Definitive Diagnosis of Parasitic Diseases: From Traditional Methods to Next-Generation Tools for Researchers and Developers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the evolving landscape of parasitic disease diagnostics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Definitive Diagnosis of Parasitic Diseases: From Traditional Methods to Next-Generation Tools for Researchers and Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the evolving landscape of parasitic disease diagnostics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the limitations of conventional techniques and delves into advanced molecular, nanobiosensor, and multi-omics approaches that are enhancing sensitivity and specificity. The content further addresses critical challenges in assay optimization and standardization, while also examining the regulatory frameworks and comparative efficacy of novel tools. The synthesis aims to inform R&D strategy and accelerate the development of next-generation diagnostic solutions for global health.

The Diagnostic Imperative: Understanding the Global Burden and Limitations of Conventional Parasitology

The Global Health and Economic Impact of Parasitic Infections

Parasitic infections constitute a profound and persistent global health challenge, imposing a significant burden on human populations, healthcare systems, and economies worldwide. These infections, caused by diverse organisms including protozoa, helminths, and ectoparasites, are particularly prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions with resource-limited settings and poor sanitation [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than a quarter of the world's population is infected with intestinal parasitic infections alone, resulting in approximately 450 million illnesses annually, with the highest burden occurring among children [2]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of the health and economic impacts of parasitic diseases, framed within the critical context of advanced diagnostic research, which is essential for accurate disease surveillance, effective treatment, and the development of control strategies.

The relationship between parasitic infections and their definitive diagnosis represents a fundamental nexus in global public health. Accurate diagnosis not only guides individual patient management but also enables the precise quantification of disease burden, informs resource allocation, and monitors the effectiveness of intervention programs. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the full scope of the problem is a necessary precursor to innovating solutions. This document synthesizes the most current data on epidemiological reach and economic consequences, while simultaneously detailing the advanced diagnostic methodologies that are reshaping the field of parasitology.

Global Health Burden of Parasitic Infections

Epidemiological Reach and Mortality

The global health impact of parasitic infections is staggering, both in terms of morbidity and mortality. These diseases disproportionally affect the most vulnerable populations, including children, immunocompromised individuals, and those in low- and middle-income countries.

Table 1: Global Burden of Major Parasitic Infections

| Parasite/Disease | Global Prevalence/Incidence | Annual Mortality | Population at Risk | Key Affected Populations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malaria (Plasmodium spp.) | 249 million cases [2] | >600,000 [2] | Nearly half the global population [2] | Children under 5 (account for ~80% of deaths) [2] |

| Soil-Transmitted Helminths | 1.5 billion infected [3] | Not specified (Morbidity focus) | Not specified | Children in endemic areas [3] |

| Schistosomiasis | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Communities with limited access to safe water and sanitation |

| Intestinal Protozoa (e.g., Giardia, Cryptosporidium) | 450 million ill as result of intestinal infections [2] | Not specified | Global, with higher burden in areas of poor sanitation [2] | Children, travelers, immunocompromised individuals [1] |

| Visceral Leishmaniasis | Up to 400,000 new cases annually [2] | ~50,000 (2010 estimate) [2] | >65 countries [2] | Endemic areas of Brazil, India, East Africa, Southern Europe [2] |

Beyond the raw numbers of infection and death, the Disability-Adjusted Life Year (DALY) metric provides a more complete picture of the disease burden by combining years of life lost due to premature mortality and years lived with disability. For example, malaria was responsible for a staggering 46 million DALYs in 2019, reflecting its devastating impact on healthy life [2]. Vector-borne diseases, which include many parasitic illnesses transmitted by mosquitoes, ticks, and other ectoparasites, account for more than 17% of all human infectious diseases globally, causing over 700,000 deaths annually [2].

Morbidity and Co-infections

The morbidity associated with parasitic infections extends across a wide spectrum, from acute, life-threatening illness to chronic conditions that cause long-term disability and impair cognitive and physical development. Helminth infections, for instance, are a leading cause of iron-deficiency anemia, growth retardation, and stunted cognitive development in children [4]. The impact of co-infections with other pathogens presents an additional layer of complexity. A 2025 meta-analysis revealed that the global prevalence of parasitic coinfection in people living with viruses is substantial, estimated at 21.34% for helminths and 34.13% for protozoa in virus-infected individuals [4]. These co-infections can alter immune responses, exacerbate disease severity, and complicate diagnosis and treatment. For instance, HIV infection drives immunocompromise that predisposes individuals to severe opportunistic parasitic infections, while helminth-induced Th2-type immune responses can inhibit Th1-type antiviral defense mechanisms [4].

Economic Impact of Parasitic Diseases

The economic burden of parasitic infections is multifaceted, encompassing direct healthcare costs, indirect costs due to lost productivity, and long-term macroeconomic effects on human capital and national economies.

Direct and Indirect Costs

The direct costs include expenses for diagnosis, treatment, and hospitalization, while indirect costs arise from lost labor productivity due to illness, disability, and premature death. For example, the Parasitic Diseases Therapeutic Market is anticipated to grow from $9.39 billion in 2025 to $19.78 billion by 2033, reflecting the substantial and growing economic activity directed at managing these diseases [5]. This market growth is driven by increasing disease prevalence, advancements in treatment, and heightened awareness.

The economic impact is not limited to human health. Plant-parasitic nematodes, such as root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.), cause massive agricultural losses, estimated at $125 to $350 billion per year in global crop yields [2]. The rice root-knot nematode (M. graminicola) alone is responsible for annual rice yield losses of 15% in Asia, threatening food security [2].

Macroeconomic Burden

The macroeconomic burden, measured by the impact on a country's gross domestic product (GDP), can be profound, particularly in endemic countries. A 2025 study on schistosomiasis estimated its macroeconomic burden in 25 endemic countries at INT$ 49,504 million (uncertainty interval: 48,668–50,339) for the period 2010-2050 [6]. This model considered the impact of mortality and morbidity on labor supply, age and gender differences in education and work experience, and treatment costs on capital accumulation. The burden was inequitably distributed, with Egypt, Brazil, and South Africa bearing the largest absolute economic burdens [6]. This represents a loss equivalent to 0.0174% of the total GDP of these 25 countries, underscoring the long-term economic drag exerted by a single neglected tropical disease.

Table 2: Estimated Macroeconomic Burden of Schistosomiasis in Select Endemic Countries (2025 Study)

| Country | Estimated Economic Burden (International Dollars, Millions) |

|---|---|

| Egypt | 11,400 |

| Brazil | 9,779 |

| South Africa | 6,744 |

| 25 Endemic Countries (Total) | 49,504 |

The Critical Role of Definitive Diagnosis in Mitigating Impact

Limitations of Conventional Diagnostic Methods

Accurate diagnosis is the cornerstone of effective parasitic disease control, yet traditional methods have significant limitations that hinder their effectiveness, particularly in resource-poor settings. Conventional techniques such as microscopy, serological testing, histopathology, and culturing have been the diagnostic mainstay for decades [7]. While often effective, these methods can be time-consuming, require a high level of technical expertise, and have limited sensitivity and specificity, especially in cases of low parasite burden or chronic infection [7] [3]. The reliance on these tools in endemic regions with poor infrastructure and limited access to healthcare facilities has historically led to underdiagnosis and inaccurate burden estimates, thereby impeding effective control and eradication efforts [8].

Advanced Diagnostic Methodologies and Protocols

The field of parasitic disease diagnosis is being revolutionized by technological advancements that offer unprecedented sensitivity, specificity, speed, and field-deployability. These innovations are crucial for generating the precise data needed to truly understand and mitigate the global impact of these infections.

Molecular Diagnostics

Molecular methods have dramatically enhanced the detection and identification of parasites.

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and Its Variants: These techniques amplify and detect parasite-specific DNA sequences, offering high sensitivity and the ability to differentiate between species and strains. Multiplex PCR allows for the simultaneous detection of multiple parasites in a single reaction, which is invaluable for diagnosing co-infections [8]. Digital PCR (dPCR), a newer technology, provides absolute quantification of parasite load without the need for a standard curve, proving useful for monitoring treatment efficacy and detecting low-level infections [8].

- Isothermal Amplification (e.g., LAMP, RPA): Techniques like Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) amplify DNA at a constant temperature, eliminating the need for sophisticated thermal cyclers. This makes them ideal for rapid, field-adjustable tools for use in primary care settings or remote laboratories [7] [8].

