Habitat Fragmentation and Parasite Dynamics: Ecological Disruption, Modeling Approaches, and Biomedical Implications

Anthropogenic habitat loss and fragmentation profoundly disrupt parasite transmission dynamics and host-parasite coevolution, with significant consequences for ecosystem stability and potential implications for disease control. This article synthesizes current research to explore the fundamental mechanisms through which landscape alteration impacts parasites with varying life cycles, examines advanced modeling frameworks for predicting these effects, and addresses challenges in translating ecological findings into sustainable biomedical and conservation strategies. By integrating empirical evidence from diverse wildlife systems with methodological advances in ecological modeling, we provide a comprehensive resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to understand how environmental change influences parasitic diseases and their management.

Habitat Fragmentation and Parasite Dynamics: Ecological Disruption, Modeling Approaches, and Biomedical Implications

Abstract

Anthropogenic habitat loss and fragmentation profoundly disrupt parasite transmission dynamics and host-parasite coevolution, with significant consequences for ecosystem stability and potential implications for disease control. This article synthesizes current research to explore the fundamental mechanisms through which landscape alteration impacts parasites with varying life cycles, examines advanced modeling frameworks for predicting these effects, and addresses challenges in translating ecological findings into sustainable biomedical and conservation strategies. By integrating empirical evidence from diverse wildlife systems with methodological advances in ecological modeling, we provide a comprehensive resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to understand how environmental change influences parasitic diseases and their management.

Mechanisms of Disruption: How Habitat Fragmentation Alters Parasite Transmission and Evolutionary Dynamics

Habitat loss and fragmentation (HLF) represents one of the most critical anthropogenic threats to global biodiversity, with profound implications for species persistence and ecological interactions [1]. While the direct consequences of HLF on population decline and range contraction are well-documented, the mechanisms through which HLF disrupts coevolutionary dynamics between species, particularly hosts and parasites, remain less explored [1] [2]. This technical review examines the cascading effects of habitat fragmentation on parasite dynamics through both direct and indirect pathways, with particular emphasis on how these disruptions alter coevolutionary trajectories. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for predicting disease emergence, managing ecosystem health, and conserving species interactions in fragmented landscapes.

The thesis of this work posits that habitat fragmentation not only directly reduces population viability through demographic processes but also indirectly destabilizes coevolutionary relationships by altering the spatial and genetic context of species interactions. This dual pathway framework provides a comprehensive lens through which to analyze the full ecological consequences of landscape change.

Direct Pathways: Population and Metacommunity Consequences

Habitat fragmentation initiates direct demographic and genetic consequences that propagate through ecological networks. These direct effects primarily operate through population decline and metapopulation destabilization.

Demographic Consequences of Habitat Fragmentation

Table 1: Direct Effects of Habitat Fragmentation on Host and Parasite Populations

| Direct Mechanism | Effect on Host Populations | Effect on Parasite Populations | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduced habitat area | Population decline, reduced carrying capacity | Decreased transmission opportunities, increased extinction risk | Cuckoo extinction risk significantly increased under severe HLF [1] |

| Restricted movement | Limited dispersal, gene flow disruption | Reduced host finding capability, isolation | Animal movement and gene flow restriction [1] |

| Range contraction | Reduced genetic diversity, inbreeding | Limited host switching opportunities | Direct population decline and range contraction [1] |

| Patch size reduction | Edge effects, reduced resource availability | Constrained parasitism behavior, adaptive flexibility loss | Lower reproductive profit in smaller patches [1] |

The direct pathway begins with habitat loss reducing the available area for populations, immediately lowering carrying capacity and increasing extinction vulnerability [1]. As noted in studies of cuckoo-host systems, "severe HLF significantly increases the cuckoo's extinction risk compared to moderate HLF" [1]. This differential susceptibility between species initiates the disruption of specialized relationships.

Metacommunity and Connectivity Effects

Spatially explicit metacommunity models demonstrate that landscape configuration directly modulates parasite distribution and host-parasite encounter rates. Research shows that "landscapes with a higher amount of natural cover and lower fragmentation level dilute the distribution of parasites throughout the host community," whereas "highly degraded, fragmented landscapes constrain host-parasite dispersal" [2]. This direct limitation of dispersal capability fragments interaction networks and reduces the scale of coevolutionary processes.

Indirect Pathways: Disruption of Coevolutionary Dynamics

Beyond direct demographic effects, habitat fragmentation exerts powerful indirect influences by altering the evolutionary context of host-parasite interactions. These indirect pathways often produce more persistent and complex disruptions to coevolutionary dynamics.

Alteration of Coevolutionary Trajectories

Table 2: Indirect Effects of Habitat Fragmentation on Coevolutionary Dynamics

| Indirect Mechanism | Effect on Coevolution | Outcome for Host-Parasite Systems | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Restricted host rejection rate range | Narrowed adaptive window for arms race | Increased extinction risk for parasites | Severe HLF narrows range of host rejection rates [1] |

| Shift in interaction network structure | More heterogeneous, divergent coevolution | Emergence of novel parasite variants | Fragmented landscapes promote divergent coevolutionary dynamics [2] |

| Altered resource competition | Modified fluctuating selection dynamics | Enhanced or suppressed Red Queen dynamics | Coinfections alter fluctuating selection depending on characteristics [3] |

| Reduced host diversity | Simplified host community, altered selection pressures | Impact on parasite host range | Loss of habitat reduces host diversity [2] |

The indirect pathway operates largely through the disruption of the coevolutionary arms race equilibrium. In brood parasitism systems, a critical factor maintaining stability is "the host's adaptable range of rejection rates (RR) to exotic egg they may recognize based on its morphological traits" [1]. Habitat fragmentation constrains this adaptive range, thereby destabilizing the balanced antagonism. As the model simulations demonstrate, "severe HLF narrows the range of host rejection rates that allow cuckoo populations to persist under natural conditions" [1].

Modification of Fluctuating Selection Dynamics

Coevolutionary interactions typically exhibit fluctuating selection dynamics (Red Queen dynamics), where host and parasite genotypes cycle in frequency-dependent patterns. Habitat fragmentation can fundamentally alter these dynamics through multiple indirect mechanisms:

Coinfection Effects: The presence of multiple parasite species modifies selection pressures. "Coinfections can enhance fluctuating selection dynamics when they increase fitness costs to the hosts" [3]. Under resource competition, coinfections "can either enhance or suppress fluctuating selection dynamics, depending on the characteristics (i.e., fecundity, fitness costs induced to the hosts) of the interacting parasites" [3].

Protective Symbiosis: Microbial protection can alter host-parasite coevolution by favoring tolerance mechanisms over resistance strategies, thereby shifting evolutionary trajectories [4].

Dilution Landscapes: The dilution effect—whereby diverse host communities reduce parasite transmission—becomes spatially structured in fragmented landscapes. "Landscapes with a higher amount of natural cover and lower fragmentation level dilute the distribution of parasites throughout the host community and lead to more homogenous coevolutionary trajectories" [2].

