Advancing Parasitology Diagnostics: A Comprehensive Guide to Real-Time PCR for Intestinal Protozoa

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and scientists on the implementation of real-time PCR (qPCR) for detecting pathogenic intestinal protozoa.

Advancing Parasitology Diagnostics: A Comprehensive Guide to Real-Time PCR for Intestinal Protozoa

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and scientists on the implementation of real-time PCR (qPCR) for detecting pathogenic intestinal protozoa. It covers the foundational rationale for moving beyond traditional microscopy to molecular methods, detailing specific assay designs—including singleplex, duplex, and triplex protocols—for targets like Giardia duodenalis, Cryptosporidium spp., Entamoeba histolytica, and Dientamoeba fragilis. The content explores automated high-throughput platforms, troubleshooting for common issues like inhibitor management and DNA extraction, and presents validation data comparing commercial versus in-house tests against reference standards. By synthesizing recent multicentre and validation studies, this guide aims to support robust assay development, improve diagnostic accuracy, and inform drug efficacy testing in clinical and research settings.

The Molecular Shift: Why qPCR is Replacing Microscopy for Intestinal Protozoa Diagnosis

The Global Burden and Diagnostic Challenge of Intestinal Protozoa

Intestinal protozoan pathogens represent a significant and persistent global health challenge, contributing substantially to diarrheal morbidity and mortality worldwide. These infections disproportionately affect resource-limited settings where poor sanitation and inadequate water infrastructure facilitate transmission [1]. This application note, framed within a broader thesis on real-time PCR protocols for intestinal protozoa research, provides a comprehensive overview of the disease burden, conventional diagnostic limitations, and advanced molecular solutions for detecting these pathogens, with detailed experimental protocols for researchers and scientists.

The global impact of these infections is staggering. Recent meta-analyses reveal that protozoan pathogens are responsible for approximately 7.5% of diarrheal cases globally, with the highest prevalence observed in the Americas and Africa [1]. Collectively, intestinal protozoan parasites infect nearly 3.5 billion people worldwide and contribute to an estimated 1.7 billion annual diarrheal episodes [2] [3]. Among the most clinically significant enteric protozoa, Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, and Entamoeba histolytica account for an estimated 500 million annual diarrheal cases worldwide, contributing significantly to childhood morbidity, malnutrition, and developmental delays [1].

Global Epidemiology and Health Impact

The burden of intestinal protozoan infections reveals striking geographical and demographic disparities. Children under five in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are disproportionately affected, where these pathogens are responsible for 10-15% of diarrheal deaths and are increasingly recognized as contributors to long-term growth faltering and cognitive impairment [1]. Cryptosporidium alone causes approximately 200,000 deaths annually, with the highest burden in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia [1].

Table 1: Global Prevalence and Impact of Major Intestinal Protozoa

| Parasite | Global Prevalence/Incidence | Key Health Impacts | High-Risk Populations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Giardia duodenalis | 280 million symptomatic cases annually [3] | Watery diarrhea, bloating, malabsorption, chronic malnutrition [1] | Children in developing countries [4] |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | 1-4% worldwide; up to 10% in children in low-income regions [1] | Severe watery diarrhea; life-threatening in immunocompromised patients [1] | Children under 5, immunocompromised individuals [1] [5] |

| Entamoeba histolytica | About 1-2% true infections (10% carry Entamoeba species) [1] | Amoebiasis - bloody diarrhea, dysentery, liver abscess [1] | Populations in Central/South America, parts of Asia [1] |

| Blastocystis spp. | 50-60% in developing countries [5] | Often asymptomatic; potential association with irritable bowel syndrome [5] | General population; role in health/disease debated [4] |

The epidemiology of these infections is influenced by complex transmission patterns involving environmental, climatic, and anthropogenic factors. Climate change is altering transmission dynamics, with studies linking increased rainfall intensity to Cryptosporidium outbreaks and drought conditions to Giardia proliferation [1]. Urbanization has introduced new transmission patterns, with dense informal settlements creating ideal conditions for person-to-person spread [1].

Diagnostic Challenges and Limitations of Conventional Methods

Accurate diagnosis of intestinal protozoa remains challenging, particularly in resource-limited settings. Conventional microscopy, while widely used for its cost-effectiveness and simplicity, presents significant limitations:

- Low Sensitivity and Specificity: Microscopy-based surveillance misses 30-50% of cases detectable by molecular methods [1]. The sensitivity of light microscopy for Cryptosporidium with modified acid-fast stain is only 54.8% [4].

- Inability to Differentiate Species: Microscopy cannot differentiate pathogenic E. histolytica from non-pathogenic E. dispar and E. moshkovskii [4]. Similarly, Blastocystis consists of at least seven morphologically identical but genetically different organisms [4].

- Technical Expertise Requirements: Microscopy requires highly trained personnel, and results are subjective with inter-observer variability [5] [3].

- Time-Consuming Nature: Comprehensive microscopic examination is labor-intensive and requires experienced examiners for optimal interpretation [4].

These diagnostic challenges lead to underestimation of the true disease burden, inappropriate treatment, and impaired disease surveillance. Immunodiagnostic methods such as ELISA, while offering improved speed, still demonstrate variable sensitivity and specificity compared to molecular methods [4].

Molecular Diagnostics: Real-Time PCR Solutions

Molecular diagnostics, particularly real-time PCR (qPCR), have revolutionized the detection of intestinal protozoa by offering enhanced sensitivity, specificity, and species-level differentiation. Molecular methods enable accurate detection of protozoan infections that are often missed by conventional techniques [6] [5] [3].

Advantages of qPCR for Intestinal Protozoa Detection

- Enhanced Sensitivity and Specificity: qPCR demonstrates significantly higher sensitivity compared to microscopy and antigen-based tests [3].

- Species-Level Differentiation: qPCR can distinguish morphologically identical species such as E. histolytica and E. dispar [5] [4].

- Quantification Capabilities: Provides quantitative data on parasite load, potentially correlating with disease severity [7].

- High-Throughput Capacity: Enables processing of large sample volumes efficiently [3].

- Detection of Mixed Infections: Multiplex assays allow simultaneous detection of multiple pathogens in a single reaction [7].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Protozoan Detection by qPCR

| Reagent/Equipment | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Primers/Probes | Target-specific amplification and detection | Custom designs for E. histolytica 16S-like SSU rRNA, G. duodenalis gdh, Cryptosporidium 18S rRNA [7] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Nucleic acid purification from stool samples | QIAamp DNA Mini Kit, QIAamp DNA Fast Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen) [7] |

| qPCR Master Mix | Amplification reaction components | 2× TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix [3] |

| qPCR Instruments | Amplification and detection platform | ABI 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System, CFX Maestro [3] [5] |

| Standard Plasmids | Quantification standards | Recombinant plasmids (PUC19 vector) with target inserts [7] |

Experimental Protocol: Duplex qPCR for Intestinal Protozoa

The following protocol adapts methodologies from recent studies for detecting intestinal protozoa using qPCR [6] [5] [7]:

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

Sample Collection:

- Collect fresh stool samples or preserve in appropriate media (e.g., Para-Pak, S.T.A.R Buffer).

- Note: Preserved samples may yield better DNA quality [3].

DNA Extraction:

- Use commercial DNA extraction kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA Mini Kit, MagNA Pure 96 System).

- Mix 350 µL of stool transport buffer with approximately 1 µL of fecal sample.

- Incubate for 5 minutes at room temperature, then centrifuge at 2000 rpm for 2 minutes.

- Transfer 250 µL of supernatant for automated or manual DNA extraction.

- Include an internal extraction control to monitor extraction efficiency.

- Store extracted DNA at -20°C until analysis [3] [7].

qPCR Assay Setup

Reaction Composition:

Thermal Cycling Conditions:

Controls:

- Include positive controls (quantified standard plasmids)

- Negative controls (no-template and extraction controls)

- Internal amplification controls to detect inhibition [7]

Primer and Probe Design Considerations

- Target genetically conserved regions with species-specific variations (e.g., 18S rRNA, gdh genes).

- Ensure GC content of approximately 50% and melting temperature of ~58°C.

- Verify specificity using BLAST analysis against non-target species.

- For multiplex assays, use probes with distinct fluorophores with non-overlapping emission spectra [5] [7].

