Geometric Morphometrics in Parasitology: A Cutting-Edge Framework for Species Identification, Biomedical Research, and Drug Development

Geometric morphometrics (GM) has emerged as a powerful quantitative tool for analyzing the shape of parasite structures, offering significant advantages over traditional descriptive methods.

Geometric Morphometrics in Parasitology: A Cutting-Edge Framework for Species Identification, Biomedical Research, and Drug Development

Abstract

Geometric morphometrics (GM) has emerged as a powerful quantitative tool for analyzing the shape of parasite structures, offering significant advantages over traditional descriptive methods. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring GM's foundational principles in understanding parasite adaptation and host-specificity. It details state-of-the-art methodological workflows, from landmark digitization to statistical analysis, and presents its application in diagnosing medically significant parasites with 94.0-100.0% accuracy. The content also addresses critical troubleshooting for data optimization and validates GM against molecular and conventional techniques, synthesizing its profound implications for advancing parasite taxonomy, evolutionary ecology, and the development of targeted therapeutic strategies.

Beyond the Microscope: Unlocking Parasite Ecology and Evolution Through Shape Analysis

Geometric morphometrics (GM) is a powerful statistical methodology for quantifying and analyzing biological shape. Unlike traditional morphometrics, which relies on linear measurements and ratios, GM captures the geometry of morphological structures using Cartesian coordinates of anatomical points, known as landmarks [1]. This approach preserves the spatial relationships throughout analysis, allowing researchers to visualize shape changes and separate shape from size variation [2]. In parasite research, GM provides an essential toolkit for quantifying subtle morphological variations in parasite structures that may correlate with pathogenicity, drug resistance, or host specificity. These quantitative morphological analyses are particularly valuable in antimalarial drug development, where understanding parasite-host dynamics is crucial for evaluating treatment efficacy [3].

The application of GM to microscopic organisms, including parasites, requires specialized protocols for data collection and analysis. Recent methodological advances now enable researchers to perform precise quantification of even microscopic structures, making GM an invaluable technique in evolutionary developmental biology and parasitology [4]. For drug development professionals, this offers opportunities to identify morphological biomarkers associated with treatment response and understand how parasitic structures adapt under therapeutic pressure.

Fundamental Principles and Terminology

Landmarks and Their Types

Landmarks are discrete, homologous points that can be precisely located across all specimens in a study. They form the foundation of geometric morphometric analysis and are typically categorized into three types:

- Type I landmarks are defined by local biological features, such as the intersection of two structures or a point of maximum curvature. In parasite morphology, this might include the tip of a feeding structure or the junction of different body segments [4].

- Type II landmarks represent points of maximum curvature or other local geometric features, such as the apex of a tooth or the deepest point of a notch in parasitic structures.

- Type III landmarks are defined by extremal points, such as the furthest point of a structure, which may be used to capture overall dimensions when more specific homologous points are unavailable.

Semilandmarks

For curved surfaces or outlines where true homologous points are scarce, semilandmarks provide a solution by allowing the quantification of continuous contours [1]. These points are placed along curves and surfaces and are subsequently slid during analysis to minimize bending energy, thus capturing the geometry of structures without discrete landmarks.

Experimental Protocols for Parasite Morphometrics

Sample Preparation and Imaging

Proper sample preparation is critical for obtaining high-quality morphometric data from parasite specimens:

- Fixation and Mounting: Fix parasites in appropriate solutions to preserve morphology without distortion. For microscopic nematodes and similar parasites, this may involve heat-killing followed by formalin or ethanol fixation [4].

- Microscopy: Use compound or dissection microscopes with calibrated digital cameras. For consistent results, maintain standardized magnification, lighting, and orientation across all specimens.

- Image Acquisition: Capture digital images at minimum 400 DPI resolution to ensure sufficient detail for landmark placement [5]. Include a scale bar in all images for subsequent size calibration.

- Image Processing: Convert images to appropriate formats (JPEG or TIFF) and adjust contrast if necessary, while avoiding manipulations that alter morphological relationships.

Landmark Digitization Protocol

The process of landmark digitization follows a standardized workflow:

Step-by-Step Implementation:

Software Setup: Open specialized morphometrics software such as TPSdig or ImageJ with appropriate plugins [5]. For ImageJ, select 'Analyze > Set Measurements' and check the 'Display label' checkbox.

Landmark Configuration: Access the 'Point selection' tool in multi-point mode to begin placing landmarks on predetermined positions of parasite structures.

Coordinate Recording: After placing all landmarks on a specimen, select 'Analyze > Measure' to generate a results window containing x,y coordinates for each landmark.

Data Management: Copy and paste coordinate data into a master spreadsheet with columns for 'order,' 'label,' 'x,' and 'y' [5]. The spreadsheet should ultimately be converted to tab-delimited text format for analysis in statistical software.

Quality Control: Plot landmark coordinates using visualization tools to identify placement errors. Re-landmark any specimens with obvious inaccuracies before proceeding to analysis.

Generalized Procrustes Analysis (GPA)

GPA is the core statistical procedure in geometric morphometrics that removes non-shape variation through a three-step process:

- Centering: Translate all configurations so they share a common centroid at coordinates (0,0).

- Scaling: Scale all configurations to unit centroid size.

- Rotation: Rotate configurations to minimize the sum of squared distances between corresponding landmarks.

This superimposition process allows direct comparison of shape by eliminating differences due to position, orientation, and scale [5]. The resulting Procrustes coordinates represent pure shape variables for subsequent multivariate analysis.

Outline Analysis with Elliptical Fourier Descriptors

For parasite structures lacking discrete landmarks, Elliptical Fourier Analysis (EFA) provides an alternative approach:

- Outline Digitization: Convert parasite outlines to chain codes by plotting a sequence of coordinates along the contour.

- Fourier Transformation: Decompose outlines into a sum of trigonometric functions (harmonics) using Fourier transformation.

- Harmonic Selection: Determine the optimal number of harmonics needed to accurately capture outline shape while filtering out noise.

- Normalization: Standardize Fourier coefficients to ensure invariance to size, rotation, and starting point.

EFA is particularly valuable for analyzing continuously curved structures in parasites, such as eggs, cysts, or body contours [5].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Statistical Analysis of Shape Data

Following GPA, researchers can apply various multivariate statistical techniques to explore shape variation:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Identifies major axes of shape variation within the dataset, allowing reduction of complex multidimensional shape data into interpretable components.

- Canonical Variate Analysis (CVA): Maximizes separation between pre-defined groups, useful for discriminating among parasite strains or treatment groups.

- Procrustes ANOVA: Tests for significant shape differences between groups while accounting for the covariance structure of landmark data.

- Regression Analysis: Examines relationships between shape variables and continuous predictors such as drug concentration or time.

Visualization of Results

Effective visualization is essential for interpreting morphometric results:

- Deformation Grids: Visualize shape changes using transformation grids that show how the landmark configuration deforms along morphological gradients [2].

- Principal Component Plots: Display specimen distribution along major axes of shape variation.

- Mean Shape Comparisons: Superimpose and compare mean shapes of different groups to highlight consistent morphological differences.

- Vector Displacement Diagrams: Illustrate the direction and magnitude of landmark movement between groups.

Application to Parasite Research and Drug Development

Quantitative Analysis of Parasite Structures

Geometric morphometrics enables precise quantification of parasite morphological features relevant to drug development:

Table 1: Morphometric Parameters in Antimalarial Drug Efficacy Studies

| Parasite Structure | Morphometric Parameter | Relationship to Drug Efficacy | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asexual Blood Stages | Shape circularity | Decreased circularity associated with drug-induced stress | Outline analysis |

| Food Vacuoles | Size and shape | Morphological changes indicate hemoglobin digestion disruption | Landmark-based GM |

| Apicoplast | Aspect ratio | Elongation correlates with metabolic inhibition | Elliptical Fourier descriptors |

| Cell Membrane | Surface contour complexity | Increased irregularity precedes cell lysis | Semilandmark analysis |

Integration with Drug Development Pipeline

GM can be incorporated at multiple stages of antimalarial drug development:

- Target Identification: Correlate structural phenotypes with genomic data to identify potential drug targets.

- Lead Optimization: Use morphological changes as quantitative endpoints for structure-activity relationship studies.

