Harnessing AI-Powered Image Analysis: A New Paradigm in Parasitic Disease Diagnostics and Drug Discovery

This article explores the transformative role of Artificial Intelligence in parasitic disease control, addressing a critical need for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Harnessing AI-Powered Image Analysis: A New Paradigm in Parasitic Disease Diagnostics and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of Artificial Intelligence in parasitic disease control, addressing a critical need for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It provides a comprehensive analysis spanning from the foundational drivers for AI adoption—such as rising drug resistance and the limitations of traditional diagnostics—to the core methodologies of convolutional neural networks and AI-driven high-throughput screening in action. The content delves into practical strategies for overcoming common technical and data-related challenges, validates AI performance against human experts with comparative data, and synthesizes key takeaways to outline future directions for integrating AI into biomedical research and clinical practice.

The Urgent Need for AI in Parasitology: Addressing Drug Resistance and Diagnostic Gaps

The Growing Threat of Antimalarial and Antiparasitic Drug Resistance

Antimalarial drug resistance has emerged as a critical threat to global malaria control efforts. With an estimated 263 million malaria cases and approximately 597,000 deaths reported in 2023, the emergence and spread of drug-resistant parasites jeopardizes progress achieved over recent decades [1]. Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), the current mainstay for uncomplicated malaria treatment, are now compromised by partial resistance to artemisinin derivatives and partner drugs across multiple regions [2]. This application note examines the growing threat of antimalarial and antiparasitic resistance through the lens of artificial intelligence (AI) for parasite image analysis, providing researchers with current surveillance data, experimental protocols, and innovative computational approaches to address this pressing challenge.

Current Status of Antimalarial Drug Resistance

Global Resistance Patterns

The evolution of antimalarial drug resistance follows a historical pattern of successive drug failures. Chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine were previously compromised, and current ACTs now face similar challenges. Partial resistance to artemisinin derivatives, characterized by delayed parasite clearance, has been observed for over a decade in Southeast Asia and has now emerged in several African countries, including Rwanda, Uganda, Tanzania, and Ethiopia [2]. This is particularly concerning as the African region bears approximately 95% of the global malaria burden [3].

Table 1: Emerging Antimalarial Drug Resistance Patterns

| Resistance Type | Geographic Spread | Molecular Markers | Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Partial Artemisinin Resistance | Rwanda, Uganda, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Southeast Asia | kelch13 mutations (e.g., R561H) | Delayed parasite clearance (3-5 days instead of 1-2) |

| Partner Drug Resistance | Northern Uganda, Southeast Asia, isolated cases in Africa | Potential reduced susceptibility to lumefantrine | Requires higher drug doses for parasite clearance |

| Non-ART Combination Threat | Under investigation | Novel mechanisms | Potential first-line treatment failure |

Quantitative Resistance Surveillance Data

Recent clinical trials of next-generation antimalarials provide critical efficacy benchmarks against resistant strains. The Phase III KALUMA trial evaluated ganaplacide-lumefantrine (GanLum), a novel non-artemisinin combination therapy, demonstrating a PCR-corrected cure rate of 97.4% using an estimand framework (99.2% under conventional per protocol analysis) in patients with acute, uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria [3]. This promising efficacy against resistant parasites highlights the potential of new chemical entities with novel mechanisms of action.

Table 2: Efficacy of Novel Antimalarial Compounds Against Resistant Strains

| Compound/Combination | Development Phase | Mechanism of Action | Efficacy Against Resistant Parasites | Trial Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ganaplacide-lumefantrine (GanLum) | Phase III | Novel imidazolopiperazine (ganaplacide) disrupts parasite protein transport + lumefantrine | 97.4% PCR-corrected cure rate at Day 29 [3] | 1,668 patients across 12 African countries |

| Triple Artemisinin Combination Therapy (TACT) | Late-stage development | Combines artemether-lumefantrine with amodiaquine | High efficacy against resistant parasites in clinical studies [2] | Multicenter clinical trials |

AI-Driven Solutions for Resistance Monitoring

Convolutional Neural Networks for Parasite Detection and Speciation

Advanced AI models now enable highly accurate parasite detection and species identification directly from thick blood smears. A recent deep learning model utilizing a seven-channel input tensor achieved remarkable performance in classifying Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax, and uninfected white blood cells, with an accuracy of 99.51%, precision of 99.26%, recall of 99.26%, and specificity of 99.63% [1]. This represents a significant advancement over traditional binary classification systems that merely detect presence or absence of parasites without speciation capability.

Integrated Automated Diagnostic Systems

The iMAGING system represents a comprehensive approach to automated malaria diagnosis, integrating a robotized microscope, AI analysis, and smartphone application. This system performs autofocusing and slide tracking across the entire sample, enabling complete automation of the diagnostic process. When evaluated on a dataset of 2,571 labeled thick blood smear images, the YOLOv5x algorithm demonstrated a performance of 92.10% precision, 93.50% recall, 92.79% F-score, and 94.40% mAP0.5 for overall detection of leukocytes, early trophozoites, and mature trophozoites [4].

Experimental Protocols for Resistance Monitoring

AI-Assisted Microscopy for Parasite Detection and Speciation

Objective: To accurately detect Plasmodium parasites in thick blood smears and differentiate between species using convolutional neural networks.

Materials and Reagents:

- Giemsa-stained thick blood smear samples

- Optical microscope with 100x oil immersion objective

- Automated microscope system with X-Y stage control and autofocus capability

- High-resolution digital camera (minimum 5MP)

- Computing system with GPU acceleration (e.g., NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 or equivalent)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare thick blood smears according to standard WHO protocols [4].

- Stain with Giemsa (3% for 30-45 minutes) following established laboratory procedures.

- Air-dry slides completely before imaging.

Image Acquisition:

- Calibrate automated microscope for consistent illumination and focus.

- Program slide scanner to capture images from multiple fields of view (minimum 50 per sample).

- Save images in lossless format (TIFF preferred) at maximum resolution.

Data Preprocessing:

- Apply seven-channel input tensor transformation to enhance feature detection [1].

- Implement Canny algorithm edge detection on enhanced RGB channels.

- Normalize pixel values across the dataset to reduce batch effects.

Model Training:

- Partition dataset using 80:10:10 split for training, validation, and testing.

- Configure CNN architecture with residual connections and dropout layers.

- Set training parameters: batch size 256, 20 epochs, learning rate 0.0005, Adam optimizer.

- Utilize cross-entropy loss function for multiclass classification.

Validation:

- Perform 5-fold cross-validation to assess model robustness.

- Generate confusion matrices to evaluate species-specific accuracy.

- Calculate precision, recall, specificity, and F1 scores for performance metrics.

Molecular Surveillance of Antimalarial Resistance Markers

Objective: To detect and monitor genetic markers associated with antimalarial drug resistance.

Materials and Reagents:

- DNA extraction kit (commercial system recommended)

- PCR reagents: primers for kelch13, pfcrt, pfmdr1 genes

- Real-time PCR system

- Electrophoresis equipment or capillary sequencer

- Sanger sequencing reagents

Procedure:

- DNA Extraction:

- Extract parasite DNA from blood spots or cultured isolates using commercial kits.

- Quantify DNA concentration using spectrophotometry.

- Store extracts at -20°C until use.

PCR Amplification:

- Design primers targeting resistance-associated genes (kelch13 for artemisinin resistance).

- Perform PCR amplification with optimized thermal cycling conditions.

- Include positive and negative controls in each run.

Sequence Analysis:

- Purify PCR products using appropriate cleanup kits.

- Perform Sanger sequencing of amplified fragments.

- Analyze sequences for known resistance-conferring mutations.

