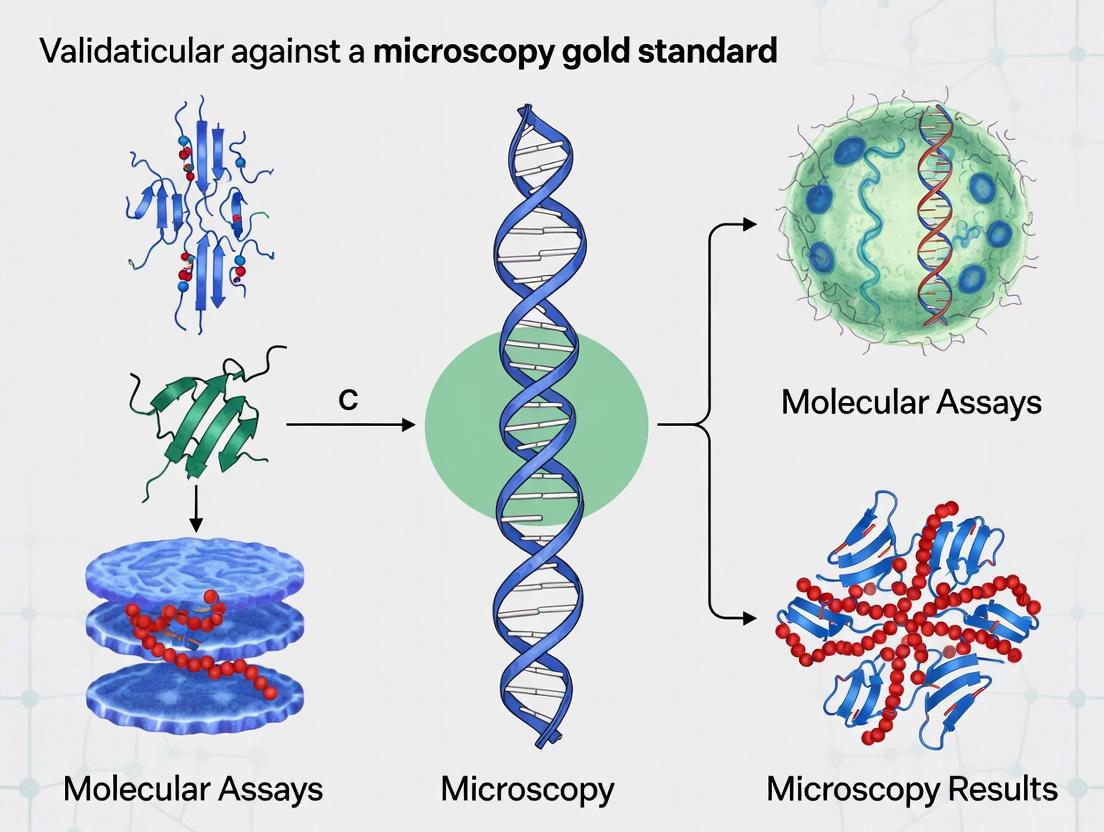

Beyond the Microscope: A Comprehensive Framework for Validating Molecular Assays Against Microscopy Gold Standards

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a structured guide for the analytical validation of molecular diagnostic tests against traditional microscopy.

Beyond the Microscope: A Comprehensive Framework for Validating Molecular Assays Against Microscopy Gold Standards

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a structured guide for the analytical validation of molecular diagnostic tests against traditional microscopy. It explores the foundational principles of validation, detailing specific methodological applications across diseases like malaria and leprosy. The content offers practical troubleshooting strategies for common assay challenges and establishes a rigorous framework for conducting comparative studies to demonstrate non-inferiority, equivalence, or superiority. By synthesizing current standards and real-world case studies, this resource aims to ensure that novel molecular methods meet the required diagnostic performance for clinical and research implementation.

The Why and What: Core Principles of Validation and the Established Gold Standard

Validation is the foundational process of establishing documented, scientific evidence that a diagnostic method reliably performs as intended for its specific purpose. In the context of medical diagnostics, this process ensures that assays and tests provide accurate, reproducible results that can be trusted to inform clinical decision-making. For diagnostic methods targeting infectious diseases like malaria and SARS-CoV-2, validation typically involves comparing new molecular assays against established reference methods, often referred to as "gold standards" [1]. For many infectious diseases, particularly in resource-limited settings, microscopy remains the benchmark against which newer technologies are measured [2]. However, the validation process must account for the limitations of even these established methods, as the choice of an inappropriate gold standard can significantly distort diagnostic outcomes [3].

This guide objectively compares the performance of various diagnostic platforms, focusing specifically on molecular assays validated against microscopy gold standards, to provide researchers and drug development professionals with evidence-based insights for selecting appropriate diagnostic tools.

Gold Standard Comparison: Microscopy Versus Molecular Methods

Performance Characteristics Across Diagnostic Platforms

Table 1: Comparative performance of diagnostic methods for infectious diseases

| Diagnostic Method | Target Pathogen | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Agreement with Gold Standard | Limit of Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopy (Gold Standard) | Plasmodium falciparum | 100 (Reference) | 100 (Reference) | N/A | 11-50 parasites/μL [2] |

| 18S qPCR | Plasmodium falciparum | 100 | 100 | Excellent (ICC: 0.97) [2] | 22 parasites/mL [2] |

| EasyNAT Malaria Assay | Plasmodium spp. | 100 | 97.5 | 96.3% congruency with LAMP [4] | Correlates with parasitemia [4] |

| Alethia Malaria LAMP Assay | Plasmodium spp. | 97.8 | 98.3 | 96.3% congruency with EasyNAT [4] | Not specified |

| Aptima SARS-CoV-2 Assay | SARS-CoV-2 | 100 | 100 | 97.6% with LDT-Fusion [5] | Not specified |

| LDT-Fusion SARS-CoV-2 Assay | SARS-CoV-2 | 100 | 100 | 97.6% with Aptima [5] | Not specified |

| R-GENE SARS-CoV-2 Assay | SARS-CoV-2 | 98.2 | 100 | 98.8% with Aptima & LDT-Fusion [5] | Not specified |

| IntelliPlex Lung Cancer Panel DNA | Lung cancer biomarkers | 97.73 | 100 | 98% with NGS [6] | 5% VAF [6] |

| IntelliPlex Lung Cancer Panel RNA | Lung cancer biomarkers | 100 | 100 | 100% with NGS [6] | Not specified |

Workflow Efficiency and Operational Characteristics

Table 2: Operational characteristics of diagnostic platforms

| Diagnostic Method/Platform | Hands-on Time (minutes) | Total Turnaround Time | Throughput | Automation Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopy | Significant (varies) | 30-60 minutes (expert dependent) | Low | Manual |

| Aptima SARS-CoV-2 (Panther) | 24 | Moderate | High | Fully automated, random-access [5] |

| LDT-Fusion SARS-CoV-2 | 25 | Moderate | High | Fully automated, random-access [5] |

| R-GENE SARS-CoV-2 | 71 | Long | Moderate | Manual processing [5] |

| NeuMoDx SARS-CoV-2 | Low (not specified) | Short | Highest | Fully automated [7] |

| DiaSorin Simplexa SARS-CoV-2 | Low (not specified) | Moderate | Moderate | Simplified workflow [7] |

| IntelliPlex Lung Cancer Panel | Not specified | Faster than NGS | High for targeted genes | Multiplexed detection [6] |

| 18S qPCR | Moderate (DNA extraction required) | Several hours | Moderate | Semi-automated [2] |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Protocol for Microscopy and Molecular Method Comparison

The following workflow represents a standardized approach for validating molecular diagnostic methods against microscopy gold standards:

Sample Collection and Preparation: For malaria studies, blood samples are collected in EDTA tubes, with thick and thin blood films prepared immediately. Thick films are used for parasite detection, while thin films allow for species identification [2]. For SARS-CoV-2 detection, nasopharyngeal swabs are collected in viral transport medium [5]. Nucleic acid extraction is performed using commercial kits such as the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit for malaria [2] or system-specific protocols for automated platforms [5].

Microscopy Protocol: Experienced microscopists examine blood films following standardized WHO protocols. In malaria diagnostics, technicians count asexual parasites against 200 white blood cells (WBCs) in thick films. If the parasite count is less than 10 after examining 200 WBCs, counting continues up to 500 WBCs. Thin films are utilized when parasite density exceeds 250 parasites per 50 WBCs [2]. Parasitemia is calculated using the formula: (number of parasites counted / number of WBCs counted) × WBC count per μL [2].

