Commercial vs. In-House PCR for Protozoa Detection: A 2025 Guide for Diagnostics and Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and diagnostics professionals evaluating commercial and in-house PCR assays for protozoan detection.

Commercial vs. In-House PCR for Protozoa Detection: A 2025 Guide for Diagnostics and Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and diagnostics professionals evaluating commercial and in-house PCR assays for protozoan detection. Covering foundational principles, methodological applications, and troubleshooting, it synthesizes recent multicentre study data to compare performance, cost, and standardization. The analysis highlights critical factors for assay selection, including sensitivity for Giardia duodenalis and Cryptosporidium spp., challenges in DNA extraction, and the impact of sample preservation. Future directions in digital PCR and standardized protocols are discussed to guide implementation in clinical and research settings targeting intestinal protozoa and other parasitic infections.

The Protozoa Diagnostic Landscape: Why PCR is Replacing Traditional Methods

The Global Burden of Pathogenic Intestinal Protozoa

Pathogenic intestinal protozoa represent a significant and persistent global health challenge, particularly in resource-limited settings. These parasites, including Giardia duodenalis, Entamoeba histolytica, and Cryptosporidium spp., are among the leading etiological agents of diarrheal diseases worldwide [1]. Recent systematic reviews estimate that intestinal protozoan parasites affect approximately 3.5 billion people globally, causing approximately 1.7 billion episodes of diarrheal disorders annually [1] [2]. Among these pathogens, Cryptosporidium alone causes an estimated 200,000 deaths annually, with the highest burden in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia [3]. The global prevalence of protozoan pathogens in diarrheal cases is estimated at 7.5%, with the highest rates observed in the Americas and Africa [3].

The diagnosis of these infections poses formidable challenges for clinicians and researchers alike. Microscopic examination of stool samples remains the reference method in many clinical laboratories, particularly in endemic areas with high parasitic prevalence but limited resources [1]. However, this method suffers from significant limitations in sensitivity and specificity and requires highly qualified personnel [1] [4]. Molecular diagnostic technologies, particularly real-time PCR (RT-PCR), are increasingly gaining traction in non-endemic areas characterized by low parasitic prevalence due to their enhanced sensitivity and specificity [1] [4]. This review comprehensively compares commercial and in-house PCR methodologies for protozoa detection, providing researchers with experimental data and protocols to inform their diagnostic strategies.

Comparative Performance of Molecular Diagnostic Platforms

The evolution of diagnostic techniques for intestinal protozoa has progressed from traditional microscopy to advanced molecular methods. Microscopy, while cost-effective and widely available, has limited sensitivity and specificity and cannot differentiate between morphologically identical species, such as pathogenic E. histolytica and non-pathogenic E. dispar [1]. Immunodiagnostic methods like enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and immunochromatography offer rapid screening capabilities but may yield elevated rates of false positives and negatives [1]. Molecular approaches, particularly RT-PCR, provide superior sensitivity and specificity, with the additional advantage of differentiating between species based on genetic markers [1] [4].

Recent multicenter studies have directly compared the performance of commercial and in-house PCR assays against traditional microscopy and each other. These comparisons are essential for laboratories seeking to implement molecular diagnostics, as they provide critical data on test reliability, cost-effectiveness, and technical requirements [1] [4] [5].

Performance Metrics for Major Pathogenic Protozoa

A 2025 multicenter study involving 18 Italian laboratories provided comprehensive performance data for both commercial and in-house RT-PCR assays compared to conventional microscopy [1] [6] [4]. The study analyzed 355 stool samples (230 freshly collected and 125 preserved in media) for infections with Giardia duodenalis, Cryptosporidium spp., Entamoeba histolytica, and Dientamoeba fragilis [4].

Table 1: Performance comparison of molecular detection methods for intestinal protozoa

| Parasite | Method | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Sample Type Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G. duodenalis | AusDiagnostics Kit | 91.0 | 98.9 | Performs well on both fresh and preserved samples |

| In-house RT-PCR | 93.3 | 97.0 | Consistent performance across sample types | |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | AusDiagnostics Kit | 78.9 | 99.1 | Sensitivity limitations due to DNA extraction issues |

| In-house RT-PCR | 78.9 | 100 | Same sensitivity limitations as commercial kit | |

| D. fragilis | AusDiagnostics Kit | 68.4 | 91.9 | Inconsistent detection across platforms |

| In-house RT-PCR | 68.4 | 88.9 | Similar consistency issues as commercial kit | |

| E. histolytica | Molecular Methods | Critical for accurate diagnosis | High specificity reported | Microscopy cannot differentiate from non-pathogenic species |

The data reveal several important patterns. First, both commercial and in-house methods demonstrated excellent performance for Giardia duodenalis detection, with high sensitivity and specificity [6]. Second, preserved stool samples generally yielded better PCR results than fresh samples, likely due to better DNA preservation [4]. Third, both platforms showed limited sensitivity for Cryptosporidium spp. and D. fragilis, attributed to inadequate DNA extraction from these particular parasites [4]. Finally, molecular assays proved critical for accurate diagnosis of E. histolytica, which cannot be differentiated from non-pathogenic species using conventional microscopy [1].

A separate 2020 study compared one in-house and three commercial qPCR kits for 15 parasites and microsporidia, analyzing 500 DNA samples from patients with high likelihood of parasitic infections [5]. The results showed varying inter-assay agreement across different parasites, ranging from "almost perfect" (κ = 0.81-1.00) for Dientamoeba fragilis and Cryptosporidium spp. to "substantial" (κ = 0.61-0.80) for Giardia duodenalis and "slight" (κ = 0-0.20) for Cyclospora spp. and Strongyloides stercoralis [5]. This variability highlights the importance of platform selection based on the target parasites of interest.

Impact of Technical Factors on Detection Performance

The efficacy of molecular methods depends critically on the specific protocols employed at each stage of the diagnostic process. A comprehensive study evaluating 30 distinct protocol combinations for Cryptosporidium parvum detection demonstrated that different combinations of pre-treatment, extraction, and amplification methods yielded significantly varying results [7]. The optimal approach for detecting C. parvum DNA combined mechanical pre-treatment, the Nuclisens Easymag extraction method, and the FTD Stool Parasite DNA amplification method, which achieved 100% detection efficiency [7].

Table 2: Key technical factors influencing molecular detection performance

| Process Stage | Considerations | Impact on Results |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection & Storage | Fresh vs. preserved samples; preservation media | Preserved samples generally yield better DNA quality and more consistent PCR results [4] |

| DNA Extraction | Manual vs. automated methods; kit selection | Critical step affecting sensitivity; inadequate extraction particularly impacts Cryptosporidium and D. fragilis detection [7] [4] |

| Amplification Target | Single-copy vs. multi-copy genes; nuclear vs. mitochondrial DNA | Multi-copy targets (e.g., kinetoplast DNA) increase sensitivity; combining targets minimizes false negatives [8] |

| Inhibition Control | Internal extraction controls; inhibition monitoring | Essential for distinguishing true negatives from false negatives due to PCR inhibitors in stool samples [1] |

The complex wall structure of protozoan parasites presents particular challenges for DNA extraction. The robust oocyst walls of Cryptosporidium species require specialized disruption methods to release amplifiable DNA [1] [7]. This technical hurdle likely contributes to the lower sensitivity observed for Cryptosporidium detection across both commercial and in-house platforms [4].