- Submit novel mutations to public databases (e.g., NCBI).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Antimalarial Resistance Studies

| Reagent/Technology | Manufacturer/Provider | Function | Application in Resistance Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Giemsa Stain | Sigma-Aldrich, Merck | Staining malaria parasites in blood smears | Visual identification of parasitic stages for morphological analysis |

| YOLOv5x Algorithm | Ultralytics | Object detection neural network | Automated detection of parasites in digital blood smear images |

| kelch13 Genotyping Primers | Integrated DNA Technologies | Amplification of resistance-associated genes | Molecular surveillance of artemisinin resistance markers |

| iMAGING Smartphone Application | Custom development | Integrated diagnostic platform | Field-based automated parasite detection and quantification |

| 7-Channel Input Tensor | Custom implementation | Enhanced feature extraction for CNNs | Improved species differentiation in thick blood smears |

| Automated Microscope System | Custom 3D-printed design | Robotized slide scanning | High-throughput image acquisition for AI analysis |

| 1H-1,2,4-triazol-4-amine | 1H-1,2,4-triazol-4-amine | Heterocyclic Building Block | High-purity 1H-1,2,4-triazol-4-amine for research. A key scaffold in medicinal & agrochemical synthesis. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

| Isopromethazine | Isopromethazine, CAS:303-14-0, MF:C17H20N2S, MW:284.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Regulatory and Implementation Considerations

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recognized the increasing use of AI throughout the drug product life cycle, with the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) observing a significant increase in drug application submissions using AI components [5]. The FDA has published draft guidance titled "Considerations for the Use of Artificial Intelligence to Support Regulatory Decision Making for Drug and Biological Products" to provide recommendations on the use of AI in producing information intended to support regulatory decision-making regarding drug safety, effectiveness, and quality [5].

For successful implementation of AI-based parasite detection systems in resource-limited settings, several factors must be addressed: image resolution requirements for accurate diagnosis, optical attachment and adaptation to conventional microscopy, sufficient fields-of-view for representative sampling, and the need for focused images with Z-stacks [4]. Systems must function reliably without continuous internet connectivity and be powerable by portable solar batteries to ensure utility in remote endemic areas.

The growing threat of antimalarial and antiparasitic drug resistance demands innovative approaches that leverage artificial intelligence for enhanced surveillance and diagnosis. The integration of convolutional neural networks with automated imaging systems provides a powerful toolset for detecting resistant parasites and monitoring their spread. As resistance patterns continue to evolve, these AI-driven technologies will play an increasingly vital role in preserving the efficacy of existing treatments and guiding the deployment of next-generation antimalarial therapies.

Limitations of Traditional Microscopy and Manual Drug Discovery Processes

Traditional microscopy and manual processes have long been the foundation of parasitic disease research and drug discovery. However, these approaches present significant limitations in sensitivity, throughput, and objectivity that impede research efficiency and therapeutic development. This application note details these limitations through quantitative analysis, examines their impact on drug discovery pipelines, and presents emerging methodologies that address these constraints through automation, artificial intelligence, and advanced imaging technologies. The integration of these innovative approaches offers a pathway to more efficient, reproducible, and impactful research in parasitology and pharmaceutical development.

For decades, conventional microscopy has served as the primary tool for parasite identification and morphological analysis in both clinical diagnostics and basic research. Similarly, manual observation and assessment have formed the cornerstone of early drug discovery workflows. However, the persistence of parasitic diseases as major global health challenges—with soil-transmitted helminths alone affecting over 600 million people worldwide [6]—underscores the urgent need to overcome methodological limitations in research and development processes.

The high failure rate in clinical drug development, estimated at approximately 90% for candidates that reach clinical trials [7], further emphasizes the insufficiency of traditional approaches. A significant proportion of these failures (40-50%) stem from lack of clinical efficacy [7], often reflecting inadequate target validation or compound optimization during preclinical stages where traditional microscopy plays a central role. Within this context, understanding the specific constraints of established methodologies becomes essential for advancing both parasitic disease research and therapeutic development.

Quantitative Limitations of Traditional Approaches

The constraints of traditional microscopy and manual processes can be quantified across multiple dimensions, from diagnostic accuracy to operational efficiency. The following tables summarize key performance gaps between conventional and emerging approaches.

Table 1: Comparative Diagnostic Performance for Soil-Transmitted Helminths (n=704 samples) [6]

| Parasite Species | Manual Microscopy Sensitivity | Expert-Verified AI Sensitivity | Sensitivity Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hookworm | 78% | 92% | +14% |

| T. trichiura | 31% | 94% | +63% |

| A. lumbricoides | 50% | 100% | +50% |

Table 2: Impact of Methodological Limitations on Drug Discovery Outcomes [8] [7] [9]

| Limitation Category | Quantitative Impact | Consequence in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Low throughput | Limited to 10-100 samples per day per technician | Protracts screening of compound libraries |

| Subjectivity in analysis | High inter-observer variability (reported >30% in parasitology) | Inconsistent compound prioritization |

| Limited spatial resolution | ~200 nm resolution limit due to light diffraction [10] | Inability to visualize subcellular drug localization |

| Artifact susceptibility | 10-15% of data potentially compromised by preparation artifacts | Misleading efficacy or toxicity readouts |

Specific Limitations in Research and Development Contexts

Diagnostic and Research Sensitivity Constraints

Conventional microscopy exhibits particularly poor performance in detecting low-intensity infections, as evidenced by the dramatically low sensitivity for T. trichiura (31%) and A. lumbricoides (50%) shown in Table 1 [6]. This limitation has profound implications for both clinical management and research endpoints, as light infections may go undetected while still contributing to disease transmission and morbidity. The inability to reliably identify partial treatment effects or emerging resistance patterns during drug development represents a significant obstacle to developing effective antiparasitic therapies.

Throughput and Efficiency Limitations

Manual microscopy is inherently time-consuming and resource-intensive, requiring specialized expertise that may be unavailable in many settings [6]. In drug discovery contexts, traditional high-throughput screening (HTS) approaches often focus on single-target identification that fails to capture complex phenotypic responses [8]. This limitation is particularly problematic for traditional Chinese medicine research and other natural product studies where compounds may exert effects through multiple synergistic pathways [8]. The manual nature of conventional analysis creates substantial bottlenecks, with one study noting that experts must typically analyze more than 100 fields-of-view to identify parasite eggs in low-intensity infections [6].

Resolution and Subcellular Analysis Constraints

The diffraction limit of conventional optical microscopy (approximately 200 nm) [10] prevents detailed observation of drug localization and effects at subcellular levels. This is particularly problematic as more than one-third of drug targets are located within specific subcellular compartments [10]. Without the ability to visualize drug distribution within organelles such as mitochondria, lysosomes, or specific nuclear targets, researchers cannot fully understand pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic relationships at therapeutically relevant scales.

Figure 1: Resolution limitations in traditional microscopy compared to super-resolution techniques that enable subcellular drug tracking.

Data Management and Collaboration Challenges

Modern drug discovery generates massive, complex datasets that traditional approaches struggle to manage effectively. Research organizations often face challenges with siloed and disorganized data stored across multiple locations with inconsistent naming conventions and quality control processes [11]. The petabyte-scale datasets generated by advanced imaging technologies create substantial computational demands that conventional infrastructure cannot efficiently support [11]. Furthermore, collaboration barriers emerge when teams attempt to share sensitive biomedical data while maintaining regulatory compliance across distributed research networks [11].

Emerging Solutions and Methodologies

High-Content Screening Technologies

High-content screening (HCS) represents a paradigm shift from traditional microscopy by combining automated fluorescence microscopy with computational image analysis to simultaneously track multiple cellular parameters [8] [9]. This approach enables multiparametric analysis of cellular morphology, subcellular localization, and physiological changes across thousands of individual cells in a single experiment [8]. By implementing HCS, researchers can move beyond single-target assessment to evaluate complex phenotypic responses to potential therapeutics, thereby generating more physiologically relevant data early in the drug discovery pipeline.

Figure 2: High-content screening workflow enabling multiparametric cellular analysis for drug discovery.

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Integration

AI-supported microscopy represents a transformative approach to overcoming the limitations of manual image analysis. Deep learning algorithms, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), can be trained on large datasets of parasite images to achieve remarkable accuracy in identification and classification [12] [6]. The expert-verified AI approach, which combines algorithmic pre-screening with human confirmation, has demonstrated superior sensitivity for all major soil-transmitted helminth species while reducing expert analysis time to less than one minute per sample [6]. In drug discovery contexts, AI models have been successfully deployed for predictive toxicology assessments, such as deep learning detection of cardiotoxicity in human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes [9].

