Breaking the Wall: Advanced Strategies for DNA Extraction from Robust Parasite Oocysts

Efficient DNA extraction from robust parasite oocysts, such as Cryptosporidium and Giardia, is a critical bottleneck in molecular diagnostics and research.

Breaking the Wall: Advanced Strategies for DNA Extraction from Robust Parasite Oocysts

Abstract

Efficient DNA extraction from robust parasite oocysts, such as Cryptosporidium and Giardia, is a critical bottleneck in molecular diagnostics and research. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of current challenges and solutions, covering the structural barriers of oocysts, a comparative evaluation of mechanical, thermal, and chemical lysis methods, and data-driven optimization of commercial and in-house protocols. It further details systematic troubleshooting for inhibitor removal and DNA integrity, alongside multi-laboratory validation data for PCR, LAMP, and metagenomic applications. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes foundational knowledge with practical, validated protocols to enhance detection sensitivity and accelerate therapeutic development.

Understanding the Fortress: The Structural and Technical Barriers to Oocyst Lysis

FAQs: Overcoming the Oocyst Wall in Nucleic Acid Isolation

Q1: What makes the oocyst wall such a significant barrier to effective DNA extraction?

The oocyst wall is a complex, multi-layered structure designed to protect the parasite in harsh environmental conditions. Research on Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts has shown that the wall consists of a surface glycocalyx, a lipid hydrocarbon layer, a protein layer, and structural polysaccharides [1]. The inner layer is rich in cysteine-rich oocyst wall proteins (COWPs) that form extensive disulfide bonds, creating a rigid structure that resists mechanical force and liquid intrusion, thereby protecting the internal sporozoites [1]. This robust construction physically shields the genetic material and makes the wall resistant to many standard lysis methods, leading to low DNA yield and potential PCR inhibition if not properly disrupted.

Q2: What are the most effective methods for disrupting the resilient oocyst wall?

The most effective strategies involve combining mechanical, chemical, and thermal forces. Key methods include:

- Glass-bead grinding: Vortexing oocysts in a tube with sterile glass beads (e.g., 4-mm diameter) for approximately 10 minutes until rupture is confirmed microscopically [2].

- Freeze-thaw cycles: Repeatedly freezing oocysts in liquid nitrogen followed by thawing at 65°C. One study used 15 cycles for Cryptosporidium oocysts [2], while another used six cycles for oocyst walls in a lysis buffer [1].

- Boiling with optimized incubation: Boiling for 10 minutes, coupled with extended incubation with Proteinase K (up to 3 hours at 55°C), has proven effective, especially for Cryptosporidium in fecal samples [3].

- Advanced dedicated devices: Using specialized equipment like the OmniLyse device can achieve efficient lysis within 3 minutes, as demonstrated in metagenomic studies on lettuce [4].

Q3: How can I improve DNA recovery from low numbers of oocysts in complex sample matrices like soil or feces?

For complex matrices, an initial oocyst concentration step prior to DNA extraction is crucial. In soil samples, flotation in high-density sucrose solution has proven highly effective for concentrating Cyclospora cayetanensis oocysts, enabling detection of as few as 10 oocysts in 10-gram soil samples [5]. For fecal samples, which contain PCR inhibitors like bilirubin and bile acids, washing the stool sample three times in sterile distilled water prior to DNA isolation can significantly reduce inhibition [2]. Furthermore, using a small elution volume (50-100 µl) during the final step of kit-based DNA extraction concentrates the nucleic acids, improving detectability [3].

Q4: Which commercial DNA extraction kits are suitable for oocysts, and how can their protocols be optimized?

Several commercial kits can be effective when their protocols are amended for oocysts. The QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen), when used with a protocol amended to include a 10-minute boiling step for lysis and a 5-minute incubation with the InhibitEX tablet, showed 100% sensitivity for detecting Cryptosporidium in feces, up from 60% with the standard protocol [3]. For soil samples, the FastDNA SPIN Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals), Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microbe Midiprep Kit (Zymo Research), and DNeasy PowerMax Soil Kit (Qiagen) have been evaluated, though for C. cayetanensis, traditional sucrose flotation outperformed these kits in recovery [5].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Consistently low DNA yield | Inefficient wall disruption; DNA loss during precipitation. | Incorporate a mechanical disruption step (e.g., bead beating). Use pre-cooled ethanol for precipitation and elute in a small volume (50-100 µl) [3]. |

| PCR inhibition | Co-purification of inhibitors from complex matrices (stool, soil). | Pre-wash samples (e.g., stool with distilled water) [2]. Use inhibitor-removal tablets in kits and extend incubation time with them to 5 minutes [3]. |

| Inconsistent results between replicates | Heterogeneous distribution of oocysts in sample; incomplete lysis. | Ensure sample is well-homogenized. Standardize lysis time/temperature; monitor breakage microscopically when possible [2]. |

| Failure to detect low-level infections | Insensitive DNA extraction method; lack of oocyst concentration. | Implement an oocyst concentration step (e.g., sucrose flotation for soil) [5]. Use a whole genome amplification step post-extraction to increase DNA for sequencing [4]. |

Quantitative Data: Comparing Method Efficacy

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Extraction and Oocyst Recovery Methods

| Method / Kit | Sample Matrix | Key Protocol Steps | Limit of Detection | Key Findings / Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sucrose Flotation + qPCR [5] | Silt Loam Soil | Flotation in saturated sucrose, DNA extraction, qPCR. | 10 oocysts in 10 g soil (1 oocyst/g) | Outperformed 3 commercial kits; all 5 replicates with 100 oocysts were positive. |

| Amended QIAamp DNA Stool Kit [3] | Human Feces | Boiling (10 min), extended InhibitEX incubation, pre-cooled ethanol, small elution volume. | ≈2 oocysts/cysts | Sensitivity for Cryptosporidium increased from 60% to 100% after protocol optimization. |

| OmniLyse Lysis + WGA [4] | Lettuce | Surface washing, OmniLyse lysis (3 min), acetate precipitation, whole genome amplification. | 100 oocysts in 25 g lettuce | Enabled metagenomic sequencing; suitable for multiple parasites (C. parvum, G. duodenalis, T. gondii). |

| Glass Bead Grinding [2] | General Oocysts | Vortexing with 4-mm glass beads in TE buffer, phenol-chloroform extraction. | Not Specified | Rupture monitored microscopically; process took ~10 minutes. |

| Freeze-Thaw Cycles [2] [1] | Purified Oocysts | Multiple cycles in LN2 and 65°C water bath (e.g., 6-15 cycles). | Not Specified | Traditional but time-consuming; can be difficult to adapt for field testing [4]. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Oocyst DNA Isolation | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Proteinase K | Digestes structural proteins in the oocyst wall, aiding in its breakdown. | Used at 55°C for 3 hours for helminths [2]; critical for efficient lysis. |

| Saturated Sucrose Solution | Flotation medium to concentrate oocysts from large-volume or complex samples like soil. | Enables separation of oocysts from denser debris based on buoyancy [5]. |

| InhibitEX Tablets / Similar | Binds and removes PCR inhibitors (e.g., bilirubin, bile acids) common in fecal samples. | Extended incubation for 5 minutes improves inhibitor removal [3]. |

| Percoll | Density gradient medium for purifying oocyst walls after excystation. | Used at 70% concentration to aspirate clean oocyst walls post-centrifugation [1]. |

| CTAB Buffer | Lysis buffer used in conjunction with physical disruption methods for DNA release. | Used with proteinase K after glass-bead grinding [2]. |

| Sodium Taurocholate | Bile salt used to trigger excystation (opening) of oocysts in vitro. | Used at 0.75% with trypsin to stimulate excystation for wall isolation [1]. |

