DNA Barcoding and Metabarcoding in Medical Parasitology: A Revolutionary Tool for Precision Identification and Diagnosis

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of DNA barcoding and metabarcoding in identifying medically important parasites.

DNA Barcoding and Metabarcoding in Medical Parasitology: A Revolutionary Tool for Precision Identification and Diagnosis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of DNA barcoding and metabarcoding in identifying medically important parasites. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of using standardized genetic markers, such as COI and 18S rRNA, for species delineation. It delves into advanced methodological applications, from high-throughput screening of intestinal parasites to vector identification, and critically examines technical challenges and optimization strategies. By comparing molecular methods with traditional microscopy and serology, the review validates DNA barcoding as an essential tool for enhancing diagnostic accuracy, supporting biodiversity studies, and informing public health interventions against parasitic diseases.

The Genetic Foundation: From Single Loci to Community Profiling

In the fields of molecular ecology, biodiversity research, and medical parasitology, DNA barcoding and DNA metabarcoding have become core molecular tools that overcome the limitations of traditional morphological identification [1]. Both techniques rely on the sequencing of standardized genetic marker regions to identify organisms, but they differ fundamentally in their scale, application, and technical execution [1]. DNA barcoding provides species-level identification of individual biological specimens, while DNA metabarcoding enables the simultaneous characterization of entire communities of organisms from complex environmental samples [1] [2]. These techniques are particularly valuable in medical parasite research, where they enable precise identification of pathogenic species, detection of cryptic species complexes, and discovery of previously unrecognized parasites in clinical samples [2] [3] [4]. This application note details the core principles, methodologies, and applications of both approaches within the context of medical parasitology research and drug development.

Core Definitions and Conceptual Frameworks

DNA Barcoding: The Molecular ID for Individual Specimens

DNA barcoding is a technique for species identification of individual organisms using a short, standardized gene fragment [1] [5]. Proposed by Canadian scientist Hebert in 2003, this method functions as a "molecular ID" system, where specific DNA sequences serve as unique identifiers for species [1] [6]. The technique requires that standardized genetic markers meet three core conditions: (1) contain high sequence conservation within the same species (small intraspecific variation), (2) demonstrate significant divergence between different species (large interspecific variation), and (3) be easily amplified with universal primers [1].

Standardized barcode markers have been established for different biological groups. For animals, the mitochondrial Cytochrome c Oxidase Subunit I (COI) gene serves as the primary barcode, approximately 650 base pairs in length, capable of distinguishing more than 90% of animal species [1] [4]. For plants, a combination of two chloroplast genes (rbcL and matK) is typically used [1] [5]. For fungi and parasites, the Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) region has emerged as the standard barcode due to its high copy number and rapid evolution rate, providing excellent species discrimination [1] [5].

DNA Metabarcoding: Community-Wide Species Profiling

DNA metabarcoding represents a scale expansion of DNA barcoding, enabling the simultaneous identification of multiple taxa within complex samples [1]. This approach extracts total DNA from samples containing mixtures of organisms (such as water, soil, gut contents, or blood) and uses high-throughput sequencing of barcode genes to generate a complete inventory of community species composition [1] [7].

The fundamental paradigm difference between the two techniques can be summarized as: DNA barcoding answers "What species is this one?" while metabarcoding answers "Which species are in this mixture?" [1]. This community-level analysis is particularly powerful for studying host-associated eukaryotic endosymbionts, including parasites, protozoa, and helminths, where complex multi-species interactions influence host health and disease outcomes [2] [8].

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between DNA Barcoding and DNA Metabarcoding

| Feature | DNA Barcoding | DNA Metabarcoding |

|---|---|---|

| Research Scale | Individual organisms | Complex biological communities |

| Sample Input | Single biological specimen | Mixed environmental sample (soil, water, gut content) |

| Core Question | "What species is this individual?" | "Which species are present in this community?" |

| Sequencing Technology | Sanger sequencing | High-throughput sequencing (Illumina, Nanopore) |

| Result Output | Single sequence for one species | Sample-sequence-abundance matrix of multiple species |

| Primary Application | Species identification of individual specimens | Biodiversity assessment of complex samples |

Workflow Comparison: Technical Approaches Side-by-Side

DNA Barcoding Workflow: Precision for Individual Specimens

The DNA barcoding workflow follows a linear, standardized process optimized for individual specimen analysis [1]:

- Sample Collection: A single biological individual or tissue with distinguishable morphology is collected, with strict avoidance of external contamination [1].

- DNA Extraction: Genomic DNA is extracted using CTAB method or commercial kits [1].

- PCR Amplification: Target barcode region is amplified using universal primers specific to the taxonomic group (e.g., COI for animals, ITS for fungi) [1] [4].

- Sanger Sequencing: PCR products are sequenced using the dideoxy chain termination method, producing one sequence approximately 500-1000bp in length per reaction [1].

- Species Identification: The resulting sequence is compared to reference databases (BOLD or GenBank) using BLAST analysis. Species identification is confirmed when sequence similarity with a reference specimen is ≥98% [1].

DNA Metabarcoding Workflow: High-Throughput Community Analysis

The DNA metabarcoding workflow is more complex, optimized for processing multiple samples simultaneously and dealing with mixed DNA templates [1] [2]:

- Sample Collection: Environmental samples containing mixed DNA from multiple organisms are collected (e.g., fecal samples, blood, water) with precautions to prevent DNA degradation [1] [7].

- Total DNA Extraction: DNA is extracted using kits capable of co-extracting DNA from diverse organisms (animals, plants, microorganisms) [1].

- Dual-Step PCR Amplification:

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Library pools are sequenced on platforms such as Illumina MiSeq/NovaSeq or Oxford Nanopore, generating millions of short sequence reads (150-300bp for Illumina, >1000bp for Nanopore) in a single reaction [1] [3].

- Bioinformatic Processing: Sequences are demultiplexed, quality-filtered, and clustered into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) or Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) representing biological species [1] [7].

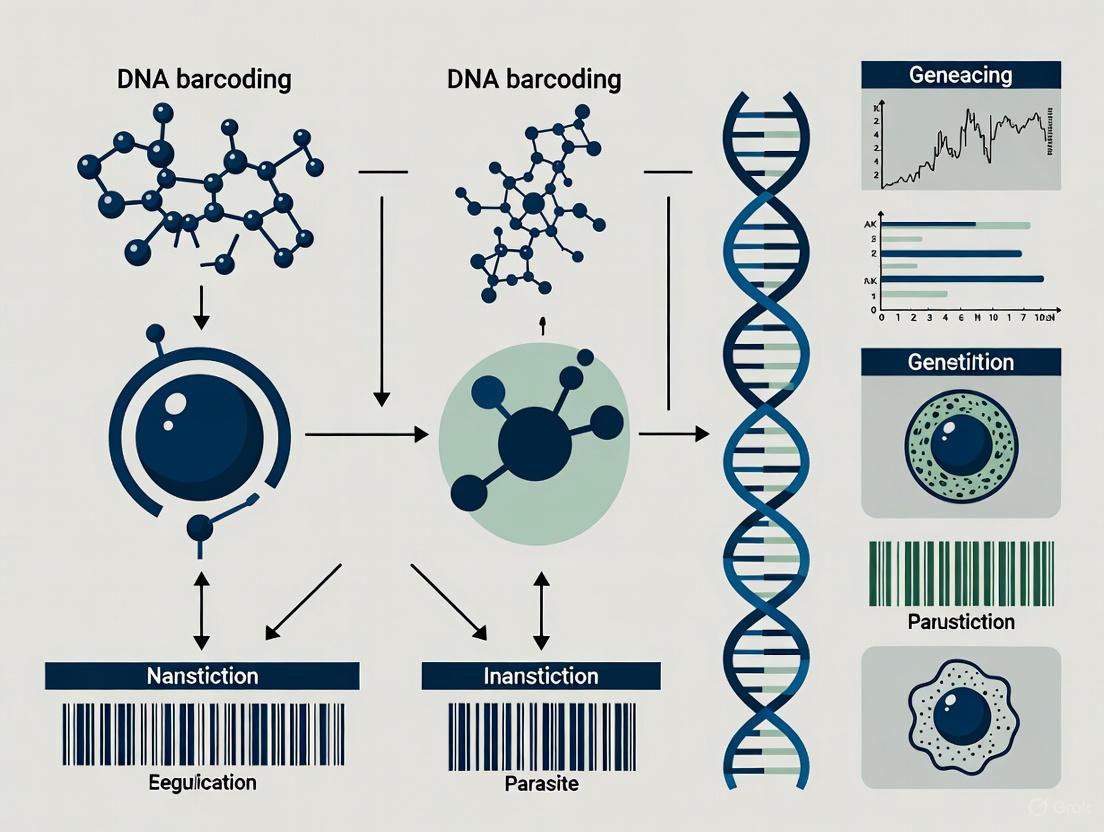

Diagram 1: Comparative Workflows of DNA Barcoding and DNA Metabarcoding

Key Research Reagents and Experimental Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for DNA Barcoding and Metabarcoding

