Automated Nucleic Acid Extraction from Stool Samples: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Developers

Automated nucleic acid extraction from stool samples is a critical yet challenging step in molecular diagnostics and microbiome research.

Automated Nucleic Acid Extraction from Stool Samples: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Developers

Abstract

Automated nucleic acid extraction from stool samples is a critical yet challenging step in molecular diagnostics and microbiome research. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of stool as a complex sample matrix, current automated methodologies including magnetic bead-based systems and novel nanoparticle technologies, strategies for troubleshooting common inhibitors and optimizing protocols, and frameworks for analytical and clinical validation. By synthesizing the latest technological advancements and practical implementation insights, this guide aims to support the development of robust, high-yield extraction workflows for applications ranging from infectious disease diagnostics to microbiome profiling and colorectal cancer screening.

Why Stool is Challenging: Understanding the Complex Matrix for Nucleic Acid Extraction

The automated extraction of nucleic acids from stool samples is a cornerstone of modern molecular diagnostics and microbiome research. However, the complex and inhibitor-rich nature of stool presents significant challenges for consistent and reliable results. A comprehensive understanding of the key interfering substances and the development of robust protocols to neutralize them are critical for the success of downstream applications, such as PCR, sequencing, and the detection of pathogens or host biomarkers. This Application Note details the primary inhibitors found in human stool, provides validated protocols for their mitigation, and presents quantitative data to guide researchers in optimizing automated nucleic acid extraction workflows. The information is framed within the context of advancing research for large-scale screening studies and diagnostic test development [1] [2].

Key Inhibitors and Interfering Substances in Stool

The efficacy of nucleic acid extraction and subsequent molecular analyses is frequently compromised by a variety of substances endogenous to stool. These compounds can co-purify with nucleic acids and inhibit enzymatic reactions. The table below summarizes the major categories of inhibitors, their impact on downstream processes, and their common sources.

Table 1: Key Inhibitors and Interfering Substances in Stool Samples

| Inhibitor Category | Specific Examples | Primary Impact on Downstream Assays | Origin in Stool |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complex Polysaccharides | Hemicelluloses, Pectins | Bind to nucleic acids and enzymes; increase viscosity [3]. | Plant-derived dietary fiber. |

| Bile Salts | Bilirubin, various bile acids | Disrupt enzyme function by denaturing proteins [3]. | Digestive secretions from the liver. |

| Bacterial Metabolites | Short-chain fatty acids, organic acids | Alter pH and disrupt enzymatic activity [3]. | Fermentation by gut microbiota. |

| Pigments | Heme, Bilin | Interfere with spectrophotometric quantification and PCR [3]. | Breakdown of blood cells and chlorophyll. |

| Proteases | Various host and microbial enzymes | Degrade polymerase and other enzymes used in molecular assays [3]. | Pancreatic secretions and gut bacteria. |

| Ionic Substances | Calcium, inorganic salts | Can affect enzymatic efficiency and nucleic acid stability [3]. | Diet, secretions, and microbial activity. |

Quantitative Impact of Inhibitors on DNA Yield and Quality

The presence of inhibitors not only affects amplification but also the initial recovery of nucleic acids. Variability in stool composition leads to significant differences in DNA yield and quality. The following table compiles data from studies that have quantified these parameters, highlighting the challenge of standardization.

Table 2: DNA Yield and Quality from Stool Samples

| Study Reference | Sample Input | Extraction Method | Average DNA Yield (μg/g of stool) | Human DNA Content (%) | Key Challenge Reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protocol (2000) [1] [4] | 2 grams | Phenol/Chloroform Lysis | 9 - 1686 (Highly Variable) | 0.06% - 46% | High variability in total and human DNA yield; presence of PCR inhibitors. |

| Commercial Kit (Patent) [3] | 0.1 - 0.2 grams | Silica-Based Binding with Inhibitor Removal | Not Specified | Not Specified | Neutralization of complex polysaccharides, bilirubin, and bile salts. |

Experimental Protocols for Inhibitor Removal and NA Extraction

Phenol-Chloroform Based DNA Isolation for Large-Scale Studies

This robust protocol is designed for processing large numbers of samples and is independent of the stool collection method, making it suitable for biobanking and population-scale screening [1] [4].

Materials:

- Lysis Buffer: 500 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 100 mmol/L EDTA, 500 mmol/L NaCl [3].

- Lysis Buffer Additives: 2% (w/v) Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) [3], 4 mol/L Guandinium Thiocyanate [3].

- Phenol-Chloroform-Isoamyl Alcohol (25:24:1).

- Glass Beads (100 μm diameter) for mechanical disruption.

- 3 mol/L Sodium Acetate (pH 5.2).

- 100% and 70% Ethanol.

- Nuclease-Free Water.

Procedure:

- Homogenization: Weigh 2 grams of "as dry as possible" stool and suspend in 10 mL of Lysis Buffer. Vortex vigorously for 5 minutes.

- Mechanical Lysis: Add 1 g of glass beads to the suspension and agitate on a mechanical bead-beater for 3 minutes to disrupt tough cell walls and stool matrix.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the lysate at 5,000 x g for 10 minutes at room temperature. Transfer the supernatant to a fresh tube.

- Organic Extraction: Add an equal volume of Phenol-Chloroform-Isoamyl Alcohol to the supernatant. Mix thoroughly by vortexing for 2 minutes. Centrifuge at 12,000 x g for 15 minutes at 4°C.

- DNA Precipitation: Carefully transfer the upper aqueous phase to a new tube. Add 0.1 volumes of 3 mol/L Sodium Acetate and 2 volumes of 100% ethanol. Mix and incubate at -20°C for 1 hour.

- DNA Washing: Centrifuge at 12,000 x g for 15 minutes at 4°C to pellet the DNA. Carefully decant the supernatant and wash the pellet with 5 mL of 70% ethanol. Centrifuge again for 5 minutes and carefully pour off the ethanol.

- DNA Resuspension: Air-dry the pellet for 10-15 minutes and resuspend in 100 μL of nuclease-free water. Quantify DNA using a fluorometric method.

Silica-Binding Protocol with Integrated Inhibitor Neutralization

This method is optimized for automated nucleic acid extraction systems and focuses on purifying DNA while retaining compatibility with sensitive downstream applications like real-time PCR [3].

Materials:

- Inhibitor Removal Buffer: 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 25 mmol/L EDTA, 4.2 mol/L Guandinium Thiocyanate, 2% (w/v) PVP, 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 [3].

- Binding Buffer: 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 4.2 mol/L Guandinium Thiocyanate, 30% (v/v) Isopropanol [3].

- Wash Buffer 1: 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 5.2 mol/L Guandinium Thiocyanate, 60% (v/v) Ethanol [3].

- Wash Buffer 2: 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 80% (v/v) Ethanol, 100 mmol/L NaCl [3].

- Silica-Membrane Binding Columns.

- Nuclease-Free Water.

Procedure:

- Lysis and Inhibitor Binding: Homogenize 0.1-0.2 grams of stool in 1 mL of Inhibitor Removal Buffer. Vortex for 2 minutes. Incubate at 70°C for 5 minutes to enhance inhibitor dissociation.

- Clarification: Centrifuge the lysate at 12,000 x g for 5 minutes to pellet insoluble debris and inhibitor complexes. Transfer the clarified supernatant to a new tube.

- DNA Binding: Add 2 volumes of Binding Buffer to the supernatant and mix by pipetting. Load the mixture onto a silica-membrane column and centrifuge at 11,000 x g for 1 minute. Discard the flow-through.

- Washing: Add 500 μL of Wash Buffer 1 to the column. Centrifuge at 11,000 x g for 1 minute. Discard the flow-through. Add 500 μL of Wash Buffer 2 and repeat the centrifugation. Discard the flow-through.