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): NGS technologies allow for the comprehensive analysis of parasite genomes, enabling species identification, detection of drug-resistance markers, and investigation of complex parasite populations and transmission dynamics [7] [8].

Immunological and Biomarker-Based Advances

Advanced serological methods have moved beyond basic antibody detection.

- Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs) and Lateral Flow Immunoassays (LFIA): These point-of-care (POC) tests provide results in minutes from a drop of blood, serum, or other samples. They are crucial for rapid screening and management, particularly for diseases like malaria [7] [8].

- Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) and Chemiluminescent Immunoassays (CLIA): These plate-based assays are used for the high-throughput detection of parasite-specific antigens or host antibodies. They are fundamental tools for seroepidemiology studies [8].

- Biomarker Detection: Research is focused on identifying and detecting specific biomarkers, including parasite-specific antigens, host-derived antibodies, cytokines, and metabolites, to distinguish between active and past infections, monitor disease progression, and assess treatment response [7] [8].

Imaging and Artificial Intelligence

Advanced imaging technologies, augmented by artificial intelligence (AI), are increasing the speed and accuracy of diagnosis.

- AI-Based Image Recognition: AI algorithms are being trained to automatically detect and identify parasites in digital images of blood smears, stool samples, and histopathology slides. This can reduce reliance on human expertise, decrease diagnostic time, and improve consistency [3] [8].

- Advanced Staining and Imaging Techniques: Improved staining methods enhance the contrast and visibility of parasites in samples, while advanced imaging systems can automate the scanning of slides, flagging potential parasites for technologist review [8].

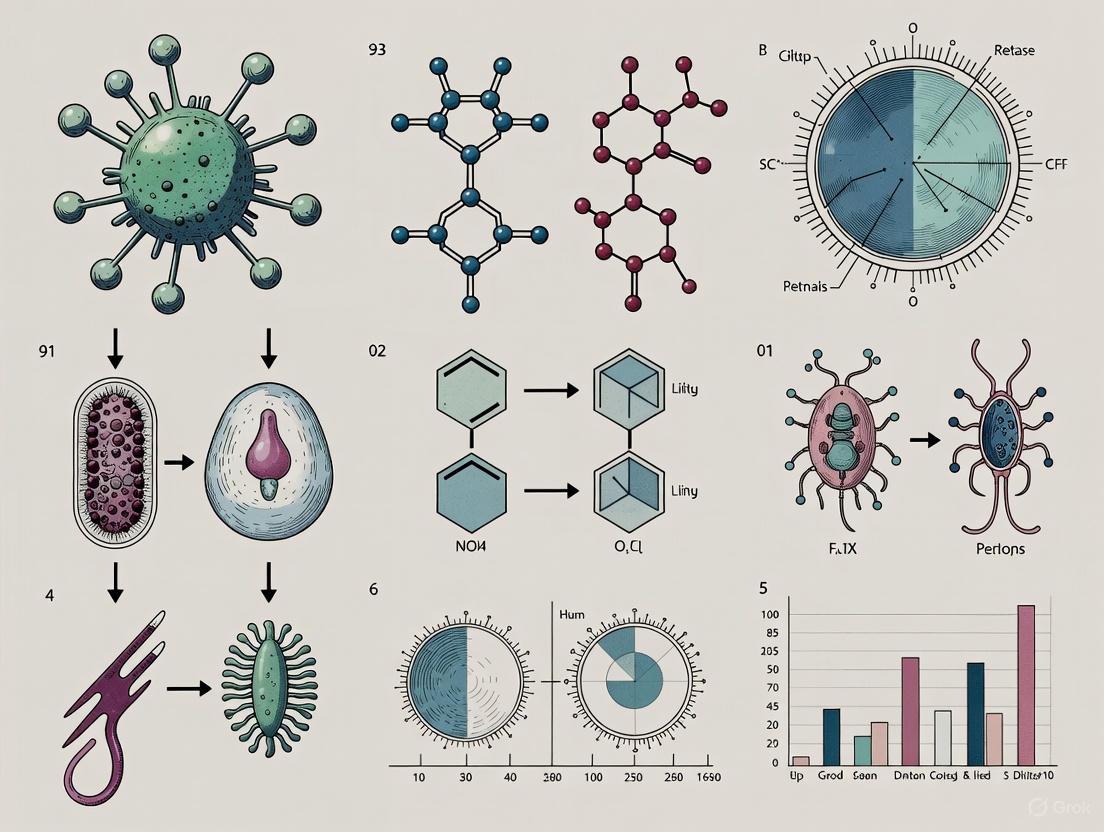

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated application of these modern diagnostic approaches in a research and clinical setting:

Integrated Diagnostic Workflow for Parasitic Infections

CRISPR-Cas and Nanotechnology

The latest innovations are pushing the boundaries of diagnostic sensitivity and portability.

- CRISPR-Cas Diagnostics: This technology utilizes the programmability of CRISPR-Cas systems to detect parasite-specific DNA or RNA sequences with exceptional specificity. It offers the potential for ultra-sensitive, rapid, and field-deployable diagnostic tests [8].

- Nanotechnology: The application of nanoparticles in diagnostics is leading to the development of highly sensitive nano-biosensors. These devices can detect minute quantities of parasite biomarkers (nucleic acids, antigens) and are being integrated into POC platforms for use in low-resource settings [8].

Multi-Omics Integration

A holistic approach integrating data from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics (multi-omics) is providing a comprehensive understanding of parasite biology, host-parasite interactions, and disease mechanisms. This integrated data is invaluable for identifying new therapeutic targets and discovering novel diagnostic biomarkers [7] [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The advancement of diagnostic research and development relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details essential components used in modern parasitology diagnostics.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Parasitic Disease Diagnostics

| Research Reagent / Material | Function and Application in Diagnostics |

|---|---|

| Specific Primers and Probes | Short, synthetic DNA sequences designed to bind to and amplify unique genomic regions of target parasites in PCR, qPCR, and dPCR assays. |

| Recombinant Parasitic Antigens | Purified proteins produced from cloned parasite genes; used as capture/detection targets in immunoassays (ELISA, RDTs) and for assessing host immune responses. |

| Monoclonal and Polyclonal Antibodies | Antibodies raised against specific parasitic antigens; function as critical detection reagents in immunoassays like LFIA, ELISA, and CLIA. |

| CRISPR-Cas Enzymes & Guide RNAs | The core components of CRISPR-based diagnostics; the guide RNA directs the Cas enzyme to a specific parasite DNA/RNA sequence, triggering a detectable signal upon binding. |

| Functionalized Nanoparticles | Gold nanoparticles, magnetic beads, or quantum dots coated with antibodies or DNA probes; used as signal amplifiers or capture agents in biosensors and rapid tests. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Kits | Commercial kits containing all necessary enzymes, buffers, and adapters for preparing parasite DNA/RNA libraries for sequencing on NGS platforms. |

| Cell Culture Media for Parasites | Specialized nutrient media required for in vitro cultivation of certain parasites (e.g., Leishmania, Trypanosoma), essential for antigen production and drug testing. |

| Fenuron-d5 | Fenuron-d5, CAS:1219802-06-8, MF:C9H12N2O, MW:169.239 |

| 1-Octen-3-ol - d3 | 1-Octen-3-ol |

Parasitic infections remain a formidable global challenge, inflicting severe health consequences and imposing a substantial economic burden that stifles development, particularly in endemic regions. The data presented herein underscores the vast epidemiological reach of these diseases, from malaria affecting hundreds of millions to the chronic disability caused by soil-transmitted helminths and schistosomiasis. The economic toll, quantified in billions of dollars of lost productivity and healthcare costs, highlights the urgent need for sustained and increased investment in control and elimination efforts. The path to mitigating this multifaceted impact is inextricably linked to advancements in diagnostic technology. The transition from traditional, often insensitive methods to sophisticated molecular, immunoassay, and nanotechnology-based platforms is revolutionizing the field. These innovations enable definitive diagnosis, accurate species identification, detection of co-infections, and monitoring of drug resistance, which are all critical for effective patient management, precise disease surveillance, and the development of new therapeutics. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of both the scale of the problem and the cutting-edge tools available to address it is paramount. Continued research and development into more sensitive, specific, affordable, and field-deployable diagnostic solutions, integrated within a One Health framework, are essential for achieving lasting progress against parasitic diseases and alleviating their profound impact on global health and economies.

