Advanced FEA Methods for Modeling Difficult Stool Consistencies in Biomechanical Research

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for applying Finite Element Analysis (FEA) to model complex stool consistencies and their interaction with biological systems.

Advanced FEA Methods for Modeling Difficult Stool Consistencies in Biomechanical Research

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for applying Finite Element Analysis (FEA) to model complex stool consistencies and their interaction with biological systems. It covers foundational biomechanics, advanced methodological protocols for model creation, troubleshooting for convergence and accuracy, and rigorous validation techniques. By synthesizing current research and best practices, this guide aims to enhance the predictive power of computational models in gastrointestinal drug development, pelvic floor rehabilitation, and the design of medical devices for bowel management.

Understanding Stool Biomechanics and the Role of FEA

Stool consistency is a critical parameter in gastrointestinal research, serving as a key indicator of digestive health, intestinal transit time, and the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions. For researchers and drug development professionals, accurately defining and measuring this property is essential for studies on functional bowel disorders, novel drug formulations, and advanced biomechanical modeling. The assessment landscape spans from simple visual classification tools to sophisticated quantitative rheological methods, each with distinct applications in experimental and clinical settings. This technical support center provides targeted guidance on navigating these methodologies, with particular emphasis on their application in Finite Element Analysis (FEA) research involving difficult stool consistencies.

Core Classification System: The Bristol Stool Form Scale

The Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS) is a diagnostic medical tool developed in 1997 by Dr. Kenneth Heaton at the Bristol Royal Infirmary to classify human feces into seven distinct categories based on their physical appearance [1] [2]. This scale serves as a validated visual assessment method that correlates with intestinal transit time and has become the standard classification system in both clinical practice and research environments [1] [3]. Researchers and clinicians utilize the BSFS as a non-invasive, rapid assessment tool for evaluating bowel function, diagnosing conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and constipation, and monitoring treatment outcomes in pharmaceutical development [1] [2].

The BSFS categorizes stools from Type 1 (separate hard lumps) to Type 7 (watery, no solid pieces), with Types 3 and 4 generally considered ideal as they indicate normal transit time and are easy to pass without straining [1] [4]. Types 1 and 2 indicate constipation (slow transit), while Types 5-7 suggest diarrhea or rapid intestinal transit [3] [4]. The scale provides researchers with a common vocabulary for characterizing stool consistency across studies and has been validated in multiple languages, including Spanish, Brazilian Portuguese, and Polish, enhancing its utility in international research collaborations [2].

Technical Limitations in Research Applications

Despite its widespread adoption, the BSFS presents significant limitations for precise scientific research, particularly in studies requiring quantitative measurements for FEA modeling. The primary constraint is its subjective nature, which introduces inter-rater and intra-rater variability that can compromise data reliability [5]. One study demonstrated that the correlation between BSFS scores and objectively measured stool consistency was significantly stronger when scores were assigned by experts (rrm = -0.789) compared to subject self-assessment (rrm = -0.587), highlighting the potential for subjective bias [5].

Additionally, the BSFS exhibits limited granularity, as it categorizes stools into only seven broad types despite the continuous spectrum of stool consistency found in biological systems [5]. This lack of resolution becomes particularly problematic when researching "difficult consistencies" - extremely hard (Type 1) or watery (Type 7) stools that present challenges for both patients and experimental protocols. Furthermore, the scale provides no direct quantitative data on mechanical properties essential for FEA, such as compressive yield stress, viscosity, or solids diffusivity [5] [6]. These limitations have driven the development of complementary quantitative measurement technologies that can provide the precise, continuous data required for advanced computational modeling.

Quantitative Measurement Techniques

Texture Analysis for Direct Mechanical Measurement

Texture analyzers represent a significant advancement in objective stool consistency measurement, providing direct mechanical quantification that surpasses the limitations of visual scales. These instruments measure the force required to deform a stool sample under controlled conditions, generating continuous numerical data suitable for statistical analysis and modeling applications [5].

Table 1: Texture Analysis Protocol for Stool Consistency Measurement

| Parameter | Specification | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Instrument | TA.XTExpress Texture Analyser (Stable Micro Systems Ltd.) | Compatible with various penetrometer probes |

| Probe Type | Cylindrical (ø 6 mm) | Optimal for minimal sample disturbance |

| Probe Speed | 2.0 mm/s | Controlled penetration rate |

| Penetration Depth | 5 mm | Standardized measurement depth |

| Measured Value | Gram-force required for penetration | Direct indicator of mechanical resistance |

| Sample Storage | Refrigeration at 4°C if not measured immediately | Preserves original consistency properties |

| Measurement Environment | Room temperature (20-25°C) | Standardized testing conditions |

The protocol developed for the TA.XTExpress Texture Analyser demonstrates a strong negative correlation with stool water content (rrm = -0.781), validating its accuracy as a direct measurement tool [5]. This method can detect consistency variations across the entire clinical range, from hard constipated stools to watery diarrhea, with sensitivity superior to visual assessment alone. The log-transformed stool consistency values obtained from this method show normal distribution, making them suitable for parametric statistical analysis in research settings [5].

Rheological Characterization for FEA Modeling

Rheological measurements provide essential parameters for FEA simulations of stool movement through the digestive system and during defecation. These techniques characterize the flow and deformation behavior of stool under various stress conditions, generating data critical for accurate biomechanical modeling [6].

Research on the compressional rheology of fresh feces has identified key parameters that influence dewatering behavior and mechanical properties. The gel point (φg), which represents the solids concentration where the material develops a networked structure, ranges between 6.3 and 15.6% total solids (TS) concentration for fresh feces [6]. This is significantly higher than the gel point observed for wastewater sludge, indicating that passive gravity-driven processes can effectively thicken fresh fecal material - a finding with implications for both sanitation technology and understanding physiological water absorption in the colon.

Table 2: Key Rheological Parameters of Fresh Feces for FEA Modeling

| Parameter | Value Range | Significance for FEA |

|---|---|---|

| Gel Point (φg) | 6.3-15.6% TS | Defines transition from fluid-like to solid-like mechanical behavior |

| Passive Sedimentation Rate | 3 to 10% TS in <0.5 h | Important for modeling liquid separation processes |

| Filtration Characterization | Lengthy cake filtration times with short compression times | Informs on dewatering kinetics and resistance to flow |

| Effect of Conductivity | Increased conductivity hinders dewatering rate | Models impact of ionic composition on mechanical properties |

| Compressive Yield Stress | Varies with solids concentration | Critical parameter for deformation modeling under load |

The compressional rheology of fresh feces exhibits more favorable dewatering characteristics compared to wastewater sludge, supporting higher final cake solids concentrations and improved dewatering kinetics [6]. These rheological properties are significantly influenced by environmental factors, particularly conductivity, which decreases dewaterability - an effect mitigated by implementing solid-liquid separation earlier in the process [6].

Troubleshooting Guides for Difficult Stool Consistencies

Handling Extremely Hard Stools (BSFS Types 1-2)

Problem: Sample Fragmentation and Non-representative Sampling Hard, lumpy stools (BSFS Types 1-2) present challenges for homogeneous sampling and mechanical testing due to their heterogeneous composition and structural integrity.

Solution:

- Pre-hydration Protocol: For texture analysis, carefully apply a standardized mist of physiological saline (0.9% NaCl) to the sample surface and allow equilibrium for 10 minutes before testing to create a more uniform surface without altering bulk properties.

- Multiple Point Measurement: Implement a grid-based measurement approach with a minimum of 5 penetration tests at different locations on the sample surface. Record the mean and coefficient of variation - a CV >25% indicates significant heterogeneity that must be accounted for in data interpretation.

- Cryogenic Grinding: For compositional analysis, flash-freeze samples in liquid nitrogen and use a cryogenic mill to create homogeneous powder while preserving molecular integrity. This enables representative sub-sampling for parallel analyses.

- Centrifugal Partitioning: For chemical extraction, use accelerated solvent extraction systems with increased pressure and temperature cycles to improve extraction efficiency from the dense, low-hydration matrix.

Managing Watery Stools (BSFS Types 6-7)

Problem: Liquid-phase Separation and Analyte Dilution Watery stools lack sufficient structural integrity for standard mechanical testing and undergo rapid phase separation, compromising sample representativeness.

