Beyond Single Pathogens: Overcoming Sanger Sequencing Limitations in Complex Co-Infections

The accurate identification of co-infections remains a significant challenge in clinical diagnostics and therapeutic development.

Beyond Single Pathogens: Overcoming Sanger Sequencing Limitations in Complex Co-Infections

Abstract

The accurate identification of co-infections remains a significant challenge in clinical diagnostics and therapeutic development. Sanger sequencing, while a gold standard for single-pathogen detection, has inherent limitations in complex microbial communities, including low throughput and an inability to detect low-frequency variants. This article explores the critical transition from traditional Sanger sequencing to advanced metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) for comprehensive co-infection analysis. We examine the foundational principles of each technology, present methodological workflows for mNGS application, address key troubleshooting and optimization strategies and provide a comparative validation of these techniques using recent clinical data. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes evidence to guide the selection and implementation of advanced genomic tools for overcoming diagnostic bottlenecks and improving patient outcomes in polymicrobial infections.

The Co-Infection Diagnostic Challenge: Why Sanger Sequencing Falls Short

Polymicrobial infections (PMIs), characterized by the simultaneous presence of multiple microbial species at an infection site, represent a significant and often underappreciated challenge in clinical practice and infectious disease research. Worldwide, PMIs account for an estimated 20–50% of severe clinical infection cases, with biofilm-associated and device-related infections reaching 60–80% in hospitalized patients [1]. These complex infections contribute substantially to morbidity and mortality, with vulnerable populations including neonates, the elderly, and immunocompromised patients showing case-fatality rates 2-fold higher than monomicrobial infections in similar settings [1].

The clinical landscape of PMIs is diverse, encompassing diabetic foot infections, intra-abdominal infections, pneumonia, cystic fibrosis lung infections, and biofilm-associated device infections [1] [2]. The Indian subcontinent is considered a particular PMI hotspot where high comorbidities, endemic antimicrobial resistance, and underdeveloped diagnostic capacity elevate the risks of poor outcomes [1]. Understanding the prevalence, impact, and diagnostic challenges of these complex infections is essential for improving patient care and outcomes.

The Diagnostic Bottleneck: Limitations of Conventional Methods

The Culture Problem

Traditional culture-based diagnostic methods, while foundational to microbiology, exhibit critical limitations that contribute to diagnostic gaps in PMIs. These methods often suffer from low sensitivity, particularly for slow-growing, low-abundance, or unculturable pathogens, resulting in false negatives and incomplete pathogen profiles [1]. Conventional techniques typically focus on a narrow spectrum of anticipated pathogens, overlooking potentially significant co-infecting organisms and their contributions to disease pathogenesis [1].

Epidemiological data show that conventional culture-based diagnostic methods tend to detect only fast-growing, dominant microbes, often missing other slow-growing, anaerobic, or hard-to-culture organisms [1]. This incomplete detection has significant clinical implications, as the complex interplay between co-infecting microbes substantially alters disease pathophysiology, severity, and therapeutic response, heightening the risk of morbidity, prolonging hospitalization, and inflating healthcare costs [1].

The Sanger Sequencing Limitation in Co-infections Research

While Sanger sequencing has been a gold standard for genetic analysis, it faces particular challenges in the context of polymicrobial infections. The method struggles with mixed templates, which are characteristic of PMIs, leading to ambiguous results and detection failures.

Table 1: Common Sanger Sequencing Challenges in Polymicrobial Infection Research

| Challenge | Identification in Chromatogram | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Failed Reactions | Trace is messy with no discernable peaks or sequence reads "NNNNN" | Template concentration too low or poor quality DNA; bad primer | Adjust DNA concentration to 100-200ng/µL; clean up contaminants; verify primer quality [3] |

| Double Sequence/Mixed Template | Two or more peaks at same location from beginning of trace | Multiple templates in reaction; colony contamination; multiple priming sites | Ensure single colony purity; use single primer per reaction; clean up PCR products thoroughly [3] |

| Sequence Degradation | High quality data that suddenly terminates or intensity drops dramatically | Secondary structure (hairpins) in template; long stretches of G/C nucleotides | Use "difficult template" protocol with alternate dye chemistry; design primers after or toward problematic region [3] |

| Background Noise | Discernable peaks with background noise along bottom | Low signal intensity due to poor amplification; low template concentration | Optimize template concentration; ensure high primer binding efficiency; check for primer degradation [3] |

Modern Solutions: Advanced Technologies for PMI Detection

Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS)

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing offers a powerful alternative to conventional methods for PMI detection. Unlike culture-based methods, metagenomics allows for unbiased, culture-independent identification of entire microbial communities, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites within clinical samples [1]. This high-throughput approach can detect pathogens missed by conventional diagnostics and provide detailed taxonomic and resistance gene profiles [1].

A comparative study of lower respiratory tract infections demonstrated the significant advantage of mNGS over conventional culture methods in detecting co-infections. In 184 bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples, mNGS identified 66 samples with co-infections, compared to 64 by Sanger sequencing, and only 22 by conventional culture [4]. The same study showed that in 91.30% (168/184) of cases, identical results were produced by both mNGS and Sanger sequencing, validating the reliability of mNGS while highlighting its greater comprehensiveness [4].

Long-Read Sequencing Technologies

Emerging long-read sequencing technologies, such as Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), provide additional advantages for resolving complex polymicrobial infections. These technologies enable unfragmented genome assembly, which is particularly valuable for detecting co-infections and resolving complex microbial communities [5] [6].

In a study on avian haemosporidian parasites, Nanopore sequencing effectively resolved cryptic co-infections through complete mitogenome assembly, "overcoming ambiguities inherent to Sanger sequencing" [5]. The extended read lengths allow for better discrimination between similar sequences and more accurate phylogenetic resolution of closely related species within mixed infections.

Targeted Amplicon Sequencing

For many clinical applications, targeted amplicon sequencing (such as 16S rRNA gene sequencing for bacteria or ITS sequencing for fungi) provides a cost-effective middle ground between comprehensive metagenomics and targeted Sanger sequencing [7]. This approach allows for broader detection of microbial communities while maintaining deeper sequencing coverage of specific taxonomic groups.

However, this method has limitations, including the inability to differentiate prokaryotes at the species taxonomic level reliably and generally being restricted to genus-level classification [7]. The accurate taxonomic identification also depends heavily on the quality and completeness of reference databases, which often contain unidentified and/or poorly annotated sequences [7].

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why does Sanger sequencing fail to detect multiple pathogens in a mixed infection? A: Sanger sequencing operates on the principle of single-template amplification. When multiple templates are present, the sequencing reaction becomes confused, resulting in overlapping signals that appear as mixed peaks in the chromatogram. This fundamental limitation makes it unsuitable for detecting polymicrobial infections without prior separation and individual analysis of each pathogen [3].

Q: What are the key indicators of polymicrobial infection in Sanger sequencing chromatograms? A: The primary indicator is the presence of double peaks or multiple overlapping peaks at single nucleotide positions, particularly when this pattern persists throughout the sequence read. Other indicators include high background noise, sudden sequence termination, and poor-quality scores that cannot be explained by template quality alone [3].

Q: How does mNGS overcome the limitations of Sanger sequencing for PMI detection? A: mNGS sequences all DNA fragments in a sample simultaneously, then uses bioinformatics to map these fragments to reference databases, allowing identification of multiple organisms without prior targeting. This culture-independent, unbiased approach can detect unexpected pathogens, difficult-to-culture organisms, and mixed infections that would be missed by both conventional culture and Sanger sequencing [1] [4].

Q: What is the turnaround time for mNGS compared to traditional methods? A: While conventional culture can take 24-72 hours and Sanger sequencing typically requires 24-48 hours after culture isolation, mNGS can provide results within 24-48 hours total from sample receipt. Emerging technologies like CRISPR-based multiplex assays and sensitive biosensors show potential for reducing this turnaround time to under 2 hours while maintaining high accuracy (>95%) [1].

