Assessing Diagnostic Concordance: Real-Time PCR Versus Microscopy for Dientamoeba fragilis Detection

This article provides a comprehensive assessment of the concordance between real-time PCR (qPCR) and traditional microscopy for detecting Dientamoeba fragilis, a significant protozoan enteropathogen.

Assessing Diagnostic Concordance: Real-Time PCR Versus Microscopy for Dientamoeba fragilis Detection

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive assessment of the concordance between real-time PCR (qPCR) and traditional microscopy for detecting Dientamoeba fragilis, a significant protozoan enteropathogen. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes current evidence on the superior sensitivity and specificity of qPCR, explores methodological considerations for assay application, addresses troubleshooting for diagnostic accuracy, and validates findings through comparative studies. The synthesis underscores qPCR as the emerging gold standard, with implications for improving clinical diagnostics, epidemiological studies, and therapeutic monitoring.

Dientamoeba fragilis as a Pathogen and the Imperative for Accurate Diagnosis

Clinical Significance and Global Prevalence of D. fragilis Infections

Dientamoeba fragilis is a single-celled protozoan parasite that inhabits the human gastrointestinal tract. Despite its discovery over a century ago, its role as a human pathogen has long been a subject of scientific debate [1]. Classified phylogenetically within the trichomonads rather than amoebae, this organism exhibits a global distribution, with prevalence rates varying dramatically based on geographic location, study population, and, most importantly, the diagnostic methods employed [1] [2]. The central thesis of this guide is that a true understanding of the clinical significance and global epidemiology of D. fragilis is wholly dependent on the diagnostic methodology, specifically the concordance between traditional light microscopy (LM) and modern real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) techniques. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methods and summarizes the current evidence regarding pathogenicity, treatment, and global prevalence for researchers and drug development professionals.

Global Prevalence and Risk Factors

The reported prevalence of D. fragilis is highly heterogeneous, a phenomenon largely attributable to diagnostic sensitivity. Molecular methods like RT-PCR consistently uncover higher infection rates, often establishing D. fragilis as the most common pathogenic protozoan in stool samples when such techniques are applied [3] [2].

The table below summarizes key prevalence data and associated risk factors from recent studies:

Table 1: Global Prevalence and Risk Factors for D. fragilis Infection

| Region/Country | Reported Prevalence | Influencing Factors & Risk Groups | Primary Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global (General) | 0.5% - 71% [3] [4] | Higher in developed countries; use of RT-PCR vs. microscopy [2] [4]. | Various |

| Spain | 0.4% - 24% (children); 2% - 9% (adults) [5] | General population data. | [5] |

| Turkey (UC Patients) | 10.9% (all genotype 1) [6] | Adult ulcerative colitis patient cohort. | [6] |

| Travel-Associated | High Risk Scores for Africa (41.3), Asia & Oceania (17.9), Americas (11.5) [7] | International travel to (sub)tropical regions [7] [4]. | [7] |

| Demographic Risks | High in young children and their primary caregivers [4] | Contact with children; residence in rural areas; co-infection with Enterobius vermicularis (pinworm) [1] [4]. | [1] [4] |

The Pathogenicity Debate: The Critical Role of Parasite Load

The question of whether D. fragilis causes disease has been a long-standing controversy, with studies reporting both symptomatic and asymptomatic infections. Recent research has identified parasite load as a critical factor resolving this debate.

A seminal 2025 prospective case-control study matched symptomatic individuals with asymptomatic household controls, both infected with D. fragilis. The study found a stark contrast in parasite load: only 3.1% of symptomatic cases had a load of less than 1 trophozoite per field, compared to 47.7% of asymptomatic controls. The study concluded that a higher parasite load is strongly associated with the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms, thereby supporting its pathogenicity [5].

Table 2: Clinical Spectrum and Supporting Evidence for D. fragilis Pathogenicity

| Clinical Aspect | Description | Evidence and Citations |

|---|---|---|

| Asymptomatic Carriage | Common; does not require treatment. | Recognized by CDC and multiple studies [8] [1]. |

| Symptomatic Infection | Abdominal pain, diarrhea, loose stools, anal itching, nausea, abdominal distension [5] [3]. | Most common clinical presentation prompting medical consultation. |

| Chronicity | Symptoms can persist for weeks to months. | One study reported 32% of patients had symptoms >2 weeks [3]. |

| Key Support for Pathogenicity | 1. Symptom resolution post-eradication [3].2. Strong association with high parasite load [5].3. Animal model showing infectious dose causes colitis [5]. | [5] [3] |

Diagnostic Methodologies: A Concordance Assessment

The accurate detection of D. fragilis is fundamental to all associated research and clinical decision-making. The diagnostic landscape is primarily divided between traditional microscopic techniques and modern molecular assays, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

Light Microscopy (LM)

- Principle: Direct visualization of trophozoites in stained (e.g., iron-haematoxylin) stool smears [9].

- Workflow: Requires examination of 200-300 oil immersion fields [9].

- Challenges: Trophozoites degrade rapidly after stool passage (hours); requires fresh or appropriately preserved samples [5] [9]. The technique is time-consuming, requires significant expertise, and is less sensitive, leading to underdiagnosis [5] [1].

Real-Time PCR (RT-PCR)

- Principle: Amplification of target DNA sequences (e.g., SSU rRNA gene) specific to D. fragilis [5] [9].

- Advantages: Superior sensitivity and specificity; allows for quantification of parasite load via Cycle Threshold (Ct) values; can be performed on preserved samples [5] [6] [4].

- Considerations: Risk of cross-reactivity with non-target organisms in animal or human samples, which can be mitigated by melt-curve analysis and DNA sequencing [4].

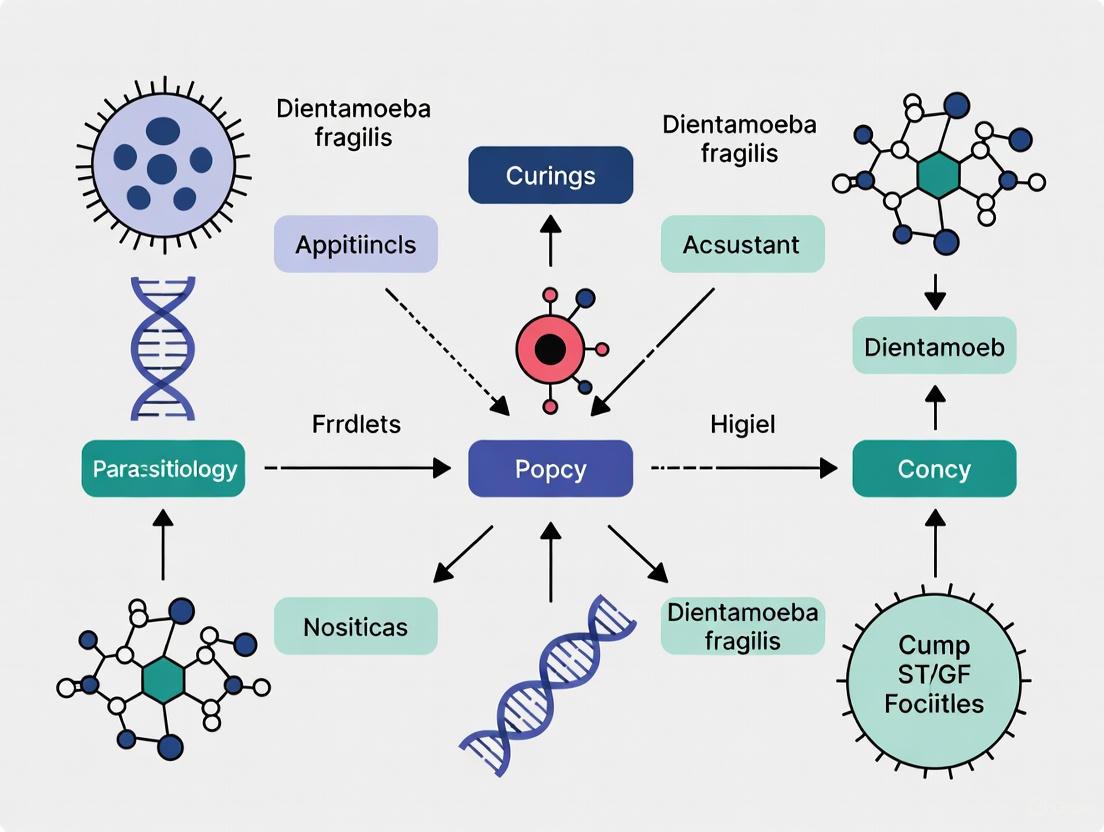

The following diagram illustrates the key steps and decision points in the diagnostic workflow for D. fragilis, highlighting the parallel and complementary nature of LM and RT-PCR.

Treatment Options and Efficacy

Treatment is generally recommended for symptomatic patients when no other cause for symptoms is identified [8] [6]. However, a lack of large-scale, randomized controlled trials means there is no universal consensus on the optimal therapeutic agent.