Molecular Analysis Protocol: For 18S qPCR malaria detection, DNA is extracted from 200μL of packed RBCs. The Plasmodium-specific qPCR uses primers and probes targeting the 18S rRNA gene with a detection limit of approximately 22 parasites/mL. Samples are run in triplicate, with cycle threshold values greater than 50 considered non-detectable [2]. For SARS-CoV-2 detection, the Aptima assay uses transcription-mediated amplification (TMA) targeting two sequences on the ORF1ab gene, while the LDT-Fusion assay uses real-time RT-PCR targeting the RdRP gene [5].

Statistical Analysis: Concordance between methods is assessed using multiple statistical approaches. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) measures consistency between quantitative measurements [2]. Passing-Bablok regression detects systematic and proportional biases [2]. Positive percent agreement (PPA) and negative percent agreement (NPA) are calculated against the consensus result, which is typically defined as agreement between at least two of three methods [5].

Validation Study Designs for Digital Microscopy

The transition from light microscopy to digital microscopy requires rigorous validation to ensure diagnostic accuracy is maintained. Several study designs have been employed:

Diagnostic Concordance Studies: These studies measure the agreement between diagnoses made using light microscopy versus digital whole-slide images. Multiple pathologists review cases using both modalities in randomized order, with washout periods between viewings to prevent recall bias [1].

Non-inferiority Designs: These studies test whether digital microscopy is not substantially worse than light microscopy by a predetermined margin. This approach is particularly relevant when implementing new technology where maintaining diagnostic accuracy is crucial [1].

Special Application Validations: Separate validation is recommended for different pathology applications, including routine histology with H&E staining, immunohistochemistry, and cytology specimens. Each application may require different scanning parameters and validation approaches [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key reagents and materials for diagnostic validation studies

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Viral Transport Medium (VTM) | SARS-CoV-2 detection | Preserves viral integrity during transport and storage [5] |

| QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit | Malaria parasite DNA extraction | Extracts and purifies parasite DNA from whole blood [2] |

| EasyMAG Extraction System | Nucleic acid extraction | Automated extraction for SARS-CoV-2 RNA [5] |

| Primer/Probe Sets (18S rRNA) | Malaria qPCR | Amplifies and detects Plasmodium-specific DNA sequences [2] |

| πCODE MicroDiscs | IntelliPlex Lung Cancer Panel | Multiplexed detection of DNA/RNA targets through unique barcodes [6] |

| Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) Tissue | Oncology biomarker detection | Preserves tissue architecture and biomolecules for analysis [6] |

| OncoSpan gDNA Reference Standard | Assay validation | Provides standardized control for limit of detection studies [6] |

| Positive and Negative Control Materials | Quality assurance | Verifies assay performance and identifies contamination [5] [2] |

Analysis of Validation Data and Interpretation

Statistical Approaches for Method Comparison

Validation studies employ multiple statistical methods to comprehensively evaluate agreement between methods. In malaria diagnostics, the high ICC value of 0.97 between microscopy and 18S qPCR indicates excellent consistency in measuring parasitemia levels [2]. The minimal mean difference of 0.04 log10 units/mL between methods demonstrated through paired t-tests provides evidence that 18S qPCR does not systematically over- or under-estimate parasitemia compared to microscopy [2].

Passing-Bablok regression is particularly valuable for detecting systematic biases that might not be apparent through simple correlation analysis. This method is robust to the distribution of measurements and can identify both constant and proportional differences between methods [2]. In the case of malaria diagnostics, the absence of significant systematic or proportional bias reinforces the suitability of 18S qPCR as a quantitative method comparable to microscopy [2].

Impact of Gold Standard Selection on Validation Outcomes

The choice of an appropriate gold standard significantly influences validation outcomes. A study comparing microscopy and radiography for dental caries diagnosis demonstrated that using an observer's scores from the radiographs being evaluated as validation, rather than the true gold standard (microscopy), produced misleading results. Accuracy measures were significantly higher when using an observer as the 'gold standard' compared to microscopy, and compressed, degraded images paradoxically appeared more accurate than originals when using observer validation [3]. This highlights the critical importance of selecting a biologically accurate reference method rather than relying on comparative human interpretation.

Throughput and Workflow Considerations

Beyond analytical performance, practical considerations significantly impact the utility of diagnostic methods in various settings. Automated, random-access systems like the Panther platform for SARS-CoV-2 testing offer substantially reduced hands-on time (24-25 minutes) compared to manual platforms (71 minutes for R-GENE) [5]. This efficiency becomes particularly crucial during high-prevalence periods when testing demand surges. Similarly, the NeuMoDx system demonstrates the shortest turnaround time among SARS-CoV-2 testing platforms, a critical factor for timely clinical decision-making [7].

The validation of diagnostic methods against established gold standards remains essential for ensuring reliable patient care. While microscopy maintains its position as a valuable reference method for numerous infectious diseases, molecular assays increasingly demonstrate equivalent or superior performance characteristics with enhanced throughput and efficiency. The validation process must employ appropriate statistical methods and study designs to provide meaningful comparisons, while considering the practical requirements of different healthcare settings. As diagnostic technologies continue to evolve, rigorous validation ensuring "fitness for purpose" will remain the cornerstone of reliable laboratory medicine.

The Role of Microscopy as a Historical and Clinical Gold Standard

For over 150 years, light microscopy has served as the foundational tool for pathological diagnosis, establishing itself as the historical and clinical gold standard against which all newer diagnostic technologies are measured [8]. The origin of microscopy was a gradual journey, with one of the earliest advancements being the invention of spectacles in 13th century Florence [8]. The development of the first compound microscope between 1590 and 1610, credited to Galileo Galilei in 1610 (who called it "occhialino") though Dutch spectacle makers Hans and Zacharias Janssen had reportedly used telescope lenses to enlarge small objects as early as 1590, marked the beginning of microscopic visualization of biological structures [8]. This revolutionary technology enabled Rudolf Virchow in the mid-19th century to integrate microscopy into autopsy studies, transforming pathology into a scientific field and cornerstone of modern medicine [8].

The advancement of pathology required complementary breakthroughs beyond microscopy itself. The introduction of the microtone in the 1830s enabled precise tissue sectioning, while paraffin embedding (introduced by Edward Klebs in 1869) and formalin fixation (by Ferdinand Blum in 1893) standardized tissue processing [8]. Most significantly, Franz Böhm's hematoxylin staining in 1865, combined with eosin staining, created hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining that remains a diagnostic gold standard today for its exceptional clarity, cost-efficiency, and wide applicability [8]. For over a century, this combination of microscopy and H&E staining has enabled pathologists to assess cellular-level alterations, providing critical insights for diagnosis and prognosis across countless disease states.

However, the limitations of traditional microscopy—including its susceptibility to human error, inter-observer variability, low throughput, and challenges with remote collaboration—have prompted the development of sophisticated molecular alternatives [8]. This guide objectively examines how modern molecular assays are validated against the microscopic gold standard, exploring their complementary roles in contemporary diagnostic practice and research.

Clinical Applications: Traditional Microscopy Versus Molecular Assays

Vaginitis Diagnostics

The diagnostic challenge of vaginitis perfectly illustrates the ongoing transition from microscopy to molecular methods in clinical practice. Historically, vaginitis has been diagnosed using microscopy for vulvovaginal candidiasis (CV) and Trichomonas vaginalis (TV), and Amsel's criteria or Nugent scoring (which involves Gram staining) for bacterial vaginosis (BV) [9]. The ability for rapid diagnosis by provider-performed wet-mount microscopy highlights the importance of treating these infections timely due to sequelae, loss to follow-up, and stigma [9]. However, these traditional methods lack sensitivity and specificity, as some vaginal infections mimic each other, and asymptomatic infections can lead to negative health outcomes [9].

Molecular nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) represent a significant advancement. A recent clinical evaluation of the Hologic Panther Aptima BV and CV/TV assays demonstrates their performance compared to conventional methods [9].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Vaginitis Diagnostic Methods

| Diagnostic Method | Condition | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Turnaround Time | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Mount Microscopy | Trichomonas vaginalis | Low (method-dependent) | High | Minutes | Requires living organisms; low sensitivity |

| Nugent Scoring (Gram Stain) | Bacterial Vaginosis | 97.5 | 96.3 | Hours | Subjective; intermediate results challenging |

| Amsel's Criteria | Bacterial Vaginosis | Variable | Variable | Minutes | Lacks standardized interpretation |

| Hologic Panther Aptima BV Assay | Bacterial Vaginosis | 97.5 | 96.3 | Hours | Higher cost; limited clinical significance data |

| Hologic Panther Aptima CV/TV Assay | Vulvovaginal Candidiasis | 100 | 83.5 (vs. Gram stain) | Hours | Cannot differentiate Candida species |

| Hologic Panther Aptima CV/TV Assay | Trichomonas vaginalis | 100 | 100 | Hours | Higher cost than microscopy |

The table reveals a crucial diagnostic tradeoff: while molecular assays demonstrate superior sensitivity—particularly important for TV where microscopy sensitivity is low due to the need to visualize living organisms—they come with higher costs and questions about clinical significance for conditions like BV and CV where mere presence/absence of organisms doesn't necessarily indicate clinical disease [9].