Research Reagent Solutions for Polymicrobial Infection Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Advanced PMI Detection

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits (for complex samples) | Isolation of high-quality DNA from diverse sample types | Choose kits that efficiently lyse all microbial cell types (bacterial, fungal, viral) and remove PCR inhibitors [4] |

| Multiplex PCR Primers | Amplification of multiple target sequences simultaneously | Designed to target conserved regions flanking variable areas of phylogenetic marker genes (16S, 18S, ITS) [7] |

| Metagenomic Sequencing Kits | Library preparation for NGS | Include fragmentation, adapter ligation, and amplification steps optimized for mixed microbial communities [4] |

| Bioinformatic Analysis Software | Taxonomic classification and resistance gene profiling | Platforms like IDseqTM-2, MYcrobiota provide automated analysis pipelines for NGS data [7] [4] |

| MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry | Rapid microbial identification from culture isolates | Requires pure cultures but provides rapid species identification; limited for mixed samples [4] |

Methodologies and Workflows for PMI Research

Comparative Method Workflow for Respiratory Pathogen Detection

Detailed mNGS Protocol for BALF Samples

Based on the comparative analysis of LRTI pathogens [4], the following protocol can be implemented for comprehensive PMI detection:

Sample Collection and Processing: Collect bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) using standard clinical procedures. Process samples within 2 hours of collection or store at -80°C until processing.

Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract DNA using commercial kits designed for complex samples. Include mechanical lysis steps to ensure efficient disruption of all microbial cell types.

Library Preparation: Utilize commercially available metagenomic sequencing kits (e.g., Respiratory Pathogen Multiplex Detection Kit). The process includes:

- DNA fragmentation to appropriate size (200-500bp)

- End repair and adapter ligation

- PCR amplification with barcoded primers

- Library quantification and quality control

Sequencing: Perform high-throughput sequencing using platforms such as VisionSeq 1000 or comparable systems. Aim for at least 10 million reads per sample to ensure adequate coverage of low-abundance pathogens.

Bioinformatic Analysis: Process raw sequencing data through automated analysis pipelines (e.g., IDseqTM-2) that include:

- Quality filtering and host sequence removal

- Alignment to comprehensive pathogen databases

- Taxonomic classification and abundance estimation

- Antimicrobial resistance gene detection

Result Interpretation: Integrate mNGS findings with clinical data to distinguish pathogens from colonizing organisms. Establish threshold criteria for positive identification based on read counts and clinical relevance.

Validation Framework for PMI Detection Methods

To ensure reliability of polymicrobial infection detection, implement a validation framework that includes:

Analytical Sensitivity: Determine limit of detection for each target pathogen in mixed samples using spiked controls.

Specificity Testing: Verify minimal cross-reactivity between different microbial targets in multiplex assays.

Reproducibility Assessment: Perform inter-run and intra-run replicates to establish precision metrics.

Clinical Correlation: Compare method performance against clinical presentation and outcome data.

The clinical imperative for accurately diagnosing polymicrobial infections is clear, given their significant prevalence and impact on patient outcomes. While conventional methods like culture and Sanger sequencing remain important tools in clinical microbiology, their limitations in detecting mixed infections necessitate the adoption of more comprehensive approaches like metagenomic next-generation sequencing.

The future of PMI diagnosis lies in the strategic integration of multiple technologies—leveraging the speed and specificity of targeted methods with the comprehensiveness of untargeted approaches. Emerging methods including CRISPR-based multiplex assays, artificial intelligence-based metagenomic platforms, and sensitive biosensors with point-of-care applicability show potential in reducing turnaround times to under 2 hours with accuracy exceeding 95% [1].

As these technologies continue to evolve and become more accessible, they promise to transform our approach to complex infections, enabling more targeted therapies, improved antimicrobial stewardship, and ultimately, better patient outcomes across diverse healthcare settings.

For decades, Sanger sequencing has remained the gold standard method for DNA sequencing, providing high-quality data for specific, targeted regions. In clinical microbiology, it is invaluable for identifying bacterial and fungal pathogens from clinical samples, particularly when traditional culture methods fail. This technique is highly effective for confirming the identity of a single pathogen. However, a significant limitation arises in cases of polymicrobial infections, where Sanger sequencing produces overlapping electropherogram signals that are impossible to interpret, complicating the diagnosis of co-infections [8] [9]. This technical support center is designed to help researchers overcome common experimental hurdles and understand the context in which Sanger sequencing is most effectively applied.

Troubleshooting Common Sanger Sequencing Issues

FAQ: Addressing Typical Data Quality Problems

1. My sequencing reaction failed, and the trace data contains mostly N's. What happened? A failed reaction with a messy trace and no discernable peaks is often due to issues with the template DNA [10].

- Low template concentration: This is the most common reason. Ensure your template concentration is between 100-200 ng/µL, accurately measured on an instrument like a NanoDrop [10].

- Poor DNA quality: Contaminants like salts, ethanol, or phenol can inhibit the sequencing reaction. Re-clean your DNA sample to ensure a 260/280 OD ratio of 1.8 or greater [10] [11].

- Bad primer: Verify that your primer is of high quality, not degraded, and designed to bind efficiently to a single site on your template [10].

2. The beginning of my sequence trace is noisy, but it clears up further down. Why? Noise or mixed sequence at the start of a trace is frequently caused by primer dimer formation. The primer self-hybridizes due to complementary bases on the primer itself. You can analyze your primer sequence using free online tools to ensure it is unlikely to form dimers [10].

3. Why does my high-quality sequence data suddenly stop? Sharp termination of good sequence data is usually a sign of secondary structure in the DNA template, such as hairpins formed by GC-rich regions. The sequencing polymerase cannot pass through these structures. Some core facilities offer alternate sequencing chemistries (e.g., "difficult template" protocols) that can sometimes help the polymerase read through these regions [10].

4. What are the broad, blobby peaks that appear around base 80 in my chromatogram? These are known as "dye blobs," and they represent aggregates of unincorporated dye terminators that co-migrate with DNA fragments during capillary electrophoresis. They appear as broad C or T peaks and can interfere with base calling. While cleanup protocols are designed to remove these dyes, no method is 100% effective. To avoid this issue, design primers so that your region of interest is at least 100 bases away from the primer binding site [12].

5. My sequence has good quality initially but then becomes mixed (shows double peaks). What does this mean? Double sequences can have a couple of causes [10]:

- Colony contamination: If you sequenced a bacterial colony, you may have accidentally picked more than one clone, resulting in a mixture of templates.

- Multiple priming sites: Your primer may be binding to more than one location on your template. Redesign your primer to ensure a single, unique annealing site.

Data Quality Metrics and Interpretation

Understanding the quality metrics embedded in your Sanger results is crucial for evaluating your data objectively. The following table summarizes key metrics to examine [12].

Table 1: Key Quality Metrics for Sanger Sequencing Data

| Metric | Description | Ideal Value/Range | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Value (QV) | A per-base score logarithmically related to the error probability (e.g., QV=20 means a 1% error rate). | ≥ 20 | Higher scores indicate more confident base calls. |

| Quality Score (QS) | The average QV for all assigned bases in the trace. | ≥ 40 | Indicates overall high-quality sequence. |

| Average Signal Intensity | The strength of the fluorescent signal, measured in relative fluorescence units (RFU). | > 1,000 RFU | Low values (<100) indicate noisy data; very high values (>10,000) can cause oversaturation. |

| Continuous Read Length (CRL) | The longest stretch of bases with a running average QV of 20 or higher. | > 500 bases | Common benchmark for high-quality data from plasmids or long PCR products. |

Sanger Sequencing in Clinical Research: A Protocol for Pathogen ID

The protocol below, adapted from recent clinical studies, outlines a standard methodology for identifying pathogens from clinical samples using broad-range PCR followed by Sanger sequencing [9].

Objective: To identify bacterial and fungal pathogens from culture-negative clinical samples (e.g., blood, CSF, tissue) via amplification and sequencing of conserved genomic markers.

Methodology:

DNA Extraction:

- Extract total DNA from 400 µL of clinical sample (e.g., whole blood, cerebrospinal fluid) using a commercial DNA extraction kit, such as the DNA Quick Miniprep kit.

- Determine DNA concentration and purity using a fluorescent assay (e.g., Qubit dsDNA BR assay) [9].

PCR Amplification:

- Use primers targeting conserved genomic regions:

- Reaction Setup: Use 1 µL of extracted DNA template, 2 µL of each primer (10 pmol/µL), and 47 µL of a master mix like GoTaq Green Master Mix.

- Cycling Conditions: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min; 25 cycles of [95°C for 5 s, 60°C for 15 s, 72°C for 15 s]; final extension at 72°C for 5 min [9].

Gel Electrophoresis and Purification:

- Confirm successful amplification and specificity by running 5 µL of the PCR product on a 2% agarose gel.

- Purify the correct PCR band from the gel using a Gel DNA Recovery kit [9].

Sanger Sequencing:

- Submit the purified amplicon for Sanger sequencing using the BigDye Terminator cycle sequencing kit on a platform such as the Applied Biosystems 3500 Genetic Analyzer [9].

Data Analysis:

- Visually inspect the chromatograms for quality using software like Geneious Prime.

