Beyond Simulation: Augmenting FEA with AI and Multi-Method Diagnostics for Advanced Drug Development

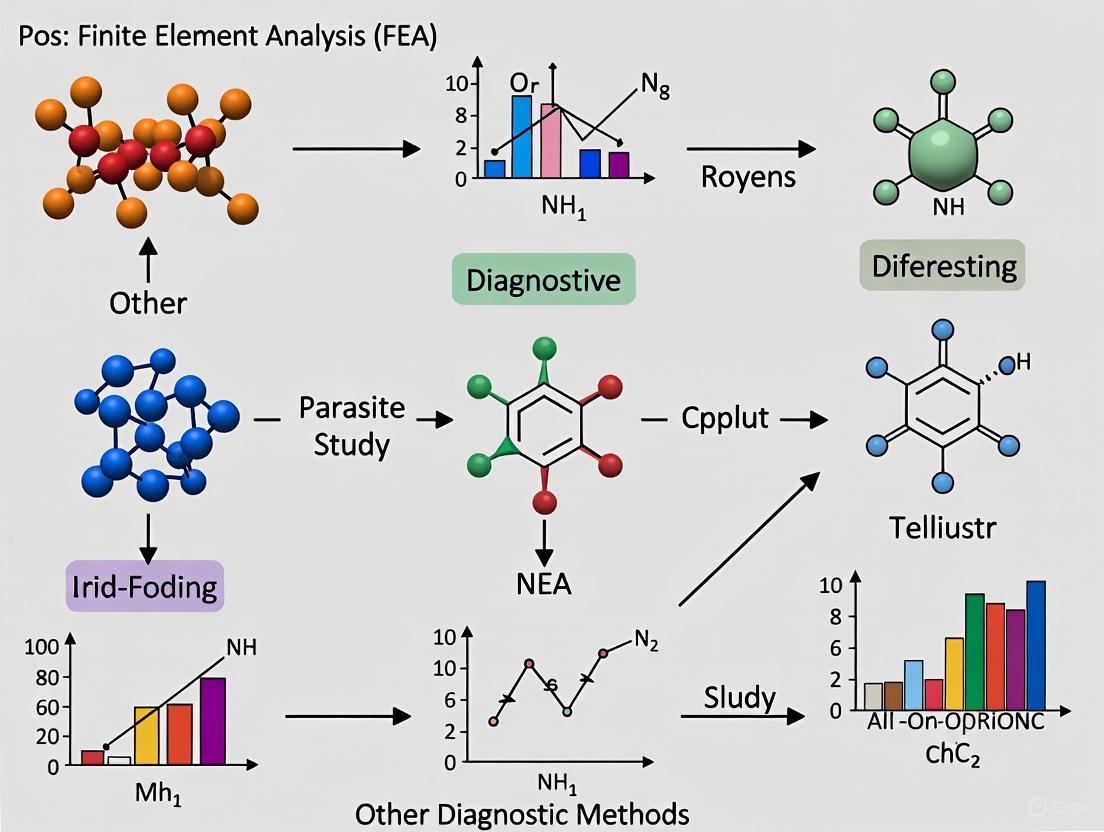

This article explores the transformative potential of integrating Finite Element Analysis (FEA) with complementary diagnostic and computational methods to address complex challenges in pharmaceutical research and development.

Beyond Simulation: Augmenting FEA with AI and Multi-Method Diagnostics for Advanced Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the transformative potential of integrating Finite Element Analysis (FEA) with complementary diagnostic and computational methods to address complex challenges in pharmaceutical research and development. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive framework that moves beyond traditional FEA. The scope covers foundational principles, practical methodologies for integration with AI and machine learning, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing multi-method workflows, and robust validation techniques. By synthesizing insights from foundational exploration to comparative analysis, this guide aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to enhance predictive accuracy, accelerate development cycles, and innovate in drug formulation and delivery systems.

The Core and The Context: Understanding FEA's Role in the Modern Diagnostic Toolkit

Finite Element Analysis (FEA) is a computational technique that allows researchers to simulate and analyze how complex structures respond to various physical forces and environments. In biomedical applications, FEA has become a pivotal tool for simulating complex biomechanical behavior in anatomically accurate, patient-specific models [1]. The fundamental principle of FEA involves breaking down complex biological structures into numerous smaller, simpler elements—a process known as meshing [2]. Scientific computing then solves the governing physical equations across this mesh, enabling the prediction of stress distribution, strain energy density, and displacement patterns throughout the biological system [1].

The integration of FEA with other diagnostic methods represents a transformative approach in biomedical research, creating high-fidelity digital models that bridge diagnostic imaging with computational simulation. This integration enhances the efficiency and effectiveness of biomedical practices by enabling rapid virtual evaluations of multiple scenarios, significantly accelerating research analysis while reducing resource costs [1]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding FEA fundamentals provides a powerful framework for investigating biological systems without exclusive reliance on extensive physical prototyping or clinical trials.

Core Principles of FEA

The Discretization Process: From Continuum to Elements

The foundational concept of FEA is discretization, where a complex continuous structure is subdivided into numerous simpler geometric elements connected at nodes. This process transforms an intractable continuum problem into a solvable system of algebraic equations. As described in failure analysis contexts, FEA "allows components of complex shape to be broken down into many smaller, simpler shapes (elements) that can be analyzed more easily than the overall complex shape" [2]. The meshing process is critically important for developing accurate results—the model must be divided into a sufficient number of well-formed elements to accurately represent the shape of the overall component structure [2].

Governing Equations and Material Properties

FEA simulations solve the fundamental equations of physics governing the system under investigation—typically equations of motion, heat transfer, or fluid flow. The accuracy of these simulations depends heavily on appropriate material property assignment. In biomechanical modeling, accurate material properties derived from patient-specific scans are essential for simulations to accurately mimic real-life scenarios [3]. Research has demonstrated the ability to predict key material properties including Young's modulus, Poisson's ratio, bulk modulus, and shear modulus with high accuracy (94.30%) through integrated approaches [3].

Table 1: Key Material Properties in Biomechanical FEA

| Property | Definition | Physiological Significance | Exemplary Values from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Young's Modulus | Measures material stiffness under tension | Determines how much tissue deforms under load | Cortical bone: 14.88 GPa; Intervertebral disc: 1.23 MPa [3] |

| Poisson's Ratio | Ratio of transverse to axial strain | Describes how material contracts/expands in multiple directions | Cortical bone: 0.25; Intervertebral disc: 0.47 [3] |

| Shear Modulus | Resistance to shearing deformation | Important for torsion and shear loading analyses | Cortical bone: 5.96 GPa; Intervertebral disc: 0.42 MPa [3] |

Boundary Conditions and Loading

Appropriate boundary conditions and loading parameters are essential for clinically relevant FEA results. These mathematical representations of physical constraints and applied forces determine how the model interacts with its environment. In biomedical FEA, boundary conditions must reflect physiological reality—for instance, simulating representative masticatory loading in dental applications [1] or spinal loads in lumbar modeling [3]. Proper application of boundary conditions ensures that simulation results translate meaningfully to clinical or research applications.

Integrated FEA Workflows for Biomedical Research

Complete Digital Workflow: From Imaging to Simulation

A comprehensive digital workflow for biomedical FEA integrates multiple technologies from initial imaging to final simulation. Recent research demonstrates a validated integrated digital workflow for generating anatomically accurate tooth-specific models that combines micro-CT imaging, 3D printing, manual preparation by a dentist, digital restoration modeling by a dental technician, and FEA [1]. This approach enables comparative mechanical evaluation of different designs on the same biological geometry, providing a powerful framework for optimization studies.

Digital Workflow for Biomedical FEA

Advanced Integration: FEA with Physics-Informed Neural Networks

Emerging methodologies integrate FEA with other computational approaches to enhance predictive capabilities. The integration of FEA with Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) represents a significant advancement for biomechanical modeling, automating segmentation and meshing processes while ensuring predictions adhere to physical laws [3]. This integration allows for accurate, automated prediction of material properties and mechanical behaviors, significantly reducing manual input and enhancing reliability for personalized treatment planning [3].

