Antigen vs. PCR Testing: A Critical Analysis of Diagnostic Sensitivity and Specificity for SARS-CoV-2 and Respiratory Viruses

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of rapid antigen tests (Ag-RDTs) versus polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory viruses.

Antigen vs. PCR Testing: A Critical Analysis of Diagnostic Sensitivity and Specificity for SARS-CoV-2 and Respiratory Viruses

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of rapid antigen tests (Ag-RDTs) versus polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory viruses. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational performance data, methodological applications, and optimization strategies from recent real-world evidence and meta-analyses. The review highlights the significant sensitivity gap, particularly at low viral loads, and explores the implications of test selection on clinical outcomes, public health policy, and antimicrobial stewardship. It further discusses the critical need for robust post-market surveillance and validation frameworks to guide the development and deployment of future diagnostic technologies.

The Fundamental Accuracy Gap: Unpacking Sensitivity and Specificity in Antigen and PCR Tests

Molecular diagnostics play a pivotal role in modern disease control, with the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) established as the gold standard for pathogen detection. Its superior performance is particularly evident when compared to rapid antigen tests (RATs), especially in its ability to identify early, low-level infections through multi-target genetic analysis. This guide examines the experimental data and methodologies that underpin PCR's high sensitivity and specificity, providing a objective comparison for research and development professionals.

Analytical Performance: PCR vs. Rapid Antigen Tests

The core advantage of PCR lies in its direct detection of a pathogen's genetic material, allowing for exceptional sensitivity. Rapid antigen tests, which detect surface proteins, are inherently less sensitive, a disparity that becomes pronounced in low viral load scenarios.

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies.

| Test Type | Average Sensitivity | Average Specificity | Contextual Performance Notes | Source (Virus) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR (qPCR/ddPCR) | ~91.2% - 97.2% (Clinical Sensitivity) [1] [2] | ~91.0% - 100% (Clinical Specificity) [2] | Sensitivity approaches 100% for analytical detection of 500-5000 viral RNA copies/mL [3]. | SARS-CoV-2, Influenza, RSV [1] [2] |

| Rapid Antigen Test (RAT) | 59% - 69.3% (Overall) [4] [5] | 99% - 99.3% [4] [5] | Sensitivity can drop below 30% in patients with low viral loads [1]. | SARS-CoV-2 [4] [5] |

| RAT (Symptomatic) | 73.0% [5] | 99.1% [5] | Highest sensitivity (80.9%) within first week of symptoms [5]. | SARS-CoV-2 [5] |

| RAT (Asymptomatic) | 54.7% [5] | 99.7% [5] | Performance varies significantly by manufacturer [4] [5]. | SARS-CoV-2 [5] |

This significant sensitivity gap has direct clinical consequences. A large meta-analysis found that point-of-care RATs missed nearly a third of SARS-CoV-2 cases (70.6% sensitivity), while molecular point-of-care tests detected over 92% [1]. For influenza, some RATs detect only about half of all cases, performance considered "barely better than a coin toss" [1].

Multi-Target Detection: Enhancing Assay Robustness and Sensitivity

A key strategy for maximizing PCR's reliability is the simultaneous detection of multiple genetic targets. This approach mitigates the risk of false negatives due to mutations or genomic variations in a single region and is now recommended by global health bodies.

Experimental Data on Multi-Target Assays

Research on Yersinia pestis (the plague bacterium) provides a clear example. A 2024 study developed a droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) assay targeting three genes: ypo2088 (chromosomal), and caf1 and pla (plasmid-borne) [6]. This multi-target approach adhered to WHO guidelines, which recommend at least two positive gene targets for confirmed plague cases [6].

The performance of this multi-target assay was systematically evaluated [6]:

- Limits of Detection (LoD): The assay could detect as few as 6.2 to 15.4 copies of the target genes per reaction.

- Sensitivity in Complex Samples: It reliably detected low concentrations of Y. pestis in spiked soil (10² CFU/100 mg) and mouse liver tissue (10³ CFU/20 mg) samples, demonstrating superior sensitivity compared to a qPCR benchmark.

- Quantitative Linearity: The assay showed excellent quantitative performance across a wide range of bacterial concentrations (10³–10⁶ CFU/sample) with a linear correlation (R² = 0.99).

A similar principle applies to SARS-CoV-2 testing. A 2023 evaluation of five commercial RT-PCR kits found that those targeting more genes generally demonstrated better accuracy and fewer false-positive results [2]. For instance, kits targeting three genes (ORF1ab, N, and S or E) showed higher specificity compared to those targeting only one or two genes [2].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Multi-Target ddPCR forY. pestis

The following protocol summarizes the key experimental methodology from the 2024 study on Y. pestis detection, which exemplifies a rigorous approach to multi-target assay development [6].

Assay Design and Components

- Target Selection: Three genes were selected to ensure redundancy: the chromosomal gene ypo2088 and the plasmid-borne virulence genes caf1 (pMT1 plasmid) and pla (pPCP1 plasmid).

- Primers and Probes: TaqMan hydrolysis probes and primers were designed for each target. Probes were labeled with distinct fluorophores (FAM for pla, HEX for caf1 and ypo2088) to allow multiplexing in a single reaction.

- Sample Preparation: Bacterial genomic DNA was extracted from cultured Y. pestis using a commercial DNA Mini kit. For simulated clinical samples, mouse liver tissues or soil samples were spiked with known concentrations of Y. pestis (measured in Colony Forming Units, CFU) before identical DNA extraction.

ddPCR Reaction Setup

- Reaction Mix: The 20 μL multiplex ddPCR reaction included:

- 10 μL of supermix for probes.

- Forward and reverse primers for all three genes (each at 900 nM).

- TaqMan probes at optimized concentrations (pla and caf1 at 250 nM, ypo2088 at 500 nM).

- 2 μL of the extracted DNA template.

- Droplet Generation and PCR: The reaction mixture was combined with 70 μL of droplet generation oil in a QX200 droplet generator to create thousands of nanoliter-sized droplets. The droplets underwent PCR amplification in a thermal cycler with the following protocol:

- Enzyme activation at 95°C for 10 minutes.

- 40 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 94°C for 30 seconds.

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 1 minute.

- Enzyme deactivation at 98°C for 10 minutes.

Data Acquisition and Analysis

- After amplification, droplets were read in a QX200 droplet reader.

- The reader measures the fluorescence in each droplet, classifying it as positive or negative for each target.

- The software uses Poisson statistics to provide an absolute count of the target DNA copies per microliter of the original reaction, without the need for a standard curve.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The table below details essential reagents and their functions based on the protocols cited.

| Research Reagent / Kit | Primary Function in Assay |

|---|---|

| QIAamp DNA Mini Kit [6] | Extraction and purification of genomic DNA from complex samples (e.g., bacterial cultures, tissues, soil). |

| SuperMix for Probes (No dUTP) [6] | A ready-to-use master mix containing DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and optimized buffers for probe-based ddPCR. |

| TaqMan Hydrolysis Probes [6] | Sequence-specific oligonucleotides with a 5' fluorophore and a 3' quencher. Cleavage during PCR generates a fluorescent signal, enabling target detection and quantification. |

| Droplet Generation Oil [6] | An oil formulation used to partition the aqueous PCR reaction into approximately 20,000 nanoliter-sized droplets for digital PCR. |

| Viral Transport Medium (VTM) [4] | A medium used to preserve the viability of viruses and viral RNA in swab samples during transport and storage. |

| CRISPR-CasΦ System [7] | A novel CRISPR-associated protein used in emerging diagnostic platforms for its collateral cleavage activity, enabling amplification-free, ultrasensitive detection. |

Experimental data consistently confirms that PCR, particularly multi-targeted approaches, remains the gold standard for sensitive and specific pathogen detection. Its ability to amplify and detect multiple genetic regions simultaneously provides a robust defense against false negatives caused by pathogen evolution or low viral loads. While rapid antigen tests offer speed and convenience, their significantly lower sensitivity, especially in asymptomatic individuals or during early infection, limits their utility for confirmatory diagnosis. For researchers and clinicians, the choice of diagnostic tool must align with the required performance: PCR for maximum accuracy, and antigen tests for rapid screening where some sensitivity can be traded for speed.