- Compare the obtained sequence to a reference database (e.g., NCBI BLAST) for pathogen identification [9].

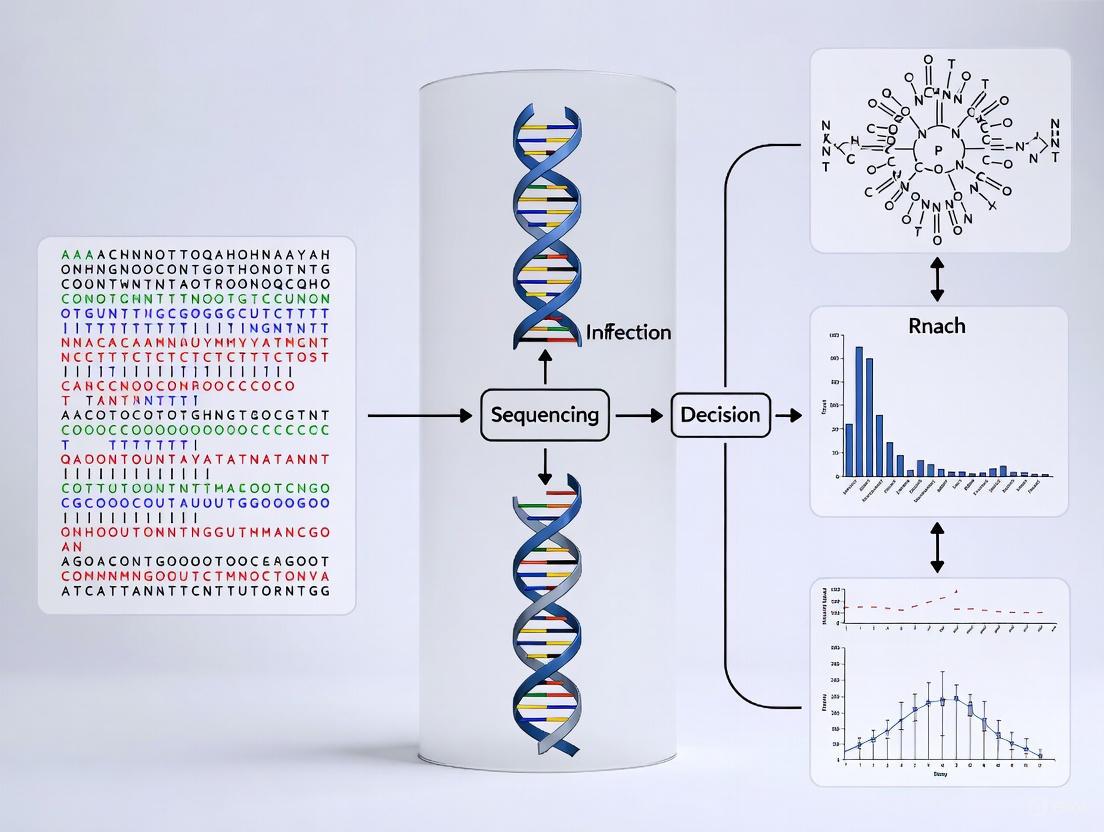

Experimental Workflow Diagram

The end-to-end process for pathogen identification via Sanger sequencing is outlined below.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Pathogen Identification via Sanger Sequencing

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Example Product |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolates total genomic DNA from various clinical sample types. | DNA Quick Miniprep Kit [9] |

| PCR Master Mix | Provides enzymes, dNTPs, and buffer for robust amplification of target genes. | GoTaq Green Master Mix [9] |

| Gel DNA Recovery Kit | Purifies the specific DNA amplicon from an agarose gel post-electrophoresis. | Zymoclean Gel DNA Recovery Kit [9] |

| Cycle Sequencing Kit | Performs the chain-termination sequencing reaction with fluorescently labeled ddNTPs. | BigDye Terminator Kit [9] |

| Reference Material | Validates the entire workflow, from extraction to sequencing, ensuring accuracy. | WHO WC-Gut RR, NML Metagenomic Controls [8] |

The Limitation in Co-infections and the Rise of NGS

The primary strength of Sanger sequencing—generating a single, high-quality sequence from a pure template—becomes its critical weakness in complex samples. When multiple pathogens are present, the PCR amplification generates a mixture of templates. Since Sanger sequencing is a bulk sequencing method, it produces a consensus signal from all amplified products, resulting in unreadable, overlapping chromatograms [8]. This makes it impossible to identify the individual species in a polymicrobial infection.

Comparative Data: Sanger vs. mNGS for Co-infections A 2025 study on Lower Respiratory Tract Infections (LRTI) directly compared the performance of Sanger sequencing, metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS), and culture, using clinical samples. The results clearly illustrate the limitation of Sanger sequencing in detecting multiple pathogens [13].

Table 3: Comparison of Pathogen Detection in Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BALF) Samples [13]

| Method | Samples with Identical Results (All 3 Methods) | Samples with Co-infections Detected | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbial Culture | 49.41% (85/172) | 22 samples | Gold standard for viable, common bacteria. |

| Sanger Sequencing | 49.41% (85/172) | 64 samples | Good for single pathogen identification; faster than culture. |

| mNGS | 49.41% (85/172) | 66 samples | Superior for detecting co-infections and rare/unculturable pathogens. |

This data shows that while Sanger sequencing is a powerful tool, its utility is confined to specific clinical questions. For complex cases where co-infections are suspected, long-read sequencing technologies like Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT) are now being implemented. ONT can sequence the entire ~1500 bp 16S rRNA gene and, crucially, resolve individual sequences from a mixed sample, providing species-level identification of all pathogens present [8] [5]. The diagram below illustrates this paradigm shift in diagnostic sequencing.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Throughput Slows Down Screening for Multiple Pathogens

Problem: My project involves screening clinical samples for a panel of 20 potential bacterial pathogens. Using Sanger sequencing serially for each target is impractically slow.

Explanation: Sanger sequencing processes only a single DNA fragment per run, making it a low-throughput technique [14]. This "one reaction, one fragment" principle is fundamentally mismatched for projects requiring analysis of multiple genes or samples simultaneously [15] [16].

Solution: Implement a targeted Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) panel. This approach sequences hundreds to thousands of genes in a single, massively parallel run [15]. The table below summarizes the throughput comparison.

Table 1: Throughput and Scalability Comparison

| Feature | Sanger Sequencing | Targeted NGS |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Scale | Single DNA fragment per run [14] | Millions of fragments simultaneously per run [15] |

| Suitability | Cost-effective for ~1-20 targets [15] | Cost-effective for high sample volumes and large gene panels (>20 targets) [15] [14] |

| Project Impact | Slow and expensive for multi-target screening | Enables high-throughput screening of multiple samples and targets [15] |

Experimental Protocol: Targeted NGS for Pathogen Detection

- DNA Extraction: Extract nucleic acids from the clinical sample (e.g., bronchoalveolar lavage fluid or sputum) using a standardized protocol [13].

- Library Preparation: Use a targeted enrichment approach, such as amplicon sequencing (e.g., Respiratory Pathogen Multiplex Detection Kit) or hybrid capture (e.g., Haloplex/SureSelect), to selectively amplify or capture the genomic regions of the target pathogens [13] [17].

- Sequencing: Load the prepared library onto a high-throughput sequencer (e.g., Illumina MiSeq or VisionSeq 1000) for massively parallel sequencing [13] [17].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Analyze the resulting sequencing data using specialized software (e.g., IDseqTM-2) by aligning reads to a pathogen database to determine the presence and abundance of microorganisms [13].

Issue 2: Inability to Detect and Resolve Polymicrobial Co-infections

Problem: I suspect my samples contain mixed infections, but the Sanger sequencing electropherogram shows overlapping signals and is unreadable.

Explanation: In a co-infection, DNA from multiple organisms is amplified together. Sanger sequencing produces a single electropherogram per reaction. When different templates are present, the signal from each base position is a mixture, resulting in overlapping peaks that are impossible to interpret accurately [8]. Its detection limit for minor variants is typically 15-20%, meaning it cannot identify pathogens that make up a small fraction of the sample [18] [19].

Solution: Utilize metagenomic NGS (mNGS) or long-read sequencing (e.g., Oxford Nanopore Technologies). These methods sequence all DNA in a sample without targeting specific organisms and assign sequences to individual pathogens bioinformatically. One study demonstrated that mNGS identified co-infections in 66 BALF samples, significantly outperforming culture (22 samples) and matching the performance of another molecular method [13]. Long-read sequencing is particularly effective for resolving the full-length 16S rRNA gene in mixed samples, overcoming ambiguities inherent to Sanger [5] [8].