Table 3: Comparison of Treatment Regimens for D. fragilis

| Drug Class / Agent | Adult Dosage Regimen | Reported Efficacy / Notes | Key Precautions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aminoglycoside | |||

| Paromomycin | 25-35 mg/kg/day, 3 divided doses, 7 days [8]. | Higher cure rates (81.8%) than metronidazole; poorly absorbed [10]. | Pregnancy: Use if benefit > risk; compatible with lactation [8]. |

| Nitroimidazoles | |||

| Metronidazole | 500-750 mg, 3 times daily, 10 days [8]. | Lower efficacy (65.4%); common use but high treatment failure rates [10]. | Avoid alcohol; use in lactation only if benefit justifies risk [8]. |

| Secnidazole/Ornidazole | Single dose regimens described [3]. | Effective with fewer side effects; longer half-lives [10]. | Similar precautions to metronidazole apply. |

| Tetracyclines | |||

| Tetracycline/Doxycycline | 500 mg, twice daily, 10 days [8]. | Historically used [3]. | Pregnancy Category D; not for children <8 years or in lactation (tooth discoloration) [8]. |

| Hydroxyquinolines | |||

| Iodoquinol | 650 mg, 3 times daily, 20 days [8]. | Considered drug of choice by some [10]. | Limited availability in the U.S. [10]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

For researchers designing studies on D. fragilis, selecting the appropriate tools is critical. The following table details key reagents and their applications in experimental protocols.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for D. fragilis Investigation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolate DNA from human or animal faecal material for PCR. | QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen) [4]. |

| Stool Transport Media | Preserve parasite morphology and DNA for different tests. | SAF fixative for microscopy [4]; Cary-Blair for culture/molecular [5]; Formol-Ether for parasites [5]. |

| Commercial Multiplex PCR Kits | Simultaneous detection of multiple gastrointestinal pathogens, including D. fragilis. | EasyScreen Enteric Protozoan Detection Kit (Genetic Signatures) [4]; Allplex GI-Parasite Assay (Seegene) [5]. |

| PCR Reagents | Amplify target DNA sequences for detection and genotyping. | Primers targeting SSU rRNA (e.g., DF400/DF1250) [6]; Taq DNA polymerase, dNTPs [6]. |

| Sequencing Reagents | Confirm pathogen identity and perform genotyping. | Used for Sanger sequencing of PCR amplicons to distinguish genotypes 1 and 2 [6]. |

| Inflammatory Marker Kits | Investigate correlation between infection and gut inflammation. | Fecal Calprotectin (f-CP) kits [5]. |

The body of evidence now strongly supports clinical significance of Dientamoeba fragilis, particularly in individuals with high parasite loads. The global prevalence is substantial, though accurately measuring it is entirely dependent on the use of sensitive molecular diagnostics like RT-PCR. The concordance between LM and RT-PCR is imperfect, with RT-PCR offering significant advantages in sensitivity and the ability to provide quantitative data that is crucial for interpreting clinical significance. Future research, including the development of robust animal models and large-scale randomized controlled trials for treatment, is needed to fully elucidate the transmission dynamics and optimize patient management. For now, the scientific community must acknowledge D. fragilis as an emerging pathogen whose true impact has been uncovered by advances in diagnostic technology.

The parasitology laboratory has long been the frontline for diagnosing gastrointestinal protozoan infections, with microscopic examination of stained fecal specimens historically serving as the reference standard for detecting Dientamoeba fragilis [9]. This fragile trichomonad parasite poses significant diagnostic challenges due to its inability to survive long outside a host and its lack of a known cyst stage in routine clinical practice [11] [12]. While microscopy remains widely used, a growing body of evidence reveals substantial limitations in its specificity and technical reliability for D. fragilis detection [13] [14]. These limitations have prompted researchers to investigate molecular alternatives, particularly real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, which offer potentially superior diagnostic accuracy [4] [11]. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of microscopy against molecular methods within the context of concordance assessment for D. fragilis research, providing experimental data and methodologies to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Performance Comparison: Microscopy Versus Molecular Methods

Multiple studies have systematically compared the diagnostic performance of microscopy against various PCR-based techniques for detecting D. fragilis. The quantitative data reveal consistent patterns of superiority for molecular methods.

Table 1: Comparative Detection Rates of D. fragilis Across Diagnostic Methods

| Study Reference | Microscopy Detection Rate | PCR Detection Rate | Sample Size | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stark et al. (2010) [14] | 34.3% sensitivity | 100% sensitivity (real-time PCR) | 650 samples | Real-time PCR showed perfect sensitivity and specificity |

| El Tokhi et al. (2022) [13] | 13-17% (wet mount/trichrome) | 41% (conventional PCR) | 100 samples | PCR detected over twice as many positive cases as microscopy |

| Calderaro et al. (2010) [11] | 7.2% (69/959 samples) | 19.4% (186/959 samples) | 959 samples | Real-time PCR identified 117 additional positive samples |

| Formenti et al. (2017) [15] | Lower than Rt-PCR | Higher sensitivity for protozoa | Not specified | Molecular biology justified change in laboratory approach |

Table 2: Comprehensive Method Performance Characteristics for D. fragilis Detection

| Diagnostic Method | Sensitivity | Specificity | Technical Challenges | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Mount Microscopy | Very Low [13] | Moderate [13] | Trophozoites degenerate rapidly; nuclear structure not visible [13] [16] | Nearly impossible for definitive identification [16] |

| Trichrome Stain Microscopy | 34.3% [14] | 99% [14] | Requires permanent stains of fixed fecal smears [13] | Remains vital for microscopic diagnosis but less sensitive than PCR [13] |

| Conventional PCR | 42.9-93.5% [13] [9] [14] | 100% [9] [14] | Requires DNA extraction and thermal cycling [13] | More sensitive than microscopy but less than real-time PCR [14] |

| Real-time PCR (qPCR) | 100% [14] [11] | 100% [14] [11] | Potential cross-reactivity with non-target organisms [4] | Gold standard for detection; enables melt curve analysis [4] [14] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Microscopy Techniques

Traditional microscopic diagnosis relies on permanently stained fecal smears, as the characteristic binucleate appearance of D. fragilis cannot be appreciated in saline or iodine preparations [11]. The standard protocol involves immediate fixation of fresh stool specimens to preserve trophozoite morphology, followed by permanent staining using iron hematoxylin or trichrome stains [13]. Microscopists must examine 200-300 oil immersion fields to reliably identify the pleomorphic trophozoites, which range from 4µm to 20µm and display characteristic fragmented chromatin within pale gray-blue finely vacuolated cytoplasm [17]. Success depends heavily on the expertise of the microscopist, with careful differentiation required from non-pathogenic protozoa such as Endolimax nana [9]. Specimen freshness is critical, as trophozoites degenerate rapidly within hours of being passed [9].

Molecular Detection Methods

Molecular protocols for D. fragilis detection typically target the small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) gene or the 5.8S rDNA region [13] [11]. The basic workflow begins with DNA extraction from 150-200mg of fecal sample using commercial kits, followed by amplification with species-specific primers. Conventional PCR protocols often employ primers DF1 and DF4, which amplify a 662-bp fragment of the 18S SSU rRNA gene [13]. Real-time PCR assays provide superior sensitivity and can incorporate melt curve analysis to differentiate D. fragilis from non-target organisms [4]. These assays typically include 35-40 amplification cycles with an annealing temperature of 55-60°C [13] [4]. The entire molecular procedure can be completed within one working day, offering advantages in processing time compared to microscopic methods [9].

Diagram 1: Comparative diagnostic workflows for D. fragilis detection

Technical Challenges and Limitations

Specificity Concerns in Microscopy

Microscopic identification of D. fragilis faces significant specificity challenges due to several factors. The trophozoites are highly pleomorphic, with considerable variation in shape and size, making consistent identification difficult [16]. They can be easily overlooked or misidentified because they are pale-staining and their nuclei may resemble those of Endolimax nana or Entamoeba hartmanni [16]. Additionally, the nuclear structure essential for definitive diagnosis cannot be visualized in either saline or iodine preparations, requiring permanently stained smears for accurate identification [13] [9]. These limitations necessitate highly trained and experienced laboratory personnel to correctly interpret stained smears, with diagnostic accuracy varying considerably between laboratories [13].

Technical and Operational Limitations

The practical implementation of microscopy for D. fragilis detection encounters multiple technical hurdles. The fragile trophozoites disintegrate rapidly after being passed in stool samples, making prompt fixation of clinical specimens essential [16]. This requirement for immediate processing creates logistical challenges for both patients and laboratories. Furthermore, the shedding of D. fragilis may be discontinuous, necessitating examination of multiple fecal samples for maximum detection yield [11]. One study noted that successful microscopic diagnosis is closely associated with utilizing permanent stains of fixed fecal smears, but even with optimal staining techniques, microscopy typically lacks sensitivity compared to molecular methods [13]. The procedure is also time-consuming, with staining processes requiring over an hour plus additional time for microscopic examination by skilled personnel [9].