Renal Transplant Rejection Diagnostics

In renal transplant pathology, a fascinating discrepancy analysis comparing the Molecular Microscope Diagnostic System (MMDx) with histology reveals critical insights about gold standard validation. Histology disagreed with MMDx in 37% of biopsies, including 315 clear discrepancies with therapeutic implications [10]. The patterns of disagreement were revealing: histology diagnoses of T cell-mediated rejection (TCMR) contained 14% MMDx antibody-mediated rejection (ABMR) and 20% MMDx no rejection [10].

Importantly, MMDx typically provided unambiguous diagnoses in cases with ambiguous histology (e.g., borderline and transplant glomerulopathy), and histology lesions associated with frequent discrepancies (tubulitis, arteritis, polyomavirus nephropathy) weren't associated with increased MMDx uncertainty [10]. This suggests molecular assessment can clarify biopsies with histologic ambiguity, though microscopy remains the foundational reference point.

Experimental Validation: Methodologies for Comparative Studies

Large-Scale Molecular-Histological Correlation

A groundbreaking 2025 study investigated correlations between nuclear features of healthy tissue cells and RNA expression patterns, providing an exemplary model for validating molecular findings against histological standards [11]. Based on 4,306 samples of 13 organs from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project, researchers constructed a deep learning-based automatic analysis framework to investigate geno-micro-correlations across tissues [11].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: H&E-stained whole slide images from GTEx database paired with RNA-Seq data [11]

- Parenchyma Extraction: Employed organ-specific methods including clustering-based approaches for breast tissue, RGB mean value thresholding for esophagus/colon/adrenal gland/pituitary/heart, and fine-tuned "Se-ResNext101" model for kidney glomeruli segmentation [11]

- Nucleus Segmentation: Implemented Efficient Deep Equilibrium Model for precise segmentation of nuclei across 13 organs [11]

- Feature Computation: Quantitative evaluation of nuclear morphological features [11]

- Molecular Correlation: Identification of gene sets specific to nuclear features and pathway analysis for biological significance [11]

This methodology demonstrates how modern validation studies leverage large-scale datasets and computational imaging to establish robust correlations between traditional histological phenotypes and molecular profiles.

Rapid Molecular Assay Development for Antimicrobial Resistance

The PathCrisp assay for detecting New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase (NDM)-resistant infections exemplifies how novel molecular diagnostics are benchmarked against established methods [12].

Experimental Protocol:

- Assay Design: Combined loop-mediated isothermal amplification and CRISPR-based detection maintained at single temperature [12]

- Specificity Validation: Designed sgRNA and LAMP primers against conserved NDM regions using 122 isolate genomic sequences [12]

- Sensitivity Testing: Determined limit of detection using serial dilutions [12]

- Method Comparison: Tested 49 carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae clinical isolates comparing PathCrisp with PCR-Sanger sequencing [12]

- Simplification: Implemented crude DNA extraction via heating rather than kit-based purification [12]

The PathCrisp assay demonstrated 100% concordance with PCR-Sanger sequencing while detecting as few as 700 NDM gene copies and providing results in approximately 2 hours [12]. This represents a significant advancement over conventional antibacterial susceptibility tests requiring 2-5 days [12].

The Evolving Diagnostic Toolkit: Integration Pathways

Digital Pathology and Computational Advances

The advent of digital pathology has created a bridge between traditional microscopy and modern computational analysis. By converting physical slides into high-resolution whole-slide images, digital pathology enables both remote expert consultation and implementation of artificial intelligence algorithms [8]. Several FDA-cleared AI systems now demonstrate this integration: Paige Prostate Detect showed 7.3% reduction in false negatives, while MSIntuit CRC triages colorectal cancer slides for microsatellite instability, prioritizing cases for confirmatory analyses [8].

Emerging technologies like Computational High-throughput Autofluorescence Microscopy by Pattern Illumination (CHAMP) promise to further transform histological imaging by enabling label-free, slide-free imaging of unprocessed tissues at 10 mm²/10 seconds with 1.1-µm resolution [13]. When combined with unsupervised learning (Deep-CHAMP), this approach can virtually stain tissue images within 15 seconds, potentially revolutionizing intraoperative assessment [13].

The Complementary Roles of Human and Digital Analysis

Rather than replacing human expertise, digital quantification complements pathological assessment. Each approach offers distinct advantages [14]:

Table 2: Pathologist Expertise vs. Software Quantification

| Aspect | Pathologist Scoring | Image Analysis Software |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | Contextual interpretation, flexible adaptation to complexity, clinical relevance | Objective reproducible measurements, fine-grained quantification, high-throughput scalability |

| Limitations | Inter-observer variability, low data resolution, labor-intensive | Parameter sensitivity, difficulty handling artifacts, lack of biological context |

| Ideal Applications | Complex diagnoses, unusual findings, clinically validated scoring systems | Large-scale studies, subtle trend detection, quantitative biomarker analysis |

The integration of both approaches creates a powerful synergy—pathologists ensure biological relevance while software provides precise metrics, enabling improved accuracy through cross-validation [14].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental protocols discussed utilize specific reagents and tools that constitute essential components of the modern pathology research toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| H&E Staining | Provides foundational cellular contrast for histological assessment | Standard tissue examination across all organ systems [8] |

| Multi-Purpose LAMP Master Mix | Enables isothermal nucleic acid amplification without thermal cycler | PathCrisp assay for NDM detection [12] |

| CRISPR/Cas12a with sgRNA | Provides specific molecular detection through collateral trans-cleavage | NDM gene detection in PathCrisp assay [12] |

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit | Extracts high-quality genomic DNA from diverse specimens | Preparation of samples for WGS in validation studies [12] |

| Efficient Deep Equilibrium Model | Segments nuclei in histology images with high accuracy | Nuclear feature extraction in GTEx study [11] |

| Cycle-Consistent GAN | Transforms label-free images into virtually stained counterparts | Deep-CHAMP for virtual H&E staining [13] |

Visualizing Diagnostic Workflows

Traditional Histopathology Workflow

Modern Molecular Validation Approach

Microscopy maintains its foundational role as the histological gold standard due to its extensive clinical validation, rich contextual information, and deep integration into medical practice and education. However, molecular assays are increasingly demonstrating complementary and, in specific applications, superior capabilities—particularly in sensitivity, objectivity, and throughput. The future of pathology lies not in replacement but in strategic integration, where microscopy provides the contextual framework and molecular methods contribute precise, quantitative data. This synergistic approach, enhanced by digital pathology and artificial intelligence, promises to advance both diagnostic accuracy and our fundamental understanding of disease mechanisms, ultimately benefiting researchers, clinicians, and patients through more precise and personalized healthcare interventions.

In the validation of molecular assays, demonstrating that a method is "fit-for-purpose" requires rigorous assessment of key performance parameters. When validating a new molecular method against an established gold standard like microscopy, understanding and quantifying specificity, sensitivity, precision, and accuracy is fundamental for researchers and drug development professionals. These parameters provide the statistical evidence that a new assay reliably detects the target analyte, delivers reproducible results, and agrees with established reference methods, ensuring confidence in data-driven decisions.

Defining the Key Validation Parameters

The following parameters form the foundation of assay validation, each providing distinct and complementary information about method performance.

| Parameter | Definition | What It Measures | Common Formulae |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity [15] [16] [17] | Ability to correctly identify the absence of a condition or analyte; measures true negatives. | How well the assay detects only the target analyte without interference from other components. | Specificity = True Negatives / (True Negatives + False Positives) |

| Sensitivity [15] [16] [17] | Ability to correctly identify the presence of a condition or analyte; measures true positives. | The lowest amount of analyte an assay can detect and/or reliably quantify. | Sensitivity = True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives) |

| Precision [15] [18] [19] | The closeness of agreement between a series of measurements from multiple sampling of the same sample. | The random variation and reproducibility of the assay results under defined conditions. | Reported as % Relative Standard Deviation (%RSD) |

| Accuracy [15] [18] [16] | The closeness of agreement between a test result and an accepted reference or true value. | How close the measured value is to the true value, often expressed as percent recovery. | % Recovery = (Measured Value / True Value) x 100 |

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Assessment

Validating a new molecular assay against a gold standard requires a structured experimental approach. The protocols below outline key methodologies for generating the data needed to calculate these essential performance parameters.