- Final Wash and Elution: Perform an additional centrifugation step with the empty column for 2 minutes to dry the membrane completely. Elute the DNA by adding 50-100 μL of Nuclease-Free Water to the center of the membrane, incubating for 2 minutes, and centrifuging at 11,000 x g for 1 minute.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful nucleic acid extraction from stool relies on a specific set of reagents designed to lyse cells, protect nucleic acids, and sequester inhibitors.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Stool NA Extraction

| Reagent | Function | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Guandinium Thiocyanate | Chaotropic Salt / Denaturant | Denatures proteins and nucleases, disrupts cell membranes, and inactivates pathogens [3]. |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Inhibitor Binding | Binds to polyphenols and pigments (e.g., heme) via hydrogen bonding, preventing their co-purification with DNA [3]. |

| EDTA (Chelating Agent) | Nuclease Inhibitor | Chelates Mg²⁺ ions, which are essential cofactors for many DNases and RNases, thereby protecting nucleic acids from degradation [3]. |

| Silica-Based Membranes | Nucleic Acid Binding | In the presence of high-concentration chaotropic salts, nucleic acids bind to the silica matrix while impurities are washed away [3]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Precipitation Aid | Acts as a crowding agent to precipitate nucleic acids, often used in larger-scale or metagenomic preparations. |

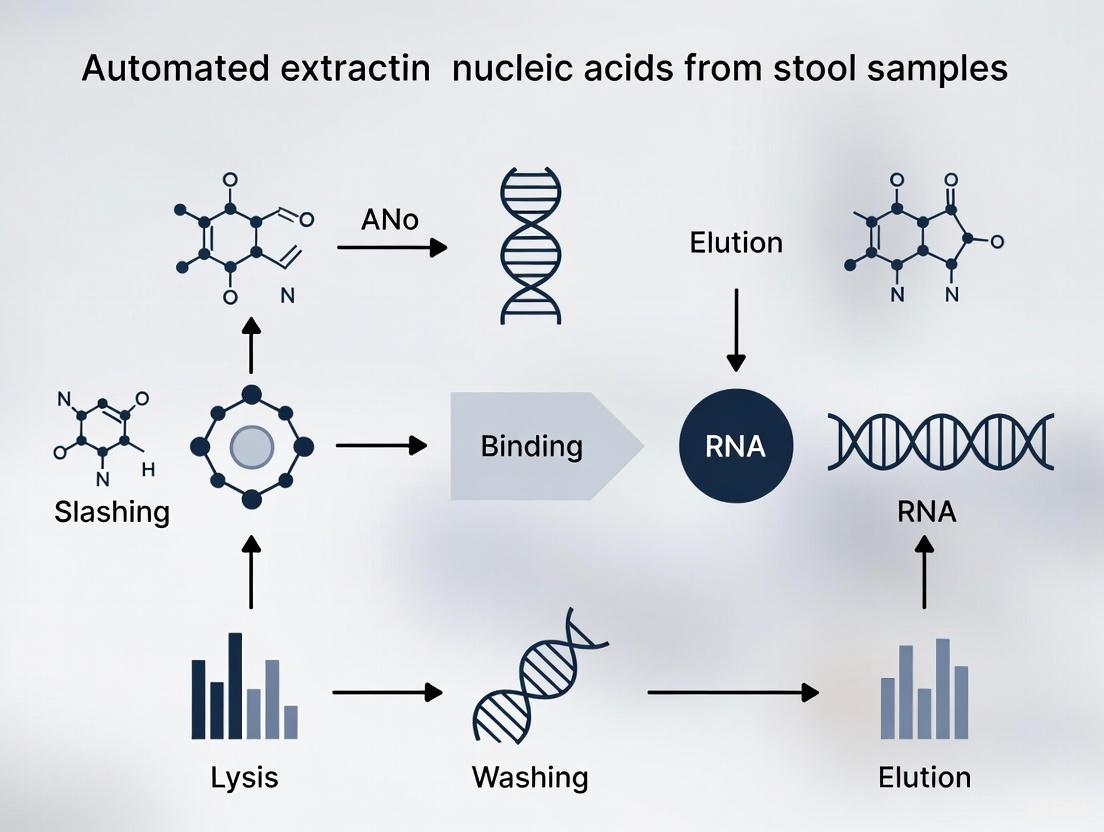

Workflow and Inhibitor Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the complete workflow for nucleic acid extraction from stool and the specific points at which key inhibitors interfere, alongside the corresponding neutralization strategies.

Stool NA Extraction & Inhibition Management Workflow

Application Notes

Automated nucleic acid extraction from stool samples is a cornerstone technique that provides the foundational genetic material for advancements across infectious disease, microbiome research, and oncology. The transition from manual to automated methods significantly enhances throughput, improves reproducibility, and reduces inter-sample variability, which is critical for generating robust data in both research and clinical diagnostics [5].

Application in Infectious Disease

In infectious disease diagnostics, automated extractors enable sensitive and specific detection of viral, bacterial, and fungal pathogens from complex stool samples. The primary challenge is the efficient removal of PCR inhibitors commonly found in stool to ensure reliable downstream molecular detection.

- Viral Detection: Automated systems have been validated for detecting enteric viruses like norovirus and rotavirus. A comparative study of five platforms demonstrated that while all platforms yielded comparable results for norovirus RNA extraction, the performance could be impaired by inhibitory substances in some samples, highlighting the need for optimized inhibitor removal technologies [6]. In another evaluation focusing on rotavirus RNA, extracts prepared using the MagNA Pure Compact instrument yielded the most consistent results in both qRT-PCR and conventional RT-PCR assays [7].

- Bacterial and Fungal Detection: The integration of bead-beating, a mechanical lysis step, is crucial for the effective rupture of tough microbial cell walls, including those of Gram-positive bacteria and fungal spores. Systems like the KingFisher Apex, which incorporate this step, provide a more comprehensive profile of the microbial community in stool, which is essential for diagnosing bacterial and fungal infections [5].

Application in Microbiome Research

The field of microbiome research relies on the unbiased extraction of total nucleic acids to characterize the diverse communities of bacteria, viruses, and fungi inhabiting the human gut. The choice of extraction method directly influences the observed microbial community structure.

- Impact of Lysis Method: The omission of bead-beating can lead to a significant under-representation of Gram-positive bacteria, such as Firmicutes, in subsequent sequencing data. A 2024 study confirmed that bead-beating provided an incremental yield and more effective lysis of stool samples compared to lysis buffer alone, regardless of the automated extractor used [5].

- Quantitative Microbiome Profiling (QMP): Moving beyond relative abundance data, QMP integrates absolute quantification of microbial abundances into sequencing data. This can be achieved by:

- Flow Cytometry (QMP): Counting intact microbial cells using flow cytometry [8].

- PMA Treatment (QMP-PMA): Using propidium monoazide to pre-treat samples before DNA isolation, thereby profiling only the composition of intact cells and excluding free extracellular DNA [8].

- qPCR (QMP-qPCR): A cost-effective alternative that uses qPCR targeting the 16S rRNA gene to quantify the total bacterial load [8].

- Sequencing and Analysis: High-quality DNA extracted by kits like the MagMAX Microbiome kit is compatible with next-generation sequencing applications, including 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomics. This allows researchers to generate species-level profiles to study changes in the microbiome associated with conditions like ulcerative colitis or dietary interventions [9].

Application in Oncology

The gut microbiome is increasingly recognized as a key modulator of cancer development, progression, and response to therapy. Automated nucleic acid extraction from stool enables the study of the microbiome's role in oncogenesis and its potential as a source of biomarkers or therapeutic targets.

- Microbial Drivers of Cancer: An estimated 28.7% of cancers in sub-Saharan Africa are linked to known infectious triggers, including HPV, hepatitis viruses, and H. pylori [10]. Research is now exploring the potential oncogenic roles of other microbes, such as Fusobacterium nucleatum, in various cancers [10].

- The Tumor Microbiome (TM): The TM comprises bacteria, fungi, and viruses within tumor tissues. It can modulate the tumor microenvironment by influencing critical signaling pathways like WNT/β-catenin, NF-κB, and TLRs, thereby affecting cancer progression and response to treatments like immunotherapy [11].

- Mechanisms of Oncogenesis: Microbes can contribute to cancer through multiple mechanisms, including:

Table 1: Comparison of Automated Nucleic Acid Extraction Systems for Stool Samples

| Extractor & Kit | Technology | Throughput (samples/run) | Bead-Beating | Processing Time (for 16 samples) | Key Performance Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KingFisher Apex (MagMAX Microbiome Ultra Kit) | Magnetic Beads | 1–96 | Yes, required | ~40 min | Effective lysis; high-quality DNA for NGS; low inter-sample variability [9] [5] |

| Maxwell RSC 16 (Maxwell RSC Fecal Microbiome DNA Kit) | Magnetic Beads (Pre-packed Cartridges) | 1–16 | Optional | ~42 min | Good yield and purity; performance improved with bead-beating [5] |

| GenePure Pro (MagaBio Fecal Pathogens DNA Purification Kit) | Magnetic Beads (Pre-packed Plate) | 1–32 | Optional | ~35 min | Differences in yield and inter-sample variability observed compared to other systems [5] |

| EZ2 Connect (EZ2 PowerFecal Pro DNA/RNA Kit) | Magnetic Beads (Pre-filled Cartridges) | Up to 24 | Yes, via bead beating | Information Missing | High yields of inhibitor-free DNA/RNA; suitable for PCR and NGS [12] |

Table 2: Quantitative Microbiome Profiling (QMP) Approaches

| Method | Description | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| QMP | Combines flow cytometry cell counting with 16S sequencing. | Overcomes compositional bias of relative abundance data. | Does not capture free extracellular DNA, which can introduce bias if its composition differs from intact cells [8]. |

| QMP-PMA | QMP with propidium monoazide pre-treatment to bind to DNA from dead cells. | Profiles only intact, viable cells. | Adds a processing step; may not penetrate all complex samples equally [8]. |

| QMP-qPCR | Uses qPCR to quantify 16S rRNA gene copies for absolute abundance. | Cost-effective, simple, and accessible. | Lower sensitivity; may only detect 2-fold changes in microbial load [8]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Automated Nucleic Acid Extraction from Stool Using a Magnetic Bead-Based System

This protocol is adapted for systems like the KingFisher Apex with the MagMAX Microbiome Ultra Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit or similar [9] [5].