- Mechanism of Action Studies: Characterize specific morphological signatures associated with different drug classes.

- Resistance Monitoring: Detect subtle morphological adaptations in resistant parasite strains.

Table 2: Parasite Clearance Rates in Different Experimental Systems

| Experimental System | Maximum Parasite Clearance Rate (1/h) | Drug Tested | Key Morphometric Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| P. berghei in NMRI mice | 0.2 | MMV048, OZ439 | Quantification of structural damage in early blood stages |

| P. falciparum in SCID mice | 0.05 | MMV048, OZ439 | Monitoring morphological recovery in humanized model |

| P. falciparum in human volunteers | 0.12-0.18 | MMV048, OZ439 | Correlation of shape changes with parasite clearance kinetics |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Parasite Morphometrics

| Reagent/Equipment | Specification | Function in Protocol | Example Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixation Solution | 4% formaldehyde, 2.5% glutaraldehyde | Preserves parasite morphology without distortion | Ethanol, paraformaldehyde |

| Mounting Medium | Glycerol-based, refractive index ~1.4 | Standardizes optical properties for imaging | Commercial mounting media |

| Staining Solutions | Giemsa, Acridine Orange | Enhances contrast of specific structures | Fluorescent tags, H&E |

| Digital Microscope | Minimum 400 DPI resolution | Captures high-quality images for analysis | Compound microscope with camera |

| ImageJ Software | Version 1.52 or higher | Open-source platform for image analysis and landmarking | TPSdig, MorphoJ |

| R Statistical Package | with 'geomorph' and 'Morpho' libraries | Statistical shape analysis and visualization | PAST, IMP suite |

Advanced Analytical Framework

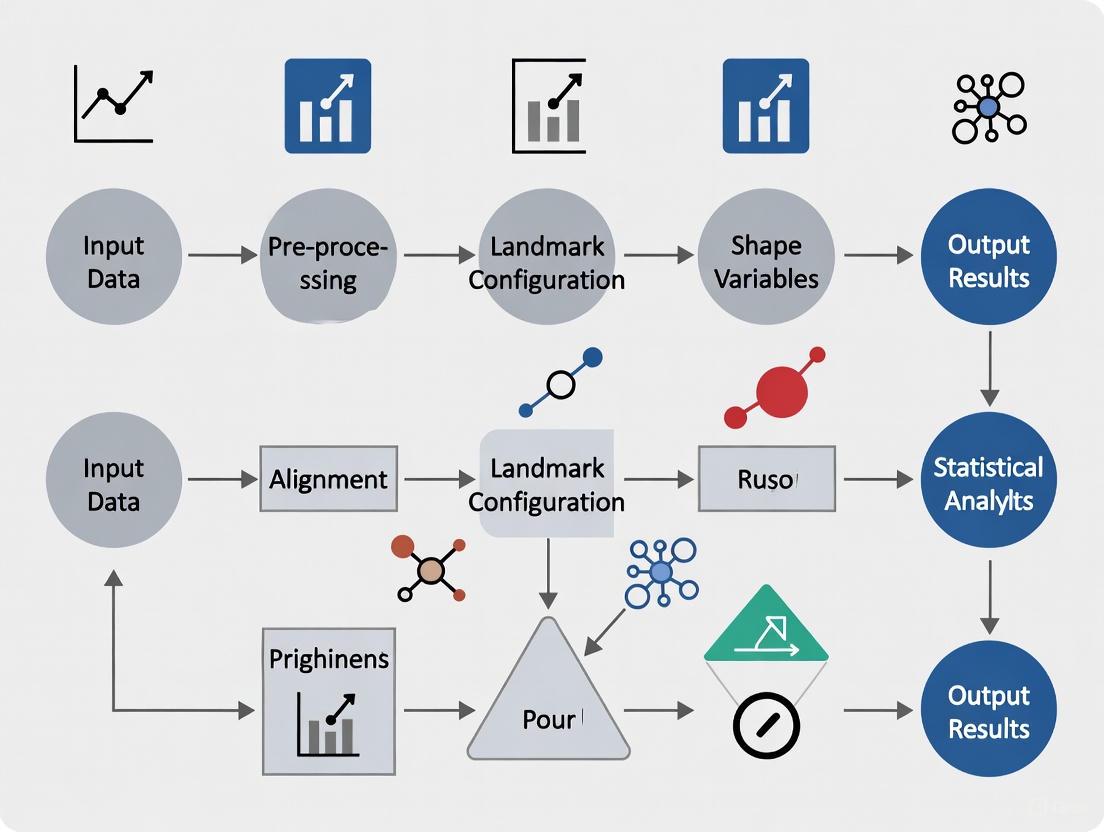

The following diagram illustrates the integrated analytical workflow for applying geometric morphometrics in parasite research and drug development:

Geometric morphometrics provides parasite researchers and drug development professionals with a rigorous quantitative framework for analyzing morphological structures. By implementing standardized protocols for landmark digitization, Procrustes superimposition, and multivariate statistical analysis, researchers can extract meaningful biological insights from subtle shape variations. The integration of these approaches into antimalarial drug development pipelines offers promising opportunities to identify morphological biomarkers of drug efficacy and understand parasite responses to therapeutic intervention at the structural level.

Application Notes

Functional Morphology of Attachment in Monogeneans

In Monogenean parasites, the haptor (a specialized posterior attachment organ) is a complex structure equipped with hardened sclerites and associated musculature that enables firm adhesion to host tissues. In Tetraonchus monenteron, a parasite of pike, the haptoral armature consists of ventral and dorsal pairs of anchors, a ventral bar, eight pairs of marginal hooks, and at least three pairs of accessory sclerites [6] [7]. These sclerites are operated by a sophisticated system of 14 muscles [6]. The dorsal anchors achieve a gaffing action primarily through the coordinated effort of extrinsic muscles and a transverse muscle that clamps them against the body wall [6] [7]. Conversely, the ventral anchors are stabilized in position by the transverse muscle and additional muscles inserting on the ventral bar and haptoral wall [6] [7]. This intricate musculoskeletal arrangement is a key taxonomic character and highlights the haptor's adaptation for securing the parasite to a dynamic, mobile host.

Shape Variation in Cymothoid Isopod Attachment Structures

In Cymothoid isopods, the shape of the attachment claws, known as dactyli, directly reflects their parasitic strategy and the functional demands of their specific microhabitat on the host fish [8]. Externally-attaching species (e.g., on the skin) are subject to greater hydrodynamic forces and possess dactyli that are relatively longer, thinner, and more needle-like, an adaptation for piercing flesh and resisting detachment [8]. In contrast, internally-attaching species (e.g., within the gill chamber or mouth) use their dactyli more for grasping hard structures like gill rakers; their dactyli are stouter, more recurved, and strengthened for a gripping function [8]. Geometric morphometric analyses confirm that parasite mode is the primary driver of this dactylus shape variation, with mouth-attaching species exhibiting greater shape variability than gill-attachers [8]. This ecomorphological pattern suggests that attachment structure morphology is a critical trait reinforcing host niche specialisation.

Insights from Parasite Community Structure

The study of parasite communities can provide indirect insights into the functional morphology of parasite structures by revealing patterns of host use and infestation. A study on the Cape elephant fish (Callorhinchus capensis) found a uniform parasite community structure across different host populations, indicating a highly interactive shark community with no significant population structure [9]. This suggests that parasites, and by extension their attachment mechanisms, are effectively dispersed across the entire host population. The parasite community was characterized by a low diversity of species, including a cestode (Gyrocotyle plana), two monogeneans (Callorhynchicotyle callorhynchi and Callorhinchicola multitesticulatus), an isopod (Anilocra capensis), and a leech (Branchellion sp.) [9]. The specific sites of attachment on the host (e.g., gills, spiral valve, external body surface) underscore the niche partitioning facilitated by specialized attachment structures [9].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Confocal Microscopy for Sclerite and Musculature Visualization

This protocol details the methodology for visualizing the hard sclerites and associated musculature of parasite attachment organs, as applied to the monogenean Tetraonchus monenteron [6] [7].

1. Sample Preparation and Fixation:

- Collect parasite specimens from the host organism (e.g., gills of pike for T. monenteron).