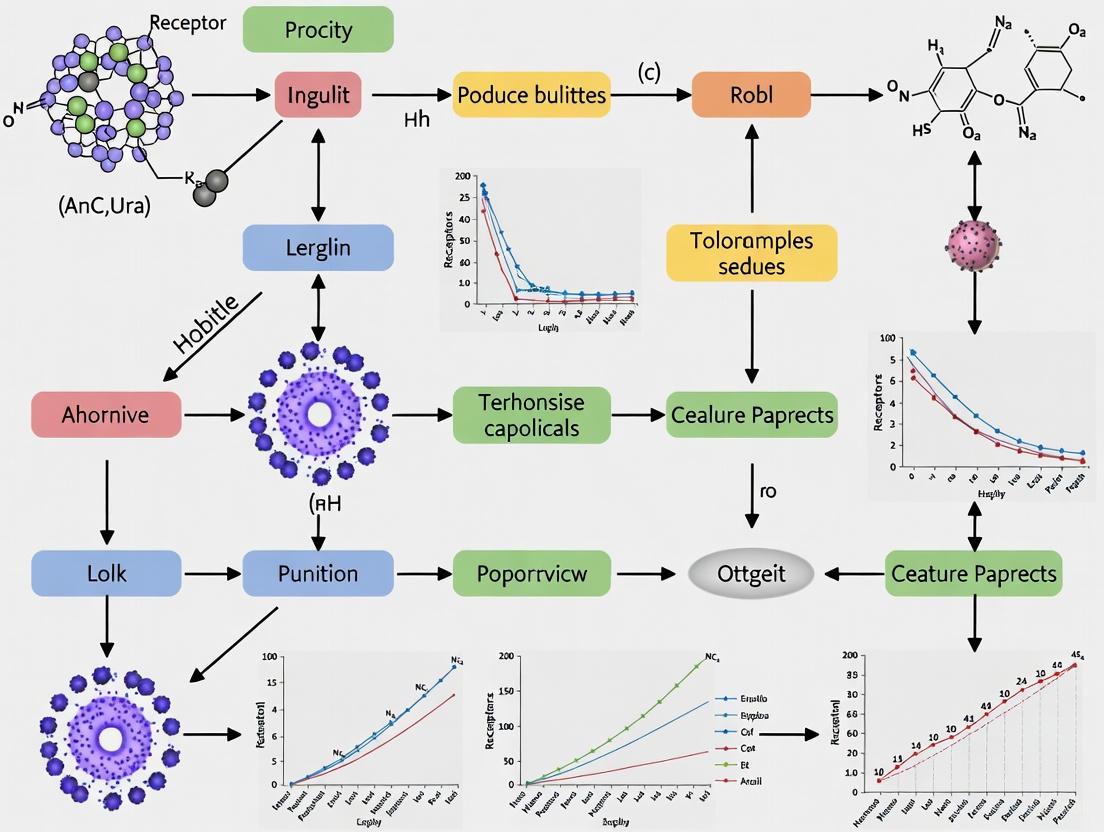

Diagram 1: Direct and indirect pathways from habitat fragmentation to coevolutionary disruption. This visualization shows the conceptual framework of how habitat fragmentation affects host-parasite systems through multiple interconnected pathways.

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Research in this field employs integrated methodological approaches combining theoretical models, empirical observation, and experimental manipulation to unravel the complex relationships between habitat fragmentation and coevolutionary dynamics.

Individual-Based Simulation Modeling

Protocol 1: Individual-Based Brood Parasitism Simulation [1]

Model Initialization:

- Parameterize cuckoo groups with lifespan, egg number, host species number, initial population, and probabilistic traits (laying success, deception capability)

- Parameterize host groups with lifespan, egg number, parasite species number, initial/maximum population sizes, and antiparasitism behaviors

- Assign individual variation using stochastic processes: uniform distributions for categorical variables, truncated normal distributions for probabilistic parameters, truncated Weibull for lifespan, truncated Poisson for egg number

Simulation Processes:

- Mating and egg generation: Polygamous strategy for cuckoos, monogamous for hosts

- Egg parasitizing: Define probability of successful egg laying in host nests and probability of preventing egg replacement

- Incorporate both inherited traits (genetic) and reinforcement learning (experiential) components

HLF Implementation:

- Simulate moderate vs. severe HLF scenarios by varying proportion of suitable habitat

- Track population trajectories and rejection rate adaptation across generations

- Validate model outputs with empirical data on brood parasitism systems

Spatially Explicit Metacommunity Framework

Protocol 2: Dilution Landscape Assessment [2]

Landscape Characterization:

- Quantify natural vegetation cover using remote sensing data (e.g., satellite imagery)

- Measure fragmentation metrics: patch size, connectivity, edge-to-area ratio

- Classify landscapes along gradients of cover amount and configuration

Host-Parasite Sampling:

- Establish transects or sampling grids across fragmentation gradients

- Conduct standardized host and parasite surveys across multiple seasons

- Document interaction networks through direct observation and molecular methods

Eco-evolutionary Dynamics Analysis:

- Measure parasite distribution across host community

- Track coevolutionary trajectories using molecular markers and phenotypic assays

- Analyze network structure and host switching events

- Correlate landscape metrics with coevolutionary outcomes

Fluctuating Selection Assessment with Coinfections

Protocol 3: Numerical Simulation of Coinfection Effects [3]

Model Framework:

- Implement matching allele model for genetically specific parasites

- Include generalist parasite species with different infection mechanisms

- Configure host population with nine genotypes to maintain ecological relevance

Simulation Scenarios:

- Baseline: Single specific parasite species

- Coinfection with increased host fitness costs

- Coinfection with resource competition between parasites

- Vary parasite characteristics: fecundity, virulence, transmission efficiency

Dynamics Tracking:

- Monitor host and parasite genotype frequencies over generations

- Calculate amplitude and periodicity of fluctuations

- Assess conditions for enhancement/suppression of fluctuating selection

Diagram 2: Methodological framework for studying fragmentation effects on coevolution. This experimental workflow integrates landscape characterization, field sampling, laboratory analysis, and theoretical modeling to comprehensively assess how habitat fragmentation disrupts host-parasite coevolution.

Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Host-Parasite Coevolution Studies

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Analysis Tools | Microsatellite markers, SNP panels, whole-genome sequencing | Track genotype frequency changes, identify selection signatures | Required for fluctuating selection dynamics assessment [3] |

| Landscape Metrics | Fragmentation indices, connectivity measures, vegetation cover maps | Quantify habitat configuration and loss | Remote sensing data essential for spatial analysis [2] |

| Population Modeling | Individual-based models, metacommunity frameworks, stochastic simulations | Project population trajectories under HLF scenarios | Must incorporate both ecological and evolutionary processes [1] |

| Parasite Screening Methods | Molecular barcoding, morphological identification, prevalence assessment | Document parasite communities and infection rates | Critical for measuring dilution effects and coinfection rates [3] [2] |

| Behavioral Assays | Host rejection rate tests, parasitism behavior observation | Quantify coevolutionary traits and adaptations | Essential for measuring arms race dynamics [1] |

| Network Analysis | Interaction matrices, connectivity metrics, modularity analysis | Visualize and quantify host-parasite interaction structures | Reveals how fragmentation alters community organization [2] |

| Tetrahydropalmatrubine | Tetrahydropalmatrubine Reference Standard|Research Use Only | High-purity Tetrahydropalmatrubine for research. Explore the potential of this natural alkaloid. For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Cnidioside B | Cnidioside B, MF:C18H22O10, MW:398.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The investigation of direct and indirect pathways from population decline to coevolutionary disruption reveals the multifaceted impacts of habitat fragmentation on host-parasite systems. Direct pathways operate through demographic constraints—reducing population sizes, restricting movement, and limiting gene flow. Indirect pathways manifest through the disruption of coevolutionary processes—altering selection pressures, modifying interaction networks, and shifting evolutionary trajectories.

The evidence from theoretical models, empirical studies, and experimental simulations consistently demonstrates that severe habitat loss and fragmentation not only increase extinction risk for individual species but also destabilize the delicate balance of coevolutionary relationships. These disruptions can lead to divergent evolutionary pathways, emergence of novel parasite variants, and modified disease risk profiles with potential implications for human and wildlife health.

Future research should prioritize integrated approaches that combine landscape ecology, evolutionary biology, and disease ecology to better predict the consequences of ongoing habitat fragmentation. Conservation strategies must recognize that maintaining functional connectivity preserves not only species but also the evolutionary processes that shape ecological communities.

Life Cycle Complexity as a Critical Vulnerability Factor

Habitat loss and fragmentation (HLF) is a dominant driver of global biodiversity change, but its effects on parasitic organisms have been historically overlooked. Within this context, parasites with complex life cycles (CLPs)—those requiring multiple, specific host species to complete their development—emerge as being disproportionately vulnerable to environmental disruption. These parasites represent a significant portion of global biodiversity and play indispensable roles in ecosystem stability by modulating host population dynamics and facilitating energy transfer through trophic levels [5] [6]. The fragility of CLPs stems from their reliance on intricate ecological networks; the disruption of any single host population or the abiotic conditions required for transmission can collapse the entire lifecycle [5]. This whitepaper synthesizes current research to establish life cycle complexity as a critical vulnerability factor, detailing the mechanisms of impact, quantitative evidence, and essential methodologies for researchers studying parasite dynamics in fragmented landscapes.