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Primers | COI (LCO1490/HCO2198), ITS2, 18S V4-V9, rbcL, matK | Amplify standardized barcode regions across diverse taxa [2] [3] [9] |

| Blocking Primers | C3-spacer modified oligos, Peptide Nucleic Acids (PNA) | Suppress amplification of host DNA to enhance parasite detection in host-associated samples [3] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | FastDNA SPIN Kit for Soil, MP Biomedicals | Efficiently co-extract DNA from diverse organisms in complex samples [7] |

| PCR Enzymes | KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix | High-fidelity amplification with reduced error rates for sequencing applications [7] [9] |

| Sequencing Standards | Engineered mock community standards | Validate protocol accuracy and detect amplification biases [2] [8] |

| Bioinformatic Tools | BOLD, MOTHUR, QIIME2, DADA2 | Process sequence data, perform quality filtering, OTU/ASV clustering, and taxonomic assignment [1] [7] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: DNA Barcoding for Parasite Identification

This protocol adapts the DNA barcoding approach specifically for parasite identification, based on established methodologies [4]:

Sample Preparation:

- Collect individual parasite specimens or infected tissue samples under sterile conditions.

- For sand flies and other vectors, dissect and preserve thorax, legs, and wings for DNA extraction, while mounting head and abdomen for morphological validation [4].

- Fix specimens in 70-100% ethanol or freeze at -20°C until processing.

DNA Extraction:

- Extract genomic DNA using high-salt concentration protocols or commercial kits (e.g., DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit) [4].

- Include negative extraction controls to monitor contamination.

- Quantify DNA concentration using fluorometric methods and dilute to 10-15 ng/μL for PCR [9].

PCR Amplification:

- Prepare 25μL reactions containing:

- 10-15 ng template DNA

- 1X PCR buffer

- 2.0 mM MgClâ‚‚

- 0.2 mM each dNTP

- 0.4 μM each primer (e.g., LCO1490/HCO2198 for COI)

- 1.0 U DNA polymerase

- Use thermal cycling conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 94°C for 3-5 minutes

- 35-40 cycles of: 94°C for 30-45s, 45-55°C for 30-60s, 72°C for 45-90s

- Final extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes [4]

Sequencing and Analysis:

- Verify PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Purify amplicons and sequence bidirectionally using Sanger sequencing.

- Assemble contigs, check for pseudogenes or NUMTs, and compare to reference databases using BLAST [4].

- Calculate genetic distances using appropriate models (p-distance, K2P) and construct neighbor-joining trees for phylogenetic validation [4].

Protocol 2: VESPA Metabarcoding for Eukaryotic Endosymbionts

The VESPA (Vertebrate Eukaryotic endoSymbiont and Parasite Analysis) protocol provides an optimized metabarcoding approach for characterizing parasite communities in clinical samples [2] [8]:

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction:

- Collect clinical samples (feces, blood, tissue) with appropriate preservation to prevent DNA degradation.

- Extract total DNA using kits designed for mixed templates (e.g., FastDNA SPIN Kit for Soil) [7].

- Include extraction controls and mock community standards for quality assessment.

Primer Selection and Design:

- Target the 18S rRNA V4 region with specifically designed primers that maximize coverage of eukaryotic endosymbionts while minimizing off-target amplification [2] [8].

- VESPA primers demonstrate 95.2-96.8% coverage across target parasite groups, significantly outperforming previously published primers [8].

- Incorporate sample-specific barcodes and sequencing adapters for multiplexing.

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Perform dual-indexed PCR with limited cycles (25-30) to maintain community representation [2].

- Use high-fidelity polymerase to minimize amplification errors.

- Pool purified amplicons in equimolar ratios and sequence on Illumina MiSeq or similar platform with 2×250 bp paired-end chemistry [2] [7].

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Process raw sequences through quality filtering, denoising, and chimera removal.

- Cluster sequences into OTUs (97% similarity) or infer ASVs using DADA2 or similar algorithms [7].

- Assign taxonomy using curated reference databases with bootstrap thresholds (>50%) for confidence [8] [7].

- Analyze community composition and generate sample-OTU abundance matrices for downstream statistical analysis.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Molecular Identification Methods

| Performance Metric | Morphological Identification | DNA Barcoding | DNA Metabarcoding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Species Detection | 22 species (reference) | 20 OTUs (28S rDNA) | 48 OTUs (28S rDNA) |

| Resolution Capacity | Limited by cryptic species | High for well-represented species | High with sufficient reference data |

| Technical Expertise | Extensive taxonomic training required | Moderate molecular skills needed | Advanced bioinformatics skills essential |

| Throughput | Low (individual specimens) | Moderate (individual specimens) | High (multiple samples simultaneously) |

| Cost per Sample | Low | Moderate | Low to moderate (depending on scale) |

| Quantitative Accuracy | Subject to observer bias | Not applicable for communities | Semi-quantitative with PCR biases |

Applications in Medical Parasitology and Drug Development

Both DNA barcoding and metabarcoding have transformative applications in medical research and pharmaceutical development:

Pathogen Identification and Discovery: DNA barcoding enables precise identification of known parasite species, while metabarcoding facilitates detection of unexpected or novel pathogens in clinical samples [3] [7]. For example, metabarcoding has revealed previously unrecognized parasite associations with human diseases, such as Colpodella-like parasites [3].

Cryptic Species Detection: These molecular methods resolve cryptic species complexes that are morphologically identical but biologically distinct, such as the Entamoeba histolytica/dispar complex [2] [8]. This discrimination is crucial for accurate diagnosis and treatment selection.

Drug Discovery and Development: Comprehensive characterization of parasite communities enables identification of new drug targets and understanding of resistance mechanisms [6]. The ability to monitor complex parasite assemblages during clinical trials provides insights into treatment efficacy across multiple parasite taxa.

Disease Surveillance: Metabarcoding facilitates large-scale screening of vector populations and reservoir hosts, identifying potential zoonotic transmission hotspots and emerging disease threats [7] [4]. The high-throughput nature of metabarcoding makes it ideal for monitoring programs in endemic regions.

DNA barcoding and DNA metabarcoding represent complementary approaches in the molecular toolkit for parasite research and drug development. While DNA barcoding provides definitive species-level identification of individual specimens, DNA metabarcoding offers a comprehensive view of entire parasite communities in complex samples. The VESPA protocol and similar optimized workflows have significantly advanced our capacity to characterize eukaryotic endosymbiont assemblages with precision matching or exceeding traditional microscopy [2] [8]. As reference databases continue to expand and sequencing technologies become more accessible, these molecular approaches will play increasingly vital roles in understanding parasite biology, developing novel therapeutics, and implementing effective disease control strategies. Researchers should select the appropriate method based on their specific research questions, considering the trade-offs between resolution, throughput, and technical requirements outlined in this application note.

The accurate identification of parasites is a cornerstone of effective disease diagnosis, surveillance, and control. Traditional morphological methods, while useful, often fail to distinguish between closely related species, require extensive expertise, and can be time-consuming [10]. The concept of DNA barcoding—using a short, standardized genetic marker to identify species—was proposed by Paul Hebert as a solution to this taxonomic challenge [11]. This approach has since evolved from a theoretical concept into an indispensable tool in modern parasitology, revolutionizing how researchers detect, identify, and monitor medically important parasites.

In medical parasitology, the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (COI) gene of the mitochondrial genome emerged as the primary barcode region for many metazoan parasites and vectors [11]. For protozoan parasites, which often lack suitable mitochondria, the nuclear 18S small-subunit rRNA gene (18S rDNA) has become the marker of choice [3] [10]. The adoption of these standardized genetic markers has enabled the creation of comprehensive reference libraries, such as the Barcode of Life Data (BOLD) system, which facilitates rapid species identification and discovery [11].

Application Notes: The Impact of DNA Barcoding on Medical Parasitology

Resolving Diagnostic Challenges

DNA barcoding has proven particularly valuable in situations where morphological identification falls short. Key applications include:

- Differentiating morphologically identical species: Techniques like PCR-RFLP (Polymerase Chain Reaction-Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism) allow for the differentiation of pathogenic Entamoeba histolytica from non-pathogenic Entamoeba dispar and Entamoeba moshkovskii, which are visually indistinguishable under a microscope [12].