For decades, the diagnosis of parasitic infections has relied fundamentally on a triad of conventional techniques: microscopy, serology, and culture. Despite the emergence of sophisticated molecular methods, these traditional approaches have formed the historical gold standards and continue to serve as the backbone of diagnostic parasitology, particularly in resource-limited settings where the burden of parasitic diseases is highest [9] [10]. These methods are efficient, comparatively cheap, and sometimes still provide information that newer molecular methods cannot replicate [11]. The enduring relevance of these techniques lies in their direct ability to visualize parasites, detect the host's immune response, or isolate the causative organism, thereby providing a definitive diagnosis. However, the diagnostic process is complicated by the fact that many parasitic diseases do not produce characteristic symptoms, requiring not just the detection of a parasite but also the establishment of a causal relationship between its presence and the clinical disease [3] [12]. This in-depth technical guide examines the principles, methodologies, and applications of these cornerstone techniques within the broader context of definitive diagnosis for research and drug development.

Microscopy: The Visual Gold Standard

Principles and Historical Significance

Microscopy represents the oldest and most foundational tool in parasitology. Its inception in the 17th century, pioneered by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, revolutionized the field by enabling the visualization of the microscopic world of parasites [9]. Before its advent, parasitic infections were often misunderstood and misdiagnosed [9]. The core principle of microscopic diagnosis is the direct morphological identification of parasites, their eggs (ova), larvae, or cysts in various clinical specimens. This method remains the gold standard for diagnosing many parasitic infections due to its directness, low cost, and ability to provide a quantitative assessment of parasite burden [10] [13]. Despite its advantages, microscopy requires significant expertise, as the accurate differentiation of parasite species relies on a detailed understanding of morphological characteristics, and its sensitivity can be limited by factors such as parasite load and sample quality [3] [14].

Key Methodologies and Workflows

Microscopic diagnosis encompasses several standardized protocols, tailored to the parasite and the specimen type.

- Direct Wet Mount Examination: Fresh specimens (e.g., stool, blood) are examined under a microscope, often using saline or iodine. This allows for the observation of motile trophozoites (e.g., in amoebiasis), larvae, or cysts [13]. Iodine staining helps visualize nuclear details within cysts.

- Concentration Techniques: Methods like formol-ether sedimentation are used to concentrate parasites from a larger sample volume, thereby increasing the test's sensitivity. This is particularly useful for identifying light infections [13].

- Stained Smears: Thin and thick blood smears are critical for diagnosing blood-borne parasites like Plasmodium species (malaria). The smears are stained with Giemsa or other Romanowsky stains to highlight the parasite's morphology within red blood cells [10]. Similarly, permanent stains (e.g., iron-hematoxylin) are used on stool samples to enhance the visualization of intestinal protozoa [13].

The following workflow outlines a typical diagnostic process for an intestinal parasitic infection using microscopy:

Experimental Protocol: Direct Wet Mount and Concentration for Intestinal Parasites

Objective: To identify cysts, ova, or trophozoites of intestinal parasites in a stool sample.

Materials:

- Fresh stool specimen

- Microscope slides and coverslips

- Normal saline (0.9%)

- Lugol's iodine

- Centrifuge and centrifuge tubes

- Formalin (10%) and ethyl acetate

- Disposable pipettes

Procedure:

- Direct Saline and Iodine Wet Mount:

- Emulsify a small portion of stool (about 2 mg) in a drop of saline on a microscope slide.

- Prepare a second emulsification in a drop of Lugol's iodine on a separate slide.

- Apply coverslips and examine systematically under low (10x) and high (40x) magnification. Use 100x oil immersion for detail if needed.

- Look for motile trophozoites (in saline), cysts, and eggs. Iodine stains glycogen and nuclei.

- Formol-Ether Sedimentation Concentration:

- Suspend 1-2 g of stool in 10 mL of 10% formalin in a centrifuge tube. Mix thoroughly and filter through a sieve.

- Add 3 mL of ethyl acetate to the filtrate. Stopper the tube and shake vigorously.

- Centrifuge at 500 x g for 10 minutes. The debris will form a plug between the formalin and ethyl acetate layers.

- Free the debris plug by ringing it with an applicator stick and carefully decant the supernatant.

- Use a swab or pipette to transfer sediment to a slide for examination as above.

Interpretation: Identify parasites based on characteristic size, shape, and internal structures (e.g., number of nuclei in cysts, appearance of eggshells) [13].

Serology: Detecting the Host's Immune Response

Principles and Diagnostic Value

Serological techniques indirectly detect parasitic infections by measuring the host's humoral immune response (antibodies) or, increasingly, circulating parasite antigens [3] [11]. These methods are indispensable for diagnosing tissue-invasive parasites that are not readily found in stool or blood, such as Echinococcus spp. (hydatid disease) or Toxoplasma gondii [10] [1]. A significant advantage of antigen-detection tests is their ability to confirm active infection, whereas antibody tests can struggle to distinguish between past exposure and current, active disease [9] [10]. Furthermore, cross-reactivity between antigens from related parasite species can sometimes reduce test specificity [9]. Despite these challenges, the high throughput and automation potential of serological assays like ELISA make them a mainstay in clinical laboratories.

Key Methodologies and Workflows

Serodiagnostics have evolved from early complement fixation tests to modern, highly automated immunoassays.

- Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA): This workhorse technique can be configured to detect either antibodies or antigens. It involves immobilizing a capture molecule (antigen for antibody detection, or antibody for antigen detection) on a solid phase. An enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody produces a colorimetric signal proportional to the target's concentration [11] [10]. Variations like the Falcon Assay Screening Test (FAST-ELISA) and Dot-ELISA offer rapid, simpler alternatives [10].

- Immunofluorescence Assay (IFA): Often considered a gold standard in serology, IFA uses fixed whole parasites or antigen substrates on a slide. The patient's serum is applied, and any bound antibody is detected with a fluorochrome-labeled anti-human immunoglobulin, visualized under a fluorescence microscope [10].

- Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs): These are lateral flow immunochromatographic assays that provide results in minutes, making them ideal for point-of-care settings. They are widely used for detecting malaria antigens (Plasmodium histidine-rich protein 2, aldolase) or other parasitic antigens [15] [10].

The decision pathway for employing serological methods is outlined below:

Experimental Protocol: Indirect ELISA for Antibody Detection

Objective: To detect parasite-specific IgG antibodies in a human serum sample.

Materials:

- Microtiter plate coated with purified parasite antigen

- Test and control human serum samples

- Blocking buffer (e.g., PBS with 1% BSA or 5% skim milk)

- Wash buffer (PBS with 0.05% Tween 20)

- Enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase-anti-human IgG)

- Substrate solution (e.g., TMB/Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚)

- Stop solution (e.g., 1M Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„)

- ELISA plate reader

Procedure:

- Blocking: Add blocking buffer to the antigen-coated wells and incubate (e.g., 1 hour at 37°C) to prevent nonspecific binding. Wash the plate three times with wash buffer.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Add diluted test and control sera to the wells. Incubate (e.g., 1 hour at 37°C). Wash thoroughly.

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Add the enzyme-conjugated anti-human IgG at the recommended dilution. Incubate (e.g., 1 hour at 37°C). Wash thoroughly.

- Detection: Add substrate solution to each well. Incubate in the dark for a fixed time (e.g., 15-30 minutes) until color develops.

- Stop Reaction and Read: Add stop solution to terminate the enzyme reaction. Immediately read the absorbance at the appropriate wavelength (e.g., 450 nm for TMB) using a plate reader.

Interpretation: A sample's optical density (OD) is compared to the cutoff value (often determined from negative controls). An OD above the cutoff indicates the presence of specific antibodies [11] [13].

Culture: Isolating the Pathogen

Principles and Applications in Parasitology

While culture is a cornerstone of bacteriology and mycology, its application in diagnostic parasitology is more limited but remains crucial for specific protozoan infections. The principle involves providing the necessary nutrients, temperature, and atmospheric conditions to support the growth and multiplication of parasites in vitro [11]. Culture is highly sensitive for certain parasites like Entamoeba histolytica and Leishmania spp., and it provides a source of organisms for further analysis, such as isoenzyme typing (zymodeme analysis) or drug sensitivity testing [10] [1]. However, culture methods are not available for most helminths, are often labor-intensive, require specialized media, and can take days to weeks to yield results, limiting their routine use [11].

Key Methodologies

- Xenic Culture: This method cultivates the parasite in the presence of an unknown consortium of other microorganisms. Robinson's medium, for example, is used for the xenic culture of Entamoeba histolytica from stool samples.