- Fix specimens in an appropriate fixative (e.g., 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline) for several hours to preserve tissue structure.

2. Phalloidin Staining:

- Permeabilize the fixed specimens using a detergent solution (e.g., 0.1% Triton X-100).

- Incubate the specimens in a solution of phalloidin conjugated to a fluorophore (e.g, Alexa Fluor 488). Phalloidin specifically binds to F-actin, vividly staining the muscular architecture [6].

- Perform several washes in a buffer to remove unbound stain.

3. Confocal Microscopy and Reflection Mode Imaging:

- Mount the stained specimens on microscope slides.

- Use a confocal laser scanning microscope to image the phalloidin-stained musculature.

- Simultaneously, activate the reflection confocal mode to visualize the hardened sclerites (anchors, bars, hooks) based on their light-reflecting properties [6]. This allows for the simultaneous 3D rendering of both soft musculature and hard sclerites.

4. Data Analysis:

Protocol 2: Geometric Morphometric Analysis of Attachment Structures

This protocol outlines an outline-based geometric morphometric (GM) approach to quantify and analyze the shape of parasite attachment structures, as applied to cymothoid isopod dactyli and parasite eggs [10] [8].

1. Image Acquisition:

- Capture high-resolution digital images of the attachment structures (e.g., dactyli, parasite eggs) using a camera mounted on a stereomicroscope. Ensure all specimens are photographed in a consistent orientation [8].

2. Landmarking:

- Import images into specialized morphometric software (e.g., tpsDig2) [8].

- Plot fixed landmarks on biologically homologous points (e.g., joint base, distal tip) [8].

- Place semi-landmarks along curves and outlines between fixed landmarks to capture the overall shape geometry [8]. For example, a study on cymothoid dactyli used 3 fixed landmarks and 39 semi-landmarks to describe the shape [8].

3. Shape Analysis:

4. Statistical Integration:

- Use multivariate statistical tests (e.g., multivariate regression, discriminant analysis) to test hypotheses about the factors influencing shape, such as parasite mode, allometry, or host species [8].

- Compare the Procrustes distances between groups to assess shape disparity [10] [8].

- If data for multiple species is available, perform a Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS) analysis to account for the influence of shared evolutionary history [8].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Quantitative Summary of Haptoral Structures in Tetraonchus monenteron [6] [7]

| Structure Type | Component | Quantity | Key Associated Muscles | Postulated Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anchors | Dorsal Anchor Pair | 2 | Extrinsic muscles (de, le1-3), muscles to body wall (daw1-2) | Gaffing, deep tissue penetration |

| Ventral Anchor Pair | 2 | Transverse muscle (vat), muscles to ventral bar (vav1-3) | Stabilization, clamping | |

| Bars | Ventral Bar | 1 | Connection point for muscles vav1-3 | Structural support, muscle leverage |

| Marginal Hooks | Pairs | 8 | Protractor muscle (mp) | Fine-scale attachment & movement |

| Accessory Sclerites | Brace-shaped (brs) | ≥ 2 | Muscle bundles (brm) | Linking extrinsic muscles to dorsal anchors |

| Flabellate (fs) | ≥ 2 | Muscles from dorsal anchor (daf1-2) | Muscle attachment | |

| Ball-shaped (bas) | ≥ 2 | Not specified | Unknown |

Table 2: Factors Driving Dactylus Shape Variation in Cymothoid Isopods [8]

| Factor | Effect on Dactylus Shape | Statistical Significance | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parasite Mode (External vs. Internal) | Clear shape differences; external = longer, needle-like; internal = stouter, recurved | Primary driver (p < 0.05) | Functional adaptation to microhabitat (hydrodynamics vs. gripping) |

| Allometry (Size) | Significant for anterior (P1) dactyli; not significant for posterior (P7) dactyli | Anterior: SignificantPosterior: Not Significant | Shape changes with growth are more pronounced in the anterior appendage |

| Phylogeny | No clade-specific patterns of association with parasite mode | Not Significant | Parasite mode overrides evolutionary history (convergent evolution) |

Mandatory Visualization

Diagram 1: Geometric Morphometric Workflow

Diagram 2: Haptor Musculoskeletal System

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Morphological Analysis of Parasite Structures

| Research Reagent / Material | Critical Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Phalloidin-Fluorophore Conjugate | Selectively binds to filamentous actin (F-actin) in muscle fibers, enabling high-resolution visualization of the muscular architecture. | Staining the complex arrangement of 14 muscles operating the anchors in Tetraonchus monenteron [6] [7]. |

| Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope | Allows for optical sectioning of tissues to generate 3D reconstructions; reflection mode can visualize hard, light-reflecting sclerites without staining. | Simultaneous imaging of phalloidin-stained musculature and reflective sclerites in a monogenean haptor [6]. |

| Geometric Morphometric Software (e.g., tpsDig2) | Provides tools for digitizing biological landmarks and semi-landmarks on digital images for quantitative shape analysis. | Quantifying shape variation in the dactyli of cymothoid isopods using fixed landmarks and semi-landmarks [8]. |

| Molecular Phylogenetic Tools (PCR, DNA sequencer) | Generates data to reconstruct evolutionary relationships among parasite species, allowing tests of shape evolution independent of phylogeny. | Conducting Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS) regression to account for shared ancestry in shape analysis [8]. |

| TTP607 | TTP607 | Chemical Reagent |

| trans-Anol | trans-Anol, CAS:20649-39-2, MF:C9H10O, MW:134.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The study of host-parasite co-evolution represents a cornerstone of evolutionary biology, providing critical insights into the dynamic interplay between species. Within this field, geometric morphometrics (GMM) has emerged as a powerful quantitative framework for analyzing how parasite attachment structures evolve in response to host-specific selective pressures. By quantifying shape variation using Cartesian coordinates of anatomically homologous landmarks, researchers can test hypotheses about the functional demands of different parasitic strategies and their evolutionary consequences. This protocol details the application of GMM to investigate how variation in parasite attachment structures reflects divergent evolutionary pathways and ecological specializations.

The recurved dactyli of cymothoid isopods and the haptoral anchors of monogenean flatworms serve as exemplary model systems. These structures are not merely taxonomic features but functional interfaces whose morphologies are fine-tuned by evolutionary processes. Research on cymothoid isopods has demonstrated clear morphological differences between externally-attaching and internally-attaching species, with shape variation correlating strongly with parasitic mode rather than shared ancestry [8]. Similarly, studies on Ligophorus cephali anchors have revealed significant phenotypic plasticity, suggesting host-driven plastic responses that facilitate host-switching and rapid speciation [11]. These findings underscore the value of GMM in unraveling the complex relationship between parasite form and function.

Key Concepts and Biological Foundations

Principles of Geometric Morphometrics in Parasitology

Geometric morphometrics differs fundamentally from traditional morphometric approaches by preserving the complete geometric configuration of anatomical structures throughout analysis. This methodology involves:

- Landmark-Based Analysis: Using two-dimensional or three-dimensional coordinates of biologically homologous points to capture shape information

- Procrustes Superimposition: A standardization procedure that removes differences in size, position, and orientation by centering shapes on the same point, scaling them to unit size, and rotating them to minimize least-squares distances between corresponding landmarks [12]

- Shape Space Construction: Creating multidimensional spaces where each point represents a unique shape configuration, allowing for statistical analysis of shape variation

The power of GMM lies in its ability to visualize shape differences directly through deformation grids, vector diagrams, and morphospace plots, providing intuitive representations of complex morphological variation.

Functional Morphology of Parasite Attachment Structures

Parasite attachment organs represent remarkable evolutionary adaptations that balance multiple functional demands:

- Attachment Security: Maintaining firm attachment against host defenses and environmental forces

- Resource Acquisition: Facilitating feeding while minimizing damage to host tissues

- Reproductive Capacity: Allowing for mating and reproduction while attached to the host

In cymothoid isopods, the recurved dactyli (hook-like appendages) on pereopods show distinct morphological specializations based on attachment location. Externally-attaching species, which face greater hydrodynamic forces, tend to have longer, more needle-like dactyli adapted for piercing flesh, while gill- and mouth-attaching species possess stouter, more recurved dactyli optimized for gripping host structures [8]. Similarly, in monogeneans like Ligophorus cephali, the dorsal and ventral anchors of the haptor exhibit different morphological gradients and functional specializations, with the ventral anchors typically responsible for firmer attachment [11].

