A Strategic Guide to DNA Barcode Region Selection for Parasite Identification in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting optimal DNA barcode regions for diverse parasite taxa.

A Strategic Guide to DNA Barcode Region Selection for Parasite Identification in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting optimal DNA barcode regions for diverse parasite taxa. It covers foundational principles of genetic marker variation, practical methodological applications for specific parasitic groups, strategies for troubleshooting common assay challenges, and rigorous validation techniques. By synthesizing current research, this guide aims to enhance the accuracy of parasite detection, genotyping, and phylogenetic studies, thereby supporting advancements in diagnostics, epidemiology, and therapeutic development.

The Genetic Landscape: Core Principles of DNA Barcoding for Parasites

DNA barcoding has emerged as a transformative tool in parasitology, providing a rapid, standardized method for species identification that complements traditional morphological approaches. This technique uses short, standardized genetic markers from a specific region of an organism's genome to facilitate species identification and discovery. The fundamental principle is that a specific DNA sequence can serve as a unique "barcode" to identify a species, much like a supermarket barcode identifies a product. For animal parasites, the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene has become the gold standard barcode region due to its high mutation rate, which provides sufficient genetic variation to distinguish between closely related species [1] [2].

The application of DNA barcoding is particularly valuable in parasitology for several reasons. Many parasites are small, have complex life cycles involving multiple hosts, and exist as assemblages of cryptic species complexes that are morphologically indistinguishable [1]. Traditional identification often requires specialized taxonomic expertise, which is becoming increasingly rare. DNA barcoding overcomes these challenges by providing a standardized, reproducible method that can be applied across all life stages of parasites, even from damaged or poorly preserved specimens [2]. This approach has proven successful for diverse parasites including coccidian parasites, malaria parasites, and their mosquito vectors [3] [2].

Selection of DNA Barcode Markers for Different Parasite Taxa

Selecting appropriate genetic markers is crucial for effective DNA barcoding of parasites. Different parasite groups require specific barcode regions due to variations in their evolutionary rates and genomic structures. The table below summarizes the primary barcode markers used for major parasite groups:

Table 1: Standard DNA Barcode Markers for Different Parasite Taxa

| Parasite Group | Primary Barcode Marker | Genomic Location | Key Characteristics | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Parasites (e.g., nematodes, ticks) | Cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) | Mitochondrial DNA | ~658 bp region; high inter-species variation; universal primers available | Mosquito identification [2], tick species identification |

| Apicomplexan Parasites (e.g., Eimeria, Plasmodium) | COI / SNP Panels | Mitochondrial DNA / Nuclear DNA | Provides more synapomorphic characters than 18S rDNA [3] | Species delimitation in coccidian parasites [3] |

| Malaria Parasites (Plasmodium falciparum) | 24-SNP or 96-SNP Barcodes | Nuclear DNA | Biallelic SNPs; minor allele frequency >0.10; independently segregating [4] | Genotyping in low-transmission areas; tracking parasite spread [4] |

| Malaria Parasites (Plasmodium vivax) | 146-SNP Barcode | Nuclear DNA | Locally tailored to capture population diversity; higher resolution than microsatellites [5] | High-resolution genomic surveillance in PNG [5] |

| Plant Parasites | rbcL + matK | Chloroplast DNA | Core-barcode for land plants; combination provides universality and discrimination [6] [7] | Identification of plant pathogens |

For animal parasites and their vectors, the COI gene has demonstrated exceptional utility. Research on mosquito species in Singapore achieved 100% success rate in identifying 45 species across 13 genera using COI barcoding, highlighting its reliability even in diverse taxonomic groups [2]. Similarly, for coccidian parasites, COI sequences have proven more reliable for species-specific identification than complete nuclear 18S rDNA sequences, providing better resolution for closely related species like Eimeria necatrix and Eimeria tenella [3].

For protozoan parasites like Plasmodium species, Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) barcodes have emerged as powerful tools. These consist of panels of neutral SNPs distributed throughout the genome that collectively genotype parasite strains. The development of these barcodes must follow specific criteria: they should be biallelic, have a minor allele frequency greater than 0.10, be independently segregating, work across various geographies, and be temporally stable [4]. A study on Plasmodium vivax in Papua New Guinea developed a 146-SNP barcode that provided higher resolution for measuring population genetics than traditional microsatellite markers [5].

Experimental Workflow for DNA Barcoding Parasites

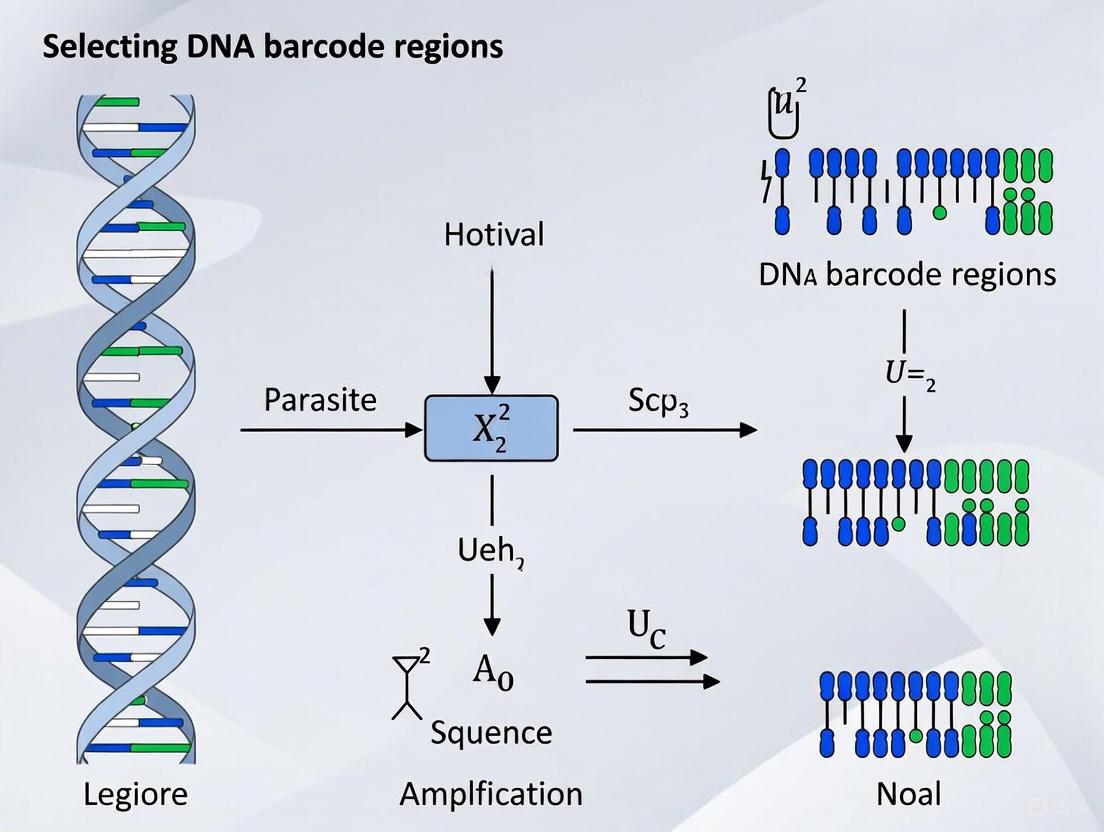

The following diagram illustrates the standard experimental workflow for DNA barcoding of parasites, from sample collection to species identification:

Diagram 1: DNA barcoding workflow for parasite identification

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experimental Steps

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

Proper sample collection and preservation are critical for successful DNA barcoding. For mosquito vectors, specimens should be collected using standardized methods such as BG-sentinel traps, CO₂ light traps, or human landing catches [2]. Parasite samples may be obtained from blood, tissues, or feces depending on the species. Voucher specimens should be preserved for morphological validation, ideally deposited in a recognized repository [2]. For DNA extraction, legs from one side of insect vectors can be used to preserve the morphological integrity of the voucher specimen [2]. Commercial DNA extraction kits (e.g., DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit, Qiagen) are commonly used, following manufacturer's protocols with modifications if necessary for specific sample types.

PCR Amplification of Barcode Regions

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the target barcode region requires careful optimization of primer selection and reaction conditions:

- Primer Design: For parasite COI amplification, primers such as forward 5'-GGATTTGGAAATTGATTAGTTCCTT-3' and reverse 5'-AAAAATTTTAATTCCAGTTGGAACAGC-3' have proven effective [2].

- Reaction Setup: A typical 50 μL PCR reaction contains 5 μL of extracted DNA, 1.5 mM MgCl₂, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 1× reaction buffer, 1.5 U Taq DNA polymerase, and 0.3 μM of each primer [2].