Experimental Protocol: 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing with Long Reads for Polymicrobial Infections

- Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction: Lyse samples, including bead-beating for tough cell walls. Extract DNA using a validated kit [8].

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the near-full-length ~1500 bp 16S rRNA gene using universal bacterial primers.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Prepare the library using a kit like the Ligation Sequencing Kit and load it on a MinION flow cell for real-time sequencing on the GridION or PromethION platform [8].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Use a real-time basecalling software (e.g., MinKNOW). Process the data through a pipeline that performs demultiplexing, quality filtering, and taxonomic classification by comparing reads to a 16S database (e.g., SILVA) [8].

Table 2: Detection of Co-infections in Clinical Samples (BALF) [13]

| Method | Number of Samples with Co-infections Identified |

|---|---|

| Metagenomic NGS (mNGS) | 66 |

| Sanger Sequencing | 64 |

| Conventional Culture | 22 |

Issue 3: Failed Detection of Low-Frequency Variants or Minor Populations

Problem: I am trying to identify a rare, drug-resistant subpopulation present at 5% frequency, but Sanger sequencing fails to detect it.

Explanation: Sanger sequencing is an analog technique that produces a consolidated signal from all DNA molecules in a reaction. A variant present in a small fraction of the sample (<15-20%) will not produce a signal strong enough to be distinguished from background noise [18] [19]. Its low sequencing depth (each base is typically sequenced once) provides no statistical power for rare variant detection [16].

Solution: For validating known low-frequency variants, use Blocker Displacement Amplification (BDA) coupled with Sanger sequencing. For discovering unknown rare variants, deep-targeted NGS is required.

- BDA + Sanger: This method uses sequence-specific blockers to inhibit the amplification of the wild-type sequence, thereby dramatically enriching the minor variant. The enriched product can then be confirmed by Sanger sequencing, pushing its effective limit of detection down to ~0.1% [18].

- Deep-Targeted NGS: This digital method sequences each molecule thousands of times, providing high sequencing depth. This allows for the detection of low-frequency variants with high confidence, as the variant allele frequency can be quantified from the read counts [17] [19]. NGS can detect variants with a limit of detection as low as 1% [15] [14].

Experimental Protocol: Confirming Low-Frequency Variants with BDA and Sanger Sequencing [18]

- Assay Design: Use software (e.g., NGSure) to design locus-specific PCR primers and a blocker oligonucleotide that binds perfectly to the wild-type sequence, suppressing its amplification.

- Blocker Displacement Amplification (BDA): Perform qPCR on the sample DNA using the primers and blocker. The blocker is displaced when the variant template is amplified, leading to its preferential enrichment.

- Sanger Sequencing: Purify the BDA product and perform Sanger sequencing.

- Analysis: Compare the sequencing chromatogram from the BDA-enriched sample to an unenriched control. The clear appearance of a variant peak indicates a true positive low-frequency variant.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: If NGS is superior, is there any reason I should still use Sanger sequencing? Yes, Sanger sequencing remains the gold standard for confirming single-gene variants discovered by NGS due to its very high accuracy for targeted interrogation [17] [16]. It is also cost-effective and efficient for projects involving a limited number of samples and targets, such as validating plasmid constructs or diagnosing single-gene disorders [15] [14] [19].

Q2: What are the key reagent solutions for implementing a long-read sequencing workflow for co-infections? Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for 16S rRNA Long-Read Sequencing

| Item | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Characterized Reference Materials | Validates entire workflow accuracy using samples with known microbial composition [8]. | NML Metagenomic Control Materials (MCM2α/β), WHO WC-Gut RR [8]. |

| Bead-Beating Tubes | Ensures mechanical lysis of tough bacterial cell walls for efficient DNA extraction [8]. | Lysing Matrix E tubes [8]. |

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolates high-quality genomic DNA from clinical samples. | AusDiagnostics MT-Prep, GeneRead DNA FFPE Kit [8]. |

| 16S rRNA PCR Primers | Amplifies the target gene for sequencing from a wide range of bacteria. | Universal bacterial primers targeting ~1500 bp region [8]. |

| Long-Red Sequencing Kit | Prepares the amplified DNA library for loading onto the sequencer. | ONT Ligation Sequencing Kit [8]. |

| Bioinformatic Pipeline | Performs basecalling, demultiplexing, quality filtering, and taxonomic classification. | MinKNOW for basecalling, alignment to SILVA database [8]. |

Q3: My Sanger sequencing of a co-infection sample failed. Could the problem be my DNA extraction method? Possibly. The presence of inhibitors from the clinical sample or inefficient lysis of certain pathogen types (e.g., gram-positive bacteria with tough cell walls) can lead to PCR amplification failure, which will result in a failed Sanger sequence. Incorporating bead-beating during DNA extraction and using internal controls can help mitigate this issue [8].

Q4: Are the limitations of Sanger sequencing primarily due to cost or fundamental technology? The limitations are fundamentally technological. The core chemistry of processing one fragment at a time inherently creates bottlenecks in throughput, detection range, and sensitivity for complex mixtures [15] [14]. While cost is a factor for large projects, it is a consequence of this underlying low-throughput design.

Sanger sequencing remains the gold standard for validating sequencing results due to its high single-base accuracy and long read lengths of 500-800 bp [20]. However, in the critical field of co-infections research—where samples often contain multiple pathogenic organisms—researchers frequently encounter two persistent technical bottlenecks: mixed template sequences and excessive background noise. These artifacts compromise data quality, leading to ambiguous base calls and unreliable sequences that can hinder accurate pathogen identification. This technical support center guide provides targeted troubleshooting protocols to overcome these specific challenges, enabling robust Sanger sequencing data from complex clinical and environmental samples.

FAQ: Addressing Mixed Template Sequences

What causes mixed sequences (multiple peaks) in my chromatograms?

Mixed sequences appear as overlapping peaks of two or more colors at the same position in the chromatogram, indicating that multiple DNA templates are being sequenced simultaneously [21]. In co-infections research, this could genuinely reflect biological reality, but more often stems from technical artifacts.

- Colony Contamination ("Double Picking"): Accidentally picking two or more bacterial colonies during culture leads to sequencing multiple DNA clones [10].

- PCR Primer Contamination: Residual PCR primers from amplification reactions not being thoroughly cleaned up can act as unintended sequencing primers [10] [21].

- Multiple Priming Sites: The sequencing primer binds to more than one location on the template DNA, generating extension products from different sites [10] [22].

- Heterogeneous PCR Products: The initial PCR amplification may contain multiple products of similar size, which are then co-sequenced [21].

- True Biological Co-infections: The sample genuinely contains two or more different pathogen strains or species [13] [5].

How can I resolve mixed template issues?

Table 1: Troubleshooting Steps for Mixed Template Sequences

| Problem Cause | Diagnostic Step | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Colony Contamination | Inspect original colony plates for closely spaced colonies. | Re-isolate single, well-spaced colonies and prepare new plasmid DNA [10] [21]. |

| Multiple PCR Products | Run PCR product on agarose gel. | Gel-purify the single correct band before sequencing [22] [21]. |

| Residual PCR Primers | Review PCR clean-up protocol. | Implement a rigorous PCR purification protocol using validated kits [10] [21]. |

| Multiple Priming Sites | In silico analysis of primer binding sites. | Redesign sequencing primer to ensure a single, unique binding site [10] [22]. |

| Low Annealing Temperature | Check sequencing reaction thermal cycler protocol. | Increase the annealing temperature in the cycle sequencing reaction to improve specificity [21]. |

Experimental Protocol: Verification of Single Template

To confirm a single template source before sequencing:

- Gel Electrophoresis: After PCR amplification, run the product on a high-percentage agarose gel (e.g., 2-3%). Look for a single, sharp band of the expected size. The presence of multiple or smeared bands indicates a heterogeneous product [21].

- PCR Purification: Use a spin-column-based PCR purification kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. This removes excess salts, dNTPs, and, crucially, the original PCR primers [10].

- Quantification: Accurately measure the DNA concentration using a fluorometer (e.g., Qubit) or spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop). Ensure the 260/280 ratio is ~1.8 for pure DNA [10] [23].

Diagram: A workflow for diagnosing and resolving mixed template sequences in Sanger sequencing.

FAQ: Managing Background Noise

What generates background noise in my sequencing traces?

Background noise manifests as smaller, undefined peaks beneath the primary sequencing peaks, creating a "noisy" baseline that interferes with accurate base-calling [23]. This noise can be categorized and its causes are specific.

- Baseline Noise: Low-intensity, random peaks often caused by poor template quality, contaminants, or instrument issues [23] [22].