Advanced Imaging Modalities

Super-resolution microscopy (SRM) techniques break the diffraction limit of conventional light microscopy, enabling researchers to visualize drug dynamics at nanoscale resolutions (20-50 nm) [10]. Key SRM methodologies include:

- STED (Stimulated Emission Depletion) microscopy: Uses two laser beams to achieve nanoscale resolution through point scanning [10]

- STORM/PALM (Single-Molecule Localization Microscopy): Achieves super-resolution by sequentially activating and localizing individual fluorophores [10]

- SIM (Structured Illumination Microscopy): Enhances resolution through structured light patterns and computational reconstruction [10]

These technologies enable subcellular pharmacokinetic studies by tracking drug localization and distribution within specific organelles, providing critical insights into therapeutic mechanisms and potential toxicity [10].

Integrated Data Management Platforms

Modern research informatics platforms address data management challenges through automated curation workflows, centralized data repositories, and scalable computational infrastructure [11]. These systems support comprehensive provenance tracking that maintains audit trails for regulatory compliance while enabling efficient collaboration across distributed research teams [11]. By implementing structured data management architectures, organizations can transform disorganized imaging data into query-ready assets suitable for machine learning and advanced analytics [11].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Expert-Verified AI Microscopy for Parasite Detection

This protocol details the methodology for AI-supported digital microscopy of intestinal parasitic infections, adapted from von Bahr et al. [6].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential reagents and materials for AI-supported parasite detection

| Item | Specification | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Portable whole-slide scanner | Must be compatible with brightfield imaging | Sample digitization for analysis |

| Kato-Katz staining reagents | Standard parasitology staining solution | Visual enhancement of parasite eggs |

| AI classification software | CNN-based algorithm trained on parasite image datasets | Automated detection and preliminary classification |

| Expert verification interface | Web-based or standalone application | Human confirmation of AI findings |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sample Preparation

- Prepare fecal smears using standard Kato-Katz technique

- Allow slides to clear for 30-60 minutes at room temperature

- Ensure smear thickness permits visualization but maintains clarity

Slide Digitization

- Load prepared slides into portable whole-slide scanner

- Digitize entire smear at 40x magnification

- Export images in standardized format (TIFF recommended)

AI Analysis

- Process digitized images through pre-trained CNN algorithm

- Generate preliminary classifications of potential parasite eggs

- Flag regions of interest for expert verification

Expert Verification

- Review AI-identified objects through verification interface

- Confirm or correct classifications based on morphological expertise

- Finalize diagnosis based on verified findings

Data Management

- Archive original images and analysis results

- Document any discrepancies between AI and expert assessments

- Update AI training sets based on verified corrections

Technical Notes

- Total processing time: approximately 15 minutes per sample

- Expert hands-on time: less than 1 minute per sample

- Optimal for processing batches of 20-40 samples per session

- Sensitivity improvements most pronounced for low-intensity infections

Protocol: High-Content Screening for Compound Efficacy Assessment

This protocol outlines the application of high-content screening for evaluating anti-parasitic compounds, adapted from HCS methodologies in drug discovery [8] [9].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential reagents for high-content screening in parasitology

| Item | Specification | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cell painting dyes | 6-fluorophore combination (e.g., Mitotracker, Phalloidin, DAPI) | Multiplexed staining of cellular structures |

| Automated imaging system | Confocal or widefield HCS microscope with environmental control | High-throughput image acquisition |

| Image analysis software | CellProfiler or commercial equivalent | Automated feature extraction and analysis |

| 3D culture matrix | Matrigel or synthetic alternative | Support for physiologically relevant models |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Model System Preparation

- Culture parasite-infected cell lines or 3D host-parasite models

- Seed cells into 96-well or 384-well HCS-optimized plates

- Allow models to establish for 24-48 hours before treatment

Compound Treatment

- Prepare compound libraries in DMSO with concentration gradients

- Treat models with test compounds for predetermined exposure periods

- Include appropriate controls (vehicle, positive, negative)

Multiplexed Staining

- Fix samples with paraformaldehyde (4% for 15 minutes)

- Permeabilize with Triton X-100 (0.1% for 10 minutes)

- Apply cell painting dye cocktail according to established protocols

- Incubate for specified durations with appropriate washing

Automated Imaging

- Program HCS system for multi-site acquisition

- Capture 9-16 fields per well at 20x or 40x magnification

- Include multiple fluorescence channels corresponding to dyes

- For 3D models, implement z-stack acquisition (15-30 slices)

Image Analysis and Feature Extraction

- Run CellProfiler pipeline for cell segmentation and feature extraction

- Quantify morphological parameters (size, shape, intensity, texture)

- Apply machine learning algorithms for phenotypic classification

- Generate compound efficacy scores based on multiparametric assessment

Technical Notes

- Optimal staining concentrations require empirical determination for each parasite system

- 3D models provide greater physiological relevance but increase computational demands

- Multiparametric analysis enables detection of subtle phenotypes missed by single-endpoint assays

- Recommended to include mechanism-of-action reference compounds for comparison

Traditional microscopy and manual drug discovery processes present significant limitations in sensitivity, throughput, resolution, and data management that impede progress in parasitic disease research and therapeutic development. Quantitative assessments demonstrate substantial gaps in diagnostic performance, particularly for low-intensity infections, while the high failure rate of clinical drug candidates underscores the insufficiency of conventional approaches for predicting therapeutic efficacy.

The integration of advanced technologies—including high-content screening, artificial intelligence, super-resolution microscopy, and structured data management platforms—offers a transformative pathway forward. These methodologies enable multiparametric analysis at unprecedented scales and resolutions, providing more physiologically relevant data earlier in the research pipeline. By adopting these innovative approaches, researchers can overcome the constraints of traditional methods, potentially accelerating the development of more effective treatments for parasitic diseases that continue to affect vulnerable populations globally.

Application Note: AI-Powered Diagnostic Platforms for Parasitology

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into clinical parasitology is transforming diagnostic workflows by enhancing the speed, accuracy, and accessibility of parasite detection. This application note details how AI, particularly deep learning models, is being deployed to analyze medical images for parasitic infections, directly supporting research and drug development efforts.

AI for High-Throughput Stool Sample Analysis

Background & Drivers: Traditional diagnosis of intestinal parasites via microscopic examination of stool samples is a time-consuming process requiring highly trained specialists. This creates a market driver for solutions that increase laboratory efficiency and diagnostic throughput without compromising accuracy [13].

Quantitative Performance of an AI Diagnostic Tool:

| Metric | Performance Result | Comparative Note |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Agreement | 98.6% [13] | After discrepancy analysis between AI and manual review. |

| Additional Organisms Detected | 169 [13] | Organisms previously missed in manual reviews. |

| Clinical Sensitivity | Improved [13] | Better likelihood of detecting pathogenic parasites. |

| Dataset Size (Training/Validation) | >4,000 samples [13] | Included 27 parasite classes from global sources. |

Key Technology: A deep-learning model based on a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) was developed to detect protozoan and helminth parasites in concentrated wet mounts of stool. This system automates the identification of telltale cysts, eggs, or larvae [13].

Smartphone Microscopy for Field-Based Parasite Detection

Background & Drivers: In resource-constrained settings endemic for neglected tropical diseases like Chagas disease, the scarcity of skilled microscopists and advanced laboratory equipment creates a critical need for portable, easy-to-use, and low-cost diagnostic tools [14].

Performance of a Smartphone-Integrated AI System for T. cruzi Detection:

| Metric | Performance Result | Model & Dataset Details |

|---|---|---|

| Precision | 86% [14] | SSD-MobileNetV2 on human sample images. |

| Recall (Sensitivity) | 87% [14] | SSD-MobileNetV2 on human sample images. |

| F1-Score | 86.5% [14] | SSD-MobileNetV2 on human sample images. |

| Human Dataset | 478 images from 20 samples [14] | Included thick/thin blood smears and cerebrospinal fluid. |

Key Technology: The system employs lightweight AI models like SSD-MobileNetV2 and YOLOv8, which are optimized for real-time analysis on a smartphone. The phone is attached to a standard light microscope using a 3D-printed adapter, creating a portable digital imaging system [14].

AI-Assisted Image Segmentation for Research Workflows

Background & Drivers: In clinical and research settings, annotating regions of interest in medical images (segmentation) is a foundational but immensely time-consuming first step. This creates a driver for tools that accelerate this process without requiring machine-learning expertise from the user [15].

