Advanced Morphological Identification of Parasite Eggs: From Traditional Microscopy to AI-Driven Diagnostics

This article provides a comprehensive overview of morphological identification techniques for parasite eggs, addressing the critical needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Advanced Morphological Identification of Parasite Eggs: From Traditional Microscopy to AI-Driven Diagnostics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of morphological identification techniques for parasite eggs, addressing the critical needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. We explore foundational principles of parasite egg morphology and the limitations of traditional manual microscopy. The content delves into advanced methodological applications, including AI and deep learning models like YOLO-based architectures and Convolutional Block Attention Modules that are revolutionizing diagnostic accuracy. We address key troubleshooting and optimization strategies for challenging imaging conditions and low-resource settings. Finally, we present rigorous validation and comparative analyses of emerging diagnostic platforms against established gold-standard methods, offering a complete perspective on current capabilities and future directions in parasitological research and drug discovery.

Fundamental Principles of Parasite Egg Morphology and Traditional Diagnostic Foundations

Core Morphological Characteristics of Major Helminth Eggs

The morphological identification of helminth eggs in stool samples remains a cornerstone of medical parasitology, essential for diagnosing infections that affect over a billion people globally [1] [2]. Despite advancements in molecular techniques, microscopy persists as the primary diagnostic method in most endemic regions due to its low cost and immediate availability [3] [4]. The accuracy of this method, however, hinges on the precise recognition of core morphological characteristics, which can be confounded by abnormal egg development, morphological similarities between species, and artifacts in sample preparation [3]. This technical guide details the essential morphological features of major helminth eggs and the standardized protocols for their identification, providing a critical resource for research and drug development initiatives focused on these neglected tropical diseases.

Core Morphological Characteristics

The reliable identification of helminth eggs relies on the careful assessment of key visual features. The table below summarizes the core morphological characteristics of major helminth eggs based on established morphological criteria [1].

Table 1: Core Morphological Characteristics of Major Helminth Eggs

| Helminth Species | Egg Size (µm) | Egg Shape | Shell Characteristics | Internal Features & Color | Key Distinctive Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascaris lumbricoides (fertile) | ≈85 x 60 [3] | Round to oval | Thick, mammillated (albuminoid coat) | Unsegmented embryo; Golden-brown [5] | Thick, mammillated coat stained brown |

| Ascaris lumbricoides (unfertile) | Elongated, up to 110 [3] | Irregular, longer | Thinner, mammillated | Amorphous, filled with refractile granules; Brown | Irregular shape with internal granules |

| Trichuris trichiura | ≈80 [3] | Oval or barrel-shaped | Thick, smooth | Bipolar plugs (unsegmented embryo); Yellow-brown | Bipolar, plug-like prominences |

| Hookworm | ≈85 x 20 [5] | Oval | Thin, transparent | 4-32 segmented embryo (blastomeres); Clear | Thin shell with segmented embryo |

| Taenia saginata | 30-40 | Round | Thick, radially striated | 6-hooked embryo (oncosphere); Brown | Thick, radially striated shell |

| Hymenolepis nana | 30-47 | Round or oval | Thin, with polar filaments | 6-hooked oncosphere; Colorless or light | Polar filaments between shell and oncosphere |

| Hymenolepis diminuta | 60-80 | Round or oval | Thick, yellow | 6-hooked oncosphere; Yellow | Larger than H. nana, no polar filaments |

| Schistosoma mansoni | ≈175 x 65 | Elongated oval | Thin, transparent | Mature miracidium; Yellow or golden | Large lateral spine near one pole |

Experimental Protocols for Morphological Identification

Sample Collection and Preparation

Proper specimen collection and processing are fundamental to preserving egg morphology for accurate identification.

- Specimen Collection: Helminth specimens collected during necropsies should be relaxed before fixation. This is achieved by placing live worms in warm (37–42°C) saline solution or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 8–16 hours until viability is lost. Specimens should then be cleaned of host tissue remnants using a soft brush to prevent obscuring morphological features [6].

- Egg Release for Analysis: Placing helminth specimens in distilled water or other hypotonic solution induces the release of eggs from the uterus, facilitating their collection for morphometric analysis. For instance, immersing the lung fluke Paragonimus mexicanus in water for 1–2 hours triggers egg release into the solution [6].

Standard Copromicroscopic Techniques

The following are widely used methods for the microscopic detection and quantification of helminth eggs.

- Kato-Katz Technique: This quantitative method involves placing a defined amount of stool (e.g., 41.7 mg) on a microscope slide and spreading it into a smear through a cellophane coverslip soaked in a glycerine-malachite green solution. The slide is examined under a light microscope, and eggs are identified based on morphology and counted. The number of eggs per gram of feces is calculated by multiplying the average egg count by 24 [7]. It is crucial to examine the smear within the appropriate time window, as prolonged clearing can cause swelling or dissolution of certain eggs, such as those of schistosomes and hookworms [3].

- Formalin-Ether Concentration Technique (FET): This qualitative method concentrates parasites from a larger stool sample. Stool is mixed with formalin to preserve organisms and then filtered. The filtrate is centrifuged with ether or ethyl acetate, which traps debris and fats in the solvent layer. The sediment at the bottom, which contains the concentrated parasites, is then examined microscopically [8].

- Sodium Nitrate Flotation (SNF): This technique utilizes a high-specific-gravity flotation solution (e.g., sodium nitrate) to separate helminth eggs from fecal debris. The stool sample is mixed with the solution and strained. After standing, eggs float to the surface and can be collected from the meniscus for microscopic examination [8].

Advanced Diagnostic and Research Workflows

The integration of traditional morphology with new technologies is shaping the future of helminth diagnosis. The following workflow illustrates this integrative approach.

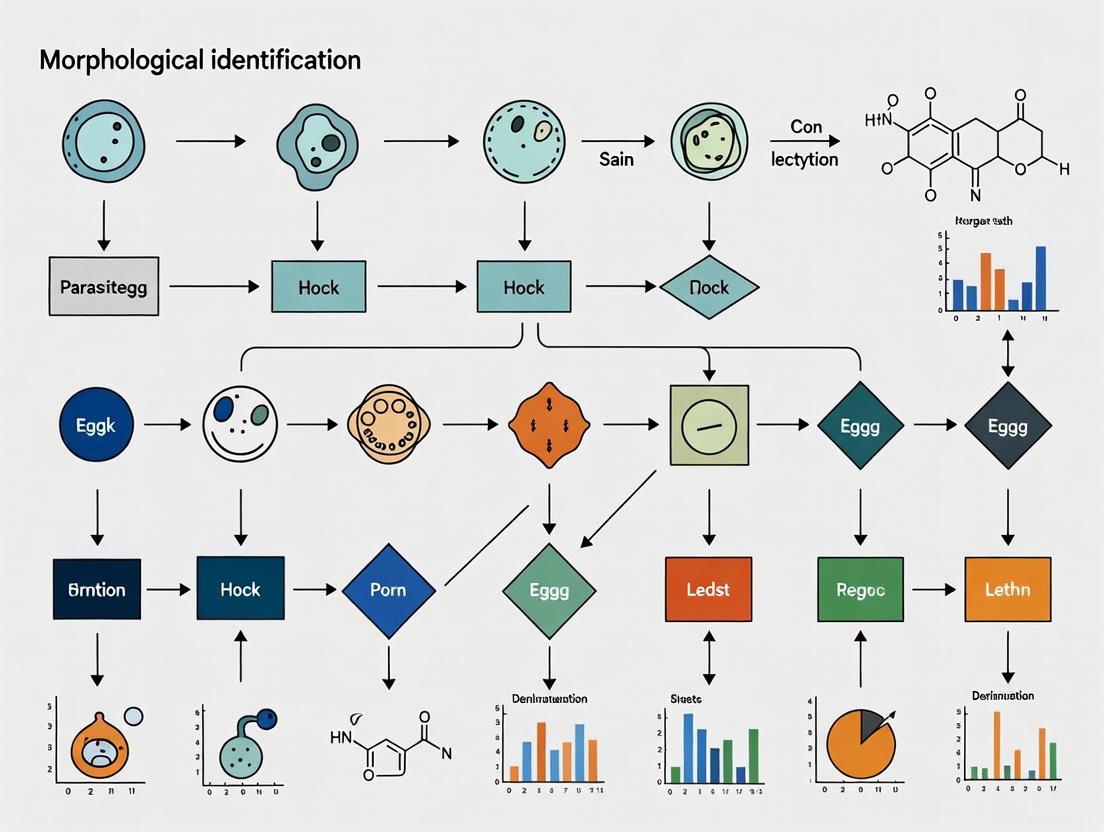

Diagram 1: Integrative taxonomy workflow for helminth identification, combining morphological, molecular, and digital pathology approaches [9] [4] [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Helminth Egg Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Glycerine-Malachite Green Solution | Clears and stains fecal debris for microscopy. | Kato-Katz smear preparation for egg visualization and quantification [7]. |

