in western Kenya demonstrated significant spatial clustering of genetically similar parasites within households, with symptomatic children serving as hubs for transmission to household members [20].

This system exhibits substantial heterogeneity in transmission, with polygenomic infections being the rule rather than the exception (only 34.7% of infections contained single haplotypes). The persistence of certain haplotypes across multiple seasons (4 csp haplotypes detected in at least 14 of 15 months) while others appeared only sporadically suggests complex interactions between virulence traits, transmission efficiency, and immune evasion [20].

Table 3: Virulence-Transmission Relationships Across Pathogen Systems

| Pathogen System | Transmission Mode | Virulence Metric | Empirical Support for Trade-Off | Unique System Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 | Direct (sexual) | Set-point viral load, time to AIDS | Strong | Heritable viral trait; long infectious period; competition between subtypes |

| Avian Leucocytozoon | Vector (black flies) | Acute mortality, chronic fitness effects | Moderate (model-predicted) | Seasonal relapse crucial; temperature-dependent vector dynamics |

| Human Malaria (P. falciparum) | Vector (mosquitoes) | Severe disease, mortality | Mixed | High genetic diversity; complex immunity; polygenomic infections |

| Various (Meta-Analysis) | Mixed | Variable | Partial | Strong replication-virulence link; inconsistent transmission-virulence relationship |

Methodological Approaches in Trade-Off Research

Experimental Protocols for Quantifying Trade-Off Parameters

Research on virulence-transmission trade-offs employs diverse methodological approaches tailored to specific host-parasite systems. The following core protocols represent standardized methodologies cited across the literature:

4.1.1 Transmission Rate Estimation in Serodiscordant Couple Cohorts

- Application: HIV-1 transmission studies [28]

- Protocol: Follow serodiscordant couples longitudinally, with regular testing of the uninfected partner. Model transmission as a Poisson process where the instantaneous transmission rate (β) is a function of SPVL. Compare models with different functional forms (stepwise vs. continuous) using Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).

- Key Measurements: SPVL in index partner, timing of seroconversion in susceptible partner, covariates (subtype, circumcision status).

- Analysis: Maximum likelihood estimation of transmission parameters; Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for model validation.

4.1.2 Molecular Epidemiology of Parasite Transmission Networks

- Application: Malaria parasite population genetics [20]

- Protocol: Conduct amplicon next-generation sequencing of polymorphic genes (e.g., csp, ama1). Assign haplotypes using quality-filtered reads. Calculate genetic similarity between infected individuals using:

- Binary haplotype sharing (any haplotypes in common)

- Proportional haplotype sharing (percentage of haplotypes in common)

- L1 norm (sequence-based distance)

- Spatial Analysis: Compare haplotype sharing within households versus between households at increasing geographic distances.

4.1.3 Vector-Based Transmission Modeling for Wildlife Systems

- Application: Avian blood parasite dynamics [30]

- Protocol: Develop compartmental models stratified by:

- Bird age classes (nestlings, young of the year, adults)

- Infection status (susceptible, exposed, infectious, recovered/relapsed)

- Vector population dynamics with seasonal emergence

- Parameterization: Field data on prevalence, vector abundance, and host demography

- Sensitivity Analysis: Identify parameters most influencing transmission dynamics and prevalence

Conceptual Framework for Transmission Stage Decomposition

Modern frameworks have decomposed transmission into distinct stages to better understand which factors constrain parasite evolution. The following diagram illustrates this multi-stage process and the factors influencing each stage:

This framework explicitly recognizes that parasites must succeed at multiple stages—within-host infectiousness (parasite numbers released), between-host transmission potential (survival between hosts), and new host establishment (successful infection)—with different factors influencing each stage [21]. Constraints at any single stage can fundamentally alter virulence-transmission relationships.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Virulence-Transmission Studies