- Identifying cryptic species and complexes: Universal PCR assays targeting variable regions of the 18S gene can differentiate between over 26 valid Cryptosporidium species, whose oocysts are largely morphologically identical, enabling the tracking of zoonotic transmission [10].

- Detecting spurious parasitism: In companion animals, DNA barcoding using markers like ITS-1 and ITS-2 can identify whether parasite eggs in feces represent a genuine infection or simply passage from consumed animal feces, preventing unnecessary treatments [10].

Enhancing Surveillance and Control

The quantitative impact of DNA barcoding on parasite identification is significant. As of 2014, approximately 43% of 1,403 medically important parasite and vector species had representation in barcode databases, enabling their molecular identification [11]. This coverage continues to expand, enhancing capabilities for:

- Tracking parasite range shifts influenced by climate change, urbanization, and global trade [11].

- Identifying vector species complexes critical for understanding disease transmission dynamics and targeting control measures effectively [11].

- Detecting emerging and re-emerging parasitic diseases through accurate identification of novel pathogens in human populations [11].

Table 1: DNA Barcode Coverage of Medically Important Species (Data from 2014) [11]

| Category | Number of Species in Checklist | Species with DNA Barcodes (%) | Species with Barcode-Compliant Records (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Medically Important Species | 1,403 | 43% | 25% |

| Parasites | 308 | 45% | 26% |

| Vectors | 645 | 45% | 27% |

| Hazards | 450 | 39% | 21% |

Protocols for Modern Parasite Detection Using DNA Barcoding

Enhanced Blood Parasite Detection Using Nanopore Sequencing

Recent advances have enabled the development of a targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) approach for comprehensive blood parasite detection. The following protocol demonstrates a sophisticated method that overcomes previous limitations in field applications [3] [13].

Workflow: Blood Parasite Detection via Nanopore Sequencing

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for detecting blood parasites using a portable nanopore platform:

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Blood Parasite DNA Barcoding [3] [13]

| Reagent/Component | Function | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Primers F566 & 1776R | Amplifies 18S rDNA V4-V9 region from diverse eukaryotes | Targets >1kb region for enhanced species resolution on error-prone sequencers |

| 3SpC3_Hs1829R Blocking Primer | Suppresses host DNA amplification | C3 spacer-modified oligo competing with universal reverse primer |

| Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA) Oligo | Inhibits polymerase elongation of host DNA | Sequence-specific binding without being amplified |

| Nanopore Sequencing Kit | Prepares DNA library for sequencing | Compatible with portable nanopore devices |

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolates parasite DNA from blood samples | Effective with low parasite densities |

Procedural Details

DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from blood samples using a commercial extraction kit, such as the Machery-Nagel NucleoSpin Tissue kit, with mechanical lysis enhancement using glass beads to improve parasite DNA yield [12].

Host DNA Suppression: Implement a dual-blocking primer system to overcome host DNA contamination:

- Use the C3 spacer-modified oligo (3SpC3_Hs1829R) that competes with the universal reverse primer

- Apply the PNA oligo that inhibits polymerase elongation

- This combination selectively reduces amplification of mammalian 18S rDNA while preserving parasite DNA amplification [3]

PCR Amplification: Perform PCR amplification using universal primers F566 and 1776R, which target the 18S rDNA V4-V9 region spanning approximately 1,200 base pairs. This expanded region provides significantly better species resolution compared to the shorter V9 region alone, especially when using error-prone portable sequencers [3].

Sequencing and Analysis: Sequence the amplified products on a portable nanopore platform. Analyze the resulting sequences using bioinformatic tools, classifying them against reference databases. The established test has demonstrated sensitivity for detecting Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense, Plasmodium falciparum, and Babesia bovis in human blood samples spiked with as few as 1, 4, and 4 parasites per microliter, respectively [3] [13].

Molecular Detection of Intestinal Protozoa

For intestinal parasites, standardized PCR-based techniques provide high sensitivity and specificity compared to conventional microscopic methods [12].

DNA Extraction and Amplification Protocol

Sample Preparation: Wash fecal samples previously cultured in Modified Boeck Drbohlav's Medium to increase vegetative forms of parasites like Blastocystis spp. Pellet and store at -20°C until DNA extraction [12].

Mechanical Lysis: Resuspend the pellet in TE buffer with cover glass powder #1. Perform three lysis cycles, each consisting of:

- Cooling for 3 minutes at 4°C

- Vortex mixing for 3 minutes

- Centrifugation and supernatant transfer [12]

DNA Extraction: Complete DNA extraction using commercial kits (e.g., Machery-Nagel NucleoSpin Tissue) following manufacturer protocols for eukaryotic cells [12].

PCR Amplification: Perform species-specific or universal PCR assays depending on diagnostic needs:

- For Giardia duodenalis: Use universal PCR targeting the β-giardin locus to differentiate assemblages with zoonotic potential [10]

- For Cryptosporidium spp.: Apply universal PCR based on the 18S gene locus to differentiate species [10]

- For Blastocystis spp.: Utilize a 310 bp nested PCR for high sensitivity (detecting as few as 4 vegetative forms) [12]

Table 3: Sensitivity of Molecular Detection for Intestinal Protozoa [12]

| Parasite | Molecular Target | Sensitivity A (DNA Quantity) | Sensitivity B (Life Forms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Giardia duodenalis | Not specified | 10 fg | 100 cysts |

| Entamoeba histolytica/dispar | Not specified | 12.5 pg | 500 cysts |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | Not specified | 50 fg | 1,000 oocysts |

| Cyclospora spp. | Not specified | 225 pg | 1,000 oocysts |

| Blastocystis spp. | 1780 bp PCR | 800 fg | 3,600 vegetative forms |

| Blastocystis spp. | 310 bp nested PCR | 8 fg | 4 vegetative forms |

Discussion: Current Status and Future Directions

DNA barcoding has fundamentally transformed parasite identification, yet several challenges and opportunities remain. As of 2014, barcode coverage of medically important species (43%) lagged behind agricultural pests (54%), highlighting the need for continued expansion of reference databases [11]. Furthermore, a significant portion of parasite barcodes exist only as GenBank-mined data (42% of sequenced species), which often do not meet full barcode compliance standards, potentially limiting their diagnostic utility [11].

The future of DNA barcoding in parasitology points toward several promising directions:

- Portable sequencing technologies: The development of field-deployable nanopore sequencing platforms enables comprehensive parasite detection with high sensitivity and accurate species identification in resource-limited settings [3] [13].

- Expanded reference libraries: Continued efforts to sequence morphologically vouchered specimens will enhance the reliability and coverage of barcode databases [11].

- Multi-marker approaches: Combining COI with additional genetic markers improves resolution for taxonomically challenging groups [11].

- Integration with epidemiological data: Linking DNA barcode data with clinical and ecological information provides deeper insights into parasite transmission dynamics and emergence patterns [11].

As DNA barcoding continues to evolve from Hebert's original concept into increasingly sophisticated applications, it promises to further revolutionize medical parasitology, enabling more accurate diagnosis, enhanced surveillance, and more effective control of parasitic diseases worldwide.

In the field of medical parasitology, accurate species identification is fundamental for diagnosis, understanding epidemiology, and developing control strategies. DNA barcoding has emerged as a powerful tool to overcome the limitations of traditional morphological identification, which can be slow and require specialized expertise [14]. Two genetic markers have become cornerstones of this approach: the mitochondrial Cytochrome c Oxidase Subunit I (COI) gene for animals and the nuclear 18S ribosomal RNA (18S rRNA) gene for broad eukaryote screening. This application note delineates the specific roles, protocols, and applications of these two markers within a research context focused on parasite identification, providing a structured framework for scientists and drug development professionals.