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical factors for ensuring accuracy in biomedical FEA simulations? A: The accuracy of biomedical FEA simulations depends on three primary factors: (1) high-resolution imaging data (e.g., micro-CT with isotropic voxel sizes of 10×10×10μm) [1], (2) appropriate material properties derived from experimental testing or literature [3], and (3) physiological boundary conditions and loading scenarios that reflect real-world conditions [1] [2]. Additionally, mesh quality must be optimized—smaller elements in regions of interest and stress concentration, with proper element formulation for the analysis type.

Q2: How can I validate my FEA models for biomedical applications? A: Validation should employ a multi-modal approach: (1) comparison with experimental data from physical testing (e.g., strain gauge measurements), (2) convergence studies to ensure mesh-independent results, (3) comparison with clinical outcomes when available, and (4) verification against analytical solutions for simplified geometries. Recent methodologies incorporate 3D-printed typodonts based on micro-CT scans for physical validation of digital models [1].

Q3: What resolution of imaging data is required for creating accurate FEA models? A: High-resolution micro-CT scanning is recommended, capturing 2525 digital radiographic projections at settings appropriate to the specimen (e.g., 100 kV voltage, 110 µA tube current, 700ms exposure time for natural teeth) [1]. This typically yields reconstructed images with isotropic voxel sizes of 10×10×10μm, sufficient for capturing relevant anatomical details for biomechanical simulation.

Q4: How does the integration of FEA with other diagnostic methods enhance research outcomes? A: Integrating FEA with diagnostic methods like micro-CT creates a synergistic workflow that combines anatomical precision with computational predictive power. This enables researchers to "trace the complete workflow from clinical procedures to simulation" [1], provides capabilities for "virtual assessments of potential risks associated with tissue failures under diverse loading conditions" [1], and facilitates "design optimization strategy which involves identifying candidate materials with specific mechanical characteristics" [1] for improved clinical outcomes.

Troubleshooting Common FEA Issues

Problem: Convergence difficulties in nonlinear simulations Solution: Implement progressive loading increments, ensure proper material model parameters, check for unrealistic material behavior or geometric instabilities, and verify contact definitions if applicable. For biomechanical materials exhibiting complex behavior, consider hyperelastic or viscoelastic material models with parameters derived from experimental testing.

Problem: Inaccurate stress concentrations at interfaces Solution: Refine mesh at critical interfaces, verify material property assignments, ensure proper contact definitions between different tissues/materials, and validate against known analytical solutions or experimental data. In tooth-inlay systems, this is particularly important for identifying stress concentrations at the tooth-restoration interface [1].

Problem: Discrepancies between simulation results and experimental observations Solution: Verify boundary conditions accurately represent experimental setup, confirm material properties are appropriate for the strain rate and loading conditions, check for modeling assumptions that may not hold in physical testing, and ensure the model includes all relevant anatomical features. The use of "digital twins" created through high-resolution micro-CT scanning can minimize geometric discrepancies [1].

Problem: Excessive computation time for complex models Solution: Implement submodeling techniques (global-coarse and local-fine meshes), utilize symmetry where appropriate, employ efficient element formulations, and consider high-performance computing resources. For initial design iterations, slightly coarser meshes can provide directionally accurate results more quickly.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for Biomedical FEA Validation

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Micro-CT Scanner | High-resolution 3D imaging of biological specimens | System capable of ~10μm resolution (e.g., Nikon XT H 225); software for 3D reconstruction (e.g., Inspect-X) [1] |

| Photopolymer Resin | 3D printing of anatomical models for validation | Anycubic Water-Wash Resin + Grey recommended for favourable mechanical properties and aesthetic appearance critical for manual preparations [1] |

| Segmentation Software | Conversion of imaging data to 3D models | VGSTUDIO MAX for segmentation, surface model refinement, and extraction; Meshmixer for model optimization [1] |

| FEA Software Platform | Biomechanical simulation | System capable of nonlinear FEA, complex material models, and import of anatomical geometries from medical imaging |

| Dental Operating Microscope | Precision preparation of physical models | Microscope with appropriate magnification (e.g., 6x) for meticulous precision and reproducibility of cavity geometries [1] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Development of Validated Tooth-Specific Digital Models

This protocol outlines the methodology for creating anatomically accurate digital models of tooth-inlay systems based on established research [1]:

Specimen Preparation:

- Select human tooth specimens extracted for surgical reasons (e.g., second molar with fused root)

- Perform mechanical cleaning using periodontal curette to remove organic debris

- Polish with brush and paste

- Store at 4°C in 0.1% thymol solution prepared in physiological saline (pH 7) to maintain integrity

- Conduct stereomicroscopic examination at 40× magnification to identify and exclude specimens exhibiting fractures or cracks

Initial Micro-CT Scanning:

- Use Nikon XT H 225 system or equivalent

- Capture 2525 digital radiographic projections at 100 kV voltage and 110 µA tube current

- Set exposure time to 700 ms with 1 mm Al filtration of the beam

- Achieve resolution with cubic dimension of 10 × 10 × 10 μm

- Use reconstruction software (e.g., X-AID) for image processing

Image Segmentation and 3D Reconstruction:

- Perform segmentation using VGSTUDIO MAX 2023.4 or similar software

- Apply region-growing algorithm and digital pen for masking calcified regions

- Fill regions with grey values matching adjacent pulp space to maintain anatomical continuity

- Apply Taubin smoothing filter to address surface irregularities and morphological protrusions

- Optimize model using Meshmixer or equivalent software

Physical Model Fabrication:

- 3D print typodonts using Masked Stereolithography Apparatus (MSLA) technology

- Use Anycubic Photon Mono 2 3D printer with Anycubic Water-Wash Resin + Grey

- Set layer height to 50 μm for adequate resolution

- Strategically arrange models on build platform with appropriate supports

Cavity Preparation:

- Perform manual preparation using high-speed handpiece (e.g., NSK PANA-MAX)

- Conduct procedure under magnification provided by dental operating microscope (e.g., 6x magnification)

- Employ varied preparation techniques (conventional and biomimetic) on multiple typodont models

Post-Preparation Micro-CT Scanning:

- Rescan prepared typodonts using micro-CT system with adjusted settings

- Use 80 kV voltage and 100 µA tube current for typodont material

- Maintain 700ms exposure time per projection

- Ensure reconstructed images maintain isotropic voxel size of 10 × 10 × 10 μm

Virtual Restoration Design and FEA:

- Import STL files representing prepared typodonts into design software (e.g., Exocad)

- Model digital inlays and onlays based on anatomical contours

- Generate appropriate mesh for FEA simulations

- Assign material properties based on experimental data or literature values

- Perform nonlinear FEA simulations under representative masticatory loading conditions

- Analyze resulting stress distributions, strain energy density, and displacement patterns

Protocol: Integration of FEA and Physics-Informed Neural Networks

This protocol details the methodology for integrating FEA with PINNs for lumbar spine modeling [3]:

Data Acquisition:

- Acquire high-quality CT and MRI scans of lumbar spine specimens

- Ensure appropriate resolution for segmenting vertebrae and intervertebral discs

Model Development:

- Develop FEA model of lumbar spine incorporating detailed anatomical and material properties

- Segment and mesh vertebrae and discs using advanced imaging and computational techniques

- Implement PINNs to integrate physical laws directly into neural network training process

Material Property Prediction:

- Train neural networks to predict key material properties while adhering to governing equations of mechanics

- Validate predicted properties (Young's modulus, Poisson's ratio, bulk modulus, shear modulus) against experimental data

Simulation and Analysis:

- Execute FEA simulations with PINN-predicted material properties

- Verify that predictions follow mechanical laws and provide clinically relevant results

FEA and PINN Integration Workflow

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Table 3: Experimentally Determined Material Properties for Biomechanical FEA

| Tissue/Material | Young's Modulus | Poisson's Ratio | Bulk Modulus | Shear Modulus | Source/Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical Bone | 14.88 GPa | 0.25 | 9.87 GPa | 5.96 GPa | PINN prediction from CT scans (94.30% accuracy) [3] |

| Intervertebral Disc | 1.23 MPa | 0.47 | 6.56 MPa | 0.42 MPa | PINN prediction from MRI (94.30% accuracy) [3] |

| Dental Restorative Materials | Varies by product | Varies by product | Varies by product | Varies by product | Manufacturer specification with experimental validation [1] |

| 3D Printing Resin | ~2-3 GPa (typical) | ~0.35-0.40 (typical) | - | - | Experimental characterization for model validation [1] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common FEA Pitfalls in Biological Systems

Poroelastic Pressure Instabilities

- Problem: Unphysical oscillations in interstitial fluid pressure, especially near boundaries or between different materials.

