Beyond Microscopy: Advancing Entamoeba histolytica Diagnosis with High-Specificity Antigen Tests

Accurate differentiation of pathogenic Entamoeba histolytica from non-pathogenic Entamoeba dispar is critical for appropriate treatment and avoiding undue therapy.

Beyond Microscopy: Advancing Entamoeba histolytica Diagnosis with High-Specificity Antigen Tests

Abstract

Accurate differentiation of pathogenic Entamoeba histolytica from non-pathogenic Entamoeba dispar is critical for appropriate treatment and avoiding undue therapy. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the specificity and performance of modern antigen detection tests compared to traditional microscopy. We explore the foundational limitations of microscopy, detail the methodological principles of ELISA and rapid immunochromatographic tests, address troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and present rigorous validation data against molecular standards like PCR. The synthesis of current evidence underscores that antigen tests offer a significant leap in diagnostic specificity, enabling precise species identification that is essential for clinical management and pharmaceutical development.

The Diagnostic Imperative: Why Microscopy Fails to Distinguish Pathogenic Entamoeba Species

Entamoeba histolytica, Entamoeba dispar, and Entamoeba moshkovskii present a significant diagnostic challenge in clinical parasitology. These three species are morphologically identical in both cyst and trophozoite forms during microscopic examination of stool specimens, yet they differ dramatically in their clinical significance. E. histolytica represents a potent pathogen capable of causing invasive amebiasis, while E. dispar is generally considered non-pathogenic, and E. moshkovskii occupies an ambiguous position with emerging evidence suggesting potential pathogenicity. This morphological convergence has profound implications for patient management, as it can lead to both unnecessary treatment for those harboring non-pathogenic species and dangerous delays in treatment for those with true E. histolytica infections. This review comprehensively compares the performance of traditional microscopy against modern antigen and molecular detection methods, providing experimental data and protocols that highlight the critical need for species-specific diagnostic approaches in both clinical and research settings.

The genus Entamoeba contains multiple species that colonize the human intestinal lumen, but only E. histolytica is definitively associated with pathological sequelae including amebic dysentery and liver abscesses [1]. The World Health Organization recognizes amebiasis as a neglected tropical disease causing approximately 100,000 deaths annually worldwide [1] [2]. The fundamental diagnostic challenge stems from the fact that microscopic examination – the traditional mainstay of parasite diagnosis – cannot differentiate between these morphologically identical species [3] [4].

This diagnostic limitation has significant clinical consequences. Without species-specific testing, patients infected with non-pathogenic species may undergo unnecessary treatment with anti-amebic drugs, while those with E. histolytica may not receive prompt appropriate therapy [3]. Studies have demonstrated that when microscopy alone is used for diagnosis, a substantial proportion of positive findings represent non-pathogenic species. Research from India showed that only 60% (9/15) of microscopy-positive samples were confirmed as E. histolytica by antigen testing, meaning 40% of patients would have received unnecessary treatment if managed based on microscopy alone [3].

The epidemiological distribution of these species further complicates the diagnostic picture. Worldwide, E. dispar infections are approximately ten times more common than E. histolytica [1], though this ratio varies by region. The status of E. moshkovskii continues to evolve, with recent studies reporting it as the sole potential enteropathogen in patients presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms, suggesting it may have underestimated pathogenic potential [1] [2].

Comparative Performance of Diagnostic Methods

Microscopy: The Traditional Gold Standard with Limitations

Microscopic identification of Entamoeba species relies on the examination of stool specimens using direct wet mounts, concentration techniques, and permanent staining. The formalin-ethyl acetate concentration technique (FECT) followed by trichrome or hematoxylin staining is commonly employed to visualize characteristic cysts and trophozoites [5] [6].

E. histolytica, E. dispar, and E. moshkovskii cysts typically measure 12-15 μm in diameter and contain 1-4 nuclei when mature, with characteristic centrally located karyosomes and fine, uniformly distributed peripheral chromatin [4]. Chromatoid bodies with blunt, rounded ends may be visible. Trophozoites of these species measure 15-20 μm (range 10-60 μm) and display a single nucleus with a centrally placed karyosome and granular "ground-glass" cytoplasm [4].

The primary limitation of microscopy is its inability to differentiate species within this complex. While erythrophagocytosis (ingestion of red blood cells) has been classically associated with E. histolytica, this finding is not entirely reliable as it may rarely occur with E. dispar [4]. Additionally, microscopy sensitivity is suboptimal, ranging from 50-60% for intestinal infection to less than 30% for extraintestinal infection [7].

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Microscopy for Entamoeba Detection

| Parameter | Performance | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 50-60% (intestinal), <30% (extraintestinal) [7] | Low sensitivity requires examination of multiple samples |

| Specificity | Cannot be determined for species differentiation | Morphologically identical species cannot be distinguished |

| Species Differentiation | Not possible | E. histolytica, E. dispar, E. moshkovskii appear identical |

| Turnaround Time | 1-2 hours for direct exam | Time-consuming concentration methods add processing time |

| Expertise Required | High | Requires experienced technologist for accurate morphology |

Antigen Detection: Species-Specific Immunoassays

Antigen detection assays represent a significant advancement in species differentiation by targeting E. histolytica-specific proteins. The TechLab E. histolytica II ELISA detects the galactose/N-acetylgalactosamine-inhibitable lectin (Gal/GalNAc lectin), an adhesin specific to E. histolytica trophozoites [7]. This 96-well microplate format provides results within approximately 2.5 hours.

The diagnostic performance of antigen detection represents a substantial improvement over microscopy. Studies demonstrate the TechLab ELISA test has 89-100% sensitivity and 95-100% specificity for detecting E. histolytica [3] [7]. Comparative research revealed that while microscopy detected 15 samples positive for the Entamoeba complex, only 9 (60%) were confirmed as E. histolytica by ELISA, demonstrating the limited specificity of microscopy [3].

Table 2: Performance Comparison: Microscopy vs. Antigen Detection

| Diagnostic Method | Sensitivity for E. histolytica | Specificity for E. histolytica | Species Differentiation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopy | 47.3% [3] | 95.9% [3] | Cannot differentiate E. histolytica from E. dispar/E. moshkovskii [7] |

| Antigen Detection (ELISA) | 89-100% [7] | 95-100% [7] | Specific for E. histolytica [7] |

Limitations of Antigen Detection: While a marked improvement over microscopy, antigen testing has important limitations. The TechLab ELISA detects trophozoite antigens but does not detect the cyst form of E. histolytica, potentially missing asymptomatic cyst carriers or residual carriage following treatment [7]. The test has also not been extensively validated against E. moshkovskii or the more recently described E. bangladeshi [7]. Proper specimen handling is critical, as specimens submitted in sodium acetate-acetic acid-formalin (SAF) preservative are not suitable for antigen testing [7].

Molecular Methods: The New Reference Standard

Molecular methods based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology represent the most sensitive and specific approach for differential detection of Entamoeba species. Both conventional and real-time PCR assays have been developed, primarily targeting the small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) gene [8] [7] [9].

The superior performance of PCR is demonstrated in multiple studies. A 2019 study from Iran using nested multiplex PCR successfully differentiated Entamoeba species in clinical samples, identifying E. dispar (0.58%), E. histolytica (0.14%), E. moshkovskii (0.07%), and mixed infections (0.22%) [5]. Research in Malaysia applying nested PCR to microscopy-positive samples revealed that E. histolytica (75.0%) was the most common species, followed by E. dispar (30.8%) and E. moshkovskii (5.8%), with mixed infections in 11.5% of cases [2].

Table 3: Performance Characteristics of Molecular Methods for Entamoeba Detection

| Parameter | Conventional PCR | Real-Time PCR | Multiplex PCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 10-20 pg DNA [8] | >90% [7] | 89.7-95% [10] |

| Specificity | 100% (species-specific) [8] | >90% [7] | 96.9-100% [10] |

| Turnaround Time | 6-8 hours | 2-3 hours | 2-3 hours |

| Species Differentiated | E. histolytica, E. dispar, E. moshkovskii [8] | E. histolytica, E. dispar [7] | E. histolytica, E. dispar/E. moshkovskii [10] |

| Detection of Mixed Infections | Yes [5] | Limited | Yes [10] |

Molecular methods demonstrate particular value in detecting mixed infections that would be impossible to identify by microscopy. The Iranian study found 0.22% of samples contained mixed E. histolytica and E. dispar infections [5], while the Malaysian study identified mixed infections in 11.5% of positive samples [2]. This capability has important implications for understanding transmission dynamics and disease pathogenesis.

Experimental Protocols for Differential Detection

Nested Multiplex PCR Protocol

The nested multiplex PCR protocol described by Khademvatan et al. (2019) provides a robust method for simultaneous detection and differentiation of all three Entamoeba species [5].