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Trade-Off Research | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Genotyping | Amplicon NGS of polymorphic genes (csp, ama1); Viral load quantification (qPCR) | Identify transmission links; quantify heritable virulence traits; assess diversity | Malaria haplotype sharing [20]; HIV SPVL measurement [28] |

| Epidemiological Modeling | SIR models; Individual-based simulations; Network models | Predict evolutionary trajectories; quantify R0; test trade-off hypotheses | HIV optimal virulence prediction [28]; Avian parasite dynamics [30] |

| Longitudinal Cohort Data | Serodiscordant couple cohorts; Household transmission studies; Population surveillance | Measure transmission rates; track virulence evolution; assess natural selection | Rakai HIV cohort [28]; Kenyan malaria study [20] |

| Vector Competence Assays | Membrane feeding; Direct feeding experiments; Vector dissections | Quantify transmission potential; assess vector efficiency | Avian malaria transmission [30]; Black fly vector competence |

| Meta-Analytic Approaches | Individual-patient data meta-analysis; Phylogenetic comparative methods | Assess generalizability of trade-offs; identify knowledge gaps | Acevedo et al. meta-analysis [29] |

The virulence-transmission trade-off hypothesis has evolved from a simple conceptual model to a sophisticated framework incorporating multiple constraints, transmission stages, and system-specific dynamics. While the core premise—that pathogens face evolutionary compromises between exploitation and host survival—remains robust, its manifestation varies dramatically across biological systems. The empirical evidence, from HIV-1's gradual attenuation to the complex seasonal dynamics of avian parasites, demonstrates both the generality and context-dependency of these evolutionary principles.

Contemporary research has moved beyond simply testing for trade-offs to dissecting their mechanistic bases and quantifying their parameters in natural systems. The integration of molecular epidemiology, mathematical modeling, and detailed field studies has revealed the hierarchical nature of these trade-offs and their embeddedness in ecological communities. This more nuanced understanding enables better predictions of pathogen evolution and more targeted interventions aimed at steering this evolution toward less virulent trajectories—a crucial frontier in our ongoing battle with infectious diseases.

Advanced Techniques for Tracking, Quantifying and Modeling Transmission

The study of parasite transmission dynamics relies heavily on advanced molecular tools for precise detection, quantification, and genetic characterization. Techniques such as quantitative PCR (qPCR), digital PCR (dPCR), and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) each provide unique advantages for parasitology research. This guide objectively compares the performance of these technologies, with a specific focus on their application in the genotyping of parasites into Discrete Typing Units (DTUs)—a critical framework for understanding epidemiology and disease manifestations. Supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, this resource is designed to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in their methodological selections.

Technology Performance Comparison

Quantitative Performance of Detection and Genotyping Platforms

The selection of an appropriate molecular platform depends on the specific requirements of detection sensitivity, quantification accuracy, throughput, and genotyping resolution. The following tables summarize the key performance metrics of qPCR, dPCR, and NGS platforms based on recent comparative studies.

Table 1: Performance comparison of qPCR, dPCR, and NGS for detection and quantification applications.

| Technology | Primary Application | Sensitivity/LOD | Quantification Type | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qPCR | Target detection & quantification | Varies with assay design | Relative (requires standard curve) | High throughput, well-established, cost-effective | Relative quantification, susceptible to PCR inhibitors [31] |

| Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) | Absolute quantification of low-abundance targets | ~0.17 copies/µL input [31] | Absolute (no standard curve) | High precision, resistant to PCR inhibitors, absolute quantification [31] [32] | Lower dynamic range, higher cost per sample than qPCR |

| Nanoplate Digital PCR (ndPCR) | Absolute quantification | ~0.39 copies/µL input [31] | Absolute (no standard curve) | High precision, streamlined workflow [31] | Lower dynamic range than qPCR |

| NGS (Illumina) | High-throughput sequencing, variant discovery | Dependent on sequencing depth | Digital read counts | High multiplexing capability, discovers novel variants [32] | Higher cost for low-plexity, complex data analysis [32] |

Table 2: Performance of sequencing platforms in genotyping and structural variant detection. [33]

| Sequencing Platform | Read Type | Mapping Rate | Performance in Repeat-Rich Regions | Indel Capture Robustness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina HiSeq/NovaSeq | Short-Read | Most consistent, high genome coverage [33] | Lower than long-read platforms [33] | Most robust for known indel events (NovaSeq 2x250-bp) [33] |

| PacBio CCS | Long-Read | Highest reference-based mapping rate [33] | Best performance [33] | High |

| Oxford Nanopore | Long-Read | High | Best performance [33] | High |

| BGISEQ-500/MGISEQ-2000 | Short-Read | High | Lower than long-read platforms [33] | Lower than Illumina [33] |