- Cause: This ill-conditioning arises when simulating rapidly loaded, slow-draining materials. The numerical instability is due to the differing mathematical order of the solid displacement and fluid pressure fields [4].

- Solution:

- Refine Mesh: Use a finer mesh. For a 1D analysis, the Vermeer–Verruijt criterion provides a guideline:

Δh ≤ √( (6 E k Δt) / γ ), whereΔhis mesh size,Eis elastic modulus,kis permeability,Δtis time step, andγis fluid specific weight [4]. - Element Selection: Switch to higher-order elements (e.g., Taylor-Hood elements with quadratic interpolation for solid displacement and linear interpolation for pressure) [4].

- Compromise on Time Step: Use a longer time step where computationally feasible, as stability requires

Δt ≥ (γ Δh²) / (6 E k)[4].

- Refine Mesh: Use a finer mesh. For a 1D analysis, the Vermeer–Verruijt criterion provides a guideline:

The "Sloppy Model" Problem and Unidentifiable Parameters

- Problem: Models have many parameters that are poorly constrained by data, making accurate parameter estimation impossible or impractical [5].

- Cause: The model may be overly complex, including more mechanisms than are necessary to explain the phenomenon of interest. Many parameter combinations have an exponentially small effect on system behavior [5].

- Solution:

- Model Reduction: Identify and fix or remove irrelevant parameters that do not significantly affect model predictions [5].

- Hierarchical Modeling: Approach the problem by considering a hierarchy of models of varying detail rather than focusing on parameter estimation in a single, overly complex model [5].

- Optimal Experimental Design: Design experiments specifically to constrain the stiff (important) parameter combinations, but be aware that this can sometimes reveal model discrepancy [5].

Model Discrepancy and Systematic Error

- Problem: A model fits existing data well but fails to predict the outcomes of new, optimally selected experiments [5].

- Cause: The model is an approximation that has omitted certain physical mechanisms. Complementary experiments from an optimal design can make these omitted details relevant, leading to large systematic errors [5].

- Solution:

Stiffness and Computational Cost

- Problem: Simulations are computationally expensive or intractable due to systems where variables change at drastically different timescales [6].

- Cause: Biological systems often involve interactions between processes operating at different timescales. Using a single, fine-grained time partition for all variables leads to long computation times [6].

- Solution:

- Advanced Solvers: Implement methods like the Quantized State System (QSS), which divides the temporal domain into variable-length intervals for each variable based on its rate of change. This avoids stiffness and reduces computations [6].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My FEA model of cartilage shows extreme pressure values at the draining surface. What is the most likely cause? The most likely cause is poroelastic instability. This is a known issue when modeling slow-draining tissues (low permeability) under rapid loading conditions. The instability is intrinsic to the u-p (displacement-pressure) formulation with standard linear elements and is exacerbated at permeable boundaries [4].

Q2: Why should I not always use optimal experimental design to improve parameter identifiability in my complex model? While optimal experimental design can improve parameter identifiability, it carries a risk. By selecting highly complementary experiments, you may inadvertently make physical mechanisms that were omitted from your simplified model become relevant. When this happens, your model will fail to fit the new data well due to systematic error, ultimately reducing its predictive power [5].

Q3: What is a practical first step if my model has hundreds of parameters and I suspect many are unidentifiable? Analyze the eigenvalues of the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM). A sloppy model will show eigenvalues spread over many orders of magnitude. The parameter combinations corresponding to the smallest eigenvalues (the sloppy directions) can often be fixed to arbitrary values or removed from the model without harming its fit to the existing data [5].

Q4: Are there software packages that can help overcome the limitations of general FEA for specific biological problems? Yes, specialized tools are emerging. For simulating cell signaling in realistic 3D geometries, the SMART package uses finite element methods to solve mixed-dimensional reaction-transport equations, effectively handling complex cellular and subcellular geometries [7]. For biomechanics, FEBio is a solver specifically designed for biomechanical applications [8].

Quantitative Data for Poroelastic Instability

Vermeer-Verruijt Instability Criteria for Disc Tissues

The table below shows the minimum stable time step required for a mesh with a characteristic element size (Δh) of 1 mm, based on the Vermeer-Verruijt criterion. Values are for tissues representative of the intervertebral disc [4].

| Material | Elastic Modulus (E) MPa | Permeability (k) m⁴/N·s | Minimum Time Step (Δt) seconds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annulus (Circumferential) | 2.52 | 1.61 × 10⁻¹⁵ | 41 |

| Annulus (Radial) | 0.19 | 1.61 × 10⁻¹⁵ | 545 |

| Nucleus | 0.14 | 1.15 × 10⁻¹⁵ | 1035 |

Element Performance in Poroelastic Analysis

The table below compares the performance of different element types for mitigating pressure instabilities [4].

| Element Type | Displacement Field | Pressure Field | Relative Mesh Size for Stability | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Linear | Linear | Constant | > 10,000 elements (baseline) | Lower |

| Taylor-Hood | Quadratic | Linear | Fewer elements required | Higher (increased degrees of freedom) |

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol 1: Empirical Analysis of Poroelastic Instability

- Objective: To determine the circumstances under which pressure instability problems occur in tissues like the intervertebral disc [4].

- Model Setup:

- Geometry: Create a 3D cylindrical test case with an initial height and diameter of 5 mm.

- Materials: Assign material properties representing the nucleus pulposus and the annulus fibrosus of the intervertebral disc. Use worst-case (nucleus) and best-case (circumferential annulus) properties from published data.

- Boundary Conditions: Run analyses with differing drainage boundary conditions.

- Simulation:

- Element Types: Test the model with both a linear displacement-constant pressure element and a quadratic displacement-linear pressure (Taylor-Hood) element.

- Mesh & Time Step: Systematically vary the mesh refinement and the size of the time step.

- Output: Monitor calculated fluid pressures for spurious spatial oscillations, especially in initial time steps and near boundaries.

- Validation: Compare the empirical relationship between mesh size and time step required for stability against the Vermeer–Verruijt criterion derived for 1D analysis [4].

Protocol 2: Assessing Model Sloppiness and Parameter Identifiability

- Objective: To evaluate a model's sloppiness and the impact of optimal experimental design on model discrepancy [5].

- Methodology:

- Define Model & Data: Start with a mathematical model (e.g., of EGFR signaling or DNA repair) and a set of existing experimental data.

- Calculate FIM: Compute the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) at the maximum likelihood parameter estimates.

- Eigenvalue Analysis: Calculate the eigenvalues of the FIM. A sloppy model will exhibit eigenvalues λ_μ that are roughly evenly spaced on a log scale over many orders of magnitude.

- Experimental Design:

- Optimal Design: Use optimal experimental design techniques to select a new experiment predicted to maximize the identifiability of model parameters.

- Hyper-Model of Error: Use a simple hyper-model to quantify the model's inherent discrepancy.

- Comparison: Fit the model to data from the new "optimal" experiment. Assess whether the model can achieve a good fit or if the systematic error (discrepancy) becomes large, reducing predictivity [5].

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

Diagram: Poroelastic Instability Troubleshooting Path

Diagram: Hybrid Framework for Augmenting FEA

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| SMART (Spatial Modeling Algorithms for Reactions and Transport) | A software package that uses finite element analysis to solve systems of mixed-dimensional reaction-transport equations in complex cellular geometries [7]. | Modeling cell signaling networks (e.g., YAP/TAZ mechanotransduction, calcium dynamics) in realistic 3D cell geometries derived from microscopy [7]. |

| FEBio | A finite element solver specifically designed for biomechanics and biophysics simulations [8]. | General biomechanical applications, including analysis of soft tissues, joints, and medical devices [8]. |

| Taylor-Hood Elements | A type of finite element using quadratic interpolation for the solid displacement field and linear interpolation for the fluid pressure field [4]. | Mitigating pressure instabilities in poroelastic analyses of biological soft tissues (e.g., intervertebral disc, cartilage) [4]. |

| QSS (Quantized State System) Solver | An integration method that divides the temporal domain into variable-length intervals for each variable, bounded by a quantum of error [6]. | Solving stiff differential equations in hybrid system models, efficiently handling interacting sub-models with different timescales [6]. |

| GAMer 2 (Geometry-preserving Adaptive Mesher) | Software to convert microscopy images of cells into well-conditioned tetrahedral meshes suitable for finite element simulations [7]. | Preparing realistic cellular and subcellular geometries for spatial modeling of biological processes [7]. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Augmenting FEA with AI and Diagnostic Methods

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when integrating artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), and physical sensing methods with Finite Element Analysis (FEA) in diagnostic research.