- Cycling Conditions: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 5 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 40 s), annealing (45°C for 1 min), and extension (72°C for 1 min), then 35 cycles with annealing at 51°C, and final extension at 72°C for 10 minutes [2].

For SNP barcoding of Plasmodium parasites, multiplex PCR approaches are employed to simultaneously amplify multiple target regions, followed by next-generation sequencing on platforms such as Illumina MiSeq [5].

Sequencing and Data Analysis

PCR products are purified and sequenced using Sanger sequencing for single specimens or next-generation sequencing for complex samples or SNP barcodes. Contiguous sequences are generated from forward and reverse chromatograms and aligned using software such as Clustal W algorithm in BioEdit [2]. Phylogenetic trees can be constructed using neighbor-joining algorithms in MEGA software with Kimura-2 parameter substitution model and bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates for robustness testing [2]. Species identification is performed by comparing unknown sequences to reference databases such as GenBank and the Barcode of Life Data Systems (BOLD) [2].

Troubleshooting Common DNA Barcoding Issues

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for DNA Barcoding Experiments

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions | Prevention Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| No PCR amplification | Inhibitor carryover, low template DNA, primer mismatch | Dilute template 1:5-1:10; add BSA; optimize annealing temperature; try mini-barcode primers [8] | Verify DNA quality (A260/280); amplify short QC locus first [8] |

| Smeared or non-specific bands | Excessive template DNA, low annealing stringency, primer-dimer formation | Reduce template input; optimize Mg²⁺ concentration; use touchdown PCR [8] | Validate primer specificity; optimize primer concentration [8] |

| Mixed peaks in Sanger sequences | Mixed template (multiple species), heteroplasmy, NUMTs, poor cleanup | Perform EXO-SAP or bead cleanup; re-sequence from diluted template; sequence both directions [8] | Use clonal specimens; validate with second locus for NUMTs [8] |

| Low reads in NGS | Over-pooling, adapter/primer dimers, low-diversity amplicons | Re-quantify with qPCR; repeat bead cleanup; spike PhiX (5-20%); review index design [8] | Use heterogeneity spacers; stringent size selection [8] |

| Contamination in controls | Aerosolized amplicons, template carryover, shared equipment | Separate pre-/post-PCR spaces; adopt dUTP/UNG carryover control; use fresh reagents [8] | Implement one-way workflow; dedicated pipettes; UV decontamination [8] |

| Multiclonal infections | Multiple parasite strains in same host | Use only single-clone infections; specialized tools for haplotype construction [4] | Develop population-specific SNP panels; whole genome sequencing [4] |

Advanced Troubleshooting: NUMTs and Mixed Infections

Nuclear Mitochondrial Sequences (NUMTs) present a particular challenge for COI barcoding, as these nuclear integrations of mitochondrial DNA can co-amplify and masquerade as mitochondrial sequences. Red flags include frameshifts, stop codons, unusual base composition, or conflicting forward/reverse calls [8]. To address this, researchers should translate reads to check for stop codons, cross-validate with a second locus, and if needed, clone the product or re-amplify with more specific primers [8].

For malaria parasites in moderate-to-high transmission settings, multiclonal infections present significant challenges, with some studies reporting approximately 80% of infections containing multiple parasite strains [4]. This results in a high proportion of mixed-allele calls that impede accurate haplotype construction. Potential solutions include using only single-clone infections for analysis (though this drastically reduces sample size) or employing specialized computational tools for haplotype reconstruction from mixed infections [4].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for DNA Barcoding Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) | High-quality DNA purification from diverse sample types | Effective for parasites and vectors; preserves voucher specimens [2] |

| PCR Additives | BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Reduces PCR inhibition from complex matrices | Critical for challenging samples; improves amplification [8] |

| Specialized Polymerases | Taq DNA Polymerase (Promega) | Amplification of barcode regions with fidelity | Standard for routine barcoding; balance of cost and reliability [2] |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina MiSeq | High-throughput sequencing for SNP barcodes | Enables multiplexed parasite genotyping [5] |

| Cleanup Kits | EXO-SAP, Purelink PCR Purification Kit | Removal of primers, dNTPs, enzymes post-amplification | Critical for clean sequencing results; reduces mixed peaks [2] |

| Carryover Prevention | UNG/dUTP System | Degrades contaminating amplicons from previous PCRs | Essential for high-throughput labs; prevents false positives [8] |

| Quantification Tools | Qubit Fluorometer, qPCR | Accurate DNA quantification for library preparation | Superior to spectrophotometry for NGS workflows [8] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: How much PhiX should be added for low-diversity amplicons in NGS? Follow the manufacturer's table for your platform. As a starting point, use 5-20% on MiSeq, and higher percentages on some NextSeq/MiniSeq workflows. Once Q30 scores stabilize, reduce PhiX to reclaim capacity [8].

Q2: What's the fastest way to distinguish inhibition from low template? Run a 1:5 dilution of the extract alongside the neat sample and add BSA. If the diluted lane yields a clean band while the neat lane fails, inhibition—not low input—is the culprit [8].

Q3: How can index hopping be reduced in multiplexed NGS runs? Adopt unique dual indexes, minimize free adapters with stringent cleanups, and monitor blanks and low-read wells. For suspect taxa, confirm with specimen-level barcoding [8].

Q4: How are NUMTs recognized in COI barcoding to avoid false IDs? Look for frameshifts or stop codons, odd GC content, and disagreement between forward and reverse reads. When in doubt, report at genus level and validate with a second locus [8].

Q5: Should UNG/dUTP carryover control be enabled by default? Yes—especially for high-throughput labs running amplicons across days. UNG/dUTP prevents carryover contamination while leaving native DNA unaffected. Heat-labile UNG variants help avoid residual activity downstream [8].

Q6: Why do universal SNP barcodes sometimes fail in high-transmission areas? Universal barcodes may suffer from ascertainment bias, where SNPs polymorphic in one population are not informative in others. In high-transmission areas with multiclonal infections, this is exacerbated by difficulties in haplotype phasing, reducing accuracy of population genetics analyses [4].

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are the universal criteria for selecting a DNA barcode region?

An ideal DNA barcode region must satisfy three primary criteria to be effective for species identification [9]:

- Significant Species-Level Variability: The region must contain enough genetic differences (a "barcoding gap") to distinguish between species, while being largely consistent within a species [9] [10].

- Universal PCR Amplification: It must possess conserved DNA sequences on its flanks that allow scientists to design PCR primers capable of amplifying the barcode from a wide range of target organisms [9] [10].

- Short Sequence Length: The region should be short enough to be easily sequenced with standard technology, even from degraded samples, but long enough to contain sufficient information. Typically, this is 400-800 base pairs [9].

FAQ 2: Why can't a single universal barcode, like COI for animals, be used for all parasites?

Different taxonomic groups have varying rates of evolution in different parts of their genomes [10].

- Animal barcoding successfully uses the mitochondrial COI gene because it evolves at a rate that provides good species-level discrimination [10].

- Plant barcoding requires chloroplast genes like

matKorrbcLbecause plant mitochondrial genes evolve too slowly [9] [10]. - Fungi and Protists (including many parasites) often use the ribosomal Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) region due to its high variability. For Apicomplexan parasites (e.g., Plasmodium, Babesia), the 18S rRNA gene is a common and effective barcode [11] [10].

The table below summarizes the recommended barcode regions for different organismal groups, with a focus on parasites.

| Organism Group | Commonly Used Barcode Gene(s) | Key Considerations for Parasite Research |

|---|---|---|

| Animals | Cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) [10] | Not suitable for most parasite taxa. |

| Plants | matK, rbcL, trnH-psbA [9] [10] |

Relevant for plant-borne parasites or their hosts. |

| Fungi | Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) [10] | Used for fungal parasites. |

| Apicomplexan Parasites(e.g., Plasmodium, Babesia) | 18S ribosomal RNA (18S rDNA) [11] | A highly conserved and reliable marker; the V4-V9 region provides excellent species resolution [11]. |

| Kinetoplastid Parasites(e.g., Trypanosoma, Leishmania) | 18S ribosomal RNA (18S rDNA) [11] | A suitable barcode; note that universal primers may have mismatches requiring validation [11]. |

FAQ 3: My barcode amplification from blood samples is inefficient due to host DNA contamination. How can I solve this?

Overwhelming host DNA is a common challenge in blood parasite research. You can employ blocking primers to selectively inhibit the amplification of the host's DNA [11].

- C3 Spacer-Modified Oligo: This is a primer with a sequence complementary to the host's 18S rDNA. A C3 spacer modification at its 3' end prevents the DNA polymerase from extending it, thus blocking the amplification of the host template [11].

- Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA) Oligo: PNA molecules bind more strongly to DNA than regular primers. A PNA oligo designed to bind the host's 18S rDNA physically blocks the polymerase from accessing and amplifying the host template [11].