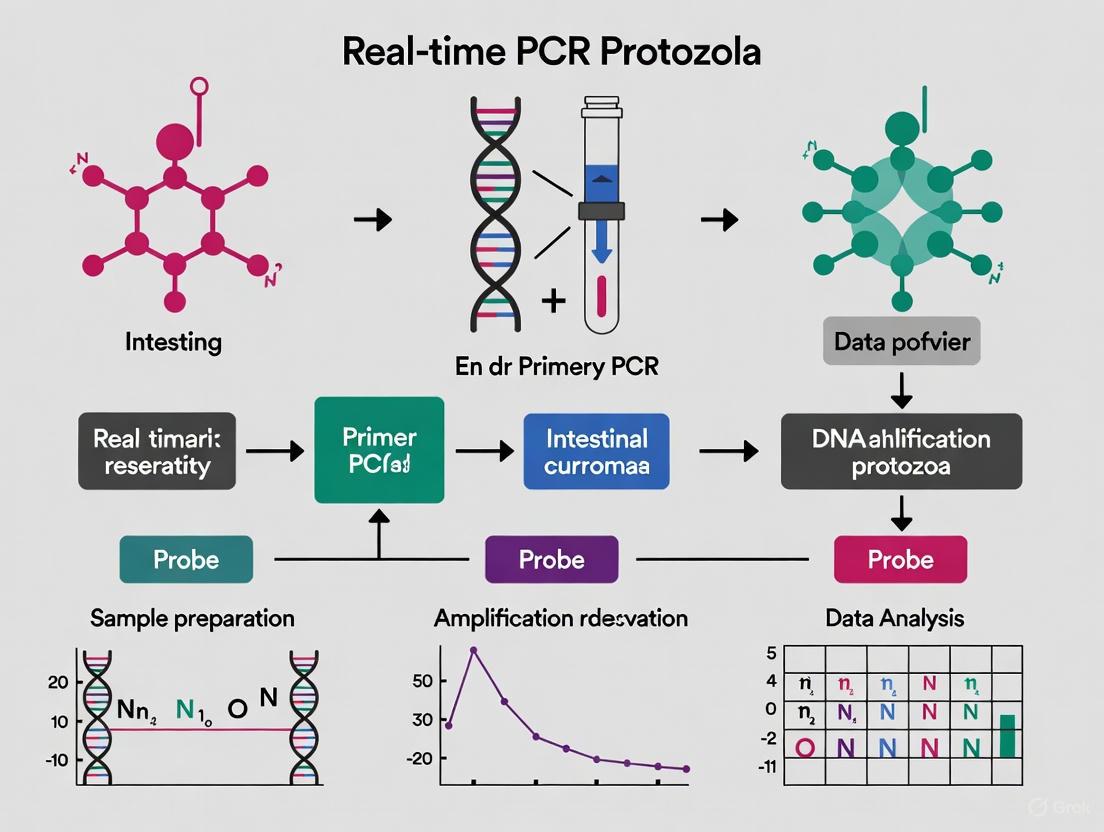

Workflow Visualization: Molecular Detection of Intestinal Protozoa

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for detecting intestinal protozoa using molecular methods:

Application in Research and Drug Development

Molecular diagnostics for intestinal protozoa play a crucial role in pharmaceutical research and drug development. Accurate detection methods are essential for:

- Clinical Trial Monitoring: qPCR provides sensitive assessment of treatment efficacy in anti-protozoal drug trials [6] [5].

- Epidemiological Studies: Accurate prevalence data informs public health interventions and resource allocation [1] [8].

- Transmission Dynamics: Molecular typing helps elucidate transmission routes and zoonotic potential [1] [4].

Recent studies have applied these methods to evaluate potential anti-protozoal compounds. For instance, a study on Pemba Island, Tanzania, utilized qPCR to assess emodepside's efficacy against intestinal protozoa, demonstrating the application of these methods in clinical research [6] [5].

Intestinal protozoan infections remain a significant global health challenge, particularly in resource-limited settings and among vulnerable populations. The development and implementation of robust molecular diagnostic methods, particularly real-time PCR protocols, are essential for accurate disease surveillance, clinical management, and drug development research. The protocols outlined in this application note provide researchers with detailed methodologies for detecting these important pathogens, contributing to improved understanding and control of intestinal protozoan diseases worldwide.

Future directions in this field include the development of point-of-care molecular tests, standardized multiplex assays for a broader range of pathogens, and integration of molecular diagnostics into routine surveillance programs in endemic areas.

Despite its long-standing role as a reference method in parasitology, conventional microscopy for intestinal protozoa diagnosis is hampered by significant limitations in sensitivity, specificity, and dependence on expert operators [9] [3]. These constraints are particularly critical in research settings and drug development programs, where diagnostic accuracy directly impacts experimental outcomes and therapeutic efficacy assessments. This application note delineates these limitations through quantitative data analysis and establishes the foundation for integrating advanced molecular methodologies into intestinal protozoa research workflows aligned with your thesis on real-time PCR protocols.

Quantitative Performance Analysis

Comparative Diagnostic Sensitivity

Multiple studies demonstrate significantly higher detection rates for molecular methods compared to conventional microscopy across major intestinal protozoa.

Table 1: Comparative Sensitivity of Microscopy Versus Molecular Methods

| Parasite | Microscopy Sensitivity | PCR Sensitivity | Study Characteristics | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giardia intestinalis | 38.0% (9/24) | 100% (24/24) | 889 samples, Danish patients | [10] |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | 0% (0/16) | 100% (16/16) | 889 samples, Danish patients | [10] |

| Dientamoeba fragilis | Not detectable | 100% (167/167) | 889 samples, Danish patients | [10] |

| Blastocystis sp. | 30.0% (19/64) | Gold standard | Compared to culture (64 positive) | [10] |

| Multiple Protozoa | 28.7% (286/995) | 90.9% (909/995) | 3,495 samples, prospective study | [11] |

Species Differentiation Capability

Microscopy cannot reliably differentiate morphologically identical species with divergent clinical significance, a critical limitation for pathogen-specific research.

Table 2: Microscopy Limitations in Species Differentiation

| Microscopic Identification | Molecular Differentiation | Clinical/Research Significance | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entamoeba histolytica/dispar/moshkovskii | E. histolytica (pathogenic) | Causes amoebic dysentery, requires treatment | [9] [12] |

| E. dispar (non-pathogenic) | Considered a commensal, no treatment needed | [5] [9] | |

| Various amoebae | E. moshkovskii (potentially pathogenic) | Pathogenicity still under investigation | [9] |

Experimental Protocols

Standard Microscopy Protocol for Intestinal Protozoa

Principle: Visual identification of protozoan trophozoites, cysts, and oocysts through morphological examination of concentrated stool samples.

Materials:

- Fresh stool sample (multiple samples recommended)

- Formalin-ethyl acetate concentration reagents

- Microscope slides and coverslips

- Light microscope with 10×, 40×, and 100× objectives

- Iodine and other staining solutions

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Collect three stool samples on alternate days to account for intermittent shedding [9].

- Concentration: Process samples using formalin-ethyl acetate concentration technique (FECT) or similar method [10] [11].

- Slide Preparation: Prepare wet mounts from concentrated sediment with and without iodine staining.

- Microscopic Examination:

- Systematically scan entire coverslip area (22 × 22 mm) at 100× and 400× magnification

- Identify protozoa based on size, shape, nuclear characteristics, and motility

- Examine multiple fields to detect low-intensity infections

- Interpretation: Differentiate pathogenic from non-pathogenic species based on morphological criteria.

Limitations: This protocol is labor-intensive, requires 30-45 minutes per sample, and depends heavily on technician expertise [9] [3]. Sensitivity remains limited even with multiple samples.

Real-Time PCR Protocol for Intestinal Protozoa

Principle: Multiplex real-time PCR detection of protozoan DNA from stool samples, enabling species-specific identification and differentiation.

Materials:

- Stool sample (200 mg) in appropriate transport medium

- DNA extraction kit (e.g., MagnaPure LC.2, MagNA Pure 96)

- Multiplex PCR master mix (e.g., SsoFast master mix, AllPlex GI-Parasite Assay)

- Real-time PCR instrument (e.g., CFX96, ABI 7900HT)

- Species-specific primers and probes

Procedure:

- DNA Extraction:

- PCR Setup:

- Prepare reaction mix containing:

- PCR buffer

- BSA (2.5 µg)

- Primers and probes (species-specific concentrations)

- Internal control primers/probe

- Aliquot 5-10 µL DNA template

- Prepare reaction mix containing:

- Amplification:

- Cycling conditions: 3 min at 95°C; 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, 30-60 s at 60°C

- Fluorescence detection at each cycle

- Analysis:

- Set threshold to 200 RFU

- Cq values <40 considered positive

- Verify internal control amplification

Advantages: This protocol detects 2.5-3× more positive samples compared to microscopy, differentiates pathogenic species, and processes multiple samples simultaneously [10] [11] [12].

Diagram: Molecular vs. Conventional Diagnostic Workflows - This diagram contrasts the streamlined, automated PCR workflow requiring a single sample against the labor-intensive, multi-sample microscopy approach, highlighting key performance advantages.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Intestinal Protozoa Research

| Reagent/Kit | Primary Function | Research Application | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| AllPlex GI-Parasite Assay | Multiplex PCR detection of 6 protozoa | Simultaneous detection of major intestinal pathogens | [11] [12] |

| MagnaPure LC.2/Nimbus | Automated nucleic acid extraction | Standardized DNA purification, reduced cross-contamination | [9] [12] |

| S.T.A.R. Buffer | Stool transport and DNA stabilization | Preserves nucleic acids during storage and transport | [3] |

| Phocine Herpes Virus | Internal extraction control | Monitors PCR inhibition and extraction efficiency | [9] |

| Seegene Viewer Software | PCR result interpretation | Automated analysis of multiplex PCR data | [12] |

| Prothrombin (18-23) | Prothrombin (18-23) | Human Peptide Fragment | Prothrombin (18-23) peptide for coagulation research. High purity, For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapy. | Bench Chemicals |

| tert-Buty-P4 | tert-Buty-P4 | Superbase Reagent | For Research Use | tert-Buty-P4 is a potent, non-ionic phosphazene superbase for deprotonation and catalysis. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Conventional microscopy exhibits critical limitations for intestinal protozoa research, with sensitivity rates of 30-75% compared to 90-100% for molecular methods, inability to differentiate pathogenic species, and substantial dependence on technical expertise [10] [9] [11]. These constraints directly impact research quality, particularly in drug development studies requiring precise endpoint measurements. The integration of validated real-time PCR protocols, as detailed in this application note, addresses these limitations through standardized, sensitive, and species-specific detection methods essential for rigorous scientific investigation of intestinal protozoa.