2.1.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Automated Stool DNA Extraction

| Item | Function | Example Product |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Nucleic Acid Extractor | Performs automated binding, washing, and elution of nucleic acids. | KingFisher Apex, GenePure Pro, Maxwell RSC 16 [5] |

| Extraction Kit | Provides optimized buffers, magnetic beads, and reagents. | MagMAX Microbiome Ultra Kit, Maxwell RSC Fecal Microbiome Kit [9] [5] |

| Lysis Buffer with Inhibitor Removal | Disrupts microbial and stool cells, inactivates nucleases, and begins removal of PCR inhibitors. | Lysis buffer from commercial kits [12] |

| Proteinase K | Digests proteins and degrades nucleases. | Supplied in many kits or purchased separately [5] |

| Magnetic Silica Beads | Bind nucleic acids in the presence of chaotropic salts for purification. | Supplied in magnetic bead-based kits [9] [12] |

| Wash Buffers | Remove salts, proteins, and other impurities from the bound nucleic acids. | Supplied in kits [9] [5] |

| Nuclease-Free Elution Buffer | Releases purified nucleic acids from the magnetic beads into a stable solution. | Low-salt buffer like Tris-EDTA (TE) or kit-supplied elution buffer [9] [5] |

| Bead-Beater/Homogenizer | Mechanically lyses tough microbial cell walls using beads. | Omni Bead Ruptor 96, BeadBug, FastPrep-24 [9] [5] |

| Sample Preservation Reagent | Stabilizes nucleic acids in stool at room temperature during storage/transport. | DNA/RNA Shield [5] |

2.1.2 Procedure

Sample Preparation:

Mechanical Lysis (Bead-Beating):

- Transfer the sample to a tube or plate suitable for bead-beating.

- Perform mechanical homogenization. Example settings from the MagMAX protocol are provided in Table 4 [9].

- Centrifuge the lysate briefly to pellet debris.

Lysate Transfer:

- Transfer a defined volume of supernatant (e.g., 300 µL) to a deep-well plate or the specific plate/cartridge required by the automated extractor [5].

Automated Extraction:

- Load the plate/cartridge onto the instrument along with the necessary reagents (e.g., magnetic beads, wash buffers, elution buffer).

- Select and run the appropriate manufacturer-provided protocol for DNA or total nucleic acid extraction. A typical workflow is illustrated in Diagram 2.

Post-Elution:

- Retrieve the eluted nucleic acids (typically in 50-100 µL elution buffer).

- Quantify the DNA concentration and assess purity using a fluorometer (e.g., Qubit) and spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop), respectively [5].

- Store purified DNA at -80°C until downstream application.

Table 4: Example Bead-Beating Settings for Microbial Lysis [9]

| Instrument | Setting |

|---|---|

| Omni Bead Ruptor 96 | 30 Hz for 2 minutes |

| Mini Bead Beater 96 | 2 minutes |

| Bead Bug | 4 minutes at 4 m/s |

| Vortex with plate adapter | 5 minutes at 2,000 rpm |

Protocol: 16S rRNA Gene Amplicon Sequencing for Microbiome Analysis

This protocol follows the methodology used in the 2024 comparative study [5].

2.2.1 Library Preparation:

- Amplification: Amplify the hypervariable V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene from the extracted DNA using primers 338F (5'-CCTACGGRRBGCASCAGKVRVGAAT-3') and 806R (5'-GGACTACNVGGGTWTCTAATCC-3').

- PCR Conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 3 min.

- 28 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 s.

- Annealing: 55°C for 30 s.

- Elongation: 72°C for 30 s.

- Final Elongation: 72°C for 5 min [5].

- Library Construction: Use a library preparation kit (e.g., Nextera DNA Library Prep Kit) to index the amplicons.

- Sequencing: Pool the indexed libraries and perform sequencing on a platform such as the Illumina MiSeq (2 × 300 bp paired-end).

2.2.2 Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Process raw sequencing reads using a pipeline (e.g., QIIME 2, mothur) to perform quality filtering, denoising, and chimera removal.

- Cluster sequences into Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) or Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs).

- Assign taxonomy using a reference database (e.g., SILVA, Greengenes).

- Perform diversity analysis (alpha and beta-diversity) and differential abundance testing to compare microbial communities between sample groups.

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Automated nucleic acid extraction from stool samples presents a significant challenge in molecular diagnostics and research. Stool is a complex mixture containing a wide range of PCR inhibitors, including bile pigments, complex carbohydrates, and bacterial metabolites [6] [13]. The effectiveness of nucleic acid extraction directly impacts the sensitivity and reliability of downstream applications such as PCR, microarray analysis, and next-generation sequencing [14]. Within the context of a broader thesis on automated extraction, this application note delineates the essential requirements for effective nucleic acid isolation, focusing on the critical triumvirate of purity, yield, and inhibitor removal. Successful extraction must deliver nucleic acids free from contaminants that interfere with enzymatic reactions, provide sufficient yield for intended applications, and effectively remove substances that inhibit amplification [14].

Key Requirements for Effective Extraction

The table below summarizes the core parameters and their significance in automated nucleic acid extraction from stool samples.

Table 1: Essential Requirements for Effective Nucleic Acid Extraction from Stool Samples

| Requirement | Description | Impact on Downstream Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Purity | Absence of contaminants (e.g., proteins, salts, organic compounds) that absorb at 260 nm or inhibit enzymes. | Essential for accurate spectrophotometric quantification and robust performance in PCR and sequencing [15]. |

| Yield | The total amount of nucleic acid recovered from the starting sample. | Critical for detecting low-abundance targets and enabling multiple downstream analyses from a single extraction [16]. |

| Inhibitor Removal | Effective elimination of stool-specific inhibitors such as bile salts, complex polysaccharides, and heme. | Paramount for achieving high sensitivity in molecular diagnostics, as inhibitors can cause false-negative results [6] [17]. |

| Integrity | Preservation of nucleic acid fragment length and structure. | Important for long-range PCR and sequencing applications that require high-molecular-weight DNA [15]. |

| Automation Compatibility | Suitability for integration into automated, high-throughput workflows. | Reduces hands-on time, minimizes human error, and increases reproducibility in research and clinical settings [18]. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol: Evaluating Extraction Efficiency and Inhibitor Removal

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used to validate and optimize automated extraction systems for complex samples [6] [17].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Obtain stool samples from healthy donors and homogenize in a suitable buffer (e.g., PBS or commercial stool transport medium).

- Spike samples with a known quantity of an exogenous control (e.g., a non-human pathogen or synthetic nucleic acid) prior to extraction to monitor recovery efficiency.

- Aliquot samples for parallel extraction across different platforms or conditions.

2. Automated Nucleic Acid Extraction:

- Platform Examples: Systems such as NucliSENS easyMAG (bioMerieux), MagNA Pure (Roche), or QiaSymphony (Qiagen) can be employed [6].

- Lysis: Use a lysis buffer containing a strong chaotropic agent like guanidinium thiocyanate. For robust lysis of hardy organisms (e.g., spores, fungi), incorporate a mechanical disruption step using a bead beater (e.g., 2-5 minutes at high speed) prior to automation [17] [19].

- Extraction: Follow manufacturer-recommended protocols. A key parameter to optimize is the input volume of magnetic silica beads; for high-density samples, 140 µL may be superior to 50 µL for maximizing yield [17].

- Elution: Elute nucleic acids in a low-salt buffer (e.g., TE buffer or nuclease-free water) at a pH >8.0, using a small volume (e.g., 50-100 µL) to maximize concentration [17].

3. Downstream Quantification and Qualification:

- Spectrophotometry: Measure A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios to assess purity. Ideal ratios are ~1.8 and >2.0, respectively [15].

- Fluorometry: Use dye-based quantification (e.g., Qubit) for a more accurate measurement of nucleic acid concentration, as it is less affected by contaminants.

- qPCR: Perform quantitative PCR targeting a ubiquitous bacterial gene (e.g., 16S rRNA) and the spiked exogenous control. The cycle threshold (Ct) values allow for the relative quantification of yield and direct assessment of PCR inhibition. A significant delay in the Ct of the spiked control in sample extracts versus a clean control indicates the presence of residual inhibitors [6] [17].

Workflow: Automated NA Extraction from Stool

The following diagram illustrates the optimized workflow for automated nucleic acid extraction from stool samples, integrating key steps for ensuring purity, yield, and effective inhibitor removal.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for successful automated nucleic acid extraction from challenging stool samples.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Automated NA Extraction

| Item | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Silica Beads | Solid-phase matrix that binds nucleic acids in the presence of chaotropic salts. | The surface area and concentration of beads are critical; higher bead volumes (e.g., 140 µL) improve yield from inhibitor-rich samples [17]. |

| Chaotropic Lysis Buffer | Disrupts cells, inactivates nucleases, and enables nucleic acid binding to silica. | Guanidinium thiocyanate-based buffers are highly effective for denaturing proteins and inactivating pathogens in stool samples [16] [17]. |

| Inhibitor Removal Buffers | Wash buffers designed to remove specific classes of contaminants. | A wash with a buffer containing guanidinium maintains binding stringency, while a final high-salt ethanol wash removes residual salts and other impurities [17]. |

| Bead-Beating Tubes | Tubes containing ceramic or glass beads for mechanical disruption. | Essential for breaking down hardy structures like fungal cell walls, protozoan cysts, and bacterial spores in stool prior to automated extraction [17] [19]. |

| External Positive Control | A known quantity of non-target nucleic acid spiked into the sample. | Used to monitor extraction efficiency and detect the presence of PCR inhibitors by comparing Cq values to a clean extraction [6] [17]. |

Performance Data and Comparison

Comparative studies of automated extraction platforms provide critical insights into their performance with stool samples. The following table summarizes quantitative data from a study comparing five automated systems for the extraction of viral RNA from stool.