Table 1: Frequently Asked Questions on AI and FEA Integration

| Question | Issue Description | Recommended Solution | Key References & Data Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Quality and Trust | How can I build trust in AI "black box" models for critical diagnostics? | Implement Explainable AI (XAI) frameworks that combine multiple interpretation methods (e.g., SHAP for feature importance and Grad-CAM for visual saliency maps) to make AI decisions transparent and actionable. [9] | Trust Score: A survey-based evaluation of a Feature-Augmented XAI approach for Alzheimer's diagnosis achieved a 100% trust score from medical experts, with 80% expressing conditional trust and 20% full trust. [9] |

| FEA-AI Workflow Integration | Our FEA-based failure analysis is slow and costly. How can AI improve efficiency? | Integrate AI to automate pre-processing steps (e.g., meshing, boundary condition selection) and use AI-driven design optimization to run thousands of virtual design variants, identifying optimal solutions before physical prototyping. [10] | Performance Gains: AI-FEA integration in automotive component design can reduce design cycles by 30-50%, cut prototype counts by half, and improve predicted fatigue life by 18%. [10] |

| Data Visualization and Interpretation | How can I ensure my diagnostic results and FEA data visualizations are clear and accessible? | Adhere to data visualization best practices: maximize the data-ink ratio by removing non-essential chart elements and use color strategically. Ensure all visual elements meet WCAG 2.2 AA contrast requirements (e.g., a minimum contrast ratio of 4.5:1 for standard text). [11] [12] | Contrast Requirements: WCAG 2.2 Level AA requires a minimum contrast ratio of 3:1 for large text and graphical elements and 4.5:1 for standard text. These are absolute thresholds; 4.49:1 or 2.99:1 are fails. [12] |

| Experimental Data Requirements | How much data is needed to train a viable AI model for diagnostic classification? | For classification solutions, the recommended number of records for training is between 30,000 and 100,000. If more than 100,000 records are submitted, systems typically use the most recent 100,000 for training. [13] | Model Performance: A deep learning system for classifying renal cell carcinoma subtypes from histology achieved an accuracy of 93.0%, a sensitivity of 91.3%, and a specificity of 95.6%. [14] |

| Model Validation and FEA Accuracy | How do I ensure my augmented FEA model is accurate and reliable? | Conduct a mesh convergence study to ensure your results do not significantly change with mesh refinement. For AI components, perform verification and validation through mathematical checks and, when possible, correlation with physical test data. [15] [10] | Validation Necessity: No AI-enhanced simulation should completely replace physical validation, as environmental effects and manufacturing defects can surprise even the most sophisticated models. [10] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Feature-Augmented XAI Diagnostic Framework

This protocol outlines the methodology for creating an AI diagnostic model that integrates clinical data (like MMSE scores) and physical sensor data (like MRI scans) with an ensemble learning model, enhanced for explainability. The workflow is based on a successful implementation for Alzheimer's disease diagnosis. [9]

Objective Definition

- Primary Goal: Develop a diagnostic classifier that distinguishes between disease states (e.g., Alzheimer's vs. healthy control) with high accuracy and high explainability to build clinical trust.

- Key Question: "What should be captured by the AI analysis?" Clearly define the diagnostic targets, such as classifying tumor subtypes, predicting structural failure, or identifying early disease biomarkers. [15]

Data Acquisition and Pre-processing

- Clinical & Feature Data: Collect structured data such as clinical scores (e.g., Mini-Mental State Examination, MMSE), genetic markers, or patient demographics.

- Imaging & Physical Sensing Data: Acquire high-resolution medical images (e.g., MRI, CT) or structural sensor data. To reduce computational complexity and enhance focus on relevant regions, a specific slice or sensor stream can be selected (e.g., the mid-slice of an MRI showing the lateral ventricles for Alzheimer's diagnosis). [9]

- Data Cleansing: Handle missing values, normalize numerical data, and encode categorical variables.

Model Training and Interpretation with XAI

- Ensemble Learning: Use an ensemble or meta-model approach to integrate predictions from multiple sub-models trained on different data types (e.g., clinical data and image data). This helps filter irrelevant features and focus on those most predictive. [9]

- Explainable AI (XAI) Implementation:

- For Clinical Features: Apply SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to the clinical data model. SHAP provides a rule-based, quantitative interpretation of how each clinical feature contributed to the final diagnosis for an individual patient. [9]

- For Imaging Data: Apply Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping) to the CNN processing the MRI scans. This generates a visual heatmap overlay on the original image, highlighting the regions (e.g., specific brain areas) most influential in the decision. [9]

Result Integration and Validation

- Unified Explanation Interface: Combine the SHAP-based clinical explanation and the Grad-CAM-based visual explanation into a single, integrated report for the end-user (e.g., clinician or researcher). [9]

- Validation: Perform rigorous validation using hold-out test sets or k-fold cross-validation. Correlate model predictions and highlighted regions with ground truth data (e.g., subsequent patient outcomes, physical test results) to ensure the explanations are clinically or physically plausible. [9] [15]

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for AI-Augmented Diagnostic Research

| Item | Function / Relevance in Research |

|---|---|

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | A class of deep learning neural networks, highly effective for analyzing visual imagery like MRI scans or CT images. It can automatically and adaptively learn spatial hierarchies of features. Examples include ResNet50. [9] [14] |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | An XAI method based on cooperative game theory. It explains the output of any machine learning model by calculating the marginal contribution of each feature to the prediction, providing a clear, rule-based interpretation for clinical or feature data. [9] |

| Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping) | An XAI technique that produces visual explanations for decisions from a CNN. It highlights the important regions in an image (via a heatmap) that led to the model's prediction, crucial for interpreting image-based diagnostics. [9] |

| Whole Slide Images (WSIs) | High-resolution digital scans of entire histology slides. These are the foundational data for AI-based histopathological analysis, enabling the systematic identification of pathological features and intratumor heterogeneity. [14] |

| AI-Optimized FEA Meshing Tools | Software that uses AI algorithms to automate the generation of finite element meshes with optimal element density in critical areas. This reduces human effort, a traditional bottleneck, while maintaining simulation accuracy. [10] |

| Telemetry & Sensor Data | Real-world operational data (e.g., suspension travel, acceleration, temperature) from vehicles or other physical systems. AI uses this data to identify realistic and extreme load cases for FEA simulations, moving beyond simplified lab assumptions. [10] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main benefits of combining Finite Element Analysis (FEA) with machine learning (ML)? Integrating FEA with machine learning creates a powerful synergy that overcomes the limitations of each method used independently. The primary benefits include a massive increase in computational speed while retaining high accuracy, improved performance on complex inverse problems, and the ability to generate rapid, patient-specific predictions for clinical use.

- Speed with Accuracy: Pure FEA can be computationally expensive and time-consuming, making it unsuitable for time-sensitive applications like clinical prognosis. Machine learning models, particularly Deep Neural Networks (DNNs), can act as fast surrogates for FEA. However, these data-driven models can produce unacceptably high errors, especially on data that differs from their training set. A synergistic integration, where a DNN provides a rapid initial prediction that is then refined by a targeted FEA correction, has been shown to achieve accuracy comparable to high-fidelity FEA but at a significantly faster rate [16].

- Solving Inverse Problems: For inverse problems, such as identifying heterogeneous material properties from observed behavior, a traditional FEM-only inverse method can lead to large errors (over 50%). Using a DNN as a regularizer in the inverse analysis process can dramatically improve performance, reducing errors to less than 1% [16].

- Clinical Forecasting: In fields like cardiology, combined biophysics and ML models can efficiently predict the probability of cardiac growth and remodeling. This integrative framework can be translated to predict patient-specific outcomes, which is essential for long-term heart failure management [17].

Q2: My pure Deep Neural Network (DNN) model for biomechanical prediction sometimes fails on new cases. How can I fix this? This failure is likely because your new data falls outside the distribution of your training data (Out-of-Distribution or OOD cases). A synergistic DNN-FEM integration is an effective solution to this problem [16].