Table 1: Functional Demands on Parasite Attachment Structures by Microhabitat

| Parasite Group | Attachment Mode | Functional Challenges | Morphological Adaptations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cymothoid Isopods | External (skin) | High hydrodynamic drag; host musculature penetration | Elongated, needle-like dactyli for deep tissue penetration |

| Cymothoid Isopods | Gill chamber | Limited space; delicate branchial tissues | Recurved, stout dactyli for clasping gill rakers |

| Cymothoid Isopods | Mouth cavity | Tongue/palate attachment; feeding interference | Stout, hook-shaped dactyli for anatomical "replacement" |

| Monogeneans (Ligophorus) | Gill filaments | Mucosal surface adherence; host immune response | Complex anchor/bar complexes with differential mobility |

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Geometric Morphometrics of Parasite Structures

| Item/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Specimen Collections | Curated museum collections; field-collected specimens | Source of morphological data; taxonomic verification |

| Imaging Equipment | Nikon DS-Fi1 camera; Nikon SMZ1500 stereoscopic microscope | High-resolution digital image capture for landmark digitization |

| Landmark Digitization Software | tpsDig2; StereoMorph R package | Precise placement of landmarks and semi-landmarks on digital images |

| Geometric Morphometric Analysis Software | MorphoJ; geomorph R package; CoordGen | Procrustes superimposition; statistical shape analysis; visualization |

| Molecular Phylogenetics Tools | PCR amplification; Cytochrome Oxidase I (COI) sequencing | Phylogenetic framework for comparative analyses |

| Statistical Packages | R with specialized packages (vegan, ape) | Multivariate statistical analysis; phylogenetic comparative methods |

Experimental Protocol: Geometric Morphometric Analysis of Parasite Attachment Structures

Specimen Preparation and Imaging

Specimen Sourcing and Curation:

- Obtain parasite specimens from natural infestations or scientific collections

- Ensure proper taxonomic identification using both morphological and molecular characters

- For cymothoid isopods, focus on adult females to minimize sex-based variation [8]

Standardized Imaging Protocol:

- Mount specimens in consistent orientation to minimize projection artifacts

- Use calibrated stereomicroscope with attached digital camera (e.g., Nikon DS-Fi1 on SMZ1500 microscope)

- Capture high-resolution images of specific attachment structures (e.g., P1 and P7 pereopods in isopods; dorsal and ventral anchors in monogeneans)

- Include scale bars in all images for size calibration

- Maintain consistent lighting conditions and magnification across all specimens

Landmark Configuration and Digitization

Landmark Selection Criteria:

- Identify homologous points that can be reliably located across all specimens

- Include Type I landmarks (discrete anatomical junctions), Type II landmarks (maxima of curvature), and Type III landmarks (extremal points)

- For cymothoid dactyli, use a configuration of 3 fixed landmarks and 39 semi-landmarks along two curves [8]

- Ensure the same number and sequence of landmarks for all specimens

Semi-Landmark Placement:

- Define curves between fixed landmarks using mathematical functions

- Place semi-landmarks equidistantly along curves to capture outline geometry

- For sliding semi-landmarks, implement algorithms that minimize bending energy or Procrustes distance [12]

- Use software such as tpsDig2 or StereoMorph for standardized digitization

Data Processing and Shape Analysis

Procrustes Superimposition:

- Implement Generalized Procrustes Analysis (GPA) to align all landmark configurations

- Remove non-shape variation through translation, scaling, and rotation

- Generate Procrustes coordinates representing shape variables for statistical analysis

- Calculate consensus (mean) shape as reference for visualization

Statistical Analysis of Shape Variation:

- Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify major axes of shape variation

- Conduct multivariate regression (e.g., Procrustes ANOVA) to test allometric effects

- Implement discriminant analysis to assess group separability by parasitic mode

- Apply phylogenetic comparative methods (e.g., phylogenetic GLS) to account for evolutionary relationships

Workflow for Geometric Morphometric Analysis of Parasite Structures

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Case Study: Cymothoid Isopod Dactyli

The application of GMM to cymothoid isopod dactyli reveals clear patterns of morphological adaptation:

Table 3: Shape Variation in Cymothoid Isopod Dactyli by Attachment Mode

| Attachment Mode | Anterior Dactyli (P1) Shape | Posterior Dactyli (P7) Shape | Allometric Pattern | Functional Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouth-attachers | High shape variability; stout, recurved | Moderate variability; gripping morphology | Significant allometry | Adaptation to diverse intra-oral attachment sites |

| Gill-attachers | Intermediate shape; curved for raker clasping | Consistently recurved; strengthened | Moderate allometry | Optimization for branchial chamber environment |

| Skin-attachers | Elongated, needle-like; minimal curvature | Slender, piercing morphology | Non-significant allometry | Specialization for deep tissue penetration |

Statistical analysis of 124 individuals across 18 species demonstrated that parasite mode explains a significant proportion of shape variation, with mouth-attaching species showing greater shape variability than gill- or skin-attaching species [8]. Phylogenetic comparative methods confirmed that these patterns reflect ecological specialization rather than shared evolutionary history.

Case Study: Monogenean Haptoral Anchors

Research on Ligophorus cephali haptoral anchors illustrates the value of GMM in detecting phenotypic plasticity:

- Dorsal and ventral anchors show similar gradients of overall shape variation, but dorsal anchors exhibit higher localized changes

- The dorsal anchor/bar complex demonstrates greater mobility than the ventral complex, suggesting functional differentiation

- Ventral anchors show less residual variation, indicating tighter developmental control, possibly due to their role in firm attachment

- High morphological integration between anchors reflects their concerted action during attachment

- The low genetic variation coupled with significant morphological variation suggests host-driven plastic responses rather than genetic differentiation [11]

Evolutionary Framework for Parasite Attachment Structure Morphology

Advanced Applications and Research Implications

Integration with Genomic Approaches

The combination of GMM with genomic methods provides unprecedented insights into co-evolutionary processes:

- Population Genomics: Studies on microsporidian parasites (Hamiltosporidium) of Daphnia magna demonstrate how demographic history and transmission mode shape genomic variation, which can be correlated with morphological changes in attachment structures [13]

- Phylogenetic Comparative Methods: Mapping morphological data onto molecular phylogenies enables discrimination between phylogenetic constraint and adaptive evolution in parasite attachment structures [8]

- Genotype-Phenotype Mapping: Identifying genetic loci associated with specific morphological variants can reveal the genetic architecture underlying attachment organ development

Implications for Drug and Vaccine Development

Understanding the functional morphology of parasite attachment interfaces has practical applications:

- Anti-Adhesion Therapies: Identifying morphological vulnerabilities in attachment mechanisms can inform strategies to disrupt host-parasite interfaces

- Vaccine Target Identification: Highly conserved attachment structures undergoing strong selective pressure may represent promising vaccine targets

- Drug Delivery Optimization: Knowledge of site-specific attachment morphologies can guide targeted delivery of chemotherapeutic agents

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

Common Methodological Challenges

- Landmark Homology: Ensuring true biological homology across diverse taxa requires careful anatomical study and may necessitate the use of semi-landmarks for complex curves

- Measurement Error: Conduct repeated digitization sessions to quantify and account for measurement error, which should be substantially smaller than biological variation of interest [14]

- Size Allometry: While Procrustes superimposition removes size, allometric effects on shape should be explicitly tested using multivariate regression [8]

- Phylogenetic Independence: Implement phylogenetic comparative methods to account for non-independence of related species

Sample Size Considerations

Determining adequate sample size depends on:

- The magnitude of shape differences between groups relative to within-group variation

- The number of landmarks and their capacity to capture biologically relevant shape information

- The complexity of the statistical analyses planned

- As a general guideline, studies of cymothoid isopods have successfully detected morphological differences with 5-10 specimens per species across 18+ species [8]

Geometric morphometrics provides a powerful, quantitative framework for investigating the functional morphology of parasite attachment structures and their role in host-parasite co-evolution. The protocols outlined here enable researchers to move beyond qualitative descriptions to test specific hypotheses about how ecological factors, evolutionary history, and functional demands shape parasite morphology. Through careful application of these methods—from standardized imaging and landmarking to sophisticated statistical analysis and phylogenetic comparison—we can decipher the complex relationship between form and function in parasitic organisms. The continued integration of GMM with genomic, ecological, and experimental approaches will further enhance our understanding of co-evolutionary dynamics and may inform novel strategies for parasite control.