Empirical Evidence and Quantitative Impacts

Key Studies Demonstrating Vulnerability

Recent empirical studies consistently demonstrate that habitat fragmentation negatively impacts parasites with complex life cycles, while those with simple, direct life cycles may be less affected or even benefit.

Table 1: Impacts of Habitat Fragmentation on Parasites with Different Life Cycles

| Life Cycle Type | Representative Taxa | Documented Impact of Fragmentation | Proposed Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complex (Heteroxenous) | Strongyloides spp., Cestodes, Trematodes [5] [6] | Significant reduction in prevalence and species richness [5] | Disruption of host species networks; unfavorable abiotic conditions for free-living stages or intermediate hosts [5] |

| Simple (Homoxenous) | Lemuricola (pinworm), Enterobiinae [5] | Increase or variable response in prevalence [5] | Host crowding in fragments increases transmission efficiency for directly transmitted parasites [5] |

A 2021 study in the fragmented dry forests of Northwestern Madagascar provides compelling field evidence. Research on gastrointestinal parasites in four small mammal hosts revealed that habitat fragmentation and vegetation clearance negatively affected parasites with heteroxenous (indirect) cycles or those with heterogenic environments, consequently reducing overall gastrointestinal parasite species richness (GPSR) [5]. The study proposed that forest edges and degradation change abiotic conditions (e.g., temperature, humidity), reducing habitat suitability for soil-transmitted helminths or required intermediate hosts, such as arthropods [5]. In contrast, the prevalence of homoxenous parasites like Lemuricola was positively associated with forest maturation, suggesting that host density or behavior in older fragments facilitates direct transmission [5].

Theoretical Models and Coevolutionary Disruption

The vulnerability of CLPs is further corroborated by mathematical and simulation models. A cuckoo-host brood parasitism model, validated with empirical data, revealed that severe HLF significantly increases the extinction risk of the parasitic cuckoo compared to moderate fragmentation [1]. This model illustrated that severe HLF narrows the range of adaptable host rejection rates that allow for cuckoo population persistence, thereby disrupting the coevolutionary arms race and pushing the system toward extinction [1].

Similarly, models exploring multiple parasites sharing an intermediate host show that their coexistence is fragile. Parasites that manipulate intermediate host behavior to facilitate transmission to a definitive host face "dead-ends" if manipulation also increases predation by non-host predators [7]. Community dynamics exhibiting strong fluctuations can disrupt the delicate balance enabling parasite coexistence, suggesting that environmental disturbances like fragmentation can cause regime shifts and a loss of parasite diversity [7].

Table 2: Model-Based Insights into CLP Vulnerability

| Model Type | System | Key Finding on Vulnerability |

|---|---|---|

| Individual-Based Stochastic Simulation [1] | Cuckoo-Host Brood Parasitism | Severe habitat loss and fragmentation narrows the range of host rejection rates that allow parasite persistence, increasing extinction risk. |

| Population Dynamics Model [7] | Multi-Parasite, Single Intermediate Host | Coexistence of host-manipulating parasites is susceptible to environmental disturbances due to regime shifts. |

Mechanisms Underlying the Vulnerability of Complex Life Cycles

The increased susceptibility of CLPs to habitat fragmentation arises from several interconnected mechanistic pathways:

- Dependence on Trophic Networks: CLPs depend on predictable trophic interactions between their intermediate and definitive hosts. Habitat fragmentation can disrupt these food webs, leading to the local loss of a required host species. Without all necessary hosts present in the correct sequence, the parasite lifecycle cannot be completed [5] [7].

- Abiotic Sensitivity of Free-Living Stages and Intermediate Hosts: Many CLPs have free-living stages (e.g., trematode miracidia) or rely on invertebrate intermediate hosts (e.g., arthropods, mollusks) that are highly sensitive to microclimatic changes. Forest edges and degraded habitats often have higher temperatures and lower humidity, creating unfavorable conditions that reduce the survival and effectiveness of these transmission stages [5].

- Disruption of Host Manipulation Strategies: Some CLPs manipulate the behavior of their intermediate host to increase predation by the definitive host. Fragmentation can alter predator communities or host densities, causing this manipulation to result in "dead-end" predation by a non-host species, thereby terminating the parasite's life cycle [7].

- Breaking Coevolutionary Dynamics: As shown in the cuckoo-host model, fragmentation can disrupt the delicate equilibrium of coevolutionary arms races. The altered selective pressures in fragments may favor host defenses to which the parasite cannot rapidly adapt, leading to parasite extinction [1].

Essential Methodologies for Assessing Vulnerability

Field Sampling and Parasitological Examination

Robust field studies are fundamental for documenting parasite responses to fragmentation.

Experimental Protocol: Host Capture and Sample Collection

- Host Trapping: Systematically trap small mammal or other target host species across a gradient of habitat fragments and continuous forest sites using standardized methods (e.g., live traps) [5] [8].

- Sample Collection: Collect fecal samples (e.g., 1-5 g per individual) directly from trapped animals or their sleeping sites. Store samples in preservative (e.g., 10% formalin, 70% ethanol) for later analysis [5].

- Necropsy for Endo- and Ectoparasites: For a subset of individuals, conduct full necropsy following ethical guidelines. Examine the host's coat, gastrointestinal tract, body cavity, and other organs. Preserve all recovered parasites in ethanol or other suitable fixatives for morphological identification and molecular analysis [8].

- Data Recording: Record essential metadata for each host individual, including species, sex, body mass, reproductive condition, and precise location of capture (GPS coordinates). Note habitat variables such as forest type, fragment size, and distance to the nearest edge [5] [8].

Experimental Protocol: Coproscopical Analysis

- Fecal Smear: Prepare a thin smear of feces on a microscope slide with a drop of saline. Examine under a light microscope at 100x and 400x magnification for parasite eggs, larvae, or cysts [5].

- Fecal Flotation: Use standardized flotation techniques (e.g., with saturated sugar or salt solution) to concentrate parasite propagules for identification and quantification [5].

- Morphotyping: Identify parasite taxa based on the size, shape, and color of eggs, larvae, or cysts. Differentiate morphotypes and quantify infection intensity (e.g., eggs per gram) [5].

Diagram 1: Field and Lab Workflow for Parasite Community Studies.

Statistical Modeling of Parasite Communities

To disentangle the effects of fragmentation from other variables and detect parasite-parasite interactions, advanced statistical models are required.

- Experimental Protocol: Hierarchical Joint Species Distribution Modeling (HSDM)

- Data Matrix Construction: Create a presence-absence matrix (Y matrix) where rows represent individual host animals and columns represent parasite species [8].

- Incorporating Fixed and Random Effects: Define fixed effects (X matrix), such as host sex or body condition. Include community-level random effects to account for spatial (site, fragment), temporal (year, season), and host phylogenetic structure [8].

- Model Fitting: Use frameworks like Hierarchical Modeling of Species Communities (HMSC) to fit the model. This approach allows quantification of the residual associations between parasite species pairs after accounting for all environmental and host variables [8].

- Interpretation: Positive residual associations may indicate facilitation or correlated responses to unmeasured variables, while negative associations suggest potential competition, particularly between parasites infecting the same host tissue [8].

Individual-Based Simulation Modeling

For projecting long-term coevolutionary and population dynamics, simulation models are invaluable.

- Experimental Protocol: Building a Cuckoo-Host Stochastic Simulation

- Parameter Initialization: Initialize virtual populations of parasites and hosts. Assign life-history parameters (lifespan, egg number, etc.) probabilistically using truncated normal, Poisson, or Weibull distributions to reflect natural variation [1].

- Define Core Processes: Program iterative processes for mating, egg generation (with stochastic inheritance of traits), and parasitizing behaviors. Incorporate a reinforcement learning component to allow for adaptive behavior based on experience [1].

- Incorporate Habitat Structure: Define the landscape as a set of patches with varying degrees of connectivity and quality. Link habitat configuration to key model parameters, such as the probability of host-parasite encounter or the cost of movement [1].