Marker Comparison and Selection Criteria

The choice between COI and 18S rRNA is dictated by the research question, target organisms, and required resolution. COI is renowned for its high resolution for species-level identification in metazoans, while 18S rRNA is valued for its universal application across the eukaryotic domain, enabling the detection of diverse parasites in a single assay [15] [16].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of COI and 18S rRNA Genetic Markers

| Feature | COI (Cytochrome c Oxidase I) | 18S rRNA (Small Subunit Ribosomal RNA) |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Location | Mitochondrial | Nuclear |

| Primary Application | Species-level identification of animals | Broad eukaryote screening and community analysis |

| Taxonomic Resolution | High (species level) [17] | Variable (often genus to family level) [14] |

| Sequence Evolution Rate | Relatively fast (25-1000x faster than 18S in foraminifera) [16] | Relatively slow, with conserved and variable regions |

| Key Advantage | Strong discriminatory power for species; potential for quantitative community analysis [16] | Universal primers allow detection of diverse, unexpected pathogens [3] |

| Key Limitation | Poor resolution for some protist parasites; database gaps for some taxa [16] [18] | Variable copy number can bias abundance estimates; primer choice influences results [14] [19] |

| Ideal Use Case | Identifying helminths, arthropod vectors, and zoonotic parasites [17] | Comprehensive screening for protozoan, fungal, and metazoan parasites [14] [20] |

The variable regions of the 18S rRNA gene, such as V4 and V9, are most commonly targeted for high-throughput sequencing. However, the choice of region can significantly impact the results. One study on tick-borne protists found that the number and abundance of protists detected differed depending on whether the V4 or V9 primer sets were used [14]. Another study on gastrointestinal parasites in birds showed that the V4 and V9 regions provided complementary, non-overlapping parasite identifications [20]. For longer, higher-resolution barcodes, the V4–V9 region spanning approximately 1,200 bp can be targeted, which is particularly useful for error-prone sequencing platforms like nanopore [3].

Experimental Protocols

DNA Barcoding Protocol for 18S rRNA (V4 & V9 Regions)

This protocol is adapted from metabarcoding studies investigating parasite diversity in ticks and bird feces [14] [20].

1. DNA Extraction:

- Sample Type: The protocol can be applied to whole ticks, host feces, or other tissues.

- Kit: Use commercial kits such as the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) or QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen), following the manufacturer's instructions.

- Storage: Extract DNA promptly and store at -20 °C.

2. Library Preparation for Illumina MiSeq:

- Normalization: Mitigate amplification bias by normalizing DNA concentrations across samples using a fluorescence-based quantification assay (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit).

- Primary PCR Amplification:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare reactions using Illumina 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library protocols with modifications for 18S rRNA.

- Cycling Conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 3 min

- Amplification: 25 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 s

- Annealing: 55°C for 30 s

- Extension: 72°C for 30 s

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5 min

- Primer Sets:

- V4 Region:

- Forward:

5′-TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGCCAGCAGCCGCGGTAATTCC-3′ - Reverse:

5′-GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGACTTTCGTTCTTGATTAA-3′[14]

- Forward:

- V9 Region:

- Forward:

5′-TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGCCCTGCCHTTTGTACACAC-3′ - Reverse:

5′-GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGCCTTCYGCAGGTTCACCTAC-3′[14]

- Forward:

- V4 Region:

- Purification: Clean the primary PCR product using AMPure beads (Agencourt Bioscience).

- Index PCR & Final Library Construction: Add dual indices and Illumina sequencing adapters using the Nextera XT Index Kit in a second, limited-cycle (e.g., 10 cycles) PCR reaction. Purify the final library again with AMPure beads.

3. Sequencing and Bioinformatics:

- Sequencing Platform: Sequence the library on an Illumina MiSeq platform with paired-end reads.

- Bioinformatic Processing:

- Primer/Adapter Trimming: Use Cutadapt (v3.2) [14] [20].

- Sequence Quality Control & ASV Generation: Process reads with the DADA2 pipeline (v1.18.0) in R to correct errors, merge paired-end reads, remove chimeras, and infer amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) [14] [20].

- Taxonomic Assignment: Assign taxonomy to ASVs using a reference database (e.g., NCBI NT) with a BLAST+ algorithm, applying thresholds such as query coverage >85% and identity >85% [20].

Figure 1: 18S rRNA Metabarcoding Workflow. The process from DNA extraction to taxonomic reporting, highlighting key steps like primer-specific amplification and Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) generation.

Enhanced Protocol for 18S rRNA Barcoding from Blood Samples

Screening blood samples for parasites is challenging due to the high background of host DNA. The following enhancements to the standard 18S rRNA protocol significantly improve sensitivity [3].

1. Primer and Blocking Primer Design:

- Universal Primers: Use primers F566 and 1776R to generate a >1kb amplicon spanning the V4–V9 regions for improved species identification.

- Blocking Primers: Design two host-specific blocking primers to suppress the amplification of human or mammalian 18S rRNA:

- A C3 spacer-modified oligo that competes with the universal reverse primer for host template binding and blocks polymerase elongation.

- A Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA) oligo that tightly binds to the host 18S rRNA target and physically inhibits polymerase progression.

2. PCR with Host DNA Suppression:

- Incorporate the two blocking primers into the primary PCR reaction alongside the universal primers F566 and 1776R.

- This selectively enriches parasite DNA, enabling detection of pathogens like Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense, Plasmodium falciparum, and Babesia bovis from as few as 1-4 parasites/μL of blood [3].

DNA Barcoding Protocol for COI

This protocol is adapted from studies on planktonic foraminifera and deep-sea sediment communities, demonstrating its utility for diverse metazoans [16] [18].

1. DNA Extraction and Specimen Preparation:

- Extract DNA from single specimens or bulk environmental samples using a GITC* or DOC-based extraction buffer, or commercial kits.

- For single organisms, photograph and measure size prior to extraction, as a correlation may exist between cell size/volume and COI copy number in some groups [16].

2. PCR Amplification for Barcoding:

- Primer Set: For a ~1200 bp COI fragment in foraminifera and other taxa, use:

- Forward:

5′-GGATTAATTGGAGGATCAATTGG-3′ - Reverse:

5′-CATAGATWCGTCTAGGAAAACC-3′[16]

- Forward:

- PCR Reaction:

- Mix: 1μL DNA, 0.4μM of each primer, 3% DMSO, 1X HF buffer, 2.5μM MgCl₂, 0.2μM dNTPs, and 0.3 units of DNA polymerase.

- Cycling Conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 98°C for 30 s

- Amplification: 35 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 98°C for 10 s

- Annealing: 65°C for 30 s

- Extension: 72°C for 30 s

- Final Extension: 72°C for 2 min

3. Sequencing and Analysis:

- Sequencing: Purify PCR products and perform Sanger sequencing.

- Phylogenetic Analysis: For species identification, align sequences with references from databases like BOLD and construct a phylogenetic tree (e.g., using Maximum Likelihood method with 500 bootstrap replications in MEGA 11) [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for DNA Barcoding Protocols

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) | DNA extraction from a wide variety of animal tissues and parasites. | DNA isolation from tick pools for 18S rRNA metabarcoding [14]. |

| QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen) | Optimized DNA extraction from complex fecal samples. | Preparation of DNA from great cormorant feces for parasite screening [20]. |

| AMPure Beads (Agencourt Bioscience) | Solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) for PCR product purification. | Cleanup of 18S rRNA amplicons before and after index PCR in Illumina library prep [14] [20]. |

| Nextera XT Index Kit (Illumina) | Provides indexed adapters for multiplexing samples on Illumina sequencers. | Final library construction for 18S rRNA metabarcoding on the MiSeq platform [14]. |

| C3 Spacer-Modified Oligos | Blocking primer that terminates polymerase extension; used for host DNA depletion. | Selective inhibition of human 18S rRNA amplification in blood samples [3]. |

| Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA) Oligos | High-affinity synthetic DNA analog that strongly binds and blocks host DNA amplification. | Suppression of overwhelming host 18S rRNA signals in whole-blood parasite tests [3]. |

| AccuPower HotStart PCR Premix (Bioneer) | Pre-mixed, hot-start PCR reagents for specific and sensitive amplification. | Conventional PCR validation of specific parasite genera (e.g., Histomonas, Isospora) [20]. |

| Butane-1,4-13C2 | Butane-1,4-13C2, CAS:69105-48-2, MF:C4H10, MW:60.11 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Stictic Acid | Stictic Acid, CAS:549-06-4, MF:C19H14O9, MW:386.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The strategic application of COI and 18S rRNA barcoding markers provides a comprehensive framework for advanced research in medical parasitology. COI offers high-resolution species identification critical for studying helminths and arthropod vectors, while 18S rRNA metabarcoding enables unbiased, broad-spectrum detection of eukaryotic parasites in complex samples. The detailed protocols and reagent solutions outlined herein equip researchers with the practical tools to implement these techniques, fostering more accurate parasite identification and ultimately contributing to improved disease diagnosis and drug development. Future efforts should focus on expanding and curating reference databases for both markers to further enhance the accuracy and scope of molecular identification.

For centuries, the identification of parasites has relied on morphological examination through light microscopy. While this method remains a foundational tool for describing new species and providing initial parasite detection, significant limitations have become increasingly apparent in the context of modern medical and veterinary parasitology. These constraints necessitate a paradigm shift towards molecular tools for definitive species identification, particularly in research and drug development. The limitations of traditional methods are not merely inconveniences; they represent critical diagnostic and research bottlenecks that can impede accurate disease understanding, effective control, and drug development [21] [10].