Protocol for Specificity and Sensitivity Assessment

This experiment is designed to challenge the assay's ability to correctly identify true positives and true negatives, often using samples with known status determined by the gold standard method (e.g., microscopy).

- Sample Preparation: Obtain a panel of well-characterized samples. This should include samples confirmed positive for the target via the gold standard and samples confirmed negative. To test for cross-reactivity, include samples with potentially interfering substances that are structurally similar or commonly found in the sample matrix.

- Experimental Procedure: Process all samples through the new molecular assay using a blinded protocol so the operator is unaware of the known status. The results from the new assay (positive/negative) are then compared to the results from the gold standard test.

- Data Analysis: Construct a 2x2 contingency table to compare the outcomes. Calculate Sensitivity and Specificity using the formulae provided in the table above [17]. For a validation against microscopy, a high sensitivity is critical to ensure the molecular assay does not miss true positives identified by the gold standard.

Protocol for Precision Evaluation

Precision is evaluated at multiple levels to assess repeatability and intermediate precision, which is crucial for establishing the assay's reliability in a real-world laboratory setting [18].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a homogeneous sample at a concentration within the quantitative range of the assay. Aliquots of this single sample are used for all precision testing.

- Experimental Procedure:

- Repeatability (Intra-assay): One analyst tests the multiple aliquots of the sample in a single run, using the same instrument and reagents [18]. The guidelines recommend a minimum of nine determinations across at least three concentration levels [15] [18].

- Intermediate Precision: A second analyst repeats the experiment on a different day, using a different instrument and preparing new reagents and standards [18]. This assesses the impact of normal, within-laboratory variations.

- Data Analysis: For each set of results (from Analyst 1 and Analyst 2), calculate the mean, standard deviation, and %RSD. The results from the two analysts can be subjected to statistical testing (e.g., Student's t-test) to determine if there is a significant difference in the mean values [18].

Protocol for Accuracy Determination

Accuracy is established by testing samples with known concentrations of the analyte and comparing the measured value to the expected value [15] [18].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare samples (in the appropriate matrix) spiked with known concentrations of the analyte. A minimum of nine determinations over three concentration levels (e.g., low, mid, and high) covering the specified range of the assay is recommended [15] [18].

- Experimental Procedure: Analyze each of the spiked samples using the new molecular assay.

- Data Analysis: For each spiked sample, calculate the percent recovery: (Measured Concentration / Known Concentration) x 100. The overall accuracy of the method is demonstrated by the mean percent recovery across all tested concentrations and the confidence intervals (e.g., ±1 standard deviation) [18].

Visualizing Diagnostic Test Outcomes

The relationship between a new assay's results and the true disease status, as determined by a gold standard, is best understood through a contingency table. This framework allows for the calculation of all key validation parameters, highlighting the critical balance between sensitivity and specificity [17].

Diagram: Diagnostic Test Outcomes vs. Gold Standard. This 2x2 table illustrates how true positives, false positives, false negatives, and true negatives are defined in relation to a gold standard test, forming the basis for calculating sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following reagents and instruments are critical for executing the validation protocols for molecular assays, such as PCR-based methods, against a gold standard like microscopy.

| Item | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Well-Characterized Sample Panel | Serves as the primary material for specificity/sensitivity testing. Includes samples with known status (positive/negative) confirmed by the gold standard and samples with potential interferents [15] [17]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Provides the known, true quantity of the analyte for spiking experiments to establish accuracy and the standard curve for linearity. Essential for generating data on percent recovery [18]. |

| Homogeneous Sample Material | A single, well-mixed sample is used for precision testing (repeatability and intermediate precision) to ensure that any variation measured is from the assay itself and not from the sample [18]. |

| Appropriate Instrumentation | The analytical platform (e.g., qPCR machine, sequencer) must be properly qualified to ensure its performance does not adversely affect the validation data. This is a prerequisite for reliable method validation [18]. |

The rigorous validation of a molecular assay against a gold standard like microscopy is a cornerstone of reliable scientific research and drug development. By systematically quantifying specificity, sensitivity, precision, and accuracy, researchers can provide compelling, data-driven evidence of their assay's reliability. This process not only ensures the integrity of experimental data but also builds the foundational trust required for adopting new technologies in clinical and regulatory decision-making. As methodological advancements continue, these core validation parameters will remain the universal language for demonstrating assay quality and fitness-for-purpose.

The validation of new diagnostic tools against established gold standards is a critical cornerstone in the advancement of medical science. For centuries, manual microscopy has served as this foundational standard in pathology and microbiology, providing the benchmark against which newer technologies are measured [1] [20]. The transition to innovative molecular assays and digital platforms necessitates rigorous validation across multiple contexts to ensure diagnostic accuracy, reliability, and patient safety are maintained. This comparative guide examines the distinct frameworks of vendor-driven, academic, and clinical laboratory validation studies, with a specific focus on their application in validating molecular assays against microscopy gold standards. Each pathway addresses different objectives, regulatory requirements, and performance metrics, yet all converge on the common goal of establishing diagnostic confidence for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals navigating this evolving landscape.

Defining the Three Validation Contexts

Validation studies are conducted in three primary contexts, each with distinct objectives, methodologies, and regulatory considerations. Understanding these frameworks is essential for interpreting validation data and applying it appropriately in research and clinical settings.

Vendor-Driven Studies are conducted by manufacturers to obtain regulatory clearance for their devices. These studies are comprehensive, targeting specific regulatory milestones such as FDA 510(k) clearance, and are designed to demonstrate that a new system performs as reliably as the established gold standard for its intended use [1]. The recent FDA clearance of Roche's Digital Pathology Dx system exemplifies this context, where massive clinical performance studies were conducted to prove non-inferiority to manual microscopy [20].

Academic Studies aim to explore the general feasibility, applicability, and limitations of new technologies through peer-reviewed research [1]. These investigations often examine broader research questions beyond immediate regulatory needs, such as novel applications or methodological innovations. For instance, academic research into leprosy diagnostics has evaluated new recombinant protein antigens and fusion versions like LID-1, exploring their potential for point-of-care testing beyond what current vendor offerings provide [21].

Clinical Laboratory Studies are performed by individual laboratories to validate a technology within their specific operational environment [1]. These studies ensure the combination of technology, personnel, and workflows in a particular laboratory setting produces reliable results for patient care. According to current standards, clinical validation of digital microscopy for primary diagnostic work is required for each laboratory initiating a transition from light microscopy to digital systems [1].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Validation Contexts

| Validation Aspect | Vendor-Driven Studies | Academic Studies | Clinical Laboratory Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Regulatory clearance and market approval [1] | General feasibility and novel applications [1] | Implementation in specific laboratory environment [1] |

| Typical Scale | Large, multi-site (e.g., 2,047 cases in Roche study) [20] | Variable, often limited by research scope | Tailored to laboratory's specific caseload and needs |

| Regulatory Focus | FDA, IVDR, and other regulatory body requirements [22] | Peer review and publication standards | Accreditation standards (e.g., ISO 15189) [22] |

| Outcome Measures | Precision, accuracy, non-inferiority [20] [23] | Novel biomarkers, mechanisms, methodologies [21] | Concordance with existing in-house methods |

| Key Stakeholders | Regulatory agencies, manufacturers [1] | Scientific community, journals [1] | Laboratory directors, accrediting bodies [24] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Validation studies employ meticulously designed protocols to generate statistically meaningful evidence of performance equivalence or superiority. The methodologies vary significantly across the three contexts but share common elements of rigorous comparison against reference standards.