Direct Comparative Data in Clinical and Research Settings

Head-to-head comparisons in real-world scenarios provide the most actionable data for researchers.

ctDNA Detection in Rectal Cancer: A 2025 study comparing ddPCR and NGS for detecting circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) found that ddPCR demonstrated a significantly higher detection rate. In a development cohort, ddPCR detected ctDNA in 58.5% (24/41) of baseline plasma samples, compared to only 36.6% (15/41) detected by an NGS panel (p=0.00075). The authors noted that ddPCR allows for operational costs that are 5–8.5-fold lower than NGS, despite requiring custom probes [32].

NGS Library Quantification: A comparison of DNA quantification methods for NGS library preparation found that ddPCR-based methods (ddPCR and ddPCR-Tail) provided absolute quantification without the need for a standard curve or additional equipment for fragment size analysis, simplifying the workflow compared to qPCR and fluorometry [34].

Digital PCR Platform Precision: A 2025 study comparing the QX200 ddPCR system (Bio-Rad) and the QIAcuity One ndPCR system (QIAGEN) found both platforms had similar limits of detection and quantification. However, precision was significantly impacted by the choice of restriction enzyme during sample preparation, especially for the ddPCR system. Using HaeIII instead of EcoRI improved ddPCR precision, with the coefficient of variation (CV) dropping to below 5% for all tested cell numbers [31].

Experimental Protocols for Integrated Genotyping

The following detailed protocol from a recent study on Trypanosoma cruzi transmission dynamics exemplifies the integration of qPCR for detection and quantification with NGS for genotyping and blood meal analysis [19].

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

- Sample Collection: Collect triatomine vectors from the field using manual searches and black light van traps. Conduct taxonomic identification of adults using morphological keys [19].

- DNA Extraction:

- Use the entire insect abdomen for DNA extraction to maximize parasite DNA yield.

- Mechanically disrupt tissue in ZR BashingBead Lysis Tubes.

- Incubate lysates overnight with Proteinase K and lysis buffer.

- Perform automated nucleic acid purification (e.g., chemagic 360 instrument) to obtain high-quality DNA for downstream applications [19].

Molecular Detection and Quantification by qPCR

- Reaction Setup: Use a validated qPCR assay targeting the T. cruzi satellite DNA region [19].

- Quantification Standard: Include a standard curve from a known T. cruzi strain (e.g., TcI strain MHOM/CO/04/MG) in each run to ensure accurate quantification [19].

- Internal Control: Co-amplify the triatomine 12S rRNA gene to confirm DNA quality and the absence of PCR inhibitors [19].

- Data Analysis: Quantify the parasitic load in equivalents/mL based on the standard curve. A 2025 study reported median parasitic loads as high as log10 8.09 equivalents/mL in insect vectors [19].

Genotyping by Next-Generation Sequencing

- Primary Amplification: Perform conventional PCR on qPCR-positive samples to amplify genotyping targets, such as the spliced leader intergenic region (SL-IR) of the mini-exon gene, which is highly conserved among strains yet variable enough for DTU discrimination [19] [35].

- Library Preparation:

- Confirm PCR amplicon size and quality on an agarose gel.

- For Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) sequencing, use the Ligation Sequencing Amplicons—Native Barcoding Kit (SQK-NBD114.96).

- Prepare sequencing libraries independently for each marker (e.g., SL-IR for genotyping and 12S rRNA for blood meal analysis) to avoid inter-marker competition.

- Load the prepared library onto a flow cell for sequencing [19].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Process the raw sequence data to assign DTUs (TcI-TcVI and TcBat) [35]. In the Texas study, this method revealed that all samples were infected with TcI, with some co-infected with TcIV [19].

Blood Meal Analysis via NGS

- Target Amplification: Amplify a ~215 bp fragment of the 12S rRNA gene from the insect DNA extract, which allows for the identification of mammalian host species [19].

- Sequencing and Analysis: Co-sequence the 12S rRNA amplicons alongside the genotyping targets. Bioinformatic analysis then identifies the blood meal sources by matching sequences to a database of vertebrate 12S rRNA sequences. This can reveal feeding patterns on dogs, humans, and wildlife [19].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated process from sample collection to data analysis:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of the described protocols requires specific, high-quality reagents. The following table details essential solutions and their functions.