- Problem: DNNs are data-driven and may not generalize well to new, unseen data scenarios, leading to large errors (e.g., peak stress errors >50%).

- Solution: Implement a workflow where the DNN provides a fast initial prediction. This output is then fed into a FEM solver for a refinement step. This hybrid approach ensures physical consistency and accuracy, eliminating large errors for OOD cases while remaining magnitudes faster than a full FEM-only simulation [16].

Q3: Are there alternative numerical methods that can outperform FEA? Yes, the choice of numerical method depends on the specific application. The Boundary Element Method (BEM), particularly when accelerated with the Fast Multipole Method (FMM), can outperform FEA in certain scenarios.

The table below summarizes a comparative study for modeling cortical neurostimulation:

| Feature | Finite Element Method (FEM) | Boundary Element Fast Multipole Method (BEM-FMM) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Application | Widely used in structural analysis, biomechanics, and various engineering fields [18] [19] | Often used in EEG/MEG modeling and specific electromagnetic problems [19] |

| Computational Speed | Slower for high-resolution meshes; a commercial FEM package (ANSYS) was thousands of times slower in one TMS study [19] | Faster for high-resolution meshes; demonstrated a speed improvement of three orders of magnitude in a realistic TMS scenario [19] |

| Mesh Requirements | Requires a volumetric mesh of the entire domain [19] | Only requires a surface mesh of the boundaries between domains [19] |

| Solution Error | Error can be larger for certain mesh resolutions [19] | Can yield a smaller solution error for all mesh resolutions in canonic problems [19] |

Q4: How can I implement a hybrid FEA-ML workflow for a practical problem like aortic biomechanics? The following experimental protocol outlines the methodology for integrating DNNs and FEM for forward and inverse problems in aortic biomechanics [16].

Experimental Protocol: DNN-FEM Integration for Aortic Biomechanics

1. Objective: To accurately and efficiently perform stress analysis (forward problem) and identify material parameters (inverse problem) for a human aorta.

2. Materials and Computational Tools:

- Software: A finite element solver (e.g., ANSYS, Abaqus, or open-source alternatives like FEniCS) and a machine learning framework (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch).

- Data: Patient-specific or synthetic geometric and material property data of the human aorta.

3. Methodology:

A. Forward Problem (Predicting Stress from Loads/Material Properties)

- Step 1: Data Generation. Use FEA to generate a high-fidelity dataset of aortic deformations and stresses under various loading conditions and material properties.

- Step 2: DNN Training. Train a state-of-the-art Deep Neural Network (e.g., a Convolutional Neural Network or a fully connected network) using the FEA results as ground truth. The inputs are the boundary conditions and material properties, and the outputs are the stress and deformation fields.

- Step 3: DNN Prediction and FEM Refinement.

- Use the trained DNN to make a fast prediction on a new case.

- Feed the DNN's output into the FEM solver as an initial condition.

- Run a limited, corrective FEA simulation to refine the solution and ensure physical accuracy, especially for cases where the DNN might be uncertain.

B. Inverse Problem (Identifying Material Properties from Observed Deformation)

- Step 1: Framework Setup. Instead of a direct FEM inversion, which is often ill-posed, use a DNN as a regularizer.

- Step 2: Constrained Optimization. The inverse analysis is formulated as an optimization problem where the goal is to find the material parameters that minimize the difference between the observed data and the model prediction. The DNN provides a probabilistic prior or a constraint that guides the solution toward physically plausible and realistic material distributions.

- Step 3: Solution. The integrated DNN-FEM solver identifies the material parameters, significantly reducing errors compared to a traditional inverse FEM approach.

4. Key Workflow Diagram: The diagram below illustrates the logical flow of the synergistic DNN-FEM integration for both forward and inverse problems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key computational tools and data types used in synergistic FEA-ML research, as featured in the cited experiments.

| Tool / Data Type | Function in Synergistic Research |

|---|---|

| Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) | Acts as a fast surrogate model for FEA; provides initial predictions and regularizes inverse problems [16]. |

| Finite Element Method (FEM) Solver | Provides high-fidelity ground truth data for training; refines ML outputs to ensure physical accuracy [16] [19]. |

| Boundary Element Fast Multipole Method (BEM-FMM) | An alternative numerical method for specific electromagnetic problems that can offer superior speed and accuracy compared to FEA [19]. |

| Drug Resistance Signatures (DRS) | A biologically informed feature set used in ML models (e.g., for drug synergy prediction) that captures transcriptomic changes, improving model accuracy and generalizability [20]. |

| Large Language Models (LLMs) | Used to generate context-enriched embeddings for drugs and cell lines, serving as informative input features for unified predictive models in drug discovery [21]. |

| Bayesian History Matching | A calibration technique, augmented with Gaussian process emulators, used to efficiently align biophysics model parameters with experimental growth data within a confidence interval [17]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common errors in FEA for biomedical applications and how can I avoid them? The most common FEA errors include insufficient constraints leading to rigid body motion, unconverged solutions from nonlinearities, and element formulation errors from highly distorted elements. To prevent these, always perform a modal analysis to identify under-constrained parts, use Newton-Raphson residual plots to troubleshoot contact regions causing non-convergence, and ensure high mesh quality in critical areas [15] [22].

Q2: How can FEA be integrated with other diagnostic methods in a research workflow? FEA can be combined with medical imaging and machine learning for enhanced diagnostics. For instance, CT or MRI DICOM files can be used for 3D reconstruction of anatomical structures, forming the basis for patient-specific finite element models. These models can then simulate mechanical behavior to assess risks, such as aneurysm rupture, complementing traditional diagnostic data [23] [24].

Q3: What role does mechanics play in the design of advanced drug delivery systems? Mechanics is crucial for designing microparticles and implants for controlled drug release. It influences how non-spherical particles interact with the body, their degradation behavior, and release kinetics. Computational mechanics, including FEA and CFD, can model complex interactions like deformation, pressure fields, and flow within syringes to optimize design and function without extensive experimentation [25].

Q4: Why is a mesh convergence study critical in biomechanical FEA? Mesh convergence ensures your results are numerically accurate and not dependent on element size. Without it, computed stresses and strains may be unreliable. A converged mesh produces no significant result changes upon further refinement, which is essential for capturing peak stresses in areas like aortic walls or bone structures accurately [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Solver Reports "DOF Limit Exceeded" or Rigid Body Motion

Problem: The analysis fails due to excessive rigid body motion, indicating insufficient constraints.

Solution:

- Step 1: Check that all parts in your assembly are properly constrained against free translation and rotation.

- Step 2: Use a Modal Analysis with the same supports; modes at 0 Hz highlight under-constrained parts.

- Step 3: For contact-dependent models, ensure nonlinear contacts are initially closed using the Contact Tool.

- Step 4: If using force-based loading, consider switching to displacement-controlled loading to help close contacts [22].

Issue 2: Nonlinear Solution Fails to Converge

Problem: The solver cannot find an equilibrium solution, often due to material, contact, or geometric nonlinearities.

Solution:

- Step 1: Activate Newton-Raphson Residual plots to identify geometric regions with high residuals (red areas).

- Step 2: If high residuals are in contact regions, refine the mesh there and reduce contact normal stiffness (e.g., factor 0.01).

- Step 3: Remove all nonlinearities (plasticity, contact, large deflection) to verify a linear solution, then reintroduce them one by one.

- Step 4: Check for large deformations or plasticity in solved substeps that may cause instability [22].

Issue 3: "Element Formulation Error" or Highly Distorted Elements

Problem: Elements become too distorted, causing early solver termination.

Solution:

- Step 1: Locate the problematic elements using "Named Selections for element violations".

- Step 2: Improve mesh quality in these regions; avoid high aspect ratios and highly skewed shapes.

- Step 3: Check for initial contact penetrations using the Contact Tool and use "Add Offset" or "Adjust to Touch".

- Step 4: For scenarios with large plasticity, ensure the mesh can handle the deformation, or use a failure criterion to stop the analysis if the component is deemed failed [22].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Patient-Specific Aortic Aneurysm Rupture Risk Assessment

This methodology creates a digital twin of a patient's aorta to quantify rupture risk by calculating wall tension, strain, and displacement [23].

1. 3D Model Reconstruction:

- Input: Medical CT scans in DICOM format.

- Software: Use Mimics (Materialise) or similar.

- Procedure:

- Import DICOM series.