Fundamental Principles and Advantages of Real-Time PCR Technology

Fundamental Principles of Real-Time PCR

Real-time PCR, also known as quantitative PCR (qPCR), is a powerful molecular biology technique that allows for the detection and quantification of nucleic acids in real-time during the polymerase chain reaction, as opposed to at the end of the process like in conventional PCR [13] [14]. The core principle revolves around monitoring the amplification of a targeted DNA molecule as the reaction occurs, providing both qualitative and quantitative data [15].

The Quantification Cycle (Cq) and Amplification Curves

The quantitative capability of real-time PCR is based on the direct relationship between the initial amount of target nucleic acid and the point in the amplification process when a fluorescent signal is first detected above a background threshold [13] [15].

- Amplification Curve Phases: A typical real-time PCR amplification curve features three phases: the linear (ground) phase, the exponential (logarithmic) phase, and the plateau phase [13]. The exponential phase is the most critical for quantification because the reaction components are not yet limiting, and the amplification is most efficient [13].

- Threshold Cycle (Ct)/Quantification Cycle (Cq): This is the fractional PCR cycle number at which the reporter fluorescence exceeds a minimum detectable level, known as the threshold [13]. A sample with a high starting concentration of the target will produce a detectable signal and thus a low Cq value earlier in the amplification process. Conversely, a low initial concentration will result in a high Cq value [14] [15]. This inverse relationship is the foundation for quantification.

Detection Chemistries: Fluorescent Reporters

Real-time PCR systems use fluorescent reporters to monitor amplification, which can be broadly classified into two categories [13]:

- DNA-Binding Dyes: Dyes like SYBR Green I fluoresce brightly when bound to double-stranded DNA [14]. As the PCR product (amplicon) accumulates with each cycle, more dye binds, leading to an increase in fluorescence intensity. While cost-effective and easy to use, a key disadvantage is their lack of specificity, as they will bind to any double-stranded DNA, including non-specific amplicons and primer-dimers [14] [16].

- Sequence-Specific Probes: This category includes hydrolysis probes (e.g., TaqMan probes), molecular beacons, and hybridization probes [13]. These oligonucleotides are designed to be complementary to a specific sequence within the target amplicon and are labeled with a fluorophore and a quencher. For example, in a TaqMan assay, the 5' to 3' exonuclease activity of the DNA polymerase cleaves the probe during amplification, separating the fluorophore from the quencher and generating a fluorescent signal [14] [16]. This mechanism ensures that fluorescence is generated only if the specific target sequence is amplified, providing a high degree of specificity.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Fluorescent Detection Methods in Real-Time PCR.

| Feature | SYBR Green | TaqMan Probes |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Binds non-specifically to dsDNA | Sequence-specific probe hydrolysis |

| Specificity | Lower; detects any amplicon | High; only the specific target is detected |

| Cost | Lower | Higher |

| Complexity | Simpler; only primers needed | More complex; requires probe design |

| Multiplexing | Not possible | Possible with different colored dyes |

Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

To detect and quantify RNA targets (e.g., mRNA for gene expression or RNA viruses), the method is coupled with a reverse transcription step. This combined technique is known as reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) [17] [15]. The RNA is first transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using a reverse transcriptase enzyme. This cDNA then serves as the template for the subsequent real-time PCR amplification [13] [17]. RT-qPCR can be performed as a one-step or two-step reaction [13] [17].

- One-Step RT-qPCR: The reverse transcription and PCR amplification are performed sequentially in a single tube. This is faster, reduces pipetting steps and contamination risk, and is ideal for high-throughput applications [17].

- Two-Step RT-qPCR: The reverse transcription and PCR amplification are performed in separate tubes with individually optimized reaction conditions. This allows a single cDNA synthesis reaction to be used for multiple qPCR assays targeting different genes and provides more flexibility [13] [17].

Advantages Over Conventional PCR and Microscopy

Real-time PCR offers several significant advantages that make it a gold standard in research and diagnostics [14] [15].

- Quantification: It provides accurate, quantitative data over a broad dynamic range (up to 10^7-fold), enabling precise measurement of gene expression, viral load, or parasite burden [13] [15]. Conventional PCR is, at best, semi-quantitative [14].

- Speed and Throughput: The reaction is monitored in real-time, eliminating the need for post-PCR processing like gel electrophoresis. This speeds up analysis and facilitates high-throughput testing in 96- or 384-well formats [14] [15].

- Sensitivity and Specificity: The technique is extremely sensitive, capable of detecting down to a few copies of a target nucleic acid [15]. When using sequence-specific probes, it achieves high specificity by requiring three specific binding events (two primers and one probe) [16].

- Reduced Contamination Risk: Because the reaction tubes remain sealed after the run, the risk of cross-contamination with amplicons from previous reactions is greatly minimized [13].

- Superiority to Microscopy: For intestinal protozoa diagnosis, real-time PCR offers higher sensitivity and specificity than traditional bright-field microscopy. It can differentiate between morphologically identical species (e.g., pathogenic Entamoeba histolytica and non-pathogenic Entamoeba dispar), is less labor-intensive, and provides objective, automated readouts [5] [12].

Application in Intestinal Protozoa Research: Protocols and Data

The application of real-time PCR has revolutionized the detection and study of intestinal protozoa, providing a tool for precise species identification and burden assessment that is critical for both clinical diagnostics and research.

Experimental Protocol: Duplex qPCR for Entamoeba Species

The following protocol is adapted from a 2025 study implementing real-time PCR assays for diagnosing intestinal protozoa infections [5].

1. Sample Collection and DNA Extraction:

- Collect human stool samples and preserve appropriately (e.g., freezing at -20°C or -80°C).

- Extract genomic DNA from approximately 50-100 mg of stool specimen using a commercial DNA extraction kit. Automated nucleic acid extraction systems, such as the Microlab Nimbus IVD, are recommended for consistency and throughput [12].

2. Primer and Probe Design:

- Design primers and hydrolysis probes to target conserved, specific genomic regions. For a duplex assay detecting E. histolytica and E. dispar simultaneously, ensure each probe is labeled with a distinct fluorophore (e.g., FAM and HEX).

- The study targeting the 18S ribosomal RNA gene used these primers and probes [5]:

- Forward Primer: AGG ATT GGA TGA AAT TCA GAT GTA CA

- Reverse Primer: TAA GTT TCA GCC TTG TGA CCA TAC

- Probe for E. histolytica: TGA TTG AAT GAG TTG CTT CAA GAT GGA GT (e.g., labeled with FAM)

- Probe for E. dispar: A distinct, sequence-specific probe (e.g., labeled with HEX)

3. qPCR Reaction Setup:

- Prepare a 10 µL reaction mixture containing [5]:

- 1X qPCR Master Mix (includes DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgClâ‚‚)

- Primers (0.5 µM each)

- Probes (concentration as per manufacturer's optimization)

- 2-5 µL of template DNA

- The study utilized a 10 µL reaction volume to reduce reagent costs [5].

4. Thermal Cycling:

- Perform amplification on a real-time PCR instrument with the following typical cycling conditions [14] [5]:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2-5 minutes

- 40-45 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 60 seconds (data collection at this step)

5. Data Analysis:

- Analyze the amplification curves and assign Cq values using the instrument's software.

- Determine the presence of the target based on a Cq value below a predetermined threshold (e.g., 45) [12]. Quantification is achieved by comparing Cq values to a standard curve of known copy numbers.

Diagram 1: Workflow for real-time PCR detection of intestinal protozoa from stool samples.

Performance Data in Protozoal Detection

Real-time PCR demonstrates exceptional performance in detecting intestinal protozoa compared to traditional methods like microscopy and antigen testing.

Table 2: Diagnostic Performance of a Multiplex Real-Time PCR Assay for Intestinal Protozoa (compared to conventional methods) [12].

| Parasite | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Entamoeba histolytica | 100 | 100 |

| Giardia duodenalis | 100 | 99.2 |

| Dientamoeba fragilis | 97.2 | 100 |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | 100 | 99.7 |

A 2025 study in Tanzania further highlights the utility of qPCR in epidemiological research, where it was used to detect a high prevalence of protozoa, with Entamoeba histolytica and E. dispar found in 31.4% of patient samples [5]. The ability to distinguish the pathogenic E. histolytica (which accounted for one-third of these positives) from the non-pathogenic E. dispar is a critical advantage for appropriate patient management and accurate burden of disease studies [5] [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of real-time PCR for intestinal protozoa research requires a set of key reagents and instruments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Real-Time PCR-based Protozoa Detection.