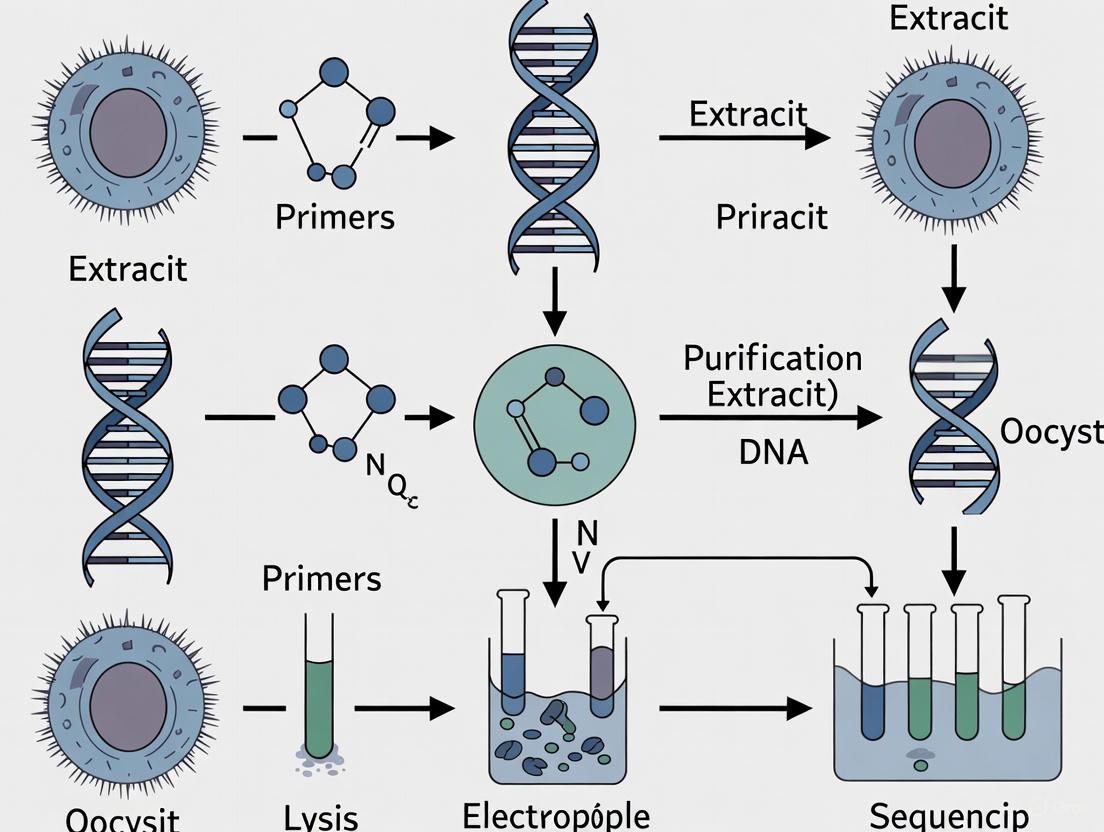

Experimental Workflow and Oocyst Wall Structure

Experimental Workflow for Oocyst DNA Isolation

Oocyst Wall Structural Barriers

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide: DNA Extraction from Robust Parasite Oocysts

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when extracting DNA from the resilient oocysts of Cryptosporidium, Giardia, and Cyclospora for downstream applications like PCR and NGS.

Table 1: Common Problems and Solutions in Parasite DNA Extraction

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low DNA Yield | Inefficient lysis of robust oocyst/cyst walls [6]. | Use a mechanical lysis device (e.g., OmniLyse) for rapid, efficient disruption [6]. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles, which are time-consuming and less effective [6]. |

| DNA pellets are overdried, making resuspension difficult [7]. | Limit pellet drying time to <5 minutes and avoid vacuum suction devices. Resuspend in 8 mM NaOH or TE buffer with periodic pipetting and incubation at 37-45°C [7]. | |

| DNA Degradation | Sample not processed immediately or stored improperly, allowing nucleases to act [8]. | Process samples immediately or flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen. Store at -80°C. For fibrous tissues, cut into the smallest possible pieces [8]. |

| Insufficient DNA for NGS | Low starting number of (oo)cysts yields insufficient template [6]. | Incorporate a whole genome amplification (WGA) step post-extraction to generate microgram quantities of DNA required for NGS libraries [6]. |

| Inhibition of Downstream PCR | Carryover of purification reagents or polysaccharides [7]. | Reprecipitate the DNA to remove contaminants like phenol or excess salt. Ensure proper washing steps during column-based purification [7]. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Oocyst DNA Workflows

| Reagent / Tool | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| OmniLyse Device | Provides rapid (3-minute) and efficient mechanical lysis of tough oocyst walls, superior to traditional chemical or thermal methods [6]. |

| Whole Genome Amplification (WGA) Kits | Amplifies nanogram quantities of extracted DNA to the microgram levels required for building NGS libraries, crucial for low-input samples [6]. |

| Proteinase K | Digests proteins and inactivates nucleases during the initial lysis step, helping to protect DNA integrity [8]. |

| Buffered Peptone Water + Tween | Used as a wash buffer to dissociate oocysts from the surface of fresh produce like lettuce for sample preparation [6]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is DNA extraction from protozoan oocysts like Cryptosporidium particularly challenging? The oocysts possess a robust, bilayered wall that is notoriously difficult to break open. This wall contains highly cross-linked proteins, such as tyrosine-rich proteins and cysteine-rich oocyst wall proteins (OWPs), which provide structural strength and resistance to many chemical and physical lysis methods [9]. Inefficient lysis is a primary bottleneck for sensitive detection.

Q2: My extracted DNA won't go back into solution. What can I do? This is often due to overdrying the DNA pellet. You can try incubating the pellet in 8 mM NaOH or TE buffer at 37°C to 45°C with periodic pipetting. It may take several hours or overnight incubation to fully resuspend. Avoid overdrying by limiting air-drying time to under 5 minutes [7].

Q3: What is an advantage of using metagenomic NGS over traditional PCR for detecting these parasites? Traditional PCR requires prior knowledge of the pathogen and typically targets one organism at a time. Metagenomic NGS is a culture-independent, comprehensive approach that can simultaneously identify and differentiate multiple parasites (e.g., C. parvum, G. duodenalis, T. gondii) in a single test without pre-specifying the targets, making it ideal for outbreak investigation and surveillance [6].

Q4: Are there any low-cost alternatives for initial screening of (oo)cysts? Yes, a smartphone-based microscopic method has been developed as a low-cost alternative for simultaneous detection of Cryptosporidium oocysts and Giardia cysts on vegetables and in water. This method uses a ball lens, white LED, and Lugol's iodine staining and has shown performance comparable to commercial microscopy methods, making it suitable for resource-limited settings [10].

Experimental Protocol: Metagenomic Detection from Fresh Produce

The following detailed protocol is adapted from a study that successfully identified as few as 100 oocysts of C. parvum in 25g of lettuce using metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) [6].

Sample Preparation and Spiking:

- Place a 25g leaf of romaine lettuce in a sterile container.

- Spike the lettuce surface with a known number of oocysts/cysts (e.g., 100-100,000) in 1 ml of PBS, delivered dropwise.

- Allow the spiking fluid to air-dry completely (approx. 15 minutes).

Elution and Concentration:

- Transfer the spiked leaf to a stomacher bag with 40 ml of buffered peptone water supplemented with 0.1% Tween.

- Homogenize in a stomacher at 115 rpm for 1 minute.

- Pass the fluid through a custom 35 μm filter under vacuum to remove plant debris.

- Centrifuge the filtrate at 15,000 x g for 60 minutes at 4°C. Discard the supernatant.

Lysis and DNA Extraction:

- Critical Step: Lysate the oocyst/cyst pellet using the OmniLyse device to achieve rapid (3-minute) and efficient mechanical disruption [6].

- Extract DNA from the lysate using acetate precipitation or a commercial kit designed for tough-to-lyse organisms.

- DNA Amplification: Subject the extracted DNA to Whole Genome Amplification (WGA) to generate sufficient DNA (0.16–8.25 μg) for NGS library construction.

Sequencing and Bioinformatics:

- Prepare sequencing libraries from the amplified DNA.

- Sequence using a platform such as MinION (Oxford Nanopore) or Ion GeneStudio S5.

- Analyze the generated fastq files using a bioinformatic platform (e.g., CosmosID webserver) for the identification and differentiation of parasites in the metagenome.

Workflow and Troubleshooting Diagrams

Parasite Oocyst DNA Workflow

Troubleshooting Logic for Detection Failure

Common Failure Points in Standard DNA Extraction Protocols

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Addressing DNA Extraction from Robust Parasite Oocysts

1. Why is my DNA yield from parasite oocysts so low despite using commercial kits?

Standard commercial DNA extraction kits are often optimized for mammalian cells or bacteria and fail to effectively disrupt the robust oocyst and cyst walls of parasites like Cryptosporidium and Giardia [4]. These resilient structures require specialized mechanical or physical disruption methods. Traditional chemical lysis alone is insufficient for complete cell wall breakdown, leading to poor DNA yield [11]. Solution: Implement a mechanical disruption step. Bead mill homogenization using 1.0 mm glass beads at 6 m/s for 40 seconds (repeated twice) significantly improves oocyst wall breakage [11]. Alternatively, the OmniLyse device provides rapid, efficient lysis within 3 minutes, making it suitable for tough-walled parasites [4].

2. How do PCR inhibitors affect my downstream applications, and how can I remove them?

Parasite samples from feces, soil, or sediment often contain complex polysaccharides, humic acids, and other compounds that co-purify with DNA and inhibit enzymatic reactions in PCR and sequencing [12]. These inhibitors cause false negatives, reduced sensitivity, and quantification errors in molecular assays. Solution: Use effective purification methods post-extraction. Sephadex G-200 spin column purification effectively removes PCR-inhibiting substances while minimizing DNA loss [12]. For fecal samples, the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit is specifically designed to remove these inhibitors [13].

3. Why is there a discrepancy between oocyst counts and DNA-based quantification?

Microscopic oocyst counts and DNA-based quantification measure different biological aspects. Oocyst counts only detect mature transmissive stages, while DNA-based methods detect all life cycle stages (asexual and sexual), including developing parasites in host tissues [11]. This explains why DNA may be detected earlier in infection cycles before oocysts appear in feces, and why DNA intensity can be a better predictor of host health impact than oocyst counts alone [11].