- Apply threshold tuning for rough segmentation.

- Create and process masks for a preliminary 3D model.

- Smooth and refine the model to create a CAD-ready mesh.

2. Finite Element Model Setup:

- Solver: COMSOL Static module or equivalent.

- Material Model: Isotropic elasticity for aortic wall [23].

- Key Parameters:

- Young's Modulus: Patient-specific, from literature if unavailable.

- Poisson's Ratio: Typically 0.49 (nearly incompressible).

- Wall Thickness: From medical images or literature.

- Boundary Conditions:

- Fix inlet and outlet surfaces.

- Apply static internal pressure (e.g., physiological blood pressure).

- Mesh: Tetrahedral elements (~150,000-200,000), minimum size 1mm. Perform mesh sensitivity analysis.

3. Simulation and Analysis:

- Solve for stress (von Mises), strain, and displacement.

- Identify maximum stress concentrations in the aneurysmal region.

- Correlate stress magnitudes with historical rupture risk data.

Protocol 2: Microparticle Mechanics for Controlled Drug Release

This protocol uses FEA to understand the mechanical behavior of biodegradable polymeric microparticles, optimizing them for pulsatile drug release [25].

1. Microparticle Fabrication (In-silico Model):

- Design: Create core-shell 3D geometries (e.g., using SEAL fabrication parameters).

- Material: Assign PLGA properties (biodegradable polymer).

2. Finite Element Analysis of Degradation:

- Physics: Coupled poroelasticity for fluid-polymer interaction.

- Loads: Apply thermal stress (37°C) and external pressure from surrounding tissue.

- Outputs: Simulate deformation, stress fields, and degradation-induced pore formation over time.

3. Release Kinetics Correlation:

- Relate simulated structural changes (e.g., shell rupture) to drug release profiles.

- Tune design parameters (shell thickness, polymer composition) to achieve target release timepoints.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Materials and Software for FEA in Pharmaceutical Applications

| Item | Function/Application | Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mimics Software (Materialise) | 3D reconstruction from medical DICOM images | Creates accurate surface models for patient-specific FEA [23]. |

| COMSOL Multiphysics | FEA simulation platform | Handles structural mechanics, fluid-structure interaction, and poroelasticity [23] [25]. |

| PLGA (poly lactic co-glycolic acid) | Biodegradable polymer for microparticles | FDA-approved; degradation rate tunable by lactic/glycolic acid ratio [25]. |

| PRINT/SEAL Technology | Fabrication of non-spherical microparticles | Enables high-precision particles for controlled release kinetics [25]. |

| Ansys Mechanical | General-purpose FEA solver | Robust capabilities for nonlinear contact and material behavior [22]. |

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: FEA Diagnostics Integration

Diagram 2: Drug Delivery FEA Workflow

Building Integrated Frameworks: Practical Methods for Coupling FEA with AI and Data-Driven Diagnostics

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: In which pharmaceutical development areas can FEA serve as an effective data generator? Finite Element Analysis (FEA) is a computational tool that uses mathematical modeling to simulate complex physical phenomena. It is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical development for generating data in areas where experimental data is scarce, expensive, or ethically challenging to obtain. Key application areas include:

- Transdermal Drug Delivery: Simulating the mechanical interaction between microneedles and skin tissue to predict penetration depth, stress distribution, and potential failure points, thus guiding the precise preparation of microneedles [26].

- Tablet Manufacturing: Modeling the powder compression process to predict critical properties such as density distribution, stress transmission, and tablet strength, which helps in understanding and preventing issues like capping and lamination [27].

- Personalized Medical Devices: Enabling the design of individualized microneedles or other drug delivery systems according to different patient-specific skin parameters [26].

FAQ 2: What are the fundamental steps of the FEA workflow? The FEA workflow is a systematic process that involves several key stages [27]:

- Geometry Creation: Defining the geometry of the system (e.g., tablet, microneedle, skin model) using computer-aided design (CAD).

- Meshing: Discretizing the geometry into a finite number of small elements (a mesh) connected at nodes.

- Applying Boundary Conditions: Imposing constraints, loads, and interface conditions (e.g., friction) on the model.

- Defining Material Properties: Assigning the mechanical properties (e.g., Young’s modulus, Poisson's ratio) of the materials involved.

- Solution: The FEA solver computes the model's response to the applied conditions.

- Validation and Verification: Critically, the simulation results must be compared with any available experimental data to ensure the model's accuracy and reliability.

FAQ 3: How can FEA be integrated with other diagnostic and modeling methods? FEA is most powerful when augmented with other research methods, creating a synergistic workflow:

- Augmented Reality (AR) Visualization: FEA results, such as stress and deformation, can be superimposed onto real-world objects in real-time. This enhances a researcher's perception and interaction with the simulation data, bridging the gap between virtual analysis and physical context [28].

- Explainable AI (XAI) Integration: The data generated by FEA can feed into AI models. Techniques like SHAP (for rule-based feature attribution) and Grad-CAM (for visual heatmaps) can then be applied to make the AI's decision-making process based on FEA data transparent and interpretable for researchers [9].

- Constitutive Material Models: FEA relies on mathematical models to describe material behavior. In pharmaceutical powder compaction, for example, models like the Drucker-Prager Cap (DPC) are often used to represent the yield surfaces of compressed powders [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving FEA Model Convergence Issues

Problem: The FEA solver fails to find a solution, often due to numerical instability.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution & Preventive Action |

|---|---|---|

| Overly Complex Mesh [29] | Perform a mesh sensitivity analysis. Check if elements are excessively distorted. | Use a simpler, higher-quality mesh. Start with a coarser mesh and progressively refine it. |

| Incorrect Material Properties [26] [27] | Verify that material parameters (e.g., Young's modulus, yield strength) are accurate and physically realistic. | Consult scientific literature for validated material properties. Use experimental data to calibrate models [27]. |

| Unrealistic Boundary Conditions or Loads [29] [27] | Review applied constraints, forces, and friction coefficients. Ensure they accurately reflect the real-world scenario. | Simplify boundary conditions where possible. Ensure loads are applied gradually in steps. |

| Insufficient Computational Resources [29] | Monitor memory (RAM) and processor (CPU) usage during the simulation. | Increase system resources or simplify the model geometry and mesh to reduce computational demand. |

Guide 2: Addressing Inaccurate FEA Results

Problem: The FEA simulation runs to completion, but the results do not align with experimental observations or expected physical behavior.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution & Preventive Action |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate Mesh Resolution [27] | Check for high stress/strain gradients in areas with a coarse mesh. Perform a mesh convergence study. | Refine the mesh in critical areas of high stress or complex geometry. Ensure the mesh is fine enough to capture the phenomena of interest. |

| Oversimplified Material Model [27] | Assess if the chosen constitutive model (e.g., linear elastic) adequately captures the material's behavior (e.g., plasticity, time-dependence). | Select a more advanced material model that reflects the actual mechanical behavior, such as the Drucker-Prager Cap model for powder compaction [27]. |

| Poor Model Validation [27] | Compare simulation outputs with any available experimental data from texture analyzers, micromechanical testers, or nanoindenters [26]. | Always validate the FEA model against controlled experimental results before using it for predictive purposes. Iteratively calibrate the model parameters. |

| Ignoring Symmetry [27] | Evaluate if the physical problem and boundary conditions exhibit symmetry. | Use 2D models or symmetric 3D models where appropriate to reduce model complexity and computation time while maintaining accuracy. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: FEA of Microneedle Skin Insertion

Objective: To simulate the mechanical performance of a microneedle during skin insertion to predict its ability to penetrate without failure [26].

Methodology:

- Geometry Modeling: Create a 3D CAD model of the microneedle array and a simplified, multi-layered model of human skin.

- Material Assignment:

- Microneedle: Assign material properties (e.g., Young's modulus, Poisson's ratio) based on the selected polymer, metal, or silicon [26].

- Skin Model: Implement a constitutive material model that reflects the non-linear, hyperelastic behavior of skin tissue.

- Meshing: Use a fine mesh, particularly at the needle tip and skin contact interface, to capture high stress concentrations accurately.

- Boundary Conditions:

- Fix the bottom and sides of the skin model.

- Apply a vertical displacement to the microneedle base to simulate insertion.

- Define a contact pair between the needle and skin with an appropriate friction coefficient.