The widespread adoption of Rapid Antigen Tests (Ag-RDTs) for detecting SARS-CoV-2 has represented a crucial public health tool during the COVID-19 pandemic, offering rapid results without specialized laboratory equipment. However, these tests face a fundamental challenge: inherently lower sensitivity compared to molecular methods like polymerase chain reaction (PCR). This performance gap is not random but stems from core technological and biological constraints. Antigen tests detect the presence of viral proteins, which requires a sufficient concentration of these target molecules in the sample to generate a positive signal. In contrast, PCR tests amplify specific sequences of viral genetic material, enabling the detection of even minuscule amounts of the virus that would be undetectable by antigen assays [8].

This article analyzes the mechanistic basis for this sensitivity trade-off, examining how viral load dynamics, test design parameters, and specimen characteristics collectively influence antigen test performance. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these limitations is essential for interpreting test results accurately, developing improved diagnostic platforms, and formulating effective testing strategies that account for the inherent strengths and weaknesses of different methodologies.

Comparative Performance Data: Antigen Tests vs. PCR

Numerous real-world studies and systematic reviews have quantified the performance gap between antigen tests and PCR. The table below summarizes key accuracy metrics from recent research, illustrating how antigen test sensitivity varies significantly across different conditions and patient populations.

Table 1: Diagnostic Accuracy of SARS-CoV-2 Antigen Tests Compared to PCR

| Study Context | Overall Sensitivity | Symptomatic Individuals | Asymptomatic Individuals | Specificity | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cochrane Systematic Review (2023) | 69.3% (95% CI, 66.2-72.3%) | 73.0% (95% CI, 69.3-76.4%) | 54.7% (95% CI, 47.7-61.6%) | 99.3% (95% CI, 99.2-99.3%) | [5] |

| Brazilian Cross-Sectional Study (2025) | 59% (0.56-0.62) | No significant difference by symptom days | Not Reported | 99% (0.98-0.99) | [4] [9] |

| Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis (2021) | 75.0% (95% CI, 71.0-78.0) | Higher than asymptomatic | Lower than symptomatic | High (specific value not stated) | [10] |

| FDA-Authorized Tests Postapproval (2025) | 84.5% (Pooled from postapproval studies) | Not Reported | Not Reported | 99.6% | [11] |

A critical factor explaining this variable performance is the viral load in the patient sample. Antigen test sensitivity demonstrates a strong inverse correlation with PCR cycle threshold (Ct) values, a proxy for viral load. Data from a large Brazilian study vividly illustrates this relationship:

Table 2: Antigen Test Sensitivity as a Function of Viral Load (PCR Cycle Threshold)

| PCR Cycle Threshold (Ct) Range | Viral Load Interpretation | Antigen Test Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|

| Cq < 20 | High Viral Load | 90.85% |

| Cq 20-25 | Moderate to High | 89% |

| Cq 26-28 | Moderate | 66% |

| Cq 29-32 | Low | 34% |

| Cq ≥ 33 | Very Low | 5.59% |

This dependency on viral load is the primary mechanistic reason for antigen tests' lower overall sensitivity. PCR's ability to amplify target DNA allows it to detect infection across all viral load levels, while antigen tests are inherently limited to detecting the period of peak viral replication [1].

The Core Mechanism: Fundamental Limits of Antigen Detection

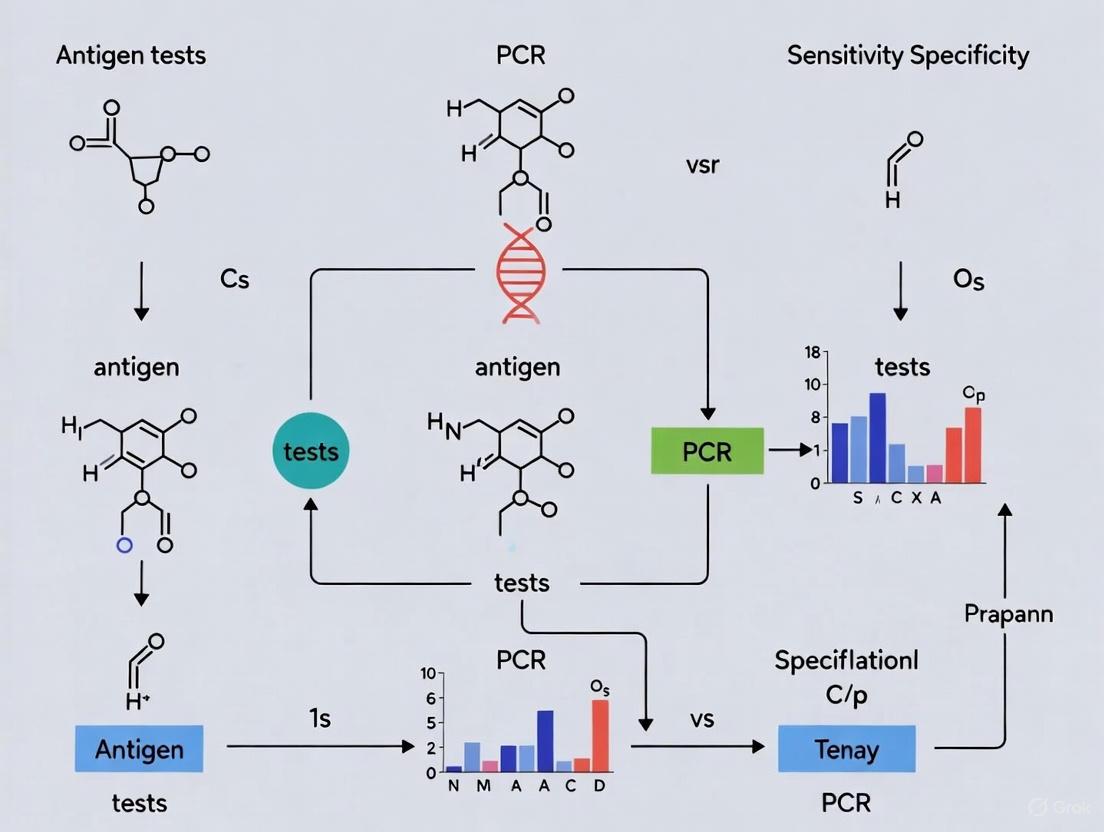

The sensitivity struggle of antigen tests is rooted in their foundational design principle: the direct, non-amplified detection of viral proteins. The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanistic disparity between antigen and PCR testing.

The Antigen Detection Pathway and Its Limitations

As shown in the diagram, the antigen test pathway involves viral lysis to release proteins, followed by antigen-antibody binding that is visualized on a test line. The critical limitation is the absence of signal amplification. The test relies on a sufficient number of antigen molecules being present in the sample to create a visible signal (e.g., a colored line) within the short test timeframe [8]. This detection threshold is typically only crossed during the peak viral load phase of an infection, which generally occurs around the time of symptom onset and lasts for a limited window [10]. If the viral protein concentration falls below the test's detection limit—which occurs during the early incubation period, late convalescent phase, or in some asymptomatic cases—the test will return a false negative result, even if the person is infected [1].

The PCR Amplification Advantage

In contrast, the PCR pathway incorporates a powerful amplification step. After converting viral RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA), the process uses enzymatic replication to create billions of copies of a specific target sequence from the original genetic material [8]. This exponential amplification allows the test to detect a very small initial number of viral RNA molecules—theoretically, even a single copy—by making them visible to fluorescent detection systems. This fundamental difference in methodology is why PCR can identify infections at very low viral loads, including during the early and late stages of infection when antigen tests are likely to fail [1].

Factors Influencing Antigen Test Performance

Biological and Clinical Variables

Beyond the core mechanism, several biological and clinical factors significantly influence antigen test sensitivity by affecting the viral antigen concentration in the sample:

- Time from Symptom Onset: Sensitivity is highest in the first week after symptoms begin (around 80.9%) when viral loads typically peak, and drops significantly in the second week (to approximately 53.8%) as the immune system clears the virus and antigen levels decline [5].

- Patient Age: One quantitative antigen test study found a positive correlation between age and test sensitivity (r=0.764 when excluding teenagers), with Presto-negative samples coming from significantly younger patients (median age 39 years) compared to Presto-positive samples (median age 53 years) [12]. This may be related to differences in viral shedding patterns or immune responses across age groups.

- SARS-CoV-2 Variant: While one study found no association between mutant strains and the results of a quantitative antigen test [12], the potential for mutations to alter antigen protein structures remains a theoretical concern that requires ongoing test evaluation.

Specimen Collection and Test Design Factors

- Sample Type and Quality: Nasopharyngeal samples generally yield higher viral loads compared to anterior nasal or saliva samples. Proper collection technique is crucial to obtaining an adequate sample for testing [10].