Solution:

- Rapid Preservation: Immediately add preservation buffers (e.g., RNAlater for molecular analysis or formaldehyde-based fixatives for microscopic examination) upon sample collection to maintain analyte distribution.

- Vacuum Filtration Concentration: Use graded filtration systems with sequential membrane pores (20μm, 5μm, 0.8μm) to concentrate solid components while preserving the fractionated materials for separate analysis.

- Inline Turbidity Monitoring: Implement real-time turbidity sensors, as demonstrated in automated stool sampling systems, to characterize liquid stools without physical manipulation [7]. Calibrate turbidity readings against total solids concentration for quantitative assessment.

- Centrifugal Concentration: Standardize centrifugation protocols (e.g., 10,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C) to pellet solid components while retaining the aqueous phase for parallel analysis of soluble markers.

Addressing Subjectivity in Visual Classification

Problem: Inter-rater Variability in BSFS Scoring Subjective classification introduces significant variability, particularly in multi-center trials where consistent categorization is essential for reliable data.

Solution:

- Digital Image Analysis: Implement standardized imaging protocols with color calibration cards and scale references. Use machine learning algorithms trained on expert-classified images to reduce classification variance.

- Expert Consensus Training: Before study initiation, conduct calibration sessions using standardized image libraries until all raters achieve >90% agreement with expert consensus scores.

- Multi-parameter Assessment: Supplement BSFS classification with simple objective measures such as sample spread diameter on a standardized surface and water content via rapid moisture analysis to validate visual classifications.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How can we minimize contamination and cross-over between sequential stool samples in automated collection systems?

A1: Automated systems should incorporate zero dead-leg valves and clean-in-place procedures demonstrated to reduce bacterial carryover between samples by 1-3 log reductions [7]. System design should minimize stagnant volumes and include rinse cycles between samples. For high-sensitivity molecular applications, implement PCR inhibition testing to detect potential cross-contamination.

Q2: What is the optimal preservation method for stool samples intended for both microbiological and rheological analysis?

A2: Rheological properties are best measured on fresh samples within 30 minutes of collection. When parallel analyses are required, partition the sample immediately: allocate portion for texture analysis (test immediately), preserve portion in RNAlater for molecular work (4°C overnight then -80°C), and freeze a portion at -80°C for compositional analysis. Note that preservation methods inevitably alter mechanical properties.

Q3: How does stool water content correlate with objectively measured consistency values?

A3: Texture analyzer measurements show a strong negative linear correlation with stool water content (rrm = -0.781) [5]. However, this relationship is not perfectly linear across the entire consistency range, as water-holding capacity of insoluble solids and microbial composition also influence mechanical properties.

Q4: What factors contribute to the variability in rheological properties between samples?

A4: Key factors include: (1) total solids concentration, (2) dietary fiber composition and particle size, (3) microbial biomass and composition, (4) electrolyte concentration, and (5) mucosal content. Studies show that increased conductivity significantly hinders dewatering rate, suggesting ionic composition markedly influences stool rheology [6].

Q5: How can we improve patient adherence to stool sampling protocols in clinical trials?

A5: Studies indicate that disgust and embarrassment are major barriers to adherence [7]. Implementation of hands-free sampling systems that integrate with standard toilet hardware significantly improves acceptability [7]. Additionally, clear communication about the clinical value of the research and privacy protections enhances participant cooperation.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Direct Consistency Measurement via Texture Analysis

Objective: To quantitatively measure stool consistency using a texture analyzer, generating numerical values for research applications and validation of subjective scales.

Materials:

- TA.XTExpress Texture Analyser (Stable Micro Systems Ltd.) or equivalent

- Cylindrical probe (6 mm diameter)

- Standardized sample containers (60 mm diameter)

- Precision balance (±0.01 g)

- Physiological saline (0.9% NaCl)

- Disposable spatulas and forceps

Procedure:

- Collect stool sample in a clean, dry container. Process within 30 minutes of passage.

- Weigh sample container and record tare weight. Transfer approximately 50g of stool to container, avoiding selective sampling of heterogeneous specimens.

- Level the sample surface gently with a spatula without compression, creating a uniform testing surface.

- Mount cylindrical probe to texture analyzer and calibrate according to manufacturer specifications.

- Program analyzer with these parameters: pre-test speed 1.0 mm/s, test speed 2.0 mm/s, post-test speed 10.0 mm/s, penetration distance 5 mm, trigger force 5g.

- Position sample under probe and initiate test cycle.

- Record maximum force (g) required to achieve 5 mm penetration.

- Repeat measurement at 3 additional locations on sample surface if sufficient material exists.

- Calculate mean consistency value and coefficient of variation.

- Clean probe thoroughly with laboratory detergent and 70% ethanol between samples.

Validation: The log-transformed values should demonstrate a strong negative correlation with expert BSFS scores (expected rrm ≈ -0.789) and water content [5].

Protocol 2: Rheological Characterization for FEA Parameters

Objective: To determine key rheological parameters of stool samples for finite element analysis modeling.

Materials:

- Rheometer with parallel plate geometry (40 mm diameter)

- Temperature control unit

- Moisture analysis balance

- Centrifuge with swing-bucket rotor

- Precision sieves (500 μm, 250 μm)

Procedure:

- Prepare sample by homogenizing gently and passing through a 500 μm sieve to remove large particulate matter while preserving matrix structure.

- Determine initial solids content by drying 2g aliquot at 105°C for 24 hours.

- Load approximately 3mL of sample between rheometer plates, setting gap to 2 mm.

- Perform amplitude sweep test (0.1-100% strain, 1 Hz) to determine linear viscoelastic region.

- Conduct frequency sweep test (0.1-10 Hz) within linear region to characterize mechanical spectrum.

- Perform flow curve measurement (0.1-100 s⁻¹ shear rate) to model viscosity function.

- For compression testing, use a separate aliquot in a confined cell to determine compressive yield stress as a function of solids concentration.

- Fit data to appropriate rheological models (Herschel-Bulkley for flow curves, power law for viscoelastic properties).

Data Analysis: Calculate gel point (solids concentration where G' > G''), yield stress, flow behavior index, and consistency coefficient for incorporation into FEA simulations.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Stool Consistency Research

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TA.XTExpress Texture Analyser | Direct mechanical measurement of stool consistency | Provides quantitative consistency values in gram-force; validated against BSFS [5] |

| Parallel Plate Rheometer | Characterization of viscoelastic properties | Essential for obtaining FEA parameters such as viscosity and yield stress |

| RNAlater Stabilization Solution | Preservation of nucleic acids for parallel molecular analysis | Enables correlation of microbiome data with mechanical properties |

| Physiological Saline (0.9% NaCl) | Sample hydration control | Standardizes surface conditions for texture analysis without altering bulk properties |

| Graded Filtration Membranes | Size-fractionation of stool components | Separates particulate matter for individualized analysis of different fractions |

| Zero Dead-Leg Valves | Prevention of cross-contamination in automated systems | Critical for maintaining sample integrity in sequential sampling [7] |

| Turbidity Sensors | Real-time assessment of liquid stools | Enables characterization of watery samples without physical manipulation [7] |