- Run Simulations and Validate: Run multiple stochastic simulations under different HLF scenarios (e.g., moderate vs. severe). Validate model outputs with empirical data on population trends and behavioral adaptations where available [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Parasite Dynamics Research

| Item/Tool | Function/Application | Example Use in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq) [9] | Profiling gene expression of individual parasite cells or host cells during infection. | Investigating parasite development, drug resistance mechanisms, and host immune responses. |

| paraCell Software [9] | User-friendly, interactive analysis and visualization of host-parasite scRNA-seq data. | Enabling parasitologists without advanced bioinformatics skills to explore gene expression datasets. |

| Ethanol & Formalin [5] [8] | Preservation of fecal samples and recovered parasites for morphological and molecular study. | Maintaining structural integrity of parasite specimens for later identification and DNA analysis. |

| Hierarchical Modeling of Species Communities (HMSC) [8] | Statistical framework for analyzing multi-species communities and detecting species associations. | Quantifying the impact of habitat variables on parasite communities and detecting parasite-parasite interactions. |

| Stochastic Individual-Based Models [1] | Simulating population and evolutionary dynamics by tracking individuals and their traits. | Forecasting the long-term impact of habitat fragmentation on parasite-host coevolution and extinction risk. |

| Tanshinoic acid A | Tanshinoic acid A, MF:C18H14O5, MW:310.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Kuwanon W | Kuwanon W, MF:C45H42O11, MW:758.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Diagram 2: Mechanisms Linking Habitat Fragmentation to CLP Vulnerability.

Host Specificity and Behavioral Adaptations in Fragmented Landscapes

Habitat fragmentation, the process by which continuous habitats are subdivided into smaller, isolated patches, is a dominant driver of global biodiversity loss. This paper examines its profound effects on host-parasite dynamics and the subsequent behavioral adaptations of wildlife. Fragmentation influences parasite exposure and transmission by altering species composition, population densities, and interspecific interactions [10]. Furthermore, it imposes novel selective pressures that shape the behavioral strategies hosts employ to manage parasitic infections [11]. Understanding the interface of fragmentation, behavior, and parasitism is therefore critical for predicting disease outcomes and developing effective conservation strategies in human-altered landscapes. This review synthesizes current experimental evidence and theoretical frameworks to explore these complex relationships.

The Impact of Habitat Fragmentation on Ecological Networks and Specialization

Habitat fragmentation acts as a powerful ecological filter, reshaping communities by selectively eliminating species based on their traits and interaction specificities. A synthesis of long-term experiments demonstrates that fragmentation reduces biodiversity by 13–75% and impairs key ecosystem functions [10]. These effects are most pronounced in the smallest and most isolated fragments.

Network-Level Changes and the Loss of Specialists

Table 1: Effects of Habitat Fragmentation on Ecological Network Properties

| Network Property | Effect of Fragmentation | Ecological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Specialization | Increases in mutualistic and antagonistic networks on smaller, more isolated islands [12] | Food webs become dominated by generalist species; specialized interactions are lost. |

| Connectance | Increases on smaller islands in plant-frugivore networks [13] | Remaining species interact with a wider range of partners, leading to denser networks. |

| Modularity | Decreases on smaller islands in plant-frugivore networks [13] | Networks become less subdivided into distinct, tightly-knit subgroups of species. |

| Nestedness | Decreases on smaller islands in plant-frugivore networks [13] | The structured pattern where specialists interact with generalists breaks down. |

| Interaction Rewiring | Plays a minor role compared to species turnover in driving network changes [12] | Changes in network structure are primarily due to the loss/gain of species, not behavioral flexibility. |

The mechanisms underlying these network changes are driven more by species turnover—the loss of specialist species and their specific interactions—than by behavioral flexibility, or interaction rewiring, of the remaining species [12]. This loss of specialists includes large-bodied frugivorous birds and their associated seed dispersal services [13], as well as grassland birds with high habitat specialization [14]. The result is a simplified ecological community dominated by generalist species with broader ecological niches.

Trait-Based Responses to Fragmentation

Species' functional traits determine their vulnerability to fragmentation. Research on steppe birds reveals that species with medium hand-wing indices, moderate body mass, and larger range sizes are more likely to occupy heavily fragmented habitats [14]. These traits are associated with greater dispersal ability and lower ecological specialization, allowing such species to persist in patchy environments.

Parasite-Induced Behavioral Alterations in a Fragmentation Context

Host behavior is a critical interface between parasitism and fragmentation, influencing both exposure to parasites and the energetic cost of infections.

Sickness Behavior: Adaptive Response or Pathological Debilitation?

Observational and experimental studies consistently document "sickness behaviors" in infected hosts, including reduced foraging, less movement, and increased resting time [11]. These behavioral changes have been interpreted as an adaptive strategy to conserve energy for immune function and avoid new infections. However, an alternative hypothesis posits they are a direct pathological effect of parasites, debilitatin g the host.

Experimental Evidence: The Modulating Role of Food Availability

A key experiment on wild black capuchin monkeys (Sapajus nigritus) manipulated both helminth infections (via antiparasitic drugs) and food availability (via banana provisioning) [11]. This study provided the first experimental evidence that the impact of parasites on host behavior is modulated by nutritional status.

Table 2: Summary of Capuchin Monkey Experiment: Interactions Between Parasitism and Food Availability

| Experimental Treatment | Impact on Foraging Behavior | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Low Food, No Antiparasitic (F- A-) | Significantly reduced foraging | Parasite infection supresses foraging when energy is scarce. |

| Low Food, Antiparasitic (F- A+) | Increased foraging compared to (F- A-) | Parasite removal frees up energy for foraging. |

| High Food, No Antiparasitic (F+ A-) | Foraging similar to dewormed individuals | Abundant food compensates for the energetic cost of infection. |

| High Food, Antiparasitic (F+ A+) | Foraging similar to other high-food groups | High energy intake and lack of parasites. |

The findings that infected hosts only reduced foraging under low-food conditions, and that provisioning did not increase resting time, are more consistent with the debiliation hypothesis than with an adaptive "sickness behavior" strategy in this case [11]. This suggests that in fragmented habitats where resources are often limited, the compounded effects of poor nutrition and parasitism could lead to severe behavioral and fitness consequences.

Methodologies for Studying Host-Parasite Dynamics in Fragmented Landscapes

Key Experimental Protocols

1. Whole-Ecosystem Fragmentation Experiments: The most robust insights come from long-term, whole-ecosystem experiments that actively manipulate habitat size and isolation while controlling for habitat loss [10]. These studies involve:

- Establishing replicate landscapes with defined fragments of different sizes (e.g., from 1 ha to 100 ha).

- Creating cleared areas to serve as matrix and achieve desired levels of isolation.

- Long-term monitoring of species abundances, dispersal, extinction, and ecosystem functions (e.g., biomass, nutrient cycling) in the fragments versus control continuous habitats [10].

2. Tri-Trophic Interaction Sampling: To study complex interactions like plant-aphid-ant systems, researchers use standardized transect surveys on habitat islands [12].

- Visual Screening: All woody and herbaceous plants along transects are inspected for aphids and interacting ants.

- Voucher Collection: Specimens of aphids and ants are collected for morphological and genetic identification.

- Interaction Recording: Each observed event of an ant species interacting with an aphid species on a specific plant is recorded as a unique interaction, regardless of the number of individuals involved [12].

3. Controlled Manipulation of Parasites and Resources: The capuchin monkey study exemplifies a rigorous protocol for testing causal relationships [11].

- Antiparasitic Treatment: A randomly selected half of the adults in a group receive a broad-spectrum antiparasitic drug cocktail (e.g., ivermectin and praziquantel), while the other half serves as a control.

- Food Provisioning: Groups are subjected to different provisioning regimes (e.g., high vs. low amounts of bananas) to manipulate nutritional status.

- Behavioral Data Collection: Focal animal sampling is used to collect detailed data on activity budgets (foraging, moving, resting) and social proximity.