Vendor-Driven Validation Protocols

Vendor-driven studies follow structured frameworks negotiated with regulatory bodies. The Roche Digital Pathology Dx validation exemplifies this approach, employing two complementary study designs [20]:

Precision/Inter-laboratory Reproducibility Study:

- Objective: Test repeatability and reproducibility across multiple sites

- Design: 23 histopathologic features across 3 sites, with slides scanned on 3 non-consecutive days

- Case Set: 69 glass slide "cases" (3 slides × 23 features) plus 12 "wildcard" cases

- Output Measurement: Percent agreement for feature identification between systems, days, and readers with predetermined acceptance criteria (lower bound of 95% CI ≥85%) [20]

Method Comparison/Accuracy Study:

- Objective: Compare diagnostic accuracy between digital and microscopy reads

- Design: 2,047 clinical cases evaluated by pathologists using both digital reads and manual microscopy

- Reference Standard: Original sign-out diagnosis

- Statistical Analysis: Non-inferiority testing with predetermined margin (-4% lower bound), difference in accuracy calculated as digital reads minus manual microscopy reads [20]

The Roche system successfully met all predetermined endpoints, with precision between systems/sites at 89.3%, between days at 90.3%, and between readers at 90.1%. The difference in accuracy between digital reads and manual microscopy was -0.61% (lower bound of 95% CI: -1.59%), demonstrating non-inferiority [20].

Academic Validation Methodologies

Academic studies often explore more innovative approaches while still maintaining methodological rigor. Research on leprosy diagnostics illustrates this context, focusing on validating molecular assays against microscopic examination of skin biopsies and slit-skin smears [21].

Molecular Detection of Mycobacterium leprae:

- Reference Standard: Microscopic identification of acid-fast bacilli in intradermal smears or histopathology sections [21]

- Index Test: Quantitative polymerase chain reaction targeting M. leprae-specific genes (e.g., RLEP gene) [21]

- Sample Considerations: Validation across leprosy spectrum (paucibacillary vs. multibacillary) with appropriate clinical correlation

- Performance Metrics: Sensitivity, specificity, limit of detection compared to microscopic bacillary index [21]

Academic validation of the PathCrisp assay for detecting NDM-resistant infections demonstrates another approach, combining loop-mediated isothermal amplification with CRISPR-based detection while maintaining a single temperature [12]. This methodology demonstrated 100% concordance with PCR-Sanger sequencing and sensitivity to detect as few as 700 copies of the NDM gene from clinical isolates [12].

Clinical Laboratory Verification Protocols

Clinical laboratories implement focused verification protocols tailored to their specific operational needs and patient populations. These studies typically follow established guidelines while adapting to local constraints [24].

Essential Verification Studies for FDA-Approved Tests:

- Precision: Within-run and day-to-day measurement using quality control materials

- Accuracy: Method comparison with 40 patient samples spanning analytical measurement range

- Reportable Range: Verification using samples across the analytical measurement range

- Reference Range Verification: Confirmation of manufacturer's reference intervals [24]

For non-FDA-approved tests or laboratory-developed tests, additional validation is required, including analytical sensitivity (limit of detection) and analytical specificity (interference studies) [24]. Performance goals are predefined based on allowable total error, with acceptability criteria established for each study before commencement [24].

Diagram 1: Clinical Laboratory Test Validation Workflow. This diagram outlines the decision process for validating both FDA-approved tests and laboratory-developed tests (LDTs), highlighting the additional requirements for LDTs [24].

Comparative Performance Data Analysis

Quantitative performance data forms the evidentiary foundation for diagnostic validation across all three contexts. Systematic comparison of this data reveals both consistencies and variations in validation approaches and outcomes.

Table 2: Validation Performance Metrics Across Diagnostic Technologies

| Technology Platform | Validation Context | Key Performance Metrics | Reference Standard | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roche Digital Pathology Dx [20] | Vendor-Driven | Precision: 89.3%-90.3%Accuracy: -0.61% differenceReading time: 2.33 min (digital) vs 2.34 min (microscopy) | Manual microscopy | Non-inferiority demonstrated (lower bound 95% CI > -4%) |

| qPCR for M. leprae [21] | Academic | Sensitivity: High in multibacillary casesSpecificity: M. leprae-specificLimitation: Lower sensitivity in paucibacillary cases | Microscopic bacilloscopy of skin smears | Auxiliary diagnostic for confirmation, not replacement |

| PGL-I Serology POCT [21] | Academic | Sensitivity: High in multibacillary patientsSpecificity: VariableUtility: Equipment-free, rapid results | Clinical diagnosis with microscopic correlation | Recommended adjunct test, not stand-alone diagnosis |

| PathCrisp (LAMP+CRISPR) [12] | Academic | Sensitivity: 700 copy detectionConcordance: 100% with PCR-SangerTime: ~2 hours | PCR with Sanger sequencing | High sensitivity and specificity demonstrated |

| Digital Microscopy [1] | Clinical Laboratory | Diagnostic concordance: >95% typicallyVariation: Laboratory-dependent | Light microscopy | Implementation-specific performance |

The tabulated data reveals several important patterns. Vendor-driven studies typically employ large sample sizes and rigorous statistical margins to demonstrate non-inferiority, as seen in the Roche digital pathology system which utilized 2,047 cases to prove diagnostic equivalence to manual microscopy [20]. Academic studies often focus on more specific performance characteristics, such as the differential sensitivity of molecular leprosy tests between multibacillary and paucibacillary cases, acknowledging limitations while advancing the technology [21]. Clinical laboratory validations prioritize practical implementation metrics that ensure reliability in local practice settings.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Validation studies across all contexts rely on specialized reagents and materials to ensure accurate, reproducible results. These research tools form the foundation of reliable assay performance and comparability.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Diagnostic Validation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Phenolic Glycolipid-I (PGL-I) Antigens [21] | Semi-synthetic antigen for serological detection of M. leprae antibodies | Leprosy point-of-care tests, ELISA-based serology |

| LID-1/NDO-LID Fusion Antigens [21] | Recombinant protein antigens for improved serodiagnosis | Enhanced sensitivity leprosy serology, particularly in multibacillary cases |

| RLEP Gene Primers/Probes [21] | M. leprae-specific DNA target for molecular amplification | qPCR detection of M. leprae in clinical specimens |

| CRISPR/Cas12a with sgRNA [12] | Sequence-specific nucleic acid detection with collateral cleavage activity | PathCrisp assay for NDM gene detection |

| Bst Polymerase for LAMP [12] | Strand-displacing DNA polymerase for isothermal amplification | Loop-mediated isothermal amplification without thermal cycler |

| Whole Slide Imaging Systems [20] | Digital conversion of glass slides for virtual microscopy | Digital pathology primary diagnosis validation |

| International Color Consortium Profiles [20] | Standardized color management for digital pathology | Consistent color representation across digital pathology platforms |

Regulatory and Methodological Considerations

Validation approaches must adapt to evolving regulatory landscapes and methodological innovations. Understanding these frameworks is essential for designing compliant and effective validation studies.

Regulatory Evolution: The recent implementation of the European Commission's In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation and updates to ISO 15189 standards have increased requirements for validation and verification procedures [22]. These changes affect all validation contexts but place particular burdens on clinical laboratories to demonstrate rigorous method evaluation.

Allowable Total Error Framework: Performance goals for validation studies are increasingly defined through Allowable Total Error, which combines precision and accuracy metrics against clinically relevant thresholds [24]. This framework necessitates careful selection of acceptance criteria based on biological variation, clinical outcome studies, or state-of-the-art performance for each analyte.

Technology-Specific Challenges: Different technologies present unique validation challenges. For digital pathology, these include color representation fidelity, scan resolution adequacy, and focus layer requirements for cytology specimens [1]. For molecular assays, challenges include extraction efficiency, amplification inhibitors, and target sequence conservation [12].

The increasing integration of artificial intelligence and computational pathology into diagnostic systems introduces additional validation complexity, requiring demonstration of both analytical and clinical validity for algorithm-based interpretations [25].

Validation of diagnostic technologies against microscopy gold standards proceeds through three complementary yet distinct pathways, each serving essential roles in the technology adoption lifecycle. Vendor-driven studies provide the regulatory foundation for market approval through massive, rigorous demonstrations of non-inferiority. Academic investigations explore novel applications, mechanisms, and methodological innovations that push the boundaries of diagnostic capabilities. Clinical laboratory validations translate these advances into daily practice through localized verification of performance in specific operational environments.

The convergence of evidence from these three contexts builds the comprehensive understanding necessary for diagnostic implementation. As technological innovation accelerates, particularly in digital pathology and molecular diagnostics, this tripartite validation framework ensures that progress is matched by preserved diagnostic accuracy and patient safety. Researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals must navigate all three contexts to effectively advance and implement new diagnostic technologies in both research and clinical practice.