Protocol: Using Blocking Primers for 18S rDNA Barcoding

- DNA Extraction: Perform standard DNA extraction from the whole blood sample.

- PCR Setup: Set up your PCR reaction with:

- Universal forward and reverse primers for the 18S rDNA V4-V9 region (e.g., F566 and 1776R) [11].

- The two blocking primers (C3-spacer and PNA) specific to the host (e.g., human) 18S rDNA.

- Amplification and Sequencing: Run the PCR. The blocking primers will suppress host DNA amplification, enriching the reaction for parasite DNA. Proceed with sequencing [11].

FAQ 4: My NGS barcode read counts do not accurately reflect the known abundances in my sample. What could be causing this quantification error?

Biases in PCR amplification are a major source of error in barcode quantification. Some barcodes may amplify more efficiently than others due to their specific sequence, leading to over- or under-representation in the final sequencing data [12].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Reduce PCR Cycle Number: Minimize the number of PCR cycles during library preparation to reduce amplification bias [12].

- Validate with Control Mixtures: Use control samples ("miniBulks") containing barcodes with known ratios to quantify the level of bias in your specific protocol [12].

- Optimize Barcode Design: Use barcodes of sufficient length and complexity (e.g., 32-nucleotide barcodes instead of 16) to improve accurate identification and reduce cross-talk between similar barcodes [12].

FAQ 5: How do I choose between a short and a long barcode region?

The choice involves a trade-off between sequencing capability and discriminatory power.

- Short Barcodes (<200 bp): Are ideal for degraded DNA or environmental (eDNA) samples. However, they may not provide sufficient information for reliable species-level identification, especially on error-prone sequencing platforms like nanopore [11].

- Long Barcodes (>1000 bp): Contain more informative sites, leading to higher species-level resolution. They are more robust for distinguishing between closely related parasite species. For example, using the V4-V9 region of 18S rDNA (~1.2 kb) was shown to outperform the shorter V9 region for parasite identification on a nanopore sequencer [11].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Barcoded Multiple Displacement Amplification (bMDA) for High-Coverage Spatial Genomics

This protocol is adapted from a 2023 study for amplifying genomes from low-input DNA, such as single cells or spatial microniches, in a high-throughput manner [13].

Principle: Replaces standard random hexamers in Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA) with barcoded primers, allowing multiple samples to be pooled before library preparation [13].

Key Reagent: Barcoded Primer (bB6N6)

- Sequence Structure: 5' Biotin modification - 6-nucleotide Cell Barcode - 6-nucleotide Random Hexamer (N6) [13].

- Function: The random hexamer binds to the template DNA for amplification by phi29 polymerase, while the cell barcode labels all amplified products from a single sample. The biotin tag allows for later pulldown and enrichment of barcoded products [13].

Methodology:

- Lysis and Amplification: Lyse individual cells or isolate DNA from spatial microniches. Perform the MDA reaction using a primer mix containing 1 μM bB6N6 and 49 μM standard N6 random hexamers. The high concentration of standard primers ensures efficient amplification, while the low concentration of barcoded primers is sufficient for labeling [13].

- Pooling: Pool the barcoded MDA products from different samples into a single tube.

- Barcoded Product Enrichment: Use streptavidin-coated beads to capture the biotin-tagged, barcoded DNA fragments.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Perform one-pot library construction on the enriched pool and sequence.

Protocol 2: Workflow for Parasite Detection and Identification from Blood Using 18S rDNA Barcoding

This workflow is designed for comprehensive detection of eukaryotic blood parasites using a portable nanopore sequencer [11].

Diagram Title: Parasite Detection via 18S rDNA Barcoding

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in DNA Barcoding |

|---|---|

| Universal PCR Primers(e.g., F566 & 1776R) | Designed to bind to conserved regions flanking a variable barcode region (e.g., 18S rDNA V4-V9), enabling amplification across a wide range of taxa [11]. |

| Blocking Primers(C3-spacer & PNA) | Used to suppress the amplification of non-target DNA (e.g., host 18S rDNA in blood samples), thereby enriching the target parasite signal [11]. |

| Barcoded MDA Primers(e.g., bB6N6) | Allows for high-throughput, multiplexed whole-genome amplification by tagging DNA from each sample with a unique barcode sequence, enabling sample pooling [13]. |

| Phi29 DNA Polymerase | Enzyme used in Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA). It provides high-fidelity, isothermal amplification of whole genomes from low-input DNA [13]. |

| Curated Barcode Reference Library(e.g., BOLD, GenBank) | A database of validated barcode sequences from authoritatively identified specimens. Essential for comparing and identifying unknown sequences from experiments [10]. |

For researchers in parasitology and drug development, selecting the appropriate genetic marker is a critical first step that can determine the success of a study. Genetic markers are essential tools for species identification, phylogenetic analysis, and population genetics. This technical support guide provides an overview of five common markers—18S rRNA, COI, COII, Cytb, and Microsatellites—framed within the context of parasite research. Below, you will find a comparative summary, a logical workflow for marker selection, troubleshooting guides for common experimental challenges, and a list of essential research reagents.

Comparison of Molecular Markers

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, applications, and limitations of each marker to help inform your selection.

| Marker | Type & Location | Primary Applications in Parasitology | Key Strengths | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18S rRNA | Nuclear ribosomal RNA gene | - Diversity screening of protists (e.g., Hepatozoon, Theileria) [14].- Phylogenetics for higher-level taxonomy. | - Highly conserved, useful for broad taxonomic groups [14].- Universal primers available [14]. | - Limited species-level resolution for closely related taxa [15].- Results can vary significantly with primer choice [14]. |

| COI | Mitochondrial protein-coding gene | - Species-level barcoding for mosquitoes, sandflies, and other arthropods [16] [15].- Identification of cryptic species. | - Strong discriminatory power for many metazoans [16].- Extensive reference databases (e.g., BOLD). | - Can fail in some taxa (e.g., some Anopheles) [16].- Risk of co-amplifying NUMTs (nuclear mitochondrial sequences) [8]. |

| Cytb | Mitochondrial protein-coding gene | - Species identification of sandflies and other parasites [15].- Population genetics studies. | - High interspecific divergence, good for closely related species [15].- Often performs better than COI for specific taxa. | - Smaller public database compared to COI.- Requires validation for new parasite groups. |

| Microsatellites | Nuclear, repetitive non-coding DNA | - Kinship and parentage analysis [17].- High-resolution population genetics.- Assessing genetic diversity in cultured stocks. | - Hypervariable, offering the highest resolution power for individuals [17].- Multi-locus approach increases power. | - Laborious development for new species [17].- Not suitable for species identification alone. |

| COII | Mitochondrial protein-coding gene | - Phylogenetic studies of insect vectors. | - Useful for resolving evolutionary relationships within genera. | - Less commonly used as a standalone barcode compared to COI/Cytb; reference data may be sparse. |

Selecting a Marker: A Researcher's Workflow

The following diagram outlines a logical decision pathway to guide your selection of a genetic marker based on your primary research objective.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

PCR Failure Playbook

| Symptom | Likely Causes | Recommended Fixes |

|---|---|---|

| No band or faint band on gel | - Inhibitor carryover from extraction (e.g., polyphenols, fats).- Low DNA template concentration.- Primer mismatch. | - Dilute DNA template 1:5–1:10 to reduce inhibitors [8].- Add BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) to the PCR mix [8].- Optimize annealing temperature and cycle number. |

| Smears or non-specific bands | - Excessive DNA template.- Low annealing stringency.- Primer-dimer formation. | - Reduce the amount of input DNA [8].- Optimize Mg²⁺ concentration and annealing temperature [8].- Use touchdown PCR protocols. |

| Clean PCR but messy Sanger trace (double peaks) | - Mixed template (e.g., contamination, parasite/host mix).- Incomplete purification of PCR products.- NUMTs (for COI). | - Re-sequence from a diluted template [8].- Perform rigorous cleanup (e.g., EXO-SAP, bead purification) [8].- Sequence both directions; validate with a second locus [8]. |

Sequencing & Contamination FAQs

FAQ 1: How do I recognize and avoid false IDs from NUMTs in COI barcoding?

- Answer: Look for frameshifts, premature stop codons, unusual GC content, and disagreement between forward and reverse reads [8]. When NUMTs are suspected, report identification at the genus level and confirm with a second, independent locus (e.g., Cytb or 18S rRNA) [8].

FAQ 2: Our Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) run for amplicons yielded very low reads. What can we do?

- Answer: Low reads can result from over-pooling, adapter dimers, or low library diversity. Re-quantify libraries with fluorometry or qPCR. Perform bead cleanups to remove dimers and spike in a higher percentage of PhiX control (e.g., 5-20%) to improve cluster diversity on the flow cell [8].