Table 3: Key research reagents for molecular detection and genotyping of parasites.

| Research Reagent | Specific Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Streck Cell Free DNA BCT Tubes | Preserves blood samples for plasma separation and stabilizes cell-free DNA for ctDNA analysis [32] | ddPCR/NGS for liquid biopsy [32] |

| Proteinase K & Buffer ATL | Enzymatic and chemical lysis of tissues for comprehensive DNA release [19] | DNA extraction from insect/animal tissues [19] |

| Chemagic DNA Blood 400 Kit H96 | Automated, high-quality DNA purification on magnetic bead-based systems [19] | High-throughput nucleic acid extraction [19] |

| Ion AmpliSeq Cancer Hotspot Panel v2 | Amplifies and sequences hotspot regions in 50 genes for tumor mutation profiling [32] | Tumor-informed ctDNA assay design [32] |

| Ligation Sequencing Amplicons Kit (SQK-NBD114.96) | Prepares barcoded sequencing libraries from PCR amplicons for Oxford Nanopore [19] | Genotyping (mini-exon) and blood meal analysis (12S rRNA) [19] |

| Universal Probe Library (UPL) | Set of short, modified hydrolysis probes that can be used for a wide range of targets with tailored primers [34] | Flexible qPCR/ddPCR assay design [34] |

| Restriction Enzymes (HaeIII, EcoRI) | Digests DNA to break up tandem repeats or complex structures, improving PCR access and precision [31] | Gene copy number analysis in dPCR [31] |

qPCR, dPCR, and NGS are not mutually exclusive technologies but rather form a complementary toolkit for modern parasitology research. The choice between them should be driven by the specific research question: qPCR is ideal for high-throughput, cost-effective screening; dPCR provides superior precision and absolute quantification for low-abundance targets or difficult matrices; and NGS is unparalleled for discovering genetic diversity, genotyping complex populations, and conducting multi-target analyses like simultaneous pathogen and host identification. As the Texas T. cruzi study demonstrates, integrating these methods—using qPCR for initial screening and quantification, followed by NGS for detailed genotyping and blood meal analysis—provides the most comprehensive picture of parasite transmission dynamics, which is fundamental for developing targeted control strategies.

The comparative analysis of transmission dynamics across different parasite genera requires diagnostic tools that are both precise and adaptable. Information theory, particularly the concept of mutual information, provides a powerful framework for optimizing these diagnostic systems by quantifying the information shared between test results and true disease status. In parasitology, where host heterogeneity significantly influences transmission dynamics [36] [1] [6], mutual information moves beyond traditional metrics by capturing nonlinear relationships and complex dependencies in data. This approach is particularly valuable for understanding and differentiating the transmission strategies of diverse parasite genera, from the acute, flea-borne Bartonella to the chronic, contact-transmitted Mycoplasma [6].

The deployment of mutual information in diagnostic optimization addresses a critical challenge in parasitology: the need for tests that remain robust across varying host species, parasite strains, and environmental conditions. By systematically evaluating how much information test variables carry about infection status, researchers can develop threshold strategies that account for the intricate interplay between host traits and parasite characteristics that govern transmission success [6].

Theoretical Foundation: Mutual Information as a Diagnostic Metric

Core Concepts of Information Theory in Diagnostics

Mutual information (MI) originates from information theory and measures the mutual dependence between two random variables. Unlike correlation coefficients that primarily detect linear relationships, MI captures both linear and nonlinear associations, making it particularly suited for biological systems where relationships are often complex and non-linear.

In diagnostic applications, MI quantifies how much information a test result provides about the true disease state. Formally, the mutual information between a diagnostic test result (X) and disease status (Y) is defined as:

\(I(X;Y) = ∑{x∈X} ∑{y∈Y} p(x,y) \log \frac{p(x,y)}{p(x)p(y)}\\)

Where \(p(x,y)\) is the joint probability distribution of X and Y, and \(p(x)\) and \(p(y)\) are the marginal probability distributions. Higher MI values indicate that the test result provides more information about the disease status, enabling better diagnostic classification.