Molecular Method Considerations

While molecular techniques demonstrate superior performance characteristics, they also present specific technical considerations. Real-time PCR assays may cross-react with non-target organisms, as demonstrated when cattle samples showed a 9°C cooler melt curve than human D. fragilis samples, later identified as cross-reactivity with Simplicimonas sp. [4]. To reduce false-positive results from non-specific amplification, researchers recommend reducing the number of PCR cycles to less than 40 [4]. Additionally, the identification of new animal hosts requires confirmatory evidence from either microscopy or DNA sequencing to validate positive PCR results [4]. The genetic Signatures EasyScreen assay has received FDA 510(k) clearance as the only molecular diagnostic solution for detecting D. fragilis together with seven other gastrointestinal parasites in a single test [16].

Diagram 2: Key challenges in D. fragilis detection by microscopy

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for D. fragilis Detection

| Reagent/Kit | Application | Function | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trichrome Stain | Microscopy | Permanent staining for nuclear structure visualization | Vital for microscopic diagnosis [13] |

| Iron Hematoxylin Stain | Microscopy | Permanent staining alternative to trichrome | Allows visualization of characteristic nuclear structure [9] |

| DNA Stool Mini Kit (Bioline, UK) | Molecular | Genomic DNA extraction from fecal samples | Used in conventional PCR protocols [13] |

| QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen) | Molecular | DNA extraction for real-time PCR | Suitable for human and animal specimens [4] [17] |

| EasyScreen Enteric Protozoan Detection Kit | Molecular | Multiplex real-time PCR detection | FDA 510(k) cleared; detects 8 parasites including D. fragilis [16] |

| DF1/DF4 Primers | Conventional PCR | Amplify 662-bp fragment of 18S SSU rRNA gene | Targets specific region for D. fragilis identification [13] |

| 2X MyTaq Red Mix (Bioline, UK) | Conventional PCR | PCR reaction mixture | Provides necessary enzymes and buffers for amplification [13] |

The accumulated evidence demonstrates that microscopy, while historically important for D. fragilis detection, suffers from significant limitations in both specificity and technical reliability. The inherent biological characteristics of the parasite, including its fragile nature and pleomorphic morphology, combined with operational challenges related to specimen processing and interpreter expertise, fundamentally constrain microscopic methods. Molecular techniques, particularly real-time PCR, address many of these limitations through superior sensitivity, specificity, and operational efficiency. While molecular methods require careful validation to prevent cross-reactivity and false positives, they represent a more reliable approach for both clinical diagnosis and research applications. The concordance assessment between these methodologies clearly supports the transition toward molecular-based detection as the contemporary gold standard for D. fragilis research, particularly when supplemented by sequencing confirmation for novel host species or epidemiological investigations.

For decades, the diagnosis of Dientamoeba fragilis relied exclusively on microscopic examination of stained fecal smears, a method plagued by limitations in sensitivity and specificity. The advent of molecular methods, particularly polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based detection, has revolutionized the identification of this enigmatic intestinal protist. This guide objectively compares the performance of real-time PCR (qPCR) assays against traditional microscopy and evaluates different molecular platforms. Data synthesized from comparative clinical studies reveal that qPCR demonstrates markedly superior sensitivity, detecting 2-3 times more positive samples than conventional methods. However, the transition to molecular diagnostics is not without challenges, as assay choice and implementation significantly impact result reliability. This analysis provides researchers and diagnosticians with a detailed comparison of available methodologies, supported by experimental data and standardized protocols, to inform laboratory practice and advance D. fragilis research.

Performance Comparison: Microscopy vs. Molecular Detection

The evolution of diagnostic techniques for Dientamoeba fragilis has fundamentally altered our understanding of its prevalence and clinical significance. Traditional microscopy, while useful, has proven inadequate as a standalone diagnostic tool, leading to the development and adoption of more sensitive molecular assays.

Limitations of Microscopic Detection

Microscopic identification of D. fragilis in permanently stained fecal smears (e.g., modified iron-haematoxylin or trichrome stain) faces several inherent challenges that compromise diagnostic accuracy [11] [16]:

- Rapid Trophozoite Degeneration: The fragile trophozoites disintegrate quickly after passage, making prompt fixation of specimens critical for morphological preservation [11] [16].

- Pleomorphic Appearance: The highly variable shape and size of trophozoites, combined with their pale-staining characteristics, lead to frequent misidentification as other organisms like Endolimax nana or Entamoeba hartmanni [16].

- Low Sensitivity: Microscopy detects only the trophozoite stage, which is shed discontinuously, and concentration methods typically destroy this fragile stage [11].

Superior Sensitivity of Molecular Methods

Multiple comparative studies have consistently demonstrated the superior sensitivity of PCR-based methods over conventional microscopy and culture. The following table synthesizes key findings from published clinical evaluations:

Table 1: Comparative Sensitivity of Detection Methods for Dientamoeba fragilis

| Study | Microscopy | Culture | Conventional PCR | Real-time PCR | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stark et al. (2010) [14] | 12/650 (1.8%) | 14/650 (2.2%) | 15/650 (2.3%) | 35/650 (5.4%) | 650 human samples |

| Calderaro et al. (2010) [11] | 11/959 (1.1%) | 61/959 (6.4%) | N/R | 186/959 (19.4%) | 959 samples from 491 patients |

| Trop Parasitol (2022) [18] | 17/100 (17.0%)* | N/R | 41/100 (41.0%) | N/R | 100 human samples |

| Jirků et al. (2022) [19] | N/R | N/R | 22/296 (7.4%) | 71/296 (24.0%) | 296 human samples |

Combined result from wet mount and trichrome stain; N/R = Not Reported

The data unequivocally demonstrate that real-time PCR identifies substantially more D. fragilis infections than conventional methods. In the study by Stark et al., real-time PCR detected approximately three times as many positive samples as microscopy and culture [14]. Similarly, Calderaro et al. reported that real-time PCR revealed 117 additional positive samples compared to conventional methods, confirming its value in obtaining accurate epidemiological data [11].

Comparative Analysis of Real-Time PCR Assays

While real-time PCR has established itself as the most sensitive detection method, not all qPCR assays perform equally. Significant differences exist between commercially available kits and laboratory-developed tests, impacting diagnostic reliability.

Performance Discrepancies Between Assay Types

A 2019 comparative study by Gough et al. highlighted critical performance variations between two predominant qPCR approaches [20]. When screening 250 fecal samples, the commercially available EasyScreen assay (Genetic Signatures) detected 24 positive samples, while a widely used laboratory-developed real-time assay identified an additional 34 samples. Further investigation revealed that many of these additional positives were false positives resulting from non-specific amplification [20].

This discrepancy has profound implications for prevalence studies. Regions in Europe using the laboratory-developed assay report significantly higher infection rates than those using the EasyScreen assay, suggesting that previously reported geographical variations may reflect methodological differences rather than true epidemiological patterns [20].

Cross-Reactivity Challenges in Animal Host Studies

The application of human-optimized qPCR assays to veterinary specimens presents unique challenges, as highlighted in a 2025 study by Hall et al. [21] [4]. When screening cattle specimens, researchers observed a 9°C cooler melt curve temperature compared to human-derived D. fragilis amplicons. Subsequent DNA sequencing identified Simplicimonas sp. as the source of this cross-reactivity [21] [4].

This finding has ramifications for our understanding of D. fragilis host species distribution. Several previously reported animal hosts identified solely by qPCR, including cats, dogs, and cattle, require reevaluation with confirmatory testing [21] [4]. The 2025 study concluded that melt curve analysis provides a valuable tool for differentiating true D. fragilis detection from cross-reactions with non-target organisms [4].

Table 2: Key Recommendations for Reliable qPCR Detection of D. fragilis

| Recommendation | Rationale | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Incorporate melt curve analysis | Identifies cross-reactivity with non-target organisms | Analyze melt temperature (EasyScreen assay: expected 63-64°C) [4] |

| Limit PCR cycles | Reduces false positives from non-specific amplification | Use <40 cycles [21] |

| Confirm novel host species | Prevents misidentification due to cross-reactivity | Use sequencing or microscopy alongside qPCR [21] [4] |

| Standardize detection assays | Enables valid geographical and temporal comparisons | Use commercially validated assays like EasyScreen [20] |

Experimental Protocols for Molecular Detection

To ensure reproducible and reliable results, researchers must adhere to standardized methodologies for specimen processing, nucleic acid extraction, and amplification.

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

Proper specimen handling begins immediately after collection to preserve nucleic acid integrity:

- Human Clinical Specimens: Collect fresh fecal samples without preservatives for molecular testing. For parallel microscopy, preserve a portion in SAF fixative [4].