FAQ 3: We see contamination in our negative controls. How do we regain a clean workflow?

- Answer: Immediately quarantine the affected batch. Physically separate pre-PCR and post-PCR workspaces. Use dedicated equipment and PPE. Incorporate chemical carryover control by using dUTP in PCR mixes and treating with Uracil-DNA Glycosylase (UNG) prior to amplification to degrade contaminating amplicons from previous runs [8]. Always include extraction blanks and no-template controls (NTCs) in every batch [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and their functions for successful DNA barcoding and marker analysis experiments.

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit | High-quality DNA extraction from diverse sample types. | Standard for extracting DNA from parasite vectors and tissues; effective for removing inhibitors [14] [16]. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | PCR additive to neutralize common inhibitors. | Critical for amplifying samples contaminated with polyphenols (plants) or humic substances (soil/sediments) [8]. |

| UNG (Uracil-DNA Glycosylase) & dUTP | Chemical system for preventing amplicon carryover contamination. | Replaces dTTP with dUTP in PCR; UNG enzyme degrades contaminating uracil-containing amplicons before the run, ensuring workflow cleanliness [8]. |

| PhiX Control Library | Sequencing control for low-diversity amplicon libraries. | Spiked into NGS runs (5-20%) to provide nucleotide diversity, which is essential for optimal cluster recognition and sequencing quality on Illumina platforms [8]. |

| Validated Primer Sets | Amplification of specific barcode regions (e.g., COI, 18S V4/V9). | Using previously validated primers for your target clade (e.g., from published parasitology studies) reduces trial-and-error and ensures specificity [14] [8]. |

For researchers studying parasite taxa, selecting the appropriate DNA barcode region is a critical first step that can determine the success of a study. This technical support guide addresses the core challenge in DNA barcoding: finding a genetic sequence that displays sufficient interspecific divergence to distinguish between species, while maintaining enough intraspecific conservation to reliably identify members of the same species. The ideal barcode region must satisfy three key criteria: contain significant species-level genetic variability, possess conserved flanking sites for developing universal PCR primers, and have a short sequence length to facilitate DNA extraction and amplification [9]. This guide provides troubleshooting and methodological support for navigating these requirements in your parasite research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the primary genetic markers used for DNA barcoding across different taxa?

The standard barcode markers vary significantly between kingdoms. The table below summarizes the most commonly used markers.

Table 1: Standard DNA Barcode Markers for Different Organism Groups

| Organism Group | Primary Barcode Marker(s) | Alternative Markers | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animals | Mitochondrial COI (Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I) [18] [16] | 16S rRNA, 18S rRNA, cyt b [16] | Highly effective; universal primers available [9] [16]. |

| Plants | matK, rbcL, trnH-psbA [9] | ITS (Internal Transcribed Spacer) | COI is not effective in plants [9]. Multi-locus approach often required. |

| Fungi | ITS [18] | COI (for some genera, e.g., Penicillium) [18] | COI can have low resolution or practical issues like introns [18]. |

Why did my barcoding experiment fail to amplify or sequence the target gene?

Amplification and sequencing failures are common. The table below outlines potential causes and solutions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting PCR Amplification and Sequencing Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No PCR Amplification | Primer mismatch, degraded DNA, inhibitory contaminants in sample. | - Design degenerate primers to account for genetic variation [18].- Check DNA quality via gel electrophoresis.- Dilute or purify DNA template to remove inhibitors. |

| Poor-Quality Sequences | Mixed-species samples, low DNA concentration. | - Ensure specimen is a single individual.- Increase template concentration or perform nested PCR [18]. |

| Marker Fails to Discriminate Species | Insufficient interspecific variation in chosen marker; cryptic species complex. | - Employ a multi-locus barcoding approach [19] [16].- Try an alternative, more variable marker (see Table 1). |

How do I handle a sample with degraded or processed DNA?

For samples where DNA is fragmented (e.g., processed foods, ancient specimens, or environmental samples), the standard ~650 bp barcode region may be too long to amplify reliably [18].

- Solution: Use a mini-barcode approach. Design primers to amplify a shorter fragment (e.g., <300 bp) within the standard barcode region. This method has been shown to recover a significantly higher proportion of sequence data from compromised samples [18].

My analysis reveals deep genetic splits within a single morphospecies. What does this mean?

A deep barcode divergence within a recognized species can indicate two main possibilities:

- Cryptic Species Diversity: The morphospecies actually comprises two or more distinct biological species that are genetically isolated but morphologically similar [19] [20]. This is a common discovery in barcoding studies.

- High Intraspecific Variation: The population may exhibit exceptionally high levels of genetic diversity.

- Next Steps: This finding should be treated as a hypothesis. Follow an integrated taxonomic approach [19]:

- Re-examine morphological specimens for subtle diagnostic characters.

- Analyze ecological data (e.g., host specificity, geographic distribution).

- Sequence additional, independent genetic markers (nuclear or mitochondrial) to confirm the initial barcode result [19].

Experimental Protocols

Standard Protocol: DNA Barcoding for Specimen Identification

This protocol outlines the core workflow for specimen identification using DNA barcoding, adaptable to various parasite taxa.

Workflow: DNA Barcoding for Identification

DNA Extraction

- Procedure: Extract total genomic DNA from tissue samples (e.g., parasite fragments, leg muscles for mosquitoes) using a commercial DNA extraction kit (e.g., DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit) [16]. For voucher specimen preservation, non-destructive methods, such as extracting from a subset of legs, are recommended [16].

- Troubleshooting: Always preserve a part of the specimen as a voucher (e.g., in 70-99.5% ethanol [20]). Vouchers are essential for validating results and re-examining morphology [19].

PCR Amplification

- Procedure: Amplify the barcode region using universal or taxon-specific primers. A typical 50 µL PCR reaction includes extracted DNA, primers, dNTPs, reaction buffer, and Taq DNA polymerase [16].

- Thermocycling Conditions (Example):

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 5 min.

- 5 cycles of: 94°C for 40 s, 45°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min.

- 35 cycles of: 94°C for 40 s, 51°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 10 min [16].

Sequencing and Analysis

- Procedure: Purify PCR products and perform Sanger sequencing [16].

- Bioinformatics:

- Assemble forward and reverse sequences into a contig.

- Align sequences using algorithms like Clustal W in software such as BioEdit or MEGA [16].

- Calculate pairwise genetic distances (e.g., using Kimura-2 parameter model) [16].

- Construct a phylogenetic tree (e.g., Neighbor-Joining tree with 1000 bootstrap replicates) to visualize species clustering [16].

- Compare the generated barcode sequence against reference databases like the Barcode of Life Data System (BOLD) or GenBank [19] [16].

Advanced Protocol: Multi-Locus Barcoding for Complex Taxa

For parasite groups where a single marker lacks resolution (e.g., species complexes or fungi), a multi-locus approach is necessary.

Workflow: Multi-Locus Barcoding

- Principle: This method integrates data from multiple genetic markers, often including both mitochondrial and nuclear genes, to build a more robust picture of species boundaries [19] [16].

- Typical Workflow:

- Select 2-3 candidate barcode loci suitable for your parasite taxon (see Table 1).

- Perform PCR amplification and sequencing for each locus independently.

- Analyze the datasets both separately (to check for concordant patterns) and as a concatenated sequence.

- Integrate the genetic results with morphological re-examination and ecological data (e.g., host specificity) to test species hypotheses [19]. This integrated taxonomy approach is considered the gold standard [19].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for DNA Barcoding Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Universal COI Primers | Primer pairs (e.g., LCO1490/HCO2198) designed to amplify the ~658 bp barcode region across diverse animal taxa. | Initial screening for animal and parasite species identification [16]. |

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) | Silica-membrane-based protocol for high-quality DNA extraction from various tissue types. | Standardized DNA extraction from parasite specimens [16]. |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Enzyme for PCR amplification, typically supplied with MgCl₂ and reaction buffer. | Core component of PCR mix for amplifying the barcode region [16]. |

| BOLD Systems Database | A dedicated portal for assembling, validating, and visualizing DNA barcode data. | The primary database for comparing and identifying animal barcodes [19] [9]. |

| MEGA Software | An integrated tool for sequence alignment, genetic distance calculation, and phylogenetic tree building. | Conducting all core bioinformatic analyses of barcode sequences [16]. |

| Ethanol (70-99.5%) | For preservation of voucher specimens and collected parasite material. | Prevents DNA degradation and preserves morphology for future study [20]. |

Taxon-Specific Strategies: Selecting the Right Marker for the Job

The 18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene serves as a powerful molecular barcode for the detection, identification, and phylogenetic analysis of apicomplexan parasites. Its conserved regions allow for the design of universal primers, while variable domains provide the species-level resolution necessary for differentiating closely related organisms like Plasmodium, Babesia, and Theileria. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and frequently asked questions to assist researchers in optimizing their use of the 18S rRNA gene in experimental protocols, from primer selection to data interpretation.