4. What is the impact of DNA shearing on downstream applications?

Vigorous or prolonged mechanical disruption can fragment DNA, compromising applications requiring high-molecular-weight DNA, such as long-read sequencing [12]. Solution: Optimize homogenization parameters. For bead mill homogenization, use lower speeds and shorter durations (30-120 seconds) to maximize recovery of high-molecular-weight DNA (16-20 kb) while maintaining efficient cell lysis [12].

Table 1: Common Failure Points and Optimized Solutions for Parasite DNA Extraction

| Failure Point | Impact on Results | Optimized Solution | Evidence of Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inefficient oocyst/cyst lysis | Low DNA yield, false negatives | Mechanical disruption (bead beating, OmniLyse device) | Detection of as few as 100 C. parvum oocysts from lettuce after OmniLyse treatment [4] |

| Co-purification of inhibitors | PCR inhibition, quantification errors | Sephadex G-200 column purification; inhibitor removal kits | Successful PCR from soil/sediment samples with high organic matter content [12] |

| DNA shearing/fragmentation | Poor performance in long-read sequencing | Optimized bead mill homogenization (low speed, short duration) | Recovery of high-molecular-weight DNA (16-20 kb) from complex samples [12] |

| Inadequate sample processing | Variable recovery, poor reproducibility | Centrifugal flotation with NaNO₃ prior to DNA extraction | Improved detection of T. gondii in cat feces [13] |

| Suboptimal purification method | Low purity (A260/280 ratios) | Silica-based column purification vs. precipitation methods | Purity improvement from 0.764 to 1.735 in blood samples [14] |

Table 2: Comparison of DNA Extraction Methods for Different Sample Types

| Extraction Method | Recommended Sample Types | Key Advantages | Limitations for Parasite Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bead mill homogenization + SDS-chloroform | Soil, sediment, environmental samples | High lysis efficiency, effective for tough-walled organisms | Requires optimization to prevent DNA shearing [12] |

| OmniLyse CTL buffer + acetate precipitation | Parasite oocysts on leafy greens, water samples | Rapid (3-min) lysis, compatible with downstream WGA and sequencing | Specialized equipment required [4] |

| Heat lysis in TE buffer | Water samples with Cryptosporidium oocysts | Rapid, simple, no commercial kits required, suitable for LAMP | No purification step, potential inhibitor carryover [15] |

| Modified commercial kits with bead beating | Fecal samples with parasite stages | Standardized protocol with improved lysis efficiency | Higher cost per sample, may require optimization [11] |

| CTAB-based extraction | Plant tissues, microlepidoptera | Effective for polysaccharide-rich samples | Labor-intensive, multiple purification steps required [16] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Metagenomic Detection of Parasites from Leafy Greens

This protocol enables sensitive detection of protozoan parasites from fresh produce using optimized lysis and metagenomic sequencing [4]:

Sample Preparation: Place 25g lettuce leaves in sterile container. Spike with 1ml containing 100-100,000 oocysts of target parasites (C. parvum, C. hominis, G. duodenalis, T. gondii). Air dry for 15 minutes.

Microbe Wash: Transfer spiked leaves to stomacher bag with 40ml buffered peptone water + 0.1% Tween. Homogenize at 115rpm for 1 minute.

Filtration and Concentration: Pass fluid through custom-made 35μm filter under vacuum. Pellet oocysts by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 60 minutes at 4°C. Discard supernatant.

Mechanical Lysis: Resuspend pellet and lyse using OmniLyse device for 3 minutes for efficient oocyst wall disruption.

DNA Extraction and Precipitation: Extract DNA using acetate precipitation. Add 1/10 volume 3M sodium acetate (pH 5.2) and 2.5 volumes cold 100% ethanol. Precipitate at -20°C for 1 hour.

Whole Genome Amplification: Amplify extracted DNA to generate 0.16-8.25μg (median 4.10μg) for sequencing.

Sequencing and Analysis: Perform metagenomic sequencing using MinION or Ion GeneStudio S5. Analyze fastq files with CosmosID webserver for parasite identification.

Protocol 2: Rapid Cryptosporidium Detection Avoiding Commercial Kits

This simplified protocol enables rapid detection without commercial kits, suitable for field applications [15]:

Oocyst Isolation: Concentrate Cryptosporidium oocysts from 10mL water samples using immunomagnetic separation (IMS) with streptavidin-coated magnetic beads and biotinylated anti-Cryptosporidium antibodies.

Heat Lysis: Isolate oocysts magnetically and resuspend in TE buffer (10mM Tris, 0.1mM EDTA, pH 7.5). Incubate at 95°C for 15 minutes to lyse oocysts.

Direct Amplification: Use 2-5μl of crude lysate directly in colorimetric LAMP reactions without nucleic acid purification.

Detection: Employ WarmStart Colorimetric LAMP 2× Master Mix with primers targeting Cryptosporidium-specific genes. Incubate at 65°C for 30-60 minutes. Positive samples change from pink to yellow.

Sensitivity Validation: This method detects as low as 5 oocysts per 10mL tap water without matrices and 10 oocysts per 10mL with simulated matrices (added mud).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Optimized Parasite DNA Extraction

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| OmniLyse device | Mechanical disruption of robust oocyst walls | Leafy greens, environmental samples [4] |

| Bead beating matrix (1.0mm glass beads) | Physical lysis of resilient parasite forms | Fecal samples, soil, sediment [11] |

| Sephadex G-200 | Removal of PCR inhibitors (humic acids, polysaccharides) | Soil, sediment, fecal samples with high inhibitor content [12] |

| QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit | Optimized inhibitor removal for fecal samples | Human and animal fecal specimens with parasite stages [13] |

| CTAB buffer | Effective lysis for polysaccharide-rich samples | Plant tissues, microlepidoptera, samples with high carbohydrate content [16] |

| Chelex-100 resin | Rapid, cost-effective DNA extraction | Dried blood spots, large population studies [17] |

| WarmStart Colorimetric LAMP Kit | Isothermal amplification for field detection | Resource-limited settings, rapid screening [15] |

| NucleoSpin Soil Kit | DNA extraction from inhibitor-rich samples | Soil, sediment, environmental samples with parasites [11] |

Workflow Visualization

DNA Extraction Workflow for Parasite Oocysts

Key Technical Considerations

When extracting DNA from robust parasite oocysts, several technical aspects require careful attention:

Mechanical Disruption Parameters: The efficiency of mechanical methods depends on optimal parameter selection. For bead beating, use 1.0mm glass beads at 6m/s for 40 seconds with two disruption cycles [11]. Lower speeds and shorter durations (30-120 seconds) maximize DNA size while maintaining lysis efficiency [12].

Inhibitor Removal Specificity: Different purification methods target specific inhibitors. Sephadex G-200 effectively removes humic acids from soil, while silica-based columns with inhibitor removal technology are optimal for fecal samples [12] [13].

Sample-Specific Optimization: Extraction efficiency varies significantly by sample type. Leafy greens require buffer washes with 0.1% Tween [4], while soil samples need phosphate-buffered SDS-chloroform mixtures [12]. Cat feces for T. gondii detection benefit from NaNO₃ flotation prior to DNA extraction [13].

Validation Methods: Always validate extraction efficiency using appropriate controls. Spike recovery experiments with known oocyst numbers (e.g., 100-100,000 oocysts) quantify method sensitivity [4]. Compare DNA-based quantification with microscopic counts to assess extraction completeness [11].

Impact of Oocyst Robustness on Downstream Molecular Analyses (PCR, qPCR, NGS)

The robust structure of parasite oocysts, particularly those of Cryptosporidium and other related protozoans, presents a significant barrier to effective molecular analysis. The oocyst wall is a complex, multi-layered structure designed to protect the genetic material within from extreme environmental conditions, including chemical disinfectants and physical stress [1]. This very robustness, however, hampers diagnostic and research efforts by making it difficult to extract sufficient quality DNA for downstream applications like PCR, qPCR, and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS). This technical support article addresses the specific challenges posed by resilient oocysts and provides validated troubleshooting guidelines and protocols to ensure successful molecular analyses.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Problems in Oocyst Molecular Analysis

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low DNA yield from oocysts | Inefficient lysis of the robust oocyst wall [6] [1] | Implement a mechanical lysis step (e.g., bead beating, freeze-thaw cycles) prior to chemical lysis. Use specialized lysis devices like the OmniLyse [6]. |

| Inhibition in downstream PCR/qPCR | Co-purification of inhibitors from sample matrix or oocyst remnants [18] | Dilute the DNA template. Include additional purification steps (e.g., silica-column purification, ethanol precipitation). Use inhibitor-resistant polymerase enzymes. |

| High human/background DNA in metagenomic NGS | Overwhelming host DNA in clinical or tissue samples obscures microbial reads [19] | Use DNA extraction kits with human DNA depletion steps (e.g., modified Ultra-Deep Microbiome Prep protocol) [19]. |

| Inconsistent qPCR results across instruments | Platform-specific variations in chemistry and detection [18] | Validate and calibrate the qPCR assay on the specific instrument platform in use. Do not assume perfect cross-platform robustness [18]. |

| Failure to detect low-abundance parasites in food samples | Low oocyst count and inefficient DNA recovery from complex matrices [6] | Use whole genome amplification post-extraction to increase DNA for sequencing. Employ metagenomic NGS with robust bioinformatic analysis [6]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is DNA extraction from oocysts particularly challenging?