- Animal Specimens: Collect fecal samples from the ground of pens/cages during routine cleaning. Split samples for microscopy (SAF fixative) and molecular analysis (no preservative) [4].

- DNA Extraction: Use commercially available kits such as the QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen). Incorporate an extraction control (e.g., Meridian Bioscience qPCR Extraction Control Kit) to monitor inhibition and extraction efficiency. Modify protocol to include heating stool suspension in InhibitEX buffer for 10 minutes [4].

Real-Time PCR Amplification Protocols

Two well-documented qPCR approaches for D. fragilis detection include:

EasyScreen Assay (Genetic Signatures)

- Multiplex PCR detecting D. fragilis and other gastrointestinal parasites

- Includes extraction control and internal positive control for PCR inhibition

- Amplification followed by melt curve analysis: ramp temperature from 40°C to 80°C in 1°C increments

- Expected melt temperature for D. fragilis: 63-64°C [4]

Laboratory-Based qPCR Protocol

- Targets the 5.8S rDNA gene of D. fragilis [11]

- Reaction mixture: 12.5μL of 2× QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen), 0.5μM of each primer, 5μL of DNA template, and PCR-grade water to 25μL

- Cycling conditions: 95°C for 15 minutes; 40-45 cycles of 94°C for 15 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 30 seconds [11] [20]

- Include negative and positive controls in each run

Confirmatory Testing for Ambiguous Results

To validate qPCR findings, especially when identifying new animal hosts or when melt curve anomalies occur:

- DNA Sequencing: Perform conventional PCR targeting the small subunit (SSU) rDNA gene followed by Sanger sequencing [21] [4]

- Next-Generation Sequencing: Use NGS amplicon sequencing of qPCR products for higher sensitivity in detecting multiple organisms [21] [4]

- Microscopic Examination: Examine permanently stained smears (e.g., modified iron-haematoxylin) for characteristic binucleate trophozoites [21]

Diagram 1: D. fragilis Detection Workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful detection and characterization of D. fragilis requires specific laboratory reagents and kits. The following table details essential materials for establishing a robust diagnostic or research protocol.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for D. fragilis Detection

| Reagent/Kits | Specific Function | Examples/Manufacturers |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolation of inhibitor-free DNA from stool samples | QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen) [4] |

| Real-time PCR Master Mix | Fluorescence-based amplification and detection | QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen) [11] |

| Commercial PCR Assays | Multiplex detection of gastrointestinal pathogens | EasyScreen Enteric Protozoan Detection Kit (Genetic Signatures) [20] [4] |

| Extraction Control Kits | Monitoring inhibition and extraction efficiency | qPCR Extraction Control Kit (Meridian Bioscience) [4] |

| Stool Fixatives | Preservation of morphology for parallel microscopy | SAF fixative (Thermo Fisher) [4] |

| Staining Reagents | Microscopic visualization of trophozoites | Modified iron-haematoxylin, Trichrome stain [14] [18] |

| Sequencing Kits | Confirmatory testing and genotyping | SSU rDNA amplification and sequencing reagents [21] [22] |

The advent of PCR-based detection methods has fundamentally transformed the diagnosis and epidemiological study of Dientamoeba fragilis. The evidence clearly demonstrates that real-time PCR assays offer significantly enhanced sensitivity compared to traditional microscopy, with some studies detecting over three times as many positive samples [11] [14]. This improved detection capability has revealed previously underestimated prevalence rates and expanded our understanding of the parasite's distribution.

However, the implementation of molecular methods requires careful consideration of assay validation and potential pitfalls. Researchers must remain vigilant about cross-reactivity with non-target organisms, particularly when investigating potential animal hosts [21] [4]. The comparison between commercial and laboratory-developed assays highlights the importance of standardization in molecular diagnostics to ensure result reliability and enable valid epidemiological comparisons [20].

For optimal detection, laboratories should implement a structured approach incorporating melt curve analysis, cycle threshold limitations, and confirmatory sequencing when indicated. As research continues to elucidate the clinical significance and transmission dynamics of D. fragilis, standardized molecular methods will prove essential for generating comparable data across studies and populations.

Implementing Real-Time PCR Assays for Robust D. fragilis Detection

Dientamoeba fragilis is a globally prevalent intestinal protozoan whose clinical significance continues to be evaluated [23]. Accurate detection is fundamental to epidemiological surveillance and clinical diagnosis, with molecular methods increasingly supplementing or replacing traditional microscopic examination [24]. This guide focuses on the Small Subunit Ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) gene, a conserved and multi-copy genetic target that has become the cornerstone for PCR-based detection and genotyping of D. fragilis [25] [26]. We objectively compare the performance of key primer sets targeting this region against traditional microscopy, providing experimental data and detailed methodologies to support concordance assessment in research settings.

The SSU rRNA Gene as a Primary Molecular Target

The SSU rRNA gene is a preferred genetic marker for D. fragilis detection and characterization for several reasons. Its multi-copy nature within the genome enhances the analytical sensitivity of PCR assays, allowing for the detection of the parasite even at low infection intensities [25]. Furthermore, the gene contains a mixture of highly conserved and variable regions, enabling the design of primers that are both species-specific and capable of discriminating between the two recognized genotypes of D. fragilis [25] [23] [26].

Early molecular studies relied on culturing the parasite, a cumbersome process that limited large-scale genetic surveys [25]. The development of methods to isolate and amplify D. fragilis DNA directly from stool specimens represented a significant advancement, facilitating more extensive genetic studies and revealing that the parasite exhibits remarkably little sequence variation in its SSU rRNA gene [25]. Subsequent research across diverse geographical populations has consistently identified Genotype 1 as the predominant strain in human infections, with Genotype 2 rarely reported [23] [26].

Table 1: Key Primer Sets Targeting the SSU rRNA Gene for D. fragilis Detection

| Primer Pair Name | Target Region (positions on SSU rRNA) | Amplicon Size | Primary Application | Key Features & Evidence of Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DF1/DF4 [25] | Positions 100 to 761 | ~662 bp | Single-round PCR for direct detection from stool, RFLP genotyping | Designed for high specificity; contains RsaI and DdeI restriction sites for RFLP to distinguish genotypes [25] [23]. |

| DF1/DF4 (Application) [23] [26] | Positions 100 to 761 | ~662 bp | Prevalence studies and genotyping | Widely adopted in global prevalence studies; repeated surveys using these primers find almost exclusively Genotype 1 [23] [26]. |

| 5-Plex qPCR-HRM Assay [27] | Not specified (SSU rRNA) | 114 bp | Multiplex detection & differentiation of 5 gastrointestinal parasites | Used in a High-Resolution Melt (HRM) curve analysis; melting temperature (Tm) for D. fragilis is 71.50 ± 0.00 °C [27]. |

| Johnson & Clark Primers [25] | Full-length SSU rRNA | ~1.7 kbp | PCR of cultured isolates | An early method; found to be inefficient and non-specific for direct detection from stool samples, producing nonspecific bands [25]. |

Comparative Performance: SSU rRNA PCR vs. Microscopy

The transition from microscopy to molecular methods represents a significant shift in diagnostic parasitology. Microscopy, while cost-effective and capable of detecting a broad range of parasites, is limited by low sensitivity, high dependence on operator skill, and the inability to differentiate D. fragilis from other commensals based on morphology alone [24]. Molecular techniques, particularly PCR, offer superior sensitivity and specificity.

Analytical Sensitivity and Specificity

PCR protocols targeting the SSU rRNA gene have demonstrated high analytical sensitivity. The DF1/DF4 primer set was successfully used to analyze D. fragilis from 93 patients and 6 asymptomatic carriers directly from stool samples [25]. Furthermore, a novel 5-plex qPCR-HRM assay demonstrated a low limit of detection (LOD), capable of detecting as few as 10 copies/µl for D. fragilis [27].

A critical aspect of specificity is the accurate discrimination of D. fragilis from other organisms. The DF1/DF4 primers were explicitly designed with several consecutive nucleotides at their 3' ends that match only the D. fragilis sequence, and testing showed no cross-reactivity with the closely related Trichomonas vaginalis [25]. However, researchers must be cautious, as some commercial qPCR assays have shown cross-reactivity with non-target organisms. One study identified Simplicimonas sp. as the cause of a cross-reaction in cattle specimens, which was detectable through a distinct 9°C cooler melt curve [4].

Concordance Assessment and Clinical Correlation

Studies that directly compare microscopy and PCR consistently show that PCR detects a higher number of positive samples [5] [24]. This discrepancy is often attributed to the low parasite load in some infections, which falls below the detection threshold of microscopy.