Key Technology: Systems like MultiverSeg use an interactive AI model that allows a researcher to segment new biomedical imaging datasets by providing a few initial clicks or scribbles on images. The model uses these interactions and a context set of previously segmented images to predict the segmentation for new images, dramatically reducing the manual effort required [15].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a CNN for Stool Parasite Detection

This protocol outlines the methodology for developing and validating a deep-learning model for automated parasite detection in stool wet mounts, based on the approach pioneered by ARUP Laboratories [13].

Sample Collection & Preparation:

- Gather a large and diverse set of parasite-positive stool samples. The dataset should encompass a wide range of parasite species (e.g., the study used 27 classes) and be sourced from different geographical regions to ensure robustness [13].

- Prepare concentrated wet mounts from the samples according to standard laboratory procedures.

Image Acquisition & Dataset Curation:

- Digitize the wet mounts using a microscope with a digital camera to create a high-resolution image dataset.

- Expert parasitologists manually review and annotate each image, marking the location and species of each parasite. This curated dataset serves as the "ground truth" for training.

Model Training & Validation:

- Architecture Selection: Employ a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architecture, which is particularly effective for image recognition tasks [13].

- Training: Train the CNN on the annotated image dataset. The model learns to associate specific visual features with the presence of different parasites.

- Validation: Validate the trained model's performance on a separate, held-out set of images not seen during training. Key metrics include clinical sensitivity, specificity, and positive agreement with expert manual review.

Protocol 2: Real-TimeTrypanosoma cruziDetection with Smartphone Microscopy

This protocol details the procedure for using a smartphone-based AI system to detect T. cruzi trypomastigotes in blood smears, suitable for field use in endemic areas [14].

Equipment Setup:

- Attach a smartphone to the ocular of a standard light microscope using a 3D-printed adapter.

- Ensure the smartphone camera is properly aligned to capture a clear and well-illuminated image of the sample.

Sample Preparation & Staining:

- Prepare thin or thick blood smears from a fresh blood sample on a glass slide.

- Stain the smear (e.g., with Giemsa) to enhance the contrast and visibility of parasites.

Image Acquisition & AI Analysis:

- Place the prepared slide on the microscope stage.

- Using a custom application on the smartphone, capture images of the smear.

- The onboard AI model (e.g., SSD-MobileNetV2 or YOLOv8) processes the image in real-time, identifying and flagging potential T. cruzi trypomastigotes.

Result Interpretation:

- The application displays the analysis results, indicating the detected parasites. A researcher can use this for rapid screening and quantification of parasitemia.

Protocol 3: Rapid Dataset Segmentation with MultiverSeg

This protocol describes how to use an interactive AI tool to quickly segment a new set of biomedical images for research purposes, such as quantifying parasites in histological sections [15].

Initialization:

- Load the MultiverSeg tool and upload the first image from your dataset.

Interactive Segmentation:

- Provide initial user interactions on the image, such as clicks, scribbles, or boxes, to mark the areas of interest (e.g., a parasite).

- The model uses these inputs to predict a segmentation mask for the entire image.

Iterative Refinement & Context Building:

- If the prediction is imperfect, provide additional interactions to correct it. The model updates its prediction in real-time.

- Once satisfied, save the segmented image. This image is automatically added to the model's "context set."

Automated Segmentation of Subsequent Images:

- Upload the next image in the dataset. The model will now use the growing context set of previously segmented images to make a more accurate prediction, requiring fewer user interactions.

- After segmenting several images, the model may achieve high accuracy with minimal or zero input, allowing for rapid batch processing of the entire dataset.

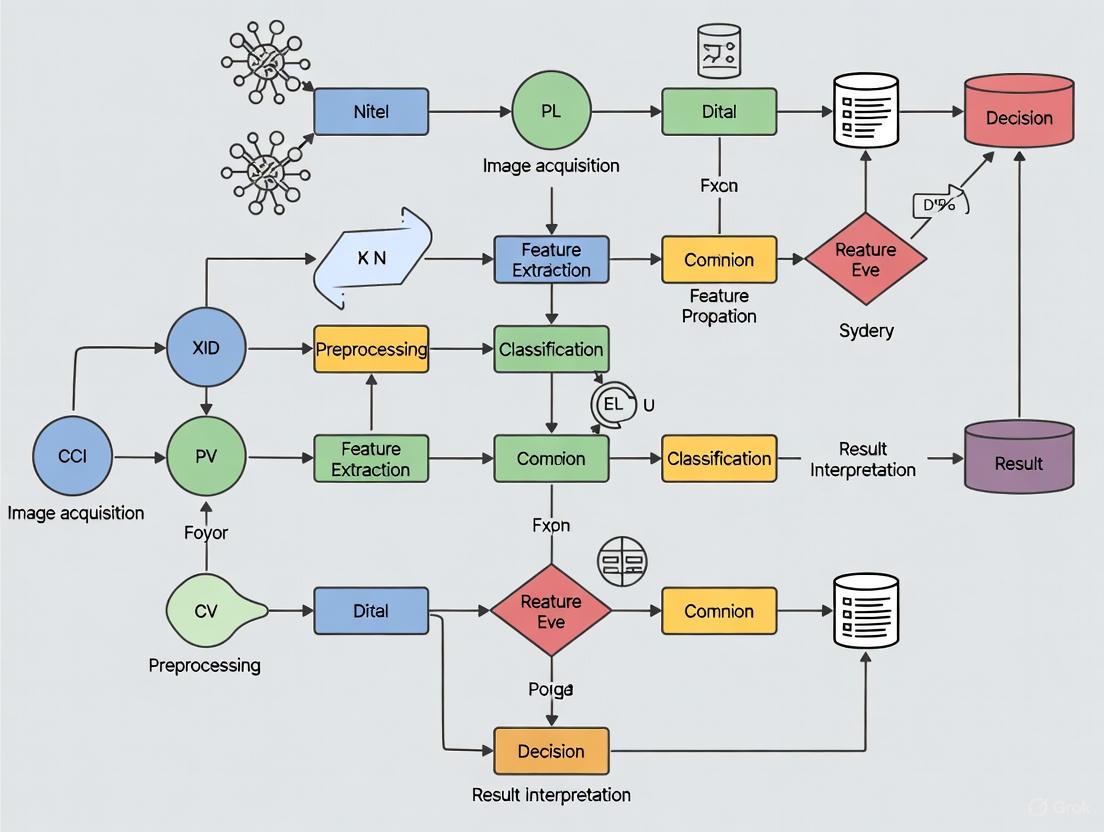

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Solution | Function in AI-Based Parasite Research |

|---|---|

| Stool Preservation Kits | Maintains parasite integrity for accurate image acquisition and AI model training [13]. |

| Giemsa & Other Stains | Enhances visual contrast in blood smears and other samples, improving AI detection accuracy [14]. |

| 3D-Printed Microscope Adapters | Enables standardized smartphone attachment for consistent field imaging [14]. |

| Annotated Image Datasets | Serves as the "ground truth" for training and validating AI models; a critical research reagent [13] [14]. |

| Pre-trained AI Models (e.g., YOLOv8, U-Net) | Accelerates development by providing a starting point for custom model training (transfer learning) [14]. |

| Cloud AI Platforms (e.g., Google AI Platform) | Provides computational resources and tools for building, training, and deploying custom medical imaging AI models [16]. |

| Periandrin V | Periandrin V, CAS:152464-84-1, MF:C41H62O14, MW:778.9 g/mol |

| Olean-12-en-3-one | Olean-12-en-3-one|CAS 638-97-1|β-Amyrone |

The application of artificial intelligence (AI) in parasite image analysis represents a transformative advancement for parasitology research and tropical disease management. AI technologies, particularly deep learning and computer vision, are addressing critical diagnostic challenges across diverse parasitic diseases, including malaria, intestinal parasites, and neglected tropical diseases (NTDs). These tools demonstrate remarkable capability in analyzing microscopic images, rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs), and mosquito surveillance photographs with accuracy comparable to human experts [17] [18]. The integration of AI into parasitology research pipelines is accelerating diagnostics, enhancing surveillance capabilities, and creating new opportunities for drug discovery, particularly crucial given the stalled progress in global malaria control and the persistent burden of NTDs [17] [19].