| 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin | Preserves helminth specimens and stool samples; fixes tissue for histology. | Sample preservation for FET; fixation of specimens for histopathological analysis [8] [6]. |

| Ethyl Acetate / Diethyl Ether | Solvent for lipid and debris extraction in concentration techniques. | Flotation and purification of parasite eggs in the Formalin-Ether Concentration Technique [8]. |

| Sodium Nitrate Flotation Solution | High-specific-gravity solution for buoyant separation of eggs. | Flotation of helminth eggs to the surface for easy collection in SNF [8]. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | Isotonic solution for specimen handling and relaxation. | Relaxing live helminths prior to morphological analysis to prevent contraction [6]. |

| Deep Learning Models (YOLOv7, CoAtNet) | AI-based object detection and classification of eggs in digital images. | Automated identification and quantification of eggs in whole-slide images [4] [2]. |

Challenges and Morphological Anomalies

A significant challenge in morphological identification is the occurrence of abnormal egg forms, which can complicate accurate diagnosis.

- Abnormal Nematode Egg Development: Highly abnormal forms of Ascaris lumbricoides eggs, including those with double morulae, giant eggs (up to 110 µm in length), and irregular shell shapes, have been observed in human populations with high infection intensity. Similar abnormalities, such as budded, triangular, and conjoined eggs, have been documented in experimental Baylisascaris procyonis infections in raccoons and dogs, particularly during the initial patency period [3].

- Abnormal Trematode Egg Morphology: Malformations in schistosome eggs have also been reported. For instance, Schistosoma haematobium eggs with variable spine morphology and S. mansoni eggs with double spines have been documented. Historical evidence suggests these abnormalities may be associated with egg production by immature worms [3].

- Impact of Technique on Morphology: The diagnostic technique itself can induce morphological artifacts. The Kato-Katz method is known to cause minor swelling and clearing of A. lumbricoides eggs and can lead to the collapse of schistosome eggs or dissolution of hookworm eggs if the smear is allowed to clear for too long [3]. This underscores the need for standardized examination timings.

The precise morphological identification of helminth eggs is a critical skill that underpins epidemiological surveillance, individual patient diagnosis, and the evaluation of interventional drug efficacy. While core characteristics provide a reliable foundation for identification, practitioners must be aware of the potential for morphological anomalies and technique-induced artifacts. The future of helminth diagnostics lies in an integrative approach that synergizes classical morphological expertise with advanced tools like deep learning and molecular biology. This multi-faceted methodology, as detailed in this guide, promises to enhance diagnostic accuracy and strengthen global efforts to control and eliminate helminth infections.

The morphological identification of parasite eggs, larvae, and cysts through microscopy remains a cornerstone of parasitological research and diagnosis. Despite advancements in molecular techniques, traditional methods based on flotation, sedimentation, and staining continue to provide the foundation for parasite detection in clinical, veterinary, and research settings [10] [11]. These techniques leverage the physical properties of parasitic structures—particularly their specific density and structural composition—to separate them from fecal debris and enhance their visibility for accurate identification [10]. The enduring value of these methods lies in their relatively low operational cost, moderate sensitivity and specificity, and their capacity to provide direct morphological evidence of infection, which is indispensable for species-level identification and burden assessment [10] [12].

Within the context of morphological identification research, understanding the technical principles, advantages, and limitations of each method is paramount. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these core techniques, supported by comparative data and detailed protocols, to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to select and implement the most appropriate methods for their specific applications.

Core Technical Principles and Comparative Analysis

The effectiveness of concentration techniques hinges on the specific density (relative density) of the medium used and the application of force (either gravitational or centrifugal) to separate parasitic elements from fecal debris [10]. The table below summarizes the fundamental principles and applications of the primary technique categories.

Table 1: Core Principles of Parasite Concentration Techniques

| Technique Category | Physical Principle | Primary Force Applied | Typical Recovery | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flotation | Suspension of fecal material in a medium with a specific density higher than that of parasite eggs/cysts (typically 1.20-1.35) [10]. | Spontaneous or centrifugal [10]. | Buoyant parasitic forms (e.g., nematode eggs, coccidian oocysts) that float to the surface [10]. | Can cause morphological distortion due to osmotic stress. Not ideal for heavy or operculated eggs [10]. |

| Sedimentation | Suspension of fecal material in a medium (often of lower specific density) where parasitic structures settle due to their greater density [10]. | Spontaneous (gravity) or centrifugal [10]. | A wider range of parasitic forms, including denser trematode eggs and operculated cestode eggs [10]. | Generally preserves morphology better. The process can be slower than flotation [10]. |

| Staining | Chemical interaction between dyes and specific structural components of the parasite (e.g., chitin in eggshells, acid-fastness of oocyst walls) [13] [14]. | Not applicable. | Enhances contrast and detail for specific identification and differentiation of species [13] [14]. | Requires expertise in interpretation. Some stains are permanent, while others are temporary [15]. |

A comparative study of four techniques for diagnosing Spirometra spp. eggs in wild carnivores demonstrated the profound impact of method selection on recovery rates. Sedimentation techniques (Lutz and modified Ritchie) significantly outperformed flotation techniques (Faust and modified Sheather), with the latter also causing a higher frequency of morphological alterations in the eggs [16]. Similarly, a Bayesian analysis of two spontaneous sedimentation tests (SST and Paratest) revealed generally high specificity (>93%) but low and variable sensitivity (35.8%-53.8%) for various parasites, underscoring the risk of underdiagnosis due to technical limitations [17].

The morphological details required for precise identification are extensively documented in resources such as the CDC's Comparative Morphology Tables. The following table consolidates key characteristics for common protozoan cysts, which are critical for microscopic differentiation.

Table 2: Differential Morphology of Common Protozoan Cysts Found in Human Stool [15]

| Species | Size (Diameter or Length) | Shape | Number of Nuclei (Mature Cyst) | Peripheral Chromatin | Cytoplasmic Inclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entamoeba histolytica | 10-20 µm (usual 12-15 µm) | Usually spherical | 4 | Fine, uniform granules | Chromatoid bodies with bluntly rounded ends |

| Entamoeba coli | 10-35 µm (usual 15-25 µm) | Usually spherical, occasionally oval or triangular | 8 | Coarse, irregular granules | Chromatoid bodies less frequent, splinter-like with pointed ends |

| Entamoeba hartmanni | 5-10 µm (usual 6-8 µm) | Usually spherical | 4 | Similar to E. histolytica | Chromatoid bodies with bluntly rounded ends |

| Endolimax nana | 5-10 µm (usual 6-8 µm) | Spherical to Oval | 4 | None | Chromatoid bodies typically absent |

| Iodamoeba bütschlii | 5-20 µm (usual 10-12 µm) | Ovoidal, ellipsoidal, or other shapes | 1 | None | Compact, well-defined glycogen mass |

Detailed Methodologies and Protocols

Sedimentation Techniques

Centrifugal-Sedimentation (Formalin-Ethyl Acetate Technique)

The formalin-ethyl acetate sedimentation technique is a widely used standard in clinical laboratories due to its broad recovery profile [11].

Reagents:

- 5% or 10% buffered formalin

- Ethyl acetate

- Saline or detergent solution

Procedure:

- Emulsification: Commingle approximately 1-2 g of stool (fresh or preserved in formalin) with 10 mL of 5% or 10% formalin in a centrifuge tube. Filter the suspension through a sieve (500-600 µm mesh) to remove large particulate matter [10] [11].

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the filtrate at 500 × g for 2-3 minutes. Decant the supernatant.