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| qPCR Master Mix | A pre-mixed solution containing thermostable DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgClâ‚‚, and optimized buffer. | Often includes a reference dye for normalization. |

| Sequence-Specific Primers & Probes | Oligonucleotides designed to uniquely amplify and detect the target protozoan DNA. | Hydrolysis probes (TaqMan) are preferred for specificity in multiplex assays [5]. |

| DNA Extraction Kit | For purifying high-quality, inhibitor-free genomic DNA from complex stool matrices. | Automated systems (e.g., Hamilton Microlab Nimbus) enhance reproducibility [12]. |

| Positive Control Plasmid/DNA | A quantified standard containing the target sequence, essential for generating a standard curve for quantification and validating assay performance. | A plasmid clone of the target gene fragment. |

| Real-Time PCR Instrument | A thermal cycler integrated with an optical system to excite fluorophores and detect fluorescence in real-time. | Instruments from Bio-Rad (CFX96) and others. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | A pure, contaminant-free water used to make up reaction volumes, preventing enzymatic degradation of reagents. | Critical for maintaining reaction integrity. |

| 5,5/'-DINITRO BAPTA | 5,5/'-DINITRO BAPTA, CAS:125367-32-0, MF:C22H22N4O14, MW:566.43 | Chemical Reagent |

| Acetylurethane | Acetylurethane, CAS:2597-54-8, MF:C5H9NO3, MW:131.13 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Pathogen Profiles and Clinical Significance

Intestinal protozoan parasites are significant global causes of diarrheal diseases, contributing to substantial morbidity and mortality worldwide. This section details the key biological and clinical characteristics of the four major pathogenic targets.

Table 1: Comparative Profile of Key Intestinal Protozoan Pathogens

| Parameter | Giardia duodenalis (lamblia) | Cryptosporidium spp. | Entamoeba histolytica | Dientamoeba fragilis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Diplomonadida (Excavata) [18] | Apicomplexa (Diaphoretickes) [18] | Amoebozoa (Amorphea) [18] | Trichomonadina (Excavata) [18] |

| Primary Site of Infection | Duodenum, Jejunum, Ileum [18] | Duodenum, Jejunum, Ileum [18] | Colon [18] | Colon [18] |

| Global Incidence (Annual, Estimates) | ~280 million symptomatic cases [3] | Not fully quantified; major cause of childhood diarrhea [19] | ~100 million [18] | Common, but not fully quantified [18] |

| Key Clinical Presentation (Acute) | Persistent diarrhea, malabsorption, flatulence [18] [3] | Mild-to-acute diarrhea, nausea, abdominal pain, low-grade fever [18] | Diarrhea, abdominal pain; can progress to dysentery [18] [3] | Abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, anal pruritus [3] |

| Key Clinical Presentation (Chronic/Severe) | Malabsorption, loose stools, cramping, liver or pancreatic inflammations [18] | Severe diarrhea, vomiting, volume depletion; biliary/respiratory involvement in immunocompromised [18] | Fever, sepsis, liver abscesses, skin lesions [18] | Weight loss, anorexia [3] |

| At-Risk Populations | Young children in poor sanitary conditions, malnourished individuals [18] | Immunocompromised (e.g., HIV), malnourished individuals, children [18] | Individuals in endemic areas with poor sanitation [18] | Not specified in search results |

| First-Line Treatment | Metronidazole [18] | Nitazoxanide (for immunocompetent) [18] | Not specified in search results | Not specified in search results |

Molecular Detection via Real-Time PCR: Protocols and Workflows

Molecular diagnostics, particularly real-time PCR (qPCR), have surpassed traditional microscopy in sensitivity and specificity, enabling precise species-level differentiation crucial for clinical management and research [5] [3]. This section outlines standardized protocols for detecting these pathogens.

Nucleic Acid Extraction

Robust DNA extraction is critical, as the robust wall structure of protozoan cysts and oocysts can impede DNA yield [3].

- Sample Preparation: Mix 350 µL of Stool Transport and Recovery (S.T.A.R) Buffer with approximately 1 µL of fecal sample using a sterile loop. Incubate for 5 minutes at room temperature and centrifuge at 2000 rpm for 2 minutes [3].

- Supernatant Collection: Carefully transfer 250 µL of the supernatant to a fresh tube [3].

- Automated Extraction: Use the MagNA Pure 96 System with the "MagNA Pure 96 DNA and Viral NA Small Volume Kit" for automated nucleic acid purification. Add an internal extraction control (50 µL) to the sample prior to extraction to monitor extraction efficiency and PCR inhibition [3].

- Elution: Elute the purified DNA in a final volume suitable for downstream PCR applications (e.g., 50-100 µL) [3].

qPCR Assay Configuration

Both commercial multiplex and in-house singleplex assays are used for detection.

- Commercial Multiplex Assays: Platforms like the AusDiagnostics test allow for the simultaneous detection of multiple targets in a single reaction, improving workflow efficiency [3].

- In-House Singleplex/Multiplex Assays: Custom-designed assays provide flexibility. A recommended approach uses two duplex qPCR assays: one for Entamoeba dispar + Entamoeba histolytica and another for Cryptosporidium spp. + Chilomastix mesnili, alongside singleplex assays for Giardia duodenalis and Blastocystis spp. [5].

Table 2: Primer and Probe Sequences for In-House qPCR Detection

| Organism | Target Gene | Primer/Probe | Sequence (5' to 3') | Reaction Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giardia duodenalis | Small subunit ribosomal RNA [5] | Forward Primer | GCT GCG TCA CGC TGC TC [5] | 0.5 µM [5] |

| Reverse Primer | GAC GGC TCA GGA CAA CGG T [5] | 0.5 µM [5] | ||

| Cryptosporidium spp. | Small subunit ribosomal RNA [5] | Forward Primer | ACA TGG ATA ACC GTG GTA ATT CT [5] | 0.5 µM [5] |

| Reverse Primer | CAA TAC CCT ACC GTC TAA AGC TG [5] | 0.5 µM [5] | ||

| Entamoeba histolytica | Small subunit ribosomal RNA [5] | Forward Primer | AGG ATT GGA TGA AAT TCA GAT GTA CA [5] | 0.5 µM [5] |

| Reverse Primer | TAA GTT TCA GCC TTG TGA CCA TAC [5] | 0.5 µM [5] | ||

| Entamoeba dispar | 18S ribosomal RNA gene [5] | Forward Primer | AGG ATT GGA TGA AAT TCA GAT GTA CA [5] | 0.5 µM [5] |

| Reverse Primer | TAA GTT TCA GCC TTG TGA CCA TAC [5] | 0.5 µM [5] |

qPCR Reaction Setup and Thermocycling

- Reaction Mixture (In-House Example):

- 5 µL of extracted DNA template

- 12.5 µL of 2x TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix

- Primer and probe mix (final concentration as specified in Table 2)

- Nuclease-free water to a final volume of 25 µL [3]

- Thermocycling Conditions (In-House Example):

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 10 minutes (1 cycle)

- Amplification: 45 cycles of:

- 95°C for 15 seconds (denaturation)

- 60°C for 1 minute (annealing/extension) [3]

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key stages of the qPCR detection process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

A standardized set of reagents and tools is fundamental for ensuring reproducible and reliable results in protozoan research and diagnostics.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protozoan Detection

| Item | Function/Description | Example Product/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Transport Medium | Preserves nucleic acid integrity during sample storage and transport. | S.T.A.R. Buffer [3] / Para-Pak media [3] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit | Automated, high-throughput purification of DNA from complex stool samples. | MagNA Pure 96 DNA and Viral NA Small Volume Kit [3] |

| qPCR Master Mix | Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffers, and optimized components for efficient amplification. | 2x TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix [3] |

| Primers & Hydrolysis Probes | Sequence-specific oligonucleotides for target amplification and detection. Fluorescently labeled probes with a quencher. | See Table 2 for sequences [5]; Dyes/Quenchers selected based on detector capabilities [5] |

| Internal Extraction Control | Non-target nucleic acid added to samples to monitor extraction efficiency and PCR inhibition. | Critical for identifying false negatives [3] |

| Positive Control Template | Plasmid or genomic DNA containing the target sequence to validate qPCR assay performance. | Essential for run validation and ensuring primer/probe functionality |

| Commercial Multiplex PCR Kit | Pre-optimized assays for simultaneous detection of multiple pathogens, enhancing workflow efficiency. | AusDiagnostics intestinal protozoa test [3] |

| 5-Fluoro-1-indanone | 5-Fluoro-1-indanone, CAS:700-84-5, MF:C9H7FO, MW:150.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Choline chloride-15N | Choline chloride-15N Stable Isotope|287484-43-9 |

:::info The provided protocols and reagent lists serve as a foundational framework. Specific conditions, such as primer concentrations and cycling parameters, may require optimization for different laboratory setups and clinical sample types. :::

From Theory to Bench: Designing and Implementing qPCR Assays for Protozoan Detection

Within the research framework of real-time PCR (qPCR) protocols for intestinal protozoa, the selection of an appropriate assay configuration—singleplex, duplex, or triplex—is a critical determinant of experimental success. These configurations refer to the simultaneous amplification of one, two, or three distinct target sequences in a single reaction, respectively [20]. The shift from traditional, lower-throughput methods like microscopy to molecular techniques is driven by the need for greater sensitivity, specificity, and objectivity in detecting protozoa such as Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia lamblia, and Cryptosporidium spp. [11] [5] [7]. This application note provides a detailed comparison of these qPCR strategies and outlines optimized protocols for their implementation in intestinal protozoa research, providing scientists with the tools to make informed design choices.