This protocol collection provides detailed methodological frameworks for implementing AI-driven image analysis across key parasitology applications. By standardizing these approaches, we aim to enhance reproducibility, facilitate technology transfer between research groups, and ultimately contribute to improved disease management through more accessible, efficient, and accurate diagnostic solutions.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: AI-Assisted Malaria Detection from Blood Smear Images

Principle: This protocol describes a standardized methodology for developing and validating deep learning models to detect Plasmodium parasites in thin blood smear images, achieving diagnostic accuracy exceeding 96% [18].

Materials:

- Giemsa-stained thin blood smear slides

- Microscope with digital camera or whole slide scanner

- Computing workstation with GPU acceleration (minimum 8GB VRAM)

- Python 3.8+ with TensorFlow/PyTorch frameworks

- Publicly available dataset of 27,558 blood smear images [18]

Procedure:

- Image Acquisition: Capture high-resolution (≥1024×1024 pixels) digital images of blood smear fields at 100× magnification under standardized lighting conditions.

- Data Preprocessing:

- Apply color normalization to minimize staining variation

- Partition dataset into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets

- Implement data augmentation (rotation, flipping, brightness adjustment) to increase dataset diversity

- Model Development:

- Implement transfer learning using pretrained architectures (ResNet-50, VGG16, DenseNet-201)

- Extract deep features from multiple architectures

- Apply principal component analysis for dimensionality reduction

- Implement hybrid classifier combining support vector machine and long short-term memory networks

- Model Validation:

- Evaluate performance using 5-fold cross-validation

- Assess accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, and F1-score

- Compare model predictions against expert microscopist readings

- Explainability Analysis:

- Implement Grad-CAM and LIME techniques to visualize discriminatory regions

- Generate heatmaps highlighting features contributing to classification decisions

Technical Notes: For optimal performance, ensure class balance between infected and uninfected cells. The stacked LSTM with attention mechanism has demonstrated superior performance (99.12% accuracy) [20]. Model interpretability is enhanced through explainable AI techniques, crucial for clinical adoption.

Protocol: AI-Powered Rapid Diagnostic Test Interpretation

Principle: This protocol outlines the deployment of an AI-powered Connected Diagnostics (ConnDx) system for standardized interpretation of malaria RDTs, enabling real-time surveillance in resource-limited settings [17].

Materials:

- Standard malaria RDTs (Paracheck Pf, BIOLINE Malaria Ag Pf, CareStart Malaria)

- Smartphone with HealthPulse application

- Cloud computing infrastructure

- Database system for result aggregation

Procedure:

- RDT Imaging:

- Capture RDT image using smartphone camera 15-20 minutes after test administration

- Ensure adequate lighting and minimal glare

- Position test cassette centrally in frame with all components visible

- AI Interpretation Pipeline:

- Object Detection: Locate RDT and identify brand/type

- Line Detection: Identify test and control lines within result window

- Classification: Determine probability of line presence in each region

- Quality Assurance: Flag adverse conditions (improper lighting, invalid tests)

- Result Validation:

- Compare AI interpretation against expert panel consensus

- Calculate weighted F1 score and Cohen's Kappa for agreement

- Monitor performance across different facilities and users

- Data Integration:

- Upload results to cloud-based dashboard

- Aggregate data for real-time epidemiological surveillance

- Generate automated alerts for positive cases

Technical Notes: The AI model demonstrated 96.4% concordance with expert panel interpretation, with sensitivity of 96.1% and specificity of 98.0% [17]. Regular retraining with field-collected images improves robustness to real-world variations.

Protocol: Mosquito Surveillance Using Citizen Science and AI

Principle: This protocol combines citizen science and AI image recognition to enhance vector surveillance, enabling early detection of invasive malaria mosquito species through community-generated photographs [21].

Materials:

- NASA GLOBE Observer mobile application or equivalent

- AI algorithms trained on authenticated mosquito images

- Database for geotagged mosquito observations

- Reference collection of mosquito species for algorithm training

Procedure:

- Citizen Data Collection:

- Train community members in mosquito larva and adult photography

- Capture images of mosquitoes in breeding sites (e.g., water containers, tires)

- Record GPS coordinates and timestamp for all observations

- Image Analysis:

- Upload images to cloud-based analysis platform

- Implement convolutional neural networks for species identification

- Apply larval identification algorithms with >99% confidence threshold

- Compare against reference database of Anopheles stephensi and related species

- Validation and Response:

- Verify AI identifications through expert entomologist review

- Map detected invasive species for targeted vector control

- Correlate detections with malaria case reports

- Technology Transfer:

- Develop AI-enabled smart traps for autonomous surveillance

- Implement early warning systems for invasive species detection

Technical Notes: This approach successfully identified the first specimen of invasive Anopheles stephensi in Madagascar through a single citizen-submitted photograph, enabling rapid public health response [21].

Performance Metrics and Comparative Analysis

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AI Models for Malaria Detection

| Model Architecture | Accuracy (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | F1-Score | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-model ensemble with majority voting [18] | 96.47 | 96.03 | 96.90 | 0.9645 | Blood smear analysis |

| Stacked LSTM with attention mechanism [20] | 99.12 | 99.10 | 99.13 | 0.9911 | Blood smear analysis |

| AI-powered RDT interpretation [17] | 96.40 | 96.10 | 98.00 | 0.9750 | Rapid diagnostic tests |

| CNN-based larval identification [21] | >99.00 | N/R | N/R | N/R | Mosquito surveillance |

Table 2: AI Model Performance Across Different Parasite Detection Applications

| Performance Metric | Blood Smear Analysis | RDT Interpretation | Mosquito Surveillance | Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Throughput | High (batch processing) | Very high (real-time) | Moderate (image acquisition) | High (automated screening) |

| Equipment Cost | High (microscope + scanner) | Low (smartphone) | Variable (field deployment) | Very high (HTS systems) |

| Technical Expertise Required | High (both parasitology and AI) | Low (minimal training) | Moderate (field collection + AI) | Very high (specialized) |

| Explanability | Moderate (XAI techniques available) | High (direct line detection) | Moderate (species features) | Variable (model-dependent) |

| Regulatory Status | Research use primarily | CE-marked/ FDA-cleared emerging | Research phase | Early development |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for AI-Based Parasite Image Analysis

| Category | Specific Reagents/Tools | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Samples | Giemsa-stained blood smears | Model training and validation | Ensure species representation (P. falciparum, P. vivax) |

| Field-collected RDTs | Real-world algorithm testing | Include major brands (Paracheck, BIOLINE, CareStart) | |

| Mosquito specimen images | Vector surveillance algorithms | Cover different life stages (larvae, adults) | |

| Annotation Resources | Expert microscopist panels | Ground truth establishment | Inter-reader variability assessment crucial |

| Standardized annotation protocols | Consistent labeling across datasets | Follow community guidelines where available | |

| Computational Frameworks | TensorFlow/PyTorch | Deep learning model development | GPU acceleration essential for training |

| OpenCV | Image preprocessing and augmentation | Standardize across research sites | |

| Scikit-learn | Traditional machine learning components | Feature selection and dimensionality reduction | |

| Model Architectures | CNN architectures (ResNet, VGG) | Feature extraction from images | Transfer learning from ImageNet effective |

| Vision Transformers | Alternative approach for image analysis | Emerging application in medical imaging | |

| Ensemble methods | Performance enhancement | Combine multiple models for robustness | |

| Validation Tools | Cross-validation frameworks | Performance assessment | 5-fold or 10-fold recommended |

| Explainable AI libraries (Grad-CAM, LIME) | Model interpretability | Critical for clinical translation | |

| Statistical analysis packages | Significance testing | Assess differences between models | |

| Calcium pimelate | Calcium Pimelate|C7H10CaO4|Nucleating Agent | Calcium pimelate is a highly effective β-nucleating agent for polypropylene research, enhancing polymer toughness and thermal stability. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

| 2,5-Diphenylfuran | 2,5-Diphenylfuran, CAS:955-83-9, MF:C16H12O, MW:220.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Workflow Visualization

AI-Parasite Research Workflow

Malaria Detection Pipeline

These application notes and protocols demonstrate the significant potential of AI-based image analysis across diverse parasitology applications. The standardized methodologies presented here enable researchers to implement robust AI systems for parasite detection, species identification, and surveillance. As these technologies mature, key future directions include developing more explainable AI systems suitable for clinical adoption, creating multi-task models capable of detecting multiple parasite species from single images, and establishing standardized benchmarking datasets to facilitate cross-study comparisons. The integration of AI into parasitology research represents a paradigm shift with potential to significantly impact global efforts to control and eliminate parasitic diseases, particularly in resource-limited settings where diagnostic expertise may be limited. By providing these detailed protocols and performance benchmarks, we aim to accelerate the adoption and rigorous implementation of AI technologies throughout parasitology research and practice.