- Resuspension and Washing: Resuspend the sediment in fresh formalin, add saline to within a few centimeters of the tube rim, and recentrifuge. Decant the supernatant. This wash step may be repeated if necessary to clean the sediment.

- Ethyl Acetate Extraction: To the sediment, add 4-5 mL of 10% formalin (if not already present), fill the tube halfway with saline, and then add 3-4 mL of ethyl acetate. Stopper the tube and shake vigorously for 30 seconds. Remove the stopper carefully.

- Final Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 500 × g for 2-3 minutes. This step results in four layers: a plug of fecal debris at the top (ethyl acetate), a formalin layer, sedimented particulate matter, and the parasite-containing sediment at the very bottom.

- Examination: Loosen the debris plug from the tube sides with an applicator stick and decant the top three layers. The final sediment is used for preparing wet mounts (with or without iodine) and permanent stains for microscopic examination [11].

Flotation Techniques

Zinc Sulfate Flotation (Centrifugal-Flotation)

This technique is particularly effective for recovering protozoan cysts and some helminth eggs [10].

Reagents:

- Zinc sulfate solution, specific gravity 1.20 [10].

Procedure:

- Fecal Suspension: Prepare a fecal suspension as for the sedimentation technique and concentrate by centrifugation. Wash the sediment once with water.

- Flotation Medium: Resuspend the sediment in a small volume of zinc sulfate solution (specific gravity 1.18-1.20), then fill the tube to the brim with more zinc sulfate solution.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 500 × g for 2-3 minutes.

- Sample Collection: Place a coverslip on the top of the meniscus and allow it to stand for 5-10 minutes. Carefully lift the coverslip straight up and place it on a glass slide for immediate microscopic examination [10].

Staining Procedures

Staining is critical for visualizing internal structures and for identifying parasites that are difficult to detect with routine stains.

Modified Acid-Fast Staining for Coccidia

This technique is essential for identifying oocysts of Cryptosporidium, Cystoisospora, and Cyclospora species [14].

Reagents:

- Absolute Methanol

- Kinyoun's Carbol Fuchsin

- Acid Alcohol (3% HCl in 95% Ethanol)

- 3% Malachite green (or Methylene Blue) counterstain

Procedure:

- Smear Preparation: Prepare a thin smear from concentrated stool sediment on a glass slide and dry on a slide warmer at 60°C.

- Fixation: Flood the slide with absolute methanol for 1 minute to fix.

- Staining: Apply Kinyoun's Carbol Fuchsin and stain for 5 minutes. Rinse gently with distilled water.

- Decolorization: Decolorize with Acid Alcohol for 1-2 minutes or until the stain no longer streams off the slide. Rinse thoroughly with distilled water.

- Counterstaining: Apply the Malachite green counterstain for 1-2 minutes. Rinse with distilled water.

- Examination: Air-dry the slide and examine under oil immersion (100x objective). Coccidian oocysts stain pinkish-red against a green background [14].

Ziehl-Neelsen Staining for Differentiation ofTaeniaSpecies

This method allows for the differentiation of Taenia saginata and T. solium eggs, which is crucial for public health and clinical management [13].

Reagents:

- 3% Carbol Fuchsin

- 70% Ethanol with 1% HCl (decolorizer)

- 3% Methylene Blue (counterstain)

Procedure:

- Smear Preparation: Prepare a fecal smear, air-dry, and heat-fix.

- Primary Staining: Flood the slide with 3% Carbol Fuchsin for 15 minutes. Heat the slide gently for 5 minutes, then allow it to cool.

- Rinsing: Rinse the slide with tap water.

- Decolorization: Decolorize with 1% Acid-Alcohol for 1-2 minutes, then rinse with tap water.

- Counterstaining: Apply 3% Methylene Blue for 5 minutes. Rinse with tap water and air-dry.

- Examination: Examine under oil immersion. T. saginata eggs stain a consistent magenta-red and are oval, while T. solium eggs appear purplish-blue and are more spherical [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents used in the featured techniques, with their specific functions in the context of parasitological diagnostics.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Parasitological Microscopy

| Reagent Solution | Technical Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Formalin (5-10% Buffered) | Preservative that fixes and hardens parasitic structures, preventing degeneration and bacterial overgrowth [11]. | Primary fixative in formalin-ethyl acetate sedimentation; preservation of stool samples for long-term storage. |

| Ethyl Acetate | Organic solvent that extracts fats, lipids, and other debris from the fecal suspension, resulting in a cleaner sediment [11]. | Used in the formalin-ethyl acetate sedimentation technique to create a debris plug. |

| Zinc Sulfate Solution (sp. gr. 1.20) | High-specific-density flotation medium that allows buoyant parasitic forms to rise to the surface [10]. | Recovery of protozoan cysts and some helminth eggs in centrifugal-flotation. |

| Saturated Sodium Chloride Solution | Economical high-specific-density flotation medium. | Used in spontaneous flotation techniques and McMaster egg counting. |

| Carbol Fuchsin | Primary stain in acid-fast procedures; binds to mycolic acids in cell walls of acid-fast organisms [13] [14]. | Differentiating Taenia species [13] and staining coccidian oocysts [14]. |

| Malachite Green / Methylene Blue | Counterstain that provides background coloration, enhancing contrast for the primary stain [14]. | Used in modified acid-fast and Ziehl-Neelsen staining to visualize non-acid-fast elements. |

| Peanut Agglutinin (PNA-FITC) | Fluorescently labeled lectin that binds specifically to carbohydrate motifs on the surface of certain parasite eggs [12]. | Fluorescent microscopic identification and differentiation of Haemonchus contortus eggs. |

Workflow and Method Selection

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for selecting the appropriate microscopic technique based on research objectives and parasite characteristics.

The morphological identification of parasite eggs through manual microscopy remains a cornerstone in parasitology research and clinical diagnosis. As the gold standard for diagnosing intestinal parasitic infections, this technique is crucial for epidemiological studies, drug efficacy testing, and patient management [18] [19]. Despite its foundational role, manual microscopy suffers from significant limitations that impact the reliability and efficiency of research outcomes. These constraints are particularly relevant for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who require high levels of accuracy and reproducibility in their work.

This technical guide examines the core limitations of time consumption and human error in manual microscopic analysis of parasite eggs. It further explores how emerging technologies, particularly artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning, are being developed to address these challenges within the context of modern parasitology research. Understanding these limitations and potential solutions is essential for advancing morphological identification techniques and improving the quality of research outcomes in parasite studies.

Core Limitations of Manual Microscopy

Time Consumption and Throughput Constraints

The process of manual microscopy for parasite egg identification is inherently time-intensive, creating significant bottlenecks in research and diagnostic workflows. The following table quantifies the time-related constraints across different microscopic procedures:

Table 1: Time Consumption in Manual Microscopic Procedures

| Procedure Aspect | Time Requirement | Impact on Research |

|---|---|---|

| Complete sample examination | 8-10 minutes per sample [5] | Limits daily processing capacity; restricts sample size in studies |

| Manual sediment examination | Labor-intensive and time-consuming [20] | Reduces number of experiments feasible within project timelines |

| Centrifugation and preparation | 5 minutes at 1500 rpm (additional to examination) [20] | Increases hands-on researcher time per sample |

| Scanning multiple fields | Slow and fatiguing for operators [21] | Creates throughput bottlenecks in large-scale studies |

The cumulative effect of these time constraints significantly limits the scale and scope of parasitology research. Large-scale studies requiring examination of hundreds or thousands of samples become impractical, potentially leading to underpowered experiments or extended project timelines that delay critical findings in parasite biology and drug development.