Application Note

The study of morphological adaptation in parasites provides critical insights into host-parasite co-evolution and ecological specialization. Geometric morphometrics (GM) has emerged as a powerful alternative to traditional linear morphometrics, enabling a more nuanced and powerful analysis of shape by preserving the complete geometry of anatomical structures throughout the statistical analysis [15] [16]. This approach is particularly valuable for analyzing the sclerotized haptoral structures of monogenean flatworms, which are crucial for attachment and survival. In the genus Diplorchis, parasites that infect the urinary bladder of anurans, the haptoral anchors are not only taxonomically informative but also represent a model system to understand how host species and environmental factors drive morphological variation [17] [18]. This application note details a protocol for quantifying and interpreting shape variation in Diplorchis haptoral anchors, providing a framework for understanding morphological adaptation in parasites.

Key Findings from the Case Study

A recent study investigating six recorded and one unidentified species of Diplorchis in China revealed significant morphological variation driven by multiple factors [17] [18]. The key findings are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Summary of Key Findings on Shape Variation in Diplorchis Haptoral Anchors

| Analysis Level | Key Finding | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Interspecific | Significant differences in anchor shape and size among the seven Diplorchis species. | Anchor morphology can serve as a reliable basis for species identification within the genus. |

| Intraspecific (Geographic) | Significant differences in anchor form, body size, and haptor size in the same species from different localities. | Habitat environment influences host biology/behavior, which in turn affects the parasite's attachment organ. |

| Intraspecific (Host-driven) | In two species from the same location, anchor and sucker size were not significantly different, but body and haptor size were. | Significant differences in anchor shape suggest that the attachment mechanism is species-specific and related to anchor shape variation. |

| Phylogenetic Signal | (Noted in related monogenean studies) Shape and size of haptoral anchors, particularly ventral ones, can show significant phylogenetic signal. | Common evolutionary history can be a major factor determining anchor form, alongside adaptive pressures [19] [20]. |

The study demonstrated that geometric morphometrics could successfully discriminate species and detect subtle shape variations linked to geographical isolation and host factors. The morphological variation in anchors is thus not random but is influenced by a combination of host species, habitat, and ecological environment, providing a basis for a deeper understanding of host-parasite interactions [17] [18].

Experimental Protocol

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for a geometric morphometric analysis of monogenean haptoral anchors, from specimen preparation to statistical interpretation.

Detailed Step-by-Step Procedures

Specimen Collection and Preparation

- Source Parasites: Collect Diplorchis specimens from the urinary bladder of anuran hosts. The cited study sampled specimens from museum collections held at institutions like the School of Life Sciences, Yunnan Normal University [17].

- Selection Criteria: Carefully screen specimens and exclude any anchors that show apparent deformation, tears, or ruptures to ensure data quality. A final set of 82 specimens was used in the foundational study [17].

- Mounting: For imaging, mount the whole parasite body on a standard microscope slide to ensure the haptor and its anchors are correctly oriented and visible [18].

Image Acquisition

- Equipment: Use a high-quality light microscope (e.g., Olympus BX53) connected to a digital camera and imaging software (e.g., cellSens ver.2.2) [17] [18].

- Standardization: Capture images at a consistent magnification. Ensure the anchor is in clear focus and not obscured by other structures like eggs or host tissue.

- Data Management: To avoid data duplication, mark and photograph only one anchor (e.g., the right anchor) per specimen [18].

Landmark Digitization

This step converts morphological structures into quantitative data. Landmarks are homologous points that can be reliably identified across all specimens.

- Software: Input images into

tpsUtilto create a TPS file. Then, usetpsDig2to collect landmark coordinates [18] [21]. - Landmark Configuration: The protocol for Diplorchis used a combination of fixed landmarks and semi-landmarks [18]:

- Six Fixed Landmarks: Precisely defined homologous points (e.g., tip of the hamuli, tip of the guard, tip of the handle) [18].

- Fourteen Semi-landmarks: Placed along curves between fixed landmarks to capture outline geometry (e.g., from the most prominent point of the guard to the lowest point of the shaft) [18].

- Landmark Type Overview:

Table 2: Landmark Types in Geometric Morphometrics [21]

| Type | Name | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | Anatomical Landmarks | Points of clear biological/anatomical significance. | Tip of the hamuli [18]. |

| Type II | Mathematical Landmarks | Points defined by geometric properties (e.g., point of maximum curvature). | The base of the prominent crest [18]. |

| Type III | Constructed Landmarks | Points defined by their relative position to other landmarks. | The midpoint between two other landmarks. |

The following diagram illustrates the application of these landmark types on a schematic haptoral anchor.

Procrustes Superimposition and Statistical Analysis

- Generalized Procrustes Analysis (GPA): Import the landmark data into specialized software like MorphoJ. Perform GPA to remove the effects of size, position, and orientation by scaling, translating, and rotating landmark configurations. This creates a set of Procrustes shape coordinates for analysis [18] [21].

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Perform a PCA on the Procrustes coordinates to identify the major independent axes (Principal Components) of shape variation within the dataset. This helps visualize the main patterns of shape change and the distribution of different groups in a morphospace [18] [19].

- Canonical Variate Analysis (CVA): Use CVA to maximize the separation among pre-defined groups (e.g., species or populations). This is a powerful tool for testing hypotheses about group differences [18].

- Statistical Testing: Assess the significance of shape differences between groups using a permutation test (e.g., with 10,000 iterations, α = 0.05) [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software for Geometric Morphometrics

| Item | Function/Description | Example Software/Version |

|---|---|---|

| Light Microscope with Camera | High-resolution imaging of sclerotized structures. | Olympus BX53 [17]. |

| Image Management Software | Creates and manages TPS files from images. | tpsUtil (v1.82) [21]. |

| Landmark Digitization Software | Collects 2D landmark coordinates from images. | tpsDig2 (v2.32) [18] [21]. |

| Geometric Morphometrics Analysis Software | Performs Procrustes fitting, PCA, CVA, and visualization. | MorphoJ (v1.08) [18] [21]. |

| Statistical Computing Environment | Advanced statistical analysis and custom scripting. | R (v4.3.2) with Momocs and dplyr packages [21]. |

| Furfuryl hexanoate | Furfuryl hexanoate, CAS:39252-02-3, MF:C11H16O3, MW:196.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Capryl alcohol-d18 | Capryl alcohol-d18, CAS:69974-54-5, MF:C8H18O, MW:148.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Role of GM in Understanding Biogeographic Patterns and Evolutionary Constraints

Geometric morphometrics (GM) has emerged as a powerful quantitative method for analyzing biological shape, providing unprecedented insights into biogeographic patterns and evolutionary constraints. This approach utilizes geometric coordinates of morphological landmarks to statistically analyze shape variation and its relationship to biological, ecological, and evolutionary factors [22]. Within parasitology, GM offers a sophisticated toolkit for understanding how parasite attachment structures evolve in response to host specificity, environmental pressures, and geographical distribution [17] [8].

The application of GM to parasite research represents a significant advancement over traditional linear morphometrics by enabling researchers to visualize complex shape changes, separate size and shape variation, and statistically test hypotheses about evolutionary adaptation [17] [22]. This is particularly valuable for studying parasitic organisms where attachment organs are critical for host exploitation and survival, and where morphological variations often reflect adaptations to specific host environments and geographical contexts [17] [8].

Key Applications in Parasite Biogeography and Evolution

Analyzing Attachment Structure Evolution

The morphological variation of specialized attachment structures in parasites provides critical insights into evolutionary adaptations driven by host relationships and environmental factors. In monogenean flatworms of the genus Diplorchis, geometric morphometric analyses of haptoral anchors have revealed significant interspecific and intraspecific differences correlated with host species and geographical location [17]. These shape variations directly influence attachment mechanisms and reflect adaptive responses to ensure stable anchorage in different host environments.