Comparative Analysis of qPCR Configurations

The choice between singleplex and multiplex assays involves a direct trade-off between simplicity and throughput. The following table summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and challenges of each configuration.

Table 1: Strategic Comparison of Singleplex, Duplex, and Triplex qPCR Configurations

| Feature | Singleplex qPCR | Duplex qPCR | Triplex qPCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targets per Reaction | One | Two | Three |

| Primary Advantage | Simplicity; no competition for reagents; lack of ambiguity in results [20] | Balanced throughput; internal control for normalization; cost and time savings over singleplex [20] [5] | Maximum efficiency for multi-target screening; highest savings in reagents, samples, and time [20] [7] |

| Key Challenge | Lower throughput; higher reagent consumption; potential well-to-well variation | Requires dye/probe compatibility and careful optimization to prevent competition [20] | Highest complexity; increased risk of reagent competition and signal interference [20] |

| Dye/Probe Requirements | One fluorescent dye (e.g., SYBR Green) or probe (e.g., FAM) [20] | Two spectrally distinct probes (e.g., FAM and VIC) [20] [5] | Three spectrally distinct probes [7] |

| Ideal Application | Absolute quantification; assay development/validation; low-target-number studies | Pathogen detection with internal control; co-infection studies; validated two-target panels [5] | High-throughput screening of defined pathogen panels [7] [21] [22] |

| Optimization Focus | Standard curve generation; efficiency calculation | Primer limiting for dominant targets; balancing reaction efficiencies [20] | Extensive validation against singleplex; rigorous cross-reactivity testing [20] [7] |

Experimental Protocols for Intestinal Protozoa Detection

Development of a Triplex qPCR forE. histolytica,G. lamblia, andC. parvum

This protocol is adapted from a study that established a sensitive and specific triplex assay for three major intestinal protozoa [7].

1. Primer and Probe Design:

- Target Genes: Design specific primers and TaqMan probes for:

- E. histolytica: 16S-like SSU rRNA gene (GenBank X56991.1)

- G. lamblia: gdh gene (GenBank KM190761.1)

- C. parvum: 18S rRNA gene (GenBank NC_006987.1)

- Bioinformatics Validation: Confirm specificity using BLAST and Primer-BLAST against non-target sequences.

- Probe Labeling: Label each probe with a spectrally distinct fluorophore (e.g., FAM, HEX/VIC, Cy5) and a compatible quencher.

Table 2: Example Primer and Probe Sequences for Triplex qPCR [7]

| Organism | Target Gene | Primer/Probe | Sequence (5' to 3') |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entamoeba histolytica | 16S-like SSU rRNA | Forward Primer | AGCAGGATTGGATGAAATTCAGATGTACA |

| Reverse Primer | TAAGTTTCAGCCTTTGTGACCATAC | ||

| Probe | (e.g., FAM)-TGACCACCAATAGTATTC-(MGBNFQ) | ||

| Giardia lamblia | gdh | Forward Primer | GCTGCGTCACGCTGCTC |

| Reverse Primer | GACGGCTCAGGACAACGGT | ||

| Probe | (e.g., HEX)-TGCCTGCGCTCGGCT-(MGBNFQ) | ||

| Cryptosporidium parvum | 18S rRNA | Forward Primer | ACATGGATAACCGTGGTAATTCT |

| Reverse Primer | CAA TACCCTACCGTC TAAAGCTG | ||

| Probe | (e.g., Cy5)-ACTCGACTTTATGGAA GGGTTGTAT-(MGBNFQ) |

2. Reaction Setup:

- Master Mix: Use a hot-start TaqMan master mix suitable for multiplexing.

- Reaction Volume: 25 µL total volume.

- Reagent Concentrations: Optimize primer and probe concentrations (typical final concentration range: 0.1–0.5 µM for primers, 0.1–0.3 µM for probes).

- Template DNA: Add 2–5 µL of extracted DNA.

- qPCR Cycling Conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 5 min

- 45 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 sec

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 1 min

3. Validation and Analysis:

- Standard Curve: Generate using serial dilutions of quantified plasmids containing the target insert. The assay should demonstrate a linear dynamic range from at least 5 × 10² to 5 × 10⸠copies/µL with PCR efficiency >90% and R² > 0.99 [7].

- Limit of Detection (LOD): Determine the lowest copy number detectable in 95% of replicates.

- Specificity: Test against a panel of related non-target parasites (e.g., Entamoeba coli, C. baileyi, Plasmodium spp.) to ensure no cross-reactivity.

- Reproducibility: Assess intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation (CV), which should be less than 2% [7].

Implementing a Duplex qPCR Assay

Duplex assays are highly effective for distinguishing pathogenic from non-pathogenic species or including an internal control.

Example: Duplex for E. histolytica and E. dispar [5]

- Principle: These species are morphologically identical but differ clinically. A duplex qPCR allows for their precise differentiation.

- Design: Use species-specific primers and probes labeled with different dyes (e.g., FAM for E. histolytica, HEX for E. dispar) targeting the 18S rRNA gene.

- Protocol:

- Reaction Volume: Can be scaled down to 10 µL to reduce costs [5].

- Components: Similar to the triplex protocol, but with two targets.

- Critical Step: Validate that the amplification efficiencies of both targets are similar and that there is no inhibition between reactions.

Optimization Strategy for Multiplex Assays

A key challenge in multiplexing is competition for reagents, which can cause one target to amplify preferentially and starve another [20].

- Primer Limiting: If one target (e.g., a highly abundant endogenous control) amplifies earlier and exhausts reagents, significantly reduce its primer concentration. This forces it to plateau earlier, preserving reagents for the other target(s) [20].

- Experimental Validation: Before full-scale use, test 5–6 samples from both experimental and control groups in both multiplex and singleplex configurations. The results (Cq values) should be comparable between the two formats. If they disagree, further optimization is required [20].

Diagram 1: Multiplex qPCR development workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of qPCR assays relies on a suite of reliable reagents and tools.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Protozoan qPCR

| Item | Function/Description | Example Products/Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Probes | Essential for multiplexing; bind specifically to target DNA and emit a unique fluorescent signal, allowing discrimination of multiple targets in one well [20]. | TaqMan Probes (FAM, VIC, HEX, Cy5 labels) [20] [7] |

| Commercial Multiplex Kits | Integrated solutions containing pre-optimized master mixes and reagents for detecting common protozoan panels. | AllPlex GI-Parasite Assay (Seegene) [11] [22], Other marketed panels [7] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Critical for obtaining inhibitor-free, high-quality DNA from complex stool samples. Automated systems enhance throughput and reproducibility [11] [22]. | QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen) [7], STARMag Universal Cartridge (Seegene) on Hamilton STARlet [22] |

| Automated Liquid Handlers | Robots that perform nucleic acid extraction and PCR setup, reducing human error, cross-contamination, and hands-on time, especially for high-throughput labs [11] [22]. | Hamilton STARlet [11] [22] |

| Standard Plasmids | Quantified plasmids containing the target sequence; used to generate standard curves for absolute quantification and determine assay efficiency, LOD, and linear dynamic range [7]. | Cloned PUC19 vectors with target inserts [7] |

| In Silico Design Tools | Software for designing specific primers and probes and checking for off-target binding. | Primer Express (Applied Biosystems) [7], BLAST, Oligo 7 [23] |

| 1-Decanol, 2-octyl- | 1-Decanol, 2-octyl-, CAS:45235-48-1, MF:C18H38O, MW:270.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| FRG8701 | FRG8701, CAS:108498-50-6, MF:C22H30N2O4S, MW:418.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The strategic selection of singleplex, duplex, or triplex qPCR configurations directly impacts the efficiency, cost, and reliability of intestinal protozoa research. Singleplex assays remain the gold standard for simplicity and absolute quantification, while duplex and triplex configurations offer powerful solutions for high-throughput screening and complex diagnostic panels. The successful implementation of multiplex assays hinges on careful experimental design, thorough validation against singleplex methods, and the use of optimized protocols and reagents. By adhering to the detailed methodologies outlined in this document, researchers can confidently advance the detection and study of intestinal protozoa.