Human Error and Diagnostic Variability

Human factors introduce substantial variability and error in parasite egg identification, potentially compromising research outcomes. The table below categorizes and describes common human errors in microscopic analysis:

Table 2: Categories and Impact of Human Errors in Microscopic Analysis

| Error Category | Description | Effect on Parasite Egg Identification |

|---|---|---|

| Observer Bias | Manual exposure settings, focus, and ROI selection vary between users [21] | Inconsistent identification of egg morphology between researchers |

| Fatigue-Related Errors | Decreased attention and decision-making ability due to prolonged eyepiece work [22] [23] | Missed detections (false negatives) during extended examination sessions |

| Omission Errors | Missing a step or skipping over elements in the visual field [22] | Failure to identify eggs present in samples, particularly at low concentrations |

| Commission Errors | Performing identification actions incorrectly [22] | Misclassification of parasite species based on morphological features |

| Procedural Errors | Not following established identification protocols [22] | Inconsistent application of diagnostic criteria across research teams |

The consequences of these errors are particularly pronounced in parasite egg identification due to several factors. The morphological similarity of different parasitic eggs and the abundance of impurities in samples create inherent challenges that require extensive training to overcome [5]. Furthermore, the relatively low sensitivity of manual microscopy, particularly at low parasite levels, can lead to false negatives that skew research data [18]. These limitations are compounded in resource-limited settings where access to highly trained microscopists may be restricted, potentially affecting the reliability of multi-center research trials [18].

Methodological Approaches to Address Limitations

Conventional Manual Microscopy Protocol

The standard protocol for manual microscopic examination of parasite eggs, as derived from established laboratory methods, involves multiple meticulous steps that contribute to both time consumption and potential error introduction [20]:

Sample Preparation Protocol

- Collection: Mid-stream samples (30 mL) are collected into appropriate primary containers

- Transport: Samples are transported in primary containers to prevent leakage or contamination

- Aliquoting: Samples are transferred to secondary translucent conical tubes (10 mL per tube)

- Centrifugation: First tube is centrifuged for 5 minutes at 1500 rpm (400 g)

- Sediment Preparation: Supernatant is decanted until 0.5 mL remains; sediment is resuspended

- Slide Preparation: One drop of sediment is placed on a microscope slide and covered with a cover slip

Microscopic Examination Protocol

- Slide Scanning: At least 10 different microscopic fields are scanned at magnifications of ×100 and ×400

- Element Identification: Formed elements are identified based on morphological characteristics

- Quantification: Results are calculated by averaging formed elements and reported as cells or particles per field

- Quality Control: Two independent evaluators (e.g., biochemistry specialist and biologist) examine the same slide; discrepancies trigger re-analysis with another sample

This multi-step process introduces numerous variables that affect reproducibility, including centrifugation speed and time, resuspension volume, staining techniques (if used), and individual interpretation of morphological features [20]. The requirement for independent verification by multiple specialists further increases the time investment while highlighting the inherent subjectivity of the method.

Emerging Automated and AI-Assisted Methodologies

Recent technological advances have introduced automated methodologies that address the limitations of manual microscopy through standardized, computational approaches:

Deep Learning-Based Detection Protocol [24] [5] [19]

- Image Acquisition: Sample slides are photographed via light microscope; low-cost USB microscopes (10×) or high-quality microscopes (1000×) may be used

- Data Preparation:

- Greyscale conversion and contrast enhancement to improve feature detection

- Image division into overlapping patches (e.g., 100×100 pixels) using sliding window approach

- Data augmentation through random flipping, rotation, and shifting to increase dataset size

- Model Training:

- Implementation of convolutional neural networks (CNN) such as YOLO variants, AlexNet, or ResNet50

- Transfer learning approach using pre-trained networks with fine-tuning on parasite egg datasets

- Dataset division into training, validation, and test sets (typical ratio: 8:1:1)

- Prediction and Analysis:

- Patch-by-patch classification of input images

- Probability mapping and reconstruction to identify egg locations

- Species classification based on learned morphological features

Table 3: Performance Comparison of AI Models for Parasite Egg Detection

| Model/Approach | Accuracy/Precision | Recall | mAP_0.5 | Computational Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YAC-Net (YOLO-based) | 97.8% [19] | 97.7% [19] | 0.9913 [19] | 1.9M parameters [19] |

| YOLOv4 (Multiple Species) | 84.85-100% (varies by species) [24] | Not specified | Not specified | Moderate to high [24] |

| Transfer Learning (AlexNet/ResNet50) | Improved over state-of-the-art [5] | Not specified | Not specified | Moderate [5] |

| Human Expert | High but variable | High but decreases with fatigue [23] | Not applicable | Not applicable |

The following diagram illustrates the comparative workflow between manual and AI-assisted approaches, highlighting points where time consumption and error typically occur:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementation of effective parasite egg identification protocols requires specific materials and computational resources. The following table details essential research reagents and solutions used in both conventional and advanced morphological identification methods:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Parasite Egg Morphological Identification

| Item | Function/Application | Implementation Context |

|---|---|---|

| Microscope Slides and Coverslips | Platform for preparing and examining samples | Standardized manual examination; AI-assisted imaging [20] [5] |

| Conical Tubes | Sample aliquoting and centrifugation | Sediment preparation for enhanced detection [20] |

| Staining Solutions | Enhancement of morphological features | Improved contrast for both human and AI-based identification [20] |

| Low-Cost USB Microscope | Digital image acquisition for automated systems | Resource-constrained settings; enables digital archiving [5] |

| High-Quality Microscope | High-resolution imaging for detailed morphology | Reference standard imaging; detailed morphological studies [5] |

| Deep Learning Models | Automated detection and classification | YOLO variants, CNN architectures for efficient analysis [24] [19] |

| Data Augmentation Algorithms | Expansion of training datasets | Improves model robustness with limited sample sizes [5] |

| Graphical Processing Units | Acceleration of model training and inference | Reduces computational time for AI-based approaches [24] |

The integration of these tools varies depending on the research context. While conventional manual microscopy relies primarily on physical laboratory equipment, AI-assisted approaches require both wet laboratory components and computational resources, creating a hybrid workflow that leverages the strengths of both traditional and technological methods.

Manual microscopy for parasite egg identification presents significant limitations in time efficiency and reliability that directly impact research quality and throughput in parasitology. The time-intensive nature of proper sample examination constrains study scale, while human factors introduce variability that threatens reproducibility. These challenges are particularly problematic in drug development research where consistent morphological assessment is crucial for evaluating treatment efficacy.

Emerging methodologies centered on deep learning and automation offer promising approaches to mitigate these limitations. Current research demonstrates that AI-assisted platforms can achieve high accuracy in parasite egg detection while reducing analysis time and minimizing human error. Nevertheless, the role of human expertise remains vital for system validation, complex case resolution, and quality control. The future of morphological identification in parasite research lies in hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both human expertise and computational consistency, potentially transforming how parasite egg analysis is conducted in research settings and accelerating progress in understanding and treating parasitic infections.

The morphological identification of parasite eggs remains a cornerstone of diagnostic parasitology, essential for accurate disease diagnosis and subsequent research and drug development. However, in many developed regions, the decline in parasitic infections due to improved sanitation has created a significant challenge: access to physical specimens for education and reference is becoming increasingly limited. This scarcity threatens the preservation of crucial morphological expertise among researchers and healthcare professionals. The construction of digital specimen databases presents a transformative solution to this problem, offering a sustainable, accessible, and scalable resource. By leveraging whole-slide imaging (WSI) technology, these databases create high-fidelity virtual slides of parasite specimens, ensuring that vital morphological knowledge is not only preserved but also enhanced for future research and educational endeavors. This technical guide explores the construction, implementation, and application of such databases, framed within the critical context of morphological identification research for parasite eggs.

The Construction of a Digital Parasite Specimen Database

Specimen Acquisition and Preparation

The foundational step in building a digital database is the curation of a diverse and well-characterized collection of physical specimens. In a pioneering initiative, researchers acquired 50 existing slide specimens of parasitic eggs, adult parasites, and arthropods from the collections of Kyoto University and the Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine [25] [26]. These specimens included parasite eggs, adult worms, ticks, insects typically observed under low magnification, and malarial parasites requiring high magnification. A critical preparatory step was verifying that all slide samples were devoid of personal information, thus ensuring their ethical use for educational and research purposes, including data sharing. Some specimens were historically prepared at the universities, while others were procured from commercial suppliers and museums, guaranteeing a taxonomically broad representation.

Digital Scanning and Image Processing

The process of digitizing physical slides requires specialized equipment and methodologies to ensure high-quality, diagnostically useful outputs. In the cited project, digital scanning was performed using the SLIDEVIEW VS200 slide scanner by EVIDENT Corporation [25]. A key technical consideration for thicker smear specimens was the application of the Z-stack function. This technique involves varying the scan depth during image capture to accumulate layer-by-layer data, thereby accommodating three-dimensional structures and ensuring all focal planes are accurately represented in the final digital image [25]. Each slide was scanned individually, with a quality control protocol in place: slides containing out-of-focus areas were rescanned as necessary, and the clearest image was selected for inclusion in the final database by the reviewing authors [25].