AI in Action: Core Technologies and Real-World Applications for Researchers

Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for Parasite Detection and Classification

Parasitic infections remain a significant global health challenge, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions, where they contribute to malnutrition, anemia, and increased susceptibility to other diseases [22]. Accurate and timely diagnosis is crucial for effective treatment and disease control. Traditional diagnostic methods, primarily microscopic examination of blood smears, though considered the gold standard, are labor-intensive, time-consuming, and rely heavily on the expertise of trained personnel, leading to potential human error and subjectivity [1] [22] [23].

The field of parasitic diagnosis is undergoing a transformation with the integration of artificial intelligence (AI). Deep learning, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), is revolutionizing parasite detection by automating the analysis of medical images with high accuracy [22]. These technologies offer promising solutions to overcome the limitations of traditional microscopy, providing tools capable of interpreting complex image data consistently and efficiently [1]. This document details the application, performance, and experimental protocols of deep CNN models within the broader context of AI-driven parasite image analysis, providing a resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

Performance of CNN Models in Parasite Detection

Recent research demonstrates that CNN-based models achieve exceptional performance in detecting and classifying parasites from microscopic images. The following table summarizes the quantitative results from several state-of-the-art studies, primarily focused on malaria detection, which serves as a key application area.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Recent Deep Learning Models for Parasite Detection

| Model Name | Reported Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN with 7-channel input [1] | 99.51% | 99.26% | 99.26% | 99.26% | Multi-channel input for enhanced feature extraction from thick smears |

| CNN-ViT Ensemble [24] | 99.64% | 99.23% | 99.75% | 99.51% | Hybrid model combining local (CNN) and global (ViT) feature learning |

| DANet [25] | 97.95% | - | - | 97.86% | Lightweight dilated attention network (~2.3M parameters) |

| Optimized CNN + Otsu [23] | 97.96% | - | - | - | Otsu thresholding for segmentation as a preprocessing step |

| BLGSNet [26] | 99.25% | - | - | - | Novel CNN with Batch Normalization, Layer Normalization, GELU & Swish |

These models represent a significant advancement beyond simple binary classification (infected vs. uninfected). For instance, the CNN model with a seven-channel input was specifically designed for multiclass classification, successfully distinguishing between Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax, and uninfected white blood cells with species-specific accuracies of 99.3% and 98.29%, respectively [1]. Furthermore, a key research direction is the development of computationally efficient models like DANet, which achieves high accuracy with only 2.3 million parameters, making it suitable for deployment on edge devices like a Raspberry Pi 4 in resource-constrained settings [25].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section outlines the methodologies for two key experiments cited in this document, providing a reproducible framework for researchers.

Objective: To train a Convolutional Neural Network for the classification of cells into P. falciparum-infected, P. vivax-infected, and uninfected categories from thick blood smear images.

Workflow:

Methodology:

- Dataset: Use a dataset of 5,941 thick blood smear images, processed to obtain 190,399 individually labeled cell images [1].

- Data Splitting: Split the data into training (80%), validation (10%), and test (10%) sets.

- Image Preprocessing: Apply advanced preprocessing to create a seven-channel input tensor. This includes techniques like enhancing hidden features and applying the Canny Algorithm to enhanced RGB channels to extract richer features [1].

- Model Architecture: Implement a CNN with up to 10 principal layers. Incorporate fine-tuning techniques such as residual connections and dropout to improve stability and accuracy.

- Training Configuration:

- Batch Size: 256

- Epochs: 20

- Optimizer: Adam, with a learning rate of 0.0005

- Loss Function: Cross-entropy

- Evaluation: Assess the model on the test set using metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, specificity, and F1-score. Generate a confusion matrix to visualize performance per class.

- Validation: Perform a 5-fold cross-validation using the StratifiedKFold method from scikit-learn to ensure model robustness and generalizability [1].

Objective: To improve CNN classification accuracy by employing Otsu's thresholding as a preprocessing step to segment and highlight parasite-relevant regions in blood smear images.

Workflow:

Methodology:

- Dataset: Utilize a dataset of blood smear images (e.g., 43,400 images) and split it for training and testing (e.g., 70:30) [23].

- Preprocessing - Segmentation: Apply Otsu's thresholding method to each RGB image. This global thresholding technique automatically calculates an optimal threshold value to separate the image into foreground (potential parasite regions) and background, reducing noise and enhancing relevant morphological features [23].

- Model Training: Train a baseline CNN model (e.g., a 12-layer CNN) on both the original and the Otsu-segmented datasets.

- Performance Comparison: Compare the classification accuracy of the model trained on segmented images versus the one trained on raw images. The study reported an accuracy improvement from 95% to 97.96% using this method [23].

- Segmentation Validation: In the absence of pixel-wise ground truth annotations, validate the effectiveness of the Otsu segmentation through:

- Visual Inspection: Manually check if the segmented regions correspond to parasitic structures.

- Canny Edge Detection: Apply edge detection to highlight the contours of the segmented regions for qualitative assessment [23].

- Quantitative Metrics (if ground truth is available): Compute the Dice coefficient and Jaccard Index (IoU) by comparing Otsu-generated masks with manually annotated reference masks. The original study achieved a mean Dice coefficient of 0.848 [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues essential materials, datasets, and software tools used in the development of deep CNN models for parasite detection.

Table 2: Essential Research Materials and Tools for CNN-based Parasite Detection

| Item Name | Type | Function in Research | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thick Blood Smear Images | Dataset | Confirms presence of parasites; source for cell-level image patches. | Chittagong Medical College Hospital dataset [1] |

| NIH Malaria Dataset | Benchmark Dataset | Public dataset for training and benchmarking models on infected vs. uninfected red blood cells. | 27,558 cell images [25] |

| Multi-class Parasite Dataset | Dataset | Enables development of models for classifying multiple parasite species. | Dataset with 8 categories (e.g., Plasmodium, Leishmania, Toxoplasma) [26] |

| Otsu's Thresholding Algorithm | Image Processing Algorithm | Preprocessing step to segment and isolate parasite regions, boosting CNN performance. | OpenCV, Scikit-image [23] |

| Adam Optimizer | Software Tool | Adaptive optimization algorithm for updating network weights during training. | Learning rate=0.0005 [1] |

| Cross-Entropy Loss | Software Tool | Loss function used for training classification models, in line with Maximum Likelihood Estimation. | Standard for classification tasks [1] [27] |

| SmartLid Blood DNA/RNA Kit | Wet-lab Reagent | Magnetic bead-based nucleic acid extraction for molecular validation (e.g., LAMP, qPCR). | Used in sample prep for LAMP-based detection [28] |

| Colorimetric LAMP Assay | Wet-lab Reagent | Isothermal amplification for highly sensitive, field-deployable molecular confirmation of parasites. | Pan/Pf detection in capillary blood [28] |

| 2-Keto palmitic acid | 2-Keto Palmitic Acid|High-Purity Research Chemical | 2-Keto palmitic acid is a key metabolite for research into fatty acid synthesis and oxidation. This product is for research use only and not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

| Apocynoside II | Apocynoside II||Research Use Only | Apocynoside II is a natural product compound for research use only. It is strictly for laboratory applications and not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

This case study explores the transformative impact of artificial intelligence (AI) in the field of parasitology, focusing on the automated analysis of stool wet mounts and blood smears. Traditional microscopic examination of these specimens remains the gold standard for diagnosing parasitic infections but is hampered by its manual, labor-intensive nature, subjectivity, and reliance on highly skilled personnel [29] [30]. In high-income countries, the low prevalence of parasites in submitted specimens leads to technologist fatigue and potential diagnostic errors, while resource-limited settings often lack the necessary expertise altogether [30]. AI technologies, particularly deep learning and convolutional neural networks (CNNs), are overcoming these barriers by providing rapid, accurate, and scalable diagnostic solutions. This document details the quantitative performance, experimental protocols, and key reagents driving this technological shift, providing a resource for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in AI-based parasitology research.