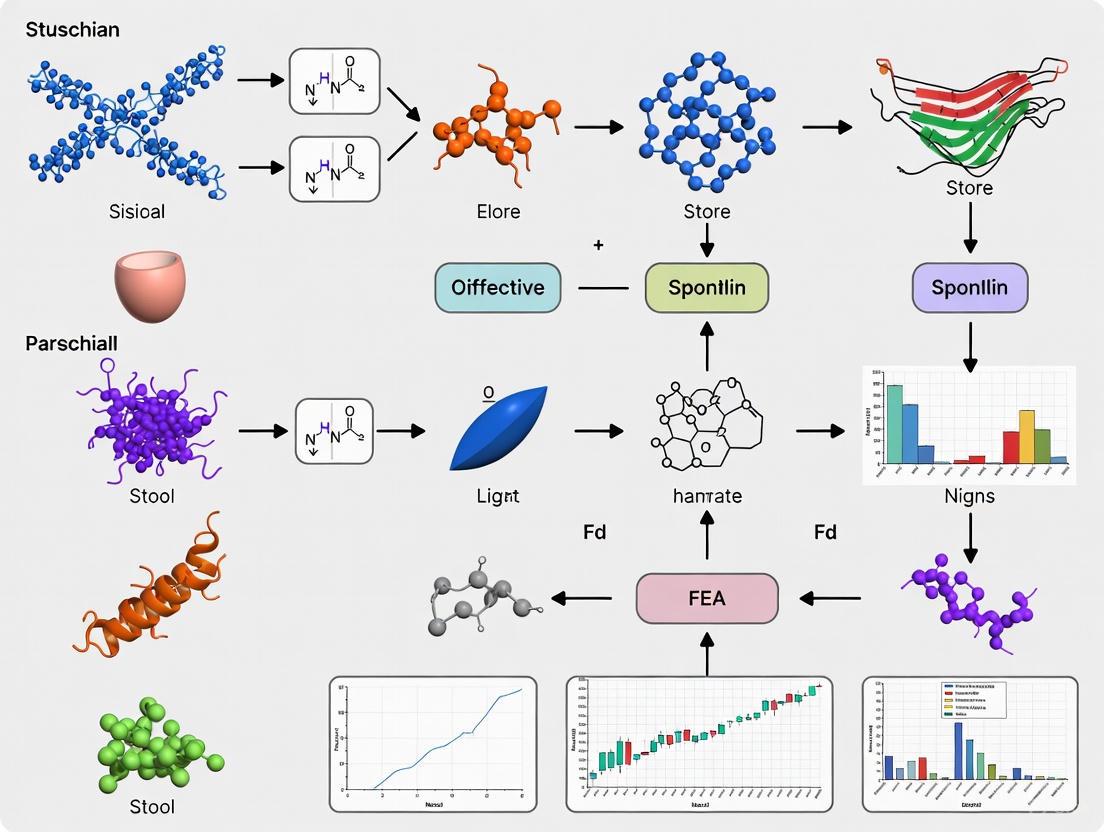

Workflow Visualization

The comprehensive assessment of stool consistency requires integration of both qualitative classification and quantitative measurement approaches. While the Bristol Stool Form Scale provides a rapid, clinically validated assessment tool, advanced research—particularly FEA modeling of difficult stool consistencies—demands the precise, continuous data provided by texture analysis and rheological characterization. The methodologies and troubleshooting guides presented here enable researchers to navigate the challenges associated with heterogeneous biological materials, generating reliable data for computational modeling and therapeutic development. As research in this field advances, the integration of automated sampling technologies with multi-parameter assessment will further enhance our understanding of stool biomechanics and its implications for gastrointestinal health and disease.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key biomechanical properties to measure when studying stool consistency? The three core properties are hardness, viscosity, and flow dynamics. Hardness refers to the material's resistance to deformation, viscosity describes its resistance to flow, and flow dynamics encompass how the material moves and behaves during defecation. Quantitative measurements of these properties are crucial for creating accurate computer models, such as those used in Finite Element Analysis (FEA), to simulate defecation and understand related disorders [8] [5] [9].

Q2: How does stool consistency directly impact defecatory function? Stool consistency significantly alters the biomechanics of defecation. Harder stools require greater expulsion pressure and a longer duration to evacuate. Research using simulated feces of different consistencies found that a harder probe required a maximum bag pressure of 140 cmH₂O and 18 seconds for evacuation, compared to 107 cmH₂O and 9 seconds for a softer probe [8]. This increased mechanical demand can contribute to symptoms like straining, which is associated with stools that are 1.88-fold harder [5].

Q3: What is the relationship between the Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS) and direct mechanical measurements? While the BSFS is a widely used visual classification tool, direct mechanical measurements provide more objective and quantitative data. Studies show a strong correlation between BSFS scores and directly measured stool consistency, though with considerable variance, especially for normal stool forms (BSFS 3-5) [5]. Technician-scored BSFS also tends to be more accurate than self-reported scores [10]. Therefore, for precise FEA research, direct mechanical measurement is recommended to supplement BSFS classification.

Q4: What experimental methods are available for direct measurement of stool consistency? The primary method is mechanical analysis using a texture analyzer (e.g., TA.XTExpress). In a standard protocol, a cylindrical probe is pushed into the stool surface at a defined speed (e.g., 2.0 mm/s) to a set depth (e.g., 5 mm), and the resistance force (in gram-force) is recorded [5]. Other technologies include penetrometers and viscometers [5], as well as novel devices like "Fecobionics"—a simulated feces probe that measures pressure and bending angles during evacuation [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Material Model Instabilities in FEA of Stool Mechanics

Problem: Your Finite Element Analysis (FEA) simulation of stool deformation is failing to converge or producing unrealistic results.

Solution: This often stems from an improperly defined material model. Stool is a complex, non-linear biological material.

- Step 1: Select an Appropriate Constitutive Model. Avoid overly simple linear elastic models. For soft stools (BSFS 5-7), consider a hyperelastic model like Neo-Hookean or Ogden that can handle large deformations. For harder stools (BSFS 1-2), a plastic or viscoelastic model may be more appropriate to capture permanent deformation and time-dependent behavior [9].

- Step 2: Calibrate Model Parameters with Experimental Data. Use data from texture analysis or rheological studies to inform your model's parameters. For example, the log-transformed consistency values for human stools typically range from ~1.4 ln(gf) for soft stools to ~5.0 ln(gf) for hard stools [5].

- Step 3: Check Element Formulation and Mesh. Use elements suitable for large strain and incompressible material behavior (e.g., C3D8H in Abaqus). Refine the mesh in areas of high stress concentration [11].

Guide 2: Addressing High Variance in Stool Consistency Measurements

Problem: Measurements of stool consistency from your samples show high variability, making it difficult to establish clear trends.

Solution: Implement standardized protocols for sample handling and measurement.

- Step 1: Standardize Sample Preparation. Stool samples should be measured shortly after defecation (within a few hours) and should be analyzed at a consistent temperature to prevent changes in water content and rheology [5].

- Step 2: Perform Multiple Measurements. Do not rely on a single measurement per sample. Take multiple readings from different lumps throughout the length of a specimen and use the median value to account for internal heterogeneity [5].

- Step 3: Control for Subject Factors. Document and account for factors known to affect consistency, such as straining during evacuation (which is linked to harder stools) and time of day (morning stools may be softer) [5]. Using technician-scored BSFS instead of self-reported scores can also reduce variance [10].

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Stool Consistency Measurements by Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS)

This table summarizes quantitative stiffness data measured directly from stool samples using a texture analyzer, correlated with BSFS types [5].

| BSFS Type | Description | Log-Transformed Consistency (ln g/probe), Mean ± SD | Number of Samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 or 2 | Hard Stool | 4.956 ± 0.593 | 21 |

| 3, 4, or 5 | Normal Stool | 3.176 ± 0.877 | 217 |

| 6 or 7 | Soft Stool | 1.394 ± 0.562 | 14 |

Table 2: Defecation Parameters for Simulated Feces of Different Consistencies

This table shows key biomechanical parameters measured during the evacuation of simulated feces ("Fecobionics" probes) of different stiffness [8].

| Probe Hardness (Shore) | Approx. BSFS | Defecation Duration (seconds) | Maximum Bag Pressure (cmH₂O) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0A | Type 2-4 | 9 (8-12) | 107 (96-116) |

| 10A | Type 2-4 | 18 (12-21) | 140 (117-162) |

| 40A | Harder than normal | Not Significantly Different from 10A | Not Significantly Different from 10A |

Note: Data presented as median (quartiles). Significant differences were primarily observed between the 0A and 10A probes.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Direct Measurement of Stool Consistency using a Texture Analyzer

Objective: To obtain a quantitative, mechanical measure of stool hardness.

Materials:

- Texture Analyzer (e.g., TA.XTExpress, Stable Micro Systems Ltd.)

- Cylindrical probe (e.g., 6 mm diameter)

- Fresh stool sample

- Sample container

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Transfer the fresh stool sample to a standardized container. Ensure the surface is relatively level.

- Instrument Setup: Configure the texture analyzer with the cylindrical probe. Set the test speed to 2.0 mm/s and the target penetration depth to 5 mm.