Database Architecture and Management

The final stage involves structuring the digitized data into an accessible and organized system. For the constructed database, the virtual slide data was uploaded to a shared server (Windows Server 2022) to build the searchable database [25]. The folder structure was logically organized according to the taxonomic classification of the organisms, facilitating intuitive navigation. To significantly enhance the educational and reference utility, each specimen was accompanied by simple explanatory text. Critically, these notes were provided in both English and Japanese, making the resource accessible to a wider international audience of researchers and professionals [25]. The shared server is configured to allow approximately 100 simultaneous users to access and observe the data via a standard web browser on various devices, including laptops, tablets, and smartphones, without requiring specialized viewing software [25].

Quantitative Analysis of Database Utility and Performance

The value of a digital database is demonstrated through its performance metrics and its impact on research and education. The table below summarizes key quantitative data from both the construction of a specimen database and a related automated detection model, highlighting the efficacy of digital approaches.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Digital Parasitology Resources

| Resource Type | Key Metric | Reported Value | Implication for Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Specimen Database [25] | Number of Slide Specimens Digitized | 50 specimens | Provides a foundational, scalable collection for morphological reference. |

| Digital Specimen Database [25] | Simultaneous User Access | ~100 users | Enables widespread use in classroom settings and multi-institutional research. |

| YCBAM Detection Model [27] | Precision | 0.9971 | Extremely low false positive rate, crucial for reliable automated diagnosis. |

| YCBAM Detection Model [27] | Recall | 0.9934 | Very low false negative rate, ensuring most parasite eggs are identified. |

| YCBAM Detection Model [27] | Mean Average Precision (mAP @0.50 IoU) | 0.9950 | Demonstrates superior overall detection and localization accuracy. |

The integration of digital databases with advanced deep learning models, such as the YOLO Convolutional Block Attention Module (YCBAM), creates a powerful synergy. While the database provides the essential high-quality data for training, models like YCBAM offer a path toward high-throughput, automated analysis. The YCBAM architecture, which integrates YOLO with self-attention mechanisms and a Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM), has demonstrated exceptional performance in automating the detection of pinworm eggs in microscopic images [27]. Its high precision and recall indicate that it can significantly reduce diagnostic errors and save time, supporting researchers and healthcare professionals in making informed decisions. This is particularly relevant for diagnosing parasites like pinworms (Enterobius vermicularis), whose eggs are small (50–60 μm in length and 20–30 μm in width) and can be morphologically similar to other microscopic particles [27].

Experimental Protocols for Digital Workflows

Protocol 1: Whole-Slide Imaging for Database Construction

This protocol details the methodology for creating virtual slides for a digital specimen database [25].

- Step 1: Specimen Curation. Identify and select existing slide specimens from institutional collections, ensuring a representative range of taxa (e.g., parasite eggs, adults, arthropods). Verify that specimens are free of personal identifying information.

- Step 2: Scanner Calibration. Calibrate a whole-slide imaging scanner (e.g., SLIDEVIEW VS200) according to manufacturer specifications to ensure color fidelity and focus accuracy.

- Step 3: Scanning and Z-Stack Acquisition. For each slide, select the appropriate magnification (e.g., 40x for eggs/adults, 1000x for blood parasites). For specimens with thicker smears, activate the Z-stack function to capture multiple focal planes and accumulate layer-by-layer data.

- Step 4: Image Quality Control. Visually review each digitized slide for focus and clarity. Rescan any slides with out-of-focus areas. Authors or qualified personnel should select the clearest image for final inclusion.

- Step 5: Data Upload and Annotation. Upload the final virtual slide images to a dedicated shared server. Organize the files into a logical folder structure based on taxonomy. Attach explanatory notes for each specimen to facilitate learning and reference.

Protocol 2: Automated Detection of Parasite Eggs Using YCBAM

This protocol outlines the workflow for developing a deep learning model to automatically detect parasite eggs in digital microscopic images [27].

- Step 1: Dataset Preparation. Compile a dataset of microscopic images of parasite eggs, such as pinworm eggs. Annotate the images by labeling the bounding boxes of each egg. A typical dataset might include 255 images for segmentation tasks.

- Step 2: Model Architecture Integration. Implement the YCBAM architecture by integrating the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) and self-attention mechanisms into a YOLOv8 framework. This enhances feature extraction from complex backgrounds.

- Step 3: Model Training. Train the YCBAM model on the annotated dataset. Use a suitable loss function (e.g., box loss) and monitor its convergence during training. The reported training box loss for a pinworm model was 1.1410, indicating efficient learning [27].

- Step 4: Model Evaluation. Evaluate the trained model's performance on a separate test set. Calculate key metrics including Precision, Recall, and mean Average Precision (mAP) at an Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.50 to confirm detection accuracy.

- Step 5: Inference and Deployment. Deploy the trained model to analyze new microscopic images. The model will output precise identifications and localizations of parasite eggs, offering a tool to reduce diagnostic time and human error.

Visualization of Workflows and System Architecture

The following diagrams, created using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the core workflows and logical relationships described in this guide. The color palette and contrast have been designed to meet WCAG 2.1 AA accessibility standards, ensuring readability for all users [28] [29] [30].

Diagram 1: Digital Specimen Database Construction Workflow

Diagram 2: Automated Detection Model Development Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The development and utilization of digital specimen databases and associated analytical models rely on a suite of essential tools and reagents. The following table details key components of this research toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Digital Parasitology

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Example | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Whole-Slide Imaging Scanner | SLIDEVIEW VS200 (EVIDENT Corp) [25] | High-resolution digitization of physical microscope slides to create virtual specimens. |

| Computational Framework | YOLOv8 [27] | A real-time object detection system that forms the backbone for automated parasite egg identification models. |

| Attention Module | Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) [27] | A neural network component integrated into models like YCBAM to enhance feature extraction from complex image backgrounds. |

| Digital Storage & Server | Windows Server 2022 [25] | Hosts the digital database, enabling secure, multi-user access and data management for collaborative research. |

| Analysis & Statistical Software | R / RStudio [31] | An open-source environment for statistical computing and graphics, used for analyzing experimental data and model performance. |

| Color Contrast Analyzer | Colour Contrast Analyser (CCA) [28] [30] | Ensures that all visualizations and user interfaces meet accessibility standards (WCAG) for inclusive science. |

The construction and implementation of digital specimen databases represent a critical advancement in the field of parasitology, directly supporting the morphological identification research essential for diagnostics and drug development. By preserving rare specimens in an accessible, non-degrading digital format, these databases act as a bulwark against the loss of morphological expertise. Furthermore, when these rich data sources are coupled with state-of-the-art deep learning models, they empower a new paradigm of high-throughput, accurate, and automated analysis. For researchers and scientists dedicated to combating parasitic diseases, the integration of digital databases and computational tools is no longer a luxury but a fundamental component of a modern, effective research toolkit.

Challenges in Low-Prevalence Settings and Resource-Limited Environments

The morphological identification of parasite eggs remains a cornerstone of parasitology research and clinical diagnosis. However, the reliability of this method faces significant challenges in low-prevalence settings and resource-limited environments. In these contexts, the diminishing expertise of microscopists, combined with economic constraints that limit access to advanced diagnostic tools, creates a perfect storm that compromises diagnostic accuracy and impedes effective parasite control [32] [33]. Although traditional microscopy is considered the gold standard for parasite detection, its sensitivity and specificity are not fixed attributes but are influenced by disease prevalence and the resources available for expert training [34]. This technical guide examines these challenges through an evidence-based lens and explores innovative solutions that combine optimized laboratory protocols with emerging artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to enhance diagnostic capabilities in these critical settings.