Primer Selection and 18S rRNA Gene Region Comparison

Which region of the 18S rRNA gene should I target for my specific research question?

The choice of target region within the 18S rRNA gene involves a trade-off between breadth of taxonomic coverage, resolution power, and technical constraints. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of commonly used regions.

Table 1: Comparison of 18S rRNA Gene Target Regions for Apicomplexan Parasite Detection

| Target Region | Approximate Amplicon Length | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V9 | ~100-200 bp | Short length suitable for degraded DNA; widely used in metabarcoding studies [21]. | Limited species-level resolution; higher misidentification rates with error-prone sequencing (e.g., nanopore) [11]. | Initial, high-throughput screening of diverse eukaryotic communities [21]. |

| V4 | ~380-400 bp [21] | A common metabarcoding region offering a good balance between length and information content [21]. | May not reliably differentiate all closely related Babesia or Theileria species. | General eukaryote diversity studies and parasite screening [21] [14]. |

| V4-V9 (Long Range) | >1000 bp [11] | High phylogenetic resolution for accurate species identification; superior performance on error-prone sequencing platforms [11]. | Technically challenging to amplify from low-quality/quantity DNA; more susceptible to host DNA amplification in blood samples [11]. | Definitive species identification and phylogenetic studies, especially with nanopore sequencing [11]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: My universal 18S rRNA PCR from blood samples is dominated by host DNA, masking parasite signal. How can I suppress host amplification?

Challenge: Universal eukaryotic primers co-amplify the abundant 18S rRNA gene from the host (e.g., human, cattle), which can overwhelm the signal from the target parasite DNA, reducing sensitivity [11].

Solutions:

- Use Blocking Primers: Design sequence-specific oligonucleotides that bind to the host 18S rRNA gene and prevent its amplification during PCR.

- C3 Spacer-Modified Oligos: A blocking primer is designed to overlap with the binding site of the universal reverse primer on the host DNA. A C3 spacer at the 3'-end irrevocably blocks polymerase extension. This primer competes with the universal primer for host DNA [11].

- Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA) Clamps: PNA oligomers bind to the host 18S rRNA sequence with high affinity and specificity, physically obstructing DNA polymerase and inhibiting host DNA amplification. PNA clamps can be used in combination with C3 spacer oligos for enhanced suppression [11].

- Protocol: Combining Blocking Primers with V4-V9 Amplification [11]

- Primer Sequences:

- Forward Primer (F566): 5′- CCT GCN TTG TCA CGA C -3′

- Reverse Primer (1776R): 5′- CCA AGC TCC ACC TAC GGA -3′

- Blocking Primer (Example for host suppression): A custom oligo designed against the host's 18S rRNA sequence with a 3' C3 spacer.

- Reaction Setup: Include the universal primers (F566 and 1776R) at standard concentrations (e.g., 0.2-0.4 µM) and add the host-specific blocking primer(s) at a higher concentration (e.g., 1-2 µM) to outcompete the universal primers for host template binding.

- PCR Conditions: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min; 35-40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55-60°C for 30 s, 72°C for 90 s; final extension at 72°C for 5 min.

- Primer Sequences:

FAQ 2: My nanopore sequencing data for the 18S rRNA gene has a high error rate, leading to ambiguous species assignment. How can I improve accuracy?

Challenge: Portable nanopore sequencers have higher per-base error rates than platforms like Illumina, which can lead to misclassification of species, particularly with short barcodes [11].

Solutions:

- Target a Longer Barcode Region: As demonstrated in Table 1, using a long amplicon spanning the V4 to V9 regions (>1 kb) provides significantly more sequence information, which improves the accuracy of species identification despite sequencing errors [11].

- Optimize Bioinformatics Parameters: When using BLAST for classification, avoid the default

-task megablastwhich is for highly similar sequences. Use-task blastnfor more sensitive searching of somewhat similar sequences, which is more tolerant of errors [11]. Adjusting alignment thresholds (e.g., query coverage >85%, identity >85%) is also crucial for filtering reliable hits [21]. - Utilize Alternative Classification Methods: For error-containing reads, the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) naïve Bayesian classifier can be a robust alternative to BLAST, though the proportion of unclassified sequences may increase with the error rate [11].

FAQ 3: How can I rapidly differentiate between multiple Babesia species in my clinical samples without sequencing?

Challenge: Sequencing is time-consuming and costly for routine diagnostics or large-scale screening where only specific species need to be identified.

Solution: High-Resolution Melting (HRM) Analysis HRM is a post-real-time PCR technique that detects differences in the melting behavior of amplicons based on their GC content, length, and sequence.

- Protocol: RT-PCR-HRM for Bovine Babesia Species [22]

- Primer Design: Design primers to amplify a region of the 18S rRNA gene known to have sequence variation among your target species (e.g., B. bovis, B. bigemina, B. major, B. ovata).

- Reaction Mix:

- 10 µL of 2X HRM master mix (containing dsDNA-binding dye).

- 2 pmol of each forward and reverse primer.

- 1 µL of template DNA (10-50 ng).

- Add nuclease-free water to 20 µL.

- PCR and HRM Cycling:

- Amplification: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 30 s.

- HRM: Denature at 95°C for 1 min, cool to 40°C for 1 min, then gradually heat from 65°C to 95°C, incrementally by 0.1°C, with continuous fluorescence acquisition.

- Analysis: The resulting melting curves and peak temperatures (Tm) are compared to reference standards. Each Babesia species will generate a distinct, reproducible melting profile, allowing for discrimination [22].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for 18S rRNA-Based Apicomplexan Research

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Example Use Case | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Universal 18S rRNA Primers (F566 & 1776R) | Amplification of the V4-V9 region for high-resolution barcoding. | Sensitive detection and species identification of diverse blood parasites (Trypanosoma, Plasmodium, Babesia) using long-read sequencing [11]. | [11] |

| Host-Blocking Primers (C3/PNA) | Selective inhibition of host (mammalian) 18S rRNA gene amplification during PCR. | Enriching parasite DNA in blood samples for metagenomic studies, significantly improving detection sensitivity [11]. | [11] |

| Whatman FTA Cards | Room-temperature storage and preservation of DNA from field-collected blood samples. | Simplifying sample collection, transport, and storage for DNA barcoding of fish blood apicomplexans [23]. | [23] |

| Abbott m2000sp/m2000rt System | Automated extraction and qRT-PCR for high-throughput, clinical-grade pathogen detection. | Qualified, FDA-recognized measurement of Plasmodium 18S rRNA in controlled human malaria infection trials [24]. | [24] |

| Forget-Me-Not qPCR Master Mix | Optimized dye chemistry for High-Resolution Melting (HRM) analysis. | Discriminating between four bovine Babesia species based on 18S rRNA melting profiles [22]. | [22] |

Experimental Workflow Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for detecting apicomplexan parasites using the 18S rRNA gene, highlighting key decision points.

General Workflow for 18S rRNA-Based Detection of Apicomplexan Parasites

The following diagram details a specific, advanced workflow for using nanopore sequencing with host DNA blocking.

Nanopore Sequencing Workflow with Host DNA Blocking

FAQ: Selecting Genetic Markers for Kinetoplastid Typing

Q1: What are the core technical differences between mitochondrial genes and the mini-exon gene as genetic markers?

A1: The fundamental differences lie in their genomic location, inheritance patterns, and molecular characteristics, which directly influence their applicability for different research objectives.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Mitochondrial Genes vs. Mini-Exon Gene

| Feature | Mitochondrial Genes | Mini-Exon Gene |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Location | Mitochondrial kinetoplast (kDNA) [25] | Nuclear genome, organized in tandem repeats [26] [27] |

| Inheritance | Uniparental (clonal) [28] | Biparental in hybrids [28] |

| Copy Number | Multiple copies per cell (e.g., in maxicircles) [27] | High (~250 copies per cell) as a tandem repeat [26] |

| Key Function | Essential mitochondrial proteins (e.g., Cytochrome c oxidase) [28] | Donor of the Spliced Leader (SL) sequence trans-spliced onto all mRNAs [26] [27] |

Q2: For identifying and discriminating Trypanosoma cruzi DTUs, which marker is more reliable?

A2: Recent next-generation sequencing (NGS) studies conclude that single-copy nuclear genes are the gold standard for robust T. cruzi Discrete Typing Unit (DTU) identification [29].