- Axic Culture: This involves cultivating the parasite in a sterile environment without any other living organisms. This is the standard for Leishmania and Trypanosoma cultures, often using media like NNN (Novy-MacNeal-Nicolle) medium or Schneider's Insect Medium, supplemented with fetal bovine serum.

- Cell Culture: Some parasites, such as Toxoplasma gondii, are efficiently cultivated in mammalian cell monolayers (e.g., human foreskin fibroblasts), which act as a host cell for the intracellular parasite.

Comparative Analysis of Conventional Techniques

The following tables summarize the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of each conventional technique, along with common specimen requirements.

Table 1: Comparison of Conventional Diagnostic Techniques

| Technique | Principle | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopy | Direct morphological identification | Low cost; gold standard for many parasites; quantitative | Low sensitivity in light infections; requires expertise | Routine screening for intestinal/blood parasites [3] [13] |

| Serology | Detection of host antibodies or parasite antigens | High throughput; automatable; good for tissue parasites | Cannot always distinguish active from past infection (antibody tests) | Diagnosing invasive disease (e.g., echinococcosis, toxoplasmosis) [10] [1] |

| Culture | In vitro propagation of parasite | High sensitivity for some protozoa; provides isolate for further study | Not available for most parasites; slow; technically demanding | Confirmation & typing of Entamoeba histolytica, Leishmania [10] [1] |

Table 2: Specimen and Method Selection for Common Parasites

| Parasite | Disease | Primary Specimen(s) | Gold Standard/Common Conventional Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmodium spp. | Malaria | Blood | Microscopy (Giemsa-stained thick & thin smears) [10] |

| Entamoeba histolytica | Amoebiasis | Stool, Liver abscess aspirate | Microscopy (wet mount, stained smears); Culture [13] |

| Giardia lamblia | Giardiasis | Stool, Duodenal contents | Microscopy (wet mount, concentration) [3] [12] |

| Leishmania spp. | Leishmaniasis | Tissue aspirate, Bone marrow | Microscopy (smears); Culture (NNN medium) [10] |

| Echinococcus spp. | Hydatidosis | Serum, Cyst fluid | Serology (ELISA, Immunoblot) [10] |

| Strongyloides stercoralis | Strongyloidiasis | Stool, Serum | Microscopy (larvae identification); Serology (ELISA) [10] [1] |

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Conventional Parasitology

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Giemsa Stain | Stains nuclei (purple) and cytoplasm (blue) of parasites | Differentiation of Plasmodium species in blood smears [10] |

| Formalin (10%) | Preservative; fixes parasites; disinfects | Preservation of stool samples for concentration techniques [13] |

| ELISA Kits (Antigen/Antibody) | High-throughput detection of immune response or parasite markers | Seroprevalence studies; diagnosis of toxoplasmosis, cysticercosis [10] [13] |

| Culture Media (e.g., NNN, Robinson's) | Supports in vitro growth and propagation of parasites | Isolation and maintenance of Leishmania or Entamoeba strains [10] |

| Fluorochrome-Lagged Antibodies | Binds to primary antibody for visual detection | Confirmatory testing in Immunofluorescence Assays (IFA) [10] |

| 5-Chloro-AB-PINACA | 5-Chloro-AB-PINACA|CAS 1801552-02-2|Research Chemical | 5-Chloro-AB-PINACA is a synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonist (SCRA) for pharmacological research only. Not for human or veterinary use. Buy now for your studies. |

| 9-Norketo FK-506 | 9-Norketo FK-506, CAS:123719-19-7, MF:C₄₃H₆₉NO₁₁, MW:776.01 | Chemical Reagent |

Microscopy, serology, and culture have collectively formed the unshakeable foundation of diagnostic parasitology. While the field is rapidly advancing with the integration of molecular diagnostics and artificial intelligence [9] [14], these conventional techniques retain their status as historical gold standards. They continue to be vital for routine diagnosis, epidemiological surveillance, and primary research, especially in regions where parasitic diseases are endemic. A comprehensive diagnostic strategy often involves a synergistic approach, leveraging the strengths of these traditional methods while acknowledging their limitations. For researchers and drug development professionals, a firm grasp of these core techniques is essential for designing robust experiments, validating new diagnostics, and ultimately contributing to the global effort to control and eliminate parasitic diseases.

Parasitic diseases present a profound and persistent global health challenge, affecting hundreds of millions of people worldwide and imposing significant economic burdens, particularly in developing regions [7] [16]. The World Health Organization estimates that nearly one-quarter of the world's population is affected by parasitic infections, with soil-transmitted helminths alone infecting approximately 1 billion people [9] [17]. These infections result in devastating health consequences including malnutrition, anemia, impaired cognitive and physical development in children, and increased susceptibility to other diseases [9]. In the face of this substantial disease burden, accurate and timely diagnosis represents the critical first step toward effective treatment, control, and potential eradication of these complex pathogens.

The diagnostic landscape for parasitic infections has evolved significantly over centuries, yet fundamental limitations continue to hamper effective disease management [9]. Traditional techniques including microscopy, serological assays, histopathology, and culturing have formed the diagnostic backbone for decades [7]. While these methods have provided invaluable service in parasite identification, they suffer from three interconnected critical limitations that undermine their effectiveness: excessive time consumption, profound dependency on specialized expertise, and inadequate sensitivity and specificity [7] [12] [17]. These limitations become particularly problematic in resource-limited settings where parasitic diseases are most prevalent, creating a diagnostic paradox where the regions most burdened by these infections have the least access to reliable diagnostic capabilities [7] [8].

This technical analysis examines the core limitations of conventional parasitic diagnostic methodologies within the broader context of definitive diagnosis research. By quantifying these constraints through experimental data and exploring emerging technological solutions, we provide a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to advance the next generation of diagnostic platforms for parasitic diseases.

Quantitative Analysis of Conventional Diagnostic Limitations

The performance constraints of traditional diagnostic methods can be precisely quantified through experimental data and clinical studies. The following analysis examines the specific limitations related to time efficiency, expertise dependency, and analytical sensitivity/specificity across major diagnostic platforms.

Table 1: Performance Limitations of Conventional Parasite Diagnostic Methods

| Diagnostic Method | Time Requirement | Expertise Dependency | Reported Sensitivity | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kato-Katz Microscopy | 15-30 minutes/sample [17] | High (parasitology expertise required) [12] | 50-62% (1 sample, S. mansoni); 75-85% (hookworm, 3 samples) [17] | Low sensitivity for light infections, day-to-day egg output variation [17] |

| Wet Mount Microscopy | 20-40 minutes/sample [18] | High (morphological differentiation skills) [14] [12] | 89.5% (compared to reference) [18] | Observer-dependent, limited by parasite load [18] |

| Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs) | 10-20 minutes [7] | Low to moderate | Variable; cross-reactivity issues [9] | Limited antigen targets, inability to distinguish active infection [12] |

| ELISA/Serology | 2-4 hours (batch processing) [14] | Moderate (technical training required) | Limited by cross-reactivity [9] | Cannot distinguish past vs. current infection [9] |

Table 2: Impact of Repeated Sampling on Diagnostic Sensitivity

| Number of Stool Samples | S. mansoni Sensitivity (%) | Hookworm Sensitivity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 sample | 50-62% [17] | ~50% [17] |

| 2 samples | ~80% [17] | ~75% [17] |

| 3 samples | Not reported | ~85% [17] |

| 4 samples | Not reported | ~95% [17] |

The data reveal several critical patterns. First, microscopy-based methods exhibit significant time investments per sample, creating processing bottlenecks in high-volume settings [18]. Second, the sensitivity of the widely-used Kato-Katz technique shows strong dependence on both parasite species and sampling effort, with hookworm diagnosis requiring up to four samples to achieve >90% sensitivity [17]. This sampling burden directly impacts time efficiency and compliance in field studies and clinical trials. Third, the expertise requirement for morphological identification remains a substantial barrier to reliable diagnosis, particularly in non-endemic regions where technologist proficiency may be limited [12].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Diagnostic Limitations

Kato-Katz Sensitivity Quantification Protocol

The Kato-Katz technique represents the gold standard for soil-transmitted helminth diagnosis in epidemiological studies, yet its limitations must be systematically quantified for proper interpretation of results [17].