- Specimen Storage: Freezing specimens prior to antigen testing can impact test performance, potentially reducing sensitivity by altering antigen integrity or antibody binding affinity [10].

- Test Manufacturer and Design: Significant variability exists between different commercial antigen tests. A Cochrane review found that average sensitivities by brand ranged from 34.3% to 91.3% in symptomatic participants, highlighting the impact of assay design, including the antibodies used and the test's analytical limit of detection (LOD) [5].

Experimental Protocols for Performance Evaluation

To generate the comparative data discussed in this article, researchers have employed rigorous experimental protocols. The following methodology is representative of studies evaluating antigen test accuracy against the gold standard of PCR.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Their Functions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Paired Nasopharyngeal Swabs | Simultaneous sample collection for Ag-RDT and RT-qPCR to enable direct comparison. |

| Viral Transport Medium (VTM) | Preserves virus integrity for transport and subsequent RT-qPCR analysis. |

| Rapid Antigen Test Kits (e.g., TR DPP COVID-19, IBMP TR Covid Ag) | Index test for detecting SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid antigens. |

| Viral RNA Extraction Kit (e.g., Loccus Biotecnologia) | Isolates viral genetic material from VTM for PCR amplification. |

| RT-qPCR Master Mix (e.g., GoTaq Probe 1-Step) | Contains enzymes, probes, and buffers for reverse transcription and DNA amplification. |

| RT-qPCR Instrument (e.g., QuantStudio 5) | Thermal cycler that performs precise temperature cycles for amplification and fluorescence detection. |

Detailed Experimental Methodology

1. Study Population and Sample Collection: Studies typically enroll symptomatic individuals presenting for testing. In the Brazilian study, consecutive individuals aged 12 years or older with symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 were included [4] [9]. Two nasopharyngeal swabs are collected simultaneously from each participant by trained healthcare workers to ensure sample parity.

2. Sample Processing and Testing:

- Antigen Testing: One swab is immediately tested using the rapid antigen test according to the manufacturer's instructions, with results typically available in 15-30 minutes [4] [13].

- PCR Testing: The paired swab is stored in Viral Transport Medium (VTM) at -80°C until RNA extraction can be performed. RNA is extracted using commercial kits, and RT-qPCR is performed using approved protocols (e.g., CDC's 2019-nCoV RT-PCR diagnostic protocol) on platforms such as the QuantStudio 5 [4]. Cycle threshold (Ct) values below 35-40 are generally considered positive for SARS-CoV-2.

3. Data Analysis: Statistical analysis involves calculating sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, and accuracy with 95% confidence intervals. Results are often stratified by variables such as symptom status, days from symptom onset, and PCR Ct values to understand performance across different subpopulations [4] [5].

The following diagram maps this experimental workflow and the key decision points in the comparative analysis.

The inherent sensitivity limitations of antigen tests are a direct consequence of their fundamental detection mechanism, which relies on the presence of viral proteins above a certain threshold without the benefit of amplification. This mechanistic trade-off is not a design flaw but a defined characteristic that dictates their appropriate application.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings have several critical implications. First, diagnostic strategies must account for the predictable performance characteristics of antigen tests, reserving them for scenarios where speed and accessibility are prioritized over ultimate sensitivity, such as rapid screening during the symptomatic phase when viral loads are high. Second, the significant variability in performance between different test brands underscores the necessity of robust post-market surveillance and real-world validation, as manufacturer claims may not always reflect actual performance in clinical practice [11]. Finally, future innovation in rapid diagnostics should focus on novel technologies that can bridge the current performance gap, potentially through integrated isothermal amplification systems or enhanced signal detection methods that can approach PCR-level sensitivity while maintaining the operational advantages of current antigen tests.

The COVID-19 pandemic created an unprecedented global demand for accurate, scalable diagnostic testing. Two primary testing methodologies emerged: antigen-detection rapid diagnostic tests (Ag-RDTs) and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) tests. While manufacturers often claim high sensitivity for rapid antigen tests, systematic reviews frequently report considerably lower performance in real-world settings [14]. This discrepancy between controlled evaluations and clinical performance represents a critical challenge for researchers, clinicians, and public health officials relying on these diagnostics.

This guide objectively compares the performance of antigen tests versus PCR across multiple dimensions, including analytical sensitivity, specificity, and the impact of viral load. By synthesizing evidence from meta-analyses and large-scale real-world studies, we provide researchers and drug development professionals with comprehensive experimental data and methodologies to inform diagnostic selection and development.

Performance Comparison: Antigen Tests vs. PCR

Table 1: Overall Performance Characteristics of Antigen Tests vs. PCR

| Test Type | Sensitivity Range | Specificity Range | Overall Accuracy | Key Factors Influencing Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antigen Tests (Overall) | 59-86.5% | 94-99.6% | 82-92.4% | Viral load, manufacturer, symptom status |

| PCR (Reference) | ~100% | ~100% | ~100% | Sample quality, extraction efficiency |

| Ag-RDT (High Viral Load, Cq <25) | 90-100% | 94-99.6% | N/R | Sample collection timing |

| Ag-RDT (Low Viral Load, Cq ≥30) | 5.6-31.8% | 94-99.6% | N/R | Viral variants, sample type |

N/R: Not Reported

Substantial evidence confirms that rapid antigen tests perform with high sensitivity (90-100%) when viral loads are high, typically corresponding to PCR cycle threshold (Cq) values below 25 [4] [15]. However, this sensitivity decreases significantly as viral load diminishes. A comprehensive Brazilian study with 2,882 symptomatic individuals demonstrated that antigen test sensitivity dropped from 90.85% at Cq <20 to just 5.59% at Cq ≥33 [4] [9].

Performance variations exist between different antigen test formats. Fluorescence immunoassay (FIA) platforms have demonstrated higher sensitivity (73.68%) compared to lateral flow immunoassay (LFIA) formats (65.79%) in asymptomatic patients [15]. Importantly, a systematic review of FDA-authorized tests found that most maintained stable accuracy post-approval, with pooled sensitivity of 86.5% in preapproval studies versus 84.5% in postapproval settings [14] [11].

Impact of Viral Load on Test Performance

Table 2: Antigen Test Sensitivity Across Viral Load Ranges

| PCR Cycle Threshold (Cq) Range | Viral Load Classification | Antigen Test Sensitivity | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| <20 | High | 90-100% | High detection reliability |

| 20-25 | Moderate to High | 89% | Good detection reliability |

| 26-28 | Moderate | 66% | Moderate detection reliability |

| 29-32 | Low | 34% | Poor detection reliability |

| ≥33 | Very Low | 5.6-27.3% | Minimal detection capability |

The inverse relationship between Cq values (indicating viral concentration) and antigen test sensitivity is well-established [4] [15]. One study demonstrated that while both FIA and LFIA antigen tests achieved 100% sensitivity at Cq values <25, their sensitivity reduced to 31.82% and 27.27% respectively at Cq values >30 [15]. This pattern underscores a fundamental limitation of antigen tests: they detect viral proteins, which are less abundant and only reliably detectable during peak infection.

Variant-Specific Performance

Antigen test performance varies across SARS-CoV-2 variants. Research comparing the Alpha, Delta, and Omicron variants found that the diagnostic sensitivity of FIA was 78.85% for Alpha and 72.22% for Delta, while LFIA showed 69.23% for Alpha and 83.33% for Delta [15]. Notably, both Ag-RDT formats achieved 100% sensitivity for detecting the Omicron variant, suggesting potentially enhanced performance against this variant [15].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Evaluation Framework

The benchmark testing process for diagnostic assays follows a systematic approach to ensure accurate and comparable results [16]. The methodology involves performance comparison against established standards, repeated measurements to ensure reliability, and validation through statistical analysis.

Real-World Study Designs

Large-scale comparative studies typically employ simultaneous sampling methodologies. For example, in a study of 2,882 symptomatic individuals in Brazil, researchers collected two nasopharyngeal swabs simultaneously from each participant [4] [9]. One swab was analyzed immediately using Ag-RDTs with a 15-minute turnaround time, while the other was stored at -80°C in Viral Transport Medium (VTM) for subsequent RT-qPCR analysis [4]. This paired-sample approach controls for variability in viral load distribution across participants and sampling techniques.