Experimental Protocols for Molecular Detection

Standardized Workflow for Molecular Detection

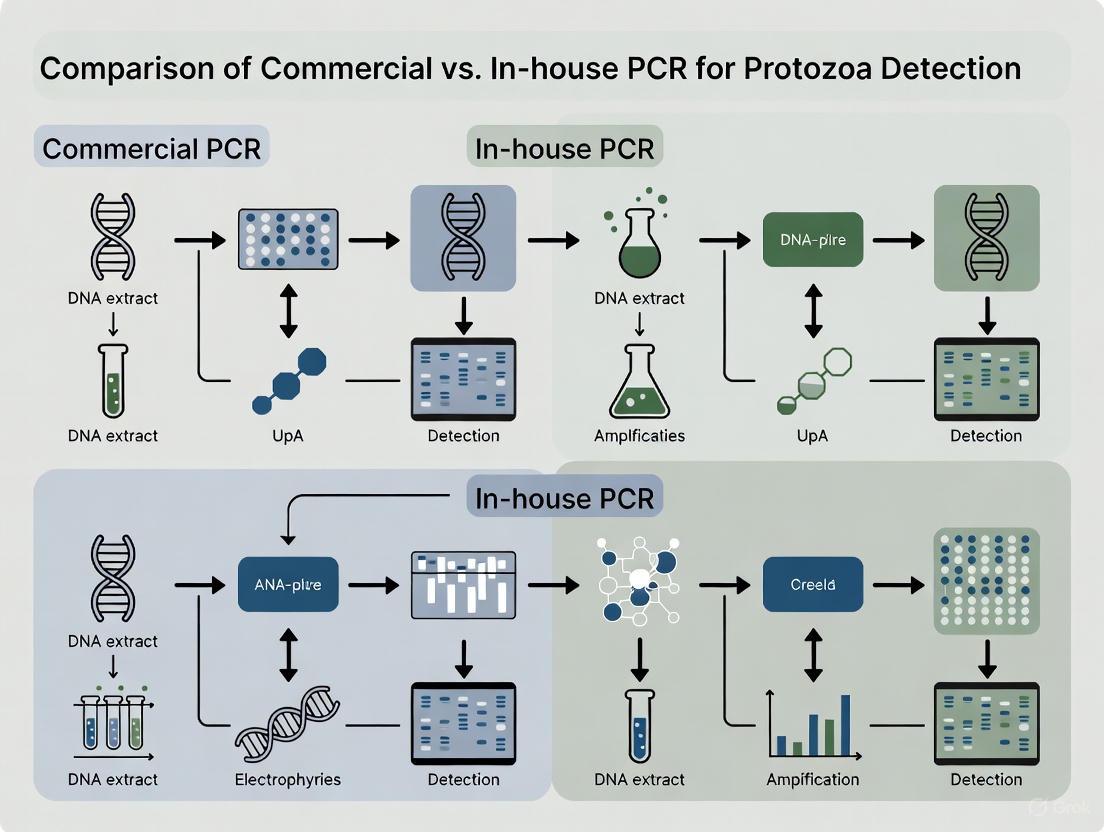

The molecular detection of intestinal protozoa follows a standardized workflow encompassing sample preparation, nucleic acid extraction, and amplification/detection. The following diagram illustrates the critical decision points in this process:

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction

The sample preparation and DNA extraction phase is arguably the most critical determinant of success in protozoan detection. In the multicenter Italian study, approximately 1μl of each fecal sample was mixed with 350μl of S.T.A.R (Stool Transport and Recovery Buffer; Roche Applied Sciences, Basel, Switzerland) using a sterile loop and incubated for 5 minutes at room temperature [1]. After centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 2 minutes, 250μl of supernatant was carefully collected and combined with 50μl of internal extraction control [1]. DNA extraction was then performed using the MagNA Pure 96 DNA and Viral NA Small Volume Kit on the MagNA Pure 96 System (Roche Applied Sciences), representing a fully automated nucleic acid preparation based on magnetic separation of nucleic acid-bead complexes [1].

For the in-house PCR protocol, each reaction mixture included 5μl of MagNA extraction suspension, 12.5μl of 2× TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 2.5μl of primers and probe mix, and sterile water to a final volume of 25μl [1]. A multiplex tandem PCR assay was then performed using appropriate cycling conditions [1].

Emerging Detection Technologies

Beyond conventional PCR, emerging technologies show promise for protozoan detection. Microfluidic Impedance Cytometry (MIC) has been used to characterize the AC electrical (impedance) properties of single parasites, demonstrating rapid discrimination based on viability and species [9]. This technology achieved over 90% certainty in identifying live and inactive C. parvum oocysts and over 92% certainty in discriminating between Cryptosporidium parvum, Cryptosporidium muris, and Giardia lamblia [9]. MIC offers a label-free approach that requires minimal sample processing and can measure up to 1000 particles per second, significantly reducing identification time and labor demands compared to existing methods [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful detection and analysis of pathogenic intestinal protozoa requires carefully selected reagents and platforms. The following table details key research solutions and their applications in protozoan research:

Table 3: Essential research reagents and platforms for protozoan detection

| Reagent/Platform | Manufacturer/Distributor | Application & Function |

|---|---|---|

| MagNA Pure 96 System | Roche Applied Sciences | Automated nucleic acid extraction using magnetic bead technology [1] |

| S.T.A.R Buffer | Roche Applied Sciences | Stool Transport and Recovery Buffer for sample stabilization [1] |

| TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Ready-to-use reaction mix for fast real-time PCR amplification [1] |

| AusDiagnostics PCR Kit | AusDiagnostics Company (R-Biopharm Group) | Commercial multiplex PCR test for intestinal protozoa detection [1] [4] |

| Para-Pak Preservation Media | Meridian Bioscience | Stool preservative for maintaining parasite DNA integrity during transport and storage [4] |

| FTD Stool Parasite DNA Amplification | Fast-Track Diagnostics | PCR-based detection method showing high efficiency for C. parvum [7] |

| Nuclisens Easymag | bioMérieux | Nucleic acid extraction system optimal for Cryptosporidium detection [7] |

The global burden of pathogenic intestinal protozoa remains significant, with billions of people affected worldwide. Molecular diagnostic methods, particularly RT-PCR, have revolutionized detection capabilities for these pathogens, offering superior sensitivity and specificity compared to traditional microscopy. Both commercial and in-house PCR platforms demonstrate excellent performance for detecting Giardia duodenalis, with sensitivity exceeding 90% for both platforms [6]. However, detection challenges persist for Cryptosporidium spp. and D. fragilis, primarily due to difficulties in DNA extraction from these organisms [4].

The choice between commercial and in-house molecular methods involves careful consideration of several factors. Commercial kits offer standardization and convenience, while in-house methods provide flexibility and potential cost savings for high-volume laboratories. Regardless of the platform selected, sample processing methods—particularly DNA extraction—critically impact detection sensitivity and must be optimized for the target pathogens [7]. Future directions in protozoan diagnostics include the refinement of automated platforms, the development of point-of-care molecular tests, and the implementation of new technologies like microfluidic impedance cytometry for rapid analysis [9]. As these technologies evolve, they promise to enhance our understanding of the global epidemiology of intestinal protozoa and improve control strategies for these significant pathogens.

For over a century, conventional light microscopy has served as the cornerstone of pathological diagnosis and parasitological identification. Despite its longstanding role as a reference method in many clinical laboratories, this technique faces significant challenges in modern diagnostic and research contexts, particularly when compared with emerging molecular technologies. Within the framework of comparing commercial versus in-house PCR for protozoa research, understanding these limitations becomes paramount for researchers aiming to optimize diagnostic accuracy, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness. This guide provides a comprehensive, evidence-based comparison between conventional microscopy and molecular methods, focusing on their performance characteristics and practical applications in protozoa research.

Analytical Limitations: Sensitivity and Specificity

The diagnostic performance of conventional microscopy is fundamentally constrained by limitations in sensitivity and specificity, which become particularly evident when compared to molecular techniques like PCR.

Table 1: Comparative Diagnostic Performance of Microscopy vs. PCR

| Parasite/Context | Microscopy Sensitivity | PCR Sensitivity | Microscopy Specificity | PCR Specificity | Study Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil-transmitted helminths (overall) | 22.4% | Reference | 94.3% | Reference | [10] |

| Ascaris lumbricoides | 33.3% | Reference | 97.3% | Reference | [10] |

| Necator americanus | 17.5% | Reference | 99.2% | Reference | [10] |

| Intestinal protozoa (multiplex PCR) | 28.75%* | 27.9%* | Limited differentiation | 100% concordance with sequencing | [11] |

| Entamoeba histolytica | Cannot differentiate from non-pathogenic species | Species-specific identification | Limited | High | [12] [13] |

*Percentage positive in patient samples; microscopy and PCR showed moderate to almost perfect agreement depending on parasite species [11].

Microscopy's limited sensitivity is especially problematic in low-prevalence settings or cases with low parasite burden, where the technique may fail to detect infections altogether. A study on soil-transmitted helminths demonstrated concerningly low sensitivity of just 22.4% for microscopy compared to PCR [10]. This deficiency stems from several factors: the intermittent shedding of parasites in stools, non-uniform distribution of parasites in samples, and low infection intensities that fall below microscopy's detection threshold [10] [13].

Regarding specificity, conventional microscopy struggles significantly with species differentiation, particularly for morphologically similar organisms. Crucially, microscopy cannot differentiate pathogenic Entamoeba histolytica from non-pathogenic Entamoeba dispar and Entamoeba moshkovskii, a distinction critical for appropriate treatment decisions [12] [11] [13]. This limitation necessitates additional testing or leads to potential misdiagnosis and unnecessary treatments.

Expertise Dependency and Operational Challenges

The reliability of conventional microscopy is exceptionally dependent on operator expertise, introducing substantial variability in diagnostic outcomes across different settings and practitioners.