Table 3: Comparison of Automated Extraction Platforms for Norovirus RNA from Stool [6]

| Extraction Platform | Total Samples (n=39) | Samples Positive on All Platforms | Notes on Inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|

| easyMAG (bioMerieux) | 39 | 36 | Some samples showed inhibition. |

| m2000sp (Abbott) | 39 | 36 | Some samples showed inhibition. |

| MagNA Pure LC 2.0 (Roche) | 39 | 36 | Some samples showed inhibition. |

| QiaSymphony (Qiagen) | 39 | 36 | Some samples showed inhibition. |

| VERSANT kPCR (Siemens) | 39 | 39 | All samples tested positive for both target and internal control. |

Optimization of established methods can lead to significant improvements. Recent research on a magnetic silica bead-based method (SHIFT-SP) demonstrated that adjusting the binding buffer to a lower pH (4.1 versus 8.6) dramatically increased DNA binding efficiency from 84.3% to 98.2% [16]. Furthermore, replacing orbital shaking with a rapid "tip-based" mixing method reduced the binding time from 5 minutes to 1 minute while achieving superior yield, highlighting the impact of optimizing physical parameters in addition to chemical ones [16]. For stool samples, the MagMAX Microbiome kit, which employs bead-beating lysis and magnetic bead-based purification, has been shown to effectively isolate high-quality total nucleic acids compatible with downstream qPCR and NGS applications, as evidenced by clear electrophoretic bands and high RIN scores [19].

The analysis of nucleic acids from stool samples is a cornerstone of modern molecular research, enabling advancements in areas ranging from human microbiome studies to non-invasive cancer detection. Stool represents one of the most complex sample matrices, containing a diverse mixture of microorganisms, host cells, dietary residues, and potent PCR inhibitors. The evolution of nucleic acid extraction technologies from manual protocols to sophisticated automated systems has been driven by the need for higher throughput, improved reproducibility, and more robust results in the face of these challenges. This evolution is particularly critical for large-scale studies and clinical applications where batch effects and inter-sample variation can confound biological interpretations [5] [20]. The transition to automation represents not merely a convenience but a fundamental methodological shift that enhances data quality and reliability while accommodating the increasing scale of biomedical research.

The Technological Shift: From Manual to Automated Extraction

Limitations of Manual Extraction Methods

Traditional manual extraction methods, often based on silica spin columns or phenol-chloroform phase separation, present significant limitations for high-throughput stool analysis. These methods are labor-intensive, time-consuming, and susceptible to human error and inter-operator variability. The FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil, a commonly used manual method for challenging samples like stool, requires approximately 100 minutes of hands-on processing time for just 16 samples and involves multiple centrifugation, incubation, and transfer steps that introduce opportunities for contamination and inconsistency [5] [20]. Additionally, manual methods struggle with the efficient lysis of diverse microbial communities in stool, particularly robust Gram-positive bacteria and bacterial spores, without incorporating dedicated mechanical disruption steps [20].

Advantages of Automated Magnetic Bead-Based Systems

Automated nucleic acid extraction systems have primarily standardized around magnetic bead-based technology, which offers several fundamental advantages for stool analysis:

- Higher Purity and Yields: Magnetic beads provide exceptional binding capacity with thorough exposure to target molecules during mixing and washing steps, allowing for efficient capture and release of nucleic acids [21].

- Enhanced Reproducibility: Standardized protocols involving fewer steps enable consistent and reproducible results with reduced processing time and minimal technical variation [21] [5].

- Scalability and Flexibility: Automation compatibility facilitates high-throughput processing, with systems capable of handling from 16 to 384 samples per run [21] [22].

- Gentle Separation: Without columns, filters, and excessive centrifugation, the technology minimizes potential clogging and helps prevent shearing of sensitive biomolecules [21].

- Superior Inhibitor Removal: Specialized chemistries and wash buffers effectively remove PCR inhibitors common in stool samples, such as bile salts and complex polysaccharides [12] [23].

The Critical Role of Bead-Beating in Stool Analysis

A key consideration in automating stool nucleic acid extraction is the integration of effective mechanical lysis. Research demonstrates that bead-beating provides incremental yield by effectively lysing a broader representation of microbial cells in stool samples compared to chemical lysis buffer alone [5] [20]. Differential abundance analysis reveals a greater representation of Gram-positive bacteria in samples subjected to mechanical lysis, regardless of the automated extraction system used [20]. This finding is significant because inadequate lysis of Gram-positive bacteria can introduce substantial bias in microbiome studies, potentially missing important biological signatures. While not all automated systems incorporate onboard bead-beating, many protocols now include this as a essential pre-processing step to ensure comprehensive lysis of the diverse microbial communities present in stool [20].

Comparative Performance of Automated Extraction Systems

System Comparisons and Technical Specifications

Recent methodological comparisons provide valuable insights into the performance characteristics of different automated platforms for stool analysis. A 2024 systematic evaluation compared three commercial nucleic acid extractors—Bioer GenePure Pro, Promega Maxwell RSC 16, and Thermo Fisher KingFisher Apex—using both human fecal samples and mock microbial communities [5] [20]. The study assessed DNA yield, DNA purity, and 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing results, revealing important differences in system performance and downstream applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Automated Nucleic Acid Extraction Systems for Stool Samples

| Extraction System | Throughput (samples/run) | Processing Time (for 16 samples) | Bead-Beating Compatibility | Technology Platform | Key Applications Demonstrated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioer GenePure Pro | 1-32 | ~35 minutes | External (required) | Magnetic bead-based | Microbiome analysis, pathogen detection [5] |

| Promega Maxwell RSC 16 | 1-16 | ~42 minutes | External (required) | Magnetic bead-based | Microbiome analysis, sequential DNA/RNA isolation [5] [21] |

| Thermo Fisher KingFisher Apex | 1-96 | ~40 minutes | Integrated or external | Magnetic bead-based | High-throughput microbiome, virome studies [5] [21] |

| QIAGEN EZ2 Connect | 1-24 | Protocol-dependent | Integrated (Tissuelyser) | Magnetic particle technology | Microbial DNA/RNA, total nucleic acids [12] |

| MGI MGISP-NE384 | 96-384 | High-throughput | External | Magnetic rod technology | Large-scale epidemiology, biobanking [22] |

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The performance evaluation of automated systems reveals critical differences in extraction efficiency, purity, and downstream analytical outcomes. When comparing DNA yield across systems, the EZ2 PowerFecal Pro DNA/RNA Kit demonstrated the highest DNA yields across four different stool samples compared to alternative suppliers [12]. In the three-system comparison, all automated extractors showed differences in terms of yield, inter-sample variability, and subsequent sequencing readouts [20]. These technical differences translated into meaningful variations in 16S rRNA gene amplicon results, highlighting the importance of selecting appropriate extraction methods for specific research applications.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Automated Extraction Systems for Stool Analysis

| Performance Metric | KingFisher Apex | Maxwell RSC 16 | GenePure Pro | Manual Column-Based |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average DNA Yield | Variable by kit | Variable by kit | Variable by kit | Baseline reference [20] |

| Inter-Sample Variability | Lower | Lower | Lower | Higher [5] [20] |

| Process Contamination | Reduced (closed system) | Reduced (closed system) | Reduced (closed system) | More frequent [5] |

| Gram-positive Bacteria Representation | Higher with bead-beating | Higher with bead-beating | Higher with bead-beating | Dependent on protocol [20] |

| Downstream Sequencing Quality | High with appropriate kit | High with appropriate kit | High with appropriate kit | Variable [20] |

| Sample Preparation Time (16 samples) | ~40 minutes | ~35 minutes | ~25 minutes | ~100 minutes [5] |

Specialized Applications and Methodological Adaptations

Different research applications require specialized approaches to nucleic acid extraction from stool:

Virome Studies: Research on the DNA virome from fecal samples often employs specialized protocols for virus-like particle (VLP) enrichment prior to nucleic acid extraction. This typically involves filtration through 0.45 µm and 0.22 µm filters, treatment with DNase to remove free DNA, and subsequent phenol-chloroform extraction [24]. Such specialized procedures demonstrate that even with automated platforms, certain applications require tailored pre-processing steps.