Materials:

- Kato-Katz templates (40-50 mg)

- Cellophane strips soaked in glycerol-malachite green

- Microscope slides

- Light microscope

Procedure:

- Place approximately 100mg of sieved stool sample on the template

- Transfer sample to microscope slide using template

- Cover with glycerol-soaked cellophane strip

- Press gently to create uniform smear

- Allow 30-60 minutes for clearing before examination

- Examine entire smear under microscope at 100x magnification

- Count eggs for each helminth species separately

- Calculate eggs per gram (EPG) using conversion factor based on template volume

Sensitivity Analysis:

- Collect multiple samples over consecutive days (minimum 2, ideally 3-4)

- Apply zero-inflated negative binomial statistical model to account for false negatives

- Calculate sensitivity as function of infection intensity: Sensitivity = 1 - (1 - p)â¿ where p is probability of detection per sample and n is number of samples [17]

Limitations:

- Sensitivity drops significantly at low infection intensities (<100 EPG)

- Day-to-day variation in egg output affects reproducibility

- Species-dependent clearance rates affect visibility

Automated Microscopy Validation Protocol

Automated microscopy systems like SediMAX2 offer potential solutions to expertise dependency in conventional microscopy [18].

Materials:

- SediMAX2 automated microscopy system

- SAF (sodium acetate-acetic acid-formalin) fixative

- Disposable cuvettes

- Centrifuge

Procedure:

- Fix stool samples in SAF fixative

- Concentrate by centrifugation at 500g for 5 minutes

- Dilute sediment with saline solution (1:20)

- Load 20μl into SediMAX2 disposable cuvettes

- System automatically centrifuges, acquires, and stores 60 high-definition images per sample

- Review stored images for parasitic structures

- Compare results with conventional wet mount examination

Validation Metrics:

- Calculate sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV)

- Determine kappa coefficient for inter-method agreement

- Assess time reduction compared to conventional microscopy

Performance Data:

- Reported sensitivity: 89.51%

- Reported specificity: 98.15%

- PPV: 99.22%

- NPV: 77.94%

- Kappa: 0.81 (almost perfect agreement) [18]

Emerging Solutions and Technological Frameworks

Next-generation diagnostic platforms aim to address the critical limitations of conventional methods through technological innovation. The following frameworks visualize the evolving diagnostic landscape and its relationship to the identified constraints.

Diagram 1: Diagnostic evolution addressing core limitations

Diagram 2: Nanobiosensor architecture for parasitic detection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Advanced Parasite Diagnosis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanomaterials | Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), Quantum dots (QDs), Carbon nanotubes (CNTs), Graphene oxide (GO) [14] | Signal amplification in biosensors | AuNPs for PfHRP2 detection; QDs for DNA probe labeling; CNTs functionalized with antibodies [14] |

| CRISPR Components | Cas proteins, gRNA, Reporter molecules [7] [8] | Nucleic acid detection | High specificity for parasite DNA/RNA; portable detection systems [8] |

| Molecular Assay Components | Primers, Probes, Isothermal amplification reagents [7] [8] | PCR, LAMP, multiplex assays | Enhanced sensitivity over microscopy; species differentiation [9] [8] |

| Immunological Reagents | Recombinant antigens, Monoclonal antibodies, ELISA kits [12] | Serodiagnosis, antigen detection | Limited by cross-reactivity; unable to distinguish active infection [9] [12] |

| Automated Imaging Consumables | SediMAX2 cuvettes, SAF fixative [18] | Automated microscopy | 89.5% sensitivity, 98.2% specificity vs. conventional microscopy [18] |

| α-Ergocryptine-d3 | α-Ergocryptine-d3|Deuterated Ergot Alkaloid|CAS 1794783-50-8 | α-Ergocryptine-d3 is a deuterated stable isotope-labeled ergot alkaloid. It serves as a critical internal standard for precise bioanalytical research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| C.I. Acid Yellow 232 | C.I. Acid Yellow 232 | High-purity C.I. Acid Yellow 232 for industrial research. A metal complex dye for wool, leather, and nylon. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

The critical limitations of time consumption, expertise dependency, and inadequate sensitivity/specificity in parasitic disease diagnosis represent both a formidable challenge and a catalyst for innovation. Quantitative analysis reveals that conventional methods suffer from fundamental constraints that impact their utility in both clinical and research settings, particularly in resource-limited regions where parasitic diseases are most prevalent [17] [18]. The experimental protocols detailed herein provide frameworks for systematically evaluating these limitations and validating potential solutions.

Emerging technological platforms including nanobiosensors, CRISPR-based detection systems, automated microscopy, and AI-assisted diagnosis offer promising pathways to overcome these diagnostic constraints [7] [14] [8]. These platforms leverage advances in nanotechnology, molecular biology, and computational analytics to deliver rapid, sensitive, and operator-independent diagnostic capabilities [14] [9]. The research reagent toolkit provides essential components for developing and implementing these next-generation solutions.

For researchers and drug development professionals, addressing these diagnostic limitations is paramount for advancing both therapeutic interventions and eradication campaigns. Improved diagnostics enable more accurate patient stratification, therapeutic monitoring, and epidemiological surveillance—all critical components of comprehensive parasitic disease control strategies. By integrating the technological frameworks and experimental approaches outlined in this analysis, the scientific community can accelerate progress toward definitive diagnosis and effective management of parasitic diseases globally.

The Urgent Need for Innovation in Endemic and Resource-Limited Settings

Parasitic infections pose a critical global health challenge, disproportionately affecting nearly a quarter of the world's population in tropical and subtropical regions [9]. These diseases, including malaria, schistosomiasis, and leishmaniasis, contribute significantly to the global burden of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), with the World Health Organization identifying 13 of 20 NTDs as parasitic in origin [9]. The profound health impacts include malnutrition, anemia, impaired cognitive development in children, and increased susceptibility to other infectious diseases, thereby perpetuating cycles of poverty and hindering socioeconomic development in endemic regions [9]. In 2022 alone, malaria caused an estimated 249 million cases and over 600,000 deaths globally [14]. The economic burden is equally staggering, with India alone losing approximately $1.94 billion to malaria control in 2014, while visceral leishmaniasis drains 11% of annual household expenditures in affected areas of Bihar [9].

The accurate and timely diagnosis of parasitic infections is fundamental to treatment, control, and elimination efforts. Precise diagnosis enables targeted therapy, helps prevent the development of drug resistance, facilitates surveillance, and allows for monitoring treatment response [9]. However, endemic and resource-limited settings face profound challenges in diagnostic capacity, including limited access to laboratory infrastructure, technical expertise, and reliable electricity. These constraints are compounded by the complex life cycles of many parasites, which can involve multiple hosts and environmental reservoirs, creating additional complications for detection and control [9]. The emergence of drug resistance in parasites further intensifies the need for diagnostic methods that can guide appropriate treatment regimens [9]. This whitepaper examines the limitations of conventional diagnostic approaches and explores innovative technologies that promise to revolutionize parasitic disease management in the most vulnerable populations.

Limitations of Conventional Diagnostic Methods

Traditional diagnostic methods for parasitic infections have remained largely unchanged for decades and present significant limitations in both accuracy and practicality for resource-limited settings. These conventional approaches primarily include microscopic examination, serological assays, and basic molecular techniques, each with distinct constraints that affect their utility in endemic areas.

Microscopy and Serological Constraints

Microscopy, long considered the "gold standard" for parasitic diagnosis, requires expert operators for reliable results, as several parasite eggs and morphological forms can be difficult to distinguish visually [14]. The sensitivity of microscopy is highly dependent on parasite burden and technician skill, leading to potential misdiagnosis in low-intensity infections [14]. Serological assays such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), immunoblotting, and immunofluorescence assays (IFA) detect either parasite antigens or host antibodies [14]. While these methods offer better sensitivity than microscopy for some infections, they face substantial limitations including cross-reactivity between related parasite species, inability to distinguish between past exposure and active infection, and variable performance across different geographic regions due to parasite genetic diversity [9] [10]. Furthermore, these tests often cannot be used to monitor treatment response, as antibodies may persist long after successful parasite clearance [10].