While the mini-exon gene's intergenic region has been widely used for its sensitivity, its use for phylogenetics and unequivocal DTU identification is now advised against. NGS data reveals that sequences from strains of the same DTU (e.g., TcII, TcIII, TcIV, TcV, TcVI) can scatter across different clusters in a phylogenetic tree, leading to misidentification [29]. In contrast, mitochondrial genes like cox1 can discriminate T. cruzi from closely related species and identify DTUs TcI-TcIV, but often cannot separate the hybrid DTUs TcV and TcVI, which cluster with their parental groups TcIII and TcIV [29] [28].

Q3: What is a key advantage of mitochondrial genes in studying hybrid strains?

A3: Mitochondrial genes are indispensable for detecting mitochondrial introgression and heteroplasmy in hybrid strains [29]. Because mitochondrial DNA is uniparentally inherited, sequencing mitochondrial markers allows researchers to trace the maternal lineage of a hybrid, providing a critical piece of the genetic history that nuclear markers alone cannot reveal [28].

Q4: My mini-exon PCR and sequencing results are ambiguous or uninterpretable. What could be wrong?

A4: The repetitive nature and potential intra-array sequence variation of the mini-exon locus can cause issues [27]. Below is a troubleshooting guide for common problems.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Mini-Exon Experiments

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple or smeared bands on gel | Heterogeneity within the mini-exon tandem repeats; non-specific PCR amplification [27] | Gel-purify the band of expected size, clone the PCR product, and sequence multiple clones to assess diversity [30]. |

| Poor sequencing chromatogram | Variation among mini-exon repeat units creating overlapping signals [27] | Clone the PCR product to isolate individual repeat units for Sanger sequencing, or use NGS to resolve all haplotypes [29]. |

| Inability to discriminate DTUs | The mini-exon sequence for your target species/DTU lacks sufficient resolution [29] | Switch to a more discriminative marker, such as a single-copy nuclear gene (e.g., GPI) or the mitochondrial cox1 gene [29] [28]. |

| Low PCR sensitivity | Low parasite load in the sample. | The multi-copy nature of the mini-exon gene is a key advantage here [29]. Optimize PCR conditions (annealing temperature, Mg2+ concentration) and consider a nested PCR approach. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Trypanosoma cruzi Strain Typing Using Mitochondrialcox1Gene and NuclearGPIGene

This combined protocol, adapted from research, allows for robust species and DTU identification and can reveal hybrid genotypes through the comparison of uniparentally (mitochondrial) and biparentally (nuclear) inherited markers [28].

1. DNA Extraction

- Use a standard phenol-chloroform method or commercial kit to obtain high-quality genomic DNA from parasite culture, triatomine vectors, or host blood.

2. PCR Amplification

- Mitochondrial Barcode (cox1): Amplify a fragment of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene.

- Primers: Use universal primers or those specific for trypanosomatids [28].

- Reaction Mix: 1x PCR buffer, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.2 µM each primer, 1 U of Taq polymerase, and ~50 ng of DNA template.

- Cycling Conditions: Initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min; 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 50-55°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min; final extension at 72°C for 7 min.

- Nuclear Gene (GPI): Amplify a fragment of the glucose-6-phosphate isomerase gene.

- Primers and Protocol: As established in previous multilocus studies [28].

3. Sequencing and Analysis

- Purify PCR products and perform Sanger or NGS sequencing.

- Analyze sequences: Generate phylogenetic trees (using Maximum Likelihood, Bayesian inference) with reference sequences. Calculate pairwise genetic distances and perform species delimitation tests (e.g., Automatic Barcode Gap Discovery) [28].

- Identify Hybrids: Compare the phylogenetic placement of your sample in the cox1 (maternal) tree versus the GPI (nuclear) tree. Incongruence can indicate a hybrid origin [28].

Protocol 2: Assessing Mini-Exon Gene Array Variation Using NGS

This protocol is crucial for moving beyond single-sequence assumptions and fully characterizing the mini-exon locus [27] [29].

1. Library Preparation and NGS

- Design primers to amplify a substantial portion of the mini-exon intergenic region.

- Prepare a sequencing library from the purified PCR product. The use of inline indices and Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) is recommended to track samples and correct for PCR errors [31].

2. Bioinformatic Processing

- Extraction & Demultiplexing: Extract barcode (mini-exon) sequences from raw reads using alignment-based or regular expression-based tools. Demultiplex samples based on indices [31].

- Error Correction: Use error-correction pipelines designed for barcode data to account for sequencing errors and PCR artifacts. UMIs are critical for distinguishing true biological variation from amplification errors [31].

- Haplotype Analysis: Cluster the error-corrected sequences to identify all distinct mini-exon haplotypes present in the array for a given strain.

Diagram 1: NGS workflow for mini-exon array analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Kinetoplastid Gene-Based Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Primers (e.g., for cox1, GPI, mini-exon) | PCR amplification of target barcode regions. | Primer design must be validated for the specific kinetoplastid genus under study [28]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Accurate amplification for sequencing. | Reduces PCR-derived errors in the final sequence data. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Tagging individual DNA molecules to correct for PCR and sequencing errors. | Critical for accurate haplotyping in NGS studies of multi-copy genes [31]. |

| Reference Strain Collections (e.g., COLTRYP) | Positive controls and phylogenetic reference. | Essential for validating typing protocols and providing context for new isolates [28]. |

| Bioinformatic Pipelines (e.g., for error correction, phylogenetics) | Processing raw NGS data, building phylogenetic trees. | Pipelines designed for barcode data are superior to generic ones [31]. Tools for species delimitation (e.g., ABGD) are also key [28]. |

| TDR Drug Discovery Database (tdrtargets.org) | Identifying potential drug targets in kinetoplastid genomes. | A resource that leverages genomic data for applied drug development [27]. |

The small subunit ribosomal RNA gene (18S rDNA) serves as a powerful DNA barcode for the identification and characterization of eukaryotic microorganisms, including intestinal protists like Blastocystis and Giardia [32] [33]. This genetic region contains a unique combination of highly conserved sequences, suitable for designing universal primers, and variable regions, which provide the phylogenetic signal necessary for species-level differentiation and subtyping [32] [34]. The application of 18S rDNA barcoding has become a cornerstone in modern parasitology, enabling high-throughput screening, resolution of genetic diversity, and insights into the epidemiology of these common gut protists [35] [36].

Key Experimental Protocols

Subtyping Blastocystis sp. via 18S rDNA Barcode Region Sequencing

Principle: This method involves the amplification and sequencing of a ~600 bp fragment of the 18S rDNA gene, known as the "barcode region," to identify Blastocystis subtypes (STs) with high accuracy and sensitivity [34] [36].

Procedure:

- DNA Extraction: Use a commercial stool DNA extraction kit (e.g., EasyPure Stool Genomic DNA kit) on fecal samples. Include a bead-beating step for efficient cell lysis [35].

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the barcode region using Blastocystis-specific primers. A standard PCR reaction mix includes:

- 10 μL of 2x Pro Taq buffer

- 0.8 μL of forward primer (5 μM)

- 0.8 μL of reverse primer (5 μM)

- Template DNA (up to 10 ng/μL)

- Nuclease-free water to a final volume of 20 μL Thermal cycling conditions: 95°C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, 72°C for 45 s; final extension at 72°C for 10 min [35].

- Sequencing and Analysis: Purify PCR products and perform Sanger sequencing. Analyze the resulting sequences using bioinformatics tools like BLAST against reference databases to assign subtypes [34].

Comprehensive Parasite Detection in Fecal Samples using 18S rDNA NGS

Principle: Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) of the 18S rDNA V3-V4 regions allows for the simultaneous detection and relative quantification of a broad spectrum of gastrointestinal parasites in a single assay [35].

Procedure:

- Library Preparation: Amplify the V3-V4 hypervariable regions of the 18S rDNA gene using universal eukaryotic primers (e.g., F: CCAGCASCYGCGGTAATTCC and R: ACTTTCGTTCTTGATYRA) [35].

- Illumina Sequencing: Pool the purified amplicons in equimolar amounts and perform paired-end sequencing (e.g., 2x300 bp) on an Illumina MiSeq or similar platform following standard protocols [35].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Control: Process raw FASTQ files with tools like fastp to remove low-quality reads and adapters.

- Clustering: Merge paired-end reads and cluster sequences into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) at a 97% similarity threshold using software like USEARCH.