- Dye Artifacts ("Dye Blobs"): Broad, unidentified peaks, often around 70-80 bases, caused by unincorporated fluorescent dye terminators that were not fully removed during cleanup [10] [12].

- N+1/N-1 Peaks: Smaller peaks immediately adjacent to the main peak, resulting from incomplete termination by the ddNTPs during the extension reaction [23].

- Weak Signals: Low, poorly resolved peaks due to insufficient template DNA, poor primer binding, or degraded reagents [10] [23].

- Polymerase Slippage: Noise following a homopolymer region (e.g., a run of "AAAAA") due to the polymerase enzyme dissociating and re-associating incorrectly [10].

How can I minimize background noise?

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Background Noise

| Noise Type | Primary Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Baseline Noise | Poor DNA quality/purity; multiple priming sites. | Re-purify DNA; ensure 260/280 ratio ≥1.8; redesign primer for unique site [23] [22]. |

| Dye Blobs | Inefficient cleanup of sequencing reaction. | Optimize cleanup protocol; ensure proper vortexing if using magnetic beads; avoid ethanol over-concentration [22]. |

| N+1/N-1 Peaks | Incomplete termination in cycle sequencing. | Use fresh, high-quality BigDye terminator mix; optimize ddNTP concentration [23]. |

| Weak Signals | Low template concentration; degraded primer. | Quantify DNA accurately with fluorometer; use 50-300 ng plasmid DNA; store primers properly [10] [22]. |

| Noise after Homopolymers | Polymerase slippage on repetitive sequences. | Sequence from the opposite strand; use a primer located just after the repetitive region [10]. |

Experimental Protocol: Template Purification for Noise Reduction

A critical step for minimizing noise is using high-quality, pure DNA template.

- Extraction: Use a spin-column-based DNA extraction kit tailored to your sample type (e.g., plasmid, tissue, blood) [23].

- Quality Assessment:

- Use a NanoDrop or similar spectrophotometer. Acceptable purity ratios are 260/280 ≈ 1.8 and 260/230 ≈ 2.0-2.2.

- Run agarose gel electrophoresis to check for DNA integrity (sharp band, no smearing).

- Post-PCR Purification: Always clean up PCR products before sequencing. Use a reliable PCR purification kit to remove enzymes, salts, and excess primers. This step alone can reduce background noise by 80-85% [23].

- Storage: Store purified DNA and primers at -20°C or -80°C to maintain stability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Troubleshooting Sanger Sequencing

| Reagent/Material | Function & Role in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Used in initial PCR; reduces amplification errors and non-specific products that cause noise [23]. |

| Spin-Column PCR Purification Kits | Removes residual primers, dNTPs, and salts from PCR products to prevent mixed templates and dye blobs [10] [23]. |

| BigDye Terminator Kit | The core chemistry for cycle sequencing. Use fresh, in-date reagents for optimal termination and signal strength [22]. |

| BigDye XTerminator Purification Kit | Magnetic bead-based cleanup specifically for BigDye reactions; highly effective at removing unincorporated dyes to reduce noise [22]. |

| Control DNA (e.g., pGEM-pGEM Control) | A known, high-quality DNA template and primer provided in kits to distinguish sample problems from reagent/instrument failures [22]. |

| Hi-Di Formamide | Used to resuspend purified sequencing products before capillary electrophoresis; ensures proper sample denaturation and migration [22]. |

Advanced Data Analysis & Validation

How do I interpret quality metrics in my sequencing data?

Modern sequencing analysis software provides quantitative metrics to objectively assess data quality [12].

- Quality Value (QV): A per-base score where QV = -10 × log(error probability). A QV of 20 indicates a 1% base-calling error rate. Actionable Threshold: Bases with QV < 20 should be visually inspected; those with QV < 10 are often called as 'N' and are unreliable [12].

- Quality Score (QS): The average QV for the entire trace. Interpretation: QS ≥ 40 indicates high-quality data; QS ~30 requires careful review; QS < 20 indicates poor, unreliable data [12].

- Signal Intensity: Measured in Relative Fluorescence Units (RFU). Optimal Range: Peaks between 1,000 and 8,000 RFU. Intensity < 100 RFU is too weak and noisy; > 10,000 RFU can cause sensor oversaturation and "spectral pull-up" [12].

A Framework for Validating Sequences in Co-infections Research

When Sanger sequencing indicates a potential co-infection, a rigorous validation workflow is essential to distinguish technical artifacts from biological reality.

Diagram: A decision framework for validating potential co-infections after initial Sanger sequencing results.

Validation Protocol Using Sanger Sequencing:

- Bidirectional Sequencing: Always sequence the same genomic region from both forward and reverse primers. True mutations or mixed bases will appear in both directions, while artifacts often will not.

- Independent PCR Amplification: Repeat the entire process, starting from a new biological sample or DNA aliquot, through independent PCR and sequencing. This controls for errors introduced in a single reaction.

- Sub-cloning: For persistent mixed signals, clone the PCR product into a plasmid vector. Then, sequence multiple individual colonies. If the mixture is a technical artifact, individual clones will show pure sequences. If it's a true co-infection, different clones will show distinct, pure sequences corresponding to the different strains/species [5].

Sanger sequencing remains an indispensable tool for life science research, but its limitations in analyzing complex, mixed samples must be acknowledged and managed. The troubleshooting guides and FAQs presented here provide a systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving the two most common technical bottlenecks—mixed templates and background noise. By implementing rigorous sample preparation protocols, understanding data quality metrics, and employing confirmatory experimental workflows, researchers can generate reliable, high-quality Sanger data. For the most complex co-infections where Sanger reaches its limits, integrating it with orthogonal methods like mNGS or Nanopore sequencing provides a powerful strategy to validate findings and ensure research integrity [13] [5].

Sanger sequencing has long been the gold standard for DNA sequencing in clinical and research settings due to its high accuracy and reliability [24]. However, a significant diagnostic limitation emerges when analyzing samples containing mixed populations of microorganisms, as occurs in co-infections. This technical support guide examines the specific scenarios where Sanger sequencing fails to detect co-infections, explores the underlying technical mechanisms for these failures, and presents advanced methodological solutions to overcome these limitations in research and drug development settings.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why can't Sanger sequencing detect multiple pathogen strains in a single sample?

Sanger sequencing operates on the principle of bulk analysis, where signals from all DNA molecules in a sample are averaged during the sequencing reaction. When multiple pathogen strains are present, their genetic variations at the same nucleotide position produce overlapping fluorescence signals that the sequencing software cannot resolve. This results in ambiguous base calling, often appearing as overlapping peaks in the chromatogram that are typically misinterpreted as noise or sequencing artifacts rather than true biological mixtures [24] [12].

2. What is the minimum variant frequency required for reliable detection by Sanger sequencing?

Sanger sequencing reliably detects genetic variants only when they are present as the dominant population in a sample. The established detection threshold is approximately 15-20% of the total genetic material [25]. Variants present below this threshold typically fail to generate sufficient signal strength for detection. Next-generation sequencing (NGS), in contrast, can detect variants at frequencies as low as 1-5%, providing significantly higher sensitivity for identifying minority variants in mixed infections [25].

3. In which specific research scenarios is this limitation most problematic?

The co-infection detection gap poses significant challenges in several critical research areas:

- Antimicrobial resistance studies: Where emergent resistant subpopulations may be present below the detection threshold [25]

- Viral quasispecies analysis: Particularly in HIV and hepatitis C research, where heterogeneous viral populations are common [25]

- Complex infection models: Including polymicrobial biofilms and multi-pathogen infections [26] [27]

- Vaccine efficacy research: Where monitoring for escape mutants requires sensitive variant detection [26]

4. What are the primary technical factors limiting mixed infection detection?

Three key technical factors constrain detection sensitivity:

- Signal averaging: Fluorescence signals from all templates are combined during capillary electrophoresis

- Base-calling algorithms: Designed to call a single base per position, disregarding mixed signals

- Template concentration bias: PCR amplification preferentially amplifies dominant templates, further reducing minority variant signals [3] [22] [24]

Technical Limitations and Detection Thresholds

Table 1: Comparative Detection Thresholds of Sequencing Technologies

| Technology | Variant Detection Threshold | Optimal Read Length | Co-infection Detection Capability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sanger Sequencing | 15-20% | 500-1000 bp | Limited to dominant strain |

| Pyrosequencing | 5-10% | 100-500 bp | Moderate for major subpopulations |

| Illumina NGS | 1-5% | 50-300 bp | High sensitivity for mixed infections |

| Ion Torrent NGS | 1-5% | 200-400 bp | High sensitivity for mixed infections |

| PacBio SMRT | 0.1-1% | 10,000-50,000 bp | Excellent for haplotype resolution |

| Oxford Nanopore | 0.1-1% | 10,000-100,000 bp | Excellent for full-length variant assembly |

Table 2: Impact of Detection Thresholds on HIV Drug Resistance Monitoring

| Detection Threshold | Reported PDR Prevalence | Ability to Predict Virologic Failure | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1% | 29.74% | Highest sensitivity | Research setting |

| 2% | 22.43% | High sensitivity | Optimal for clinical detection |

| 5% | 15.47% | Moderate improvement | Better than Sanger |

| 10% | 12.95% | Slight improvement | Limited advantage |

| 20% (Sanger) | 11.08% | Baseline | Standard reference |

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying Co-infection Detection Failures

Problem: Mixed Chromatogram Signals

How to Identify: Double or overlapping peaks at multiple positions throughout the sequencing trace, particularly when the overall sequence quality metrics appear normal [3] [24]. The quality scores (QV) for these positions are typically low (<20), and the base-calling software may assign "N" instead of a specific base [12].