Morphological identification depends on observing anatomical features such as body length, head shape, and sexual organs [21]. However, these characteristics are highly variable among individuals, and many parasite species exhibit nearly identical morphology despite being taxonomically distinct with differing ecological niches, host impacts, and zoonotic potential [21]. Furthermore, the method is time-consuming, requires highly trained taxonomists, and often lacks the resolution to identify parasites to the species level, frequently resulting in classification only to a higher taxonomic group (e.g., genus or family) [21] [10]. This lack of resolution is a major impediment for researchers and drug development professionals who require precise species-level data for studies on pathogenesis, transmission dynamics, and therapeutic efficacy.

Comparative Analysis: Morphological vs. Molecular Identification

The following table summarizes the key limitations of morphological identification and the corresponding advantages offered by molecular tools, such as DNA barcoding and metabarcoding.

Table 1: A comparison of morphological and molecular identification methods for parasites.

| Feature | Morphological Identification | Molecular Identification |

|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Resolution | Poor; often only to genus or family level [21]. | High; enables species-level and even strain-level differentiation [22] [10]. |

| Throughput | Low; time-consuming and labor-intensive [21]. | High; allows for simultaneous identification of multiple species in a single sample (metabarcoding) [21]. |

| Subjectivity | High; relies on observer skill and experience. | Low; provides objective, sequence-based data [22]. |

| Handling of Cryptic Species | Limited or unable to distinguish morphologically identical species [17]. | Highly effective; reveals genetic differences between morphologically similar species [17]. |

| Quantification of Abundance | Possible through egg or parasite counts, but may not be reliable. | Sequence read counts from metabarcoding may not directly correlate with parasite burden [21]. |

| Expertise Required | Skilled taxonomist. | Bioinformatician and molecular biologist [21]. |

| Cost and Infrastructure | Lower initial cost (microscope); but high labor cost. | Higher cost for sequencing platforms and computational resources [21]. |

| Application in Spurious Parasitism | Difficult or impossible to determine if eggs are from a true infection or from a spurious passage [10]. | Can definitively identify the parasite species, confirming or ruling out spurious parasitism [10]. |

Case Studies Highlighting Morphological Limitations

The theoretical limitations of morphological identification manifest in concrete diagnostic challenges. The following examples illustrate critical scenarios where molecular tools are imperative for accurate species identification.

Table 2: Specific parasitic diseases where molecular tools are essential for accurate diagnosis and research.

| Parasite Group / Scenario | Morphological Limitation | Molecular Solution and Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Giardia duodenalis [10] | Cysts are morphologically identical across assemblages, yet assemblages A (zoonotic) and F (cat-specific) have different public health implications. | Universal PCR (e.g., targeting β-giardin locus) differentiates assemblages, enabling accurate zoonotic risk assessment [10]. |

| Toxocara cati Complex [17] | Traditional taxonomy does not distinguish between populations from different felid hosts. | DNA barcoding (cox1 gene) revealed substantial genetic differences (6.68–10.84%) between T. cati from domestic vs. wild cats, suggesting a potential species complex [17]. |

| Taeniid Tapeworms (e.g., Echinococcus spp.) [10] | Eggs of the highly zoonotic Echinococcus multilocularis are indistinguishable from those of other Taeniidae species. | Species-specific PCR (e.g., targeting NADH dehydrogenase gene) provides 100% specific detection of E. multilocularis, crucial for public health response [10]. |

| Cryptosporidium spp. [10] | Over 26 valid species have morphologically indistinguishable oocysts. Dogs can host C. canis and/or zoonotic C. parvum. | Universal PCR (e.g., 18S gene) provides species-level resolution, essential for understanding transmission and zoonotic risk [10]. |

| Spurious Parasitism in Dogs [10] | Strongyle-type eggs from dog hookworm (Ancylostoma caninum) are indistinguishable from those of cat hookworm (A. tubaeforme) passed after coprophagy. | Universal PCR (e.g., ITS-1/ITS-2 markers) identifies the true parasite species, preventing unnecessary treatment of the dog [10]. |

Molecular Workflows and Protocols

To address the limitations of morphology, standardized molecular workflows have been developed. The two primary approaches are DNA barcoding (for individual specimens) and DNA metabarcoding (for complex community analysis).

DNA Barcoding for Single-Specimen Identification

DNA barcoding uses a short, standardized genetic marker to identify an organism to the species level. The standard workflow is as follows [22] [10]:

Protocol: DNA Barcoding via Universal PCR and Sanger Sequencing

Principle: This method amplifies a "variable region" of DNA (unique to each species) that is flanked by "conserved regions" (identical across related species). Universal primers bind to the conserved regions to amplify the variable region, which is then sequenced and compared to reference databases for identification.

Applications: Definitive identification of a single parasite species from an isolated specimen (e.g., an adult worm, a group of eggs) when morphological identification is inconclusive [10].

Materials & Reagents:

- Sample: Genomic DNA extracted from a parasite specimen.

- Primers: Universal primers targeting conserved regions of a standard barcode gene (see Table 3).

- PCR Reagents: Thermostable DNA polymerase (e.g., Taq polymerase), dNTPs, PCR buffer, MgClâ‚‚.

- Equipment: Thermal cycler, agarose gel electrophoresis system, Sanger sequencer.

- Bioinformatics: Sequence analysis software (e.g., BLAST, MEGA).

Procedure:

- DNA Extraction: Isolate genomic DNA from the parasite sample using a commercial kit or standard phenol-chloroform protocol. Quantify DNA concentration and quality.

- PCR Amplification:

- Set up a reaction mix containing: template DNA, forward and reverse universal primers, dNTPs, DNA polymerase, and reaction buffer.

- Run in a thermal cycler with the following typical profile:

- Initial Denaturation: 94°C for 3-5 minutes.

- 35-45 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 94°C for 30 seconds.

- Annealing: 50-65°C (primer-specific) for 30 seconds.

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kb.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes.

- Amplicon Verification: Analyze the PCR product by agarose gel electrophoresis to confirm the presence of a single band of the expected size.

- Sequencing: Purify the PCR product and submit it for Sanger sequencing in both directions using the same primers.

- Data Analysis:

- Assemble the forward and reverse sequence reads into a consensus sequence.

- Perform a BLAST search (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) against a public nucleotide database (e.g., GenBank) to find the closest matching sequences.

- For phylogenetic analysis, align the sequence with reference sequences from confirmed species and construct a phylogenetic tree.

DNA Metabarcoding for Parasite Community Analysis

DNA metabarcoding extends the barcoding principle to identify multiple species from a single bulk sample (e.g., feces, intestinal content) simultaneously [21].

Protocol: DNA Metabarcoding for Gastrointestinal Helminth Communities

Principle: This method uses high-throughput sequencing (HTS) to read the DNA barcodes of all parasites present in a complex sample. Sample-specific index tags are added to the PCR amplicons, allowing many samples to be pooled and sequenced in a single run.

Applications: High-resolution assessment of complete parasite communities in a host or environmental sample, discovery of cryptic species, and monitoring co-infections [21].

Materials & Reagents:

- Sample: Total genomic DNA extracted from feces or intestinal content.

- Primers: Universal barcoding primers with overhang adapters for the HTS platform.

- PCR Reagents: High-fidelity DNA polymerase, dNTPs, PCR buffer.

- Indexing Reagents: Dual index primers (e.g., Nextera XT indices).

- Equipment: Thermal cycler, magnetic bead-based purification system, HTS platform (e.g., Illumina MiSeq).

- Bioinformatics: Requires specialized pipelines (e.g., QIIME 2, DADA2, MOTHUR) for demultiplexing, quality filtering, clustering into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs), or Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs), and taxonomic assignment.

Procedure:

- DNA Extraction: Extract total genomic DNA from the sample. The extraction method should be optimized for breaking down tough parasite structures (e.g., helminth eggs) and removing PCR inhibitors common in fecal samples.

- Primary PCR (Amplification with Adapters):

- Perform the first PCR using universal barcode primers that have platform-specific adapter overhangs.

- Use a high-fidelity polymerase to minimize amplification errors.

- The number of PCR cycles should be minimized to reduce bias.

- PCR Clean-up: Purify the primary PCR amplicons using magnetic beads to remove primers, dNTPs, and enzyme.

- Indexing PCR (Adding Sample Barcodes):

- Use a second, limited-cycle PCR to attach unique dual index sequences to the amplicons from each sample. This step allows samples to be mixed (multiplexed) for sequencing.