- Analysis: Run a non-linear, quasi-static structural analysis.

- Outputs: Extract and analyze von Mises stress (to predict material yield) and buckling force (to predict structural failure).

Table 1: Mechanical Properties of Common Microneedle Materials for FEA [26]

| Material | Density (kg/m³) | Young's Modulus (GPa) | Poisson's Ratio | Yield Strength (GPa) | Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon | 2329 | 170 | 0.28 | 7 | Brittle, good stiffness and biocompatibility |

| Titanium | 4506 | 115.7 | 0.321 | 0.1625 | Excellent mechanical properties, low cost |

| Maltose | 1812 | 7.42 | 0.3 | 7.44 | Common FDA-approved excipient, absorbs moisture easily |

| Polycarbonate (PC) | 1210 | 2.4 | 0.37 | 0.070 | Good biodegradability and biocompatibility |

Protocol 2: FEA of Pharmaceutical Powder Compaction

Objective: To predict the stress and density distribution within a powder during the tableting process and the subsequent tablet strength [27].

Methodology:

- Model Setup: Create a 2D axisymmetric or 3D model of the die, punches, and powder bed.

- Powder Material Model: Implement the Drucker-Prager Cap (DPC) plasticity model. This model requires calibration from experimental powder compression data to define its parameters [27].

- Meshing: Use quadrilateral elements for the powder bed. A finer mesh is often used in the powder to resolve density variations.

- Boundary Conditions & Loads:

- Apply a vertical displacement to the upper punch to simulate compression. The lower punch can be fixed or moved accordingly.

- Fix the die walls.

- Apply a constant friction coefficient at the powder/tooling interfaces (typical μ values range from 0.1 to 0.35) [27].

- Analysis Steps: Simulate the compression phase, followed by decompression and ejection.

- Outputs: Analyze the relative density distribution and stress field (axial and radial) in the compacted powder. For the final tablet, simulate a diametral compression test to predict tensile strength and identify potential failure zones.

Visual Workflows

FEA Data Generation Process

FEA Augmentation with Other Methods

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for FEA-Informed Pharmaceutical Development

| Item & Function | Example Use-Case in FEA Context |

|---|---|

| Polymer Matrix Materials (e.g., Maltose, Polycarbonate): Biocompatible materials used to fabricate drug-loaded microneedles [26]. | Their mechanical properties (Young's Modulus, yield strength) are critical input parameters for FEA simulations predicting microneedle penetration and structural integrity [26]. |

| Constitutive Material Models (e.g., Drucker-Prager Cap Model): Mathematical models that describe the yield and flow behavior of materials under stress [27]. | Essential for simulating the complex behavior of pharmaceutical powders during compaction in FEA, enabling prediction of density variations and tablet strength [27]. |

| Texture Analyzer / Micromechanical Tester: Instruments used to experimentally measure the mechanical strength of materials and small structures [26]. | Provides critical experimental data for validating FEA models of microneedle fracture force or tablet hardness, ensuring simulation accuracy [26]. |

| Wireless Sensor Network (WSN): A system of sensors to acquire spatially distributed load data in real-world environments [28]. | Can be integrated with AR-FEA systems to provide real-time, actual load data as input for simulations, moving from assumed to measured boundary conditions [28]. |

| Augmented Reality (AR) Platform: A system that superimposes computer-generated information onto the user's view of the real world. | Used to visualize FEA results (e.g., stress contours) directly onto the corresponding physical object, enhancing interpretation and interaction [28]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Data Visualization Issues in Digital Twin Explorer

Problem: Entity instances and time series data are missing from the explorer view after mapping data to entity instances [30].

Diagnosis & Resolution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Check the Manage operations tab to verify the status of mapping operations [30]. | Identify if any mapping operations have failed. |

| 2 | If failures are found, rerun the operations. Execute failed non-time series operations first, followed by time series operations [30]. | All mapping operations show a status of "Succeeded". |

| 3 | If operations are successful but data is missing, check the associated SQL endpoint provisioning. The SQL endpoint for your digital twin's data lakehouse is typically named after your digital twin instance followed by "dtdm" and is located at the root of your workspace [30]. | The SQL endpoint is active and accessible. |

| 4 | If no SQL endpoint exists, the lakehouse may have failed to provision correctly. Follow your platform's prompts to recreate the SQL endpoint [30]. | The SQL endpoint is successfully reprovisioned, and data becomes visible in the explorer. |

Entity Instances Missing Time Series Data

Problem: An entity instance is visible in the Explore view, but its Charts tab is empty and lacks time series data [30].

Diagnosis & Resolution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify the execution order of mappings. The time series mapping may have run before the non-time series mapping was complete [30]. | Confirm the correct sequence of operations. |

| 2 | Create a new time series mapping using the same source table and run it with incremental mapping disabled [30]. | The Charts tab populates with the correct time series data. |

| 3 | In the time series mapping configuration, meticulously verify that the "Link with entity" property fields exactly match the corresponding entity type property values. Redo the mapping if discrepancies are found [30]. | A perfect match is achieved between the link property and the entity type property. |

General Operation Failures

Problem: Operations show a "Failed" status in the Manage operations tab [30].

Diagnosis & Resolution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Select the "Details" link for the failed operation [30]. | The operation details view opens. |

| 2 | Navigate to the "Runs" tab to inspect the run history and identify the specific flow that failed (e.g., an on-demand run or a scheduled flow) [30]. | The specific failed job is identified. |

| 3 | Select the "Failed" status to view the detailed error message [30]. | The root cause of the failure is revealed. |

| 4 | For the error "Concurrent update to the log. Multiple streaming jobs detected for 0", simply rerun the mapping operation, as this is caused by concurrent execution [30]. | The operation completes successfully on retry. |

| 5 | If the failure message is empty, prepare to create a support ticket. Have the job instance ID ready, which can be found in the Monitor hub by adding the "Job Instance ID" column [30]. | Support can be effectively contacted with the necessary information. |

Authentication and API Issues

Problem: "400 Client Error: Bad Request" when using Azure Digital Twins commands in Cloud Shell [31].

Diagnosis & Resolution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Run az login in Cloud Shell and complete the login steps. This switches the session from managed identity authentication [31]. |

Authentication is re-established. |

| 2 | Alternatively, perform your Cloud Shell work directly from the Azure portal's Cloud Shell pane [31]. | The command executes without authentication errors. |

Problem: "Azure.Identity.AuthenticationFailedException" when using InteractiveBrowserCredential or DefaultAzureCredential in application code [31].

Diagnosis & Resolution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Update your application to use a newer version of the Azure.Identity library (post-1.2.0 for InteractiveBrowserCredential issues) [31]. |

The browser authentication window loads and authenticates correctly. |

| 2 | For DefaultAzureCredential issues in version 1.3.0, instantiate the credential while excluding the problematic credential type: new DefaultAzureCredential(new DefaultAzureCredentialOptions { ExcludeSharedTokenCacheCredential = true }) [31]. |

The AuthenticationFailedException related to SharedTokenCacheCredential is resolved. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core architectural framework of a Digital Twin system? A1: A Digital Twin is a virtual representation of a physical object or system that serves as its real-time digital counterpart. The most widely accepted conceptual model consists of three core parts [32]:

- Physical Entity: The real-world asset (e.g., machinery, equipment).

- Virtual Entity: The digital representation created in a virtual environment.

- Data Connection: The bidirectional link that integrates data from the physical entity to the virtual model and can feed back insights or commands.

Q2: How can Finite Element Analysis (FEA) be integrated with a Digital Twin for diagnostics? A2: FEA provides a powerful numerical simulation method for analyzing structural dynamics. When addended with a Digital Twin, the traditional offline FEA process is transformed [33] [34]:

- Offline FEA: Used for preliminary design and creating a high-fidelity baseline model of the physical asset.

- Digital Twin Integration: Real-time sensor data from the physical entity is used to calibrate and update the FEA model. This allows for in-situ observation and visualization of internal forces and stress distributions, enabling diagnosis based on the asset's current "as-is" condition rather than just its original design [33].

Q3: What are common computational challenges when building a Digital Twin for complex systems like high-voltage switchgear, and how can they be addressed? A3: High-fidelity 3D models with multi-physics coupling (e.g., thermal-electric-flow fields) result in high computational latency, which hinders real-time simulation. A solution is the creation of a reduced-order surrogate model [34]. This involves:

- Mesh Coarsening: Reducing the number of elements in the simulation mesh.