Similarly, studies of cymothoid isopods have demonstrated that dactylus shape (hook-like appendages) strongly correlates with parasitic mode, where externally-attaching species exhibit differently shaped dactyli compared to gill- and mouth-attaching species [8]. This morphological variation reflects functional demands of attachment in different microhabitats and appears to be primarily driven by ecological factors rather than phylogenetic constraints, indicating convergent evolution in attachment mechanisms [8].

Resolving Biogeographical Patterns

GM approaches have proven valuable for elucidating biogeographical distributions and evolutionary relationships among parasite populations across different regions. Research on crane flies of the genus Ischnotoma utilized wing venation landmarks to successfully discriminate between subgenera from Neotropical and Australian regions, revealing clear morphological separations that correspond to geographical distributions [23]. The analysis demonstrated complete separation of three subgenera through Canonical Variate Analysis, providing insights into their evolutionary relationships and biogeographical history [23].

The application of GM has also revealed intraspecific geographical variations in parasite morphology. For instance, the same Diplorchis species collected from different localities exhibited significant differences in anchor form, body size, and haptor size, reflecting how different habitat environments affect host biological and behavioral activities, which subsequently influences parasite attachment structures [17].

Assessing Environmental Influences

Geometric morphometrics enables precise quantification of how environmental factors shape parasite morphology through both direct and host-mediated effects. Studies have shown that parasites from the same host species but different geographical locations can exhibit significant morphological divergence in their attachment structures, suggesting local environmental adaptation [17]. Interestingly, when two different parasite species inhabit the same geographical location, they may show no significant differences in anchor or sucker size, while still differing significantly in body size and haptor size, indicating complex environmental filtering mechanisms [17].

Table 1: Key Findings from Geometric Morphometric Studies of Parasites

| Parasite Group | Biological Structure Analyzed | Key Finding | Evolutionary Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diplorchis species (Monogenea) [17] | Haptoral anchors | Significant shape differences among species and between same species from different localities | Adaptation to host species and local environmental conditions |

| Cymothoid isopods [8] | Pereopod dactyli | Clear shape differences between externally-attaching and internally-attaching species | Functional adaptation to parasitic mode and microhabitat |

| Ischnotoma crane flies [23] | Wing venation | Complete separation of three subgenera using CVA | Biogeographical patterning and evolutionary relationships |

| Varroa destructor-infested bees [24] | Wing venation | 96.4% separation between infested and control groups | Environmental stress effects on host morphology |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Landmark-Based Geometric Morphometrics Protocol

Objective: To quantify and analyze shape variation in parasite attachment structures or host morphological features affected by parasitism.

Materials and Equipment:

- Specimens (parasites or hosts)

- Stereomicroscope with calibrated digital camera

- Specimen preparation materials (slides, mounting medium)

- Computer with morphometric software (tpsSuite, MorphoJ, R with geomorph package)

Procedure:

Specimen Preparation and Imaging

- Fix and preserve specimens according to standard protocols for the target organisms

- Mount specimens consistently to minimize orientation artifacts

- Capture high-resolution digital images using standardized magnification and lighting conditions

- Ensure all relevant structures are clearly visible and in focus

Landmark Digitization

- Select homologous landmarks that accurately capture the shape of the structure of interest

- Define landmark types (Type I: discrete anatomical junctions; Type II: maxima of curvature; Type III: extreme points)

- Use tpsDig2 software to plot coordinates for all landmarks across all specimens [8] [24]

- Include semi-landmarks for curves and outlines where necessary [8]

Generalized Procrustes Analysis (GPA)

- Superimpose landmark configurations to remove effects of position, orientation, and scale

- Rotate configurations to minimize Procrustes distance between corresponding landmarks

- Obtain Procrustes coordinates representing shape variables for subsequent analysis

Statistical Analysis of Shape Variation

- Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify major axes of shape variation

- Conduct Canonical Variate Analysis (CVA) to test for group differences (e.g., by species, location, host)

- Implement regression analysis to assess allometry (shape-size relationships)

- Use thin-plate spline visualizations to illustrate shape changes [17] [23]

Interpretation and Visualization

- Generate deformation grids to visualize shape changes along significant axes

- Create scatterplots of principal components or canonical variates

- Statistically test hypotheses about group differences using MANOVA procedures

- Correlate shape variables with ecological, geographical, or host factors

Figure 1: Workflow for landmark-based geometric morphometric analysis of parasite structures, showing key stages from specimen collection to results interpretation.

Case Study: Analysis of Monogenean Haptoral Anchors

Background: This protocol adapts methodology from studies of Diplorchis species to analyze shape variation in monogenean haptoral anchors in relation to host specificity and geographical distribution [17].

Specific Modifications:

- Focus on haptoral anchors as key attachment structures

- Include landmarks capturing anchor point, shaft curvature, and blade morphology

- Compare specimens from different host species and geographical locations

- Analyze both shape and size variables to assess allometric effects

Analytical Approach:

- Test for significant differences in anchor shape between species using CVA

- Assess correlation between geographical distance and morphological divergence

- Evaluate effect of host ecology on anchor morphology using multivariate regression

- Map shape changes onto phylogenetic hypotheses when available

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Parasite Geometric Morphometrics

| Item | Specification | Application/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Imaging System | Stereomicroscope with digital camera (e.g., Nikon DS-Fi1, Olympus DP80) [8] | High-resolution image capture of parasite structures |

| Specimen Mounting | Microscope slides, coverslips, mounting medium | Consistent specimen orientation for imaging |

| Landmarking Software | tpsDig2 [8] [24] | Precise digitization of landmark coordinates |

| Morphometric Analysis Software | MorphoJ, tpsRelw, R with geomorph package [23] | Statistical shape analysis and visualization |

| Phylogenetic Analysis Tools | Molecular sequencing reagents, phylogenetic software | Contextualizing morphological variation within evolutionary framework |

| Reference Specimens | Voucher specimens from museum collections [23] | Ensuring taxonomic accuracy and morphological comparison |

| Cinnamyl azide | Cinnamyl Azide | |

| Quadazocine mesylate | Quadazocine Mesylate|Opioid Receptor Antagonist | Quadazocine mesylate is a potent, non-selective silent antagonist at μ-, κ-, and δ-opioid receptors. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Visualization Approaches for Shape Analysis

Visualizing Shape Deformation and Variation

Effective visualization is crucial for interpreting geometric morphometric results. The following approaches facilitate understanding of complex shape data:

Thin-Plate Spline Deformation Grids: These visualizations illustrate shape changes between specimens or groups by deforming a reference grid into a target configuration. They are particularly useful for showing how specific anatomical regions vary between groups [17].

Principal Component Scatterplots: Plots of specimen scores along major principal components reveal patterns of shape variation and grouping. Coloring points by factors such as species, geographical origin, or host type helps identify morphological trends [23].

Canonical Variate Plots: When testing a priori groupings, CVA plots show the maximum separation between groups, making them ideal for visualizing species differences or geographical variants [23].

Figure 2: Relationship between analytical steps and visualization methods in geometric morphometrics, showing how raw landmark data is transformed into interpretable visual outputs.

Data Analysis and Interpretation Framework

Statistical Framework for Hypothesis Testing

Robust statistical analysis is essential for drawing meaningful conclusions from geometric morphometric data. Key analytical approaches include:

Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA): Tests for significant differences in shape between predefined groups. In parasite studies, this might involve comparing attachment structures between species, populations from different geographical regions, or parasites from different host species [17] [24].

Regression Analysis: Assesses relationships between shape variables and continuous predictors such as size (allometry), geographical coordinates, or environmental variables. For example, studying how parasite attachment structures change with body size provides insights into developmental constraints [8] [23].

Partial Least Squares (PLS) Analysis: Examines covariation between shape data and other variable sets, such as ecological parameters or host traits. This approach is particularly useful for identifying coordinated changes between parasite morphology and host characteristics [17].

Integrating Geometric Morphometrics with Complementary Approaches

To fully understand biogeographic patterns and evolutionary constraints, GM should be integrated with other analytical approaches:

Molecular Phylogenetics: Combining shape analysis with molecular phylogenies helps distinguish between phylogenetic constraint and adaptive evolution in parasite morphology [8].