The oocyst wall is a formidable structure composed of a lipid-hydrocarbon layer, a protein layer, and structural polysaccharides, with an inner layer of cysteine-rich proteins that form rigid disulfide bonds [1]. This structure is evolutionarily designed to resist mechanical and chemical stress, which consequently resists standard DNA extraction protocols. Traditional methods often fail to break this wall completely, leading to low DNA yield.

Q2: My qPCR assay works on one instrument but fails on another. Why?

qPCR is a sensitive technique whose performance can be affected by the specific instrument platform. A study on GMO testing found that different qPCR instruments from various suppliers (e.g., Applied Biosystems, Roche, Stratagene, Bio-Rad) can show significant variations in quantification results, even with the same validated method and DNA sample [18]. This is due to differences in excitation sources, detectors, thermocycling systems, and optical systems. It is crucial to re-validate your assay on the specific qPCR instrument you plan to use.

Q3: When should I use NGS over qPCR for oocyst analysis?

The choice depends on your goal. qPCR is the preferred method for the rapid, sensitive, and cost-effective detection of a known, specific parasite. It is ideal for routine screening and quantification [20] [21]. In contrast, NGS is a hypothesis-free approach that should be used for discovery and comprehensive profiling, such as identifying novel parasite species, detecting multiple unknown pathogens simultaneously, or conducting in-depth genomic studies [6] [21]. The two techniques are often complementary, with qPCR used to validate NGS findings [22] [20].

Q4: How can I improve the detection of parasitic DNA in samples with high host background?

For samples like infected tissue, where host DNA can constitute over 99% of the total DNA, a standard extraction will not yield sufficient microbial DNA for sequencing. A modified DNA extraction protocol that includes steps for host DNA depletion is necessary. One optimized protocol for tissue involves prolonging the proteinase K digestion step and repeating the human cell lysis and DNA degradation steps, which can achieve an additional ~10-fold reduction in human DNA [19].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Optimized Metagenomic NGS Workflow for Parasite Detection on Lettuce

This protocol, adapted from a 2025 study, details a method for sensitive detection of protozoan parasites from fresh produce [6].

Sample Preparation and Oocyst Recovery:

- Take 25g of lettuce leaves.

- Spike with oocysts/cysts (e.g., C. parvum, G. duodenalis) or process uninoculated samples for surveillance.

- Place in a stomacher bag with 40ml of buffered peptone water with 0.1% Tween.

- Homogenize in a stomacher at 115 rpm for 1 minute.

- Filter the fluid through a custom 35μm filter under vacuum to remove plant debris.

- Centrifuge the filtrate at 15,000 x g for 60 minutes at 4°C. Discard the supernatant.

Efficient Oocyst Lysis:

- Critical Step: Resuspend the pellet and lysate using the OmniLyse device. This device ensures rapid and efficient mechanical lysis of the robust oocyst/cyst walls, achieving lysis within 3 minutes [6]. This is superior to traditional methods like repeated freeze-thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen or heat treatment, which can be time-consuming or damage DNA.

DNA Extraction and Whole Genome Amplification (WGA):

- Extract DNA from the lysate using acetate precipitation.

- To overcome low DNA yield from limited oocysts, subject the extracted DNA to Whole Genome Amplification (WGA). This generates microgram quantities of DNA (e.g., a median of 4.10 μg) required for NGS library preparation [6].

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Prepare a sequencing library using the amplified DNA.

- Sequence the library using a platform such as the MinION (Oxford Nanopore Technologies) or the Ion GeneStudio S5 [6].

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Upload the generated fastq files to a bioinformatic analysis platform (e.g., CosmosID).

- Identify and differentiate parasites at the genus, species, and genotype levels within the metagenome [6].

The following workflow diagram illustrates this complete process:

Optimized DNA Extraction from Infected Tissue with Human DNA Depletion

This protocol is designed for tissue biopsies where microbial DNA is scarce compared to host DNA [19].

Sample Processing:

- Weigh the tissue biopsy and mince it thoroughly.

Modified Human DNA Depletion and Microbial DNA Extraction:

- Use the Ultra-Deep Microbiome Prep kit (Molzym) with the following key modifications to the manufacturer's protocol:

- Prolonged Digestion: Extend the first incubation with proteinase K from 10 minutes to 20 minutes.

- Repeated Lysis: After pelleting, resuspend the sample in 1 mL of TSB buffer. Repeat the entire lysis of human cells and degradation of extracellular DNA step.

- Complete the remainder of the kit's procedure for the enrichment and extraction of microbial DNA.

- Use the Ultra-Deep Microbiome Prep kit (Molzym) with the following key modifications to the manufacturer's protocol:

Quality Control with qPCR:

- Assess the efficiency of human DNA depletion by performing a qPCR assay for a human-specific gene (e.g., human β-globin, HBB).

- Assess the preservation of microbial DNA by performing a qPCR assay for a target microbial gene (e.g., the nuc gene for S. aureus).

- The modified protocol should show a significant increase in Ct value for the human gene compared to the standard protocol, indicating successful depletion [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for Oocyst DNA Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| OmniLyse Device | Rapid, mechanical lysis of robust oocyst and cyst walls [6]. | Lysis of Cryptosporidium oocysts from food samples prior to metagenomic NGS [6]. |

| Ultra-Deep Microbiome Prep Kit (Molzym) | DNA extraction that selectively depletes host DNA and enriches for microbial DNA [19]. | Extraction of bacterial DNA directly from infected tissue biopsies for improved NGS detection [19]. |

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) | Silica-membrane based purification of total DNA from complex samples [23]. | General-purpose DNA extraction; found effective for small insects and potentially adaptable for oocysts [23]. |

| Rapid PCR Barcoding Kit (Oxford Nanopore) | Rapid library preparation for nanopore sequencing [19]. | Fast preparation of DNA libraries from extracted oocyst DNA for real-time sequencing on MinION [19]. |

| Whole Genome Amplification (WGA) Kits | Amplification of very low-yield DNA to quantities sufficient for NGS [6]. | Amplifying DNA extracted from a low number of oocysts (e.g., as few as 100) from a food sample [6]. |

| TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Thermo Fisher) | Probe-based qPCR for specific, sensitive quantification of known DNA targets [20]. | Validating NGS findings or for routine, targeted quantification of a specific parasite [22] [20]. |

Lysis in Action: A Comparative Guide to Mechanical, Thermal, and Chemical Disruption Methods

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is bead beating particularly recommended for DNA extraction from robust parasite oocysts and cysts? Bead beating is a mechanical cell lysis method that is highly effective for disrupting the tough, resilient walls of protozoan oocysts and cysts (e.g., Cryptosporidium, Giardia). These walls are often impervious to chemical lysis alone. Bead beating uses rapid agitation with grinding media to physically shear and break open these robust structures, facilitating the release of DNA for downstream applications like PCR and metagenomic sequencing [4] [24] [25]. It is considered more efficient than traditional methods like repeated freeze-thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen [4].

Q2: My DNA yield from Cryptosporidium oocysts is low. What steps can I optimize in my bead beating protocol? Low DNA yield can be addressed by optimizing several key parameters:

- Lysis Conditions: Increasing the lysis temperature to 95–100°C for 5-10 minutes during the initial buffer incubation step can significantly improve oocyst wall disruption and DNA recovery [24].

- Bead Type and Fill: Ensure you are using the appropriate bead type (e.g., silica, zirconium) and that the bead-to-sample volume ratio is correct. The tube should be about one-sixth full of beads and one-third full of cell suspension for efficient homogenization [26].

- Homogenization Time: For resilient samples like yeast and parasites, homogenization may require several minutes. One effective protocol involves multiple cycles (e.g., six cycles) of bead beating for 20 seconds, each followed by a 1-minute incubation on ice to prevent heat degradation [27].

- Inhibition: For fecal samples, extend the incubation time with InhibitEX tablets or similar inhibitors to 5 minutes to better remove PCR inhibitors [24].

Q3: How can I prevent the degradation of DNA during the bead beating process? Heat generated during bead beating can degrade DNA. To mitigate this:

- Use Cooling Intervals: Perform bead beating in short bursts (e.g., 20-30 seconds) followed by incubation of the tubes on ice or in an ice bath for one minute between cycles. This allows heat to dissipate [27] [28].

- Pulsing Feature: If your instrument has one, use a pulsing feature that incorporates rest periods between agitation cycles [29].

- Cooled Systems: For high-throughput work, use a homogenizer system that can be connected to a chiller to maintain a constant low temperature (e.g., 4–13°C) during processing [28].

Q4: My downstream PCR is inhibited despite successful bead beating. What could be the cause? PCR inhibition after successful lysis is often due to co-extraction of inhibitors from the sample matrix (e.g., feces, food).

- Purification: Incorporate additional purification steps, such as using InhibitEX tablets or silica membrane-based columns designed to adsorb and remove inhibitors like heme, bilirubins, and bile salts [24].