In the validation of molecular assays for diagnostic use, the process is typically benchmarked against an established gold standard, often traditional light microscopy (LM) in pathology [1]. This framework, however, operates on the critical assumption that the gold standard itself is perfect—an assumption that is frequently flawed [26]. Diagnostic concordance between a new method and the reference standard can be significantly influenced by multiple sources of bias, chief among them being the complexity of the cases examined and the diagnostic experience of the pathologists involved [27] [1]. A precise understanding of these biases is not merely academic; it is fundamental to designing robust validation studies for molecular assays, accurately interpreting their performance data, and ensuring their safe implementation in clinical and research settings. This guide objectively compares the performance of diagnostic methods by examining the experimental data on how case complexity and expertise shape diagnostic concordance, providing a crucial framework for researchers and drug development professionals validating new technologies against microscopic standards.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Diagnostic Concordance

To objectively compare diagnostic performance and understand sources of bias, researchers employ specific experimental designs. The following protocols are central to generating the data discussed in this guide.

Intra-observer Concordance Studies

This design is a cornerstone of digital pathology validation and is equally applicable to molecular assay verification [27] [1]. In this protocol, the same set of cases is evaluated first by the new method (e.g., a molecular assay or digital pathology) and then by the traditional gold standard (LM), with both assessments performed by the same pathologist. A washout period is incorporated between reviews to mitigate memory bias [1]. The primary outcome measure is the diagnostic concordance rate between the two modalities for the same observer [27]. This design directly tests the technological agreement between methods while controlling for inter-observer variability.

Expert Review versus Original Diagnosis

This protocol measures the impact of pathologist experience directly. A set of cases with an original diagnosis from a general pathologist is re-evaluated by a specialist pathologist (e.g., a sarcoma expert) [28]. The specialist typically has access to the same or additional material (including molecular data) to render a final diagnosis. The modification rate between the original and expert diagnoses is the key metric, which can be further categorized into changes that affect patient management (major discrepancies) and those that do not (minor discrepancies) [28]. This design quantifies the variability introduced by diagnostic expertise.

Bayesian Latent Class Models (LCMs)

When no perfect gold standard exists, Bayesian LCMs provide a statistical framework to estimate the true accuracy of diagnostic tests [26]. These models do not assume any test is perfect but instead estimate true disease prevalence and the sensitivity and specificity of each test simultaneously based on the observed patterns of agreement and disagreement across multiple tests applied to the same population [26]. This is particularly useful for validating new molecular assays in fields where the reference standard is known to be imperfect.

Quantitative Data: Factors Influencing Diagnostic Concordance

The following tables synthesize experimental data from published studies, summarizing the impact of key variables on diagnostic outcomes.

Table 1: Impact of Case Complexity and Diagnostic Expertise on Concordance and Modification Rates

| Factor | Study Context | Key Metric | Result | Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall DP vs. LM Concordance | Meta-analysis of 24 studies (10,410 samples) [27] | Overall Clinical Concordance | 98.3% (95% CI 97.4 to 98.9) | Intra-observer concordance studies |

| Major Discordances (DP vs. LM) | Meta-analysis of 25 studies [27] | Proportion of Major Discordances | 546 major discordances reported | Analysis of discordant cases across multiple studies |

| Expert Review in Sarcoma | Prospective study of 119 sarcoma cases [28] | Diagnosis Modification Rate | 31.1% (37/119 cases) | Expert vs. original diagnosis review |

| Impact on Management (Sarcoma) | Prospective study of 119 sarcoma cases [28] | Management Modification Rate | 14.2% (17/119 cases) | Expert vs. original diagnosis review |

Table 2: Analysis of Major Diagnostic Discordances in Digital Pathology [27]

| Category of Major Discordance | Proportion of All Major Discordances | Specific Examples or Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Atypia, Grading of Dysplasia & Malignancy | 57% | Assessment of nuclear features, grading of cancerous and pre-cancerous lesions. |

| Challenging Diagnoses | 26% | Inherently difficult cases with overlapping histological features. |

| Identification of Small Objects | 16% | Finding small or sparse microscopic objects (e.g., microorganisms, mitotic figures). |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and materials are essential for conducting rigorous validation studies in diagnostic pathology.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Validation Studies

| Item | Function in Validation | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| FFPE Tissue Blocks | The primary source material for generating histology slides and nucleic acid extraction. | Ensure a range of case complexities and diagnoses. |

| H&E Stains | The foundational stain for histological diagnosis, used for initial morphological assessment. | Central to most validation study protocols [27]. |

| RNA/DNA Extraction Kits | To isolate genetic material for molecular testing via NGS or PCR. | Quality of extraction critical for NGS success [28]. |

| Targeted NGS Panels | For detecting gene fusions, mutations, and other genetic alterations. | e.g., 86-gene fusion panel for sarcoma diagnosis [28]. |

| FISH Assays | To validate specific genetic rearrangements or amplifications. | e.g., MDM2 amplification for liposarcoma diagnosis [28]. |

| Immunohistochemistry Kits | For protein-level detection of biomarkers to aid in diagnosis and classification. | Often used in the initial workup by expert pathologists. |

Visualizing Workflows and Bias Relationships

Diagnostic Validation and Bias Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for a diagnostic validation study and the key points where bias can be introduced and analyzed.

Interplay of Factors Affecting Diagnostic Concordance

This diagram maps the logical relationships between the core factors of case complexity, pathologist experience, and the resulting diagnostic concordance, also showing how these elements feed into assay validation.

The validation of molecular assays against the traditional gold standard of light microscopy is a complex process fraught with potential bias. Experimental data consistently shows that diagnostic concordance is not uniform but is significantly influenced by case complexity—with nuclear atypia and dysplasia being major sources of discordance—and by the expertise of the diagnosing pathologist. A prospective study on sarcomas, for instance, found that expert review modified the original diagnosis in nearly a third of cases, directly altering patient management in over 14% of them [28]. Therefore, a robust validation framework must proactively account for these variables. This involves stratifying cases by complexity, incorporating expert review, and utilizing statistical models like Bayesian LCMs that do not presume the infallibility of the gold standard. For researchers and drug developers, this rigorous, bias-aware approach is fundamental to generating reliable performance data and ensuring that new diagnostic technologies are validated against the most accurate diagnostic truth possible.

From Theory to Bench: Implementing Molecular Assays for Pathogen Detection

The validation of molecular assays against traditional gold standards, such as microscopy, is a cornerstone of diagnostic research. This process ensures that new, rapid methods provide reliable and actionable results. Nucleic acid tests (NATs) have revolutionized diagnostic science by offering superior speed and sensitivity for detecting pathogens and genetic markers. Among these, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) has long been the benchmark technique. However, the emergence of isothermal amplification methods, particularly loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) and its advanced derivatives like PathCrisp, presents compelling alternatives. These isothermal techniques challenge the conventional paradigm by offering simplicity and portability without relying on sophisticated thermal cycling equipment. This guide objectively compares the performance of qPCR, LAMP, and PathCrisp, providing experimental data and protocols to help researchers select the appropriate method for their validation studies against microscopy and other standards.

qPCR (Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction)

qPCR is a thermal-cycling-dependent method that amplifies and simultaneously quantifies a specific DNA target. It relies on repeated cycles of denaturation (at high temperatures, ~95°C), annealing (at primer-specific temperatures, ~50-65°C), and extension (~72°C) to exponentially amplify nucleic acids. Fluorescent probes or DNA-binding dyes allow real-time monitoring of the amplification process, enabling quantification of the initial target concentration based on the cycle threshold (Ct) value, the point at which fluorescence crosses a predefined threshold [29] [30]. Its requirement for precise temperature control and sophisticated instrumentation has been a key driver in the development of alternative methods.

LAMP (Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification)

LAMP is an isothermal nucleic acid amplification technique that operates at a constant temperature, typically between 60-65°C. It utilizes a strand-displacing DNA polymerase (e.g., Bst polymerase) and four to six specially designed primers that recognize six to eight distinct regions on the target genome. The amplification process involves the formation of stem-loop DNA structures, leading to very efficient amplification without the need for thermal denaturation. Results can be visualized through turbidity (from magnesium pyrophosphate precipitate), fluorescent intercalating dyes, or colorimetric changes [31] [32] [30]. This simplicity makes it suitable for point-of-care settings.

PathCrisp

PathCrisp represents a next-generation diagnostic tool that combines the amplification power of LAMP with the specific detection capabilities of the CRISPR-Cas12a system. In this method, LAMP first amplifies the target nucleic acid isothermally. The amplified products are then recognized by a CRISPR-Cas12a complex programmed with a specific guide RNA (crRNA). Upon binding to its target, the Cas12a enzyme is activated and exhibits collateral activity, cleaving nearby single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) reporters. This cleavage generates a fluorescent or colorimetric signal, providing a highly specific readout [12] [33]. This two-step verification process enhances specificity and reduces false positives.