Technical Challenges in Low-Prevalence and Resource-Limited Settings

The Impact of Disease Prevalence on Test Performance

The fundamental assumption that sensitivity and specificity are intrinsic test properties remains valid only under ideal conditions. A comprehensive meta-epidemiological study analyzing 6,909 diagnostic test accuracy studies revealed a significant association between disease prevalence and these metrics. As prevalence increases, sensitivity tends to increase while specificity decreases [34]. This relationship poses particular challenges for morphological identification in low-prevalence settings, where the pre-test probability of infection is low, and the positive predictive value of tests diminishes accordingly. For parasitic diseases, this means that even highly specific morphological identification methods may yield more false positives when deployed in low-prevalence settings, potentially leading to unnecessary treatments and misallocation of limited resources.

Economic and Expertise Constraints

Resource-limited environments face compounded challenges that extend beyond test performance characteristics:

- Expertise Dilution: The diagnostic accuracy of manual microscopy is highly dependent on technician expertise and experience [33]. In low-prevalence settings, microscopists have limited opportunities to maintain their skills through regular practice, leading to decreased proficiency over time.

- Infrastructure Limitations: Many resource-constrained laboratories lack reliable electricity, quality microscopes, and appropriate storage facilities for reagents and samples, further compromising diagnostic accuracy [32].

- Time Constraints: Traditional microscopic examination is labor-intensive, requiring approximately 30 minutes per sample [35]. In high-volume settings with limited personnel, this often leads to rushed examinations and increased error rates.

Established and Emerging Solutions

Optimized Manual Protocols for Enhanced Egg Recovery

For researchers working with insect vectors or environmental samples, standardized protocols for parasite egg recovery are essential. Recent research has developed and validated efficient methods for recovering Taenia saginata and Ascaris suum eggs from house flies, which can be adapted for field use [36].

Table 1: Optimized Protocols for Parasite Egg Recovery from Insect Vectors

| Sample Source | Protocol Steps | Recovery Rate | Hands-on Time | Total Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal Tract | Homogenization in PBS + Centrifugation (2000 g, 2 min) | 79.7% (T. saginata), 74.2% (A. suum) | 1.5 minutes | 6.5 minutes |

| Exoskeleton | Vortexing (2 min) in Tween 80 + Passive Sedimentation (15 min) + Centrifugation (2000 g, 2 min) | 77.4% (T. saginata), 91.5% (A. suum) | 3.5 minutes | 20.5 minutes |

These protocols demonstrate that effective parasite egg recovery can be achieved with minimal hands-on time and basic laboratory equipment, making them particularly suitable for resource-constrained settings. The centrifugation-based method for gastrointestinal tract samples effectively removes large debris particles that could hinder the differentiation of eggs from other material, while the washing and sedimentation approach for exoskeletons successfully isolates eggs with minimal contamination [36].

AI-Assisted Diagnostic Platforms

Deep learning approaches, particularly YOLO-based models, have emerged as powerful tools for automating parasite egg identification, potentially overcoming the expertise gap in low-prevalence settings.

Table 2: Performance of AI Models for Parasite Egg Detection

| Model | Parasite Species | Performance Metrics | Detection Speed | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv5 | Multiple intestinal parasites | mAP: ~97% | 8.5 ms/sample | [35] |

| YOLOv4 | Clonorchis sinensis, Schistosoma japonicum | Accuracy: 100% | Real-time efficiency | [33] |

| YOLOv4 | E. vermicularis, F. buski, T. trichiura | Accuracy: 89.31%, 88.00%, 84.85% | Real-time efficiency | [33] |

| YCBAM | Pinworm parasite eggs | Precision: 0.9971, Recall: 0.9934, mAP: 0.9950 | Efficient training convergence | [27] |

The YCBAM architecture, which integrates YOLO with self-attention mechanisms and Convolutional Block Attention Module, has demonstrated particular effectiveness in challenging imaging conditions by focusing on spatial and channel-wise information to improve feature extraction from complex backgrounds [27]. This approach significantly enhances the detection of small, critical features such as pinworm egg boundaries, which measure only 50-60 μm in length and 20-30 μm in width [27].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sample Preparation for Morphological Studies

Standardized sample preparation is crucial for both traditional microscopy and AI-assisted identification:

- Sample Collection: Collect fresh stool samples or parasite egg suspensions from reliable sources [33].

- Slide Preparation: Place two drops of vortex-mixed egg suspension (approximately 10 μL) on a slide and cover with an 18×18 mm coverslip, avoiding air bubbles [33].

- Microscopic Confirmation: Confirm egg species and integrity under a light microscope before proceeding with analysis [36].

- Image Acquisition: Capture images using standardized microscopy equipment. For bright-field imaging, use a ring-shaped LED cold light source positioned 10 cm above the sample [37].

AI Model Training and Implementation

For researchers implementing AI-assisted detection, the following methodology has proven effective:

Data Set Preparation:

Model Training:

- Utilize Python 3.8 with PyTorch framework on GPU-enabled systems [33].

- Set initial learning rate to 0.01 with decay factor of 0.0005 [33].

- Use Adam optimizer with momentum of 0.937 and batch size of 64 [33].

- Train for 300 epochs, freezing backbone feature extraction network for first 50 epochs [33].

Performance Evaluation:

Figure 1: AI-Assisted Parasite Egg Detection Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Parasite Egg Identification Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline | 1X concentration, pH 7.4 | Egg homogenization and washing | Maintains osmotic balance; used in gastrointestinal tract recovery [36] |

| Tween 80 | 0.05% concentration | Surfactant for exoskeleton washing | Reduces surface tension without damaging egg morphology [36] |

| Microscopy Slides | Standard 75x25 mm, 1.0-1.2 mm thickness | Sample mounting for visualization | Pre-cleaned slides reduce artifacts [33] |

| Coverslips | 18x18 mm square | Creating uniform sample thickness | Minimizes air bubbles during preparation [33] |

| Gaussian Blur Filter | Sigma = 2 | Image processing for noise reduction | Improves feature detection in automated systems [37] |

| FastRandomForest Classifier | 1000 trees, depth 15 | Pixel classification in image analysis | Effective for distinguishing eggs from debris [37] |

Integrated Workflow for Chall Environments

Figure 2: Integrated Approach to Address Diagnostic Challenges

The most promising solution for low-prevalence and resource-limited settings involves integrating optimized manual protocols with AI-assisted platforms. This hybrid approach leverages the efficiency of standardized sample processing methods with the analytical power of deep learning algorithms, creating a diagnostic system that maintains accuracy despite limited resources and expertise.

The challenges of morphological identification of parasite eggs in low-prevalence and resource-limited environments are significant but not insurmountable. Through the implementation of optimized recovery protocols, standardized sample processing methods, and the integration of AI-assisted detection platforms, researchers and healthcare providers can maintain diagnostic accuracy despite constraints. The continued refinement of these approaches, particularly through the expansion of training datasets and adaptation to field conditions, holds promise for transforming parasitic disease diagnosis in the most challenging settings. As these technologies become more accessible and validated across diverse environments, they have the potential to bridge the diagnostic gap that currently impedes effective parasite control in resource-limited regions worldwide.

Advanced Methodologies: AI, Deep Learning and Automated Detection Systems

The morphological identification of parasite eggs represents a critical procedure in medical diagnostics and biological research. Conventional manual microscopic examination is time-consuming, labor-intensive, and susceptible to human error, particularly in resource-constrained settings. Deep learning architectures have emerged as transformative solutions, automating detection with remarkable precision and speed. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of state-of-the-art deep learning frameworks—primarily YOLO (You Only Look Once) variants and specialized Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)—for egg detection, with specific application to the morphological identification of parasite eggs. The content is structured to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with comprehensive methodological protocols, performance benchmarks, and implementation frameworks to advance research in parasitology and related fields.

Core Deep Learning Architectures for Egg Detection

YOLO-Based Architectures

The YOLO family of one-stage detectors has been extensively adapted for egg detection due to its optimal balance between speed and accuracy. Recent research has focused on enhancing standard YOLO architectures to address the specific challenges of egg morphology, such as small size, occlusion, and morphological similarities between species.

YOLO with Attention Mechanisms (YCBAM): A novel framework integrates the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) with YOLO to create YCBAM. This architecture leverages self-attention mechanisms to focus computational resources on salient image regions containing parasitic elements, significantly improving detection in challenging imaging conditions. The attention modules enhance feature extraction from complex backgrounds and increase sensitivity to critical small features like pinworm egg boundaries. Experimental evaluation demonstrated a precision of 0.9971, recall of 0.9934, and mean Average Precision (mAP) of 0.9950 at an IoU threshold of 0.50, confirming superior detection performance for pinworm eggs [27].