- Wash Steps: Ensure the commercial DNA extraction kit you are using includes rigorous wash steps with ethanol or other solvents to purify the nucleic acids [24].

- Pre-cooled Ethanol: Using pre-cooled ethanol for precipitation can improve the purity and yield of the DNA extract [24].

Troubleshooting Guide

The following table outlines common problems, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low DNA yield | Inefficient oocyst/cyst wall disruption [24]. | Optimize lysis temperature and time; Use harder/sharper beads (e.g., zirconium); Increase bead beating duration/speed [26] [24]. |

| Incorrect bead-to-sample ratio [26]. | Adjust bead volume to ~1/6 of tube volume and sample to ~1/3 of tube volume [26]. | |

| DNA shearing/fragmentation | Bead beating is too harsh or prolonged [25]. | Reduce homogenization time; Use lower speed settings; Incorporate more cooling intervals [27] [28]. |

| PCR inhibition | Incomplete removal of sample inhibitors [24]. | Use inhibitor-removal tablets; Increase incubation time with inhibitors; Add extra wash steps; Use a small elution volume (50-100 µl) to concentrate DNA [24]. |

| Inconsistent results between samples | Sample-to-sample variability in homogenization [25]. | Standardize sample mass and buffer volume; Use a high-throughput homogenizer for better reproducibility instead of a vortexer [28] [26]. |

| Inability to disrupt specific oocysts | Bead type is not matched to sample resiliency [26]. | For very resilient pathogens, use a combination of sharp, abrasive media (e.g., garnet, satellites) with larger grinding balls [26]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details essential materials and their functions for effective bead beating of robust parasite oocysts.

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Zirconium/Silica Beads | Dense, durable grinding media ideal for disrupting tough oocyst walls. Zirconium beads are particularly effective for resilient samples [26] [25]. |

| Polycarbonate Tubes | Extremely durable and impact-resistant tubes that withstand the force of bead beating without cracking, especially at cryogenic temperatures. (Note: incompatible with some organic solvents) [26]. |

| InhibitEX Tablets / Similar | Added during DNA extraction to adsorb and remove common PCR inhibitors found in complex samples like feces [24]. |

| Lysis Buffer (with Tween/SDS) | A detergent-based buffer that, when combined with mechanical disruption, solubilizes lipid membranes and facilitates the release of DNA [4]. |

| Protease Inhibitors | Added to lysis buffer to preserve native protein states and prevent degradation during extraction, crucial for protein or post-translational modification studies [27]. |

| HT Mini or GenoGrinder Homogenizers | Oscillating bead beaters that provide a high-speed, multidirectional motion for rapid and efficient cell disruption. Suitable for processing multiple samples simultaneously [29] [28]. |

Experimental Workflow and Parameter Selection

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for establishing an effective bead beating protocol for robust parasite oocysts.

Diagram 1: Bead beating protocol setup workflow.

The table below consolidates key quantitative data from published studies to inform experimental design.

| Parameter | Optimized Condition / Result | Application / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Lysis Time | Rapid lysis within 3 minutes [4]. | Metagenomic detection of C. parvum on lettuce using OmniLyse device [4]. |

| Lysis Temperature | Boiling (95-100°C) for 10 minutes [24]. | Increased sensitivity of PCR for Cryptosporidium in fecal samples [24]. |

| Bead Beating Cycles | 6 cycles of 20 sec beating / 1 min on ice [27]. | Protein extraction from resilient budding yeast cells [27]. |

| Detection Limit | 100 oocysts of C. parvum in 25g lettuce [4]; ≈2 oocysts/cysts per PCR reaction [24]. | Metagenomic NGS assay [4]; Diagnostic PCR from spiked feces [24]. |

| Sensitivity (Post-Optimization) | 100% sensitivity for Cryptosporidium detection vs. 60% with standard protocol [24]. | PCR on fecal samples using amended QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit protocol [24]. |

| Homogenizer Speed | 2400 to 4200 rpm (Oscillating) [29]; 30 Hz (Mixer Mill) [28]. | General bead beating; Cell disruption of yeast and bacteria [29] [28]. |

In research on robust parasite oocysts, such as those of Cryptosporidium and Eimeria, effective DNA extraction is a critical first step for downstream genetic analyses. The tough oocyst wall presents a significant challenge to conventional lysis methods. Thermal lysis, which utilizes boiling and heat treatment, offers a straightforward, chemical-free alternative for liberating DNA from these resilient structures. This guide addresses common questions and troubleshooting issues researchers may encounter when implementing this technique.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does thermal lysis compare to other mechanical and chemical methods for disrupting robust oocysts?

Thermal lysis provides a balanced alternative to other common methods. The table below summarizes key techniques.

| Lysis Method | Mechanism of Action | Relative Efficiency | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Lysis (Freeze-Thaw) [30] | Physical disruption from ice crystal formation and thermal shock. | High (Detects <5 oocysts) | Simple, cost-effective, minimizes chemical inhibitors. | Can be time-consuming with multiple cycles. |

| Nanoparticle Lysis [31] | Chemical and physical disruption of the oocyst wall. | Comparable to freeze-thaw | Offers a novel, viable alternative pathway. | Requires sourcing and optimization of nanoparticles. |

| Bead Beating | Mechanical shearing. | Variable | High-energy disruption. | Can cause DNA shearing; generates heat. |

| Enzymatic Lysis | Chemical degradation of wall components. | Variable | Highly specific. | Can be expensive; may require additional purification. |

Q2: What is the optimal protocol for thermal lysis of Cryptosporidium oocysts?

An optimized protocol for maximizing DNA yield involves repeated freeze-thaw cycles [30].

- Procedure: Suspend oocysts in a standard lysis buffer containing SDS. Subject the suspension to 15 cycles of freezing in liquid nitrogen followed by thawing at 65°C [30].

- Buffer Consideration: The inhibitory effects of SDS in the PCR can be counteracted by adding Tween 20 to the PCR reaction mixture [30].

- Rationale: This maximized method is particularly effective for older oocysts that are more refractory to disruption and consistently detects fewer than five oocysts [30].

Q3: My DNA yield after thermal lysis is low. What could be the problem?

Low yield can stem from several factors related to the protocol or sample condition. Please consult the troubleshooting guide below.

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low DNA Yield | Insufficient oocyst disruption | Increase the number of freeze-thaw cycles (e.g., up to 15 cycles) [30]. Ensure the use of liquid nitrogen for rapid freezing. |

| Lysis buffer incompatibility | Ensure the lysis buffer contains a detergent like SDS (0.5-1%) to facilitate breakdown of lipid membranes [32]. | |

| PCR Inhibition | Carry-over of lysis buffer components | Add Tween 20 to the PCR reaction to abrogate the inhibitory effects of SDS [30]. Perform a standard ethanol or isopropanol precipitation to purify DNA post-lysis [33]. |

| Inconsistent Results | Variable age of oocyst isolates | Older oocysts are more refractory. Implement the maximized 15-cycle protocol to ensure disruption of oocysts of unknown history or age [30]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Thermal Lysis

The following table lists key reagents required for implementing the thermal lysis protocol.

| Reagent | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Lysis Buffer | Creates the chemical environment for breaking cells and stabilizing DNA. | Typically contains Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), EDTA, and NaCl [32]. |

| Detergent | Solubilizes lipid membranes in the oocyst wall and cellular membranes. | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) [30] or Triton X-100 [34]. |

| Proteinase K | Enzyme that degrades proteins and helps inactivate nucleases. | Often added separately to the lysis buffer to improve efficiency [32]. |

| Neutralizing Agent | Counteracts the effects of inhibitory substances in downstream PCR. | Tween 20 can be added to the PCR master mix to abrogate SDS inhibition [30]. |

Experimental Workflow: From Oocyst to DNA

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for extracting DNA from parasite oocysts using a thermal lysis method, integrating steps from validated protocols [30] [35].

Diagram 1: Generalized workflow for thermal lysis DNA extraction.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My lysis buffer is not effectively breaking down Cryptosporidium oocysts, resulting in low DNA yield. What could be wrong? This is a common challenge with robust parasite oocysts. The issue likely stems from insufficient lysis strength. The oocyst wall is highly resilient and often requires specialized mechanical or thermal lysis in addition to chemical lysis. Ensure your buffer contains a denaturing ionic detergent like SDS and consider incorporating a rigorous mechanical lysis step, such as bead beating or multiple freeze-thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen [4] [30].

Q2: I am getting a high DNA yield, but my downstream PCR is inhibited. How can I modify my lysis buffer? PCR inhibition is frequently caused by residual detergents or contaminants from the lysis buffer. The ionic detergent SDS is a known PCR inhibitor. This can be mitigated by adding a non-ionic detergent like Tween 20 to the PCR reaction to abrogate the inhibitory effects [30]. Furthermore, always ensure proper DNA purification after lysis, such as acetate precipitation, to remove lysis buffer components and other inhibitors [4].

Q3: Why is it critical to check the pH of my lysis buffer periodically, and what is the optimal range? The pH is critical for maintaining DNA stability and enzymatic activity. DNA can depurinate in acidic conditions, while RNA is prone to hydrolysis in alkaline environments. An optimum pH (7.8 to 8.0) is crucial for effective DNA isolation as it provides a constant environment for biological activities and helps stabilize the DNA [32] [36]. Always check the pH before use and do not use a buffer outside this range.