Environmental Data Analysis: Correlating shape variation with environmental variables (temperature, humidity, altitude) reveals selective pressures shaping parasite morphology across geographical gradients [17].

Host-Parasite Coevolution Analysis: Simultaneous analysis of host and parasite morphological traits identifies patterns of coevolution and adaptation in parasite attachment structures and host attachment sites [17] [8].

Geometric morphometrics provides a powerful framework for investigating biogeographic patterns and evolutionary constraints in parasite morphology. The protocols and applications outlined in this document demonstrate how GM approaches can reveal subtle shape variations in parasite attachment structures that reflect adaptations to host specificity, environmental conditions, and geographical distribution. By implementing standardized protocols for specimen preparation, landmark digitization, and statistical analysis, researchers can generate comparable data across studies and parasite taxa, advancing our understanding of how morphological evolution supports parasitic lifestyles across diverse biogeographic contexts.

From Specimen to Statistical Output: A Step-by-Step GM Protocol for Parasitology

Geometric morphometrics (GM) has revolutionized the quantitative analysis of biological forms, providing powerful tools for capturing and analyzing the shape of anatomical structures. Within parasitology, this approach is particularly valuable for investigating the intricate sclerotized structures of parasites, such as the haptoral anchors of monogeneans. These structures are not only critical for taxonomic identification but also reflect adaptations to specific hosts and environments [17]. Establishing a robust, reproducible workflow for imaging, digitization, and software selection is therefore fundamental to generating high-quality, comparable data. This document outlines application notes and detailed protocols for integrating geometric morphometrics into parasitology research, providing a structured guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in the morphological analysis of parasites.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Software and Research Reagents

A successful GM workflow relies on a combination of specialized software for image processing, digitization, and statistical analysis, alongside standard laboratory reagents for specimen preparation. The table below summarizes the core digital toolkit and key reagents used in the preparation of parasite specimens for morphometric analysis.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Parasite Specimen Preparation

| Item Name | Function/Application in GM Workflow |

|---|---|

| Sclerotized Stains | Selective staining of chitinous structures (e.g., haptoral anchors, hooks) to enhance contrast for imaging. |

| Clearing Agents | Rendering soft tissues translucent to enable clear visualization of embedded sclerites without dissection. |

| Polyvinyl Lactophenol | A common mounting medium that simultaneously clears, fixes, and preserves parasite specimens on microscope slides. |

| Neutral Buffered Formalin | Standard fixative for preserving the structural integrity of collected parasite specimens prior to staining and mounting. |

| (Rac)-Pregabalin-d10 | (Rac)-Pregabalin-d10|High-Quality Isotopically Labeled Standard |

| Anticancer agent 30 | Anticancer Agent 30|Research Compound|RUO |

Table 2: Core Software Toolkit for Geometric Morphometrics Analysis

| Software/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in GM Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Image Processing | GM (GraphicsMagick) via Node.js, ImageJ |

Batch processing (contrast, transparency), scaling, and orientation standardization of specimen images [25] [26]. |

| Digitization & Landmarking | tpsDig2, MorphoJ | Defining and recording 2D/3D coordinates of homologous landmarks on digital images. |

| Statistical Shape Analysis | MorphoJ, R (geomorph package) | Performing Procrustes superimposition, PCA, MANOVA, and visualizing shape changes. |

Experimental Protocols for Parasite Structure Analysis

Protocol: Specimen Preparation and Image Acquisition of Monogenean Haptoral Anchors

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used in contemporary studies of Diplorchis species and other monogeneans, focusing on generating consistent, high-quality images for landmarking [17].

Materials:

- Fixed monogenean specimens (e.g., from host urinary bladder or gills)

- Microscope slides and coverslips

- Polyvinyl lactophenol or equivalent mounting medium

- Compound microscope with camera system (calibrated for scale)

- Image capture software

Methodology:

- Specimen Selection: Select specimens with no apparent deformation, tears, or ruptures in the haptoral structures. This is critical for accurate shape representation [17].

- Mounting: Place the specimen in a drop of polyvinyl lactophenol on a microscope slide. Carefully position the specimen to ensure the haptor and its anchors lie flat and are fully extended. Gently lower a coverslip, avoiding lateral movement that could distort structures.

- Curing: Allow the mounted slide to cure for 24-48 hours to stabilize the specimen and ensure the medium has hardened.

- Image Acquisition: Using a compound microscope with a calibrated camera, capture high-resolution micrographs of the haptoral anchors.

- Use consistent magnification across all specimens.

- Ensure the focal plane captures the maximum two-dimensional outline of all anchor components.

- Include a scale bar within each image frame for subsequent size calibration during digitization.

- Save images in a lossless format (e.g., TIFF, PNG) to preserve data integrity.

Protocol: Image Pre-processing with GraphicsMagick (GM)

Automated pre-processing ensures uniformity in image quality, which reduces batch effects and facilitates more accurate landmark placement.

Materials:

Methodology:

- Batch Contrast Enhancement: Run a script to standardize image contrast. The

contrast()function in GM allows for enhancement or reduction of contrast using a multiplier value [26]. - Background Standardization: Use the

transparent()function to remove or unify background colors, creating a consistent backdrop that improves landmark visibility [25]. - Image Scaling: Use GM's

resize()function to scale all images to a uniform pixel dimension based on the known scale bar, ensuring all subsequent measurements are comparable.

Protocol: Landmarking and Data Generation

This protocol details the process of converting morphological structures into quantitative shape data.

Materials:

- Pre-processed and scaled specimen images

- Digitization software (e.g., tpsDig2)

Methodology:

- Landmark Definition: Define a set of Type I (homologous anatomical points) and Type II (extremes of maximum curvature) landmarks on the haptoral anchor. For a monogenean anchor, this typically includes the point of insertion, the tip of the root, and the point of maximum curvature along the shaft and blade [17].

- Landmark Digitization:

- In tpsDig2, open the image file and sequentially place landmarks according to the defined scheme.

- Ensure the order of landmark placement is consistent for every specimen.

- Repeat the process for all specimens in the dataset.

- Data File Creation: The software will generate a TPS file containing the Cartesian coordinates (x, y) of all landmarks for all specimens. This file is the primary data input for subsequent statistical shape analysis.

Workflow Visualization and Logical Pathway

The entire process, from specimen collection to statistical insight, can be visualized as a sequential workflow. The following diagram, generated using Graphviz and adhering to the specified color palette, outlines the logical pathway and critical decision points.

Diagram Title: Geometric Morphometrics Workflow for Parasitology

Application in Parasite Research: A Case Study

The power of this GM workflow is exemplified by research on the genus Diplorchis, monogeneans parasitizing the urinary bladder of anurans. A 2025 study utilized geometric morphometrics to analyze the haptoral anchors of six Diplorchis species and one unidentified species [17].

Key Findings and Workflow Application:

- Species Discrimination: Geomorphometric analyses revealed significant interspecific differences in anchor shape and size, establishing anchor morphology as a reliable character for species identification within the genus [17]. This addresses the challenge of species identification when molecular data from older specimens are unavailable.

- Environmental Adaptation: The study documented significant intraspecific differences in anchor form, body size, and haptor size in the same parasite species collected from different geographic localities. This suggests that environmental factors and host ecology can drive morphological variation, potentially reflecting an adaptive response to ensure stable attachment in different host populations [17].

- Attachment Mechanics: The significant differences in anchor shape among species suggest a relationship between morphological variation and the underlying attachment mechanism, providing insights into host-parasite interactions at a functional level [17].

This case study demonstrates how a rigorously applied GM workflow can move beyond simple description to address complex questions about systematics, adaptation, and functional morphology in parasitology.

Geometric morphometrics (GM) has revolutionized the quantitative analysis of biological forms, proving particularly valuable in parasitology for distinguishing species and investigating host-parasite interactions. The analysis of parasite sclerites, such as the haptoral anchors of monogeneans, relies heavily on the precise digitization of homologous points. This application note delineates the critical distinction between traditional landmarks and semi-landmarks, providing a structured framework for selecting the appropriate approach in morphometric studies of parasite sclerites. We detail experimental protocols, provide a comparative analysis of quantitative data, and list essential research reagents, all framed within the context of advanced parasitic research.