Table 2: Operational Challenges of Conventional Microscopy

| Challenge Category | Specific Limitations | Impact on Diagnostics/Research |

|---|---|---|

| Expertise Dependency | Requires skilled microscopists for accurate identification [12] [10] | High inter-observer variability; limited to specialized personnel |

| Workflow Efficiency | Time-consuming manual process [13]; requires examination of multiple samples [10] [11] | Increased turnaround time; resource intensive |

| Identification Limitations | Subjective interpretation [14]; inability to differentiate morphologically similar species [12] [13] | Misidentification risk; compromised specificity |

| Data Management | No permanent digital record [15]; difficult retrospective reviews | Limited quality assurance; challenging for research comparisons |

The expertise requirement presents a significant barrier in many settings, as accurately differentiating parasites from artifacts and distinguishing between similar species demands substantial training and experience [12] [10]. This subjectivity introduces inter-observer variability that compromises the consistency and reliability of microscopic diagnosis [14] [13].

Operationally, conventional microscopy remains labor-intensive and time-consuming. The standard protocol requiring examination of three stool samples collected on alternate days creates logistical challenges for both patients and laboratories [10] [13]. This multi-sample requirement increases workload, extends turnaround times, and adds to overall diagnostic costs despite the apparent low per-test cost of microscopy itself.

Comparative Workflow Analysis: Microscopy vs. Molecular Methods

Comparative Methodologies: Experimental Protocols

Understanding the experimental protocols for both conventional microscopy and PCR methods is essential for evaluating their comparative advantages and limitations in research settings.

Conventional Microscopy Protocol

The standard microscopic examination typically follows this protocol:

- Sample Collection: Multiple stool samples (typically three) collected on alternate days to account for intermittent parasite shedding [13].

- Specimen Preparation: Fresh stool samples are stained with Giemsa, while fixed samples are processed using formalin-ethyl acetate (FEA) concentration techniques [12].

- Microscopic Examination: Prepared slides are examined under light microscopy at various magnifications (typically 10x, 40x) [15].

- Identification: Based on morphological characteristics of trophozoites, cysts, oocysts, or helminth eggs [12] [13].

This process remains labor-intensive, requiring approximately 15-30 minutes of expert technician time per sample, with sensitivity highly dependent on parasite load and examiner expertise [12] [10].

PCR-Based Detection Protocol

Molecular methods offer a standardized alternative with the following general protocol:

- DNA Extraction:

- PCR Amplification:

- Detection: Real-time PCR systems (e.g., ABI 7900HT, CFX 96) monitor amplification fluorescence [12] [13].

Multiplex PCR formats enable simultaneous detection of multiple pathogens (e.g., Giardia duodenalis, Cryptosporidium spp., Entamoeba histolytica) in a single reaction, significantly improving workflow efficiency [11].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Implementing either conventional or molecular diagnostic approaches requires specific reagents and equipment with distinct functional considerations.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Equipment | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Formalin-Ethyl Acetate (FEA) | Stool sample preservation and concentration | Conventional microscopy [12] |

| Giemsa Stain | Visual enhancement of parasitic structures | Microscopic identification [12] |

| S.T.A.R. Buffer | Stool transport, recovery, and DNA stabilization | Molecular diagnostics/DNA extraction [12] |

| Polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (PvPP) | PCR inhibitor removal | DNA purification for PCR [13] |

| DNA Isolation Kits | Nucleic acid extraction and purification | PCR-based detection [12] [13] |

| TaqMan Master Mix | PCR reaction components | Real-time PCR amplification [12] |

| Specific Primers/Probes | Target DNA sequence recognition | Pathogen-specific detection [12] [13] |

| Internal Extraction Controls | Process efficiency monitoring | Quality control in molecular assays [12] [13] |

Transition to Digital and Molecular Solutions

The limitations of conventional microscopy have accelerated the adoption of digital pathology and molecular methods, which address many of these constraints while introducing new capabilities.

Digital pathology systems convert physical glass slides into high-resolution whole slide images (WSIs) that can be viewed, shared, and analyzed electronically [14] [15]. This digital transformation enables:

- Remote consultations and collaborations across geographical boundaries [15]

- Integration with AI-based tools for automated image analysis, reducing subjectivity [14]

- Improved workflow efficiency with reported turnaround time reductions of 3.72 days in one implementation study [16]

- Permanent digital archives for retrospective reviews and quality assurance [15]

Molecular methods, particularly PCR-based approaches, offer paradigm-shifting advantages for protozoa research:

- Single-sample requirement compared to multiple samples for microscopy [13]

- Superior sensitivity and specificity, especially in low-prevalence settings [10]

- Species-specific differentiation of morphologically identical organisms [12] [13]

- Standardization potential across laboratories and settings [12] [11]

The transition to these advanced methodologies represents a fundamental shift from subjective, expertise-dependent morphological assessment toward objective, standardized molecular detection that offers greater consistency, accuracy, and efficiency for research applications.

Conventional microscopy faces substantial limitations in sensitivity, specificity, and expertise dependency that constrain its effectiveness in modern protozoa research and diagnostics. While it remains a valuable tool for initial screening and in resource-limited settings, the evidence clearly demonstrates the superiority of molecular methods for accurate pathogen detection, species differentiation, and research standardization. The integration of digital pathology platforms and PCR-based detection represents the future of parasitological diagnosis, offering researchers enhanced capabilities for precise, efficient, and reproducible protozoa identification. As the field continues to evolve, the complementary use of these technologies—leveraging their respective strengths—will likely provide the most comprehensive approach for advancing protozoa research and improving diagnostic outcomes.

The diagnosis of parasitic infections has undergone a remarkable transformation, shifting from traditional reliance on microscopy and serological assays toward sophisticated molecular technologies. This evolution reflects an ongoing pursuit of greater diagnostic accuracy, specificity, and efficiency in both clinical and research settings. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) long served as a cornerstone serological technique, providing a pragmatic bridge from microscopic methods to more standardized testing. However, the emergence of real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) technologies has redefined diagnostic possibilities, offering unprecedented sensitivity and specificity for pathogen detection. Within molecular diagnostics itself, a significant debate continues regarding the relative merits of commercial PCR kits versus in-house laboratory-developed tests, each presenting distinct advantages in standardization, customization, cost, and performance. This guide objectively compares these diagnostic approaches, providing researchers and scientists with experimental data and protocols to inform their methodological selections for protozoan pathogen detection.

Methodological Comparison: ELISA vs. Real-Time PCR

Fundamental Principles and Workflows

ELISA operates on the principle of antigen-antibody recognition. In the context of parasitic diagnosis, plates are typically coated with parasite-specific antigens which bind to antibodies present in patient samples. This binding is then detected through enzyme-linked secondary antibodies that produce a measurable colorimetric signal [17]. The technique indirectly indicates infection by detecting the host's immune response, which can persist after successful treatment, potentially leading to false positives in treated individuals [17] [18].

In contrast, real-time PCR directly detects the genetic material of the parasite itself. This process involves the extraction of nucleic acids from clinical samples, followed by amplification of parasite-specific DNA sequences using target-specific primers and probes. The reaction enables both detection and quantification by monitoring fluorescence at each amplification cycle [17] [19]. This direct pathogen detection allows for differentiation between active and past infections, a significant advantage over serological methods.

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Recent studies provide robust quantitative comparisons between these methodologies. A 2024 study on human fascioliasis demonstrated that both ELISA and real-time PCR identified 44 out of 70 samples (62.86%) as positive for Fasciola hepatica, showing a high agreement of 94.4% (Cohen’s kappa ≥ 0.7) [17]. The study noted no cross-reactivity with other parasitic diseases in either test, confirming high specificity.

However, broader analyses reveal more nuanced performance differences. Research on intestinal protozoa found that molecular methods significantly outperform traditional techniques in sensitivity. One study reported that real-time PCR was positive in 72 of 98 samples (73.5%), whereas microscopic examination was positive in only 37 (37.7%) samples [19]. This enhanced sensitivity is particularly crucial for asymptomatic cases, where real-time PCR detected parasites in 57.4% (31/54) of samples compared to just 18.5% (10/54) by microscopy [19].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Diagnostic Methods for Various Parasites

| Parasite | Diagnostic Method | Sensitivity | Specificity | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasciola hepatica | ELISA vs. Real-Time PCR | 62.86% (both) | High (no cross-reactivity) | 94.4% agreement between tests | [17] |

| Gastrointestinal Parasites (Multiple) | Real-Time PCR vs. Microscopy | 73.5% vs. 37.7% | Not specified | Significant superiority in asymptomatic cases (57.4% vs. 18.5%) | [19] |

| Giardia duodenalis | Commercial vs. In-house PCR | Complete agreement | Complete agreement | High sensitivity and specificity for both methods | [1] [4] |

| Entamoeba histolytica | Molecular Assays | Critical for diagnosis | Critical for diagnosis | Essential for differentiation from non-pathogenic species | [1] [20] |

| Chronic Chagas Disease | ELISA | 97.7% | 96.3% | Remains primary diagnostic method | [18] |

| Chronic Chagas Disease | PCR | 50-90% | ~100% | Not recommended for primary diagnosis in chronic phase | [18] |

The critical advantage of molecular methods for specific differentiations is exemplified in amebiasis diagnosis. Microscopy cannot distinguish pathogenic Entamoeba histolytica from non-pathogenic Entamoeba dispar, whereas real-time PCR provides definitive identification, directly impacting clinical management [1] [20].