- Library Pooling and Purification: Quantify the indexed libraries, mix them in equimolar ratios, and purify the final pooled library.

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Sequence the pooled library on an appropriate HTS platform (e.g., Illumina MiSeq for community analysis).

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Demultiplexing: Assign sequences to samples based on their unique index combinations.

- Quality Filtering & Denoising: Remove low-quality sequences and correct sequencing errors to generate exact ASVs.

- Taxonomic Assignment: Compare ASVs to a curated reference database (e.g., NCBI, Silva) to assign taxonomic identities.

- Data Normalization: Normalize sequence counts across samples for downstream ecological analyses (e.g., alpha and beta diversity).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of molecular parasitology requires specific reagents and tools. The following table details key components of the research toolkit.

Table 3: Essential reagents and materials for molecular identification of parasites.

| Item | Function/Description | Examples / Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Primer Sets | Short oligonucleotides that bind to conserved DNA regions to amplify variable barcode genes from a wide range of parasites. | COI (cytochrome c oxidase I): Standard for metazoans [21] [22]. 18S rRNA: Used for protists and some helminths; highly conserved but contains variable regions [10]. ITS (Internal Transcribed Spacer): High variation useful for species-level discrimination in fungi and some parasites [22] [10]. |

| DNA Extraction Kit | To isolate high-quality, inhibitor-free genomic DNA from diverse sample types (feces, tissue, fixed specimens). | Kits optimized for stool samples (e.g., QIAamp PowerFecal Pro) often include bead-beating steps to break tough cell walls of helminth eggs and cysts. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | For PCR amplification with very low error rates, critical for generating accurate sequence data for barcoding and metabarcoding. | Enzymes like Pfu or proprietary mixes (e.g., Q5 Hot Start, Platinum SuperFi II). |

| Reference Sequence Database | Curated collections of validated DNA barcode sequences for taxonomic assignment of unknown sequences. | NCBI GenBank: Comprehensive but requires careful curation due to potential misidentifications. BOLD (Barcode of Life Data System): A dedicated barcode database with stricter quality control [22]. |

| Bioinformatics Pipeline | A suite of software tools for processing raw sequencing data into biological insights. | QIIME 2: A powerful, user-friendly platform for microbiome (including parasite) metabarcoding analysis. DADA2: A pipeline within R that resolves exact ASVs from sequencing data, providing higher resolution than OTU clustering. |

| Deuteromethanol | Deuteromethanol (CD3OD) | |

| Monostearyl maleate | Monostearyl Fumarate|1741-93-1|Research Chemicals | Monostearyl Fumarate (CAS 1741-93-1) is a high-purity fumaric acid ester for pharmaceutical research. This product is for Research Use Only and not for human or veterinary use. |

The limitations of morphological identification—including poor taxonomic resolution, subjectivity, and an inability to detect cryptic species—are no longer mere academic concerns. They represent significant barriers to progress in medical parasitology research, accurate diagnosis, and the development of targeted therapies. Molecular tools, particularly DNA barcoding and metabarcoding, provide the necessary precision, objectivity, and high-throughput capacity to overcome these barriers. The adoption of these molecular protocols is, therefore, not just an enhancement but an imperative for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to achieve a deeper, more accurate understanding of parasite biodiversity, host-parasite interactions, and disease epidemiology. As reference libraries continue to expand and sequencing technologies become more accessible, the integration of molecular data will undoubtedly become the gold standard in parasitology.

Accurate parasite identification is a cornerstone of effective disease control, yet traditional methods often lack the resolution to distinguish between closely related species or detect co-infections. DNA barcoding has emerged as a powerful solution, but its reliability is entirely dependent on the quality and comprehensiveness of the reference libraries against which unknown sequences are compared. This application note, framed within a broader thesis on DNA barcoding for medical parasite identification, details the experimental protocols and reagent solutions necessary for constructing robust reference libraries. We focus on practical methodologies that enable researchers to achieve species-level resolution, crucial for diagnostics, surveillance, and drug development.

The Critical Role of Reference Libraries in Pathogen Identification

Reference libraries are curated databases of DNA sequences from authoritatively identified specimens. They serve as the definitive standard for comparing and identifying unknown samples in clinical, environmental, or veterinary specimens. The power of any DNA barcoding assay is constrained by the depth and quality of its underlying reference data.

The Challenge of Species-Level Resolution

Traditional microscopic examination, while affordable and rapid, often fails to provide accurate species-level identification and can miss co-infections [3]. For example, the monkey malaria parasite Plasmodium knowlesi was historically misidentified as P. malariae in microscopic diagnoses, an error that was only corrected through molecular analysis [3]. Such misidentifications can have significant implications for treatment and disease management. Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) approaches overcome these limitations but require extensive, validated reference sequences to correctly assign species from genetic data.

Impact of Library Completeness

The effectiveness of DNA barcoding is directly proportional to the completeness of the reference library. Studies on sand flies have demonstrated that DNA barcoding can correctly associate isomorphic females with morphologically identified males and reveal cryptic species diversity within populations [4]. Without comprehensive reference sequences that encompass this intraspecific variation, such as the cryptic diversity detected within Psychodopygus panamensis and Micropygomyia cayennensis cayennensis, accurate identification is impossible [4].

Experimental Protocol for Library Construction

This section provides a detailed protocol for building a reference library for blood parasites using a targeted NGS approach with a portable nanopore platform, based on a recently published methodology [3].

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for constructing a DNA barcode reference library, from sample collection to data integration.

Step-by-Step Methodology

Primer Design and Selection

- Objective: Amplify a diagnostic gene region that provides sufficient genetic variation for species-level identification across a broad taxonomic range.

- Procedure:

- Target Gene Selection: The 18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene is a superior marker for eukaryotic parasites due to its conserved regions, which allow for universal primer binding, and variable regions, which provide species-diagnostic signatures [3] [23].

- Region Selection: For enhanced resolution, target the ~1,200 base pair (bp) fragment spanning the V4 to V9 variable regions of the 18S rRNA gene. This longer barcode outperforms shorter fragments (e.g., V9 alone) in classifying error-prone sequences from nanopore sequencers [3].

- Primer Sequences: Use the universal eukaryotic primers:

- Forward Primer (F566): 5′-Sequence-3′

- Reverse Primer (1776R): 5′-Sequence-3′ These primers cover a wide range of blood parasites, including Apicomplexa (e.g., Plasmodium, Babesia) and Euglenozoa (e.g., Trypanosoma) [3].

Host DNA Suppression

- Challenge: Host (e.g., human or cattle) DNA in blood samples can overwhelm the PCR, drastically reducing the sensitivity for parasite DNA.

- Solution: Implement a dual-blocking primer strategy to selectively inhibit host 18S rDNA amplification [3].

- C3 Spacer-Modified Oligo: A blocking primer (e.g., 3SpC3_Hs1829R) is designed to overlap with the universal reverse primer's binding site on the host DNA. The C3 spacer at the 3′ end permanently blocks polymerase elongation [3].

- Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA) Oligo: A PNA oligo is designed to bind to a host-specific sequence. PNA binds more strongly to DNA than conventional primers, physically obstructing the polymerase and preventing amplification [3].

- PCR Setup: Include both blocking primers in the amplification reaction alongside the universal primers F566 and 1776R.

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- PCR Amplification: Perform PCR using the primer and blocking oligo mix on extracted DNA from blood samples.

- Library Construction: Prepare the amplified DNA for sequencing using a ligation sequencing kit (e.g., Oxford Nanopore's LSK-114 kit).

- Sequencing: Load the library onto a nanopore flow cell (e.g., R10.4.1 or FLO-MIN114) and initiate sequencing on a portable GridION or MinION device. The real-time data stream allows for immediate analysis.

Bioinformatic Analysis and Curation

- Basecalling and Demultiplexing: Convert raw electrical signal data into nucleotide sequences (FASTQ files) using Guppy or Dorado. Demultiplex samples if pooled.

- Read Filtering and Alignment: Filter reads by quality (e.g., Q-score >7) and align them to a custom database of 18S rRNA sequences using minimap2.

- Variant Calling and Consensus Building: Identify single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and generate a high-accuracy consensus sequence for each sample.

- Data Curation and Submission:

- Taxonomic Annotation: Assign species-level taxonomy to each consensus sequence using authoritative databases like the NCBI Taxonomy database.

- Metadata Association: Adhere to the Barcode Core Data Model (BCDM), which standardizes crucial metadata such as specimen collection details, geographical location, and taxonomic information [24].