DNA Extraction:

- Wash approximately 300 μl of fecal specimen three times with triple-distilled water via centrifugation to remove alcohol preservatives

- Extract genomic DNA using commercial stool DNA isolation kits (e.g., FavorPrep Stool DNA Isolation Mini Kit)

- Include a mechanical disruption step: freeze samples in liquid nitrogen and thaw at 90°C in a water bath

- Elute DNA in 50 μl of elution buffer and store at -20°C until PCR amplification

First Round PCR Amplification:

- Use primers E-1 (5'-TAAGATGCACGAGAGCGAAA-3') and E-2 (5'-GTACAAAGGGCAGGGACGTA-3')

- Reaction volume: 25 μl containing 12.5 μl of 2X PCR master mix, 15 ρM of each primer, and 10 ng of extracted DNA

- Amplification conditions: 95°C for 5 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 30s, 58°C for 30s, 72°C for 30s; final extension at 72°C for 5 min

Second Round Nested Multiplex PCR:

- Use species-specific primers in a multiplex reaction:

- E. histolytica: EH-1 (5'-AAGCATTGTTTCTAGATCTGAG-3') and EH-2 (5'-AAGAGGTCTAACCGAAATTAG-3') → 439 bp product

- E. moshkovskii: Mos-1 (5'-GAAACCAAGAGTTTCACAAC-3') and Mos-2 (5'-CAATATAAGGCTTGGATGAT-3') → 553 bp product

- E. dispar: ED-1 (5'-TCTAATTTCGATTAGAACTCT-3') and ED-2 (5'-TCCCTACCTATTAGACATAGC-3') → 174 bp product

- Reaction volume: 30 μl containing 15 μl of 2X PCR master mix, 15 ρM of each primer, and 10 ng of first PCR product

- Amplification conditions: 35 cycles of 94°C for 30s, 55°C for 30s, 72°C for 30s with initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min and final extension at 72°C for 5 min

Product Detection:

- Electrophorese 3 μl of PCR products on 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide

- Visualize under UV light and compare product sizes to positive controls

Single-Round Multiplex PCR Assay

Hamzah et al. (2006) developed a single-round PCR assay that reduces processing time while maintaining specificity [8].

Primer Design:

- Forward primer (EntaF): 5'-ATGCACGAGAGCGAAAGCAT-3' (conserved region)

- Species-specific reverse primers:

- EhR: 5'-GATCTAGAAACAATGCTTCTC-3' for E. histolytica (166 bp product)

- EdR: 5'-CACCACTTACTATCCCTACC-3' for E. dispar (752 bp product)

- EmR: 5'-TGACCGGAGCCAGAGACAT-3' for E. moshkovskii (580 bp product)

PCR Reaction:

- Reaction volume: 50 μl containing 200 μM of each dNTP, 0.1 μM of each primer, 6 mM MgCl₂, 0.5 U of Taq polymerase, 1X Taq buffer, and 10 μl of extracted DNA

- Amplification conditions: 94°C for 3 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 58°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min; final extension at 72°C for 7 min

Sensitivity and Specificity:

- Sensitivity: 10 pg of E. moshkovskii and E. histolytica DNA, 20 pg of E. dispar DNA

- No cross-reaction with other intestinal pathogens including E. coli, Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Giardia lamblia, or Cryptosporidium spp.

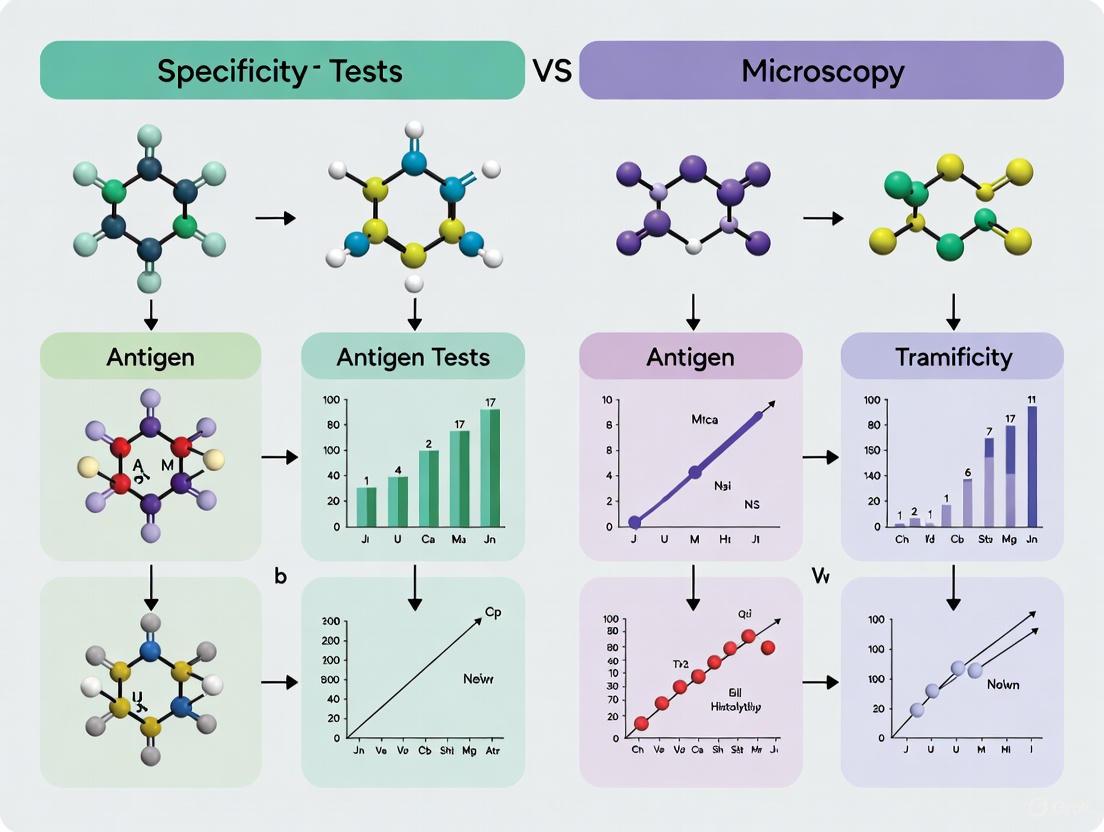

The following diagram illustrates the key decision pathways in laboratory diagnosis of Entamoeba species:

Diagnostic Workflow for Entamoeba Species

Real-Time PCR Assays

Recent advances in real-time PCR technology offer quantitative detection with enhanced sensitivity. The ParaGENIE G-Amoeba multiplex real-time PCR assay simultaneously detects Giardia intestinalis, E. histolytica, and E. dispar/E. moshkovskii from stool specimens [10]. Evaluation of this CE-IVD-marked assay demonstrated sensitivity of 89.7% and specificity of 96.9% for G. intestinalis, and 95% sensitivity with 100% specificity for E. dispar/E. moshkovskii detection [10].

Comparative studies of three different real-time PCR assays for E. histolytica demonstrated diagnostic sensitivity estimates ranging from 75% to 100% and specificity from 94% to 100% [9]. These performance variations highlight the importance of regional validation before implementing molecular assays in different laboratory settings.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Entamoeba Differentiation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Strains | E. histolytica HM-1:IMSS, E. dispar SAW760, E. moshkovskii Laredo [5] [8] | Positive controls for assay development and validation |

| DNA Extraction Kits | FavorPrep Stool DNA Isolation Kit [5], QIAamp Stool DNA Kit [8] | Nucleic acid purification from complex stool matrices |

| PCR Master Mixes | Ampliqon 2X PCR Master Mix [5] | Optimized enzyme/buffer systems for amplification |

| Species-Specific Primers | SSU rRNA gene-targeting primers [5] [8] | Amplification of diagnostic gene targets |

| Commercial Antigen Kits | TechLab E. histolytica II ELISA [3] [7] | Detection of E. histolytica-specific Gal/GalNAc lectin |

| Stool Preservatives | SAF (sodium acetate-acetic acid-formalin) [7], 70% ethanol [5], 2.5% potassium dichromate [2] | Sample preservation for morphology and molecular studies |

| Electrophoresis Reagents | Agarose, ethidium bromide, DNA size markers [5] [8] | Visualization and confirmation of PCR products |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The morphological conundrum presented by identical cysts of E. histolytica, E. dispar, and E. moshkovskii continues to challenge both clinicians and researchers. While microscopy remains widely available and inexpensive, its limitations necessitate the implementation of species-specific diagnostic methods in settings where accurate differentiation impacts clinical management.

The body of evidence supports molecular methods as the superior approach for differential diagnosis, epidemiological studies, and understanding the true prevalence of these organisms. PCR-based methods offer the highest sensitivity and specificity, plus the ability to detect mixed infections [5] [2]. However, practical considerations including cost, technical expertise, and infrastructure may make antigen detection a more feasible option in some resource-limited settings where amebiasis is endemic.