Figure 1: Comparative Workflows of ELISA and Real-Time PCR. The diagram illustrates the fundamental procedural differences between the two methods, highlighting ELISA's indirect detection of immune response versus real-time PCR's direct detection of pathogen DNA.

Commercial vs. In-House Real-Time PCR Assays

Performance and Agreement Across Platforms

The choice between commercial and in-house PCR tests represents a significant consideration for diagnostic laboratories and research institutions. A comprehensive 2020 test comparison evaluated one in-house real-time PCR platform and three commercial kits for 15 parasites and microsporidia, analyzing 250-500 nucleic acid extracts from stool samples [5]. The study employed Latent Class Analysis (LCA) to estimate performance without a perfect gold standard, revealing variable inter-assay agreement across different parasite targets.

Table 2: Inter-Assay Agreement Between Commercial and In-House PCR Tests for Selected Parasites

| Parasite | Inter-Assay Agreement (Kappa Value) | Agreement Level | Positive Results per 250 Samples (Range Across Assays) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dientamoeba fragilis | 0.81 - 1 | Almost Perfect | 26 - 28 |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | 0.81 - 1 | Almost Perfect | 27 - 36 |

| Ascaris lumbricoides | 0.81 - 1 | Almost Perfect | 79 - 96 |

| Giardia duodenalis | 0.61 - 0.8 | Substantial | 184 - 205 |

| Blastocystis spp. | 0.61 - 0.8 | Substantial | 174 - 183 |

| Entamoeba histolytica | 0.41 - 0.6 | Moderate | 7 - 16 |

| Strongyloides stercoralis | 0 - 0.2 | Slight | 6 - 38 |

| Cyclospora spp. | 0 - 0.2 | Slight | 6 - 13 |

The data indicates that agreement was highest for Dientamoeba fragilis, Cryptosporidium spp., and Ascaris lumbricoides (almost perfect), and substantial for Giardia duodenalis and Blastocystis spp [5]. However, agreement was only moderate for Entamoeba histolytica and slight for Strongyloides stercoralis and Cyclospora spp., highlighting the diagnostic challenges posed by these parasites [5].

A 2025 multicentre study in Italy involving 18 laboratories further reinforced these findings, showing complete agreement between commercial (AusDiagnostics) and in-house PCR methods for detecting Giardia duodenalis [1] [4]. Both methods demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity comparable to microscopy. For Cryptosporidium spp. and D. fragilis, both platforms showed high specificity but variable sensitivity, potentially due to differences in DNA extraction efficiency from resistant oocysts and cysts [1].

Practical Considerations for Implementation

Beyond raw performance metrics, several practical factors influence the choice between commercial and in-house platforms:

- Standardization and Compliance: Commercial kits offer superior standardization, with the European Union Regulation (EU) 2017/746 increasingly requiring certified tests unless additional benefit of in-house testing can be demonstrated [5].

- Customization and Flexibility: In-house assays provide greater flexibility to adapt to specific research needs, local pathogen variants, or to include novel targets not available in commercial panels [5] [20].

- Cost Structure: Commercial kits involve higher per-test reagent costs but lower development and validation overhead. In-house tests require significant upfront investment in development and validation but may be more cost-effective for high-volume specialized testing [5].

- Sample Preparation: The efficiency of DNA extraction varies significantly between protocols and directly impacts sensitivity. The Italian multicentre study identified DNA extraction as a critical factor affecting sensitivity, particularly for parasites with robust wall structures like Cryptosporidium [1].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for ELISA-Based Detection

The following protocol for detecting anti-Fasciola antibodies using excretory-secretory antigens (ESAg) exemplifies a standardized serological approach [17]:

- Antigen Preparation: Coat ELISA microplates with 1 µg/mL of F. hepatica ESAgs in 0.05 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6), 100 µL/well. Incubate overnight at 37°C.

- Washing and Blocking: Wash plates five times with PBST (PBS with 0.05% Tween 20). Block excess binding sites with 3% skimmed milk in PBST and incubate for 2 hours at 37°C.

- Sample Incubation: Add 100 µL of diluted patient serum (1:500 in PBST) to wells. Incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes, then wash plates.

- Conjugate Incubation: Add 100 µL of diluted anti-human IgG horseradish-peroxidase conjugate (1:12,000 in PBST) to each well. Incubate for 30 minutes at 37°C, then wash.

- Detection: Add 100 µL/well of OPD substrate solution (o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride with 0.025% H₂O₂ in 0.1 M citrate buffer, pH 5.0). Incubate for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark.

- Signal Measurement: Stop the reaction with 50 µL of 1 M sulfuric acid. Measure the optical density at 492 nm using a microplate reader. The cut-off is typically set as the mean OD of negative controls plus two standard deviations.

Protocol for Real-Time PCR Detection

A representative protocol for real-time PCR detection of Fasciola hepatica targets the ribosomal ITS1 sequence [17]:

- DNA Extraction: Extract DNA from serum or stool samples using a commercial genomic DNA kit. Incorporate modifications as needed for specific sample types, such as mechanical disruption with glass beads for stool samples [19].

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a reaction mix containing:

- 5 µL of extracted DNA

- 12.5 µL of 2× TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix

- 2.5 µL of primer-probe mix (targeting ITS1 or other specific sequences)

- Nuclease-free water to a final volume of 25 µL

- Amplification Parameters: Run the real-time PCR using cycling conditions optimized for the specific instrument and primers. A typical program includes:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2-10 minutes

- 40-45 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 1 minute (with fluorescence acquisition)

- Inhibition Control: Include an internal control (exogenous synthetic oligonucleotide or amplification of a universal bacterial sequence) to detect potential PCR inhibition in each sample [19].

- Data Analysis: Determine positive results based on cycle threshold (Ct) values crossing a predetermined fluorescence threshold. Samples with Ct values >35 may show reduced reproducibility and require careful interpretation [20].

Figure 2: Decision Framework for Commercial vs. In-House PCR Platforms. This diagram outlines the key advantages and disadvantages of each approach to guide researchers in selecting the most appropriate platform for their specific needs.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of parasitic diagnostics requires careful selection of core reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Parasite Diagnosis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Excretory-Secretory Antigens (ESAg) | Coating antigen for ELISA; captures specific antibodies from patient samples. | Prepared from adult F. hepatica worms cultured in RPMI 1640 medium [17]. |

| Microplates | Solid phase for ELISA reactions. | ELISA microplates (e.g., Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) [17]. |

| Enzyme-Conjugated Antibodies | Detection antibodies that generate measurable signal in ELISA. | Anti-human IgG horseradish-peroxidase conjugate [17]. |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality nucleic acids from diverse clinical samples. | Commercial kits (e.g., QIamp DNA Stool Mini Kit, DNG-PLUS); mechanical disruption with glass beads improves yield [17] [19]. |

| PCR Master Mix | Provides optimal environment for DNA amplification; includes enzymes, dNTPs, buffer. | 2× TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix [1] [20]. |

| Specific Primers & Probes | Target parasite-specific DNA sequences for amplification and detection. | Hydrolysis probes (TaqMan) targeting ribosomal ITS1 (Fasciola), SSU rRNA (Entamoeba, Strongyloides), or other specific genes [17] [19] [20]. |

| Internal Controls | Monitor extraction efficiency and detect PCR inhibition. | Exogenous synthetic oligonucleotides or amplification of universal bacterial sequences [19]. |

The evolution from ELISA to real-time PCR represents a paradigm shift in parasitic disease diagnosis, moving from indirect serological assessment to direct, sensitive pathogen detection. While ELISA remains a valuable tool for seroprevalence studies and in resource-limited settings, real-time PCR offers demonstrably superior sensitivity and specificity, particularly for detecting low-level infections and differentiating morphologically similar species [17] [19].