- Taxonomy Assignment: Classify OTUs by comparing representative sequences to a curated 18S rDNA database using an RDP Classifier [35].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for NGS-based parasite detection using the 18S rDNA barcode:

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ Table: Addressing Common 18S Barcoding Challenges

| Question | Answer & Solution |

|---|---|

| Why is my parasite detection sensitivity low in bacteria-rich samples (e.g., feces)? | Widely-used 18S rDNA primers can non-specifically amplify abundant bacterial 16S rDNA, overwhelming the signal from rare eukaryotes. Solution: Use newly designed primer sets with higher specificity for eukaryotic 18S rDNA to minimize bacterial co-amplification [32]. |

| My subtyping results for Blastocystis are inconsistent. Which method is most reliable? | Sequencing of the SSU-rDNA barcode region is recommended over Sequence-Tagged-Site (STS) PCR. STS primers can have moderate sensitivity and may miss some infections, while sequencing provides higher applicability, sensitivity, and yields data useful for further research [34]. |

| How can I detect multiple parasite species or mixed subtype infections in a single sample? | Conventional Sanger sequencing often misses low-abundance subtypes. Solution: Employ Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) of the 18S rDNA, which offers heightened sensitivity and specificity for characterizing mixed infections and uncovering full subtype diversity [36]. |

| How do I handle high host DNA background when detecting blood parasites? | Host 18S rDNA can dominate the sequencing library. Solution: Use blocking primers (C3-spacer modified oligos or Peptide Nucleic Acids - PNAs) that bind specifically to host 18S rDNA and inhibit its amplification during PCR, thereby enriching for parasite sequences [37]. |

| Can I use the 18S barcode for other parasites, like tick-borne protists? | Yes, DNA barcoding with 18S rRNA gene fragments (e.g., V4, V9 regions) is a valuable tool for screening the diversity of protists in various samples, including ticks. However, results can vary by primer set, and findings should be validated with PCR [14]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for 18S rDNA-Based Protist Research

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Stool DNA Extraction Kit (e.g., EasyPure Stool Genomic DNA Kit) | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA from complex fecal samples. | Kits incorporating a bead-beating step are crucial for efficient lysis of robust protist cysts [35]. |

| Eukaryote-Specific 18S rDNA Primers | PCR amplification of the target barcode region from eukaryotic templates. | Select primers with high taxonomic coverage for your target parasites and low similarity to bacterial 16S rDNA to reduce contamination [32]. |

| Host-Blocking Primers (C3 spacer / PNA) | Suppression of host (e.g., human, mammal) 18S rDNA amplification in PCR. | Essential for enriching parasite DNA in samples with high host cell content, such as blood or tissue biopsies [37]. |

| Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) MinION | Long-read sequencing platform for generating full-length (~1800 bp) 18S rDNA sequences. | Provides high-resolution data for robust phylogenetic analysis and confident discovery of novel subtypes [36]. |

| Illumina MiSeq System | Short-read sequencing platform for high-throughput, deep sequencing of 18S rDNA amplicons (e.g., V3-V4 regions). | Ideal for community diversity studies and detecting multiple co-infecting parasites or subtypes within a single sample [35] [36]. |

Data Presentation and Comparison

Table: Performance Comparison of Molecular Methods for Blastocystis Subtyping

| Method | Target | Key Advantage | Key Limitation | Best Use Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STS-PCR [34] | Subtype-specific loci | Rapid, low-cost screening. | Lower sensitivity; may fail to detect some subtypes and mixed infections. | Initial, low-resolution population screening where specific known subtypes are targeted. |

| SSU-rDNA Sanger Sequencing (Barcode Region) [34] [36] | ~600 bp fragment of 18S rDNA | High sensitivity; provides sequence data for phylogenetic analysis; considered the gold standard. | Low throughput; struggles to resolve mixed infections. | Accurate subtyping of single-strain infections and for generating reference sequences. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS - Illumina) [35] [36] | Hypervariable regions (e.g., V3-V4) of 18S rDNA | High throughput; detects mixed infections and low-abundance subtypes. | Higher cost and bioinformatic burden; shorter reads. | Comprehensive biodiversity studies and epidemiology of complex infections. |

| Long-Read Sequencing (ONT) [36] | Full-length 18S rDNA gene (~1800 bp) | Maximum phylogenetic resolution; enables confident discovery of novel subtypes. | Higher error rate per read; requires computational correction. | Definitive subtype identification, phylogenetic studies, and discovery of new genetic lineages. |

Primer Design and Panel Selection for Single-Plex and Multi-Plex Assays

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Primer and Assay Design

What are the core design principles for PCR primers? Effective PCR primers should adhere to the following general properties [38] [39]:

- Length: 18-30 bases, with 18-24 being a common range.

- GC Content: 35-65%, with an ideal of 50%.

- Melting Temperature (Tm): 50-60°C, with primer pairs within 5°C of each other.

- 3' End: Should not be AT-rich; it is ideal to end with a G or C base pair.

- Specificity: Should be free of strong secondary structures (hairpins), self-dimers, or cross-dimers with the other primer.

How do I select a target DNA barcode region for parasite identification? The mitochondrial gene cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) is the standard DNA barcode for many animal taxa, including parasites and vectors [40] [41]. Studies have shown that a ~658 bp portion of this gene can successfully identify species, with high accuracy rates (e.g., 94-95% accord with other identification methods) observed in medically important parasites [40].

What is the recommended annealing temperature (Ta) for my primers? The annealing temperature should be set no more than 5°C below the Tm of your primers [38]. Using a Ta that is too low can lead to nonspecific amplification, while a Ta that is too high may reduce reaction efficiency.

Multiplex Assay Design and Execution

What are the key considerations when transitioning from a single-plex to a multi-plex assay? Multiplexing requires careful optimization to ensure all assays perform simultaneously without interference. Key considerations include [38] [42]:

- Primer/Probe Compatibility: Ensure all primer and probe pairs have similar Tm values to function under a single thermal cycling protocol and lack complementarity to prevent dimer formation.

- Panel Selection: Combine targets that require similar sample dilutions and are biologically relevant to your research question.

- Validation: The multiplex assay must be validated for performance parameters like specificity, selectivity, precision, and lot-to-lot reproducibility.

My multiplex assay shows high background or low signal. What could be wrong? This is a common issue with several potential causes and solutions [43] [44]:

- Incomplete Washing: Ensure all wash steps are performed thoroughly to remove unbound substances. Use the recommended wash buffer and confirm plate washer settings.

- Detection Antibody Incubation: Do not exceed the dictated incubation times for the detection antibody or Streptavidin-PE (SAPE), as this can increase background.

- Plate Reading: Resuspend beads properly in the correct reading buffer before acquisition. Using wash buffer for the final resuspension will lead to poor results.

- Bead Aggregation: Vortex the bead suspension well before use and ensure proper mixing during incubation steps.

Can I run a partial plate and use the rest later? Yes, but it requires careful handling [43]. Seal the unused half with plate sealing tape to prevent contamination. Use precise reagent volumes to ensure enough remains for the remaining wells. You must run a standard curve for each subsequent batch, and remade standards may be required.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: No or Low Amplification

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Primer Tm mismatch | Design primers so that both have a Tm within 60–64°C and within 2°C of each other [38]. |

| Low primer specificity | Run a BLAST alignment to ensure primers are unique to the target. Avoid primers with strong secondary structures (ΔG > -9.0 kcal/mol) [38]. |

| Annealing temperature is too high | Optimize the annealing temperature; start by setting it 5°C below the lowest primer Tm [38]. |

| Poor sample quality or quantity | Qualify your standard curve. For protein assays, sample optimization or dilution may be needed [44]. |

Problem: Nonspecific Amplification or High Background

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Annealing temperature is too low | Increase the annealing temperature in increments of 1-2°C [38]. |

| Primer-dimer formation | Screen primers for self-complementarity and heterodimers using tools like OligoAnalyzer. Redesign primers if necessary [38]. |

| Incomplete plate washing | Perform all washing steps thoroughly. When using a magnetic separator, ensure the plate is firmly attached and blot gently after decanting [43]. |

| Contamination from plate seal or splashing | Use a new plate seal for each incubation step. Use careful pipetting techniques to avoid cross-contamination between wells [44]. |

Problem: Low Bead Count in Multiplex Immunoassays

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Sample debris or viscosity | Thaw samples completely, vortex, and centrifuge at a minimum of 10,000 x g for 5-10 minutes to remove particulates [43]. |

| Bead clumping or sticking | Vortex beads for 30 seconds before adding to the plate. For "sticky" samples, you can resuspend beads in Wash Buffer (with detergent) before reading, but read the plate within 4 hours [43] [44]. |

| Improper instrument settings | Before acquisition, run calibration and verification beads. Review instrument settings, including correct bead gates and needle height [44]. |

| Inadequate resuspension | Shake the plate before acquisition to resuspend beads. Confirm the plate shaker is set to at least 500-800 rpm [43]. |

Experimental Protocols

Workflow: DNA Barcoding for Parasite Identification

This protocol outlines the steps for identifying field-collected parasites or vectors using the DNA barcoding method [41].