Challenges in Resource-Limited Settings

The infrastructure requirements of conventional diagnostic methods present nearly insurmountable barriers in many endemic regions. Microscopy requires reliable electricity, high-quality microscopes, reagents, and trained personnel that may be unavailable in remote areas [8]. Similarly, standard ELISA procedures necessitate well-equipped laboratory environments with consistent power supply, refrigeration capabilities, and technical expertise [8]. The time-consuming nature of these methods, from sample preparation to result interpretation, creates additional bottlenecks in clinical settings with high patient volumes. Transportation of samples from remote collection sites to centralized laboratories introduces further delays in diagnosis and treatment initiation, compromising patient outcomes and impeding public health control efforts [19]. These limitations collectively underscore the critical need for innovative diagnostic solutions that maintain accuracy while overcoming the practical constraints of endemic settings.

Innovative Diagnostic Technologies

The evolving landscape of parasitic disease diagnostics includes several promising technological approaches that offer solutions to the limitations of conventional methods. These innovations span molecular, nanomaterial, and imaging-based platforms, each with distinct advantages for resource-limited settings.

Advanced Molecular Techniques

Molecular diagnostics have transformed parasitic disease detection through enhanced sensitivity and specificity. Digital PCR (dPCR) represents a significant advancement over quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), offering absolute quantitation without requiring standard curves and demonstrating higher resilience to inhibitors present in stool samples [20]. dPCR has shown particular utility for malaria screening and schistosomiasis elimination programs due to its superior sensitivity in detecting low parasite densities [20]. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) provides an alternative nucleic acid amplification method that operates at constant temperatures, eliminating the need for thermal cyclers and making it suitable for field applications [10]. CRISPR-Cas systems have recently been adapted for parasitic diagnosis, leveraging the precision and programmability of these platforms to create highly specific and sensitive detection tools that can be deployed in point-of-care formats [8]. These systems can identify parasite-specific nucleic acid sequences with high specificity, offering rapid, portable, and cost-effective diagnostic solutions [8].

Nanotechnology and Biosensors

Nanobiosensors represent a revolutionary approach to parasitic detection, integrating nanotechnology with biological recognition elements to create highly sensitive diagnostic platforms [14]. These devices utilize various nanomaterials including gold nanoparticles, quantum dots, carbon nanotubes, and graphene oxide, each providing unique advantages for pathogen detection [14]. Nanobiosensors can detect parasite antigens, genetic material, or specific biomarkers like excretory-secretory products and microRNAs with exceptional sensitivity, often identifying targets at concentrations undetectable by conventional methods [14]. The detection mechanisms employed in these platforms include:

- Electrochemical nanobiosensors that measure electrical signal changes when parasitic antigens or DNA bind to nanoparticle surfaces [14]

- Optical nanobiosensors utilizing surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) to detect binding events through changes in optical properties [14]

- Magnetic nanobiosensors that employ magnetic nanoparticles to isolate and concentrate target molecules from complex clinical samples like blood [14]

These nanobiosensors offer rapid, accurate, and cost-effective results while enabling miniaturization and integration with point-of-care platforms [14].

Artificial Intelligence and Advanced Imaging

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI), particularly convolutional neural networks and deep learning algorithms, is revolutionizing parasitic diagnosis by enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of detection [9]. AI-based image recognition systems can automate the interpretation of microscopic images, reducing reliance on expert microscopists and increasing throughput [8]. These systems are being trained to identify various parasite life cycle stages in blood, stool, and tissue samples with accuracy comparable to or exceeding human experts [9]. Advanced imaging technologies combined with improved staining techniques further enhance visualization of parasitic elements, while portable imaging devices equipped with AI algorithms bring diagnostic capabilities directly to remote communities [8]. The integration of telemedicine platforms with these automated imaging systems creates additional opportunities for expert consultation and quality assurance in low-resource settings.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Diagnostic Technologies for Parasitic Infections

| Technology | Sensitivity | Specificity | Time to Result | Infrastructure Requirements | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopy | Low to Moderate | Moderate | 30-60 minutes | Microscope, trained technician | Low |

| ELISA | Moderate | Moderate to High | 2-4 hours | Plate reader, incubator | Moderate |

| Conventional PCR | High | High | 3-6 hours | Thermal cycler, electrophoresis | High |

| dPCR | Very High | Very High | 2-3 hours | dPCR platform, microfluidic chip | Very High |

| LAMP | High | High | 1-2 hours | Water bath/block heater | Moderate |

| Nanobiosensors | Very High | Very High | <30 minutes | Minimal (varies by type) | Low to Moderate |

| AI-Microscopy | Moderate to High | Moderate to High | <30 minutes | Microscope, computing device | Moderate |

Table 2: Nanobiosensor Applications for Major Parasitic Diseases

| Parasite | Disease | Nanomaterial | Target Biomarker | Detection Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmodium spp. | Malaria | Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) | PfHRP2 antigen | Electrochemical |

| Leishmania spp. | Leishmaniasis | Quantum dots (QDs) | kDNA | Fluorescence |

| Echinococcus granulosus | Cystic Echinococcosis | Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) | Anti-EgAgB antibodies | Immunosensor |

| Schistosoma spp. | Schistosomiasis | Graphene oxide (GO) | Soluble egg antigen (SEA) | Electrochemical |

| Taenia spp. | Taeniasis/Cysticercosis | Metallic nanoparticles | Parasite antigens | Optical |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Digital PCR for Low-Parasite Density Detection

Principle: dPCR partitions a sample into thousands of nanoliter-sized reactions, with each partition containing zero or one target DNA molecule. After endpoint amplification, the fraction of positive partitions is counted to provide absolute quantification of the target without a standard curve [20].

Protocol for Malaria Detection:

- DNA Extraction: Use commercial kits (QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit) to extract DNA from 200μL whole blood. Include negative and positive controls.

- Reaction Mix Preparation: Prepare 20μL reactions containing 1X dPCR master mix, 900nM primers, 250nM probe targeting Plasmodium 18S rRNA gene, and 5μL template DNA.

- Partitioning: Load reaction mix into dPCR cartridge (Bio-Rad QX200 system) for droplet generation (approximately 20,000 droplets per sample).

- Amplification: Perform PCR cycling: 95°C for 10min (enzyme activation), then 40 cycles of 94°C for 30s (denaturation) and 55°C for 60s (annealing/extension).

- Reading and Analysis: Transfer plate to droplet reader, which counts positive and negative droplets for each sample. Calculate parasite concentration using the formula: Copies/μL = -ln(1-p)*V, where p=fraction of positive partitions and V=partition volume [20].

Troubleshooting: Inhibitor-resistant polymerases are recommended for stool samples. DNA load optimization (1-10ng/μL) is critical to avoid saturation [20].

Gold Nanoparticle-Based Immunosensor for Malaria Antigen Detection

Principle: This lateral flow assay utilizes AuNPs conjugated with antibodies against Plasmodium falciparum histidine-rich protein 2 (PfHRP2). Antigen presence causes accumulation of AuNPs at test line, producing a visible color change [14].

Protocol:

- AuNP Synthesis and Functionalization:

- Prepare 15nm AuNPs by reducing tetrachloroauric acid with trisodium citrate.

- Adjust AuNP solution to pH 8.5 with K₂CO₃.

- Add anti-PfHRP2 monoclonal antibodies (10μg/mL final concentration) and incubate 1h at room temperature.

- Block with 1% BSA for 30min to prevent non-specific binding.

- Centrifuge at 12,000g for 15min to remove excess antibody and resuspend in storage buffer.

Lateral Flow Strip Assembly:

- Apply conjugated AuNPs to glass fiber pad (conjugate pad).

- Spray capture antibody (different anti-PfHRP2 clone) and control antibody on nitrocellulose membrane as test and control lines, respectively.

- Assemble components (sample pad, conjugate pad, membrane, absorbent pad) on backing card and cut into 4mm strips.

Testing Procedure:

- Add 100μL whole blood or serum to sample well.

- Allow migration for 15min.

- Visual interpretation: both control and test lines visible = positive; only control line visible = negative [14].

Quality Control: Include known positive and negative controls with each batch. Control line must always appear for valid test.

Diagram 1: Malaria Nanosensor Workflow. The lateral flow strip components and result interpretation for PfHRP2 detection.

CRISPR-Cas Based Detection of Parasitic DNA

Principle: Cas12a or Cas13 enzymes complexed with guide RNAs specific to parasite DNA or RNA exhibit collateral nuclease activity upon target recognition, cleaving reporter molecules to generate fluorescence [8].

Protocol for Trypanosoma cruzi Detection:

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Use boil-and-spin method (10μL blood boiled 10min, centrifuged 2min at 10,000g) or commercial kits for DNA extraction.