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data

The following tables summarize key performance metrics from published studies comparing these NATs across various applications, from pathogen detection to antimicrobial resistance screening.

Table 1: Comparative Analytical Sensitivity of NATs from Clinical Studies

| Assay | Target | Pathogen/Application | Limit of Detection (LoD) | Source/Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT-qPCR | SARS-CoV-2 RNA | COVID-19 | 30-50 copies [34] | Bruce et al., 2020 |

| RT-qPCR (CDC) | SARS-CoV-2 RNA | COVID-19 | Most accurate among tested [29] | PMC10170900, 2023 |

| RT-LAMP | SARS-CoV-2 RNA | COVID-19 | 400-500 copies [34]; 71% sensitivity vs RT-qPCR on direct swabs [35] | Garafutdinov et al., 2020 |

| LAMP | Alternaria solani DNA | Plant Fungal Pathogen | 10-fold more sensitive than conventional PCR [31] | Frontiers in Microbiology, 2018 |

| Nested PCR | Alternaria solani DNA | Plant Fungal Pathogen | 100-fold more sensitive than LAMP [31] | Frontiers in Microbiology, 2018 |

| PathCrisp | NDM Gene | Antimicrobial Resistance | 700 copies; 100% concordance with PCR-Sanger sequencing [12] [36] | Scientific Reports, 2025 |

Table 2: Operational Characteristics and Practical Performance

| Parameter | qPCR/RT-qPCR | LAMP/RT-LAMP | PathCrisp |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amplification Temperature | Multiple (Thermocycling: ~95°, ~60°, ~72°C) | Constant (Isothermal: ~60-65°C) | Constant (Isothermal: LAMP at ~60°C, CRISPR at ~37°C) |

| Assay Time | 1.5 - 2 hours [34] [30] | ~45 - 70 minutes [31] [32] [35] | ~2 hours total [12] |

| Instrument Requirement | Complex (Thermal Cycler, Fluorometer) | Simple (Water Bath/Block Heater) | Simple (Water Bath/Block Heater) |

| Sensitivity | High (Gold Standard) | Moderate to High (Platform-dependent) | High |

| Specificity | High | High (from multiple primers) | Very High (Dual-check: LAMP + CRISPR) |

| Ease of Use | Requires trained personnel | Simpler; suitable for point-of-care | Requires careful setup but simple readout |

| Sample Preparation | Often requires purified RNA/DNA | Tolerant to crude samples; can use simple heating [12] [31] | Can use crude extraction from culture [12] |

| Key Advantage | Gold standard, quantitative | Rapid, simple, equipment-free | High specificity, low false positives |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure the reproducibility of results in a research setting, detailed protocols for key experiments are provided below.

Protocol: RT-qPCR for SARS-CoV-2 Detection (CDC Protocol)

This protocol is adapted from the study that found the CDC (USA) RT-qPCR protocol to be the most accurate for COVID-19 diagnosis [29].

- Sample Collection and RNA Extraction: Collect oro-nasopharyngeal swabs. Extract RNA using a commercial kit like QIAmp Viral RNA Kit (QIAGEN). Store extracted RNA at -80°C if not used immediately.

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a 20 μL reaction mixture containing:

- GoTaq Probe qPCR Master Mix with dUTP (10 μL)

- GoScript RT Mix for one-step RT-qPCR (0.4 μL)

- Sense and antisense primers (500 nM each) targeting the N1 and N2 genes of SARS-CoV-2

- Probes (125 nM)

- Nuclease-free water and 5 μL of template RNA

- Amplification Conditions: Run the reaction on a real-time PCR instrument with the following program:

- 45°C for 15 min (Reverse transcription)

- 95°C for 2 min (Initial denaturation)

- 40 cycles of: 95°C for 15 s (Denaturation) and 60°C for 1 min (Annealing/Extension)

- Result Interpretation: A sample is considered positive if amplification of both N1 and N2 gene fragments is detected at a cycle threshold (Ct) ≤ 37.

Protocol: LAMP Assay for Fungal Pathogen Detection

This protocol for detecting Alternaria solani, the causative agent of early blight in potatoes, demonstrates LAMP's application in plant pathology [31].

- DNA Extraction: Harvest mycelia from cultured isolates. Air-dry, then grind. Extract genomic DNA using a commercial kit (e.g., Bioteke kit) and quantify it with a spectrophotometer.

- Primer Design: Design LAMP primers (F3, B3, FIP, BIP) targeting a specific gene, such as the histidine kinase gene (HK1), using software like Primer Explorer V4.

- LAMP Reaction: Prepare a 25 μL reaction mixture containing:

- 2× reaction buffer (12.5 μL)

- Bst DNA polymerase (e.g., 0.4 μL of Bst1.0 enzyme)

- Outer primers (F3, B3; 0.2 μM each)

- Inner primers (FIP, BIP; 1.6 μM each)

- Target DNA template (1-2 μL)

- Incubation and Detection: Incubate the reaction at a constant temperature of 63°C for 60 minutes. Stop the reaction by heating at 80°C for 5 minutes. Detect amplification via:

- Visual Inspection: Add an intercalating dye like SYBR Green I; a color change under UV light indicates a positive result.

- Turbidity: Directly observe the white precipitate of magnesium pyrophosphate.

- Gel Electrophoresis: Analyze the product for a characteristic ladder-like pattern.

Protocol: PathCrisp Assay for NDM Resistance Gene Detection

This protocol outlines the two-step method for detecting the New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase (NDM) gene, a critical marker of carbapenem resistance [12].

- Step 1: LAMP Amplification

- Sample Preparation: Use crude bacterial lysate obtained by heating a colony, or purified DNA.

- LAMP Reaction: Set up a reaction with a LAMP master mix (e.g., Multi-Purpose LAMP Master Mix), Bst polymerase, and six specific LAMP primers designed to the conserved region of the NDM gene.

- Incubation: Incubate at 60°C for 1 hour.

- Step 2: CRISPR-Cas12a Detection

- Detection Mix Preparation: Pre-incubate 26 nM of Cas12a enzyme with 26 nM of target-specific sgRNA in an appropriate buffer (e.g., 1× NEBuffer 2.1) at room temperature for 10 minutes to form the RNP complex. Add a fluorescent ssDNA reporter (e.g., 200 nM of ssDNA-FQ with FAM and quencher).

- Trans-Cleavage Reaction: Add 10 μL of the LAMP amplification product to the detection mix. Incubate at 37°C for 10-20 minutes.

- Signal Readout: Measure fluorescence in real-time using a fluorimeter (excitation/emission: 480/520 nm). A positive result is indicated by a significant increase in fluorescence relative to the no-template control.

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The diagrams below illustrate the core workflows and detection mechanisms for each nucleic acid test.

qPCR Workflow

qPCR involves cyclic temperature changes for amplification with real-time fluorescence monitoring.

LAMP Mechanism

LAMP uses multiple primers for isothermal amplification, generating products that yield visual signals.

PathCrisp Detection Principle

PathCrisp couples LAMP amplification with CRISPR-Cas12a activation, triggering a fluorescent reporter.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of these NATs relies on specific reagents and materials. The following table details essential components for setting up these assays.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for NATs

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example Product/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Bst DNA Polymerase | Strand-displacing enzyme for LAMP amplification; enables isothermal reactions. | Available from suppliers like New England Biolabs (NEB). Critical for LAMP and PathCrisp [12] [31]. |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Thermostable enzyme for PCR/qPCR; synthesizes new DNA strands during thermal cycling. | Often part of a master mix (e.g., GoTaq Probe qPCR Master Mix [29]). |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Converts RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) for RT-qPCR and RT-LAMP. | M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase [34] or enzymes in one-step kits. |

| LAMP Primers | Set of 4-6 primers that bind to multiple regions of the target for specific isothermal amplification. | Designed with software like Primer Explorer V4 [31]. |

| CRISPR-Cas12a Enzyme & sgRNA | Cas12a nuclease and specific guide RNA for target recognition and collateral cleavage in PathCrisp. | Alt-R L.b. Cas12a (Cpf1) Ultra (IDT) [12]. The sgRNA is designed to a conserved target region. |

| Fluorescent Probe/Reporter | For real-time signal detection. In qPCR, a target-specific probe; in PathCrisp, a nonspecific ssDNA reporter. | TaqMan probes (qPCR) [29]; ssDNA-FQ with FAM/Quencher (PathCrisp) [12] [33]. |

| Intercalating Dye | Binds double-stranded DNA for detection in LAMP and some qPCR applications. | SYBR Green I [34]. Can be used for visual or fluorometric readouts. |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit | Purifies DNA/RNA from complex samples (swabs, tissue, culture). | QIAmp Viral RNA Kit [29], Magnetic bead-based kits [33]. |

| dNTPs | Nucleotides (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) that are the building blocks for DNA synthesis. | Essential for all amplification reactions [12] [34]. |

| Isothermal Buffer | Provides optimal pH, salt, and Mg²⁺ conditions for Bst polymerase activity. | Often included with the enzyme (e.g., NEBuffer, SD polymerase buffer [12] [34]). |