RNA extraction typically employs automated systems such as the Extracta 32 platform using Viral RNA and DNA Kits [4]. PCR confirmation generally follows established protocols like the CDC's real-time RT-PCR diagnostic protocol for SARS-CoV-2, implemented on instruments such as the QuantStudio 5 with GoTaq Probe 1-Step RT-qPCR systems [4] [9].

Advanced Statistical Adjustment Methods

Recent methodological advances address variability in viral load distributions across studies. Bosch et al. (2024) proposed a novel approach that models the probability of positive agreement (PPA) as a function of qRT-PCR cycle thresholds using logistic regression [17]. This method calculates adjusted sensitivity by applying the PPA function to a reference concentration distribution, enabling more uniform sensitivity comparisons across different test products and studies [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Diagnostic Test Evaluation

| Reagent/Equipment | Manufacturer/Example | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viral Transport Medium (VTM) | Various | Preserve specimen integrity during transport and storage | Maintains viral viability and nucleic acid stability |

| Automated Nucleic Acid Extractor | Extracta 32 (Loccus Biotecnologia) | Automated RNA/DNA extraction from clinical samples | Increases processing throughput and standardization |

| Viral RNA and DNA Kit | MVXA-P096FAST (Loccus Biotecnologia) | Nucleic acid purification from clinical samples | Compatible with automated extraction systems |

| RT-qPCR Reagents | GoTaq Probe 1-Step RT-qPCR (Promega) | One-step reverse transcription and quantitative PCR | Reduces handling steps and potential contamination |

| Real-time PCR Instrument | QuantStudio 5 (Applied Biosystems) | Quantitative PCR amplification and detection | Enables precise Ct value determination |

| Nasopharyngeal Swabs | FLOQSwabs (Copan) | Clinical specimen collection | Specialized surface coating improves sample recovery |

Discussion and Research Implications

The discrepancy between meta-analysis findings and real-world performance data for antigen tests stems primarily from methodological variations in study design, particularly the distribution of viral loads in sample populations [17]. While manufacturer-reported sensitivities often exceed 80% [9], real-world studies frequently report lower values, such as the 59% overall sensitivity observed in a Brazilian study of 2,882 symptomatic individuals [4]. This discrepancy underscores the importance of standardized post-market surveillance.

Regulatory implications are significant, as evidenced by findings that only 21% of FDA-authorized rapid antigen tests had postapproval studies conducted according to manufacturer instructions [14] [11]. Furthermore, performance variability between test brands can be substantial, with one study reporting 70% sensitivity for the IBMP TR Covid Ag kit compared to 49% for the TR DPP COVID-19 - Bio-Manguinhos test [4] [9].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings highlight the necessity of: (1) accounting for viral load distributions when evaluating test performance; (2) implementing standardized benchmarking protocols across studies; and (3) conducting robust post-market surveillance to verify real-world performance. Future diagnostic development should focus on maintaining high specificity while improving sensitivity in low viral load scenarios, potentially through enhanced detection methodologies or multi-target approaches.

The diagnostic performance of rapid antigen tests (Ag-RDTs) for SARS-CoV-2 is fundamentally governed by the viral load present in patient samples, most commonly proxied by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) cycle threshold (Ct) values. This inverse relationship between Ct values and antigen test sensitivity represents a critical parameter for researchers, clinical microbiologists, and public health officials interpreting test results and designing testing strategies. Ct values indicate the number of amplification cycles required for viral RNA detection in qRT-PCR, with lower values corresponding to higher viral loads [18]. Antigen tests, which detect viral nucleocapsid proteins rather than nucleic acids, demonstrate markedly variable sensitivity across this viral load spectrum, creating significant implications for their appropriate application in different clinical and public health contexts [19] [4]. Understanding this relationship is essential for optimizing test utilization, particularly when differentiating between diagnostic scenarios requiring high sensitivity versus those where rapid results provide greater utility despite reduced sensitivity.

Quantitative Data: The Inverse Correlation Between Ct Values and Antigen Test Sensitivity

Substantial clinical evidence confirms that antigen test sensitivity declines precipitously as Ct values increase (indicating lower viral loads). This relationship follows a predictable pattern across multiple test brands and study populations, though specific sensitivity thresholds vary between products.

Table 1: Antigen Test Sensitivity Across PCR Ct Value Ranges

| Ct Value Range | Viral Load Category | Reported Sensitivity Ranges | Key Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| <20 | Very High | 90.9% - ~100% | [4] [13] |

| 20-25 | High | ~80% - 100% | [4] [13] |

| 25-30 | Moderate | 47.8% - Decreases significantly | [4] [13] |

| ≥30 | Low | 5.6% - <30% | [4] [1] |

A comprehensive Brazilian study with 2,882 symptomatic individuals demonstrated this relationship clearly, showing agreement between antigen tests and PCR dropped from 90.85% for samples with Cq <20 to just 5.59% for samples with Cq ≥33 [4]. This trend persists across diverse populations and settings. Research from an emergency department in Seoul confirmed that antigen test positivity rates fell significantly as Ct values increased, with most false-negative antigen results occurring in samples with higher Ct values [18]. Similarly, a manufacturer-independent evaluation of five rapid antigen tests in Scandinavian test centers found that sensitivity variations between tests were substantially influenced by the underlying Ct value distribution of the study population [20].

The correlation between test band intensity and Ct values further reinforces this relationship. One study performing semi-quantitative evaluation of antigen test results found a strong negative correlation (r = -0.706) between Ct values and antigen test band color intensity, with weaker bands observed in samples with higher Ct values [13].

Standardizing Performance Comparisons: Accounting for Ct Value Distribution in Study Design

Cross-study comparisons of antigen test performance are complicated by substantial variations in the Ct value distributions of study populations. Differences in sampling methodologies—such as enrichment for high- or low-Ct specimens—can significantly bias sensitivity estimates and limit generalizability [19].

Statistical Correction Methodology

Researchers have developed statistical frameworks to address this confounding factor by modeling percent positive agreement (PPA) as a function of Ct values and recalibrating results to a standardized reference distribution:

Modeling PPA Function: Using logistic regression on paired antigen test and qRT-PCR results to model the probability of antigen test positivity across the Ct value spectrum [19] [21].

Reference Distribution Application: Applying the derived PPA function to a standardized reference Ct distribution to calculate bias-corrected sensitivity estimates [19].

Performance Standardization: This adjustment enables more accurate comparisons of intrinsic test performance across different studies and commercial suppliers by removing variability introduced by differing viral load distributions [19].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Antigen Test Performance Studies

| Research Component | Specific Function | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standard | Gold-standard comparator for sensitivity/specificity | qRT-PCR with Ct value reporting [4] [13] |

| Viral Transport Medium (VTM) | Preserve specimen integrity during transport | Used in paired sampling designs [4] [20] |

| Protein Standards | Quantitative test strip signal calibration | Recombinant nucleocapsid protein [21] |

| Inactivated Virus | Analytical sensitivity determination | Heat-inactivated SARS-CoV-2 for LoD studies [21] |

| Digital Imaging Systems | Objective test line intensity measurement | Cell phone cameras with standardized imaging conditions [21] |

This methodology was validated using clinical data from a community study in Chelsea, Massachusetts, which demonstrated that raw sensitivity estimates varied substantially between test suppliers due to differing Ct distributions in their sample populations. After statistical adjustment to a common reference standard, these biases were reduced, enabling more equitable performance comparisons [19].

Experimental Protocols: Assessing Antigen Test Performance Across Viral Loads

Paired Clinical Sample Testing Protocol

The fundamental methodology for establishing the relationship between Ct values and antigen test performance involves concurrent testing of clinical samples with both antigen tests and qRT-PCR:

Sample Collection: Consecutive symptomatic individuals provide paired nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal, or combined swab specimens [4] [20] [13].

Parallel Testing: One swab is processed immediately using the rapid antigen test according to manufacturer instructions, while the other is placed in viral transport medium for qRT-PCR analysis [4] [20].

Ct Value Determination: RNA extraction followed by qRT-PCR amplification with Ct value recording for positive samples [4] [13].

Data Analysis: Calculate antigen test sensitivity stratified by Ct value ranges and model the relationship using statistical methods such as logistic regression [19] [4].

Laboratory-Based Quantitative Framework

For more rigorous analytical performance assessment beyond clinical sampling, a laboratory-anchored framework can be implemented:

This integrated approach combines analytical measurements with human factors to generate predictive models of real-world test performance. The methodology involves characterizing the test strip signal intensity response to varying concentrations of target recombinant protein and inactivated virus, typically using serial dilutions and digital imaging of test strips to quantify signal intensity [21]. The limit of detection is then statistically characterized using the visual acuity of multiple observers, representing the probability distribution of naked-eye detection thresholds across the user population [21]. Finally, calibration curves are established between qRT-PCR Ct values and viral concentrations, enabling the composition of a Bayesian predictive model that estimates the probability of positive antigen test results as a function of Ct values [21].