AI-Powered Stool Wet Mount Analysis

Performance and Validation

The implementation of AI for stool wet mount analysis demonstrates performance metrics that meet or exceed manual microscopy. A comprehensive clinical validation of a deep CNN model for enteric parasite detection reported high sensitivity and specificity, with performance further improving after a review process [29].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of an AI Model for Wet Mount Parasite Detection [29]

| Validation Metric | Initial Agreement | Post-Discrepant Resolution Agreement |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Agreement | 250/265 (94.3%) | 472/477 (98.6%) |

| Negative Agreement | 94/100 (94.0%) | Variable by organism (91.8% to 100%) |

| Additional Detections | 169 organisms not initially identified by manual microscopy | - |

Furthermore, a limit-of-detection study compared the AI model to three technologists with varying experience levels using serial dilutions of specimens containing Entamoeba, Ascaris, Trichuris, and hookworm. The AI model consistently detected more organisms at lower dilution levels than human reviewers, regardless of the technologist's experience [29]. This demonstrates the superior analytical sensitivity of AI and its potential to reduce false negatives.

Commercial AI systems, such as the Techcyte Fusion Parasitology Suite, are designed to integrate into clinical workflows. These systems can identify a broad range of parasites, including protozoan cysts and trophozoites, helminth eggs, and larvae [31]. In validation studies, such platforms have demonstrated the ability to reduce the average read time for negative slides to 15–30 seconds, allowing technologists to focus their expertise on positive or complex cases [31].

Experimental Protocol for AI-Based Wet Mount Analysis

The following protocol outlines a standard workflow for AI-assisted stool wet mount analysis, as implemented in clinical laboratories [31] [30].

Step 1: Specimen Preparation and Slide Creation

- Concentration: Process the stool specimen using a fecal concentration device (e.g., Apacor Mini or Midi Parasep) to concentrate parasitic elements.

- Slide Preparation: Create a thin monolayer of the concentrated stool on a glass slide. This is critical for optimal digital scanning, as thick preparations can obscure objects.

- Staining and Mounting: Apply a specialized mounting media, such as a wet mount iodine solution, to enhance the visibility of parasites and extend slide life. Permanently affix the coverslip using a fast-drying mounting medium to prevent movement during scanning [31] [30].

Step 2: Digital Slide Scanning

- Scanner Setup: Load the prepared slides into a compatible high-throughput digital slide scanner (e.g., Hamamatsu S360, Grundium Ocus 40).

- Image Acquisition: Initiate the scanning process. The scanner will automatically capture high-resolution digital images (typically at 40x magnification, producing 80x equivalent digital images) of the entire slide and upload them to the AI platform for analysis [31].

Step 3: AI Image Processing and Analysis

- AI Analysis: The platform's AI algorithm, typically a convolutional neural network (CNN), processes the digital images to detect, classify, and count objects of interest.

- Object Classification: The algorithm compares image features against its trained model to identify and propose classifications for parasites, grouping them by class (e.g., Giardia cysts, Trichuris eggs) and sorting them by confidence level [31] [29].

Step 4: Technologist Review and Result Reporting

- Review Interface: The technologist logs into the AI platform and reviews the AI-proposed objects of interest, which are presented in a gallery view grouped by classification.

- Confirmation and Reporting: The technologist confirms, rejects, or reclassifies the AI's findings. Positive samples are typically confirmed by manual re-inspection under a microscope. The final result is then reported into the Laboratory Information System (LIS) [31] [30].

AI-Powered Blood Smear Analysis for Parasites

Performance and Advanced Techniques

In blood smear analysis, AI is primarily applied to detect blood-borne parasites like malaria. Advanced deep learning models have been developed not only for detection but also for segmenting infected cells and classifying parasite developmental stages, which is crucial for drug development and pathogenicity studies [32] [33].

Table 2: Performance of Advanced AI Models in Blood Parasite Detection

| AI Model / Application | Key Performance Metric | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| YOLO Convolutional Block Attention Module (YCBAM) for Pinworm [34] | mAP@0.5: 0.9950, Precision: 0.9971, Recall: 0.9934 | Demonstrates high accuracy for detecting small parasitic objects in complex backgrounds. |

| Cellpose for P. falciparum Segmentation [32] | Average Precision (AP@0.5) up to 0.95 for infected erythrocytes | Enables continuous single-cell tracking and analysis of dynamic processes throughout the 48-hour parasite lifecycle. |

| Proprietary Algorithm for Malaria Stage Classification [33] | Accurate classification into rings, trophozoites, and schizonts; discrimination of viable vs. dead parasites. | Facilitates high-content drug screening by providing detailed phenotyping of drug effects. |

These models leverage sophisticated architectures. The YCBAM model, for instance, integrates YOLO with self-attention mechanisms and a Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) to focus on spatially relevant features of pinworm eggs, significantly boosting detection accuracy in noisy microscopic images [34]. For live-cell imaging, workflows combine label-free differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescence imaging with pre-trained deep-learning algorithms like Cellpose for automated 3D cell segmentation, allowing for the time-resolved analysis of processes such as protein export in Plasmodium falciparum [32].

Experimental Protocol for AI-Based Blood Smear Analysis

This protocol details a workflow for AI-driven analysis of blood smears, from preparation to the review of results, incorporating both diagnostic and research applications.

Step 1: Blood Smear Preparation and Staining

- Smear Creation: Prepare a thin blood smear on a glass slide using standard techniques to ensure an even monolayer of blood cells.

- Staining: Apply the appropriate stain (e.g., Giemsa for malaria). For advanced research applications involving live parasites, a complex staining solution may be used, including:

- A fluorescent RBC stain (e.g., wheat germ agglutinin-AlexaFluor488).

- A nuclear stain (e.g., DAPI).

- A viability stain for active mitochondria (e.g., Mitotracker Red CMXRos) [33].

Step 2: Image Acquisition

- Diagnostic Setting: Scan the slide using a supported digital scanner. In veterinary medicine, for example, systems like Vetscan Imagyst allow for automated scanning and upload to an AI analysis platform [35].

- Research Setting (High-Content Screening): Use an automated imaging platform (e.g., Operetta) to acquire multiple high-resolution image fields from multi-well plates, often using a 40x objective lens. For 3D analysis, an Airyscan microscope can be used to capture z-stacks [32] [33].

Step 3: AI Detection, Segmentation, and Classification

- Cell Detection: The AI algorithm first identifies and counts all red blood cells, separating clustered cells.

- Parasite Detection: It then detects parasitized cells based on the presence of stained parasite nuclei (DAPI) and/or mitochondrial signals (Mitotracker) [33].

- Stage Classification (Research): For malaria, the algorithm classifies the parasite's life cycle stage (ring, trophozoite, schizont) based on morphological features like nucleus number and size. It can also discriminate between viable and dead parasites based on mitochondrial activity [33].

- Segmentation (Research): Using models like Cellpose, the algorithm segments individual erythrocytes and delineates the parasite compartment within infected cells, enabling detailed spatial and temporal analysis [32].

Step 4: Result Review and Data Analysis

- Diagnostic Reporting: The technologist or veterinarian reviews the AI-generated report, which includes classified images of suspected parasites, and confirms the findings before reporting [35].