The choice between commercial and in-house PCR platforms involves nuanced trade-offs. Commercial kits provide standardization and regulatory compliance advantages, while in-house assays offer customization and potential cost benefits for specialized applications [5] [1]. The observed variability in inter-assay agreement across different parasite targets underscores that no single platform is universally superior [5] [20]. Future developments will likely focus on standardizing DNA extraction protocols, expanding multiplexing capabilities, and reducing costs to make molecular diagnostics more accessible in endemic regions. The integration of these advanced molecular tools into public health strategies will be crucial for accurate surveillance, effective treatment, and ultimate control of parasitic protozoan diseases.

The diagnosis of parasitic protozoan infections is crucial for public health, particularly in regions with poor sanitation. For years, microscopy served as the conventional diagnostic standard, but it is hampered by requirements for high technical expertise, subjectivity, and low sensitivity [1]. Molecular methods, especially real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR), have emerged as powerful tools offering superior sensitivity, specificity, and throughput [21] [22]. This shift presents laboratories with a critical choice: to adopt commercially available, standardized qPCR kits or to develop and validate their own in-house assays. This guide objectively compares the performance of these two approaches, providing experimental data to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in their selection of diagnostic tools for protozoa research.

Performance Comparison: Commercial Kits vs. In-House Assays

Direct comparisons of commercial and in-house PCR assays across various parasites reveal a complex performance landscape, where the optimal choice can depend on the specific protozoan target and the context of use.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Commercial and In-House PCR Assays for Key Protozoa

| Parasite | Assay Type | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV/NPV (%) | Key Findings | Source (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Parasites & Microsporidia (15 targets) | Commercial & In-House qPCR | Varies by parasite & assay | Varies by parasite & assay | N/A | Agreement ranged from "almost perfect" to "poor" depending on the parasite. Overall, commercial and in-house assays showed comparable performance. | [5] (2020) |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | VIASURE Commercial Multiplex qPCR | 96 | 99 | 97 / 100 | The VIASURE assay demonstrated high diagnostic accuracy and identified multiple Cryptosporidium species. | [23] (2022) |

| Giardia duodenalis | VIASURE Commercial Multiplex qPCR | 94 | 100 | 99 / 98 | The assay showed high performance for detecting G. duodenalis and differentiated several genetic assemblages. | [23] (2022) |

| Entamoeba histolytica | VIASURE Commercial Multiplex qPCR | 96 | 100 | 100 / 99 | The kit provided rapid and accurate identification, crucial for distinguishing it from non-pathogenic species. | [23] (2022) |

| Giardia duodenalis | AusDiagnostics Commercial vs. In-House RT-PCR | Complete agreement between methods | Complete agreement between methods | N/A | Both methods demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity, performing similarly to microscopy. | [1] (2025) |

| Entamoeba histolytica | Seegene Allplex GI-Parasite (Commercial) | 33.3 (75 with frozen specimens) | 100 | 100 / 99.6 | Highlighted the challenge of variable sensitivity; confirmatory testing may be necessary for this pathogen. | [22] (2025) |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | Three In-House & Two Commercial qPCR | All detected 1 CFU/μl | Specific for M. pneumoniae | N/A | All five procedures demonstrated comparable sensitivity, but quantification of genome copies varied by a factor of 20. | [24] (2008) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols from Key Studies

Multicenter Evaluation of Commercial and In-House RT-PCR

A 2025 Italian multicentre study involving 18 laboratories compared a commercial RT-PCR test (AusDiagnostics) and an in-house RT-PCR assay against traditional microscopy for identifying infections with Giardia duodenalis, Cryptosporidium spp., Entamoeba histolytica, and Dientamoeba fragilis [1].

- Sample Collection and Preparation: The study analyzed 355 stool samples (230 fresh, 125 preserved). Fresh samples were stained with Giemsa, while fixed samples were processed using the formalin-ethyl acetate (FEA) concentration technique per WHO and CDC guidelines. After microscopic examination, all samples were frozen at -20°C.

- DNA Extraction: A standardized, automated protocol was used. A fecal sample was mixed with Stool Transport and Recovery Buffer (S.T.A.R. Buffer), centrifuged, and the supernatant was used for nucleic acid extraction on the MagNA Pure 96 System using the MagNA Pure 96 DNA and Viral NA Small Volume Kit.

- PCR Amplification: For the in-house assay, each 25 µL reaction contained 5 µL of extracted DNA, 2× TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix, a primers and probe mix, and sterile water. Multiplex tandem PCR was performed.

- Key Findings: The study concluded that molecular methods are promising for diagnosing intestinal protozoan infections. The commercial and in-house assays performed well for G. duodenalis and Cryptosporidium spp. in fixed specimens, but detection of D. fragilis was inconsistent, suggesting a need for standardized DNA extraction methods [1].

Clinical Evaluation of a Novel Commercial Multiplex qPCR

A 2022 study evaluated the VIASURE Cryptosporidium, Giardia, & E. histolytica real-time PCR assay using a large panel of well-characterized DNA samples [23].

- Sample Panel: The evaluation used 358 DNA samples obtained from clinical stool specimens or cultured isolates from a national reference center. The panel included positives for Cryptosporidium spp. (n=96), G. duodenalis (n=115), E. histolytica (n=25), and other parasitic species to test specificity.

- Analysis: The performance of the VIASURE assay was assessed by calculating estimated sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values against the characterized sample set. The assay's ability to identify different species and genetic variants was also evaluated.

- Key Findings: The VIASURE assay demonstrated high diagnostic accuracy for all three targets, identifying six Cryptosporidium species and four G. duodenalis assemblages, confirming its utility for routine testing in clinical laboratories [23].

Decision Workflow: Selecting Between Commercial and In-House Assays

The choice between a commercial kit and an in-house assay depends on a laboratory's resources, expertise, and diagnostic needs. The workflow below outlines key decision points.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of either commercial or in-house PCR assays relies on a foundation of core reagents and instruments. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experimental protocols.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protozoan PCR Diagnostics

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| S.T.A.R. Buffer (Stool Transport and Recovery Buffer) | Stabilizes nucleic acids in stool specimens, inhibits nucleases, and prepares samples for automated extraction. | Used in multicentre study for standardized pre-treatment of stool samples before DNA extraction [1]. |

| MagNA Pure 96 DNA and Viral NA Small Volume Kit | Automated, magnetic bead-based nucleic acid extraction system for high-throughput, reproducible DNA purification. | Employed for standardized DNA extraction from stool samples across multiple laboratories [1]. |

| TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix | Optimized buffer, enzymes, and dNTPs for fast, sensitive, and specific probe-based qPCR amplification. | Used as the core reaction mix in the validated in-house RT-PCR assays [1]. |

| Seegene StarMag Universal Cartridge Kit | Automated, bead-based extraction cartridge designed for integration with liquid handling platforms. | Utilized for high-throughput nucleic acid extraction in the validation of the Seegene Allplex GI-Parasite assay [22]. |

| Hamilton STARlet Liquid Handler | Automated liquid handling platform for performing nucleic acid extraction and PCR setup, reducing hands-on time and errors. | Integrated system for extraction and setup of the Seegene Allplex commercial multiplex PCR assay [22]. |

The choice between commercial kits and in-house assays is not a matter of one being universally superior to the other. As the data demonstrate, both pathways are capable of achieving high diagnostic performance for major protozoan parasites like Giardia duodenalis and Cryptosporidium [23] [1]. Commercial kits offer standardization, ease of use, and higher throughput, making them suitable for routine diagnostics in clinical laboratories [22]. In-house assays provide flexibility, potential cost savings, and the ability to customize targets and protocols, which is valuable for research and reference laboratories with the expertise to undertake rigorous validation [21] [5]. The decision should be guided by a careful consideration of the intended application, required targets, available resources, and the need for standardization versus flexibility. Future developments will likely focus on improving multiplexing capabilities, reducing costs, and standardizing methods to make molecular diagnostics more accessible and reliable for all protozoa.

Comparative Performance of Commercial and In-House PCR Assays

Molecular diagnostics, particularly real-time PCR (qPCR), have become central to detecting intestinal protozoa in clinical and research settings, offering superior sensitivity and specificity compared to traditional microscopy [1]. The choice between commercial kits and in-house developed assays involves a careful balance of performance, standardization, and operational flexibility. The following sections and tables provide a detailed comparison of their performance characteristics for key protozoan targets.