Lightweight YOLO Variants (YAC-Net): For deployment in resource-constrained environments, researchers have developed lightweight models. YAC-Net modifies YOLOv5n by replacing the feature pyramid network (FPN) with an asymptotic feature pyramid network (AFPN) and integrating a C2f module to enrich gradient flow. This architecture fully fuses spatial contextual information through hierarchical and asymptotic aggregation, with adaptive spatial fusion selecting beneficial features while ignoring redundant information. The model achieved a precision of 97.8%, recall of 97.7%, and mAP_0.5 of 0.9913 while reducing parameters by one-fifth compared to its baseline, making it suitable for automated detection systems with limited computational resources [19].

Comparative Performance Analysis: A comprehensive evaluation of compact YOLO variants (YOLOv5n, YOLOv5s, YOLOv7, YOLOv7-tiny, YOLOv8n, YOLOv8s, YOLOv10n, and YOLOv10s) for recognizing 11 parasite species eggs revealed that YOLOv7-tiny achieved the highest mAP of 98.7%, while YOLOv10n yielded the highest recall and F1-score of 100% and 98.6%, respectively. YOLOv8n achieved the fastest processing speed at 55 frames per second on a Jetson Nano, highlighting the critical trade-offs between accuracy, recall, and inference speed for practical deployments [38].

CNN and Hybrid Architectures

Beyond YOLO, researchers have developed specialized CNN architectures and hybrid models that leverage recent advances in deep learning for parasitic egg recognition.

Convolution and Attention Network (CoAtNet): This architecture combines the strengths of convolution and self-attention mechanisms. The model leverages the convolutional layers' spatial feature extraction capabilities while utilizing the attention mechanisms' global contextual understanding. When evaluated on the Chula-ParasiteEgg dataset containing 11,000 microscopic images, CoAtNet achieved an average accuracy of 93% and an average F1-score of 93%, demonstrating robust performance across multiple parasitic egg categories [4].

Morphological Regulated Variational Autoencoder (Morpho-VAE): For landmark-free morphological analysis, Morpho-VAE combines unsupervised and supervised learning to extract discriminative shape features. The architecture integrates a variational autoencoder with a classifier module, regulated by a hyperparameter α that balances reconstruction fidelity with classification performance. When applied to mandible shape analysis, the method achieved superior cluster separation compared to PCA and standard VAE, with potential application to parasitic egg morphology quantification [39].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Deep Learning Architectures for Egg Detection

| Architecture | Base Model | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | mAP@0.5 (%) | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YCBAM [27] | YOLOv8 | 99.71 | 99.34 | 99.50 | Integrated CBAM attention module |

| YAC-Net [19] | YOLOv5n | 97.80 | 97.70 | 99.13 | AFPN and C2f modules for lightweight design |

| YOLOv7-tiny [38] | YOLOv7-tiny | - | - | 98.70 | Optimal balance of accuracy and efficiency |

| CoAtNet [4] | Custom | 93.00 | 93.00 | - | Hybrid convolution-attention mechanism |

| YOLOv4 [33] | YOLOv4 | 100.00* | - | - | Transfer learning for specific parasite eggs |

| YOLO-Goose [40] | YOLOv8s | - | - | 96.40 | Small-object detection layer for animal eggs |

*For specific species (Clonorchis sinensis and Schistosoma japonicum)

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Dataset Preparation and Preprocessing

The accuracy of deep learning models heavily depends on dataset quality and preprocessing techniques. Standardized protocols have emerged across studies for parasitic egg imaging.

Sample Collection and Imaging: Parasitic egg suspensions are obtained from biological suppliers or clinical samples. For microscopic imaging, two drops of vortex-mixed egg suspension (approximately 10μL) are placed on a slide and covered with an 18mm × 18mm coverslip, avoiding air bubbles. Imaging is performed using light microscopes (e.g., Nikon E100) at consistent magnification levels. For non-parasitic egg detection in agricultural settings, images may be captured using drones (e.g., DJI Phantom 4 Pro) or handheld devices in field conditions [33].

Data Preprocessing and Augmentation: Images are typically resized to standard dimensions (e.g., 640×640 pixels for YOLO models). To enhance model robustness, data augmentation techniques are extensively employed, including:

- Rotation and mirroring for orientation invariance

- Gaussian noise and salt-and-pepper noise injection for robustness to image quality variations

- Color space adjustments for illumination invariance

- Mosaic data augmentation and mixup for improved background contextualization [33] [41]

Cropping techniques using sliding window approaches are implemented to generate multiple training samples from single high-resolution images, particularly beneficial for small object detection [33].

Dataset Partitioning: Datasets are typically partitioned into training, validation, and test sets with ratios of 8:1:1. The training set builds model weights, the validation set guides hyperparameter tuning, and the test set provides unbiased performance evaluation [33].

Model Training Protocols

Consistent training protocols ensure reproducible model performance across different experimental setups.

Parameter Configuration: For YOLO models, standard training configurations include:

- Initial learning rate: 0.01 with decay factor of 0.0005

- Optimizer: Adam with momentum value of 0.937

- Batch size: 64

- Training epochs: 300 with early stopping if no improvement after 200 epochs

- Anchor sizes: Determined using k-means clustering on training data [33]

Implementation Frameworks: Models are typically implemented in Python using PyTorch or TensorFlow frameworks, trained on NVIDIA GPUs (e.g., RTX 3090), and optimized for deployment on edge devices like Raspberry Pi, Intel upSquared with Neural Compute Stick 2, and Jetson Nano for field applications [38].

Loss Functions: Traditional YOLO loss functions combine bounding box regression, objectness, and classification losses. Enhanced versions incorporate GIoU (Generalized Intersection over Union) loss to improve bounding box accuracy for small objects like eggs [40].

Architectural Diagrams and Workflows

YCBAM Architecture Workflow

Diagram Title: YCBAM Architecture with Dual Attention Paths

End-to-End Parasitic Egg Detection Pipeline

Diagram Title: End-to-End Parasitic Egg Detection System

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Parasitic Egg Detection Studies

| Item | Specification/Example | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Parasitic Egg Suspensions | Commercially sourced (e.g., Deren Scientific Equipment Co.) | Provide standardized biological samples for model training and validation |

| Microscopy Slides and Coverslips | Standard glass slides (18mm × 18mm coverslips) | Sample preparation for microscopic imaging |

| Light Microscope | Nikon E100 with digital camera attachment | High-quality image acquisition of parasitic eggs |

| Computational Hardware | NVIDIA GPUs (e.g., RTX 3090), Jetson Nano for deployment | Model training and inference acceleration |

| Annotation Software | LabelImg, VGG Image Annotator | Bounding box annotation for training data preparation |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow with YOLO implementations | Model development and training infrastructure |

| Data Augmentation Tools | Albumentations, OpenCV | Dataset expansion and preprocessing |

| Edge Deployment Platforms | Raspberry Pi 4, Intel upSquared with NCS2 | Field-deployable inference systems for point-of-care diagnosis |

Performance Optimization Strategies

Lightweight Model Design

Model efficiency is crucial for deployment in resource-limited settings where parasitic infections are most prevalent. Effective strategies include:

Neural Architecture Compression: The integration of GhostNet as a backbone network reduces parameter count by 67.2% while maintaining detection accuracy. This approach replaces standard convolutional layers with ghost modules that generate more feature maps using cheap linear operations [40].

Neck Optimization: The implementation of Slim-neck structures using generalized efficient layer aggregation networks (GELAN) optimizes feature processing efficiency while reducing computational complexity. This design maintains high accuracy while decreasing inference time, essential for real-time applications [41].

Enhanced Feature Extraction

Advanced feature extraction techniques significantly improve small egg detection performance:

Omni-Dimensional Dynamic Convolution (ODConv): This approach employs a dynamic multi-dimensional attention mechanism to learn complementary attention across all four dimensions of the convolution kernel space (spatial, channel, kernel size, and number of filters). This enhances the model's ability to extract discriminative features from egg images with high morphological variation [41].

Receptive-Field Attention Head (RFAHead): Combining spatial attention with receptive-field features provides a more efficient mechanism for convolutional neural networks to extract and process image features. This specialized detection head improves performance for small and occluded targets common in parasitic egg microscopy [41].