- Measurement: Position the probe above the sample surface and initiate the test. The probe will descend and penetrate the stool.

- Data Recording: The instrument records the force (in gram-force) required to achieve the 5 mm depth. This value is the primary measure of consistency.

- Replication: Repeat the measurement at several different locations on the same stool sample to account for heterogeneity. Calculate the median consistency value for the sample [5].

- Data Transformation: For statistical normalization, use the natural log-transformed value (ln g/probe) for analysis [5].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Defecatory Function using Simulated Feces (Fecobionics)

Objective: To assess anorectal function and flow dynamics during a simulated defecation event.

Materials:

- Fecobionics device (a probe with pressure sensors and motion sensors)

- Lubricant

Methodology:

- Preparation: Select a Fecobionics probe of desired consistency (e.g., 0A, 10A, 40A shore hardness). Lightly lubricate the probe.

- Insertion: Insert the probe into the rectum of the study participant.

- Distension: After a brief rest, slowly fill the device's internal bag with water or air until the participant reports a definite urge to defecate. Record this volume (urge volume).

- Evacuation: The investigators then leave the room, and the participant evacuates the device in privacy, mimicking a natural defecation.

- Data Acquisition: The device records multiple parameters in real-time, including pressures at the front, rear, and inside the bag, as well as the bending angle (anorectal angle) during evacuation [8].

- Analysis: Key outcome measures include defecation duration, maximum pressures generated, and the rectoanal pressure gradient (RAPG).

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Stool Biomechanics Research

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Texture Analyzer (TA.XTExpress) | Provides direct, quantitative measurement of stool consistency (hardness) by measuring the force required to deform a sample [5]. |

| Fecobionics Probe | An electronic, simulated feces device that integrates pressure sensors and motion sensors to measure anorectal function and flow dynamics during a physiologically realistic evacuation [8]. |

| Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS) | A standardized visual tool for the initial classification of stool form into one of seven types. It is a common reference in both clinical and research settings [12] [5] [10]. |

| Silicone Resins (Varying Hardness) | Used to fabricate Fecobionics probes or other simulated stools with standardized, reproducible mechanical properties (e.g., 0A, 10A, 40A shore hardness) for controlled experiments [8]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 1: Stool Biomechanics Research Workflow

Diagram 2: Key Property Interrelationships

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Finite Element Analysis in Pelvic Floor Research

This section addresses common computational challenges encountered when developing finite element models for investigating bowel dysfunction.

Table 1: Common FEA Errors and Solutions

| Error / Warning Message | Potential Root Cause | Solution / Diagnostic Action |

|---|---|---|

| Model fails to converge to a solution [11] | Insufficiently constrained model (rigid body modes), contact issues, or inappropriate material model [11]. | Check constraints to ensure all rigid body motions are eliminated. Review contact definitions and parameters [11]. |

| "Elements are distorted" or "Negative Jacobian" [11] | Excessive deformation causing poor-quality elements or an unstable material model [11]. | Refine the mesh in areas of high deformation. Run a preliminary analysis with smaller load steps [13]. |

| Inaccurate stress/strain results (e.g., stress exceeds failure threshold without simulated failure) [13] | Use of an overly simplified linear elastic material model that does not account for material failure [13]. | Implement a more advanced material model that includes damage or plasticity [13]. |

| Solver stops with a "Zero pivot" warning [11] | Under-constrained model or poorly defined contact, leading to numerical instability [11]. | Check for and eliminate any potential rigid body motions. Review contact pairs for initial overclosures or gaps [11]. |

| Solution is strongly mesh-dependent | The mesh is too coarse to capture the necessary physics, such as stress concentrations. | Perform a mesh sensitivity study to ensure results do not change significantly with further mesh refinement [13]. |

| Model validation fails (simulation does not match dynamic MRI data) [14] [15] | Incorrect boundary conditions, material properties, or anatomical inaccuracies in the 3D model [14]. | Re-check the assignment of all boundary conditions and material properties. Verify the geometric accuracy of the model against medical images [14] [15]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between the Finite Element Method (FEM) and Finite Element Analysis (FEA)? [16] A: The Finite Element Method (FEM) is the mathematical technique used to break down complex systems into smaller, simpler elements and solve the underlying differential equations. Finite Element Analysis (FEA) is the broader process of applying this method to predict an object's behavior and interpret the results. [16]

Q2: How can I validate that my pelvic floor model is biomechanically accurate? [14] [15] A: Model validity can be verified by comparing simulation outputs to actual physiological data. One effective method is to simulate maneuvers like the Valsalva and compare the resulting changes in anatomical angles (e.g., Anorectal Angulation - ARA) and organ displacements against those observed in dynamic MRI scans from the same subject. Geometric deviations should ideally be controlled within 10%. [14] [15]

Q3: My model involves complex interactions between muscles and organs. What type of analysis should I use? A: For simulating physiological processes like bowel movement or Valsalva, which involve large deformations and changing contacts, a dynamic analysis is typically required as it accounts for variation over time. [16] For simulating the effect of sustained muscle tonus, a static analysis might be appropriate. [16]

Q4: Can FEA simulate the effects of different rehabilitation treatments? [15] A: Yes. The effects of physical rehabilitation methods (e.g., exercise, electrical stimulation) can be simulated by proportionally altering the material properties of the targeted muscles in the model. For example, increasing the elastic modulus of a muscle simulates increased strength and stiffness gained through training, allowing researchers to quantify the impact on functional angles like the Retrovesical Angle (RVA) and ARA. [15]

Q5: What are the critical limitations of FEA that I must consider? [16] A: The accuracy of FEA results is entirely dependent on the quality of the inputs—a principle often called "garbage in, garbage out." The model's predictions are only as good as the accuracy of the geometry, material properties, boundary conditions, and loading applied. The results should always be reviewed with a critical, domain-knowledge perspective to assess their physical plausibility. [16] [13]

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Detailed Protocol: Developing a Subject-Specific Pelvic Floor Finite Element Model [14]

Medical Image Acquisition:

- Participants: Recruit eligible volunteers (e.g., >60 years) with normal pelvic floor function and no dysfunction. Informed consent and ethical approval are mandatory. [14]

- Scanning: Collect both Computed Tomography (CT) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) data. CT provides high-resolution bone geometry, while MRI optimally differentiates soft tissues (muscles, fascia, organs). [14]

- Dynamic Sequences: Perform dynamic MRI capturing specific physiological maneuvers (e.g., Kegel, Valsalva) to provide data for subsequent model validation. [14]

3D Geometric Model Reconstruction:

- Data Import: Import DICOM images from CT and MRI scans into medical image processing software (e.g., Mimics). [14]

- Segmentation: Manually outline and threshold the relevant anatomical structures in each cross-sectional image. This includes bones, pelvic floor muscles (e.g., levator ani), core muscles (e.g., abdominals, back, hip), and organs (bladder, urethra, rectum). Consensus between experienced radiologists is recommended. [14]

- 3D Generation: Use the software's "calculate 3D" function to create initial rough 3D geometry from the segmented masks. Apply smoothing functions to refine the model edges. [14]

Finite Element Model Preparation:

- Surface Generation: Export the 3D geometry and import it into reverse engineering software (e.g., Geomagic Studio) to generate a solid, watertight 3D model suitable for meshing. [14]

- Meshing: Import the solid model into FEA software (e.g., Abaqus) and discretize it into finite elements (mesh). Refine the mesh in areas of expected high stress or deformation. [13]

- Material Assignment: Define material properties (e.g., linear elastic, hyperelastic) for different tissues based on literature or experimental data. [13]

- Boundary Conditions & Loading: Apply realistic constraints to the model (e.g., fixing the sacrum) and simulate loading conditions (e.g., intra-abdominal pressure during Valsalva). [14]