Within the framework of developing robust real-time PCR (qPCR) protocols for intestinal protozoa research, the selection of appropriate genetic targets is a foundational step that critically influences the sensitivity, specificity, and overall diagnostic utility of the assay. While microscopic examination remains a common diagnostic tool, its limitations in sensitivity and inability to differentiate between morphologically identical species or genotypes have driven the adoption of molecular methods [24] [3]. This document provides a detailed application note for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, focusing on the comparative performance of key genetic markers—including rRNA, gdh, and tpi—for the detection and genotyping of intestinal protozoa, with a primary emphasis on Giardia duodenalis. The protocols and data summarized herein are designed to inform assay development for both clinical diagnostics and epidemiological studies.

Comparative Performance of Genetic Targets

The choice of genetic target significantly impacts qPCR assay performance. Comparative studies have evaluated various genes for their efficacy in detection and genotyping. The table below summarizes the diagnostic accuracy of different qPCR assays for Giardia duodenalis as reported by a head-to-head comparative study [25].

Table 1: Diagnostic accuracy of qPCR screening assays for Giardia duodenalis using Latent Class Analysis (LCA)

| Target Gene | Estimated Sensitivity (%) | Estimated Specificity (%) | Key Findings and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18S rRNA | 100.0 | 100.0 | Highest diagnostic accuracy; well-suited for sensitive screening purposes. |

| bg (beta-giardin) | 31.7 | 100.0 | High specificity but lower sensitivity; may require confirmation with another target. |

| gdh (glutamate dehydrogenase) | 17.5 | 92.3 | Lowest sensitivity and specificity among compared targets; not recommended as a primary screening target. |

For genotyping G. duodenalis into its major assemblages (A and B), assays targeting different genes also show variable performance [25]:

Table 2: Performance of duplex qPCR assays for discriminating Giardia duodenalis Assemblages A and B

| Target Gene | Probe Type | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Agreement Kappa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bg | Standard Probe | 100.0 | 100.0 | 90.1% (near-perfect) |

| bg | LNA Probe | 96.4 | 84.0 | 74.8% (substantial) |

| tpi | Standard Probe | 82.1 | 100.0 | 74.8% (substantial) |

The high prevalence of mixed assemblage infections, as high as 46% in some patient cohorts, further underscores the need for robust, assemblage-discriminating assays [26]. Beyond Giardia, multi-parallel qPCR systems have been successfully implemented for detecting a range of intestinal protozoa, including Entamoeba histolytica, Cryptosporidium spp., Blastocystis spp., and Dientamoeba fragilis [6] [27].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

DNA Extraction from Stool Samples

Principle: Efficient mechanical and chemical lysis of resilient cyst/oocyst walls is critical for high-quality DNA yield [24].

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Suspend approximately 200 mg of stool specimen in sterile transport buffer (e.g., S.T.A.R. Buffer) or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). For formalin-fixed or potassium dichromate-preserved samples, wash three times with distilled water or TE buffer (10 mM Tris/HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8) to remove preservatives [28].

- Mechanical Lysis: Resuspend the pellet in 250 µL TE buffer with ~200 mg of sterile glass powder (cover glass #1). Perform three lysis cycles, each consisting of:

- 3-minute incubation at 4°C.

- 3-minute vigorous vortexing.

- Centrifugation at 21,380 x g for 2 minutes [24].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Transfer the supernatant to a new tube and proceed with a commercial silica-membrane-based DNA extraction kit (e.g., QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit, Machery-Nagel NucleoSpin Tissue Kit), following the manufacturer's instructions with an extended inhibitor removal incubation step (3 minutes) [29] [24] [3].

- DNA Quantification and Storage: Quantify DNA using a fluorometer (e.g., Qubit). Assess purity and integrity via spectrophotometry (A260/280 ratio ~1.8) and agarose gel electrophoresis. Store eluted DNA at -20°C or -80°C [26] [24].

Real-Time PCR for Detection and Genotyping ofGiardia duodenalis

Principle: This protocol describes a SYBR Green-based real-time PCR for the simultaneous detection and genotyping of G. duodenalis using assemblage-specific primers for the tpi and gdh genes [26].

Reaction Setup:

- Total Reaction Volume: 20 µL

- Reaction Mix:

- 10 µL of 2x Maxima SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix

- 2 µL of primer mix (containing forward and reverse primers at working concentration)

- 2-5 µL of template DNA (containing ~500 ng of DNA)

- Nuclease-free water to 20 µL

Table 3: Primer sequences for Giardia duodenalis genotyping

| Gene | Assemblage | Primer Sequence (5' → 3') | Amplicon Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| tpi A | A | Forward: TCGTCATTGCCCCTTCCGCCReverse: CAGTTGAGGATAGCAGCG | 77 |

| tpi B | B | Forward: GATGAACGCAAGGCCAATAAReverse: AAGAAGGAGATTGGAGAATC | 77 |

| gdh A | A | Forward: CCGGCAACGTTGCCCAGTTTReverse: TCCGAGTTCAAGGACAAGT | 180 |

| gdh B | B | Forward: CGTATTGGCGTCGGCGGTReverse: CTATCAGACCAGAGGCCACA | 133 |

Thermal Cycling Conditions (Rotor-Gene PCR System):

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 10 minutes (1 cycle)

- Amplification: 40-45 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds

- Annealing: 59°C for 30 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 30 seconds

- Melt Curve Analysis: Perform after amplification to verify PCR specificity.

Analysis: Include positive controls (known G. duodenalis assemblage A and B DNA) and negative controls (nuclease-free water) in each run. A sample is considered positive for a specific assemblage if its amplification curve crosses the threshold within the cycle limit and shows the correct melt curve peak [26].

Workflow and Decision Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for the molecular detection and genetic characterization of intestinal protozoa, from sample collection to final interpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and their functions for establishing the described molecular protocols.

Table 4: Essential research reagents and materials for molecular detection of intestinal protozoa

| Item | Function/Application | Example Product/Note |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Nucleic acid purification from complex stool matrices; critical for removing PCR inhibitors. | QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (QIAGEN), NucleoSpin Tissue Kit (Machery-Nagel) [29] [26] [24] |

| qPCR Master Mix | Provides enzymes, dNTPs, and buffer for efficient, specific amplification in real-time PCR. | Maxima SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Thermo Scientific) [26] |

| Assemblage-Specific Primers | For specific detection and differentiation of Giardia assemblages (e.g., A, B) or other protozoan genotypes. | Custom oligonucleotides targeting tpi, gdh, or bg genes [26] [25] |

| Positive Control DNA | Essential for validating assay performance and ruling out PCR failure. | Genomic DNA from known Giardia assemblages A and B [26] |

| Automated Nucleic Acid Extractor | Standardizes and improves throughput of the DNA extraction process. | MagNA Pure 96 System (Roche) [3] |

| Real-Time PCR System | Platform for running qPCR assays and analyzing amplification data. | Rotor-Gene Q (QIAGEN), ABI 7900HT (Applied Biosystems) [26] [3] |

| Asoprisnil ecamate | Asoprisnil ecamate, CAS:222732-94-7, MF:C31H40N2O5, MW:520.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Mollugogenol A | Mollugogenol A, CAS:22550-76-1, MF:C30H52O4, MW:476.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Within the framework of thesis research focused on develoing real-time PCR (qPCR) protocols for the detection of intestinal protozoa, the extraction of high-quality DNA from stool samples is a critical first step. The presence of PCR inhibitors and the robust structural nature of parasite cysts and oocysts present significant technical challenges that can lead to false-negative results if not properly addressed [30]. This application note provides a detailed, optimized protocol for nucleic acid extraction and subsequent qPCR setup, incorporating recent comparative data to guide method selection for superior sensitivity in parasite detection.

DNA Extraction from Stool Samples

Principle

The goal of this protocol is to achieve comprehensive mechanical and chemical lysis of a wide range of intestinal parasites—from fragile protozoa like Blastocystis sp. to helminths with tough eggshells like Ascaris lumbricoides—while simultaneously removing co-purified PCR inhibitors present in the fecal matrix [30]. The protocol below is adapted from the CDC-approved procedure and incorporates a bead-beating step, which has been demonstrated to significantly enhance DNA yield and detection rates [31] [30].

Materials and Equipment

- Sample: Fecal specimen, divided into aliquots and stored at -80°C without preservative, or preserved in 70% ethanol or potassium dichromate [31].

- Primary Kit: QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (Qiagen) or FastDNA Kit (MP Biomedicals) [31] [30].

- Mechanical Lysis Equipment: Tissue homogenizer (e.g., FastPrep-24 or similar) and lysing matrix tubes containing silica beads [31].

- Reagents:

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.2

- EDTA solution, 0.5 M, pH 8.0

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) [31]

- Lab Consumables: Microcentrifuge tubes, pipette tips, and a microcentrifuge.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Sample Preparation and Washing

- Label a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube.

- Centrifuge a 300-500 µL aliquot of stool specimen at 14,000 × g at 4°C for 5 minutes. Carefully discard the supernatant.

- Resuspend the pellet in 1 mL of PBS-EDTA. Centrifuge again at 14,000 × g at 4°C for 5 minutes and discard the supernatant.