Deep learning architectures, particularly enhanced YOLO variants and specialized CNNs, have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in automating the morphological identification of parasite eggs. The integration of attention mechanisms, lightweight design principles, and optimized feature extraction modules has addressed key challenges in egg detection, including small size, morphological similarity, and complex backgrounds. These technical advances provide researchers and clinicians with powerful tools for accurate, efficient parasite egg detection, with significant implications for diagnostic accuracy, epidemiological studies, and drug development initiatives targeting parasitic infections. Future research directions include multi-modal fusion of morphological and molecular data, self-supervised learning to reduce annotation burden, and federated learning approaches to enable collaborative model development while preserving data privacy across healthcare institutions.

The morphological identification of parasite eggs remains a cornerstone in the diagnosis of parasitic infections, which affect billions of people worldwide [33]. Conventional diagnosis relies on manual microscopic examination of stool samples, a process that is time-consuming, labor-intensive, and heavily dependent on the expertise of the examiner [42] [4]. These limitations can lead to diagnostic delays and errors, particularly in resource-constrained settings with high parasitic disease burdens. Consequently, the development of automated, accurate, and efficient diagnostic systems represents a critical research objective within the field of parasitology.

Recent advancements in artificial intelligence, particularly deep learning, have ushered in a new era for automated parasite egg detection and classification. Among these innovations, attention mechanisms have emerged as a powerful tool to enhance the capabilities of convolutional neural networks (CNNs). This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of two pivotal attention architectures—the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) and Self-Attention modules—within the context of parasitology research. It details their integration into state-of-the-art detection frameworks, presents quantitative performance comparisons, and outlines standardized experimental protocols for their implementation, thereby offering a comprehensive resource for researchers and developers in the field.

Technical Foundations of Attention Mechanisms

Attention mechanisms in deep learning are inspired by the human cognitive ability to focus selectively on salient parts of information while ignoring less relevant details. In computer vision, these mechanisms enable neural networks to prioritize informative regions and feature channels within an image, a capability particularly beneficial for analyzing complex microscopic images containing parasite eggs.

Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM)

CBAM is a lightweight, sequential attention module that enhances feature representations along both spatial and channel dimensions [27] [43]. It operates by sequentially inferring a 1D channel attention map and a 2D spatial attention map, which are then multiplied with the input feature map to adaptively refine features.

The channel attention branch focuses on "what" is meaningful in an input image. It uses both max-pooling and average-pooling operations to aggregate spatial information, generating two different spatial context descriptors. These descriptors are then fed into a shared multi-layer perceptron (MLP) to produce the channel attention map. The spatial attention branch, complementarily, focuses on "where" the informative regions are located. It computes a spatial attention map by utilizing the inter-spatial relationship of features. The channel-refined feature map is used as input, and two pooling operations (average-pooling and max-pooling) are applied along the channel axis to generate efficient feature descriptors. These are concatenated and convolved by a standard convolution layer to produce the final spatial attention map.

Self-Attention Mechanisms

Self-attention, also known as intra-attention, calculates the response at a position in a sequence by attending to all other positions and computing their weighted average. In vision tasks, it allows the model to capture long-range dependencies and global contextual information that may be challenging for standard convolutional layers with limited receptive fields. When applied to parasite egg images, self-attention mechanisms can model relationships between distant image regions, helping to identify eggs based on global morphological characteristics and their contextual surroundings [27] [43].

Integration Architectures for Parasite Detection

YCBAM: YOLO with CBAM for Pinworm Detection

The YCBAM framework represents a significant architectural innovation that integrates CBAM with the YOLOv8 object detection model to enhance pinworm egg detection [27] [44] [43]. The integration occurs at multiple strategic points within the network to strengthen feature representation.

- Architecture: The YCBAM model incorporates self-attention mechanisms and CBAM into the YOLOv8 backbone and neck. The self-attention modules are placed in the later stages of the backbone to capture global dependencies in high-level features. CBAM modules are inserted at key locations throughout the network to sequentially refine features along channel and spatial dimensions.

- Functionality: The self-attention mechanism enables the model to focus on relevant image regions while suppressing background noise, which is particularly valuable for detecting small, transparent pinworm eggs (measuring 50-60 μm in length and 20-30 μm in width) in complex microscopic backgrounds. The CBAM components enhance the model's sensitivity to discriminative features of parasite eggs, such as their characteristic shape and boundaries, by emphasizing meaningful feature channels and spatial regions.

- Performance: Experimental evaluations demonstrated that this integration achieved a precision of 0.9971 and recall of 0.9934 on pinworm egg detection, with a mean Average Precision (mAP@0.5) of 0.9950 [27].

Self-Attention with ResNeSt for Plasmodium Detection

Another effective implementation combines self-supervised learning with attention mechanisms for malaria parasite (plasmodium) detection [42]. This approach addresses the challenge of limited labeled data, which is common in medical imaging.

- Architecture: The model uses a ResNeSt backbone (which itself incorporates split-attention mechanisms) enhanced with additional spatial and channel attention modules. A critical innovation is the application of self-supervised learning for pre-training, where the model learns representative features from unlabeled data by predicting masked regions of cells in positive samples.

- Functionality: During pre-training, the network learns to reconstruct masked areas of parasite images, forcing it to develop a robust understanding of plasmodium morphology without requiring extensive labeled datasets. The attention modules then help the trained network focus on the most discriminative features during the fine-tuning stage with labeled data, particularly important for detecting tiny defect areas in plasmodium images where the parasite occupies only a small portion of the cell.

- Performance: This combined approach achieved a test accuracy of 97.8%, with 96.5% sensitivity and 98.9% specificity for plasmodium detection [42].

The workflow below illustrates the integration of attention mechanisms into parasite detection pipelines, from image preparation to final identification.

Performance Metrics and Comparative Analysis

The integration of attention mechanisms has yielded substantial improvements in the accuracy and efficiency of parasite egg detection systems. The table below summarizes quantitative performance metrics reported in recent studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Attention-Enhanced Models in Parasitology

| Model | Application | Precision | Recall | mAP@0.5 | Accuracy | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YCBAM [27] [43] | Pinworm egg detection | 99.7% | 99.3% | 99.5% | - | YOLOv8 + CBAM + Self-Attention |

| ResNeSt + Attention [42] | Plasmodium detection | - | - | - | 97.8% | Self-supervised pre-training + Attention |

| CoAtNet [4] | General parasitic eggs | - | - | - | 93.0% | Convolution + Attention Network |

| YOLO-PAM [45] | Malaria parasite detection | - | - | 83.6% | - | Transformer-based attention in YOLO |

These results demonstrate that attention mechanisms consistently enhance baseline models. The YCBAM architecture achieves particularly high precision and recall, highlighting its effectiveness for precise localization and identification of parasitic elements in challenging imaging conditions. The self-attention and CBAM components enable the model to maintain high sensitivity while minimizing false positives, even with small target objects like pinworm eggs.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Dataset Preparation and Preprocessing

Standardized dataset preparation is crucial for training robust attention-based detection models. The following protocol outlines key steps based on established methodologies in the field:

- Image Acquisition: Collect microscopic images of stool samples using a digital camera mounted on a light microscope. For pinworm detection, images should be obtained at 100-400x magnification [27] [43]. For plasmodium detection, use thin blood smear slides stained with Giemsa stain [42].

- Data Annotation: Annotate images using bounding boxes around parasite eggs. For multi-species detection, assign class labels to each annotation (e.g., A. lumbricoides, T. trichiura, E. vermicularis) [33]. Engage multiple domain experts (e.g., parasitologists with >10 years of experience) to ensure annotation accuracy and resolve disagreements through consensus [42].

- Dataset Splitting: Divide the annotated dataset into training, validation, and test sets using an approximate ratio of 8:1:1 [33]. Ensure that images from the same patient are contained within a single split to prevent data leakage.

- Data Augmentation: Apply extensive augmentation techniques to improve model generalization:

Model Training Protocol

The training process for attention-enhanced detection models follows this standardized protocol:

- Implementation Setup: Implement models using Python and deep learning frameworks such as PyTorch or TensorFlow. For YOLO-based models, utilize the appropriate official repository as a codebase [33].