RNA Extraction for Cancer Biomarkers: The detection of colorectal cancer-associated immune genes in stool requires optimized RNA extraction protocols. A 2024 study found that a combination of the Stool total RNA purification kit (Norgen) with the Superscript III one-step RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen) provided high RNA purity and sensitive mRNA detection [25]. The low abundance of human mRNA in stool, relative to microbial RNA, necessitates very sensitive approaches with high specificity to avoid cross-reactivity.

Inhibitor Removal Technologies: Advanced materials are being developed to address the challenge of PCR inhibitors in stool. A 2025 study demonstrated that Fe-doped mesoporous silica nanoparticle (Fe-MSN) columns provided more efficient extraction than conventional methods, yielding higher RNA purity and lower Ct values in RT-PCR [23]. This emerging technology showed a 5-fold decrease in the Ct value of different studied genes compared to a commercial extraction kit.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Automated DNA Extraction for Microbiome Analysis

Protocol Title: Automated DNA Extraction from Human Stool Samples for 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

Principle: This protocol utilizes magnetic bead-based technology to isolate high-quality genomic DNA from human stool samples, suitable for downstream applications including qPCR and next-generation sequencing. The method incorporates mechanical bead-beating for comprehensive lysis of diverse microbial populations [5] [20].

Materials and Reagents:

- Stool samples preserved in DNA/RNA Shield or similar preservation reagent

- MagMAX Microbiome Ultra Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or equivalent

- KingFisher Apex System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or compatible automated extractor

- FastPrep-24 5G Bead Beating Grinder (MP-Biomedicals) or equivalent

- DNA/RNA Shield Fecal Collection Tubes (Zymo Research Corp)

- Nuclease-free water

- Ethanol (96-100%)

- Microcentrifuge tubes (1.5-2 mL)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Thaw frozen fecal samples at room temperature. For each sample, aliquot 300 µL of fecal DNA shield mixture into a lysing matrix tube containing silica beads.

- Mechanical Lysis: Homogenize samples using the FastPrep-24 system at 6.0 m/s for 40 seconds to ensure comprehensive disruption of microbial cells, including difficult-to-lyse Gram-positive bacteria.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the lysate at 14,000 × g for 5 minutes to pellet debris while leaving nucleic acids in the supernatant.

- Automated Extraction Setup: Transfer 200 µL of supernatant to a deep-well plate compatible with the automated extraction system. Add recommended volumes of lysis/binding solution, magnetic beads, and wash buffers according to kit specifications.

- Automated Extraction: Run the appropriate program on the automated extractor (e.g., KingFisher Apex). Typical programs include:

- Binding incubation: 10-15 minutes with mixing

- Two wash steps with wash buffers

- Drying step: 5 minutes

- Elution: 5 minutes in nuclease-free water or low-EDTA TE buffer

- DNA Quantification and Quality Assessment: Measure DNA concentration using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS assay) and purity using spectrophotometry (e.g., NanoDrop). Store purified DNA at -80°C until library preparation.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Low DNA yield may indicate insufficient bead-beating or incomplete sample homogenization

- High inhibitor carryover may require additional wash steps or dilution of extracts

- For difficult samples, increasing the bead-beating time or using smaller bead sizes may improve lysis efficiency

Automated RNA Extraction for Gene Expression Analysis

Protocol Title: Automated RNA Extraction from Stool for mRNA Biomarker Detection

Principle: This protocol isolates high-quality total RNA from stool samples for detection of human mRNA transcripts, enabling non-invasive monitoring of colorectal cancer-associated immune genes. The method combines effective inhibitor removal with preservation of labile RNA molecules [25].

Materials and Reagents:

- Stool samples preserved in RNAlater

- EZ2 PowerFecal Pro DNA/RNA Kit (QIAGEN) or equivalent

- EZ2 Connect Instrument (QIAGEN)

- RNase-free DNase Set (for DNA-only removal)

- β-mercaptoethanol

- Ethanol (96-100%)

- Nuclease-free water

Procedure:

- Sample Homogenization: Weigh 50-100 mg of stool and transfer to a tube containing lysis buffer and β-mercaptoethanol. Homogenize thoroughly using a vortex mixer with beads or a commercial homogenizer.

- Inhibitor Removal: Add the proprietary inhibitor removal solution and mix thoroughly. Centrifuge to pellet inhibitors and transfer the supernatant to a new tube.

- Automated Extraction Setup: Load the supernatant onto the EZ2 Connect cartridge along with the appropriate reagents for RNA isolation. For DNA-free RNA, ensure DNase is included in the protocol.

- Automated Extraction: Run the RNA isolation protocol on the EZ2 Connect system. The automated process includes:

- Nucleic acid binding to magnetic particles

- Optional DNase digestion (if selecting for RNA only)

- Multiple wash steps to remove contaminants

- Elution in RNase-free water

- RNA Quality Assessment: Measure RNA concentration using fluorometry (e.g., Qubit RNA HS assay) and purity using spectrophotometry. Assess RNA integrity if necessary using automated electrophoresis systems.

- Downstream Application: Use purified RNA immediately in RT-PCR reactions or store at -80°C for future use.

Application Notes:

- This protocol has been successfully used to detect immune genes (CXCL1, IL8, IL1B, IL6, PTGS2, and SPP1) in colorectal cancer research [25]

- For optimal results, process samples immediately after collection or ensure proper preservation in RNAlater

- Include appropriate negative controls to monitor for contamination during extraction

Workflow Visualization: Automated Nucleic Acid Extraction from Stool

Automated Stool Nucleic Acid Extraction Workflow

This workflow diagram illustrates the integrated process of automated nucleic acid extraction from stool samples, highlighting the manual pre-processing requirements, the fully automated extraction steps, and the essential quality control procedures necessary for successful downstream applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Automated Nucleic Acid Extraction from Stool

| Product Name | Manufacturer | Primary Application | Key Features | Compatible Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MagMAX Microbiome Ultra Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | DNA extraction from microbiome samples | Optimized for difficult-to-lyse bacteria; inhibitor removal technology | KingFisher systems [21] [20] |

| EZ2 PowerFecal Pro DNA/RNA Kit | QIAGEN | Simultaneous DNA/RNA extraction | Second-generation Inhibitor Removal Technology; pre-filled cartridges | EZ2 Connect [12] |

| Maxwell RSC Fecal Microbiome DNA Kit | Promega | DNA for microbiome analysis | Efficient lysis chemistry; minimal cross-contamination | Maxwell RSC [5] |

| MagaBio Fecal Pathogens DNA Purification Kit | Bioer Technology | Pathogen detection | Comprehensive pathogen lysis; high sensitivity | GenePure Pro [5] |

| Stool total RNA purification kit | Norgen Biotech | RNA for gene expression | Effective eukaryotic RNA recovery; DNase treatment | Multiple systems [25] |

| NucliSENS EasyMAG system | BioMérieux | RNA for viral detection | Generic protocol for stool; magnetic silica | EasyMAG [25] |

The evolution from manual to automated nucleic acid extraction technologies has fundamentally transformed stool-based molecular research, enabling the high-throughput, reproducible analyses required for modern biomedical science. Automated magnetic bead-based systems address the specific challenges posed by complex stool matrices while providing the scalability needed for large-scale studies. The integration of mechanical bead-beating, advanced inhibitor removal technologies, and standardized protocols has significantly improved the representation of diverse microbial communities and the detection of host biomarkers in stool. As research continues to advance, further innovations in automation, miniaturization, and materials science will continue to enhance our ability to extract meaningful biological information from this challenging but invaluable sample type. The methodologies and systems detailed in this application note provide researchers with the foundational knowledge needed to select and implement appropriate automated extraction strategies for their specific stool-based research applications.

Current Automated Platforms and Emerging Technologies in Practice

Within research frameworks focusing on the automated extraction of nucleic acids from stool samples, solid-phase extraction utilizing magnetic beads has emerged as the dominant methodology. Stool samples represent one of the most complex and challenging sample types, characterized by the presence of extensive PCR inhibitors such as bile salts and complex carbohydrates [14]. Efficient extraction of high-quality nucleic acid is therefore a critical pre-analytical step for downstream applications including qPCR, next-generation sequencing, and microbiome analysis [21]. Magnetic bead-based technology has been widely adopted in this context due to its advantages in automation compatibility, scalability, and ability to deliver high-purity nucleic acids free from common inhibitors found in stool [14] [21].

Core Principles and Advantages

The fundamental principle of magnetic bead-based nucleic acid extraction involves the use of silica-coated magnetic particles that bind nucleic acids in the presence of chaotropic salts [14]. The process can be broken down into four key stages, which are easily integrated into automated liquid handling platforms:

- Lysis: Chemical and/or mechanical disruption of sample cells and viruses to release nucleic acids.

- Binding: Introduction of magnetic beads in a high-salt buffer, promoting the adsorption of nucleic acids onto the silica surface of the beads.

- Washing: Application of a magnetic field to immobilize the bead-nucleic acid complexes while contaminants are removed with wash buffers. This step is crucial for removing PCR inhibitors from complex samples like stool.

- Elution: Resuspension of the purified beads in a low-ionic-strength buffer or water, causing the nucleic acids to dissociate and enter the solution, resulting in a pure eluate [14] [21].

The transition to this method from older techniques is driven by its distinct advantages, particularly for challenging samples and high-throughput environments.