- Parasite Load Quantification: Fecal samples are regularly collected to determine the intensity of helminthic infections.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Field Research

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Antiparasitic Drug Cocktail (e.g., Ivermectin & Praziquantel) | Experimentally reduces intensity of helminth (nematode, cestode) and ectoparasite infections in study animals [11]. |

| Camera Traps (Arboreal & Terrestrial) | Non-invasive, cost-effective method for recording species presence and interspecific interactions (e.g., plant-frugivore) over long periods at multiple sites [13]. |

| Ethanol (95%) | Standard preservative for invertebrate voucher specimens (e.g., aphids, ants) collected for morphological identification and DNA barcoding [12]. |

| Genetic Database Access (e.g., GenBank) | Repository for DNA barcode sequences used to confirm species identifications of collected specimens [12]. |

| Global Positioning System (GPS) & GIS Software | Precisely maps fragment boundaries, calculates area and isolation metrics, and plans transect layouts [10]. |

| Isomaltopaeoniflorin | Isomaltopaeoniflorin |

| SARS-CoV-2 Mpro-IN-9 | SARS-CoV-2 Mpro-IN-9, MF:C20H14N2O4, MW:346.3 g/mol |

Conceptual Framework and Visualizations

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual framework linking habitat fragmentation to changes in host-parasite dynamics and behavioral adaptations, integrating the key findings discussed in this review.

Figure 1: A conceptual model of how habitat fragmentation influences host-parasite dynamics and behavior. Key pathways show fragmentation altering species communities and host nutrition, which in turn affect parasite exposure and trigger behavioral changes with consequences for host fitness.

The experimental workflow for disentangling the effects of parasitism and food availability on host behavior, as demonstrated in the capuchin monkey study, is outlined below.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for manipulating parasite load and food availability to assess their interactive effects on host behavior, based on the capuchin monkey study [11].

Edge Effects and Microclimatic Changes on Free-Living Parasite Stages

Habitat fragmentation creates distinct boundaries between ecosystem patches, resulting in edge effects that alter microclimatic conditions including temperature, humidity, and light exposure [15]. These altered abiotic parameters critically influence the development, survival, and transmission potential of free-living parasite stages across diverse ecosystems. For parasites with complex life cycles involving environmental stages, these microclimatic shifts can create tipping points that dramatically alter transmission dynamics [16] [17]. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for predicting disease outcomes in fragmented landscapes and developing targeted interventions for parasitic diseases affecting humans, livestock, and wildlife.

This technical guide synthesizes current research on how edge-induced microclimatic changes affect parasite ecology, with particular emphasis on experimental approaches for quantifying these relationships and their implications for disease control strategies in anthropogenically modified landscapes.

Conceptual Framework and Key Mechanisms

Defining Edge Effects in Parasite Ecology

Edge effects refer to changes in biological and physical conditions that occur at ecosystem boundaries. In the context of parasite transmission, these effects manifest through several interconnected pathways:

- Microclimatic Gradients: Abrupt transitions between vegetation types create sharp variations in temperature, humidity, solar radiation, and wind exposure [15]. These altered conditions directly impact the development rates and survival of free-living parasite stages.

- Host Distribution Changes: Edge habitats often attract different host assemblages compared to interior habitats, potentially altering transmission pathways and amplifying parasite loads at boundaries [15] [18].

- Behavioral Modifications: Host movement patterns and resource utilization may shift in edge habitats, changing encounter rates with infective parasite stages in the environment.

These edge-induced modifications can either facilitate or inhibit parasite transmission depending on the specific physiological requirements of each parasite species and the nature of the microclimatic changes.

Microclimatic Parameters Affecting Free-Living Stages

The free-living stages of parasites (eggs, larvae, spores) exhibit species-specific responses to key microclimatic variables as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Microclimatic parameters affecting free-living parasite stages

| Parameter | Effect on Free-Living Stages | Parasite Example | Impact Magnitude |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Increased development rate; Reduced survival at extremes | Livestock nematodes [16] | Nonlinear response with critical threshold at ~2-3°C increase [16] |

| Relative Humidity | Increased survival and infectivity | Avian ectoparasites [19] | 4.93% decrease in RH reduced blowfly abundance significantly [19] |

| Soil Moisture | Enhanced larval migration and host finding | Gastro-intestinal nematodes [20] | Varies with precipitation patterns and drainage |

| Solar Radiation | Increased mortality of exposed stages | Avian nest parasites [19] | UV exposure lethal to many larval forms |

The interaction of these parameters often creates nonlinear responses in parasite population dynamics, where small changes in microclimate can trigger disproportionately large changes in transmission potential [16] [17]. For instance, temperature increases may simultaneously accelerate parasite development while reducing survival, creating complex, countervailing effects on overall transmission rates.

Quantitative Evidence and Experimental Data

Documented Microclimatic Impacts on Parasite Dynamics

Experimental manipulations and observational studies across diverse systems have quantified how edge-induced microclimates affect parasite success. Key findings are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Experimental evidence of edge effects on parasite dynamics

| Parasite System | Experimental Manipulation | Microclimatic Change | Effect on Parasites |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avian nest ectoparasites [19] | Nest box heating (2.24°C increase at night) | +2.24°C, -4.93% RH (Spain); +1.35°C, -0.82% RH (Germany) | Blowfly pupae significantly reduced; Flea larvae reduced (Spain only) |

| Livestock gastrointestinal nematodes [16] | Modeled development rate changes | Development rate: 0.00002 to 0.0002 minâ»Â¹ | Nonlinear response; tipping points in outbreak dynamics |

| Migratory wildlife GIN [20] | Dung addition and grazing manipulation | Not directly measured but inferred from habitat use | Transport effects increased larvae; Trophic effects reduced larvae |

These studies demonstrate that temperature modifications of just 1-3°C can produce biologically significant changes in parasite abundance and transmission dynamics. The specific direction and magnitude of these effects depend on the parasite species, local context, and interaction with other environmental variables.

Tipping Points and Nonlinear Responses

Process-based modeling of livestock nematodes reveals that temperature-sensitive parameters can trigger nonlinear responses in outbreak dynamics [16]. Small changes in development rates around critical thresholds resulted in dramatic, disproportionate changes in parasite burdens. Specifically:

- Development rate increases from 0.00002 to 0.0002 minâ»Â¹ (equivalent to development times from ~35 days to ~3 days) created distinct tipping points in parasite population growth [16].

- Larval death rates showed similarly nonlinear effects, with survival times ranging from ~3 days to ~35 days dramatically altering transmission potential.

- These nonlinear responses persisted even when models incorporated additional realistic processes present in livestock systems, suggesting robust underlying mechanisms.

Methodological Approaches

Experimental Protocols for Microclimatic Manipulation

This field experiment demonstrates how to directly test temperature effects on parasite abundance:

Experimental Setup:

- Select paired nest boxes across a fragmentation gradient (edge vs. interior habitats)

- Install heating mats underneath nest material in treatment boxes

- Use programmable thermostats to maintain consistent temperature differentials

- Monitor temperature and humidity using data loggers (e.g., iButton sensors)

Implementation Parameters:

- Apply heating during critical parasite development periods (e.g., nestling days 3-13 for avian systems)

- Maintain temperature increase of 1.5-2.5°C above ambient in treatment group

- Record parallel humidity changes resulting from temperature manipulation

Parasite Assessment:

- Quantify parasite loads using standardized methods (e.g., flea larvae counts from nest material, blowfly pupae collection)

- Measure host health parameters (body mass, wing length) as fitness correlates

- Collect blood samples for hemoparasite screening (e.g., Haemoproteus/Plasmodium)

Statistical Analysis:

- Use generalized linear mixed models to account for nested design

- Include temperature, humidity, habitat type (edge/interior), and their interactions as fixed effects

- Control for host density, nest timing, and other potential confounders

For systems where direct manipulation is impractical, mechanistic models can explore microclimatic effects:

Model Structure:

- Implement stochastic, discrete state-space event-based Markov processes using the Gillespie algorithm

- Track four key state variables: free-living pre-infective larvae, free-living infective larvae, adult parasites in host, and host immunity level

- Incorporate temperature-dependent parameters for larval development and mortality

Parameterization:

- Derive temperature-development relationships from laboratory studies

- Incorporate observed microclimatic differences between edge and interior habitats

- Use sensitivity analysis to identify critical parameters driving system behavior

Simulation Approach:

- Run multiple realizations (≥10) to account for stochasticity

- Systematically vary temperature-sensitive parameters across biologically realistic ranges

- Analyze both peak parasite intensity and cumulative exposure metrics

Visualization of Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental approach for studying edge effects on parasite dynamics:

Experimental Workflow for Studying Edge Effects

Research Tools and Reagents

Table 3: Essential research reagents and equipment for edge effect studies

| Category | Specific Tools | Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microclimate Monitoring | Temperature/Humidity loggers (e.g., iButtons) | Quantifying edge-interior gradients | Deployment duration; weather protection; calibration |

| Parasite Assessment | Microscopy equipment; DNA extraction kits; PCR reagents | Parasite identification and quantification | Sample preservation; taxonomic expertise; molecular primer specificity |

| Field Manipulation | Heating elements; shade structures; irrigation systems | Experimental microclimate alteration | Power requirements; naturalness of manipulation; collateral effects |

| Host Monitoring | Tracking devices; camera traps; nest boxes | Host movement and behavior at edges | Ethical considerations; data storage; battery life |

| Statistical Analysis | R packages (lme4, glmmTMB); Bayesian tools | Modeling nonlinear responses and thresholds | Appropriate random effects; zero-inflation; model convergence |

Implications for Disease Control and Future Research

The documented effects of edge-induced microclimatic changes on free-living parasite stages have significant implications for disease control in fragmented landscapes. Control programs must account for spatial heterogeneity in transmission risk, as edge habitats may function as localized hotspots for parasite persistence and transmission [17] [18]. This spatial patterning suggests that targeted interventions in edge zones could disproportionately reduce overall transmission.

Future research should prioritize:

- Multi-scale studies that simultaneously monitor microclimatic variables, parasite dynamics, and host movements across fragmentation gradients

- Experimental manipulations that directly test causality in natural systems

- Integrated modeling approaches that incorporate both ecological and evolutionary responses to changing conditions

- Long-term monitoring to capture transient dynamics and tipping point behavior

Understanding how edge effects alter the survival and development of free-living parasite stages will enhance our ability to predict disease risks in rapidly changing landscapes and develop more effective, spatially explicit control strategies for parasitic diseases of clinical, veterinary, and conservation concern.

Modeling Frameworks and Analytical Tools for Predicting Parasite Responses to Landscape Change

Individual-Based Simulation Models for Host-Parasite Coevolution

Individual-based models (IBMs) represent a powerful computational approach for studying host-parasite coevolution by simulating populations as collections of discrete individuals, each with unique traits and behaviors. Unlike traditional deterministic models that treat populations as homogeneous continuous entities, IBMs track individuals throughout their life cycles, capturing stochastic events, genetic variation, and local interactions that drive evolutionary dynamics [21]. This modeling paradigm has gained significant traction in theoretical ecology and evolutionary biology due to its ability to incorporate complex biological realism and emergent population-level phenomena from individual-level processes [22]. In the specific context of host-parasite systems, IBMs enable researchers to simulate coevolutionary arms races where reciprocal adaptations between hosts and parasites unfold across generations, influenced by factors such as mutation, selection pressure, and demographic stochasticity [23].

The application of IBMs to host-parasite systems provides unique insights into processes that are difficult to capture using traditional differential equation approaches. These include the maintenance of genetic diversity, the emergence of specialized strategies, and the impact of spatial structure on coevolutionary dynamics [21]. When framed within habitat fragmentation research, IBMs become particularly valuable for investigating how anthropogenic landscape changes disrupt delicate coevolutionary balances. Habitat loss and fragmentation can alter interaction frequencies, modify selection pressures, and create non-uniform evolutionary trajectories across populations, potentially leading to extinction cascades [1]. By simulating how individuals navigate and interact within fragmented landscapes, IBMs can predict how habitat fragmentation might destabilize long-standing host-parasite relationships with consequential effects on biodiversity and ecosystem functioning.

Theoretical Foundations and Modeling Frameworks

Core Mathematical Framework

Individual-based models for host-parasite systems are fundamentally rooted in spatiotemporal point processes where individuals are created, destroyed, and interact at rates that depend on their traits and spatial positions [22]. A unified mathematical framework classifies participants in demographic processes into three types: (1) reactants (individuals destroyed by a process), (2) products (individuals created by a process), and (3) catalysts (individuals that affect process rates but remain unchanged) [22]. This formulation can describe processes with arbitrary complexity, including multiple entity types and interactions with environmental factors.

The dynamics of such systems are described by moment equations representing mean population density (first-order moment) and spatial covariance between individuals (second-order moment). For systems where interactions occur over spatial scales of order (1/\epsilon), the population density and spatial covariance can be expressed as expansions:

[ \begin{aligned} \text{density} &= q + \epsilon^{d}p + o(\epsilon^{d}) \ \text{spatial covariance} &= \epsilon^{d}g(\epsilon x) + o(\epsilon^{d}) \end{aligned} ]

where (q) represents the mean-field density, (p) is the correction due to spatial stochasticity, (g) describes spatial patterns, and (d) is the spatial dimension [22]. This perturbation approach provides a mathematically rigorous connection between individual-based stochastic models and classical mean-field approximations.

Comparison of Modeling Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of Individual-Based and Deterministic Modeling Approaches for Host-Parasite Systems

| Feature | Individual-Based Models | Deterministic Models |

|---|---|---|

| Population representation | Discrete individuals | Continuous densities |

| Stochasticity | Incorporated explicitly (demographic and environmental) | Typically omitted or added as noise |

| Spatial structure | Explicitly represented | Often mean-field or patch-based |

| Genetic diversity | Tracked at individual level | Averaged across populations |

| Computational demand | High | Low to moderate |

| Analytical tractability | Low; primarily simulation-based | High; analytical solutions possible |

| Emergent patterns | Arise from individual interactions | Defined by model equations |

The choice between IBM and deterministic approaches involves trade-offs between biological realism and mathematical tractability. Deterministic models, such as those pioneered by Anderson and May, provide valuable analytical insights into basic reproduction ratios (Râ‚€), stability conditions, and host regulation mechanisms [21]. However, they inevitably simplify or omit important factors such as demographic stochasticity, finite population effects, and individual heterogeneity. IBMs incorporate these factors naturally but at the cost of increased computational requirements and reduced analytical transparency [21]. A promising approach combines both methodologies, using deterministic models to identify general principles and IBMs to explore deviations from these principles in realistic scenarios with small populations, strong stochasticity, or complex spatial structure.

IBM Implementation for Host-Parasite Coevolution

Model Parameterization and Initialization

Implementing an IBM for host-parasite coevolution requires careful parameterization of both host and parasite populations. For cuckoo-host brood parasitism systems, cuckoo parameters include lifespan, egg production capacity, number of host species targeted, initial population size, and probabilities associated with laying eggs, deceiving hosts (through egg color and shape mimicry), and successful fertilization [1]. Host parameters similarly include lifespan, egg production, parasite species numbers, initial and maximum population sizes, and probabilities related to antiparasitism behaviors, parasite detection, fertilization, and chick rearing [1].

To incorporate natural biological variability, four types of stochastic processes are typically employed: (1) categorical variables (e.g., host species) sampled from uniform distributions; (2) probabilistic parameters (e.g., parasitism success rates) following truncated normal distributions; (3) long-tailed discrete variables (e.g., lifespan) modeled using truncated Weibull distributions; and (4) other discrete variables (e.g., egg number) following truncated Poisson distributions [1]. This multi-layered stochastic initialization ensures that models capture essential biological variation while maintaining computational feasibility.

Core Processes and Simulation Workflow

Table 2: Key Processes in Host-Parasite Individual-Based Models

| Process | Mathematical Representation | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Host reproduction | (H \xrightarrow{b_h} H + H) | Host birth at rate (b_h) |

| Parasite reproduction | (P \xrightarrow{b_p} P + P) | Parasite birth at rate (b_p) |

| Infection | (H + P \xrightarrow{k} P + P) | Parasite transmission with rate (k) |

| Host death | (H \xrightarrow{d_h} \emptyset) | Natural host mortality |

| Parasite death | (P \xrightarrow{d_p} \emptyset) | Natural parasite mortality |

| Coevolutionary mutation | (H \xrightarrow{\mu_h} H') | Host trait mutation |

| (P \xrightarrow{\mu_p} P') | Parasite trait mutation |

The simulation workflow for host-parasite IBMs typically follows these sequential processes:

- Population initialization: Creating initial host and parasite populations with defined age structures, spatial distributions, and genetic compositions.