- Repeat the wash step two more times for a total of three washes [31].

- After the final wash, resuspend the pellet in PBS-EDTA to a final volume of approximately 300 µL.

Step 2: Bead-Beating and Lysis

- Transfer the 300 µL of washed sample into a lysing matrix tube containing silica beads.

- Add the following reagents to the tube:

- 400 µL of CLS-VF (Cell Lysis Solution)

- 200 µL of PPS (Protein Precipitation Solution)

- PVP to a final concentration of 0.1% to 1% (to bind polyphenolic inhibitors) [31].

- Tightly close the tube and secure it in the tissue homogenizer.

- Process the sample at a speed of 5.0-5.5 for 10-30 seconds to ensure complete disruption of tough parasite walls [31] [30].

Step 3: DNA Binding and Purification

- Centrifuge the lysed sample at 14,000 × g for 5 minutes at room temperature.

- Transfer 600 µL of the supernatant to a new, clean 1.5 mL tube, avoiding the pellet and debris.

- Add 600 µL of Binding Matrix to the supernatant and mix gently by inverting the tube for 1 minute.

- Incubate the mixture at room temperature for 5 minutes to allow DNA to bind to the matrix.

- Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 1 minute. Pour off the supernatant.

- Resuspend the pellet (binding matrix with DNA) in 500 µL of SEWS-M (Salt/Ethanol Wash Solution) by pipetting up and down.

- Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 1 minute and discard the supernatant.

- Perform a quick spin (10 seconds) and remove any residual wash solution with a fine tip.

Step 4: DNA Elution

- Add 50-100 µL of DES (DNA Elution Solution) or TE buffer to the pellet. Resuspend thoroughly by pipetting.

- Incubate at room temperature for 2-5 minutes.

- Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 2 minutes.

- Carefully transfer the supernatant, which contains the purified DNA, to a clean, labeled tube.

- Store the extracted DNA at 4°C for immediate use or -20°C for long-term storage.

Troubleshooting and Quality Control

- Inhibitor Removal: If PCR inhibition is suspected, further purify the eluted DNA using an inhibitor removal column, such as the OneStep PCR Inhibitor Removal Kit [32].

- Sample Consistency: For watery stools, use tips with cut ends to pipet both liquid and particulate matter. For viscous samples, use less starting material to avoid overloading the purification column [32].

- DNA Quality Assessment: Evaluate DNA concentration and purity using a spectrophotometer. Optimal 260/280 absorbance ratios are close to 1.8 [33].

Reaction Setup for Real-Time PCR

Primer and Probe Design

For the detection of intestinal protozoa, primers and probes should target conserved, multi-copy genes. The small subunit ribosomal RNA (18S rRNA) gene is a common and reliable target [5]. The table below provides examples of tested primer and probe sequences for key protozoan parasites.

Table 1: Example qPCR Primers and Probes for Intestinal Protozoa

| Organism | Target Gene | Forward Primer (5'->3') | Reverse Primer (5'->3') | Probe Sequence (5'->3') | Reaction Volume |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giardia duodenalis | Small subunit rRNA | GCT GCG TCA CGC TGC TC | GAC GGC TCA GGA CAA CGG T | (FAM)-TGC CGC CGG CGC (BHQ1) | 10 µL [5] |

| Entamoeba histolytica | 18S ribosomal RNA | AGG ATT GGA TGA AAT TCA GAT GTA CA | TAA GTT TCA GCC TTG TGA CCA TAC | (CY5)-TGA CGG ATA CAG ACT GCA TTG GAA TC-(BHQ2) | 10 µL [5] |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | Small subunit rRNA | ACA TGG ATA ACC GTG GTA ATT CT | CAA TAC CCT ACC GTC TAA AGC TG | (HEX)-ACT CGA CTT TAT GGA AGG GTT GTA T-(BHQ1) | 10 µL [5] |

| Blastocystis spp. | Small subunit rRNA | GGT CCG GTG AAC ACT TTG GAT TT | CCT ACG GAA ACC TTG TTA CGA CTT CA | (FAM)-TCG TGT AAA TCT TAC CAT TTA GAG GA-(BHQ1) | 10 µL [5] |

qPCR Master Mix Setup

A typical 10 µL reaction volume can be used to reduce costs while maintaining sensitivity [5]. The reaction components are listed below.

- Table 2: qPCR Reaction Components

| Component | Final Concentration/Amount | Positive Control | No-Template Control (NTC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2x qPCR Master Mix | 5.0 µL | 5.0 µL | 5.0 µL |

| Forward Primer | 0.15 - 0.5 µM | 0.15 - 0.5 µM | 0.15 - 0.5 µM |

| Reverse Primer | 0.15 - 0.5 µM | 0.15 - 0.5 µM | 0.15 - 0.5 µM |

| Probe | 0.1 - 0.3 µM | 0.1 - 0.3 µM | 0.1 - 0.3 µM |

| Nuclease-Free Water | To 10 µL | To 10 µL | To 10 µL |

| Template DNA | 2.0 µL | 2.0 µL (known positive) | - |

qPCR Cycling Conditions

The following cycling conditions are recommended. Parameters may require optimization for different thermocyclers.

- Table 3: Standard qPCR Cycling Protocol

| Step | Cycles | Temperature | Time | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Denaturation | 1 | 95°C | 3-5 minutes | Polymerase activation and initial denaturation |

| Amplification | 40-45 | 95°C | 10-15 seconds | Denaturation |

| 60°C | 30-60 seconds | Primer annealing and extension (acquire fluorescence) |

Comparative Data and Method Selection

A 2022 comparative study evaluated four DNA extraction methods for the detection of diverse intestinal parasites via PCR. The results strongly support the use of kits incorporating bead-beating.

Table 4: Comparison of DNA Extraction Method Efficiencies [30]

| DNA Extraction Method | Description | PCR Detection Rate | Relative Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenol-Chloroform (P) | Conventional chemical lysis | 8.2% | Lowest detection rate; failed to detect most parasites. |

| Phenol-Chloroform + Beads (PB) | Chemical lysis with mechanical bead-beating | 24.7% | Improved yield but high inhibitor carryover. |

| QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Q) | Silica column-based | 47.1% | Good performance for some parasites. |

| QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QB) | Silica column with bead-beating | 61.2% | Highest detection rate; effective for all parasites tested. |

The data conclusively shows that the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QB), which integrates a bead-beating step, is the most effective method for the molecular diagnosis of intestinal parasites, yielding the highest PCR detection rate [30]. Another study confirmed that the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit produces microbiome profiles comparable to the previously widely-used QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit with a bead-beating step, while also providing more consistent DNA quality [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 5: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Lysing Matrix Tubes (Silica Beads) | Provides mechanical disruption (bead-beating) for breaking tough parasite cell walls, cysts, and oocysts [31] [30]. |

| Inhibitor Removal Technology (e.g., PVP, proprietary buffers) | Binds to and removes PCR inhibitors commonly found in stool, such as bile salts, complex polysaccharides, and polyphenolic compounds [31] [32]. |

| Silica-Based Binding Matrix | Selectively binds nucleic acids in the presence of chaotropic salts, allowing for purification and removal of contaminants [31] [34]. |

| Multiplex qPCR Assay Master Mix | Enables simultaneous detection of multiple parasite targets in a single reaction, improving speed and cost-effectiveness [5] [21]. |

| DNA/RNA Shield | A sample preservation reagent that stabilizes microbial community composition at the time of collection and prevents degradation [32]. |

| Non-8-ene-1-thiol | Non-8-ene-1-thiol|95%|For Research Use |

| 7-Bromohept-1-yne | 7-Bromohept-1-yne, CAS:81216-14-0, MF:C7H11Br, MW:175.069 |

Workflow Diagrams

Within the field of intestinal protozoa research, accurate and efficient pathogen detection is fundamental to understanding infection dynamics, disease burden, and treatment efficacy. Traditional diagnostic methods, particularly microscopy, are hampered by challenges in distinguishing morphologically identical species and often lack the sensitivity required for robust surveillance [5]. The adoption of multiplex real-time PCR (qPCR) represents a significant advancement, allowing for the simultaneous detection of multiple pathogens in a single reaction. This application note details the validation and implementation of high-throughput, automated solutions for multiplex panels, providing a structured framework for researchers and drug development professionals to ensure diagnostic accuracy and reliability in their studies on intestinal protozoa.

Performance Data of Validated Multiplex Assays

The transition to molecular methods is driven by the need for higher specificity and sensitivity, especially for distinguishing between pathogenic and non-pathogenic protozoa such as Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar [5]. The following tables summarize key performance metrics from validation studies relevant to the field.