Table 1: Summary of Comparative Performance Studies

| Study Reference & Context | Key Findings on Commercial vs. In-House PCR | Performance Highlights (Sensitivity/Specificity) |

|---|---|---|

| Basmaciyan et al. 2021 [25](Evaluation of 7 PCR kits on 174 samples) | Commercial simplex PCRs showed better sensitivity/specificity than commercial multiplex PCRs for key protozoa. | Giardia intestinalis: 96.9%/93.6%E. histolytica: 100%/100%Cryptosporidium spp.: 100%/99.3% (Commercial SimpPCRa) |

| Di Pietra et al. 2025 [1] [4](Multicentre study on 355 samples) | Commercial (AusDiagnostics) and in-house PCR showed complete agreement for G. duodenalis. Performance varied for other targets. | Giardia duodenalis: High sensitivity/specificity (both methods)Cryptosporidium & D. fragilis: High specificity, limited sensitivity (both methods)E. histolytica: Molecular methods are critical for accurate diagnosis. |

| Köller et al. 2020 [5](Test comparison of 500 samples without a gold standard) | Commercial and in-house qPCR assays showed comparable but variable performance depending on the parasite species. | Substantial to Almost Perfect Agreement (κ) for:• Dientamoeba fragilis, Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, Ascaris lumbricoidesFair to Slight Agreement (κ) for:• Microsporidia, Cyclospora spp., Strongyloides stercoralis |

Commercial Multiplex PCR Kits: A Head-to-Head Comparison

Multiplex commercial kits offer the advantage of detecting several pathogens in a single reaction, streamlining workflow. However, their performance can vary significantly.

Table 2: Performance of Selected Commercial Multiplex PCR Kits

| Commercial Kit (Study) | Target Protozoa | Key Performance Data |

|---|---|---|

| FTD Stool Parasites(Costa et al. 2021 [26] [27]) | Cryptosporidium spp. | • Limit of Detection (LOD): 1 oocyst/g for C. parvum; 10 oocysts/g for C. hominis.• Detected all tested rare species (C. cuniculus, C. meleagridis, C. felis, etc.).• No cross-reactivity with other enteric pathogens. |

| RIDAGENE Parasitic Stool Panel(Paulos et al. 2019 [28]) | G. duodenalis, C. hominis/parvum, E. histolytica | • Reliable detection with no cross-reactivity against E. dispar and other parasites. |

| Allplex GI Parasite Assay(Paulos et al. 2019 [28]; Costa et al. 2021 [26]) | G. duodenalis, C. hominis/parvum, E. histolytica | • Second-best LOD in its category after FTD.• Required testing in triplicate to achieve optimal LOD for some targets. |

| Gastroenteritis/Parasite Panel I (Diagenode)(Paulos et al. 2019 [28]) | G. duodenalis, C. hominis/parvum, E. histolytica | • Reliable detection with no cross-reactivity against E. dispar and other parasites. |

In-House PCR Assays: Flexibility with a Need for Validation

In-house PCR assays allow laboratories to customize targets and protocols. A 2020 study comparing in-house and commercial tests without a gold standard found that they generally showed comparable performance for many parasites, though agreement varied significantly by species [5]. For Giardia duodenalis, in-house assays targeting different genes can show vastly different sensitivities, ranging from 17.5% for a gdh gene-targeting assay to 100% for an 18S rRNA gene-targeting assay, underscoring the importance of target selection and rigorous in-house validation [29].

Detailed Experimental Protocols from Key Studies

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear technical reference, this section outlines the methodologies from several pivotal studies cited in this guide.

Protocol: Comparative Evaluation of Seven Commercial Kits

This protocol is derived from the study by Basmaciyan et al. [25].

- 1. Sample Collection and DNA Extraction:

- A total of 174 DNA samples, retrospectively collected from stool samples between 2007 and 2017, were used.

- The DNA had previously been extracted from stool samples.

- 2. PCR Amplification:

- Assays Tested: Four commercial simplex PCR assays (CerTest VIASURE) and three commercial multiplex PCR assays (CerTest VIASURE, FAST-TRACK FTD Stool Parasites, and DIAGENODE Gastroenteritis/Paraiste panel I).

- Targets: Giardia intestinalis, Entamoeba spp. (with differentiation of E. histolytica and E. dispar), and Cryptosporidium spp.

- Procedure: All commercial kits were used strictly in accordance with the manufacturers' instructions and compared against the laboratory's routinely used in-house simplex PCR assays.

- 3. Data Analysis:

- Performance was evaluated by calculating the sensitivity and specificity of each commercial kit against the reference in-house methods.

Protocol: Multicentre Comparison in Italy

This protocol is based on the multicentre study by Di Pietra et al. involving 18 Italian laboratories [1] [4].

- 1. Sample Collection and Preparation:

- Cohort: 355 stool samples (230 fresh, 125 preserved in Para-Pak media) were collected consecutively.

- Microscopy: All samples were first examined by conventional microscopy (the reference method), following WHO and CDC guidelines. Fresh samples were stained with Giemsa, and fixed samples were processed with the formalin-ethyl acetate (FEA) concentration technique.

- 2. DNA Extraction:

- An automated system was used for nucleic acid purification.

- Specifically, 350 µL of Stool Transport and Recovery (S.T.A.R.) Buffer was mixed with a small amount of faecal sample. After centrifugation, the supernatant was used for DNA extraction on the MagNA Pure 96 System using the MagNA Pure 96 DNA and Viral NA Small Volume Kit (Roche).

- 3. Molecular Testing:

- Each sample was tested using a commercial RT-PCR test (AusDiagnostics) and a validated in-house RT-PCR assay.

- In-house PCR Mix: Reactions contained 5 µL of DNA extract, 12.5 µL of 2× TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix, 2.5 µL of primer-probe mix, and sterile water to a final volume of 25 µL.

- 4. Analysis:

- The results from both molecular methods were compared to each other and to the initial microscopy results.

Protocol: Eight-Way PCR Comparison for Cryptosporidium

This protocol summarizes the comprehensive method comparison by Costa et al. [26] [27].

- 1. Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction:

- The study used DNA extracts from stool samples spiked with known quantities of Cryptosporidium oocysts. A mechanical treatment step was confirmed to be essential for efficient DNA extraction from oocysts [26].

- 2. PCR Methods:

- Assays Tested: Eight real-time PCR methods were compared: four "in-house" assays and four commercial multiplex assays (RIDAGENE, FTD Stool Parasites, Amplidiag Stool Parasites, Allplex GI Parasite Assay).

- Procedure: All methods were tested on the same DNA extracts to ensure a direct comparison.

- 3. Performance Evaluation:

- Limit of Detection (LOD): Determined for both C. parvum and C. hominis.

- Specificity: Assessed by testing against a panel of rare Cryptosporidium species (C. cuniculus, C. meleagridis, C. felis, C. chipmunk, C. ubiquitum) and other enteric pathogens to check for cross-reactivity.

- Recommendation: The study recommended testing each DNA extract in at least triplicate to optimize the detection limit, as some methods only detected low oocyst concentrations in some replicates [26].

Workflow for PCR Assay Selection and Implementation

The following diagram maps the logical decision process for selecting and implementing a PCR assay for protozoan detection, based on the collective evidence from the cited studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of PCR detection for intestinal protozoa relies on a set of core reagents and tools. The table below lists essential items as utilized in the featured experiments.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Protozoan PCR Research

| Item Name & Example Source | Primary Function in Protozoan PCR | Key Considerations from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit(e.g., QIAamp Stool DNA Mini Kit, MagNA Pure Kits) | Purifies parasite DNA from complex stool matrices. | Mechanical lysis (bead beating) is often essential for breaking tough oocyst/cyst walls [26] [1]. |

| Commercial Multiplex PCR Kits(e.g., FTD Stool Parasites, RIDAGENE Panels) | Allows simultaneous detection of multiple protozoan targets in a single reaction. | Performance varies; verify limits of detection (LOD) and ability to detect rare species [26] [28]. |

| PCR Master Mix(e.g., TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix) | Provides enzymes, dNTPs, and buffer for efficient DNA amplification. | Choice is critical for in-house assays. Compatible with probe-based chemistries for multiplexing [1]. |

| Specific Primers & Probes(For in-house assays) | Binds to unique genetic sequences of the target protozoa for amplification and detection. | Target gene selection (18S rRNA, bg, tpi, gdh) drastically impacts sensitivity and specificity [29]. |

| Positive Control DNA(From reference strains or characterized samples) | Verifies the entire PCR process is working correctly. | Should include DNA from all target species to control for extraction and amplification efficiency. |

| Inhibition Control(Internal control or spiked DNA) | Detects substances in stool that can inhibit the PCR reaction. | Essential for avoiding false-negative results; may require sample dilution for accurate results [28] [29]. |

Implementing PCR Protocols: From Primer Design to Data Analysis

The accurate detection of pathogenic intestinal protozoa, which affect billions of people globally and cause significant diarrheal disease, remains a formidable challenge in clinical and research laboratories [12]. For decades, microscopic examination has been the reference standard for diagnosis, but this method is limited by requirements for experienced personnel, time-consuming procedures, and insufficient sensitivity and specificity for differentiating closely related species [13] [12]. Molecular diagnostic technologies, particularly real-time PCR (RT-PCR), have emerged as powerful alternatives, offering enhanced sensitivity and specificity, especially in non-endemic areas with low parasitic prevalence [30] [12].