Implications for Diagnostic Applications and Public Health Strategy

The deterministic relationship between Ct values and antigen test performance has profound implications for their appropriate utilization across different clinical scenarios.

Diagnostic Strategy Considerations

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines recommend antigen testing for symptomatic individuals within the first five days of symptom onset when viral loads are typically highest, with pooled sensitivity of 89% (95% CI: 83% to 93%) during this period [22]. This sensitivity declines significantly to 54% when testing occurs after five days of symptoms [22]. For asymptomatic individuals, antigen test sensitivity is substantially lower (pooled sensitivity 63%), reflecting the higher proportion of pre-symptomatic or low viral load cases in this population [22].

Molecular testing remains the method of choice when diagnostic certainty is paramount, particularly for immunocompromised patients, hospital admissions, or when clinical suspicion is high despite a negative antigen test [5] [22]. The high specificity of antigen tests (consistently >99%) means positive results are highly reliable and actionable without confirmatory testing across most prevalence scenarios [5] [22].

Transmission Risk Assessment

The correlation between Ct values and antigen test performance has important implications for transmission control. Since antigen tests are most likely to be positive when viral loads are high (typically Ct <25-30), they effectively identify individuals with the highest probability of being infectious [18]. This characteristic makes them valuable tools for rapid isolation of contagious individuals in emergency departments, hospitals, and community settings, despite their lower overall sensitivity compared to PCR [18].

The inverse relationship between Ct values and antigen test sensitivity is a fundamental characteristic that must guide test selection, interpretation, and application across clinical and public health settings. Antigen tests serve as effective tools for identifying contagious individuals during the early, high viral load phase of infection, while PCR remains essential for definitive diagnosis, particularly in low viral load scenarios. Future test development should focus on improving sensitivity across the viral load spectrum while maintaining the speed, accessibility, and cost advantages that make rapid antigen tests valuable components of comprehensive diagnostic and infection control strategies.

Within the critical framework of diagnostic test performance, the high specificity of rapid antigen assays represents a cornerstone of their utility in pandemic control and clinical decision-making. Specificity, defined as a test's ability to correctly identify true negative cases, is the metric that ensures false alarms are minimized and resources are efficiently allocated. While the lower sensitivity of antigen tests compared to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has been extensively documented, their consistently high specificity deserves focused examination, particularly for researchers and drug development professionals optimizing diagnostic strategies. This guide provides a detailed, data-driven comparison of antigen and PCR test performance, with a specialized focus on the experimental protocols and quantitative evidence underlying the exceptional true-negative rate of antigen assays.

Core Concepts: Specificity, Sensitivity, and Diagnostic Utility

Defining the Diagnostic Metrics

In any diagnostic evaluation, sensitivity and specificity form an interdependent pair of performance characteristics.

- Sensitivity (Positive Agreement): The proportion of actual positives correctly identified by the test. High sensitivity is crucial for ruling out disease.

- Specificity (True-Negative Rate): The proportion of actual negatives correctly identified by the test. High specificity is essential for confirming disease and avoiding false alarms.

The inverse relationship between these metrics often necessitates a balanced approach based on the clinical or public health context. Antigen tests have carved a distinct niche by offering extremely high specificity, making them particularly valuable in situations where a positive result must be trusted to initiate immediate isolation or treatment.

The Technical Foundation of Specificity

The high specificity of antigen tests stems from their core detection mechanism. These lateral flow immunochromatographic assays utilize highly selective monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies that bind to specific viral antigen epitopes, typically the nucleocapsid (N) protein in SARS-CoV-2 [23]. This antibody-antigen interaction is fundamentally designed to minimize cross-reactivity with other pathogens or human proteins, thereby yielding a low false-positive rate. The result is a test that, when positive, provides a highly reliable indication of active infection.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Extensive real-world studies and meta-analyses have consistently validated the high specificity of antigen tests, even as sensitivity varies more significantly.

Table 1: Overall Diagnostic Accuracy of SARS-CoV-2 Antigen Tests vs. PCR

| Metric | Antigen Test Performance | PCR Test Performance | Contextual Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Specificity | 99.3% (95% CI 99.2–99.3%) [5] | Approaching 100% (Gold Standard) [24] [25] | Antigen specificity remains exceptionally high across most brands and settings. |

| Overall Sensitivity | 69.3% (95% CI 66.2–72.3%) [5] | >95% (Gold Standard) [1] | Highly dependent on viral load, symptoms, and timing. |

| Positive Predictive Value (PPV) | Ranges from 81% (5% prevalence) to 95% (20% prevalence) [5] | >99% in most clinical scenarios | Directly tied to disease prevalence; higher prevalence increases PPV. |

| Negative Predictive Value (NPV) | >95% across prevalence scenarios of 5-20% [5] | >99% in most clinical scenarios |

Table 2: Impact of Patient and Testing Factors on Antigen Test Sensitivity

| Factor | Impact on Sensitivity | Effect on Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Symptomatic Status | 73.0% in symptomatic vs. 54.7% in asymptomatic individuals [5] | Remains high (≈99%) in both groups [5] |

| Viral Load (Ct Value) | 90.85% for Cq < 20 (high load) vs. 5.59% for Cq ≥ 33 (low load) [4] | Specificity is largely independent of viral load. |

| Duration of Symptoms | 80.9% in first week vs. 53.8% in second week [5] | Not reported to significantly affect specificity. |

| Test Brand | Wide variation: 34.3% to 91.3% in symptomatic patients [5] | Most brands maintain specificity >97% [5] [14] |

The data in Table 1 underscores a critical finding: while the sensitivity of antigen tests is variable and often moderate, their specificity is consistently and reliably high, frequently exceeding 99% [5]. This means that in a population with a prevalence of 5%, an antigen test would correctly identify about 95 out of 100 positive results as positive, with a negative predictive value remaining above 95% [5].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Specificity

For researchers validating diagnostic performance, understanding the standard methodological framework for determining specificity is essential. The following workflow outlines the common comparative design.

Core Methodology Explained

The standard protocol for determining specificity involves a head-to-head comparison with the gold standard, PCR, in a cohort that includes both infected and non-infected individuals.

- Cohort Selection & Sample Collection: Studies typically enroll a diverse cohort, including individuals presenting with symptoms suggestive of infection and asymptomatic individuals, to ensure a representative sample. As detailed in a Brazilian cross-sectional study, paired swabs are collected simultaneously from each participant to eliminate variability [4]. One swab is placed in viral transport medium (VTM) for PCR analysis, while the other is used directly for the rapid antigen test.

- Reference Standard Testing (PCR): The PCR sample undergoes nucleic acid extraction, followed by reverse transcription and amplification using primers and probes specific to viral genes (e.g., N, E, ORF1ab) [24] [23]. The resulting Cycle threshold (Ct) value serves as a quantitative measure of viral load, with lower Ct values indicating higher viral loads [4] [23]. A sample is typically considered positive if the Ct value is below a predetermined cutoff (e.g., 35-40) [13].

- Index Test Processing (Antigen Assay): The antigen test swab is processed according to the manufacturer's instructions, typically involving immersion in a buffer solution and application to the test cassette. The test operates on a lateral flow immunoassay principle, where labeled antibodies bind to the viral antigen, forming a visible line on the test strip [23]. The result is read visually or instrumentally within 15-30 minutes.