- RPA Pre-amplification: Prepare 50μL recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) reaction with:

- 29.5μL rehydration buffer

- 5μL template DNA

- 420nM forward and reverse primers targeting T. cruzi repetitive sequence

- 14mM magnesium acetate

- Incubate 15-20min at 39°C

- CRISPR Detection:

- Prepare 20μL reaction containing:

- 1X Cas12 buffer

- 50nM LbCas12a enzyme

- 60nM gRNA (specific to amplified T. cruzi sequence)

- 500nM fluorescent reporter (ssDNA with 5'-FAM, 3'-BHQ)

- 5μL RPA product

- Incubate 15-30min at 37°C

- Visualize with UV light or portable fluorometer [8]

- Prepare 20μL reaction containing:

Interpretation: Fluorescence indicates positive detection. Include no-template and negative sample controls.

Diagram 2: CRISPR-Cas Parasite Detection. The workflow from sample preparation to signal generation through collateral cleavage activity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Advanced Parasitic Diagnostics Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (15-40nm) | Signal generation in lateral flow assays; plasmonic sensing | Malaria (PfHRP2 detection), Leishmania antigen detection | Size affects color intensity; must be conjugated with specific antibodies [14] |

| Quantum Dots (CdSe/ZnS) | Fluorescent labels for biosensors | Leishmania DNA detection, parasite imaging | High quantum yield; size-tunable emission; potential cytotoxicity concerns [14] |

| CRISPR-Cas Enzymes (Cas12a, Cas13) | Nucleic acid detection through collateral cleavage | Trypanosoma cruzi, Plasmodium species detection | Requires specific PAM sequences; gRNA design critical for specificity [8] |

| Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) Kits | Isothermal nucleic acid amplification | Field-based parasite DNA/RNA detection | Works at 37-42°C; faster than PCR; sensitive to inhibitor interference [8] |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles (Fe₃O₄) | Sample preparation; target concentration | Parasite DNA extraction from blood/stool; antigen capture | Surface functionalization with silanes/carboxyl groups for antibody binding [14] |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes | Electrochemical sensing platforms | Multiplex parasite detection; biomarker quantification | Carbon, gold, or platinum surfaces; enable miniaturization of diagnostic devices [14] |

| Monoclonal Antibodies (Parasite-Specific) | Capture and detection agents | ELISA, lateral flow assays, immunosensors | Must be validated for cross-reactivity; critical for test specificity [10] |

| 2-(Vinyloxy)ethanol | 2-(Vinyloxy)ethanol, CAS:764-48-7, MF:C4H8O2, MW:88.11 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Siderochelin C | Siderochelin C|CAS 93973-61-6|RUO | Siderochelin C is a ferrous-ion chelating siderophore for iron metabolism research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or diagnostic use. | Bench Chemicals |

Implementation Challenges and Future Directions

The translation of innovative diagnostic technologies from research laboratories to field implementation in endemic settings faces several significant challenges that must be addressed to realize their full potential.

Technical and Infrastructural Hurdles

Nanobiosensor mass production requires standardization and quality control measures that are currently lacking, with batch-to-batch variation in nanomaterial synthesis posing a particular challenge [14]. The interference from biological matrices (hemoglobin in blood, bilirubin in stool) can affect assay performance and must be mitigated through robust sample processing methods [14]. The development of multiplex detection capabilities for co-infections (e.g., malaria and schistosomiasis) presents technical challenges in assay design and signal discrimination but is essential for comprehensive patient care in endemic areas [14]. Device stability under tropical conditions of high temperature and humidity represents another critical consideration, requiring specialized packaging and reagent formulations to maintain performance throughout supply chains and storage [19].

Accessibility and Integration Pathways

The World Health Organization has established the Diagnostics Technical Advisory Group (DTAG) for neglected tropical diseases to address priority areas in diagnostic development and identify gaps in access to available tools [19]. Target Product Profiles (TPPs) developed by WHO outline the desired characteristics of diagnostics for specific diseases, guiding research and development toward practical field applications [19]. Successful integration of new technologies requires:

- Development of sample-to-answer systems that minimize manual processing steps

- Connectivity solutions for result reporting and surveillance in low-infrastructure settings

- Local training programs for device operation and maintenance

- Sustainable supply chains for reagents and consumables

- Implementation of quality assurance systems to maintain testing accuracy [19]

Future development priorities include the creation of multiplex nanobiosensors using polymer nanofibers or hybrid nanoparticles for simultaneous detection of multiple pathogens, along with integration of lab-on-a-chip technology for true point-of-care testing [14]. The combination of AI-assisted image analysis with portable imaging devices presents another promising direction for increasing accessibility to expert-level diagnostic capabilities in remote settings [9]. Multi-omics approaches integrating genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data offer potential for discovering novel biomarkers that could further enhance the sensitivity and specificity of next-generation diagnostic platforms [8]. Through coordinated efforts between researchers, product developers, endemic country health systems, and global health organizations, these innovative diagnostic technologies can transform the management and control of parasitic diseases in the world's most vulnerable populations.

Next-Generation Diagnostic Technologies: Principles and Workflows for Modern Laboratories

The definitive diagnosis of parasitic diseases represents a critical frontier in medical research and public health. Traditional diagnostic methods, such as microscopy and serology, are often hampered by limitations in sensitivity and specificity, particularly in cases of low-level or cryptic infections. The emergence of molecular assays has fundamentally transformed this landscape, providing researchers and clinicians with powerful tools for precise pathogen detection and identification. These nucleic acid-based technologies, including Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), Real-Time PCR (also known as quantitative PCR or qPCR), and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), enable the direct detection of parasitic DNA or RNA with unparalleled accuracy. Their integration into parasitology research has not only accelerated the pace of discovery but also refined our understanding of parasite biology, epidemiology, and host-pathogen interactions, thereby forming the cornerstone of modern diagnostic and drug development pipelines.

Within the context of a broader thesis on definitive diagnosis, molecular assays provide the foundational data required for understanding disease dynamics, tracking resistance patterns, and validating therapeutic targets. This technical guide delves into the principles, methodologies, and applications of these core technologies, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for their implementation in parasitic disease research.

Fundamental Principles and Evolution

The evolution of molecular diagnostics in parasitology has progressed from simple amplification to sophisticated quantification and massive parallel sequencing. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) serves as the foundational technique, enabling the exponential in vitro amplification of specific target DNA sequences from minute starting quantities. This process, catalyzed by a thermostable DNA polymerase, allows for the detection of parasite DNA even in early or low-parasite-burden infections [21].

Building upon this, Real-Time PCR (qPCR) incorporates fluorescent detection systems to monitor the accumulation of amplification products in real time during each cycle of the PCR. This innovation transforms PCR from a qualitative tool into a robust quantitative assay. The key quantitative parameter is the Ct (threshold cycle) value, which is the cycle number at which the fluorescent signal exceeds a background threshold. A lower Ct value correlates directly with a higher starting concentration of the target nucleic acid [22] [23]. Two primary chemistries are employed for detection in qPCR:

- TaqMan Probes (Hydrolysis Probes): These are sequence-specific oligonucleotides labeled with a fluorescent reporter dye at the 5' end and a quencher at the 3' end. When intact, the quencher suppresses the reporter's fluorescence. During amplification, the 5'→3' exonuclease activity of the DNA polymerase cleaves the probe, separating the reporter from the quencher and generating a fluorescent signal proportional to the amount of amplicon synthesized [22] [24].

- SYBR Green I Dye: This is an inexpensive intercalating dye that fluoresces brightly when bound to double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). While cost-effective, it binds non-specifically to any dsDNA, including non-specific products and primer-dimers, necessitating careful assay optimization and post-amplification melt curve analysis to verify reaction specificity [22] [24].

The most transformative advancement has been Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), also known as Massively Parallel Sequencing. Unlike PCR-based methods that interroga te predefined targets, NGS enables unbiased, high-throughput sequencing of millions to billions of DNA fragments simultaneously [25] [21]. This hypothesis-free approach allows for comprehensive pathogen detection, discovery of novel parasites, and detailed investigation of parasite population genetics and resistance markers without prior knowledge of the sequences present [26] [27].

Quantitative and Performance Comparison

The following tables provide a consolidated summary of the technical capabilities and performance characteristics of these molecular assays, based on current research and application data.