- Dictionary Tree Deduplication: Compressing node data by eliminating redundant spatial nodes.

- Algorithm Application: Using methods like K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) to reconstruct field data (e.g., temperature, stress) on the reduced-dimensional nodes, maintaining accuracy while drastically improving simulation speed for online diagnostics [34].

Q4: My Digital Twin explorer cannot connect to an instance that uses a private endpoint. What should I do? A4: Some out-of-the-box explorer tools do not support private endpoints. You have two main options [31]:

- Deploy a Private Explorer: Deploy your own instance of the explorer codebase privately in your cloud environment.

- Use APIs/SDKs: Alternatively, manage your Digital Twin instance directly through the provided APIs and SDKs, which offer more configuration flexibility.

Q5: How can color usage in diagnostic visualizations be made accessible? A5: To ensure that information is not conveyed by color alone, which is critical for users with color vision deficiencies, follow these guidelines [35]:

- Do Not Rely on Color Alone: Use color to enhance information, but pair it with text labels, patterns, or icons. For example, in a graph, use different line styles (solid, dashed) and add text labels directly to the data series.

- Ensure Sufficient Contrast: The visual presentation of text and interactive elements should have a minimum contrast ratio of 4.5:1 against the background (3:1 for large text) to ensure readability for users with low vision [35].

Experimental Protocols & Visualization

Protocol: Constructing a Reduced-Order Surrogate Model for Real-Time FEA

Purpose: To create a lightweight Digital Twin surrogate model that enables real-time thermal-electric field simulation for high-voltage switchgear diagnostics [34].

Methodology:

- High-Fidelity FEA Modeling:

- Construct a detailed 3D model of the asset (e.g., KYN28-12(Z) switchgear).

- Perform coupled multi-physics FEA (thermal-electric-flow) to generate a high-resolution dataset of field distributions under various conditions [34].

- Dimensionality Reduction:

- Mesh Coarsening: Traverse the fine simulation mesh and generate a coarser mesh, significantly reducing the number of nodes while aiming to maintain field extreme value errors below 5% [34].

- Dictionary Tree Deduplication: Map all nodes from the coarse mesh into a three-layer tree structure. This process eliminates redundant nodes by covering duplicate data, further compressing the dataset [34].

- Surrogate Model Development:

- Use a K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) algorithm to reconstruct field values on the reduced-dimensional nodes.

- For a test node ( xi ), find its ( K ) nearest neighbors ( {X{ik}} ) in the original dataset using Euclidean distance [34]: (d({Xj},{xi}) = \sqrt{({Xj}x - {xi}x)^2 + ({Xj}y - {xi}y)^2 + ({Xj}z - {xi}z)^2})

- Estimate the field attribute (e.g., temperature) of ( xi ) using the inverse distance-weighted mean of its neighbors' values [34]: ( {xi} = (\sum{j=1}^k {\omegaj \cdot {X{i+j}})/(\sum{j=1}^k {\omegaj}} ),\ \text{where}\ \omegaj = 1/d({Xj},{xi}) )

Workflow Diagram for Digital Twin-Assisted Diagnosis

Diagram Title: Digital Twin Diagnosis Workflow

Protocol: MR-Enabled In-Situ FEA for Structural Diagnosis

Purpose: To enable on-site, real-time Finite Element Analysis of critical structural components by integrating FEA tools with Mixed Reality (MR) for intuitive visualization and safety diagnosis [33].

Methodology:

- Spatial Parameter Acquisition:

- Use Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS) and Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) to acquire a point cloud model of the structure and its environment in a global coordinate system.

- Apply parameter estimation methods to extract the spatial parameters of the structural components [33].

- FEA Modeling in Unity Engine:

- Develop pre-processing, solving, and post-processing modules within the Unity 3D engine.

- Use the spatial parameters to form virtual structural components as FEA models [33].

- Virtual-Real Calibration and Visualization:

- Use the in-situ coordinates of the real structural components as the spatial anchor for the MR device (e.g., HoloLens 2).

- Superimpose the real-time FEA results (e.g., stress distributions, deformations) generated by the MR device's computing power onto the engineer's view of the real structure through the MR headset [33].

- This creates an intuitive visual perspective of internal forces, enhancing the engineer's perception and enabling agile structural safety diagnosis on-site [33].

Diagram: Multi-Physics Coupling in Switchgear Digital Twin

Diagram Title: Multi-Physics Coupling in Switchgear

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Components for a Digital Twin Diagnostic System

| Category | Item / Technique | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Modeling & Simulation | Finite Element Analysis (FEA) | A numerical method for simulating physical phenomena (e.g., stress, heat transfer) to create a high-fidelity virtual baseline model of the physical asset [33] [34]. |

| Reduced-Order Surrogate Model | A simplified, computationally efficient version of a complex model that approximates its key behaviors, enabling real-time simulation within the Digital Twin [34]. | |

| Lumped Parameter Models | A dynamic modeling approach that simplifies a distributed system into a network of discrete elements, useful for representing bearing and gear systems in rotating machinery [32]. | |

| Data Processing & Algorithms | K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) | A lazy learning algorithm used for reconstructing field data on reduced-dimensional nodes in surrogate models; valued for its simplicity and robustness to outliers [34]. |

| Mesh Coarsening & Dictionary Tree Deduplication | Data compression techniques used to reduce the number of nodes in a finite element model while preserving critical information, crucial for achieving real-time performance [34]. | |

| Adaptive Neural-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) | A hybrid intelligent system that combines neural network learning capabilities with the interpretability of fuzzy logic, used for intelligent fault diagnosis [34]. | |

| Optimal Classification Tree (OCT) | An interpretable machine learning algorithm used for fault classification, especially under conditions of high feature entanglement [34]. | |

| Hardware & Sensing | Mixed Reality (MR) Device (e.g., HoloLens 2) | A wearable computer that enables the overlay of interactive digital content (like FEA results) onto the user's view of the real world, facilitating in-situ observation and diagnosis [33]. |

| Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS) | A remote sensing technology used to capture precise 3D spatial data (point clouds) of structures and environments for accurate virtual model creation [33]. | |

| Communication & Integration | OPC UA (Unified Architecture) | A platform-independent, service-oriented communication protocol used for secure, reliable, and standardized data exchange between physical devices and the Digital Twin model [36]. |

| Local-Loop Communication Protocol | A custom-designed protocol for enabling dynamic visualization and efficient, low-latency data transfer within a closed diagnostic system [34]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

Q1. My surrogate model has poor accuracy on new FEA data. What should I check? A1. This is often a data mismatch or model configuration issue. Focus on these areas:

- Data Similarity and Volume: Verify that your FEA dataset shares features (e.g., geometry, material properties, boundary conditions) with the data the pre-trained model was originally trained on. The required model adaptation strategy depends heavily on this similarity and your dataset size [37].

- Fine-Tuning Strategy: If data is similar but your dataset is small, you may be fine-tuning too many layers. Try freezing all pre-trained layers initially and only training a new, task-specific output layer. Gradually unfreeze higher-level layers if performance is insufficient [38] [37].

- Input Data Preprocessing: Ensure your FEA data (e.g., mesh geometries, stress fields) is preprocessed to match the input specifications (size, normalization, etc.) of the original pre-trained model [37].

Q2. The training process is slow, and computational costs are high. How can I improve efficiency? A2. Optimize your workflow using these methods:

- Leverage Pre-Trained Features: Initially, use the pre-trained model as a fixed feature extractor. This allows you to convert your FEA datasets into feature vectors offline, avoiding backpropagation through the entire network during initial training cycles [37].

- Adopt Reduced-Order Modeling (ROM): Integrate techniques like Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD) to compress your high-dimensional FEA data into a compact, lower-dimensional representation before feeding it into the ML model. This drastically reduces the input size and computational load [39].

- Implement a Hybrid Modeling Pipeline: Use the ML surrogate model for rapid design iterations and sensitivity analysis. Reserve full-scale FEA simulations only for final validation of critical design points, thus reducing the number of expensive solver calls [39].

Q3. My model's predictions are physically inconsistent or violate known constraints. A3. This indicates a need to better integrate physical principles into the model.

- Incorporate Physics-Informed Loss Functions: Move beyond standard loss functions. Use a composite loss that penalizes violations of the governing partial differential equations (PDEs). For a displacement field