The clinical relevance of PCR results is underscored by studies investigating parasite load. A 2025 prospective case-control study found a strong correlation between high parasite load, as measured by microscopy (trophozoites per field) and PCR (cycle threshold values), and the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms [5]. The study reported that 47.7% of asymptomatic individuals had a parasite load of <1 trophozoite per field, compared to only 3.1% of symptomatic cases, supporting the hypothesis that parasite burden is a key marker of pathogenicity [5].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of SSU rRNA PCR and Microscopy for D. fragilis

| Performance Characteristic | SSU rRNA PCR (e.g., DF1/DF4) | Traditional Light Microscopy | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | High | Low to Moderate | PCR detected more infections in comparative studies; is essential for low-load infections [5] [24]. |

| Specificity | High (with sequence verification) | Moderate (requires expert morphologist) | Primer DF1/DF4 designed for specificity [25]; cross-reactivity possible with other assays [4]. |

| Genotyping Capability | Yes (via sequencing or RFLP) | No | RFLP with DdeI or RsaI on DF1/DF4 amplicon; sequencing confirms Genotype 1 predominance [25] [23] [26]. |

| Quantification Potential | Yes (via qPCR Ct values) | Semi-quantitative (trophozoites/field) | qPCR Ct values and trophozoite count correlate with symptoms [5]. |

| Throughput & Automation | High (amenable to automation) | Low (manual, time-consuming) | Multiplex PCR allows simultaneous detection of several pathogens [27]. |

| DNA Extraction Requirement | Required | Not required | Critical step; use of inhibitors like alpha-casein improves PCR from stool [25]. |

Experimental Protocols for Concordance Assessment

To ensure reliable and reproducible results in your research, follow these detailed experimental protocols for assessing concordance between SSU rRNA PCR and microscopy.

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

Protocol for Stool Sample Processing and DNA Extraction

- Sample Collection: Collect fresh stool samples into a sterile container without preservative. For optimal detection, a multi-day collection protocol (e.g., the Triple Feces Test) is recommended to account for variable shedding of the parasite [25]. Immediately freeze the unpreserved sample at -20°C or lower until DNA extraction.

- Homogenization: Thaw the sample and thoroughly homogenize ~200 mg of stool in a buffer containing guanidine thiocyanate and EDTA (e.g., 1 ml of 5.6 M guanidine thiocyanate, 18 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 25 mM Tris-HCl) by vortexing for 1 minute [25].

- DNA Extraction: Use a commercial stool DNA extraction kit (e.g., E.Z.N.A. Stool DNA Kit, QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit, or High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit) according to the manufacturer's instructions for pathogen detection [25] [23] [4]. Incorporate a proteinase K digestion step (e.g., 70°C for 10 minutes) to improve yield. Include a mock extraction control (no feces) and an internal extraction control to monitor for inhibition in each batch [25] [4].

PCR Amplification and Genotyping

Protocol for DF1/DF4 PCR and RFLP Genotyping

- PCR Reaction:

- Primers: Use primers DF1 (5′-CTC ATA ATC TAC TTG GAA CCA ATT-3′) and DF4 (5′-TTA TAG TTT CTC TTA TTA GCC CC-3′) [25] [23].

- Reaction Mix: Prepare a 50 µl mixture containing: 20 µl of extracted DNA, 100 ng of each primer, 500 µM dNTPs, 1x PCR buffer, 3 mM MgCl₂, 5 µl of BSA (5 mg/ml), and 0.2 µl of Taq polymerase. The addition of proteins like BSA or α-casein is critical to relieve PCR inhibition by fecal substances [25].

- Cycling Conditions: Perform 40 cycles with denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 52°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min [25].

- Genotyping by RFLP:

- Digest 8 µl of the PCR product with 10 U of DdeI or RsaI restriction enzymes in a 15 µl final volume for 1 hour at 37°C [25].

- Separate the restriction fragments on a 9% polyacrylamide gel (or high-resolution agarose). Visualize the banding pattern after ethidium bromide staining. The distinct RFLP profiles allow for the differentiation of Genotype 1 and the rarer Genotype 2 [25].

Microscopic Examination

Protocol for Light Microscopy of D. fragilis

- Stool Fixation: Preserve a portion of the fresh stool sample immediately upon passage. Sodium acetate-acetic acid-formalin (SAF) is a suitable fixative for permanent staining and reliable diagnosis of D. fragilis [25].

- Staining and Examination: Prepare permanent stained smears (e.g., chlorazol black or Giemsa) from the fixed specimen [25] [5]. Examine the smears under oil immersion (1000x magnification). D. fragilis trophozoites are typically 5-15 µm in diameter and often display 2 nuclei (in ~80% of organisms), with a characteristic karyosome composed of 4-8 granules [28].

- Quantification: For parasite load estimation, count the number of trophozoites per microscopic field at 400x magnification. This semi-quantitative measure can be correlated with qPCR cycle threshold (Ct) values [5].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for concordance assessment between SSU rRNA PCR and microscopy for D. fragilis detection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful detection and genotyping of D. fragilis rely on a set of key reagents and kits. The following table details essential solutions for your research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for D. fragilis SSU rRNA Research

| Reagent/Kits | Function/Application | Specific Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Stool DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of inhibitor-free DNA from complex stool matrices for sensitive PCR. | E.Z.N.A. Stool DNA Kit [23], QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit [4], High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit [25]. |

| SSU rRNA-Targeted Primers | Specific amplification of D. fragilis DNA for detection and genotyping. | Primer pair DF1 & DF4 [25] [23]. |

| PCR Additives for Inhibition Relief | Neutralize PCR-inhibitory substances co-extracted from stool, improving assay robustness. | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) or α-casein [25]. |

| Restriction Enzymes | Performing RFLP analysis on PCR amplicons to differentiate D. fragilis genotypes. | DdeI, RsaI [25]. |

| Commercial Multiplex PCR Panels | Synchronous detection of D. fragilis and other common gastrointestinal pathogens in a single reaction. | Allplex GI-Parasite Assay [5] [26], EasyScreen Enteric Protozoan Detection Kit [4]. |

| Nucleic Acid Stains | Visualization of DNA in gels post-PCR and RFLP. | Ethidium bromide [25]. |

| Stool Fixatives | Preservation of trophozoite morphology for reliable microscopic diagnosis and parasite load estimation. | Sodium Acetate-Acetic Acid-Formalin (SAF) [25] [5]. |

| Permanent Stains | Staining of fixed smears to visualize nuclear detail of D. fragilis trophozoites for identification. | Chlorazol Black, Giemsa [25] [28]. |

The SSU rRNA gene is the most validated and informative target for the molecular detection of Dientamoeba fragilis. Primer sets like DF1/DF4 provide a specific and reliable tool for both detection and genotyping, outperforming traditional microscopy in sensitivity and functionality. The high degree of genetic conservation, with Genotype 1 dominating globally, simplifies assay design but also underscores the need for techniques like qPCR to elucidate the role of parasite load in clinical presentation.

When assessing concordance between PCR and microscopy, researchers should anticipate and systematically investigate discrepancies, as these often reveal true biological or technical factors such as low parasite loads or the limitations of microscopic sensitivity. The experimental protocols and reagent toolkit outlined herein provide a robust foundation for rigorous research into this common, yet still enigmatic, intestinal parasite.

The accurate detection of Dientamoeba fragilis, a gastrointestinal protozoan, is crucial for both clinical diagnosis and public health research. For decades, microscopic examination of permanently stained stool smears was considered the diagnostic gold standard [9]. However, the advent of molecular methods, particularly real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), has revealed significant limitations of microscopy, including poor sensitivity and reliance on experienced technicians for identifying fragile trophozoites [29] [9]. This guide details a step-by-step protocol for detecting D. fragilis via qPCR and objectively compares its performance with traditional microscopy, providing researchers and scientists with the experimental data necessary for methodological decision-making.

Experimental Protocols

Sample Collection and Preparation

Proper sample collection and handling are critical for successful DNA extraction and amplification, as D. fragilis trophozoites degrade rapidly.

- Sample Type: Collect fresh, unpreserved stool specimens. While specimens fixed in Sodium Acetate-Acetic Acid-Formalin (SAF) are suitable for microscopy, fresh or frozen samples are superior for DNA analysis [9] [25].

- The Triple Feces Test (TFT): For optimal detection, especially given the parasite's intermittent shedding, the TFT is recommended. Patients collect stools on three consecutive days into three tubes: TFT1 (SAF fixed), TFT2 (unpreserved), and TFT3 (SAF fixed) [25]. Microscopic analysis is performed on TFT1 and TFT3, and if positive, the unpreserved TFT2 sample is used for DNA extraction.

- Specialized Preparation for Pinworm Eggs: To investigate the hypothesis of D. fragilis transmission via Enterobius vermicularis (pinworm) eggs, a specific washing and surface-sterilization protocol is used. Eggs detached from clear tape samples are incubated in ethyl acetate, pelleted by centrifugation, and washed in PBS. Eggs from swab samples are treated with a hypochlorite solution (0.5%) for 5 minutes to surface-sterilize them before DNA extraction [30].