Within this diagnostic landscape, laboratories must choose between adopting commercial PCR kits or developing and validating their own in-house assays. Commercial kits offer standardization and convenience, while in-house methods provide customization potential and cost efficiencies. This guide objectively compares the performance of the AusDiagnostics platform, a commercially available RT-PCR system, against in-house PCR assays and traditional microscopy for detecting intestinal protozoa, providing researchers and scientists with experimental data to inform their diagnostic and research decisions.

The AusDiagnostics platform utilizes a Multiplex Tandem PCR (MT-PCR) system, which employs a two-step amplification process [31]. The initial phase involves target enrichment through a multiplexed primary amplification using target-specific outer primer sets with a limited number of PCR cycles. This is followed by a secondary amplification where inner primers amplify a specific target region within the primary amplification product [31]. This tandem approach enhances specificity and enables the simultaneous detection of multiple pathogens.

The platform uses SYBR Green detection and reports semi-quantitative results (e.g., 1+ to 5+) rather than cycle threshold (Ct) values. Molecular target concentrations are calculated as arbitrary units relative to an internal control [31]. The system is designed for medium-throughput testing and can be integrated with automated extraction systems such as the AusDiagnostics MT-Prep [31].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Detection of Intestinal Protozoa

A 2025 multicentre study involving 18 Italian laboratories provided a direct comparison between the AusDiagnostics commercial RT-PCR test, an in-house RT-PCR assay, and traditional microscopy for detecting key intestinal protozoa in 355 stool samples [12].

Table 1: Performance Comparison for Protozoan Detection in a Multicentre Study

| Parasite | Microscopy Positives | AusDiagnostics vs. In-House PCR Agreement | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Giardia duodenalis | 285 total positives across all targets | 100% | Both molecular methods showed high sensitivity and specificity, comparable to microscopy [12]. |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | 285 total positives across all targets | High specificity, limited sensitivity | Both PCR methods showed high specificity but suboptimal sensitivity, potentially due to DNA extraction issues from the oocyst wall [12]. |

| Entamoeba histolytica | 285 total positives across all targets | Critical for accurate diagnosis | Molecular assays are essential for differentiating the pathogenic E. histolytica from non-pathogenic Entamoeba species [12]. |

| Dientamoeba fragilis | 285 total positives across all targets | Inconsistent | Detection was inconsistent, with performance varying across samples [12]. |

The study concluded that molecular methods are highly promising for diagnosing intestinal protozoan infections. The AusDiagnostics assay and the in-house method performed comparably well for G. duodenalis and Cryptosporidium spp. in fixed specimens, though the robust wall structure of protozoan oocysts continues to present a challenge for DNA extraction, affecting sensitivity [12]. Furthermore, sample preservation was a critical factor, with PCR results from preserved stool samples being superior to those from fresh samples, likely due to better DNA integrity [12].

Detection of Respiratory Pathogens and SARS-CoV-2

While the focus of this guide is protozoan detection, the platform's performance in respiratory testing provides additional context for its reliability. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the AusDiagnostics Respiratory Pathogens 16-Well Assay was updated to include SARS-CoV-2 targets.

Table 2: Performance of AusDiagnostics in Respiratory Virus Detection

| Evaluation Context | Comparative Method | Sensitivity | Specificity | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 Detection [31] | State Reference Lab RT-PCR | 125/127 (98.4%) confirmed true positive after discrepancy resolution | 2/7839 tests (0.02%) indeterminate | High reliability for SARS-CoV-2 detection with high specificity [31]. |

| SARS-CoV-2 Detection [32] | cobas 6800 (Roche) | N/A | N/A | 98.6% agreement with the reference method [32]. |

| Multiplex Respiratory Panel [32] | Allplex RV Essential Assay | N/A | N/A | 99% agreement for the detection of seven common respiratory viruses [32]. |

| SARS-CoV-2 vs. other NAT [33] | In-house E/RdRp gene assays | 100% | 92.16% | The study recommended confirmation of positive results with a second NAT due to specificity concerns [33]. |

Experimental Protocols

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

The following protocol synthesizes methodologies from the evaluated studies for the detection of intestinal protozoa using the AusDiagnostics platform [12]:

- Sample Collection: Collect stool samples in preservation media (e.g., Para-Pak, S.T.A.R. Buffer). Evidence indicates that preserved samples yield better DNA quality for PCR than fresh samples [12].

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize 1 μL of stool sample with 350 μL of S.T.A.R. buffer using a sterile loop. Incubate for 5 minutes at room temperature, then centrifuge at 2000 rpm for 2 minutes [12].

- DNA Extraction: Transfer 250 μL of the supernatant to a fresh tube and add an internal extraction control. Perform nucleic acid extraction using an automated system such as the MagNA Pure 96 System with the corresponding DNA and Viral NA kit, eluting in a predefined volume [12]. The AusDiagnostics system can also be paired with its proprietary MT-Prep extraction system [31].

AusDiagnostics MT-PCR Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the core workflow of the AusDiagnostics MT-PCR assay.

- Primary Multiplex PCR (Target Enrichment): Combine the extracted DNA with the first set of outer primers in a multiplex reaction. This step uses a small number of PCR cycles to amplify all target sequences simultaneously, enriching the specific DNA regions of interest [31].

- Secondary Tandem PCR (Specific Amplification): Use the product from the primary PCR as a template for a series of individual, single-plex secondary reactions. These employ inner primers that bind within the initially amplified product, ensuring high specificity and reducing the potential for non-specific amplification [31].

- Detection and Analysis: The secondary amplification is monitored in real-time using SYBR Green chemistry. The proprietary software automatically interprets the results based on predefined parameters, providing a semi-quantitative result (e.g., 1+ to 5+) rather than a Ct value [31] [32].

In-House PCR Protocol

For comparison, a typical in-house RT-PCR protocol for protozoan detection, as used in the multicentre study, is outlined below [12]:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a 25 μL reaction mixture containing:

- 5 μL of extracted DNA template.

- 12.5 μL of 2× TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix.

- 2.5 μL of primer and probe mix.

- Sterile water to volume.

- Amplification: Perform amplification on a real-time PCR instrument (e.g., ABI 7900HT) using the following cycling conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 10 minutes (1 cycle).

- Amplification: 95°C for 15 seconds, followed by 60°C for 1 minute (45 cycles).

- Analysis: Results are typically analyzed by manual inspection of amplification curves and Ct values, or using custom analysis software.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Parasitology

| Item | Function | Example Products/Assays |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Nucleic Acid Extractor | Standardizes and purifies DNA/RNA from complex samples like stool, critical for sensitivity. | MagNA Pure 96 System (Roche) [12], AusDiagnostics MT-Prep [31], BioRobot EZ1 (Qiagen) [33]. |

| Commercial Multiplex PCR Kits | Provides a standardized, pre-optimized system for simultaneous detection of multiple pathogens. | AusDiagnostics Intestinal Protozoa PCR [12], Respiratory Viruses 16-Well Assay [32]. |

| In-House PCR Reagents | Enables development of custom, flexible, and potentially lower-cost assays for specific targets. | TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix [12], LightMix kits [32], custom primers/probes. |

| Internal Extraction Controls | Monitors extraction efficiency and detects PCR inhibitors in samples, ensuring result reliability. | Phocine Herpes Virus (PhHV-1) [13], equine arteritis virus [32], manufacturer-provided controls. |

| Stool Transport and Preservation Media | Preserves nucleic acid integrity from sample collection to DNA extraction, vital for accuracy. | S.T.A.R. Buffer (Roche) [12], Universal Transport Medium (UTM) [31] [32], formalin-based preservatives. |

The transition from traditional microscopy to molecular methods like PCR represents a significant advancement in the diagnosis and research of intestinal protozoa [30] [13]. The data from comparative studies indicate that the AusDiagnostics platform is a robust and reliable commercial solution, demonstrating performance comparable to well-validated in-house PCR assays for targets like Giardia duodenalis [12].