Detailed Methodologies:

Specimen Collection and DNA Extraction:

- Collect adult or larval specimens from the field. For larvae, stages L3-L4 are more reliably amplified than smaller L1-L2 stages [41].

- Preserve specimens in appropriate buffer or ethanol.

- Extract genomic DNA using a standard commercial kit.

PCR Amplification:

- Amplify a ~658 bp fragment of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) gene using universal or specific primers [41].

- PCR Reaction Setup: Prepare a master mix containing buffer, dNTPs, primers, polymerase, and template DNA.

- Thermal Cycling: A typical protocol includes: initial denaturation (94°C for 2-5 min); 35-40 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 30s), annealing (50-55°C for 30-45s), and extension (72°C for 45-60s); final extension (72°C for 5-10 min).

Sequencing and Data Analysis:

- Purify PCR products and perform Sanger sequencing.

- Edit sequences using software like Geneious to obtain high-quality consensus sequences [41].

- Compare the edited sequences (query) against a curated reference DNA barcode library (e.g., on BOLD database) or using the NCBI BLAST tool.

- Species identification is achieved based on the highest similarity match from the BLAST results. A hierarchical increase in mean genetic divergence is typically observed (within species: ~1.9%, within genus: ~17.8%) [41].

Workflow: One-Day Multiplex Immunoassay

This protocol summarizes the streamlined workflow for completing a MILLIPLEX multiplex assay in a single day [42].

Key Steps and Tips:

- Preparation: Warm all reagents to room temperature (20-25°C) before starting. Vortex and centrifuge all samples at 10,000 x g to remove debris [43].

- Incubation: Cover the plate with a sealer during shaking. Use an orbital shaker at 500-800 rpm for maximum mixing without splashing [43].

- Washing: All washing must be performed with the provided Wash Buffer. Incomplete washing is a major source of poor results [43] [44]. When using a magnetic separator, ensure the plate is firmly attached to the magnet.

- Reading: The plate must be read immediately (within 4 hours) if beads are resuspended in Wash Buffer. If stored in Sheath Fluid, the plate can be sealed, covered from light, stored at 2-8°C, and read within 72 hours [43].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions for Barcoding and Multiplexing

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| cox1 Primers | Universal primers targeting a ~658 bp region of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene are used for DNA barcoding and species identification of parasites and vectors [40] [41]. |

| MILLIPLEX/ProcartaPlex Multiplex Kits | Pre-optimized panels for multiplex immunoassays, providing high-quality, reproducible results and saving sample volume [43] [42]. |

| Universal Assay Buffer | A buffer that can be purchased separately to maintain assay consistency and for optimizing sample dilutions in immunoassays [44]. |

| Magnetic Bead Plates | Specialized plates (e.g., 96-well or 384-well) designed for use with magnetic beads in automated or manual wash steps [43]. |

| Handheld Magnetic Separation Block | A magnet used to separate magnetic beads from solution during wash steps in immunoassays [43]. |

| Orbital Plate Shaker | Critical for proper mixing during incubations. Should be calibrated to the highest speed without splashing (approx. 500-800 rpm) [43]. |

| Primer Design Tools (e.g., IDT SciTools) | Free online tools for designing and analyzing oligonucleotides, checking for dimers, hairpins, and calculating Tm [38]. |

| BLAST / BOLD Database | Online platforms (NCBI BLAST, Barcode of Life Data System) used to compare query sequences against reference libraries for species identification [38] [41]. |

Overcoming Technical Hurdles: From Host Contamination to Platform Errors

In DNA barcoding research of parasite taxa, the overwhelming presence of host DNA presents a significant challenge, often obscuring the target parasitic signal and reducing detection sensitivity. For researchers studying blood parasites, helminths, or other symbiotic organisms, selectively inhibiting host DNA amplification is a critical step for obtaining high-quality, reliable barcoding data. This technical guide explores two powerful molecular techniques—blocking primers and peptide nucleic acid (PNA) clamps—to effectively suppress host DNA background, enabling clearer parasite detection and identification.

FAQ: Understanding Host DNA Suppression

Q1: What are the primary molecular mechanisms behind blocking primers and PNA clamps?

Both technologies function by binding specifically to host DNA sequences and preventing their amplification during PCR:

Blocking Primers: These are traditional DNA oligos with a C3 spacer modification at their 3' end. This modification prevents DNA polymerase from extending the primer, thereby physically blocking amplification of the host template while allowing amplification of non-complementary parasite DNA [11]. They are designed to overlap with the binding site of universal PCR primers.

PNA Clamps: Peptide Nucleic Acids are synthetic molecules with a peptide-like backbone instead of the sugar-phosphate backbone of DNA. This structure confers higher binding affinity and specificity to complementary DNA sequences. PNA clamps bind tightly to host DNA and completely inhibit polymerase elongation during PCR, as the polymerase cannot displace or extend from the PNA-bound template [11] [45]. PNAs are not recognized as primers by DNA polymerases.

Q2: In what scenarios should I choose PNA clamps over blocking primers?

The choice depends on your required suppression efficiency and experimental budget:

- PNA Clamps are significantly more effective, achieving 99.3%–99.9% suppression of host DNA amplification. They are the preferred choice for applications requiring maximum sensitivity, such as detecting low-abundance parasites in heavily contaminated host samples (e.g., blood or tissue) [45].

- Blocking Primers offer a more cost-effective solution but with lower efficiency, typically suppressing 3.3%–32.9% of host DNA amplification [45]. They may be sufficient for samples with moderate host contamination or when target parasite DNA is relatively abundant.

Q3: How do I design an effective blocking primer or PNA clamp for my host-parasite system?

Effective design requires careful bioinformatic analysis:

- Identify a Target Region: Align the 18S rDNA (or other barcode gene) sequences of your host and target parasites. Identify a variable region within the universal primer amplicon that is highly conserved in the host but contains significant mismatches in the parasite sequences [11] [45].

- Design the Oligo: The blocker sequence should be complementary to this host-specific region and positioned to overlap with the 3' end of the universal primer binding site [45].

- For Blocking Primers: Add a C3 spacer (or other blocking group) to the 3' end during synthesis to prevent polymerase extension [11].

- For PNA Clamps: The entire molecule is synthesized as a PNA oligo. Their high affinity often allows for the use of shorter sequences (e.g., 15-18 bases) compared to traditional DNA blockers [46].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient host DNA suppression | Blocker concentration too low; annealing temperature suboptimal | Titrate blocker concentration (0.5–6 µM for PNA); optimize a clamping step (65°C–80°C for PNA); increase annealing temperature [46]. |

| Reduced or failed target amplification | Blocker concentration too high; non-specific binding to target | Titrate down blocker concentration; re-check blocker sequence specificity for host; verify target DNA quality/quantity [47]. |

| High background or smeared PCR products | PCR inhibitors in sample; non-specific amplification | Re-purify DNA template; increase annealing temperature; use hot-start polymerase; reduce PCR cycle number [48] [47]. |

| Inconsistent results between replicates | Pipetting errors; reagent degradation | Use master mixes for consistency; prepare fresh aliquots of blockers/PNAs; calibrate pipettes [48]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below summarizes key reagents for implementing host DNA suppression in parasite barcoding workflows.

| Item | Function & Application | Example Targets |

|---|---|---|

| C3-Modified Blocking Primer | Sequence-specific suppression of host 18S rDNA amplification; cost-effective for moderate suppression [11]. | Mammalian 18S rDNA [11]. |

| PNA Clamp | High-efficiency suppression of host DNA; ideal for samples with extreme host:parasite DNA ratios [11] [45]. | Mitochondrial rRNA, Chloroplast rRNA, Fish 18S rDNA [45] [46]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Accurate amplification of parasite target barcodes, minimizing sequencing errors in the barcode region. | All parasite DNA barcodes. |

| Universal 18S rDNA Primers | Amplification of a broad range of eukaryotic barcodes from parasites; foundation for targeted NGS [11]. | V4–V9 region of 18S rDNA [11]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Suppressing Mammalian Host DNA for Blood Parasite Detection

This protocol is adapted from a study that successfully detected Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense, Plasmodium falciparum, and Babesia bovis in human blood [11].

Primer and Blocker Design:

- Universal Primers: Use primers F566 and 1776R to amplify the ~1.2 kb V4–V9 region of the 18S rDNA gene.

- Blocking Primers: Design two blockers targeting human 18S rDNA:

3SpC3_Hs1829R: A C3 spacer-modified DNA oligo that competes with the universal reverse primer.HsPNA: A PNA oligo designed to bind internally and inhibit elongation.

PCR Setup:

- Reaction Mix: Combine template DNA (from blood), universal primers, both blocking primers, and a high-fidelity PCR master mix.

- PNA Clamping Step: Introduce a specific step in the PCR cycle after denaturation for PNA binding.