Underlying Cause: The presence of multiple genetic templates with sequence variations at the same position. This occurs during co-infections with genetically distinct strains of the same pathogen or infections with multiple pathogen species [26] [5].

Solutions:

- Employ nested PCR with specific primers to amplify and separate individual strains

- Implement clonal amplification by subcloning PCR products before sequencing

- Transition to NGS platforms that can sequence individual molecules, preserving variant information [26] [25]

Problem: Abrupt Sequence Quality Deterioration

How to Identify: High-quality sequencing data that suddenly becomes noisy or terminates prematurely, particularly in regions with homopolymer repeats or secondary structures [3].

Underlying Cause: Polymerase slippage on repetitive regions or secondary structures in mixed templates, leading to heterogeneous fragment populations that disrupt electrophoretic separation [3] [22].

Solutions:

- Use specialized polymerases designed for difficult templates

- Optimize reaction conditions with additives like DMSO or betaine

- Implement long-read sequencing technologies (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) that better handle repetitive regions [5] [28]

Problem: Selective Template Amplification

How to Identify: Consistent failure to detect known minority variants despite their confirmed presence through alternative methods.

Underlying Cause: PCR amplification bias during template preparation, where primers preferentially amplify certain templates due to sequence mismatches or secondary structures [24].

Solutions:

- Redesign primers to target conserved regions across potential variants

- Use high-fidelity, proofreading polymerases with minimal amplification bias

- Implement metagenomic sequencing without targeted amplification [27] [28]

Experimental Protocols for Overcoming Detection Limitations

Protocol 1: Clonal Separation for Strain Discrimination

Purpose: To physically separate mixed templates before sequencing to enable individual characterization of each strain in a co-infection.

Materials:

- TOPO TA Cloning Kit or equivalent

- Competent E. coli cells

- Plasmid purification kit

- Strain-specific growth media

Procedure:

- Amplify target gene using standard PCR conditions

- Ligate PCR products into cloning vector following manufacturer's protocol

- Transform competent E. coli cells and plate on selective media

- Pick individual colonies (minimum of 20-50) and culture overnight

- Purify plasmid DNA from each culture

- Sequence inserts using standard Sanger sequencing

- Analyze sequences to identify distinct strains [26]

Protocol 2: NGS-Based Co-infection Analysis

Purpose: To comprehensively characterize all strains present in a co-infction without prior separation.

Materials:

- Illumina MiSeq or comparable NGS platform

- DNA library preparation kit

- Bioinformatic analysis software (IDseq, BLAST)

Procedure:

- Extract total DNA/RNA from clinical sample

- Prepare sequencing library following manufacturer's protocol

- Sequence using appropriate NGS platform

- Process raw reads through quality control filters

- Perform de novo assembly of contigs

- Map reads to reference sequences

- Identify strain-specific variations using variant calling algorithms [26] [13]

Diagnostic Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Co-infection Detection Workflow Comparison

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Advanced Co-infection Studies

| Reagent/Kit | Application | Function in Co-infection Research |

|---|---|---|

| SepsiTest UVD | Direct pathogen DNA isolation | Selective removal of human DNA to enhance microbial signal in mixed infections [27] |

| BigDye Terminator v3.1 | Cycle sequencing | Fluorescent labeling for Sanger sequencing; optimized for difficult templates [22] |

| Micro-Dx Platform | Automated DNA extraction | Standardized processing for culture-independent diagnosis [27] |

| Ion Torrent SS | Semiconductor sequencing | Rapid detection of multiple pathogens without cultivation [28] |

| Vision Respiratory Pathogen Kit | Targeted NGS | Multiplex detection of common respiratory pathogens in co-infections [13] |

| PacBio SMRTbell | Long-read sequencing | Full-length haplotype resolution for strain discrimination [5] [28] |

Advanced Methodologies for Co-infection Resolution

Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS)

Metagenomic NGS represents a paradigm shift in co-infection detection by eliminating the need for targeted amplification. In comparative studies of lower respiratory tract infections, mNGS demonstrated significantly enhanced detection capabilities for co-infections, identifying 66 co-infected samples in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid compared to 22 detected by culture methods [13]. The unbiased nature of mNGS allows for the detection of unexpected pathogens, fastidious organisms, and novel infectious agents that would be missed by hypothesis-driven testing approaches.

Long-Read Sequencing Technologies

Third-generation sequencing platforms from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore Technologies enable complete resolution of co-infections through ultra-long reads that preserve haplotype information. A study on avian haemosporidian parasites demonstrated that nanopore sequencing successfully resolved cryptic co-infections that were ambiguous by Sanger sequencing, enabling the identification of two novel Haemoproteus lineages and one Plasmodium lineage in a single host [5]. The assembly of unfragmented mitogenomes through long-read sequencing overcomes the phase ambiguity inherent in short-read technologies.

The diagnostic gap in Sanger sequencing's ability to detect co-infections represents a significant limitation in both research and clinical settings. As demonstrated through the technical guidelines presented here, understanding these limitations is the first step toward implementing appropriate methodological solutions. The integration of NGS technologies, particularly metagenomic and long-read sequencing approaches, provides researchers with powerful tools to overcome these challenges and gain a more comprehensive understanding of complex microbial communities in co-infection scenarios. For research and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate sequencing strategy based on the specific requirements of variant detection sensitivity, throughput, and analytical depth is crucial for successful characterization of co-infections.

Implementing Metagenomic NGS: A Practical Framework for Co-Infection Detection

Untargeted, hypothesis-free sequencing represents a paradigm shift in pathogen detection. Unlike traditional methods that require pre-defined suspects, these approaches use next-generation sequencing (NGS) to comprehensively analyze all nucleic acids in a sample. This guide explores the principles of these powerful methods and provides practical support for researchers overcoming the limitations of Sanger sequencing in co-infections research.

Core Principles: Why Move Beyond Targeted Methods?

The Power of an Unbiased Approach

Hypothesis-free pathogen detection relies on metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS), which uses shotgun sequencing to randomly sample DNA and RNA from clinical specimens. This allows for broad identification of known, unexpected, and even novel pathogens without prior suspicion [29].

Key Advantages Over Conventional Testing

- Unbiased Sampling: Detects nearly any organism, leading to a dramatic paradigm shift in microbial diagnostic testing [29].

- Discovery Capability: Enables identification of unexpected pathogens or discovery of new organisms [29] [13].

- Comprehensive Genomic Data: Provides auxiliary information for evolutionary tracing, strain identification, and prediction of drug resistance [29].

- Solving Co-infections: Particularly valuable for detecting multiple pathogens in a single sample, a scenario where Sanger sequencing often fails [13] [30].

The Critical Limitation of Sanger Sequencing in Co-infections

Sanger sequencing, while a gold standard for single targets, encounters significant limitations in complex samples:

"In mixed cultures or samples with poly-microbial contamination, mixed sequences occur in Sanger sequencing that do not allow reliable pathogen identification" [30].

This fundamental limitation is precisely where mNGS excels, as it can independently sequence thousands to billions of DNA fragments simultaneously [29].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents for Untargeted Sequencing Workflows

| Item | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit | Recovers DNA/RNA from diverse sample types (blood, tissue, BALF). | Select kits designed to provide long, intact strands (>1,500 bp) for optimal sequencing [31]. |

| PCR Reagents | Amplifies specific targets or whole genomes for library preparation. | Use high-fidelity polymerases. Hot-Start PCR Kits reduce non-specific amplification [32]. |

| qPCR Master Mix | Quantifies nucleic acid concentration pre-sequencing; verifies findings. | Essential for confirming template quality and quantity before library prep [33]. |

| Library Preparation Kit | Fragments, repairs, and adapts DNA for sequencing on a specific platform. | Platform-specific (e.g., Illumina, Ion Torrent, Nanopore). Critical for efficient sequencing. |

| Sequencing Primers | Initiates the sequencing reaction. | Should be designed to bind at least 60-100 bp away from key regions of interest for optimal Sanger results [12]. |

Workflow & Technology Comparison

The following diagram illustrates the core logical relationship and workflow differences between the targeted Sanger approach and the untargeted mNGS approach for pathogen detection.