- Research Data Extraction: The analyzed data is aggregated to compute key metrics such as parasitemia, life cycle stage distribution, and viability counts for drug efficacy studies (e.g., EC50 determination) [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues essential materials and digital tools used in AI-powered parasitology research, as cited in the referenced studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Digital Tools for AI-Powered Parasitology

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Apacor Parasep [31] [30] | Fecal concentration device for preparing clean, standardized stool samples for slide preparation. | Used in the Techcyte workflow to prepare specimens for wet mount and trichrome-stained slides. |

| Techcyte AI Platform [31] [30] | A cloud-based AI software that analyzes digitized slides for ova, cysts, parasites, and other diagnostically significant objects. | Used for assisted screening in clinical parasitology, presenting pre-classified objects for technologist review. |

| Hamamatsu NanoZoomer Scanner [30] | High-throughput digital slide scanner for creating whole-slide images from glass microscope slides. | Digitizes trichrome-stained stool smears at 40x for subsequent AI analysis. |

| Cellpose [32] | A pre-trained, deep-learning-based algorithm for 2D and 3D cell segmentation. | Adapted and re-trained to segment P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes in 3D image stacks for dynamic process tracking. |

| Operetta Imaging System [33] | Automated high-content screening microscope for acquiring high-resolution images from multi-well plates. | Used in drug screening assays to image thousands of fluorescently stained malaria parasites. |

| YOLO-CBAM Architecture [34] | An object detection model (YOLO) enhanced with a Convolutional Block Attention Module for improved focus on small objects. | Developed for the highly precise detection of pinworm eggs in noisy microscopic images. |

| DAPI & Mitotracker Stains [33] | Fluorescent dyes for staining parasite nuclei and active mitochondria, respectively. | Enables algorithm discrimination between living and dead malaria parasites in viability and drug screening assays. |

| 7-Bromohept-3-ene | 7-Bromohept-3-ene|CAS 79837-80-2|Research Chemical | 7-Bromohept-3-ene is a versatile synthetic intermediate for organic synthesis. This compound is for research use only and is not intended for human or veterinary use. |

| T140 peptide | T140 Peptide | T140 peptide is a potent CXCR4 antagonist for HIV and cancer metastasis research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

The integration of AI into the analysis of stool wet mounts and blood smears represents a paradigm shift in parasitology. The data and protocols presented in this case study demonstrate that AI-powered systems offer significant advantages over traditional microscopy, including enhanced sensitivity, superior throughput, standardized interpretation, and the ability to extract complex phenotypic data for research. These technologies not only address long-standing challenges in clinical diagnostics, such as technologist burnout and diagnostic variability, but also open new avenues for scientific discovery by enabling continuous, single-cell analysis of dynamic parasitic processes. As these AI tools continue to evolve and become more accessible, they hold the promise of revolutionizing both routine parasite screening and the foundational research that underpins drug development.

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly generative AI and machine learning, with High-Throughput Screening (HTS) is revolutionizing the early stages of drug discovery. This synergy creates an iterative, data-driven cycle that significantly accelerates the identification and optimization of novel therapeutic compounds. By leveraging AI to analyze complex datasets, researchers can now prioritize compounds with a higher probability of success for experimental validation, thereby reducing the traditionally high costs and long timelines associated with drug development [36].

Within parasitology research, these technological advances hold particular promise. AI-powered microscopy and image analysis are emerging as powerful tools for identifying parasitic organisms and elucidating their complex life cycles [37]. The application of AI in this field addresses significant challenges in data integration, from various model organisms to clinical research data, paving the way for new diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies aligned with One Health principles [37].

This document provides detailed protocols for implementing an AI-assisted HTS platform, with a specific focus on its application in MoA analysis for parasitology. It includes a validated case study on kinase targets, a comprehensive table of key performance metrics, essential reagent solutions, and visualized workflows to guide researchers in adopting these transformative methodologies.

Quantitative Performance Metrics of AI in Drug Discovery

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies and reports on the impact of AI in drug discovery and related scientific fields.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics of AI in Scientific Discovery

| Metric Area | Specific Metric | Performance Result / Finding | Context / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Discovery Efficiency | Hit-to-lead cycle time reduction | 65% reduction | Integrated Generative AI & HTS platform [36] |

| Drug Discovery Output | Identification of novel chemotypes | Achieved nanomolar potency | Targeting kinases and GPCRs [36] |

| Organizational AI Maturity | Organizations scaling AI | ~33% of organizations | McKinsey Global Survey 2025 [38] |

| AI High Performers | EBIT impact from AI (≥5%) | ~6% of organizations | McKinsey Global Survey 2025 [38] |

| AI in Material Science | Candidate molecules identified | 48 promising candidates | AI-assisted HTS for battery electrolytes [39] |

| AI in Material Science | Novel additives validated | 2 (Cyanoacetamide & Hydantoin) | From 75,024 screened molecules [39] |

Integrated AI-HTS Experimental Protocol

This protocol details the procedure for establishing a synergistic cycle between generative AI and high-throughput screening to accelerate hit identification and MoA analysis.

Phase 1: Computational Design & Prioritization

Objective: To generate and virtually screen novel chemical entities optimized for specific biological targets.

Materials & Software:

- Hardware: High-performance computing (HPC) cluster or cloud-based GPU servers.

- Software: Generative AI software (e.g., for molecular design), Graph Neural Network (GNN) libraries (e.g., PyTor Geometric, DGL), molecular docking software.

- Data: Curated molecular libraries with associated biological activity data (e.g., ChEMBL, PubChem), target protein structure files (e.g., from PDB).

Procedure:

- Model Training: Train a generative AI model (e.g., a variational autoencoder or generative adversarial network) on a curated library of known molecules and their bioactivity data against the target of interest (e.g., a parasitic enzyme) [36].

- Molecular Generation: Use the trained model to generate a large library of novel molecular structures (e.g., 100,000+ compounds) optimized for desired properties like target binding affinity, solubility, and synthetic accessibility.

- High-Throughput Virtual Screening: Employ a GNN or other machine learning model to analyze the generated library based on key properties. This protocol can be adapted from a battery study where 75,024 molecules were screened based on adsorption energy, redox potential, and solubility [39]. In a drug discovery context, relevant properties include:

- Predicted binding affinity (e.g., pKi, pIC50)

- ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) properties

- Structural novelty versus known chemical libraries

- Hit Selection: Rank the molecules based on the multi-parameter analysis and select a shortlist (e.g., 48-500 compounds) for experimental synthesis and testing [36] [39].

Phase 2: Experimental Validation & HTS

Objective: To synthesize and biologically test the AI-prioritized compounds in a high-throughput manner.

Materials:

- Automated Liquid Handlers: (e.g., Tecan Veya, SPT Labtech firefly+ for miniaturized assays) [40].

- Microplate Readers: For detecting optical signals (fluorescence, luminescence, absorbance).

- Assay Reagents: Cell lines, recombinant proteins, substrates, and detection kits.

- AI-Prioritized Compounds: The shortlist of compounds from Phase 1.

Procedure:

- Synthesis: Synthesize or procure the shortlisted AI-generated compounds.

- Assay Development: Configure a target-based (e.g., enzyme inhibition) or phenotypic assay (e.g., parasite viability) in a microplate format compatible with automation.

- Automated Screening: Use liquid handling robots to dispense compounds, cells/enzmyes, and reagents into assay plates. The focus should be on robustness and reproducibility to generate high-quality data for the AI model [40].

- Data Acquisition: Read plates using appropriate detectors to generate primary activity data (e.g., % inhibition, IC50 values).

Phase 3: MoA Analysis via AI-Powered Image Analysis

Objective: To elucidate the Mode of Action of confirmed hits using high-content imaging and AI-driven analysis.

Materials:

- High-Content Imaging System: Automated microscope capable of high-throughput multiplexed imaging.

- Staining Reagents: Antibodies for specific cellular targets, fluorescent dyes for organelles, and viability indicators.

- AI Software: Image analysis platforms with deep learning capabilities (e.g., Sonrai Discovery, open-source tools like CellProfiler with TensorFlow integration) [40].

Procedure:

- Cell Treatment & Staining: Treat relevant cell models (e.g., infected host cells) with confirmed hit compounds and appropriate controls. Fix and stain cells with multiplexed biomarker panels.

- High-Content Imaging: Automatically acquire thousands of high-resolution images across multiple channels for each treatment condition.

- AI-Based Image Segmentation & Classification:

- Train a deep learning model (e.g., a U-Net architecture) to accurately segment individual cells and sub-cellular structures. This approach is directly applicable to parasitology, as demonstrated in studies of Apicomplexan and Kinetoplastid groups [37].

- Extract hundreds of morphological features (e.g., texture, shape, intensity) from the segmented cells to create a quantitative "phenotypic fingerprint" for each treatment.