Table 2: Quantitative Validation Metrics for Pelvic Floor Models [15]

| Metric | Full Name & Description | Typical Validation Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| ARA | Anorectal Angulation: The angle between the longitudinal axis of the anal canal and the posterior rectal wall. A key indicator for fecal control. | Deviation from imaging-based measurements < 10% [15] |

| RVA | Retrovesical Angle: The angle between the base of the bladder and the long axis of the urethra. Used to assess urinary control. | Deviation from imaging-based measurements < 10% [14] |

| Waist Circumference Change | The change in abdominal circumference during a Valsalva maneuver. | Deviation from imaging-based measurements < 10% [15] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Pelvic Floor FEA Research

| Item / Resource | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Medical Image Processing Software (e.g., Mimics) | Used to create 3D geometric models from DICOM-formatted CT and MRI scans through segmentation and thresholding. [14] |

| Reverse Engineering Software (e.g., Geomagic Studio) | Converts the rough 3D geometry generated from segmentation into a smooth, high-quality surface model suitable for finite element meshing. [14] |

| FEA Software (e.g., Abaqus) | The core simulation environment for meshing the geometry, assigning material properties, applying boundary conditions, solving the finite element equations, and post-processing results. [14] [11] |

| Post-Processing Tool (e.g., ParaView) | An open-source tool for advanced visualization and analysis of simulation results, such as stress distributions and deformation animations. [13] |

| Linear Elastic Material Model | A simple material model defining tissues with a constant Young's modulus and Poisson's ratio. Often a starting point for analysis. [13] |

| Hyperelastic Material Model | A complex material model used for simulating soft tissues (like muscles and organs) that undergo large, reversible deformations. [13] |

| Dynamic Analysis | An analysis type used to simulate physiological events that change over time, such a Valsalva maneuver or muscle contraction. [16] |

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Finite Element Analysis Workflow

Linking Stool Consistency to FEA and Treatment

FEA Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the key considerations when modeling biological soft tissues? Biological soft tissues are typically hydrated porous hyperelastic materials. They consist of a complex solid skeleton with fine voids filled with fluid. A key consideration is the mechanical interaction between the solid and fluid phases, which can be analyzed using finite element methods (FEM) based on mixture theory [17].

2. My simulation shows unrealistic stress patterns. What could be wrong? Unrealistic stress patterns often result from incorrect boundary condition definitions. A common mistake is treating tissue boundaries as rigid or freely permeable, whereas in reality, many tissues are surrounded by deformable membranes that control transmembrane flows. Ensure your model's boundary conditions accurately reflect the physiological membrane properties [17].

3. How do I model fluid-structure interaction in biological systems? The Immersed Finite Element Method (IFEM) is effective for fluid-structure interaction problems. In IFEM, a Lagrangian solid mesh moves on top of a background Eulerian fluid mesh, greatly simplifying mesh generation. The continuity between fluid and solid subdomains is enforced via velocity interpolation and force distribution [18].

4. What are common pitfalls in modeling hydrated tissues? A frequent pitfall is neglecting the stress relaxation phenomenon caused by interactions between elastic tissue deformation, pore water pressure gradients, and fluid movement. For large deformations of hydrated porous hyperelastic material, use formulations that account for fluid trapped by impermeable membranes, which can cause tissue swelling [17].

5. How can I validate my FEA model for biological materials? Validation should include compression tests comparing simulated results with experimental data. For hydrated tissues, verify that your simulation shows appropriate stress relaxation behavior and fluid-induced swelling around contact areas when surrounded by impermeable membranes [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Convergence issues in hyperelastic material analysis

- Symptoms: Solver fails to converge, excessive distortion errors

- Possible Causes:

- Overly large load increments causing element distortion

- Inappropriate hyperelastic material model parameters

- Insufficient mesh refinement in high-strain regions

- Solutions:

- Reduce load increments and use automatic stabilization

- Validate material parameters with experimental data

- Implement adaptive meshing in critical regions [18]

Problem: Inaccurate pore pressure distribution in hydrated tissues

- Symptoms: Unrealistic fluid flow patterns, incorrect stress relaxation

- Possible Causes:

- Incorrect permeability definitions

- Improper boundary conditions for fluid flow

- Neglecting membrane control of transmembrane flows

- Solutions:

- Implement nonlinear finite element formulation of mixture theory with pore water pressure and solid displacement as nodal unknowns

- Use Neumann boundary conditions to control fluid flow rate across membranes [17]

Problem: Fluid-structure interaction instabilities

- Symptoms: Oscillations in solution, solver divergence

- Possible Causes:

- Poorly coupled fluid and solid domains

- Inadequate time step selection

- Insufficient numerical stabilization

- Solutions:

- Apply the Immersed Finite Element Method (IFEM) with RKPM delta function for improved coupling

- Use stabilized equal-order finite element formulation to prevent numerical oscillations

- Implement GMRES iterative algorithm with matrix-free techniques for efficiency [18]

Quantitative Data for FEA of Biological Materials

Table 1: Key Parameters for Modeling Hydrated Biological Tissues

| Parameter | Typical Range | Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluid (Pore) Pressure (p) | Variable | Pressure of fluid within tissue voids | Appears in Cauchy stress tensor: σ = -pI + σᴱ [17] |

| Effective Stress (σᴱ) | Material-dependent | Stress induced by solid deformation | Corresponds to classical consolidation theory [17] |

| Solid Displacement (uˢ) | Problem-dependent | Movement of solid skeleton | Primary unknown in nonlinear FEM formulations [17] |

| Fluid Velocity (vᶠ) | Flow-dependent | Movement of fluid phase | Governs transmembrane flow in tissues [17] |

Table 2: Finite Element Formulations for Biological Tissues

| Formulation Type | Nodal Unknowns | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonlinear Mixed FEM | Pressure, Solid displacement | Effective for large deformations | May require stabilization [17] |

| Penalty FEM | Solid displacement, Fluid velocity | Handles hyperelastic solid phase | Less accurate for complex flows [17] |

| Three-Field Mixed FEM | Solid displacement, Fluid velocity, Pressure | Improved performance over two-field | Increased computational cost [17] |

| Immersed FEM (IFEM) | Fluid velocity, Solid displacement | Simplified mesh generation | Complex implementation [18] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Compression Test of Hydrated Porous Hyperelastic Tissue

Purpose: To characterize mechanical behavior of hydrated biological tissues under compression.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare hydrated tissue sample surrounded by a flaccid impermeable membrane.

- Compression Setup: Position a platen to compress part of the top surface of the tissue.

- Simulation Parameters:

- Use nonlinear finite element formulation with pore water pressure and solid displacement as nodal unknowns

- Apply Neumann boundary conditions to control fluid flow across the membrane

- Model solid phase as hyperelastic material

- Data Collection:

- Monitor stress relaxation over time

- Measure tissue swelling around the platen

- Record pore water pressure gradients [17]

Protocol 2: Fluid-Structure Interaction Analysis using IFEM

Purpose: To simulate interaction between deformable structures and surrounding fluid.

Methodology:

- Domain Setup:

- Create Eulerian fluid mesh spanning entire computational domain

- Generate Lagrangian solid mesh on top of fluid mesh

- Coupling Implementation:

- Use RKPM delta function for velocity interpolation and force distribution

- Apply stabilized equal-order finite element formulation for fluid

- Solution Procedure:

- Employ Newton-Raphson method for nonlinear systems

- Implement GMRES iterative algorithm with matrix-free techniques

- Calculate residuals based on matrix-free techniques [18]

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: FEA Analysis Workflow for Biological Materials

Diagram 2: Biological Tissue Modeling Approach

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for FEA of Biological Materials

| Research Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Nonlinear FEM Software Platform | Provides computational framework for analysis | Essential for implementing mixed finite element formulations [17] |

| Hyperelastic Material Model Library | Defines stress-strain relationships for biological tissues | Critical for accurate solid phase representation [17] |

| Porous Media Flow Solver | Models fluid flow through tissue voids | Necessary for hydrated tissue analysis [17] |

| Fluid-Structure Interaction Module | Handles coupling between fluid and solid domains | Required for IFEM applications [18] |

| Mesh Generation Tools | Creates Lagrangian and Eulerian meshes | Fundamental for domain discretization [18] |

| RKPM Delta Functions | Enables velocity interpolation and force distribution | Key component for IFEM coupling [18] |

| Stabilized Formulation Algorithms | Prevents numerical oscillations | Important for solutions without excessive numerical dissipation [18] |

Building Robust FEA Models for Stool-Tissue Interaction

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the key medical imaging modalities for creating anatomical models, and how do they compare?