Q4: My proteinase K does not seem to be working effectively. What should I check? First, ensure the enzyme is fresh and has been stored correctly at 4°C. Second, confirm that your lysis buffer does not contain conditions that inactivate proteinase K, such as high concentrations of SDS before the digestion step. Proteinase K should be added separately to the lysis buffer and requires a prolonged incubation (e.g., overnight at 56°C) for effective degradation of proteins from tough structures like oocysts [32] [37].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low DNA yield from oocysts | Inefficient oocyst/cyst wall disruption | Implement mechanical lysis (bead beating, OmniLyse) [4] or 15 cycles of freeze-thaw (liquid nitrogen/65°C) [30]. Use a denaturing detergent like SDS [32]. |

| PCR inhibition | Residual lysis buffer contaminants (e.g., SDS) | Add Tween 20 to the PCR reaction mix [30]. Clean up DNA post-lysis via acetate precipitation or spin columns [4] [38]. |

| Incomplete lysis | Suboptimal detergent type or concentration | Use 0.5-1% SDS for robust oocysts [32] [30]. For milder lysis, use 1% Triton X-100 or NP-40 [39]. |

| DNA degradation | Nuclease activity or improper pH | Ensure pH is 7.8-8.0 [32]. Include EDTA (2-10 mM) in the lysis buffer to chelate Mg²⁺ and inhibit DNases [32] [36]. |

| Poor downstream NGS results | Insufficient DNA quantity/quality for sequencing | Incorporate whole genome amplification post-extraction [4]. Use mechanical lysis (bead beating) to increase DNA yield and diversity from gram-positive bacteria [40]. |

Optimized Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Maximized Freeze-Thaw Lysis for Cryptosporidium Oocysts

This protocol is optimized for liberating DNA from Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts in water samples and is adapted from a published method [30].

1. Reagents and Lysis Buffer:

- Lysis Buffer Composition:

- 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)

- 25 mM EDTA

- 1% (w/v) SDS

- (Optional) 100 µg/mL Proteinase K (add fresh)

2. Procedure:

- Concentrate oocysts from the water sample by centrifugation at 15,000 x g for 60 minutes. Discard the supernatant.

- Resuspend the oocyst pellet thoroughly in the prepared lysis buffer.

- Perform 15 cycles of freezing in liquid nitrogen and thawing at 65°C.

- If Proteinase K was not added initially, add it now and incubate the lysate at 56°C for a minimum of 1 hour (or overnight for better yields).

- To mitigate PCR inhibition from SDS, add Tween 20 to the final PCR reaction mixture.

- Purify the DNA using phenol-chloroform extraction or a commercial DNA clean-up kit before downstream analysis.

Protocol 2: Rapid Mechanical Lysis for Metagenomic Detection on Leafy Greens

This rapid method was developed for efficient lysis of protozoan parasites on lettuce for metagenomic next-generation sequencing [4].

1. Reagents:

- Wash Buffer: Buffered peptone water supplemented with 0.1% Tween.

- Lysis Device: OmniLyse or similar bead-beating homogenizer.

2. Procedure:

- Wash the surface of 25 g lettuce with 40 ml of wash buffer using a stomacher at 115 rpm for 1 minute.

- Filter the wash fluid through a 35 µm filter to remove plant debris.

- Pellet oocysts/cysts by centrifuging the filtrate at 15,000 x g for 60 minutes at 4°C.

- Subject the pellet to rapid mechanical lysis using the OmniLyse device for 3 minutes.

- Extract DNA from the lysate using acetate precipitation.

- Amplify the extracted DNA using whole genome amplification to generate sufficient material (e.g., 0.16–8.25 µg) for NGS library preparation.

Workflow Visualization

Oocyst DNA Extraction Pathways

Lysis Optimization Decision Tree

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function in Lysis | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Ionic, denaturing detergent that solubilizes lipid membranes and proteins. Effective for tough oocyst walls [32] [30]. | Use at 0.5-1% (w/v). A known PCR inhibitor; requires cleanup or addition of Tween 20 in PCR [30]. |

| CTAB (Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) | Cationic detergent effective for plant and bacterial cells, useful for polysaccharide-rich matrices [32]. | Common in plant DNA extraction; use in combination with β-mercaptoethanol to inhibit polyphenol oxidation [32]. |

| Tris-HCl | Buffering agent to maintain constant pH environment (typically pH 8.0) for enzymatic reactions and DNA stability [32] [39]. | Standard concentration is 10-100 mM. Avoid in cross-linking reactions that target primary amines [36]. |

| EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) | Chelating agent that binds Mg²⁺ and other divalent cations, inhibiting DNase activity [32] [36]. | Use at 2-25 mM. Essential for protecting DNA during extraction and storage [32]. |

| Proteinase K | Broad-spectrum serine protease that degrades proteins and removes contaminants from DNA [32] [37]. | Add fresh to lysis buffer. Requires extended incubation (overnight at 56°C) for robust oocysts [37]. |

| β-Mercaptoethanol | Reducing agent that disrupts disulfide bonds in proteins, aiding in lysis. Prevents oxidation of polyphenols [32]. | Often used in plant DNA extraction buffers (e.g., with CTAB). Handle in a fume hood due to toxicity [32]. |

| NaCl | Ionic salt that stabilizes DNA, maintains ionic strength, and helps in precipitation of proteins and carbohydrates [32] [39]. | Concentration varies widely (100-500 mM). Helps in the precipitation of CTAB-nucleic acid complexes [32]. |

FAQs: Addressing Common Challenges in DNA Extraction from Robust Parasite Oocysts

1. What is the most critical step in extracting DNA from robust parasite oocysts and why? The most critical step is the efficient rupture of the robust oocyst wall. Traditional methods like quick freeze-thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen or heating at 100°C are often time-consuming, cannot be easily adapted for field testing, and can compromise double-stranded DNA integrity [6]. Inefficient lysis directly results in low DNA yield, as the DNA cannot be accessed for downstream applications.

2. How can I improve the lysis efficiency of tough oocyst walls for DNA extraction? An optimized method involves a dual chemical pre-treatment. Research shows that incubating oocysts in sodium hypochlorite for 1.5 hours at 4°C, followed by treatment with a saturated salt solution for 1 hour at 55°C, successfully breaks the walls of various coccidian species, including Eimeria tenella and Cryptosporidium cuniculus [41]. This combination is more sensitive and efficient than single-method approaches.

3. My DNA yields from stool samples are low, even though I'm following the kit protocol. What could be the cause? Low yield from stool can stem from several factors related to sample handling and composition:

- Incomplete Cell Lysis: Microbial communities in stool, particularly Firmicutes, have tough cell walls. Bead-beating is more effective than enzymatic or vortex-based lysis alone [42].

- Sample Storage: Stool samples stored at room temperature for over 48 hours can show significant deterioration of microbial DNA. For long-term storage, flash-freezing at -80°C is recommended [43].

- Inhibitory Substances: Stool contains bile salts, humic acids, and complex carbohydrates that can inhibit downstream enzymatic reactions. Using a kit, like the MoBio PowerMicrobiome Kit, that effectively removes these inhibitors is crucial for high yield and purity [42].

4. How can I preserve stool samples for DNA analysis when immediate freezing at -80°C is not possible? The use of stabilizing reagents is essential for room-temperature storage. A Dimethyl Sulphoxide, disodium EDTA, and saturated NaCl (DESS) solution is highly effective. Studies show that stool samples preserved in DESS and stored at room temperature maintain microbial community structure well, showing high correlation (R² > 0.96) with snap-frozen samples for species-level analysis [43]. This method is compatible with novel collection kits, including dissolvable wipes, which enhance user compliance [43].

5. I am getting salt contamination in my final DNA eluate. How can I prevent this? Salt contamination, often indicated by low A260/A230 ratios, is frequently caused by the carryover of guanidine salts from the binding buffer. To prevent this:

- Avoid touching the upper column area with the pipette tip when transferring the lysate.

- Take care to close the caps gently to avoid splashing the mixture.

- Do not transfer any foam present in the lysate to the column.