Table 1: Comparison of Nucleic Acid Extraction Methods

| Feature | Phenol-Chloroform | Column-Based Silica | Magnetic Beads (Automated) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Liquid-phase separation, alcohol precipitation [14] | Solid-phase on silica membrane [14] | Solid-phase on silica-coated magnetic particles [14] [21] |

| Automation Potential | Low | Moderate | High |

| Throughput | Low | Low to Moderate | High to Very High |

| Risk of Contamination | High | Moderate | Low |

| Hands-on Time | High | Moderate | Low |

| Suitability for Complex Samples (e.g., Stool) | Poor (inefficient inhibitor removal) | Moderate | Excellent (efficient washing) [21] |

| Shearing Risk | High (due to vigorous mixing) | Moderate (from centrifugation) | Low (gentle mixing) [21] |

Detailed Protocol for Stool Samples

The following protocol is adapted for automated extraction of nucleic acids from stool samples using a magnetic bead-based system, such as the KingFisher system paired with a dedicated kit (e.g., MagMAX Microbiome Kit) [21].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Automated Purification System | e.g., KingFisher System. Instrument that moves magnetic beads through various solutions for hands-free purification [21]. |

| Magnetic Bead Kit for Microbiome | e.g., MagMAX Microbiome Kit. Provides optimized buffers and magnetic beads for efficient lysis and purification from complex samples [21]. |

| Lysis Buffer (with Beads) | Contains chaotropic salts to promote nucleic acid binding to beads and other reagents to begin breaking down sample matrix [21]. |

| Wash Buffers | Typically two washes: one with a salt-ethanol solution to remove contaminants, and a second with ethanol to remove residual salts [14] [21]. |

| Elution Buffer | Low-ionic-strength solution (e.g., TE buffer or nuclease-free water) that causes nucleic acids to release from the beads into the solution [14]. |

| Proteinase K | Enzyme added to lysis buffer to digest proteins and enhance cell wall breakdown, especially for Gram-positive bacteria in stool [14] [26]. |

| Bead-Beating Tubes | Tubes containing mechanical beads for homogenization. Critical for disrupting tough bacterial and fungal cell walls in stool microbiota. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

Pre-processing (Manual):

- Sample Homogenization: Suspend a small aliquot (~100-200 mg) of stool in an appropriate transport or lysis buffer. Vortex thoroughly.

- Mechanical Lysis: Transfer an aliquot (e.g., 200 µL) of the homogenate to a bead-beating tube. Homogenize using a Precellys homogenizer or similar (e.g., 3 x 15 s at 10,000 rpm with 10 s intervals) to ensure complete disruption of microbial cells [26].

- Clarification: Centrifuge the lysate briefly at low speed (e.g., 1500 × g for 30 s) to pellet large debris, including undigested food particles and toilet paper common in stool samples [26]. The supernatant is used for automated extraction.

Automated Extraction (on KingFisher System):

- Plate Setup: In a deep-well plate, prepare the following in sequence:

- Well 1: Sample supernatant from the pre-processing step.

- Well 2: Binding solution/Bead mix (magnetic beads in chaotropic salt solution).

- Well 3 & 4: Wash Buffer I and Wash Buffer II.

- Well 5: Elution Buffer.

- Run Method: The automated method follows the logic in the workflow diagram below. The instrument uses a magnetic comb to transfer beads through each solution.

- Eluate Collection: The final eluate (in Well 5) contains purified nucleic acids, ready for quantification and downstream analysis.

Automated Workflow Visualization

Experimental Data and Application

The performance of different extraction protocols can be quantitatively assessed by measuring the yield and detection of specific genetic targets. A recent study evaluating extraction protocols for antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in complex wastewater samples provides a relevant model for stool analysis [26].

Table 3: Exemplary Experimental Data Comparing Extraction Protocols for ARG Detection

| Extraction Protocol (EP) | Kit / Method | Sample Input Volume | Target ARG | Mean Concentration (Copies/mL) | Detection Consistency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP1 | DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit [26] | 0.2 mL | tetA | 1.20 x 10⁵ | High |

| EP4 | DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (with TP removal) [26] | 1.5 mL | tetA | 1.05 x 10⁵ | High |

| EP1 | DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit [26] | 0.2 mL | ermB | 9.80 x 10⁴ | High |

| EP5 | AllPrep PowerViral DNA/RNA Kit [26] | 0.2 mL | qnrS | 4.50 x 10³ | Moderate |

| EP10 | AllPrep PowerViral DNA/RNA Kit (with Trizol) [26] | 1.5 mL | qnrS | 5.10 x 10³ | High |

Key Findings from Experimental Data:

- Small Volume Sufficiency: Protocols EP1 and EP5 demonstrate that a starting aliquot as low as 0.2 mL can be sufficient for consistent detection of highly abundant targets, a critical consideration for limited or precious stool samples [26].

- Inhibitor Removal: The high detection consistency for targets like tetA and ermB across different protocols based on magnetic beads highlights the method's efficiency in removing PCR inhibitors, even from complex matrices [26].

- Protocol Optimization: The use of specific additives, such as Trizol in EP10, can enhance the lysis of tough pathogens and improve the detection yield of certain targets, indicating that protocols may be tailored to the specific microbial community or target of interest [26].

Solid-phase extraction with magnetic beads provides a robust, scalable, and efficient foundation for automated nucleic acid purification from stool samples. Its dominance in modern research workflows is justified by the superior purity of the output, the significant reduction in hands-on time, and the direct compatibility with high-throughput instrumentation. As molecular techniques like qPCR and metagenomic sequencing continue to advance, the optimized and automated protocols enabled by magnetic bead technology will remain indispensable for generating reliable and reproducible data in microbiome and pathogen detection research.

The extraction of nucleic acids from complex biological samples like stool is a critical preparatory step in molecular diagnostics and genomics research. The presence of potent PCR inhibitors and diverse microbial communities in stool samples makes them one of the most challenging matrices for nucleic acid isolation. In recent years, functionalized magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) have emerged as a superior substrate for solid-phase nucleic acid extraction, enabling automation, high throughput, and excellent recovery of both DNA and RNA. Among these, iron oxide-based nanoparticles, particularly magnetite (Fe₃O₄), form the core of these systems due to their favorable superparamagnetic properties, which allow them to be dispersed in a solution for efficient binding and then collected using an external magnetic field without retaining residual magnetism. This application note details the use of advanced substrates, with a focus on silica-coated iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe₃O₄@SiO₂), for automated nucleic acid extraction from stool samples, providing researchers with detailed protocols and performance data to enhance their diagnostic and research workflows.

Material Properties and Characterization

Core Magnetic Particle Synthesis and Functionalization

The performance of magnetic nanoparticles in nucleic acid extraction is fundamentally governed by their synthesis and surface functionalization. The core Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles are typically synthesized via methods such as the polyol process or co-precipitation, which allow for control over morphology, size, and magnetic properties [27] [28]. A critical advancement for application in stool samples is the surface coating of these magnetic cores, which enhances stability, prevents agglomeration, and provides functional groups for nucleic acid binding.

Key coatings include:

- Silica (SiO₂): Coating via the Stöber method introduces a surface rich in silanol groups that facilitate DNA binding in the presence of chaotropic salts [27] [29]. The silica coating creates a protective layer that shields the magnetic core from the harsh chemical environment sometimes present in stool lysates.

- Polyethyleneimine (PEI): A polymer coating that provides a high density of positively charged amine groups, enabling strong electrostatic interaction with the negatively charged phosphate backbone of nucleic acids. A comparative study found Fe₃O₄@PEI to be the most efficient nano-sorbent for dsDNA extraction [30].

- Oleic Acid (OA): Often used as an initial surfactant coating to stabilize naked Fe₃O4 nanoparticles and provide a foundation for subsequent silica coating (Fe₃O₄@OA@SiO₂) [29].

Table 1: Characteristics of Functionalized Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Nucleic Acid Extraction

| Material/Coating | Core Synthesis Method | Key Coating Properties | Primary Interaction with Nucleic Acids | Key Advantage for Stool Samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe₃O₄@SiO₂ | Polyol, Co-precipitation | Silanol groups, hydrophilic | Electrostatic, cation-bridging with chaotropes | Robustness against inhibitors, high purity yields [27] [29] |

| Fe₃O₄@PEI | Co-precipitation | High-density amine groups, cationic | Direct electrostatic binding | Highest DNA adsorption efficiency, works in low-EDTA buffers [30] |

| Fe₃O₄@OA@SiO₂ | Ultrasound-assisted co-precipitation | Bilayer: hydrophobic OA + hydrophilic SiO₂ | Silanol-mediated (as above) | Enhanced stability and nucleic acid absorption vs. OA-only [29] |

| Gold-coated | Not Specified | Gold surface chemistry | Not Specified | Evaluated for DNA extraction, less efficient than PEI [30] |

Magnetic and Physical Properties

The synthesized nanoparticles must be characterized to ensure quality and performance. Key analyses include:

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Used to confirm particle size and morphology. For instance, Fe₃O₄@OA@SiO₂ particles showed a mean diameter of 106 nm with a clear core-shell structure [29].