Emerging research questions continue to evolve. The pathogenic potential of E. moshkovskii requires further investigation, as recent studies have associated this species with gastrointestinal symptoms in the absence of other pathogens [1] [2]. The discovery of E. bangladeshi adds another dimension to this complex, though specific diagnostic tools for this species are not yet widely available [7].

Future directions should focus on developing point-of-care molecular tests that combine the specificity of PCR with the rapidity and simplicity of antigen tests. Additionally, more comprehensive epidemiological studies using molecular methods are needed to better understand the global distribution and disease burden of these organisms. The scientific community would benefit from standardized reference materials and international proficiency testing programs to ensure consistency in detection and differentiation methods across laboratories worldwide.

The morphological identity of E. histolytica, E. dispar, and E. moshkovskii cysts represents a significant diagnostic challenge with direct clinical implications. While microscopy can detect the presence of Entamoeba organisms, it cannot differentiate pathogenic from non-pathogenic species. Antigen detection methods provide a practical solution for specific identification of E. histolytica in many clinical settings. However, molecular methods, particularly PCR-based approaches, represent the current gold standard for differential diagnosis, offering superior sensitivity, specificity, and the ability to detect mixed infections. As research continues to elucidate the complex relationships between these organisms and human disease, accurate differentiation remains fundamental to appropriate patient management, epidemiological understanding, and drug development efforts.

Accurate diagnosis of Entamoeba histolytica infection represents a critical challenge in clinical practice, with significant ramifications for patient outcomes and public health. The parasitic disease amebiasis, caused by E. histolytica, remains the second leading cause of death from parasitic infections worldwide [11]. The diagnostic dilemma stems primarily from the morphological similarity between the pathogenic E. histolytica and non-pathogenic species such as E. dispar and E. moshkovskii, which appear identical under conventional microscopic examination [3] [7]. This limitation has profound implications for clinical management, as the treatment imperative for E. histolytica differs substantially from the non-pathogenic Entamoeba species that colonize the human intestinal tract.

The clinical consequences of diagnostic uncertainty manifest in two primary directions: unnecessary treatment of patients with non-pathogenic Entamoeba species, and failure to identify true E. histolytica infections, leading to missed treatment and potential severe complications. Studies indicate that microscopy alone cannot reliably distinguish between these species, with significant false positive rates for E. histolytica [12]. In one analysis of 90 patients diagnosed with E. histolytica/E. dispar by microscopy, antigen testing confirmed E. histolytica in only 37.8% of cases, suggesting that 62.2% would have received unnecessary treatment if relying solely on microscopic diagnosis [12].

This article examines the clinical consequences of misdiagnosis through a comparative lens, evaluating the specificity of antigen tests versus traditional microscopy for E. histolytica detection. By synthesizing experimental data and clinical outcomes, we provide evidence-based guidance for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working to improve diagnostic accuracy and patient management in amebiasis.

Background: The Diagnostic Challenge

The Morbidity and Mortality of Amebiasis

Entamoeba histolytica infection begins with the ingestion of cysts, typically through fecally contaminated water or food. In the small bowel, excystation occurs with the formation of mobile and invasive trophozoites that aggregate in the intestinal mucin layer, destroying colonic epithelium [11]. Approximately 90% of infections are self-limiting and asymptomatic, with spontaneous clearance of infection. However, in the remaining 10% of cases, symptoms can include abdominal pain, watery and/or bloody diarrhea, weight loss, fever, and anemia [11]. Complications such as toxic megacolon, perianal ulceration, and colonic perforation are described, with extraintestinal complications arising secondary to hematogenous spread to sites including the liver, brain, and lungs [11].

The global significance of amebiasis is substantial, with an estimated 50 million people affected worldwide and 40,000-100,000 deaths annually [3]. E. histolytica is endemic to India, Southeast Asia, Egypt, and Mexico, with high-risk populations including indigenous communities in endemic areas, immigrants, residents returning from endemic countries, and men who have sex with men [11]. The potential for local transmission outside endemic regions was illustrated in a case series from Melbourne, Australia, where one patient acquired E. histolytica despite no domestic or international travel [11].

The Spectrum of Misdiagnosis

The clinical presentation of amebic colitis is varied, leading to frequent misdiagnosis as other gastrointestinal conditions. Case reports and series consistently demonstrate that amebic colitis often masquerades as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), bacterial colitis, or colorectal cancer [11] [13]. This diagnostic confusion can have severe consequences, particularly when corticosteroids are administered for suspected IBD in undiagnosed amebiasis, potentially triggering fulminant disease [14].

The consequences of misdiagnosis operate in both directions. False positive diagnoses of E. histolytica lead to unnecessary treatment with antimicrobials, potential medication side effects, and unnecessary costs. Conversely, false negative diagnoses result in missed infections, delayed treatment, and progression to invasive disease including amebic colitis, liver abscesses, and other extraintestinal complications [11] [14].

Comparative Diagnostic Performance

Diagnostic Methods and Their Specific Limitations

Microscopy

Microscopic examination of stool specimens remains the most common first-line investigation for intestinal amebiasis, particularly in resource-limited settings. The method involves direct visualization of cysts or trophozoites in fresh stool samples, often using saline-Lugol method after formol-ether concentration techniques [3]. However, microscopy cannot distinguish E. histolytica from morphologically identical non-pathogenic species such as E. dispar, E. moshkovskii, and E. bangladeshi [7]. Some microscopic findings—like hematophagy (ingestion of red blood cells by trophozoites)—are more commonly associated with E. histolytica, but these findings are not exclusive and may occasionally appear in non-pathogenic species [7].

The sensitivity of microscopy is suboptimal, ranging from 25-60% for intestinal infection and falling below 30% for extraintestinal infection [11] [7]. This limited sensitivity is attributed to intermittent shedding of organisms in feces, requiring examination of multiple specimens collected over several days to improve detection rates. Performance characteristics are further compromised by requirements for immediate specimen processing and examiner expertise.

Antigen Detection Tests

Antigen detection methods utilize enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) or other immunoassays to detect E. histolytica-specific proteins in stool or other clinical specimens. These tests target specific antigens such as the galactose/N-acetylgalactosamine-binding lectin (Gal/GalNAc lectin or adhesin), which is expressed on the surface of E. histolytica trophozoites [7]. Commercial kits including the Techlab E. HISTOLYTICA II test provide species-specific detection, successfully differentiating E. histolytica from non-pathogenic Entamoeba species [3] [7].

The sensitivity of antigen testing in feces is approximately 90%, with specificity exceeding 80% [11] [7]. A critical limitation is that these assays detect trophozoite antigens but do not identify the cyst form of E. histolytica, potentially missing asymptomatic cyst carriers or residual carriage following treatment targeted at trophozoites [7]. Additionally, some antigen tests have not been validated for extraintestinal specimens or thoroughly evaluated with E. moshkovskii and E. bangladeshi [7].

Molecular Methods

Molecular diagnostics utilizing polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays represent the most advanced approach for specific identification of E. histolytica. These methods typically target species-specific genetic sequences such as the small subunit ribosomal RNA gene or specific episomal repeats [3] [7]. PCR offers superior sensitivity (reportedly >90%) and specificity (>90%) compared to other methods, and can distinguish E. histolytica from non-pathogenic species with high accuracy [11] [7].

Limitations of PCR include higher cost, requirements for specialized equipment and technical expertise, and limited validation on extraintestinal specimens. Additionally, performance characteristics vary between different PCR assays and laboratory implementations, with some reference laboratories still establishing validation data for their specific test protocols [7].

Serological Methods

Serologic testing detects antibodies against E. histolytica in serum, with detection possible in 70-90% of individuals with acute invasive infection within 5-7 days [11]. While valuable for extraintestinal amebiasis, serology has limited utility for intestinal infections in endemic areas where antibody persistence from previous exposures complicates interpretation [7]. A significant limitation is the inability to differentiate acute from previous infections, reducing its utility in endemic settings [11].

Recent advances in serologic testing include the development of rapid gradient-based digital immunoassay systems that use recombinant Igl-C fragments to capture specific anti-Igl-C antibodies in serum. This emerging technology reportedly provides results within 15 minutes with heightened diagnostic sensitivity and specificity, offering potential for point-of-care testing [15].

Experimental Comparison Data

Head-to-Head Method Comparisons

Multiple studies have directly compared the performance of diagnostic methods for E. histolytica identification. A comprehensive study comparing microscopy, antigen testing, and serology in 90 patients initially diagnosed with E. histolytica/E. dispar by microscopy revealed striking differences in confirmation rates [12]. When tested by additional methods, the presence of E. histolytica was not confirmed in 31.1% of cases by trichrome staining, 62.2% by the Wampole antigen test, 64.4% by the Serazym antigen test, 73.3% by indirect hemagglutination test, and 75.6% by latex agglutination [12].