DNA Extraction

Robust DNA extraction from stool samples is essential to overcome PCR inhibitors present in fecal constituents.

- Sample Lysis: Resuspend approximately 200 mg of unpreserved stool in a guanidine thiocyanate-based lysis buffer. Vortex thoroughly to homogenize the sample [25]. For the pinworm egg protocol, pellets are treated with G2 buffer and proteinase K at 56°C for 1 hour to lyse the eggs [30].

- Extraction and Purification: Use commercial silica-membrane-based kits for reliable DNA purification. The QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen) is commonly used, with modifications such as heating the stool suspension in InhibitEX buffer to improve yield and reduce inhibitors [4]. Alternatively, the MagAttract DNA Mini M48 kit (Qiagen) can be used in an automated M48 instrument [30].

- Inhibition Control: Incorporate an internal control DNA during extraction to detect the presence of PCR inhibitors in the final DNA eluate, which is critical for validating negative results [4].

Real-Time PCR (qPCR) Amplification

qPCR offers high sensitivity and specificity for detecting D. fragilis DNA. The following duplex assay allows for simultaneous detection of D. fragilis and an internal control.

- Reaction Setup: The table below outlines the components and cycling conditions for a duplex qPCR protocol based on the Roche LightCycler 480 platform [30].

Table 1: Real-Time PCR Reaction Setup and Cycling Conditions

| Component | Volume/Amount | Final Concentration/Note | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roche LightCycler 480 Probes Master | 12.5 µL | - | |

| Primer D. fragilis F/R [31] | 6 pmol each | - | |

| Primer E. vermicularis F/R [30] | 6 pmol each | For pinworm detection | |

| TaqMan Probe, D. fragilis [30] | 5 pmol | Modified probe: LC670-AAGCAATT... | |

| TaqMan Probe, E. vermicularis [30] | 4 pmol | Probe: 6FAM-CCAAgCCAC... | |

| Template DNA | 5 µL | - | |

| Total Volume | 25 µL | - | |

| Cycling Conditions | Temperature | Time | Cycles |

| Initial Denaturation | 95°C | 5 min | 1 |

| Denaturation | 95°C | 5 s | 50 |

| Annealing/Extension | 60°C | 15 s | 50 |

- Primer and Probe Sequences:

- D. fragilis Primers: These can target the 5.8S ribosomal RNA gene or the small subunit (SSU) rRNA gene for highly specific detection [31] [32].

- E. vermicularis Primers: For the duplex assay, novel primers targeting the 5S rRNA gene-IGS region (E.vermicu F: 5′-ACAACACTTgCACgTCTCTTC; E.vermicu R: 5′-TAATTTCTCgTTCCggCTCA) are used [30].

Post-Amplification Analysis

- Cycle Threshold (Ct) Interpretation: A sample is considered positive if amplification occurs at or before a predetermined Ct threshold (e.g., Ct ≤ 40) [30]. Lower Ct values indicate higher amounts of starting DNA.

- Melt Curve Analysis: If using a SYBR Green-based qPCR assay, perform melt curve analysis by ramping the temperature from 40°C to 80°C. A specific melt temperature (e.g., 63-64°C for the EasyScreen assay) confirms the identity of the amplicon and helps differentiate it from non-specific products or cross-reactions with other organisms, such as Simplicimonas sp. [4].

- Genetic Characterization (Optional): For genotyping, the DF1/DF4 PCR amplicon can be subjected to restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis using enzymes like DdeI or RsaI to distinguish the known genetic variants of D. fragilis [25].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for Dientamoeba fragilis detection by qPCR.

Performance Comparison: qPCR vs. Microscopy

Extensive evaluations have demonstrated the superior performance of qPCR compared to traditional microscopy for detecting D. fragilis.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Detection Methods for D. fragilis

| Parameter | Real-Time PCR | Microscopy (Trichrome Stain) | Experimental Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | High | Moderate | 100% sensitivity for qPCR vs. microscopy [32] |

| Specificity | High | Variable (user-dependent) | 100% specificity for qPCR [32] |

| Detection Rate | Significantly Higher | Lower | 41/100 by PCR vs. 17/100 by trichrome stain [29] |

| Objective Result | Yes (Ct value) | Subjective | Relies on technician skill [9] |

| Throughput | High (automation possible) | Low | Can process dozens of samples per run |

| Inhibition Control | Yes (internal control) | No | Critical for validating negative results [31] [4] |

| Additional Info | Detects DNA in surface-sterilized pinworm eggs [30] | Cannot assess vector transmission | Supports transmission hypothesis |

The data clearly show that qPCR is a more robust and reliable technique. A 2022 study found that conventional PCR diagnosed 41 cases of D. fragilis, compared to only 17 detected by trichrome stain, demonstrating the markedly higher detection rate of molecular methods [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Successful detection relies on a suite of specific reagents and kits. The following table details essential solutions for the described protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for D. fragilis DNA Detection

| Research Reagent Solution | Function/Application | Example Product/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| Stool DNA Extraction Kit | Purifies high-quality, inhibitor-free DNA from complex stool matrices. | QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen) [4] |

| qPCR Master Mix | Provides enzymes, dNTPs, and buffer for efficient, specific amplification. | Roche LightCycler 480 Probes Master [30] |

| D. fragilis Primers/Probe | Specifically targets and amplifies a unique D. fragilis gene sequence. | E.g., SSU rRNA gene TaqMan assay [31] [32] |

| PCR Internal Control | Distinguishes true target negatives from PCR inhibition. | qPCR Extraction Control Kit (Meridian Bioscience) [4] |

| Sample Preservation Solution | Preserves parasite morphology for parallel microscopy. | Sodium Acetate-Acetic Acid-Formalin (SAF) [9] [25] |

| Surface-Sterilizing Agent | Distinguishes internal from external DNA in pinworm egg studies. | Hypochlorite Solution (0.5%) [30] |

Critical Considerations and Troubleshooting

- Cross-Reactivity in Animal Samples: When applying human-designed qPCR assays to animal specimens, be aware of potential cross-reactivity. A 2025 study found that an assay cross-reacted with Simplicimonas sp. in cattle samples, which was identifiable by a 9°C cooler melt curve [4]. Confirmation via DNA sequencing is recommended for new host species.

- Inhibition Management: PCR inhibition from fecal constituents is a common challenge. The use of additives like bovine serum albumin (BSA) or α-casein in the PCR mixture can help relieve inhibition [25]. If inhibition is detected via the internal control, diluting the DNA template (e.g., 1:5) often allows for successful amplification [4].

- Assay Selection and Validation: Different qPCR assays can yield discrepant results. The same study noted that one commercial assay (EasyScreen) detected 24 positive human samples, while a laboratory-based assay detected an additional 34 positives, some of which were unsupported false positives [4]. This underscores the need for in-house validation of sensitivity and specificity.

Figure 2: Logical relationship demonstrating how qPCR detection improves Dientamoeba fragilis research and clinical outcomes.

The step-by-step protocol detailed herein—from optimized DNA extraction to specific qPCR amplification—provides a robust framework for the sensitive and specific detection of Dientamoeba fragilis. The concordance assessment unequivocally demonstrates that real-time PCR outperforms traditional microscopy, offering superior sensitivity, objectivity, and the ability to uncover new aspects of the parasite's biology, such as its potential mode of transmission. For researchers and drug development professionals, the adoption of this qPCR protocol is fundamental to generating reliable data that can drive accurate diagnosis, effective treatment strategies, and a deeper understanding of this significant yet neglected gut pathogen.

The accurate detection of the intestinal protozoan parasite, Dientamoeba fragilis, represents a significant challenge in diagnostic parasitology. This parasite has been associated with a range of gastrointestinal symptoms, including abdominal pain, diarrhea, fatigue, and flatulence, though asymptomatic carriage has also been reported [33] [34]. The traditional approach for diagnosing dientamoebiasis has relied on microscopic examination of stained fecal specimens, a method fraught with technical challenges including intermittent parasite shedding, rapid trophozoite disintegration, and dependence on examiner expertise [33] [11]. Within the context of a broader thesis on concordance assessment between diagnostic methodologies, this guide objectively compares the performance of real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays against conventional microscopy for D. fragilis detection. It establishes definitive sensitivity and specificity benchmarks to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in their selection of diagnostic platforms and interpretation of epidemiological data.

Comparative Performance of Detection Methods

Multiple studies have systematically evaluated diagnostic techniques for D. fragilis, consistently demonstrating the superior analytical performance of molecular methods. The table below summarizes the key performance metrics established across multiple studies.