- Mating and reproduction: Implementing species-specific reproductive strategies (e.g., monogamous for hosts, polygamous for parasites) with stochastic inheritance of traits.

- Interaction events: Simulating host-parasite encounters, infection attempts, and defensive responses.

- Selection and mortality: Applying fitness consequences based on interaction outcomes.

- Trait evolution: Introducing new genetic variants through mutation and recombination.

- Demographic updates: Tracking population sizes, age structures, and spatial distributions.

This cycle repeats for each generation or time step, allowing researchers to observe long-term coevolutionary dynamics emerging from individual-level interactions [1].

Figure 1: Core simulation workflow for host-parasite individual-based models, showing the sequential processes that drive coevolutionary dynamics.

Incorporating Habitat Fragmentation Effects

Modeling Habitat Loss and Fragmentation

Habitat loss and fragmentation (HLF) can be incorporated into host-parasite IBMs through several complementary approaches. The most direct method modifies the spatial landscape by explicitly representing suitable and unsuitable habitat patches, with fragmentation controlling patch size, distribution, and connectivity [1]. Alternatively, HLF effects can be implemented implicitly by modifying encounter rates between hosts and parasites based on habitat availability, effectively reducing interaction probabilities as fragmentation increases.

In cuckoo-host systems, severe HLF has been shown to significantly increase extinction risks for parasitic species compared to moderate fragmentation [1]. This occurs because fragmentation narrows the range of host rejection rates that allow parasite populations to persist, disrupting the coevolutionary equilibrium. Specifically, HLF affects the proportion of suitable habitat available for interactions, which in turn alters the rejection rate values that maintain the coevolutionary arms race. If traditional rejection rates become maladaptive due to HLF-altered habitat proportions, either new rejection rates must evolve through natural selection or one or both species face extinction [1].

Impact on Coevolutionary Dynamics

Habitat fragmentation alters host-parasite coevolution through multiple interconnected pathways:

- Restricted movement and gene flow: Reduced connectivity limits dispersal and genetic exchange, leading to increased local adaptation and potential evolutionary divergence.

- Modified encounter rates: Fragmentation changes the frequency and distribution of host-parasite interactions, altering selection pressures.

- Demographic stochasticity: Smaller population sizes in fragmented habitats increase extinction risks due to random demographic fluctuations.

- Evolutionary trap formation: Previously adaptive traits may become maladaptive in fragmented landscapes, creating evolutionary traps.

In brood parasite systems, these effects manifest as constraints on parasitic birds' ability to adjust laying behaviors and locate suitable host nests. Cuckoos may respond by expanding their host range or foregoing adaptations to environmental change, potentially destabilizing long-established coevolutionary relationships [1].

Figure 2: Pathways through which habitat loss and fragmentation affect host-parasite coevolution, showing how initial impacts lead to demographic, evolutionary, and ecological consequences.

Parameter Estimation and Model Calibration

Approximate Bayesian Computation Methods

Parameterizing complex IBMs presents significant challenges due to the high dimensionality of parameter spaces and frequently intractable likelihood functions. Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC) provides a powerful likelihood-free estimation framework that has been successfully applied to host-parasite systems [24] [25]. ABC methods approximate posterior parameter distributions by comparing summary statistics between simulated and observed data, accepting parameter values that produce simulations sufficiently close to empirical observations.

Recent methodological advances include modified sequential-type ABC algorithms that combine sequential Monte Carlo with sequential importance sampling to improve computational efficiency [24] [25]. These approaches iteratively refine parameter estimates through multiple generations of simulations, progressively tightening acceptance criteria to focus on increasingly plausible parameter regions. For post-processing, penalized local-linear regression methods with L1 and L2 regularization address multicollinearity issues that arise when working with high-dimensional summary statistics [25].

Application to Gyrodactylus-Fish Systems

In gyrodactylid-fish systems, ABC methods have enabled estimation of previously inaccessible biological parameters, including:

- Gyrodactylus birth rates for young and old parasites

- Species-specific death rates in the presence and absence of immune responses

- Host-specific immune response rates

- Species-specific parasite movement rates

- Effective parasite population carrying capacity per fish host [25]

This parameter estimation framework allows researchers to address fundamental biological questions about host-parasite systems, such as whether birth and death rates differ significantly across parasite strains, whether immune responses depend on host sex and stock, and whether microhabitat preferences are driven by parasite movement rates [25].

Experimental Protocols and Research Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Host-Parasite Coevolution Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Stochastic simulation software | Implementing individual-based models | Custom C/C++ code, NetLogo, R |

| Approximate Bayesian Computation tools | Parameter estimation and model calibration | ABC-SMC algorithms, DIY-ABC software |

| Spatial data processors | Handling landscape and fragmentation data | GIS tools, spatial statistics packages |

| Genetic algorithm frameworks | Optimizing model structures and parameters | GA libraries in Python, R, MATLAB |

| High-performance computing resources | Managing computational demands of stochastic simulations | Cluster computing, cloud computing services |

| Empirical validation datasets | Parameterizing and validating models | Long-term field studies, experimental coevolution |

| rac-Vofopitant-d3 | rac-Vofopitant-d3, MF:C21H23F3N6O, MW:435.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Macedonoside A | Macedonoside A, CAS:256441-31-3, MF:C42H62O17, MW:838.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Detailed Methodological Protocol

Implementing an IBM for host-parasite coevolution with habitat fragmentation involves these critical steps:

System Definition and Conceptual Model Development

- Identify focal host and parasite species and their key interactions

- Define relevant spatial and temporal scales

- Specify individual-level traits subject to evolutionary change

- Formalize habitat fragmentation metrics and representations

Model Parameterization and Initialization

- Initialize host and parasite populations with realistic size and structure

- Set life history parameters (lifespan, reproductive rates, carrying capacity)

- Define interaction parameters (transmission rates, virulence, defense mechanisms)

- Specify landscape structure and fragmentation patterns

Process Implementation

- Code reproduction routines with inheritance and mutation

- Implement host-parasite interaction functions

- Program movement and dispersal algorithms

- Incorporate habitat-dependent survival and reproduction

Simulation Execution and Monitoring

- Run replicate simulations with different random seeds

- Track population dynamics, genetic diversity, and trait distributions

- Monitor extinction events and evolutionary trajectories

- Record spatial patterns and metapopulation dynamics

Model Validation and Analysis

- Compare model outputs with empirical data when available

- Conduct sensitivity analyses on key parameters

- Implement ABC methods for parameter estimation

- Perform statistical analyses on simulation outputs

This protocol emphasizes the integration of habitat fragmentation effects at each modeling stage, from initial conceptualization through final analysis, ensuring that fragmentation influences both ecological and evolutionary processes throughout the simulation.

Future Directions and Research Applications

The expanding application of IBMs to host-parasite coevolution in fragmented landscapes opens several promising research avenues. Methodologically, future work should focus on developing more efficient parameter estimation techniques, particularly for models with high-dimensional parameter spaces [24] [25]. Computational advances will enable larger-scale simulations that incorporate greater biological realism while maintaining analytical tractability through frameworks like the unified reactant-catalyst-product approach [22].

Biologically, critical research questions remain regarding how habitat fragmentation alters coevolutionary rates and trajectories across different host-parasite systems. The differential impact of fragmentation on specialists versus generalists, the role of evolutionary rescue in preventing extinctions, and the interaction between climate change and fragmentation effects represent particularly urgent research priorities [1]. From a conservation perspective, IBMs offer unprecedented potential for predicting how anthropogenic habitat modification will affect host-parasite relationships, with important implications for disease ecology, biological control, and biodiversity preservation in human-altered landscapes.

By combining individual-based simulation approaches with empirical studies across diverse host-parasite systems, researchers can develop general principles about how habitat fragmentation alters coevolutionary processes, ultimately supporting more effective conservation strategies in an increasingly fragmented world.