Another study comparing microscopy versus ELISA for E. histolytica detection in 167 stool specimens found that microscopy detected 15 samples positive for E. histolytica/E. dispar/E. moshkovskii complex, of which only 9 (60%) were confirmed as E. histolytica by ELISA [3]. Furthermore, among 152 samples negative by microscopy, the ELISA test detected E. histolytica infection in 10 samples, demonstrating the limitations of microscopy both in specificity and sensitivity [3].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Diagnostic Methods for E. histolytica

| Diagnostic Method | Sensitivity Range | Specificity Range | Ability to Distinguish Species | Time to Result | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopy | 25-60% [11] [7] | Poor (species indistinguishable) [7] | No | Hours | Requires multiple samples, examiner expertise, immediate processing |

| Antigen Detection (ELISA) | ~90% (fecal) [11] [7] | >80% [7] | Yes | Hours to 1 day | Does not detect cysts, limited extraintestinal validation |

| PCR | >90% [11] [7] | >90% [11] [7] | Yes | 1-2 days | Cost, equipment requirements, limited extraintestinal validation |

| Serology | 70-90% (extraintestinal) [11] | Variable | Indirect evidence | Hours to 1 day | Cannot differentiate acute from past infection, limited intestinal utility |

Impact of Test Performance on Clinical Outcomes

The diagnostic performance of these methods directly influences clinical management decisions and patient outcomes. A retrospective study of travelers and migrants presenting to a national reference travel clinic in Europe found that only 3.6% of stool samples positive for E. histolytica/dispar by microscopy or antigen detection were confirmed as true E. histolytica infection by PCR [16]. This highlights the substantial overdiagnosis that occurs when relying solely on non-specific diagnostic methods.

The clinical significance of accurate diagnosis is further emphasized by case reports demonstrating severe outcomes following misdiagnosis. In one case series, multiple patients initially diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease based on clinical presentation and non-specific findings were subsequently found to have amoebic colitis, with some developing complications such as colonic perforation requiring emergency surgery [11]. The administration of corticosteroids for misdiagnosed IBD in patients with amoebic colitis can trigger dramatic clinical deterioration, highlighting the critical importance of accurate species identification before initiating immunosuppressive therapy [14].

Table 2: Clinical Consequences of Misdiagnosis Based on Diagnostic Method

| Diagnostic Scenario | False Positive Consequences | False Negative Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Microscopy misidentification | Unnecessary antimicrobial treatment (62.2% of microscopy-positive cases in one study [12]) | Progression to invasive disease, complications (perforation, abscess) [11] |

| Antigen test false result | Less unnecessary treatment than microscopy, but still possible | Missed infections (10/152 microscopy-negative cases in one study [3]) |

| PCR false result | Rare due to high specificity | Limited data, but potentially missed infections if sensitivity not 100% |

| Serology misinterpretation | Treatment for resolved infection | Delayed diagnosis of extraintestinal disease |

Experimental Protocols for Diagnostic Evaluation

Microscopy with Confirmation Protocol

Principle: Standard microscopic examination followed by specific confirmation testing to distinguish E. histolytica from non-pathogenic species.

Sample Collection: Collect fresh stool specimens (minimum 1 mL) and immediately mix with sodium acetate-acetic acid-formalin (SAF) preservative for microscopy, plus an unpreserved specimen for antigen or PCR testing. Serial collection of 2-3 specimens over several days is recommended due to intermittent parasite shedding [7].

Staining and Examination: Process SAF-preserved specimens using formalin-ethyl acetate (FEA) concentration followed by permanent staining (hematoxylin or trichrome). Examine for characteristic cysts (12-15μm with 1-4 nuclei) or trophozoites (12-50μm with single nucleus containing central karyosome). Note: Hematophagy (presence of ingested red blood cells) strongly suggests E. histolytica but is not pathognomonic [7] [16].

Confirmation Testing: Submit unpreserved specimens for antigen detection (ELISA) or PCR following manufacturer protocols. The Techlab E. HISTOLYTICA II ELISA detects Gal/GalNAc lectin specific to E. histolytica trophozoites [7]. PCR targets species-specific sequences in the small subunit ribosomal RNA gene [7].

Interpretation: Positive microscopy with negative antigen/PCR suggests non-pathogenic Entamoeba species. Negative microscopy with positive antigen/PCR indicates true infection missed by microscopy. Positive microscopy with positive antigen/PCR confirms E. histolytica infection.

Antigen Detection ELISA Protocol

Principle: Microplate enzyme immunoassay for detection of E. histolytica-specific galactose adhesin (Gal/GalNAc lectin) in fecal specimens.

Reagents: Commercial E. HISTOLYTICA II kit (Techlab, Inc.) containing: monoclonal anti-Gal/GalNAc lectin antibody coated microplate, peroxidase-conjugated detection antibody, substrate solution (TMB), stop solution, wash buffer, and positive/negative controls [3] [7].

Procedure:

- Prepare 10% stool suspension in sample diluent.

- Add 100μL of prepared sample, positive control, and negative control to separate wells.

- Incubate 60 minutes at room temperature.

- Wash plate 5 times with wash buffer.

- Add 100μL peroxidase-conjugated detector antibody to each well.

- Incubate 60 minutes at room temperature.

- Wash plate 5 times with wash buffer.

- Add 100μL substrate solution to each well.

- Incubate 10 minutes at room temperature in dark.

- Add 100μL stop solution to each well.

- Measure optical density at 450nm within 15 minutes.

Interpretation: Calculate cutoff value per manufacturer instructions (typically 0.05 OD units after subtracting negative control). Values ≥ cutoff are positive for E. histolytica antigen [3].

Limitations: Does not detect cyst antigens; may miss asymptomatic cyst passers. Limited validation on extraintestinal specimens [7].

Diagnostic Pathways and Decision Algorithms

The following diagnostic workflow illustrates the recommended pathway for accurate identification of E. histolytica infection and the consequences of misdiagnosis at critical decision points.

Diagram 1: Diagnostic Pathway for E. histolytica Identification and Clinical Consequences of Misdiagnosis. This workflow illustrates critical decision points where diagnostic limitations can lead to unnecessary treatment or missed infections.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for E. histolytica Diagnostic Development

| Reagent/Kit | Specific Target | Application | Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Techlab E. HISTOLYTICA II ELISA | Gal/GalNAc lectin (adhesin) | Antigen detection in fecal specimens | Sensitivity: ~90%, Specificity: >80% [3] [7] |

| Serazym E. histolytica Antigen Test | Serine-rich 30 kD membrane protein (SREHP) | Antigen detection in fecal specimens | Comparable to Techlab ELISA [12] |

| Bichro-Latex Amibe Fumouze Test | Anti-E. histolytica antibodies | Antibody detection in serum | Latex agglutination format [12] |

| IHA-Amebiasis Fumouze Test | Anti-E. histolytica antibodies | Quantitative antibody detection | Indirect hemagglutination format [12] |

| PCR primers for SSU rDNA | Small subunit ribosomal RNA gene | Species-specific identification | Sensitivity: >90%, Specificity: >90% [7] |

| SAF preservative | N/A | Stool specimen preservation | Maintains parasite morphology for microscopy [7] |

| Trichrome stain | Cellular components | Permanent staining of stool specimens | Differentiates parasite structures [12] |

The clinical consequences of misdiagnosis in amebiasis are substantial and operate in both diagnostic directions. Unnecessary treatment of non-pathogenic Entamoeba species exposes patients to potential medication side effects and generates avoidable healthcare costs, while missed E. histolytica infections can lead to severe complications including colonic perforation, abscess formation, and inappropriate treatment with corticosteroids when misdiagnosed as IBD.

The evidence clearly demonstrates that conventional microscopy alone is insufficient for accurate diagnosis, with specificity limitations that result in significant false positive rates. Antigen detection tests offer substantially improved specificity for E. histolytica identification, while molecular methods such as PCR provide the highest sensitivity and specificity. The development of rapid, accurate point-of-care diagnostics remains a critical need, particularly in resource-limited settings where the burden of amebiasis is highest.

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, these findings highlight the imperative to advance diagnostic capabilities through improved assay design, validation in diverse populations, and implementation of algorithmic approaches that combine multiple diagnostic methods. Future efforts should focus on developing accessible molecular diagnostics, validating tests for extraintestinal specimens, and establishing standardized protocols that can be implemented across varied healthcare settings to mitigate the clinical consequences of misdiagnosis.

Microscopy has long been the cornerstone of parasitic diagnosis in clinical laboratories worldwide, particularly for detecting Entamoeba histolytica in stool specimens. However, its utility is severely compromised by significant sensitivity and specificity limitations. This comprehensive analysis compares microscopy's performance against modern diagnostic alternatives, particularly antigen detection tests and molecular methods. Quantitative data synthesis reveals microscopy possesses alarmingly low sensitivity (10-61.5%) and problematic specificity due to its inability to differentiate pathogenic E. histolytica from non-pathogenic but morphologically identical species. These deficiencies have profound implications for patient management, public health surveillance, and drug development efforts requiring accurate pathogen identification.