The primary modalities for creating high-resolution anatomical models are Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Computed Tomography (CT). Their data is often integrated with other sources to build comprehensive models [19].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Medical Imaging Modalities for Model Creation

| Modality | Primary Use & Strengths | Key Contributions to Model Creation | Common Clinical Applications in Modeling |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRI | Excellent for visualizing soft tissues, organs, and the central nervous system without ionizing radiation [19]. | Provides high-resolution data on anatomy and physiological processes; essential for digital replication [19]. | Cardiovascular system simulation, brain modeling, soft tissue tumors [19]. |

| CT | Ideal for capturing detailed bony structures and anatomy; provides high-contrast images of dense tissues [20]. | Offers high spatial resolution for precise geometric reconstruction of bones and other structures [19]. | Spinal anomalies, craniofacial reconstructions, skull base tumors [20]. |

| PET | Functional imaging that shows metabolic activity [19]. | Documents physiological processes and can identify abnormalities for dynamic modeling [19]. | Earlier disease detection, monitoring treatment responses in oncology [19]. |

| Ultrasound | Real-time, dynamic imaging [19]. | Provides dynamic data for real-time simulation and monitoring [19]. | Not specified in available literature. |

FAQ 2: My 3D model files are too large and slow to process. What are the common causes and solutions?

Large file sizes and slow processing are frequent bottlenecks. Here are the main causes and strategies to address them:

- Cause: Excessive Spatial Resolution. Using a higher image resolution than necessary for your model's purpose drastically increases data volume and computational load [19].

- Solution: Determine the appropriate voxel size for your research question. For a macro-scale anatomical model, a lower resolution might be sufficient and will significantly reduce computational demands [19].

- Cause: Complex Model Geometry. Anatomical structures with intricate details (e.g., trabecular bone, vascular networks) naturally result in models with high polygon counts [21].

- Solution: Utilize model simplification and reduction techniques. Consider using Reduced-Order Models (ROM) to decrease computational complexity while preserving essential model behavior [19].

- Cause: Software and Hardware Limitations. Standard workstations may lack the necessary memory and processing power [21].

- Solution: Leverage High-Performance Computing (HPC) resources or cloud-based platforms designed for complex simulations. Using a Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) for rendering and computation can also dramatically improve performance [19].

FAQ 3: How do I ensure my 3D anatomical model is accurate and validated?

A robust Verification, Validation, and Uncertainty Quantification (VVUQ) process is critical for ensuring model fidelity [19]. The following workflow, implemented by leading clinical institutions, outlines a rigorous path from scan to validated model:

Key steps in this workflow include:

- Quality Control Checks: Every step, from image processing to final model printing, should have checks to ensure the model accurately represents the source data [20].

- Direct Comparison: The final patient-specific 3D model must be exactly what a surgeon would find in the operating room, validated against the original imaging [20].

- Adherence to Standards: The manufacturing process should follow national standards (e.g., ASTM) to ensure accuracy and safety [20].

FAQ 4: What technical barriers exist when integrating multimodal data (like MRI and CT) into a single model?

Integrating data from multiple sources presents several technical challenges [19]:

- Multimodal Integration Complexity: Fusing data from different imaging modalities (e.g., MRI with CT) and other sources (genomic, wearable sensors) is technically complex due to differing formats, resolutions, and physical meanings [19].

- Data Scarcity and Incompleteness: It is often difficult or impossible to directly measure all physiological parameters needed for a complete model, leading to gaps in data [19].

- Computational Demands: Integrating and running simulations with large, multimodal datasets requires significant computational resources [19].

Solutions involve using AI-driven data augmentation to fill data gaps and real-time model optimization techniques to manage computational load [19]. Machine learning models, particularly foundational models pre-trained on large datasets, can help create robust models even with incomplete data [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Medical Image Processing and Model Creation

| Tool Category | Specific Examples / Algorithms | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning for Segmentation | Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) [19]. | Automates the identification and outlining of anatomical structures in medical images. |

| Simulation & Modeling | Finite Element Modeling (FEM), Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) [19]. | Performs biomechanical and fluid flow simulations on the anatomical model. |

| 3D Modeling & Printing Software | Standard Tessellation Language (STL) files [19]. | Creates and edits virtual 3D models and prepares them for 3D printing. |

| Data Integration & Analysis | Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Graph Neural Network (GNN) [19]. | Analyzes and integrates multimodal data sets for a comprehensive model. |

Advanced Troubleshooting: From Image to Biomechanical Model

The process of creating a biomechanical model, such as for studying stool consistency, relies on a multi-stage pipeline. The diagram below illustrates the logical flow from data acquisition to a functional, validated simulation, highlighting areas where troubleshooting is most critical.

Troubleshooting Key Stages:

Stage: Image Segmentation

- Problem: Automated segmentation fails on soft tissues with low contrast.

- Solution: Utilize advanced ML models like Hypergraph Convolutional Neural Networks (HGCNN) or Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) which can better handle ambiguous boundaries and learn from complex data relationships [19]. Manually correct segmentation errors before proceeding.

Stage: Mesh Generation

- Problem: The generated mesh is non-manifold or contains too many elements for efficient simulation.

- Solution: Use meshing software that allows for control over element size and type. Implement mesh refinement in areas of high stress or geometric complexity and mesh coarsening in areas of low interest. Validate mesh quality before simulation.

Stage: Material Property Assignment

- Problem: Material properties for biological tissues are unknown or highly variable.

- Solution: This is a key challenge. Conduct a sensitivity analysis to understand how model outputs depend on material parameters. Use inverse analysis techniques, where simulation results are matched to experimental data (if available) to estimate property values.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main categories of mesh simplification algorithms, and how do they differ? Mesh simplification algorithms are primarily divided into two categories:

- Geometry-driven algorithms: These focus solely on the 3D geometry of the model (vertices, edges, faces) to reduce complexity. Common methods include vertex clustering, vertex decimation, and edge folding. They strive for geometric fidelity but often ignore appearance attributes like color and texture, which can lead to suboptimal results for textured models [22].

- Appearance attribute-driven algorithms: These algorithms consider both the geometry and appearance attributes (such as texture, color, and lighting) during the simplification process. An extension of the Quadric Error Metric (QEM) that incorporates appearance attributes falls into this category. They are better at preserving the visual appearance of the simplified model [22].

Q2: During the simplification of a textured 3D model, my results show significant texture distortion and deformation. How can I mitigate this? Texture distortion often occurs when simplification is treated only as a post-processing step without integrating the original 3D reconstruction data. To mitigate this:

- Integrate the Reconstruction Pipeline: Utilize the recovered 3D scene structure and calibrated images from the reconstruction process. Construct a reference 3D model scene and use it to generate a reference image set for texture remapping. This helps maintain texture fidelity after simplification [22].

- Use Advanced Error Metrics: Employ algorithms that include constraints for texture preservation. For instance, one method involves segmenting the surface mesh based on topology and appearance and deriving an error metric that minimizes texture distortion [22]. Another algorithm constrains vertices with sharp features and uses Mahalanobis distance to manage multiple constraints effectively, preserving structural details [23].

Q3: How can I validate the accuracy of a simplified 3D model? The accuracy of a simplified model can be quantitatively and qualitatively assessed using several metrics:

- Geometric Fidelity: Use distances like the Hausdorff distance to measure the maximum geometric deviation between the original and simplified model [23].

- Visual Inspection: Compare rendered images of the original and simplified models from multiple viewpoints [22].

- Performance Metrics: Evaluate the simplification time and the improvement in rendering frame rate after simplification [23].

- Mechanical Validation (for FEA models): Compare simulated outcomes from your finite element model (e.g., internal pressure, organ deformation) with actual physiological data captured via dynamic MRI during maneuvers like Kegel exercises or Valsalva [24] [14].

Q4: My 3D reconstructed models have a complex mesh structure that puts great pressure on real-time rendering. What is an effective simplification strategy? For complex models like buildings, a strategy based on triangle folding can be effective. To compensate for the potential loss of model details, introduce more constraints for error control. Specifically:

- Constrain vertices with obvious sharp features to keep the model's structure from deforming.