Table 1: Established Sensitivity and Specificity Benchmarks for D. fragilis Detection Methods

| Detection Method | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Sample Size (n) | Reference/Study Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real-time PCR (TaqMan) | 100 | 100 | 46 carriers, 42 controls | Comparison of molecular and microscopical approaches [33] |

| Real-time PCR (SSU rRNA target) | 100 | 100 | 200 fecal samples | Evaluation against conventional PCR and microscopy [35] |

| Real-time PCR | 100 | 100 | 650 clinical samples | Comparison with culture, conventional PCR, and microscopy [14] |

| Real-time PCR | 100 | 100 | 959 samples from 491 patients | Comparison with conventional parasitologic methods [11] |

| Microscopy (wet mount & trichrome stain) | 93 | 100 | 46 carriers, 42 controls | Served as comparator in molecular validation [33] |

| Microscopy (modified iron-haematoxylin) | 34.3 | 99 | 650 clinical samples | One of several methods compared to real-time PCR [14] |

| Conventional PCR (gel-electrophoresis) | 76 | 100 | 46 carriers, 42 controls | Evaluated alongside real-time PCR and microscopy [33] |

| Conventional PCR | 42.9 | 100 | 650 clinical samples | Compared to real-time PCR as the superior standard [14] |

| Xenic Culture (Modified Boeck & Drbohlav's medium) | 40 | 100 | 650 clinical samples | Evaluated as a traditional diagnostic method [14] |

The data reveals a stark performance gap. Real-time PCR consistently achieves perfect sensitivity and specificity (100%) across multiple independent studies and sample sizes [33] [14] [35]. In contrast, traditional microscopy shows highly variable and often markedly lower sensitivity, ranging from 34.3% to 93%, underscoring its limitations as a reliable standalone diagnostic [33] [14]. Conventional PCR, while specific, also demonstrates significantly inferior sensitivity (42.9%-76%) compared to its real-time counterpart [33] [14].

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Workflows

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for concordance assessment, the core experimental protocols from key studies are detailed below.

Real-Time PCR (TaqMan) Assay Protocol

The following protocol is adapted from the highly cited Verweij et al. method that has become a common reference in the field [31] [35].

- DNA Extraction: Genomic DNA is extracted directly from fresh or unpreserved stool specimens (within 24 hours of collection) using commercial kits, such as the QIAamp DNA Stool Minikit (QIAGEN), following the manufacturer's standard protocol [35]. Studies indicate that modified extraction protocols do not significantly improve yield and add unnecessary processing time [35].

- Primer and Probe Design: The assay targets a 98-base pair fragment of the 5.8S ribosomal RNA gene. The specific oligonucleotides used are:

- Forward Primer DF3: 5′-GTTGAATACGTCCCTGCCCTTT-3′

- Reverse Primer DF4: 5′-TGATCCAATGATTTCACCGAGTCA-3′

- Dual-Labeled TaqMan Probe: 5′-FAM-CACACCGCCCGTCGCTCCTACCG-TAMRA-3′ [35]

- Amplification Reaction: The 20 µL reaction mixture contains:

- 2 µL of FastStart reaction mix hybridization probes (Roche)

- 3 mM MgCl₂

- 0.25 µM of each forward and reverse primer

- 0.2 µM of the dual-labeled fluorescent probe

- 2 µL of the extracted DNA template

- Thermal Cycling Conditions: Amplification is performed on a real-time PCR platform (e.g., Roche LightCycler) with the following profile:

- Inhibition Control: An exogenous internal control (e.g., Phocine Herpes Virus, PhHV-1) is spiked into the sample lysis buffer to detect PCR inhibition, ensuring false negatives are identified [15].

Microscopic Examination Protocol

The traditional microscopic method, used as a comparator, typically involves the following workflow [33] [14]:

- Sample Fixation: Stool samples are fixed in sodium acetate-acetic acid-formalin (SAF) or similar fixatives to preserve protozoan morphology.

- Slide Preparation: Fixed samples are concentrated using a formalin-ethyl acetate sedimentation technique (e.g., modified Ritchie's method) to increase detection yield [15].

- Staining: The concentrated sediment is used to prepare smears that are permanently stained. Common staining methods include:

- Examination: Stained smears are systematically examined under oil immersion (1000x magnification) by an experienced microscopist. Identification is based on typical nuclear morphology and cytoplasmic appearance.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the parallel paths of these two primary diagnostic approaches and the point of concordance assessment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The transition to molecular diagnostics relies on a suite of specific reagents and tools. The following table catalogues essential materials for implementing the real-time PCR assay for D. fragilis.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for D. fragilis Real-Time PCR Detection

| Item | Specific Function | Example Product/Note |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Purification of inhibitor-free genomic DNA from complex stool matrices. | QIAamp DNA Stool Minikit (QIAGEN) [35]. |

| Specific Primers & Probe | Amplification and fluorescent detection of the target 5.8S rRNA gene fragment. | DF3/DF4 primers and dual-labeled TaqMan probe [35]. |

| Real-Time PCR Master Mix | Provides enzymes, dNTPs, and buffer optimized for fluorescent probe-based assays. | FastStart DNA Master Hybridization Probes (Roche) [35] or SsoFast Master Mix (Bio-Rad) [15]. |

| Internal Control System | Detects PCR inhibition in individual samples to prevent false-negative results. | Phocine Herpes Virus (PhHV-1) spiked during extraction [15]. |

| Positive Control Plasmid | Standard for assay validation, sensitivity determination, and run calibration. | Plasmid (e.g., pDf18S) containing cloned target SSU rRNA gene [35]. |

Critical Considerations for Assay Selection

When selecting a diagnostic assay, researchers must consider factors beyond raw sensitivity and specificity:

- Commercial vs. Laboratory-Developed Tests: While laboratory-developed tests (LDTs), like the one described above, are widely published, commercial kits such as the Genetic Signatures EasyScreen assay offer standardized workflows. A 2019 comparative study highlighted that the widely used LDT by Verweij et al. showed potential for cross-reactivity with related trichomonads (e.g., Trichomonas foetus) and required careful optimization to avoid false positives on some PCR platforms [34]. The EasyScreen assay demonstrated high specificity and is designed to simultaneously test for other common gastrointestinal pathogens [34].

- Quantitative Potential: The real-time PCR methodology is intrinsically quantitative. One study noted that the protozoan load in stools, as measured by real-time PCR, revealed a near-log-normal distribution pattern, opening avenues for research into the relationship between parasite burden and clinical presentation [33].

- Sample Stability: Real-time PCR offers practical advantages in sample handling. One study confirmed that D. fragilis DNA could be reliably detected in unpreserved fecal samples stored at 4°C for up to 8 weeks, simplifying logistics for sample collection and transport [31].

The establishment of sensitivity and specificity benchmarks through rigorous concordance assessment leaves no doubt: real-time PCR is the undisputed gold standard for the detection of Dientamoeba fragilis in clinical and research settings. Its consistent 100% performance across multiple studies starkly contrasts with the variable and often suboptimal sensitivity of traditional microscopy and conventional PCR. For researchers and drug development professionals, the implications are clear. The choice of diagnostic platform directly impacts the accuracy of prevalence studies, the evaluation of treatment efficacy, and the fundamental understanding of the parasite's epidemiology and pathogenicity. To ensure reliable and comparable results, the adoption of standardized, high-performance molecular assays is not just recommended but essential. Future efforts should focus on the global standardization of these assays and the continued exploration of their quantitative potential to further unravel the clinical significance of D. fragilis infections.

Navigating Diagnostic Dilemmas: Specificity and Result Interpretation

The concordance between advanced molecular techniques and traditional microscopy is a cornerstone of reliable diagnostics in parasitology. Real-time PCR (qPCR) has become a gold standard for detecting fastidious intestinal protists like Dientamoeba fragilis due to its superior sensitivity and specificity over microscopy [35]. However, this precision is challenged by a critical pitfall: cross-reactivity with non-target organisms, which can lead to false-positive results and misrepresent the true host range and epidemiology of pathogens. The discovery that Simplicimonas spp., a genus of commensal parabasalids, can cross-react with qPCR assays designed for D. fragilis and Tritrichomonas foetus provides a compelling case study in diagnostic fallibility [21] [36]. This article objectively compares the performance of qPCR against microscopy and other confirmatory techniques within the context of D. fragilis research, framing the discussion around experimental data and the essential protocols required to ensure diagnostic accuracy. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding and mitigating these cross-reactivities is not merely an academic exercise but a fundamental necessity for producing valid, reproducible data that can inform public health and therapeutic strategies.

Experimental Evidence: Documenting Discrepancies and Cross-Reactions

The implementation of qPCR diagnostics in new host species or sample types has repeatedly uncovered unexpected cross-reactivities, underscoring the need for rigorous validation. The following data, synthesized from recent studies, highlights the scope of this issue.