Table 1: Analytical Sensitivity and Specificity of Representative Multiplex Assays

| Pathogen/Target | Assay Type | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Specificity | Clinical Sensitivity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entamoeba histolytica/dispar | Duplex qPCR | Not Specified | 100% (Species-level differentiation) | 31.4% Prevalence in cohort | [5] |

| Cryptosporidium spp. + C. mesnili | Duplex qPCR | Not Specified | 100% (Species-level differentiation) | Reliable detection in 74.4% of samples | [5] |

| Giardia duodenalis | Singleplex qPCR | Not Specified | 100% | High prevalence in region | [5] |

| 15 HPV Genotypes | Multiplex qPCR | Varies by genotype | 100% | 98% | [35] |

| SARS-CoV-2, IAV, IBV, RSV, hADV, MP | Multiplex FMCA-PCR | 4.94 - 14.03 copies/µL | 100% (No cross-reactivity) | 98.81% agreement with RT-qPCR | [36] |

Table 2: Throughput and Economic Comparison of PCR Platforms

| Platform / Assay Characteristic | High-Throughput System (e.g., SmartChip) | Standard Tube-Based Multiplex qPCR | Commercial Multiplex Panel (BioFire FilmArray) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Volume | 100-200 nL | 10-25 µL | Not Specified |

| Samples per Run (Max) | 768 | 96 - 384 | 1 per module |

| Total Assays per Day | >10,000 | Hundreds to low thousands | Multiple with multiple modules |

| Hands-on Time | ~30 minutes | Varies | Minimal per sample |

| Cost per Sample | Significantly reduced | Moderate | Higher |

| Key Advantage | Extreme throughput & reagent savings | Flexibility in panel design | All-in-one, simple workflow |

Experimental Protocol: Validation of a Duplex qPCR for Intestinal Protozoa

This protocol is adapted from a study that implemented duplex qPCR assays for detecting Entamoeba histolytica/dispar and Cryptosporidium spp./Chilomastix mesnili, providing a template for validating multiplex panels in intestinal protozoa research [5].

Sample Preparation and Nucleic Acid Extraction

- Sample Collection: Collect fresh stool samples from patients or animal models. Preserve samples appropriately if immediate processing is not feasible.

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Use commercially available automated (e.g., QIAcube, [37]) or manual nucleic acid extraction kits. The protocol in [5] utilized a 10 µL reaction volume, indicating small-scale extraction elution volumes (e.g., 50-100 µL) are suitable to maintain template concentration.

- Quality Control: Include an internal control, such as the human beta-globin gene [35] or a sample process control, during extraction to monitor for inhibition and confirm successful nucleic acid isolation.

Primer and Probe Design

- Target Selection: Identify highly conserved genomic regions. For protozoa, small subunit ribosomal RNA genes are common targets [5].

- Specificity Check: Use tools like NCBI BLAST to ensure primer/probe sequences are unique to the target pathogen and do not cross-react with related species or host DNA.

- Multiplexing Configuration: Label probes with distinct fluorophores (e.g., FAM, HEX, ROX) that are compatible with your real-time PCR instrument's detection channels. For the duplex assay targeting E. histolytica/dispar, species-level differentiation was achieved with specific probes [5].

qPCR Reaction Setup and Thermal Cycling

- Reaction Master Mix: Prepare a master mix containing the appropriate buffer, dNTPs, polymerase, and primers/probes. The referenced study used a 10 µL reaction volume [5].

- Thermal Cycling Conditions: A typical two-step cycling protocol is effective:

- Reverse Transcription: 50°C for 5-15 minutes (if detecting RNA).

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds to 2 minutes.

- Amplification (40-45 cycles):

- Denaturation: 95°C for 5-15 seconds.

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 30-60 seconds (acquire fluorescence at this step).

- Platform: This protocol can be performed on standard real-time PCR systems (e.g., Bio-Rad CFX96) or scaled for high-throughput on systems like the SmartChip, which uses 100-200 nL reactions and can complete a run in under four hours [38].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Threshold and Baseline: Set the fluorescence threshold in the exponential phase of amplification across all replicates and adjust the baseline according to the instrument's software recommendations.

- Cycle Threshold (Ct): Determine the Ct value for each reaction. A sample is considered positive if the Ct value is below a pre-defined cut-off (e.g., Ct < 40).

- Melting Curve Analysis (if using SYBR Green): If a dye-based assay is used, perform melting curve analysis post-amplification to verify amplicon specificity by its unique melting temperature (Tm).

Workflow Diagram: High-Throughput Multiplex PCR Validation

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for validating and running a high-throughput multiplex PCR assay, from initial design to final data analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of high-throughput multiplex PCR relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The table below details essential components for developing and running these assays.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Multiplex PCR Assays

| Item | Function/Description | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Primers & Probes | Specifically designed to target conserved genomic regions of pathogens; probes are labeled with fluorophores (e.g., FAM, HEX) for multiplex detection. | Designed for E6/E7 region of HPV [35]; for small subunit ribosomal RNA of protozoa [5]. |

| Multiplex PCR Master Mix | Optimized buffer containing DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and MgClâ‚‚ designed to support simultaneous amplification of multiple targets without competition or inhibition. | 4X CAPITAL qPCR Probe Master Mix [35]; TB Green Premix Ex Taq II [39]. |

| Automated Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit | Reagents for purifying high-quality DNA/RNA from complex samples like stool, crucial for sensitivity and reproducibility. | QIAamp Viral RNA Kit on QIAcube [37]; MPN-16C RNA/DNA extraction kit [36]. |

| Internal Control Template | Non-target nucleic acid (e.g., phage RNA, human beta-globin) spiked into the reaction to monitor for PCR inhibition and extraction efficiency. | Human beta-globin gene used in HPV assay [35]; Phocine distemper virus (PDV) used in arbovirus assay [40]. |

| Positive Control Plasmids | Plasmid DNA containing the target sequence for each pathogen in the panel, used for standard curve generation and LOD determination. | Mixed plasmids with viral target fragments for precision testing [36]. |

| High-Throughput Platform | Automated system for nanoliter-scale dispensing and cycling, enabling massive parallelization (e.g., SmartChip System). | SmartChip Real-Time PCR System for >10,000 assays/day [38]. |

| 2-Chloropentan-1-ol | 2-Chloropentan-1-ol | 139364-99-1 | C5H11ClO Building Block | Get high-purity 2-Chloropentan-1-ol (CAS 139364-99-1), a versatile C5H11ClO scaffold for organic synthesis. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Acetoxime benzoate | Acetoxime benzoate, CAS:942-89-2, MF:C9H9NO2, MW:163.176 | Chemical Reagent |

Intestinal protozoa infections represent a significant global public health challenge, contributing substantially to gastrointestinal morbidity and malnutrition, particularly in regions with poor sanitation and limited access to clean water [5]. Traditional bright-field microscopy, while cost-effective and widely used, faces considerable limitations in sensitivity and specificity, along with an inherent inability to distinguish between morphologically identical species, such as the pathogenic Entamoeba histolytica and non-pathogenic Entamoeba dispar [5]. The development of real-time PCR (qPCR) assays has revolutionized parasitology diagnostics by providing a tool for specific, sensitive, and quantitative detection of parasitic DNA [41] [42]. This case study details the implementation of novel qPCR assays, including the first molecular detection of Chilomastix mesnili by qPCR, and their application in a clinical study on Pemba Island, Tanzania, framed within a broader thesis on advanced molecular protocols for intestinal protozoa research [5] [43].

Chilomastix mesnili, while generally considered a non-pathogenic commensal, serves as an important indicator of fecal contamination of food or water sources, with a prevalence of approximately 13% in developing countries [5]. Recent genetic studies have revealed significant diversity within the genus Chilomastix, with distinct molecular classifications and subtypes identified in humans and animals [44]. The implementation of precise molecular diagnostics for such neglected protozoa is crucial for understanding their epidemiology and genetic diversity, while also monitoring and controlling the burden of intestinal protozoal diseases more effectively [5] [44].

Literature Review and Scientific Rationale

The Diagnostic Shift from Microscopy to Molecular Methods

For decades, microscopic examination of stool specimens has been the reference method for diagnosing intestinal protozoan infections [3]. Although cost-effective, this technique is labor-intensive, requires highly trained personnel, and suffers from subjective interpretation and poor sensitivity, especially in cases of low parasite burden [5] [45] [3]. Crucially, microscopy cannot differentiate between morphologically identical species with varying clinical significance, such as E. histolytica and E. dispar [5] [3]. This distinction is vital as E. histolytica causes amoebiasis, responsible for 40,000–100,000 deaths annually, while E. dispar is considered non-pathogenic [5].

Molecular methods, particularly qPCR, have emerged as powerful alternatives, offering superior sensitivity, specificity, and the ability to provide quantitative data [41] [45] [42]. qPCR operates on the principle of fluorescently monitoring DNA amplification in real-time, with the quantification cycle (Cq) value providing a reliable metric for determining the initial quantity of target DNA [41] [42]. The advantages of qPCR include a wide dynamic range (7–8 Log10), reduced risk of contamination compared to conventional PCR, and the potential for multiplexing several targets in a single reaction [41] [42]. Studies have consistently demonstrated the superior performance of qPCR; for instance, one evaluation found qPCR positive in 73.5% of samples compared to only 37.7% by microscopy [45]. This enhanced detection capability is particularly valuable for identifying coinfections and asymptomatic cases, which are frequently missed by traditional methods [45].

Chilomastix mesnili: A Neglected Protozoan