The World Health Organization specifically recommends that E. histolytica "should be specifically identified and if present should be treated" [17]. This directive presents a fundamental challenge for microscopy-based diagnosis, which cannot reliably distinguish pathogenic E. histolytica from non-pathogenic but identically appearing species like Entamoeba dispar and Entamoeba moshkovskii [17] [7]. While microscopy remains widely used due to its low cost and technical accessibility, growing evidence confirms substantial diagnostic limitations that impact clinical decision-making and therapeutic outcomes. This analysis examines the specific sensitivity and specificity gaps of microscopy through direct comparison with antigen detection and PCR-based methods, providing researchers and drug development professionals with evidence-based diagnostic performance data.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Diagnostic Modalities

Sensitivity and Specificity Profiles

Table 1 summarizes the performance characteristics of major diagnostic methods for E. histolytica detection based on aggregated study data.

Table 1: Performance comparison of diagnostic methods for E. histolytica

| Diagnostic Method | Sensitivity Range | Specificity Range | Distinguishes E. histolytica from non-pathogenic species | Optimal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopy | 10-61.5% [17] [18] | Low (exact values not consistently reported) | No [17] [7] [18] | Initial screening in resource-limited settings |

| Antigen Detection (ELISA) | 71-90% [17] [7] [19] | 80-100% [17] [7] [19] | Yes (when using E. histolytica-specific tests) [17] [7] | Routine confirmation of microscopy-positive samples |

| Traditional PCR | 72% [17] | 99% [17] | Yes [17] [20] | Species confirmation in reference laboratories |

| Real-time PCR | 75-100% [17] [21] [9] | 94-100% [17] [21] [9] | Yes [17] [20] [21] | Gold standard for clinical trials and research studies |

Detailed Performance Gap Analysis

Sensitivity Deficiencies of Microscopy

Microscopy demonstrates remarkably variable and often inadequate sensitivity for E. histolytica detection. One study reported sensitivity as low as 10-60% for microscopy compared to reference standards [17]. A more recent investigation found microscopy sensitivity of just 61.54% for E. histolytica/E. dispar detection combined [18], while another study reported only 34.7% sensitivity for wet mount examination for one or more intestinal parasites [18]. This poor sensitivity stems from multiple factors: intermittent parasite shedding, low cyst counts in specimens, inadequate sample collection, and requirement for immediate examination of fresh samples [18]. Even with concentration techniques like formalin-ether sedimentation, sensitivity remains suboptimal compared to immunologic and molecular methods [18].

Specificity Limitations of Microscopy

The critical flaw of microscopy lies in its inability to differentiate E. histolytica from non-pathogenic species including E. dispar, E. moshkovskii, and E. bangladeshi, which are morphologically identical [17] [7] [18]. This distinction has profound clinical implications since only E. histolytica requires treatment, while others are considered harmless commensals [19]. Public Health Ontario explicitly states that microscopy "cannot distinguish Entamoeba histolytica from other morphologically identical but non-pathogenic Entamoeba species" [7]. Consequently, microscopy results must be reported as "E. histolytica/E. dispar/E. moshkovskii/E. bangladeshi" without differentiation [7], severely limiting clinical utility.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Microscopy Protocol

Specimen Collection and Handling: Fresh stool specimens should be collected without contamination with urine or water. Unpreserved specimens must be processed within 1-2 hours of collection for trophozoite detection, or placed in preservatives like SAF (sodium acetate-acetic acid-formalin) for cyst identification [7] [18].

Direct Wet Mount Preparation:

- Emulsify a small portion of stool specimen (approximately 2 mg) in a drop of 0.9% saline on a microscope slide for trophozoite detection.

- Prepare a separate emulsion in Lugol's iodine (2-5%) for cyst identification.

- Apply coverslips and examine systematically at 100× and 400× magnification.

Concentration Techniques:

- Formalin-ether sedimentation: Mix 1-2 g of stool with 10 mL of 10% formalin. Filter through gauze, add 3 mL of ether, centrifuge at 500 × g for 2 minutes. Examine sediment [18].

- Avoid flotation techniques as they may collapse Entamoeba cysts [18].

Staining Methods:

- Permanent stains like iron-hematoxylin or trichrome enable better visualization of internal structures.

- Examine for characteristic spherical cysts (10-15 μm diameter) with 1-4 nuclei, or trophozoites (20-30 μm) with single nuclei and often ingested erythrocytes in invasive infections [20] [18].

Quality Considerations: Examination of two or more stool samples collected over several days is recommended to improve detection sensitivity [18]. Even with optimal technique, species differentiation remains impossible.

Antigen Detection Protocol (TechLab E. histolytica II Test)

Principle: This FDA-approved ELISA captures and detects the E. histolytica-specific Gal/GalNAc lectin from stool samples, enabling specific identification of the pathogenic species [17] [7].

Procedure:

- Add 100 μL of diluted stool specimen to antibody-coated microtiter wells.

- Incubate for 1 hour at 37°C, then wash.

- Add 100 μL of horseradish peroxidase-conjugate, incubate for 1 hour at 37°C, then wash.

- Add 100 μL of TMB substrate, incubate for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- Stop reaction with 100 μL stop solution.

- Read absorbance at 450 nm within 30 minutes [17] [20].

Interpretation: Sample with optical density ≥0.15 is considered positive for E. histolytica [17]. The test specifically detects trophozoite antigens and may miss asymptomatic cyst carriers [7].

PCR-Based Detection Protocol

DNA Extraction:

- Use 0.2 g of stool or liver abscess pus specimen.

- Wash twice with sterile phosphate-buffered saline, centrifuge at 14,000 rpm for 5 minutes.

- Extract DNA using QIAamp DNA stool mini kit (QIAGEN) with modified protocol: incubate in stool lysis buffer at 95°C, use 3-minute incubation with InhibitEx tablets.

- Elute DNA in 0.2 mL AE buffer [17].

Real-time PCR Assay:

- Reaction Mix: 25 μL total volume containing Bio-Rad's IQ super mix, 25 pmol each of forward (5'-AAC AGT AAT AGT TTC TTT GGT TAG TAA AA-3') and reverse (5'-CTT AGA ATG TCA TTT CTC AAT TCA T-3') primers, 6.25 pmol of molecular-beacon probe, and 2.0 μL DNA sample [17].

- Amplification Parameters: 45 cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C, 30 seconds at 55°C, and 15 seconds at 72°C [17].

- Detection: Fluorescence measurement at 575 nm during annealing steps [17].

Performance Notes: Real-time PCR demonstrates superior sensitivity (75-100%) and specificity (94-100%) compared to other methods, making it ideal for research and reference applications [17] [21] [9].

Diagnostic Pathway and Method Selection

Diagram: Diagnostic workflow illustrating microscopy's role as initial screen requiring confirmation by more specific methods.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2 outlines essential research reagents and their applications in E. histolytica diagnostics.

Table 2: Key research reagents for E. histolytica detection

| Reagent/Kit | Manufacturer | Application | Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit | QIAGEN | DNA extraction from stool and abscess specimens | Efficient nucleic acid purification; critical for PCR reliability [17] |

| TechLab E. histolytica II | TechLab | E. histolytica-specific antigen detection | Detects Gal/GalNAc lectin; 71% sensitivity, 100% specificity vs. PCR [17] [19] |

| Entamoeba Real-time PCR Primers/Probes | Custom synthesis | Species-specific DNA amplification | Targets small-subunit rRNA gene; 75-100% sensitivity, 94-100% specificity [17] [21] |

| SAF Preservative | Various | Stool specimen preservation | Maintains parasite morphology for microscopy while allowing molecular testing [7] |

| Formalin-Ether Concentration Reagents | Laboratory-prepared | Parasite cyst concentration | Enhances microscopy sensitivity; essential for epidemiological studies [18] |

Implications for Research and Drug Development

The diagnostic limitations of microscopy extend beyond clinical misdiagnosis to impact research and therapeutic development. Inaccurate diagnosis leads to inappropriate patient inclusion in clinical trials, confounding therapeutic efficacy assessments. A study in central Iran demonstrated that among 53 dysentery cases reported as E. histolytica-positive by microscopy, only 22.6% were truly positive, with 77.4% misdiagnosed [18]. Such inaccuracies profoundly distort epidemiological data, drug efficacy evaluations, and vaccine development efforts.

Molecular methods now enable precise parasite identification, with real-time PCR emerging as the reference standard despite higher complexity and cost [17] [21] [9]. The superior specificity of PCR-based diagnosis ensures that drug development targets truly pathogenic E. histolytica infections rather than benign colonization by non-pathogenic species. Furthermore, molecular methods facilitate strain typing and tracking, valuable for understanding transmission patterns and detecting outbreaks [21].