- Perform the wash steps as indicated, and consider inverting the columns a few times with the wash buffer [44].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Problems and Solutions

The following table outlines specific issues, their probable causes, and evidence-based solutions for DNA extraction from challenging samples.

| Problem | Primary Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low DNA Yield | Inefficient oocyst/cyst lysis [6]. | Implement a dual pre-treatment: sodium hypochlorite (1.5h, 4°C) followed by saturated salt solution (1h, 55°C) [41]. |

| Incomplete mechanical lysis of microbial cells [42]. | Incorporate a rigorous bead-beating step using 0.1 mm zirconia beads for more effective cell wall disruption [42]. | |

| Sample degradation due to improper storage [43]. | Flash-freeze samples in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C. For field work, use DESS stabilization solution for room-temperature preservation [43]. | |

| DNA Degradation | High nuclease activity in samples (e.g., pancreas, intestine, liver) [44]. | Keep samples frozen and on ice during preparation. Ensure lysis buffer is added immediately upon thawing to inactivate nucleases. |

| Stool samples stored at room temperature for >48 hours [43]. | Process samples immediately or use a DNA/RNA stabilizer (e.g., RNA Later, DESS) immediately upon collection [43]. | |

| Protein Contamination | Incomplete digestion of protein complexes [44]. | Extend the Proteinase K digestion time by 30 minutes to 3 hours after the sample appears dissolved. |

| Clogged spin column membrane with tissue fibers [44]. | For fibrous samples, centrifuge the lysate at maximum speed for 3 minutes before loading it onto the spin column to remove indigestible fibers. | |

| Co-purification of Inhibitors | Presence of humic acids, bile salts, or complex carbohydrates in stool [42]. | Use a commercial kit proven to remove these substances effectively (e.g., MoBio PowerMicrobiome Kit) as it yielded RNA with superior 260/230 ratios [42]. |

Enhanced Step-by-Step Protocol for Robust Oocysts in Environmental Samples

This protocol is adapted from published research on detecting Cryptosporidium on lettuce and identifying coccidian species [6] [41]. It outlines modifications to standard commercial kit procedures to enhance oocyst lysis and DNA recovery.

The following diagram illustrates the enhanced workflow for processing environmental samples for parasite DNA detection, highlighting key modifications to standard protocols.

Materials and Reagents

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| OmniLyse Device [6] | Provides rapid, mechanical disruption of oocysts/cysts (within 3 minutes). |

| Sodium Hypochlorite Solution | Chemical pre-treatment to weaken the robust oocyst wall [41]. |

| Saturated Salt Solution | Chemical pre-treatment used in combination with hypochlorite for effective wall rupture [41]. |

| DESS Solution (Dimethyl sulfoxide, EDTA, NaCl) | A stabilizer for room-temperature preservation of sample biomolecules [43]. |

| Whole Genome Amplification Kit | Used to amplify extracted DNA to quantities sufficient for NGS when starting material is low [6]. |

| Bead-beater with 0.1 mm Zirconia Beads | Essential for effective lysis of tough microbial cells, such as Gram-positive bacteria [42]. |

Detailed Protocol Steps

Step 1: Sample Collection and Processing (for leafy greens)

- Place 25g of lettuce leaves in a sterile container.

- If simulating contamination, spike with a known number of oocysts (e.g., 100-100,000 C. parvum oocysts) and let air dry [6].

- Transfer the leaf to a stomacher bag with 40 ml of buffered peptone water supplemented with 0.1% Tween.

- Homogenize in a stomacher at 115 rpm for 1 minute to dissociate oocysts from the leaf surface.

- Pass the fluid through a custom 35 μm filter under vacuum to remove plant debris.

- Pellet the oocysts by centrifuging the filtrate at 15,000x g for 60 minutes at 4°C. Discard the supernatant [6].

Step 2: Enhanced Oocyst Lysis (Critical Modification)

- Resuspend the pellet from Step 1.

- Pre-treatment: Incubate the oocyst suspension in sodium hypochlorite for 1.5 hours at 4°C. Then, treat with a saturated salt solution for 1 hour at 55°C [41]. This dual treatment significantly improves lysis efficiency over standard kit lysis buffers alone.

- Mechanical Lysis: Transfer the pre-treated suspension to a tube containing lysis buffer and a bead-beating matrix (e.g., 0.1 mm zirconia beads). Lyse using a high-speed homogenizer like the OmniLyse for 3 minutes [6] or a standard bead-beater. This step ensures the complete disruption of pre-weakened oocysts and other microbial cells.

Step 3: DNA Extraction and Purification

- Follow the manufacturer's instructions of your chosen commercial gDNA extraction kit from this point forward.

- Transfer the supernatant from the mechanical lysis step to a silica spin column. The pre-lysis steps ensure more DNA is available for binding.

- Complete the recommended wash steps thoroughly to remove contaminants.

- Elute DNA in the provided buffer or nuclease-free water.

Step 4: DNA Amplification and Analysis (if required)

- For samples with very low DNA yield (e.g., from few oocysts), subject the extracted DNA to Whole Genome Amplification (WGA) to generate sufficient material for sequencing [6].

- The resulting DNA is now suitable for downstream applications like metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) or specific PCR assays for parasite identification [6] [41].

Troubleshooting Guide and FAQs for DNA Extraction from Robust Parasite Oocysts

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My current DNA extraction method for Cryptosporidium oocysts yields DNA that is consistently contaminated with PCR inhibitors. What is the most effective way to relieve this inhibition?

A1: PCR inhibition is a common challenge when working with complex samples like water concentrates or feces. The most effective relief can be achieved by incorporating specific PCR facilitators directly into your amplification reaction [45].

- Recommended Solution: Add 400 ng/µL of nonacetylated Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) or 25 ng/µL of T4 gene 32 protein to your PCR mixture. Studies have demonstrated that this addition can significantly relieve inhibition, allowing for successful amplification where it previously failed [45].

- Alternative Approach: Consider using a DNA extraction kit designed for inhibitory samples, such as the FastDNA SPIN kit for soil. When used in conjunction with BSA in the PCR mix, this kit has been shown to perform as well as methods requiring prior oocyst purification via immunomagnetic separation [45].

Q2: I am working with C. hominis and finding the oocyst wall resistant to standard chemical permeabilization methods. How can I overcome this?

A2: C. hominis oocysts are notably resistant to chemical permeabilization agents like bleach, which are more effective on C. parvum [46]. A novel thermal permeabilization technique has been developed specifically for this purpose.

- Protocol: Incubate the oocysts with your cryoprotective agent (e.g., 50% DMSO) at 37°C for 2-5 minutes [46].

- Rationale: The elevated temperature is thought to melt lipid components in the oocyst wall, enabling the uptake of cryoprotective agents. This method has been shown to effectively eliminate the variable permeabilization response seen with other methods and is reproducible across different oocyst batches [46].

Q3: I need to extract DNA directly from feces for diagnostic PCR of protozoan parasites, but my sensitivity for Cryptosporidium is low. How can I optimize my kit-based protocol?

A3: Direct extraction from feces is challenging due to the robust oocyst wall and co-extracted PCR inhibitors. Modifying the manufacturer's protocol for the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit can dramatically improve sensitivity [24].

- Key Optimizations:

- Lysis Temperature and Duration: Increase the lysis temperature to 95-100°C (boiling) and maintain it for 10 minutes to more effectively disrupt the tough oocyst wall [24].

- Inhibitor Removal: Ensure the incubation time with the InhibitEX tablet is extended to 5 minutes to adequately adsorb inhibitors [24].

- Precipitation and Elution: Use pre-cooled ethanol for the precipitation step and elute the DNA in a small volume (50-100 µL) to increase the final DNA concentration [24]. This optimized protocol has been shown to increase detection sensitivity from 60% to 100% for Cryptosporidium [24].

Q4: What is the principle behind using rapid lysis devices, like the OmniLyse, in metagenomic studies of foodborne parasites?

A4: Rapid lysis devices utilize physical force to achieve near-instantaneous mechanical disruption of oocysts and cysts [4].

- Function: These devices efficiently break open the resilient walls of parasites on surfaces like leafy greens within 3 minutes, releasing intracellular DNA [4].

- Advantage: This method avoids the DNA fragmentation that can occur with lengthy heating cycles and is more rapid and consistent than traditional methods like repeated freeze-thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen. It provides high-quality DNA in quantities sufficient for metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS), enabling the simultaneous detection and differentiation of multiple protozoan parasites from a single sample [4].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of DNA Extraction and Processing Methods for Protozoan Parasites

| Method | Target / Application | Key Parameter | Reported Outcome / Yield | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FastDNA SPIN Kit (Soil) | Cryptosporidium DNA from water | PCR success with BSA | Performance equal to IMS purification | [45] |

| Thermal Permeabilization | C. hominis oocysts | Viability post-thaw | ~70% viability, 100% infectivity in piglets | [46] |

| Optimized QIAamp Stool Kit | Cryptosporidium DNA from feces | Diagnostic sensitivity | Sensitivity increased from 60% to 100% | [24] |

| Rapid Lysis (OmniLyse) | Parasites on lettuce for mNGS | Limit of detection | Consistent identification of 100 oocysts in 25g lettuce | [4] |

| Alkaline Lysis (Modified) | Plant DNA (Osmanthus leaf) | DNA yield from fresh tissue | ~1000 µg/g of tissue in ~1.5 hours | [47] |

Table 2: Key Reagents for Inhibition Relief and Permeabilization

| Reagent | Function | Mechanism of Action | Typical Working Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonacetylated BSA | PCR Facilitator | Binds to inhibitors, freeing the DNA polymerase | 400 ng/µL in PCR mix [45] |

| T4 Gene 32 Protein | PCR Facilitator | Stabilizes single-stranded DNA, enhances processivity | 25 ng/µL in PCR mix [45] |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Cryoprotectant / Permeabilant | Penetrates oocysts upon thermal shock, prevents ice crystal formation | 30-50% in CPA cocktail [46] |

| Trehalose | Cryoprotectant / Osmotic Agent | Non-permeating CPA that dehydrates oocysts, aids vitrification | 0.5 - 1.0 M in CPA cocktail [46] |

| Guanidine Hydrochloride | Chaotropic Agent / Denaturant | Disrupts protein structure and hydrogen bonding; facilitates contaminant precipitation | 3 M in modified alkaline lysis [48] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Vitrification and Thermal Permeabilization of C. hominis Oocysts

This protocol enables the long-term cryopreservation of infectious C. hominis oocysts, a critical advancement for maintaining standardized research materials [46].