Landscape Graph Theory and Connectivity Analysis Using Graphab

Landscape graph theory provides a robust framework for modeling and analyzing habitat connectivity, a cornerstone of modern landscape ecology and conservation biology. This approach conceptualizes a landscape as a network, or graph, where habitat patches are represented as nodes and the potential movement paths for organisms between these patches are represented as links [26]. The power of this abstraction lies in its ability to translate complex spatial patterns into a mathematical structure that can be analyzed using graph theory, revealing the underlying connectivity that governs ecological processes such as dispersal, gene flow, and metapopulation dynamics [27] [26].

The connectivity of habitat networks is not merely a static landscape property but is integral to fundamental ecological processes. As identified by Dunning et al. (1992) and later connected to movement by Taylor et al. (1993), connectivity enables three key landscape-scale processes [26]:

- Source-sink effects, where populations persist in low-quality (sink) patches due to immigration from high-quality (source) patches.

- Landscape supplementation, where individuals access supplementary resources distributed across different patches.

- Landscape complementation, where a species requires different resource types from distinct habitat patches to complete its life cycle.

Originally, many graph-based models represented nodes as a single habitat type. However, recent theoretical and software advancements, particularly in Graphab, now support multiple habitat graphs [26]. This allows for a more realistic representation of ecological requirements by distinguishing between different types of habitat patches (e.g., breeding vs. foraging habitats) and the different types of movement connecting them, thereby more accurately modeling how connectivity brings forth complex ecological processes.

Graphab: An Integrated Software Platform

Graphab is an open-source software application specifically designed for the modeling and analysis of ecological networks using landscape graph theory [27]. It serves as an integrated toolset that bridges the gap between theoretical connectivity models and applied conservation and land-planning needs.

Core Functionalities and Workflow

Graphab standardizes the process of building and analyzing landscape graphs through four main steps, as shown in the workflow below.

Workflow: Graphab's core modeling steps.

Graphab is also characterized by its interoperability, offering connections with other widely used platforms in ecology and geospatial analysis, such as QGIS and R [27]. This allows users to leverage Graphab's specialized graph modeling capabilities within broader, customized analytical workflows.

Advanced Modeling: Multiple Habitat Graphs

A significant advancement in Graphab is the move from single-habitat to multiple habitat graphs [26]. This feature, central to Graphab 3.0, allows different types of nodes to represent different habitat types or qualities, and different types of links to represent different movement purposes (e.g., dispersal, foraging, seasonal migration).

The diagram below illustrates how a multiple habitat graph models the three key landscape ecological processes.

Graph: Modeling landscape processes with multiple habitats.

This multi-habitat approach is crucial for accurately modeling real-world scenarios, such as amphibians that reproduce in wetlands but overwinter in forests, or natural enemies of crop pests that reproduce in semi-natural habitats [26].

Habitat Fragmentation and Parasite Dynamics: A Conceptual and Methodological Framework

Habitat fragmentation can significantly alter host-parasite interactions, but the effects are complex and depend on the life history strategies of both hosts and parasites [28] [5]. Graph theory provides the tools to model the altered connectivity underlying these changes.

Theoretical Underpinnings of Parasite Responses to Fragmentation

The table below synthesizes the primary ways habitat fragmentation impacts parasite dynamics, as evidenced by empirical studies.

Table 1: Effects of habitat fragmentation on parasite dynamics

| Effect Category | Impact on Parasites | Proposed Mechanism | Key Reference Host/Parasite |

|---|---|---|---|

| Host Density & Community | Increased abundance of generalist hosts in fragments; reduced host species richness. | Release from predation/competition favors high-density generalists, altering parasite transmission. | Four-striped mouse (Rhabdomys pumilio) and its ecto-/endoparasites [28]. |

| Parasite Life Cycle Bottleneck | Disruption for parasites with complex (heteroxenous) life cycles. | Loss or reduced density of one required host species in the life cycle. | Nematode (Hedruris wogwogensis) using amphipods and skinks [29]. |

| Abiotic Edge Effects | Reduced abundance of soil-transmitted parasites and their free-living stages. | Changed microclimates (e.g., soil temp, humidity) at edges are unfavorable. | Gastrointestinal parasites of mouse lemurs and rodents in Malagasy dry forest [5]. |

| Parasite Life History | Variable responses based on parasite traits. | Host-specificity, level of host association (permanent vs. temporary), and transmission mode determine sensitivity. | Comparative responses of lice, ticks, fleas, and nematodes [28]. |

Integrating Parasite Dynamics into Landscape Graphs

To integrate these dynamics into a Graphab-based analysis, the multiple habitat graph framework can be extended. A parasite's ecological network can be modeled as a multi-layer graph, where one layer represents the host's habitat network and other layers represent the habitat networks of other required host species or the abiotic environment needed for free-living stages.

The following diagram outlines a conceptual workflow for such an analysis.

Workflow: Modeling parasite life cycle connectivity.

For example, the nematode Hedruris wogwogensis relies on an amphipod intermediate host and a skink definitive host [29]. In a Graphab model, the connectivity of the forest patches for the skink and the moist habitat for the amphipods would be modeled as separate but potentially interacting networks. The overall connectivity for the parasite would be a function of the weakest link in this composite network, explaining its long-term failure to recover in fragmented habitats where host populations fell out of sync [29].

Experimental Protocols for Integrating Field Parasitology and Graph Analysis

Linking field-collected parasitological data to graph-based connectivity metrics requires a structured methodological approach. The following protocol provides a detailed guide for such an integrated study.

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for integrated connectivity-parasitology studies

| Category | Item / Solution | Specific Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Field Sampling & Host Data | Live traps (e.g., Sherman traps) | Safe capture of small mammal hosts for parasitological examination. |

| Standardized morphometric data collection tools (calipers, scales) | Assessment of host body condition as a proxy for health. | |

| Geographic Information System (GIS) Software (e.g., QGIS) | Mapping host capture locations, delineating habitat patches, and creating landscape resistance models. | |

| Parasite Recovery & Identification | Coproscopical examination kit (microscope, flotation solution) | Identification and quantification of endoparasites (e.g., helminth eggs) from host fecal samples. |

| Ectoparasite collection kits (forceps, vials with 70% ethanol) | Collection and preservation of ectoparasites (e.g., ticks, fleas, mites) from host pelage. | |

| Taxonomic keys and molecular barcoding tools | Accurate identification of parasite morphotypes and species. | |

| Connectivity Modeling | Graphab Software (v3.0 or later) | Core platform for constructing and analyzing landscape graphs, including multiple habitat types. |

| Land cover classification maps | Primary spatial data for defining habitat patches and the resistance matrix. |

Detailed Integrated Methodology

Study Design and Site Selection:

- Select study localities in a paired design, including sites in both extensive, continuous natural vegetation and remnant fragments isolated by agriculture or other human land use [28]. Pairs should be matched for factors like altitude and underlying vegetation type to control for confounding variables.

- Georeference all sampling locations with GPS.

Field Data Collection on Hosts and Parasites:

- Conduct standardized trapping sessions for target host species across all sites.

- For each captured individual, record species, sex, weight, and body condition. Take a fecal sample for endoparasite analysis.

- Perform a standardized ectoparasite census. Ectoparasites can be collected by combing the host's fur over a white tray or by storing the host in a clean paper bag to collect falling parasites [28].

- All parasites should be identified to the lowest possible taxonomic level (morphotype or species), and abundance should be recorded.

Landscape Graph Construction in Graphab:

- Use a land cover map to define habitat patches (nodes). In a multiple habitat graph, different node types can be assigned based on habitat quality (e.g., source vs. sink) or type (e.g., breeding vs. foraging habitat) [26].

- Define a species-specific resistance matrix based on land cover types to model movement costs.

- Use Graphab to generate a link set connecting habitat patches, typically using a maximum cost distance threshold or by computing least-cost paths.

- Calculate key connectivity metrics for each habitat patch. Crucial metrics for parasitological studies include:

- Probability of Connectivity (PC): Measures the overall reachability of a patch within the network, which can influence parasite dispersal.

- Degree/Float: The number of connections a patch has, which may correlate with exposure to parasites from multiple sources.

- Metric specific to multiple habitat graphs: For example, the connectivity from a putative "source" habitat to a "sink" habitat.

Data Integration and Statistical Analysis:

- Construct a dataset where each record is a host individual, with associated parasite data (e.g., infestation status, parasite species richness) and the graph metrics of the patch where it was captured.