- Data Analysis & Specificity Calculation: Results are compiled into a 2x2 contingency table. Specificity is calculated as the number of true negatives (samples negative by both antigen test and PCR) divided by the total number of PCR-negative samples [4] [5]. This provides the proportion of uninfected individuals who were correctly identified by the antigen test.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Diagnostic Test Validation

| Reagent/Material | Critical Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Paired Swab Kits | Ensures identical sample collection for both index and reference tests, minimizing pre-analytical variability. |

| Viral Transport Medium (VTM) | Preserves viral integrity for PCR testing during transport and storage. |

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolates high-purity viral RNA from patient samples, a critical step for reliable PCR results. |

| PCR Master Mixes | Contains enzymes (e.g., Taq polymerase), dNTPs, and buffers essential for cDNA synthesis and DNA amplification. |

| Primers & Probes | Short, specific nucleotide sequences that bind to target viral genes, enabling selective amplification and detection. |

| Lateral Flow Test Cassettes | The device containing the nitrocellulose membrane strip with immobilized antibodies for antigen capture and detection. |

| Reference Antigens | Purified viral proteins used as positive controls to verify test functionality and performance. |

Statistical Modeling and Public Health Impact

Interpreting Discordant Results

The high specificity of antigen tests directly informs how to handle discordant results—particularly a positive antigen test followed by a negative PCR test. A model developed for this scenario estimated that in a context of low community prevalence, a patient with this discordant result had only a 15.4% chance of actually being infected [26]. This low probability is a direct consequence of high test specificity; when disease prevalence is low, even a test with an excellent specificity rate will generate a number of false positives that can outweigh the true positives. Therefore, in low-prevalence settings, a negative confirmatory PCR result is highly reliable in indicating that the initial positive antigen test was a false positive [26].

Pathway to Public Health Application

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow from test performance characteristics to public health application, highlighting the role of high specificity.

The body of evidence conclusively demonstrates that high specificity is a robust and reliable feature of rapid antigen assays. While their sensitivity is dependent on viral load and clinical context, the ability of these tests to correctly identify true negatives is consistently excellent. For researchers and public health officials, this performance profile makes antigen tests a powerful tool for specific applications: confirming infection when positive, enabling rapid isolation and contact tracing, and efficiently screening populations in moderate to high prevalence settings. Understanding this "specificity in focus" allows for the strategic deployment of antigen tests within a broader diagnostic ecosystem, where they complement, rather than compete with, the high sensitivity of PCR. Future development should continue to leverage the robust specificity of immunoassay platforms while striving to improve sensitivity at lower viral loads.

Strategic Test Deployment: Matching Methodology to Clinical and Public Health Objectives

The strategic application of SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic tests is a critical component of effective public health response. Within this framework, a clear understanding of the performance characteristics of Antigen-Detecting Rapid Diagnostic Tests (Ag-RDTs) versus the gold standard Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests (NAATs), such as PCR, across different population groups is essential for researchers and clinicians. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provide structured guidance on test utilization, grounded in the fundamental metrics of sensitivity and specificity. Diagnostic sensitivity refers to a test's ability to correctly identify those with the disease (true positive rate), while diagnostic specificity indicates its ability to correctly identify those without the disease (true negative rate) [4]. This guide objectively compares the performance of antigen tests against PCR, synthesizing current guidelines and supporting experimental data to inform decision-making in research and clinical practice.

Official Guidelines: WHO and CDC Testing Frameworks

World Health Organization (WHO) Recommendations

The WHO has established minimum performance requirements for Ag-RDTs to be considered for deployment. These criteria are intentionally structured around the context of use:

- Minimum Performance: Ag-RDTs should meet or exceed ≥80% sensitivity and ≥97% specificity compared to NAAT [20] [13].

- Symptomatic Individuals: Ag-RDTs are primarily recommended for use in individuals presenting with symptoms consistent with COVID-19. Testing should be conducted within the first 5-7 days of symptom onset when viral loads are typically highest [13].

- Asymptomatic Individuals: The WHO advises that Ag-RDTs can be used for testing asymptomatic individuals, particularly as part of serial testing strategies during outbreaks or for contact tracing. However, a negative result in an asymptomatic person may require confirmation with a NAAT due to the higher risk of false negatives [13].

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and IDSA Guidelines

The CDC's guidance and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines provide a nuanced framework that aligns with the WHO's principles, further refining the application based on symptomatic status:

- Symptomatic Individuals (IDSA Recommendation): For symptomatic individuals suspected of having COVID-19, the IDSA panel recommends a single Ag test over no test (strong recommendation, moderate certainty evidence). A positive Ag result, due to its high specificity, can be used to guide treatment and isolation without confirmation. However, if clinical suspicion remains high despite a negative Ag test, confirmation with a NAAT is recommended [22].

- Asymptomatic Individuals: The IDSA guidance notes that the pooled sensitivity of Ag testing in asymptomatic individuals is substantially lower (63%) than in symptomatic populations. This underscores the need for caution when interpreting negative results in this group [22].

- Test Selection Hierarchy: When resources and logistics permit, the IDSA suggests using standard NAAT over Ag tests due to superior sensitivity. The value of rapid Ag testing is highest when timely NAAT is unavailable, as it allows for rapid isolation and contact tracing [22].

Comparative Performance Data: Antigen Tests vs. PCR

The following tables synthesize quantitative data from manufacturer-independent evaluations and guideline summaries, providing a clear comparison of test performance.

| Population | Sensitivity Range | Specificity Range | Key Influencing Factors | Source / Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptomatic | 63% - 81% | ≥99% | Timing after symptom onset (highest within first 5 days) | IDSA Guideline [22] |

| Asymptomatic | ~63% | ≥99% | Viral load prevalence; single vs. serial testing | IDSA Guideline [22] |

| Real-World (Symptomatic) | 59% (Overall) | 99% | Test brand, viral load | Brazilian Cohort (n=2882) [4] |

| Real-World (Various Brands) | 53% - 90% | 97.8% - 99.7% | Manufacturer, intended user technique | Scandinavian SKUP Evaluations [20] |

Table 2: Impact of Viral Load on Ag-RDT Performance

| Viral Load Indicator | Ag-RDT Sensitivity | Implications for Test Application |

|---|---|---|

| High Viral Load (Ct < 25) | Very High (e.g., ~90-100% agreement with PCR) | Ag-RDT is highly reliable for detecting infectious individuals [4] [13]. |

| Low Viral Load (Ct ≥ 33) | Very Low (e.g., 5.6% agreement with PCR) | Ag-RDT is likely to yield false negatives; PCR is required for detection [4]. |

| Correlation | Strong inverse correlation between Ct value and antigen test band intensity | Semi-quantitative visual interpretation may offer a crude gauge of infectiousness [13]. |

Key Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Understanding the data supporting these guidelines requires an overview of the experimental methodologies employed in key studies.

Real-World Diagnostic Accuracy Study

A large-scale, cross-sectional study in Brazil (2022) provides a robust example of real-world Ag-RDT evaluation [4].

- Objective: To determine the real-world accuracy of SARS-CoV-2 antigen tests compared to quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR).

- Participant Cohort: 2,882 symptomatic individuals presenting within the public healthcare system.

- Specimen Collection: Two nasopharyngeal swabs were collected simultaneously from each participant.

- Testing Protocol: One swab was analyzed immediately using one of two Ag-RDT brands (TR DPP or IBMP TR Covid Ag). The other swab was stored in viral transport medium at -80°C for subsequent blinded qPCR analysis using the CDC's RT-PCR diagnostic protocol.

- Data Analysis: Sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and positive/negative predictive values were calculated. Results were stratified by qPCR cycle threshold (Cq) values as a proxy for viral load.

Multi-Brand Evaluation and User-Friendliness Assessment

The Scandinavian SKUP collaboration performed prospective, manufacturer-independent evaluations of five Ag-RDTs to assess both performance and usability [20].

- Study Setting & Participants: Consecutive enrolment of individuals at COVID-19 test centres in Norway and Denmark. The intended sample size was at least 100 PCR-positive and 100 PCR-negative participants.

- Procedure: Duplicate samples were collected for the Ag-RDT and for RT-PCR. The Ag-RDT was performed immediately by test centre employees, the intended users of the tests.

- User-Friendliness Evaluation: Employees completed a structured questionnaire to rate the tests on criteria such as clarity of instructions, ease of procedure, and result interpretation.