The choice between qPCR, LAMP, and advanced systems like PathCrisp depends heavily on the research context and the parameters of the validation study against a gold standard. qPCR remains the undisputed reference for quantitative accuracy and sensitivity in a controlled laboratory environment. LAMP offers a robust, rapid, and equipment-minimal alternative, ideal for field-use or point-of-care testing where speed and simplicity are paramount, even with a potential slight trade-off in sensitivity for some sample types. PathCrisp and other CRISPR-integrated assays represent a significant leap forward in specificity, effectively minimizing false positives through a dual-check mechanism, which is crucial for detecting specific resistance markers or low-abundance pathogens.

For researchers validating these assays against microscopy, the decision matrix is clear: use qPCR for establishing a quantitative baseline and maximum sensitivity; employ LAMP for rapid screening and settings where resources are limited; and adopt PathCrisp-like technology when unambiguous, high-specificity detection of a genetic marker is the primary goal. As these technologies continue to evolve, their integration into diagnostic pipelines will further bridge the gap between central laboratories and field-based diagnostics, enhancing our ability to respond to infectious disease threats and antimicrobial resistance.

The accurate quantification of Plasmodium falciparum is a cornerstone of modern malaria research, directly impacting the assessment of vaccine efficacy, drug treatments, and our understanding of parasite biology in controlled human malaria infection (CHMI) studies [37]. For decades, microscopy has served as the gold standard for parasite detection and quantification, but this method faces challenges related to sensitivity and operator expertise [38]. The emergence of quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) methodologies has introduced a powerful alternative capable of detecting sub-microscopic parasite densities, but requires rigorous validation to ensure reliability [37] [38].

This case study examines the comprehensive validation of a qPCR assay for P. falciparum quantification, positioning its performance against traditional microscopy and rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs). The validation framework encompasses specificity, sensitivity, accuracy, precision, and linearity assessments, providing researchers with a standardized approach for implementing molecular quantification in malaria studies [37]. As drug development professionals increasingly rely on precise parasite metrics for efficacy determinations, validated qPCR methods offer the reproducibility and sensitivity required for robust clinical trial outcomes.

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Parasite Culture and Standard Preparation

The validation process began with the cultivation of P. falciparum 3D7 parasites in human red blood cell suspensions using RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with L-glutamine, HEPES, gentamicin, glucose, and hypoxanthine [37]. Cultures were maintained at 37°C under 5% CO2 and synchronized at the ring stage using 5% sorbitol treatment to ensure stage-specific homogeneity [37]. The quantification of infected red blood cells was performed using flow cytometry, where 5μL of harvested P. falciparum-infected RBCs were stained with 1:1000 SYBR green for 30 minutes, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline, and analyzed using a BD FACS Canto with an acquisition of 1,000,000 events per sample [37].

For the standardized parasite dilution series, donor whole blood from O-positive healthy donors was screened for the absence of P. falciparum using rapid diagnostic tests and confirmed by Taqman 18S rRNA qPCR [37]. These donor blood samples were subsequently spiked with in vitro cultured and counted asexual stage frozen P. falciparum parasites. A two-fold serial dilution of spiked whole blood was created, generating a parasite count range of 0.25 to 2,500 parasites/μL, which served as reference material for the validation experiments [37].

DNA Extraction and qPCR Protocol

DNA extraction was performed from whole blood spiked with P. falciparum using the QIAsymphony machine for automated DNA extraction and purification according to the manufacturer's instructions [37]. To determine the impact of blood volume on assay sensitivity, extractions were performed using four different sample volumes: 200μL, 400μL, 500μL, and 1000μL, with each extraction including known positive and negative control samples [37]. DNA was eluted in 50μL (for 200μL extraction volume) or 100μL of elution buffer (for larger extraction volumes).

The qPCR amplification targeted the multicopy (four to eight per parasite) 18S ribosomal RNA genes of P. falciparum (NCBI nucleotide database accession number: M19173) using primers and probes previously described by Hermsen et al. (2001) with modifications from the Oxford qPCR method [37]. The reaction mixture contained final concentrations of 1× universal PCR Master Mix, 10pmol/μL of each primer, and 10μmol of Non-Florescent Quencher with Minor Groove Binder moiety (NFQ-MGB) probe in a 50μL reaction [37]. The thermal profile consisted of 10 minutes at 95°C followed by 45 cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C and 1 minute at 60°C [37].

Table 1: Primer and Probe Sequences for P. falciparum 18S rRNA Gene Detection

| Component | Sequence (5' to 3') | Final Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Forward Primer | GTAATTGGAATGATAGGAATTTACAAGGT | 10pmol/μL |

| Reverse Primer | TCAACTACGAACGTTTTAACTGCAAC | 10pmol/μL |

| Probe | FAM- AACAATTGGAGGGCAAG-NFQ-MGB | 10μmol |

All qPCR runs included known cultured parasite standards comprising seven serial dilutions of extracted DNA run in triplicates, unknown samples in triplicate, negative controls (uninfected red blood cells) in triplicate, and three replicates of Non-Template Control (water) [37]. Standard curves were generated by plotting the mean cycle CT values versus the logarithmic parasite concentration, with parasite concentration based on relative quantification using flow cytometry data [37].

Performance Comparison: qPCR vs. Conventional Diagnostic Methods

Sensitivity and Detection Limits

The validation of the qPCR assay demonstrated exceptional sensitivity compared to conventional diagnostic methods. The lower limit of detection (LLoD) was established at 0.3 parasites/μL, with a lower limit of quantification (LLoQ) of 2.6 parasites/μL [37]. This represents a significant improvement over microscopy, which typically has a detection limit of 4-20 parasites/μL depending on the number of fields evaluated and the expertise of the microscopist [37]. Rapid diagnostic tests show even greater limitations, with sensitivities declining substantially at parasite densities below 100 parasites/μL [39].

In a 2025 study comparing diagnostic methods among pregnant women in northwest Ethiopia, microscopy exhibited a sensitivity of 73.8% in peripheral blood and 62.2% in placental blood when using multiplex qPCR as a reference standard [40]. Similarly, RDTs showed sensitivities of 67.6% in peripheral blood and 62.2% in placental blood [40]. These findings highlight the particular challenge of detecting low-density infections in pregnant women, where placental sequestration further reduces peripheral parasitemia.

Specificity and Accuracy

The validated qPCR assay achieved 100% specificity across five independent experiments, demonstrating no cross-reactivity with non-target organisms [37]. This high specificity matches that of well-performed microscopy, which maintained 100% specificity in peripheral and placental blood samples in comparative studies [40]. RDTs showed slightly lower specificity, ranging from 96.5% in peripheral blood to 98.8% in placental blood [40].

In terms of accuracy, the qPCR method demonstrated excellent extraction efficiency of >90% and close agreement with microscopy in quantitative measurements [37]. A 2019 validation study comparing microscopy versus qPCR for quantifying P. falciparum parasitemia found no significant difference in log10 parasitemia values between the two methods (mean difference 0.04, 95% CI -0.01-0.10, p=0.088) [38]. The intraclass correlation coefficient between microscopy and 18S qPCR was 0.97, indicating excellent consistency between the methods across a wide range of parasitemia values [38].

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Malaria Diagnostic Methods

| Parameter | Microscopy | RDT | qPCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit | 4-20 parasites/μL [37] | ~100 parasites/μL [39] | 0.3 parasites/μL [37] |

| Sensitivity (Peripheral Blood) | 73.8% [40] | 67.6% [40] | 100% (reference) [40] |

| Specificity (Peripheral Blood) | 100% [40] | 96.5% [40] | 100% [37] |

| Quantification Capability | Yes | No | Yes |

| Species Differentiation | Yes | Limited | Yes |

| Time to Result | 30-60 minutes | 15-20 minutes | 2-4 hours |

Linearity, Precision, and Robustness