Table 1: Comparative overview of core molecular technologies for parasite identification

| Feature | PCR + Sanger Sequencing | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Target amplification & sequence confirmation | Quantitative nucleic acid detection | Massive parallel sequencing & discovery |

| Quantitative Output | No | Yes (Relative quantification) | Yes (Read counts for relative quant.) |

| Sequence Discovery | Limited (single target) | No | Yes (unbiased) |

| Multiplexing Capacity | 1 target per reaction | 1 to 5 targets per reaction [23] | 1 to >10,000 targets [23] |

| Typical Turnaround Time | ~1-3 hours (PCR) + ~8 hours (Sequencing) [23] | 1 - 3 hours [23] | Several hours to days [23] |

| Sensitivity | Low-frequency mutation detection limited to ~5% [21] | High; can detect low parasitemia [28] | Very high; can detect low-abundance pathogens [27] |

| Key Applications | Variant analysis, CRISPR editing confirmation, species ID | Gene expression, pathogen load monitoring, drug efficacy studies | Pathogen discovery, strain typing, resistance marker screening, metagenomics |

Table 2: Performance of diagnostic methods in a malaria case study (Northwest Ethiopia, 2025) Data derived from a comparative study using multiplex qPCR as a reference standard on peripheral and placental blood samples [28].

| Diagnostic Method | Sensitivity (Peripheral Blood) | Specificity (Peripheral Blood) | Sensitivity (Placental Blood) | Specificity (Placental Blood) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopy | 73.8% | 100% | 62.2% | 100% |

| Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT) | 67.6% | 96.5% | 62.2% | 98.8% |

| Multiplex qPCR (Reference) | 100% | 94.8% | 100% | 94.8% |

This study highlights a critical challenge in parasitology: the significant proportion of submicroscopic infections that are missed by conventional methods but detected by molecular tools like qPCR. These subpatent infections can cause adverse clinical outcomes, underscoring the importance of sensitive molecular diagnostics for definitive diagnosis [28]. The study also demonstrated that a pooled testing strategy with multiplex qPCR obviated about half the reactions and associated costs, presenting a resource-efficient strategy for epidemiological surveillance [28].

Experimental Protocols for Parasite Identification

Protocol 1: Multiplex Real-Time PCR for Plasmodium Detection

This detailed protocol is adapted from a recent comparative study conducted in northwest Ethiopia, which validated the superior performance of multiplex qPCR for detecting malaria parasites in pregnant women [28].

1. Sample Collection and DNA Extraction:

- Collect peripheral blood samples (e.g., 200 µL) in EDTA tubes. For placental malaria studies, collect placental blood samples post-delivery.

- Extract genomic DNA from all samples using a commercial DNA extraction kit. Ensure that extraction includes negative control (nuclease-free water) and positive control (DNA from a known Plasmodium-positive sample) to monitor extraction efficiency and potential contamination.

2. Multiplex qPCR Reaction Setup:

- The multiplex assay targets genus-specific sequences for Plasmodium and may include species-specific targets (e.g., P. falciparum, P. vivax).

- Reaction Mix (20-25 µL total volume):

- 1X TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and optimized buffer).

- Forward and Reverse Primers (each at a final concentration of 200-500 nM). Primer sequences are designed to target conserved regions within the Plasmodium genome.

- TaqMan Hydrolysis Probes: Use probes for different targets (e.g., Plasmodium genus, P. falciparum) labeled with distinct reporter dyes (e.g., FAM, VIC) at the 5' end and a non-fluorescent quencher (NFQ) with a minor groove binder (MGB) at the 3' end. Probes are typically used at 100-200 nM final concentration.

- 2-5 µL of template DNA.

- Adjust to final volume with nuclease-free water.

3. qPCR Amplification and Data Acquisition:

- Perform amplification on a real-time PCR instrument with the following typical cycling conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 10 minutes (to activate the hot-start polymerase).

- 45-50 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds.

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 1 minute (fluorescence data collection at this step).

- The instrument's software will collect fluorescence data for each dye channel at every cycle.

4. Data Analysis and Interpretation:

- Set the fluorescence threshold in the exponential phase of the amplification plot above the baseline noise. The software will automatically assign a Ct value to each reaction.

- A sample is considered positive for a specific target if its Ct value is less than a predetermined cut-off (e.g., Ct < 40) and shows a characteristic sigmoidal amplification curve. Negative controls should have no amplification (Ct undetermined). The use of a multiplex format allows for the simultaneous differentiation of Plasmodium species in a single reaction [28].

Protocol 2: Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing for Parasite Metagenomics

This protocol outlines a targeted NGS approach for the identification and characterization of parasites from clinical samples, which is particularly useful for detecting mixed infections and unknown pathogens [26] [27].

1. Library Preparation:

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract total nucleic acid (DNA and RNA) from the sample (e.g., blood, stool, tissue). For RNA viruses, include a reverse transcription step to generate cDNA.

- Library Construction: Prepare sequencing libraries by fragmenting the extracted DNA/cDNA, followed by end-repair, A-tailing, and ligation of platform-specific adapter sequences containing unique molecular indices (barcodes) to allow for sample multiplexing. For comprehensive analysis, use a metagenomic approach without targeted enrichment. For deeper coverage of specific parasites, use hybridization capture with biotinylated RNA baits designed against a panel of parasite genomic regions, or employ a highly multiplexed PCR amplicon approach.

2. Cluster Generation and Sequencing:

- The adapter-ligated library is loaded onto a sequencing flow cell where each fragment is clonally amplified in situ through bridge amplification or exclusion amplification, forming clusters.

- Sequencing-by-Synthesis: Run the flow cell on the NGS platform (e.g., Illumina). The instrument sequentially adds fluorescently labeled, reversibly terminated nucleotides. As each nucleotide is incorporated into the growing DNA strand, its specific fluorescent signal is imaged, determining the sequence of each cluster base-by-base [25] [21].

3. Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Demultiplexing: Assign raw sequence data (in FASTQ format) to individual samples based on their unique barcodes.

- Quality Control and Trimming: Filter reads based on quality scores and remove adapter sequences.

- Taxonomic Classification: This is a critical step for parasite identification. Two primary strategies are employed:

- Reference-Based Alignment: Map the high-quality reads to a curated database of reference parasite genomes using aligners like BWA or Bowtie2.

- De Novo Assembly and Annotation: For novel pathogens or complex samples, assemble reads into longer contiguous sequences (contigs) without a reference genome using tools like SPAdes. These contigs are then compared against public databases (e.g., NCBI NR) using BLAST for identification.

- Reporting: Generate a report detailing the identified parasite species, their relative abundance based on read counts, and any detected markers of interest (e.g., drug resistance mutations).

Visualizing Workflows and Logical Relationships

Molecular Assay Selection Pathway

The following diagram illustrates a decision-making pathway for selecting the appropriate molecular assay based on research objectives, sample number, and target scope.

TaqMan qPCR Probe Detection Mechanism

This diagram details the molecular mechanism of the TaqMan probe hydrolysis assay, a cornerstone of specific target detection and quantification in qPCR.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful implementation of molecular assays for parasite identification relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table catalogs key components essential for the experiments described in this guide.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for molecular parasite identification

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix | A pre-mixed, optimized solution containing hot-start Taq DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgClâ‚‚, and buffer for robust qPCR amplification [22]. | Provides reproducibility and convenience; essential for multiplex qPCR assays. |

| Sequence-Specific Primers | Synthetic oligonucleotides (typically 18-25 bases) designed to flank and hybridize to the target parasite DNA sequence for amplification. | Specificity is critical; design against conserved genomic regions of the target parasite. |

| TaqMan Hydrolysis Probes | Oligonucleotide probes labeled with a 5' reporter dye (e.g., FAM) and a 3' quencher/MGB. Specificity is conferred by the probe sequence [22] [24]. | MGB probes allow for shorter designs and better discrimination of single-base differences. |

| SYBR Green I Dye | A fluorescent dye that intercalates into double-stranded DNA, allowing for real-time monitoring of PCR product accumulation [22] [24]. | Cost-effective but requires post-amplification melt curve analysis to verify specificity. |

| DNA Library Prep Kit | A suite of enzymes and buffers for fragmenting DNA, repairing ends, adding 'A' tails, and ligating sequencing adapters for NGS. | Selection depends on the NGS platform (e.g., Illumina, PacBio) and application (e.g., WGS, RNA-Seq). |

| Hybridization Capture Baits | Biotinylated oligonucleotides (e.g., RNA baits) designed to enrich sequencing libraries for genomic regions of specific parasites prior to NGS. | Enables targeted sequencing, increasing coverage and cost-effectiveness for defined parasite panels. |