Comparative Advantages Over Traditional Metrics

Table 1: Comparison of Diagnostic Evaluation Metrics

| Metric | Measures | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutual Information | Reduction in uncertainty about disease given test result | Captures nonlinear relationships; No assumption of linearity | Computationally intensive; Requires larger sample sizes |

| Sensitivity/Specificity | Classification accuracy at a threshold | Intuitive clinical interpretation; Widely understood | Depends on threshold choice; Does not capture information content |

| Likelihood Ratios | How much a test result changes odds of disease | Combines sensitivity/specificity; Useful for sequential testing | Still depends on single threshold; Limited to binary classification |

| Area Under ROC Curve | Overall performance across thresholds | Comprehensive performance assessment; Threshold-independent | Does not measure information content; Can mask poor performance at specific thresholds |

When applied to parasite diagnostics, MI offers distinct advantages. Traditional metrics like sensitivity and specificity evaluate classification accuracy at specific thresholds but fail to capture the full information content that test variables carry about infection status. For parasites with complex transmission dynamics, such as Trypanosoma cruzi with its multiple discrete typing units [19] or Bartonella and Mycoplasma with their distinct host-specific dynamics [6], MI provides a more nuanced evaluation of diagnostic test performance across diverse contexts.

Computational Implementation of Mutual Information Analysis

Algorithmic Approaches for Feature Selection

The MAVS (Mutual Information with Attention-based Variable Selection) framework demonstrates a modern implementation of MI for diagnostic optimization [37]. This method combines mutual information with self-attention mechanisms to filter out irrelevant variables and reduce redundancy in high-dimensional data. The algorithm operates through a structured pipeline:

Part I: Relevance Filtering - Calculate MI between each measured variable and the quality variable (e.g., infection status). Remove variables with MI below a predefined threshold \(MI^\), where \(MI^ = \frac{1}{d0} ∑{j=1}^{d0} I(Xj;y)\), with \(d_0\) representing the dimension of measured variables.

Part II: Redundancy Reduction - Employ self-attention mechanisms to identify and remove redundant variables that provide overlapping information about the target condition.

Part III: Contribution Analysis - Compute Shapley values using kernelSHAP to quantify the contribution of each selected variable to the diagnostic prediction [37].

This approach has demonstrated superior performance in industrial applications, with validation on biomedical processes such as penicillin and erythromycin production showing enhanced accuracy and robustness compared to traditional methods [37].

Workflow for Diagnostic Test Optimization

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for applying mutual information in diagnostic test optimization:

Comparative Analysis of Diagnostic Optimization Methods

Performance Evaluation Across Methodologies

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of Diagnostic Optimization Methods

| Method | Application Context | Key Performance Metrics | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutual Information (MAVS) | Industrial processes (Penicillin, Erythromycin) [37] | RMSE: 0.89-1.24; R²: 0.87-0.93 [37] | Handles nonlinearity; Robust to noise | Computationally intensive for large datasets |

| Genetic Algorithm Thresholds (GAT) | Acute infection and sepsis test [38] | LR1: 0.089; LR5: 8.688; Extreme band coverage: 69.8% [38] | Optimizes multiple thresholds simultaneously; Customizable fitness function | Requires clearly defined clinical targets |

| Traditional ROC Analysis | Sequential test analysis [39] | Sensitivity: 85-92%; Specificity: 76-88% [39] | Simple implementation; Clinically familiar | Single threshold limitation; Poor handling of multiple classes |

| Probability Modifying Plot | Urinary tract infection [40] | Not quantitatively reported | Visualizes test sequence efficiency | Limited to sequential test analysis |

| Conditional Dependence Modeling | Sequential testing for colorectal cancer [39] | Sensitivity: 91.2%; Specificity: 87.5% [39] | Accounts for test interdependencies | Complex implementation; Requires specialized software |

Application in Parasite Transmission Studies

In parasite research, mutual information approaches enable nuanced analysis of transmission dynamics by identifying which host or parasite characteristics carry the most information about transmission outcomes. For example, in studying Trypanosoma cruzi transmission, MI could quantify how much information various vector characteristics (e.g., parasitic load, genotype) provide about transmission potential [19]. Similarly, in comparing Bartonella and Mycoplasma dynamics across rodent species, MI can identify which host traits are most informative for predicting infection duration and intensity [6].