- Analysis: Diagnostic sensitivity and specificity were calculated with 95% confidence intervals. User-friendliness feedback was synthesized into an overall rating.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision pathway for test application as recommended by health authorities, integrating the critical factors of symptomatic status and test purpose.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

For researchers designing studies to evaluate diagnostic test performance, the following reagents and materials are essential.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Diagnostic Test Evaluation

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Nasopharyngeal/Oropharyngeal Swabs | Standardized collection of human respiratory specimen for paired testing [4] [13]. |

| Viral Transport Medium (VTM) | Preservation of virus viability and nucleic acid integrity for transport and storage prior to PCR analysis [4] [20]. |

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality viral RNA from clinical samples, a critical step for RT-PCR [4]. |

| RT-PCR Master Mixes & Assays | Amplification and detection of specific SARS-CoV-2 gene targets (e.g., N, ORF1ab) using fluorescent probes [4] [13]. |

| Quantified SARS-CoV-2 Controls | Standardized virus stocks (e.g., PFU/mL, RNA copies/mL) for determining the limit of detection (LOD) and evaluating variant cross-reactivity [27]. |

| Ag-RDT Test Kits | The point-of-care immunoassays being evaluated, used according to manufacturer's instructions for use (IFU) [20]. |

Point-of-care (POC) testing is defined by its operational context rather than by technology alone—it encompasses any diagnostic test performed at or near the patient where the result enables a clinical decision to be made and an action taken that leads to an improved health outcome [28]. In resource-limited settings (RLS), where access to centralized laboratory facilities is often constrained, the World Health Organization (WHO) has established the "ASSURED" criteria for ideal POC tests: Affordable, Sensitive, Specific, User-friendly, Rapid and robust, Equipment-free, and Deliverable to those who need them [28]. Within this framework, rapid antigen detection tests (Ag-RDTs) have emerged as transformative tools for infectious disease management, offering distinct operational advantages that justify their deployment despite recognized limitations in analytical sensitivity compared to molecular methods.

The fundamental distinction between antigen and molecular testing lies in their detection targets. Antigen tests detect specific proteins on the surface of pathogens using lateral flow immunoassay technology, typically providing results in 10-30 minutes [29]. In contrast, molecular tests (including nucleic acid amplification tests or NAATs) detect pathogen genetic material (DNA or RNA) through amplification techniques like polymerase chain reaction (PCR), offering higher sensitivity but often requiring more complex equipment and longer processing times (15-45 minutes for POC molecular tests) [29]. This comparison guide objectively examines the performance characteristics and operational considerations of these testing modalities within the context of RLS and community settings, supported by experimental data and practical implementation frameworks.

Operational Advantages of Antigen Tests in Resource-Limited Settings

Speed, Simplicity, and Decentralization

The most significant operational advantage of antigen tests in RLS is their rapid turnaround time, which enables clinical decision-making during the same patient encounter. This immediacy eliminates the delays associated with sample transport to centralized laboratories, which can take days in remote settings and often results in patients lost to follow-up [28]. Antigen tests typically produce results within 10-30 minutes without requiring specialized laboratory equipment or highly trained personnel [29]. This simplicity allows deployment at various healthcare levels, including primary health clinics, mobile testing units, and even community-based settings by minimally trained lay providers.

Most antigen tests are CLIA-waived, enabling their use across a broad spectrum of clinical settings without requiring high-complexity laboratory certification [29]. The technical simplicity extends to sample preparation, which is often straightforward—many antigen tests use direct swabs without needing viral transport media or complex processing steps. This equipment-free operation aligns perfectly with the WHO ASSURED criteria, particularly important in settings with unreliable electricity, limited refrigeration capabilities, or inadequate technical support infrastructure [28].

Economic and Logistical Considerations

Antigen tests present compelling economic advantages in resource-constrained environments. Both the per-test cost and equipment requirements are significantly lower than molecular alternatives [29]. For health systems with limited budgets, these cost differentials enable broader testing coverage and more sustainable program implementation. The minimal maintenance requirements and lack of dependency on proprietary cartridges or reagents further reduce the total cost of ownership and eliminate supply chain vulnerabilities that can plague more complex diagnostic systems.

The operational independence of antigen tests from sophisticated laboratory infrastructure makes them particularly valuable for last-mile delivery in remote or conflict-affected areas. Their robustness—including tolerance of temperature variations and extended shelf life—enhances deliverability to marginalized populations [28]. This combination of affordability and deliverability addresses two critical barriers to diagnostic access in RLS, explaining why antigen tests have become foundational to infectious disease control programs for conditions like malaria, HIV, tuberculosis, and SARS-CoV-2 in low-resource contexts [28].

Comparative Performance: Antigen Tests Versus Molecular Methods

Analytical Sensitivity and Specificity

The primary trade-off for the operational advantages of antigen tests is reduced analytical sensitivity compared to molecular methods. Antigen tests generally have moderate sensitivity (50-90%, depending on the pathogen and test brand) while maintaining high specificity (>95%) [29]. Molecular tests, in contrast, typically demonstrate sensitivity >95% and specificity >98% for most pathogens [29]. This performance differential stems from fundamental methodological differences: antigen tests detect surface proteins without amplification, while molecular tests amplify target genetic material, enabling detection of minute quantities of pathogen.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of SARS-CoV-2 Testing Modalities

| Performance Characteristic | Antigen POC Tests | Molecular POC Tests | Laboratory-based RT-PCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Sensitivity | 59-70.6% [4] [30] | >95% [29] | >95% (reference standard) [30] |

| Typical Specificity | 94-99% [4] [30] | >98% [29] | >99% [30] |

| Turnaround Time | 10-30 minutes [29] | 15-45 minutes [29] | Hours to days (including transport) [28] |

| Approximate Cost | Low [29] | Moderate to High [29] | High (includes infrastructure) [28] |

| Equipment Needs | Minimal [29] | Analyzer required [29] | Sophisticated laboratory equipment [28] |

| Operational Complexity | Usually CLIA-waived [29] | Often CLIA-moderate complexity [29] | High-complexity certification [28] |

| Best Use Case | High-prevalence settings, rapid screening [29] | High-accuracy needs, low-prevalence settings [29] | Confirmatory testing, asymptomatic screening [30] |

Viral Load Dependence and Clinical Utility

The sensitivity of antigen tests demonstrates strong dependence on viral load, as evidenced by their correlation with RT-PCR cycle threshold (Ct) values. A 2025 Brazilian study of 2,882 symptomatic individuals found overall antigen test sensitivity of 59% compared to RT-PCR, but this increased to 90.85% for samples with high viral load (Cq < 20) [4]. Conversely, agreement dropped significantly to 5.59% for samples with low viral load (Cq ≥ 33) [4]. This viral load dependence creates a useful epidemiological property: antigen tests are most likely to detect infections during the peak infectious period, effectively identifying those most likely to transmit disease.

A 2022 meta-analysis of 123 publications further quantified this relationship, finding pooled sensitivity of 70.6% for antigen-based POC tests compared to 92.8% for molecular POC tests [30]. The specificity rates were more comparable—98.9% for antigen tests versus 97.6% for molecular POC tests [30]. This specificity makes false positives relatively uncommon, preserving the positive predictive value in appropriate prevalence settings. When disease prevalence is high, the positive predictive value of antigen testing increases, making rapid antigen results particularly useful during peak seasonal outbreaks [29].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Diagnostic Accuracy Studies

Rigorous evaluation of antigen test performance requires standardized comparative studies against reference molecular methods. The following protocol outlines a typical diagnostic accuracy study design:

Study Population and Sample Collection: Consecutive symptomatic patients meeting clinical case definitions (e.g., suspected COVID-19 with respiratory symptoms lasting <7 days) are enrolled. Two combined oro/nasopharyngeal swabs are collected simultaneously by healthcare workers to minimize sampling variability [13]. One swab is placed in viral transport medium for RT-PCR analysis, while the other is placed in a sterile tube for immediate antigen testing [13].

Laboratory Procedures: The antigen test is performed according to manufacturer instructions, with results interpreted within the specified timeframe (typically 15-30 minutes) [13]. To minimize interpretation bias, a single trained operator evaluates all antigen tests, blinded to RT-PCR results. For the reference standard, RT-PCR is performed using validated kits targeting multiple SARS-CoV-2 genes (e.g., N, ORF1a, ORF1b), with Ct values <35 considered positive [13].

Statistical Analysis: Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) are calculated with 95% confidence intervals using 2x2 contingency tables. Correlation between antigen test band intensity and Ct values can be assessed using Pearson correlation tests [13]. Performance stratification by viral load (Ct value ranges), days since symptom onset, and other clinical variables provides additional insights into test characteristics under real-world conditions.

Quantitative Laboratory-Anchored Framework

Emerging methodologies enable more sophisticated antigen test evaluation through quantitative, laboratory-anchored frameworks that link image-based test line intensities to naked-eye limits of detection (LoD) [21]. This approach involves:

Signal Response Characterization: Digital images of antigen test strips are analyzed to calculate normalized signal intensity across dilution series of target recombinant protein and inactivated virus. The signal intensity is modeled using adsorption models like the Langmuir-Freundlich equation: I = kCᵇ/(1 + kCᵇ), where I is normalized signal intensity, C is concentration, k is adsorption constant, and b is an empirical exponent [21].