Oocyst Dehydration:

- Suspend the oocyst pellet in a hyperosmotic solution of 1 M Trehalose. This non-permeating agent draws out intracellular water, causing the oocysts to shrink and reducing the potential for lethal ice crystallization during cooling [46].

Thermal Permeabilization and CPA Loading:

- Transfer the oocysts to a cryoprotective agent (CPA) cocktail consisting of 0.8 M Trehalose and 50% DMSO.

- Incubate the mixture at 37°C for 2 minutes. This critical step thermally permeabilizes the oocyst wall, allowing the DMSO to penetrate the cell [46].

- Note: Monitor exposure time carefully, as 50% DMSO becomes toxic with prolonged incubation at this temperature.

Vitrification:

- Rapidly load the oocyst-CPA suspension into high-aspect-ratio specimen containers (scaled for ~100 µL volume) to ensure ultra-rapid cooling rates.

- Immediately plunge the containers into liquid nitrogen (-196°C) for storage. The rapid cooling through the glass transition temperature forms an amorphous, ice-free solid, preserving oocyst integrity [46].

Thawing and Recovery:

- To thaw, rapidly warm the vitrified samples (e.g., in a water bath at 37°C) and gradually dilute out the CPA to avoid osmotic shock.

Protocol 2: Optimized DNA Extraction from Feces for Diagnostic PCR

This amended protocol for the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit maximizes DNA recovery from robust Cryptosporidium oocysts directly in fecal samples [24].

Lysis: Add the stool sample to the kit's lysis buffer and incubate at 95-100°C (boiling) for 10 minutes. This enhanced lysis step is crucial for disrupting the tough oocyst wall [24].

Inhibition Removal: Add the supernatant to the InhibitEX tablet and incubate at room temperature for 5 minutes (an increase from the standard protocol) to ensure maximum adsorption of PCR inhibitors [24].

Binding and Washing: Follow the manufacturer's instructions for binding DNA to the silica membrane and subsequent wash steps.

Elution: Use pre-cooled ethanol during the precipitation step. Elute the purified DNA in a small volume of buffer (50-100 µL) to maximize the final DNA concentration for downstream PCR applications [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Advanced Oocyst Research

| Item | Specific Example / Model | Critical Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Lysis Device | OmniLyse | Provides rapid, efficient physical disruption of oocyst walls for metagenomic studies [4]. |

| DNA Extraction Kit (Inhibitory Samples) | FastDNA SPIN Kit for Soil | Designed to co-extract and remove humic acids and other inhibitors from complex environmental samples [45]. |

| DNA Extraction Kit (Stool Samples) | QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit | Optimized for direct lysis and DNA purification from feces, with built-in inhibitor removal technology [24]. |

| High-Aspect-Ratio Specimen Container | Custom cassettes (~100µL volume) | Enables the ultra-rapid cooling rates necessary for successful vitrification of biological samples [46]. |

| PCR Facilitator | Nonacetylated Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | An essential additive to PCR reactions to neutralize co-extracted inhibitors and ensure successful amplification [45]. |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: A comprehensive workflow illustrating the two primary pathways for processing robust parasite oocysts: one focusing on DNA extraction for molecular applications and the other on vitrification for long-term storage. Critical novel techniques (thermal permeabilization, rapid lysis) are highlighted with colored parallelograms and red connecting lines.

Solving the Puzzle: Proven Strategies to Overcome Inhibition and Maximize DNA Yield

Optimizing Lysis Temperature and Duration for Maximum Efficiency

This technical support guide provides targeted solutions for researchers facing challenges with DNA extraction from robust parasite oocysts, such as Cryptosporidium and Giardia.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary sign that my lysis conditions are suboptimal? A clear sign is the inability to detect parasite DNA via PCR from samples confirmed to be positive by microscopy or immunoassay. This indicates insufficient disruption of the robust oocyst wall to release nucleic acids [24].

Why are standard lysis protocols often ineffective for parasite oocysts? Oocysts and cysts possess very robust cell walls that are designed to protect the genetic material from harsh environmental conditions. Standard lysis protocols developed for mammalian cells or bacteria frequently fail to breach these structures effectively [24].

How does lysis temperature impact DNA yield from oocysts? Increasing the lysis temperature to the boiling point (≈100°C) for 10 minutes has been shown to significantly improve DNA recovery. One study demonstrated that this optimization increased the sensitivity of Cryptosporidium detection from 60% to 100% [24].

Can lysis duration be too long? Yes, excessive lysis duration, especially at high temperatures, can lead to increased co-extraction of PCR inhibitors from the sample matrix and potential shearing or degradation of DNA, which is particularly detrimental for downstream applications like qPCR [49].

What is the role of freeze-thaw cycles in oocyst lysis? Multiple freeze-thaw cycles create physical stress that helps fracture the tough oocyst wall. A maximized method for Cryptosporidium involves 15 cycles of freezing in liquid nitrogen and thawing at 65°C in a lysis buffer containing SDS [30].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Consistently Low DNA Yield from Fecal Samples

Investigation and Solutions:

- Verify Lysis Efficiency: Rule out PCR inhibition by diluting the DNA extract or spiking it with a known positive control. If amplification improves, inhibitors are present. If not, lysis is likely inefficient [24].

- Optimize Thermal Lysis: Implement a high-temperature lysis step. Boil samples in lysis buffer for 10 minutes to enhance oocyst wall disruption [24].

- Incorporate Mechanical Disruption: For samples processed with commercial kits, introduce a mechanical lysis step using a benchtop homogenizer (e.g., 2 cycles of 30 seconds at 6000 rpm) prior to the kit's protocol [11].

Problem: PCR Inhibition or Poor DNA Purity

Investigation and Solutions:

- Assess Inhibitor Removal: Ensure steps to remove PCR inhibitors (e.g., the incubation step with an InhibitEX tablet) are optimized. Extending this incubation time to 5 minutes can improve results [24].

- Optimize Post-Lysis Cleanup: Use a pre-cooled ethanol for precipitation and elute the final DNA in a small volume (50-100 µl) to increase DNA concentration and purity [24].

- Check Buffer Additives: For in-house CTAB protocols, ensure the use of additives like polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) and β-mercaptoethanol, which help bind polyphenols and inhibit oxidation, leading to purer DNA [32].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Optimized Protocol for Cryptosporidium Oocysts in Water

The following methodology is designed for maximum DNA recovery from a small number of oocysts in water samples [30].

Key Modifications for Fecal Samples: For DNA extraction directly from feces using the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit, the following amendments to the manufacturer's protocol are recommended [24]:

- Lysis Temperature: Raise the lysis temperature to the boiling point.

- Lysis Duration: Hold at the elevated temperature for 10 minutes.

- Inhibitor Removal: Increase the incubation time with the InhibitEX tablet to 5 minutes.

Quantitative Data on Lysis Optimization

Table 1: Impact of Lysis Optimization on Detection Sensitivity

| Sample Type | Lysis Condition | Detection Sensitivity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cryptosporidium-positive feces | Standard Kit Protocol | 60% (9/15 samples) | [24] |

| Cryptosporidium-positive feces | Amended Protocol (Boiling for 10 min) | 100% (15/15 samples) | [24] |

| Cryptosporidium in water | Single Freeze-Thaw | Not Specified | [30] |

| Cryptosporidium in water | 15x Freeze-Thaw (Liquid N₂/65°C) | <5 oocysts detectable | [30] |

Table 2: Lysis Buffer Components and Their Functions

| Reagent | Function | Example Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Ionic detergent that disrupts lipid membranes and solubilizes proteins. | 0.5% - 1% (w/v) [30] [32] |

| CTAB (Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) | Effective for breaking down plant and bacterial cell walls; useful for tough contaminants in fecal samples. | 2% (w/v) [32] |

| Tris-HCl | Buffering agent to maintain stable pH (typically 8.0) for biomolecule stability. | 10-100 mM [32] |

| EDTA | Chelating agent that inactivates DNases by sequestering Mg²⁺ ions. | 2-25 mM [32] |

| NaCl | Stabilizes DNA and helps to remove contaminants through precipitation. | 100-500 mM [32] |

| Proteinase K | Enzyme that degrades proteins and helps to disrupt the oocyst wall. | Added separately [32] |

| β-mercaptoethanol | Reducing agent that disrupts disulfide bonds in proteins, aiding in lysis. | 10 mM [32] |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Binds to polyphenols, preventing their co-extraction and inhibition of PCR. | 4% (w/v) [32] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Oocyst Lysis

| Item | Function | Specific Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen) | Commercial kit for DNA isolation from feces, optimized with amended protocols. | Ideal for diagnostic PCR directly from complex fecal samples [24]. |