- Calculate the Mahalanobis distance of each introduced constraint factor to manage the higher algorithm complexity that comes with multiple constraints. This approach helps preserve detailed features and the model's overall visual effect while significantly reducing the mesh count [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: High Texture Distortion Post-Simplification

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Blurred or misaligned textures on the simplified model. | The simplification algorithm is purely geometry-driven and does not account for texture information [22]. | Switch to an appearance attribute-driven simplification algorithm [22]. |

| Stretched or warped texture patterns. | Texture coordinates are not correctly updated after edge collapse or vertex removal operations [22]. | Implement a post-simplification texture coordinate update step that adjusts coordinates based on the new mesh geometry [22]. |

| Consistent texture artifacts across multiple LODs. | The original, high-resolution texture is being used on a very coarse mesh, causing over-sampling. | Implement a texture content simplification method that downsamples the reference image based on the mesh simplification parameters [22]. |

Workflow for Mitigating Texture Distortion: The following diagram illustrates a proposed workflow that integrates 3D reconstruction with simplification to minimize texture issues.

Problem 2: Model Geometry is Poorly Preserved After Simplification

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Loss of sharp edges and fine structural details. | The simplification error metric does not adequately penalize the removal of perceptually important features [23]. | Introduce constraints that specifically protect vertices and edges with high curvature or sharp features [23]. |

| The overall shape of the model is deformed. | The simplification algorithm is too aggressive, and the tolerance for geometric error is set too high. | Adjust the simplification parameters to reduce the allowable error threshold for each simplification step. Use a more conservative simplification rate. |

| Irregular surface or "holes" in the mesh. | The simplification process violates the mesh's topological structure. | Use an algorithm that includes topological checks to ensure the manifold property of the mesh is maintained after each operation. |

Problem 3: Long Processing Times for Complex Model Simplification

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Simplification of a high-polygon model takes hours. | The algorithm has high computational complexity, often O(n log n) or worse, for models with millions of polygons. | Pre-process the model by segmenting it into regions based on geometric or texture similarity. This allows for more efficient, localized simplification [22]. |

| System runs out of memory during simplification. | The data structures holding the mesh and error metrics are too large for available RAM. | Implement out-of-core processing techniques that work on portions of the mesh at a time, or use more efficient data structures like progressive meshes. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: QEM-Based Simplification with Texture Fidelity

This protocol is adapted from a method that integrates 3D reconstruction data to preserve textures [22].

1. Objective: To simplify a 3D mesh while minimizing texture distortion and reducing texture data volume. 2. Materials:

- Original 3D mesh model

- Set of calibrated images from the reconstruction process 3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Construct Reference 3D Model Scene. Using the original mesh and calibrated images, construct a reference 3D scene with high-quality texture mapping.

- Step 2: Generate Reference Image Set. Back-project the reference 3D model scene using the known view poses (external camera parameters) to generate a consistent set of reference images.

- Step 3: Mesh Simplification. Apply a Quadric Error Metric (QEM) algorithm to simplify the mesh geometry. The cost of edge collapse operations can be modified to consider texture deviation.

- Step 4: Texture Remapping and Simplification. For the simplified mesh, perform texture remapping using the reference image set as the data source. Adaptively downsample the texture resolution based on the mesh simplification parameters to reduce data size. 4. Validation:

- Qualitatively compare the texture quality of the original and simplified models.

- Quantitatively measure the geometric error (e.g., using Hausdorff distance) and the reduction in texture data size [22] [23].

Protocol 2: Building Model Simplification Using Triangle Folding

This protocol is based on a simplification algorithm designed for complex 3D building models [23].

1. Objective: To reduce the number of triangular meshes in a complex 3D building model without affecting its overall visual effect. 2. Materials:

- A 3D building model with a large number of triangular meshes. 3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Identify Feature Vertices. Calculate the sharp features of the model's vertices. Vertices with values exceeding a threshold are identified as feature vertices to be constrained.

- Step 2: Calculate Constraint Factors. Introduce multiple constraint factors (e.g., related to curvature, edge length, dihedral angle) to control the simplification error.

- Step 3: Compute Mahalanobis Distance. To manage the complexity introduced by multiple constraints, calculate the Mahalanobis distance for the constraint factors. This helps in evaluating the overall error while considering the correlation between different constraints.

- Step 4: Perform Triangle Folding. Execute the triangle folding simplification operation, prioritizing operations with the smallest Mahalanobis distance error. 4. Validation:

- Use the Hausdorff distance to quantitatively evaluate geometric deviation.

- Record the simplification time and the resulting frame rate during rendering for performance evaluation [23].

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key software and data components essential for experiments in 3D reconstruction and model simplification.

| Item Name | Function/Benefit | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Mimics (Materialise NV) | Medical image analysis software used to import MRI/CT DICOM data and generate initial 3D geometry models through thresholding and segmentation [24] [14]. | Creating 3D models from medical scans for Finite Element Analysis, such as modeling the pelvic floor for biomechanical studies [24] [14]. |

| Geomagic Studio (3D Systems Inc) | Reverse engineering software used to convert a 3D image (e.g., from Mimics) into a accurate, water-tight solid 3D model suitable for simulation and analysis [24] [14]. | Refining 3D models for FEA; processing the pelvic floor model by gridding and surface fitting [24] [14]. |

| Abaqus (Dassault Systèmes) | A software suite for finite element analysis and computer-aided engineering. It is used to simulate the mechanical behavior of the 3D model under various conditions [24] [14]. | Performing biomechanical simulations; analyzing stress and strain in a pelvic floor model during different physiological states [24] [14]. |

| Quadric Error Metric (QEM) | A powerful algorithm for mesh simplification that calculates the error of potential edge collapse operations as the sum of squared distances to a set of associated planes. It is efficient and produces high-quality results [22]. | General-purpose mesh simplification for reducing polygon count while preserving geometric details. Can be extended to consider texture attributes [22]. |

| Reference Image Set | A set of images generated by back-projecting a textured 3D model. It provides a consistent, high-fidelity source for texture remapping after mesh simplification [22]. | Integrated 3D reconstruction and simplification pipelines to avoid texture distortion and achieve texture content simplification [22]. |

FAQs on Material Model Selection and Troubleshooting

1. How do I choose between a Linear Elastic and a Hyperelastic model?

The choice depends on the material you are modeling and the expected amount of deformation.

- Linear Elastic models follow Hooke's Law, where stress is directly proportional to strain. Use this model for materials like metals, ceramics, or rigid structures that undergo small deformations (typically less than 1%) [25].

- Hyperelastic models are designed for materials like rubber, soft biological tissues, or polymers that can experience extremely large, reversible deformations (often in the range of 100% to 700% strain). They use a strain energy density function to capture the nonlinear relationship between stress and strain [25] [26]. For soft tissues, which are often inhomogeneous and multiphasic, hyperelastic models are a foundational component in describing their complex, nonlinear behavior [27].

2. My FEA simulation with a Hyperelastic material won't converge. What should I check?

Convergence issues with hyperelastic materials are common and can be addressed by checking the following:

- Material Parameters: Ensure the parameters for your hyperelastic model (e.g., Mooney-Rivlin, Ogden) are accurately derived from experimental test data. An incorrect strain energy function can lead to non-physical results [28].

- Element Formulation: Use appropriate element types. For nearly incompressible materials like elastomers and soft tissues, hybrid elements (which often have an "H" in their name, like C3D8H in Abaqus) should be used to handle the incompressibility constraint [28].

- Contact Definitions: If your model involves contact, an ill-conditioned system can cause divergence. Check for initial penetrations and consider adjusting contact stiffness. Switching from Bonded to Frictional contact and using an "Adjust to Touch" interface treatment can improve convergence [29].

- Mesh Refinement: Perform a mesh sensitivity study. A mesh that is too coarse may not capture the large deformation gradients, while an excessively fine mesh increases computation time. The solution should not change significantly with further mesh refinement [30].

- Load Stepping: Nonlinear problems require the load to be applied in small increments. Reduce the initial time step size and increase the minimum number of substeps to allow the solver to converge [29].

3. What is the difference between a phenomenological and a micro-mechanical hyperelastic model?

Hyperelastic models are generally categorized based on their theoretical foundation [28]:

- Phenomenological Models: These are based on continuum mechanics and ideal elastomer properties. They mathematically fit the observed stress-strain data without considering the underlying microstructure. Examples include:

- Neo-Hookean

- Mooney-Rivlin

- Yeoh

- Ogden

- Micro-Mechanical Models: These models derive from the statistical mechanics of polymer chains, linking the macroscopic behavior to the network microstructure. Examples include:

- Arruda-Boyce

- Hybrid Models: These combine aspects of both phenomenological and micro-mechanical approaches. An example is the van der Waals model.