Performance Data: mNGS vs. Conventional Methods

Recent studies directly compare the performance of mNGS against standard microbiological culture, using Sanger sequencing as a reference.

Table: Detection performance of mNGS versus culture in respiratory samples [13]

| Sample Type | Total Samples | Identical Results (All Methods) | mNGS & Sanger Results Match | More Pathogens Detected by mNGS | Co-infections Identified (mNGS vs. Culture) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sputum | 322 | 52.05% (165/317) | 88.20% (284/322) | 9% (29/322) | Not Specified |

| Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid (BALF) | 184 | 49.41% (85/172) | 91.30% (168/184) | 7.61% (14/184) | 66 (mNGS) vs. 22 (Culture) |

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Is metagenomic sequencing truly "hypothesis-free"?

While often described as "unbiased" or "agnostic," mNGS is not entirely free of underlying assumptions. The experiment depends on hypotheses dictated by the sequencing technology and bioinformatic analysis. For instance, it is inherently biased towards detecting organisms whose nucleic acids can be recovered and whose sequences are present in reference databases [34] [35]. It is more accurate to consider it a "hypothesis-generating" tool that is unbiased by prior pathophysiological assumptions.

Q2: For common lower respiratory infections, is mNGS always necessary?

Not always. For common bacterial pathogens susceptible to culture, conventional methods are often sufficient and more cost-effective. However, mNGS provides significant advantages in detecting rare, fastidious, or difficult-to-culture pathogens and is particularly useful for identifying co-infections, as demonstrated by its ability to find nearly three times more co-infections in BALF samples than culture [13].

Q3: What is the biggest challenge when starting with mNGS?

A key challenge is that microbial nucleic acids in most patient samples are dominated by human host background, often constituting >99% of the sequenced reads. This drastically limits the analytical sensitivity for pathogen detection and requires sufficient sequencing depth to ensure adequate microbial genome coverage [29].

Q4: My Sanger sequencing results in unreadable chromatograms for poly-microbial samples. What is the solution?

This is a classic limitation of Sanger sequencing. When primers amplify multiple different targets, the resulting chromatogram contains overlapping signals from mixed sequences, making it uninterpretable [30]. The solution is to transition to an mNGS approach, which sequences individual DNA fragments independently, thereby resolving the components of a co-infection.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Pathogen Signal in mNGS Data (High Host Background)

- Problem: The vast majority of sequencing reads are from the host, masking the pathogenic signal.

- Potential Solutions:

- Increase Sequencing Depth: Sequence more deeply to increase the likelihood of capturing rare microbial reads.

- Host Depletion: Employ probe-based or enzymatic methods to selectively remove human host DNA/RNA before library preparation.

- Sample Enrichment: If a specific type of pathogen is suspected (e.g., viruses), use targeted enrichment panels to pull down relevant sequences from the complex mixture.

Issue 2: Interpreting Relevance of Detected Microbes

- Problem: mNGS detects microbial sequences, but not all are clinically pathogenic. Distinguishing contamination, colonization, and true infection is difficult.

- Potential Solutions:

- Use Quantitative Thresholds: Establish minimum thresholds for reporting, such as Reads Per Million (RPM). For example, one study used an RPM threshold of 1 for most bacteria, and a more sensitive 0.1 RPM for tricky pathogens like Mycoplasma pneumoniae and fungi [13].

- Statistical Outliers: Compare the abundance of a suspected pathogen across all samples in a run. One protocol considered a pathogen relevant if its read count was greater than the 4th standard deviation above the mean of all samples [30].

- Correlate with Clinical Data: Always integrate mNGS findings with patient symptoms, other lab results, and imaging.

Issue 3: Inaccurate Base Calls in Sanger Sequencing (For Validation)

- Problem: Even when used for validation, Sanger sequencing can produce poor-quality data, leading to incorrect base calls.

- Potential Solutions:

- Visualize Chromatograms: Always inspect the chromatogram trace file; do not rely solely on the text sequence. Look for sharp, well-spaced peaks [12].

- Check Quality Metrics: Use embedded quality values (QV). A QV of 20 indicates a 1% error probability. Bases with QV < 10 should be considered unreliable [12].

- Optimize Template: Ensure the DNA template submitted for Sanger sequencing is pure, concentrated, and represents a single, specific amplicon. Avoid degenerate primers and always purify PCR products to remove enzymes and unused nucleotides [31].

Accurate pathogen identification is fundamental to infectious disease research and therapeutic development. For decades, Sanger sequencing has served as the gold standard for confirming the identity of microbial isolates, providing high accuracy for single-pathogen detection [36]. However, a significant limitation arises in the context of polymicrobial or co-infections, where multiple pathogens coexist within a single sample. Sanger sequencing struggles to resolve mixed chromatograms resulting from multiple templates, often leading to uninterpretable data and missed secondary pathogens [5]. This technical brief compares the established Sanger workflow with the emerging paradigm of metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS), focusing on their application in co-infections research. We detail protocols, troubleshooting guides, and reagent solutions to empower researchers in selecting the appropriate methodological framework for their investigative needs.

Workflow Comparison: Sanger Sequencing vs. mNGS

The following diagrams and tables summarize the core procedural and performance differences between the two methodologies.

Visual Workflow Comparison

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental differences in process and complexity between Sanger sequencing and mNGS.

Performance Characteristics in Pathogen Detection

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Sanger Sequencing and mNGS Performance

| Parameter | Sanger Sequencing | Metagenomic NGS (mNGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Targeted sequencing of a single, specific PCR amplicon [36] | Untargeted, shotgun sequencing of all nucleic acids in a sample [37] |

| Optimal Use Case | Confirming identity of a single, isolated pathogen | Comprehensive detection of all potential pathogens (bacteria, viruses, fungi, parasites) without prior suspicion [37] |

| Throughput | One target per reaction | Thousands to millions of sequences in parallel [37] |

| Typical Turnaround Time | 1-2 days | 1-3 days [38] |

| Ability to Detect Co-infections | Limited; fails with mixed templates [5] | High; readily identifies multiple pathogens [13] [39] |

| Sensitivity in Clinical Samples | Dependent on prior culture and target concentration | High; can detect low-abundance and unculturable pathogens [13] [38] |

| Quantitative Data | No | Semi-quantitative (e.g., Reads Per Million - RPM) [13] |

| Cost per Sample | Low | High |

Table 2: Empirical Detection Rates in Lower Respiratory Tract Infection Studies

| Method | Sample Type | Positive Detection Rate | Co-infection Identification | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanger Sequencing | 322 Sputum Samples | Used as reference method in study [13] | Limited by design | 88.2% concordance with mNGS in sputa; effective for confirming single targets [13] |

| mNGS | 322 Sputum Samples | 88.20% (284/322) [13] | Significant advantage | Detected more species than Sanger in 9% of cases [13] |

| mNGS | 184 BALF Samples | 91.30% (168/184) [13] | Significant advantage | Identified co-infections in 66 samples, vs. 64 by Sanger and 22 by culture [13] |

| mNGS | 165 LRTI Patients (Multiple Specimens) | 86.7% (143/165) [39] | Significant advantage | Detected 29 kinds of pathogens missed by traditional methods, including viruses and anaerobic bacteria [39] |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My Sanger sequencing results for a directly processed clinical sample show mixed base calls and noisy chromatograms. What is the likely cause and solution?

A: This is a classic indicator of a co-infection or polymicrobial sample [5]. Sanger sequencing reactions are designed for a single, pure DNA template. When multiple templates with variations in the target region are present, the overlapping signals create uninterpretable chromatograms.

- Solution A (Sanger Path): Isolate individual pathogens by subculturing the sample on selective media to obtain pure colonies, then sequence each isolate separately. This is time-consuming and may miss unculturable organisms.

- Solution B (mNGS Path): Switch to an mNGS workflow. mNGS is inherently designed to handle mixed templates and will generate individual sequence reads that can be sorted bioinformatically to identify each distinct pathogen present [13] [5].