Table 1: Documented Cross-Reactivity Involving Simplicimonas and Related Organisms

| Target Pathogen | Cross-Reactive Organism | Sample Type | Key Experimental Evidence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dientamoeba fragilis | Simplicimonas sp. | Cattle feces | qPCR positive results showed a 9°C cooler melt curve; SSU rDNA sequencing identified Simplicimonas sp. | [21] |

| Tritrichomonas foetus | Simplicimonas-like organism | Bovine vaginal swabs | FRET-based qPCR produced positive signals; melting profile analysis and sequencing confirmed cross-reactivity. | [36] |

| Dientamoeba fragilis | Trichomonas vaginalis, Tritrichomonas foetus | Human stool (control) | Specificity testing of a TaqMan qPCR assay showed amplification of non-target trichomonad DNA. | [35] |

The data in Table 1 reveals a pattern where the assumption of assay specificity breaks down when applied to new contexts. A study screening cattle for D. fragilis using two different qPCR assays found that all positive signals from cattle specimens exhibited a distinct melt curve compared to human-derived D. fragilis [21]. This critical observation was the first step in identifying a widespread issue. Subsequent SSU rDNA sequencing and next-generation amplicon sequencing confirmed that the amplified DNA belonged to Simplicimonas sp., a commensal protozoan, and not the target pathogen [21]. Similarly, a study investigating bovine vaginitis identified a high percentage of qPCR-positive samples for T. foetus, but melting curve discrepancies prompted further investigation, which again implicated Simplicimonas-like DNA as the source of the false-positive signal [36]. These findings have significant ramifications, suggesting that previous reports of D. fragilis or T. foetus in certain animal hosts based solely on qPCR may require re-evaluation.

The performance divergence between molecular and traditional methods is further illustrated by comparative studies. One study comparing qPCR, conventional PCR (cPCR), and microscopy for D. fragilis detection in human samples found that real-time PCR exhibited 100% sensitivity and specificity after resolution of discrepant results, whereas microscopy was prone to misidentification (e.g., confusing D. fragilis with Endolimax nana) [35]. Another survey of gut-healthy volunteers and their animals reported a D. fragilis prevalence of 24% using qPCR, in contrast to only 7% using conventional PCR followed by sequencing, highlighting the impact of methodological choice on prevalence estimates [19]. These comparisons affirm that while qPCR is the more sensitive tool, its results must be interpreted with caution.

Methodological Deep Dive: Protocols for Detection and Verification

The reliable detection of pathogens and the identification of cross-reactivity rely on a suite of well-established molecular and microscopic protocols. The workflow below outlines the key steps for accurate diagnostics and subsequent verification when cross-reactivity is suspected.

Core Real-Time PCR with Melt Curve Analysis

The initial screening step often involves a SYBR Green or probe-based qPCR assay. The protocol typically targets a variable genetic region, such as the small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) gene [21] [35].

- Primer/Probe Design: Assays are designed to be specific to the target pathogen. For example, a TaqMan assay for D. fragilis uses primers DF3/DF4 and a specific dual-labeled probe [35].

- Reaction Setup: A 20 µL reaction volume containing 2 µL of DNA extract, primers, probe (if applicable), and a master mix like Roche's FastStart DNA Master Hybridization Probes [35].

- Thermocycling: Conditions often include an initial denaturation (95°C for 10 min), followed by 35-45 cycles of denaturation, annealing (58-60°C), and extension [21] [35].

- Melt Curve Analysis: Following amplification, the temperature is gradually increased while fluorescence is continuously monitored. A distinct melt curve temperature, such as the 9°C cooler peak observed for Simplicimonas vs. D. fragilis, is a primary indicator of potential cross-reactivity [21].

Confirmatory Techniques for Resolving Discrepancies

When a melt curve anomaly is detected or results are otherwise suspicious, one or more of the following confirmatory methods are employed:

- Conventional PCR and Sequencing: Amplifying a broader region (e.g., the ITS-1/5.8S/ITS-2 region or SSU rDNA) using conventional PCR, followed by Sanger sequencing of the product. The resulting sequence is compared to databases like GenBank for definitive identification [21] [36] [37].

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): For a more comprehensive view, the qPCR product itself can be subjected to NGS amplicon sequencing. This can identify multiple organisms in a sample and is highly effective for detecting the source of cross-reactivity [21].

- Microscopy: The traditional method of staining fecal or tissue samples (e.g., with a modified iron-hematoxylin stain) and examining for trophozoites under light microscopy remains a valuable, though less sensitive, tool for confirmation. It is crucial for ruling out misidentification of other protozoa [35].

Success in navigating diagnostic cross-reactivity depends on access to specific, high-quality reagents and resources. The following table details key solutions for this field of research.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Parasitology

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality DNA from complex samples like feces. | QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (QIAGEN) is widely used, with unmodified protocols proving effective for human stools [35]. |

| qPCR Master Mixes | Sensitive and specific amplification in real-time PCR. | FastStart DNA Master Hybridization Probes (Roche) used in TaqMan assays [35]. SYBR Green mixes are used for assays incorporating melt curve analysis [21]. |

| Primers & Probes | Target-specific amplification and detection. | Primers targeting SSU rRNA (e.g., DF3/DF4 for D. fragilis) or the ITS region are common. Dual-labeled TaqMan probes (e.g., FAM/TAMRA) provide high specificity [35]. |

| Cloning Vectors | Generation of standard curves for sensitivity determination. | PCR product cloned into a TA vector (e.g., from Invitrogen) and transformed into E. coli DH5α [35]. |

| Sanger Sequencing Services | Definitive identification of PCR amplicons. | Used to confirm the identity of both target and non-target amplification products [21] [36]. |

| NGS Platforms | Deep, multi-species identification in a single sample. | Used for amplicon sequencing to identify all organisms present, crucial for uncovering novel cross-reactive species [21]. |

Discussion and Mitigation Strategies for Robust Diagnostics

The evidence clearly demonstrates that melt curve analysis is a simple yet powerful first-line defense for identifying potential cross-reactivity during qPCR diagnostics [21] [36]. The number of PCR cycles is another critical parameter; reducing cycles to less than 40 can help minimize the risk of false positives arising from non-specific amplification in later cycles [21]. Ultimately, the identification of new animal hosts for a pathogen should not rely on a single molecular method. As emphasized by recent studies, claims of novel host-pathogen relationships require corroborating evidence from either DNA sequencing or microscopy to confirm the presence of the purported pathogen [21].

For researchers, this means adopting a hierarchical diagnostic approach. Initial qPCR screening should be followed by melt curve analysis. Any sample with an atypical melt profile or an unexpected source should be subjected to sequencing of the qPCR product. This workflow transforms a potential false positive into an opportunity for discovery, as it did with Simplicimonas. Furthermore, the finding that different qPCR assays for the same pathogen (D. fragilis) can yield discrepant results in human samples underscores the importance of assay selection and validation [21]. Continuous monitoring and validation of diagnostic assays against a panel of related non-target organisms are essential practices for maintaining diagnostic fidelity in an ever-expanding field of molecular parasitology.

The Critical Role of Melt-Curve Analysis in Verifying Amplicons

The accuracy of molecular diagnostics hinges on the specific detection of targeted genetic sequences. Melt-curve analysis, a post-amplification technique in real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), has emerged as a critical, low-cost tool for verifying amplicon identity and detecting non-specific amplification. Within Dientamoeba fragilis research, this method provides an essential layer of quality control, enabling researchers to reconcile discrepancies between molecular and traditional microscopic detection methods and ensuring the reliability of epidemiological data and host distribution studies.

Principles of Melt-Curve Analysis

Melt-curve analysis monitors the dissociation of double-stranded DNA as temperature increases. The process is based on the fundamental property that DNA melts at a characteristic temperature (Tm) influenced by its GC content, length, and sequence [38]. During the analysis, fluorescent DNA-binding dyes (e.g., SYBR Green I) release diminishing fluorescence as DNA strands separate. This generates a melt curve, from which a derivative plot (-d(Fluorescence)/dT) is used to identify specific Tm values as distinct peaks [38].

Amplicons with divergent sequences exhibit discernible Tm shifts. High-Resolution Melting (HRM) can detect single-base variants, insertions, or deletions, making it a powerful tool for genotyping and variant scanning [38]. This capability is crucial for confirming that a positive amplification signal truly originates from the intended target and not from non-specific products or non-target organisms.

Application in Dientamoeba fragilis Research

Resolving Diagnostic Dilemmas

The detection of Dientamoeba fragilis has been revolutionized by qPCR, but assays developed for human clinical use can produce misleading results when applied to veterinary specimens due to differing gut microbiomes [21] [4]. A 2025 study by Hall et al. exemplifies the critical application of melt-curve analysis in this context.

When screening cattle for D. fragilis, researchers observed that PCR products generated a melt curve with a Tm approximately 9°C cooler than that of true D. fragilis amplicons from human samples [21] [4]. This discrepancy flagged a potential cross-reaction. Subsequent DNA sequencing confirmed that the cattle samples were not D. fragilis, but instead contained Simplicimonas sp., a related protozoan [21] [4]. Without melt-curve analysis, these results could have been misinterpreted as a new animal host for D. fragilis, thereby distorting the understanding of its host species distribution.

Comparing qPCR Assay Performance