4. When is a Poroelastic model necessary, and what are its challenges?

A poroelastic model is essential for simulating saturated porous materials where the interaction between a solid matrix and interstitial fluid governs the mechanical response.

- When to Use: It is critical for tissues like articular cartilage and the intervertebral disc, which have a porous solid matrix saturated with fluid. Their nonlinear, time-dependent behavior (e.g., creep, stress relaxation) is governed by fluid flow and pressurization [27].

- Challenges: Developing these models is complex due to the tissue's inhomogeneous, multiphasic, and anisotropic (direction-dependent) structure. Users must be aware of the capabilities and limitations of these approaches to adequately simulate a specific biological phenomenon [27].

Comparison of Hyperelastic Models

The table below summarizes key hyperelastic models to guide your selection. The accuracy of a model is defined by how closely its predicted stress matches stresses derived from mechanical tests [28].

| Model Name | Category | Typical Use Cases | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neo-Hookean [28] | Phenomenological | Simple rubber components, preliminary analysis. | The simplest model; depends only on the first deviatoric invariant ((I_1)). |

| Mooney-Rivlin [28] | Phenomenological | Rubber-like materials, elastomers. | An extension of Neo-Hookean; includes a term with the second deviatoric invariant ((I_2)), often more accurate. |

| Yeoh [28] | Phenomenological | Carbon-black filled rubber, materials with large deformation. | Good for describing behavior at large strains and with limited experimental data. |

| Ogden [28] | Phenomenological | Very large deformations, complex stress states. | Models the response in terms of principal stretches; can be very accurate over a wide strain range. |

| Arruda-Boyce [28] | Micro-Mechanical | Polymers, elastomers. | An eight-chain model based on the statistical mechanics of polymer chains; accounts for network stretching. |

Experimental Protocol for Characterizing Soft Materials

This protocol outlines a general methodology for obtaining material parameters for hyperelastic models, which is also relevant for calibrating models for certain soft biological specimens.

1. Objective: To perform mechanical tests on a soft material specimen (e.g., rubber, tissue-engineered sample) to generate stress-strain data for calibrating a hyperelastic material model in FEA software.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Universal Testing Machine: Equipped with a load cell and environmental chamber if needed.

- Specimen Grips: Suitable for the test type (e.g., clamps for tensile tests, compression plates).

- Digital Image Correlation (DIC) System: Optional, for full-field strain measurement.

- Software: For machine control, data acquisition, and curve-fitting of hyperelastic models.

3. Procedure:

- Specimen Preparation: Prepare specimens according to relevant standards (e.g., ASTM D412 for rubber, custom geometries for tissue samples). Measure and record the exact dimensions of each specimen.

- Mechanical Testing: Perform at least two of the following three fundamental tests to capture different deformation modes. A strain rate of 1.0 mm/min is typical for quasi-static characterization [31].

- Uniaxial Tension: Clamp the specimen ends and extend it until failure or a target strain.

- Uniaxial Compression: Place the specimen between two plates and compress it.

- Planar Shear (or Biaxial Tension): Stretch a thin sheet of material along two perpendicular axes. This is highly valuable for capturing anisotropic behavior.

- Data Collection: Record force-displacement data for all tests. If using DIC, capture the full-field strain map.

- Data Processing:

- Convert force-displacement data into engineering or true stress-strain curves.

- Import the experimental stress-strain curves into your FEA software's material calibration module.

- Use the software's curve-fitting tool to fit various hyperelastic models (e.g., Mooney-Rivlin, Ogden, Yeoh) to the experimental data. The software will calculate the model parameters that provide the best fit.

4. Validation:

- Develop a simple FEA model of the test itself (e.g., a single element test or a model of the specimen).

- Assign the calibrated hyperelastic material to the model.

- Run the simulation and compare the FEA-predicted force-displacement response with the original experimental data. A good agreement, such as an average error of ~10% for modulus, validates the procedure [32].

Research Reagent and Material Solutions

The table below lists key materials and their functions in experimental mechanics and FEA, relevant to the field of material model development.

| Item | Function in Experiment/Simulation |

|---|---|

| Silicone Elastomers | Used as model materials for validating hyperelastic constitutive models due to their consistent, rubber-like properties. |

| Ti6Al4V Alloy Powder | Metal powder used in Powder Bed Fusion (e.g., EBAM, SLM) to fabricate porous lattice structures for mechanical testing and model validation [31]. |

| Formalin-Ethyl Acetate Solution | Used in the Formalin-ethyl acetate centrifugation technique (FECT) for stool sample preservation and parasite concentration, creating a specimen for mechanical analysis [33]. |

| Hybrid Finite Elements | Specialized elements (e.g., C3D8H in Abaqus) used to model incompressible or nearly incompressible materials like hyperelastic polymers and soft tissues [28]. |

Workflow for Material Model Selection and Troubleshooting

The diagram below outlines a logical pathway for selecting a material model and addressing common convergence problems.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary clinical outcome measures that can be validated through a pelvic floor FEA model? The retrovesical angle (RVA) and anorectad angulation (ARA) are key clinical metrics used to quantitatively validate the effectiveness of a finite element model of the pelvic floor. These angles are known to approach their normal physiological ranges when the model correctly simulates enhanced urinary and defecation control ability, for instance, after simulating targeted rehabilitation training. Comparing the model's output of RVA and ARA against clinical data is a standard method for verifying the model's biofidelity [34].

Q2: How can I objectively define "difficult stool consistencies" as a material in my FEA software? "Difficult stool consistencies," such as those representing constipation, are not single-point definitions but exist on a continuum. You can define them using the Bristol Stool Scale (BSS) and correlate this with quantitative minimal pressure (MP) values. Stool consistency can be directly measured as the gram-force required for a cylindrical probe to penetrate the stool sample by a specific depth. The following table summarizes this relationship, demonstrating that lower BSS types (indicating harder stools) correspond to exponentially higher minimal pressure values [35].

Table 1: Relationship Between Bristol Stool Scale and Measured Stool Hardness

| Bristol Stool Scale (BSS) Type | Description | Minimal Pressure (MP) Value Range |

|---|---|---|

| BSS 1-2 | Hard Stools (Constipation) | High MP, exponentially increasing as BSS decreases [35] |

| BSS 3-5 | Normal Stools | Intermediate MP, large variance within these categories [35] |

| BSS 6-7 | Soft/Loose Stools (Diarrhea) | Low MP [35] |

Q3: My model is not converging when simulating high intra-abdominal pressure (e.g., Valsalva maneuver). What could be the issue? This is often a problem of material properties and geometric non-linearity.

- Incorrect Tissue Properties: Ensure you are using appropriate hyperelastic material models (like Yeoh or Mooney-Rivlin) for soft tissues such as the levator ani muscle, external anal sphincter, and rectum. Using linear elastic models may not capture the large, nonlinear deformations accurately [34].

- Insufficient Mesh Refinement: The mesh in contact regions and areas of high stress concentration may be too coarse. Use curvature and proximity-based meshing functions to automatically refine the mesh in these complex geometric areas without making the entire model excessively large, which can help with both convergence and result accuracy [36].

Q4: How can I visualize the results of my simulation, such as stress distributions in the pelvic floor muscles? Use a symbol plot (also known as a vector plot). This visualization tool displays arrows on your model where the length represents the magnitude of a tensor or vector result (e.g., stress, strain) and the direction indicates its orientation. For tensor results like principal stress, arrowheads pointing toward the shaft typically represent compression, while arrowheads pointing away represent tension, allowing you to quickly identify areas of high mechanical load [37] [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Difficulty in Creating a Geometrically Accurate Pelvic Floor Model from Medical Scans

Solution: Follow a structured workflow for model creation and meshing.

Diagram 1: Pelvic Floor Model Creation

Key Steps:

- Image Acquisition: Obtain high-resolution CT (for bone geometry) and static/dynamic MRI (for soft tissue geometry and motion) scans with the participant in a supine position [34].