- Vibrating Sample Magnetometry (VSM): Confirms superparamagnetic behavior, characterized by high magnetic saturation and no magnetic remanence. This ensures particles will not aggregate after the magnetic field is removed [29].

- Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy: Verifies the success of surface functionalization by identifying characteristic chemical bonds, such as the Si-O-Si stretch for silica coatings or the carbonyl stretch for oleic acid [27] [29].

Performance Evaluation in Nucleic Acid Extraction

Quantitative Extraction Efficiency

The efficacy of different functionalized MNPs has been quantitatively evaluated in multiple studies. Silica-coated MNPs have demonstrated high efficiency, with one study showing that 0.5 mg of silica-coated Fe₃O₄ particles could yield an average of 2.88 μg of nucleic acids [27]. Furthermore, the purity and integrity of the isolated nucleic acids are suitable for demanding downstream applications, including PCR and next-generation sequencing.

In a comprehensive comparative evaluation of Fe₃O₄-based sorbents with different coatings (PEI, gold, silica, and graphene oxide), Fe₃O₄@PEI MNPs were identified as the most efficient nano-sorbents for dsDNA extraction [30]. The study also highlighted that optimizing the extraction buffer, specifically using a medium containing 0.1 mM EDTA, improved the validity of spectroscopic DNA recovery determination by minimizing Fe³⁺ stripping.

When isolating DNA from complex samples like cyanobacteria (Arthrospira platensis) and animal blood, Fe₃O₄@OA@SiO₂ produced 1.2 and 1.6 times greater DNA yield, respectively, compared to Fe₃O₄@OA, underscoring the advantage of the silica coating for nucleic acid adsorption [29].

Comparative Performance in Automated Systems and Challenging Samples

For automated, high-throughput diagnostics, consistency across production batches is paramount. Scaling up the synthesis of TEOS-modified magnetic particles from 1 L to 5 L has been shown to be feasible, with minimal batch-to-batch variability in DNA extraction performance, ensuring reproducible results in clinical settings [28].

For challenging stool samples, inhibitor removal is critical. A study on rotavirus RNA detection in stool compared six extraction methods and found that extracts from the MagNA Pure Compact system (which utilizes magnetic particle technology) provided the most consistent results in qRT-PCR and conventional RT-PCR, with effective removal of inhibitors [7]. Another broader study on respiratory pathogens found that while all evaluated automated magnetic-bead systems recovered nucleic acids effectively, their performance varied in a pathogen-specific manner, suggesting that the choice of system can be optimized for particular targets [31].

Table 2: Performance Summary of Magnetic Particle-Based Extraction Methods

| Extraction System / Material | Sample Type | Reported Performance Metric | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe₃O₄@PEI MNPs | Model DNA systems | DNA Adsorption Efficiency | Most efficient nano-sorbent among coatings tested [30] |

| Silica-coated Fe₃O₄ | Model DNA/RNA systems | Nucleic Acid Yield | 0.5 mg particles yielded 2.88 (2.67–3.08) μg of nucleic acids [27] |

| Fe₃O₄@OA@SiO₂ | Arthrospira platensis, Blood | DNA Yield (Relative Increase) | 1.6x greater DNA from blood vs. Fe₃O₄@OA [29] |

| MagNA Pure Compact | Stool (Rotavirus) | PCR Consistency & Inhibitor Removal | Most consistent qRT-PCR results; effective inhibitor removal [7] |

| Scaled-up TEOS-MPs | Plasma (Viral NA) | Batch-to-Batch Reproducibility | Minimal variability in DNA extraction with scaled-up synthesis [28] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Automated Nucleic Acid Extraction from Stool Samples Using Functionalized Magnetic Particles

This protocol is adapted for use with an automated nucleic acid extractor (e.g., MagNA Pure, KingFisher) and functionalized silica-coated magnetic particles.

I. Reagents and Materials

- Lysis Buffer: 4-6 M guanidine hydrochloride, 10 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.6), 1% Triton X-100.

- Wash Buffer 1: 4 M guanidine hydrochloride, 20 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.6), and 50% ethanol.

- Wash Buffer 2: 70% ethanol, 10 mM KCl, 2 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5).

- Elution Buffer: Nuclease-free water or 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5).

- Proteinase K (optional, for enhanced lysis).

- Functionalized Silica Magnetic Particles (e.g., Fe₃O₄@SiO₂ suspension).

II. Equipment

- Automated Magnetic Particle Processor (e.g., MagNA Pure Compact, KingFisher Flex).

- Microcentrifuge tubes or deep-well plates compatible with the automated system.

- Vortex mixer and heating block (for pre-processing).

- Magnetic stand (if manual steps are involved).

III. Procedure

- Sample Preparation and Lysis:

- Using a device like the Easy Stool Extraction Device, homogenize 10-20 mg of stool sample in 1 mL of universal extraction buffer [32]. Alternatively, suspend the stool sample directly in Lysis Buffer.

- Incubate the mixture at 65-70°C for 10-15 minutes. If necessary, add Proteinase K and incubate at 56°C for an additional 10-20 minutes to digest proteins.

- Centrifuge the lysate at >12,000 × g for 2 minutes to pellet insoluble debris.

Nucleic Acid Binding:

- Transfer the clarified supernatant to a new tube or the well of a processing plate.

- Add a predetermined volume of the functionalized magnetic particle suspension (e.g., equivalent to 0.5-1 mg of particles) to the lysate.

- Mix thoroughly by pipetting or vortexing and incubate at room temperature for 5-10 minutes. During this period, nucleic acids bind to the particles' surface.

Magnetic Separation and Washing:

- Engage the magnetic field in the automated system to capture the particle-nucleic acid complex. Discard the supernatant.

- With the magnetic field engaged, wash the particles with 500 μL of Wash Buffer 1. Fully resuspend the pellet to ensure complete removal of contaminants. Discard the flow-through.

- Repeat the wash step with 500 μL of Wash Buffer 2.

- Perform a final quick wash with 100% ethanol or allow a brief air-dry cycle (~2-5 minutes) to evaporate residual ethanol.

Elution:

- Resuspend the washed magnetic particles in 50-100 μL of Elution Buffer.

- Incubate at 65-70°C for 5 minutes to facilitate the release of nucleic acids from the particles.

- Engage the magnetic field once more and transfer the eluate containing the purified nucleic acids to a clean tube.

- The extracted nucleic acids are now ready for downstream applications. Store at -20°C or -80°C for long-term preservation.

Protocol 2: Synthesis of Silica-Coated Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (Fe₃O₄@OA@SiO₂)

This two-step protocol describes the synthesis of core-shell nanoparticles suitable for nucleic acid extraction [29].

I. Reagents

- Ferric chloride hexahydrate (FeCl₃·6H₂O)

- Ferrous chloride tetrahydrate (FeCl₂·4H₂O)

- Sodium hydroxide (NaOH)

- Oleic Acid (OA)

- Absolute Ethanol

- Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS)

- Ammonia solution (NH₃)

- Double-distilled water (ddH₂O)

II. Equipment

- Ultrasonic bath

- Round-bottom flask

- Centrifuge

- Magnetic stirrer

- Drying oven

III. Procedure

- Synthesis of Oleic Acid-Coated Nanoparticles (Fe₃O₄@OA):

- Dissolve 1.03 g of FeCl₃·6H₂O and 0.01 mol of FeCl₂·4H₂O in 40 mL of ddH₂O in a round-bottom flask.

- Sonicate the mixture at 50°C for 20 minutes until the salts are fully dissolved.

- Slowly add 40 mL of 0.8 M NaOH solution dropwise (approximately 1 droplet every 2 seconds) under continuous sonication.

- Continue sonication for 1 hour after complete NaOH addition to form a black precipitate of Fe₃O₄.

- Add 20 mL of oleic acid to the mixture and sonicate for an additional 1 hour to coat the particles.

- Recover the Fe₃O₄@OA nanoparticles by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C. Wash the pellet with absolute ethanol five times to remove unreacted precursors.

- Dry the final product at 50°C for 15 hours.

- Silica Coating via the Stöber Method (Fe₃O₄@OA@SiO₂):

- Disperse 40 mg of the synthesized Fe₃O₄@OA in 16.8 mL of ddH₂O by sonication for 20 minutes.

- To this dispersion, add 64 mL of ethanol, 4 mL of ammonia, and 4 mL of TEOS under continuous ultrasonic vibration.

- Allow the reaction to proceed for 4-6 hours to form the silica shell.

- Recover the Fe₃O₄@OA@SiO₂ nanoparticles by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C. Wash the pellet with absolute ethanol five times.