Microscopy remains entrenched in parasitic diagnosis, particularly in resource-limited settings where amebiasis is endemic. However, evidence unequivocally demonstrates critical sensitivity and specificity limitations that impede accurate E. histolytica identification. The method's inability to differentiate pathogenic from non-pathogenic species represents its most significant deficiency, leading to both overtreatment of benign infections and missed opportunities to treat truly invasive disease. Antigen detection tests offer a practical compromise with good specificity and moderate sensitivity, while PCR-based methods provide the highest accuracy for research and reference applications. For drug development professionals and researchers, embracing molecular confirmation is essential for ensuring accurate patient stratification, reliable efficacy assessment, and meaningful epidemiological surveillance.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has long emphasized that accurate, species-specific diagnosis is a critical component in the global fight against infectious diseases. For amoebiasis, caused by the protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica, this mandate is particularly pressing. This parasite is responsible for approximately 100,000 deaths annually worldwide, making it the third leading cause of parasitic mortality [22] [18]. The central diagnostic challenge, which the WHO has sought to resolve, stems from the fact that E. histolytica is morphologically identical to non-pathogenic species such as E. dispar and E. moshkovskii under a microscope [12] [23]. Consequently, reliance on traditional microscopy alone has led to significant over-reporting of true amebiasis cases, unnecessary treatments, and a distorted understanding of the disease's epidemiology [12] [23]. This article explores the WHO's push for species-specific diagnosis, framing it within a broader thesis on the superior specificity of antigen tests and molecular methods for E. histolytica compared to conventional microscopy.

The Diagnostic Evolution: From Morphology to Molecular Specificity

The Limitations of Conventional Microscopy

For decades, microscopy was the cornerstone of Entamoeba detection. While it is an economical and rapid method, its limitations are profound and well-documented. Microscopy cannot differentiate the pathogenic E. histolytica from non-pathogenic look-alikes, a critical distinction for clinical management [7] [12]. Furthermore, its sensitivity is highly variable and often low. A recent study demonstrated a sensitivity of just 61.54% for detecting E. histolytica/E. dispar [18], while another highlighted that microscopy's sensitivity for intestinal infection is generally below 60% [7]. The accuracy of microscopy is also heavily dependent on the skill of the microscopist and the quality of the specimen, leading to frequent misdiagnosis. One study in central Iran found that of 53 dysentery cases reported as positive for E. histolytica by laboratory staff, only 12 (22.6%) were truly positive, with the rest being misdiagnosed [18]. This high rate of error underscores the WHO's concern about non-specific diagnostic methods.

The WHO's Clarion Call for Specificity

The WHO expert consultation on amoebiasis formally recognized these diagnostic challenges and stressed the urgent need to develop and implement simple methods for the specific diagnosis of E. histolytica [18]. The consultation recommended that when microscopy is used, findings should be reported as "E. histolytica/E. dispar" to acknowledge this diagnostic uncertainty [18]. This recommendation was a pivotal step, moving the global community away from accepting morphological diagnosis as definitive and toward the adoption of more reliable, species-specific tools. The goal is to ensure that only patients with the pathogenic E. histolytica infection receive treatment, thereby avoiding unnecessary drug exposure, reducing healthcare costs, and enabling accurate surveillance and containment efforts [12].

Comparative Analysis of Diagnostic Technologies

The following table summarizes the key performance metrics of the primary diagnostic methods for Entamoeba histolytica, highlighting the evolution toward greater specificity.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Diagnostic Methods for E. histolytica

| Diagnostic Method | Specificity | Sensitivity | Ability to Distinguish E. histolytica | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Microscopy | Low (unquantified) | 34.7% - 61.54% [18] | No (reports E. histolytica/dispar/moshkovskii group) [7] | Operator-dependent; unable to differentiate species [18]. |

| Techlab II Antigen Test | >96% [24] | 79% - 88% [24] [7] | Yes (detects specific Gal/GalNAc lectin) [7] | Does not detect the cyst form [7]. |

| PCR | 89% - 100% [22] [9] | 92% - 100% [22] [9] | Yes (targets species-specific DNA) | Expensive; requires skilled technicians and specialized equipment [24]. |

Antigen Detection Tests: A Practical Solution

Antigen detection tests, particularly enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs), represent a significant advancement by balancing specificity, practicality, and cost. These tests detect species-specific proteins secreted by E. histolytica trophozoites, such as the galactose/N-acetylgalactosamine-binding lectin (Gal/GalNAc lectin) [7].

A direct comparative study of two commercial ELISA kits—the Techlab E. histolytica II test and the R-Biopharm Ridascreen Entamoeba test—demonstrated the critical importance of target selection. The study found the Techlab test was both more sensitive and specific. Crucially, it detected as few as 24 E. histolytica trophozoites per well and showed no cross-reaction with E. dispar. In contrast, the Ridascreen test required around 25,000 E. dispar trophozoites per well for a positive reaction, indicating a lack of species specificity [24]. When testing 110 clinical fecal specimens, the Techlab test identified 50 E. histolytica-positive samples, while the Ridascreen test identified only 34. PCR analysis confirmed that the 22 samples missed by the Ridascreen test were true positives, underscoring the superior sensitivity of the species-specific Techlab assay [24].

Molecular Methods: The Gold Standard

Molecular methods, specifically PCR, are now considered the gold standard for species-specific diagnosis. PCR targets and amplifies unique genetic sequences of E. histolytica, such as those in the small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) gene, providing exceptional sensitivity and specificity [7] [9]. A 2025 study comparing three different real-time PCR assays for E. histolytica reported diagnostic accuracy estimates with sensitivity ranging from 75% to 100% and specificity from 94% to 100% [9]. While PCR is the most accurate method, its adoption in resource-limited settings—where amoebiasis is endemic—is hindered by requirements for sophisticated equipment, skilled technicians, and higher costs [24] [18]. Nevertheless, it serves as the definitive reference for validating other diagnostic methods.

Experimental Protocols for Diagnostic Validation

To illustrate the evidence base supporting this diagnostic shift, below are detailed methodologies from key comparative studies.

Protocol 1: Comparative ELISA Evaluation

This protocol is derived from a study that directly compared the performance of two commercial antigen detection tests [24].

- Objective: To compare the sensitivity and specificity of the Techlab E. histolytica II test and the R-Biopharm Ridascreen Entamoeba test.

- Sample Preparation: Cultured E. histolytica (strains HM1:1MSS and Ax 259100) and E. dispar (strain SAW760) trophozoites were harvested. Twofold dilution series were prepared, ranging from 5.0 × 10^5 to 15 trophozoites per milliliter, in the respective kit diluents.

- Testing Procedure: Each dilution was tested in duplicate according to the manufacturers' instructions. For clinical validation, 110 fecal specimens from patients in Bangladesh, previously screened by microscopy, were tested with both ELISA kits.

- Reference Standard: Discrepant results between the two ELISAs were resolved using a PCR method specific for E. histolytica and E. dispar [24].

Protocol 2: Multi-PCR Assay Comparison Using Latent Class Analysis

This protocol describes a modern approach to evaluating diagnostic tests in the absence of a perfect reference standard [9].

- Objective: To evaluate and compare the diagnostic accuracy of three published real-time PCR assays for E. histolytica.

- Sample Collection: 873 stool samples were collected from a cohort in Ghana.

- Testing Procedure: Each sample was tested using three different real-time PCR assays. The assays targeted different genetic sequences, including the small-subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) gene and the serine-rich E. histolytica protein (SREHP) gene.

- Statistical Analysis: Since no single reference standard was definitive, researchers employed latent class analysis (LCA). This statistical model calculates the diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity and specificity) of all tests simultaneously and estimates the true prevalence of infection without relying on a pre-defined "gold standard" [9].

The experimental workflow for this sophisticated multi-assay comparison is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

For researchers aiming to develop or validate species-specific diagnostics for E. histolytica, a core set of reagents and tools is essential. The following table catalogues these key resources.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for E. histolytica Diagnostic Development

| Research Reagent | Function / Target | Application in Diagnostics |

|---|---|---|

| Techlab E. histolytica II [24] [7] | Monoclonal antibody detecting Gal/GalNAc lectin antigen. | Gold-standard ELISA for antigen detection; used as a comparator in validation studies. |

| SSU rRNA Gene Primers [7] [9] | Oligonucleotides for amplifying species-specific regions of the small subunit ribosomal RNA gene. | Target for laboratory-developed and commercial PCR assays; provides high specificity. |

| Cultured Trophozoites [24] | Axenically or xenically cultivated E. histolytica strains (e.g., HM1:1MSS). | Provide positive control material for assay development, sensitivity testing, and dilution curves. |

| Formalin-Ethyl Acetate (FEA) [7] | Reagents for diphasic sedimentation concentration of stool specimens. | Parasitology method for concentrating cysts in stool prior to microscopic or molecular analysis. |

| Latent Class Analysis (LCA) [9] | A statistical modeling technique. | Evaluates and compares the accuracy of multiple diagnostic tests when a perfect reference standard is unavailable. |

The WHO's mandate for species-specific diagnosis of E. histolytica has fundamentally reshaped the diagnostic landscape for amoebiasis. The move away from non-specific microscopy toward antigen and molecular detection methods is a clear response to the need for diagnostic precision. As the experimental data shows, modern antigen tests like the Techlab II ELISA offer a highly specific and practical solution for many clinical and public health settings, while PCR remains the undisputed gold standard for accuracy. The continued development and deployment of these tools, especially in endemic regions, are paramount for achieving the ultimate goals: ensuring patients receive correct and timely treatment, conserving valuable healthcare resources, and generating accurate epidemiological data to guide the global public health response to this persistent parasitic disease.