Q2: For mNGS, how do I determine if a detected microbe is a true pathogen versus background contamination or colonization?

A: This is a critical challenge in interpreting mNGS data. A multifaceted approach is required:

- Use Negative Controls: Include extraction and library preparation controls in every batch. Any pathogen found in both the sample and the control is likely contamination.

- Apply Quantitative Thresholds: Use validated, pathogen-specific thresholds. For example, one study used RPM ≥ 1 for most bacteria and RPM ≥ 0.1 for fungi like Aspergillus fumigatus to define a positive result [13].

- Correlate with Clinical Data: Integrate findings with patient symptoms, immune status, and other lab results (e.g., white blood cell count, procalcitonin). The clinical picture is essential for determining significance.

Q3: The high human host background in my mNGS data from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) is limiting pathogen detection sensitivity. How can I improve this?

A: Host nucleic acid is a major confounder in mNGS. Several strategies can mitigate this:

- Sample Pre-treatment: Use commercial host DNA depletion kits (e.g., MolYsis Basic5) which selectively degrade human DNA while leaving microbial cells intact [40].

- Probe-Based Enrichment: Implement targeted enrichment panels using probes that hybridize to and capture pathogen nucleic acids prior to sequencing. One study showed this can boost unique pathogen reads by 34.6-fold and significantly improve genome coverage, especially for viruses [41] [42].

- Specimen Selection: BALF generally has a lower host background compared to sputum.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Kits for Sanger and mNGS Workflows

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Silica Column-based DNA Extraction Kits (e.g., TIANamp Micro DNA Kit [38]) | Extracts nucleic acids from various sample types. | Fundamental for both Sanger and mNGS. For mNGS, ensures broad lysis of diverse microbes. |

| BigDye Terminator Kit | The core chemistry for Sanger cycle sequencing, using fluorescently labeled ddNTPs [36]. | Essential for the Sanger workflow. Requires post-reaction clean-up to remove unincorporated dyes. |

| VAHTS Universal Plus DNA Library Prep Kit for MGI [40] | Prepares DNA fragments for high-throughput sequencing by adding platform-specific adapters. | A key reagent for mNGS library construction on BGISEQ platforms. |

| MolYsis Basic5 [40] | Selectively depletes host (human) DNA from samples prior to extraction. | Critical for improving mNGS sensitivity in samples with high host background, like BALF. |

| Respiratory Pathogen Probe Panels [41] | Biotinylated RNA probes that enrich for targeted pathogen sequences in a library. | Used post-library preparation to significantly increase sensitivity for a pre-defined set of respiratory pathogens. |

| Magnetic Pathogen DNA/RNA Kit [40] | Extracts both DNA and RNA simultaneously. | Necessary for comprehensive mNGS that aims to detect all pathogen types, including RNA viruses. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Standard Sanger Sequencing Protocol for Bacterial Identification

This protocol is adapted for identifying a bacterial isolate from a pure culture, typically targeting the 16S rRNA gene [36].

DNA Template Preparation:

- Extract genomic DNA from a pure bacterial colony using a silica column-based kit.

- Quantify DNA using a spectrophotometer (e.g., Nanodrop) or fluorometer. For plasmid templates, a concentration of ~50 ng/μL is recommended; for purified PCR products, ~1-6 ng/μL is sufficient depending on amplicon size [43].

PCR Amplification:

- Set up a PCR reaction with primers targeting the 16S rRNA gene (e.g., 27F and 1492R). Use a high-fidelity PCR master mix.

- Thermal Cycling: Initial denaturation (95°C for 2 min); 35 cycles of: Denaturation (95°C for 30s), Annealing (55°C for 30s), Extension (72°C for 90s); Final extension (72°C for 5 min) [36].

PCR Clean-up:

- Purify the PCR product to remove primers, enzymes, and unincorporated nucleotides. Use a spin column-based purification kit or an enzymatic clean-up method (e.g., ExoSAP-IT) [36].

Cycle Sequencing Reaction:

- Set up the Sanger sequencing reaction using the purified PCR product as template. The reaction includes:

- Template DNA (~1-10 ng)

- Sequencing primer (5 μM, 5 μL)

- BigDye Terminator ready reaction mix

- Sequencing buffer

- Thermal Cycling: Rapid thermal ramp to 96°C; 25 cycles of: Denaturation (96°C for 10s), Annealing (50°C for 5s), Extension (60°C for 4 min) [36].

- Set up the Sanger sequencing reaction using the purified PCR product as template. The reaction includes:

Cycle Sequencing Clean-up:

- Remove unincorporated dye terminators using a spin column, ethanol/EDTA precipitation, or a magnetic bead-based method [36].

Capillary Electrophoresis:

- Load the purified sequencing reaction onto a genetic analyzer (e.g., SeqStudio). The instrument will separate the fragments by size and detect the fluorescent dye as each fragment passes a laser.

Data Analysis:

- The instrument software generates a chromatogram (.ab1 file). Analyze the sequence quality and perform a BLAST search against a public database (e.g., NCBI BLAST) for species identification [36].

Standard mNGS Wet-Lab Protocol for BALF Samples

This protocol outlines the core steps for processing a BALF sample for DNA-based mNGS [13] [40] [38].

Sample Collection and Inactivation:

- Collect BALF aseptically and transport on ice.

- Inactivate: Heat sample at 80°C for 10 minutes to ensure biosafety [38].

Host DNA Depletion (Optional but Recommended):

- Treat the sample with a host depletion kit (e.g., MolYsis Basic5) according to the manufacturer's instructions to increase the relative proportion of microbial nucleic acids [40].

Total Nucleic Acid Extraction:

Library Preparation:

- Fragment DNA via enzymatic or mechanical shearing to a desired size (e.g., 200-300 bp).

- Perform end-repair and ligate sequencing adapters to the fragmented DNA.

- Amplify the library with a limited number of PCR cycles to add index sequences for sample multiplexing [40].

- Quality Control: Assess library concentration using a fluorometer (Qubit) and fragment size distribution using a bioanalyzer (Agilent 2100) [40].

High-Throughput Sequencing:

- Pool multiple, uniquely indexed libraries together.

- Sequence on a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq, BGISEQ-500, etc.). A common depth is 10-20 million reads per library for BALF samples [40].

The subsequent bioinformatic analysis, while critical, is a separate complex process involving quality filtering, host sequence subtraction, microbial classification, and interpretation.

For researchers investigating respiratory co-infections, selecting and processing the appropriate specimen type is a critical first step that directly impacts diagnostic accuracy. Traditional Sanger sequencing, while reliable for confirming single pathogens, faces significant limitations in complex co-infction scenarios where multiple organisms may be present. This technical support center provides targeted strategies for optimizing bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), sputum, and blood specimen processing to overcome these challenges, with a specific focus on methodologies that complement Sanger sequencing's constraints in polymicrobial detection.

Comparative Performance of Respiratory Specimens

Understanding the relative strengths and weaknesses of different specimen types enables researchers to select the most appropriate sample for their experimental goals, particularly when investigating co-infections that Sanger sequencing might miss.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Respiratory Specimen Types for Pathogen Detection

| Specimen Type | Detection Sensitivity | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BALF | 84.7% sensitivity (mTGS) [44] | Direct sampling from infection site; superior for atypical pathogens | Invasive collection procedure; requires specialized equipment | Gold standard for lower respiratory infections; immunocompromised hosts |

| Sputum | 39.4% sensitivity (culture) [45] | Non-invasive collection; widely accessible | Contamination risk from upper airways; lower pathogen yield | Routine community-acquired pneumonia; follow-up testing |

| Blood | Not quantified in results | Systemic infection detection; sterile sample | Low sensitivity for localized respiratory infections | Sepsis workup; disseminated infections |

Detailed Methodologies for Specimen Processing

Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid (BALF) Processing Protocol

Optimized BALF processing significantly enhances pathogen detection rates. The following protocol, validated in recent studies, demonstrates substantial improvement over conventional methods:

Sample Collection: Perform bronchoalveolar lavage via fiberoptic bronchoscopy wedged in the affected bronchopulmonary segment. Instill 100-150 mL sterile saline (5-7 aliquots of 20 mL) with a minimum return of 30% total volume [46]. For pathogen identification, collect 10-20 mL of BALF.

Sample Processing for Molecular Studies:

- Pre-process samples to achieve total cell concentration ≥1×10⁶ cells/mL for host removal [47]

- Extract nucleic acids using magnetic bead-based methods [45] or commercial kits (QIAamp DNA Mini Kit) [46]

- For metagenomic studies, omit host DNA depletion step [44]

- Utilize 800 MB sequencing depth for optimal detection sensitivity [44]