- Dry the final silica-coated particles at 50°C for 15 hours. The nanoparticles can be stored as a dry powder or suspended in a stable buffer for future use.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Magnetic Particle-Based NA Extraction

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Chaotropic Salts (e.g., Guanidine HCl) | Denature proteins & facilitate NA binding to silica surface by dehydrating the NA backbone. | Critical for efficient binding in silica-based protocols; concentration typically 4-6 M [31]. |

| Functionalized Magnetic Particles (e.g., Fe₃O₄@SiO₂) | Solid-phase substrate for NA binding, washing, and elution. | Core innovation; particle size, coating, and magnetization are key performance factors [27] [28]. |

| Proteinase K | Broad-spectrum serine protease for digesting proteins and nucleases. | Essential for stool samples to degrade proteinaceous inhibitors and release NA from complex matrices [33]. |

| Ethanol-based Wash Buffers | Remove salts, solvents, and other contaminants from the particle-NA complex. | Ensures high purity of final eluate; residual ethanol must be evaporated to prevent inhibition of downstream assays [7]. |

| Low-Ionic-Strength Elution Buffer (e.g., Tris, Water) | Disrupts NA-particle interaction by rehydrating the NA backbone. | Elution at elevated temperature (65-70°C) often increases final yield [33]. |

| Easy Stool Extraction Device | Standardizes collection and initial homogenization of stool samples. | Ensures consistent starting material (e.g., 15 mg stool in 1.5 mL buffer), improving reproducibility [32]. |

The pursuit of efficiency, reproducibility, and minimization of contamination in molecular biology has driven the development of integrated nucleic acid extraction workflows. Traditional methods involving multiple tube transfers and manual handling pose significant risks of sample loss, cross-contamination, and procedural variability. This is particularly relevant for complex sample matrices like stool, which contain numerous PCR inhibitors that can compromise downstream applications [12]. Single-tube protocols address these challenges by consolidating lysis, purification, and often elution into a single reaction vessel, offering substantial improvements in workflow efficiency and data reliability for researchers and drug development professionals working with automated nucleic acid extraction from stool samples.

This application note details several established and emerging single-tube methodologies, providing quantitative performance comparisons and detailed experimental protocols to facilitate their implementation in automated stool sample processing.

Single-Tube Methodologies and Performance Data

Different technological approaches have been successfully employed to create integrated nucleic acid extraction workflows. The table below summarizes the core characteristics and performance metrics of several key methods.

Table 1: Comparison of Single-Tube Nucleic Acid Extraction Methods

| Method Name | Core Technology | Sample Types Demonstrated | Processing Time | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PurAmp | Chaotropic lysis with sequential dilution | Single mouse embryos, blastomeres | Rapid (specific time not given) | Sensitive to single molecules; quantitative DNA/RNA recovery | [34] |

| SHIFT-SP | Magnetic silica beads with tip-based mixing | Mycobacterium smegmatis DNA, whole blood | 6–7 minutes | ~96% binding efficiency; nearly complete NA elution | [16] |

| AOM Tubes | Aluminum oxide membrane filtration | Herpes Simplex Virus in CSF | ~15-20 minutes (incl. vacuum steps) | 100% concordance with reference method | [35] |

| HTP Centrifugal Microfluidic | Centrifugal microfluidics with silica-based purification | Clinical samples (10 simultaneously) | < 20 minutes for 10 samples | High-quality RNA for downstream RT-PCR | [36] |

These methods showcase a trend toward miniaturization, automation, and significantly reduced processing times, all while maintaining or improving the yield and purity of extracted nucleic acids compared to multi-step protocols.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The PurAmp Single-Tube Protocol for Sensitive Applications

The PurAmp method is designed for maximum recovery in minute samples, eliminating purification steps through volumetric dilution of chaotropes [34].

Materials:

- Lysis Buffer: 5 M Guanidine Isothiocyanate (GITC)

- Enzymes: Proteinase K (optional for DNA-only extraction)

- Equipment: Thermal cycler with real-time PCR detection

Procedure:

- Lysis: Transfer a single cell or small tissue sample (e.g., a mouse embryo) into a thin-walled PCR tube containing 5-10 µL of GITC lysis buffer.

- Incubation: Incubate the tube at room temperature for 5 minutes to ensure complete lysis and protein denaturation. The sample can be stored dry at this stage if needed.

- Neutralization and RT-PCR: Directly add the complete RT-PCR master mix to the same tube. The master mix volume must be sufficient to dilute the GITC concentration to a level that does not inhibit enzymatic activity (typically a >20-fold dilution).

- Amplification: Perform reverse transcription followed by real-time PCR in the same tube without any transfer steps.

Critical Considerations: This protocol is highly dependent on the initial sample-to-lysis buffer volume ratio and the subsequent dilution factor. The high dilution factor required can be a limitation for some downstream applications.

The SHIFT-SP High-Yield Magnetic Bead Protocol

This protocol optimizes binding and elution for rapid, high-efficiency extraction using magnetic silica beads [16].

Materials:

- Lysis/Binding Buffer (LBB): Guanidine hydrochloride, Triton X-100, pH adjusted to 4.1

- Magnetic Silica Beads

- Wash Buffers: 100 mmol/L NaCl solution

- Elution Buffer: 1X TE Buffer or nuclease-free water

- Equipment: Magnetic stand, pipettes

Procedure:

- Lysis and Binding:

- Combine the sample (e.g., 100 µL of bacterial culture lysate) with an equal volume of LBB (pH 4.1) in a tube.

- Add 30-50 µL of magnetic silica bead suspension.

- Perform "tip-based" binding: Repeatedly aspirate and dispense the mixture with a pipette for 1-2 minutes at 62°C. This ensures rapid and efficient exposure of nucleic acids to the beads.

- Bead Capture: Place the tube on a magnetic stand until the solution clears. Carefully remove and discard the supernatant.

- Washing:

- With the tube on the magnetic stand, add 200 µL of 100 mmol/L NaCl wash buffer. Disperse the beads by flicking the tube or brief vortexing.

- Capture the beads and discard the supernatant.

- Repeat the wash once with 200 µL of nuclease-free water.

- Elution: Remove the tube from the magnetic stand. Add 20-50 µL of Elution Buffer and resuspend the beads. Incubate at 70°C for 1 minute to facilitate high-yield elution. Capture the beads and transfer the eluate containing purified nucleic acids to a new tube.

Automated Single-Tube Workflow for Stool Samples

For complex matrices like stool, commercial automated systems offer robust, integrated solutions [12].

Materials:

- Kit: EZ2 PowerFecal Pro DNA/RNA Kit (QIAGEN)

- Equipment: EZ2 Connect instrument

- Reagents: Phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol, Inhibitor Removal Technology (IRT) buffer

Procedure:

- Lysis and Homogenization: Weigh 50-100 mg of stool and place it in a tube prefilled with lysis buffer and beads. Securely close the tube and homogenize using a vortex adapter or a benchtop homogenizer like the Tissuelyser III.

- Inhibitor Removal: Centrifuge the lysate briefly. Transfer the supernatant to a new tube and add phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol. Vortex and centrifuge to separate phases. The proprietary IRT chemistry in the buffer further removes PCR inhibitors.

- Automated Processing: Transfer the aqueous upper phase to a pre-filled cartridge and load it onto the EZ2 Connect instrument.

- Hands-Off Extraction: Select the desired protocol (DNA-only, RNA-only, or Total Nucleic Acids). The instrument automatically performs all subsequent steps, including optional DNase/RNase digestion, binding, washing, and elution, in a closed system.

- Recovery: Retrieve the eluate containing high-purity nucleic acids from the instrument, ready for downstream applications.

Workflow Integration and Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and decision points in a generalized, automated single-tube workflow suitable for nucleic acid extraction from stool samples.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of single-tube protocols relies on specific reagents and tools designed for integrated workflows.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Tube Workflows

| Reagent/Tool | Function in Workflow | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Chaotropic Salts (e.g., GITC, Guanidine HCl) | Denature proteins and nucleases; facilitate binding of nucleic acids to silica surfaces. | Cell lysis and nuclease inactivation in the initial phase (PurAmp, SHIFT-SP) [34] [16]. |

| Silica-Magnetic Beads | Solid-phase matrix for nucleic acid binding; enables separation via a magnetic field without centrifugation. | Automated nucleic acid capture and washing in platforms like the KingFisher (MagMAX kits) and EZ2 Connect [12] [21]. |

| Inhibitor Removal Technology (IRT) Buffers | Proprietary chemistries designed to adsorb and remove specific PCR inhibitors from complex samples. | Critical for obtaining amplifiable DNA/RNA from inhibitor-rich stool samples [12]. |

| Alternative Matrices (e.g., Aluminum Oxide Membrane - AOM) | Porous filter that captures nucleic acids under vacuum or pressure, integrated into a PCR-tube format. | Single-tube extraction, amplification, and detection of viral pathogens from CSF [35]. |

| Pre-filled Reagent Cartridges | Ensure reagent consistency, reduce pipetting errors, and streamline the setup of automated systems. | Used in automated platforms like the EZ2 Connect for processing stool samples with the PowerFecal Pro kit [12]. |

Integrated single-tube protocols represent a significant advancement in nucleic acid extraction technology. By consolidating lysis, purification, and elution into a single vessel or a fully automated workflow, these methods enhance throughput, improve reproducibility, and minimize the risk of contamination. For research and drug development programs focused on the microbiome and other stool-based analyses, adopting these streamlined workflows is crucial for generating robust, reliable, and high-quality molecular data.