Mechanisms and Workflows: Principles of E. histolytica-Specific Antigen Detection

Entamoeba histolytica, the causative agent of amebiasis, is a protozoan parasite responsible for an estimated 50 million cases of colitis and liver abscess annually, resulting in 40,000 to 110,000 deaths worldwide each year [25]. A significant diagnostic challenge stems from the fact that E. histolytica is morphologically indistinguishable from the non-pathogenic commensal ameba, Entamoeba dispar, under direct microscopic examination [12] [26]. This limitation has profound implications for both treatment and healthcare costs, as it can lead to unnecessary medication for patients with E. dispar and delayed treatment for those with true E. histolytica infection [12].

Within this diagnostic landscape, the Gal/GalNAc lectin has emerged as a critical virulence factor and species-specific antigen. This multifunctional protein, located on the surface of E. histolytica trophozoites, plays essential roles in adherence, cytolysis, invasion, and resistance to complement-mediated lysis [27]. This review objectively compares the performance of diagnostic tests targeting the Gal/GalNAc lectin against traditional microscopy and other alternatives, providing experimental data and methodologies to guide researchers and drug development professionals in advancing the field of amebiasis diagnostics.

Structural and Functional Biology of the Gal/GalNAc Lectin

The Gal/GalNAc lectin is a complex transmembrane protein. The native structure is a 260-kDa heterodimer consisting of a type I membrane protein disulfide-bonded to a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored protein [27]. Research has also identified a 150-kDa intermediate subunit (Igl) that associates non-covalently with the heavy subunit [27] [25]. The Igl subunit is a cysteine-rich protein comprising 1,101 amino acids and containing multiple CXXC motifs, which are believed to be important for its function and stability [25].

Functionally, this lectin is indispensable for pathogenesis. Specific monoclonal antibodies against the lectin can significantly inhibit trophozoite adherence and cytotoxicity to mammalian cells, erythrophagocytosis, and liver abscess formation in animal models [25]. The lectin mediates the binding of trophozoites to host cells via galactose and N-acetyl-D-galactosamine residues on host surface glycoproteins, initiating the cytotoxic events that lead to tissue invasion [27].

Diagram: Gal/GalNAc Lectin Structure and Role in Pathogenesis

The following diagram illustrates the structure of the Gal/GalNAc lectin and its central role in the pathogenesis of invasive amebiasis.

Comparative Performance of Diagnostic Methods

Comprehensive Diagnostic Method Comparison

The diagnosis of E. histolytica infection employs various methodologies, each with distinct principles, performance characteristics, and limitations. The table below provides a structured comparison of these diagnostic approaches based on published experimental data.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Diagnostic Methods for E. histolytica

| Method Category | Specific Method | Target / Principle | Reported Sensitivity | Reported Specificity | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopy | Wet mount / Trichrome staining [12] | Morphology of cysts/trophozoites | 53.85%* | 100%* | Low cost, rapid results, widely available | Cannot distinguish E. histolytica from E. dispar; low sensitivity |

| Antigen Detection (Stool) | ELISA (e.g., Wampole E. histolytica II) [12] | Gal/GalNAc lectin adhesin | 62.2% (Consensus Positivity) [12] | 100% (vs. microscopy) [26] | Species-specific, objective result | Sensitivity can be variable; requires specific antibodies |

| Antigen Detection (Stool) | Immunochromatographic RDT [26] | Gal/GalNAc lectin or other antigens | ~100% (Retrospective) [26] | 80-88% (for E. histolytica) [26] | Rapid, easy to use, no specialized equipment | Lower specificity compared to some ELISA methods |

| Antigen Detection (Abscess) | Gal/GalNAc lectin antigen test [28] | Gal/GalNAc lectin in abscess fluid | Confirming (Case Study) [28] | Confirming (Case Study) [28] | High specificity for confirming ALA | Requires invasive procedure (aspiration) |

| Serology | IHA / Latex Agglutination [12] [28] | Anti-lectin / anti-amebic antibodies | 73.3% - 75.6% (vs. antigen reference) [12] | 78.57% - 75.00% (vs. antigen reference) [12] | Useful for invasive disease (ALA) | Cannot distinguish current vs. past infection; lower utility in endemic areas |

| Molecular | Real-time PCR [21] | SSU rRNA gene / SREPH episomal repeat | 75% - 100% (LCA estimate) [21] | 94% - 100% (LCA estimate) [21] | High sensitivity and specificity; can differentiate species | Requires specialized equipment and technical expertise; cost |

Sensitivity and specificity calculated against a reference standard of positive Wampole and Serazym antigen tests [12]. *Diagnostic accuracy estimates derived from Latent Class Analysis (LCA) without a reference standard; range reflects performance of three different published assays [21].

Experimental Data on Recombinant Lectin Subunits

The potential of different regions of the Gal/GalNAc lectin as diagnostic antigens has been systematically evaluated. One pivotal study expressed the recombinant 150-kDa intermediate subunit (Igl) and three of its fragments in E. coli to assess their reactivity with patient sera [25].

Table 2: Diagnostic Performance of Recombinant Igl Fragments in ELISA

| Recombinant Antigen | Amino Acid Region | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full-length Igl | aa 14 - 1088 | 90 | 94 | High overall performance |

| N-terminal fragment | aa 14 - 382 | 56 | 96 | Moderate sensitivity |

| Middle fragment | aa 294 - 753 | 92 | 99 | High sensitivity and specificity |

| C-terminal fragment | aa 603 - 1088 | 97 | 99 | Highest performance for serodiagnosis |

The study concluded that the carboxyl terminus of Igl is an especially useful antigen for the serodiagnosis of amebiasis, recognized by sera from both symptomatic patients and asymptomatic cyst passers [25].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Recombinant Igl Protein Production and ELISA

This protocol is adapted from the methodology used to generate the performance data in Table 2 [25].

1. Plasmid Construction:

- Amplify DNA fragments encoding the desired Igl regions (e.g., full-length: aa 14-1088; C-terminal: aa 603-1088) from E. histolytica HM-1:IMSS strain genomic DNA using specific primers with added XhoI restriction sites.

- Digest the PCR products and ligate them into the pET19b expression vector.

- Transform the ligated plasmids into competent E. coli JM109 cells and select clones with the correct insert orientation.

2. Expression and Purification:

- Transform the expression host E. coli BL21 Star(DE3)pLysS with the cloned plasmids.

- Culture bacteria in LB medium with ampicillin until OD600 reaches 0.6.

- Induce protein expression with 1 mM Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 3 hours at 37°C.

- Pellet the bacteria by centrifugation and suspend in wash buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100).

- Sonicate the suspension and centrifuge. Repeat the washing step five times to obtain inclusion bodies.

- Solubilize the inclusion body pellet in solubilization buffer (500 mM CAPS pH 11, 0.3% N-lauroylsarcosine).

- Dialyze the supernatant sequentially in: a) dialysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.5, 0.1 mM DTT) overnight at 4°C, b) the same buffer without DTT for 9 hours, and c) redox refolding buffer (0.2 mM oxidized glutathione, 1 mM reduced glutathione) overnight at 4°C followed by 3 hours at room temperature.

3. ELISA Procedure:

- Coat ELISA plates with the purified, refolded recombinant proteins.

- Block plates with a suitable blocking agent (e.g., 3% skim milk or BSA).

- Incubate wells with patient serum samples diluted 1:100 in blocking buffer.

- Detect bound human IgG using horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-human IgG antibody.

- Develop with an appropriate HRP substrate and read the optical density.

Protocol: Gal/GalNAc Lectin Antigen Detection in Abscess Fluid

This protocol is based on the clinical case confirmation of an amebic liver abscess (ALA) [28].

1. Sample Collection:

- Perform ultrasound-guided percutaneous catheter drainage (PCD) of the suspected liver abscess.

- Collect the aspirated fluid, which typically has a characteristic "anchovy paste" appearance.

2. Antigen Detection:

- Use a commercial Gal/GalNAc lectin antigen detection test (e.g., an immunoassay).

- The test typically employs monoclonal antibodies specific for the lectin adhesin.

- Follow the manufacturer's instructions for processing the abscess fluid and running the assay.

- A positive antigen test confirms the presence of E. histolytica trophozoites in the abscess.

3. Complementary Serology:

- Collect a simultaneous blood sample from the patient.

- Test the serum for the presence of total anti-Gal/GalNAc antibodies using a validated serological method (e.g., IHA, ELISA).