- Data Deposition: Submit the final, curated sequence records with full metadata to public repositories such as the Barcode of Life Data System (BOLD) and NCBI GenBank [24] [4].

Data Presentation and Performance

The established protocol demonstrates high sensitivity and specificity for detecting medically important parasites.

Analytical Sensitivity

The assay can detect parasites at very low densities, as validated by spiking experiments in human blood [3].

Table 1: Detection Sensitivity for Key Blood Parasites

| Parasite Species | Detection Limit (parasites/μL) |

|---|---|

| Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense | 1 |

| Plasmodium falciparum | 4 |

| Babesia bovis | 4 |

Comparison of DNA Barcode Markers

Different genetic markers offer varying levels of resolution and are suited to different applications.

Table 2: Key Genetic Markers for Parasite DNA Barcoding

| Marker Gene | Organism Group | Amplicon Length | Key Strengths | Reported Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18S rRNA (V4-V9) | Broad-range Eukaryotes | ~1,200 bp | High species-level resolution; suitable for nanopore sequencing | Blood parasite ID (Apicomplexa, Trypanosomatida) [3] |

| Cytochrome c Oxidase I (COI) | Insects, some Parasites | ~658 bp | Standard for animal barcoding; high discrimination power | Sand fly species ID and cryptic diversity detection [4] |

| Mitochondrial Genome | Plasmodium spp. | ~6 kbp | High copy number; species and geographical markers | Speciation and geographical sourcing in malaria [25] |

Application in Research and Drug Development

Robust reference libraries directly empower critical research and development activities.

- Detection of Co-infections and Novel Pathogens: Unlike specific PCR tests, this universal approach can reveal complex infection states. The protocol successfully identified multiple Theileria species co-infecting the same cattle, a scenario easily missed by targeted assays [3]. Its comprehensive nature also allows for the detection of unrecognized or novel parasites.

- Geographical Sourcing and Surveillance: Tools like Malaria-Profiler leverage reference libraries containing geographically informative SNPs to predict the regional source of Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax, and P. knowlesi isolates with high accuracy ( >94%) [25]. This is vital for tracking imported cases and understanding local transmission dynamics.

- Antimalarial Resistance Profiling: The same sequencing data used for identification can be mined for resistance markers. Malaria-Profiler rapidly profiles resistance to chloroquine, sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP), and artemisinin directly from Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) data, providing a comprehensive view of resistance prevalence [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions for implementing the described protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for DNA Barcoding Library Construction

| Item | Function/Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Universal 18S rDNA Primers | Amplify target barcode region from diverse eukaryotes. | F566 & 1776R primers [3] |

| Host-Blocking Oligos | Suppress amplification of overwhelming host DNA to enrich parasite signal. | C3 spacer-modified oligo; PNA oligo [3] |

| High-Fidelity Polymerase | Accurate amplification of long DNA fragments with low error rates. | Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase |

| Nanopore Sequencing Kit | Prepares amplified DNA for sequencing on portable devices. | Ligation Sequencing Kit (SQK-LSK114) |

| Portable Sequencer | Enables real-time, in-field sequencing of barcode amplicons. | Oxford Nanopore MinION/GridION [3] |

| Bioinformatic Tools | For basecalling, read alignment, variant calling, and phylogenetic analysis. | Guppy, minimap2, Malaria-Profiler [25] |

| Dibromoethylbenzene | Dibromoethylbenzene, CAS:30812-87-4, MF:C8H8Br2, MW:263.96 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Trifluoromethanamine | Trifluoromethanamine|CAS 61165-75-1|RUO |

Building comprehensive and meticulously curated DNA barcode reference libraries is not a mere preliminary task but a fundamental research activity that underpins reliable parasite identification. The integrated protocol outlined here—combining optimized wet-lab methods with host depletion strategies, portable sequencing, and standardized bioinformatic curation—provides a robust framework for researchers to enhance these critical resources. As these libraries grow in depth and taxonomic coverage, they will continue to revolutionize our ability to diagnose complex infections, track emerging resistance, monitor disease transmission, and ultimately support the development of new interventions against parasitic diseases.

From Theory to Practice: High-Throughput Applications in Disease Diagnosis and Surveillance

Intestinal parasite infections represent a significant global public health challenge, disproportionately affecting marginalized communities with limited access to clean water and sanitation facilities [26]. Traditional diagnostic methods, including microscopic examination and targeted PCR, have limitations in comprehensive parasite screening due to their time-consuming nature, requirement for specialized expertise, and inability to detect multiple parasite species simultaneously [26]. The advancement of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies has opened new avenues for rapid and accurate screening of complex parasite communities through metabarcoding approaches [26] [27].

This Application Note provides a detailed workflow for implementing 18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene metabarcoding for the simultaneous detection and identification of diverse intestinal parasites. The protocol is framed within the broader context of advancing medical parasite identification research, offering researchers and drug development professionals a standardized methodology that enhances diagnostic accuracy and supports public health efforts to control and prevent intestinal parasitic infections [26].

Key Principles of Parasite Metabarcoding

Metabarcoding combines DNA barcoding with high-throughput sequencing to identify multiple species from a single sample. This approach utilizes short, variable genomic regions that serve as species identifiers, amplified using broad-range primers that target conserved regions flanking these variable segments [28]. For intestinal parasites, the 18S rRNA gene has emerged as a particularly valuable target due to its presence in all eukaryotes and its mosaic of conserved and variable regions [26] [27].

Unlike single-species detection methods, metabarcoding enables comprehensive parasite community profiling without prior assumptions about species presence [27]. This is particularly valuable for detecting low-abundance infections, identifying cryptic species, and discovering unexpected parasites. However, the technique requires careful optimization of each step—from primer selection to bioinformatic analysis—to ensure accurate representation of the parasite community [28].

A critical limitation of metabarcoding is that no single "universal" metabarcoding locus can provide species resolution across the entire tree of life [28]. Different loci are better suited for some taxa than others, requiring strategic selection of barcoding regions based on target organisms. Additionally, factors such as primer bias, DNA extraction efficiency, and template competition during PCR can influence results, necessitating rigorous validation and benchmarking of each metabarcoding assay [28].

Experimental Workflow

The following section outlines a standardized workflow for intestinal parasite metabarcoding, from sample preparation to data analysis, incorporating optimized protocols from recent studies.

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction

Proper sample preparation is crucial for successful metabarcoding. For fecal samples, enrichment protocols can enhance parasite detection:

Sample Enrichment: Pooled fecal samples can be enriched by sucrose flotation. Homogenize pooled samples in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), filter through a 0.1-mm mesh to remove large debris, and layer onto sucrose solution (∼2.4 M in ddH₂O; specific gravity 1.30–1.35). Centrifuge at 1000 × g for 10 min, then carefully transfer materials at the PBS/sucrose interface to new tubes [27].

DNA Extraction: Use commercial DNA extraction kits such as the Fast DNA SPIN Kit for Soil or QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit according to manufacturer protocols. Include mechanical disruption steps: subject samples to freeze-thaw cycles (liquid nitrogen and 37°C water bath) to rupture oocyst walls, then mix with stainless steel beads and process in a tissue homogenizer at 30 Hz for 2 min [26] [27] [20]. Evaluate DNA concentration and purity by measuring the 260/280 nm absorbance ratio.

Plasmid Controls (Optional): For method validation, cloned plasmids of target parasite 18S rDNA regions can be used as positive controls. Linearize circular plasmids using restriction enzymes (e.g., NcoI at 10 U/μL) to minimize steric hindrance during amplification [26].

Primer Selection and Library Preparation

Careful primer selection is fundamental to successful metabarcoding. The table below compares effective primer sets targeting different regions of the 18S rRNA gene:

Table 1: Primer Sets for 18S rRNA Metabarcoding of Intestinal Parasites

| Target Region | Primer Name | Sequence (5'→3') | Amplicon Size | Key Applications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V9 | 1391F | TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAG GTACACACCGCCCGTC | ~130 bp | Broad eukaryote detection, including intestinal parasites | [26] |

| V9 | EukBR | GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAG TGATCCTTCTGCAGGTTCACCTAC | ~130 bp | Broad eukaryote detection, including intestinal parasites | [26] |

| V4-V5 | 616*F | TTAAARVGYTCGTAGTYG | ~509 bp | Detection of Cryptosporidium and other protists | [27] |

| V4-V5 | 1132R | CCGTCAATTHCTTYAART | ~509 bp | Detection of Cryptosporidium and other protists | [27] |

| V4 | 18S V4F | CCAGCAGCCGCGGTAATTCC | Variable | Eukaryote community analysis | [20] |

| V4 | 18S V4R | ACTTTCGTTCTTGATTAA | Variable | Eukaryote community analysis | [20] |

| V9 | 1380F | CCCTGCCHTTTGTACACAC | Variable | Eukaryote community analysis | [20] |

| V9 | 1510R | CCTTCYGCAGGTTCACCTAC | Variable | Eukaryote community analysis | [20] |

PCR Amplification Protocol:

Set up reactions using KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix with primers and 3 μL of template DNA. Use the following cycling conditions [26]:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 5 min

- 30 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 98°C for 30 s

- Annealing: 55°C for 30 s (optimize temperature based on primer set)

- Extension: 72°C for 30 s

- Final extension: 72°C for 5 min

To evaluate the effect of annealing temperature on amplification efficiency, test various temperatures ranging from 40°C to 70°C in 3°C increments [26]. After amplification, perform a limited-cycle (8-cycle) amplification to add multiplexing indices and Illumina sequencing adapters. Purify amplified libraries using AMPure beads and quantify using qPCR according to the qPCR Quantification Protocol Guide [20].

Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis

Sequence purified libraries on Illumina platforms (e.g., iSeq 100 or MiSeq) using appropriate reagent kits [26] [20]. The following workflow outlines the bioinformatic processing steps:

Bioinformatic Processing Steps:

Demultiplexing and Quality Filtering: Process raw sequencing reads using Cutadapt to remove adapter and primer sequences [26] [20]. Trim forward and reverse reads to 250 bp and 200 bp, respectively, to eliminate low-quality bases.

Sequence Denoising and ASV Generation: Use DADA2 for error correction, merging, denoising, and dereplication to generate amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) [26] [20]. Remove chimeric sequences using the consensus method implemented in the removeBimeraDenovo function within DADA2.

Taxonomic Assignment: Classify ASVs taxonomically using QIIME or QIIME2 against comprehensive reference databases [26] [27]. The NCBI nucleotide database or SILVA database can be used, as they encompass a broad range of parasite sequences [26] [27]. Apply filtering thresholds (e.g., query coverage >85% and identity >85%) to ensure accurate taxonomic assignments [20].

Data Analysis: Remove unassigned reads and analyze the final feature table to determine parasite composition. For pooled samples, estimate true prevalences using binomial models with profile-likelihood confidence intervals [27].

Expected Results and Data Interpretation

When properly optimized, 18S rRNA metabarcoding can simultaneously detect numerous parasite species from a single sample. The table below illustrates representative data from a metabarcoding study detecting 11 intestinal parasite species:

Table 2: Example Read Distribution in 18S rDNA V9 Metabarcoding of Intestinal Parasites

| Parasite Species | Read Count Ratio (%) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Clonorchis sinensis | 17.2 | Highest detection efficiency |

| Entamoeba histolytica | 16.7 | Important human pathogen |

| Dibothriocephalus latus | 14.4 | Cestode species |

| Trichuris trichiura | 10.8 | Soil-transmitted helminth |

| Fasciola hepatica | 8.7 | Trematode species |

| Necator americanus | 8.5 | Soil-transmitted helminth |

| Paragonimus westermani | 8.5 | Lung fluke (intestinal stage) |

| Taenia saginata | 7.1 | Beef tapeworm |

| Giardia intestinalis | 5.0 | Important human pathogen |

| Ascaris lumbricoides | 1.7 | Soil-transmitted helminth |

| Enterobius vermicularis | 0.9 | Lowest detection efficiency |

Variations in read count ratios reflect both biological factors (e.g., parasite load) and technical factors (e.g., amplification efficiency). Studies have found that DNA secondary structures show a negative association with the number of output reads, potentially explaining some of the variation in detection efficiency between species [26].

Metabarcoding can detect parasites at low prevalence rates. In clinical applications, this approach has identified Cryptosporidium parvum at an estimated prevalence of 2.14% (95% CI: 0.92–4.10) and Blastocystis hominis at 1.48% (95% CI: 0.53–3.17) in patient populations [27]. The technique also detects unexpected parasites, such as Opisthorchiidae liver flukes in hospital patients, highlighting its value for comprehensive screening [27].

Technical Considerations and Optimization

Methodological Challenges

Several technical challenges require consideration when implementing parasite metabarcoding:

Primer Bias: Different primer sets can yield substantially different results. In one study, only 1.65% of quality-filtered reads mapped to parasites, with fungal reads dominating (98.35%) due to primer bias [27]. Using multiple primer sets targeting different regions can provide more comprehensive coverage.

Amplification Conditions: The annealing temperature during amplicon PCR significantly affects the relative abundance of output reads for each parasite [26]. Optimization of PCR conditions is essential for representative species detection.

Reference Databases: Incomplete reference databases can limit taxonomic assignment accuracy. For blackflies, DNA barcoding identification based on the best close match approach was unsuccessful due to insufficient sequences in GenBank [29]. Developing customized, curated databases for target parasites improves identification accuracy.

Validation and Quality Control

Method Validation: Confirm metabarcoding results with complementary methods such as conventional PCR, nested PCR, gp60 subtyping, and immunofluorescence assays [27]. Microscopic examination provides additional validation, though it may not achieve species-level identification for all parasites [20].

Controls: Include reagent negative controls (extraction blanks) processed alongside samples to monitor potential contamination during DNA extraction and library preparation [27].

Data Quality Assessment: Apply rigorous decontamination pipelines and site occupancy modeling to distinguish signal from noise in eDNA sequence data [28]. This is particularly important for detecting low-abundance species.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Parasite Metabarcoding

| Category | Item | Specification/Example | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | Fecal Collection Kit | Sterile containers, swabs | Maintain cold chain during transport |

| DNA Extraction | Commercial Kits | Fast DNA SPIN Kit for Soil, QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit | Include mechanical disruption steps for robust lysis |

| PCR Amplification | Polymerase | KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix | High-fidelity enzyme for accurate amplification |

| Library Preparation | Index Adapters | Illumina Nextera XT | Dual indexing recommended to reduce cross-contamination |

| Sequencing | Sequencing Kits | Illumina iSeq 100 i1 Reagent | Platform choice depends on required throughput |

| Bioinformatics | Reference Databases | NCBI NT, SILVA, BOLD | Curated custom databases improve taxonomic assignment |

| Validation | Confirmatory Assays | qPCR, nested PCR, microscopy | Essential for validating novel or unexpected findings |

| 3-Aminocrotonic acid | 3-Aminocrotonic acid, CAS:21112-45-8, MF:C4H7NO2, MW:101.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| dorsmanin C | Dorsmanin C|Prenylated Flavonoid|CAS 1025775-95-4 | Dorsmanin C is a prenylated flavonoid from Dorstenia mannii for antioxidant research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

18S rRNA metabarcoding represents a powerful tool for comprehensive screening of intestinal parasites, overcoming limitations of traditional diagnostic methods. This Application Note provides a standardized workflow that researchers can implement to simultaneously detect diverse parasite species in clinical and environmental samples. The protocol's sensitivity and specificity make it particularly valuable for epidemiological surveys, outbreak investigations, and monitoring intervention programs.

While metabarcoding requires careful optimization and validation, its ability to provide comprehensive parasite community profiles positions it as an essential technology for advancing medical parasitology research. As reference databases expand and sequencing costs decrease, this approach is poised to become an increasingly accessible and valuable tool for researchers and public health professionals working to control and prevent intestinal parasitic infections worldwide.

DNA barcoding has emerged as a powerful taxonomic tool to identify and discover species, utilizing one or more standardized short DNA regions for taxon identification [22]. For medical entomology, accurate vector identification is crucial for understanding disease transmission dynamics and implementing effective control measures. This is particularly relevant for dipteran vectors such as Culicoides biting midges and Phlebotomine sand flies, which transmit pathogens causing diseases like leishmaniasis [30] [4].

Traditional morphological identification of these insects faces challenges including phenotypic plasticity, cryptic species complexes, and specimen damage during collection [4] [31]. DNA barcoding addresses these limitations by providing a standardized molecular tool for species discrimination, enabling correct association of isomorphic females with males and revealing hidden diversity [4]. This protocol outlines detailed methodologies for DNA barcoding of Culicoides and sand flies within the context of medical parasitology research.

DNA Barcoding Fundamentals

Principles and Genetic Markers

DNA barcoding relies on analyzing a specific, standardized region of DNA that exhibits sufficient genetic variation to differentiate between species but is flanked by conserved regions that allow universal primer binding [32]. The mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene serves as the standard barcode region for animal identification, including insects [32] [22]. This gene typically shows low intraspecific variation but significant interspecific divergence, creating a "barcode gap" that facilitates species discrimination [4].