The choice between a commercial kit like AusDiagnostics and an in-house PCR assay involves several considerations:

- Standardization and Throughput: AusDiagnostics offers a standardized, medium-throughput system with integrated software interpretation, reducing inter-laboratory variability and streamlining workflow [31] [32].

- Customization and Cost: In-house assays provide greater flexibility to customize targets and may offer lower per-test costs, but require significant development, validation, and continuous quality control efforts [34].

- Sensitivity Challenges: Both commercial and in-house molecular methods can face technical challenges, particularly with parasites like Cryptosporidium spp. and D. fragilis, where DNA extraction efficiency from the parasite's robust wall is a limiting factor [12].

In conclusion, the AusDiagnostics platform presents a strong commercial option for laboratories seeking a standardized, reliable, and efficient system for the molecular detection of intestinal protozoa and other pathogens. Researchers must weigh the benefits of standardization and ease-of-use against the need for customization and cost considerations when selecting the appropriate methodological path for their specific application.

The decision between developing in-house assays or purchasing commercial tests represents a significant crossroads in molecular diagnostics and research. While commercial kits offer the advantage of rapid implementation, often with regulatory approvals like CE marking or FDA clearance, they can be costly and may lack flexibility for specific research applications [35]. Conversely, in-house or laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) provide researchers with complete control over the assay design, including the critical aspects of primer and probe selection, enabling customization for specific pathogens, including intestinal protozoa, and adaptation to local requirements [35]. This flexibility is particularly crucial for targeting rare pathogens or responding rapidly to emerging infectious threats, as demonstrated during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic [35]. However, this control comes with the substantial responsibility of rigorous internal validation to ensure the assay's reliability, accuracy, and reproducibility, a process that demands meticulous planning and execution [35].

Within parasitology, this debate is highly relevant. Studies comparing commercial and in-house molecular tests for protozoan detection, such as Giardia duodenalis, Cryptosporidium spp., and Entamoeba histolytica, have shown that both pathways can achieve high performance. For instance, one multicentre study found complete agreement between a commercial RT-PCR test and an in-house RT-PCR assay for detecting G. duodenalis [1]. The choice between these pathways ultimately depends on a balance of factors, including diagnostic needs, cost considerations, available expertise, and the requirement for standardization versus customization [1] [35].

Performance Comparison: Commercial vs. In-House Molecular Assays

Independent evaluations provide critical data for researchers deciding between commercial and in-house molecular assays. The performance of these platforms can vary significantly depending on the target pathogen, the sample type, and the specific technologies employed.

Table 1: Comparative Diagnostic Performance of Commercial and In-House PCR Assays for Intestinal Protozoa

| Pathogen | Assay Type | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Key Findings and Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giardia duodenalis | In-house RT-PCR [1] | High (Precise value not given) | High (Precise value not given) | Complete agreement with a commercial AusDiagnostics test; both demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity similar to microscopy [1]. |

| Commercial AusDiagnostics RT-PCR [1] | High (Precise value not given) | High (Precise value not given) | ||

| Cryptosporidium spp. | In-house RT-PCR [1] | Limited | High | Limited sensitivity likely due to inadequate DNA extraction from the robust oocyst wall; highlights technical challenges [1]. |

| Commercial AusDiagnostics RT-PCR [1] | Limited | High | ||

| Entamoeba histolytica | In-house & Commercial RT-PCR [1] | Data not specified | Data not specified | Molecular assays are critical for accurate diagnosis, as they can differentiate the pathogenic E. histolytica from non-pathogenic species like E. dispar, which is impossible by microscopy [1]. |

| Dientamoeba fragilis | In-house & Commercial RT-PCR [1] | Limited | High | Detection was inconsistent, with limited sensitivity, again potentially linked to DNA extraction efficiency [1]. |

Further comparisons of commercial multiplex assays reveal that performance is not uniform across platforms. A 2019 evaluation of four commercial multiplex real-time PCR assays showed a wide range of diagnostic sensitivities for Cryptosporidium hominis/parvum (53-88%) and Giardia duodenalis (68-100%) [36]. This underscores the importance of independent verification, as the claimed performance of a commercial test may not always be replicated in every laboratory setting due to variables such as staff competency, equipment maintenance, and workflow systems [35].

Experimental Protocol for Comparative Studies

The methodology for a typical comparative study, as seen in a multicentre Italian trial, involves several key stages to ensure a fair and objective assessment [1]:

- Sample Collection and Preparation: A large number of stool samples (e.g., 355) are collected, including both freshly collected samples and those stored in preservation media to evaluate the impact of storage on DNA integrity [1].

- Reference Method Testing: All samples are first examined using a conventional reference method, such as microscopic examination following WHO and CDC guidelines, to establish a baseline diagnosis [1].

- Molecular Testing: Samples are then analyzed in parallel using the commercial and in-house molecular methods. This involves:

- DNA Extraction: Using automated systems (e.g., MagNA Pure 96 System, Roche) and specific buffers (e.g., S.T.A.R. Buffer) to ensure standardized nucleic acid purification. The inclusion of an internal extraction control is critical [1].

- PCR Amplification: For in-house assays, a reaction mix is prepared containing the extracted DNA, a master mix (e.g., TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix), and the custom-designed primer/probe mix. Commercial kits are used according to the manufacturer's instructions [1] [36].

- Discrepancy Analysis: Samples with discordant results between the different methods are resolved using an alternative, predefined method, such as sequencing, to determine the true status of the infection [35].

Primer and Probe Selection: Core Principles for In-House Assay Design

The heart of a robust in-house PCR assay lies in the careful selection and design of primers and probes. This process requires a strategic approach from target selection to experimental validation.

Target Gene Identification and Bioinformatic Analysis

The initial step involves selecting a genetically stable and species-specific genomic target region. Common targets for protozoan parasites include the small subunit ribosomal RNA (18S SSU rRNA) gene or the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions [37] [38]. For example, the ITS-1 region is often chosen for its relatively low mutation rates and considerable interspecies variation, which aids in differentiating closely related species [38]. To begin design:

- Retrieve Sequences: Obtain multiple target gene sequences for the pathogen of interest and related species from public databases like GenBank.

- Perform Multiple Sequence Alignment: Use bioinformatics tools (e.g., Clustal Omega) to identify conserved regions suitable for primer binding and variable regions that allow for species differentiation [38].

- Check Specificity In Silico: Use the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) to verify the theoretical specificity of the designed oligonucleotides against the entire nucleotide database [38].

Experimental Validation and Optimization

Following in silico design, primers and probes must be empirically validated.

- Optimization of Reaction Conditions: Systematically test different annealing temperatures (e.g., 50°C to 65°C), primer concentrations (e.g., testing ratios of outer to inner primers of 1:2, 1:4, 1:6, and 1:8 for LAMP assays), and incubation times to establish optimal reaction conditions [38].

- Specificity Testing: Challenge the assay with DNA from a panel of closely related non-target organisms and common commensals to ensure no cross-reactivity occurs [38].

- Limit of Detection (LOD) Determination: Establish the lowest concentration of the target that can be reliably detected by testing serial dilutions of a known positive control or a synthetic standard [36] [38].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for PCR Assay Development

| Reagent / Material | Function in Assay Development | Examples and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit | Purifies DNA/RNA from complex sample matrices like stool. Efficiency is critical for sensitivity [1]. | QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (QIAGEN); MagNA Pure 96 System (Roche). The choice of kit can significantly impact results [1] [38]. |

| PCR Master Mix | Provides the enzymes, dNTPs, and optimized buffer for DNA amplification. | TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher); ddPCR Supermix for Probes (Bio-Rad). The master mix can affect accuracy [1] [39]. |

| Primers & Probes | Specifically bind to and detect the target DNA sequence. The core of the in-house assay. | Designed using Primer Explorer v5 or similar software; synthesized to HPLC-grade purity [38]. |

| Positive Control | Contains the target sequence to verify the assay is functioning correctly. | Genomic DNA from cultured parasites, cloned plasmid DNA, or synthetic oligonucleotides [38]. |

| Internal Control | Distinguishes true target negatives from PCR inhibition. | A non-competitive synthetic sequence or a control gene (e.g., β-actin) spiked into the reaction [35] [38]. |

Diagram 1: Workflow for primer and probe selection and validation.

The Assay Validation Framework: Ensuring Reliability

A comprehensive validation plan is mandatory to confirm that an in-house assay is fit for its intended purpose. The process involves two key stages: verification of individual performance characteristics and ongoing validation to maintain the assay's verified status during routine use [35].

Key Analytical Performance Parameters

The following parameters must be systematically evaluated, a process guided by initiatives like the MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines [35].