- The combination of a positive abscess antigen test and positive serology provides a definitive diagnosis of ALA.

Diagram: Diagnostic Workflow for Suspected Amebiasis

The following diagram outlines a logical diagnostic pathway for a patient with suspected E. histolytica infection, integrating the methods discussed.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

For researchers investigating the Gal/GalNAc lectin or developing new diagnostics, the following reagents and tools are essential.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Gal/GalNAc Lectin Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Description & Function | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-Lectin Monoclonal Antibodies | Antibodies specific to Hgl, Lgl, or Igl subunits; used for functional studies and diagnostic assay development. | Used to inhibit adherence, cytolysis, and abscess formation in animal models [25]. |

| Recombinant Lectin Subunits | Purified Igl, Hgl, or their fragments (e.g., C-terminal Igl); used as standardized antigens in immunoassays. | E. coli expressed C-terminal Igl fragment (aa 603-1088) shows 97% sensitivity and 99% specificity in ELISA [25]. |

| Gal/GalNAc Carbohydrates | The specific sugars (Galactose and N-acetyl-D-galactosamine) that bind the lectin; used for inhibition studies. | Used to confirm lectin-specific binding in adherence assays [27]. |

| pET Vector Systems | Prokaryotic expression vectors (e.g., pET19b) for high-level production of recombinant lectin proteins in E. coli. | Facilitates the production of antigen for research and diagnostic use [25]. |

| Clinical Serum Panels | Well-characterized human serum samples from symptomatic amebiasis, asymptomatic cyst passers, and controls. | Essential for validating the sensitivity and specificity of new diagnostic assays [25] [12]. |

The Gal/GalNAc lectin stands as a cornerstone for achieving high specificity in the diagnosis of E. histolytica infection. While microscopy remains a common initial tool due to its accessibility, it fails to differentiate pathogenic E. histolytica from non-pathogenic amebae, a critical limitation for clinical decision-making [12]. Diagnostic methods targeting the Gal/GalNAc lectin—whether through direct antigen detection in stool or abscess fluid, or indirectly via serological detection of anti-lectin antibodies—provide the species-specificity that microscopy lacks [25] [28].

Among the most promising targets is the C-terminal fragment of the Igl subunit, which demonstrates superior diagnostic performance in serological assays [25]. Molecular methods like PCR offer excellent sensitivity and specificity but require specialized resources [21]. The choice of diagnostic method must therefore balance performance, resource availability, and the clinical context (intestinal vs. extra-intestinal disease). For researchers and drug developers, continued refinement of lectin-based assays and exploration of recombinant antigens hold the key to further improving the accuracy, accessibility, and cost-effectiveness of amebiasis diagnosis worldwide.

Accurate diagnosis of entamoeba histolytica infection represents a significant challenge in clinical parasitology. The fundamental issue stems from the fact that E. histolytica is microscopically indistinguishable from other non-pathogenic Entamoeba species, particularly E. dispar and E. moshkovskii [3]. This diagnostic dilemma has profound clinical implications, as E. histolytica can cause invasive amebiasis including colitis and liver abscesses resulting in an estimated 40,000-100,000 deaths annually worldwide, while E. dispar and E. moshkovskii are considered non-pathogenic and do not require treatment [3]. Traditional microscopy, while widely available, demonstrates poor specificity in distinguishing these species, potentially leading to both unnecessary treatment for patients with non-pathogenic species and missed treatment for those with true E. histolytica infections [3]. Within this diagnostic landscape, antigen detection tests specifically the TechLab E. HISTOLYTICA II ELISA have emerged as critical tools for providing species-specific diagnosis. This platform deep-dive examines the protocol, performance characteristics, and comparative value of this ELISA technology within the broader context of E. histolytica diagnostic solutions.

The E. HISTOLYTICA II ELISA: Core Technology and Mechanism

The TechLab E. HISTOLYTICA II test is a second-generation monoclonal antibody-based ELISA designed for the rapid detection of Entamoeba histolytica-specific galactose/N-acetylgalactosamine-inhibitable lectin (Gal/GalNAc lectin), also known as adhesin, in fecal specimens [29] [30] [7]. This lectin is a surface protein expressed by E. histolytica trophozoites that mediates adherence to the intestinal mucosa, a critical step in the pathogenesis of invasive disease [30].

The test employs monoclonal antibodies that specifically target the E. histolytica adhesin molecule, which is shed into the feces during active infection [30] [31]. A key technological advantage of this assay is its exclusive specificity for E. histolytica; it does not cross-react with adhesin molecules from non-pathogenic Entamoeba species, enabling definitive differentiation between pathogenic and non-pathogenic infections [29] [30]. The assay detects this specific antigen in fecal specimens and provides results in less than 2.5 hours with a highly standardized protocol [29].

Figure 1: Detection Principle of the E. HISTOLYTICA II ELISA. The pathway illustrates the specific detection of E. histolytica Gal/GalNAc lectin antigen from infection to diagnostic result.

Experimental Protocol and Workflow

The E. HISTOLYTICA II ELISA follows a standardized protocol designed for reliable performance in clinical laboratory settings. The complete workflow from sample collection to result interpretation is detailed below.

Figure 2: E. HISTOLYTICA II ELISA Workflow. The diagram outlines the key procedural steps from sample preparation to final result interpretation.

Sample Requirements and Preparation

- Sample Type: Unpreserved fresh or frozen fecal specimens [30] [7]

- Preservation Limitations: The test cannot be used with samples preserved in sodium acetate, acetic acid, and formalin (SAF) or other preservatives [7]

- Sample Processing: Stool samples should be processed without delay upon arrival at the laboratory

- Storage Conditions: Fresh samples should be stored at 2-8°C and tested within 48 hours of collection; if longer storage is required, samples should be frozen at -20°C or lower [7]

Step-by-Step Assay Procedure

- Specimen Preparation: Emulsify fecal specimen in sample dilution buffer according to manufacturer's specifications [29]

- Plate Configuration: Dispense diluted samples, controls, and calibrators into designated wells of the microplate pre-coated with anti-adhesin monoclonal antibodies [29]

- Incubation: Incubate at room temperature for approximately 90 minutes to allow antigen capture [29]

- Washing: Perform wash steps to remove unbound material [29]

- Detection Incubation: Add enzyme-conjugated detector antibody and incubate [29]

- Substrate Addition: Add enzyme substrate solution and incubate for color development [29]

- Reaction Stopping: Add stop solution to terminate the enzymatic reaction [29]

- Photometric Reading: Measure optical density (OD) at specified wavelength within defined time frame [29] [3]

Result Interpretation

- Positive Result: Optical density reading of ≥ 0.05 after subtraction of the negative control optical density [3]

- Negative Result: Optical density below the established cutoff [7]

- Invalid Result: Invalid controls require test repetition [7]

Performance Characteristics and Validation Data

Analytical Sensitivity and Specificity

The E. HISTOLYTICA II ELISA demonstrates excellent performance characteristics in clinical validation studies. According to manufacturer data, the sensitivity ranges from 96.9% to 100%, while specificity ranges from 94.7% to 100% [3]. Independent studies have confirmed these findings, with one evaluation reporting sensitivity under 90% and specificity above 80% [7].

Comparative Diagnostic Performance

Table 1: Comparative Performance of E. histolytica Diagnostic Methods

| Method | Sensitivity | Specificity | Time to Result | E. histolytica Specific | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopy | 47.3% [3] | 95.9% [3] | <1 hour | No (cannot distinguish E. histolytica from E. dispar/E. moshkovskii) [3] | Requires expertise, limited sensitivity, poor species differentiation [3] [7] |

| E. HISTOLYTICA II ELISA | 96.9-100% [3] | 94.7-100% [3] | <2.5 hours [29] | Yes [29] | Does not detect cysts [30] |

| PCR | >90% [7] | >90% [7] | Several hours to days | Yes [7] | Higher cost, technical expertise required, not universally available [7] |

| Rapid Diagnostic Tests | 100% (for E. histolytica) [26] | 80-88% [26] | <30 minutes | Variable by brand [26] | Lower specificity compared to ELISA [26] |

Clinical Impact and Diagnostic Outcomes

The clinical superiority of antigen detection over microscopy is demonstrated in a study of 167 stool specimens where microscopy detected 15 samples positive for E. histolytica/E. dispar/E. moshkovskii complex, but the E. HISTOLYTICA II ELISA confirmed only 9 (60%) as true E. histolytica infections [3]. Crucially, the ELISA identified an additional 10 E. histolytica-positive samples among the 152 specimens that microscopy had reported as negative [3]. This translates to significant clinical implications:

- Overtreatment Avoidance: 6 out of 15 microscopy-positive patients would avoid unnecessary treatment [3]

- Missed Treatment Prevention: 10 out of 152 microscopy-negative patients would receive necessary treatment [3]

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Diagnostic Platforms

ELISA vs. Microscopy