In geometric morphometrics, landmarks are defined as discrete, homologous points that are biologically comparable across all specimens in a study. For parasite sclerites, examples include the precise tip of a hamulus or the point of bifurcation of a hook root [27]. These points represent true biological homologues. However, many biologically significant structures, such as the curved shafts of anchors or smooth margins of sclerites, lack a sufficient number of such discrete points to capture their form adequately.

Semi-landmarks are points used to quantify the geometry of these curves and surfaces [28]. They are not considered homologous in their initial placement but are made mathematically comparable through algorithms that slide them along a tangent direction or surface to minimize a bending energy or Procrustes distance against a mean reference form [29]. This process allows for the dense sampling of morphology between the fixed landmarks, enabling a comprehensive analysis of shape.

The choice between these methods is not merely technical; it directly influences the biological interpretation of results. Analyses based on semi-landmarks are considered "approximations of reality that require cautious interpretation" [28], as their locations can be influenced by the chosen algorithm and their density.

Theoretical Foundation and Decision Framework

The core of the landmark versus semi-landmark choice rests on the availability of homologous points and the research objective.

When to Use Traditional Landmarks

- Structures with abundant homologies: Sclerites with numerous distinct anatomical features (e.g., notches, tips, intersections) are well-suited for landmark-only analysis.

- Focus on discrete points of homology: When the research question specifically concerns the variation in the relative positions of known, developmentally conserved structures.

- Studies requiring minimal algorithmic influence: To avoid potential biases introduced by sliding algorithms, a landmark-only approach is more conservative.

When to Incorporate Semi-Landmarks

- Analyses of curves and outlines: The curved shafts of anchors, marginal hooks, or the overall outline of a sclerite are prime candidates for semi-landmarks [30].

- Dense sampling of form: When the research aims to capture the "overall form" of a sclerite beyond a few discrete points, semi-landmarks "increase the density of the shape information" [28].

- Structures with few true landmarks: This is a common scenario in parasitology, where sclerites may offer only a handful of unambiguous landmarks, making semi-landmarks essential for a powerful geometric analysis [28].

Table 1: Decision Matrix for Landmark and Semi-Landmark Application in Sclerite Analysis

| Research Scenario | Recommended Approach | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Comparing specific hook tip morphology between species | Traditional Landmarks | Focuses analysis on discrete, homologous points of functional significance. |

| Quantifying shape variation of a curved anchor shaft | Semi-Landmarks | Allows for the quantification of continuous curvature that lacks discrete homologies. |

| Comprehensive analysis of entire haptoral anchor form | Combined Approach (Landmarks + Semi-Landmarks) | Fixed landmarks define core homologies; semi-landmarks capture the intervening geometry [30]. |

| Ontogenetic studies of sclerite growth | Combined Approach | Tracks growth of specific landmarks while capturing allometric changes in overall shape. |

Experimental Protocols for Sclerite Morphometrics

Protocol 1: Isolation and Preparation of Haptoral Sclerites

Accurate morphometric analysis requires cleanly isolated sclerites free from obscuring soft tissue.

- Sample Collection: Fix parasites removed from the host in 70% ethanol for morphological study or 96% ethanol for molecular analysis and subsequent sclerite isolation [31].

- Digestion of Soft Tissue:

- Place individual parasites on a polylysine-coated or concavity slide to prevent loss of minute sclerites.

- Apply a digestion buffer. One effective buffer contains Tris-HCl, EDTA, Sodium Dodecyl Sulphate (SDS), and proteinase K as the active enzyme [31].

- Incubate until the soft tissue is sufficiently digested, leaving the chitinous sclerites intact.

- Washing and Mounting: Carefully wash the digested material with distilled water to remove buffer residues. Mount the cleaned sclerites on a stub for Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) or on a slide for light microscopy.

Protocol 2: Data Acquisition and Digitization

This protocol covers the process from image capture to point digitization.

- Imaging: Capture high-resolution images of the isolated sclerites using a calibrated light microscope or SEM.

- Defining the Landmark Schema:

- Identify a set of fixed landmarks that are unambiguously homologous across all specimens (e.g., the tip of the anchor, the base of the root).

- Define curves between these fixed landmarks to be sampled with semi-landmarks. For instance, place a curve along the ventral root and another along the dorsal root [27].

- Digitization:

- Digitize all fixed landmarks.

- Place semi-landmarks equidistantly along the pre-defined curves. Software such as tpsDig2 or MorphoJ is commonly used for this process. The number of semi-landmarks should be consistent for all specimens.

Protocol 3: Sliding Semi-Landmarks and Statistical Analysis

This step makes semi-landmarks comparable for statistical shape analysis.

- Sliding Semi-Landmarks: Use geometric morphometric software (e.g., tpsRelw, geomorph R package) to slide the semi-landmarks. The two primary criteria are:

- Minimize Bending Energy: Assumes the change between forms requires minimal deformation energy.

- Minimize Procrustes Distance: Slides points to minimize the overall Procrustes distance among specimens [29].

- Generalized Procrustes Analysis (GPA): Superimpose the entire configuration of landmarks and slid semi-landmarks to remove the effects of position, orientation, and scale.

- Statistical Analysis: Analyze the Procrustes coordinates using multivariate statistics like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to visualize major shape trends, or Discriminant Function Analysis to test for shape differences between pre-defined groups (e.g., species, populations) [17].

The following workflow diagram visualizes the complete process from specimen preparation to data analysis:

Data Presentation and Comparative Analysis

The application of these methods in parasitology has yielded significant insights. A study on Diplorchis species demonstrated that geometric morphometrics of haptoral anchors could reveal significant interspecific differences, supporting species identification [17]. Furthermore, the same study found intraspecific shape variation correlated with geographical location, highlighting the influence of environmental factors.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Landmark Types for Parasite Sclerite Analysis

| Characteristic | Traditional Landmarks | Semi-Landmarks |

|---|---|---|

| Basis of Homology | Developmental/Evolutionary homology [28] | Algorithmic point correspondence [28] |

| Ideal for Quantifying | Discrete points (tips, junctions) | Curves, outlines, surfaces |

| Data Density | Low (limited by number of homologies) | High (user-defined density) [30] |

| Influence of Method | Low | High (varies with algorithm and density) [28] |

| Primary Analysis Software | tps series, MorphoJ, R (geomorph) | tps series, MorphoJ, R (geomorph) |

| Role in Sclerite Studies | Core homologous framework; tracking specific points | Capturing overall form and curvature |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful geometric morphometric analysis of parasite sclerites depends on specific laboratory materials and reagents.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Sclerite Morphometrics

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol (70%, 96%) | Parasite fixation and preservation. 96% ethanol is preferred for specimens destined for molecular analysis or sclerite isolation. | Preserves sclerites without excessive hardening that can cause brittleness [31]. |

| Digestion Buffer | Enzymatic removal of soft tissue to isolate sclerites. | Contains Tris-HCl, EDTA, SDS, and proteinase K to digest tissue while leaving chitinous sclerites intact [31]. |

| Polylysine-coated Slides | Adhesive slides to prevent loss of microscopic sclerites during digestion and washing. | Creates a positively charged surface that binds cells and structures, minimizing sample loss [31]. |

| Glycerine Ammonium Picrate (GAP) | A mounting medium for temporary or semi-permanent slides for light microscopy. | Used to clear and mount whole parasites for initial morphological examination and sclerite measurement [31]. |

| Geometric Morphometric Software | For digitizing, sliding, and analyzing landmark data. | Essential tools like tpsDig2, MorphoJ, and the geomorph package in R form the computational backbone of the analysis. |

| Iloprost-d4 | Iloprost-d4, MF:C22H32O4, MW:364.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| N,3-diethylaniline | N,3-diethylaniline, MF:C10H15N, MW:149.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The strategic selection of landmarks and semi-landmarks is fundamental to robust geometric morphometric analysis of parasite sclerites. Traditional landmarks provide the foundational framework of homology, while semi-landmarks empower researchers to capture and quantify the continuous morphological variation of curves and surfaces. By adhering to the detailed protocols and decision frameworks outlined in this application note, researchers can effectively leverage these powerful tools. This approach facilitates a deeper understanding of parasite taxonomy, evolution, and host-parasite interactions, generating high-quality, quantitative data for a broader thesis in parasitology.