Visual Detection Thresholds: The statistical characterization of LoD incorporates observer visual acuity by determining the probability density function of the minimal detectable signal intensity across a representative user population [21]. This acknowledges that real-world performance depends on both test strip chemistry and human interpretation capabilities.

Bayesian Predictive Modeling: A Bayesian model integrates the signal response characterization, visual detection thresholds, and Ct-to-viral-load calibration to predict positive percent agreement (PPA) as a continuous function of qRT-PCR Ct values [21]. This methodology enables performance prediction under real-world conditions before large-scale clinical trials, accelerating test deployment during outbreaks.

Figure 1: Antigen Test Evaluation Framework Integrating Laboratory and User Factors

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Antigen Test Development and Evaluation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Antigen Proteins | Serve as reference standards for test development and calibration | High-purity target proteins (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid) at known concentrations [21] |

| Inactivated Virus Stocks | Mimic natural infection for analytical sensitivity determination | Heat-inactivated virus with known concentration (PFU/mL) [21] |

| Clinical Specimens | Validate test performance with real human samples | Combined oro/nasopharyngeal swabs from symptomatic patients [13] |

| Viral Transport Medium (VTM) | Preserve specimen integrity during transport and storage | Compatible with both antigen testing and RT-PCR reference methods [13] |

| Lateral Flow Test Strips | Platform for antigen detection | Nitrocellulose membrane with immobilized capture and control antibodies [21] |

| qRT-PCR Master Mix | Reference standard for comparative studies | Multiplex assays targeting conserved genomic regions (e.g., N, ORF1ab genes) [4] |

| Digital Imaging System | Objective test result quantification | Standardized lighting conditions and resolution for band intensity measurement [21] |

Discussion: Strategic Implementation in Resource-Limited Settings

Context-Appropriate Test Selection

The choice between antigen and molecular testing in RLS requires careful consideration of clinical context, operational constraints, and epidemiological factors. Antigen tests offer the greatest utility in high-prevalence settings where their positive predictive value is maximized, and for rapid screening during outbreaks when immediate isolation decisions are necessary [29]. Their speed and simplicity make them ideal for triage in overcrowded healthcare facilities and for reaching remote communities without access to laboratory infrastructure.

Molecular tests remain preferred when diagnostic accuracy is paramount, particularly in low-prevalence settings, for confirmatory testing, and in high-risk patient populations (immunocompromised, elderly) where false negatives carry severe consequences [29]. The slightly longer turnaround time of POC molecular tests (15-45 minutes) may be acceptable when clinical management depends on definitive results. Emerging multiplex molecular panels that simultaneously detect multiple pathogens from a single sample provide additional value in cases with overlapping clinical presentations [29].

Hybrid Approaches and Future Directions

Strategic testing algorithms can leverage the complementary strengths of both modalities. A hybrid approach using antigen tests for initial screening with reflexive molecular testing for negative results in high-suspicion cases balances speed, cost, and accuracy [29]. This approach maximizes resource utilization by reserving more expensive molecular testing for cases where it provides the greatest clinical value.

Future developments are likely to narrow the performance gap between antigen and molecular testing. Ultrasensitive digital immunoassays are boosting antigen detection to near-PCR levels, while advances in microfluidics and cartridge-based platforms are making molecular testing faster, simpler, and more affordable [29]. The expansion of multiplex respiratory panels in POC formats will enable rapid differentiation between pathogens with similar symptoms, streamlining both diagnosis and treatment. For resource-limited settings, these technological advances promise to enhance diagnostic capabilities while maintaining the operational advantages that make decentralized testing feasible.

Figure 2: Clinical Decision Algorithm for Test Selection in Resource-Limited Settings

In the diagnostic landscape, the choice between rapid antigen tests and polymerase chain reaction tests often presents a trade-off between speed and accuracy. While antigen tests offer rapid results, their variable sensitivity, particularly in low viral load scenarios, establishes the critical role of PCR as the gold standard for confirmatory testing and guiding targeted antiviral therapies. This guide examines the performance data and procedural frameworks that position PCR as an indispensable tool in clinical practice and drug development.

Diagnostic Performance: A Quantitative Comparison

The fundamental difference between antigen and PCR tests lies in their methodology: antigen tests detect specific viral proteins, while PCR amplifies and detects viral genetic material. This distinction underlies a significant gap in sensitivity, which is crucial for reliable diagnosis.

Table 1: Comparative Diagnostic Accuracy of Antigen and PCR Tests

| Test Characteristic | Rapid Antigen Test (Ag-RDT) | PCR Test |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Sensitivity | 59.0% (95% CI: 0.56-0.62) [4] | 92.8% - 97.2% [1] |

| Sensitivity in Symptomatic | 69.3% - 73.0% [4] [5] | >95% [1] |

| Sensitivity in Asymptomatic | 54.7% (95% CI: 47.7-61.6) [5] | >95% [1] |

| Specificity | 99.3% (95% CI: 99.2-99.3) [5] | >99% [1] |

| Impact of Viral Load | Sensitivity drops to <30% at low viral loads [1] | Maintains high sensitivity across viral loads |

The dependency of antigen test accuracy on viral load is a critical limitation. One study demonstrated that while agreement between antigen and PCR results was high (90.85%) for samples with a high viral load, it decreased dramatically to 5.59% for samples with lower viral loads [4]. This performance chasm underscores the necessity of PCR for confirming negative antigen results in high-stakes situations.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Real-World Evaluation of Antigen Test Performance

A large cross-sectional study provides a template for robustly comparing test performances.

- Objective: To determine the real-world accuracy of SARS-CoV-2 antigen tests compared to qPCR within the Brazilian Unified Health System [4].

- Population: 2,882 symptomatic individuals.

- Sample Collection: Two nasopharyngeal swabs were collected simultaneously from each participant [4].

- Testing Protocol: One swab was analyzed immediately using a rapid antigen test kit (with results in 15 minutes). The other swab was stored in Viral Transport Medium at -80°C for subsequent RT-qPCR testing [4].

- Analysis: Statistical analysis determined sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and positive/negative predictive values. Performance was also analyzed relative to viral load, as indicated by quantification cycle values from the qPCR assay [4].

Broad-Range PCR for Antimicrobial Stewardship

Beyond viral detection, PCR methodologies are pivotal in managing complex bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial infections.

- Objective: To explore the clinical utility of Broad-Range PCR (BR-PCR) and its impact on antimicrobial treatment in a hospital cohort [31].

- Methodology: This retrospective evaluation analyzed 359 clinical specimens that underwent BR-PCR testing. The technique uses primers targeting conserved genetic regions, such as the 16S ribosomal RNA gene for bacterial identification, allowing for the detection of a wide spectrum of organisms [31].

- Clinical Utility Assessment: Test results were deemed to have "clinical utility" if they led to an adjustment (de-escalation, discontinuation) or confirmation of the initial antimicrobial regimen [31].

PCR in Antiviral Treatment Decision Pathways

The high sensitivity and specificity of PCR make it the cornerstone for initiating and tailoring antiviral therapy, especially for infections where early intervention is critical.

Diagram: PCR's Role in Antiviral Treatment Decisions

Clinical guidelines explicitly recommend PCR-based testing to guide treatment. For novel influenza A viruses, the CDC recommends initiating antiviral treatment "as soon as possible" for patients who are suspected, probable, or confirmed cases, with confirmation relying on molecular methods like RT-PCR [32]. Similarly, the IDSA guidelines for COVID-19 stress the importance of accurate diagnosis to determine disease severity and guide the use of antivirals and immunomodulators [33].

PCR testing is also fundamental in assessing antiviral efficacy in clinical trials and managing treatment. For instance, mathematical modeling of molnupiravir trials revealed that standard PCR assays might underestimate the drug's true potency because they detect mutated viral RNA fragments, highlighting the need for tailored virologic endpoints in trials for mutagenic antivirals [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Successful implementation of PCR testing and development relies on a core set of reagents and instruments.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for PCR-Based Diagnostics

| Reagent / Instrument | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Reverse Transcriptase | Converts viral RNA into complementary DNA for amplification. | Essential for detecting RNA viruses like SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza [35]. |

| Taq Polymerase | Thermally stable enzyme that amplifies the target DNA sequence. | Core component of all PCR reactions, including qRT-PCR [35]. |

| Primers & Probes | Short, specific nucleotide sequences that bind to and label the target genetic material. | Designed to target conserved regions of a virus (e.g., CDC 2019-nCoV primers) [4]. |